Abstract

Building on the conceptualisation of ‘the local’ in gender and development discourse, we explore how national and sub-national policy actors in Uganda perceive gender equality policy in the context of agriculture and climate change, to assess the potential of localised solutions to achieve gender equality. Using data from national and sub-national policy actors in Uganda (37 semi-structured interviews, 78 questionnaires), the study found that policy actors largely adhered to global gender discourses in proposing context-specific solutions to gender inequality. Our results show that although local actors identified local norms and culture as major barriers to gender equality, their proposed solutions did not address local gender norms, focussed on formal policy and did little to address underlying causes of gender inequalities. Based on the findings, we suggest that ‘the local’ should be reconstructed as a deliberative space where a wide variety of actors, including local feminist organisations, critically engage, assess and address local gender inequality patterns in agriculture and climate change adaptation processes.

Introduction

In climate change discourse for the agricultural sector, the global and the local are inevitably intertwined, often framed as cause and consequence, correspondingly (Faiyetole and Adesina Citation2017). Globally, agriculture, forestry and related land-use changes are responsible for 23% of total anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions (IPCC Citation2019). At the same time, climate change effects on agriculture are location specific, so that locally appropriate solutions are seen as necessary for successful adaptation and mitigation strategies (UNDP Citation2019). In the case of gender, the emphasis on the local is framed as equally important, as gender relations are highly contextual, socially constructed in each location, and also changing through time (Manicom Citation2001). In climate change adaptation strategies, valuing local knowledge is, for example, seen as fundamental to avoid developing adaptive technologies that are not appropriate for the context or that might reproduce pre-existing gender inequalities (Gonda Citation2016; Huyer Citation2016).

However, in international development, transnational and top-down approaches to gender equality have often failed to capitalise on locally formulated and prioritised gender strategies (Brouwers Citation2013). This is problematic because the institutions and people implementing gender-equality strategies at national and sub-national levels are also gendered entities operating within certain normative and cultural environments, which inevitably affects implementation (Alston Citation2014; Walby Citation2005). Improved knowledge of local understandings and practices of ‘doing gender’ could shed light on inherent tensions that may hamper the transformational potential of global strategies (Wittman Citation2010).

The internationally agreed globalised norms for gender equality that guide gender-equality discourses and actions worldwide are often presented as incapable of creating change in deep-seated local power relations (Alston Citation2014; Smyth Citation2010; Wittman Citation2010), which are seen as requiring localised approaches (Ün Citation2019). Designing more effective gender-equality strategies may require close examination of local gender-normative positions and engagement with practices proposed by policy actors working in these contexts (Østebø Citation2015; Ün Citation2019). The promise of localisation is thus premised on the notion that local approaches to tackle gender inequality will ease the tensions between local and global understandings of gender by proposing context-specific strategies that will ultimately be more effective.

In this study, we engage with this promise of localisation, examining gender-equality strategies originating from local policy actors to assess the potential of ‘the local’ in designing more effective and transformative gender policy. How do local policy actors problematise gender inequality in agriculture and climate change adaptation, and what localised solutions do these actors propose? How do these problematisations and solutions differ from those found in international spheres?

We explore these issues by examining the meanings attached to gender inequality and its translation into local policy and projects by national and sub-national policy actors in the agricultural sector in Uganda in the context of a changing climate. Considering the localised effects of climate change in agricultural systems, the pervasive and contextualised gender inequalities in the agricultural sector, and the threat of climate change widening these inequalities (Huyer et al. Citation2020), studying the promise of ‘the local’ within this context is highly relevant. We interrogate perceived causes of gender inequalities and proposed local prescriptions for translating these into policy, and we examine the extent to which different global and local norms are mobilised in their understandings of gender equality. Uganda presents an interesting case to investigate these issues because the apparent dominance of gender equality in agriculture and climate change policy documents, largely informed by global discourses, is often met with policy inaction (Acosta et al. Citation2019a; Ampaire et al. Citation2020). In such contexts, would considering locally proposed solutions help to identify more effective strategies?

The rise of ‘the local’ in international development

The rise of ‘the local’ – which we refer to as the emergence and establishment of the normative appreciation of local knowledge, ownership and solutions – in development emerged largely in the mid-1990s in response to the failure of traditional ‘top-down’ approaches to development. Bräuchler and Naucke (Citation2017, 426) define ‘the local’ as a ‘concrete context of practical appropriation, interpretation and transformation of socio-cultural discourses, ideas and practices that have their roots in global, regional and local interests, traditions and actors’. ‘The local’ is often framed in terms of space (Escobar Citation2001) and as a concept that is constantly evolving and continually influenced by both local and global factors (Bräuchler and Naucke Citation2017; Zimmermann Citation2014).

Here, we consider ‘the global’ as the context where international and national organisations debate and establish understandings or discourses to guide development and security actions worldwide. The United Nations plays a fundamental role in this endeavour, seeking to ‘harmonize the actions of nations’ to achieve development (United Nations Citation1945). For example, the 17 Sustainable Development Goals set common standards and goals among private businesses, development agencies, donors and nongovernmental organisations (NGOs) globally.

United Nations agencies, donors and international organisations generally emphasise ‘the local’ in their discourse, presenting locally adapted solutions as crucial for effective development (Kyamusugulwa Citation2013). This is often framed as the need to empower local actors to design their own collective responses to development challenges – enabling ‘bottom-up’ policies (Crescenzi and Rodríguez-Pose Citation2011). Paradoxically, globalised approaches to development have shifted the focus of local development policy towards addressing the demands of donors and international NGOs, at the expense of project communities’ priorities (Groves Citation2013; Hellmüller Citation2012; Lie Citation2019; Richmond Citation2012). Marsden (Citation2013, 106) asserted that such globalised approaches to development, ‘far from being mechanisms for embracing the voices of the poor, […] have used a form of communication that has excluded the very people whom they claim to serve’.

These observations are especially relevant because local actors’ reluctance to engage with approaches that might be considered ‘divisive, threatening, or burdensome’ is a major reported cause of development initiatives failing (Reed et al. Citation2019). Unsurprisingly, diffusion strategies for global norms that consider local sensitivities and act through local actors are thought to be more effective than those without these considerations (Acharya Citation2004). Flint and zu Natrup (Citation2019, 208) argue that development aid delivery could be greatly improved through a stronger focus on ‘locally rooted, user-driven development solutions that originate from the beneficiaries themselves’. Approaches focussing on local knowledge and solutions and increasing local ownership of development projects are seen as an alternative to global development approaches (Crescenzi and Rodríguez-Pose Citation2011). Prioritising ‘the local’ aims to reduce international influence in development matters by giving more weight to local perspectives and less to development donors’ policies and priorities (Arensman, van Wessel, and Hilhorst Citation2017; Lie Citation2019). Furthermore, decentralised governance systems have also partly allowed for the transfer of policy authority, power, responsibility and services from central to local governments, thereby reducing national influence in localised settings and thus providing local governments with more independence (Ahikire Citation2007). However, in many contexts, local governments are still expected to implement national policy and follow national guidelines when managing, designing and implementing local policies (Ampaire et al. Citation2017). Moreover, in countries such as Uganda where the decentralised governance system operates within upward forms of accountability, and where local revenue sources have been abolished, local autonomy and capacity to operate independently often suffer (Agarwal et al. Citation2012; Ampaire et al. Citation2017).

