Abstract

Around the world, legislatures are dominated by politicians who are wealthier and more educated than their constituents. This is particularly so in developing democracies, where clientelist politics and wealth inequalities make it difficult for lower-class citizens to run for office. We contribute to scholarly debates about the substantive consequences of descriptive inequality by analysing a new and important case – Indonesia, the world’s third most populous democracy. Indonesian politicians have much higher levels of education and income than citizens, and they are more likely to have professional backgrounds. To explore the implications of these inequalities, we survey and compare politicians’ and voters’ positions on a range of economic policy issues. We find the views of Indonesian politicians are generally more congruent with those of upper-class voters. However, we also find variation across policy areas. There is much cross-class agreement on statist interventions like price controls – in part reflecting politicians’ dependence upon the state; however, the gap between voters and politicians widens substantially on the issue of economic redistribution. Upper-class biases within Indonesian legislatures thus obscure a large lower-class constituency in favour of a more redistributive economic regime, a consituency largely unrepresented by Indonesia’s parties.

Introduction

A core tenet of representative democracy is that citizens vote for politicians who share their values and policy positions. Representative democracy, it is commonly believed, should achieve ‘accurate reflection of the community [and] should secure in the government a “reflex” of the opinion of the entire electorate’.Footnote1 Yet around the world, legislative institutions are dominated by politicians from privileged social classes, and lower-class citizens are largely excluded from the halls of power. This is true of established democracies and is even more so of developing democracies with large numbers of poor, working-class and precarious citizens.

This upper-class bias in the composition of legislatures has long concerned scholars of representative democracy, and motivated robust debate about whether such weak descriptive representation matters for the substantive representation of lower-class interests. On the one hand, early studies of established democracies in Europe and North America argued that legislators’ socio-economic backgrounds have little bearing on their attitudes, ideological positions or behaviour in office, because politicians adjust to their party programme, and, through their party, to the preferences of the constituents they serve.Footnote2 Programmatic parties, in short, blur the divide separating constituents from their representatives. Other research, however, suggests that socio-economic differences between politicians and voters do matter for how lower-class interests are channelled into a political system, especially in developing country settings.Footnote3

In this article, we contribute to these debates with a new and important country case study – Indonesia. Indonesia is the world’s third most populous democracy, with one of the most successful transitions in the third wave of democratisation. Since the fall of the authoritarian New Order regime in 1998, Indonesia has held relatively free, fair and competitive legislative elections at both regional and national levels. Opinion polls indicate that most Indonesians are satisfied with their democratic system.Footnote4

Indonesia also suffers from a range of problems common to developing democracies that make both substantive and descriptive representation difficult. Rather than having a programmatic party system, in which parties align on a left–right spectrum and compete on the basis of alternative policy platforms, Indonesia’s democracy runs on patronage, and vote-buying in legislative elections is widespread. Political campaigns are thus expensive, which favours wealthy candidates. A large body of qualitative literature asserts that elected office at both national and local levels has been captured by entrenched elites whose influence dates back to the authoritarian era, and whose wealth is largely derived from their ability to manipulate bureaucratic power for private gain.Footnote5 Many parties, meanwhile, are catch-all parties with indistinguishable socio-economic platforms. To the extent that ideology matters in Indonesian politics, the party system is structured around religious issues, not class, with Islamic parties favouring a larger role for Islam in public life, and ‘nationalist’ or pluralist parties espousing a more multi-religious vision for the polity.

Against this backdrop, we explore how class inequalities affect representation in a developing democracy context. We present the first systematic investigation into the background of Indonesian legislators, showing they not only have higher incomes and education than their constituents, but they also skew heavily to upper-class professional backgrounds. We further investigate whether legislators reflect the spectrum of socio-economic policy preferences held by different class constituencies. We ask, in a country where political competition is structured around religion rather than class, and where politicians are connected to their constituents through clientelist linkages, whether the preferences of lower-class citizens are systematically under-represented, whether there are variations across policy domains in the degree of congruence between the views of politicians and citizens, and if so, what might explain these variations.

To answer these questions we use surveys to compare voters’ and politicians’ policy positions. We draw upon data from an original survey of provincial legislators (members of the Dewan Perwakilan Rakyat Daerah, or DPRD) and compare these politicians’ responses with those of citizens. We ask a range of questions about people’s views on state intervention in the economy, international flows, social insurance and economic redistribution, and we analyse the degree to which the policy preferences of politicans and citizens overlap.Footnote6

Our findings reveal both commmon patterns and variation across the economic policy issues we investigate. We show that the policy preferences of upper-class citizens are overall better represented than those of low-income ones. Legislators are, as we expected, channelling a set of values and economic attitudes that reflect their socio-economic class. This finding provides new empirical support for the proposition that descriptive inequalities – and class inequality especially – matter for substantive representation.

At the same time, our data reveal substantial differences in voter–politician congruence across economic policy areas. Specifically, we find an especially large gap between politicians and lower-class Indonesians on matters of distribution, welfare and foreign immigration. We find evidence for broad support for welfarist and redistributive policies among poor Indonesians that is all but unrepresented in formal politics. Politicians generally do not support redistributive initatives that tax the rich and channel state funds to the poor and unemployed. On these matters, politicians reflect the preferences of wealthier citizens and professionals. On questions of state intervention to control wages and the price of staple goods, however, the views of politicians are more closely aligned with lower-class citizens, highlighting an intriguing divergence between legislators and social elites. We argue this divergence may be explained by the social origins of a large part of the political class in the authoritarian-era governing bureaucratic elite, and their connection to predatory networks oriented to state patronage. Accordingly, legislators, while rejecting interventions for economic egalitarianism, which is in keeping with their class position, also favour what we call economic statism, which accords with their particular dependence on bureaucratic power.

These results have implications for the comparative literature on representation. The left–right indexes commonly used in the congruence literature to evaluate representation on economic issues mostly assume a link between support for state interventionism and support for policies that promote economic egalitarianism, because both are associated with lefist or socialist ideologies. The Indonesian case suggests such indexes may not be capturing important gaps in representation along class lines, or significant points of cross-class alignment. We contribute to the comparative literature on congruence, therefore, by emphasising that in developing democracies, economic statism and economic egalitarianism can attract different class constituencies, and should thus be analysed separately.

The rest of the article is structured as follows. The next section reviews existing studies on representation, with a focus on research about social class and developing democracies. A third section provides background on the Indonesian case, elaborating on the country’s deep political and socio-economic inequalities, and presenting our data on legislators’ backgrounds. The fourth and fifth sections describe and analyse our survey data, and develop our argument about the nature of the upper-class bias within Indonesian legislatures. The concluding section reiterates the signficance of our findings for the study of representation both in Indonesia and and in a comparative context.

