Abstract

This article examines how non-governmental development organisations (NGDOs) balance their moral and organisational/financial incentives in the case of the European Union Emergency Trust Fund for Africa (EUTF). The EUTF was created in 2015 to support the European Union’s (EU’s) migration policy by addressing the ‘root causes’ of migration in Africa. The article analyses how NGDOs have reacted to the EUTF using qualitative textual analysis of publications and press releases, and finds that NGDOs have been highly critical of the EUTF’s underlying narrative, goals and implementation. Their positions align closely with the stated moral vision of supporting and empowering the global poor. Despite this critical position, many NGDOs have benefitted financially from the EUTF as project implementers. Regression analysis on the determinants of NGDO participation in EUTF projects reveals that NGDOs have largely avoided the more controversial migration management projects of the EUTF, and have focused mostly on projects that build resilience in local communities and support improving the lives and the rights of the poor in Africa. The case of the EUTF shows that NGDOs mostly practise what they preach, and while they did not abstain from the EUTF, they did not allow their financial incentives to fully dictate their actions either.

Introduction

Non-governmental development organisations (NGDOs) play important roles in the foreign aid system. They implement development projects, engage in advocacy towards donor and recipient governments, monitor governments and raise public awareness on development issues. In these roles, NGDOs constantly have to negotiate conflicting motivations: generally seen as driven by moral virtue, they also have strong organisational incentives to ensure their access to sustained sources of funding, and thus their survival. To gather these resources, NGDOs may need to make controversial decisions that can compromise their moral mission of helping the poorest (Banks, Hulme, and Edwards Citation2015), such as aligning with donor priorities, taking fewer risks or focusing on advocacy aimed at maximising their income (Szent-Iványi and Timofejevs Citation2021). While the fact that resource dependency alters the behaviour of NGDOs is well documented in the literature (Cooley and James Citation2002; Fruttero and Gauri Citation2005; Banks, Hulme, and Edwards Citation2015), it is unclear just how NGDOs make these decisions, and how they minimise any negative impacts that funding-driven actions have on their reputations as virtuous actors. In the case of funders who proclaim goals that are at odds with NGDO moral missions, organisations especially need to consider the reputational harm that bidding for funding carries.

This article aims to investigate how Northern/international NGDOs balance their moral and organisational/financial motivations in the case of a specific funding instrument, the European Union Emergency Trust Fund for Africa (EUTF). The EUTF, created in 2015 in the wake of the European refugee crisis, uses European Union (EU) aid to fund actions in Africa that reduce irregular migration, both by addressing the ‘root causes’ and by supporting the development of more effective border control and migration management systems in the region’s sending countries. Given the moral and humanitarian interests of NGDOs, it would be reasonable to expect them to contest these goals, criticise the EU for its approach, and argue for a more positive narrative of migration that puts the welfare and rights of displaced persons and other migrants at the forefront. On the other hand, the EUTF, as a new financial instrument, provides opportunities for NGDOs to bid for funding and increase their resources. Reviewing the literature on the conflicting motivations of NGDOs, the article formulates two expectations. First, NGDOs are likely to visibly signal their moral concerns about the EUTF through their rhetoric and advocacy. Second, if they do decide to take part in implementing projects financed by the fund, they will aim to minimise the reputational harm this participation may cause. In terms of rhetoric and advocacy, the article analyses how the EUTF, and more broadly the EU’s approach to the migration–development nexus, is framed in advocacy-related reports and other publications by large international NGDOs. To identify these publications, a systematic search was carried out of the websites of CONCORD, the European advocacy association of NGDOs, and its 25 large transnational members. Actual NGDO participation in the EUTF was then examined using regression analysis on EUTF project-level data, taken from the European Commission’s website (European Commission Citation2020b), to identify the factors that may have impacted the likelihood of NGDOs taking part in EUTF-funded projects between 2015 and 2020.

The main finding is that NGDOs have been highly critical of the EUTF’s goals, and have denounced it as a ‘political tool’, which promises a quick fix to protracted problems requiring long-term engagement. NGDOs have also argued that the EUTF has the potential to cause more harm than good. Despite these misgivings, however, many large NGDOs have been involved in implementing projects funded by the EUTF. The regression analysis shows that NGDOs are most likely to be involved in implementing projects in the thematic area of ‘strengthening resilience’, focusing on improving livelihoods and strengthening the ability of communities to react to external shocks. This is mostly reconcilable with NGDOs’ moral motivations. Furthermore, they have generally stayed away from the EUTF’s more controversial ‘migration management’ projects, which often include support for border control and surveillance in recipient countries.

In the EUTF case, NGDOs have therefore clearly signalled their moral motivations through advocacy, and have aimed to participate only in projects that are aligned with these motivations. These findings imply that in areas where NGDOs are vocal in their advocacy, they will have reputational incentives to be seen as practising what they preach, and align their funding strategies accordingly. Much of the recent literature on the broader world of civil society organisations (see eg Mosley Citation2012) has tended to emphasise the opposite in terms of the adverse effects funding concerns have on advocacy. While the article does not dispute this line of reasoning, it argues that in high-profile situations, such as the issue of refugees and migration in Europe, NGDOs may find it more beneficial not to risk harming their reputations but rather to adhere to their moral visions. Although it is possible to argue that given the NGDO community’s vocal rejection of the EUTF, total abstention from it would have been the truly moral answer, this is not realistic when NGDO funding concerns are taken into account. Rather, NGDOs will put mitigating strategies in place to at least be seen as (mostly) practising what they preach.

The following section provides theoretical considerations on the motivations of NGDOs, which is followed by a presentation of the EUTF. The subsequent section discusses the methodology used to collect NGDO publications on the EUTF, and analyses these to identify NGDO reactions. This is followed by a section detailing the regression analyses on the determinants of NGDO participation in implementing EUTF-funded projects. The final section offers brief concluding remarks.

What drives NGDO behaviour?

NGDOs are non-governmental organisations working in the field of international development. They raise funds primarily in Northern countries from governments, multilateral agencies and individual donations, and channel these towards funding and implementing development or humanitarian actions in countries of the Global South. These actions generally focus on easing human suffering, reducing poverty, improving social justice and empowering the poor (Ferreira, Carvalho, and Teixeira Citation2017). NGDOs also carry out advocacy towards governments and international organisations, and raise awareness on the issues facing the global poor. The work of NGDOs therefore encompasses both service delivery and advocacy, and is transnational in nature, setting them apart from most other NGOs.