Within gender and development discourses, global strategies for gender equality, such as gender mainstreaming, are often perceived as high-level policy constructions being enforced in different contexts without much consideration of contextual particularities (Brouwers Citation2013; Spivak Citation1996; Ün Citation2019). Bridging the gap between local normative stances, where gender inequality is often naturalised, and global norms for gender equality is especially important in contexts like Uganda, characterised by frequent conflict between multiple normative environments where gender equality and gender relations are constructed (eg customary practices of inheritance vs. formal regulatory frameworks and global gender policy) (Acosta et al. Citation2019b, Citation2019a). Brouwers (Citation2013, 32) has emphasised the importance of context, arguing that ‘locally formulated priorities’ and the ‘involvement of and ownership by partner countries’ are essential for effective gender policy in development initiatives. In decentralised governance systems, bridging the gap between local normative stances and nationally mandated gender policy becomes fundamental in cases where local political elites might apparently engage with gender equality discourse but in practice pursue partial interests and act within the limits of community culture, resulting in continued discrimination and subordination of women (Ahikire Citation2007; Tripp and Kwesiga Citation2002).

The localisation of gender norms often entails meaning moulding (Lombardo, Meier, and Verloo Citation2009), ie processes through which terminologies and discourses are adjusted to fit local understandings and conditions. For example, in a study on the localisation of gender norms, Ün (Citation2019) showed how a conservative women’s organisation in Turkey advanced the norm of ‘gender justice’. It built on the notion of gender equivalence, as an alternative to gender equality, and contested the moral validity of global gender-equality norms, which did not align well with local beliefs and practices. Similarly, Petersen (Citation2018) showed how Islamic Relief Services expanded gender-focussed projects to include all women-sensitive projects, resonating with local audiences who did not support global gender norms, and used new interpretations of Qur’anic verses to advance gender justice and non-violence. An understanding of ‘the local’ can not only increase the receptiveness of gender programmes but also improve gender equality at the local level. For example, Rajeshwari, Deo, and van Wessel (Citation2020) showed how a capacity development programme of women’s elective representatives in village councils in India was able to support the development of a form of autonomy that centred on women’s own identities and situations, through a localised programme design.Footnote1

The present study aims to contribute to discussions on norm localisation and its promised potential to advance gender equality. Using the case of agricultural policies to address climate change in Uganda, this study explores gender norm formation and localisation by investigating the extent to which inherent tensions between naturalised local discourses and global gender-equality strategies could be bridged through locally proposed solutions to gender inequality. We begin with a summary of the study methods and then introduce the findings, elaborating on the local meanings of gender inequality in agriculture and climate change and on the extent to which ‘the local’ and ‘the global’ are mobilised in addressing these inequalities. Finally, we contextualise and interpret the findings and explore their policy and practice implications.

Methodology

We used a discourse analytical perspective (Wagenaar Citation2015; Leipold et al. Citation2019) to explore policy actors’ presentations of current challenges to gender equality and proposed solutions for the rural and agricultural sector in Uganda, in the context of a changing climate. Here, we understand discourses and meanings to both reflect and mould policy actors’ positions on policy matters (Wagenaar Citation2015); actors can simultaneously influence and be influenced by discourse. We conducted 37 semi-structured interviews and administered 78 questionnaires among policy actors in Uganda’s capital, Kampala, and in the districts of Nwoya (northwest), Luwero (central), Rakai (southwest) and Mbale (east). The sample was expected to articulate understandings, interpretations and perspectives from the national, district and sub-county level, in what we denominate ‘the local’. ‘The local’ thus is used in this article in juxtaposition to ‘global’ to denote a context that is significantly more integrated in communities of spatial proximity than in transnational communication processes, while acknowledging the possibility of a gradual relationship between levels and the prevalence of either ‘local’ or ‘global’ integration and orientation. provides an overview of the interviews and questionnaires.

Table 1. Numbers of semi-structured interviews and questionnaires completed by location.

From October 2017 to January 2018, self-administered questionnaires were completed during national and sub-national multi-stakeholder platform discussions, most of which were organised by Learning Alliances on Agriculture and Climate Change – multi-stakeholder forums for policy actors to discuss context-specific climate change adaptation strategies for the agricultural sector. Our participation in these Learning Alliances from their inception provided a unique research opportunity. Respondents included government actors (from local governments, ministries and the Ugandan Parliament) and non-government actors (NGOs, research institutes and civil society organisations). The questionnaire included open-ended and closed questions.

The semi-structured interviews were conducted in November and December 2017 with policy actors working in formal national government structures (six interviews: the Ministries of Agriculture, Animal Industry and Fisheries; Water and Environment; Finance; and Gender, Labour and Social Development; the Equal Opportunity Commission; and the Ugandan Parliament), district government (14 interviews), and sub-county government (nine interviews). We also conducted eight interviews with representatives from a development agency (German Society for International Cooperation), non-profit organisations operating at district and national levels (eg Hanns R. Neumann Stiftung, Association of Uganda Professional Women in Agriculture and Environment), and Makerere University faculty. Interviewees were asked about challenges to addressing gender inequalities in Ugandan agriculture within the context of a changing climate, and about potential solutions that their offices could use to advance gender equality locally. Interview questions were open-ended and broad, encouraging the free sharing and elaboration of opinions and experiences. With the respondents’ permission, the interviews were recorded and fully transcribed.

Interviewees were purposively selected to obtain instances of actors working within the realms of agriculture and climate change in rural areas of Uganda. Again, most of the interviewees were part of or had been involved in the Learning Alliances on Agriculture and Climate Change. In this way, this research constitutes a case study representing the views and perspectives of the actors in these learning alliances with regards to local solutions to gender inequality in agriculture within a climate change context.

The open-ended questions in the questionnaire and the semi-structured interviews asked policy actors to propose, in their own organisational context, locally appropriate solutions to gender inequality in agriculture and climate change. ‘Locally appropriate solutions’ therefore means solutions that the study participants thought their organisations could develop or implement. This allowed us to examine, through the respondents’ discourses, how gender policy meanings were locally constructed, consolidated and/or challenged. The first author spent 36 months in Uganda in close interaction with many of these policy actors, which helped with the context-specific interpretation of their discourses.

We analysed the interview transcripts and questionnaire responses using an inductive codes-to-theory model (Saldaña Citation2013). First, we categorised the challenges to gender equality and the solutions envisioned to address them. In a second round of coding, we examined the extent to which these challenges and perceived solutions directly addressed changing local patriarchal gender norms, how they were translated into local policy, and whether these translations and attached meanings resonated with or provided alternative understandings for global gender strategies. The analysis involved iteratively exploring several questions: How are local problematisations of gender in climate change portrayed? What localisations are constructed? How are global norms and actors presented in the discourse?

Background

The Republic of Uganda’s governance system encompasses central and local governments operating within a decentralised structure. In rural areas, local governments comprise district councils, which encompass sub-county councils, parish councils and village councils. Local governments design their own development plans addressing the main development issues affecting their districts or sub-counties, which must comply with nationally set strategic directions.