Class, congruence and representation

Both in the wealthy democracies of Western Europe, North America and Australasia and in developing democracies, there are persistent inequalities in the class composition of legislative bodies. A study of the United States, for example, finds that ‘[o]fficeholders in every level of government are, on average, better-off than the people they represent by virtually any measure of class or social attainment’.Footnote7 In Europe, legislatures are stacked with politicians who come from professional classes, with larger incomes and higher educational attainment than the average citizen.Footnote8 Unequal descriptive representation along class lines looks particularly stark in developing democracies with middle and lower income economies. In their study of 18 Latin American countries, for example, Carnes and Lupu find that the working class are ‘vastly under-represented’ in legislatures across the region. Between 70% and 90% of citizens are blue-collar workers in Latin American countries, yet citizens with this occupational background makes up just 5–20% of legislators.Footnote9

Why does this descriptive inequality matter? One reason is that social class, generally measured using individuals’ income, education or professional background, or a combination of these three indicators, has long been associated with distinct sorts of socio-economic and political preferences.Footnote10 Studies show that, unsurprisingly, popular support for social welfare spending comes primarily from the people who live more precarious economic lives, with lower incomes and less job security.Footnote11

Yet much research – especially research conducted in the largely programmatically oriented polities of Western Europe and North America – suggests that upper-class biases in legislative institutions have little effect on how lower-class preferences are represented. In their seminal study of the British parliament, Norris and Lovenduski found that ‘in most respects social class failed to have a strong substantive impact [and] the occupational class of politicians was not strongly associated with their social values, policy priorities or legislative roles’.Footnote12 Earlier studies came to similar conclusions.Footnote13 Instead, so the argument went, politicians adjust their policy preferences and attitudes to align with their co-partisans and constituents, regardless of class, and so differences between voters’ and politicians’ socio-economic profiles were believed to be of limited political signficance. In a review of this literature, Lupu observes that, for decades, ‘the idea that a legislator’s class does not matter has been the de facto conventional wisdom in the scholarly community’.Footnote14

Importantly, this body of research has largely focussed on established democracies, in which party systems are generally structured along a left–right ideological cleavage, and where questions of welfare and redistribution constitute major points of difference between the parties. Accordingly, a critial finding was that programmatic parties effectively compensated for the class differences separating represenatives and voters: legislators from social-democratic and leftist parties held views on economic policy that were largely congruent with, or even to the left of, their working-class constituents, whereas conservative party representatives’ views tended to align with those of middle and upper-class voters.

More recent research has challenged this position. Scholars have undertaken more detailed surveys of the attitudes and policy positions of politicians and voters and traced incongruence between the two populations back to class differences, and to the numerical under-representation of lower-class citizens in electoral institutions.Footnote15 In developing democracies, especially, where parties tend to be poorly institutionalised, and their policy platforms on social and economic issues are difficult to distinguish, descriptive inequalities matter for the representation of lower-class interests. In Brazil, for example, where parties are mostly catch-all and clientelist in nature, Boas and Smith find that party affiliations are not good predictors of voters’ distinct policy preferences; instead, legislators and citizens from the same demographic and social groups share a more similar set of policy positions than do legislators and citizens who are co-partisans.Footnote16 Carnes and Lupu’s comparative study of representation in Latin America reveals that legislators from the working classes hold ‘distinct perspectives’ on economic and social policies compared to legislators with professional backgrounds, and those differences have substantive effects on their behaviour as political representatives.Footnote17 Unlike in the established democracies of Europe and North America, parties in developing democracies are often defined in terms of religious, cultural or nationalist cleavages, rather than class cleavages. Linkages between voters and politicians are also more personalistic and clientelistic in nature in younger democracies. The effect is to widen the gap between the preferences of poorer voters and those of elected representatives.Footnote18

In short, existing research increasingly leads us to expect that class differences can blunt the representative quality of democratic institutions, especially in conditions in which programmatic parties are weak and the party system is not oriented along a left–right spectrum. But there is much that we do not know about patterns of descriptive representation and their effects in young and clientelist democracies, given that ‘only very few scholars have studied mass–elite congruence in developing democracies’,Footnote19 and those who have done so have focussed mostly on Latin American cases. In studying Indonesia, we contribute to the embryonic literature on class and mass–elite congruence in developing democracies.

Constraints upon representation in Indonesia

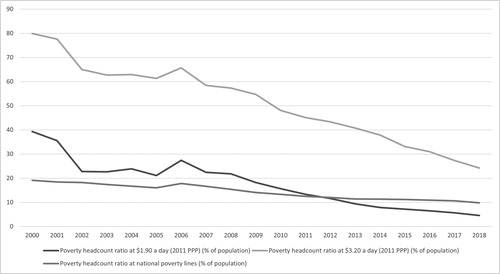

Indonesia is the world’s third most populous democracy, and in 2019 its economy was ranked 15th in the world in terms of nominal gross domestic product (GDP), but only 110th in terms of per capita GDP. The proportion of Indonesians living below the national poverty line has decreased significantly over the past two decades, from 19.1% in 2000, in the wake of the Asian financial crisis, to 9.8% in 2018 (). This trend is partly attributable to almost 20 years of steady economic growth. Consecutive Indonesian governments have also implemented various interventions, such as conditional cash transfer programmes, social safety nets, and local- and national-level health insurance schemes, to try to lift the economic fortunes of Indonesia’s poorest citizens.

Figure 1. Changes in Indonesia’s poverty headcount ratio (In 2011 purchasing power parity, PPP).

Source: World Development Indicators Database, World Bank.

However, the World Bank estimates that – even prior to the COVID-19-induced economic downturn of 2020 – 20% of Indonesian citizens were hovering close to the national poverty line.Footnote20 Indeed, if that line is raised marginally to $3.20 per day, the proportion of poor more than doubles (). Most Indonesians (60–70%) work in the informal sector, and this figure has changed little in recent years.Footnote21 As a result, a large section of the population remains vulnerable to shocks, such as job loss or illness. Income and wealth distribution have also become increasingly unequal in Indonesia over the past two decades: the Gini coefficient rose from 0.3 in 2000 to 0.42 in 2014.Footnote22 Recent research suggests that the richest 1% of Indonesians control 49% of the entire country’s wealth.Footnote23 Such distributional differences have a range of socio-political consequences.Footnote24

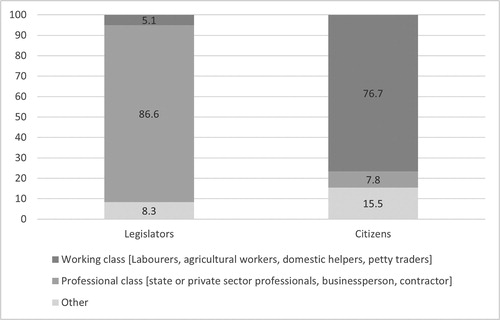

These inequalities mark Indonesia’s democratic institutions. Confirming observations made over the last two decades by qualitative researchers, our survey data (described below) show that politicians are, on average, wealthier and more educated than the general population, and that their professional backgrounds are very different to those of most citizens. For example, around 15% of Indonesians have university degrees,Footnote25 whereas over 80% of provincial legislators have at least an undergraduate degree (electoral rules require them to have at minimum a senior high school education). Population surveys show that most Indonesians still make their living from often informal manual and other low-status jobs, for example as labourers, agricultural workers, petty traders and the like (); just 5% of legislators come from this occupational group.

One of our striking findings, moreover, is that not only are local legislators from wealthy backgrounds, but many of them have politico-bureaucratic connections. Over the last 20 years, as Indonesia’s democracy has evolved, many new entrants into the political system have come from the private sector and professional classes.Footnote26 Our survey provides some confirmation, showing that the largest single occupational category for DPRD members prior to joining the legislature was as businesspeople in trade and services (24.2%) (). Strikingly, however, a significant minority (around 20%) of legislators have backgrounds in sectors that are notoriously dependent on state connections (notably, construction contracting – 14.6% and plantations and mining – 5%). More strikingly still, while only a small proportion (8.9%) had themselves been civil servants or worked for a state-owned enterprise before joining the legislature, a large minority had family links to the authoritarian-era ruling bureaucratic elite: almost one-third had fathers who worked as civil servants or local government officials, or were part of the military or police. In response to a separate question, 33% of legislators stated they had close relatives who had held important positions in the New Order power structure (as district heads or military or police chiefs, for example).

