Abstract

Although stabilisation has been widely debated by the recent literature, there has been relatively little discussion about how the governments of countries affected by armed violence have themselves engaged with the concept. This article looks at Colombia where, since the election of president Iván Duque in 2018, the government has increasingly emphasised stabilisation. We argue that stabilisation is for the Duque administration a discursive device that allows them to navigate the contradiction between their critical position towards the peace process and the necessity to fulfil internal and international obligations. We also argue that, in spite of its apparent novelty, the concept of stabilisation has long roots in Colombia, going back to the policies of consolidation developed under the presidencies of Álvaro Uribe and Juan Manuel Santos. The analysis of the antecedents of consolidation raises doubts about the appropriateness of Duque’s stabilisation for tackling Colombia’s post-conflict challenges. The case of Colombia highlights the risk that stabilisation might displace more transformative approaches to peacebuilding and the continuity between contemporary stabilisation and previous interventions.

Introduction

During the last decade, international peacebuilding has evolved from ambitious transformative agendas to pragmatic missions with narrower mandates and reduced expectations (Belloni and Moro Citation2019). In this context, the rise of stabilisation, a concept developed in the framework of Western counter-insurgency (COIN) doctrine, has attracted increasing attention. The relatively recent adoption of stabilisation by the United Nations (UN), in particular, has led to concerns that stabilisation is displacing or compromising better approaches to build peace in post-conflict countries. Critics of stabilisation argue that the rebranding of post-conflict interventions as stabilisation is leading to an increasing focus on security at the expense of broader peacebuilding needs and a reduced commitment to support peace negotiations (Karlsrud Citation2019; Belloni and Moro Citation2019; Curran and Holtom Citation2015; Gilder Citation2019; Mac Ginty Citation2012). However, while numerous scholarly publications investigate stabilisation in the context of UN peace operations and European and North American post-conflict interventions, there has been little discussion until now – with some exceptions (Harig Citation2019; Muggah Citation2013) – about how post-conflict countries affected by political and criminal violence have themselves engaged with the discourse and practices of stabilisation and, in some cases, even contributed to their development. Consequently, the implications of the embracement of stabilisation for these countries have also not been analysed in depth. Moreover, much of the recent literature emphasises the novelty of stabilisation (Curran and Holtom Citation2015; Belloni and Moro Citation2019; Gilder Citation2019; Karlsrud Citation2019; Howard and Stark Citation2018), neglecting its historical continuity with a long tradition of COIN and ‘pacification’ (Barakat, Deely, and Zyck Citation2010),

This article analyses the rise of stabilisation in Colombia, where, since the election of conservative President Iván Duque (a critic of the 2016 peace agreement) in 2018, the government has introduced a new political discourse emphasising stabilisation (estabilización in Spanish) (Llorente, Garzón, and Bernal Citation2018). The recent rise of stabilisation in Colombia has been somewhat surprising, because it contradicted to some extent the approach to peacebuilding taken by the Final Agreement for Ending the Conflict and Building a Stable and Lasting Peace (Republic of Colombia Citation2016).Footnote1 Inspired by liberal and participative values, the agreement chartered an ambitious agenda of transformation, envisaging deep structural changes in Colombian society (Cairo et al. Citation2018; Rettberg Citation2020).

Analysing the Colombian government’s turn to stabilisation can help us to understand why governments of conflict-affected countries choose to embrace the concept and whether the argument that the ‘turn to stabilisation’ might have negative implications on peacebuilding is justified. It can also shed light on the extent to which stabilisation policies are a relatively recent introduction, prompted by the popularity of the concept at the international level, and the extent to which they represent a return to policies that these countries implemented in the past.

The article proceeds as follows. The first section looks at the rise of international stabilisation in the last decade and at the academic debate on stabilisation. Subsequently, we look at the emergence of stabilisation in Colombia and analyse how the presidency of Iván Duque understands the concept of stabilisation. We argue that Duque’s embracement of stabilisation can be explained in reference to short-term political concerns, notably Duque’s need to find a public discourse that would allow him to partially and selectively implement the peace agreement while satisfying international obligations. The turn to stabilisation is, however, also part of Colombia’s longer history of policies aiming to integrate alleged ‘ungoverned areas’ of the country into the Colombian state. In particular, Duque’s stabilisation presents substantial affinities and continuities with the policies of ‘consolidation’ implemented by the Colombian government under the presidencies of Álvaro Uribe and Juan Manuel Santos. We question whether Duque’s stabilisation really represents a ‘return to the past’, and we analyse the implications of the Colombian experience for the stabilisation debate. We conclude by showing how this approach has contributed to undermining the peacebuilding process.

We base our analysis on a systematic review of policy documents produced by the Colombian administration since the first Uribe election (2002–) and on about 20 interviews conducted in the summer of 2019 in Bogotá with past and current civil servants, politicians and academics. Two additional interviews with policymakers based in Bogotá were also conducted remotely at the beginning of 2021. We interviewed members of both the current Duque administration and the past Santos administration involved in stabilisation policies and in the negotiation and implementation of the peace agreement. We also interviewed officers of think tanks, embassies and aid agencies that have contributed to shaping Colombian stabilisation policies. As part of a broader project on territorial peacebuilding in Colombia, we also conducted in the same period 12 focus groups with social leaders from rural communities in the Cauca region, and 11 individual interviews with members of regional and local branches of government agencies in the Cauca. Although this material does not directly feed into this article, it has contributed to our broader understanding of the political and security situation in post-conflict Colombia.

Reconstructing war-torn states: from liberal peacebuilding to ‘stabilisation’?

During the past decade there has been growing disillusionment regarding ambitious post-conflict interventions conducted under the framework of liberal peacebuilding or COIN (Howard and Stark Citation2018; Belloni and Moro Citation2019). At the same time, the appetite of Western countries for large-scale operations has been fading, while new concerns, such as the growth of terrorism and the increase in refugee flows, have risen (Belloni and Moro Citation2019; Mac Ginty Citation2012).

It is in this context that the concepts of ‘stability’ and ‘stabilisation’ are enjoying an increasing popularity when it comes to supporting countries emerging from conflicts (Belloni and Moro Citation2019; Muggah Citation2013; Curran and Holtom Citation2015). The term stabilisation started to appear in debates about governance and intervention around the mid-1990s, but the labels ‘stability operations’ or ‘stability and reconstruction operations’ became commonly used by North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) countries only after 11 September 2001 (Mac Ginty Citation2012; Howard and Stark Citation2018). Towards the end of the 2000 decade, a number of Western security agencies formalised their stabilisation doctrines (United States Citation2008; United Kingdom Citation2008).

In the last decade, two trends can be observed. The first is the adoption of stabilisation beyond Western military and security agencies, particularly by the UN, which has led to growing claims that stabilisation has become the ‘new normal’ (de Coning Citation2018). To date, the UN have used the term ‘stabilisation’ as part of the name of four peace operations, all – with the exception of the United Nations Stabilization Mission in Haiti (MINUSTAH; 2004) – launched after 2010 (Gilder Citation2019; Karlsrud Citation2019; Curran and Holtom Citation2015). Two studies have found an increasing use of the term ‘stabilisation’ within open UN Security Council meetings between 2000 and 2014 (Curran and Holtom Citation2015) and in annual reports produced by the Security Council to the General Assembly between 2001 and 2013 (Howard and Stark Citation2018, 166). Scholars have also argued that stabilisation’s growing popularity fits within geopolitical trends characterised by the rise of non-Western powers and the decline of US hegemony (Howard and Stark Citation2018, 141).

