Abstract

Scholars studying BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) have traditionally argued that it is a development-focused partnership and not a military/security-based alliance. Yet BRICS members have been deepening their security integration, and Russia and China have been creating an alliance in the background. Although BRICS middle powers have traditionally demonstrated an aversion towards alliances, Brazil actively deepened security cooperation among BRICS members during its BRICS presidency in Citation2019. How does Brazil view alliances in contemporary power competition? This study examines Brazil’s perceptions by introducing and analysing a new data set of Brazilian expert discourses on alliances since 1990 and using its participation in BRICS as an empirical case. It finds that Brazil does not consider its security relationships with BRICS states to be more significant than those with non-BRICS states. However, BRICS enables Brazil to advance its specific security agenda that becomes embedded within the group’s developmental orientation. While theorising about middle powers traditionally links these powers to international organisations, their pursuit of development–security agendas in rising power groups is an important front in contemporary power competition.

Introduction

A common thread in the literature on rising powers has been that they do not present – and do not have an intention to present – a military threat to the incumbent powers. Thus, the idea that they would form a traditional security alliance (alliance) – a ‘formal association of states for the use (or non-use) of military force, in specified circumstances, against states outside their own membership’ (Snyder Citation1997, 23) has been rejected. Scholars often argue that rising powers’ relationships operate in a normatively different environment where security might not even be a characteristic of allied relationships (Chidley Citation2014). Instead, rising powers pursue more flexible alignments, focus on issue-based convergence, and prioritise development-focused strategic partnerships (eg Wilkins Citation2012; Tyushka et al. Citation2019).

The BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) group, the premier entity for advancing rising powers’ global ambitions, and the rising powers comprising it have been at the forefront of such arguments. BRICS policymakers have emphasised that their governments were not against anyone and that alliances belonged in the past (Medvedev Citation2008; Xi Citation2019). BRICS itself has emerged as an independent group that seeks to reform international financial institutions, achieve a more diversified international monetary system, and support a more democratic and just multi-polar world order (BRIC Citation2009). In 2014, BRICS established the New Development Bank (NDB), which has approved billions of dollars in infrastructure financing projects. It also established the Contingent Reserve Arrangement to help with balance-of-payments crises. Simultaneously, the five BRICS countries have coordinated their policies on an ever-growing number of issues ranging from education and health to agriculture and security.

Although the security dimension has been slow to develop, recent trends demonstrate that BRICS is shifting towards a more active security agenda in such a way that the possibility of alliance formation cannot be excluded. First, BRICS has accomplished several security agenda milestones. The issue of United Nations Security Council (UNSC) reform lacked group-level consensus, but this did not prevent BRICS from coordinating at the UNSC (Brosig Citation2019). BRICS has hosted regular meetings of high-level security officials, who keep adding agenda items. It has also proved resilient to the recent India–China crisis: rather than ceasing security coordination, BRICS adopted a new Counter-Terrorism Strategy (Papa and Verma Citation2021). Second, alliance scholars have demonstrated the power of pivotal state champions in alliance formation (Henke Citation2019). Russia and China’s level of security engagement is already functionally alliance-like (Korolev Citation2019). In 2021, they deepened their military cooperation, which is likely to impact their participation in BRICS security cooperation. Finally, new security challenges and tensions with the US may further incentivise the development of common BRICS security policies. US defence strategies already acknowledge that rising powers’ strategic competition is the central challenge to US prosperity and security (US DoD Citation2018).

To assess whether a BRICS-wide alliance is feasible, it is crucial to examine how middle powers view such an alliance. Middle powers’ attitudes can shed light on intra-BRICS power dynamics, existing capacities and the possible effectiveness of such an alliance. If Russia and China seek to lead on security issues through BRICS, they need legitimacy and support from middle powers. However, the analytical perspectives currently dominating the study of middle powers overlook their views towards alliances and alliance formation in the context of rising power entities. Brazil represents a microcosm of these developments. As a middle power, it is expected to stay out of blocs and focus on UN multilateralism and regional security cooperation to advance international peace and security (Lopes, Casarões, and Gama Citation2020; Jordaan Citation2003). Given Brazil’s close relationship with the US and its self-perception as a liberal democracy and Southern power (Sotero and Armijo Citation2007), Brazil is the least likely country to enable the deepening of security coordination with Russia and China in BRICS. However, Brazil’s active leadership in the expansion of BRICS security cooperation, particularly its key role in endorsing the joint counter-terrorism agenda during its 2019 BRICS presidency, has challenged this view.

This study asks: How does Brazil view alliances in contemporary power competition? It examines Brazil’s attitudes by introducing and analysing a new data set of Brazilian expert discourses on alliances since 1990 and using its participation in BRICS as an empirical case. First, it introduces a database of 452 Brazilian academic studies on alliances and on Brazil’s relations with other BRICS countries and the US. These studies were published in top Brazilian international relations (IR) and political science (PS) journals between 1990 and 2019. Data from this database is then used to examine how alliances are conceptualised in Brazilian academia. A new statistical model is applied to systematically assess whether Brazil demonstrates a preference for BRICS countries as security allies. Second, key policy documents from the same period are analysed to assess whether Brazilian policymaking demonstrates comparable findings and indicates a potential for BRICS alliance formation.

The findings demonstrate that Brazilian experts use the alliance concept to describe a wide range of international relationships, but rarely use it to convey a traditional security alliance model. Brazil’s relations with BRICS states are predominantly focussed on economic cooperation and global governance reform. Brazil does not display greater preference for other BRICS members as security allies (either bilaterally or multilaterally) over its other diplomatic relationships. Nevertheless, Brazil’s intra-BRICS security cooperation is deepening – mostly through the overall strengthening of BRICS as an entity and issue linkages with development-focussed cooperation. Thus, as we argue, Brazil has adopted a strategy of ‘development–security alliance’ formation with the other BRICS countries. Unlike traditional alliance formation, development–security alliance formation refers to a new alliance-building strategy: rising powers engage informally around mutual interests on developmental, primarily economic and global governance issues, build trust and gradually expand their cooperation to encompass security issues. Although mutual security interests are not robust enough to justify an extensive security focus, shared revisionist goals and development opportunities promote the formation of the development–security alliance.

The next section introduces the puzzle of Brazil’s view of alliances in BRICS in the context of middle powers’ behaviour in contemporary power competition. The third section discusses the research design applied to investigate Brazil’s view of alliances. The fourth and fifth sections present quantitative and qualitative findings from academic and policy data, respectively. The last section concludes with implications for further research and policymaking.

