Abstract

Since its independence, Kazakhstan has adopted a multi-vectorism approach to balance between various great powers, especially between Russia and China. Despite extensive theorisation of such foreign policy, scholarly research has rarely investigated the topic beyond diplomatic power dynamics. Based on a systematic search of China’s joint projects in Kazakhstan in the past 30 years, this paper illuminates several unexpected developmental intricacies based on Kazakhstan’s multi-vectorism, its geo-strategic location, the availability of oil-driven sovereign wealth funds, and the public pressure for more responsible industrial policies: (1) China’s ambition to connect to the West has unintentionally amplified Kazakhstan’s multi-vector bargaining power; (2) Kazakhstan’s industrial policies, supported by various financial tools backed by its oil-driven sovereign wealth funds, are integral to its multi-sector economic development and diversification of exports to include more high-value intermediate and consumer goods; and (3) shown via a case study on Kazakhstan’s agricultural development, initial state-level negotiation and sub-national implementation, coupled with a mix of Sinophobic and Sinophilic sentiments, have led to a nuanced path of economic diversification. Given the authoritarian legacy in both China and Kazakhstan, empirical research to compare industry-specific development variations would be enlightening for developing economies to design optimal paths to leverage China’s rising dream and capital.

Introduction

Soon after the disintegration of the Soviet Union, Kazakhstan proclaimed the adoption of a ‘multi-vector’ foreign policy (Clarke Citation2015; Vanderhill, Joireman, and Tulepbayeva Citation2020) to benefit most from its large reserve of hydrocarbon resources and strategic location connecting China, Russia, Eastern Europe and the Middle East (Hanks Citation2009). As the country with the world’s twelfth largest petroleum reserve and sharing two long, strategic borders with Russia and China, Kazakhstan’s geographical endowments have created a huge development dilemma. While the global demand for petroleum allows Kazakhstan to trade its resources for foreign capital and technology for economic development, Kazakhstan could also become overly dependent on a resource-driven economy, and the presence of foreign companies would threaten the growth of domestic industries. The proximity to Russia and China has fuelled further concerns about state security. Undertaking a multi-vector foreign policy thus equips Kazakhstan with a hedging strategy against Russia, China and other countries. Amidst the extensive theorisation of Kazakhstan’s multi-vectorism, scholarly research rarely investigates beyond power dynamics. This paper thus takes Kazakhstan’s long-standing multi-vectorism as an entry point and extends the discussion beyond a pure diplomatic dynamic to examine Kazakhstan’s changing leverage amid China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and the resulting economic diversification.

Based on a desk-bound search of China’s joint projects in Kazakhstan of the past 30 years and a case study of the agriculture sector, this paper triangulates data from different sources and spotlights Kazakhstan’s engagement with China’s BRI projects and finance. Specifically, the combined effects of Kazakhstan’s distinctive multi-vectorism and its geo-strategic location for China’s BRI connectivity, the availability of its oil-driven sovereign wealth funds for economic diversification, and the public pressure for responsible industrial policies have resulted in three developmental intricacies: (1) China’s attempt to use BRI to connect to the West via the Eurasian landmass has increased Kazakhstan’s multi-vector leverage vis-à-vis China, affording it more bargaining power than before and resulting in more initiatives in non-connectivity-related joint projects than only those focussing on pipeline and transport connectivity infrastructure; (2) Kazakhstan’s petroleum reserve and related sovereign wealth funds have further enhanced the state’s capacity to diversify its economy and export more high-value intermediate and consumer goods; and (3) Kazakhstan’s agricultural development shows the initial outcomes of state-level negotiation and sub-national processes, coupled with both Sinophobic resistance and Sinophilic drive, have shaped a nuanced agro-development.

This paper will first explain Kazakhstan’s leverage based on its multi-vector foreign policy, the changing power structure with China, and its resource-driven sovereign wealth funds; second, based on a triangulation of secondary data and statistics, the trajectory of Kazakhstan’s multi-sector economic diversification will be discussed; third, a case study of Kazakhstan’s agriculture and food processing industry reveals how the public pressure and sub-national forces manifest and shape the outcome of the relevant Sino–Kazakh joint projects. Finally, the conclusion recaps Kazakhstan’s endeavour to balance rising external powers with conflicting domestic interests, before making suggestions on how future research should follow through on the long-term outcomes and industry-specific challenges.

Explaining Kazakhstan’s multi-vectorism and the changing power structure with China

In the past 30 years, Kazakhstan has adopted a multi-vector foreign policy to sustain its independent sovereign identity (Clarke Citation2015; Vanderhill, Joireman, and Tulepbayeva Citation2020). Specifically, Kazakhstan engages with different great powers by dividing issues into smaller parts, co-aligning the respective interests with different countries, and mitigating the risk of over-dependence on any single partner (Contessi Citation2015). Based on such a ‘pragmatic, non-ideological foundation’ (Hanks Citation2009, 259), Kazakhstan has been oscillating between balancing (against) and bandwagoning (with) great powers such as China, Russia, the United States and the European Union, to minimise loss and maximise gains, and to maintain its identity and autonomy. For example, against demands from the West, Kazakhstan refuses to implement anti-corruption and democratic reforms. It also refuses to lower the local content requirement for foreign companies to set foot in Kazakhstan (Vanderhill, Joireman, and Tulepbayeva Citation2019). The complexity of Kazakhstan’s approach to assert its strategic preferences is typified by its ‘hedging dynamics’ and multi-faceted ties to its two immediate great-power neighbours (Ohle, Cook, and Han Citation2020): Russia, which is loaded with traditional cultural and ethnic legacy, and China, which has recently emerged with rising influence in the region.

Kazakhstan’s multi-vector relation with Russia and China

With a 7000-km shared border, Kazakhstan and Russia have long-term historical ties in terms of shared ethnic, linguistic and socio-cultural origin. In addition to the presence of Russian minorities, language and media originating in Russia, there is abundant cooperation between the two countries through leadership elites, non-governmental organisations and educational associations (Laruelle, Royce, and Beyssembayev Citation2019). Russia has also been considered to have effected an ‘authoritarian diffusion’ in Kazakhstan (Ziegler Citation2016). Since the foundation of the Customs Union among Russia, Belarus and Kazakhstan in 2011, Russia’s share of Kazakhstan’s imports has remained significant, reaching as high as 35% in 2020 (ITC Trade Map n.d.). Many Russian corporations also own substantial shares of or have entered into partnerships with Kazakhstani companies in the energy, railroad infrastructure, agricultural and arms manufacturing sectors (Laruelle, Royce, and Beyssembayev Citation2019).

Despite the indispensability of their relations and Kazakhstan’s popular acceptance of Russia, the Kazakhstani government has tried hard to maintain its sovereign identity by rejecting a joint parliament as well as common citizenship and currency with Russia since the establishment of the Eurasian Economic Union in 2015 (Libman Citation2018). Kazakhstan has endeavoured to reconstitute its pre-Soviet ‘Eurasian’ identity using a narrative that recounts its Turkic Khaganate days (Shlapentokh Citation2016). The Kazakh government established the National Museum of the Republic of Kazakhstan in 2014, and in 2015 celebrated the 550th anniversary of the national foundation (Laruelle, Royce, and Beyssembayev Citation2019). Kazakhstan’s participation in the Collective Security Treaty Organization to receive military training from Russia was also balanced by its military cooperation with the North Atlantic Treaty Organization and increasing purchase of military equipment from Europe (Vanderhill, Joireman, and Tulepbayeva Citation2020). These high-profile, distinctly nationalistic, rhetorical gestures and emphases have well demarcated the Kazakh identity from the Russian, reinforcing Kazakhstan’s independent sovereignty as being justified, and its rulership as legitimate.

Kazakhstan’s diplomatic relations with China began in 1992. Sharing 1700 km of border, the two countries have established close ties in economic and security cooperations. Kazakhstan also participates in the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO), whose full list of members includes China. While the SCO is widely regarded as a regional organisation for ensuring sovereign security, particularly targeting terrorist activities (Ohle, Cook, and Han Citation2020), it also serves as a multilateral platform for Kazakhstan to avoid having to choose between Russia and China.