The second trend is an increasing concern that the adoption of stabilisation might have a detrimental effect on peace, and might be displacing more promising ways to address conflicts. In his seminal 2012 contribution, Roger Mac Ginty argues that ‘stabilization – as a concept and practice – lowers the horizons of peace and peace interventions’ (Mac Ginty Citation2012, 26) and that ‘the concept of stabilization further normalizes the role of the military and aligned security agencies into peacebuilding’ (Mac Ginty Citation2012, 27). Other authors have expressed similar concerns. They have argued that stabilisation might produce more instability in the long term (Belloni and Moro Citation2019) and that it might lead to disregard for the promotion of democracy and human rights (Howard and Stark Citation2018). Peacekeeping scholars also fear that stabilisation might compromise the key principles of UN peacekeeping (Karlsrud Citation2019; Gilder Citation2019), particularly the UN capacity to contribute to inclusive and transformative peacebuilding (Curran and Hunt Citation2020).

Overall, it is difficult to point to exactly what a stabilisation approach entails and how it differs from peacebuilding (Belloni and Moro Citation2019, 446). The term does not refer to a set of specific policies. Various forms of post-conflict intervention, such as disarmament, demobilisation and reintegration (DDR), the promotion of the rule of law, or the implementation of quick-impact projects (QIPs) are often listed as components of both stabilisation and peacebuilding interventions (United States Institute for Peace and US Army Peacekeeping and Stability Operations Institute Citation2009; Curran and Hunt Citation2020).

Most official definitions of stabilisation are vague and refer to the goals that stabilisation is supposed to accomplish and to the type of environment in which stabilisation missions or activities are carried out (Muggah Citation2013; Gilder Citation2019; Curran and Holtom Citation2015). The US Stability operations doctrine defines stabilisation as ‘the process by which military and nonmilitary actors collectively apply various instruments of national power to address drivers of conflict, foster Host Nation (HN) resiliencies, and create conditions that enable sustainable peace and security’ (United States Citation2016, I-1). The UK Stabilisation unit defines stabilisation as ‘an initial response to violence or the immediate threat of violence’ (United Kingdom Citation2019a, 11) and argues that the UK’s objective is ‘to reduce violence, ensure basic security and facilitate peaceful political deal-making’ (United Kingdom Citation2019a, 11). In their comprehensive analysis of Western stabilisation policies and discourses, Belloni and Moro (Citation2019) identify several recurrent attributes of contemporary stabilisation and attempt to individuate the characteristics that set aside stabilisation from peacebuilding. First, stabilisation entails a preoccupation for security which contrasts with the emphasis of peacebuilding, even in its ‘institutions first’ variant, on the quality of governance and importance of democratic values (Belloni and Moro Citation2019, 447; Paris Citation2004). Stabilisation emphasises the containment of armed groups as ‘spoilers’ of stability, often by military means, and prioritises the delivery of basic services over governance reforms (Belloni and Moro Citation2019, 452). Second, ‘stabilization tends to be focused on quick-impact projects while peacebuilding operations aspire to set the foundations for and develop a new social contract among the population’ (Belloni and Moro Citation2019, 451).

Another important feature sets stabilisation aside from peacebuilding. Peacebuilding implicitly or explicitly presupposes the attainment of a certain level of stability through the conclusion of a negotiated settlement in which all warring parties participate (United Nations Citation2008; Karlsrud Citation2015). Although some variants of the doctrine, for instance the UK stabilisation approach, include a commitment to promote peacemaking (United Kingdom Citation2019a), the concept of stabilisation has been invoked in a broader variety of situations where an inclusive peace settlement is considered unachievable or undesirable. For instance, stabilisation has been applied to countries like Haiti and Brazil, affected by high rates of criminal violence (Muggah Citation2013), and UN stabilisation missions in the DRC and Mali have involved controversial mandates that authorise them to use force to ‘“neutralize” and “disarm” groups that pose a threat to “state authority and civilian security”’ (Karlsrud Citation2015, 40–41). Thus, stabilisation often entails both designating an enemy and supporting and strengthening authorities considered legitimate, usually state authorities (Karlsrud Citation2015; Gilder Citation2019; Curran and Holtom Citation2015).

The state-centric character of stabilisation also has another implication: because of its pragmatic approach, stabilisation brings closer on the one hand Western practices and discourses of post-conflict intervention, and on the other efforts to ensure stability carried out by national governments of states affected by armed violence. Some countries and regional organisations in the Global South (for instance, Brazil and the African Union) have explicitly adopted stabilisation, while also reinterpreting and readapting it, others have developed policies inspired by stabilisation, but avoided using the term (ie Mexico), and still others have crafted the rhetoric of stabilisation on existing domestic COIN policies (Pakistan and Sri Lanka) (Muggah Citation2013; Dersso Citation2016; Harig Citation2019). In spite of this wide range of cases, there are comparatively few studies about how national governments beyond NATO countries adopt, appropriate or contribute to the development of stabilisation doctrines and how this approach shapes peacebuilding outcomes.

When it comes to Latin American countries, their understanding of stabilisation has been described as close to Western doctrines and less focussed on military force than that of Asian countries (Muggah Citation2013, 243). However, in spite of these countries’ stated commitment to an integrated approach and to use stabilisation to improve the well-being of vulnerable populations, existing research offers evidence supporting the views of those who fear that stabilisation might lead to excessive securitisation. Christoph Harig, for instance, has shown how Brazilian participation in UN stabilisation and the subsequent adoption of stabilisation at home has encouraged the internal deployment of the army for law-and-order purposes (Harig Citation2019). In investigating the Mexico–US partnership to tackle Mexican drug cartels, Sebastián Albuja argues that, in spite of the inclusive stabilisation approach promised, it has ended up focussing in practice on military action (Albuja Citation2013, 178).

The emphasis of the current stabilisation literature on the UN’s embracement of stabilisation tends also to overshadow the fact that contemporary stabilisation draws from a long history of technologies of intervention, previously labelled ‘counter-insurgency (COIN), pacification, stabilisation, peace-support operations or reconstruction’ (Barakat, Deely, and Zyck Citation2010, S298). Studies of stabilisation efforts led by governments of the Global South can help to better understand how the label is attached to practices that draw from past experiences and long-term influences. In the context of Brazil, the combination of use of force and developmental projects ‘can be traced back to French colonial COIN tactics coupled with policing innovations developed in the US and other contemporary security policies’ (Schuberth Citation2019, 491), while in Mexico the legacy of long-term US involvement stands out (Albuja Citation2013).

This article aims to contribute to refocussing the study of stabilisation on its implementation by governments of the so-called Global South and to scrutinising its long-term dimension. Differently from the case studies most often invoked in the literature, Colombia has not experienced the deployment of an international stabilisation operation. Hence, Colombia’s stabilisation policies have been designed and implemented by the Colombian government itself, although international influences have played a role. Colombia is also different from other Latin American countries, which have experienced organised crime but not a long-term armed conflict with a political dimension.

The analysis of the Colombian case contributes to broader debates on stabilisation in three ways. First, the embracement of stabilisation by the Colombian government provides evidence to sustain the claim that stabilisation is becoming a default approach to tackle armed violence and sheds light on why national governments might embrace the concept. Given Colombia’s history of peace negotiations, this case also helps us to investigate the relationship between peacebuilding and stabilisation, and the claim that stabilisation is displacing peacebuilding. Third, given Colombia’s long history of conflict and instability, our case study contributes to the debate on change and continuity between current stabilisation and past policies that displayed a similar approach.

In the following section, we look at how the discourse of stabilisation has emerged in Colombia under the Duque presidency and at how the Duque government understands stabilisation in its official discourse.

Colombian stabilisation under the administration of Iván Duque: peace with legality?

The recent rise of a discourse of stabilisation in Colombia should be understood in the context of the opposition of conservative Colombian actors to the 2016 peace agreement between the Colombian government and the Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia – Ejército del Pueblo (FARC-EP, Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia – People’s Army), which attempted to solve a conflict that had lasted about half a century (Bermúdez Liévano Citation2018). The conclusion of the agreement spurred unanimous support and triumphant optimism at the international level (United Nations Citation2016), which culminated in the award of the Nobel Peace Prize to then Colombian president Juan Manuel Santos.