Uganda’s legal and policy framework provides a substantial basis for promoting gender equality. Uganda’s Constitution (1995) grants equal status to all citizens, promotes affirmative-action policies, and protects women’s rights against patriarchal practices. Uganda Vision 2040, the Second National Development Plan 2015/16–2019/20, the Uganda Gender Policy (2007) and several parliamentary actsFootnote2 also promote equality and equity. Moreover, the Public Finance Management Act (2015) requires ministries, local governments and national agencies to address gender issues in their activities. The National Climate Change Policy (2015) prioritises mainstreaming gender issues in climate change adaptation and mitigation and highlights the importance of gender-sensitive indicators. Similarly, the National Guidelines for the Integration of Climate Change in Sector Plans and Budgets (2014), include ‘gender sensitiveness’ as a key criterion in adaptation, while the Uganda Climate-Smart Agriculture Country Program (2015–2025) proposes fostering agriculture through gender-sensitive practices. Uganda is also a signatory to regional and international mandates advocating gender equality, eg the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948), the Convention on Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (1979), the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action (1995), the African Union Solemn Declaration on Gender Equality in Africa (2003), the Sustainable Development Goals (2015), and the East Africa Community Gender Equality and Development Act (2017).

Results

Perceived importance of gender equality in agriculture and climate change policymaking

Gender equality is central in Uganda’s legal and policy framework, and it was similarly prominent in local policy actors’ discourse. All participating policy actors actively engaged with the topic of gender equality in agriculture and climate change, demonstrating that the discourse had permeated all governance levels. The interviews showed that gender inequality was considered an important issue to address. As one NGO actor remarked, ‘Gender is very relevant […]. We put gender into every development work that we do; we see that it puts a barrier for development’. Similarly, a government official from Luwero claimed, ‘For us, it is very important that those gender considerations are integrated in all projects and programmes’. Generally, policy actors at both national and sub-national levels framed addressing ‘gender issues’ as fundamental for improving well-being at the household and national level:

Gender becomes very important because our mandate is to see that farmers’ households improve and livelihood in terms of food security and income. So, in that regard, the man and the woman have to work together complementing one another so that they achieve that. (NGO representative, Nwoya District)

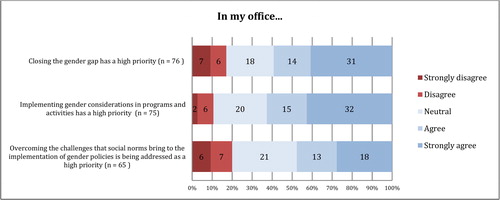

The questionnaire responses confirmed this prioritisation of gender issues in agriculture and climate change adaptation. Examining policy actors’ perceptions of their offices’ prioritisation of gender issues, most respondents agreed (fairly to strongly) that closing the gender gap, considering gender in programmes and overcoming challenges to gender policy implementation caused by social norms were high priorities ().

Figure 1. Policy actors’ perceptions of their offices’ prioritisation of gender-related activities in Uganda.

Although gender-equality discourses seemed well established in Uganda, many interviewees saw this as foreign, with some framing gender-equality work as resulting from external influences:

A challenge we have in this country is, right from the time when gender was introduced in the 1980s, when the programmes started for women empowerment, people misunderstood the whole concept. They looked at it as if it is coming to put women above the men. Gender equality was misconceived. People still have that in their minds that when you talk about gender you are going to put women above the men and that women are going to become more radical. (NGO representative, Kampala)

Considering this perception of the gender-equality discourse in climate change and agriculture as an external influence, we now explore local actors’ conceptualisations of gender problems and gender implementation gaps in these fields.

Perceptions of gender problems and policy implementation gaps in agriculture and climate change

National and sub-national policy actors largely constructed gender inequality in agriculture and climate change as an important policy issue in Uganda. Two-thirds of responses to the open-ended questionnaire item on perceived priorities in addressing the causes of gender inequality fell into three categories: (1) changing negative mindsets and social norms and (2) improving gender responsiveness in policy were the most common responses, followed by (3) improving policymakers’ and the general public’s understanding of gender ().

Table 2. Perceptions of priorities for addressing the causes of gender inequality.

The influence of local cultural norms in perpetuating gender inequality in agriculture and climate change also frequently emerged during the interviews. The policy actors often saw local cultural norms as hindering gender equality in rural areas. An NGO official, discussing challenges in a project aiming to empower rural women that clashed with local understandings of appropriate gender roles, described the influence of local cultural norms as ‘a social, cultural tension […] a tension that is rather complex and sensitive’. Another respondent asserted: ‘Until people change their mindsets, some people still dwell on the cultural norms and the cultural mindsets. Unless the mindset is changed, the [gender] inequality will still be there’ (Alero sub-county officer, Nwoya District).

Influencing local cultural norms was thus constructed as a prerequisite for gender equality. Clashes between formal policy and local norms and culture were frequently mentioned in the interviews. For example, an NGO officer working in Rakai noted, ‘The policy documents may articulate the [gender] issues, but the documents may find a resistance from the culture itself, from the local community’. This local resistance was also at times framed not only as emerging from the local community itself but rather from local political leaders, who apparently adhered to gender equality discourse but were in practice not interested in implementing it:

It is the people who are involved in policymaking who are the problem. Most of the policymakers, if you have observed, are men and they still believe in that male dominance […]. They mention gender because they have to because it is their job, but most of them are not, like, really willing to let go, they don’t want to lose their power. It is a power struggle. And you know if people have power, they want to hold on to power. They don’t want any drop of their power to go off. They don’t want to lose power, they feel they should hold on this power. (NGO representative, Kampala)

Local policymakers and political leaders were in this way presented as obstructing an effective gender policy implementation in a decentralised system of governance. As one respondent from the Mbale District government asserted:

The problem in Uganda is that there is a lot of politics. Everything is being politicised. Whatever you do, there is political interference. You find that when a technical person goes to field, to implement a policy or law, there is interference from the politicians. […] The law is there and we are supposed to implement gender, but again, politicians don’t want to implement. They don’t want us to implement. When we try to implement we have problems with the politicians.

