Abstract

This article examines the implications of the rise of new powers in the Global South for a central principle of global order: the distinction between the ‘North’ and the ‘South’, or ‘developed’ and ‘developing countries’, that emerged in the second half of the twentieth century. In doing so, we assess whether, and if so, how, the increasing tension between the binary ‘North–South’ distinction and growing heterogeneity within the Global South – as evidenced by the rise of emerging economies – has been reflected in the rules of multilateral trade policymaking. In the case of the World Trade Organization (WTO), the ‘North–South’ categorisation forms the basis of the legal principle of Special and Differential Treatment (SDT) that grants special rights to developing countries. To trace the evolution of SDT, we analyse legal developments and processes of contestation based on our conceptualisation of possible options for adaptation: graduation, individualisation and fragmentation. Drawing on a dataset of WTO decisions and agreements from 1995 to 2019, we find that the group of developing countries increasingly competes with other groups of disadvantaged countries for equity-based differential treatment. The resulting fragmentation contributes to the unmaking of the North–South distinction as a central ordering principle in global trade politics.

The growing economic importance of emerging powers such as Brazil, India and China is altering the balance of power in international politics. Whether or not the power shift towards emerging countries represents a fundamental challenge to the Western norms that shape global order is a question that has received significant scholarly attention (Nölke et al. Citation2015; Ikenberry Citation2018; Mearsheimer Citation2019). Simultaneously, the shift in power from the North Atlantic to the Pacific Rim has affected the architecture of global politics in more subtle ways that have received less attention in political science: scholars from political geography and related disciplines claim that the rise of new centres of economic gravity has begun to erode the distinction between the ‘North’ and the ‘South’, or ‘developed’ and ‘developing countries’, as a central structuring principle that emerged in the second half of the twentieth century (Farias Citation2019; Alami and Dixon Citation2020, 3).

This binary differentiation has – in various manifestations – served as a significant ordering principle of world politics since around the 1960s. It has, for instance, become deeply embedded in the architecture of international institutions such as the World Bank, the World Trade Organization (WTO) and the United Nations Convention on Climate Change. What is notable is that all of these institutions grant special rights to developing as opposed to developed country members, such as access to non-concessional loans or climate-related funds, or less extensive obligations and greater flexibility regarding regime-specific goals. They thus count as what we refer to as equity-based differentiation, which grants disadvantaged countries – in this case developing countries – special rights.

The emergence of economically powerful players in the Global South, however, sits uneasily with a division of the world into a ‘developed North’ and a ‘developing South’. While the binary structure of the North–South categorisation has always been an oversimplification (Eckl and Weber Citation2007), the growing role of countries such as China, India or Saudi Arabia as aid donors has put further strain on the distinction (Sidaway Citation2012, 55). Alami and Dixon (Citation2020, 3) observe the ‘partial breakdown of the North/South axis which has structured much of the thinking and practice in world politics over the past 80 years’. Farias (Citation2019, 1) even claims that the ‘the label “developing” will increasingly become analytically useless’. Against this backdrop, this article seeks to assess how the proclaimed irrelevance of the North–South distinction in world politics manifests itself at the level of issue-specific global governance. The basic expectation is that established powers demand a greater recognition of the ‘in-between’ position of emerging economies.

Our empirical analysis focuses on the case of the WTO. The global trade regime is selected as a case in which the ‘North–South’ distinction has played a prominent role in the past decades: one of its core principles is Special and Differential Treatment (SDT) for members that are classified as ‘developing countries’ as opposed to ‘developed country’ members. This principle was introduced in the world trade regime in the 1960s to counterbalance demands for trade liberalisation with the special needs of developing countries, given their disadvantageous position in the world economy. To achieve this, developing countries receive flexibilities and exemptions from trade liberalisation commitments, while developed countries supposedly provide developing countries with more favourable access to their own markets. However, in the past decade, developed country members of the WTO – and in particular the United States (US) – have increasingly called for a reform of differential treatment. This is because the US and other major developed country members are unwilling to grant special rights to countries such as China, India and Brazil that traditionally belong to the group of developing country members. In 2017, US Trade Representative Lighthizer prominently complained at the WTO that ‘[t]here is something wrong, in our view, when five of the six richest countries in the world presently claim developing country status’ (Lighthizer Citation2017).

To assess the evolution of the SDT principle in response to these pressures for adaptation to global power shifts, we develop a conceptual framework that portrays three main pathways in which differentiation based on the North–South distinction could evolve in a multipolar era: graduation of some developing countries from developing to developed country status; the individualisation of special rights within the developing country group; or the fragmentation of differential treatment, i.e. a scenario in which special rights are no longer granted for ‘developing countries’ in general, but instead reserved for specific sub-groups of them. We expect that the outcome depends both on the costs of granting differential treatment to emerging economies and the (dis)continued legitimacy of using the binary ‘North–South’ distinction to differentiate among WTO members. We assess changes across two distinct time periods: 1995–2008 and 2009–2019. In terms of methods, we combine the analysis of legal changes to the SDT principle with a constructivist focus on processes of contestation that emphasise the unstable and constantly changing legitimacy conceptions that underpin principles of global order (Hurrell Citation2007). In terms of primary sources, we draw on all WTO decisions and agreements concluded between 1995 and 2019 as well as a set of five interviews conducted in Geneva in October 2019 with trade officials and trade experts.

We find that the North–South distinction loses traction as an ordering principle to differentiate between ‘advantaged’ and ‘disadvantaged’ members of the WTO in the past decade. In the first time period (1995–2008), the North–South distinction remains fairly central to WTO trade policymaking. This changes in the second time period (2009–2019), when the emerging countries’ developing country status becomes a central issue of conflict and contestation in the WTO. While differential treatment for developing countries as such retains its centrality, the polarised and unresolved debates about the possible reform of the SDT principle lead to fragmentation as an outcome. WTO members have so far failed to adjust the North–South distinction in a way meaningful to the new power realities. This facilitates the rise of competing sub-groups of developing countries – in particular the Least Developed Countries (LDCs) – that claim SDT. Taken together, these developments contribute to the unmaking of the North–South distinction as a central ordering principle of multilateral trade policymaking.