The agreement was widely praised for what was seen as its progressive approach (Mendes, Siman, and Fernández Citation2020, 4). In particular, through the discourse of ‘territorial peace’ (Jaramillo Caro Citation2014) Sergio Jaramillo, long-time collaborator of president Santos and High Commissioner for Peace between 2012 and 2016, portrayed the agreement as an effort to build the state ‘from below’ in conflict-affected areas of the country, with the participation of local communities (Jaramillo Caro Citation2014). A key instrument that Jaramillo envisaged for promoting territorial peace were the Programas de Desarrollo con Enfoque Territorial (PDET, Development Programmes with a Territorial Focus), which the 2016 peace agreement described as a participative planning instrument targeting selected rural areas affected by the conflict (Republic of Colombia Citation2016, par. 1.2).

The support that the agreement enjoyed at the international level and among the Colombian intellectual elite was, however, not unanimously shared across the Colombian society. Former president Álvaro Uribe, still a very popular political figure in Colombia, increasingly accused Santos of conceding too much to FARC, crafting a series of simplistic but effective slogans that dismissed the peace agreement as ‘peace with impunity’ (Dávalos et al. Citation2018). When the Santos government called for a plebiscite on the agreement in October 2016, Uribe and his Centro Democrático (CD, Democratic Centre) party campaigned for a No vote and were eventually successful when 50.2% of voters rejected the agreement. In response to the outcome of the referendum, the Colombian government and FARC renegotiated some controversial aspects of the agreement, eventually managing to achieve ratification from the Colombian Congress (Rettberg Citation2020). However, the outcome of the peace referendum left a bitter taste and compromised the perception that the agreement had popular legitimacy.

In 2018, when Santos’ second term came to an end, the Colombian peace process had made uneven advances. The disarmament of FARC combatants was well underway, while the PDET process was still beginning and rural reforms were lagging behind (Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies Citation2019). The Programa Nacional Integral de Sustitución de Cultivos de Uso Ilícito (PNIS, National Programme of Illicit Crop Substitution), which should have helped Colombian peasants to switch from coca and marijuana cultivation to legal crops, was also in a state of disarray. Duque, the CD presidential candidate, was among the politicians who had endorsed the No campaign in 2016. He had spent most of his career in the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) and was little known in Colombia before 2018. Duque ‘campaigned almost entirely on his uribista credentials’ (Gamboa Citation2018, 56), presenting himself as a ‘conservative, free-market, technocratic candidate’ (Gamboa Citation2018, 56). Thanks also to the spectre of the Venezuelan crisis, which he used to demonise the left-wing opposition, Duque managed to get elected in the second round with 53.98% of the vote, becoming the new Colombian president.

Since being elected, Duque’s attitude towards the peace process has, however, been ambiguous. On the one hand, particularly at the international level, the government has repeatedly declared that the Colombian government is going to comply with the engagements taken by the Santos administration. On the other hand, encouraged by Uribe, the CD party continues to question the legitimacy of the 2016 peace agreement and to hint that the agreement constitutes a ‘government policy’ that was only binding for the Santos administration (Seguimiento multi-partidista a la implementación del Acuerdo de Paz Citation2019). It is in this context that we should situate the increasing use of the concept of stabilisation by the Duque administration (Llorente, Garzón, and Bernal Citation2018), which has gone hand in hand with the rebranding of the notion of peace as ‘peace with legality’. In the fall of 2018, the Duque administration published two documents meant to shape its approach to the implementation to the peace process, the ‘stabilisation policy’ ‘Paz con Legalidad’, or ‘Peace with Legality’Footnote2 (Republic of Colombia Citation2018a) and ‘La Paz, la Estabilización y Consolidación son de Todos’ (‘Peace, Stabilisation and Consolidation Are for All’, Republic of Colombia Citation2018b), a more operationally oriented document. The term ‘stabilisation’ recurs about 30 times in the first document and 45 times in the second.

Following the adoption of ‘Peace with Legality’, Duque also renamed the Consejería Presidencial para el Post-conflicto (Office of the Presidential Advisor for Post-conflict Affairs), one of the key actors in charge of the peacebuilding process, to Consejería para la Estabilización y Consolidación (Office of the Presidential Advisor for Stabilisation and Consolidation), and nominated Emilio Archila at its head.

In spite of the ubiquity of stabilisation in the Duque administration’s official discourse, there is no definition of stabilisation in government documents, and neither Duque nor Archila – nor any other member of the current Colombian government – has ever articulated stabilisation as a ‘philosophy’ for post-conflict Colombia in a manner comparable to Jaramillo’s idea of territorial peace. ‘Peace, Stabilisation and Consolidation Are for All’ lists a series of agendas that correspond to key points of the 2016 peace agreements – comprehensive rural reform, territorial planning, security and the DDR of former combatants – as its ‘stabilisation policy’ (Republic of Colombia Citation2018b). It is thus unclear from this document whether stabilisation represents a distinctive approach, and how it differs from the one delineated by the agreement.

The connection between Duque’s discourse and the international discourse on stabilisation can, however, be unpacked by looking at how ‘Peace with Legality’, ‘Peace, Stabilisation and Consolidation Are for All’, the Security and Defence Policy (Política de Defensa y Seguridad, PDS) and other government documents discuss the concepts of legality, security and institutionalisation.

The focus on security is a crucial component of stabilisation at the international level and is also a key focus of Duque’s policy. When publicly presenting the PDS, President Duque stated that ‘this government believes in security as a vehicle for the construction of peace in Colombia’ (Semana Citation2019). Duque’s conception of security reconnects with ideas of stabilisation at the international level in two respects. First, the absence or ‘failure’ of the state is seen as the main cause of insecurity in the country: in his words ‘the main threat for internal security is [the existence of] empty institutional spaces and the precariousness of institutions’ (Republic of Colombia Citation2019, 5). Second, although the military continues to play an important role in Duque’s approach to stabilisation (Republic of Colombia Citation2019, 9), in line with international understandings of stabilisation, the Duque administration argues that stabilisation should be a multi-agency endeavour implemented with ‘the strategic accompaniment of public, private entities, and civil society organizations’ (Republic of Colombia Citation2019, 35).

Concerning national and general security policies, Duque recognises that new forms of insecurity are emerging in Colombia after 2016, in particular with the increasing attacks against social leaders, human rights defenders and peasants involved in crop substitution processes (Republic of Colombia Citation2018b, Citation2018b, 37). However, the ‘return of the state’ is portrayed somewhat unproblematically as the solution to all security challenges. The 2019 PDS proposes a spatialised, three-phase intervention, in order to avoid the return of illegal groups to the territories once occupied by FARC. The first phase involves interventions of military unit forces and the police in a series of areas particularly affected by violence and instability (Republic of Colombia Citation2019, 38). In February 2021, five areas, named Zonas Futuro, had been placed in this category (Republic of Colombia, Citationn.d.). The second phase involves a transition from military control to institutional control (Republic of Colombia Citation2019, 38). In this phase the police will have a more salient role due to its civil nature, and the presence of the state will be ensured through the effective administration of justice, education and health (Republic of Colombia Citation2019, 38–39). In the third phase, threats to security arise from common crime and will be secured by the National Police (Republic of Colombia Citation2019, 39).

The Duque administration also considers addressing the issue of illicit drugs a key component for achieving security (Republic of Colombia Citation2018b), yet even here there are ambiguities in its approach. ‘Peace, Stabilisation and Consolidation Are for All’ argues that the Santos administration was inefficient and wasteful in implementing the PNIS (Republic of Colombia Citation2018b, 19–20). However, it retains the overall voluntary approach to the eradication of illicit crops of the peace agreement. Yet, in the same period, the Duque administration announced the re-introduction of glyphosate spraying, a practice that is controversial in Colombia because of its effects on health and the environment, and whose use was restricted by a sentence of the Constitutional Court in 2017 (El Espectador Citation2018).