Rising middle powers in contemporary power competition: Brazilian alliance perspectives

Scholarship on Brazil’s foreign policy treats Brazil both as a middle power and as a rising power (eg Selcher Citation2018; Lopes, Casarões, and Gama Citation2020). Conceptually, these two identities lead to different expectations about Brazil’s attitude towards alliances. Middle powers are ‘states that are neither great nor small in terms of international power, capacity, and influence, and demonstrate a propensity to promote cohesion and stability in the world system’ (Jordaan Citation2003, 165). Because of their limited capacities and relatively privileged position in the global order, they tend to support the existing system and seek to stabilise it through niche diplomacy (Flemes Citation2007, 10, Flemes and Wojczewski Citation2010). They had no special place in regional blocs historically, and they pursue UN multilateralism, build consensus in international disputes, and are seen as stabilisers and legitimisers in the international system (Cooper, Higgott, and Nossal Citation1993, 19–27; Jordaan Citation2003, 167–169).

Unlike traditional middle powers such as Canada or Australia, Brazil is often categorised as an ‘emerging middle power’ (Jordaan Citation2003, 168). Such powers are often located in the global periphery or semi-periphery, have a fast-growing economy, and face domestic issues such as weak democracy and high levels of income inequality. They selectively support the incumbent order and actively seek regional leadership (Nolte Citation2010; Buzan and Wæver Citation2003). Although they can criticise the existing hegemon, they do not seek radical systemic change (Jordaan Citation2003). However, being an emerging/rising power – a state pursuing global status and seeking to act as a rule-maker and norm-setter in global governance – creates tensions with the hegemon. Yet neither the middle power nor emerging/rising power frameworks can explain why Brazil would enable the deepening of BRICS security cooperation across an ever-growing number of policy issues. Scholarship on Brazil’s view of alliances and the evolution of a common BRICS security agenda offers additional insights.

Brazil’s nonalignment and engagement in soft-balancing groups

Brazil’s foreign policy portfolio does not include traditional security alliances with mutual defence pacts.Footnote1 Over the past 200 years, Brazil has experienced few significant military conflicts with its neighbours; rare examples include the Cisplatine War and the War of Triple Alliance in the nineteenth century. The lack of external security threats and its geopolitical position have led it to follow a strategic culture of nonalignment, and Brazil participated in the Non-Aligned Movement (Pontes Citation2016). While Brazil stayed out of Cold War blocs, it followed a middle power path: focussing on regional security and enhancing international cooperation and coalition building to improve global governance.

Since the abolition of the military regime in 1985, Brazilian leaders have aimed to transform the nation into a global power (Amorim Citation2010). Brazil has criticised the uneven distribution of economic and political power between the Global North and the Global South (Hurrell Citation2008, 52). It positioned itself as a champion of development by hosting the 1992 Rio Summit advancing sustainable development. It has promoted South–South cooperation and engaged with other rising powers to better integrate development considerations into trade and climate negotiations. Brazil’s economic growth facilitated its global interactions. Since the Lula administration (2003–2011), Brazil has moved ‘beyond forming just coalitions to reach specific goals’ towards ‘intending to develop long-term alliances to help with the goal of seeking more space […] in multilateral organizations’ (Silva Citation2015, 150). It called for ‘democratization’ of IR and ‘stimulating multipolarity’ (Visentini and Silva Citation2010, 55).

Brazil co-founded two rising power groups: the India, Brazil, South Africa Dialogue Forum (IBSA) in 2003 and BRIC in 2009 – to achieve such goals. Both groups have employed internal policy coordination and soft balancing – the use of non-military tools to delay, frustrate and undermine the superpower’s unilateral policies (Pape Citation2005, 10; Flemes Citation2007). IBSA has sought to advance South–South cooperation in a more focused way with smaller membership and ‘advance human development by promoting potential synergies among the members’ (Indian Ministry of External Affairs (Indian MEA) Citation2004). It developed intergovernmental and transnational initiatives, sought to improve trade among the three countries and align their international trade policies, created a development fund, and fostered policy coordination on transport, energy, health, security and other issues.

While IBSA enabled Brazil to strengthen its position in trade negotiations and gain greater voice in global governance through sectoral initiatives, it has not met Brazil’s global security needs. The reform of the UNSC has been Brazil’s priority since the founding of IBSA and ‘became a principal leitmotif’ of IBSA summits (Stuenkel Citation2014, 25). However, this agenda has stalled and remains the group’s urgent priority (Hindustan Times Citation2020b). Nonetheless, intra-IBSA security cooperation has been effectively cultivating the maritime link between the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans. The sucess of its naval cooperation has expanded to other military sectors and supported the development of local defence industries (South African Government Citation2010).

BRICS follows IBSA’s transregional design, but has a stronger soft balancing potential: its members comprise 41% of the world population and have 24% of the global gross domestic product (GDP) and a share of over 16% in global trade (BRICS Citation2021). While IBSA countries have a shared sense of identity as powers from the Global South and as liberal democracies, BRICS is truly heterogeneous. It adopted much of IBSA’s agenda but has not replaced IBSA (Sidiropoulos Citation2013). BRICS has been particularly active in aligning the countries’ development policies and reforming international financial institutions. Through BRICS, Brazil has been at the forefront of mapping new avenues in development finance, questioning the dollar’s hegemony and shaping NDB’s ‘new development’ approach in practice. The NDB’s creation was a success, and the bank provided crucial financial assistance during COVID-19. Brazil’s close engagement with BRICS helped it become one of the most favoured beneficiaries in International Monetary Fund (IMF) voting quota reforms since 2010. In 2021, Brazil has 2.2% IMF voting shares, a higher percentage than many developed nations such as Canada and Australia (IMF Citation2021, 21). Brazil’s BRICS membership also enhanced its status despite its lagging economic growth and helped deepen its ties with China and other powers. The number of issues and community-building activities BRICS engages with grows every year.

A common security strategy for the BRICS and the possibility of a BRICS alliance?

Brazil’s attitude towards BRICS security cooperation and its possible expansion is a high-stakes issue in contemporary power competition. As we argued in the introduction to this article, the tensions in the US–Russia/China relationship and the deepening of Russia and China’s military cooperation highlight the relevance of middle powers in the formation of a common BRICS security strategy.