China’s recently announced BRI is an encompassing principle for the country to enlist economic cooperation with and expand influences in countries connected to the West. Being a key adjacent country, Kazakhstan has taken the opportunity to integrate BRI with such national policy as the ‘Nurly Zhol’ (Bright Path) project, the ‘2050’ strategy, and the ‘100 concrete steps’. However, the BRI has also met deep-seated Sinophobia in Kazakhstan – a fear for a possible Chinese economic and cultural domination in the country (Serikkaliyeva, Amirbek, and Batmaz Citation2018). While China’s interest in securing hydrocarbon supplies from Kazakhstan through inland routes over maritime transport allows Kazakhstan to counteract its over-dependence on the Russian market, Kazakhstan has also grown very cautious in limiting China’s influence by forbidding the Chinese to lease land for agricultural investment and declining requests to streamline entrance visa applications for Chinese travellers (Vanderhill, Joireman, and Tulepbayeva Citation2020). This multi-vector strategy is also illustrated by a clear signal that its willingness to cooperate with China is conditional: in 2018, the Kazakh government refused to deport an ethnic Kazakh woman with Chinese citizenship who had worked in a re-education camp in Xinjiang and later crossed the border illegally to join her family (Bisenov Citation2018; Putz Citation2018); and, in 2019, Kazakhstan arrested and charged a consultant for leaking information to China (Grove Citation2019).

Unpacking the changing Sino–Kazakh power structure: an asymmetrical frame

In 2001, China, Russia and the Central Asian states of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan formally announced the establishment of the SCO (SCO n.d.). Many scholars regard the SCO as a manifestation of China’s rising capacity and ambition to dominate and profit from the region (Swanström Citation2007; Kim and Blank Citation2013; Song Citation2014; Reeves Citation2018), and Kazakhstan has been viewed as a weak partner of China with minimal negotiation power and limited ‘freedom of action’ (Kim and Blank Citation2013, 774). However, China’s recent BRI has inadvertently increased Kazakhstan’s multi-vector leverage vis-à-vis China, affording it more bargaining power than before.

A closer look at this asymmetry in power would explain why Kazakhstan can adopt a multi-vector strategy through which it engages China: As China is a strong global power, it represents a cause for concern for Kazakhstan. Kazakhstan itself, on the other hand, being a regional power at best, registers somewhat low on China’s watchlist (i.e., China’s priorities are elsewhere) (Womack Citation2010, Citation2016; Arreguín-Toft Citation2005; Anderson Citation2013). However, as much as this asymmetry might seem all unfavourable for Kazakhstan, in the case of a destructive engagement, Kazakhstan in fact has less to lose. Recognizing this (i.e., that their stakes are uneven), both sides of the table therefore acknowledge that it is in their best interest not to perturb the current relationship – with Kazakhstan showing deference and China respecting Kazakhstan’s autonomy. Since signing a boundary treaty in 1994, China and Kazakhstan have participated in the ‘Shanghai Five’ or the SCO under China’s ‘good neighbour’ policy in 1996 and 2001 (Peyrouse Citation2016). China has not bothered to step up its influence, and Kazakhstan has been able to diversify its pipeline orientation among Russia, China and the Caspian region to gain autonomy and concessions from various players.

Kazakhstan has benefitted from having numerous great powers to share the stakes in regional security (Vanderhill, Joireman, and Tulepbayeva Citation2019). Its multi-vector strategy has largely been confined to foreign policies and extends, at best, to pipeline politics (Cutler Citation2014). The turning point came in 2013 when China announced BRI. Geographically, Russia could also be an indispensable partner, as both Beijing and Moscow are eager to confine American power. However, China and Russia have ‘different dreams in the same bed’, as they exert their influence in Central Asia (Kim and Blank Citation2013). China’s recent rise in economic power has exacerbated the problematic bilateral relation. For example, Russia has suspected China of copying and reselling its military technology, and the competing statecraft could threaten its regional influence in Central Asia (Flikke Citation2016). Russia’s disposition against the hegemonic West and its self-identification as a great power has also resulted in ‘public cooperation and private rivalry’ with China, which prioritises cooperative pragmatism and multilateral engagement (Cooley Citation2018).

In 2009, China pressed the SCO to act beyond its original regional security mission (Aris Citation2011). In addition to directly resolving transnational security threats, China wanted to promote the economic development of Central Asia to stabilise the region. However, not only did Russia object to China’s economic initiatives such as creating an emergency ‘crisis fund’ and the SCO development bank, China’s motives were questioned by many Central Asian countries (Cooley Citation2009, Citation2018). While some scholars consider the early Sino–Russian relations more rhetorical than substantive and more fragile than expected (Swanström Citation2014), others argue that the two countries have become close partners as a result of the bilateral declaration signed between Vladimir Putin and Xi Jinping to link up the Eurasian Economic Union and BRI in 2015 (Li Citation2018; Kuteleva and Vasiliev Citation2020), Russia’s subsequent ‘pivot to Asia’ strategy (Lukin Citation2019), and a shared vision of a Eurasian future (Rolland Citation2019). Nonetheless, the potential rivalry between the two great powers due to China’s hunger for energy and expanding influence in Eurasia should not be overlooked (Freeman Citation2018; Rolland Citation2019). As such, both the tacit political-economic rivalries in the future and the unsuccessful attempt to turn the SCO into a development platform underscore China’s desperate search for alternative connectivity via Kazakhstan (Gabuev Citation2016).

To this end, China’s state elites have had to take Kazakhstan more seriously in issues relating to connectivity. In 2013, Chinese President Xi Jinping announced the BRI in Kazakhstan. In March 2015, China further characterised such a developmental proposal as a trans-regional project running through Eurasia (Xinhua Citation2015). China has unwittingly increased Kazakhstan’s negotiation power by according it more leverage to negotiate for more non-connectivity joint projects to diversify its economy.

Illuminating the role of Kazakhstan’s oil-driven sovereign wealth funds

Kazakhstan’s economic growth has been driven predominantly by extracting resources (Gallo Citation2021). However, the fluctuations in global oil prices and the devaluation of Kazakhstan’s currency (tenge) in 2015–2016 have undermined the country’s economic development. To mitigate such a ‘resource curse’, Kazakhstan has used its sovereign wealth funds as a key agency to set up various financing arrangements such as state subsidies and a credit system to shape the trajectories of strategic industrial development and foster economic diversification (Capapé et al. Citation2020).

There are three sovereign wealth funds in Kazakhstan: the National Fund of the Republic of Kazakhstan (NFRK), the Samruk-Kazyna (SK), and the National Investment Corporation (NIC) of the National Bank of Kazakhstan. NFRK is primarily financed by taxation income from the oil, gas and copper mining sectors, and the privatisation of state assets and land sales. Each year, the Kazakhstani government transfers funds from NFRK to the state budget to stabilise the national economy, especially because of volatile external factors (Kalyuzhnova Citation2011; Analytical Credit Rating Agency Citation2020; ILL 2012). During the financial crisis of 2007–2009, NFRK successfully stabilised Kazakhstan’s economy as a risk buffer, allocating 10 billion USD (9.5% of gross domestic product, GDP) to housing, construction, agriculture and other Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs). The Kazakhstani economy thereby regained momentum, with 6% GDP growth driven largely by industry and net export (Kalyuzhnova Citation2011). In 2010, Kazakhstan announced a ‘State Program of Forced Industrial and Innovative Development’ to accelerate the economic diversification via a specialisation in manufacturing and expanding non-primary goods export (Decree of the President of the Republic of Kazakhstan Citation2010). The idea has been to maximise the contribution of oil revenues by transferring funds via NFRK to industries with the potential to acquire crucial production capacity in deep-processing and value-added sectors. This could structurally transform Kazakhstan’s economy from a resource-driven model into a more balanced approach.

Out of the 10 billion USD spent by NFRK during the 2007–2009 financial crisis, 9 billion USD was injected in 2008 into the second fund, SK, to facilitate economic diversification (International Monetary Fund Citation2009). By 2020, SK had managed a wide range of assets with a total value of 67.43 billion USD, ranking it first in the country and 20th in the world (Capapé et al. Citation2020). SK prioritises funding non-extractive industries and private equity market infrastructure including logistics, energy, food and beverage production, construction materials and paper products, as well as chemistry and petrochemistry (Kazyna Capital Management Citation2019).

The last and smallest fund, the NIC, was established in 2012. Owned by the National Bank of Kazakhstan (NBK), the fund manages and enhances the long-term returns of Kazakhstan’s sovereign assets and foreign exchange reserves of NBK, pension funds and other assets determined by the legislation of the Republic of Kazakhstan (International Forum of Sovereign Wealth Funds Citation2021; National Investment Corporation of National Bank of Kazakhstan n.d.). With the state’s aspirations to become one of the world’s top 30 developed nations (Nazarbayev Citation2012), and having specific monetary support for economic diversification, Kazakhstan’s industrial stakeholders have been empowered to negotiate for co-investment and partnership with Chinese capital and companies in both connectivity- and non-connectivity-related projects (Samruk-Kazyna Citation2019).