Conceptually close to the Duque administration’s interpretation of insecurity as absence of the state is the president’s emphasis on legality. The creation of a ‘culture of legality’ is seen as fundamental to ensure security (Republic of Colombia Citation2019, 6). In the preface to the Plan Nacional de Desarrollo (PND, National Development Plan), Duque insists repeatedly on the importance of legality as ‘an ethical and moral principle that will allow us to overcome the challenges that we face today’ (Republic of Colombia Citation2018c, 6). While advocates of liberal peacebuilding have often considered the rule of law a prerequisite for democracy and liberalisation, they see it as something that is absent or flawed in post-conflict countries (Paris Citation2004). In Duque’s vision of stabilisation, on the other hand, legality is seen as a quality that the state supposedly already possesses. The lack of state governance within what are referred to as ‘the territories’, not the nature of the state, is assumed to be responsible for the reoccurrence of violence. This represents a rupture with ideas of liberal peacebuilding but is in line with the approach taken by more recent international stabilisation operations.

Duque’s emphasis on the rule of law has also gone hand in hand with denying the relevance and autonomy of the Jurisdicción Especial de Paz (Special Jurisdiction of Peace, JEP), the transitional justice mechanism created by the peace negotiations. The administration’s proposal of controversial modifications to the JEP (Republic of Colombia Citation2018b, 25), which were eventually rejected by the Constitutional Court of Colombia, have paradoxically been seen in Colombia as destabilising the peacebuilding process (Restrepo Parra Citation2019).

It should be noticed, however, that the Duque administration does not completely break with the rhetoric of the 2016 Peace agreement. ‘Peace, Stabilisation and Consolidation Are for All’ reframes several of the key objectives of the Peace Agreement as stabilisation and ‘Peace with Legality’ assert that the government is committed to implement the PDETs (Republic of Colombia Citation2018a, 10). Anticipating the potential criticism that the prioritisation of the Zonas Futuro might clash with the prioritisation established by the peace agreement through the PDET process, the government has repeatedly stated that ‘the plans will not result in the suspension of the PDET, but will coordinate with them, where there might be an overlap’ (Republic of Colombia Citation2018c).

In other respects, however, ‘Peace with Legality’ shows the abandonment of transformative expectations that analysts associate with international stabilisation. This is evident regarding integral rural reform, one of the key transformational components of the peace agreement. Duque’s stabilisation plan moves away from the already moderate and non-redistributive land policies of the 2016 peace agreement (Gutiérrez Sanín Citation2019). Overall, the integral rural reform (which is point 1 of the final peace agreement) is reduced to two instrumental actions: cadastral measuring and land formalisation (Republic of Colombia Citation2018a, 9). The rejection of progressive land reforms is also linked to the Duque administration’s preference for a neo-liberal model, where the emphasis is on how to incentivise private investments in the PDET areas. ‘Peace, Stabilisation and Consolidation Are for All’ states that the private sector has an interest in reducing violence in formerly conflict-affected territories and thus has to be closely associated with the stabilisation efforts (Republic of Colombia Citation2018b).

Stabilisation as political opportunism

Why is the Colombian government embracing the discourse of stabilisation? We argue that there are two ways to look at Duque’s stabilisation. First, it can be seen as a rhetorical choice responding to a series of short-term, pragmatic concerns, masking the lack of an actual viable political vision for post-conflict in Colombia. Second, beyond its political instrumentalisation, Duque’s stabilisation can also be understood as being in continuity with a series of previous Colombian policies – in particular the so-called policy of consolidation, which started during the second Uribe mandate.

Interviews conducted in Bogotá stress the lack of clarity that surrounds the turn to stabilisation. Not only is a clear definition of stabilisation lacking in official documents, but members of the Duque administration tend to be elusive when questioned about their understanding of stabilisation. For instance, when asked for his definition of stabilisation, a top-ranking public official replied defensively that the concept was ‘not mine’.Footnote3 For him, stabilisation and consolidation

are the theory of what happens in the aftermath of extreme situations such as natural disasters, armed conflicts or mass violence. There is a lot of literature on it. The phase of stabilisation means that we are identifying the circumstances that led to this situation and that we are adopting the actions that are required in order to address the institutional and social causes.Footnote4

Several other civil servants working for the current administration insisted that the shift from territorial peace to stabilisation in the public discourse has no practical meaning.Footnote5 For instance, an employee of the Consejería para la Estabilización y Consolidación argued that ‘if they had not changed the name, I think we would be doing the same job’.Footnote6 Another civil servant told us that all governments like to change names and that it makes little difference ‘whether it is called post-conflict or whether it is called stabilisation’.Footnote7

For a policy analyst, stabilisation is attractive to the Duque administration because it is in line with its narrow problem-solving approach to the implementation of the peace process:

There is a transition from ‘liberal peacebuilding’ to stabilisation. Clearly, Archila’s pragmatic ideas go against the initial idea of grassroots participation …. What the Duque government wants is to be able to come back to the public with a list of implemented projects.Footnote8

Some interviewees lamented that ‘they [the government] themselves do not know very well what it [stabilisation] means …’Footnote9 and wondered ‘whether there is a strategic coherence about where they want to go by employing this narrative’.Footnote10

Seen in the political context of post-2018 Colombia, stabilisation can be seen as a rhetorical tool that allows the Duque administration to find a way out of a contradiction: on the one hand, the necessity to align with the discourse of uribista’s hardliners and, on the other, the need to implement at least some components of the Peace Agreement. The government also needs to please international partners and donors by showing some commitment to peace. It is important to consider that, under Uribe’s two terms in office, the Colombian government insisted not only that FARC and other leftist insurgent groups were ‘terrorists’ (Republic of Colombia Citation2003, 5–6), but also that one could not speak about the existence of an armed conflict in Colombia. Following the uribista’s line of reasoning, ‘armed conflicts’ could only take place in authoritarian countries that denied the right of the opposition to peacefully organise, not in a country like Colombia, which they represented as a fully fledged democracy (Restrepo Citation2015).

The Duque administration thus finds itself in the paradoxical situation of having to implement a peace agreement, which is supposed to put an end to an armed conflict, while it simultaneously denies the very existence of the conflict. According to a former civil servant, ‘the government wanted to distance itself from the discourse and the narrative of the peace agreement, while at the same time having a narrative that allows them to implement the agreement’.Footnote11 For another interviewee, who has been involved in policy debates about stabilisation on behalf of an international partner of Colombia, the Duque government could not use ‘peace’ (except with the qualification ‘with legality’) or ‘consolidation’ (a word previously used to designate interventions to tackle armed violence in Colombia), because both concepts are too closely associated with the Santos administration in the public memory.Footnote12 So, they had to search for a ‘new branding’: ‘I think that they asked Google and got “stabilisation”’.Footnote13 Close ties with the US, as well as the existence of a US stabilisation policy towards Venezuela, also played a role: ‘our main ally uses stabilisation, so we use it as well’.Footnote14 The discourse of stabilisation also facilitates communication with other Western partners, who have employed the concept to frame their policies towards Colombia (United Kingdom Citation2019b; Government of Canada Citation2017).

Seen in this light, the discourse of stabilisation becomes a device to escape the contradictions that the Duque administration is facing. At the same time, however, beyond its short-term instrumentalisation, Duque’s stabilisation can also be seen as a return to a long history of policies aiming to restore state authority in conflict-affected areas. This is what we look at in the next section.

Stabilisation as a return to the past?

The precedent of consolidation

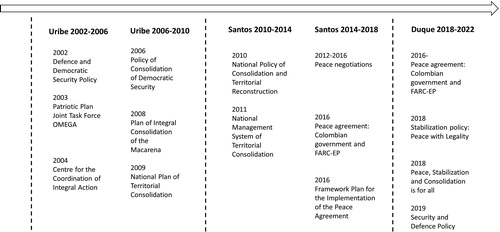

Although the word ‘stabilisation’ has been systematically used in Colombia only since Duque’s election, there are clear similarities between past Colombian policies implemented between the early 2000s and the start of the peace negotiations and international stabilisation. Some observers identify elements of stabilisation in COIN policies implemented in Colombia in the 1960s with US support (Elhawary Citation2010). However, the most direct antecedents are the so-called consolidation policies implemented by the Colombian government under the Uribe and Santos administrations in order to restore security and extend the authority of the Colombian state (). These policies display the fundamental features of contemporary international stabilisation, such as the focus on security and statebuilding and the insistence on an integrated, multi-agency approach.

