Abstract

While exploring the everyday experiences of Tonga youth, this paper draws on a participatory graffiti-on-board project in Binga, a rural community in Zimbabwe. Focus is placed on what shapes and drives youth aspirations in precarious contexts marked by unemployment and poverty. Using graffiti to create participatory and artistic engagements, the research aims to stretch the limited boundaries of social and political space available to the youth for discussing issues that concern their development pathways and livelihoods. The article presents everyday narratives that impact on Tonga youths’ aspirations, endeavouring to create a space where they can visualise their prospective futures. Additionally, exhibition spaces are seen as sites for the construction of a collective voice and political capabilities for the youth. We argue that aspirations among disadvantaged youth evidence the broader geopolitical conflict that exists in marginalised communities in Southern Africa. A lack of spaces to construct political voice among the youth curtails their capabilities and agency to choose from existing development opportunities in an uncertain future. We discuss the potential role of participatory art in relation to this in providing spaces for political voice, unsettling established power dynamics and developing a collective, unified voice that might influence governance processes in fragile contexts.

Introduction

Young people represent over a fifth of the world’s population but are nonetheless often marginalised in decision-making and planning processes in economies and societies whose outcomes significantly affect them (Cuervo and Miranda Citation2019). As such, young people are directly and disproportionately affected by challenges such as limited access to reasonable work, limited space for democratic engagement and the underrepresentation of their voices in government. Focussing on the Global South, this paper makes theoretical and empirical contributions to youth studies, a research gap having been demonstrated by the abundance of studies skewed towards the Global North (Cooper, Swartz, and Mahali Citation2019). It builds on the agenda and need for ‘a conceptual and empirical space of invention and experimentation in youth studies that moves the research agenda beyond the universal conceptualisations from the Global North’ to integrate viewpoints and narratives both about and from young people in the Global South (Cuervo and Miranda Citation2019, 1). Focussing on Tonga youths from the Binga District in Zimbabwe, the paper highlights the complexities of disadvantage that are a direct result of exclusion.

Zimbabwe faces social, political and economic challenges that affect youth development as well as their prospects for forming attainable and viable aspirations, with the impact felt most strongly by the rural and ethnic minority youth. This research was conducted in Matabeleland North Province, north-west of Zimbabwe, in the Binga District; the district is inhabited by the Tonga, who form the third-largest ethnic group. Census reports show that about 70% of Binga District’s population can be classified as poor or extremely poor (Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency [ZIMSTAT] Citation2012). The Tonga may, therefore, be seen to experience some form of social disadvantage and economic marginalisation (Gwindingwe, Alfandika, and Chateuka Citation2019). They have furthermore been subjected to structural violence, as evidenced by their invisibility in the political, social and economic spheres. It is this invisibility that perpetuates a lack of participation by the community, especially the youth, and exhibits itself as a certain type of poverty (e.g. economic, social and political). In any context, the exclusion of a country’s youth in development agendas is not only a matter of concern for their personal development but has implications for the future development of the district, region and the country as well. Although what constitutes participation may be debatable, our position is that the active engagement of the youth in what they desire to ensure their well-being requires a non-passive structural approach. As Marovah and Mkwananzi (Citation2020) argue, participatory spaces create an environment for young people to confidently and meaningfully engage in and contribute to debates and processes that advance what they reasonably aspire to be and do. It is therefore our view that non-passive engagement with the youth transcends a holistic approach to addressing their needs. However, most Tonga youth are not advantaged to such processes because of the seclusion of their rural community. Consequently, their voices remain silenced; they have fewer opportunities to gain access to education and employment and remain at risk of cyclical poverty. Based on this context, we explored ways in which participatory art-based methodology might foster the political voice of these youths.

We contend that the aspirations of the disadvantaged should be viewed as evidence of the presence of opportunities to expand their personal and professional horizons amid constrained engagement spaces. The expansion of these horizons advances the capacity to aspire, which for the poor is often brittle and thin because of fewer opportunities to practise (Appadurai Citation2004). However, as asserted by Paat (Citation2016), we acknowledge that even in the presence of the opportunity to make a choice in these disadvantaged communities, how young people’s personal or professional paths unfold is shaped by the complexity of individual life courses that are often shaped by multiple factors. Consequently, aspirations may be, and indeed often are, multidimensional and vary from individual to individual and from society to society (Appadurai Citation2004). This complexity and multidimensionality are often pronounced in marginalised societies – in the case of our project, rural communities – as access to resources and opportunities remains limited because of both geographic and systematic developmental neglect.

Questions on the kind of aspirations that young people have, whether educational, professional, political or general, require context-specific, in-depth analysis rather than metric-based assumptions. To understand the interaction of environments in which young people’s aspirations are formed, this paper aims to (1) contextualise the lived experiences and political voice of a number of youths in Binga District, (2) highlight their aspirations, and (3) explore how participation and deliberation can widen their aspiration maps through collective stories. We use data from 12 artefacts and interviews with 12 youths, as well as two interviews conducted with representatives from one youth-based non-governmental organisation (NGO) and the BaTonga Community MuseumFootnote1 between August and November 2019. Consent to participate was sought from the youths and the two representatives.Footnote2 We draw on Amartya Sen’s capability approach to analyse structures enabling and constraining the political participation of the participants. We commence by providing an overall understanding of the youths’ personal and contextual aspirations and then align this with the capability approach and the concept of political poverty, as signified by the youths’ lack of opportunities for public engagement with relevant structures. We then discuss the potential impact of participatory arts in creating spaces for political voice for both individual and collective aspirations. Finally, we detail the construction of political subjectivities through the process of these youths sharing their stories.

Youth aspirations in the Global South

Many young people in Sub-Saharan Africa experience multiple forms of social, economic, cultural and political deprivation in combination, including exclusion from political dialogue, poor to non-existent education, and limited access to housing, basic services and economic opportunities. In these harsh conditions, the formation and expression of aspirations may seem quite impossible. Gender, ethnicity and geographic location are factors that may, sometimes, restrict youths from progressing towards their desired lives. Similarly, in the context of this research, the formation, expression and realisation of aspirations are heavily influenced by these factors. The marginalisation of the Tonga community renders them ‘invisible’ in most political, economic and social development discourses. In conditions where they wish to express their concerns, there are limited ways in which their voices can be heard by wider audiences. As such, aspirations formed within such a community would seek (and need) to challenge these exclusionary practices. Drawing on Appadurai’s idea that aspirations are never merely individual but are always formed in interaction and in the ‘thick of social life’ (Appadurai Citation2004, 67), we similarly view aspirations as relational, and formed in consideration of the other and through multilayered relations within society. Accordingly, although aspirations may have to do with individual, preferences and choices, they are often shaped through social cohesion (Appadurai Citation2004). Because the capacity to aspire, like any complex cultural capacity, requires practice, repetition and exploration (Appadurai Citation2004, 69), for those on the margins of society – such as the youth represented in this paper – aspiration pathways are likely to be more rigid as they lack the necessary resources. The absence or unavailability of these resources would mean a thinner and weaker sense of the available or desirable pathways (Walker and Mkwananzi Citation2015), leaving those with access to resources (in the cities) to enjoy wider aspirational horizons (Appadurai Citation2004).

