Abstract

While an extensive part of the conflict transformation literature stresses the importance of transforming the identities of conflict parties through recognition, it fails to recognise the propensity of such transformations to generate ontological insecurity and dissonance, and consequently a possible backlash towards antagonistic identities. Drawing on agonistic thought, we develop a conception of agonistic recognition, premised on non-finalism, pluralist multilogue and disaggregated recognition. We suggest that these elements of agonistic recognition may guard against the development of ontological insecurity and dissonance in recognition processes. We comparatively analyse the connections and tensions between recognition, ontological insecurity/dissonance and identity backlash experienced during the transformation of the Israeli–Palestinian conflict in the context of the Oslo Peace Process in the 1990s and Turkey’s ‘rapprochement’ with Greece in the context of its EU accession process in the 2000s. We also assess the presence of the elements of agonistic recognition in these two conflict transformation processes. Our contribution constitutes an important step towards the specification of agonistic peace in terms of its underlying recognition processes and in developing the empirical study of agonistic elements in actual conflict transformation processes.

Introduction

During the last few years, distinct literatures have developed in peace studies exploring how the concepts and processes of recognition, identity change and ontological security intersect with peace processes (Buckley-Zistel Citation2008; Northrup Citation1989; Rumelili Citation2015; Rumelili and Todd Citation2018; Strömbom Citation2014, Citation2020). These literatures have developed along different tracks, pointing to various requirements for as well as challenges to the sustainable transformation of protracted conflicts. When these theories are juxtaposed, an exigent paradox becomes visible – that the very prerequisites for sustainable conflict transformation, recognition and, in turn, identity change tend to trigger ontological insecurity, which threatens to generate backlash towards antagonistic identities. Our contribution pinpoints drivers for identity backlash and suggests pathways for avoiding such dynamics, by developing and fine-tuning arguments from the literature on agonistic peace. We advance the burgeoning literature at the intersection of the fields of ontological security and conflict transformation (Rumelili Citation2015; Lupovici Citation2015) by forging further links to the fields of recognition and agonistic peace (Lehti and Romashov Citation2021; Rumelili and Çelik Citation2017). Additionally, our contribution constitutes an important step towards the specification of agonistic peace in terms of its constituent elements and processes as well as its consequences for conflict transformation. Specifically, we propose and develop, as an underlying process of agonistic peace, the notion of agonistic recognition. We posit agonistic recognition as a facilitating condition for sustainable conflict transformation on the basis of our theorisation that it precludes the creation of ontological insecurity and dissonance which in turn curb the propensity for identity backlash.

In this article, we specify the connections and tensions between recognition, ontological (in)security, and identity backlash against the empirical backdrop of Turkish and Israeli experiences of conflict transformation in the past few decades. During the transformation of the Israeli–Palestinian conflict in the context of the Oslo Peace Process in the 1990s and Turkey’s ‘rapprochement’ with Greece, Armenia and its Kurdish minority in the context of its EU accession process in the 2000s, new narratives on recognition of the Other (Ram Citation2003; Strömbom Citation2013) were introduced in both countries. We find similar dynamics at play in Israel and Turkey regarding how new narratives of recognition triggered ontological insecurity and dissonance and drove a backlash towards antagonistic identities.

We begin with an elaboration on the relationship among recognition, ontological (in)security and identity backlash in theoretical terms. Building on a narrative conception of identity, we draw attention to the fact that narratives of recognition of the Other introduced in peace processes potentially trigger ontological insecurity and dissonance by challenging key aspects of self-narratives of conflict parties. Ontological insecurity and dissonance, in turn, may drive identity backlash in the form of a return towards established antagonistic identity narratives. We then discuss how agonistic recognition, which we conceptualise as having the three main elements of non-finalism, pluralist multilogue and disaggregation, may allow for the preservation of ontological security. Then follows a discussion of the characteristics of the recognition processes as they unfolded in Israel and Turkey. We analyse how the absence, to various degrees, of pluralistic multilogue and disaggregation in the recognition processes may account for the substantial identity backlashes as experienced in both countries. In conclusion, we sum up our findings and point out that further development is needed in terms of micro-dynamics of agonistic peace and its relations to recognition, and to our empirical as well as theoretical findings which have revealed an important avenue for research in that direction.

Recognition, ontological (in)security and identity backlash

An extensive part of the conflict transformation literature focuses on the importance as well as the hardships of transforming identities in conflicts (Galtung Citation1996; Kriesberg Citation1998; Northrup Citation1989). This literature acknowledges that identities are inherently fluid and context-dependent, yet underline that long-standing conflict tends to make identities of parties more stable and dyadically opposed (Strömbom Citation2014). Consequently, conflict over time accumulates a self-perpetuating logic, where antithetically constructed identities render it almost impossible to negotiate competing claims over territory, rights or collective governance. Consequently, most conflict resolution proposals and frameworks seek to promote greater recognition between conflict parties, in the form of ‘acknowledgement, understanding, or empathy for the situation and the views of the other’ (Bush and Folger Citation2005, 22).

Drawing upon Honneth’s (Citation1995) category of recognition premised on self-esteem (Strömbom Citation2014), it has been stressed that recognition should encompass the acceptance of individual differences and respect for the features that make a subject unique (Allan and Keller Citation2006; Wendt Citation2003). Scholars have associated this thick type of recognition with active promotion of public awareness of the Other’s identity narratives, histories and legitimation claims (Strömbom Citation2014). This awareness is expected to trigger a critical process of self-transformation where past assumptions about the Self and its role in the conflict are questioned and re-evaluated (Buckley-Zistel Citation2008). It could also reduce self-monopolisation of feelings of victimhood and generate the realisation that all groups in conflict have had their own experiences of suffering (Bar-Tal Citation2000). This type of narrative change, if broadly accepted in society, may lead to identity transformation and more constructive relations among former antagonists.

In this article, we adopt a narrative approach, which stresses that recognition and identity change are mediated by changes in narratives on Self and Other (Somers Citation1994). We define collective self-narratives as structures of meaning forged over time, which situate the collectivity in time and distinguish it from significant Others (Somers Citation1994). Three aspects of the narrative approach are critical. First, reality cannot be ascertained independently from and outside of narrative (Labov Citation2006). Second, collective self-narratives provide a sense of ontological security, moral purpose and positive distinctiveness to the members of a collectivity (Rumelili Citation2015). And, third, narratives on Self and Other are mutually constitutive and intertwined, and hence neither can change independently of the other (Connolly Citation1991).

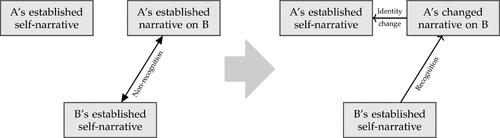

depicts how recognition and identity change, within a narrative approach, are generally expected to develop in the existing literature on conflict transformation. Recognition entails the introduction of new representations to the narratives of the Other which better correspond with the Other’s self-narratives. Accordingly, A’s recognition of B unfolds as B’s self-narratives become better reflected in A’s changed narratives on B. Consequently, because narratives on Self and Other are mutually constitutive and intertwined, recognition may also result in an identity change in A. As depicted in the figure, identity change comes about as changes in A’s narrative on B forges the formation of a changed self-narrative in A.