These findings shed new light on debates about the implications of the rise of emerging powers for global governance. Much of the existing literature focuses on the question of whether or not the power shift to new economic and political players – most notably Brazil, India and China – presents a fundamental challenge to Western norms – so far with contradictory assessments (Ikenberry Citation2018; Mearsheimer Citation2019). We add to this debate by highlighting a more subtle shift in global politics: the erosion of the geopolitical division of the world into the ‘North’ and the ‘South’ or ‘developed’ and ‘developing countries’, and how this has affected global governance. This allows us to, first, correct a bias in the existing literature that relates the implications of the shifting balance of power for global governance to the liberal international order (Ikenberry Citation2018) – rather than to ordering principles that are linked to equity-based differentiation. Second, we add to the growing literature on differentiation and hierarchy in international relations that emphasises that status considerations shape and structure interstate relations (Lake Citation2009; Bukovansky et al. Citation2012; Donnelly Citation2012; Zarakol Citation2017) by showing how the ‘developing country’ status shapes state hierarchies (and how this changes over time). Lastly, our research contributes to the issue-specific existing literature on SDT in the world trade regime. We challenge the prevailing assessment that differential treatment of developing countries moves towards individualisation in the WTO (Pauwelyn Citation2013) by uncovering how differentiation rather becomes fragmented over time.

The rest of the article is structured as follows: first, we present our conceptual framework for assessing the changing nature of what we refer to as equity-based differentiation. The subsequent empirical analysis highlights the changing nature of differential treatment for developing countries in the trade regime and examines our argument of increasing fragmentation via a narrower focus on narrower sub-groups of developing countries. In the conclusion, we reflect on broader implications of our argument.

Differentiation in world politics: reconceptualising the North–South distinction in a multipolar world

The binary distinction between the ‘North’ and the ‘South’ has been a central ordering principle in world politics since decolonialisation (Eckl and Weber Citation2007). It is associated with the categorisation of states as either ‘developed’ or ‘developing’ countries. However, the rise of emerging economies increasingly blurs this binary distinction. Within the existing literature, scholars examine whether the power shift towards emerging countries presents a fundamental challenge to Western norms – so far with contradictory assessments. While some project the demise of the existing global order or a major turn in globalisation (Pieterse Citation2011), others emphasise continuity and the integrative potential of rising powers (Stephen Citation2014; Ikenberry Citation2018). However, there is so far little scholarship on how hierarchical ordering principles, such as the North–South distinction, have changed in response to the rise of new powers in the Global South. Against this background, we develop a conceptual framework to assess the evolution of the differentiation between the rights and obligations of states based on the North–South distinction. We see three main ideal-typical options for adaptation in the light of growing heterogeneity within the group of developing countries: graduation, individualisation or fragmentation of differential treatment for developing countries.

Differentiation and hierarchy in world politics

Our conceptual framework builds on the work of scholars who write about differentiation and hierarchy in international relations (Lake Citation2009; Bukovansky et al. Citation2012; Donnelly Citation2012; Zarakol Citation2017; Viola Citation2020). Common to these theoretical approaches is the assumption that the international level at which state interaction takes place is not ‘anarchical’ in the sense that no higher authority, and hence no rule-based system, exists – a neo-realist claim. As observed by Viola (Citation2020, 12), there are – despite anarchy – ‘many different types of hierarchical relations that can exist in world politics’. States, however, cannot simply claim to hold a particular status; they depend on ‘the collective imposition and recognition of the particular status the object or person holds’ (Bjola and Kornprobst Citation2010, 11). In these ways, power relations and hierarchies are at least in part dependent upon social construction. In line with this body of literature, we understand principles of differential treatment for ‘developing’ as opposed to ‘developed’ countries as partly socially constituted structures that are inherently political and concern power relations (Zarakol Citation2017, 3).

Status ascriptions – such as the ‘North’ and the ‘South’ – thus potentially (re)create structures of global order. In other words, the rules that define status in international cooperation and conflict do not merely reflect existing power relations but hold the potential to (re)create hierarchies, as they can grant differential rights and obligations to different groups of states. This process has been referred to as stratification – the reproduction or transformation of unequal power relations among states through the assignment of differentiated social roles and responsibilities (Albert, Buzan, and Zürn Citation2013, 6). A common focus of this literature has been on how stratification reinforces hierarchical relations by producing ‘categories of super- and subordination’ (Viola Citation2020, 71). Along these lines, status ascriptions of ‘developing’ versus ‘developed’ countries have been seen as ways to reiterate hierarchical relationships (Escobar Citation2011).

What has been largely overlooked, however, is how status ascriptions may also serve as a basis for mitigating existing power hierarchies. In many international institutions, for instance, ‘developing’ countries hold special rights, while those that are considered ‘developed’ are assigned special responsibilities. Along these lines, Fehl and Freistein (Citation2020) recently advocated for a research agenda that focuses on how international organisations can reproduce, but also transform, inequalities among their members. Building on these insights, we develop a conceptualisation of developing country status as a basis for equity-based differentiation in the following section.

Equity-based differentiation: special rights of disadvantaged regime members

We conceptualise equity-based differential treatment as an ordering principle that (a) differentiates between groups of states that are understood to be in a more advantageous position than the members of the other group; and (b) stipulates that those perceived to be in a less advantageous position are given more extensive rights, and/or those perceived to be in a more advantageous position are given more extensive obligations. There is thus a constitutive dimension – who counts as ‘disadvantaged’ or ‘advantaged’ country in a particular regime – as well as an instrumental dimension – what are the differential rights and obligations that follow from one or the other status?

Moreover, differentiation is equity-based because its goal is to provide ‘disadvantaged’ countries more favourable treatment compared to ‘advantaged’ countries. Notably, the gains associated with the developing country status are material in nature, since the special rights granted to ‘disadvantaged countries’ commonly result in less extensive obligations, more implementation-related flexibilities and/or access to financial assistance (compare Rajamani Citation2006). We thus emphasise what Viola (Citation2020, 19) refers to as the ‘material side of status’, rather than the social side of status (Paul, Larson, and Wohlforth Citation2014). The latter sees social considerations about prestige as a driving force to obtain a higher status rank in world politics. In the case of equity-based differential treatment principles, however, a lower social status, ie that of a developing country member, can be used strategically to secure special rights and greater access to resources.

Since the developing country status is associated with material gains, it matters what group of countries counts as disadvantaged or advantaged. In this regard, we build on Rajamani (Citation2008, 926), who highlights three distinct legal approaches that are commonly used in international organisations to determine the status of ‘disadvantaged’ regime members: the definition, list and auto-election approaches. The definition approach relies on benchmarks to determine who counts as a developing country, while the list approach lists ‘categories of Parties, based on which differentiation between them can be effected’ (Rajamani Citation2008, 926); both approaches may come with criteria for graduation according to which country status can be adjusted. Finally, the auto-election method does not rely on objective criteria but allows countries to decide for themselves what category they belong to. The world trade regime follows an auto-election approach that allows countries to self-designate who counts as a developing member of the WTO and, hence, an SDT beneficiary.