While for the rich and well-resourced, aspiration maps may be wider and offer room for spontaneity, including moving beyond the thresholds necessary for basic human survival, for disadvantaged groups, their aspirations are often influenced by a desire to merely achieve a threshold for basic, socially just survival (e.g. political recognition, employment opportunities and access to schools). Therefore, within the diverse social ecologies of aspirations, there are demarcated levels of aspiration formation, both vertical and horizontal, taking into account the diverse factors that define the members of a society, for example age, gender, political position, belief system and the like. These factors cause individual aspirations to vary from person to person. Then, there are ‘collective’ aspirations, which are held by a collective, such as a unified desire to be politically recognised as a group (e.g. based on gender or ethnicity).

Although aspirations are formed within collective environments (see Mkwananzi and Cin Citation2020), they have often been individualised for the purposes of understanding individual well-being. Yet there remains a strong collation of relationality in certain aspirations. For example, the youths in our project held valued individual aspirations, but also exhibited a collective desire for political and social recognition as an ethnic group, which is what our paper focusses on. Therefore, although there is a growing body of literature on the youth’s aspirations in the Global South (see Mkwananzi Citation2019; DeJaeghere Citation2018; Leavy and Smith Citation2010), there is minimal focus on the collective aspirations, or at least a minimal focus on the collective desire for political voice, in our context. In Zimbabwe, several youth studies have recently dwelt on issues such as human rights (Gwirayi and Shumba Citation2011), youth health (Musizvingoza and Wekwete Citation2018) and child marriages (Dzimiri, Chikunda, and Ingwani Citation2017). Amid this increased youth-focussed research, a gap nonetheless remains in the aspirations literature. However, after analysing the literature, we conclude that the reported factors are anti-youth development and often have a negative impact on youth aspirations. For example, Masarurwa (Citation2018, 17) reported low youth participation across economic, electoral and governance processes in Zimbabwe and the youths’ lack of skills to engage government. Closer analysis concludes that such low levels of participation in spheres of influence might provoke an interest in young peoples’ aspirations, which our project picks up on. With our arts-based methods, we also contribute to the conversation on the knowledge and skills required to engage government and other stakeholders in addressing structural challenges. In the next section, we conceptualise aspirations in relation to the capability approach by showing how they are formed through, or may be transformed into, capabilities.

Capabilities, aspirations and political poverty

There has been an increasing amount of research in the Global South on the capability approach and aspirations (Mkwananzi Citation2019; Mkwananzi and Cin Citation2020), gender equality (Cin Citation2017) and arts-based participatory methods (see the edited collection by Walker and Boni Citation2021). In this paper, we use Sen’s (Citation1999) capability approach, along with the concepts of aspirations (Appadurai Citation2004) and political poverty (Bohman Citation1996), to offer an intersecting framework that explores the aspirations of the youth.

From a normative standpoint, the capability approach is interested in the freedoms and opportunities that individuals (in our context, the youth) have to live the lives they value (Sen Citation1999). When evaluating one’s well-being, it is essential to consider the real opportunities and freedoms (capabilities) that the individual has access to, to live a valued life (desired well-being). The quality of life that a person enjoys is not only about what one achieves but also about the options that one has to decide on life opportunities (Sen Citation1992). The capability approach advocates the freedom of individuals as its first principle, thus promoting individual choices and freedoms; however, these freedoms vary from context to context. In an ideal society, the capacity to aspire may be seen as a freedom that allows one to expand one’s aspirational horizons. Ideally, supportive conversion factors (structures and environment) would be in place for the capability to aspire to flourish, allowing for a positive force that drives agency. Therefore, a constrained environment may limit the formation and expression of aspirations and, as a result, may lead to perpetual disadvantage and marginalisation. We have, through the use of the capability approach, identified the opportunities that influence the aspiration process (formation, expression and achievement) among the youth in our study. This process is largely influenced by the context of Binga, as the social setting impacting on the relevant capabilities and aspirations (Sen Citation2009). The social ecology of Binga not only impacts on the youths’ freedoms and opportunities (which, according to Sen [Citation1999], are important for development to occur), but also shapes the action they could take towards what they think is achievable. In acknowledging the close relationship between the individual and the community, most of the youths’ aspirations are to encourage a better culture for all by addressing community challenges such as poverty and its associated problems (e.g. early marriage) as a way to escape from it. This relationship makes forming and achieving aspirations a multidimensional and complex journey. However, Buckler et al. (Citation2021) note that the disadvantaged states leading to such complexity should be viewed as non-static, as individual experiences and contexts evolve over time.

Secondly, our project aimed to contribute to the disruption of barriers that stand in the way of young people’s freedoms and aspirations by co-creating a platform for ‘political voice’ as a vehicle to express their everyday realities and challenges in making decisions about their lives. Our understanding of political voice is informed by the capability approach and intends to reveal the numerous ways in which young people display resilience and agency in addressing challenges and inequalities in their own contexts. We conceptualise political voice in relation to the youths’ struggles as citizens and in subverting demeaning stereotypes which have long since silenced them (Phillips Citation2003). This political voice is instrumental in improving their well-being as it helps them express and exercise their views to influence governance processes. Therefore, public deliberation and the space created for interaction through the participatory arts and exhibitions were vital for discussing issues of marginalisation within and among the wider society (in this case, the public who attended the exhibitions). The spaces also created a participatory and representative process, allowing young people to speak out against perceived injustices and identify the fundamental freedoms integral to their well-being (Sen Citation1992).