Table 1. Occupational backgrounds of legislators and their fathers.

This is an important finding. The qualitative literature on Indonesian politics stresses the continuing salience of bureaucratic power in local political and patronage networks, as a legacy of the leading role played by bureaucrats both in government and in the formation of private capital during the New Order era.Footnote27 At that time, office holders leveraged their political authority to foster a class of state-dependent businesspeople, often their own relatives or business cronies.Footnote28 In the post-authoritarian setting, bureaucratic connections remain important for the pursuit both of private wealth (via access to projects, licences, permits, corruption, etc) and of political office (because government continues to provide patronage resources that politicians can use in their campaigns). The close nexus between bureaucratic power and private wealth thus remains a defining feature of Indonesia’s political economy, and of politics. Some studies have detailed that a large proportion of local executive government heads continue to have bureacuratic backgrounds.Footnote29 Our study is the first to provide more than anecdotal data to show that legislators, while not themselves former bureaucrats, are substantially drawn from that group who were nurtured – including through family ties – by the bureacratic state. Overall, our data reveal stark descriptive inequalities within the country’s representative institutions, and also point to a group of legislators who are not simply wealthier than most Indonesians: their professional and familial backgrounds have a distinctly statist cast.

Further, Indonesia’s historical political legacies make formal representation of lower-class interests especially difficult. Unlike many Western countries, and parts of Latin America, Indonesia has little recent history of institutionalised class-based political mobilisation.Footnote30 In the 1950s and 1960s, the Indonesian Communist Party (Partai Komunis Indonesia – PKI) was a major force, attracting a mix of intellectuals, workers and peasants. But following the military-backed massacre of supporters of the party in 1965–66, General Suharto’s New Order government disbanded the PKI, outlawed communism, and for the next 30 years repressed left-wing politics.

Indonesia’s transition to democracy at the end of the 1990s brought a dramatic re-opening of political space. In the early post-authoritarian period, there was potential for a revival of leftist forms of political mobilisation. As one of us previously observed, the democratic transition prompted a ‘tremendous profusion of people’s organisations, trade unions and farmer groups and a multiplicity of small – sometimes tiny – organisations that campaign for the rights of this or that marginalised group in society’.Footnote31 However, leftist advocacy continued to lack an organisational centre. The only consistently left-wing party to compete in Indonesia’s post-New Order elections, the People’s Democratic Party (PRD), failed to win a seat in 1999 and never ran again. In the gap left by a fragmented and disorganised left, according to Hadiz, many groups on the political and economic margins expressed their grievances through an ‘Islamic lexicon’, rather than leveraging class-based frameworks.Footnote32 Those grievances are often moral in nature, and concern issues such as religious and sexual deviance, rather than problems of labour rights, social assistance and economic exclusion.

The platforms of Indonesia’s political parties are also essentially indistinguishable on socio-economic issues. Parties are, instead, differentiated primarily along religious lines: some identify as Islamic and espouse a more Islamist social and political agenda, while others have a pluralist orientation and, as a result, attract support from less conservative Indonesian Muslims and from the country’s religious minorites. This cleavage, however, does not translate into distinct economic or welfare platforms. Rather, Indonesian politicians view their parties as holding similar positions on the economic policy issues that elsewere delineate left- and right-leaning parties.Footnote33 Only when it comes to the question of the role Islam should play in state affairs do politicians express significant differences.Footnote34

Representation of lower-class interests is also impeded by the ubiquity of clientelism. Politicians from across the party spectrum seek linkages with voters primarily through patron–client relationships, and those relationships are usually embedded within wider social and religious networks. Especially when it comes to local elections, these networks matter more for getting votes than do promises of policy change or programmatic benefits; vote-buying is also commonplace.Footnote35 Our extensive qualitative research on regional electionsFootnote36 shows that local politicians typically take great pains to demonstrate they are able to be ‘close’ to the ordinary people (frequently summed up in the verb merakyat) and that they ‘care’ (peduli) about them. However, typically their interactions with ordinary voters take place in a gift-giving rather than programmatic mode, with candidates demonstrating their concern by delivering direct benefits (eg help with repairs to a village road, a gift of sports equipment to a neighbourhood youth group, or direct cash gifts to voters).Footnote37 So long as politicians demonstrate their closeness through such gifts, there is little pressure on them to deliver policy change.

At the same time, given that Indonesian elections encourage personal rather than party-based voting, political campaigns are largely funded by individual candidates and are prohibitively expensive for most persons, which helps to explain why the occupational class of legislators is tilted towards those with private wealth. As noted above, scholars regularly characterise Indonesia’s politics and government as captured by politico-business elites and wealthy oligarchs whose primary goal is wealth accumualtion rather than representation.Footnote38

In the context of a political landscape that lacks an organised left, where religion structures the party system, and where clientelist networks connect politicians and voters, whose socio-economic preferences are reflected in the legislative arena? Our assumption is that lower-class citizens’ policy interests will be under-represented, given the constraints described above. However, the scholarship on this subject has so far lacked systematic comparative analysis of elite and mass preferences, which can measure the degree of congruence between these two groups along class lines.

Research design

We set out to test the extent to which Indonesian politicians’ attitudes and preferences on socio-economic policy issues align with those of the wider public, and in particular whether they align with those of lower-class citizens. To do this, we leverage an original survey of Indonesian legislators carried out between December 2017 and March 2018. The survey was conducted on a sample of 508 Indonesian politicians sitting in provincial legislatures around the country. We chose to interview provincial politicians in part because we determined that national-level legislators would be less accessible and less willing to participate in an extended opinion poll.

However, provincial politicians also constitute an influential group of political elites. DPRD are often stepping stones for politicians to move into executive government in the regions and to the national legislature, and to influence local- or national-level policy agendas. For example, of the 575 politicians elected in 2019 to the national legislature, 66% had prior experience as politicians in either the national parliament or local legislatures, as local government leaders or, less commonly, as ministers.Footnote39 Provincial legislators, unsurprisingly therefore, look much like their national counterparts: 80% of the politicians in Indonesia’s national parliament have a university degree,Footnote40 which is the same proportion as provincial parliamentarians; and beyond the 66% of DPR members with political backgrounds, the rest come mostly from the private sector (29%), as is the case in the provinces.Footnote41

Provincial politicians do not design national-level economic interventions. Their primary role is to monitor the regional government, approve provincial government budgets, and design regulations in partnership with the provincial government – which does have authority to introduce welfare schemes and determine minimum wages. But, we maintain, these politicians are part of a pool of elites from which local executives and national legislators are often drawn. We are confident, therefore, that our survey provides us with compelling insight into the preferences of Indonesia’s political class more broadly.