The literature on the motivations of NGDOs has traditionally emphasised the moral driving forces behind their actions (Keck and Sikkink Citation1998; West Citation2001; De Jong Citation2011). Most NGDOs were founded on moral vision to alleviate the suffering of the poor, protect their rights and empower them. People who take jobs at NGDOs are also driven by similar visions and altruistic motivations, working ‘out of a sense of duty to create social justice, unmotivated by profit or politics’ (De Jong Citation2011, 21). Their dedication to supporting the poor means that they are willing to accept lower salaries, or even work on a voluntary basis, at least according to popular (idealised) conceptualisations (Fechter Citation2014). This understanding of NGDOs, focusing on their moral motivations, paints them as ‘knights in shining armour’ (Bloodgood Citation2011, 93), who sacrifice themselves to champion the interests of the poor in the Global South. These moral incentives imply that NGDOs will advocate for policies that are beneficial for the poor, even if they hurt the interests of people or certain groups in the North, or even their own interests. In fact, NGDOs may promote policies that have little public support in the North, but would help the poor in the South (Szent-Iványi and Timofejevs Citation2021). The aid projects they implement aim to use scarce resources to achieve maximum impact on the welfare of the poor (Unerman and O’Dwyer Citation2010), focusing on sectors where they can make meaningful differences, such as healthcare, education or sanitation, or working to support specific marginalised groups like women or children. Their moral dedication allows them to work more flexibly and at lower cost than other (governmental) aid agencies (Werker and Ahmed Citation2008).

However, academics have become increasingly pessimistic about this ‘saintly’ view of NGDOs (Brass Citation2012; Brass et al. Citation2018). To achieve their moral vision, NGDOs need to ensure their own survival through access to resources (Bloodgood Citation2011). Larger NGDOs are highly professionalised organisations employing thousands of people around the world. To attract professionals and to implement pro-poor development projects, NGDOs need to have sustained access to external funding, including grassroots donations, grants and implementation contracts from various governments and other large donors. Gaining implementation contracts and grants is a key organisational incentive faced by many NGDOs (Cooley and Ron Citation2002; Mosley Citation2012). Dependency on certain sources of funding, however, may alter the behaviour of NGDOs (Molenaers, Jacobs, and Dellepiane Citation2014). As stated by Amagoh (Citation2015, 230), the ‘inherent danger for NGOs who depend on specific donors lies in the fact that the NGOs may become more like the bodies from which they attract funding, rather than the societies whose interests they intend to represent’ (see also Sakue-Collins Citation2021 for a more radical critique). NGDOs’ advocacy may move away from the interests of the poor and focus on ensuring their own future access to funding (Mosley Citation2012). For example, they may be less keen to call for untying aid from donor country procurement (Carbone Citation2006), or – given how donors tend to fund organisations that have similar priorities to their own (Sanchez Salgado Citation2014) – they may align their advocacy with donor priorities. The project work of NGDOs may also change: groups dependent on government funding are more risk averse, follow donor priorities (Fruttero and Gauri Citation2005; Keck Citation2015; but see also Davis Citation2019 for a contrary argument) and have incentives to cover up failure (Cooley and Ron Citation2002, 24), and their ties with local beneficiaries also weaken (Banks, Hulme, and Edwards Citation2015).

The moral and organisational/financial incentives that drive NGDOs are therefore at odds with each other, and NGDOs need to make regular decisions on which ones they allow to prevail. An important consideration that influences these decisions is the NGDO’s reputation, or the need to ‘look good’ (Jones Citation2017; Mitchell and Stroup Citation2017). A ‘good’ reputation will mean different things to different audiences (Gourevitch and Lake Citation2012): official donors (ie governments and multilateral organisations) will be more willing to work with NGDOs that have a track record of effective and efficient project implementation; policymakers and journalists are more likely to engage with NGDOs that provide accurate and reliable information about specific issues (McPherson Citation2016); and grassroots donors usually provide donations for moral reasons, to organisations they see as credibly championing these in practice. Acting in a moral and virtuous manner is therefore an important source of a good reputation, and thus also funding, but does not guarantee it (Gourevitch and Lake Citation2012). Actors providing funding or engaging with NGDOs in other ways are aware of the organisational incentives these groups face and the potential these create for moral lapses, especially in light of highly publicised scandals associated with NGDOs (Gibelman and Gelman Citation2004; Scurlock, Dolsak, and Prakash Citation2020). It is also difficult, if not impossible, to verify how NGDOs behave in practice, especially ‘in the field’ (Edwards and Hulme Citation1996), and whether they actually live up to their moral missions. In most cases, the only source of information on NGDO behaviour is what the organisations themselves report, and external verification can be costly.

This means that NGDOs have to actively build their reputation and send signals about their behaviour to their constituencies (Amagoh Citation2015; Keating and Thrandardottir Citation2017). Gourevitch and Lake (Citation2012), as well as Amagoh (Citation2015), provide detailed reviews of the measures NGDOs can take to build their reputations. For the purposes of understanding how NGDOs engage with the EUTF, two points stand out from their analyses. First, NGDOs need to ensure that at least their most readily observable actions are consistent with their moral missions. Citizens of rich countries are most likely to hear about NGDOs through their advocacy or fundraising campaigns (Davis Citation2019), and not their actual development work. In their advocacy, NGDOs take clear positions on various development issues, and communicate these visibly through their websites, social media and press releases and indirectly through the mainstream media. Their criticism of government policies needs to be well argued and underpinned by research to be credible, and these arguments need to be consistently aligned with their moral positions on improving the livelihoods and rights of the Southern poor. Second, NGDOs need to be careful regarding who they accept funding from. As discussed, relying too much on official donors has its drawbacks in terms of the changes it provokes in NGDO behaviour. However, some donors can be more problematic than others, and accepting funding from certain governments or corporations whose agendas differ significantly from theirs can compromise the reputation of NGDOs (McGann and Johnstone Citation2006). Accepting such donations will raise questions about neutrality: stakeholders may harbour suspicions on whether the funding came with strings attached, or whether NGDOs will change their behaviour on their own accord to align with funder priorities. However, the finances of NGDOs are usually less visible to the public than their advocacy. While transparency in funding sources is necessary for improving reputation and trust towards donors (Amagoh Citation2015), groups can often ‘be creative’ with exactly how much information they publish.