We are also cautious regarding the implications that political voice may bring, such as seeing young people as passive or as lacking political agency, and, therefore, we do not argue that young people do not have a voice, but rather flesh out the importance of this particular voice as building allegiance and forming a collective response and strategies against the injustices that act as barriers to their aspirations and capabilities. To this end, we believe a collective political voice has the potential to create advocacy when the youth speak (out) as members of one community. We additionally underline political poverty that dominates in precarious contexts to signify a particular group’s lack of opportunities to be part of the public dialogue, thus subjecting them to public exclusion (Bohman Citation1996). This political poverty can be related to either power asymmetries or communicative inequalities that refer to cultural conditions of unequal power, as experienced by the Tonga youth. Sen (Citation1992) views poverty in multiple domains as a capability failure to meet the basic needs of commodities required for a set of functionings. Likewise, political poverty indicates the lack of opportunities, assets, means, or cultural and social power to have the political voice and equality of standing to make one’s concerns count in the public sphere (Bohman Citation1996). Such deprivation creates an invidious cycle to break as the social and economic disadvantages youth face result from culturally imposed political poverty, and their cultural resources occupy a position of unequal power in society. Cin and Süleymanoğlu-Kürüm (Citation2020, 172) argue the importance of these unviable political structures as ‘conditions which do not allow for a deep discussion of knowledge [and] are often shaped by deliberative and structural inequalities that restrict access to the public sphere’, and add that addressing political poverty ‘requires political equality of access, skills, resources, and space to advance capacities for public functioning and knowledge production’. However, in the absence of a local public platform to express themselves and often being victims of pejorative designations, youth aspirations are shaped differently, and political poverty may affect their capacity to aspire and thus impede their desired well-being. Hence, in this research, the use of participatory arts as an alternative form of expression moves beyond its methodological and contextual relevance to act as an instrument that communicates the existence of political poverty and exclusion within Binga. The process of seeking alternative spaces for public engagement embeds individual and collective reflections that are expressed as the youths’ aspirations to craft a political voice and strong public claim and implicates the collective desire of a long-excluded community to build political subjectivities.

Participatory arts for political voice and aspirations

This research innovatively employs participatory arts as underpinned by the ideas of co-production, collaboration, community practice and public engagement, and encourages the dialogic interactions of artists, youths and communities working towards social change. We used participatory arts to contribute to the transformation of individuals and society through raising critical consciousness, thereby not only introducing political and social issues to the public sphere (Borisenko Citation2016; Sandoval Citation2016), but also bringing communities into dialogue to document challenges in creating a bottom-up approach. In our research, participatory arts included youths mapping out, deciding on and executing plans for future actions, thus involving them in a collaborative approach to the pressing issues they face (Tzifakis Citation2011); most importantly, however, they also accounted for the diversity of their experiences. Mapping out was a process that included a number of workshops where youths, artists, museum representatives and us as researchers came together to discuss themes the youths wanted to focus on, spaces they wanted to use for exhibitions and the audience they wanted to invite to the exhibitions. Through personal and collective creative expressions, the youths used graffiti on boards to challenge long-standing biases and stereotypes impacting on their own lives and the lives of others (Cooke and Soria-Donlan Citation2019; Wheeler Citation2018).

Engaging in social issues and expressions of the desired change involves a lot of self-exploration, and addressing the multidimensional nature of these issues requires inclusive spaces for engagement (Chamberlain, Buckler, and Mkwananzi in press). Emerging platforms for political representation of youth – such as youth parliaments or councils (Shephard and Patrikios Citation2013), local forums (Zihnioğlu Citation2019) or online campaigning (Henn and Foard Citation2014) – are often criticised for the apparent imitation of an adult and androcentric conception of political space occupied by adults (Wood Citation2012). These platforms are viewed as fostering a male-dominated political culture that does not open space or allow room for less-trained voices like the Tonga youth (Young Citation2010). The use of participatory arts may, therefore, be viewed as an alternative platform for the youth who are not disinterested in politics but cannot actually find ‘safe’ spaces in which to engage in significant and purposeful deliberation. Such spaces would more likely influence public decision-making which, in turn, could translate to policy outcomes (Shephard and Patrikios Citation2013).

The process included a five-day participatory art graffiti workshop with 12 youths between 18 and 25 years of age, one representative from Basilwizi NGO TrustFootnote3 and two representatives from BaTonga Museum, with the trust and the museum being the local partnering organisations. presents the demographics of the participating youths. We sought to work with youths irrespective of whether they had already left school, and this was the age range provided by the NGO. The partnering organisations had direct experience of working with the community and had built up trust over the years, and therefore their involvement as partners eased the process of recruiting participants through an open call. They first organised a pre-engagement event with the community’s youth to talk through the aims of the project and to discuss the ways in which it could be co-designed with them to contribute to the well-being of the community. We had a diverse team consisting of three university researchers from South Africa, Zimbabwe, and the UK, respectively, and two artists with differing levels of research experience but all with some experience of participatory research and arts.

Table 1. Participating youths.

The first one-and-a-half days of the workshop were used to discuss the challenges and opportunities experienced by the Tonga youth as a minority tribe in Zimbabwe. Icebreaker games and activities such as The River of Life were used during the workshop. We discussed and identified various themes, such as child abuse, early (or child) marriage, poverty and gender inequality, which later informed the graffiti created by the youths. The activities and the workshop were designed to encourage the participants to identify and discuss their achievements, aspirations and what they needed to see those aspirations realised. Furthermore, the creative activities sought to help the youths identify the themes they wanted to highlight in the graffiti. We also aimed to build solidarity among the participants and the community they live in, and set up a WhatsApp group to further foster relationships among us and to stay in touch to design the dissemination activities after the workshops had been concluded. On the second day, two professional artists commenced with the graffiti training, and this was followed by the creation of the graffiti on large boards rather than walls so that they could be mobilised for dissemination. (Also, graffiti artwork placed directly on walls would have required commissioned permission from the Zimbabwean authorities.) This art training is of great importance to the youths, seeing as street art, just like other forms of visual art, has the potential to recognise and value epistemological diversity in making knowledge while exploring daily inequalities – making the individual an epistemic subject rather than the empirical subject (Santos Citation2016). On the final day of the workshop, there was an in-house discussion and photoshoot of the graffiti. As the youths completed their graffiti, an interview was conducted with each of them to determine what had been learnt during the workshop. One-on-one interviews were also conducted with the representatives of the museum and the youth NGO, and interview data with the youths has been transcribed verbatim. We also discussed future plans of how and where to display the graffiti-on-board artworks and the audience we should invite to those exhibitions.

Consequently, we view the participating youths as collaborators in the project, as they participated in the process both as trainees and as researchers who analysed the data (their stories) and disseminated the knowledge through exhibitions at a public university and art galleries in three cities (Bulawayo, Gweru and Harare) after the workshop was concluded. We also drew from their expertise and contextual knowledge of local experiences; this complemented the knowledge and skills we possessed as researchers. In this way, our knowledge and expertise complemented each other’s. The process itself was creative, dialogical and interactive in the sense that the youths also focussed on their own resilience, what they have achieved thus far, and how they could use the collectivity and agency they own to expand their aspirations. In this manner, the research was able to construct a ‘research pedagogy consistent with participatory aspirations and values so that participants experience a process of fairness both for themselves and towards others’ (Walker, Martinez-Vargas, and Mkwananzi Citation2020, 6).