Since the late 1990s, Russia has been creating an ‘anti-hegemonic coalition’ – of states committed to resisting American dominance of the international system (Ambrosio Citation2005, 78). It proposed the Russia–India–China (RIC) coalition to empower RIC states as alternate poles to the US that can prevent it from imposing unilateral decisions that conflict with their respective security interests. India and China initially rejected Russia’s attempts to create an anti-US bloc and were embroiled in their own conflicts. However, Russia gradually deepened its bilateral defence cooperation with China and India and was able to initiate cooperation within the RIC. In 2013, the Russian National Committee on BRICS Research organised a conference to discuss ‘institutionalizing military cooperation among the BRICS countries’ (Salzman Citation2019, 79). Since 2014, security themes have become increasingly prominent in BRICS summits (Panova Citation2018). Russia’s close security coordination with China is an opportunity to expand the BRICS security dimension. Yet even if Russia and China seek to scale their security relationship by integrating some of its components into BRICS, creating a BRICS alliance requires credible inclusion of middle powers’ strategic interests – not only because leaders need followers (Schirm Citation2010), but because cooperation is unlikely to be successful unless the interests of middle powers are included. For example, China proposed a BRICS free trade zone, which IBSA countries rejected as they worried that Chinese economic dominance might slow their industrial development (Jayaswal and Laskar Citation2020).

Brazil has supported the evolution of BRICS security cooperation, particularly in the context of reforming global security governance and the UNSC. While UNSC reform has yet to materialise, BRICS security cooperation evolved when BRICS countries became UNSC members in 2011 and developed more coordinated responses to global crises. Brazil voted with Russia (and other BRICS countries) on UNSC Resolution 1973 (regarding the intervention in Libya) and abstained with India and South Africa when China and Russia vetoed the draft resolution to condemn the Syrian regime (Abdenur Citation2016). Having studied 20 BRICS responses to crises in Libya, Syria, South Sudan and Ukraine, Brosig (Citation2019) found that BRICS acted together to prevent some US- and EU-preferred outcomes.

Brazil has also acted as a security policy entrepreneur. When China and Russia firmly opposed the Responsibility to Protect (R2P) doctrine due to sovereignty concerns, Brazil proposed and integrated the Responsibility while Protecting (RwP) doctrine into the BRICS agenda. Brazil also envisioned the creation of a BRICS undersea communications cable agenda to shield Brazil’s Internet traffic from US surveillance following revelations of US spying on Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff. Neither of these initiatives materialised. Subsequently, Brazil’s international security agenda in BRICS evolved around ‘three pillars’: illicit financial flows, financing of terrorism, and cybersecurity (Giesteira Citation2021). Yet Brazil’s most consequential initiative in terms of enhancing BRICS institutional output in the security arena is in counterterrorism. Brazil’s hosting of the 2019 BRICS summit enabled the establishment of a counterterrorism working group that paved the way for the Counter-Terrorism Strategy in 2020.

A critical approach to Brazil’s BRICS engagement would note Brazil’s inability to mobilise other members around its priorities such as UNSC reform or to gain BRICS support for its efforts to manage the crisis in Venezuela (France 24, Citation2019). Similarly, critics would find further security integration unlikely. BRICS countries would struggle to define joint security threats, especially with India and China being military rivals and without a clear leader of BRICS security policy. Finally, scholars also suggest that BRICS has not helped Brazil enhance its international status as expected and that the deepening of its relationship with the US would be more beneficial to its interests (Røren and Beaumont Citation2019). While the Lula administration advocated for a strong orientation towards BRICS, the Bolsonaro administration demonstrated a tendency towards a closer alignment with the US on security issues (Paraguassu and Alper Citation2019).

Overall, the extant literature expects that Brazil’s role as a middle rising power and its tradition of non-alignment create an aversion towards alliances and the creation of a common BRICS security strategy. Yet existing approaches fail to explain how during the contemporary power competition featuring a contentious US–China/Russia relationship, Brazil emerges as an enabler and promoter of the BRICS security agenda. Brazil’s attitude towards BRICS reflects a larger puzzle of alliance formation in an era when traditional alliances are not the dominant means of security cooperation. Scholars have established that the traditional alliance concept does not reflect the way states from the Global South form and maintain their most critical international relationships (Chidley Citation2014, 155). These states emphasise the developmental dimensions of allied relationships, ‘bandwagon for profits’ and downplay security ties (see also Schweller Citation1994). However, the Brazil puzzle suggests that development–security linkages are more complex and that contemporary strategies not only target specific economic gains but also pursue larger scale goals including status-seeking and geopolitical positioning (see also Amorim Citation2010).

Middle power theorising remains underdeveloped in terms of understanding Brazil’s security strategies in contemporary power competition, in which rising power groups serve as key platforms for counter-hegemonic mobilisation. Thus, we need to clarify the role of rising middle powers in deepening the security dimension of such entities. This study addresses this gap. Focusing on Brazil’s view of alliances, it contributes new empirical data to establish Brazil’s alignment preferences and examine how Brazil advances its global security ambitions through rising power groups.

Research design: examining the Brazilian view of alliances

To understand how Brazil views alliances, this study systemically examines Brazilian academic discourses and government policy documents. First, it analyses Brazilian academic discourses to investigate how local experts use the alliance concept and understand which issues and geographic orientations emerge in their studies. Second, it develops a novel statistical approach, using data on academic articles to construct confidence intervals estimating Brazilian policy preferences. Finally, this study examines policy documents to investigate whether Brazil’s BRICS engagement includes alliance formation activities. The combination of academic and policy data enables us to construct a systematic understanding of Brazil’s view of alliances. We note that knowledge and policymaking are products of ‘interactions between the study of policy and the making of policy, which leads over time to social changes in directions that scholars discern and dispute’ (Nau Citation2008, 635). That said, we are not making any causal claims about the impact of theoretical discourses on practice and vice versa, but simply illustrating both sides of the IR debate. Our three-step research design is outlined below.

First, this study constructed a new database of 452 academic articles published in the top five Brazilian IR and PS journals between 1990 and 2019 to analyse Brazilian views of international alliances.Footnote2 They are: Revista Brasileira de Política Internacional; Contexto Internacional/PUC-Rio; Carta Internacional/ABRI; Revista Estudos Internacionais; and Política Externa. Alliance-related studies are identified by conducting a keyword search for ‘alliance’ (alianca) and related terms, including ‘partnership’ (parceria), ‘alignment’ (alinhamento) and ‘coalition’ (coalizão). Since many Brazilian studies on Brazil’s relations with major powers discuss interactions without using alliance-related terms, we use a combination of the keywords Brazil + China or Brazil + other BRICS countries and the US. To avoid articles randomly mentioning terms, an alliance (or any keyword) needs to be mentioned at least five times in the main text of the article to qualify for the database. We exclude articles that examine alliances within domestic politics and business.