What has not been fully considered in the existing literature on conflict transformation through recognition is the tendency of individuals and groups to derive a sense of ontological security from the stability and routinisation of their self-narratives. This is also the case for conflict narratives and for the antagonistic identities produced through the conflict (Mitzen Citation2006; Rumelili Citation2015). These narratives not only define the positions of actors in specific conflicts, but also, over time, they come to constitute ‘a formed framework’ for existence. As Giddens has argued, having such ‘a formed framework’ is essential for ontological security, because it allows actors to bracket certain existential questions about themselves, others and the object world, questions in need of clear answers in order to be able to cope with everyday activities (Citation1991). The mutually exclusive and uncontested friend/enemy distinctions produced in conflict serve as focal points for stable constructions of Self and Other (Rumelili and Todd Citation2018). The routines of non-recognition or misrecognition between conflict parties (cf. Gustafsson Citation2016) provide a moral certainty to each that they are wronged by an ill-willed adversary.

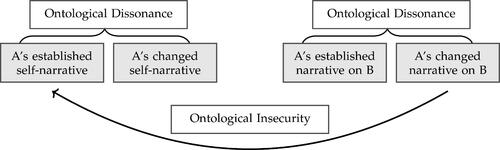

Recognition thus potentially functions as a double-edged sword in conflict transformation. On the one hand, parties changing their narratives of the Other to better correspond with the Other’s self-narratives enable sustainable conflict transformation, as it allows for a mutual understanding of the Other’s positions and demands. On the other hand, recognition, especially when pursued in a ‘totalistic’ manner, disrupts the continuity and stability of self-narratives and the ideological and moral certainty provided by the conflict’s ‘formed framework’. As depicted in , when such disruption of established narratives of Self reaches significant levels, it may induce a state of anxiety, panic, uncertainty and ontological insecurity (Connolly Citation1995; Rumelili Citation2015). Additionally, the incongruence between the new, more positive representations of the Other and the established negative representations may generate ‘ontological dissonance’ (Lupovici Citation2012, 810). Actors seeking to avoid ontological insecurity and dissonance find comfort in a return to even more fortified self-narratives and increased distancing to difference. Thus, ontological insecurity and dissonance consequently may drive an identity backlash, meaning a mobilisation of resistance to changes in self-narratives (Alter and Zurn Citation2020), in a way that thwarts the goals of recognition.

The next section further theorises the defining attributes of agonistic recognition and discusses the ways in which these attributes guard against the materialisation of identity backlash. It should be noted that we are positing neither that the nature of the recognition process is the sole determinant of identity backlash, nor that identity backlash is going to have an immediate and determinative effect on peace processes. Our subsequent empirical analyses of the Israeli–Palestinian and the Greek–Turkish conflicts indeed amply demonstrate that the intensity of identity backlashes and their effects on the ongoing peace processes are likely to vary according to external as well as conflict-specific factors.

Agonism and recognition

The concept of agonistic peace, originally coined by Rosemary Shinko (Citation2008), puts forward an alternative vision of peace marked by the peaceful and pluralistic coexistence of multiple, contesting narratives. What has justified this normative vision is the growing realisation that dominant narratives, symbols and rituals of parties in intractable conflicts often prove resistant to conflict transformation, continue to compete for dominance, and retain their capacity for expediting antagonistic conflict even after peace agreements (Nagle Citation2014). In a growing literature, it has been argued that building an agonistic peace requires the challenging of the liberal association of peace with consensus (Peterson Citation2013; Schaap Citation2005) and the acceptance of the complex and open-ended nature of conflicts (Maddison Citation2015). To realise an agonistic peace, scholars have noted the importance of creating institutional frameworks agreed upon by all parties (Strömbom Citation2020) at the elite and preferably also at the grassroots level, which provide outlets for articulations of difference and dissent both within and between the parties (Peterson Citation2013; Shinko Citation2008) and facilitate encounters based on mutual respect and regulated by democratic norms and procedures (Aggestam, Cristiano, and Strömbom Citation2015).

The notion of agonistic peace stems from a rich body of agonistic theory emanating from political philosophers like Chantal Mouffe (Citation2005, Citation2013) and William Connolly (Citation1991), which conceives of conflict as inherent to the human condition and ascribes a positive value to it (Wenman Citation2013). While appealing, the notion of agonistic peace remains under-specified in terms of both substance and its underlying processes. In this article, without aiming at a comprehensive, grand theory of agonistic peace, we focus on elucidating agonistic recognition as one of its underlying processes. Building on key tenets of agonistic thought, we identify below non-finalism, pluralist multilogue and disaggregation as three key aspects of agonistic recognition, and discuss how these aspects may guard against the materialisation of identity backlashes along the pathways discussed above.

Three elements of agonistic recognition

The disavowal of teleology is a key aspect of agonistic thought. Politics is interminable and not orientated towards some higher form or grand vision of reconciliation. As James Tully, a key thinker of agonistic recognition, has indicated, recognition is also not intended to culminate in a comprehensive ‘end state’, understood as the ‘form of mutual recognition [that] all those concerned demand’ (Tully Citation1999, 175 cited in Wenman Citation2013, 146). As noted in previous scholarship on agonistic peace, agonistic recognition does not strive towards consensus on one finalised identity or one shared grand narrative about the conflict (Mälksoo Citation2015). According to this non-finalist aspect, recognition need not culminate in full respect for all aspects of the other’s identity, apology for past actions or an institutionalised future relationship of equality. In fact, agonistic thought considers total recognition to be constitutively impossible, since identities are continuously re-constituted in unpredictable ways through politics. At the core of this open-ended process of agonistic recognition is the willingness to relinquish what we once cognised as truths and the cognitive and emotional openness to come to know again (Rose Citation1995; Schick Citation2015). ‘Re-cognising’ the Other is not sought as the immediate objective but could emerge as a by-product of emotional and cognitive openness. The process of recognition is therefore ‘self- rather than other-directed’, and first and foremost entails overcoming the desire for the full recognition on part of Self (Markell Citation2003, 38 cited in Wenman Citation2013, 148).

The non-finalism of agonistic recognition guards against the development of ontological insecurity, and a reactionary return to non-recognition arising from unfulfilled expectations. The actors conceive of themselves and others as continuously re-cognising, and their narratives on Self and Other as continuously changing; therefore, they come to accept that a perfect correspondence between narratives is unattainable and bound to be temporary.

A second tenet of agonistic recognition is pluralist multilogue. An ineradicable constituent feature of the political in agonistic thought, pluralism is not limited to the existing variety in the conceptions of good among existing subjects but is a principle that is constitutive of the very identities of groups and individuals (Mouffe Citation2005). An agonistic peace, therefore, does not aim at the suppression of the pluralism in conflict societies in the name of peace, but rather encourages the active recognition of the multiplicity of narratives on Self as well as the Other (Aggestam, Cristiano, and Strömbom Citation2015; Maddison Citation2015). Here, it is crucial to note that requirements of agonistic pluralism vary greatly across conflict contexts. In intrastate conflicts and settings with strong majority/minority dynamics such as Turkish–Kurdish relations or intrasocietal relations among Israeli Jews and Israel’s Palestinian minority, an agonistic pluralism would be expected to go beyond a thin liberal approach of simply allowing for multiplicity; rather, it would entail challenges to prevailing recognition forms (Tully Citation2000, 470; Wenman Citation2003, 167). In interstate peace processes, such as in Greek–Turkish relations or between Israel and Palestine in the context of a two-state solution, pluralism mainly will refer to the inclusion of varying degrees of moderates and hardliners in intra-societal exchanges of views about the conflict and its resolution.