We used graffiti as a participatory art method for several reasons. Firstly, creating graffiti accompanied by individual and collective stories and narratives is a political act based on everyday experience and affords one the opportunity to articulate experiences of marginalisation (Wheeler Citation2018). Vogel et al. (Citation2020) show how graffiti conveys the struggles and the fabric of everyday spaces and experiences or everyday practices of conflict and peace at the local level. Although arts literature makes a fine-grained distinction between graffiti and street art – assigning the latter a more consensual, rebellious and activist form of art (Ross Citation2016; Bacharach Citation2015) – both methods aim to convey a social or political message the participants want to share, thereby raising awareness about socio-political issues. Drawing on the argument put forward by Vogel et al. (Citation2020) on the graffiti versus street art debates, we engage with a particular community and their experiences and everyday manifestations, and therefore use the term ‘graffiti’ as a particular form of inquiry in this research.

Methodologically, we draw on the work of Bacharach (Citation2018), who used street art to address epistemic injustice and the negative identity prejudices that silence certain groups of people. Our aim was to use graffiti as a peaceful tool to convey a political message while at the same time considering the sensitive political climate in Zimbabwe. It was essential that we attune the use and method of graffiti to this particular context as our aim was to communicate the concerns of Tonga youth to the public. Graffiti was used as a language through which the youths in our study were able to develop a political voice and agency to construct an image of Tonga youth that the public would be unfamiliar with. We were also interested in presenting a boundary work between art and social advocacy of redressing political poverty experienced by the youth. Towards this, graffiti was both participatory and engaging as it dislocates power structures in the production process but also challenges the power dynamics in the public domain during the dissemination activities and exhibition by introducing the experiences, agency and voice of the silenced to the public imagination. Given this political role of graffiti, we present below how education and cultural heritage emerged as encapsulated values and aspirations in the artefacts the youths produced. We then highlight the political communicative strategy aspect of the graffiti (Gyasi Obeng Citation2000) in forming political subjectivities and capabilities of the youth who may not otherwise have been heard. We also discuss education and cultural heritage as aspirations valued by the participating youths, and then move on to exhibition spaces to argue how they emerged as sites for political voice and subjectivity.

Education and cultural heritage as valued aspirations

Educational provision in Zimbabwe, starting from primary school, is not free and requires families to pay a fee which is not always affordable to those residing in rural and disadvantaged communities like Binga. As a result, many female youths in this project had their school expenses funded by CAMFED (Campaign for Female Education), an international NGO that provides support to girls to prevent them from leaving school due to any one of many diverse disadvantages. Such interventions by organisations create both a capability (opportunity) and a conversion factor (positive environment) for girls to expand their aspirational maps and pursue them to build better futures. Nonetheless, we do recognise that even with available capabilities, different individuals may not necessarily make use of such opportunities in a similar way. For some girls, their personal and family backgrounds may pose as conversion factors with negative effects. For example, some of the girls have family responsibilities requiring them to stay at home (e.g. taking care of or helping grandparents) while for others the issue is generally a lack of support, knowledge and motivation as family members may not have a higher education background. This reinforces the assertion by Johnson et al. (Citation2009) that even in contexts where families support high aspirations in general, they may be unable to support the decision-making process due to a lack of knowledge or any helpful first-hand experience. For girls, such a marginalised context and restrictive environment complicate the formation of the capacity to aspire. For boys, their studies are often funded by the committed families who value education, expecting that boy’s further education may improve the social and economic mobility of the family and their overall well-being. However, university costs are often unaffordable for most young people, thus making financial resources the main conversion factor limiting their progression to higher education. The lack of or inability to access funds is exacerbated by the constrained environment for student loans and the absence of a stable student funding scheme. Thus, although students may have the capacity (such as ambition, personal motivation) – as is the case with most of the youths in our project – a lack of structural opportunities leads to personal aspirations remaining unexplored.

Despite the limited instrumental benefits of education in Zimbabwe in terms of the potential opportunity to secure decent employment,Footnote4 the youth still value and desire the acquisition of a formal education. As indicated in , three of the youths are supplementing mathematics courses so that they can have a recognised O level certification. One holds a university degree, and another is studying supply chain management, while Vimbai is still seeking opportunities to attend university. While the literature has shown that education is seen by young people as a transition to a better life (Charaf Citation2019), it was mostly the female participants who indicated their desire to attend university, hoping that an opportunity for entry is enough motivation to seek funding. However, because of poverty, some girls saw marriage as an opportunity to escape financial hardship. For example, Luba noted: ‘I asked my parents that they can marry me off if they want so that they would have one less plate on the table’. The marriage failed and her husband left her two years later and migrated to Botswana to seek employment, and she has never heard from him since. She then went back to school in the hopes of one day becoming a teacher. While she thought marriage was the only option to survive, with support from CAMFED, she now believes that studying may be the only route to a dignified life. On the other hand, for those who are not offered similar opportunities by CAMFED, they potentially live to experience injustices such as domestic violence and being deprived of their agency to take important decisions concerning their life.

Although students may aspire to becoming lawyers or teachers, the poorly resourced public schools, poverty and a lack of guidance regarding career paths remain the main barriers to progressing to higher education. In the absence of access to information or technology in rural areas and role models who might assist them, the youth depend for advice on the few peers in their communities who have made it to university. Most of the youths, notably the males, indicated their desire to further develop the technical skills that they were already using. According to Nhapi and Mathende (Citation2019, 153), while the education system in Zimbabwe churns out over 300,000 young people into the labour market annually, the formal economy is unable to accommodate them because of the current instability in the country. Also, graduates may possess theoretical knowledge instead of the technical skills required to self-sufficiently venture into the informal sector where they could start their own enterprises. Thus, the aspirations of the youth related to gaining vocational skills and knowledge are in line with the current reality of the state of the economy in the country. Most of the vocational aspirations were attuned to the tradition and culture within the Binga region. The youth are also aware of the opportunities available in their communities, such as the fishing market on the Zambezi River; however, they are disappointed to see that commercialisation of the sector often involves large companies. Commercial ownership of local resources by large corporations neglects the local youth and confiscates the only resource available to the Tonga community through monopolising natural resources in the community. A small number of community members do day-to-day fishing to sell at the local market. However, such self-driven initiatives ultimately create little income compared to the big businesses operating in the district. Therefore, some of these youths aspired to establish their own small-scale fishing businesses in the region. Farai, for instance, highlights the importance of fishing for the community:

I have an interest to be in the fishing industry, even to breed fish in fishponds so we can harvest more fish and sell. Tonga people are privileged because it’s where the Zambezi is passing through, I think it’s one of the largest in terms of water capacity in Zimbabwe so because of that we Tonga people, we are more exposed to the fishing industry than any other district in Zimbabwe. [People] must know that the fishing industry is just like any other form of industry such as mining, and it’s one of the major backbone industries of the economy in Zimbabwe and people must also depict that it’s only Tonga people who are able to do fishing and that they can do it efficiently at full capacity. (Farai)

The desire to fish is also reflected in the graffiti by one of the youths (), who said he wanted to build a fishing business and how the old boat they have was beneficial to his family in terms of meeting their needs and paying off his school fees.