To investigate alliance-related behaviour in relation to regional and issue areas, we used the article summary to label each article by its dominant issue area and geographic orientation. Issue area labels are military security;Footnote3 economics including finance, trade and development;Footnote4 global governance reform, including studies of one or many global institutions and their reform;Footnote5 climate change; and technological, cultural, medical and educational cooperation. Geographic orientation labels include Brazil (articles focusing on the internal formation of Brazil’s foreign policies); Europe; Latin America and South America; Africa (except South Africa); the US; Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries, except the US; Eurasia and the Middle East; BRICS as one unit of analysis; China, Russia; India; South Africa; and the rest of Asia, except for China and India. Articles that discuss more than one issue or geographic area are labelled accordingly. These articles are first statistically analysed to examine the use of alliances and related frameworks, and then their content is examined to understand how these concepts are applied. Since changes in administration can have a significant impact on Brazilian foreign relations, data is divided by presidencies (Cason and Power Citation2009, 122–124). Finally, labelling each article enables us to explore the correlations between its geographic orientation and primary issue area. Thus, if Brazilian academia frames BRICS as a security alliance, the study should show that security issues are strongly correlated with both BRICS as a group and with the individual members. If Brazil tends to downplay the security aspects in its engagement with BRICS, the correlation between the BRICS geographic label and security issues will not be significant.

Second, using the data set, this study develops a statistical tool to systematically examine the prominence of Brazil’s security cooperation with BRICS vs non-BRICS countries. For example, we may observe X% of all articles that study Brazil–BRICS relations discuss security issues, which means there is an X% chance Brazilians will consider security issues when Brazil–BRICS relations are studied. The precise value of X is unknown due to random measurement errors, but the database allows us to estimate the confidence intervals for the value of X. Thus, we construct a 95% confidence interval in which the probability of considering security issues in Brazil’s cooperation with BRICS would fall, and another 95% confidence interval in which the probability of considering security issues in Brazil’s cooperation with non-BRICS countries would fall. By comparing these two sets of confidence intervals, we can determine whether security issues are more prominent in Brazil–BRICS relations than in Brazil’s relations with other foreign countries.

The final method employed in the study involves a qualitative examination of policy documents to test whether Brazil’s BRICS engagement shows a propensity for alliance formation. We draw on Alexander Korolev’s (2020) framework of three stages of alliance formation, which uses a set of objective criteria for military alignment, and apply them to measure whether Brazil’s security cooperation with these organisations displays early, moderate or advanced cooperation. This analysis relies on defence policy documents and strategies, all BRICS joint declarations (2009–2021), other data publicly available from BRICS government websites, and international arms trade data (SIPRI (Stockholm International Peace Research Institute) Citation2021). We discuss the findings in the broader context of Brazil’s security policy development.

Framing alliances in Brazilian academic discourses and preference for BRICS cooperation

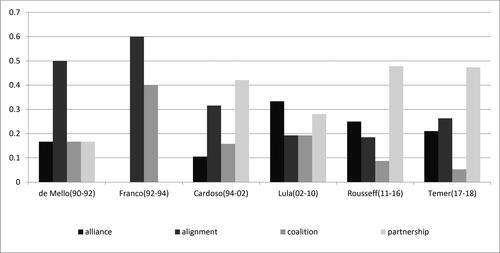

Brazilian academics, as the data analysis demonstrates, widely apply ‘alliance’, ‘coalition’, ‘partnership’, and ‘alignment’ concepts to define Brazil’s foreign relations. Yet these concepts are not clearly delineated and are often used interchangeably. Although alliances are present in discourses, they refer to cooperation in various issue areas outside the security realm. shows the prevalence of these concepts under various administrations as percentages of all articles published in that era, respectively.

Figure 1. The percentage of articles using alliance-related concepts under different administrations.

The alliance concept has long been present in the Brazilian academic community. However, it often refers to cooperation on non-security issues, economic ones in particular. Only 19% of articles using the alliance concept apply it in a security context. The remaining 81% of articles use it in an all-encompassing way to describe various non-security oriented relationships, referring especially to developing countries’ cooperation on global economic governance and climate change (Vaz Citation1999). Only 23% of all articles that apply the concept of alliances discuss Brazil’s relations with BRICS as a group or with individual BRICS countries. None of these articles are security-focussed, but all discuss Brazil’s participation in BRICS from the perspective of reforming global institutions, especially regarding financial and development issues.

The partnership concept is the second most used concept in our database. Indeed, it is the most frequently used concept in the Rousseff and Temer era (2011 to 2018). Although Brazilian academics do not have a consensus definition of a partnership, some common features emerge. First, unlike alliances, which dissolve when shared external threats vanish, partnerships are ‘cooperative relations between states to identify shared long-term goals’ (Farias Citation2013, 31). Second, partnerships have a developmental dimension: partnering with more powerful states helps develop the Brazilian economy rather than generating power competition dynamics (Becard Citation2013, 61). Third, a successful partnership in one area can facilitate closer relations in another, creating issue linkage opportunities. Some studies specifically highlight how Brazil builds shared identity through partnership relations (Farias Citation2013, 24; Silva Citation2015, 158). For example, Brazil’s partnerships with IBSA or BRICS strengthen these countries’ shared identity as the leaders of the Global South and develop their functional cooperation (eg cooperation on climate change, trade disputes, UNSC reform) and gradually challenge hegemony (Oliveira Citation2005, 66). Finally, despite the fact that security cooperation is not a dominant theme in Brazil’s understanding of partnerships, it is not excluded from it. Brazil can use partnerships to actively pursue its security and geopolitical interests without the constraint of binding commitments. For example, Brazil’s strategic partnership with Turkey enabled Brazil to engage as an external mediator during the Iran nuclear crisis (Ozkan Citation2010).

Compared to partnership and alliance concepts, alignment and coalition concepts are less common, but their use shows similar patterns: the conceptual boundaries of all four concepts are often blurred. None of these concepts exclude security cooperation, but it often carries less weight than economic issues. While allied cooperation often starts from economic issues, successful cooperation on these issues can create mutual trust, spill over into other issue areas and deepen relationships.