Taking stock of Chinese projects in Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan’s resource-dependent economy has widely been considered the result of China’s long-standing policy of resource extraction (Minbaeva and Muratbekova-Touron Citation2011; Chazan Citation2010; Peyrouse Citation2007). Some scholars further argue that China’s past infrastructure projects have facilitated corruptive practices among Kazakhstan’s state elites and inevitably fuelled Sinophobic sentiments (Laruelle and Peyrouse Citation2012; Rastogi and Arvis Citation2014). There is widespread speculation on undesirable consequences for Kazakhstan to participate in China’s connectivity infrastructure in the region (Griffiths Citation2019; Hillman Citation2018; World Bank Citation2019; Burkhanov and Chen Citation2016). Peyrouse also recounts that in Kazakhstan, trading with China has been unfavourable, akin to interacting with ‘a distant but recurrent enemy’ (2016, 14). Despite these sceptical views, BRI’s impact on agriculture, trade, climate and corruption in Central Asia is still uncertain (Laruelle Citation2018; Bitabarova Citation2018). Drawing on a meticulous effort to track down the Sino–Kazakh joint projects in the past 30 years, the following section shows that the development tracjectories of different industrial sectors vary.

Changing nature of Sino–Kazakh joint projects

Information about China’s projects in Kazakhstan had been extremely limited until September 2019, when Kazakhstan’s Ministry of Industry and Infrastructure Development (MIID) disclosed 27 projects under its auspices (Kazakhstan’s MIID 2019). A full list of 55 projects was soon available, comprising the 27 on the MIID’s list, seven that belonged to the Ministry of Agriculture, 20 under the Ministry of Energy and one under the Astana International Financial Centre (Simonov Citation2019; Medeubayeva Citation2019). Kazakh Invest, a national export and investment agency, later announced a similar list of 54 Sino–Kazakh joint projects (Kazakh Invest Citation2019). Earlier, a Norwegian research team had collected information on 261 Chinese projects in Central Asia, of which 102 took place in Kazakhstan (CADGAT Citation2019). Based on this information, as well as subsequent follow-through search, 166 Chinese projects in Kazakhstan are listed in ; some of them are completed, whereas others are under construction, planned or terminated.

Table 1. Sino–Kazakhstan joint projects planned and completed between 1997 and 2022.

Before 2013, the majority of China’s involvement in Kazakhstan was related to oil and gas extraction, pipeline construction, metal mining, transport infrastructure and a few cultural projects. In 1997, China and Kazakhstan initiated the first state-level negotiation over oil cooperation (Ho Citation2017). China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) acquired 66.7% shares of JSC AktobeMunaiGaz at 325 million USD and agreed to increase its investment from 585 million USD in five years to 4 billion USD in 20 years (CADGAT Citation2019). In 2002, 2004 and 2006, CNPC coopoerated with several Kazakh companies to build the first Kazakhstan–China oil pipeline, and acquired 49–50% of the shares in each phase (CADGAT Citation2019). The first stage of the 962-km pipeline began operation in 2006 (Xinhua Citation2006).

Since then, China has invested in or partnered with various Kazakh companies, primarily in resource extraction and connectivity infrastructure. Between 1997 and 2012, 20 out of 28 Chinese projects in Kazakhstan have been fuel- and connectivity-related. They include 10 oil and gas mining and pipeline construction projects, three telecommunications projects, three transport infrastructure projects and four Confucius Institutes involving at least 30.82 billion USD (cost information is not available for some projects; see ). The remaining eight projects include the reconstruction of the Moinak hydropower station, a food-processing company in Tsinkaz (Peyrouse Citation2008), a farm in Alakol (Grain.org Citation2008), three oil refining petrochemical projects, a leaching mine for uranium production and a loan to the Development Bank of Kazakhstan.

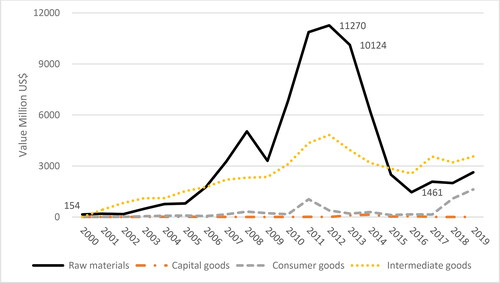

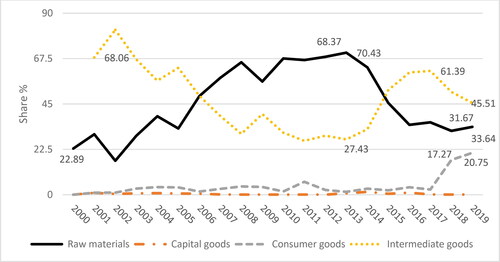

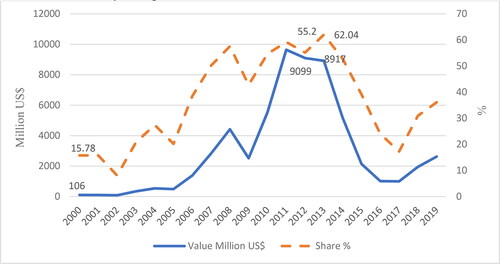

China’s focus on resource extraction has resulted in Kazakhstan’s over-dependence on exporting resources. Kazakhstan’s total export value to China has increased from 0.67 billion USD in 2000 to 16.48 billion USD in 2012, over half of which was fuel (see and ). China’s investment in the oil sector, however, has not enhanced Kazakhstan’s oil extraction and refinery technology. Kazakhstan’s oil quality is not suitable for direct consumption and its oil exported to China has to be further processed through different petrochemical procedures. As such, Kazakhstan has to export crude oil to and import processed petrochemical products from China. In 2013, when China announced the BRI, Kazakhstan began to negotiate to acquire China’s processing technologies to diversify its economy (Yau Citation2020a).

Table 2. Kazakhstan’s trade with China and the world, 2000–2019 (billions USD).

The composition of Sino–Kazakhstan joint projects and the bilateral trade structure have changed since 2013. Among all the projects listed in that have started construction or been planned since 2013, 113 out of the 138 Chinese projects in Kazakhstan have been non-fuel and non-connectivity related. They include projects in agriculture and food processing, building materials, chemistry and petrochemistry, energy and renewable energy, finance, industrial parks, manufacturing, mechanical engineering, and metal mining and metallurgy. The total spent/committed investment amounts to 53,832 million USD, which is 72% of all the joint projects (cost information is not available for four projects). Out of these 113 projects, 44 are reported as completed, 17 have begun construction, 31 are still under planning and one has been terminated (status information is not available for the remaining 20 projects). Although some projects may have been postponed or never realised, a quick comparison between the list of agreed projects before and after the announcement of the BRI illuminates Kazakhstan’s increasing bargaining power.

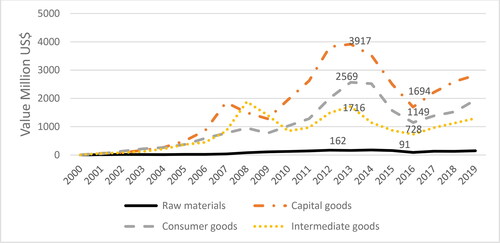

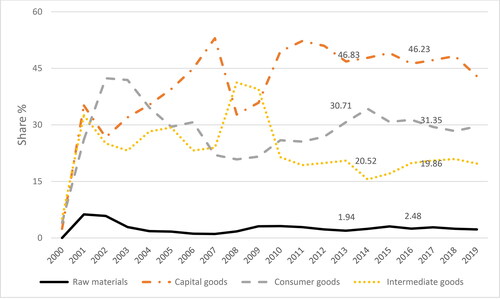

As regards bilateral trade, Kazakhstan’s export of raw materials to China increased from 0.15 billion USD (22.89%) in 2000 to 11.27 billion USD (68.37%) in 2012 ( and ). Specifically, fuel export increased from 0.11 billion USD (15.78%) to 9.1 billion USD (55.2%), and maintained a peak at 8.92 billion USD (62.04%) in 2013 before gradually subsiding (). Consequently, the bilateral trade has become more balanced (). Despite the drastic change in the structure of Kazakhstan’s export to China, its import structure from China has remained relatively stable, with capital goods always constituting the majority of the imports except in 2008. All imports, whether capital, consumer, or intermediate goods, from China to Kazakhstan dropped after that announcement, until 2016, when imports picked up momentum again ( and ).

Figure 1. Kazakhstan’s exports to China: total value by category, 2000–2019.

Source: World Integrated Trade Solution data, World Bank, available at: https://wits.worldbank.org/CountryProfile/en/Country/KAZ/Year/2019/TradeFlow/EXPIMP/Partner/CHN/Product/all-groups (accessed 16 June Citation2021).