Some of the youths expressed a desire to preserve the cultural heritage of the Tonga language and crafts that are unique to the Tonga community, an example of the influence of social ecology on the youths’ capabilities and aspirations formation (Sen Citation2009). The BaTonga Museum in the region was established in 2002 to tend to and display this heritage. There is also a craft centre next to the museum which is funded by the Ministry of Women’s Affairs to encourage women to weave baskets and sculpt wooden animals to sell to locals and tourists alike. Some youths expressed a desire to learn craftwork to earn money to fund their education but also to ensure the continuation of this heritage from one generation to the next. Reasoning that there is no future in learning crafts, one of the youths noted how his parents were reluctant to teach him, instead encouraging him to study:

I would like to learn how to do crafts so that I can save some money for my university degree. But I will also have something to pass on to my children – something of my own culture. I am worried about the future of Tonga language and heritage, but the elder generation discourage us saying that we should rather study as craft business is not a long-term job and cannot give us a future. It is not only about earning money but holding onto one’s own identity.

The youths’ aspirations to learn cultural crafts are mostly driven by economic concerns as well as their desire to pass on their cultural practices, values and heritage to future generations. This provides a basis for the argument forwarded by Luebker (Citation2008) that the education system in Zimbabwe has often prepared students for white-collar jobs in the formal sector but fails to equip them with technical or entrepreneurial skills, or a tangible or intangible heritage. However, many youths value indigenous knowledge and are seeking opportunities to learn indigenous heritage and local cultural practices, viewing them as resources on which they can draw to build their lives. Although the cultural identities of the Tonga are often stereotyped, most of them viewed this co-production of graffiti as a bonding exercise and an opportunity to showcase their cultural identities.

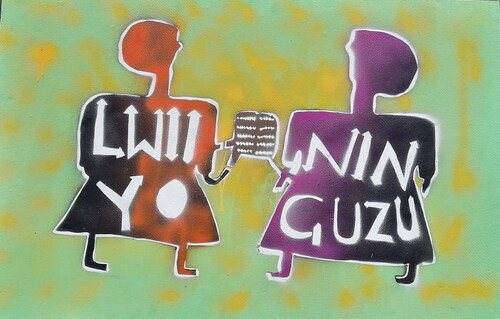

The workshop was held at the BaTonga museum where the Tonga cultural heritage is displayed. During both the interviews and workshops, the youths spoke proudly of the museum, cultural artefacts such as ncelwa (women’s smoking pie) or buntibe (drum and performance) and expressed their desire to make the museum an important site in Zimbabwe, which could stand for recognition of the Tonga and their cultural and historical rights and practices. Mashingaidze (Citation2013) sees the building of the BaTonga museum as a protest against subjugation, but the exclusion of the Tonga youth in the operation of the museum or in the continuation of cultural artefacts is not sustainable and can only make the museum a heritage hub rather than a living memory (Saidi Citation2019). The cultural performances, introduction of cultural fairs or developing education programmes that attend to the heritage of the Tonga are what the youth value – their heritage advocacy is shaped by the consciousness of making the most of their available resources. They see the elder generations as repositories of cultural knowledge and want to use their knowledge culturally in an efficient manner to create economic opportunities for the community and the youth of Binga, who are forced to leave the region to study or work. During the workshops, the participating youths also engaged with Tonga poetry and shared their favourite poems with one another, and to highlight the importance of their language, some graffiti and the manifestos (captions and stories) attached to them were written in Tonga. The graffiti artefact by Rudo () shows two girls holding a book entitled lwiyo ninguzu (Education is Power), highlighting the importance of education for girls in disadvantaged contexts as an important capability. Such a basic capability would, for the girls, challenge stereotypical and gendered roles by advancing opportunities such as the prospect of decent employment, leading to a better standard of living, which Wolff and De-Shalit (Citation2013) aptly term a fertile functioning.

The ability to speak, write and produce artwork in their native language was important to the youths and addresses the importance of indigenous knowledges in Southern Africa. The endeavour of the youth, particularly regarding the recognition of their culture and language, was to challenge dominant cultures in Zimbabwe which did not open or allow for epistemic spaces for the Tonga to freely express their cultural identity. Therefore, discussing the fundamental issues that matter to them, co-creating, providing peer feedback to each other and, most importantly, the collective creation among them through the dialogical processes were highly valued by the epistemically marginalised and unrecognised Tonga youth. The exhibitions were held at the Bulawayo Art Gallery and at the National Museum of Zimbabwe in Harare. Engaging with individuals who visited their exhibitions gave the youths a sense of being agents who were transporting their concerns, as well as a part of their culture, to public social spaces. For the youths, acting as ethical interlocutors and subjects on behalf of their communities was one important aspiration they have achieved: by displaying certain aspects of their heritage to outsiders, and presenting their history and culture, along with their desire for an education that values their identity and would allow them to actualise their language, they gained some agency as political subjects.

Exhibitions and stories as spaces of construction of political subjectivities and voices

The stories expressed through the graffiti, and the subsequent exhibition spaces used to communicate them, are a relational process of political subjectivity as well as collective action (Wheeler Citation2018). The idea of exhibiting the work in three cities, at a public university and at the gallery, and finally at the museum was a unique opportunity for the youths to express their aspirations and share their cultural practices. These places were strategically chosen in collaboration with the participating youths.

The process of expressing political voice and the formation of political subjectivity emerged through the youths speaking collectively of their aspirations in public. This operates at two levels, the personal and collective, which intertwined with each other as discussed earlier in the paper. Although the stories behind each work of graffiti were unique and personal, taken together they reflected an engaged and co-constructed collectivity of the youths’ aspirations for opportunities to gain an education and the normative value of schooling, despite the growing body of research (Tikly and Barrett Citation2013) on the Global South which shows that quality education matters as much as ensuring that schooling enhances freedoms and challenges status quos in communities. However, when there is outright poverty, the concerns regarding the quality of education become less of a priority, and it becomes difficult to move beyond the normative good of any kind of education as it is seen as the toll to remove oneself from poverty (Cin Citation2017). Likewise, the collective aspiration for higher and technical education was an important message articulated through the graffiti and led to a number of political engagements between the youths and the academics at Midlands State University in Gweru during their exhibition at the university. Being on the premises of a university and engaging with academics and students created a feeling of recognition. Talking through what they would like to study at the university, the ways in which they could secure access to university, and the opportunities available for marginalised communities like themselves were important for making informed choices. On the other hand, having the engagement space with university staff and students also constituted their political subjectivities as an achievement with regard to challenging the hermeneutic conditions that ignore the Tonga youth and see them as unfit agents for any kind of higher education. Such engagements were expressed as the ‘unavailable and missed’ opportunities (conversion factors) in young people’s lives and were essential to enable political capability.