The survey was conducted via face-to-face interviews with a randomly selected sample of politicians. The total population of 2073 politicians was first stratified into three main regions (Sumatra, Java and other islands). Provinces constituted the primary sampling unit, and were selected according to their population proportion. The survey was carried out by Lembaga Survei Indonesia (LSI), a prominent Indonesian polling institute of which one of the authors is the director. For the wider population, we draw upon a representative survey conducted in 2017 by the same polling institute. Both surveys collected information on income, education and professional background, which we use as indicators of a person’s social class, and as potential indicators of socio-economic and political preferences.Footnote42 As explained below, we disaggregate citizens by each of these indicators, and compare the attitudes of those in the lowest and highest socio-economic strata to those of legislators, whom we treat as a largely homogeneous upper-class population.

Measuring congruence

Several studies have used survey data to compare the policy positions of voters and politicians in order to determine the level of ‘congruence’ between elected elites and the wider population. Scholars who adopt this approach often measure ‘ideological distance’ by comparing the average placement of citizens and politicians on ideological left–right scales.Footnote43 As discussed earlier, political competition and public debate are not structured around a left–right divide in many parts of the world. Even in some Western contexts, scholars have revealed serious limitations to left–right scales and instead favour comparing mass and elite positions on specific policy areas.Footnote44

There are also compelling theoretical arguments against measuring congruence only by comparing only average ideological positions or policy preferences amongst the public and their representatives. The mean response of a population may not actually reflect the position of many voters,Footnote45 and average scores are unable to ‘distinguish a centrist electorate from a highly polarised one’.Footnote46 Congruence should, therefore, be a measure of ‘how accurately the collective body’ of political representatives reflects the spectrum of popular preferences in a given polity.Footnote47

To calculate levels of congruence between citizens and legislators, both overall and according to those class indicators, we adopt a method proposed by Andeweg, which builds upon the many-to-many congruence measure first developed by Golder and Stramski.Footnote48 Specifically, we measure the overlap between the distribution of responses amongst Indonesia’s elected elite and the distribution of responses amongst the public. For each survey question, we compare the percentage of elites that chose a particular answer with the percentage of the public that chose that same answer. We then add up the lower of the two percentages for each possible answer, because the lower number captures the overlap between the two populations. This number will range from zero to 100 and gives us the percentage of the total overlap between politicians and citizens for each question.

Measuring attitudes on seven economic issues

Our survey questions are designed to reveal elite and mass positions on several areas of economic governance that may express differing class interests. These areas include redistributive welfare programmes, state intervention in the economy, and international flows of goods, capital and people. While other studies have used similar questions to create an index designed to measure respondents’ economic ideology,Footnote49 we analyse each question separately to allow for the possibility that policy preferences in some areas cut across class lines.

A first set of two questions asks about preferences on economic redistribution (). We ask respondents if they would support more assistance to the poor if it meant raising taxes, and whether the government should support subsidies for the unemployed. Our expectation is that people who are financially more precarious will be more likely to support such distributive interventions. We then include two further questions to interrogate respondents’ positions on distortive market interventions, specifically subsidies for gasoline and staple goods, and state intervention to determine the minimum wage. These are examples of policies with broad-based benefits, where our expectations are not so strong: in established democracies with programmatic party systems, views on such matters typically align along the left–right spectrum, with right-wing politicians and voters who oppose redistribution frequently rejecting state intervention in both policy areas; in Indonesia, a similar ideological spectrum is absent, and many politicians themselves have connections to state-centred networks of wealth accumulation and may therefore embrace state intervention in the economy.

Finally, we also ask a series of questions designed to gauge elite and mass attitudes to foreign flows. In the case of trade and foreign investment, deriving economic policy preferences from class differences is problematic, as the economic benefits associated with globalisation may be more closely associated with economic sector than with position in the labour market. In Western settings, support for economic nationalism and state interventionism are traditionally associated with leftist ideological leanings and working-class constituencies; open market policies are usually advocated by those with a liberal orientation and those associated with the business class. We have no strong expectations about how class differences might predict support for nationalist and interventionist policies in Indonesia. Instead, anecdotal evidence suggests widespread public backing for economic nationalism.Footnote50 As for immigration, since most incoming immigration in Indonesia is for high-skill positions, we expect high-income professionals to be less supportive of immigration than those in working-class jobs. Respondents received the statements displayed in and were asked to answer on a Likert scale: strongly disagree, disagree, neutral, agree, strongly agree.

Table 2. Survey questions.

(In)congruence between Indonesian citizens and politicians

We begin by presenting and comparing the mean responses for both citizens and representatives to our battery of questions on policy preferences, without dissagregating by class (). The results indicate remarkable congruence on state intervention, and on foreign trade and investment. Indeed, for these questions, the means are almost identical for both populations. We find variation, however, on redistribution, and on whether the government should be more open to immigrants, with legislators less in favour of these policies than the population at large.

Table 3. Comparison of means.