Brazil’s preferred relationship with BRICS

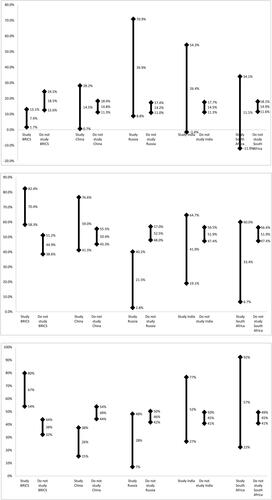

To systematically investigate Brazil’s attitude towards BRICS, we use a new statistical approach. We split the data into two groups: articles that study BRICS and those that do not. In the BRICS-study group, 7.4% of the articles discuss security issues. In the non-BRICS study group this number is 18.5%. Given the sample size and the likelihood of mentioning security issues in BRICS studies, we construct 95% confidence intervals. As reported in the first column of the top graph in , one can be 95% sure that when Brazilians study BRICS-related foreign policy, the likelihood of considering security issues is 1.7–13.1%. The likelihood of considering security issues in the non-BRICS group is 12.6–24.5%. Since the confidence intervals for the two groups of data overlap, one cannot confidently claim that Brazil considers BRICS as more or less of a valuable security partner than other nations and organisations.

Figure 2. Does Brazil see Brazil-India-Russia-China-South Africa (BRICS) (and BRICS countries) as more prominent for security/economic/global governance reasons?

Similarly, other columns in the top graph of show that when Brazil’s bilateral relations with individual BRICS countries are considered, Brazilians do not see these countries as more prominent security partners than other countries. The middle graph in suggests that for economic collaboration, Brazil prioritises BRICS (as a group) over other countries and organisations. However, in Brazil’s relations with Russia, economic cooperation is less pronounced than in Brazil’s relations with other BRICS countries. The bottom graph in shows that Brazil sees BRICS as a whole as more important in the context of global governance reform than its relations with other countries/organisations. Brazil’s global governance interests are also better served through multilateral channels at the BRICS level than through bilateral channels within BRICS. These findings support the qualitative analysis in the previous section: BRICS is important for Brazil as a multilateral platform of interstate economic cooperation and global governance reform. While Brazilian scholars do not exclude security cooperation from their discussions on BRICS, they do not prioritise it in their conceptualisation of Brazil–BRICS relations.

Trends in Brazilian understanding of BRICS alignments

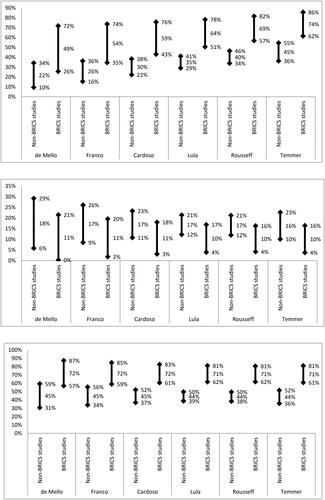

This section applies panel data analysis to examine how Brazilian views on BRICS have changed under different presidential administrations. Since BRICS did not exist in the 1990s, we expand the definition of ‘BRICS-study’ articles to include the data from the 1990s in this analysis. The ‘BRICS studies’ before 2008 refer to articles studying Brazil’s relations with individual BRICS countries; the ‘BRICS studies’ after 2008 include articles studying Brazilian relations with individual BRICS countries and with BRIC(S). breaks down Brazilian views on BRICS under different presidential administrations.

Figure 3. Does Brazil see Brazil-India-Russia-China-South Africa (BRICS) as more prominent than other nations and organisations for security/economic/global governance reasons under different administrations?

The results show that since the Cardoso presidency (1995–2002), Brazilian scholars have viewed Brazil’s relationships with BRICS countries as more valuable than others for global governance reform and economic issues, but not for security issues. Such trends are consistent between 1995 and 2019.

Brazil and security alliances in practice

To explore whether Brazilian foreign policy practices are noticeably different from the discussed findings, we systematically examine Brazilian government documents. Brazil does not have any formal alliances or defence treaties with BRICS countries. Overall, Brazil’s major security documents do not use the security alliance concept, and the 2008 Defense White Papers and National Security Strategy officially define Brazil’s relations with BRICS under the strategic partnership category (MoD Brazil Citation2008, 18–19). They state that Brazil should leverage its political relations with BRICS to achieve better representation in established international institutions (political and economic ones) and to restructure them (MoD Brazil Citation2008). However, BRICS engagement is not highly ranked on the list of Brazilian security priorities. The 2010 Brazilian Army’s International Activities Priority Plan divided the world into five regionsFootnote6 and ranked them by priority in Brazil’s security policy. BRICS countries ranked fourth out of the five regions (Marcondes and Barbosa Citation2018, 146).

Over the past decade, Brazilian security documents have encouraged deeper cooperation with BRICS. The 2012 National Defense Policy urges Brazil to follow international political and economic developments and exploit opportunities to explore the potential of new associations like BRICS (MoD Brazil, Citation2012). The 2017 Defense Scenarios 2020–2039 predicts that the rise of BRICS will ‘increase the importance of [the] economic domain in the exercise of national power’, and notes that Brazil should strengthen its economic cooperation with BRICS (MoD Brazil Citation2017, 14–16). Additionally, the Brazilian government has expressed its preference for security cooperation with some BRICS countries over others. The 2017 Defense Scenarios expresses deep concerns over the implications of US–China tensions: ‘A possible Chinese military expansion … alongside Africa’s Atlantic coast could lead to a reaction from the US and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), with increased military deployments to the South Atlantic’ (MoD Brazil Citation2017, 14–16). It is therefore important for Brazil to keep its naval missions in the Gulf of Guinea to protect its interests. Brazil’s efforts to better define the South Atlantic region and project leadership there could be advanced through cooperative ventures with other BRICS members, particularly with South Africa. Although BRICS has discussed the threat of maritime piracy as a problem in this region, the full potential of South Atlantic cooperation remains unrealised.

Examining progress towards a BRICS security alliance

To further clarify the nature of Brazil–BRICS security cooperation and examine its development, this analysis uses Alexander Korolev’s (2020) three-stage approach to alliance formation that measures whether countries are at an early, moderate or advanced stage of military alignment.

According to the framework, the early stage of alliance formation includes the establishment of confidence-building measures and mechanisms of regular consultations. Brazil has jointly established several mechanisms for dialogue and confidence building with other BRICS countries. BRIC(S) foreign ministers have been meeting regularly since 2008. National security advisors have been meeting informally since 2009 and formally since 2013. BRICS has also established issue-specific working groups for counterterrorism, cybersecurity, and security in the development of information and communication technology (ICT). These mechanisms were effective and particularly visible when BRICS coherence was tested during the India–China conflict in 2020. BRICS cooperation continued at the highest levels despite the border clash in June 2020, and BRICS deepened rather than restrained its security cooperation.