The history of differentiation in the world trade regime

In the trade regime, equity-based differentiation in favour of developing countries was firmly established before the creation of the WTO in 1995. Already in the 1950s, minor exemptions from core treaty obligations for the purposes of economic reconstruction were included in the WTO’s predecessor, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT). The pluralisation of international politics as a result of the ongoing processes of decolonisation then allowed for the increased incorporation of a developmental focus in the trade negotiations of the 1960s and 1970s (Lamp Citation2017),Footnote1 including exemptions from liberalisation commitments and preferential market access for developing countries. The emergence of preferential trading schemes for developing countries, such as the US’ Generalized System of Preferences (1974) or the European Communities’ Lomé Convention (1976), for instance, allowed for unilateral market opening that benefitted developing countries within the framework of the GATT. These forms of SDT for developing countries were rendered permanent in 1979 with the addition of the Enabling Clause to the GATT.Footnote2

Once institutionalised, demands for reform of the SDT principle began to appear. The differing economic trajectories of developing countries in the 1980s – exemplified by the failure of import substitution industrialisation in Latin America and high growth rates in East Asian Newly Industrialised Countries – resulted in a partial rethinking of exemptions as useful policy tools for developing countries. With increasingly neoliberal loan requirements being used by international financial institutions during this period, a new type of developing country trade policy emerged that promoted greater integration of smaller economies into the global market (Easterly Citation2001). These developments explain – at least in part – the changing format of SDT during the Uruguay Round (1986–1994) talks: a retooling of differential treatment away from exemptions and towards integrative measures such as differentiated transition schedules and pledges of technical assistance. However, SDT remained contested, as developing countries claimed that these special rights also failed to be effective in addressing the disadvantaged structural position of developing countries in the first place.

While equity-based differential treatment was thus already subject to contestation in trade diplomacy before the rise of Brazil, India, China and other emerging economies, this more recent global power shift created new uncertainties about SDT as a core principle of the WTO-centred multilateral trading system.

Tracing the evolution of the North–South distinction in a multipolar era

Our basic assumption is that the binary distinction between ‘developed’ and ‘developing countries’ (as a group) as a constitutive basis for equity-based differentiation has come under pressure to adapt in a multipolar world. In particular, emerging economies fall increasingly between the two camps. Given the material benefits associated with the developing country status that Brazil, India and China traditionally hold, established powers have long demanded that emerging economies give up (some of) their special rights as developing countries in international regimes. These countries are increasingly seen as competitors, rather than disadvantaged regime members. Our conceptual framework thus reverses the assumptions of power transition theory, namely that established rather than emerging powers resist adaptation to safeguard their own institutional privileges (Daßler et al. Citation2019). How differentiation is adapted to this increasing heterogeneity within the Global South, however, can unfold in different ways.

Against this background, we develop a conceptualisation of three ideal-typical pathways that capture how the North–South distinction – as its constitutive basis – may be adapted in the light of global power shifts: graduation, individualisation and fragmentation. All three have in common that they respond to the increasing pressure on the status quo, i.e. a status quo that allows emerging economies to claim the same special rights as other developing countries. They differ, however, in terms of the extent to which they replace or retain the ‘North–South’ distinction as the central ordering principle of world politics.

In the first option, graduation, emerging economies graduate from their status as developing countries, which results in a shrinking of the group of developing countries that have access to differential treatment. Emerging economies thus lose all access to special rights for developing countries. The binary distinction between ‘developed’ and ‘developing countries’, however, remains largely intact. In the second option, individualisation, the developed/developing country distinction also remains central for differentiation. However, developing countries are not treated as a homogeneous group anymore. Instead, special rights are individualised across developing countries to take into account their (increasingly) diverging capacities. Emerging economies thus do not lose special rights as developing country members, but receive less extensive rights as compared to developing countries with fewer capacities. In the third option, fragmentation, equity-based differentiation becomes increasingly fragmented in the sense that narrower sub-groups of developing countries gain prominence and compete with each other for differential treatment.Footnote3 Special rights are thus no longer granted for ‘developing countries’ in general, but instead specific sub-groups compete over access to them. If these other sub-groups become central for differentiation, we can speak of the unmaking of the North–South distinction in global governance in a given regime.

To unpack whether differential treatment for developing countries is changing in the WTO, and which of the three ideal-typical pathways prevails, we analyse WTO decisions and agreements published since 1994. As a first step, we examine whether equity-based differentiation continues to matter by exploring the share of WTO decisions and agreements that allows for differential treatment for developing countries. We then explore whether adaptation has taken place, and which of the three pathways prevails. We examine whether developing countries are treated as a homogeneous group, or whether their special rights are increasingly individualised in line with their respective capacities. To analyse potential fragmentation, we assess whether competing ordering principles are emerging that focus on a different group of beneficiaries among developing country members that receive differential treatment. A focus on the group of LDCs stands for an alternative ordering principle that pits only the economically weakest segment of the international community against all other WTO members. Lastly, we assess whether we observe a shift towards the graduation of emerging economies from developing country status.

In our empirical analysis, we compare two separate periods of policymaking, 1995–2008 and 2009–2019, in order to trace possible shifts in differential treatment. These two time periods roughly divide the WTO era into a first ‘decade’ and a second ‘decade’ of policymaking. The second time period demarcates more clearly the shift towards a multipolar world, which is likely to increase pressure on adjusting the pre-existing binary differentiation scheme. The year 2008 was chosen as cut-off because the financial crisis is commonly seen as a turning point after which the new realities of a multipolar world became apparent, since emerging economies were more resilient throughout the crisis (see eg Christensen Citation2015; Pu Citation2017).

The unmaking of the ‘North–South’ distinction in the WTO: from great expectations to fragmentation

This section traces the evolution of the SDT principle in the WTO era by analysing how equity-based differential treatment has changed over two time periods (1995–2008; 2009–2019). Doing so allows us to assess whether and how the proclaimed erosion of the ‘North–South’ framework due to the rise of emerging powers has led to graduation, individualisation or fragmentation. We show that while the North–South distinction remains relatively unchanged in the first time period, the second time period is characterised by increasing fragmentation.

The status quo: equity-based differentiation in the world trade regime

The relevance of the North–South distinction in the WTO is exemplified by the principle of Special and Differential Treatment for ‘developing’ as opposed to ‘developed’ country members. Under SDT, developing country members have access to exemptions from liberalisation commitments, are allowed longer transition periods in the implementation of these commitments, and may receive financial support. According to the WTO, its agreements contain 178 such differential treatment provisions. With regard to the institutionalisation of equity-based differentiation, two aspects are particularly noteworthy: first, WTO members can self-declare the status they hold (auto-election approach). This allows emerging economies to maintain their claims to special rights. While this approach was established in the 1960s as a means to strengthen South–South solidarity, it remained unchanged when the WTO was founded in 1995. Today, the WTO continues to reiterate that ‘[t]here are no WTO definitions of “developed” and “developing” countries. Members announce for themselves whether they are “developed” or “developing” countries. However, other members can challenge the decision of a member to make use of provisions available to developing countries’ (WTO webpage 2020).