The clashes between formal policy and local norms and culture were partly explained by the nature of formal national policy, which was disconnected from local women’s realities in different Ugandan regions. There was a perceived need to further localise understandings of gender:

Uganda is a multi-ethnic country, and each ethnic group has different gender issues. The policy gives a general perspective, and it is upon the implementer to try to link what is in the policy to the reality on the ground. When the implementer fails to connect the policy, that is where you hear the complaint coming. (officer, Nwoya District local government)

The distance between local norms and formal national policies largely adhering to international standards and global discourses on gender equality was central in the local policy actors’ discourse. There was an implicit assumption that formal gender-equality policy was dissociated from practice:

It is like policy versus culture. The policy says ‘equality, gender, this and that’, but culture is different […]. The gender implementation gap is partly created by the culture. You cannot change culture overnight. It has to be gradual. You see, our culture puts the man above the woman. Culture is deeply rooted almost throughout the country, and to uproot it will need time. Even the people who are at ministry level at national level, they are all Ugandans and they are all attached to the same cultural beliefs. (officer, Nwoya District local government)

Indeed, in the interviews, policy actors often acknowledged the existence of two layers of policy. One layer was the formal gender policy and discourse to which the policy actors ostensibly adhered, but there was also an underlying layer heavily influenced by local norms, which was seen as obstructing the effective implementation of the formal policy:

There is a gap, I must admit, in the implementation. Even though the documents may be well aligned, the implementation is not according to what is written. Why? Because of our cultural inclinations, that we don’t want gender, we are opposed to gender inclusiveness. […] In this budget, as in the previous budget, you’ll find listed ‘gender mainstreaming’; we just do it year after year, year after year. We are like priests giving a sermon. (officer, Rakai District local government)

For the policymakers tasked with implementing gender mandates, ‘the global’ (formal gender-equality policies for agricultural development) interacted with ‘the local’ (cultural norms and beliefs). These respondents used the formal gender-equality jargon that resonated with global discourses but did not translate this into their local realities. Generally, the interviews and questionnaire responses lacked a specific and localised discourse on gender issues in agriculture and climate change.

The gender gap in climate change adaptation was also problematised in the interviews in relation to insufficient translation of formal national policies for specific locations:

The policy just gives a general view of what should be done in particular to address gender, but the implementers now should handle the nitty-gritties; they should customise that in their locality. The implementers, some of them have failed to conceptualise and customise to their own needs. To ensure that perhaps climate change resilience adoption increases in our community or to see the gender issues related to the adoption of practices, I would have to first of all understand the needs, the needs of the men and women in the area. What do they need? Then, my programming and mainstreaming of climate change adaptation and mitigation measures should reflect those needs. Once it reflects those needs, I don’t think we shall fail to implement the policy. (officer, Nwoya District local government)

This statement highlights how policy localisation may not materialise, with some policymakers failing to translate global ideas on gender equality into local policy. Local actors thus acknowledged a clash between generalised gender-equality discourses and local contexts, but efforts to bridge these tensions through local policy approaches were limited.

Gender inequality in agriculture and climate change was also often framed in terms of insufficient knowledge on gender issues (). This also emerged during the interviews. For example, a Member of the Ugandan Parliament attributed the reticence of some colleagues to implement or legislate gender issues to insufficient knowledge:

Gender and climate change in the agricultural sector of rural areas has not been a priority. It is a new field. You hear people say, ‘Is it necessary? Do we really need to consider those issues?’ I think there is a challenge of understanding how to integrate issues of gender and climate change in agriculture, in rural development. (Member of the Ugandan Parliament)

Inadequate implementation of existing policy was the most frequently cited factor perceived to influence the insufficient impact of formal gender policies in agriculture and climate change in Uganda (). The second most frequently cited factor was patriarchal mindsets and negative cultural norms preventing effective implementation.

Table 3. Perceptions of causes of insufficient impact of gender policies in agriculture and climate change.

Interviewees explained that the insufficient implementation of gender policy was partly linked to inadequate funding. As one local officer from Purongo sub-county (Nwoya District) put it, ‘These [gender] policies require financial support to be fully implemented, so if there is that gap, the implementation becomes somehow difficult’. A Luwero District policy officer also linked the gender implementation gap to financial constraints: ‘There is a big implementation gap. We want to reach communities, but we are unable to do that because of the environment we operate in. In a full financial year, you may not have any budget for gender’.

Contextualising gender inequality in terms of insufficient knowledge on gender issues and inadequate funds for implementation partly reflected a shallow politicisation of gender issues in the discourse, wherein local causes of gender inequality were disregarded or backgrounded. Nevertheless, policy actors remarked on the fundamental role of local norms and culture in achieving gender equality. Thus, although gender inequality in agriculture and climate change was constructed as a fundamental issue to be resolved through formal policy (see and ), differences between formal policy and local realities were considered a major barrier to effective policy implementation. In the next section, we interrogate local gender-equality strategies to assess the potential of ‘the local’ in designing more effective gender strategies in agriculture and climate change.

How are gender concerns transformed into policy prescriptions within ‘the local’?

Overall, proposed local solutions to gender inequality in the agricultural sector in the context of a changing climate were formulated in general terms and were largely expected to work through formal policy. shows the proposed actions for respondents’ institutions to take to address gender inequalities in their agricultural development activities. The proposed actions were wide-ranging, but most were concentrated in four areas: including women in policymaking and interventions (affirmative action), improving people’s understanding of gender, including gender in work plans and policy documents, and carrying out gender campaigns and advocacy.

Table 4. Proposed actions to address gender inequalities in agriculture and climate change.

Although our questionnaire asked about potential solutions to gender inequality in a very localised context (‘your office’), the proposed actions were mostly ambiguous, vague and not directly linked to the context. For example, under the category of ‘including women in policymaking and interventions’ (), there were answers such as, ‘Encouraging women and girls to get involved in most activities actively’; ‘Engage participation planning at various levels’; and ‘Engaging both sexes actively in government programmes’. The proposed solutions were brief, generalised statements that were not rooted or contextualised in the respondents’ local settings. While the brief responses might be due to the limited time respondents might have wanted to spend on answering the questionnaire, it was conspicuous that rather than bringing innovative local priorities to efforts to solve specific, contextualised gender inequalities, ‘the local’ was largely embedded in globalised gender-equality approaches.

Respondents’ descriptions of concrete actions that their institutions could take to address the gender policy implementation gap were also wide-ranging, with six main suggestions accounting for around half of the proposed actions: including gender laws and gender mainstreaming in work plans, improving the budget for gender, popularising policies, improving awareness and understanding of gender, carrying out gender campaigns and advocacy, and empowering women ().

Table 5. Proposed actions to address the gender policy implementation gap.

and show that the respondents felt that addressing gender inequality in agriculture and climate change requires improving gender knowledge, policy design and implementation. Culture and local norms were central to the problematisation of gender inequality (see section Perceptions of gender problems and policy implementation gaps in agriculture and climate change), but the proposed solutions did not emphasise addressing patriarchal cultural practices or local gender equality norms. These patterns emerged clearly around the issue of land ownership. In Uganda, women do not generally inherit land or have property rights over their husband’s land. These patriarchal norms were acknowledged as a major factor limiting women’s decision-making in agriculture. However, the actors’ proposed solutions naturalised these practices rather than challenging them:

In most cases, it’s the men marrying the women. If a man in a particular home brings a woman, then he has an upper hand in the family, more than the woman who has just come [from outside]. That’s where the scenario is. A woman, whether married or not, should try to own her own property as a woman. It is very good to try to make a positive mindset in the girls, to tell them, ‘Try to work hard. Try to make sure that in your lifetime you own property as a woman. Your property. Even if your husband is aware about it’. (officer, Rakai District local government)

The discourse thus naturalised unequal local land ownership norms, making women responsible for working hard to ‘earn’ land that they were not entitled to inherit or own through marriage. The patriarchal cultural practices, which the respondents acknowledged as the root cause of gender inequalities in agriculture, were not challenged. For example, a respondent from the Ministry of Gender, Labour and Social Development proposed replacing the term ‘gender’ with a word that would support traditional men’s and women’s roles to avoid rejection by local communities:

I think we need to simplify gender, and we should even stop calling it gender when we are talking to local people. We should talk about how we can support women, men, boys, and girls to play their roles effectively and sustain their livelihoods. When you talk about gender, they think ‘women’, and they become defensive. It is the patriarchal mindset. We need to package the gender message in a way that is palatable to communities. To deliver the message without diluting it but using a language that is encompassing.