These two points mean that in case of a new official funding instrument that proclaims goals that are at odds with NGDO moral missions, such as the EUTF, NGDOs need to weigh how they approach it in terms of advocacy, and what reputational harm bidding for its funding may cause. In terms of advocacy, a controversial instrument provides NGDOs with an opportunity to send signals to their constituents, highlighting and juxtaposing their moral position with that of the funder. If the new aid instrument focuses on high-profile issues with large public salience, such as migration in Europe, it will give NGDOs a low-cost opportunity to signal their virtue to those who share their values. However, a new funding instrument also presents itself as an opportunity for NGDOs to increase their funding, making engagement tempting. NGDOs thus need to consider the potential reputational harm that would come from applying for funding, and compare that to the potential financial gains. They may find ways to mitigate or decrease the risk of reputational harm. As mentioned, funding sources are less visible than advocacy, and despite the need for transparency regarding funding, some forms may ‘fly under the radar’. Few people pore over the minute details of NGDO financial reports, and the exact source of funding for a specific project can be hidden to some degree. Alternatively, NGDOs can ‘whitewash’ their participation by arguing that they are attempting to change the priorities of the funder ‘from within’, or that although the instrument itself is flawed, the project they are engaged in uses the money to ‘do good’.

Summing up these theoretical considerations, NGDOs are expected to engage with the EUTF by (1) visibly signalling their moral concerns through their advocacy; and, (2) if they do take part in implementing projects, using various strategies to minimise the reputational harm this participation may cause.

The EU Emergency Trust Fund for Africa

The European Union Emergency Trust Fund for Stability and Addressing Root Causes of Irregular Migration and Displaced Persons in Africa was launched at the Valletta Summit in November 2015, following the European refugee crisis of the spring and summer of 2015. The goal of the fund was to ‘deliver an integrated and coordinated response to the diverse causes of instability, irregular migration and forced displacement’, by delivering ‘concrete results in a rapid and effective manner’ (European Commission Citationn.d.a). By addressing the root causes of migration and displacement, and supporting ‘better migration management’ in sending countries, the fund was envisioned to contribute to the reduction of irregular migrant flows to Europe, in addition to other EU efforts, including existing maritime missions (Cusumano Citation2019), a similar Trust Fund in response to the Syrian crisis, a deal with Turkey to tighten its border controls in exchange for €6 billion in aid, and later the New Partnership Framework, which aimed to create a set of incentives for developing countries to curb outflows of people (European Commission Citation2016a). The EUTF was planned to complement the EU’s existing financial instruments focused on funding development in Africa, most notably the European Development Fund (EDF), to allow for greater flexibility. While the spending of the EDF’s resources happened through an often ‘sluggish’ programming process, the EUTF was designed to react rapidly to shifting realities (Castillejo Citation2016, 19). The creation of a separate aid instrument for tackling migration also allowed the EU to send political signals about its willingness to act in the wake of refugee crisis. From an original amount of almost €1.9 billion at its launch (European Commission Citation2016a, 4), the value of the fund grew to €4.85 billion by the end of 2020 (European Commission Citation2021, 7). Around 88% of these resources were reallocations from the EU’s various existing development budgets, most importantly the 11th EDF. The remaining 12% was made up of additional contributions from member states, as well as Norway and Switzerland (European Commission Citation2020a, 41–44). The fact that these additional contributions remained relatively modest showed that the early expectations around the EUTF’s ability to leverage external resources were highly optimistic.

The EUTF focuses on three broad geographic regions – North Africa, the Horn of Africa, and the Sahel and Lake Chad – including a total of 26 partner countries. There are also four thematic priorities:

Greater economic and employment opportunities, aiming to support skills development and job creation, especially for youth and vulnerable groups;

Strengthening resilience, focused on supporting individuals and communities in withstanding and adapting to shocks, by strengthening food security and social protection schemes;

Improved migration management, under which the EUTF supports government migration policies, especially the implementation of regulatory frameworks, and strengthening institutions and border controls;

Improved governance and conflict prevention, aimed at improving the quality of governance, including strengthening the rule of law and promoting conflict prevention.

The distribution of the EUTF’s committed resources along the three geographic regions and the four thematic priorities is shown in , which reveals an interesting pattern: while the four thematic areas are more or less balanced in terms of spending, improved migration management seems more important than the other three. In fact, it seems to be the EUTF’s only priority area in North Africa, although it makes up only around 8% of the allocations to the Horn of Africa.

Table 1. Distribution of the EUTF’s committed resources along geographic and thematic priorities, 2020.

The EUTF does not follow an ex ante agreed programme of action, but works rather flexibly. Actions funded by the instrument are identified through a ‘bottom-up’ approach, where the EU’s delegations, ‘consulting widely to ensure strong partnerships with local stakeholders’ (European Commission Citationn.d.b), initiate ideas, which are then formulated into proposals by the European Commission’s EUTF team in Brussels. These are submitted for approval by the EUTF’s Operational Committee, which is composed of representatives of the European Commission, the European External Action Service and contributing states. All states that have contributed at least €3 million have one vote, although the aim is to operate the EUTF by consensus (European Union Citation2015). Implementation is carried out by a wide range of partners, including member state development agencies, United Nations organisations, other international organisations, partner country authorities and NGDOs, as well as different consortia of these actors (European Commission Citationn.d.b).

While the EUTF’s flexibility and ability to react rapidly are welcome, they also raise an important dilemma, as does the Trust Fund’s goal of managing migration. The EU has been one of the main proponents of the global aid effectiveness agenda (Carbone Citation2013; Kim and Lightfoot Citation2017), even if its practice has not always lived up to its ambitions (Delputte and Orbie Citation2014). The EUTF’s operations undermine key aid effectiveness principles, especially recipient ownership. Local consultations are cut short, and aid seems to be driven much more by EU priorities than recipient needs (Castillejo Citation2016, 20). Sidestepping local actors, who are closest to the issues and have the greatest stake in finding solutions, will not help the EUTF find innovative solutions to the issues caused by migration (Castillejo Citation2016, 21). The EU has further undermined aid effectiveness principles by making aid conditional on migration management cooperation through the New Partnership Framework. All of these issues clearly raise further dilemmas for NGDOs, potentially making the moral case against the EUTF even stronger.

Signalling moral concerns: NGDO advocacy on the EUTF

To map the NGDO community’s reactions to the EUTF, a systematic search was performed to find NGDO press releases, reports and any other publications that deal with the topic. Focus was placed on the largest NGDOs traditionally most active in EU-level advocacy, starting with CONCORD, the pan-European advocacy association of NGDOs. CONCORD was established in 2003 to serve as the main interlocutor and advocacy platform between European NGDOs and the EU institutions, with the goal of influencing EU development policy. Having a single organisation responsible for advocacy towards the EU allows NGDOs to speak with one voice, and thus represent sector-wide priorities and interests more clearly. It also provides these organisations with a forum to exchange expertise and learn from each other. CONCORD has a permanent secretariat in Brussels, and publishes a large number of advocacy-focused publications. CONCORD’s members include member-state-level national advocacy umbrella groups, as well as 25 transnational NGDO networks, the latter covering all the large, well-known organisations, such as Care, Caritas, Oxfam, Save the Children and World Vision. According to its website, CONCORD indirectly represents more than 2600 NGDOs from across Europe, mainly through its national umbrella group members. The search focused on the CONCORD website, as well as the main international websites of its 25 transnational network members. The national umbrella group members of CONCORD and the national-level websites of the transnational NGDOs were excluded, as their advocacy is mainly directed towards their own governments and not the EU. To find texts on the EUTF, the general search function on each organisation’s website was used, as well as the search functions in their publication repositories, with the keywords ‘Africa’, ‘migration’ or ‘trust fund’. The search was restricted to documents published between 2015 and 2020, and to ones that dealt explicitly with the EUTF, as opposed to ones containing criticism of the EU’s handling of the development/migration nexus in general.