Consultations and confidence-building measures have helped Brazil contribute to and influence the agenda of BRICS security cooperation. Brazil chose not to pursue some security issues that, while relevant to Brazil, were unlikely to reach BRICS-level consensus. Such contested issues include responding to the political crises in Venezuela and Bolivia, where individual BRICS countries held opposing views. Confidence-building mechanisms also emerged at the sub-BRICS level. Brazil’s proposal of the RwP doctrine, which emphasised the use of preventive diplomacy and principles for conducting foreign military interventions, is a case in point (Viotti Citation2011). Through the IBSA platform, Brazil gained confidence that India and South Africa would support the RwP proposal, even if China and Russia were firmly against it (Garwood-Gowers Citation2016). Although Brazil abandoned the RwP proposal in 2013, it effectively experimented with mobilising sub-BRICS coalitions around its agenda.

The moderate stage of alliance building involves engagement in arms trade, military technology transfers and regular joint exercises. When these activities are considered, the evidence of alliance building is mixed. Brazil has conducted limited military technology exchanges and arms trade with other BRICS countries, and some of its efforts in this area have failed. For example, Brazil provided jungle warfare training to the Chinese Army and aircraft carrier crew training to the Chinese Navy (Mahon Citation2015; StrategyPage Citation2013). Brazil has also sought military technology transfers from Russia such as the technology for nuclear-powered submarines, the Pantsir S-1 anti-aircraft artillery system, and rocket and satellite technology. However, the purchase of a nuclear-powered submarine from Russia in 2008 failed due to a loss of interest from Moscow, and the purchase of the Pantsir S-1 missile system failed in 2013 due to a change in administration and economic instability in Brazil (Dall’Agnol, Zabolotsky, and Mielniczuk Citation2019).

Brazil has also held bilateral joint exercises with other BRICS countries, but these have not been routinised. For example, China held its first joint naval exercise with the Brazilian Navy when it sent a fleet to visit Rio in 2013. It did so again in Citation2019. Brazilian military exercises with South Africa and India within the IBSA framework are more routinised (Indian Navy Citation2019). IBSA countries initiated naval exercises in 2008 (before BRICS was established) and steadily increased the scope of the exercises to involve ships, aircraft and special forces from all three countries. The goal is to strengthen mutual trust and interoperability and to share best practices. Moreover, this security cooperation is also a mechanism for creating a shared democratic and Southern identity and ensuring the continuity of IBSA’s social-political structure (Rooyen Citation2017).

Arms trade between Brazil and other BRICS countries is much smaller than Brazilian weapons exchanges with Western countries.Footnote7 Brazil only signed four arms deals with BRICS countries between 2008 and 2019: importing 150 anti-tank missile systems, 12 Mi-35 helicopters, and 430 portable antiaircraft missile systems from Russia and exporting three ERJ-145 transport aircraft to India. In total, intra-BRICS arms trade was USD 175 million in this period. Meanwhile, Germany, the US and France are Brazil’s top three arms suppliers. Brazil had 69 arms deals with Germany, the US and France between 2008 and 2019. In this period, Brazilian officials purchased USD 1.344 trillion of armoured personnel carriers, antisubmarine warfare (ASW) helicopters, ship engines, radar, torpedoes and transport aircraft from Germany, the US and France.

For the advanced stage of alliance building, there is no evidence that Brazil intends to have an integrated military command, joint troop deployment and formal alliance treaties with the other BRICS countries. In short, Brazilian security relations with BRICS countries contain well-established consultation and trust-building mechanisms, but they have yet to achieve higher levels of security cooperation such as joint exercises, military technology transfers and arms deals.

Brazil’s security cooperation with the US and regional organisations such as the Organization of American States (OAS) and the Union of South American Nations (UNASUR) has also only reached the second stage of alliance building. However, various administrations have had different security and alignment priorities. For example, Brazil used to cooperate with the OAS on regional security initiatives in Latin America. However, a Lula administration 2008 Defense White Paper referred to the US as ‘the threat of far superior military forces in the Amazon region’ (MoD Brazil Citation2008, 48).

To propel regional integration and mitigate US influence in regional governance, Brazil led the creation of UNASUR in 2008 (Weiffen, Wehner, and Nolte Citation2013, 381–384). Brazilian defence minister Nelson Jobim clarified that UNASUR’s newly established Council of South American Defense (CDSA) ‘would not have the structure of a full alliance’ (Mijares Citation2018, 263). With the CDSA, UNASUR successfully constructed confidence-building mechanisms, increased the transparency of security policymaking among its members, and promoted CDSA engagement in UN peacekeeping missions and their training through the newly established Joint Peace Operation Centre of Brazil (Vitelli Citation2017, 2; Bragatti Citation2019, 79). However, the CDSA was less successful in developing a joint defence industry, increasing arms trade between UNASUR members, and building a security community (Vitelli Citation2017, 3). In 2018, Brazil suspended its UNASUR membership as the organisation became paralysed by divisions between its rightwing and leftwing members. It created the Forum for the Progress and Development of South America (PROSUR) to defend democracy, promote trade and manage interstate disputes in South America (Burges Citation2018).

Under President Bolsonaro’s leadership, Brazil has significantly enhanced its security relations with the US and NATO. Indian Navy Citation2019, the US designated Brazil as a ‘major non-NATO ally’ (Samuels Citation2019). Brazil and the US also established the Long-standing Political-Military Dialogue and a New Strategic Partnership Dialogue in September 2019, and Brazil hosted joint exercises with the US Southern Command. Despite the Bolsonaro administration’s initial prioritisation of the US relationship and devaluation of BRICS, BRICS demonstrated its resilience and its usefulness as a platform for security innovation.

Security cooperation through issue linkages?

BRICS’s trajectory as an institution demonstrates mobilisation in response to the 2008 financial crisis and development policy coordination based on a like-minded approach to development. As financial and development-focused cooperation became institutionalised, BRICS’s security cooperation has expanded. Issue linkages, or ‘simultaneous discussion(s) of two or more issues for joint settlement’ (Poast Citation2012, 278), have been an important method for incorporating security issues into the BRICS agenda because they enabled each BRICS member to create benefits in areas that they would otherwise not find as valuable.