Figure 2. Kazakhstan’s exports to China: shares by category, 2000–2019.

Source: World Integrated Trade Solution data, World Bank, available at: https://wits.worldbank.org/CountryProfile/en/Country/KAZ/Year/2019/TradeFlow/EXPIMP/Partner/CHN/Product/all-groups (accessed 16 June 2021).

Figure 3. Kazakhstan’s fuel exports to China: total value and shares, 2000–2019.

Source: World Integrated Trade Solution data, World Bank, available at: https://wits.worldbank.org/CountryProfile/en/Country/KAZ/Year/2019/TradeFlow/EXPIMP/Partner/CHN/Product/all-groups (accessed 16 June 2021).

Figure 4. Kazakhstan’s imports from China: total value by category, 2000–2019.

Source: World Integrated Trade Solution data, World Bank, available at: https://wits.worldbank.org/CountryProfile/en/Country/KAZ/Year/2019/TradeFlow/EXPIMP/Partner/CHN/Product/all-groups (accessed 16 June 2021).

Figure 5. Kazakhstan’s imports from China: shares by category, 2000–2018.

Source: World Integrated Trade Solution data, World Bank, available at: https://wits.worldbank.org/CountryProfile/en/Country/KAZ/Year/2019/TradeFlow/EXPIMP/Partner/CHN/Product/all-groups (accessed 16 June 2021).

Kazakhstan’s growing leverage

China’s strategic goals to cooperate with the Central Asian countries on border security issues can be traced back to the first ‘Treaty on Deepening Military Trust in Border Regions’ signed in 1996, the ‘Treaty on Reduction of Military Forces in Border Regions’ in 1997, and the SCO in 2001 (Wu and Chen Citation2004). Despite the later consent to deepen bilateral collaboration with Kazakhstan in trade and industrial investment and the establishment of the China–Kazakhstan Cooperation Committee in 2004, Kazakhstan has not been successful in diversifying China’s involvement away from resource extraction and infrastructure (Wu and Chen Citation2004; Peyrouse Citation2008). The year 2013, when China put forward its BRI, was a turning point, as Kazakhstan is an immediate neighbour and a gateway that connects to the West, so China has had to take Kazakhstan seriously and give Kazakhstan increased leverage during negotiations so as to secure more more desirable joint projects along with other must-have items on its wish list. Seeing a limited realisation of foreign investment to diversify Kazakhstan’s economy (Visser and Spoor Citation2011), the Astana government has taken China’s expansionist drive as ‘the last hope to diversify and jump-start the economy’ (Kassenova Citation2017, 114).

In 2014, then Kazakh President Nursultan Nazarbayev budgeted 9 million USD for a comprehensive infrastructure development plan, ‘Nurly Zhol’, which he publicly tied to the BRI (Yau Citation2020b). Sino–Kazakh working groups have since been established to match the initiatives from both countries (Pieper Citation2021). In 2016, the Ministry of Investment and Development of Kazakhstan negotiated with the National Development and Reform Commission of China for the Kazakhstan–China Program of Industrial Cooperation, which sought to move 55 industrial projects from China to Kazakhstan with a combined capital investment of 26 billion USD from Chinese and Kazakhstani partners (Jochec and Kyzy Citation2018). Kazakhstan has proactively pitched its development plan to China (Tian Citation2018; Maitra Citation2017; Shtraks Citation2016), and this is possible because (1) China’s BRI aspiration has given more leverage to Kazakhstan’s multi-vectorism strategy; and (2) Kazakhstan’s sovereign wealth funds have made Kazakhstan relatively self-sufficient by allowing the resource-generated wealth to trickle down its multi-sector development. Many of Kazakhstan’s state-prioritised projects have been supported by its sovereign funds in conjunction with multilateral development banks (Zogg Citation2019). As such, China’s loan to Kazakhstan has never exceeded 10% of the country’s total debt since 2014, and Chinese capital in terms of state loan and commercial investment has always been kept below 10% (see ).

Table 3. Kazakhstan’s debt to and foreign direct investment (FDI) from China, 2014–2020.

Kazakhstan’s desire for industrial technologies also fit well into ‘Made in China 2025’ announced in 2015, which is aimed at displacing China’s industrial overcapacities overseas and re-orientating its manufacturing-led and infrastructure-led economy to high-end yet environmentally friendly development (Cyrill Citation2018). Although governments do in principle agree on such joint initiatives, the materialisation of specific projects has been met with practical challenges such as financial concerns regarding funding feasibility and public scepticism about unchecked Chinese influence, environmental degradation and undesirable low-tech transfers (Tian Citation2018; Jochec and Kyzy Citation2018). Chinese officials are therefore ‘grateful’ when a host country pitches projects that align with the BRI’s broadly defined connectivity goals (Shtraks Citation2016). Despite the uncertainty regarding the outcome of such joint projects, Kazakhstan has been able to negotiate for projects that give its bid for economic diversification a better chance of success. The following case study of Kazakhstan’s agricultural development exemplifies the initial outcome of the state-level negotiation and sub-national process, through which Sinophobic resistance mixed with Sinophilic drive has shaped a nuanced development of Kazakhstan’s agricultural sector.

Making sense of the sub-national agricultural and food-processing sector

After its independence from the former Soviet Union, the Kazakh government adopted a liberal approach in its agricultural sector, which included rice and cotton fields in the south, wheat in the north, and oil in the east. The initial increase in agricultural output was soon followed by a prolonged decline in output because of diminishing agricultural and livestock enterprises, from more than 6500 in 1990 to less than 500 in 2000. The overall output between 1996 and 2000 was half of what the 1987–1991 period produced (Petrick and Pomfret Citation2016). Between 2003 and 2005, then Kazakh President Nazarbayev put forward the State Agriculture and Food Programme. The idea was to use the income generated from the extractive industry to invest in the farming and agricultural processing industry, enhance productivity, increase export and diversify the economy. The state budget in the agricultural sector therefore increased by almost four times, from 26 billion tenge in 2001 to 81 billion tenge in 2005, which in turn accounted for 2.5% and 6.5%, respectively, of the total state budget (Petrick and Pomfret Citation2016).

Such state-led policy was in place because the agrarian sector that emerged through de-collectivisation in the post-communist era was in desperate need of capital investment, management skills and stable employment (Lerman, Csaki, and Feder Citation2004; Petrick, Wandel, and Karsten Citation2013). The ultimate goal was to ensure national food security and enhance agricultural and processed food export (Wandel Citation2010). However, despite the Kazakh government’s claimed effort to reform its agriculture, the World Bank regarded its State Agro Food Program as only moderately successful because of a lack of institutional and financing support (Csaki and Kray Citation2005; Dudwick, Fock, and Sedik Citation2007). The second wave of state-led effort was directed to establish the KazAgro holding company in 2006 and consolidate institutional and policy support to boost agricultural productivity. Between 2008 and 2009, Kazakhstan’s state budget in the agricultural sector increased to 139 billion tenge, 45% of which was allocated to KazAgro. Around the same time, KazAgro Innovation was established to focus on agricultural research and technology development.

China was not active in agriculture or food processing projects until the BRI was announced in 2013. In the same year, Nazarbayev also announced ‘Agribusiness 2020’ to modernise the large-scale agriculture industry projects. Such national programmes included 15 master plans to enhance the legal framework, regulation and subsidies for regional specialisation of specific agricultural sub-sectors. One of the master plans was to construct 20 industrial and 2000 small-scale dairy farms between 2014 and 2020 to reduce the import of milk in the long term. The Kazakh Ministry of Regional Development also established the Social Entrepreneurship Corporation to attract investors to participate in projects of high socio-economic importance (Alibekova Citation2013; Kazakhstan’s Prime Minister Web Page Citation2013).

In November 2014, President Nazarbayev announced the Nurly Zhol to link up with BRI (President of the Republic of Kazakhstan Citation2014). The following year, Nazarbayev put forward a 100-step programme to materialise various institutional arrangements in the government apparatus, legal system, and industrial, economic and social sectors. A few of these 100 steps focussed on agriculture-related developments (Kazakhstan Institute for Strategic Studies, n.d.) For example, the 35th and 36th steps concerned the agricultural land code. The 55th step aimed to attract at least 10 transnational corporations into the processing industry to enhance agricultural export. The 60th and 61st steps were to attract strategic investors in the milk, dairy, meat processing and development sectors (). Although the development outcome of these projects is still unclear and Kazakhstan’s agricultural exports are arguably still far below their potential, the fact that ‘Agribusiness 2020’ was announced in the same year as China’s BRI suggests a desire on Kazakhstan’s part to appeal for Chinese cooperation.

Table 4. Five of the 100 steps to reform put forward by former President Narbarzabev in 2015.