Second, developing countries are primarily treated as a homogeneous group, i.e. all developing countries have access to the same special rights. This approach was informed by the ideological notion of three ‘worlds’ that emerged during the Cold War: the ‘First World’ of capitalist industrialised countries, the ‘Second World’ of communist industrialised countries and the ‘Third World’ of underdeveloped, non-industrialised countries. Taken together, this illustrates that the status quo of equity-based differentiation strongly relies on the binary North–South distinction.

Great expectations (1995–2008): the ‘North–South’ distinction remains central

This first period of multilateral trade policymaking at the WTO is best characterised as one of great expectations. Partly in response to the September 11th attacks, the early 2000s marked a unique moment for a solidaristic approach to global trade policymaking. Expectations were elevated with the launch of the WTO’s Doha Development Round in 2001, the first development-oriented negotiation round in multilateral trade policymaking. The Doha Ministerial Declaration explicitly ‘reaffirm[ed] that provisions for special and differential treatment are an integral part of the WTO Agreements’ (WTO Citation2001, para. 44). This high normative support for differentiation for developing countries as a group helps us to understand the centrality of SDT provisions in WTO decision-making in this earlier time period.

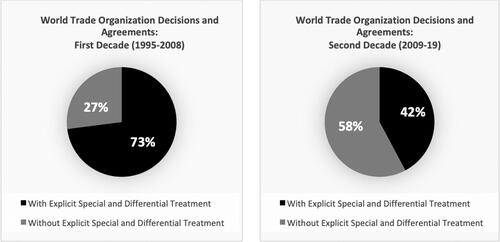

Despite disagreements on how to readjust the existing rules of the trading system in line with a development orientation, we find that the North–South distinction remains central in this initial period of multilateral trade governance. The pattern that emerges from our assessment of legal developments is one of high activity, focused almost exclusively on developing countries as a whole, especially in the early years. The 1990s are dominated by a myriad of agreements that laid the basis for the establishment of the WTO in 1994/1995. What makes the 1994 bundle of legal provisions remarkable is the wide coverage that differential treatment receives at the end of the Uruguay Round: roughly half of all decisions and agreements contain some type of SDT provision. SDT continues to feature prominently in the decisions and agreements reached in later years: out of the 12 agreements and decisions that were reached subsequently, 11 contain SDT provisions. Overall, we see the pervasiveness of the North–South distinction: SDT provisions were included in 73% of Ministerial decisions and agreements (see ).

Figure 1. Centrality of Special and Differential Treatment provisions in World Trade Organization decisions and agreements.Source: authors’ own calculations. Documents were counted as SDT-inclusive if they entailed explicit provisions on differential treatment.

Moreover, there are few signs of adaptation of the binary North–South distinction as a basis for differentiation. Most manifestations of the SDT principle treat developing countries as a homogeneous group. The Agreement on Agriculture, for instance, grants all developing countries a 10% de minimis exemption for the provision of domestic support, while developed countries receive a 5% de minimis. Similarly, transition periods for the implementation of the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights differ in length for developed as opposed to developing country members. An exception to this general rule of treating developing countries as a homogeneous group is the accession of China to the WTO in 2001. Its accession protocol lays down more individualised liberalisation commitments, which fall on average between those of other developed and developing country members. Notably, however, China insisted at the time on joining the WTO as a developing country member.

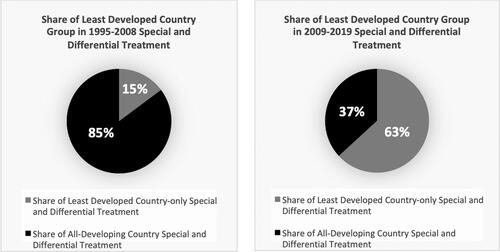

Lastly, there are few signs of fragmentation. The North–South distinction is much more prevalent compared to competing groups of ‘disadvantaged’ WTO members, specifically the group of LDCs: in the initial years, there are only four decisions that limit differential treatment to the group of LDCs compared with a total of 26 legal documents. This share rises slightly in the 2000s, accounting for 25% of differential treatment. Taken together, we find that LDC-only legislation made up only 15% of documents with SDT in the first time period (see ).

Fragmentation of equity-based differentiation (2009–2019): the unmaking of the North–South distinction

In the aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis of 2008/2009, we see that – in contrast to earlier– the momentum of WTO policymaking appears to increase gradually. This development culminates in the conclusion of the WTO era’s first multilateral trade agreement – the Trade Facilitation Agreement – at the Bali Ministerial Conference in 2013. This slight revival of WTO decision-making does not, however, engender a strengthening of SDT. While differentiation as such remains part of the trade regime, its focus evolves considerably and becomes narrower and less central. We thus find that equity-based differentiation becomes increasingly fragmented as emerging economies gain in power.

A first notable development at the legal level is that the SDT principle becomes less central in trade policymaking in this time period. This is manifested in the sharply decreasing relative number of SDT-inclusive decisions and agreements: SDT provisions were included in only around 40% of 2010s legislation (see ) – as opposed to more than 70% in the earlier period. Moreover, the absolute number of documents with explicit SDT provisions also drops from 27 in the first period to 19 in the second decade.

With regard to the substantive evolution of differentiation, we find, first, that calls for adjusting differentiation in line with the option of graduation are increasing significantly, but do not lead to meaningful changes in this direction.

By the late 2010s, critiques of the auto-election approach become central to WTO debates about differentiation. These highly polarised debates primarily pit the US and its traditional ‘Quad’ allies – in particular the European Union and Canada – against emerging countries, and among them most prominently India and China. The former advocate for a reform of differential treatment (WTO Citation2019a); the latter defend the status quo that allows them to self-declare their status. A common thread of the reform proposals is the focus on the option of graduation that would result in shrinking the number of developing country members. According to the criteriaFootnote6 proposed in a US communication to the WTO General Council (WTO Citation2019c), 34 self-declared developing country members of the WTO were to graduate to developed country status. Furthermore, a 45-page US proposal from 2019 explicitly calling for an end to an ‘undifferentiated WTO’ (WTO Citation2019a) questioned the legitimacy of the status quo on the grounds that it had ‘severely damaged the negotiating arm of the WTO’ (WTO Citation2019a, para. 1.8). In a similar vein, a 2018 EU concept paper on WTO modernisation complains ‘the system remains blocked by an antiquated approach to flexibilities which allows over 2/3 of the membership including the world’s largest and most dynamic economies to claim special treatment’ (European Commission Citation2018, 2).