This search strategy resulted in more than 500 hits, showing that issues related to migration have figured highly on NGDO agendas. However, after refining the results and excluding duplicates and documents that did not mention the EUTF explicitly, only 30 remained, implying that NGDOs were much more likely to speak on a general level about migration, and not go into specific details. Not surprisingly, given its nature as purely an advocacy association, CONCORD has been the most active in voicing NGDO criticisms about the EUTF. Among individual NGDOs, Oxfam stood out as being the most prolific in criticising the fund. Caritas, Islamic Relief and Solidar have also discussed the EUTF in their advocacy, although it did not receive much emphasis. Specific mentions of the EUTF were conspicuously absent from the communications of all the other large NGDOs. Four of the documents were detailed and lengthy reports focusing specifically on the EUTF (CONCORD Citation2015, Citation2018; Oxfam Citation2017, Citation2020a), while the rest were relatively short briefings and press releases. All 30 documents were read in depth to identify key themes, using a qualitative approach.

The analysis of the documents reveals that the EU’s usage of aid to manage migration through the EUTF has received significant NGDO criticism. The key NGDO narrative focused on how the EUTF is aimed at serving the self-interests of the EU, and is detrimental for the poor. CONCORD (Citation2015) argued that ‘the emphasis on border controls and security undermines the achievement of the EU’s global development objectives’, especially poverty reduction and the respect of human rights. The EUTF was seen as a tool to stem migratory flows to Europe with ‘quick fix’ projects, which is at odds with the goals of EU development assistance outlined in the Lisbon Treaty (CONCORD Citation2018). Oxfam (Citation2016) argued that the EUTF blurred the lines between ‘development work – which is aimed at lifting people out of poverty – and security projects meant to strengthen border control and stop people on the move’. The EUTF is simply a ‘political tool that sends a political signal to the European constituency’, with actual development objectives being sidelined (CONCORD Citation2018). NGDOs claimed that the EU has gone so far in pursuing its own interests that it is even providing resources to countries known for systematic violations of human rights, all in the name of controlling migration (Oxfam Citation2016; Caritas Citation2016). These criticisms were levelled not only against the security-focused projects under the EUTF, but also towards the broader conditionalities attached to EU funding in terms of recipients adapting stricter border controls and agreeing to readmit migrants, which, in the views of NGDOs, represent the narrow, short-term political self-interests of the EU (Caritas Citation2017; CONCORD Citation2015; Oxfam Citation2015). Making security and border cooperation a prerequisite for EU funding was formalised in the EU’s New Partnership Framework with third countries, launched in 2016, which also attracted heavy criticism from NGDOs, including a joint statement to the European Council signed by 109 organisations (Joint NGO Statement Citation2016). This statement called on the EU to develop safe and open channels for migration, abandon the usage of migration-related conditions for receiving aid, and stop the readmission of people to countries that violate fundamental rights.

Beyond this main narrative calling attention to the selfish interests behind the EUTF, NGDOs also criticised it on a number of practical accounts, including resources, effectiveness and harm caused. CONCORD called the Valetta Summit a ‘missed opportunity’, in terms of the resources committed to the EUTF; the less than €2 billion agreed at the time was portrayed as insufficient to address the root causes of forced displacement and migration, especially when spread across 26 countries and compared to the €6 billion granted to Turkey alone (van Dillen Citation2015; Wirsching and van Dillen Citation2016). Many of these resources were not additional to existing EU aid, as they were ‘re-labelled’ from the EDF and other EU aid instruments (Wirsching and van Dillen Citation2016). The effectiveness of the projects from the EUTF was also questioned. While the fund was planned as a flexible instrument, NGDOs questioned just how recipient country ownership and alignment with recipient priorities could be ensured without proper programming processes. Most projects also seemed to violate the principle of channelling aid through recipient country systems (CONCORD Citation2016). Projects were designed in Brussels and member state capitals, with minimal consultation with local actors, and thus reflecting EU priorities (CONCORD Citation2018). NGDOs have also highlighted instances where funding from the EUTF has actually caused harm: for example, supporting the Libyan authorities has fuelled ‘human trafficking and the arbitrary detention of refugees in horrific and dangerous conditions’ (Oxfam Citation2020b; see also Islamic Relief Citation2018). In Niger, the EU’s efforts to pressure the country into changing laws on policies related to immigration has undermined not only the trust of communities in their leaders, but also their livelihoods (CONCORD Citation2018; Oxfam Citation2020b).

More recent NGDO analysis of the EUTF suggests some warming to the fund, acknowledging that it ‘provides much needed support to displaced people and creates opportunities for economic development’ (Oxfam Citation2017), or how its transparency and public communication have improved (Oxfam Citation2020a). However, NGDOs still viewed the fundamental nature of the EUTF as unchanged, and criticism of its implementation reinforced the earlier narratives on the fund’s generally flawed goal of reducing the flows of people to Europe. A detailed analysis by Oxfam (Citation2020a) of the projects implemented under the EUTF showed that more than a quarter of the fund’s resources were spent on migration management projects with little development impacts, and the more traditional development projects were often used as leverage to push countries to agree to return and readmission. Only 1.5% of the EUTF’s resources have been spent on developing regular migration schemes between the EU and Africa.

All this criticism by NGDOs is in line with their moral motivations to stand up for people in poor countries, support schemes that would increase their welfare and contest any efforts to reduce their rights or harm their livelihoods. In their criticism of the EUTF, NGDOs have tried to create a positive narrative of migration, focusing on the development benefits it brings to mobile persons, receiving countries and also sending countries through remittances and other channels. NGDOs regularly invoked a rights-based approach, and have argued that making a clear distinction between mobility and forced displacement is essential so that the fundamental rights of the latter group, guaranteed in international law, can be protected. There are regular references to the core values of the EU, and how the EU needs to stop undermining these. ‘Development aid is meant to fight poverty, inequality, and the growing climate crisis and it should not be politicised’ (Oxfam Citation2020b). While not all NGDOs engaged in direct advocacy relating to the EUTF, it is clear that through CONCORD or the 2016 Joint Statement, the NGDO community as a whole made its position visible, and this position aligns with the moral motivations that drive NGDOs.