Having recognised the multiplicity of identity narratives in Self and Other as part of pluralist recognition, multilogue entails continuous dialogue among actors subscribing to these multiple narratives (Owen Citation2012). Recognition struggles are not binary. Instead of dialogue being confined to groups committed to the peace process, or limited to dominant identity narratives, a pluralist multilogue encompasses exchanges between subscribers to different narratives within each conflict society and across conflict lines. Governed by the norm of ‘audi alteram partem’ (always listening to the other side) (Tully Citation2004), a multilogue drives recognition of Self as well as the Other in all its diversity.

Such pluralist multilogue is likely to guard against identity backlash. Within conflict societies, it moderates the ontological dissonance between established and changed narratives about Self by leaving room for dialogue between actors subscribing to these sets of narratives. Pluralism also prevents the polarisation between established and changed narratives, and the emergence of in-group/out-group dynamics between actors subscribing to these narratives. The inclusion of hardliner and more radical positions in the dialogue weakens their potential efficacy as outsider spoilers. It also prevents misperceptions regarding the broader spectrum of narratives in the other collectives involved in conflict. Whereas recognition processes that are solely centred on recognising the Other in terms of its dominant identity narrative overlook the ongoing – and yet to emerge – contestations over identity in conflict societies, pluralist recognition cannot be unsettled easily by specific statements or actions taken by the Other, as it is already premised on the recognition of the Other as a diverse and shifting actor.

Thirdly, agonistic recognition is disaggregated. This aspect is rooted in the close association of agonistic thought with post-structuralist conceptions of identity as always defined through difference (cf. Connolly Citation1991). Accordingly, rather than aspiring to a totalistic recognition of the Other’s identity narratives, which would dissolve the Self/Other distinction, agonistic thought disaggregates difference from opposition and antagonism, and calls for a reconstruction of the Self/Other relationship from one of hostile antagonism into constructive rivalry. While there is no clear guidance in agonistic thought on how narratives on Self and Other can be reconstructed to disaggregate difference from antagonism, we build on the international relations literature, which has drawn attention to variation in Self/Other relations along temporal, spatial and or ethical boundaries (Hansen Citation2006; Rumelili Citation2004). In antagonistic narratives, these boundaries overlap; Self ascribes a temporally fixed identity to Other; it represents Self and Other to be mutually exclusive and inherently incompatible; and it constructs the Other to be also morally inferior (Hansen Citation2006). A disaggregated recognition can take the form of changing the narratives about the Other along one of these dimensions and not others. For example, reconstructing the temporal dimension, Self can begin to represent itself as advanced and the Other as backward along a historical path (Hansen Citation2006; Strömbom Citation2014), and thereby open up the possibility of the Other becoming like Self in the future, despite being incompatibly different at present. Alternatively, reconstructing the spatial dimension, agonistic recognition can take the form of recognising hybrid or dual identities and contexts of peaceful coexistence even as the Other, as a general category, is ascribed a historically fixed and morally inferior identity.

Disaggregated recognition also guards against the development of an identity backlash. Partial recognition of the Other along certain constitutive dimensions reduces the likelihood of the development of ontological dissonance as there remains considerable overlap between the established and the new narratives on the Other along other constitutive dimensions (Rumelili Citation2015). Keeping certain aspects of Self/Other differentiation intact lowers the risk that recognition will cause significant disruption to the established narratives and thereby generate ontological insecurity.

In sum, the above elements of agonistic recognition lower the risk of recognition spurring an identity backlash along the pathways identified in the previous section. In the following sections, we discuss how the initially promising recognition processes in Israel in the 1990s onwards with respect to the Palestinian Other and in Turkey during the 2000s regarding the Greek Other culminated in strong identity backlashes. The two recognition processes are assessed in terms of the elements of agonistic recognition identified above.

Recognition and identity backlash in Israel

Since the foundation of Israel in 1948, continuous conflict – first with its surrounding states and later with the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) protesting the occupation of West Bank and Gaza – shaped a securitised self-narrative of Israel as a small defensive David, facing an Arab Goliath, intent on the full destruction of the Israeli state and its people (Sucharov Citation2005). Furthermore, Israeli identity was based on a negation of Palestinian claims to land and national identity (Ram Citation2003). As Uriel Abulof (Citation2015) and Amir Lupovici (Citation2015) have poignantly noted, the construction of Israeli nationhood relied heavily on a picture of the collective self under constant threat from a hostile surrounding world in general and the Palestinian collective in particular (Sucharov Citation2005). Such construction of Israeli identity as heavily securitised has left heavy imprints on all attempts to negotiate peace.

In the 1990s, Israel, after years of secret backchannel talks, decided to recognise the Palestinians (PLO) as a legitimate negotiation partner, and the PLO in turn, after decades of refusing to negotiate with Israel, decided to enter a formal peace process in 1993, starting with the signing of the declaration of principles in Oslo. The peace process was not welcomed by all in Israel, yet it enjoyed quite widespread support by broad swathes of the people who took part in a then-vivid peace movement (Strömbom Citation2013). The formal recognition granted to the PLO, as the Palestinian people’s official representative body, in the Oslo Accords, implicitly gave voice to broader Palestinian identity and recognition claims (Barnett Citation2009). It also triggered soul-searching debates in Israeli academic circles, domestic politics and media about national identity, image and history (Ram Citation2003).

As the peace process was on track, between 1993 and 2000, a post-Zionist narrative raising issues previously muted to the public debate grew stronger in Israel. For example, the New History debates, which had begun in the late 1980s at the opening of previously classified archives from the 1948 War, were disseminated in heated debates in newspapers and on broadcast television. These debates opened up for questioning of the legitimacy of Israeli actions towards the Palestinians during the founding war of 1948, which up until then had remained a taboo topic in the Israeli discourse (Nets-Zehngut and Bar-Tal Citation2014). The discussion of specific injustices – such as Israeli massacres of Palestinian villages (Bronner Citation1999) – in the public sphere triggered responses echoing anxiety, panic and ontological insecurity (Brunner Citation2002) among the defenders of mainstream Zionist narratives, who in response sought to re-assert traditional identity narratives and the stable boundary between Self and Other. Since the new narratives of the 1948 War depicted a fundamental shift in Self- and Other-images of Israelis and well as Palestinians, it displayed ontological dissonance with regards to traditional and novel narratives. Even though the novel recognition narratives were highly contested and marginal, they resonated with parts of the political establishment. The education ministry initiated changes in school curriculums and welcomed new history textbooks to incorporate new narratives also including Palestinian identity claims (Schnell Citation1998), which seemed to unleash ontological insecurity among defenders of traditional Zionism, in right-wing as well as leftist camps.

This post-Zionist discourse undermined the moral certainty gained from the narratives of constant historical victimisation of the Self, and instead represented Israel as a state ‘born in sin’ (Morris Citation1990, p. 15). The incrementally growing recognition of the Palestinian Other in certain spheres unsettled the Israeli ‘defensive warrior identity’ (Sucharov Citation2005, p. 34) of being a victim in constant need of a militarised defence against continuous external threats (Strömbom Citation2014), which serves as an explanation for the ontological insecurity spurred at the time. The Israeli self-image as defensive and vulnerable was then partly challenged by images of Israelis performing cruel and offensive acts, whereas Palestinians, who to that point had been described as cunning perpetrators, were depicted as weak victims of Israeli aggression in the novel recognition narratives (Ram Citation2003). As indicated in our theoretical elaborations, these types of narrative shifts as well as the strong reactions to them pinpoint the inherent dynamics of heightened ontological insecurity and its repercussions in fortified identity constructions.

Elements of agonistic recognition?