In response to the US memorandum, a group of 52 developing countries – including India and China – submitted a joint statement at the General Council of the WTO in which they defended their status as developing countries (WTO Citation2019d). More recently, a group of emerging economies that self-declare as developing country members tabled a 39-page communication dedicated to their defence of the status quo (WTO Citation2019b). In the communication, China, India, South Africa and Venezuela defend the North–South division as a basis for differentiation:

Despite impressive progress achieved by developing Members since the creation of the WTO, old divides have not been substantially bridged and, in some areas, they have even widened, while new divides, such as those in the digital and technological spheres, are becoming more pronounced. (WTO Citation2019b, para. 1.1)

It is nevertheless notable that the auto-election approach remains unchanged – despite explicit calls for reform from major developed countries and the proclaimed willingness of a (small) number of developing county members to not make use of the status in the future anymore.Footnote7 Emerging economies are thus able to continuously claim their status as developing country members of the WTO.

Instead, the polarised and unresolved debates about reform of the SDT principle have, second, facilitated fragmentation as an outcome: since granting special rights to all developing countries (including emerging countries) as a group has become too costly, we find that newly negotiated differential treatment provisions increasingly focus on narrower, more clearly defined sub-groups among developing country members. This trend is most notably the case regarding differential treatment in favour of the group of LDCs. We find an increase in LDC-only SDT, which implies that if differential treatment provisions are contained in WTO decisions and agreements, they are increasingly limited to the narrow developing country sub-group of LDCs: while such ‘LDC-only’ legislation made up only 15% of documents with SDT in the first time period, by the 2010s this subset of provisions accounted for more than 60% of all SDT-inclusive publications (see ). In the last 10 years LDCs have thus become the primary beneficiaries of new differential treatment provisions, and this trend accelerates dramatically in the 2010s. In contrast to the category of developing country members, membership in the LDC group does not follow the principle of auto-election but derives from a set of clearly defined United Nations (UN)-authorised criteria.Footnote8

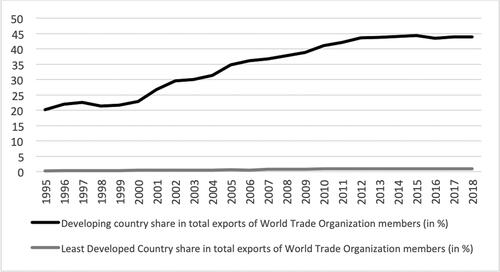

The shift towards LDCs also implies a significant shrinking of the range of beneficiaries of differential treatment and thus has significant distributional consequences. While developing countries’ share of aggregate exports among WTO members was only around 20% when the WTO was created, it has in the meantime more than doubled (to more than 40%) (see ). Granting SDT to all WTO members that self-declare as developing country members has thus become increasingly costly. This partly explains the reluctance of developed country members to maintain the status quo of granting SDT to all (self-declared) developing country members. As emphasised by a WTO official in Geneva in an interview,

Figure 3. Share of Least Developed Country and developing country exports in total exports of World Trade Organization members.

China, India, Brazil, but also now more advanced economies like South Korea and Singapore, they have been treated as developing countries ever since and developed members, they are less willing to recognise the need for S&D [SDT] by these countries. And that is also the main reason why the negotiations on S&D, they have stalled over the last years because there is no differentiation among developing countries in these negotiations on S&D and …. in all negotiations, the developed members are not willing to give the same S&D to all developing countries if it’s significant S&D. (Interview 1, 28 October 2019)

The reluctance of emerging economies to graduate from the developing country status has thus in part facilitated the shift towards LDCs-only SDT, as it renders granting SDT to all self-declared developing country members too costly or ‘significant’.

Conversely, the graduation criteria built into the LDC status ensure that the group remains marginal over time – at around 1% of aggregate exports of WTO members (see ). This makes it much less costly – and contested – to grant SDT. This was echoed in the following statement by the same WTO official, who claimed that ‘LDCs, … in terms of world trade they account for less than … about 1% of world exports, so it’s relatively easy for other members to make concessions to the LDCs’ (Interview 1, 28 October 2019). Another trade expert similarly claimed that the focus on LDCs ‘is also a strategy, an acceptance by the richer WTO members to not allow SDT for anyone else than LDCs’, adding that ‘developed countries are less willing to grant SDT to countries other than LDCs, because LDCs are not a threat anyway to them’ (Interview 2, 28 October 2019).

While differential treatment for narrower sub-groups can in principle complement differential treatment for developing countries as a group, in this case the shift towards LDCs increasingly contributes to a crowding out of the latter. In this sense, we witness the (gradual) unmaking of the North–South distinction in the world trade regime: WTO negotiations lead to fewer and fewer agreements and decisions that contain equity-based differentiation for developing countries as a group.

While the shift towards LDCs excludes emerging economies such as Brazil, India and China from access to special rights, it also excludes the majority of smaller developing countries from SDT. While roughly two-thirds of the 164 WTO members self-declare as developing country members, only 46 of them qualify as LDCs. The shift towards LDCs thus significantly reduces the number of developing countries that have access to newly negotiated special rights, as it does not only exclude emerging countries (as foreseen in the option of graduation).

The trend towards fragmentation of the beneficiaries of equity-based differentiation is also apparent beyond the group of LDCs. WTO members have also increasingly institutionalised a flurry of other sub-groups that compete with the group of developing countries and LDCs for access to the flexibilities entailed by SDT. These groups include the Article XII members – comprising countries that have recently joined the WTO – as well as Small and Vulnerable Economies (SVEs) and Low-Income Countries in Transition. Similar to LDCs, these alternative sub-groupings rely on a definition approach towards differentiation, which – with the exception of the Article XII group – consists of clear-cut criteria for graduation. While none of these groups has been formally recognised as a sub-category of WTO members so far, they effectively compete with the group of developing countries for differential treatment. The rise of these competing sub-groups arguably further contributes to the unmaking of the North–South distinction as a central ordering principle in the multilateral trade regime. Not only do they compete alongside the developing country members for special rights, but they increasingly crowd out differential treatment for developing countries as a group (see ).

The trend of granting SDT towards narrower, and potentially competing, sub-categories of developing countries both reflects and reiterates increasing divisions among the group of developing countries. As emphasised by a Geneva-based trade expert, the sense of solidarity that prevailed in the 1960s and 1970s among developing countries has decreased, given that ‘that common identity is much weaker today’ (Interview 5, 29 October 2019). Increasingly, developing countries see emerging economies such as China or India not only as leaders of developing country coalitions, but also as competitors for SDT (compare Weinhardt Citation2020, 405). Moreover, the trend towards granting SDT to narrower developing country sub-groups also reflects a certain pragmatism given the politicised deadlock of the Doha Development round negotiations. As emphasised by a trade expert in Geneva,

It is very difficult to come up with solutions which are agreeable to all countries. So that’s why I think that … the trend has been to address those specific problems in a more practical approach …. If you have a problem in terms of agriculture, so let’s address this in terms of transition periods only for SVEs …. So, it’s practical’. (Interview 3, 29 October 2019)

Lastly, there are some legal developments at the margins that indicate the parallel emergence of more individualised approaches as a basis for differentiation. The Trade Facilitation Agreement (TFA, 2014) stands out in this respect because it has developed a novel approach towards differentiation that signifies the most radical departure from the North–South distinction. The TFA has developed a fine-tuned format of categorising differentiation provisions that introduces a list approach that distinguishes not only at the country but also at the sectorial level, and makes differentiation voluntary. It differs from fragmentation because all (self-declared) developing countries – rather than merely narrower sub-groups – can equally claim access to the flexibilities it foresees. It stands for an individualised approach because developing country members can voluntarily self-designate the extent to which they want to make use of what kinds of flexibilities,Footnote9 enabling them to decide on the necessity for – and kind of – differential treatment with regards to implementation. What this scheme effectively does is to move beyond the generalisation of developing countries as a homogeneous bloc and towards a more individualised form of differentiation.