Figure 1. Timeline of consolidation/stabilisation policies and the peace process in Colombia from the Uribe administration to the Duque administration. Compiled by the authors using Colombian government documents.

Under the first Uribe presidency, the Colombian government’s approach to security and statebuilding could be characterised as ‘classic’ COIN, although some elements of stabilisation were already present. The Uribe administration’s flagship policy, launched in 2003, the Política de Defensa y Seguridad Democrática (PSD, Defence and Democratic Security Policy), focussed on undermining the power of FARC and other illegal armed groups (Republic of Colombia Citation2003).

Although the focus of the Uribe administration was on military action, the PSD recognised that this was insufficient for achieving security, and that coordination between civic and military agencies to holistically confront internal threats was required (Republic of Colombia Citation2003, 7, 16). In 2004, with the encouragement of the US government (Steele and Shapiro Citation2012), the government created the Centro de Coordinación de Acción Integral (CCAI, Centre for the Coordination of Integral Action). The CCAI had the objective of strengthening the presence and legitimacy of democratic institutions in regions where they had been weak. However, its deployment was slow: the CCAI established a regional presence in Colombia’s conflict-affected areas only in 2006 (Mejía, Uribe, and Ibáñez Citation2011).

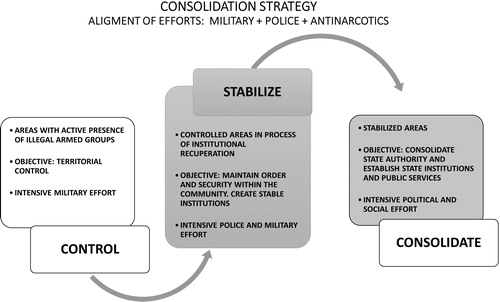

The integral approach was reinforced under Uribe’s second term (2006–2010), when the Ministry of Defence created the Política de Consolidación de la Seguridad Democrática (PCSD, Policy of Consolidation of Democratic Security) (Republic of Colombia Citation2007). The main architects of consolidation were Uribe’s future adversaries: Santos, who was at the time Minister of Defence, and his then Vice Minister for policies and international affairs, Jaramillo. The official aims of consolidation were to promote security, the return of the institutional control of the state in the territory, the comprehensive presence of state institutions, the strengthening of local governance, the effective participation of civil society, the eradication of illicit crops, the protection of the environment and the effective administration of justice (Republic of Colombia Citation2007). The PCSD introduced the idea of a three-phased intervention adapted to the security situation in the area: the regions targeted for intervention were classified into green, yellow and red zones (Republic of Colombia Citation2007).

With support from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), the Ministry of Defence launched in 2008 a pilot application of the new approach, the Plan de Consolidación Integral de la Macarena (PCIM, Plan of Integral Consolidation of the Macarena) in the Sierra of the Macarena, located to the south-east of Bogotá (Republic of Colombia Citation2008; Mejía, Uribe, and Ibáñez Citation2011). A central innovation of the plan was its participatory aspect: the development projects implemented in the yellow and green areas were chosen through consultations with the communities, who were invited to set their priorities.

In 2009, consolidation was expanded to another 10 areas and in 2010, Santos, elected president, rebranded consolidation as Política Nacional de Consolidación y Reconstrucción Territorial (PNCRT, National Policy of Consolidation and Territorial Reconstruction) (Republic of Colombia Citation2011) and further extended it to 51 areas clustered within 12 departments (Steele and Shapiro Citation2012). The PNCRT, following the example of the PCIM, aimed to involve the communities in development and statebuilding activities. The programme organised meetings with community members and encouraged citizens to respect the law and stop growing illicit crops in exchange for ‘rapid response’ assistance (Steele and Shapiro Citation2012, 6).

Already at the time, some observers, such as Colombian think tank Fundación Ideas para la Paz (FIP, Foundation Ideas for Peace), argued that consolidation was the Colombian version of international stabilisation. For FIP, the main differences between Colombian consolidation and international ‘stabilization operations’ were the ‘vocation of permanence’ of Colombia’s consolidation (Palou et al. Citation2011, 14) and the lack of ‘intervention of a third party in the internal affairs of a country in a fragile situation, because it is an initiative of the national government to solve one of its own main problems’ (Palou et al. Citation2011, 14).

If we look at the policy documents produced as part of ‘consolidation’, however, we see that the term ‘stabilisation’ was occasionally used, but in an unclear and inconsistent way. The PCSD described stabilisation as the set of actions to be implemented in the yellow areas, following the phase of territorial control (control de área) in the red areas and preceding the phase of consolidation in the green areas () (Republic of Colombia 2007).

Figure 2. The phases of consolidation according to the Política de Consolidación de la Seguridad Democrática (graphic representation of the authors, from Republic of Colombia Citation2007).

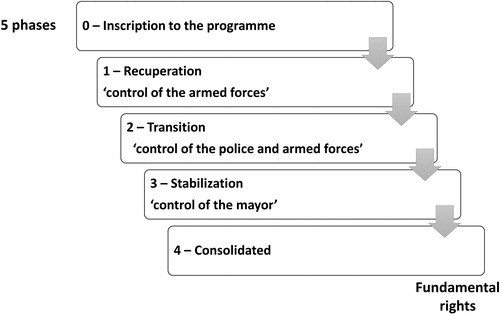

The PCIM changed terminology, talking instead of military operations, transition and consolidation in, respectively, the red, yellow and green zones (Republic of Colombia Citation2008). Confusingly, stabilisation reappeared in subsequent PNCT and PNCRT programme documents produced by the CCAI (Mejía, Uribe, and Ibáñez Citation2011) and in the 2014 PNCRT guidelines (Republic of Colombia Citation2014), this time to designate not the second but now the third phase of consolidation ().

Figure 3. The phases of consolidation according to the Política Nacional de Consolidación y Reconstrucción Territorial (graphic representation of the authors, from Republic of Colombia Citation2014).

In particular, in the 2014 PNCRT, stabilisation is achieved when ‘solid foundations for institutional development, supported by administrative and fiscal capacities and the provision of public services, exist’ (Republic of Colombia Citation2014, 34). The analysis thus confirms the malleable character of the discourse of stabilisation, which can be used alternatively for designating security focussed interventions involving the use of military force, and civilian institution-building and development activities.

Overall, the balance sheet of consolidation under Uribe and Santos is mixed (Elhawary Citation2010). According to Álvaro Balcázar, who directed the PCIM and was the first director of the PNCT, once the programme was expanded, its decentralised and participative component tended to fade away: ‘We gave too much power to the centre, and the idea that we could “bring the state to the territories” creeped back in …. In the end, the PNCRT degenerated into a programme that could only execute small projects’.Footnote15

The disillusionment with consolidation contributed to the decision of the Santos administration to initiate peace talks with the FARC in November 2012 in ‘a tacit recognition by the government that … the most cost-effective strategy is to cut a deal with the insurgency … rather than to compete as service providers’ (Delgado Citation2015, 410).

Lessons not learned?

Duque’s current policy of stabilisation has significant affinities with the policies of consolidation launched under the second Uribe administration and under the Santos presidency, which in turn echo the international understanding of stabilisation. The focus on the expansion of state authority and the three-phased character of civil–military intervention are a feature of Colombian consolidation and stabilisation in all their variants. The fundamental architecture of the consolidation/stabilisation plans has not fundamentally changed. Duque’s attempt to reinitiate the forced eradication of illicit crops is also indicative of the attempt to return to the uribista era, which was characterised by a tough ‘war on drugs’ approach. As an embassy officer explained to us, the Duque administration is driven by ‘“agents of nostalgia”; the nostalgia of Uribe, the first Uribe, the Uribe of 2002, of Democratic Security’.Footnote16

However, with respect to the previous consolidation policies, and even more to those of the early Uribe presidency, Duque’s stabilisation takes place in a radically changed political and security environment. Although rural Colombia is still affected by multiple forms of violence, the principal threat to the state, constituted by a highly organised and well-armed guerrilla movement, is not there anymore. For the Colombian government, consolidation was to some extent a constrained choice before 2016, since no negotiated framework existed. After 2016, the peace agreement has provided a roadmap to address the long-term causes of the armed conflict.