NGDO participation in EUTF projects

Given the harshness of NGDO criticism towards the EUTF’s goals and operations, one might expect them to be highly cautious in engaging with it in terms of implementing actions. This is seemingly not the case, however: according to the EUTF’s website, around 18% of the fund’s contracted amount is directly implemented by NGDOs (European Commission Citationn.d.c),Footnote1 which is actually higher than the share of all EU aid channelled through these organisations (10.5% in 2018; OECD.stat Citation2020; see also Keijzer and Bossuyt Citation2020 for a broader discussion on the role of NGDOs in EU development assistance). Most of the large transnational NGDOs examined in the previous section have in fact left their options open in terms of participating in EUTF implementation: as discussed, most of the contestation of the EUTF has been through CONCORD, which is a purely advocacy body, thus allowing individual NGDOs to keep themselves more detached from criticising the EU’s actions. Individual NGDOs have rarely criticised the EUTF openly, and have generally only contested the EU’s attempts to use aid to manage migration, refraining from focusing specifically on the EUTF.

Can this participation be reconciled with the moral positions of NGDOs? Visibly denouncing the EUTF signals their moral virtues; however, taking part in its actual implementation may carry reputational risks. Large NGDOs may see these risks as small, as being involved in a small number of EUTF projects may not be too visible among the myriad projects that these organisations undertake. In NGDO annual reports, EUTF projects can be bundled together with funding from other, non-controversial EU aid instruments, under the broad heading of ‘EU funding’. Oxfam, however, actually draws attention to the fact that it participates in EUTF projects in its publications that criticise the fund (Oxfam Citation2020a, 10). It therefore makes sense to analyse the determinants of NGDO participation in EUTF projects, focusing on the kinds of projects NGDOs implement, and whether these are compatible with their moral standpoints.

To analyse this, the project database on the EUTF’s website was used as the source of data (European Commission Citation2020b). The data set was downloaded in August 2020, and included 234 actions. The level of detail varied among actions: some had very detailed documentation, including financial details and data on participants and activities within the action, while others hardly included more than a short description. Out of the 234 actions, reasonably full details could be found for 206. The largest share of these actions were implemented by member state development agencies or United Nations agencies, but 34 included NGDOs as the main implementer, or one of the implementers. These 34 projects involved a total of 31 NGDOs. Details of these NGDOs are given in , collected from their websites and 2018/2019 annual reports. The table shows that these NGDOs are predominantly large organisations (their median income was €177 million) from Northern/developed countries. Most of them are heavily dependent on funding from official donors, and although exact data is not available for many, they received not insignificant parts of their income from the EU. The financial reports of the 31 NGDOs also confirm that many indeed ‘hide’ EUTF funding: most commonly these reports only provide very basic breakdowns of EU funding, only differentiating between humanitarian and development funds.

Table 2. NGDOs involved in EUTF projects, 2015–2020.

To examine the determinants of NGDO participation in the EUTF further, a probit regression was performed on the project data set. The dependent variable was a binary variable equal to one if an NGDO is involved in the implementation of the action (regardless of their exact role in implementation, which is often difficult to determine from the data set). Based on the theoretical insights from the previous sections, NGDOs are more likely to participate in EUTF project implementation for financial reasons. In the regression model, this is proxied by the total budget of the project (in euros, variable ‘budget’). A further theoretical finding is that NGDOs are more likely to take part in projects that align with their moral motivations. These are proxied by a set of dummies coding the thematic area of the project. The ‘Other’ category represents the baseline (these are actions aimed at research and evaluation, and not attributed by the EU to either theme), with dummies for greater economic and employment opportunities (econ_emp), strengthening resilience (str_res), improved migration management (migr_man) and improved governance and conflict prevention (impr_gov). The expectation from the theory is that NGDOs will be less likely to participate in migration management projects, as they have strongly contested these. Taking part in projects explicitly labelled as aiming to manage migration would contradict NGDO rhetoric and pose a visible reputational risk. NGDO participation is expected to be positively correlated with projects aimed at supporting livelihoods and reducing poverty, under the greater economic and employment opportunities or strengthening resilience themes. The latter thematic area especially includes projects that fit under ‘traditional’ development cooperation, and where NGDOs may have some sort of comparative advantage, given their ability to work with vulnerable communities. Further variables in the model include a set of dummies coding the region in which the action is implemented: Sahel and Lake Chad represent the baseline, with dummies for North Africa (n_afr) and the Horn of Africa (horn_afr); and a set of dummies to code the year in which the project was implemented, with 2015 serving as the baseline.Footnote2 Summary statistics on these variables are provided in .

Table 3. Summary statistics.

These variables understandably do not cover all the potential determinants of NGDO participation in the EUTF, but there is little further data that could be extracted from the data set in a comparable manner. Variables relating to the NGDOs themselves, such as their income or the share of it coming from official donors, could also be plausible explanatory factors. However, since NGDOs are only implementers in 34 out of the 206 actions, these variables would not make sense for the majority of the observations, which have member state aid agencies, partner country authorities or international organisations as implementers.

Two versions of the model were run to ensure some degree of robustness for the findings; however, the limited set of independent variables placed restrictions on how many versions were actually possible. The results are presented in . Model 1 treats the entire data set as a single cross section without year dummies, and thus does not account for potential changes in NGDO participation over time. The dummy variable for the managing migration theme is significant (although only at the 10% level) and with a negative sign, implying that NGDOs are indeed less likely to take part in projects aimed at managing migration, as expected. Strengthening resilience is strongly significant, with the expected positive sign. The dummy for projects in the Horn of Africa is significant too. None of the other variables are significant: NGDO participation is not influenced by the size of the project, nor are NGDOs more or less likely to participate in projects in North Africa than in the Sahel, or in those aimed at creating economic opportunities or improving governance. Model 1 was also estimated with the budget variable entered in logarithm, but the results are practically unchanged (this is not reported in , but available from the author on request).

Table 4. Probit regression results on the determinants of NGDO participation in EUTF projects.

Based on comments from Oxfam (Citation2020a), the workings of the EUTF have evolved over time, and thus Model 2 accounts for this by including year dummies. These are not significant individually, and an F-test shows that they are not significant jointly either. This implies that there has actually been little change in NGDOs’ levels of engagement with the EUTF over time. Adding the year dummies changes little in the results. As a further robustness test, interactions were added between all year and region dummies, replacing these dummies. The results are not reported in detail; however, the migration management and strengthening resilience variables remain significant (p = 0.008 and p < 0.001, respectively). Among the interactions, only the ones for the Horn of Africa with the years 2015, 2016, 2018 and 2020 are significant (with p values ranging between .06 and .007). No other variables are significant, meaning these results are in line with the previous ones.