This type of localisation – adhering to a generalised gender discourse but refraining from challenging local patterns of gender inequality – also appeared when respondents were asked what actions could be promoted in their offices to address challenges to gender equality created by strict social norms (). Around half of the proposed actions were in four areas: improving awareness and knowledge of gender among officers and the general public, increasing the budget for gender, including gender mainstreaming in work plans, and providing equal opportunities to men and women. The other 16 types of solutions/interventions were mostly proposed by only one respondent and framed in very generic terms. Especially considering that the questionnaire items were designed to elicit specific, concrete and context-specific solutions, the general responses may point to attempts to de-contextualise and generalise gender issues, or at least to a limited willingness to engage with the question. The questionnaire format may also have contributed, asking policy actors to capture the essence of their proposed actions in writing and in a limited amount of space, but such generalised gender statements were also frequently made in the interviews, suggesting that the questionnaire format had little or no effect.

Table 6. Proposed actions to address challenges to gender equality from rigid social norms.

Overall, the policy actors perceived patriarchal mindsets and negative cultural norms as fundamental challenges to advancing gender equality and effectively implementing gender policy in the agricultural sector ( and ). However, when questioned about potential local solutions for gender inequality (), the gender policy implementation gap () and challenges from rigid social norms (), respondents did not generally propose activities that would contest local social norms. This finding exposes a gap between perceptions of the importance of changing social norms and proposed activities to address gender inequality without attempting to challenge local norms and patterns of gender inequality. These answers correspond to a shallow politicisation of gender inequality by presenting it as an issue that should be addressed through itemised policies while local patterns of gender inequality and patriarchal gender norms and practices are not challenged, and are even naturalised.

A similar tendency was observed in the interviews. Awareness creation, capacity building and sensitisation on gender issues were frequently presented as a fundamental first step in advancing gender equality in agriculture and climate change by influencing local traditional culture. As an NGO representative from Nwoya District asserted, ‘The capacity building and gender equality awareness should increase to break that traditional culture perception towards women’. However, some respondents’ awareness-creation strategies did not clearly challenge local norms or patriarchal cultural practices. For example, an official from Luwero District requested women to remain submissive: ‘For me, when I talk to the rural women, I tell them, “You people be submissive to your husband, you listen to him. Gender just means working together, in harmony”’. Another official from Luwero District explained how the district government advocated for awareness creation on gender issues without challenging local norms:

At first when you are just introducing the concept of gender, it is not received positively, especially by the men, but as they get awareness, it gets better. When you talk of gender, especially here in Uganda, people think that you want women to be higher than men, [that] you want women to leave their domestic responsibilities or that they share the domestic responsibilities with men. But once you tell them it is not like that, that we are not telling women to leave their domestic responsibilities, that they can integrate their culture, and that they can leave their culture intact, the positive one, then they understand.

The above quote suggests that, when gender is introduced in the community as something that will not challenge established patriarchal norms, local people ‘understand’ and do not oppose the concept. Another strategy was proposed by an interviewee from the Ministry of Agriculture, Animal Industry, and Fisheries, who suggested that packaging and presenting ‘gender equality’ with a different terminology led to a lower rate of rejection from communities and from political leaders: ‘We are moving out of talking about “gender’ and trying to talk more about “equity”. They are more receptive to equity than to gender. Even if it’s quite similar’.

Although proposed solutions directly tackling the structural and cultural causes of gender inequality were rare, some were mentioned. These largely involved using cultural and political leaders to spearhead changes in cultural practices seen as detrimental to gender equality. A policy actor from the Ministry of Finance explained how cultural leaders could be key in changing gender relations:

Most of the time, gender is actually clashing with the cultural beliefs and practices. We are looking at how can we use cultural institutions to actually improve relationships between men and women. We want to focus on how to use cultural and religious institutions, those two, for them to understand what gender is all about. And then actually work with them to see how things can be done differently. Otherwise, without them there is no way we can win.

In a similar fashion, a Member of Parliament described convincing cultural leaders as the first step towards gender equality:

We need to use the cultural and religious leaders to get people’s buy-in. We have a lot of the religious leaders [who] still have a lot of influence on their followers. Once they understand the concept and inform others about it, it is very easy to convince them.

However, while these responses emphasised the potential of local leaders to effect gender-transformative change, how these leaders would be convinced to change their views remained unclear, especially considering that they are normally men and might not be inclined towards gender-equality mandates that often imply profound changes in local norms and culture. For example, an NGO official from the Nwoya district highlighted the resistance of clan leaders to consider issues regarding land ownership:

With the sensitisation on gender issues, it is just something you say sometimes, it is brought up, right, but it is a little bit hanging. At the moment we are planning to train particularly the women on land rights and related issues so this will help open people’s eyes, which is what we are supposed to do. But sometimes it is a bit tricky. Not only for the Acholi but also for other tribes, land is a cultural thing, traditional issues. You will find that clan leaders say that women don’t own land, that the land belongs to the clan.

A few interviewees referred to the potential of using local media to increase awareness of gender issues. A policy officer from Nwoya, for example, supported this approach, although the respondent remained vague regarding the extent to which local gender relations could be influenced: ‘Considering the limited resources at the district level, a way of disseminating information would be through radio programmes. We could disseminate from meteorological information for men and women, where to report cases of gender-based violence’.

Overall, and the interview results demonstrate that the proposed solutions to gender equality in agriculture and climate change were formulated in very general terms and did not aim for normative change to current gender activities in rural and agricultural development projects in Uganda. Local actors generally addressed gender issues in terms of policy, highlighting the need to improve gender in official policy, although formal policy was acknowledged to have a very limited effect on local norms and culture (see section Perceptions of gender problems and policy implementation gaps in agriculture and climate change). Further, the proposed local prescriptions to address gender inequality did not challenge patriarchal norms, so that politicisation remained shallow. Thus, ‘the local’, in this context, showed limited capacity to transform pervasive gender inequality patterns.

Discussion and conclusion

This study started from the assumption that the limited effectiveness of global gender equality strategies is partly explained by their failure to fully examine local understandings and preferred practices of the actors responsible for implementation in specific contexts (Wittman Citation2010). A focus on ‘the local’ was expected to shed light on the potential for a more bottom-up, localised approach to gender equality. However, we found that the local policy actors included in this study in Uganda, when devising potential context-specific solutions to gender inequality in agriculture and climate change, tended to adhere to global discourses on gender equality, with limited efforts to address structural causes of local gender inequality. In general, few actors attempted to translate policy for the local context, with both questionnaire and interview results showing local policy actors’ hesitation to challenge local norms that cause gender inequality. Furthermore, our empirical results point to gender equality as constituting a mostly depoliticised issue at the local level, with local cultural and political leaders having limited interest in engaging with gender equality, at least in agriculture and climate change adaptation. Translations of global gender equality norms and strategies to the ‘local’ stopped short of openly challenging local patterns of gender inequality or aiming to disrupt local gender power relations, but rather naturalised gender inequality. This resonates with the findings of Ahikire (Citation2007) and Acosta et al. (Citation2019b, Citation2019a) in Uganda and Beall (Citation2005) in Southern Africa, who found that gender equality is not sufficiently institutionalised in local politics and tends to operate within the limits of community culture.