In this sense, Duque seems to be going back to consolidation without learning the lessons that its architects drew. In reviewing the balance sheet of consolidation, Jaramillo and other policymakers were aware of the importance of ‘minimizing the role of the military’, ‘improving land policy’ and ‘developing sustainable projects and livelihoods’ (Poe and Isacson Citation2011, 4). Duque’s stabilisation represents a step backward on territorial peacebuilding (Palou Citation2019), as he seeks to restore the uribista security framework and its political appeal for many conservative sectors. It has little to say about land policy and again puts the military at the centre of the strategy (Palou Citation2019). By using stabilisation and ‘peace with legality’ as a framework to selectively implement the peace agreement, while voiding it from its most transformative components, the government risks losing sight of its long-term objectives and turning it into a series of small projects, as was the case in the past with consolidation.

While the abandonment of transformative ambitions is perhaps unsurprising considering Duque’s past opposition to the peace process, at the beginning of 2021 Duque’s stabilisation does not appear very successful even in achieving its declared objective – the establishment of basic security and the redeployment of state services. Since the demobilisation of FARC, Colombia is facing new modalities of violence targeting FARC ex-combatants and social leaders (Seguimiento multi-partidista a la implementación del Acuerdo de Paz Citation2019). Official government statistics put the number of social leaders assassinated in 2020 at 173, 29.1% more than in 2019 (Seguimiento multi-partidista a la implementación del Acuerdo de Paz Citation2021, 8), with human rights NGOs reporting even higher figures. The government portrays the creation of the Zonas Futuro as a way to respond to new security concerns, addressing the presence of illegal armed groups in former FARC-controlled zones. However, the response seems to be based on the same type of high-profile military operations that were previously employed against the FARC, with little reflection about whether this model is adapted to the new security situation (Seguimiento multi-partidista a la implementación del Acuerdo de Paz Citation2019). At the moment, the intervention of the Colombian state in the Zonas Futuro is limited to the establishment of a military presence (United Nations Citation2020, 3). In spite of Duque’s emphasis on legality, ‘the presence of judges, prosecutors and judicial police continues to be insufficient’ (Seguimiento multi-partidista a la implementación del Acuerdo de Paz Citation2019, 12), and there is no sign that the state is truly ‘coming back’ in an integral manner, nor is it able to protect social leaders.

Conclusion

The rise of stabilisation in the international context has been widely debated in the recent literature, yet we still do not know much about how the concept is contributing to shape discourse and policy beyond the UN and NATO countries. We have shown in this article how, since the election of Iván Duque in 2018, the Colombian government has developed a strategic narrative and a set of security practices that evoke the concept of stabilisation. Duque’s understanding of stabilisation presents numerous affinities with stabilisation as understood by Western military circles, the UN and other Latin American countries: it is a multi-agency endeavour that focuses on the neutralisation of potential spoilers and the expansion of state authority through the national territory.

What has made stabilisation attractive in the particular case of Colombia? In the short term, Duque’s stabilisation allows the new administration to define its own political identity and navigate the contradiction between the party’s critical position towards the peace process on the one hand and the necessity to implement at least some aspects of the Peace Agreement and fulfil international obligations on the other. Although the Duque administration represents its approach as a new strategy (Palou Citation2019), Duque’s stabilisation displays numerous affinities not only with the policies of his mentor Uribe, but also with the consolidation policies designed and implemented under the Santos presidency. Duque has imported the international rhetoric of stabilisation but has integrated it within domestic historical experiences. However, in doing so, he has ignored that, in the eyes of its own creators, consolidation proved insufficient to meet its challenges and was in the end abandoned in favour of a different framework.

The Colombian case reinforces existing concerns that the diffusion of stabilisation is displacing more ambitious transformative approaches to tackle instability and is leading to a downscaling of ambitions and a focus on security. Under the banner of stabilisation, the Colombian government is increasingly downplaying the importance of rural reform and grassroots participation. Regarding security, there are signs that the embracement of stabilisation might open the door for militarisation and discourage creative thinking.

The continuity between Colombia’s previous policies of consolidation and post-2018 stabilisation confirms Barakat, Deely and Zyck’s insight that ‘the perceived novelty of contemporary post-crisis stabilisation operations is in many respects rooted in a “tradition of forgetting”’ (Barakat, Deely, and Zyck Citation2010, S298) and exemplifies ‘the cyclical resurrection of previously problematic paradigms’, which ‘may be viewed as a failure of institutional learning’ (Barakat, Deely, and Zyck Citation2010, S298). The example of Colombia suggests, however, that these failures occur for a reason: some actors benefit from them. In particular, for the Duque administration, the stabilisation discourse has become a strategy of legitimation and a way to appease its political constituency.

Acknowledgements

This article is part of the ESRC-Colciencias-funded project ‘Territorial planning for peace and state-building in the Alto Cauca region of Colombia’. We thank Katherine Gough and Irene Vélez-Torres for their leadership of the project and their support of our research. We also extend our gratitude to our partner research team at Universidad del Valle, who shared with us their invaluable knowledge of the Alto Cauca region, in particular James Iván Larrea and Bladimir Bueno. We also thank Angelika Rettberg and Lina Malagón-Brett, who shared with us contacts and insights useful for our fieldwork in Bogotá. Jorge Delgado and Alejandra Ortiz-Ajala read earlier versions of this paper and provided comments and suggestions. Sofia Pérez helped with interview transcriptions and Daniel Faulkner assisted with proofreading. Finally, we thank all the interviewees who kindly shared their views with us, and the anonymous referees of Third World Quarterly, who helped us to improve the article with their suggestions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Funding

This work was supported by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) UK and Colciencias (Colombia) [under grant number ES/R010749/1].

ORCID

Giulia Piccolino: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6817-6542.

Krisna Ruette-Orihuela: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2562-9249.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Giulia Piccolino

Giulia Piccolino is Senior Lecturer in politics and international relations at Loughborough University. She is currently involved in the ESRC-funded project ‘Territorial Planning for Peace and State-Building in the Alto Cauca region of Colombia’ and in a project on the consequences of rebel governance in Côte d’Ivoire. She is also interested in exploring non-liberal forms of conflict management and post-conflict reconstruction. She has published widely in peer-reviewed journals, including African Affairs, Development and Change, Third World Quarterly and Democratization.

Krisna Ruette-Orihuela

Krisna Ruette-Orihuela is Lecturer in social justice at University College Dublin (UCD). Before joining UCD, she was Postdoctoral Research Associate in geography and environment at Loughborough University in the research project ‘Territorial Planning for Peace and State-Building in the Alto Cauca region of Colombia’. She is currently interested in exploring how territorial peace instruments are negotiated and contested by different ethno-racial groups and political actors. Her research has focussed on the intersections of anti-racism, social movements, social justice, state multiculturalism and peacebuilding.

Notes

1 For the purpose of this article, we reference the English translation of the Colombian peace agreement published by the Colombian government.

2 The Colombian presidency published an English version of the document, titled in Spanish Paz con Legalidad. We are quoting here this official English translation. Quotes from other Colombian government documents have been translated from Spanish by the authors of this article.

3 Interview with top government advisor, Bogotá, 28 August 2019.

4 Interview with top government advisor, Bogotá, 28 August 2019.

5 Interview with civil servant, Bogotá, 22 August 2019; Interview with civil servant, 23 August 2019, Bogotá; Interview with civil servant, online, 5 February 2021.