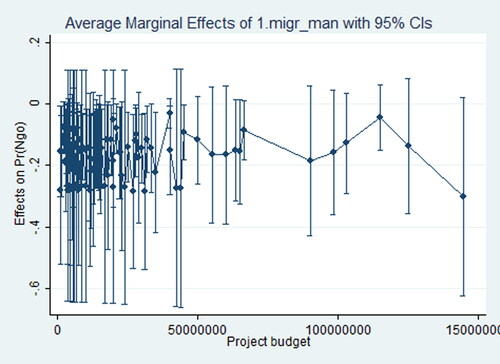

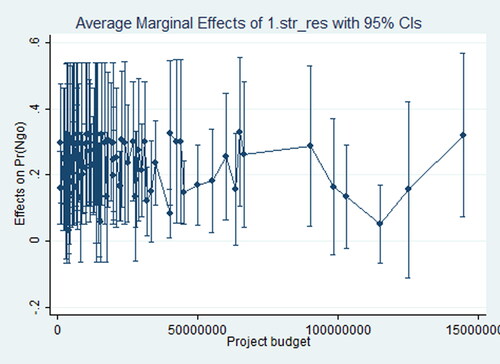

To get a better picture of what impact the themes of the project – especially migration management and strengthening resilience – have on NGDO participation, their average marginal effects on the dependent variable were also calculated, based on Model 1 (). According to this, on average across all observations, NGDOs are 15.8% less likely to participate in migration management projects, while they are 21.8% more likely to be included in projects aimed at strengthening resilience. and plot the marginal effects of these two variables across the budgets of each action.

Figure 1. Marginal effects of migration management across action budgets.

CIs: confidence intervals. Source: Author’s elaboration.

Figure 2. Marginal effects of strengthening resilience across action budgets.

CIs: confidence intervals. Source: Author’s elaboration.

Table 5. Average marginal effects of migration management and strengthening resillience on the probability of NGDO participation in EUTF projects.

The results of this exercise show that the actions of NGDOs are mostly consistent with their rhetoric. While expecting them to fully boycott the EUTF is unrealistic, they are not drawn to larger EUTF projects and have been highly unlikely to engage with ones aimed at managing migration, which are most at odds with the normative positions they have taken in their advocacy. Indeed, NGDOs are most likely to take part in implementing EUTF projects that have more traditional development cooperation objectives in terms of improving the lives and the rights of individuals and communities in Africa, grouped by the EUTF under the strengthening resilience theme.

A potential alternative explanation is that NGDOs simply avoid migration management projects because they do not have expertise in this area. Examining the projects under the migration management theme, there are clearly ones where it would be difficult to conceive an NGDO as an implementing partner. These focus on strengthening government capacities in surveillance, tackling irregular border crossings, building border infrastructure, or managing data on migration. These are areas where most NGDOs have little to no expertise. However, there are also a number of interventions under the theme in which NGDOs could conceivably take part. provides a breakdown of the actions under the improved migration management theme, along the main activities in these actions. As shown in the table, border management and law enforcement projects make up 18% of the total value of actions under the theme, while projects aimed at protecting refugees account for around 25%. These refugee protection projects include elements such as providing basic services (eg medical assistance and sanitation), protecting vulnerable groups like women and children from exploitation and human trafficking, supporting migrants and refugees with legal assistance, providing shelter and generally improving the conditions under which migrants are housed, or sensitising law enforcement and other government officials on the rights of migrants. NGDOs that take part in migration management projects only do so under these humanitarian refugee protection projects, which fit with their moral missions. For example, Save the Children is part of a project aimed at protecting migrant children from human trafficking in Mauritania, while the Danish Refugee Council is engaged in one focusing on providing basic services to refugees and migrants in Libya (European Commission Citationn.d.d).

Table 6. Breakdown of Improved migration management projects according to their main activities.

NGDOs do not participate in projects aimed at promoting and enhancing return and readmission, nor (with one exception) in information campaigns aimed at deterring would-be migrants, although they conceivably could. These projects generally aim to incentivise migrants to return to their communities through offering training, creating better local livelihood conditions and employment opportunities, as well as running information campaigns about these. However, the philosophy behind these projects would be more difficult to square with the moral positions of NGDOs, which argue that refugees should not be forced to return, or lured into doing so. This supports the argument that NGDOs generally stayed away from migration management projects not because they could not do what is required in these projects, but because they did not want to associate themselves with the more controversial aspects of managing migration.

Conclusions

This article examined how NGDOs balance their moral and organisational motivations, using as a case study the European Union Emergency Trust Fund for Africa. NGDOs constantly have to negotiate choices between their moral and organisational incentives, and the literature has often argued that the latter prevails in many cases. However, NGDOs need to maintain their reputation as virtuous actors towards their stakeholders, including official and grassroots donors, and to do this, they need to send visible signals about their positions on specific topics. In the case of the EUTF, the NGDO community engaged in highly critical advocacy regarding its underlying goals and implementation, but this did not stop many of them from engaging with the fund as project implementers. However, NGDOs generally did not publicise this engagement, and have been careful to only take part in EUTF projects that were aligned with their rhetoric, avoiding the ones focusing on implementing the more controversial aspects of the EU’s migration management agenda. While NGDOs did not abstain from the EUTF, they made efforts to ensure that they are seen to mostly practise what they preach, and did not allow their organisational incentives to fully dominate their approach. These findings caution against one-sided conceptualisations of NGDOs as altruistic or egoistic actors. Rather, they balance these motivations in complex ways, and implement strategies that mitigate the impacts of specific actions on their reputations as morally driven actors.

The analysis in this article has mostly treated the ‘NGDO community’ as a relatively homogeneous entity, which was a necessary simplification required to provide an overarching picture. This is not, however, meant to deny that there are significant differences even between the large, Northern NGDOs which engage with the EUTF. Not all of these NGDOs may be acting on the basis of the same principles when making decisions on which funders to engage with and how, and they may face different internal dynamics and constraints. Exploring these using qualitative case studies of individual NGDOs could be fruitful avenue for future research.

ctwq_a_1964358_sm0883.dta

Download Stata File (75.2 KB)ctwq_a_1964358_sm0879.do

Download Stata Do-File Editor File (1.1 KB)Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Tamás Barczikay, Sarah Delputte, Nadia Molenaers, Beáta Paragi, Davide Vampa and three anonymous reviewers for comments on earlier versions. Any remaining errors are my own.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Balazs Szent-Ivanyi

Balazs Szent-Ivanyi is Senior Lecturer in politics and international relations at Aston University, Birmingham, UK, and also holds an honorary Associate Professor position at Corvinus University, Budapest, Hungary. His research focuses on the political economy of foreign aid, with an emphasis on how foreign aid policy decisions are made in donor countries. His most recent research has been published in journals such as Development Policy Review, International Relations, the European Journal of Development Research, International Migration, and Democratization.