Along with the 100-step reform, the Kazakh government began to strengthen cooperations with China for projects beyond resource extraction and transport infrastructure. Consequently, 54 joint projects were initiated with an estimated 23.17 billion USD of investment in the mining and metallurgy, chemistry and petrochemistry, engineering and renewable energy, transport, construction materials, and agriculture and agro-industrial sectors (Kazakh Invest n.d.a). Another source reported a similar scale of cooperation, with 55 projects involving a total of 27.6 billion USD (Simonov Citation2019). In 2015, Total Imepx–May Toyshın Ltd. was among the first companies to incorporate and process oil crops for the Chinese market. The project was reportedly valued at 23 million USD (CADGAT Citation2019). In 2016, Gulmira Isaeva, the Vice Minister of Agriculture, explained that Kazakhstan wanted Chinese investment in its agricultural sector, eg in tomato processing plants, oil seed processing, beef, lamb and horsemeat production, and chicken processing facilities: ‘In Kazakhstan we have no tradition to eat legs and heads of birds; in China it’s a delicacy …. We can export to China all products which we can grow in Kazakhstan’ (Farchy Citation2016). The following section explains the role of sub-national resistance in shaping this state-led development trajectory.

Sub-national forces shaping China’s joint agricultural projects in Kazakhstan

The 35th and 36th steps of the National 100-step reform were targeted at facilitating the legislative amendment of Kazakhstan’s Land Code and promoting effective privatisation of agricultural land. To attract foreign investment, the Kazakh government extended the lease of farmland to foreigners through joint ventures from 10 to 25 years in 2016. Going back to the year 2003, a Chinese company rented 7000 ha of land in Alakol county to grow soybeans and wheat and breed livestock for the domestic market and for export. As a result, 3000 Chinese farmers from Yili, Xinjiang, were deployed, and a joint Sino–Kazakh firm was set up to oversee the project (Grain 2008). The 2016 land reform, therefore, has spurred sub-national fears of a Chinese influx and subsequent harmful use of the soil. In April of the same year, a massive protest took place in Atyrau. It soon spread to neighbouring Aktau, Kyzylorda and Zhanaozen in the South, Aktobe in the North and Semey in the East; the local protesters had developed deep-seated anti-Chinese sentiments. Twenty years after China and Kazakhstan had signed the boundary treaty, the fear that China would take over the soil continued to haunt the local community (Bayer Citation2016; Bitabarova Citation2018).

Such local resistance has shaped the development of Sino–Kazakh agriculture projects from pure crop growing to deep food processing. Specifically, the widespread public protest has made Kazakhstan’s Deputy Agriculture Minister Isayeva vow to forbid Chinese investors to own Kazakh land. Instead, the government sought engagement with China’s agro-industrial capacity cooperation (Kenderdine Citation2017) and facilitated multiple joint partnerships with Chinese companies in the food processing industry (Farchy Citation2016). This not only prevents Chinese from taking control of Kazakhstan’s agricultural land, but also allows the Kazakh companies to acquire the Chinese food-processing technologies. In 2016 alone, there were seven agriculture-related joint projects, five of which focussed on the food processing industry to produce rapeseed oil, camel and horse milk and powdered milk, and to deep-process grain, flax and other crops; and two involved drip irrigation. By 2018, 22 agriculture projects were recorded to process poultry, antlers, sheep, fish, leather, fur, soybean, tomato, rapeseed and sunflower seed, involving about 1117 million USD. Out of these 22 projects, 18 were completed and one was under construction (no information was available about the remaining three). There were four more recently proposed agricultural projects, including a biochemical cluster for deep wheat processing that was estimated to cost about 2500 million USD (see detailed project information in ).

One typical illustration of the sub-national negotiation in Kazakhstan is the rapeseed oil facility established in 2016 (project no. 57 in ). Despite China’s desire to expand its agricultural development from north-west China to eastern Kazakhstan, and the joint establishment of the Sino–Kazakhstan Modern Agricultural Industry Innovation Demonstration Park in Almaty in 2015 to develop drought-resistant crops (Zakir Citation2018; Xinhua Citation2018), the public protest in 2016 has prevented Chinese enterprises from becoming directly involved in crop production. Instead, the Taiyinsha Mai LLP, an oil-seed processing plant in the Tayynshinsky district of northern Kazakhstan, has negotiated with China’s Xi’an AiJu Cereals and Oil Industry Group (AiJu) to jointly operate a rapeseed processing plant in the locality. On the one hand, such a food processing project does not require massive control of agricultural land; on the other hand, it facilitates technology transfer from China. With the state policy to promote oilseed production and export the processed oil to China, Russia and Uzbekistan, as well as different financing and infrastructure support from the Ministry of Agriculture and the Samruk Kazyna investment fund (Kazakh Invest n.d.b), Taiyinsha Mai has been able to acquire equipment and machineries, enjoy taxation holidays and process priority crops with state subsidies. With this development support, the Kazakh partner gained the upper hand in bargaining with the Chinese partner: in addition to getting access to AiJu’s retail rapeseed oil market in Xi’an, Chinese agro-experts could only arrive at the Kazakh plant in phases, allowing ample time for indigenous actors to learn and grow (Rspadm n.d.).

Local-level entrepreneurial drive to diversify exports

In addition to negotiating for technology transfer, local business stakeholders also worried about tightening trade policies, which would restrict Kazakhstan’s export to China (Bitabarova Citation2018). Such restriction would reduce the incentive for local actors to explore new business opportunities. The trade volume between the two countries reached its peak in 2012. The export value then dropped by 32% between 2013 and 2014 and a further 44% between 2014 and 2015 (). While falling oil prices could explain the shrinking value, the structural shift as described in the previous section also played a part. This warrants a more nuanced reading of the changing relations between a Kazakhstan that acquired more leverage and a China that continued to promote its BRI.

Kazakhstan’s export of raw materials to China increased from a 22.89% share to 70.43% of the total export between 2000 and 2013, and then dropped to 31.67% in 2018 before increasing to 33.64% in 2019. Over the same period, the share of the export of intermediate goods, including products such as stone and glass, metals, wood and plastic, decreased from 68.06% to 27.43% before rebounding to 61.39% in 2017 but dropping back to 45.51% in 2019 (). Kazakhstan’s export of consumer goods to China had always taken up a minimal share of less than 10%, until 2018 when it recorded a significant jump to 17% of total export and continued to increase to 20.75% in 2019 (). Kazakhstan’s export to China has gradually shifted from primarily resource-dominant to a more balanced distribution comprising intermediate goods, raw materials and consumer goods. For example, as seven new Chinese agriculture and food processing joint projects in Kazakhstan materialised, the share of the export of animal products, food products and vegetables increased by more than threefold, from 67.8 million to 235.5 million between 2013 and 2018 (World Integrated Trade Solution data, n.d.). This breakthrough was a result of combined efforts in pushing for economic diversification.

Specifically, the state-led negotiations on industrial and investment cooperation between the two governments were facilitated through the Kazakh–Chinese Coordination Committee. On the other hand, numerous bottom-up sub-national initiatives also managed to shape the outcome of Kazakhstan’s engagements with the BRI. For example, the Chinese government had considered the China–Europe freight service one of its signature BRI projects, connecting Chinese cities with Central Asian and European cities. Various local Chinese governments, therefore, rushed to provide subsidies for even non-viable freight routes as a gesture of goodwill towards the central policy. As a result, freight operators receiving political subsidies operated frequent freight trains despite the trade imbalance and inefficient use of empty return trains to China. To make extra earnings, various Chinese railway companies soon established respective trading offices in en-route cities. For example, they hired several Chinese-speaking Kazakh representatives in Almaty to explore possible trade opportunities and arrange exports using their empty return trains to China. Their entrepreneurial drive for personal gain has unintentionally expanded the market for Kazakhstan’s agricultural, food-processing and certification sectors (Tjia Citation2020).

Such sub-national efforts were backed by state-level negotiation. Both governments have agreed, in the ‘Chinese–Kazakh 2020 Long-term Plan for Economic Cooperation’, that they would endeavour to optimise the bilateral trade structure by increasing the proportion of high-value-added and high-tech products (Xinhua Citation2014). This has led China to expand border crossing facilities, upgrade customs technology and improve infrastructure connectivity (Reeves Citation2018). The ensuing first batch of wheat was exported from Kazakhstan to Jiangsu in China in August 2018. Since then, chilled beef, live donkeys and barley were exported to China in August, November and December, respectively, of 2019. These exports involved enormous sub-national efforts not only in sourcing the suppliers but also in identifying suitable food testing laboratories and getting sanitary certificates for various agricultural products such as rapeseed, hay, barley, wheat, sweet corn, wheat flour, flaxseed and dairy products. In Citation2019, a few lists of Kazakhstan enterprises were announced as registered suppliers of soybean, sweet corn, barley and wheat goods for China (General Administration of Customs of China 2019). With a clear set of state-led priorities and well-received sub-national concerns about local economic development, Kazakhstan, as a recipient/engaging country, is able to cope with China’s strong desire to pursue its connectivity projects.