The declaration of principles signed in Washington, DC, in 1993 made no mention of how reconciliation claims were to be included in the formal peace process. The peace process offered little to no guidance on how to handle identity claims, as it lacked platforms on which novel identity claims could be discussed. This points to a non-finalist approach, yet also displays the unwillingness of the elites negotiating the agreement to mention the emotionally laden and potentially controversial identity aspects of the conflict. Furthermore, a pluralist multilogue was quite absent in the heated domestic Israeli debates on identity that took place during the 1990s and afterwards, which resulted in an exceptionally polarised political climate in Israeli society. The proponents of established and changed narratives were constituted as unitary and increasingly antagonistically opposed groups. Hardliners as well as moderates refused to tolerate narratives that did not coalesce with their own. An example of a multilogue, although more dyadic than pluralist, was The Shared Histories project – where Israeli and Palestinian historians co-produced texts for Israeli and Palestinian schools. By keeping a low profile, working with multiple overlapping narratives for education in joint dialogue, they wanted to contribute to a stickiness of narratives of recognition, through a strategy of continuous, yet non-confrontational multilogue:

at the present stage of hostility and violence, the Israeli Jews and the Palestinians are not able to develop a joint narrative of their history (nor do we expect them to do so). Nevertheless, in the meantime, they could learn to acknowledge and live with the fact that there are at least two competing narratives to account for their past, present, and future. (Adwan and Bar-On Citation2004, p. 15)

Also, Israeli popular culture picked up the new recognition narratives, perhaps most notably in the television series T’kumma, a 22-part historical documentary, aired on national television to celebrate Israel’s 50-year anniversary in 1998. In many respects, the series is representative of multilogue because it portrayed the Israeli as well as the Palestinian perspectives. The writer-director of the episode that portrayed Palestinian armed resistance in the fight to return to their land stated: ‘We Israelis think that we have a monopoly on blood, tears and pain, but of course this is not true. We know our side in this story. I wanted to present the other side, loudly’ (quoted in Schnell Citation1998, 1).

Israeli media paid great attention to T’kumma, which had unexpectedly high ratings (Schnell Citation1998, 2). This points to a gradual shift in Israeli education policy and culture where new narratives started to seep into channels of communication, with a possibility to also start affecting the broader public. However, attempts to display various narratives side-by-side tended to spark zero-sum debates in which one or the other narrative was seen as superior and destined to rule out the other, which is anathema to a multi-logical approach and precludes and weakens agonistic potential.

In Israeli debates on recognition, attempts at disentangling different dimensions of Israeli/Palestinian identity constructions remained few and marginal. For example, some actors sought to disentangle spatial and moral aspects of recognition, by acknowledging that Israel caused suffering and tragedy for Palestinians in 1948, while insisting that the acknowledgement of this past moral responsibility need not justify dissolving present spatial distinctions by bringing back all refugees (Hirsch Citation2007). However, the overall logic in the debate was to reiterate and re-enforce narratives which kept spatial, temporal and moral aspects intact, or narratives that implied far-ranging changes along all three axes. In short, the promoters of recognition of Palestinian history not only recognised the previous taboo of Palestinian refugeehood and suffering, but also explicitly projected negative attributes onto the Israeli Jews, who were portrayed as cunning and immoral during the Independence War. The promoters of ‘traditional’ identity upheld the separation between Israelis and Palestinians along the three axes, in attempts to return to routinised narratives of recognition.

Identity backlash

With the increase in violence in the latter part of the 1990s, the momentum in peace negotiations started to falter. In 1994, Baruch Goldstein, an Israeli Jewish extremist, killed 29 praying Palestinians in a Hebron mosque, and radical factions of Hamas and Islamic Jihad subsequently carried out several suicide bombings in Israeli towns. A majority of the Israeli population still supported the peace process, but the growing violence started to affect the public (Shamir and Shikaki Citation2002). The spectacular violence peaked in 1995 when Jewish Israeli Yigal Amir assassinated Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin, which was indicative of the ontological dissonance between new and old narratives and the deepening rifts in Israeli society. The downspiralling relations left the floor open for peace spoilers from both sides, playing on increased fear and distrust in both societies. The meagre results of the peace process and the increased violence led the public to lose faith in the peace process, and tensions increased. In September 2000, a 12-year-old Palestinian boy and his father were caught in a crossfire, ending with the boy being shot to death by an Israeli soldier. In the same year, two Israeli soldiers were killed by a lynch mob in central Ramallah. Pictures of the dead boy together with his grieving father, and of cheering, bloodstained Palestinians with the two dead Israeli soldiers, were broadcast around the world. The rhetoric of promoters of the traditional Israeli national narratives tied into the general development of the conflict, which opened up ample room for delegitimation of recognition of Palestinians. Strong actors in the government, for example, took measures to obstruct further spread of the new narratives of identity in education. History textbooks were again loudly debated, ending in the banning of many of the new books (Naveh Citation2006). They were seen as unfaithful to the traditional narratives, overlooking central events in Zionist history (Al-Haj Citation2005). Then Communications Minister Limor Livnat harshly criticised the T’kumma series, claiming that it was propaganda from Israel’s enemies (Schnell Citation1998). She asked rhetorically: ‘Why do we have to sit on the defendant’s bench in a series run by public broadcasting in Israel?’ (quoted in Schnell Citation1998).

Thus, the general climate for voicing narratives of recognition deteriorated in the late 1990s. During the negotiations in Taba in 2001, the issue of return of Palestinian refugees was brought to the table for the first time (Hirsch Citation2007). The novel recognition narratives were now aired in negotiations, which during the talks and in their aftermath brought possible policy implications of recognising the Naqba to the fore – showcasing a path to the future where Palestinian identity claims could possibly result in the bringing of Palestinians from the diaspora back to Israeli lands.

It is by now a well-known fact that Taba was a massive negotiation failure. The breakdown and backlash following Taba closed down attempts at recognition in official negotiation, and the new narratives became increasingly linked to de-legitimation of the existence of the Israeli state. During this time, influential actors made efforts to point out disastrous images of the future that would result if the new narratives of recognition were to prevail and influence politics vis-á-vis the Palestinians, where the right of return for Palestinian refugees was one of the most feared and discussed consequences. This ontological dissonance and the heightened feelings of ontological insecurity brought about by the new narratives also resonated with the Israeli public. In a poll of Israelis conducted in 2002, more than 90% of the participants associated a right of return of Palestinian refugees with negative attributes, such as ‘destruction of the state’, ‘massacre of the Jews’ and even ‘Holocaust’ (Zakay and Klar Citation2002). Influential politicians and interest groups fighting new recognition narratives were successful in their avoidance efforts, which reflected the official peace process that stagnated with the start of the second Intifada in 2001, and the political as well as identity backlash which from then on has precluded continued elaboration of recognition claims in Israeli culture, education and media, deteriorating relations between Israeli and Palestinian elites where refusal to recognise the Other (Freedman Citation2021) has become increasingly adamant and mutually re-enforcing. That, together with scant elements of agonistic recognition in the conflict transformation process, has created relational ruptures within Israeli society and with its Palestinian counterpart, which has re-introduced severely antagonistic relations.

Recognition and identity backlash in Turkey

Much like in Israel, a sense of being under constant threat to its territorial integrity is a central theme in Turkish national identity narratives, nurtured by the official remembrance of the long and painful break-up of the Ottoman Empire in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries (Adisonmez Citation2019). In particular, the Greek occupation of Western Anatolia in the aftermath of the First World War, thwarted by Turkish nationalist forces led by Kemal Ataturk, strongly ingrained in the Turkish national consciousness an image of Greece as a conniving and deceitful state, always aiming to gain more territory from Turkey. From the emergence of the Cyprus conflict in the mid-1950s to the late 1990s, the two states came to the brink of war on multiple occasions over Cyprus and territorial disputes over the Aegean continental shelf, airspace and small islets in the Aegean Sea. The ongoing militarised disputes lent credibility to the mutually exclusive and securitised narratives about the Other in both countries and became a source of ontological security for the two states facing significant domestic turmoil in a volatile region on the periphery of Europe (Rumelili Citation2003, Citation2019).