Global discourses on gender equality in agriculture and climate change are based on the premise that unequal power relations between men and women are detrimental to advancing rural women’s status and to improving development outcomes and egalitarian climate change adaptation and mitigation strategies (World Bank, FAO, and IFAD Citation2015). Aiming to transform unequal gender relations, these global discourses challenge local patterns of gender inequality and also highlight the importance of ‘localisation’ – devising local solutions for specific contexts (UNDP Citation2019). However, when the local solutions fail to challenge patriarchal gender norms, the promise of localisation becomes limited.

The apparent adherence of local actors in this study to global discourses on gender equality supports previous research portraying ‘the local’ and ‘the global’ as being in constant interaction (Anderl Citation2016; Maags and Trifu Citation2019) and describing a strong influence of ‘the global’ on gender discussions in development contexts (Cold-Ravnkilde, Engberg-Pedersen, and Fejerskov Citation2018). Advancing knowledge of this local–global interaction in Uganda, our findings identify a shallow politicisation (Feindt, Schwindenhammer, and Tosun Citation2020) of gender equality, allowing local policy actors to adopt global discourses in narrowly designed and underfunded initiatives with very restricted implications for local gender relations. We thus found the promise of localisation to be limited, with local policy actors adhering to the global gender-equality discourse and recognising the normative tensions between global norms and local culture, while simultaneously presenting local gender relations as an uncontestable cultural aspect. ‘The local’ thus seemed to use ‘the global’ to appear to fulfil gender policy, while often accepting and sometimes even naturalising local patterns of gender inequalities. Although gender inequality in agriculture and climate change was problematised, proposed local solutions remained very general and vague. This resonates with Ruiz and Vallejo’s (Citation2019) work in Colombia, where gender discourse was prominent but proposed gender policies, actions and strategies lacked content and specificity.

Our study also exposed a disconnect between the stated importance of ‘the local’ in development (Crescenzi and Rodríguez-Pose Citation2011) and the global discourse on challenging patriarchal forms of gender discrimination through gender-transformative approaches (Deering Citation2019; Wong et al. Citation2019). We found this disconnection to be prominent in the highly patriarchal study context when asking local actors about transformative solutions for gender inequality that would challenge well-established local power relations. We found that local policy actors framed patriarchal social-cultural norms as a barrier to gender equality in agricultural and climate change development, but that these norms were largely backgrounded in proposed ‘local’ solutions. By constructing gender inequality as a policy problem resulting from an insufficient understanding of gender concepts or lacking gender integration in policy, local policy actors shifted the focus away from the root causes of gender inequality, pointing in this way to a shallow politicisation of gender issues (ie deflecting attention from the politicisation of deep-seated structural inequalities).

The present study thus reveals serious limitations of a focus on ‘the local’ in gender equality strategies, unless a strong feminist approach, where women’s interests and rights take centre stage, is included. In this sense, the role of local feminist movements in gender and norm localisation might be central to advancing a transformative gender-equality agenda, as they position themselves as able to formulate alternative, more contextualised solutions to gender equality (see eg Sen and Grown Citation1987). However, this requires local feminist movements to be connected and able to influence political authorities and policymakers (Ün Citation2019). Because our study focussed primarily on policy actors working in formal government structures, there was minimal representation of local feminist organisations. This may have limited our ability to examine the role and impact of such local actors in addressing local patterns of gender inequality. However, local feminist discourses did not seem to have significantly penetrated or influenced the discourses of policy actors working in formal government structures. This discursive disconnect between women’s right movements in Uganda and mainstream national and local politics was shown in Ahikire (Citation2007), where this disconnection implied that women’s rights movements were largely unable to significantly impact change towards gender equality in Uganda.

Our study raises questions about a focus on ‘the local’ as a site for more effective gender equality strategies in contexts where local policy actors tend to adhere to global development discourses but are simultaneously embedded in largely unchallenged patriarchal systems. We do not claim that local policy actors were generally inflexible or unwilling to improve gender equality in their contexts but rather aim to expose a situation where local actors largely problematised the structural causes perpetuating gender inequality, while the solutions proposed did not challenge these structural causes. To ensure a more transformative gender agenda, we argue for the need for local actors to devise strategies such as media and education programmes, awareness raising, and effective capacity building and leadership approaches (see eg Rajeshwari, Deo, and van Wessel Citation2020) that are able to effectively shift gender norms. Further, as mentioned above, key feminist movements and organisations, such as the Association of Uganda Professional Women in Agriculture and Environment and the Women Farmers Association of Uganda, have a fundamental role to play and need to be fully embedded in policy decision-making processes at the local level. Their close familiarity with the local realities of rural women and their years of involvement in situating women’s rights at the forefront of the policy agenda put them in a unique position to do so. However, for this to be effective, they will need to work hand in hand with other key agents for change that are already pioneering transformative gender equality strategies within local government structures (eg local feminist women councillors) to construct a strong bottom-up movement for cultural transformation.

We argue that there is a need to reconstruct ‘the local’ as a deliberative space where multiple actors – ideally, spearheaded by local feminist movements and including international and local NGOs, international development agencies, and national and sub-national government officials – critically engage with, assess and address local patterns of gender inequality. We conclude that change needs to emerge and be championed by this collective and feminist ‘local’, as we cannot expect change to materialise merely through gender policy that is perceived as foreign and out of touch with local norms and realities. Future studies on the role of ‘the local’ to close the gender gap could then investigate the potential of reflexive acts of collective argumentation and discussion (Feindt and Weiland Citation2018) in addressing local patterns of gender inequality, the extent to which cultural norms can act as invisible codes of conduct guiding the behaviour of local policymakers, and the conditions under which local policy actors are more prone to design transformative gender strategies in their communities.

Acknowledgements

This work was implemented as part of the CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS), which is carried out with support from CGIAR Fund Donors and through bilateral funding agreements. For details please visit https://ccafs.cgiar.org/donors. The views expressed in this document cannot be taken to reflect the official opinions of these organisations. The authors would like to thank all the study participants for their time and willingness to be part of this research, and the two anonymous reviewers for their insightful suggestions to improve the clarity and quality of the manuscript. The authors appreciate all the support received from Dr Edidah Ampaire and Perez Muchunguzi during the course of this research project, as well as the assistance of Sylivia Kyomugisha during data collection and audio transcription.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Mariola Acosta

Dr Mariola Acosta is a gender consultant at the Inclusive Rural Transformation and Gender Equity Division at the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Previously, she conducted her research at the Strategic Communication Chair Group of Wageningen University & Research, the International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (IITA) in Uganda, and the Alliance of Bioversity International and CIAT. Her research explores the gender inclusiveness of agriculture and climate change adaptation policies and investigates the impact of local meaning in the performance of gender policy and practice in the Global South.