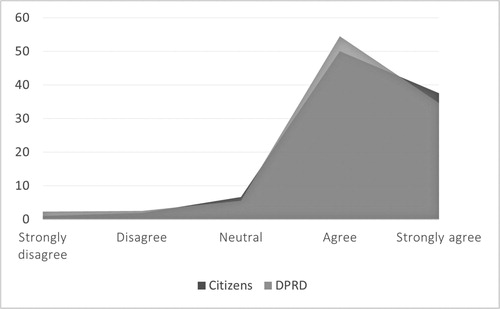

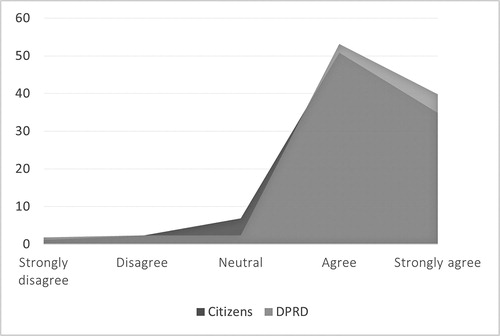

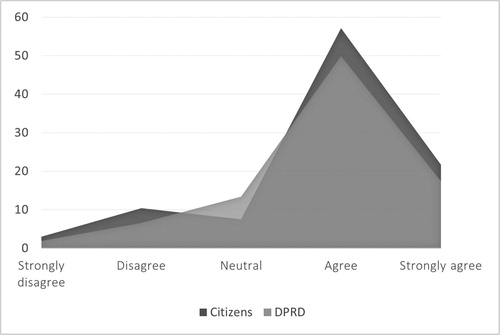

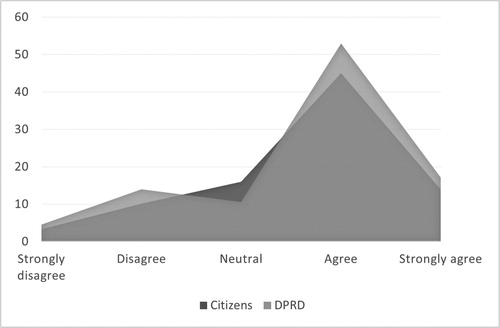

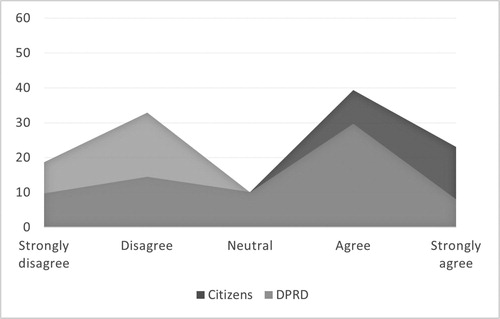

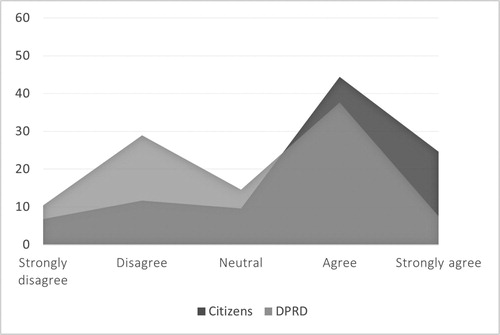

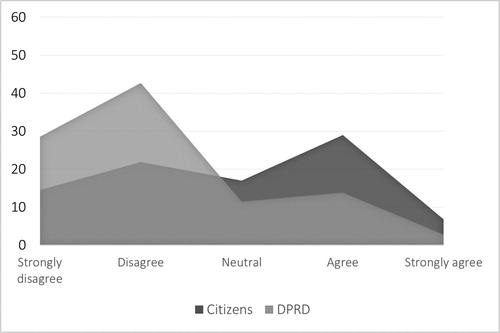

As explained above, focussing on averages alone can mask important variation in the distribution of responses for citizens and representatives. provide a visual characterisation of the entire distribution of responses for each question, and the overlap between citizens and representatives. We start with those policy areas that display the most congruence.

Figure 2. Occupational class of citizens and legislators.

Source: Legislator results are taken from our survey of Indonesian provincial legislators conducted by the Indonesian Survey Institute (LSI) between December 2017 and March 2018; citizen results are from a nationally representative survey conducted by LSI in May 2017.

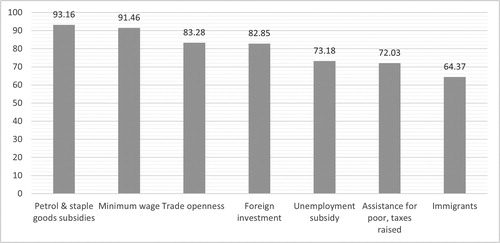

The results indicate remarkable congruence, of over 90%, when it comes to market-distorting interventions. For both populations, there is broad support for the government to intervene and control the price of gasoline and staple goods (), pointing to a strong societal consensus in favour of state subsidies. The results are similar regarding a minimum wage (), with an overlapping distribution of 91.5%. We also find strong congruence, of over 80%, on questions of foreign investment and trade, again suggesting consenus amongst citizens and politicians ( and ). Interestingly, however, that consensus is in favour of these foreign flows, which indicates more widespread acceptance of economically liberal policies than we anticipated.

A gap emerges, however, when it comes to how citizens and politicians view distributive and welfare policies, and how accepting they are of foreign immigrants (). Citizens are overall more likely to support subsidies for the unemployed and more welfare for the poor, and they are generally more open to foreign immigration than politicians. The first two of these findings point towards a large, and mostly unrepresented, constituency for redistribution in Indonesian politics. For example, when it comes to the question of increasing taxes to spend more public funds on the poor, only 38% of politicians agree, compared to 62% of the public. We calculate the overall overlap of citizens’ responses with those of politicians to be 72% on this question. Unemployment benefits are much more popular with citizens too, with 69% in favour; for politicians, the percentage is just 45. Similarly, 37% of Indonesians oppose allowing more immigrants and foreign workers, compared to over 72% of politicians. The overall congruence levels for each question is displayed in .

Overall, therefore, we find much consensus on policies for economic statism, which include interventions to distort and control prices. These are long-established policies in Indonesia that provide benefits to a large slice of the population. Few Indonesian governments have been able to remove or reform them, largely because of their immense popularity, but also because – as our findings suggest – they reflect a widely shared ideological predisposition among sections of the political elite who have long favoured statist models of economic development and who, as our survey findings confirm, frequently owe their elite status to state connections and interventions.Footnote51 As such, these policies appear to be uncontroversial in the minds of most Indonesians – both citizens and their representatives. However, consensus for interventionism does not extend to economic redistribution, which involves policies that would most assist the poor and vulnerable. Politicians are out of step with the wider population on such matters – they generally oppose unemployment benefits, and oppose increasing taxes in order to expand welfare for the poor. And while both populations are open to foreign flows of goods and capital, the public are far less opposed to flows of people than are politicians.

Explaining incongruence: class matters

Next, we examine whether levels of congruence vary along class lines. More specifically, we look at whether Indonesians’ class characteristics shape their position on particular policies and whether legislators’ attitudes and policy priorities align more with those of wealthier, more educated voters, and with those from professional backgrounds. To test this hypothesis we break citizens into six, partially overlapping groups: low income (earns less than 1 million rupiah per month, or approximately US$70), high income (earns over 4 million rupiah per month, or approximately US$280), low education (those who have less than or only a primary school education), high education (those who hold a university degree), professional class (state and private sector professionals, business owners, contractors) and working/informal class (labourers, agricultural workers, petty traders, domestic helpers, etc).

We do not dissagregate legislators into different demographic groups, given that along all of these class indicators, they form a largely homogeneous population, with over 80% holding university degrees, all earning a wage of over 4 million rupiah per month (the standard for provincial legislators), and a strong majority (over 86%) having professional backrounds. Instead, we calculate the attitudinal congruence between citizens in each class category and the entire population of provincial legislators ().

Table 4. Overlap between legislators and citizens (by citizens’ social class).

The results confirm that across most policy areas, congruence with the preferences of politicians is almost always highest for citizens with high levels of income, followed by either high education or professional backgrounds; congruence is generally lowest for citizens with the lowest levels of income and education. This is particularly so when it comes to policies that concern distribution and immigration. For example, while politicians are overall less likely than citizens to support increased welfare support for the poor, congruence increases with citizens’ education from 67% for those with no or only primary education to 82% for those with university degrees. Congruence increases because the more educated citizens tend, like politicians, to oppose redistributive interventions. A similar pattern emerges by income group. Congruence drops to 66% with low-income voters, and increases to 75% for those with incomes above 4 million rupiah (around US$280) per month.

The results are similar regarding unemployment subsidies. In general, legislators are far less supportive than the public of government subsidies for the unemployed (to recall, 45% of politicians supported government-provided unemployment subsidies, compared to 69% of citizens). For the Indonesians with the least formal education, their preferences on this issue have a 65% rate of overlap with representatives; the overlap increases to 82% for the most educated citizens. Between income groups, the jump is from a 62% overlap to 80%. In short, legislators’ opposition to increasing taxes and redistributing to the poor best matches the preferences of citizens from higher socio-economic backgrounds.

We find generally similar results on foreign investment (74% overlap between legislators and the poorerst citizens; 93% overlap with the wealthiest citizens). Immigration produces the smallest overlap between voters and legislators, with levels of congruence at just 58% for both low-income and low-education citizens. This means that higher-income Indonesians, and especially those with tertiary degrees, are more likely to oppose foreign immigration, just like legislators. In other countries, it is often people with less economic security who express anxiety about competing with foreign workers; in Indonesia, foreign labour migration is oriented towards senior professional positions such as managers and directors.Footnote52 A preference for restrictive immigration policies is therefore associated with privileged classes in Indonesia, and, in turn, is reflected in the attitudes of provincial lawmakers.