Conflict transformation in Greek–Turkish relations was initiated by the two countries’ foreign ministers, boosted by the societal empathy triggered by the deadly earthquakes in the two countries in the summer of 1999 (Ker-Lindsay Citation2007), and was consolidated with the declaration of Turkey’s EU candidacy in December 1999. This declaration was predicated on a political deal between Greece and Turkey where Greece would not impose a veto in return for Turkey agreeing to take the bilateral disputes to the International Court of Justice if bilateral negotiations did not yield results by 2004 (Rumelili Citation2007).

In Turkey, the prospect of membership in the EU unleashed a broader emotional and cognitive openness to re-constructing established identity narratives. Believing that globalisation and the EU membership process were putting Turkey on a solid trajectory towards democracy, multi-culturalism and market economy, liberal Turkish intellectuals pushed for a critical engagement with the past that encompassed the foundational Kemalist values of the Turkish republic (Ayturk Citation2015). Just like in Israel, a number of taboo subjects in Turkish political discourse, such as the Armenian genocide, discriminatory policies towards non-Muslim minorities, and Kurdish minority rights, began to be openly discussed. In this period, the ontological dissonance created by the unsettling of established identity narratives was widespread among the secular opposition to the Adalet ve Kalkinma Partisi [Justice and Development Party] government, visibly manifest in the massive ‘Republic Rallies’ held in major Turkish cities in 2007 (Cinar and Tas Citation2017). But it could have only limited political effect as long as the alternative self-narrative of a European Turkey allayed the anxieties associated with departing from entrenched hardliner positions on a variety of so-called national issues.

Hence, recognition of the Greek Other emerged as a by-product of a broader process of identity change in Turkey. Recognising the importance of human rights in the context of EU-driven reforms brought attention to the plight of the dwindling Greek minority in Istanbul and the injustices they suffered in the 1950s and 1960s (Ors Citation2006; Kaliber Citation2019). The norm of peaceful neighbourly relations in Europe and a critical approach towards the role of the military in Turkish politics triggered a re-consideration of the merits of militarist approaches to managing Greek–Turkish disputes. Although the two states did not settle their territorial disputes in bilateral negotiations or by submitting them to the ICJ as originally agreed, conflict transformation was independently maintained by inter-societal dynamics. Cultural products rekindling memories of a shared past, such as the 2003 Greek movie Politiki Kouzina (Kitchen of Istanbul) and the prime-time Turkish TV drama series Yabanci Damat (Foreign Groom) (Rumelili Citation2005), gained significant popularity, even though they were not as deeply linked to the conflict as in Israel. The Foundation of Lausanne Treaty Emigrants was established in Istanbul in 2001, organised a number of visits for émigrés from the 1923 Population exchange to visit their ancestral homelands. The number of travellers across the Aegean increased exponentially, reaching a peak of 1.5 million in 2017 – be they tourists from Turkey exploring the Aegean islands or Greek travellers on daily shopping trips and visiting Orthodox holy sites in Istanbul (Tsarouhas Citation2019).

Indeed, throughout the 2000s, Greek–Turkish relations appeared almost irrevocably transformed. Turkey’s EU membership became the focal point of bilateral cooperation. Greece, which had persistently vetoed any advances in relations between Turkey and the EU in the past, became the most ardent supporter of Turkey’s EU membership in the 2000s (Agnantopoulos Citation2013). The two states also successfully managed to isolate their bilateral relations as much as possible from the ups and downs experienced in the Cyprus problem following the rejection of the Annan plan by the Greek Cypriots in 2004.

Elements of agonistic recognition?

The process of recognition in Greek–Turkish relations was non-finalist, in the sense that there was no expectation of the acceptance of specific demands and restitution or apology for specific wrongs. The bilateral negotiations over the Aegean disputes were conducted in secret by expert bureaucrats (Heraclides Citation2010), and the fact that they until recently could remain in oblivion in the absence of a resolution indicates that their resolution was not a precondition for progress in recognition in the two societies. Policy changes contributing to recognition in the two countries were driven mostly by independent dynamics rather than by reciprocity. For example, in 2006 Turkish government officials justified EU-driven legal changes to grant non-Muslim foundations in Turkey rights that are denied to Turkish minority foundations in Greece on the grounds that European human rights law imposed parallel obligations on Greece and Turkey, and that the non-implementation of these rights in Greece would not excuse their non-implementation in Turkey (Radikal Citation2006).

After 1999, the European integration process provided Turkey with an alternative framework of meaning, or source of ontological security (Rumelili Citation2018), which paved the way for the development of a disaggregated recognition of the Greek Other. This recognition was premised on replacing the inherent distinction between the Turkish Self and Greek Other with the temporal one of Europeanisation (Rumelili Citation2007). As Turkey re-cognised itself as a potential European state, it began to also re-cognise Greece as a co-European – albeit lagging – partner, rather than an antagonistic pawn of European imperialism (Rumelili Citation2007). Within this changed structure of meaning, actions that would otherwise be deemed provocative could be dismissed as old habits that the Other will eventually outgrow. This distinction between present-day tensions and a future of guaranteed friendship was, for example, poignantly visible in the following remarks of a Turkish journalist in 1999: ‘No one can believe that Turkey and Greece, who have come together in the same family, will remain foes from now on’ (Rumelili Citation2008, 122). Conversely, such an alternative encompassing framework of meaning within which Israeli and Palestinian identities could change was not present in Israeli–Palestinian relations.

However, the process of recognition was not necessarily pluralist or multilogical. The actors who were committed to Greek–Turkish cooperation and to Turkey’s EU membership took centre stage in the recognition process (Birden and Rumelili Citation2009; Karakatsanis Citation2014), and there was no effort to establish dialogue with nationalist hardliners within and across the two conflict societies. This cultivated among the moderates in the two societies a kind of wishful misperception that the Other had completely and irrevocably changed. Additionally, the dialogues of recognition were structured along interstate/intersocietal (Greek/Turkish) lines, and actors who would potentially diversify the positions, such as the Turkish/Muslim minority in Greece and the Greek/Rum minority in Turkey, were involved only in joint minority group meetings (Birden and Rumelili Citation2009, 327), and not in an overall dialogue with majority groups in the two societies. Hence, once the alternative framework of meaning provided by European integration, which had allowed for disaggregated recognition, dissipated, it was relatively easy for the established narratives of inherent antagonism, which had remained dormant yet intact, to reclaim the centre stage (Heraclides Citation2019).

Backlash – ontological insecurity and return to conflict

Starting in the 2010s, the weakening of its membership prospects, coupled with its newfound confidence as an emerging power, undermined Turkey’s commitment to EU membership (Rumelili and Suleymanoglu-Kurum Citation2017; Aydın-Düzgit and Kaliber Citation2016). Societal anxiety regarding the future direction of the country spilled over from the opposition to the public, and the void left by the unsettling of the established institutions and an incomplete EU-driven reform process paved the way for opportunistic factional struggles within Turkish military and bureaucracy. Ontological insecurity intensified as Turkey’s neo-Ottomanist power ambitions floundered in the unforeseen security challenges posed by the Syrian civil war, and especially following the failed coup attempt of 2016, the AKP government returned to the closed militant nationalism of the 1990s, characterised by a pervasive sense of outside threat and readiness to achieve its objectives through military force (Adisonmez and Onursal Citation2020).