Margit van Wessel

Dr Margit van Wessel is an Assistant Professor at the Strategic Communication Chair Group, Wageningen University & Research, the Netherlands. She researches and teaches on manifestations of citizenship and civil society, focussing on dynamics between citizens and political and governmental institutions and processes. Most of her publications are on civil society advocacy and advocacy evaluation, with recent articles in Voluntas, World Development, Evaluation and Development Policy Review.

Severine van Bommel

Dr Severine van Bommel is the leader of the Rural Development Group in the School of Agriculture and Food Sciences, the University of Queensland. Holding a PhD in communication and innovation studies from Wageningen University, she is an interdisciplinary social scientist specialising in the relationship between people and their environment in agriculture and natural resource management.

Peter H. Feindt

Dr Peter H. Feindt is a Professor of agricultural and food policy at the Thaer Institute for Agricultural and Horticultural Sciences at Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin. Previously, he was a professor of strategic communication at Wageningen University (2013–2017), a senior lecturer/reader for environmental policy and planning at Cardiff University (2007–2013) and a senior researcher at University of Hamburg (2000–2007). He holds a PhD in political science, and his research addresses a broad range of questions in agricultural and food policy, in particular links to environmental policy, sustainability transitions and the resilience of farming systems. He is a member of the German Bioeconomy Council and the Scientific Advisory Council for Agricultural and Food Policy at the German Ministry of Food and Agriculture. He chairs the Scientific Advisory Council for Biodiversity and Genetic Resources at the same ministry.

Notes

1 The authors speak of ‘narrative autonomy’: ‘individuals’ narrative interpretations as they reveal or create the meaning of their own identity and situation, creatively draw on available materials, and discern courses of action true to these interpretations’ (Rajeshwari, Deo, and van Wessel Citation2020, 1).

2 The Equal Opportunities Commission Act, 2007; The Local Governments Act, Cap. 243; The National Women’s Council Act, Cap. 318; The Land Act, Cap. 227; The Public Finance Management Act, 2015; and The Local Government Act (1996).

Bibliography

- Acharya, A. 2004. “How Ideas Spread: Whose Norms Matter? Norm Localization and Institutional Change in Asian Regionalism.” International Organization 58 (2): 239–275. doi:10.1017/S0020818304582024.

- Acosta, Mariola, Margit van Wessel, Severine van Bommel, Edidah L. Ampaire, and Laurence Jassogne. 2019a. “The Power of Narratives: Explaining Inaction on Gender Mainstreaming in Uganda’s Climate Change Policy.” Development Policy Review 38 (5): 555–574.

- Acosta, Mariola, Severine van Bommel, Margit van Wessel, Edidah L. Ampaire, Laurence Jassogne, and Peter H. Feindt. 2019b. “Discursive Translations of Gender Mainstreaming Norms: The Case of Agricultural and Climate Change Policies in Uganda.” Women’s Studies International Forum 74: 9–19. doi:10.1016/j.wsif.2019.02.010.

- Agarwal, A., N. Perrin, A. Chhatre, C. S. Benson, and M. Kononen. 2012. “Climate Policy Processes, Local Institutions, and Adaptation Actions: Mechanisms of Translation and Influence: Climate Policy Processes, Local Institutions, and Adaptation Actions.” Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change 3 (6): 565–579. doi:10.1002/wcc.193.

- Ahikire, J. 2007. Localised or Localising Democracy: Gender and Politics of Decentralisation in Contemporary Uganda. Fountain Publishers.

- Alston, M. 2014. “Gender Mainstreaming and Climate Change.” Women’s Studies International Forum 47: 287–294. doi:10.1016/j.wsif.2013.01.016.

- Ampaire, Edidah L., Mariola Acosta, Sofia Huyer, Ritah Kigonya, Perez Muchunguzi, Rebecca Muna, Laurence Jassogne, et al. 2020. “Gender in Climate Change, Agriculture, and Natural Resource Policies: Insights from East Africa.” Climatic Change 158 (1): 43–60. doi:10.1007/s10584-019-02447-0.

- Ampaire, Edidah L., Laurence Jassogne, Happy Providence, Mariola Acosta, Jennifer Twyman, Leigh Winowiecki, Piet van Asten, et al. 2017. “Institutional Challenges to Climate Change Adaptation: A Case Study on Policy Action Gaps in Uganda.” Environmental Science & Policy 75: 81–90. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2017.05.013.

- Anderl, F. 2016. “The Myth of the Local: How International Organizations Localize Norms Rhetorically.” The Review of International Organizations 11 (2): 197–218. doi:10.1007/s11558-016-9248-x.

- Arensman, B., M. van Wessel, and D. Hilhorst. 2017. “Does Local Ownership Bring about Effectiveness? The Case of a Transnational Advocacy Network.” Third World Quarterly 38 (6): 1310–1326. doi:10.1080/01436597.2016.1257908.

- Beall, J. 2005. Decentralizing Government and Centralizing Gender in Southern Africa: Lessons from the South African Experience. Ottawa, Canada: IDRC.

- Bräuchler, B., and P. Naucke. 2017. “Peacebuilding and Conceptualisations of the Local.” Social Anthropology 25 (4): 422–436. doi:10.1111/1469-8676.12454.

- Brouwers, R. 2013. “Revisiting Gender Mainstreaming in International Development.” Goodbye to an illusionary strategy (Working Paper No. 556). ISS Working Paper Series/General Series.

- Cold-Ravnkilde, S. M., L. Engberg-Pedersen, and A. M. Fejerskov. 2018. “Global Norms and Heterogeneous Development Organizations: Introduction to Special Issue on New Actors, Old Donors and Gender Equality Norms in International Development Cooperation.” Progress in Development Studies 18 (2): 77–94. doi:10.1177/1464993417750289.

- Crescenzi, R., and A. Rodríguez-Pose. 2011. “Reconciling Top-down and Bottom-up Development Policies.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 43 (4): 773–780. doi:10.1068/a43492.

- Deering, K. 2019. “Gender-Transformative Adaptation From Good Practice to Better Policy.” https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/CARE_Gender-Transformative-Adaptation_2019.pdf.

- Escobar, A. 2001. “Culture Sits in Places: Reflections on Globalism and Subaltern Strategies of Localization.” Political Geography 20 (2): 139–174. doi:10.1016/S0962-6298(00)00064-0.

- Faiyetole, A. A., and F. A. Adesina. 2017. “Regional Response to Climate Change and Management: An Analysis of Africa’s Capacity.” International Journal of Climate Change Strategies and Management 9 (6): 730–748. doi:10.1108/IJCCSM-02-2017-0033.

- Feindt, P., and S. Weiland. 2018. “Reflexive Governance: Exploring the Concept and Assessing Its Critical Potential for Sustainable Development Introduction to the Special Issue.” Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 20 (6): 661–674. doi:10.1080/1523908X.2018.1532562.

- Feindt, P. H., S. Schwindenhammer, and J. Tosun. 2020. “Politicization, Depoliticization and Policy Change: A Comparative Theoretical Perspective on Agri-Food Policy.” Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice: 1–17. Forthcoming. doi:10.1080/13876988.2020.1785875.