By contrast, the only measure in which legislators’ views were more congruent with lower-class citizens (at least on the educational and occupational measures) was on the question of regulating prices. Higher-class voters were more likely to oppose state intervention on price-fixing than were either legislators or lower-class voters. It may simply be the case that legislators are particularly attuned to popular attitudes on this issue, whereas more educated citizens and those from professional backgrounds both feel little need for these subsidies, and are more aware of the arguments advanced through the media by liberal economists about their inefficiency.

But this divergance may also flow from differences in relations with the state: as we noted above, a large proportion of politicians in Indonesia have personal bureaucratic backgrounds (often as family members), or are otherwise embedded in professional and patronage networks that derive their economic sustenance from the state. Many of them are steeped in statist traditions of economic management. It thus makes sense for such politicians to favour state intervention in the economy, even if they are not in favour of using the state for broadly distributional programmes, instead preferring to win the support of poor voters through clientelistic linkages. While a portion of wealthy citizens are also state-dependent – indeed, legislators’ statist preferences on price controls and wages aligned most closely with those of citizens in the highest income category – recent decades have witnessed a massive growth of the private economy, including in retail and services sectors where the state often acts more as a predatory impediment to, rather than a facilitator of, business activity.Footnote53 Divergence on this measure may thus reflect an important gap between the economic preferences of Indonesia’s ruling elite and those of the middle and upper classes, at least when measured by education and profession.

Conclusion

This paper contributes to the growing literature on class and congruence in developing democracies by offering the first such study of Indonesia. We interrogated a prevailing characterisation of Indonesian democracy that views poorer citizens as under-represented in a political system dominated by oligarchs and wealthy politicians. Overall, we found significant congruence between the views of legislators and citizens on certain statist features of Indonesia’s political economy. This result emphasises that class-based divisions over statist economic models that have long animated economic and political debate in the West are far from universal, and in developing countries such as Indonesia, interventionism elicits broad consensus amongst citizens and their representatives.

Nevertheless, our study revealed significant variation across issue areas. We identified a significant constituency for redistributive and welfare policies among poorer and less educated voters that is largely unrepresented by elected legislators. Like wealthier, better educated and professional voters, legislators are more likely to oppose state interventions that would redistribute wealth in favour of the poor. At the same time, our findings also revealed important divergence between political elites and upper-class citizens on questions of price controls – legislators were more likely to embrace this type of state interventionism, which we suggested may reflect the poltical elite’s dependence upon the state as a source of political patronage and private wealth.

These findings point to a political system that is stamped indelibly by the social inequalities that mark Indonesian society. As in many developing democracies, in Indonesia parties do not offer voters alternative economic policy agendas, and so politicians’ class backgrounds matter greatly for selecting the socio-economic attitudes and ideas that are channelled into legislative arenas. We thus found a clear upper-class bias within Indonesia’s legislative bodies that obscures a strong lower-class preference for redistribution.

These results also have implications for the comparative literature on congruence and representation. The Indonesian case confirms that the notion of a left–right spectrum, which captures distinct class preferences on socio-economic policies, has less meaning outside of Europe, North America and Latin America. The Left is usually associated with support for an interventionist state that can control and constrain the market, including by subsidising certain basic goods and services, and by restributing wealth to poor and precarious citizens. In Indonesia, however, we found important differences in the constituencies that support economic statism versus economic egalitarianism, with cross-class support for the former, and distinct class preferences regarding the latter. We argue, therefore, that widely used ideology indexes should be dissagregated when studying developing democracies, in order to reveal potential gaps in representation along class lines, as well as critical arenas of cross-class alignment.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments on earlier drafts, the Asia Research Institute at the National University of Singapore for hosting a workshop at which the paper was first discussed, and the Australian Research Council for funding the research on which it is based.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Eve Warburton

Eve Warburton is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore. She is interested broadly in identity, representation and the political economy of policymaking in young democracies, with a geographic focus on Southeast Asia (and Indonesia in particular).

Burhanuddin Muhtadi

Burhanuddin Muhtadi is a Senior Lecturer at the Faculty of Social and Political Sciences, Syarif Hidayatullah State Islamic University, Jakarta, Indonesia. He is also an executive director of the Indonesian Political Indicator (Indikator Politik Indonesia) and the Director of Public Affairs at the Indonesian Survey Institute (Lembaga Survei Indonesia, LSI). His research interests include political Islam, democracy, voting behaviour, clientelism and social movements.

Edward Aspinall

Edward Aspinall is a Professor in the Department of Political and Social Change, Coral Bell School of Asia Pacific Affairs, Australian National University. He researches politics in Southeast Asia, especially Indonesia, with interests in democratisation, ethnicity and clientelism, among other topics.

Diego Fossati

Diego Fossati is an Assistant Professor of Asian and international studies at City University of Hong Kong. He studies political behaviour, accountability and representation, especially in the context of East and Southeast Asia.

Notes

1 Pitkin, Concept of Representation, 61.

2 See Matthews, “Legislative Recruitment and Legislative Careers”; Norris and Lovenduski Political Recruitment.

3 Carnes, “Does the Numerical Underrepresentation of the Working Class”; Carnes and Lupu, “Rethinking the Comparative Perspective on Class and Representation”; Schakel and Hakhverdian, “Ideological Congruence and Socio-Economic Inequality.”

4 Mujani, Liddle, and Ambardi, Voting Behavior in Indonesia.

5 Hadiz and Robison, “Political Economy of Oligarchy”; Robison and Hadiz, Reorganising Power in Indonesia, Winters, “Oligarchy and democracy.”

6 We have leveraged data from this same survey to explore other areas of congruence between masses and elites in Indonesia, specifically regarding democratic support and religious ideology: see Aspinall et al., “Elites, Masses and Democratic Decline in Indonesia”; Fossati et al., “Ideological Representation in Clientelistic Democracies.”

7 Carnes, “Does the Numerical Underrepresentation of the Working Class,” 6.

8 Rosset, Giger, and Bernauer, “More Money, Fewer Problems?”; Walczak and van der Brug, “Representation in the European Parliament.”

9 Carnes and Lupu, “Rethinking the Comparative Perspective on Class and Representation,” 6–7.

10 Manza and Brooks, “Class and Politics”; Haggard, Kaufman, and Long, “Income, Occupation, and Preferences for Redistribution”; Iversen and Soskice, “Asset Theory of Social Policy.”

11 Brooks and Manza, Why Welfare States Persist; Rehm, “Risk Inequality and the Polarized American Electorate.”

12 Norris and Lovenduski, Political Recruitment, 224.

13 eg Matthews, “Legislative Recruitment and Legislative Careers.”

14 Lupu, “Class and Representation in Latin America,” 229.

15 Carnes, “Does the Numerical Underrepresentation of the Working Class”; Schakel and Hakhverdian, “Ideological Congruence and Socio-Economic Inequality”; Lupu and Warner, “Mass–Elite Congruence and Representation in Argentina”; Gilens, “Affluence and Influence”; Bartles, “Economic Inequality and Political Representation.”

16 Boas and Smith, “Looks Like Me, Thinks Like Me.”

17 Carnes and Lupu, “Rethinking the Comparative Perspective on Class and Representation.”

18 Kitschelt, “Linkages between Citizens and Politicians in Democratic Polities”; Mainwairing and Torcal, “Party System Institutionalization.”