From the mid-2010s onwards, starting with the Kurdish Other, the recognition processes of the previous decade began to be radically reversed (Geri Citation2017; Rumelili and Çelik Citation2017). Initially, Greek–Turkish relations were spared from the identity backlash, suggesting a more resilient recognition. With growing trade and tourism, the economic and societal links continued to flourish between the two countries. Following the 2016 EU–Turkey Migration Agreement, the two states instituted effective functional cooperation in border control (Gregou Citation2019). While the nationalist discourse became more prevalent in the two countries, it was mainly directed towards other targets, such as Germany and the US, rather than towards the Greek or Turkish Other (Gkintidis Citation2013). Turkish foreign policy statements continued to refer to Greece as a neighbour, ally or friend, in fact more often than Greek officials would for Turkey (Turkes-Kilic Citation2019).

However, starting in 2018, the Aegean disputes have been rekindled, with aggressive rhetoric and action on both sides, and subsequently broadened to the delimitation of exclusive economic zones in the Eastern Mediterranean. Tense stand-offs involving the stationing of research vessels and warships in contested maritime areas, competing delimitation agreements signed with Egypt (Greece) and Libya (Turkey) to mark maritime boundaries, and Greece and Cyprus lobbying the EU to impose sanctions on Turkey brought back representations of Greece as a pawn of imperialist Western powers, ‘a state that has throughout history survived by hiding behind others’, as Erdogan described it recently (quoted in Deutsche Welle Turkiye Citation2020). Opinion polls indicate a rapid rise in public perceptions of threat from Greece, from 10.2% in 2007 to 59% in 2020 (Durmuşlar and Ovalı Citation2019, 221).

Conclusion

This article has elaborated on the inherent volatility and vulnerability of recognition in processes of conflict transformation. It has elucidated how recognition processes may be prone to generating identity backlashes, leading to the reification of stable and antagonistic boundaries between Self and Other. We have argued that one primary reason for such identity backlashes is the ‘totalistic’ character of recognition, which is often generative of ontological insecurity and dissonance. As an alternative, we have proposed and developed the notion of agonistic recognition, which, we have argued, possibly enables the transformation of narratives on Self and Other without spurring such ontological insecurity and dissonance.

Thereby, two significant theoretical contributions have been advanced. First, we have connected the thus far disparate literatures on recognition and ontological (in)security in conflict transformation in our theoretical conceptualisation of the underlying processes of identity backlash. Secondly, our development of the notion of agonistic recognition, based on the three elements of non-finalism, pluralist multilogue and disaggregation, constitutes a valuable elucidation of agonistic peace theory, in terms of how identity and relationship transformation may unfold in agonistic ways and serve as crucial stepping-stones for peace.

Empirically, we have drawn on past experiences of identity transformation and recognition in Israeli and Turkish societies related to the long-standing conflicts in which they both are entangled. Our main empirical conclusion is that both societies underwent noteworthy recognition processes, which did not incorporate all elements of agonistic recognition identified here, and consequently the recognition processes spurred ontological insecurity and dissonance and led to varying degrees of identity backlash. The current state of relations suggests that the backlash experienced in Israel–Palestine relations is stronger than the one experienced in Greek–Turkish relations. While the future remains uncertain, we have suggested that this difference in outcomes could at least partly stem from the fact that recognition in the Turkish case incorporated more agonistic elements, whereas agonistic recognition was almost absent in the Israeli case. In Turkey, these agonistic elements of recognition were further bolstered initially by Turkey’s EU accession process, which provided an alternative source of ontological security and curbed the potential ontological insecurity arising out of the recognition of the Greek Other. However, the subsequent weakening of Turkey’s membership prospects in the EU aggravated Turkey’s ontological insecurity and the backlash against Greece. In contrast, the Israeli/Palestinian recognition process possessed no similar exogenous source of ontological security.

This study has contributed crucial theoretical as well as empirical insights to the study of conflict transformation at the intersection of the literatures on ontological security, recognition and agonistic peace. We hope that our attempt at linking these fields will spur other researchers to further explore how the pursuit of agonistic peace offers a potential remedy against challenges frequently experienced in identity and conflict transformation.

Acknowledgements

We extend our sincere thanks to two anonymous reviewers who pushed us to make a stronger and more coherent article. We have furthermore made substantial improvements to our arguments based on poignant comments from our colleagues, first at a panel on Agonistic Peace and Identity Change at the ECPR General Conference in Wroclaw in 2019 and then at a virtual workshop that was arranged for all authors of this special issue by the PUSHPEACE project in Lund, in November 2020. Any mistakes herein, though, remain our own. Both authors contributed equally to the writing of this piece.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Bahar Rumelili

Bahar Rumelili is Professor and Jean Monnet Chair at the Department of International Relations, Koc University, Istanbul. Her research focuses on international relations theory, processes of European identity construction, conflict resolution and the interaction between the EU and Turkish politics and civil society. She is the author of Constructing Regional Community and Order in Europe and Southeast Asia (Palgrave, 2007) and the editor of Conflict Resolution and Ontological Security: Peace Anxieties (Routledge 2015). Her articles have appeared in journals such as European Journal of International Relations, Review of International Studies, Journal of Common Market Studies, Security Dialogue, and Journal of International Relations and Development.

Lisa Strömbom

Lisa Strömbom is Associate Professor in the Department of Political Science, Lund University, Sweden, where she is the former Director for Peace and Conflict Research. Her work centres on conflict transformation, identity politics, recognition and agonism, with a particular interest in identity dynamics of the Israeli–Palestinian conflict. She has published articles in journals including the European Journal of International Relations, Global Society, Journal of International Relations and Development, Peacebuilding, Space and Polity and Third World Quarterly. She is the author of the book Israeli Identity, Thick Recognition and Conflict Transformation (Palgrave 2013).

Bibliography

- Abulof, U. 2015. The Mortality and Morality of Nations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Adisonmez, U. 2019. “When conflict traumas fragment: Investigating the socio-psychological roots of Turkey’s intractable conflict.” Political Psychology 40 (6): 1373–1390.

- Adisonmez, U. C., and R. Onursal. 2020. “Governing Anxiety, Trauma and Crisis: The Political Discourse on Ontological (in)Security after the July 15 Coup Attempt in Turkey.” Middle East Critique 29 (3): 291–306. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/19436149.2020.1770445.

- Adwan, S., and D. Bar-On. 2004. “Shared History Project: A PRIME Example of Peace-Building under Fire: Palestinian-Israeli Relations.” International Journal of Politics Culture and Society 17 (3): 513–521.

- Aggestam, K., F. Cristiano, and L. Strömbom. 2015. “Towards Agonistic Peacebuilding? Exploring the Antagonism–Agonism Nexus in the Middle East Peace Process.” Third World Quarterly 36 (9): 1736–1753. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2015.1044961.

- Agnantopoulos, A. 2013. “The Europeanization of National Foreign Policy: Explaining Greek Support for Turkey’s Accession.” Southeast European and Black Sea Studies 13 (1): 67–87. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14683857.2013.773173.

- Al-Haj, M. 2005. “National Ethos, Multicultural Education, and the New History Textbooks in Israel.” Curriculum Inquiry 35 (1): 47–71. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-873X.2005.00315.x.

- Allan, P., and A. Keller, eds. 2006. What is a Just Peace? Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Alter, K. J. and M. Zurn. 2020. “Conceptualising backlash politics: Introduction to a special issue on backlash politics in comparison.” British Journal of Politics and International Relations 22 (4): 563–584.