Conclusion

Kazakhstan’s pitch on China’s BRI projects illuminates the possibilities for developing countries to cope with China’s recent development agenda. Despite being a weak neighbour, Kazakhstan has adopted a multi-vector strategy to reduce its reliance on China. Seeing China use BRI to connect to the West via Central Asia, the Kazakhstani government has shaped its ‘Bright Path’ national development plan in a way that allows it to bargain for Chinese participation in non-connectivity joint projects. An initial mapping of the Sino–Kazakh joint projects suggests that China’s aspiration has unintentionally given Kazakhstan extra leverage, allowing it to punch above its weight in the regional economy. However, whether these planned joint projects could eventually be rolled out as promised to benefit the local community will rely on specific industrial policies and related state agents to act with integrity on behalf of public interest, as well as their capacity to follow through on the loose ends to complete the projects. This is especially challenging in Kazakhstan, where authoritarian legacy has given the state elites more power to collude and privatise public gains. The lack of transparency in many state programmes has also made any scrutiny of the industrial projects and inspection of their implementation and outcome difficult. There have been no official reports on the projects, and the outbreak of COVID-19 has made any field trips and interviews almost impossible. As such, one must rely on multiple secondary sources and triangulate their information. This sub-national case study of the evolving agriculture and food processing industry in Kazakhstan has therefore aimed to shed light on the micro-dynamics that stemmed from public resilience and has become critical in shaping state-level narratives during negotiations, steering the country’s development towards a promising trajectory. Further fieldwork and case studies should be carried out to compare the outcomes of different sectors such as the automobile, hydropower and petrochemical industries to provide a more comprehensive explanation of Kazakhstan’s multi-sector economic diversification and to determine the critical success factors.

China’s rise and subsequent increasing investment in developing countries often involve multiple development goals. Instead of speculating about the underlying agenda, it may be pragmatically more beneficial for the engaging states, especially the weak partners, to prepare for the inflow of resources and make the most of the situation. One illuminating lesson learned from the case of Kazakhstan is that state-level negotiation could kick off the engagement, and subsequent sub-national resilience and entrepreneurial drive can then interact and further shape the outcome of such cooperations. Whether this will eventually lead to a sustainable agricultural/food processing development and economic diversification in Kazakhstan, by reconciling the interests of large investors and local stakeholders to a large-scale foreign agro-industrial complex (UNCTAD Citation2009) and enhancing small farmers’ access to capital and technology and generating employment in the rural sectors, is worth following up as China’s BRI continues to evolve in Kazakhstan.

Acknowledgements

The work described in this paper was supported by the Early Career Research Scheme funded by the Research Grants Council of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, China (Project no. CityU 21606520) and the CityU Strategic Research Grant (Project No. 7005324). The author also thanks Huang Wenjie for her research assistance on this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Linda Yin-nor Tjia

Linda Yin-Nor Tjia is Assistant Professor at the Department of Asian and International Studies, City University of Hong Kong. Her research interests include China’s domestic and overseas railway, logistics, infrastructural and industrial projects, as well as the related impact on the engaging countries. She received numerous regional and international research grants to investigate China’s involvements in Kazakhstan, the high-speed rail development in China and Japan, and the agri-product development in Mongolia and Kazakhstan. Her articles appear in China Journal, Asian Survey, Journal of Transport History and Journal of Social Entrepreneurship. She is also the author of a monograph explaining Railway Reform in China: A Train of Property Rights Rearrangements and numerous book chapters published by Routledge and Edward Elgar.

Bibliography

- ADAL PROFI Engineering Comapny. n.d. “Arkalyk-Shubarkol Railway.” http://adal-profi.kz/eng/zheleznaya-doroga-arkalyk-shubarkol/ Accessed 4 March 2022.

- Alibekova, R. 2013. “Master Plans for Agribusiness 2020 Programme Developed.” The Astana Times, August 21.

- Analytical Credit Rating Agency. 2020. “Despite the Record Transfer in 2020, the NFRK Continues to be a Reliable Buffer for the Budget of Kazakhstan and Has a Positive Effect on the Country’s Rating.” https://www.acra-ratings.com/research/2270

- Anderson, J. 2013. “Distinguishing between China and Vietnam: Three Relational Equilibriums in Sino–Vietnamese Relations.” Journal of East Asian Studies 13 (2): 259–280. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S1598240800003933.

- Aris, S. 2011. Eurasian Regionalism: The Shanghai Cooperation Organisation. Critical Studies of the Asia-Pacific. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Arreguín-Toft, I. 2005. How the Weak Win Wars: A Theory of Asymmetric Conflict. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- AstanaBuild. 2015. “Aktau Bitumen Plant Launched the Production of Modified Bitumen.” October 28.

- Bayer, L. 2016. “Protests Spread across Kazakhstan.” Geopolitics Features, May 2. https://geopoliticalfutures.com/protests-spread-across-kazakhstan/. Accessed 4 March 2022.

- Bisenov, N. 2018. “Controversial Trial in Kazakhstan Sheds Light on Chinese Camps.” Open Democracy, September 10.

- Bitabarova, A. G. 2018. “Unpacking Sino–Central Asian Engagement along the New Silk Road: A Case Study of Kazakhstan.” Journal of Contemporary East Asia Studies 7 (2): 149–173. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/24761028.2018.1553226.

- Burkhanov, A., and Y. Chen. 2016. “Kazakh Perspective on China, the Chinese, and Chinese Migration.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 39 (12): 2129–2148. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2016.1139155.

- Cang, W. 2017. “China, Kazakhstan Feel Port’s Benefits.” China Daily, August 4.

- Capapé, J., P. J. Schena, G. Gupta, M. Menzemer, A. Blanco, P. Rose, I. Liu, and A. Dixon. 2020. “Sovereign Wealth Funds Report 2020.” Spain: ICEX-Invest in Spain, and IE Business School. https://www.investinspain.org/en/publications/sovereign-wealth-funds-2020. Accessed 4 March 2022.

- Central Asia Data-Gathering and Analysis Team (CADGAT). 2019. “CADGAT Unified Database on Belt and Road Initiative Projects in Central Asia, the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs (NUPI) and the OSCE Academy.”

- Chazan, G. 2010. “Kazakhs Pat Casts Light on China.” Wall Street Journal, March 27.

- Chen, H., and Y. Zhang. 2017. “Create a New Business Card of ‘One Belt and One Road’ Production Capacity Cooperation (打造“一帶一路”產能合作“新名片”).” Guangming Daily (光明日報), October 24, 2015.

- Clarke, M. 2015. “Kazakhstan’s Multi-Vector Foreign Policy: Diminishing Returns in an Era of Great Power ‘Pivots’?” The Asan Forum.

- Contessi, N. P. 2015. “Foreign and Security Policy Diversification in Eurasia: Issue Splitting, Co-Alignment, and Relational Power.” Problems of Post-Communism 62 (5): 299–311. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10758216.2015.1026788.

- Cooley, A. 2009. “Cooperation Gets Shanghaied.” Foreign Affairs, December 15.

- Cooley, A. 2018. “Tending the Eurasian Garden: Russia, China and the Dynamics of Regional Integration and Order.” In Sino–Russian Relations in the 21st Century, edited by J. Bekkevold and B. Lo, 113–139. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Cutler, R. M. 2014. “Chinese Energy Companies’ Relations with Russia and Kazakhstan.” Perspectives on Global Development and Technology 13 (5-6): 673–698. doi:https://doi.org/10.1163/15691497-12341323.

- Csaki, C., and H. Kray. 2005. “The Agrarian Economies of Central-Eastern Europe and the Common Wealth of Independent States: An Update on Status and Progress in 2004.” Environmentally and Socially Sustainable Development Working Paper 40. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

- Cyrill, M. 2018. “What Is Made in China 2025 and Why Has It Made the World so Nervous?” China Briefing, December 28.

- Decree of the President of the Republic of Kazakhstan. 2010. “The State Program of Forced Industrial and Innovative Development / Strategies and Programs / Activity / Financial Monitoring Agency of the Republic of Kazakhstan.”

- Dudwick, N., K. Fock, and D. J. Sedik. 2007. Land Reform and Farm Restructuring in Transition Countries: The Experience of Bulgaria, Moldova, Azerbaijan, and Kazakhstan. Washington, DC: World Bank Publications.