6 Interview with civil servant, Bogotá, 22 August 2019.

7 Interview with civil servant, 23 August 2019, Bogotá.

8 Interview with policy researchers, Bogotá, 26 July 2019.

9 Interview with policy researcher, Bogotá, 29 August 2019.

10 Interview with former civil servant, Bogotá, 26 August 2019.

11 Interview with former civil servant, Bogotá, 26 August 2019.

12 Interview with policy advisor at Western embassy in Bogotá, online, 8 January 2021.

13 Interview with policy advisor at Western embassy in Bogotá, online, 8 January 2021.

14 Interview with policy advisor at Western embassy in Bogotá, online, 8 January 2021.

15 Interview with Álvaro Balcázar Vanegas, 26 August 2019, Bogotá; Interview with former civil servant, 26 August 2019, Bogotá; Interview with former civil servant, 26 August 2019, Bogotá; Interview with policy researchers, Bogotá, 26 July 2019.

16 Interview with policy advisor at Western embassy in Bogotá, online, 8 January 2021.

Bibliography

- Albuja, Sebastián. 2013. “Stabilization Next Door: Mexico’s US-Backed Security Intervention.” In Stabilization Operations, Security and Development, edited by Robert Muggah, 179–193. London: Routledge.

- Barakat, Sultan, Sean Deely, and Steven A. Zyck. 2010. “‘A Tradition of Forgetting’: Stabilisation and Humanitarian Action in Historical Perspective.” Disasters 34: S297–S319. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7717.2010.01207.x.

- Belloni, Roberto, and Francesco N. Moro. 2019. “Stability and Stability Operations: Definitions, Drivers, Approaches.” Ethnopolitics 18 (5): 445–461. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17449057.2019.1640503.

- Bermúdez Liévano, Andrés. 2018. Los debates de La Habana: una mirada desde adentro. Barcelona: Institute for Integrated Transitions (IFIT) and Fondo de Capital Humano para la Transición Colombiana.

- Cairo, Heriberto, Ulrich Oslender, Carlo Emilio Piazzini Suárez, Jerónimo Ríos, Sara Koopman, Vladimir Montoya Arango, Flavio Bladimir Rodríguez Muñoz, et al. 2018. “‘Territorial Peace’: The Emergence of a Concept in Colombia’s Peace Negotiations.” Geopolitics 23 (2): 464–488. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2018.1425110.

- Curran, David, and Paul Holtom. 2015. “Resonating, Rejecting, Reinterpreting: Mapping the Stabilization Discourse in the United Nations Security Council.” Stability: International Journal of Security and Development 4 (1): 2000–2014. doi:https://doi.org/10.5334/sta.gm.

- Curran, David, and Charles T. Hunt. 2020. “Stabilization at the Expense of Peacebuilding in UN Peacekeeping Operations: More than Just a Phase?” Global Governance: A Review of Multilateralism and International Organizations 26 (1): 46–68. doi:https://doi.org/10.1163/19426720-02601001.

- Dávalos, Eleonora, Leonardo Fabio Morales, Jennifer S. Holmes, and Liliana M. Dávalos. 2018. “Opposition Support and the Experience of Violence Explain Colombian Peace Referendum Results.” Journal of Politics in Latin America 10 (2): 99–122. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1866802X1801000204.

- de Coning, Cedric. 2018. “Is Stabilization the New Normal? Implications of Stabilization Mandates for the Use of Force in UN Peacekeeping Operations.” In The Use of Force in UN Peacekeeping, edited by Peter Nadin, 105–119. London: Routledge.

- Delgado, Jorge E. 2015. “Counterinsurgency and the Limits of State-Building: An Analysis of Colombia’s Policy of Territorial Consolidation, 2006–2012.” Small Wars & Insurgencies 26 (3): 408–428. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09592318.2014.982881.

- Dersso, Solomon. 2016. “Stabilization Missions and Mandates in African Peace Operations: Implications for the ASF.” In The Future of African Peace Operations, edited by Cedric De Coning, Linnéa Gelot, and John Karlsrud, 38–51. London: Zed Books.

- Elhawary, Samir. 2010. “Security for Whom? Stabilisation and Civilian Protection in Colombia.” Disasters 34 (s3): S388–S405. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7717.2010.01211.x.

- El Espectador. 2018. “Iván Duque retomaría aspersiones con glifosato.” September 12. https://www.elespectador.com/noticias/politica/ivan-duque-retomaria-aspersiones-con-glifosato/.

- Gamboa, Laura. 2018. “Latin America’s Shifting Politics: The Peace Process and Colombia’s Elections.” Journal of Democracy 29 (4): 54–64. doi:https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2018.0062.

- Gilder, Alexander. 2019. “The Effect of ‘Stabilization’ in the Mandates and Practice of UN Peace Operations.” Netherlands International Law Review 66 (1): 47–73. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s40802-019-00128-4.

- Government of Canada. 2017. “By the Numbers: Canada’s Support for Peace Implementation in Colombia”. Embassy of Canada to Colombia. https://www.canadainternational.gc.ca/colombia-colombie/index_paz.aspx?lang=eng.

- Gutiérrez Sanín, Francisco. 2019. “The Politics of Peace: Competing Agendas in the Colombian Agrarian Agreement and Implementation.” Peacebuilding 7 (3): 314–328. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/21647259.2019.1621247.

- Harig, Christoph. 2019. “Re-Importing the ‘Robust Turn’ in UN Peacekeeping: Internal Public Security Missions of Brazil’s Military.” International Peacekeeping 26 (2): 137–164. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13533312.2018.1554442.

- Howard, Lise Morjé, and Alexandra Stark. 2018. “How Civil Wars End: The International System, Norms, and the Role of External Actors.” International Security 42 (3): 127–171. doi:https://doi.org/10.1162/ISEC_a_00305.

- Jaramillo Caro, Sergio. 2014. “La paz territorial”. Republic of Colombia, Oficina del Alto Comisionado para la Paz. Based on a presentation delivered on 13 March 2014 at Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA. https://interaktive-demokratie.org/files/downloads/La-Paz-Territorial.pdf.

- Karlsrud, John. 2015. “The UN at War: Examining the Consequences of Peace-Enforcement Mandates for the UN Peacekeeping Operations in the CAR, the DRC and Mali.” Third World Quarterly 36 (1): 40–54. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2015.976016.

- Karlsrud, John. 2019. “From Liberal Peacebuilding to Stabilization and Counterterrorism.” International Peacekeeping 26 (1): 1–21. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13533312.2018.1502040.

- Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies. 2019. “Estado efectivo de implementación del Acuerdo de Paz de Colombia 2 años de implementación: Informe 3 diciembre 2016 - Diciembre 2018.” https://kroc.nd.edu/news-events/news/tercer-informe-sobre-la-implementacion-del-acuerdo-de-paz-la-implementacion-sigue-progresando/

- Llorente, María Victoria, Juan Carlos Garzón, and José Luis Bernal. 2018. La Estabilización en la fase de transición: ¿Cómo responder a la situación de crisis y fragilidad estatal?, Fundación Ideas para la Paz (FIP), Notas Estratégicas 6, Bogotá, October 2018. http://www.ideaspaz.org/publications/posts/1706.

- Mac Ginty, Roger. 2012. “Against Stabilization.” Stability: International Journal of Security and Development 1 (1): 20. doi:https://doi.org/10.5334/sta.ab.

- Mejía, Daniel, María José Uribe, and Ana María Ibáñez. 2011. Una evaluación del Plan de Consolidación Integral de la Macarena (PCIM). No. 008740. Universidad de los Andes-CEDE. https://repositorio.uniandes.edu.co/handle/1992/8245.

- Mendes, Isa, Maíra Siman, and Marta Fernández. 2020. “The Colombian Peace Negotiations and the Invisibility of the ‘No’ Vote in the 2016 Referendum.” Peacebuilding 8 (3): 321–343. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/21647259.2019.1620908.