- Aydın-Düzgit, S., and A. Kaliber. 2016. “Encounters with Europe in an Era of Domestic and International Turmoil: Is Turkey a De-Europeanising Candidate Country?” South European Society and Politics 21 (1): 1–14. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13608746.2016.1155282.

- Ayturk, I. 2015. “Post-Post Kemalizm: Yeni Bir Paradigmayi Beklerken.” Birikim 319: 34–48.

- Bar-Tal, D. 2000. “From Intractable Conflict through Conflict Resolution to Reconciliation: Psychological Analysis.” Political Psychology 21 (2): 351–365.

- Barnett, M. 2009. “Culture, Strategy and Foreign Policy Change: Israel’s Road to Oslo.” European Journal of International Relations 5 (19): 1–36.

- Birden, R., and B. Rumelili. 2009. “Rapprochement at the Grassroots: How Far Can Civil Society Engagement Go?.” In In the Long Shadow of Europe: Greeks and Turks in the Era of Postnationalism, edited by O. Anasthakis, K. Nicolaidis and K. Oktem, 315–330. Leiden: Brill.

- Bronner, E. 1999. “Israel’s History Textbooks Replace Myth with Facts.” New York Times.

- Brunner, J. 2002. “Contentious Origins. Psychoanalytic Comments on the Debate over Israel’s Creation.” In Psychoanalysis, Identity, and Ideology: Critical Essays on the Israel/Palestine Case, edited by J. Bunzl and B. Beit-Hallahmi, 107–135. Boston: Kluwer.

- Buckley-Zistel, S. 2008. Conflict Transformation and Social Change in Uganda: Remembering after Violence. London: Palgrave MacMillan.

- Bush, B., and J. Folger. 2005. The Promise of Mediation. The Transformative Approach to Conflict. San Francisco: Jossey Bass.

- Cinar, A., and H. Tas. 2017. “Politics of Nationhood and the Displacement of the Founding Moment: Contending Histories of the Turkish Nation.” Comparative Studies in Society and History 59 (3): 657–689.

- Connolly, W. 1991. Identity/Difference. Democratic Negotiations of Political Paradox. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

- Connolly, W. E. 1995. The Ethos of Pluralization. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Deutsche Welle Turkiye. 2020. “Erdoğan Yunanistan ve AB’ye Çıkıştı.” September 1. https://www.dw.com/tr/erdo%C4%9Fan-yunanistan-ve-abye-%C3%A7%C4%B1k%C4%B1%C5%9Ft%C4%B1/a-54781253

- Durmuşlar, T., and A. S. Ovalı. 2019. “Greece’s Portrayal by the Turkish Print Media: A Comparative Study on Conjunctural Images.” In Greece and Turkey in Conflict and Cooperation: From Europeanization to De-Europeanization, edited by A. Heraclides and G. A. Cakmak, 210–223. London: Routledge.

- Freedman, J. 2021. “The Recognition Dilemma: Negotiating Identity in the Israeli–Palestinian Conflict.” International Studies Quarterly 65 (1): 122–135. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/isq/sqaa091.

- Galtung, J. 1996. Peace by Peaceful Means. Peace and Conflict, Development and Civilization. London: Sage.

- Geri, M. 2017. “The Securitization of the Kurdish Minority in Turkey: Ontological Insecurity and Elite’s Power Struggle as Reasons of the Recent Re-Securitization.” Digest of Middle East Studies 26 (1): 187–202. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/dome.12099.

- Giddens, A. 1991. Modernity and Self-Identity: Self and Society in the Late Modern Age. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Gkinditis, D. 2013. “Rephrasing Nationalism: Elite Representations of Greek-Turkish Relations in a Greek Border Region.” Southeast European and Black Sea Studies 13 (3): 455–468.

- Gregou, M. 2019. “Conditionality, Migration Control and Bilateral Disputes: The View from the Greek – Turkish Borders in the Aegean.” Mediterranean Politics 24 (1): 84–105. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13629395.2017.1380117.

- Gustafsson, K. 2016. “Routinized Recognition and Anxiety: Understanding the Deterioration in Sino-Japanese Relations.” Review of International Studies 42 (4): 613–633. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0260210515000546.

- Hansen, L. 2006. Security as Practice: Discourse Analysis and the Bosnian War. London: Routledge.

- Heraclides, A. 2019. “The Greek-Turkish Antagonism.” In Greece and Turkey in Conflict and Cooperation: From Europeanization to De-Europeanization, edited by A. Heraclides and G. A. Cakmak, 41–65. London: Routledge.

- Heraclides, A. 2010. The Greek-Turkish Conflict in the Aegean: Imagined Enemies. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hirsch, M. B.-J. 2007. “From Taboo to the Negotiable: The Israeli New Historians and the Changing Representation of the Palestinian Refugee Problem.” Perspectives on Politics 5 (2): 241–258.

- Honneth, A. 1995. The Struggle for Recognition: The Moral Grammar of Social Conflicts. Cambridge: Polity.

- Kaliber, A. 2019. “Re-Engaging the Self/Other Problematic in Post-Positivist International Relations: The 1964 Expulsion of Greeks from Istanbul Revisited.” Southeast European and Black Sea Studies 19 (3): 365–386. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14683857.2019.1651082.

- Karakatsanis, L. 2014. Turkish-Greek Relations: Rapprochement, Civil Society, and the Politics of Friendship. London: Routledge.

- Ker-Lindsay, J. 2007. Crisis and Conciliation: A Year of Rapprochement between Greece and Turkey. London: I.B. Tauris.

- Kriesberg, L. 1998. Constructive Conflicts: From Escalation to Resolution. Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Labov, W. 2006. “Narrative Pre-Construction.” Narrative Inquiry 16 (1): 37–45. doi:https://doi.org/10.1075/ni.16.1.07lab.

- Lehti, M., and V. Romashov. 2021. “Suspending the Antagonism: Situated Agonistic Peace in a Border Bazaar.” Third World Quarterly. (this issue).

- Lupovici, A. 2012. “Ontological Dissonance, Clashing Identities, and Israel’s Unilateral Steps towards the Palestinians.” Review of International Studies 38 (4): 809–833. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0260210511000222.

- Lupovici, A. 2015. “Ontological Security and the Israeli-Palestinian Peace Process: Between Unstable Conflict and Conflict in Resolution.” In Conflict Resolution and Ontological Security, edited by B. Rumelili, 333–352. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Maddison, S. 2015. “Relational Transformation and Agonistic Dialogue in Divided Societies.” Political Studies 63 (5): 1014–1030. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9248.12149.

- Mälksoo, M. 2015. “Memory Must Be Defended’: Beyond the Politics of Mnemonical Security.” Security Dialogue 46 (3): 221–237. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0967010614552549.

- Markell, P. 2003. Bound by Recognition. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Mitzen, J. 2006. “Ontological Security in World Politics: State Identity and the Security Dilemma.” European Journal of International Relations 12 (3): 341–370. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066106067346.

- Morris, B. 1990. “The New Historiography: Israel and Its past.” In Making Israel, edited by B. Morris, 11–48. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Mouffe, C. 2005. On the Political. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Mouffe, C. 2013. Agonistics: Thinking the World Politically. London: Verso.

- Nagle, J. 2014. “From the Politics of Antagonistic Recognition to Agonistic Peacebuilding: An Exploration of Symbols and Rituals in Divided Societies.” Peace & Change 39 (4): 468–494. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/pech.12090.