The youths in our study implied the value of participatory arts for creating solidarity at a grassroots level and developing a collective capability to express their views, but they were also aware that political voice developed through arts may not be enough in itself to bring about change unless there is a consistent collectivity and a grassroots formation. This is because the mediation between local and state actors requires the formation of a collectivity or organisation that could transform these voices into viable action. For instance, one of the participants noted that ‘These kinds of workshops or exhibitions can bring us together, unite us Tonga youth and can catch the attention of the people to listen to us because it is peaceful and not a deeply political act’. Here, what the youth meant by a political act was to highlight that the project and collectivity did not mean creating dissent in the highly politically sensitive and restrictive environment of Zimbabwe, but to create an ‘invited space’ for political voice. Even under authoritarian environments, such an ‘invited space’ advanced the political functioning to tell one’s own story and repositioned the youth, who have always been objects of research, into communicators (Ndlovu-Gatsheni Citation2017). However, local actors are frequently not in favour of the formation of such communities with strong political voices, even if they support the kind of political structures that would provide a particular social or political identity that is not based on domination or oppression (Staeheli, Attoh, and Mitchell Citation2013). We, as researchers, felt this to some extent as we were trying to secure spaces to hold exhibitions and were exposed to some doubtful questions from the bureaucratic structures regarding the purpose of the Tonga community and the nature of the project and intended exhibition.

The act of participating in the making of graffiti and taking these to public spaces equipped the youths with a sense of agency and encouragement and united them as one group, who were then able to negotiate their positions as part of art-sceneries in the museum and art gallery exhibitions. This helped to subvert, to some extent, some of the prejudices against the Tonga community. These spaces were also local points of action for claiming a political space to unsettle such biases by representing their heritage as in the form of a protest art. As one of the artists who trained the youths and participated in the exhibitions noted, the representation, through a less-known form of art in Zimbabwe, had an instrumental and important impact on sharing the heritage of the Tonga youth, which would probably not have caught the attention of the public if they were displayed as more traditional forms of art. In making this claim, we were cognisant of the criticism of participatory development through arts, and how it underestimates the existing political capabilities of the communities or authenticates the communal epistemologies (Williams Citation2004). Yet, our focus in these exhibition spaces can be described in two ways: as building alliances among the youth and moving this to the grassroots level to form a cross-institutional network of universities, and art-based institutions, in order to strengthen their network and ensure that their political voices are heard and supported. Secondly, it enhanced the political capital and capabilities of the youth, reshaped political networks and power, and changed patterns of recognition through the art of representation, as these reshaped political networks have the potential to build themselves into a discourse of rights and active citizenship in the long term (Brody Citation2021). The youths also noted the importance of the change that can be created by the opportunity of being introduced to different political and social networks. The change they wanted to see was to challenge the exclusionary discourses that include the negative perceptions that dehumanise their livelihoods. Therefore, for some of the youths, this exhibition space simultaneously worked as a space of attention, hope, interest and narrative imagination whereby the audience could reflect and embrace different emotions and interest in their culture. This again manifests the importance of arts in fostering creative personal and collective expressions to challenge long-standing stereotypes, as one of the youths, Luba, expressed: ‘The youth from Gweru learnt something from us as the youths from Binga. They did not know that we can also do something which is productive. They were really amazed’.

As we have highlighted, the emergence of alternative spaces through participatory arts in this research was very much related to the availability of only a limited space for the marginalised, but more broadly to the youth who are not disinterested in politics but who cannot find ‘safe’ spaces to express their agency. While capabilities lead to recognition, the capacity to speak and act are very much dependent on processes and spaces for engagement, which may not always be available. Participatory arts, collectivity and spaces for interaction become much more essential in challenging such structural, political and historical conversion factors. Such an environment is intrinsically important to the youths in our study, who noted their engagement as ‘innovative, peaceful and artistic’. Therefore, participatory art, which has been emerging as an alternative and epistemic space for public and political voice, offers an alternative and creative form of engagement that could afford the youth a unique opportunity to express themselves in alignment with their social and cultural backgrounds, while at the same time nourishing their political subjectivities (Cooke and Soria-Donlan Citation2019).

Conclusion

Drawing on evidence hewn from an art-based participatory project with Tonga youths from Zimbabwe, we have shown in this paper that graffiti, as a participatory art method, can reveal alternative narratives of under-represented communities. Political graffiti may also be an important source of knowledge production for marginalised communities and can create safe public spaces for engagement as well as create collective voices. Therefore, bringing arts to everyday spaces has the potential to remove barriers and challenge dominant structures constraining marginalised people’s ability to engage in social and political networking with non-oppressed groups. On the other hand, we acknowledge the potential for political dissent that can be created through graffiti especially in a politically sensitive context like that found in Zimbabwe; this imposes certain limitations on the extent to which the voices of the youth can be accommodated, heard and raised. There is a very nuanced and thin line between graffiti as political resistance to dominant discourses and being a distinctive and unique form of communication strategy in a fragile context. We also argue that participatory arts can highlight the values and aspirations at the local level and bring the everyday experiences of the youth, such as their aspiration for education and cultural recognition, to public spaces. Our research shows that along with the economic conversion factors enabling opportunities for access to education, equally important are the political capabilities of the youth and the availability of structures and spaces nourishing these capabilities. We argue that just as much as capabilities and functionings serving the basic needs of people, within the current geopolitical conflict of Southern Africa, the political need to be represented, to be heard and to be able to join public deliberations should also be a priority in the agenda of sustainable development programmes and policies. Creating such civic engagements through everyday creative practices may very well improve the political capabilities of Zimbabwe’s youth and thus render them more legitimate actors in the country’s public sphere.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the University of the Free State, Lancaster University, Midlands State University, BaTonga Community Museum, Basilwizi Trust, and the youths who participated in the study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Wadzanai Faith Mkwananzi

Wadzanai Faith Mkwananzi is Senior Researcher with the Centre for Development Support at the University of the Free State, South Africa. Her academic work has generally centred on higher education, migration, youth and development in Sub-Saharan Africa. She is specifically interested in pursuing research that develops the operationalisation of the capability approach, and engages more creative participatory methodologies to bridge the gap between education researchers and development practitioners and civil society at large.

Firdevs Melis Cin

Firdevs Melis Cin is Senior Lecturer in education and social justice at Lancaster University. She is a feminist researcher with a particular interest in exploring the relationship between education and international development. She also looks at how education can be used as a peacebuilding tool in conflict zones and employs socially engaged art interventions to understand the local meanings of peace in formal and informal education settings. She is the author of Gender Justice, Equality and Education: Creating Capabilities for Girls’ and Women’s Development (Palgrave, 2017) and the co-editor of Capabilities, Youth, Gender: Rethinking Opportunities and Agency from a Human Development Perspective (Routledge, 2018) and Feminist Framing of Europeanisation: Gender Policies in Turkey and the EU (Palgrave, 2021).