Notes

1 This data only includes projects where NGDOs are the main implementers. NGDOs may also be present as indirect subcontractors through contracts signed with member state aid agencies or international organisations acting as the main implementers. The data, however, is not granular enough to gauge this level of participation.

2 The data set and the Stata .do file can be found on the journal’s website (Supplementary material).

Bibliography

- Amagoh, F. 2015. “Improving the Credibility and Effectiveness of Non-Governmental Organizations.” Progress in Development Studies 15 (3): 221–239. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1464993415578979.

- Banks, N., D. Hulme, and M. Edwards. 2015. “NGOs, States, and Donors Revisited: Still Too Close for Comfort?” World Development 66: 707–718. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.09.028.

- Bloodgood, E. 2011. “The Interest Group Analogy: International Non-Governmental Advocacy Organisations in International Politics.” Review of International Studies 37 (1): 93–120. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0260210510001051.

- Brass, J. 2012. “Why Do NGOs Go Where They Go? Evidence from Kenya.” World Development 40 (2): 387–401. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2011.07.017.

- Brass, J., W. Longhofer, R. Robinson, and A. Schnable. 2018. “NGOs and International Development: A Review of Thirty-Five Years of Scholarship.” World Development 112: 136–149. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.07.016.

- Carbone, M. 2006. “European NGOs in EU Development Policy: Between Frustration and Resistance.” In New Pathways in International Development. Gender and Civil Society in EU Policy, edited by M. Lister and M. Carbone, 197–210. Aldershot: Ashgate.

- Carbone, M. 2013. “Between EU Actorness and Aid Effectiveness: The Logics of EU Aid to Sub-Saharan Africa.” International Relations 27 (3): 341–355. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0047117813497300.

- Caritas. 2016. “The EU Agenda behind the Migration Partnership Framework.” https://www.caritas.eu/the-eu-agenda-behind-the-migration-partnership-framework/

- Caritas. 2017. “Development Aid Cannot Serve as Migration Control.” https://www.caritas.eu/development-aid-cannot-serve-the-purpose-of-migration-control/

- Castillejo, C. 2016. “The European Union Trust Fund for Africa: A Glimpse of the Future for EU Development Cooperation.” DIE Discussion Paper 22/2016.

- CONCORD. 2015. “Migration and Development.” https://concordeurope.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/SpotlightReport_Migration_2015.pdf

- CONCORD. 2016. “AidWatch report 2016.” https://concordeurope.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/CONCORD_AidWatch_Report_2016_web.pdf

- CONCORD. 2018. “Partnership or Conditionality? Monitoring the Migration Compacts and EU Trust Fund for Africa.” https://concordeurope.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/CONCORD_EUTrustFundReport_2018_online.pdf

- Cooley, A., and R. James. 2002. “The NGO Scramble: Organizational Insecurity and the Political Economy of Transnational Action.” International Security 27 (1): 5–39.

- Cusumano, E. 2019. “Migrant Rescue as Organized Hypocrisy: EU Maritime Missions Offshore Libya between Humanitarianism and Border Control.” Cooperation and Conflict 54 (1): 3–24. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0010836718780175.

- Davis, J.-M. 2019. “Real “Non-Governmental” Aid and Poverty: Comparing Privately and Publicly Financed NGOs in Canada.” Canadian Journal of Development Studies / Revue Canadienne D’études du Développement 40 (3): 369–386. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02255189.2019.1556623.

- De Jong, S. 2011. “False Binaries: Altruism and Selfishness in NGO Work.” In Inside the Everyday Lives of Development Workers: The Challenges and Futures of Aidland, edited by A.-M. Fechter and H. Hindmann, 21–40. Boulder, Colorado: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

- Delputte, S., and J. Orbie. 2014. “The EU and Donor Coordination on the Ground: Perspectives from Tanzania and Zambia.” The European Journal of Development Research 26 (5): 676–691. doi:https://doi.org/10.1057/ejdr.2014.11.

- Edwards, M., and D. Hulme. 1996. “Too Close for Comfort? The Impact of Official Aid on Nongovernmental Organizations.” World Development 24 (6): 961–973. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0305-750X(96)00019-8.

- European Commission. n.d.a. “EU Emergency Trust Fund for Africa – About.” https://ec.europa.eu/trustfundforafrica/content/about_en

- European Commission. n.d.b. “EU Emergency Trust Fund for Africa – How Do We Work.” https://ec.europa.eu/trustfundforafrica/content/how-does-it-work_en

- European Commission. n.d.c. “EU Emergency Trust Fund for Africa – FAQ.” https://ec.europa.eu/trustfundforafrica/content/about/faq_en

- European Commission. n.d.d. “EU Emergency Trust Fund for Africa – Strengthening Protection and Resilience of Displaced Populations in Libya.” https://ec.europa.eu/trustfundforafrica/region/north-africa/libya/strengthening-protection-and-resilience-displaced-populations-libya_en

- European Commission. 2016a. “Commission Announces New Migration Partnership Framework: Reinforced Cooperation with Third Countries to Better Manage Migration.” Press release, June 7. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_16_2072

- European Commission. 2016b. The Emergency Trust Fund for Stability and Addressing Root Causes of Irregular Migration and Displaced Persons in Africa. 2016 Annual Report. Brussels: European Commission.

- European Commission. 2020a. The Emergency Trust Fund for Stability and Addressing Root Causes of Irregular Migration and Displaced Persons in Africa. 2019 Annual Report. Brussels: European Commission.

- European Commission. 2020b. “EU Emergency Trust Fund for Africa – All Projects.” https://ec.europa.eu/trustfundforafrica/navigation/all-projects_en

- European Commission. 2021. The Emergency Trust Fund for Africa. 2020 Annual Report. Brussels: European Commission.

- European Union. 2015. “Agreement Establishing the European Union Emergency Trust Fund Stability and Addressing Root Causes of Irregular Migration and Displaced Persons in Africa.” https://ec.europa.eu/trustfundforafrica/sites/euetfa/files/original_constitutive_agreement_en_with_signatures.pdf

- Fechter, A.-M. 2014. “Living Well’ While ‘Doing Good’? (Missing) Debates on Altruism and Professionalism in Aid Work.” In The Personal and the Professional in Aid Work, edited by A.-M. Fechter. Abdingdon: Routledge, 84–106.