- Farchy, J. 2016. “China Plans to Invest 1.9 bn in Kazakh Agriculture.” Financial Times, May 9.

- Flikke, G. 2016. “Sino–Russian Relations Status Exchange or Imbalanced Relationship?” Problems of Post-Communism 63 (3): 159–170. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10758216.2016.1163227.

- Freeman, C. P. 2018. “New Strategies for an Old Rivalry? China–Russia Relations in Central Asia after the Energy Boom.” The Pacific Review 31 (5): 635–654. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09512748.2017.1398775.

- Gabuev, A. 2016. “Crouching Bear, Hidden Dragon: ‘One Belt One Road’ and Chinese-Russian Jostling for Power in Central Asia.” Journal of Contemporary East Asia Studies 5 (2): 61–78. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/24761028.2016.11869097.

- Gallo, E. 2021. “Globalisation, Authoritarianism and the Post-Soviet State in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan.” Europe-Asia Studies 73 (2): 340–363. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09668136.2020.1761297.

- General Administration of Customs. 2019. “List of registered Kazakhstan enterprises to export soya bean, sweet corn, barley and wheat goods to China).” 17 June, available at: http://www.customs.gov.cn/customs/302249/jyjy60/2aa7e043-3.html. Accessed 4 March 2022.

- Grain.org. 2008. “Seized: The 2008 Landgrab for Food and Financial Security.” 24 October, https://grain.org/article/entries/93-seized-the-2008-landgrab-for-food-and-financial-security. Accessed 5 March 2022.

- Griffiths, R. 2019. The New Silk Road: Challenge and Response. Leiden: HIPE Publications.

- Grove, T. 2019. “A Spy Case Exposes China’s Power Play in Central Asia.” Wall Street Journal, July 10.

- Hanks, R. R. 2009. “Multi-Vector Politics’ and Kazakhstan’s Emerging Role as a Geo-Strategic Player in Central Asia.” Journal of Balkan and near Eastern Studies 11 (3): 257–267. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/19448950903152110.

- Hillman, J. 2018. “The Rise of China–Europe Railways.” Center for Strategic and International Studies, March 6.

- Ho, S. 2017. “China’s Transboundary River Policies towards Kazakhstan: Issue-Linkages and Incentives for Cooperation.” Water International 42 (2): 142–162. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02508060.2017.1272233.

- Institute of Law and Legal Information of the Ministry of Justice of the Republic of Kazakhstan (ILL). 2012. “On the Concept for the Formation and Use of Funds of the National Fund of the Republic of Kazakhstan.”

- International Forum of Sovereign Wealth Funds. 2021. “JSC National Investment Corporation of the National Bank of Kazakhstan.”

- International Monetary Fund. 2009. “Republic of Kazakhstan: 2009 Article IV Consultation: Staff Report; Supplement; and Public Information Notice on the Executive Board Discussion.”

- Trademap.org. n. d. “Trade Statistics for International Business Development,” https://www.trademap.org/Index.aspx. Accessed 4 March 2022.

- Jochec, M., and J. J. Kyzy. 2018. “China’s BRI Investments, Risks, and Opportunities in Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan.” In China’s Belt and Road Initiative and Its Impact in Central Asia, edited by M. Laruelle, 67–76. Washington, DC: The George Washington University, Central Asia Program.

- Kalyuzhnova, Y. 2011. “The National Fund of the Republic of Kazakhstan (NFRK): From Accumulation to Stress-Test to Global Future.” Energy Policy 39 (10): 6650–6657. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2011.08.026.

- Kassenova, N. 2017. “China’s Silk Road and Kazakhstan’s Bright Path: Linking Dreams of Prosperity.” Asia Policy 24 (1): 110–116. doi:https://doi.org/10.1353/asp.2017.0028.

- Kazakh Invest. 2019. “Construction of Kazakhstan Chinese Investment Projects Will Be Carried out in accordance with Kazakhstani Law.” 10 September.

- Kazakh Invest. n.d.a. ““SEZ and IZ” – “Kazakh Invest”.” National Company JSC. https://zhambyl.invest.gov.kz/doing-business-here/special-economic-zone/

- Kazakh Invest. n.d.b. “Plant Growing.” https://invest.gov.kz/doing-business-here/regulated-sectors/agro/plant-growing/

- Kazakhstan Institute for Strategic Studies. n.d. “National Plan 100 Precise Steps.” http://www.kisi.kz/index.php/en/allcategories-en-gb/2-uncategorised/763-nation. Accessed 4 March 2022.

- Kazakhstan’s Ministry of Industry and Infrastructure Development (Kazakshtsan’s MIID). 2019. “Kazakhstan–Chinese Projects.” September 2.

- Kazakhstan’s Prime Minister Web Page. 2013. “Government Approved Agribusiness-2020 Program.” February 12.

- Kazyna Capital Management. 2019. “Annual Report 2019. Nur-Sultan: Republic of Kazakhstan.”

- Kenderdine, T. 2017. “China’s Agroindustrial Capacity Cooperaton in Central Asia.” The Central Asia-Caucasus Analyst, April 28. https://www.cacianalyst.org/publications/analytical-articles/item/13442-china%E2%80%99s-agroindustrial-capacity-cooperation-in-central-asia.html

- Kim, Y., and S. Blank. 2013. “Same Bed, Different Dreams: China’s ‘Peaceful Rise and Sino–Russian Rivalry in Central Asia’.” Journal of Contemporary China 22 (83): 773–779. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10670564.2013.782126.

- Koskina, A. 2019. “Astana LRT: A Project or a Scam?” Central Asia for Analytical Reporting, December 24.

- Kuteleva, A., and D. Vasiliev. 2020. “China’s Belt and Road Initiative in Russian Media: Politics of Narratives, Images, and Metaphors.” Eurasian Geography and Economics, 62 (5-6): 582–606. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15387216.2020.1833228.

- Laruelle, M., ed. 2018. “China’s Belt and Road Initiative and Its Impact in Central Asia.” The Central Asia Programme. Washington, DC: George Washington University.

- Laruelle, M., and S. Peyrouse. 2012. The Chinese Question in Central Asia: Domestic Order, Social Change, and the Chinese Factor. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Laruelle, M., D. Royce, and S. Beyssembayev. 2019. “Untangling the Puzzle of ‘Russia’s Influence’ in Kazakhstan.” Eurasian Geography and Economics 60 (2): 211–243. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15387216.2019.1645033.

- Lerman, Z., C. Csaki, and G. Feder. 2004. Agriculture in Transition: Land Policies and Evolving Farm Structures in Post-Soviet Countries. Lanham: Lexington books.

- Li, Y. 2018. “The Greater Eurasian Partnership and the Belt and Road Initiative: Can the Two Be Linked?” Journal of Eurasian Studies 9 (2): 94–99. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euras.2018.07.004.

- Libman, A. 2018. “Eurasian Economic Union: Between Perception and Reality.” New Eastern Europe, January 9.

- Lukin, A. 2019. “Russian–Chinese Cooperation in Central Asia and the Idea of Greater Eurasia.” India Quarterly: A Journal of International Affairs 75 (1): 1–14. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0974928418821477.

- Maitra, R. 2017. “One Belt One Road Brings New Life to Central Asia: Kazakhstan in Focus.” The Schiller Institute.

- Medeubayeva, M. 2019. “Part of the List of 55 Kazakhstan–Chinese Projects Published: The Ministry of Industry Has Submitted Its Part of the Projects.” inbusiness.kz.

- Minbaeva, D. B., and M. Muratbekova-Touron. 2011. “Experience of Canadian and Chinese Acquisitions in Kazakhstan.” The International Journal of Human Resource Management 22 (14): 2946–2964. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2011.606120.

- Mining-technology.com. 2018. “Aktogay Copper Mine.” 2 February, https://www.mining-technology.com/projects/aktogay-copper-mine/. Accessed 4 March 2022.

- Nicnbk.kz. n.d. “Investments: Investment Portfolio.” https://www.nicnbk.kz/en/investments. Accessed 5 March 2022.

- Nazarbayev, N. A. 2012. “Strategy Kazakhstan-2050: New Political Course of the Established State.” www.strategy2050.kz

- Ohle, M., R. J. Cook, and Z. Han. 2020. “China’s Engagement with Kazakhstan and Russia’s Zugzwang: Why is Nur-Sultan Incurring Regional Power Hedging?” Journal of Eurasian Studies 11 (1): 86–103. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1879366519900996.

- Petrick, M., and R. Pomfret. 2016. “Agricultural Policies in Kazakhstan.” In Handbook of International Food and Agricultural Policies, Volume I: Policies for Agricultural Markets and Rural Economic Activity, edited by W. H. Meyers and T. Johnson, 461–482. Washington, DC: World Scientific.