Tendayi Marovah

Tendayi Marovah is Research Fellow with the Centre for Development Support at the University of the Free State, South Africa. He is also a History Education Lecturer at Midlands State University in Zimbabwe. His research interests focus on curriculum and pedagogy in higher education and how they advance human development and social justice in Global South contexts. He uses the capability approach and philosophy of Ubuntu to theorise what socially just arrangements in educational institutions and society might need to look like in order to realise human development.

Notes

1 A museum in Binga anchored on community empowerment, participation, engagement and community development.

2 The study obtained informed consent from individual participants, and this was supported by both the Batonga Community Museum and the Basilwizi Trust. Both organisations work with all the youths who participated in the study. The consent included awareness that data gathered (including the graffiti) would be used to report the findings in academic and non-academic platforms.

3 A community development organisation founded by the local people of Binga District.

4 This is despite Zimbabwe’s latest unemployment rate soaring to 85% as of 2014 (Rusvingo Citation2015). The unemployment figures have remained more or less the same over the past six years (see Maunganidze, Bonnin, and Ruggunan Citation2021).

Bibliography

- Appadurai, A. 2004. “The Capacity to Aspire.” In Culture and Public Action, edited by M. Walton and V. Rao, 59–84. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Bacharach, S. 2015. “Street Art and Consent.” The British Journal of Aesthetics 55 (4): 481–495. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/aesthj/ayv030.

- Bacharach, S. 2018. “Finding Your Voice in the Streets: Street Art and Epistemic Injustice.” The Monist 101 (1): 31–43. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/monist/onx033.

- Bohman, J. 1996. Public Deliberation: Pluralism, Complexity, and Democracy. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Borisenko, L. G. 2016. “Arts-Based Peacebuilding: Functions of Theatre in Uganda, Kenya, and Zimbabwe.” https://www.narcis.nl/publication/RecordID/oai:dare.uva.nl:publications%2Fb9ce1224-6ad2-4370-aaed-5372afd63970

- Brody, A. 2021. Youth, Voice and Development. A Research Report by the British Council and Changing the Story. Leeds: University of Leeds.

- Buckler, A., L. Chamberlain, F. Mkwananzi, C. Dean, and O. Chigodora. 2021. “Out-of-School Girls’ Lives in Zimbabwe: What Can We Learn from a Storytelling Research Approach.” Cambridge Journal of Education. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764X.2021.1970718.

- Chamberlain, L., A. Buckler, and F. Mkwananzi. (in press). “Chapter 3: Building a Case for Inclusive Ways of Knowing through a Case Study of a Cross-Cultural Research Project of out-of-School Girls’ Aspirations in Zimbabwe: Practitioners’ Perspectives.” In Thinking Critically and Ethically about Research for Education: Engaging with Voice and Empowerment in International Contexts, edited by A. Fox, H. Busher, and C. Capewell, XX. London: Routledge.

- Charaf, A. 2019. Youth and Changing Realities: Perspectives from Southern Africa. Zimbabwe: UNESCO Lighthouse Print.

- Cin, F. M. 2017. Gender Justice, Education and Equality: Creating Capabilities for Girls’ and Women’s Development. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Cin, F. M., and R. Süleymanoğlu-Kürüm. 2020. “Participatory Video as a Tool for Cultivating Political and Feminist Capabilities of Women in Turkey.” In Participatory Research, Capabilities and Epistemic Justice: A Transformative Agenda for Higher Education, edited by M. Walker and A. Boni, 165–188. Camden: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Cooke, P., and I. Soria-Donlan, eds. 2019. Participatory Arts in International Development. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Cooper, A., S. Swartz, and A. Mahali. 2019. “Disentangled, Decentred and Democratised: Youth Studies for the Global South.” Journal of Youth Studies 22 (1): 29–45. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2018.1471199.

- Cuervo, H., A. Miranda. 2019. “Youth in the Global South: An Introduction.” In : Cuervo H., Miranda A. (eds), Youth, Inequality and Social Change in the Global South. Perspectives on Children and Young People, vol 6. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-3750-5_1

- DeJaeghere, J. 2018. “Girls’ Educational Aspirations and Agency: Imagining Alternative Futures through Schooling in a Low-Resourced Tanzanian Community.” Critical Studies in Education 59 (2): 237–255. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17508487.2016.1188835.

- Dzimiri, C., P. Chikunda, and V. Ingwani. 2017. “Causes of Child Marriages in Zimbabwe: A Case of Mashonaland Province in Zimbabwe.” International Journal of Management & Social Sciences 7 (1): 73–83.

- Gwindingwe, G., L. Alfandika, and N. D. Chateuka. 2019. “The Tonga People of Northern Zimbabwe: An Encounter with Digital Media.” African Journalism Studies 39: 1–4. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/23743670.2018.1533487.

- Gwirayi, P., and A. Shumba. 2011. “Children’s Rights: How Much Do Zimbabwe Urban Secondary School Pupils Know?” The International Journal of Children’s Rights 19 (2): 195–204. doi:https://doi.org/10.1163/157181810X513199.

- Gyasi Obeng, S. 2000. “Speaking the Unspeakable: Discursive Strategies to Express Language Attitudes in Legon (Ghana) Graffiti.” Research on Language & Social Interaction 33 (3): 291–319. doi:https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327973RLSI3303_3.

- Henn, M., and N. Foard. 2014. “Social Differentiation in Young People’s Political Participation: The Impact of Social and Educational Factors on Youth Political Engagement in Britain.” Journal of Youth Studies 17 (3): 360–380. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2013.830704.

- Johnson, F., E. Fryer-Smith, C. Phillips, L. Skowron, O. Sweet, and R. Sweetman. 2009. Raising Young People’s Higher Education Aspirations: Teachers’ Attitudes. London: Department for Innovation, Universities and Skills.

- Leavy, J., and S. Smith. 2010. “Future Farmers: Youth Aspirations, Expectations and Life Choices.” FAC Discussion Paper 013, Brighton: Future Agricultures Consortium. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1759-5436.2012.00374.x

- Luebker, M. 2008. “Employment, Unemployment and Informality in Zimbabwe: Concepts and Data for Coherent Policy-Making.” Issues Paper No. 32 and Integration Working Paper No. 90 (Harare and Geneva, ILO).

- Marovah, T., and F. Mkwananzi. 2020. “Graffiti as a Participatory Method Fostering Epistemic Justice and Collective Capabilities among Rural Youth: A Case Study in Zimbabwe.” In Participatory Research, Capabilities and Epistemic Justice: A Transformative Agenda for Higher Education, edited by M. Walker and A. Boni, 215–241. Camden: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Masarurwa, H. 2018. “Youth Participation in Governance and Structural Economic Transformation in Zimbabwe.” African Journal of Stability & Development 11 (1): 71–97.