- Ferreira, M. R., A. Carvalho, and F. Teixeira. 2017. “Non-Governmental Development Organizations (NGDO) Performance and Funds—A Case Study.” Journal of Human Values 23 (3): 178–192. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0971685817713279.

- Fruttero, A., and V. Gauri. 2005. “The Strategic Choices of NGOs: Location Decisions in Rural Bangladesh.” Journal of Development Studies 41 (5): 759–787. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00220380500145289.

- Gibelman, M., and S. Gelman. 2004. “A Loss of Credibility: Patterns of Wrongdoing among Nongovernmental Organizations.” VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 15 (4): 355–381. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-004-1237-7.

- Gourevitch, P. A., and D. A. Lake. 2012. “Beyond Virtue: Evaluating and Enhancing the Credibility of Non-Governmental Organizations.” In The Credibility of Transnational NGOs: When Virtue is Not Enough, edited by P. A. Gourevitch, D. A. Lake, and J. Gross Stein, 3–34. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Islamic Relief. 2018. “Justice and Protection for Refugees: Building on the UN’s Global Compact.” https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/IRW%20GLOBAL%20COMPACT%202018%20v2.pdf

- Joint NGO Statement. 2016. “Joint NGO Statement Ahead of the European Council of 28-29 June 2016. NGOs Strongly Condemn New EU Policies to Contain Migration.” https://oi-files-d8-prod.s3.eu-west-2.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/file_attachments/jointstatementeumigrationresponse.pdf

- Jones, B. 2017. “Looking Good: Mediatisation and International NGOs.” The European Journal of Development Research 29 (1): 176–191. doi:https://doi.org/10.1057/ejdr.2015.87.

- Keating, V. C., and E. Thrandardottir. 2017. “NGOs, Trust, and the Accountability Agenda.” The British Journal of Politics and International Relations 19 (1): 134–151. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1369148116682655.

- Keck, M. 2015. “Comparing the Determinants of US-Funded NGO Aid versus US Official Development Aid.” VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 26 (4): 1314–1336. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-014-9464-z.

- Keck, M., and K. Sikkink. 1998. Activists beyond Borders: Advocacy Networks in International Politics, 1–38. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Keijzer, N., and F. Bossuyt. 2020. “Partnership on Paper, Pragmatism on the Ground: The European Union’s Engagement with Civil Society Organisations.” Development in Practice 30 (6): 784–794. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09614524.2020.1801589.

- Kim, S., and S. Lightfoot. 2017. “The EU and the Negotiation of Global Development Norms: The Case of Aid Effectiveness.” European Foreign Affairs Review 22 (2): 159–175.

- McGann, J., and M. Johnstone. 2006. “The Power Shift and the NGO Credibility Crisis.” International Journal of Not-for-Profit Law 8 (2): 65–77.

- McPherson, E. 2016. “Source Credibility as “Information Subsidy”: Strategies for Successful NGO Journalism at Mexican Human Rights NGOs.” Journal of Human Rights 15 (3): 330–346. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14754835.2016.1176522.

- Mitchell, G. E., and S. S. Stroup. 2017. “The Reputations of NGOs: Peer Evaluations of Effectiveness.” The Review of International Organizations 12 (3): 397–419. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-016-9259-7.

- Molenaers, N., B. Jacobs, and S. Dellepiane. 2014. “NGOs and Aid Fragmentation: The Belgian Case.” VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 25 (2): 378–404. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-012-9342-5.

- Mosley, J. E. 2012. “Keeping the Lights on: How Government Funding Concerns Drive the Advocacy Agendas of Nonprofit Homeless Service Providers.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 22 (4): 841–866. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mus003.

- OECD.stat. 2020. “DAC Table 1. Total Flows by Donor.” https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?datasetcode=TABLE1

- Oxfam. 2015. “Valletta: Africa Trust Fund Must Help People, not Build Barriers.” https://www.oxfam.org/en/press-releases/valletta-africa-trust-fund-must-help-people-not-build-barriers

- Oxfam. 2016. “EU Ministers Must Change Course on Migration Cooperation with Africa.” https://www.oxfam.org/en/press-releases/eu-ministers-must-change-course-migration-cooperation-africa

- Oxfam. 2017. “An Emergency for Whom? The EU Emergency Trust Fund for Africa – Migratory Routes and Development Aid in Africa.” Oxfam Briefing Note. https://www.oxfam.org/en/research/emergency-whom-eu-emergency-trust-fund-africa-migratory-routes-and-development-aid-africa

- Oxfam. 2020a. “The EU Trust Fund for Africa. Trapped between Aid Policy and Migration Politics.” https://oxfamilibrary.openrepository.com/bitstream/handle/10546/620936/bp-eu-trust-fund-africa-migration-politics-300120-en.pdf

- Oxfam. 2020b. “EU Aid Increasingly Used to Curb Migration.” https://oxfamapps.org/media/press_release/eu-aid-increasingly-used-to-curb-migration-oxfam/

- Sakue-Collins, Y. 2021. “(Un)Doing Development: A Postcolonial Enquiry of the Agenda and Agency of NGOs in Africa.” Third World Quarterly 42 (5): 976–995. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2020.1791698.

- Sanchez Salgado, R. 2014. “Rebalancing EU Interest Representation? Associative Democracy and EU Funding of Civil Society Organizations.” JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 52 (2): 337–353. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12092.

- Scurlock, R., N. Dolsak, and A. Prakash. 2020. “Recovering from Scandals: Twitter Coverage of Oxfam and Save the Children Scandals.” VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 31 (1): 94–110. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-019-00148-x.

- Szent-Iványi, B., and P. Timofejevs. 2021. “Selective Norm Promotion in International Development Assistance: The Drivers of Naming and Shaming Advocacy among European Non-Governmental Development Organisations.” International Relations 35 (1): 23–46. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0047117820954234.

- Unerman, J., and B. O’Dwyer. 2010. “NGO Accountability and Sustainability Issues in the Changing Global Environment.” Public Management Review 12 (4): 475–486. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2010.496258.

- van Dillen, B. 2015. “A Missed Opportunity in Valletta.” https://concordeurope.org/2015/11/17/a-missed-opportunity-in-valletta/

- Werker, E., and F. Z. Ahmed. 2008. “What Do Nongovernmental Organizations Do?” Journal of Economic Perspectives 22 (2): 73–92. doi:https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.22.2.73.

- West, K. 2001. Agents of Altruism: The Expansion of Humanitarian NGOs in Rwanda and Afghanistan. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Wirsching, S., and B. van Dillen. 2016. “Migration for Development and Human Rights — The Need for EU Policy Coherence.” https://concordeurope.org/2016/03/22/migration-development-human-rights-need-eu-policy-coherence/