- Petrick, M., J. Wandel, and K. Karsten. 2013. “Rediscovering the Virgin Lands: Agricultural Investment and Rural Livelihoods in a Eurasian Frontier Area.” World Development 43: 164–179. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2012.09.015.

- Peyrouse, S. 2007. “The Hydroelectric Sector in Central Asia and the Growing Role of China.” The China and Eurasia Forum Quarterly 5 (2): 131–148.

- Peyrouse, S. 2008. “Chinese Economic Presence in Kazakhstan: China’s Revolve and Central Asia’s Apprehension.” China Perspective 3: 34–49.

- Peyrouse, S. 2016. “Discussing China: Sinophilia and Sinophobia in Central Asia.” Journal of Eurasian Studies 7 (1): 14–23. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euras.2015.10.003.

- Pieper, M. 2021. “The Linchpin of Eurasia: Kazakhstan and the Eurasian Economic Union between Russia’s Defensive Regionalism and China’s New Silk Roads.” International Politics 58 (3): 462–482. doi:https://doi.org/10.1057/s41311-020-00244-6.

- President of the Republic of Kazakhstan. 2014. “Nyrly Zhol: The Path to the Future.”

- Putz, C. 2018. “Kazakhstan Denies Asylum to Woman Who Fled China’s Camps in Xinjiang.” The Diplomat, October 10.

- Rastogi, C., and J. F. Arvis. 2014. The Eurasian Connection: Supply-Chain Efficiency along the Modern Silk Route through Central Asia. Directions in Development and Trade. Washington, DC: World Bank Group.

- Reeves, J. 2018. “China’s Silk Road Economic Belt Initiative: Network and Influence Formation in Central Asia.” Journal of Contemporary China 112 (27): 502–518.

- Rolland, N. 2019. “A China–Russia Condominium over Eurasia.” Survival 61 (1): 7–22. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00396338.2019.1568043.

- Rspadm. n.d. “The Chinese, Who Have to Set Up Equipment at the Creamery, Are Not Allowed into the Republic of Kazakhstan.” https://rspadm.ru/en/dizajjner/kitaicev-kotorye-dolzhny-nastroit-tehniku-na-maslozavode-ne-vpuskayut-v/

- Samruk-Kazyna. 2019. “Investment Opportunities of SWF Samruk-Kazyna: The List of Priority Assets and Investment Projects.” February 2019.

- Serikkaliyeva, A., A. Amirbek, and E. Ş. Batmaz. 2018. “Chinese Institutional Diplomacy toward Kazakhstan: The SCO and the New Silk Road Initiative.” Insight Turkey 20 (4): 129–152. doi:https://doi.org/10.25253/99.2018204.13.

- Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO). n.d. http://eng.sectsco.org/about_sco/. Accessed 4 March 2022.

- Shlapentokh, D. 2016. “Kazakh and Russian History and Its Geopolitical Implications.” Insight Turkey 18 (4): 143–164.

- Shtraks, G. 2016. “China’s One Belt, One Road Initiative and the Sino–Russian Entente – The National Bureau of Asian Research (NBR).” The National Bureau of Asian Research, 8 August.

- Simonov, E. 2019. “Half China’s Investment in Kazakhstan is in Oil and Gas.” China Dialogue (Blog), October 29.

- Song, W. 2014. “Interests, Power and China’s Difficult Game in the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO).” Journal of Contemporary China 23 (85): 85–101. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10670564.2013.809981.

- Swanström, N. 2007. “China and Central Asia: A New Great Game or Traditional Vassal Relations?” Journal of Contemporary China 14 (45): 569–584.

- Swanström, N. 2014. “Sino–Russian Relations at the Start of the New Millennium in Central Asia and Beyond.” Journal of Contemporary China 23 (87): 480–497. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10670564.2013.843911.

- The Astana Times. 2018. “Shymkent Oil Refinery completes modernisation, improves fuel and environmental standards.” https://astanatimes.com/2018/12/shymkent-oil-refinery-completes-modernisation-improves-fuel-and-environmental-standards/. Accessed 6 March 2022.

- Tian, H. 2018. “China’s Conditional Aid and Its Impact in Central Asia.” In China’s Belt and Road Initiative and Its Impact in Central Asia, edited by M. Laruelle, 21–33. Washington, DC: The George Washington University, Central Asia Program.

- Tjia, L. Y. N. 2020. “The Unintended Consequences of the Politicization of the Belt and Road’s China–Europe Freight Train Initiative.” The China Journal 83 (1): 58–78. doi:https://doi.org/10.1086/706743.

- United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). 2009. World Investment Report 2009. Transnational Corporations, Agricultural Production and Development. New York: United Nations.

- Vanderhill, R., S. F. Joireman, and R. Tulepbayeva. 2019. “Do Economic Linkages through FDI Lead to Institutional Change? Assessing Outcomes in Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan, and Kyrgyzstan.” Europe-Asia Studies 71 (4): 648–670. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09668136.2019.1597019.

- Vanderhill, R., S. F. Joireman, and R. Tulepbayeva. 2020. “Between the Bear and the Dragon: Multivectorism in Kazakhstan as a Model Strategy for Secondary Powers.” International Affairs 96 (4): 975–993. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/ia/iiaa061.

- Visser, O., and M. Spoor. 2011. “Land Grabbing in post-Soviet Eurasia: The World’s Largest Agricultural Land Reserves at Stake.” Journal of Peasant Studies 38 (2): 299–323. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2011.559010.

- Wandel, J. 2010. “The Cluster-Based Development Strategy in Kazakhstan’s Agro-Food Sector: A Critical Assessment from an Austrian Perspective.” Discussion Paper, No. 128. Leibniz Institute of Agricultural Development in Central and Eastern Europe (IAMO), Halle (Saale).

- Wang, Y. 2019. “Riding the Western Europe-Western China Highway: A Connection between Europe and Asia.” CGTN. https://news.cgtn.com/news/3d3d514e7749544f33457a6333566d54/index.html

- Womack, B. 2010. China among Unequals: Asymmetric Foreign Relationship in Asia. Singapore: World Scientific.

- Womack, B. 2016. Asymmetry and International Relationships. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- World Bank. 2019. “Total Reserves (Includes Gold, Current US$) – Kazakhstan.” https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/FI.RES.TOTL.CD?locations=KZ

- World Bank. 2021. “GDP (Current US$) – Kazakhstan.” https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD?locations=KZ

- World Integrated Trade Solution. 2021. “Trade Statistics by Country,” https://wits.worldbank.org/countrystats.aspx?lang=en Accessed 20 November 2021.

- Wu, H.-L., and C.-H. Chen. 2004. “The Prospects for Regional Economic Integration between China and the Five Central Asian Countries.” Europe-Asia Studies 56 (7): 1059–1080.

- Xinhua. 2006. “Pipeline carries Kazakh oil to China.” China Daily, July 30. https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/2006-07/30/content_652854.htm

- Xinhua. 2014. “中华人民共和国和哈萨赫斯坦共和国联合宣言” [People’s Republic Of China and Kazakhstan Joint Declaration].”

- Xinhua. 2015. “Chronology of China’s Belt and Road Initiative.” http://www.gov.cn/news/top_news/2015/04/20/content_281475092566326.htm

- Xinhua. 2018. “中哈农业合作结硕果:’这样的合作模式我们很需要’" [Sino–Kazakh Agricultural Cooperation Gained Fruitful Results: "We Need Such Cooperation Model Very Much"].” http://www.xinhuanet.com/2018-09/04/c_1123376038.htm

- Yau, N.. 2020a. “Tracing the Chinese Footprints in Kazakhstan’s Oil and Gas Industry.” The Diplomat, December 12. https://thediplomat.com/2020/12/tracing-the-chinese-footprints-in-kazakhstans-oil-and-gas-industry/

- Yau, N. 2020b. “Operational Reality of the Belt and Road Initiative in Central Asia.” OSCE Academey Special Issue China’s Belt and Road Initiative in Central Asia: Ambition, Risks and Realities, 41–72.

- Zakir, S. 2018. “Sino–Kazakhstan Agricultural Cooperation – A Case Study of Aiju Group.” Master’s diss., East China Normal University.

- Ziegler, C. E. 2016. “Great Powers, Civil Society and Authoritarian Diffusion in Central Asia.” Central Asian Survey 35 (4): 549–569. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02634937.2016.1228608.

- Zogg, B. 2019. “Kazakhstan: A Centrepiece in China’s Belt and Road.” CSS Analyses in Security Policy. doi:https://doi.org/10.3929/ETHZ-B-000362184.