The issue linkage mechanisms within BRICS are particularly important at the finance–Internet–security nexus. BRICS cooperation on counterterrorism reflects this nexus and has been a major leap in terms of deepening BRICS security collaboration. Brazil has been particularly active in developing the BRICS counterterrorism agenda. In 2017, it proposed to establish a BRICS Intelligence Forum to intensify the fight against terrorism (BRICS Citation2017). When President Bolsonaro hosted the BRICS summit during Brazil’s BRICS presidency, he listed ‘invigoration of the cooperation on the fight against transnational crime, especially against organized crime, money laundry and drug traffic’ as security priorities (MoFA Brazil Citation2019). This agenda was framed in the context of counterterrorism during the 2019 summit, particularly as Brazil’s interests were intrinsically linked to India’s advocacy for strengthening the counterterrorism agenda (Hindustan Times Citation2020a). At the summit, BRICS established a ‘Counter-Terrorism Working Group’ with five subgroups to address international terrorist financing, the use of the Internet for terrorist purposes, counter-radicalisation, cross-border terrorism, and capacity building (Roche Citation2019).

In 2020, BRICS adopted a Counter-Terrorism Strategy, which links various issues BRICS members are interested in: cooperation on intelligence information sharing, joint actions over border control, financial information sharing on terrorist financing, joint actions to monitor terrorists’ social media activities, building common legal frameworks against terrorism, coordinating UN positions to oppose Western countries’ ‘double standards’ on terrorism, and technology exchange to build counterterrorism capacity (BRICS Citation2020). Some of these activities, such as constructing common legal frameworks to coordinate BRICS countries’ security policies, move BRICS towards the advanced stage of alliance building.

The comprehensive nature of the Counter-Terrorism Strategy reinforces the finance–Internet–counterterrorism nexus. BRICS’ ability to effectively accomplish this agenda lies not only in having designated BRICS High Representatives for Security to review the implementation of the strategy, but also in having extensive relationships among finance ministers, the Financial Action Task Force, and other officials and bodies that can help with this portfolio.

Conclusion

This study investigated Brazil’s perspectives on alliances and its propensity to support a BRICS-wide alliance. It offers two key contributions to the existing literature on alliances and alliance formation with respect to the rise of new powers. First, this study systematically examines Brazil’s conceptualisation of alliances and its approach to BRICS security cooperation using new empirical data. It demonstrates that Brazil’s framing of alliances is broader than traditional security alliances and that it emphasises international economic relations and global governance reform. Yet when Brazil’s engagement with BRICS is assessed against objective criteria for measuring various stages of traditional alliance formation, Brazil is shown to have made great progress in military/security coordination in a short period of time. These findings challenge the existing frameworks. Brazil’s engagement in military coordination through small, long-lasting activist platforms departs from both traditional middle power behaviour and soft-balancing coalitions that do not involve military components. Nonetheless, neither Brazil’s preferences nor BRICS-wide security coordination is likely to support a new two-bloc alliance system with BRICS as part of the Russia–China bloc in the near future. Our findings show how rising powers that initially lack robust security ambitions can see these ambitions develop, and how middle powers within rising power groups not only follow but actively co-champion security agendas. These findings shed new light on middle powers’ engagement in the global-level politics of contemporary power competition.

Second, our findings call for a new analytical approach to better accommodate rising middle powers’ aversion towards alliances and the related Cold War mindset, but also acknowledge their growing security ambitions. Brazil’s participation in BRICS and the general trajectory of the group illustrates this approach, which we label ‘development–security alliance formation’. Cooperation starts with a strategic partnership on developmental (economic and global governance) issues, deepens, and evolves through sub-coalitions and multiple cooperation streams. Security champions gradually incorporate security topics they find relevant (eg Brazil/India and counterterrorism or Russia and strategic security coordination), and then develop deeper cooperation. While such collaboration might never turn into a formal alliance, the countries’ close strategic cooperation can exert an engagement pull on states. Alliance members find the breadth of cooperation beneficial and exit costly. New pathways – issue linkages and intra-BRICS strategic partnerships – enhance security coordination.

While this approach creates an opening for US adversaries’ anti-hegemonic mobilisation, it also enables Brazil to focus on its development while addressing its own security ambitions as a part of multiple, complex and long-term strategic commitments that serve its national interests and global leadership ambitions. More broadly, cooperating exclusively on military security is no longer considered beneficial at a time when human development concerns (eg the COVID-19 pandemic and climate change) have redefined security needs.

Empirically, this research combined a qualitative conceptual analysis, a statistical model and an analysis of policy documents to provide comprehensive evidence of Brazil’s view of alliances. It is important for future research to closely examine how rising powers frame their security policy portfolios and utilise various forms of institutions. While we discuss development–security linkages in BRICS, future studies should empirically examine spillovers among various cooperation avenues both within and across rising power groups to better understand the politics of alliance formation. We also identified relatively large confidence intervals and some statistically nonsignificant findings due to the limited number of observations in some groups (eg studies of Brazil–India relations). Future studies can increase the number of observations by developing new indicators of local understandings of alliances and drawing on more data from books, official public remarks, newspapers and blogs.

Finally, since this study shows that the main arena for contemporary power competition from Brazil’s perspective lies in economic issues and reforming global governance more broadly, the primary challenge for development–security alliances is securing policy space in global governance. Whether securing this abstract policy space can be informed by studies that have predominantly focussed on the role of allies in securing and mutually defending physical spaces is an exciting area for future research.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the editor, the two anonymous reviewers, Kelly Sims Gallagher, John M. Owen, Francis O’Donnell, Emily Kennelly, Maisa M. Ferreira, Arthur S. Montandon, Zihao Liu, Lisa May, Eleanor Hume, Christopher C. Shim and the attendees of the University of British Columbia 2020 IR Colloquium for their input on prior drafts.

Disclosure statement

There are no competing interests to declare that may affect the research described in this article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Zhen Han

Zhen Han is Assistant Professor at the Government Department of Sacred Heart University. He was Lecturer in the Political Science Department at the University of British Columbia and previously a Postdoctoral Research Scholar in the Center for International Environment and Resource Policy at The Fletcher School of Tufts University, where research for this paper was conducted. He has also served as a Research Fellow in the Canadian Centre of International Peace and Security Studies. His research focusses on rising powers, China and economic interdependence. He has published on these topics in journals including Asian Security, Chinese Journal of International Politics and World Economy and Politics.

Mihaela Papa

Mihaela Papa is Co-Investigator on the Rising Power Alliances project at The Fletcher School at Tufts University, where she serves as Adjunct Assistant Professor in sustainable development and global governance. She has published on BRICS, sustainable development diplomacy and coalitional behaviour in global governance in the Chinese Journal of International Politics, International Affairs, Global Environmental Change and many other journals. Her recent research examined various scenarios for BRICS evolution considering India–China conflict (special section of Global Policy, 2021) and Can BRICS De-Dollarize the Global Financial System? (Cambridge University Press Elements, 2022). She is now analysing the BRICS–US relationship and its evolution in the context of contemporary security threats.