- Muggah, Robert, ed. 2013. Stabilization Operations, Security and Development: States of Fragility. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Palou, Juan Carlos. 2019. “La paz en la política de defensa y seguridad de Duque.” Razón Publica, March 18. https://razonpublica.com/la-paz-en-la-politica-de-defensa-y-seguridad-de-duque/.

- Palou, Juan Carlos, Gerson Arias, Carol Barajas, Miguel Ortega, Juan Pablo Liévano and Carlos Otálora. 2011. Balance de la Política Nacional de Consolidación Territorial. FIP, Informe 14, Bogotá, September 2011. http://ideaspaz.org/media/website/consolidacionweb.pdf.

- Paris, Roland. 2004. At War’s End: Building Peace after Civil Conflict. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Poe, Abigail, and Adam Isacson. 2011. “Stabilization and Development: Lessons of Colombia’s ‘Consolidation ’Model.” Center for International Policy. https://www.usip.org/programs/stabilization-and-development-lessons-colombias-consolidation-model.

- Republic of Colombia. n.d. “Zonas Futuro: Zonas Estratégicas de intervención Integral.” Presidential advisor for communication. https://id.presidencia.gov.co/Documents/190808-Infografia-Zonas-Futuro.pdf.

- Republic of Colombia. 2003. “Política de Defensa y Seguridad Democrática.” Presidency of the Republic. https://www.oas.org/csh/spanish/documentos/colombia.pdf.

- Republic of Colombia. 2007. “Política de Consolidación de la Seguridad Democrática.” Ministry of National Defence. Accessed 13 April 2020. http://pdba.georgetown.edu/Security/citizensecurity/Colombia/politicas/consolidacion.pdf.

- Republic of Colombia. 2008. “Plan de Consolidación Integral de la Macarena.” Presidency of the Republic. August. http://ccai-colombia.org/files/primarydocs/0808pcim.pdf.

- Republic of Colombia. 2014. “Lineamientos de la Política Nacional de Consolidación y Reconstrucción Territorial (PNCRT).” Unidad Administrativa para la Consolidación Territorial.

- Republic of Colombia. 2011. “Decreto 4161 de 2011 por el cual se crea la Unidad Administrativa Especial para la Consolidación Territorial y se determinan sus objetivos, estructura y funciones.” Diario Oficial 48242. 3 (November 2011): 78.

- Republic of Colombia. 2016. “Final Agreement to End the Armed Conflict and Build a Stable and Lasting Peace.” Government of Colombia and Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia—Ejército del Pueblo (FARC–EP). November 24. https://www.cancilleria.gov.co/sites/default/files/Fotos2016/12.11_1.2016nuevoacuerdofinal.pdf.

- Republic of Colombia. 2018a. “Peace with Legality.” Iván Duque Marquez, President of the Republic of Colombia. http://www.posconflicto.gov.co/Documents/Peace-with-legality-Policy-2019.pdf.

- Republic of Colombia. 2018b. “La Paz, la Estabilización y Consolidación Son de Todos: Política de Iván Duque, Presidente de la República, Para la Estabilización 2018-2022.” Presidency of Colombia, October.

- Republic of Colombia. 2018b. “Plan Nacional de Desarrollo 2018-2022: Pacto por Colombia, pacto por la equidad.” Departamento Nacional de Planeación. https://www.dnp.gov.co/DNPN/Paginas/Plan-Nacional-de-Desarrollo.aspx.

- Republic of Colombia. 2018c. “Ley 1941”. Presidency of Colombia, December 18. http://es.presidencia.gov.co/normativa/normativa/LEY%201941%20DEL%2018%20DE%20DICIEMBRE%20DE%202018.pdf.

- Republic of Colombia. 2019. “Política de Defensa y Seguridad PDS para la Legalidad, el Emprendimiento y la Equidad.” Ministry of National Defence. https://www.mindefensa.gov.co/irj/go/km/docs/Mindefensa/Documentos/descargas/Prensa/Documentos/politica_defensa_deguridad2019.pdf.

- Restrepo, Luis Carlos. 2015. “¿Conflicto armado o amenaza terrorista?”. Semana 1192, March 6. https://www.semana.com/nacion/articulo/conflicto-armado-amenaza-terrorista/71229-3.

- Restrepo Parra, Adrián. 2019. “El Gobierno Desestabilizador Del Acuerdo.” Revista Debates (81): 26–33.

- Rettberg, Angelika. 2020. “Peace-Making Amidst an Unfinished Social Contract: The Case of Colombia.” Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding 14 (1): 84–100. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17502977.2019.1619655.

- Schuberth, Moritz. 2019. “Brazilian Peacekeeping? Counterinsurgency and Police Reform in Port-Au-Prince and Rio De Janeiro.” International Peacekeeping 26 (4): 487–510. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13533312.2019.1623675.

- Seguimiento multi-partidista a la implementación del Acuerdo de Paz. 2019. “¿En que va el Acuerdo de Paz a un Ano del Gobierno Duque? Retos y recomendaciones. Informe 1.” Parliament of Colombia and USIP. https://www.juanitaenelcongreso.com/post/en-que-va-el-acuerdo-de-paz-a-un-a%C3%B1o-del-gobierno-duque.

- Seguimiento multi-partidista a la implementación del Acuerdo de Paz. 2021. “¿En qué va la Paz? Las cifras de la implementación. Reporte 6.” Parliament of Colombia and USIP. https://www.juanitaenelcongreso.com/post/sexto-informe-de-seguimiento-a-la-implementacion-del-acuerdo-de-paz.

- Semana. 2019. “‘La seguridad no se puede confundir con guerra’: Iván Duque.” February 6. https://www.semana.com/nacion/articulo/ivan-duque-lanza-en-tolemaida-su-plan-de-seguridad-y-defensa/600302.

- Steele, Abbey, and Jacob N. Shapiro. 2012. “State-Building, Counterinsurgency, and Development in Colombia.” Unpublished paper, Princeton University, August 3.

- United Kingdom. 2008. “The UK Approach to Stabilisation: Stabilisation Unit Guidance Note.” Stabilisation Unit. https://gsdrc.org/document-library/the-uk-approach-to-stabilisation-stabilisation-unit-guidance-notes/.

- United Kingdom. 2019a. “The UK Government’s Approach to Stabilisation: A Guide for Policy Makers and Practitioners.” Stabilization Unit, March 7. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-uk-governments-approach-to-stabilisation-a-guide-for-policy-makers-and-practitioners.

- United Kingdom. 2019b. “UK Programme Funds in Colombia.” Colombia, United Kingdom Embassy. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/uk-programme-funds-in-colombia.

- United Nations. 2008. United Nations Peacekeeping Operations: Principles and Guidelines. New York: United Nations Department of Peacekeeping Operations/Department of Field Support. http://pbpu.unlb.org/pbps/Library/Capstone_Doctrine_ENG.pdf.

- United Nations. 2016. “As Colombians Bid Farewell to ‘Decades of Flames,’ Ban Pledges UN Support to Historic Peace Deal.” September 26. https://news.un.org/en/story/2016/09/541072-colombians-bid-farewell-decades-flames-ban-pledges-un-support-historic-peace#.WJYrnvnhCUk.

- United Nations. 2020. “Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights on the Situation of Human Rights in Colombia, A/HRC/43/3/Add.3.” United Nations Human Rights Council, 26 February.

- United States. 2008. “Field Manual 3-07: Stability Operations.” Headquarters Department of the Army. https://www.hsdl.org/?abstract&did=234741.

- United States. 2016. “Joint Publication 3-07: Stability.” Joint Chiefs of Staff. https://www.jcs.mil/Portals/36/Documents/Doctrine/pubs/jp3_07.pdf.

- United States Institute for Peace and US Army Peacekeeping and Stability Operations Institute. 2009. “Guiding Principles for Stabilization and Reconstruction.” US Institute for Peace, Washington. https://www.usip.org/publications/2009/11/guiding-principles-stabilization-and-reconstruction.