However, it is notable that this individualised approach has so far not been broadened to other areas of the WTO regime. This can partly be explained with the rather unusual constellation of interests regarding SDT in this case. Despite the contested nature of the effectiveness of SDT, the general rationale behind developing country’ claims to special rights remains the assumption that countries at different stages of economic development do not benefit from trade liberalisation measures in the same way. More specifically, countries that are currently at a disadvantaged structural position are expected to benefit from protectionist measures as they integrate into global markets. Longer transition periods to implement WTO obligations – or permanent exemptions from these obligations – are meant to guarantee the policy space necessary to improve a country’s competitiveness before opening up. Yet in the case of the TFA agreement, this common rationale does not apply in a straightforward way: developing countries have little to gain from exemptions from the TFA’s obligations. This is because the agreement is meant to reduce trade costs that stem, for instance, from burdensome border procedures at ports that slow down the import of goods and do not serve a developmental purpose. In principle, the TFA should thus be beneficial to all countries.Footnote4 As a trade representative based in Geneva stated: ‘all countries recognise that improving their customs procedures is beneficial for them’ (Interview 1, 28 October 2019). The potential gains from the TFA for all countries explain in turn why WTO members agreed to an individualised SDT approach that allowed developing countries to self-designate whether or not they need transition periods and financial aid to implement the agreement. The expectation was that developing countries would face few incentives to make use of exemptions to delay the envisaged trade facilitation measures, as long as implementation costs could be covered.Footnote5

It is questionable, however, how far this rationale can be extended to other areas of negotiations in the WTO, in which exemptions or implementation flexibilities are considered important tools to maintain policy space. For instance, in agricultural negotiations, China and India defend their special rights as developing countries (Hopewell Citation2021) and continue to perceive the flexibilities they hold when providing agricultural subsidies as beneficial given the important role that the sector plays for domestic employment and food security. An individualised TFA approach towards SDT that requires larger developing country members to self-designate areas in which they voluntarily give up special rights is thus unlikely to succeed here. A trade representative in Geneva claimed, along these lines, that ‘if you speak about reducing market access barriers, so your own tariffs, your own subsidies, there self-designation is more difficult’ (Interview 1, 28 October 2019).

To sum up, the predominant trend has been – given the absence of graduation or widespread individualisation – the rise of fragmentation of differential treatment for developing countries. In particular, differential treatment is increasingly granted to the narrow-sub group of LDCs, as compared to the entire group of developing countries – that continues to include emerging economies. Inadvertently, this contributes to the unmaking of the North–South distinction as a central ordering principle of global trade politics, since special rights are increasingly tied to the narrow sub-group of LDCs rather than to the developed/developing country categories. This unmaking has significant distributional consequences because in addition to emerging countries, a large number of WTO developing country members are excluded from newly negotiated special rights that are reserved for the marginal group of LDCs only.

Conclusion

This article started from the proclaimed tension between the North–South distinction and the rise of new powers in the Global South (see Farias Citation2019; Alami and Dixon Citation2020). Against this backdrop, we have traced the evolution of the WTO’s central principle of SDT for ‘developing’ as opposed to ‘developed’ countries in the WTO era across two time periods (1995–2008; 2009–2019). This principle is an important example of what we refer to as equity-based differentiation in world politics – a phenomenon largely overlooked by International Relations scholars so far. In the WTO, the North–South distinction as a basis for differentiation came increasingly under pressure with the rise of new powers such as China, India and Brazil. Established powers began to see them as competitors and sought to restrict their access to special rights as developing country members.

The novel conceptual framework we developed then helped us to capture how differential treatment for developing countries has been adapted in light of these global power shifts. We foresaw three ideal-typical pathways for adaptation: graduation of emerging countries from developing to developed country status; the individualisation of special rights within the developing country group; or the fragmentation of differential treatment, where special rights are no longer reserved for ‘developing countries’ in general, but instead specific sub-groups compete for access over them. We find that in the case of the WTO, the evolution of differential treatment for developing countries is characterised by increasing fragmentation, especially in the last decade. These changes become manifest at the legal level: not only does differential treatment become less central to WTO decisions, but it increasingly focuses on competing sub-groups, in particular the group of LDCs. Conversely, emerging countries have resisted graduation, and individualisation occurred only at the margins. This suggests an unmaking of the North–South distinction in the world trade regime in the sense that competing, more differentiated sub-groups of developing countries more successfully claim differential treatment on grounds of being ‘disadvantaged’.

This shift away from equity-based differentiation for all developing countries towards a focus on LDCs as ‘disadvantaged’ regime members has substantial distributional consequences. Not only does it exclude emerging countries from these newly negotiated special rights, but other non-emerging developing countries that have outgrown the LDC category are also not covered anymore. The unmaking of the North–South distinction thus goes hand in hand with a weakening of equity-based differentiation in the world trade regime. It not only matters who the terms ‘developed’ and ‘developing’ country refer to (Eckl and Weber Citation2007), but also whether or not alternative distinctions between disadvantaged and advantaged countries come to shape our understanding of world (trade) politics.

Taken together, these findings shed new light on the implications of the rise of Brazil, India and China for global governance in general, and for the trade regime in particular. Instead of focusing on the implications of their rise for the liberal international order (Ikenberry Citation2018; Mearsheimer Citation2019), we shed light on more subtle, less studied ways in which it affects the differentiated nature of global order: the rise of Brazil, India, China and other emerging economies has contributed to the unmaking of the North–South distinction as central to WTO politics. In its place, we find a scenario of fragmentation, with a focus on narrower sub-groups of developing countries, such as the LDCs, gaining in importance. This echoes the findings in other strands of the literature that a ‘multiplex’ world order is emerging (Acharya Citation2017), with multiple and partially overlapping differentiation principles competing with each other. It also illustrates how the developing country status has become politicised, as who holds it is a question not only of social prestige (Paul, Larson, and Wohlforth Citation2014), but also material benefits. Lastly, our assessment that fragmentation prevails challenges the dominant view in the trade literature that overemphasises the shift towards individualisation that we have seen in the TFA (compare Pauwelyn Citation2013).