- Naveh, E. 2006. “The Dynamics of Identity Construction in Israel through Education in History.” In Israeli and Palestinian Narratives of Conflict: History’s Double Helix, edited by R. I. Rotberg, 244–270. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Nets-Zehngut, R., and D. Bar-Tal. 2014. “Transformation of the Official Memory of Conflict: A Tentative Model and the Israeli Memory of the 1948 Palestinian Exodus.” International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society 27 (1): 67–91. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10767-013-9147-6.

- Northrup, T. 1989. “The Dynamic of Identity in Personal and Social Conflict.” In Intractable Conflicts and Their Transformation, edited by L. Kriesberg, T. A. Northrup, and S. J. Thorson, 55–82. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press.

- Ors, I. 2006. “Beyond the Greek and Turkish Dichotomy: The Rum Polites of Istanbul and Athens.” South European Society and Politics 11 (1): 79–94.

- Owen, D. 2012. “Tully, Foucault and Agonistic Struggles over Recognition.” In Recognition Theory and Contemporary French Moral and Political Philosophy. Reopening the Dialogue, edited by M. Bankovsky and A. LeGoff, 133–165. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Peterson, J. 2013. “Creating Space for Emancipatory Human Security: Liberal Obstructions and the Potential of Agonism.” International Studies Quarterly 57 (2): 318–328. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/isqu.12009.

- Radikal. 2006. “CHP’nin İtirazı: Karşılıklılık İlkesi Yok Sayıldı, İhanet!” September 22. http://www.radikal.com.tr/politika/chpnin-itirazi-karsiliklilik-ilkesi-yok-sayildi-ihanet-792449/

- Ram, U. 2003. “From Nation-State to Nation—State. Nation, History and Identity Struggles in Jewish Israel.” In The Challenge of Post-Zionism. Alternatives to Israeli Fundamentalist Politics, edited by E. Nimni, 20–42. New York: Zed Books.

- Rose, G. 1995. Love’s Work: A Reckoning with Life. New York: Schocken Books.

- Rumelili, B. 2003. “Liminality and the Perpetuation of Conflicts: Turkish-Greek Relations in the Context of the Community-Building by the EU.” European Journal of International Relations 9 (2): 213–248. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066103009002003.

- Rumelili, B. 2004. “Constructing Identity and Relating to Difference: Understanding EU’s Mode of Differentiation.” Review of International Studies 30 (1): 27–47. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0260210504005819.

- Rumelili, B. 2005. “The European Union and Cultural Change in Greek-Turkish Relations.” Working Paper Series in EU Border Conflicts Studies, no. 17. Birmingham: University of Birmingham.

- Rumelili, B. 2007. “Transforming Conflicts on EU Borders: The Case of Greek-Turkish Relations.” JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 45 (1): 105–126. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5965.2007.00705.x.

- Rumelili, B. 2008. “Transforming the Greek-Turkish Conflicts: The EU and ‘what we make of it.” In The European Union and Border Conflicts, edited by T. Diez, S. Stetter, and M. Albert, 94–128. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Rumelili, B. 2015. “Ontological (in)Security and Peace Anxieties: A Framework for Conflict Resolution.” In Conflict Resolution and Ontological Security, edited by B. Rumelili, 10–29. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Rumelili, B. and R. Suleymanoglu-Kurum. 2017. “Brand Turkey: Liminal Identity and its Limits.” Geopolitics 22 (3): 549–570.

- Rumelili, B. 2018. “Breaking with Europe’s Pasts: Memory, Reconciliation, and Ontological (in)Security.” European Security 27 (3): 280–295. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09662839.2018.1497979.

- Rumelili, B. 2019. “Back to the Future: Institutionalist International Relations Theories and Greek-Turkish Relations.” In Greece and Turkey in Conflict and Cooperation: From Europeanization to De-Europeanization, edited by A. Heraclides and G. A. Cakmak, 25–40. London: Routledge.

- Rumelili, B., and A. Çelik. 2017. “Ontological Insecurity in Asymmetric Conflicts: Reflections on Agonistic Peace in Turkey’s Kurdish Issue.” Security Dialogue 48 (4): 279–296. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0967010617695715.

- Rumelili, B., and J. Todd. 2018. “Paradoxes of Identity-Change: Integrating Macro, Meso and Micro Research on Identity in Conflict Processes.” Politics 38 (1): 3–18. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0263395717734445.

- Schaap, A. 2005. Political Reconciliation. London: Routledge.

- Schick, K. 2015. “Re-Cognizing Recognition: Gillian Rose’s “Radical Hegel” and Vulnerable Recognition.” Telos 173: 87–105.

- Schnell, I. 1998. “The Making of T’kuma. An Interview with Yigal Eilam.” Palestine-Israel Journal 5 (2). https://pij.org/articles/%20215.

- Shamir, J., and K. Shikaki. 2002. “Determinants of Reconciliation and Compromise among Israelis and Palestinians.” Journal of Peace Research 39 (2): 185–202. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343302039002003.

- Shinko, R. 2008. “Agonistic Peace: A Postmodern Reading.” Millennium: Journal of International Studies 36 (3): 473–491. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/03058298080360030501.

- Somers, M. 1994. “The Narrative Constitution of Identity: A Relational and Network Approach.” Theory and Society 23 (5): 605–649. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00992905.

- Strömbom, L. 2013. Israeli Identity, Thick Recognition and Conflict Transformation. Houndmills: Palgrave MacMillan.

- Strömbom, L. 2014. “Thick Recognition: Advancing Theory on Identity Change in Intractable Conflicts.” European Journal of International Relations 20 (1): 168–191. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066112439217.

- Strömbom, L. 2020. “Exploring Analytical Avenues for Agonistic Peace.” Journal of International Relations and Development 23 (4): 1–23. doi:https://doi.org/10.1057/s41268-019-00176-6.

- Sucharov, M. 2005. The International Self. Psychoanalysis and the Search for Israeli-Palestinian Peace. Albany: SUNY Press.

- Tsarouhas, D. 2019. “Greek-Turkish Economic Relations in a Changing Regional and International Context.” In Greece and Turkey in Conflict and Cooperation: From Europeanization to De-Europeanization, edited by A. Heraclides and G. A. Cakmak, 194–209. London: Routledge.

- Tully, J. 1999. “The Agonic Freedom of Citizens.” Economy and Society 28 (2): 161–182.

- Tully, J. 2000. “Struggles over Recognition and Distribution.” Constellations 7 (4): 469–482. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8675.00203.

- Tully, J. 2004. “Recognition and Dialogue: The Emergence of a New Field.” Critical Review of International Social and Political Philosophy 7 (3): 84–106. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1369823042000269401.

- Turkes-Kilic, S. 2019. “Accessing the Rapprochement in Its Second Decade: A Critical Approach to the Official Discourse between Turkey and Greece.” In Greece and Turkey in Conflict and Cooperation: From Europeanization to De-Europeanization, edited by A. Heraclides and G. A. Cakmak, 181–193. London: Routledge.

- Wendt, A. 2003. “Why a World State is Inevitable.” European Journal of International Relations 9 (4): 491–542. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/135406610394001.

- Wenman, M. 2003. “Agonistic Pluralism’ and Three Archetypal Forms of Politics.” Contemporary Political Theory 2 (2): 165–186. doi:https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.cpt.9300091.

- Wenman, M. 2013. Agonistic Democracy: Constituent Power in the Era of Globalization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Zakay, D. M., and Y. Klar. 2002. “Jewish Israelis on the ‘Right of Return’.” Palestine-Israel Journal 9 (2): 58–66.