19 Lupu and Warner, “Mass–Elite Congruence and Representation in Argentina,” 282.

20 World Bank, A Perceived Divide.

21 Ibid.

22 Ibid.

23 Gibson “Towards a More Equal Indonesia.”

24 Muhtadi and Warburton, “Inequality and Democratic Support in Indonesia.”

25 OECD, “Indonesia Country Note: Education at a Glance.”

26 Poczter and Pepinsky, “Authoritarian legacies in Post-New Order Indonesia”; Choi, “Local Political Elites in Indonesia.”

27 Hadiz, Localising Power in Post-Authoritarian Indonesia; Aspinall and Berenschot, Democracy for Sale.

28 The classic study is Robison, Indonesia: The Rise of Capital.

29 Buehler, “Married with Children.”

30 Hadiz, “Retrieving the Past for the Future?”

31 Aspinall, “Still and Age of Activism.”

32 Hadiz, “Indonesia’s Missing Left and the Islamisation of Dissent.”

33 Aspinall et al., “Mapping the Indonesian Political Spectrum.”

34 To be sure, Islamic and pluralist parties routinely form coalitions and cut deals in parliament across this ideological divide, and they share a basic patronage-seeking orientation. Slater and Simons, “Coping by Colluding.” Moreover, this division has been blurred by a long-observed conservative drift within Indonesia’s Islamic community. Even so, the pluralist-Islamist cleavage remains the primary – indeed, the only significant – axis of competition structuring Indonesia’s party system. As demonstrated by one recent study, this cleavage structure is meaningful for both voters and politicians, with voters generally choosing parties that best align with their views on the proper place of Islam in social and political life. See Fossati et al., “Ideological Representation in Clientelistic Democracies”; see also Aspinall and Mietzner, “Indonesia’s Democratic Paradox.”

35 Aspinall and Sukmajati, Electoral Dynamics in Indonesia; Aspinall and Berenschot, Democracy for Sale; Muhtadi, Vote Buying in Indonesia.

36 Ibid.

37 Numerous chapters in Aspinall and Sukmajati, Electoral Dynamics in Indonesia, demonstrate this mode of politics.

38 Winters, “Oligarchy and Democracy in Indonesia”; Hadiz and Robison, “Political Economy of Oligarchy.”

39 Formappi, “Anatomy of the Chosen Candidates.”

40 Maharani, “Background of DPR Members.”

41 Formappi, “Anatomy of the Chosen Candidates.”.

42 Manza and Brooks, “Class and Politics”; Haggard, Kaufman, and Long, “Income, Occupation, and Preferences for Redistribution.”

43 Luna and Zechmeister, “Political Representation in Latin America”; Dalton, “Political Parties and Political Representation”; Dalton, “Party Representation across Multiple Issue Dimensions.”

44 Schakel and Hakhverdian, “Ideological Congruence and Socio-Economic Inequality,” 443.

45 Lupu and Warner, “Mass–Elite Congruence and Representation in Argentina,” 283.

46 Schakel and Hakhverdian, “Ideological Congruence and Socio-Economic Inequality,” 446.

47 Golder and Stramski, “Ideological Congruence and Electoral Institutions,” 95.

48 Ibid.; Andeweg, “Approaching Perfect Policy Congruence.”

49 Lupu and Warner, “Mass–Elite Congruence and Representation in Argentina.”

50 Warburton, “Indonesia: Why Economic Nationalism.”

51 The history of contestation during the New Order period between liberal technocrats and economic nationalists is detailed in Robison, Indonesia: The Rise of Capital.

52 Indonesia Investments, “Foreign Workers in Indonesia.”

53 This tension has long been evident in Indonesia’s political economy; see MacIntyre, Business and Politics in Indonesia and Aspinall, “Triumph of Capital.”

Bibliography

- Andeweg, Rudy B. “Approaching Perfect Policy Congruence; Measurement, Development, and Relevance for Political Representation.” In How Democracy Works: Political Representation and Policy Congruence in Modern Societies, edited by Martin Rosema, Bars Denters and Kees Aarts, 39–52. Amsterdam: Pallas, 2011.

- Aspinall, Edward. “The Triumph of Capital? Class Politics and Indonesian Democratisation.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 43, no. 2 (2013): 226–242. doi:10.1080/00472336.2012.757432.

- Aspinall, Edward. 2012. “Still an Age of Activism.” Inside Indonesia. Edition 107, Jan–March. https://www.insideindonesia.org/still-an-age-of-activism

- Aspinall, Edward, and Ward Berenschot. Democracy for Sale: Elections, Clientelism, and the State in Indonesia. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2019.

- Aspinall, Edward, Diego Fossati, Burhanuddin Muhtadi, and Eve Warburton. 2020. “Elites, Masses and Democratic Decline in Indonesia.” Democratization 27, no. 4 (2020): 505–526. doi:10.1080/13510347.2019.1680971.

- Aspinall, Edward, Diego Fossati, Burhanuddin Muhtadi, and Eve Warburton. 2018. “Mapping the Indonesian Political Spectrum.” New Mandala. https://www.newmandala.org/mapping-indonesian-political-spectrum/

- Aspinall, Edward, and Marcus Mietzner. “Indonesia’s Democratic Paradox: Competitive Elections Amidst Rising Illiberalism.” Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 55, no. 3 (2019): 295–317. doi:10.1080/00074918.2019.1690412.

- Aspinall, Edward, and Mada Sukmajati. Electoral Dynamics in Indonesia: Money Politics, Patronage and Clientelism at the Grassroots. Singapore: NUS Press, 2016.

- Bartels, Larry. “Economic Inequality and Political Representation.” In The Unsustainable American State, edited by L. Jacobs and D. King, 167–198. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, 2009.

- Boas, T. C., and A. E. Smith. “Looks like Me, Thinks Like Me: Descriptive Representation and Opinion Congruence in Brazil.” Latin American Research Review 54, no. 2 (2019): 310–328. doi:10.25222/larr.235.

- Brooks, Clem, and Jeff Manza. Why Welfare States Persist: The Importance of Public Opinion in Democracies. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2007.

- Buehler, Michael. 2013. “Married with Children.” Inside Indonesia. https://www.insideindonesia.org/married-with-children

- Carnes, Nicholas. “Does the Numerical Underrepresentation of the Working Class in Congress Matter?” Legislative Studies Quarterly 37, no. 1 (2012): 5–34. doi:10.1111/j.1939-9162.2011.00033.x.

- Carnes, Nicholas, and Noam Lupu. “Rethinking the Comparative Perspective on Class and Representation: Evidence from Latin America.” American Journal of Political Science 59, no. 1 (2015): 1–18. doi:10.1111/ajps.12112.

- Choi, Nankyung. “Local Political Elites in Indonesia: ‘Risers’ and ‘Holdovers.’” Journal of Social Issues in Southeast Asia 29, no. 2 (2014): 364–407. doi:10.1355/sj29-2e.

- Dalton, Russell J. “Party Representation across Multiple Issue Dimensions.” Party Politics 23, no. 6 (2017): 609–622. doi:10.1177/1354068815614515.

- Dalton, Russell J. “Political Parties and Political Representation: Party Supporters and Party Elites in Nine Nations.” Comparative Political Studies 18, no. 3 (1985): 267–299. doi:10.1177/0010414085018003001.