The conflict over the status of emerging countries in the WTO has not only undermined the normative underpinnings of SDT, but may also indicate new fissures in global trade diplomacy in the future, as larger developing economies are beginning to face the issue of choosing sides: in the case of Singapore and South Korea, promises in September and October 2019 to refrain from future use of the developing country status have acted as responses to the US-led critique of the current practice of auto-election (Chung and Roh Citation2019; Ministry of Trade and Industry Singapore Citation2019). Brazil has followed suit: similar statements of intent regarding future disuse of developing country rights have consequently been leveraged for US support for Brazilian membership of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development from 2019 onwards (Mano Citation2019). However, since these promises only concern future WTO negotiations, existing benefits under SDT remain seemingly untouched. Nonetheless, increasing divisions that cut across the heterogeneous group of developing country WTO members suggest that coalition building as a strategy to push for the inclusion of development concerns has become more complex. Complementary strategies, such as the forging of narratives around poverty (Narlikar Citation2020) or the emphasis on regional economic integration, may become even more relevant in the future.

Beyond the case of the WTO, our findings also suggest that it will be important to pay more attention to changes in the central ordering principles used to differentiate between groups of states in global governance. Further research is needed to assess how the evolution of the North–South distinction in world politics plays out in the context of other global regimes.

Acknowledgements

We are thankful for comments and suggestions on earlier versions of this article by Evgeny Postnikov, Deborah Barros Leal Farias, Kristen Hopewell, Matthias Kranke, Ilias Alami, Fabian Bohnenberger, Robin Markwica, Angela Geck, Simon Pompé, Talisha Schilder, Klaus Dingwerth, Julian Eckl and Simon Herr. We also thank Farida Hassan and Anna-Lena Braun for excellent research assistance. Moreover, we thank the TWQ editorial team and two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments and suggestions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Clara Weinhardt

Clara Weinhardt is Assistant Professor in international relations at Maastricht University and a Non-Resident Fellow at the Global Public Policy Institute (GPPi) in Berlin. Her research examines global governance and international negotiations, with a focus on North–South relations in trade. Her work has appeared in (among other places) International Studies Quarterly, the Review of International Political Economy, the Journal of Common Market Studies, Routledge’s International Political Economy Series and Routledge’s Global Institutions Series. In 2021, she received the Anthony Deos Young Scholar Award in the Diplomatic Studies Section of the International Studies Association. She holds a PhD in international relations from the University of Oxford.

Till Schöfer

Till Schöfer is a PhD researcher at the Hertie School in Berlin. He holds degrees in international relations and history from the London School of Economics, Sciences Po, Paris and the University of Cambridge. His doctoral thesis interrogates changes in Chinese foreign policy amidst a contemporary crisis of multilateralism. These changes cover EU–China relations, strategic narratives and international aid flows. Further research covers the rights of developing countries in the WTO and the international trade regime more broadly. He works as a researcher at the University of Maastricht in the Netherlands, having previously held research positions at the Hertie School in Berlin and Asia House in London.

Notes

1 The creation of the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development in 1964, moreover, facilitated the growing institutionalisation of a developmental dimension in international trade politics.

2 Note that the Enabling Clause continues to serve as the legal basis for current preferential trading schemes for developing countries, including the EU’s Everything But Arms trading scheme for LDCs, the US’ African Growth and Opportunity Act or preferential trading schemes for LDCs put in place by emerging economies such as China or India.

3 Note that the scenario of fragmentation overlaps with individualisation in the sense that special rights are granted to more individualised sub-groups of developing countries. It differs, however, because rights within each of these sub-groups are not individualised.

4 The proposed criteria are: membership in the Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development or the Group of Twenty, a classification as high-income by the World Bank, and accounting for no less than 0.5% of global merchandise trade.

5 Singapore, Brazil, Republic of Korea, Costa Rica and Chinese Taipei declared they would not use the status in future negotiations (as of May 2021). The concrete implications of these declarations remain unclear.

6 These criteria are a gross national income below USD 1025 per capita; low levels of human assets as defined by the Human Assets Index; and high economic vulnerability, measured by the Economic Vulnerability Index. There are currently only 46 countries that qualify as LDCs.

7 Differentiation is between clauses that they are able to implement immediately after the TFA’s entry into force (Category A), those that they will implement after a transitional period (Category B) and those that can only be implemented after both technical assistance and a transitional period (Category C).

8 Note that this does not imply that gains from the TFA will be distributed equally. Developed countries that have a higher share of world exports are likely to benefit more compared to most developing countries (Wilkinson, Hannah and Scott Citation2014, 1039).

9 China and Brazil, for instance, indeed implemented 94.5% and 95.8% of the TFA’s obligations immediately (Category A), without making use of the possibility of longer transition periods or financial aid. For an overview of the current state of play of the implementation of the TFA, see www.ftadatabase.org.

Bibliography

- Acharya, A. 2017. “After Liberal Hegemony: The Advent of a Multiplex World Order.” Ethics & International Affairs 31 (3): 271–285. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S089267941700020X.

- Alami, I., and A. D. Dixon. 2020. “The Strange Geographies of the ‘New’ State Capitalism.” Political Geography 82: 1–12. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2020.102237.

- Albert, M., B. Buzan, and M. Zürn, eds. 2013. Bringing Sociology to International Relations: World Politics as Differentiation Theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bjola, C., and M. Kornprobst, eds. 2010. Arguing Global Governance: Agency, Lifeworld and Shared Reasoning. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Bukovansky, M., I. Clark, R. Eckersley, R. Price, C. Reus-Smit, and N. J. Wheeler. 2012. Special Responsibilities: Global Problems and American Power. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Christensen, T. J. 2015. The China Challenge: Shaping the Choices of a Rising Power. New York, NY: WW Norton & Company.

- Chung, J., and J. Roh. 2019. “South Korea to Give Up Developing Country Status in WTO talks.” Reuters Business News, October 25. Accessed October 3, 2021. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-southkorea-trade-wto/south-korea-to-give-up-developing-country-status-in-wto-talks-idUSKBN1X401W

- Daßler, B., A. Kruck, and B. Zangl. 2019. “Interactions between Hard and Soft Power: The Institutional Adaptation of International Intellectual Property Protection to Global Power Shifts.” European Journal of International Relations 25 (2): 588–612. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066118768871.

- Donnelly, J. 2012. “The Elements of the Structures of International Systems.” International Organization 66 (4): 609–643. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818312000240.

- Easterly, W. 2001. “The Lost Decades: Developing Countries’ Stagnation in Spite of Policy Reform 1980-1998.” Journal of Economic Growth 6(2): 135–157.