- Flint, A., and C. M. zu Natrup. 2019. “Aid and Development by Design: Local Solutions to Local Problems.” Development in Practice 29 (2): 208–219. doi:10.1080/09614524.2018.1543388.

- Gonda, N. 2016. “Climate Change, “Technology” and Gender: “Adapting Women” to Climate Change with Cooking Stoves and Water Reservoirs.” Gender, Technology and Development 20 (2): 149–168. doi:10.1177/0971852416639786.

- Groves, L. 2013. Inclusive Aid: Changing Power and Relationships in International Development. 1st ed. London: Routledge. URL (consulted September 2019): https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/9781849771702.

- Hellmüller, S. 2012. “The Ambiguities of Local Ownership: Evidence from the Democratic Republic of Congo.” African Security 5 (3–4): 236–254. doi:10.1080/19392206.2012.732896.

- Huyer, S. 2016. “Closing the Gender Gap in Agriculture.” Gender, Technology and Development 20 (2): 105–116. doi:10.1177/0971852416643872.

- Huyer, S., M. Acosta, T. Gumucio, and J. I. J. Ilham. 2020. “Can we Turn the Tide? Confronting Gender Inequality in Climate Policy.” Gender & Development 28 (3): 571–591. doi:10.1080/13552074.2020.1836817.

- IPCC. 2019. “Climate Change and Land: An IPCC Special Report on Climate Change, Desertification, Land Degradation, Sustainable Land Management, Food Security, and Greenhouse Gas Fluxes in Terrestrial Ecosystems.” https://www.ipcc.ch/srccl/.

- Kyamusugulwa, P. M. 2013. “Local Ownership in Community-Driven Reconstruction in the Democratic Republic of Congo.” Community Development 44 (3): 364–385. doi:10.1080/15575330.2013.800128.

- Leipold, S., P. Feindt, G. Winkel, and R. Keller. 2019. “Discourse Analysis of Environmental Policy Revisited: Traditions, Trends, Perspectives.” Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 21 (5): 445–463. doi:10.1080/1523908X.2019.1660462.

- Lie, J. H. S. 2019. “Local Ownership as Global Governance.” The European Journal of Development Research 31 (4): 1107–1125. doi:10.1057/s41287-019-00203-9.

- Lombardo, E., P. Meier, and M. Verloo, eds. 2009. The Discursive Politics of Gender Equality: Stretching, Bending, and Policy-Making, Routledge/ECPR Studies in European Political Science. Abingdon, Oxon, NY: Routledge.

- Maags, C., and I. Trifu. 2019. “When East Meets West: International Change and Its Effects on Domestic Cultural Institutions.” Politics & Policy 47 (2): 326–380. doi:10.1111/polp.12296.

- Manicom, L. 2001. “Globalising “Gender” in – or as – Governance? Questioning the Terms of Local Translations.” Agenda 16 (48): 6–21. doi:10.2307/4066509.

- Marsden, R. 2013. “Exploring Power and Relationships: A Perspective from Nepal.” In Inclusive Aid: Changing Power and Relationships in International Development, edited by L. Groves, 1st ed., 97–107. London: Routledge. URL (consultedSeptember 2019): https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/9781849771702.

- Østebø, M. T. 2015. “Translations of Gender Equality among Rural Arsi Oromo in Ethiopia.” Development and Change 46 (3): 442–463.

- Petersen, M. J. 2018. “Translating Global Gender Norms in Islamic Relief Worldwide.” Progress in Development Studies 18 (3): 189–207. doi:10.1177/1464993418766586.

- Rajeshwari, B., N. Deo, and M. van Wessel. 2020. “Negotiating Autonomy in Capacity Development: Addressing the Inherent Tension.” World Development 134: 105046. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105046.

- Reed, J., J. Barlow, R. Carmenta, J. van Vianen, and T. Sunderland. 2019. “Engaging Multiple Stakeholders to Reconcile Climate, Conservation and Development Objectives in Tropical Landscapes.” Biological Conservation 238: 108229. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2019.108229.

- Richmond, O. P. 2012. “Beyond Local Ownership in the Architecture of International Peacebuilding.” Ethnopolitics 11 (4): 354–375. doi:10.1080/17449057.2012.697650.

- Ruiz, F. J., and J. P. Vallejo. 2019. “The Post-Political Link between Gender and Climate Change: The Case of the Nationally Determined Contributions Support Programme.” Contexto Internacional 41 (2): 327–344. doi:10.1590/s0102-8529.2019410200005.

- Saldaña, J. 2013. “An Introduction to Codes and Coding.” In The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers, 2nd ed., 2–40. Los Angeles: SAGE.

- Sen, G., and C. Grown. 1987. Development, Crises, and Alternative Visions: Third World Women’s Perspectives, New Feminist Library. New York: Monthly Review Press.

- Smyth, I. 2010. “Talking of Gender: Words and Meanings in Development Organisations.” In Deconstructing Development Discourse: Buzzwords and Fuzzwords, edited by A. Cornwall and D. Eade, 143–152. Rugby, Warwickshire, UK : Oxford: Practical Action Pub., Oxfam.

- Spivak, G. C. 1996. “‘Woman’ as Theater: United Nations Conference on Women, Beijing 1995.” Radical Philosophy 75 (3): 1–4.

- Tripp, A. M., and J. C. Kwesiga, eds. 2002. The Women’s Movement in Uganda: History, Challenges, and Prospects. Kampala: Fountain Publishers.

- Ün, M. B. 2019. “Contesting Global Gender Equality Norms: The Case of Turkey.” Review of International Studies 45 (5): 828–847.

- UNDP. 2019. Local Solutions: Adapting to Climate Change in Small Island Developing States. New York: UNDP.

- United Nations. 1945. “Purposes and Principles.” Chapter 1. In Charter of the United Nations. New York: United Nations Security Council.

- Wagenaar, H. 2015. Meaning in Action: Interpretation and Dialogue in Policy Analysis. 2nd ed. New York: Routledge.

- Walby, S. 2005. “Gender Mainstreaming: Productive Tensions in Theory and Practice.” Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State & Society 12 (3): 321–343. doi:10.1093/sp/jxi018.

- Wittman, A. 2010. “Looking Local, Finding Global: Paradoxes of Gender Mainstreaming in the Scottish Executive.” Review of International Studies 36 (1): 51–76. doi:10.1017/S0260210509990507.

- Wong, F., A. Vos, R. Pyburn, and J. Newton. 2019. “Implementing Gender Transformative Approaches in Agriculture.” https://www.kit.nl/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Gender-Transformative-Approaches-in-Agriculture_Platform-Discussion-Paper-final-1.pdf.

- World Bank, FAO, and IFAD. 2015. “Gender in Climate-Smart Agriculture.” https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/22983/Gender0in0clim0riculture0sourcebook.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

- Zimmermann, L. 2014. “Same Same or Different? Norm Diffusion between Resistance, Compliance, and Localization in Post-Conflict States.” International Studies Perspectives 17 (1): 98–115. doi:10.1111/insp.12080.