- FORMAPPI (Forum Masyarakat Peduli Parlemen). “Anatomi Caleg DPR RI Terpilih 2019” [“Anatomy of the Chosen Candidates in the 2019 National Legislature”]. September 5, 2019. http://parlemenindonesia.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/ANATOMI-CALEG-DPR-RI-TERPILIH-PEMILU-2019.pdf

- Fossati, Diego, Edward Aspinall, Burhanuddin Muhtadi, and Eve Warburton. “Ideological Representation in Clientelistic Democracies: The Indonesian Case.” Electoral Studies 63 (2020): 102111. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2019.102111.

- Gibson, L. “Towards a More Equal Indonesia.” Oxfam, February 2017. https://www.oxfam.org/en/research/towards-more-equal-indonesia

- Gilens, Martin. Affluence and Influence: Economic Inequality and Political Power in America. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2012.

- Golder, Matt, and Jacek Stramski. “Ideological Congruence and Electoral Institutions.” American Journal of Political Science 54, no. 1 (2010): 90–106. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5907.2009.00420.x.

- Hadiz, Vedi R. “Indonesia’s Missing Left and the Islamisation of Dissent.” Third World Quarterly (2020). doi:10.1080/01436597.2020.1768064.

- Hadiz, Vedi R. Localising Power in Post-Authoritarian Indonesia: A Southeast Asia Perspective. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2010.

- Hadiz, Vedi R. “Retrieving the Past for the Future? Indonesia and the New Order Legacy.” Asian Journal of Social Science 28, no. 2 (2000): 10–33. doi:10.1163/030382400X00037.

- Hadiz, Vedi R., and R. Robison. “The Political Economy of Oligarchy and the Reorganization of Power in Indonesia.” Indonesia 96, no. 1 (2013): 35–57. doi:10.1353/ind.2013.0023.

- Haggard, Stephan, Robert R. Kaufman, and James D. Long. “Income, Occupation, and Preferences for Redistribution in the Developing World.” Studies in Comparative International Development 48, no. 2 (2013): 113–140. doi:10.1007/s12116-013-9129-8.

- Indonesia Investments. 2018. “Foreign Workers in Indonesia: A Threat or Tactic to Gain Votes?” May 12. https://www.indonesia-investments.com/news/news-columns/foreign-workers-in-indonesia-a-threat-or-tactic-to-gain-votes/item8790

- Iversen, Torben, and David Soskice. “An Asset Theory of Social Policy Preferences.” American Political Science Review 95, no. 4 (2001): 875–893. doi:10.1017/S0003055400400079.

- Kitschelt, Herbert. “Linkages between Citizens and Politicians in Democratic Polities.” Comparative Political Studies 33, no. 6–7 (2000): 845–879. doi:10.1177/001041400003300607.

- Luna, Juan P., and Elizabeth Zechmeister. “Political Representation in Latin America: A Study of Elite-Mass Congruence in Nine Countries.” Comparative Political Studies 38, no. 4 (2005): 388–416. doi:10.1177/0010414004273205.

- Lupu, Noam. “Class and Representation in Latin America.” Swiss Political Science Review 21, no. 2 (2015): 229–236. doi:10.1111/spsr.12162.

- Lupu, Noam, and Zach Warner. “Mass–Elite Congruence and Representation in Argentina.” In: Malaise in Representation in Latin American Countries, edited by A. Joignant, M. Morales, and C. Fuentes, 281–302. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017.

- MacIntyre, Andrew. Business and Politics in Indonesia. Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 1991.

- Maharani, Tsarina. “Background of DPR Members: 9.7% are Highschool Graduates – 9.2% Have Doctoral Degrees.” Detik, October 2, 2019. https://news.detik.com/berita/d-4730292/latar-belakang-pendidikan-anggota-dpr-97-lulus-sma-92-lulus-s3

- Mainwaring, Scott, and Mariano Torcal. “Party System Institutionalization and Party System Theory after the Third Wave of Democratization.” In Handbook of Party Politics, edited by R. Katz, and W. Crotty, 204–227. London: Sage Publications, 2016.

- Manza, Jeffrey, and Brooks Clem. “Class and Politics.” In Social Class: How Does It Work?, edited by A. Lareau, and D. Conley, 201–231. New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2008.

- Matthews, Donald R. “Legislative Recruitment and Legislative Careers.” In Handbook of Legislative Research, edited by G. Loewenberg, S. C. Patterson, and M. E. Jewell, 17–55. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1985.

- Muhtadi, Burhanuddin. Vote Buying in Indonesia: The Mechanics of Electoral Bribery. Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan, 2019.

- Muhtadi, Burhanuddin, and Eve Warburton. “Inequality and Democratic Support in Indonesia.” Pacific Affairs 93, no. 1 (2020): 31–58. doi:10.5509/202093131.

- Mujani, Saiful, William R. Liddle, and Kuskridho Ambardi. Voting Behavior in Indonesia since Democratization: Critical Democrats. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

- Norris, Pippa, and Joni Lovenduski. Political Recruitment: Gender, Race and Class in the British Parliament. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press., 1995.

- OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development). “Indonesia Country Note: Education at a Glance.” 2018. http://gpseducation.oecd.org/Content/EAGCountryNotes/IDN.pdf

- Pitkin, Hanna. The Concept of Representation. Berkeley: University of California, 1967.

- Poczter, Sharon, and Thomas B. Pepinsky. “Authoritarian Legacies in Post-New Order Indonesia: Evidence from a New Dataset.” Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 52, no. 1 (2016): 77–100. doi:10.1080/00074918.2015.1129051.

- Rehm, Philipp. “Risk Inequality and the Polarized American Electorate.” British Journal of Political Science 41, no. 2 (2011): 363–387. doi:10.1017/S0007123410000384.

- Robison, Richard. Indonesia: The Rise of Capital. North Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 1986.

- Robison, Richard, and Vedi R. Hadiz. Reorganising Power in Indonesia: The Politics of Oligarchy in an Age of Markets. London; New York: Routledge, 2004.

- Rosset, Jan, Nathalie Giger, and Julian Bernauer. “More Money, Fewer Problems? Cross-Level Effects of Economic Deprivation on Political Representation.” West European Politics 36, no. 4 (2013): 817–835. doi:10.1080/01402382.2013.783353.

- Schakel, Wouter, and Armen Hakhverdian. “Ideological Congruence and Socio-Economic Inequality.” European Political Science Review 10, no. 3 (2018): 441–465. doi:10.1017/S1755773918000036.

- Slater, Dan, and Erica Simmons. “Coping by Colluding: Political Uncertainty and Promiscuous Powersharing in Indonesia and Bolivia.” Comparative Political Studies 46, no. 11 (2013): 1366–1393. doi:10.1177/0010414012453447

- Walczak, Agnieszka, and Wouter van der Brug. “Representation in the European Parliament: Factors Affecting the Attitude Congruence of Voters and Candidates in the EP Elections.” European Union Politics 14, no. 1 (2013): 3–22. doi:10.1177/1465116512456089.

- Warburton, Eve. “Indonesia: Why Economic Nationalism Is So Popular.” Lowy Interpreter, 2015. https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/indonesia-why-economic-nationalism-so-popular

- Winters, Jeffrey A. “Oligarchy and Democracy in Indonesia.” Indonesia 96, no. 1 (2013): 11–33. doi:10.5728/indonesia.96.0099.

- World Bank. A Perceived Divide: How Indonesians Perceive Inequality and What They Want Done about It. November, 2015. http://pubdocs.worldbank.org/en/16261460705088179/Indonesias-Rising-Divide-English.pdf