- Eckl, J., and R. Weber. 2007. “North–South? Pitfalls of Dividing the World by Words.” Third World Quarterly 28 (1): 3–23. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01436590601081732.

- Escobar, A. 2011. Encountering Development: The Making and Unmaking of the Third World. Vol. 1. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- European Commission. 2018. WTO Modernisation – Introduction to Future EU Proposals – Concept Note. Brussels: European Commission. Accessed October 3, 2021. https://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/docs/2018/september/tradoc_157331.pdf

- Farias, D. B. L. 2019. “Outlook for the ‘Developing Country’ Category: A Paradox of Demise and Continuity.” Third World Quarterly 40 (4): 668–687. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2019.1573139.

- Fehl, C., and K. Freistein. 2020. “Organising Global Stratification: How International Organisations (Re)Produce Inequalities in International Society.” Global Society 34 (3): 285–303. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13600826.2020.1739627.

- Hopewell, K. 2021. “Heroes of the developing world? Emerging powers in WTO agriculture negotiations and dispute settlement.” The Journal of Peasant Studies, Online First, 1–24.doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2021.1873292.

- Hurrell, A. 2007. On Global Order: Power, Values, and the Constitution of International Society. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Ikenberry, G. J. 2018. “The End of Liberal International Order?” International Affairs 94 (1): 7–23. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/ia/iix241.

- Lake, D. A. 2009. “Hobbesian Hierarchy: The Political Economy of Political Organization.” Annual Review of Political Science 12: 263–283. doi:https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.12.041707.193640.

- Lamp, N. 2017. “The ‘Development’ Discourse in Multilateral Trade Lawmaking.” World Trade Review 16 (3): 475–500. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S1474745616000616.

- Lighthizer, R. 2017. Opening Plenary Statement of United States Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer at the WTO Ministerial Conference [Online transcript]. Accessed October 3, 2021. https://ustr.gov/about-us/policy-offices/press-office/press-releases/2017/december/opening-plenary-statement-ustr

- Mano, A. 2019. “‘Brazil’s New Status Would Not Affect Prior AG Commitments: WTO Chief.” Reuters Business News, March 20. Accessed October 3, 2021. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-brazil-trade/brazils-new-status-would-not-affect-prior-ag-commitments-wto-chief-idUSKCN1R12NW

- Mearsheimer, J. J. 2019. “Bound to Fail: The Rise and Fall of the Liberal International Order.” International Security 43 (4): 7–50. doi:https://doi.org/10.1162/isec_a_00342.

- Ministry of Trade and Industry Singapore. 2019. Singapore Reaffirms Commitment to Work with Like-Minded Partners to Strengthen the World Trade Organization. Singapore: Ministry of Trade and Industry Singapore. Accessed October 3, 2021. https://www.mti.gov.sg/-/media/MTI/Newsroom/Press-Releases/2019/09/SDT-press-release.pdf

- Narlikar, A. 2020. Poverty Narratives and Power Paradoxes in International Trade Negotiations and Beyond. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Nölke, A., T. ten Brink, S. Claar, and C. May. 2015. “Domestic Structures, Foreign Economic Policies and Global Economic Order: Implications from the Rise of Large Emerging Economies.” European Journal of International Relations 21 (3): 538–567. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066114553682.

- Paul, T. V., D. W. Larson, and W. C. Wohlforth, eds. 2014. Status in World Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Pauwelyn, J. 2013. “The End of Differential Treatment for Developing Countries? Lessons from the Trade and Climate Change Regimes.” Review of European, Comparative & International Environmental Law 22 (1): 29–41. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/reel.12017.

- Pieterse, J. N. 2011. “Global Rebalancing: Crisis and the East–South Turn.” Development and Change 42 (1): 22–48. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7660.2010.01686.x.

- Pu, X. 2017. “Controversial Identity of a Rising China.” The Chinese Journal of International Politics 10(2): 131–149.doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/cjip/pox004

- Rajamani, L. 2006. Differential Treatment in International Environmental Law. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Rajamani, L. 2008. From Berlin to Bali and beyond: killing Kyoto softly? International & Comparative Law Quarterly, 57(4), 909–939. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S002058930800064X

- Sidaway, J. D. 2012. “Geographies of Development: New Maps, New Visions?” The Professional Geographer 64 (1): 49–62. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00330124.2011.586878.

- Stephen, M. D. 2014. “Rising Powers, Global Capitalism and Liberal Global Governance: A Historical Materialist account of the BRICs Challenge.” European Journal of International Relations 20 (4): 912–938. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066114523655.

- Viola, L. A. 2020. The Closure of the International System: How Institutions Create Political Equalities and Hierarchies. Vol. 153. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Wilkinson, R., E. Hannah, and J. Scott. 2014. “The WTO in Bali: What MC9 Means for the Doha Development Agenda and Why It Matters.” Third World Quarterly 35 (6): 1032–1050. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2014.907726.

- Weinhardt, C. 2020. “Emerging Powers in the World Trading System: Contestation of the Developing Country Status and the Reproduction of Inequalities.” Global Society 34 (3): 388–408. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13600826.2020.1739632.

- WTO. 2001. Doha WTO Ministerial Declaration. WT/MIN(01)/DEC/1. Accessed October 3, 2021. https://www.wto.org/english/thewto_e/minist_e/min01_e/mindecl_e.htm

- WTO. 2019a. An Undifferentiated WTO: Self-Declared Development Status Risks Institutional Irrelevance. Communication from the United States. General Council, WT/GC/W/757. Accessed October 3, 2021. https://docs.wto.org/dol2fe/Pages/SS/directdoc.aspx?filename=q:/WT/GC/W757.pdf

- WTO. 2019b. The Continued Relevance of Special and Differential Treatment in Favour of Developing Members to Promote Development and Ensure Inclusiveness. WT/GC/W/765/Rev.2. Accessed October 3, 2021. https://docs.wto.org/dol2fe/Pages/FE_Search/FE_S_S009-DP.aspx?language=E&CatalogueIdList=251955&CurrentCatalogueIdIndex=0&FullTextHash=371857150&HasEnglishRecord=True&HasFrenchRecord=True&HasSpanishRecord=True

- WTO. 2019c. Draft General Council Decision: Procedures to Strengthen the Negotiating Function of the WTO. Communication circulated by the US. Accessed October 3, 2021. https://docs.wto.org/dol2fe/Pages/FE_Search/FE_S_S009-DP.aspx?CatalogueIdList=251580

- WTO. 2019d. Statement on Special and Differential Treatment to Promote Development. WT/GC/202. Accessed October 3, 2021. https://docs.wto.org/dol2fe/Pages/SS/directdoc.aspx?filename=q:/WT/GC/202R1.pdf

- Zarakol, A., ed. 2017. Hierarchies in World Politics. Vol. 144. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.