- Mashingaidze, T. M. 2013. “Beyond the Kariba Dam Induced Displacements: The Zimbabwean Tonga’s Struggles for Restitution, 1990s–2000s.” International Journal on Minority and Group Rights 20 (3): 381–404. doi:https://doi.org/10.1163/15718115-02003003.

- Maunganidze, F., D. Bonnin, and S. Ruggunan. 2021. “Economic Crisis and Professions: Chartered Accountants in Zimbabwe.” SAGE Open, 11(1), 1–14.

- Mkwananzi, F. 2019. Higher Education, Youth and Migration in Contexts of Disadvantage: Understanding Aspirations and Capabilities. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Mkwananzi, F., and F. M. Cin. 2020. “From Streets to Developing Aspirations: How Does Collective Agency for Education Change Marginalised Migrant Youths’ Lives?” Journal of Human Development and Capabilities 21 (4): 320–338. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/19452829.2020.1801609.

- Musizvingoza, R., and N. N. Wekwete. 2018. “Factors Facilitating Risky Sexual Behaviour among Youth in Mufakose, Harare, Zimbabwe.” African Population Studies 32 (1): 3903–3916.

- Nhapi, T., and T. Mathende. 2019. An Exploration of Domains towards Unlocking Zimbabwean Youths’ Socio-Economic and Political Empowerment. Ottawa, Canada: Institute of African Studies Carleton University.

- Ndlovu-Gatsheni, S. 2017. “Decolonizing Research Methodology Must Include Undoing Its Dirty History.” Accessed October 25 2020. https://theconversation.com/decolonising-research-methodology-must-include-undoingits-dirty-history-83912

- Paat, Y.-F. 2016. “Life Course, Altruism, Rational Choice, and Aspirations in Social Work Education.” Research Papers in Education 31 (2): 234–253. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2015.1027725.

- Phillips, A. 2003. “Recognition and the Struggle for Political Voice.” In Recognition Struggles and Social Movements: Contested Identities, Agency and Power, edited by B. Hobson, 263–273. Cambridge:Cambridge University Press.

- Ross, J., ed. 2016. “Sorting It All Out.” In Routledge Handbook of Graffiti and Street Art, 1–10. New York: Routledge.

- Rusvingo, S. L. 2015. “The Zimbabwe Soaring Unemployment Rate of 85%: A Ticking Time Bomb Not Only for Zimbabwe but the Entire SADC Region.” Global Journal of Management and Business Research 14 (9): 1–8.

- Saidi, U. 2019. “African Heritage Isn’t ‘Dead’: Glitches in Organizing Knowledge and Memories with a Focus on the BaTonga in Zimbabwe.” In Handbook of Research on Advocacy, Promotion, and Public Programming for Memory Institutions, edited by Patrick Ngulube. 314–333. Hershey, PA: IGI Global.

- Sandoval, E. 2016. “Music in Peacebuilding: A Critical Literature Review.” Journal of Peace Education 13 (3): 200–217. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17400201.2016.1234634.

- Santos, B. D. S. 2016. “Epistemologies of the South and the Future.” From the European South: A Transdisciplinary Journal of Postcolonial Humanities 1: 17–29.

- Sen, A. 1992. Inequality Re-Examined. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Sen, A. 1999. Development as Freedom. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Sen, A. 2009. The Idea of Justice. London: Allen Lane & Harvard University Press.

- Shephard, M., and S. Patrikios. 2013. “Making Democracy Work by Early Formal Engagement? A Comparative Exploration of Youth Parliaments in the EU.” Parliamentary Affairs 66 (4): 752–771. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/pa/gss017.

- Staeheli, L. A., K. Attoh, and D. Mitchell. 2013. “Contested Engagements: Youth and the Politics of Citizenship.” Space and Polity 17 (1): 88–105. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13562576.2013.780715.

- Tikly, L., and A. M. Barrett, eds. 2013. Education Quality and Social Justice in the Global South: Challenges for Policy, Practice and Research. London: Routledge.

- Tzifakis, N. 2011. “Problematizing Human Security: A General/Contextual Conceptual Approach.” Southeast European and Black Sea Studies 11 (4): 353–368. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14683857.2011.632539.

- Vogel, B., C. Arthur, E. Lepp, D. O’Driscoll, and B. T. Haworth. 2020. “Reading Socio-Political and Spatial Dynamics through Graffiti in Conflict-Affected Societies.” Third World Quarterly 41 (12): 2148–2168. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2020.1810009.

- Walker, M., C. Martinez-Vargas, and F. Mkwananzi. 2020. “Participatory Action Research: Towards (Non-Ideal) Epistemic Justice in a University in South Africa.” Journal of Global Ethics 16 (1): 77–94. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17449626.2019.1661269.

- Walker, M., and F. Mkwananzi. 2015. “Challenges in Accessing Higher Education: A Case Study of Marginalised Young People in One South African Informal Settlement.” International Journal of Educational Development 40: 40–49. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2014.11.010.

- Walker, W., and A. Boni, eds. 2021. Participatory Research, Capabilities and Epistemic Justice: A Transformative Agenda for Higher Education. Camden: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Wheeler, J. 2018. “Troubling Transformation: Storytelling and Political Subjectivities in Cape Town, South Africa.” Critical African Studies 10 (3): 329–344. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/21681392.2019.1610011.

- Williams, G. 2004. Towards a repoliticization of participatory development: Political capabilities and spaces. Participation from tyranny to transformation, edited by S. Hickey and G. Mohan, 92-103. London: Zed Books.

- Wolff, J., and A. De-Shalit. 2013. “On Fertile Functionings: A Response to Martha Nussbaum.” Journal of Human Development and Capabilities 14 (1): 161–165. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/19452829.2013.762177.

- Wood, B. E. 2012. “Crafted within Liminal Spaces: Young People’s Everyday Politics.” Political Geography 31 (6): 337–346. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2012.05.003.

- Young, A. 2010. “Negotiated Consent or Zero Tolerance? Responding to Graffiti and Street Art in Melbourne.” City 14 (1-2): 99–114. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13604810903525215.

- Zihnioğlu, Ö. 2019. “The Prospects of Civic Alliance: New Civic Activists Acting Together with Civil Society Organizations.” VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 30 (2): 289–299. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-018-0032-9.

- Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency (ZIMSTAT). 2012. “Poverty and Poverty Datum Line Analysis in Zimbabwe.” https://www.undp.org/content/dam/zimbabwe/docs/Governance/UNDP_ZW_PR_Zimbabwe%20Poverty%20Report%202011.pdf