Notes

1 Many Brazilian foreign treaties contain some security components, but alliance data sets would not qualify them as military alliances (Leeds et al. Citation2002).

2 Ranking is based on the Qualis, the most-used academic journal ranking system in Brazil, version 2013–2016. The Qualis is managed by the Coordenadoria de Aperfeoçoamento de Pessoal de Nivel Superior (CAPES), which is under the administration of the Brazilian Ministry of Education.

3 Such articles include, for example, Brazil’s attitudes towards the Non-proliferation Treaty; national defence policies; UNSC; the South American Defense Council; arms trade and disarmament negotiations.

4 Such articles include, for example, South–South cooperation; globalisation; trade negotiation and disputes; regional trade agreements; economic diplomacy; and development cooperation.

5 Some articles discuss both economic cooperation and global governance reform.

6 The five regions (ranked from high to low) are: (1) South America, (2) US and Canada, (3) European Union, (4) Russia, China, India and South Africa, (5) Africa, Israel and Eastern Europe.

7 The source for this whole section is the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI 2021).

Bibliography

- Abdenur, A. E. 2016. “Rising Powers and International Security: The BRICS and the Syrian Conflict.” Rising Powers Quarterly 1 (1): 109–133. https://risingpowersproject.com/files/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/vol1.1.adriana-erthal-abdenur.pdf

- Ambrosio, T. 2005. Challenging America’s Global Preeminence: Russia’s Quest for Multipolarity. Burlington, VT: Ashgate. doi:https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315260686.

- Amorim, C. 2010. “Brazilian Foreign Policy under President Lula (2003-2010): An Overview.” Revista Brasileira de Política Internacional 53 (spe): 214–240. doi:https://doi.org/10.1590/S0034-73292010000300013.

- Becard, D. S. R. 2013. “Parcerias Estratégicas Nas Relações Internacionais: Uma Análise Conceitual.” In Parcerias Estratégicas Do Brasil: Os Significados e as Experiências Tradicionais, edited by A. C. Lessa and H. A. De Oliveira, 37–65. Belo Horizonte, MG: Fino Traco.

- Bragatti, M. C. 2019. “Diez Años Del Consejo de Defensa Sudamericano: Arquitectura de Seguridad Internacional Regional [Ten Years of the South American Defense Council: Regional International Security Architecture].” Geopolítica(s). Revista de estudios sobre espacio y poder 10 (1): 69–86. doi:https://doi.org/10.5209/GEOP.59777.

- BRIC. 2009. “BRIC Leaders Joint Statement, 2009.” http://www.brics.utoronto.ca/docs/090616-leaders.html

- BRICS. 2017. “BRICS Leaders Xiamen Declaration.” Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India. September 4. https://mea.gov.in/bilateral-documents.htm?dtl/28912/BRICS+Leaders+Xiamen+Declaration+Xiamen+China+September+04+2017

- BRICS. 2020. “BRICS Counter-Terrorism Strategy.” Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India. November 17. https://www.mea.gov.in/bilateral-documents.htm?dtl/33204/BRICS_CounterTerrorism_Strategy

- BRICS. 2021. “BRICS INDIA 2021 | Ministry of External Affairs.”brics2021.gov.in/about-brics

- Brosig, M. 2019. The Role of BRICS in Large-Scale Armed Conflict: Building a Multi-Polar World Order. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-18537-4.

- Burges, S. 2018. “UNASUR’s Dangerous Decline: The Risks of a Growing Left-Right Split in South America.” Americas Quarterly (blog). https://www.americasquarterly.org/article/unasurs-dangerous-decline-the-risks-of-a-growing-left-right-split-in-south-america/

- Buzan, B, and O. Wæver. 2003. Regions and Powers: The Structure of International Security. New York: Oxford University Press. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511491252.

- Cason, J. W, and T. J. Power. 2009. “Presidentialization, Pluralization, and the Rollback of Itamaraty: Explaining Change in Brazilian Foreign Policy Making in the Cardoso-Lula Era.” International Political Science Review 30 (2): 117–140. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0192512109102432.

- Chidley, C. 2014. “Towards a Framework of Alignment in International Relations.” Politikon 41 (1): 141–157. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02589346.2014.885682.

- Cooper, A. F. R. A. Higgott, and K. R. Nossal. 1993. Relocating Middle Powers: Australia and Canada in a Changing World Order. Vancouver: UBC Press. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/40107229.

- Dall’Agnol, A. C., B. P. Zabolotsky, and F. Mielniczuk. 2019. “The Return of the Bear? Russian Military Engagement in Latin America: The Case of Brazil.” Military Review 99 (March-April): 128–139.

- Farias, R. d. S. 2013. “Parcerias Estratégicas: Marco Conceitual.” In Parcerias Estratégicas Do Brasil, edited by A. C. Lessa and H. A. de Oliveira. Coleção Relações Internacionais. Belo Horizonte: Fino Traço Editora.

- Flemes, D. 2007. “Emerging Middle Powers’ Soft Balancing Strategy: State and Perspectives of the IBSA Dialogue Forum.” SSRN Scholarly Paper ID 1007692. Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network. doi:https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1007692.

- Flemes, D, and T. Wojczewski. 2010. “Contested Leadership in International Relations: Power Politics in South America, South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa.” SSRN Scholarly Paper ID 1547773. Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network. doi:https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1547773.

- France 24. 2019. “Brazil Calls on BRICS to Heed ‘Cries’ of Venezuelans.” News, July 26. https://www.france24.com/en/20190726-brazil-calls-brics-heed-cries-venezuelans

- Garwood-Gowers, A. 2016. “China’s ‘Responsible Protection’ Concept: Reinterpreting the Responsibility to Protect (R2P) and Military Intervention for Humanitarian Purposes.” Asian Journal of International Law 6 (1): 89–118. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S2044251314000368.

- Giesteira, F. 2021. “BRICS Academic Dialogue on International Security.” Presented at the Observer Research Foundation, June 18. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TvXUIPC-wkc&ab_channel=ORF

- Henke, M. E. 2019. Constructing Allied Cooperation: Diplomacy, Payments, and Power in Multilateral Military Coalitions. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. doi:https://doi.org/10.1515/9781501739705.

- Hindustan Times. 2020a. “India, Brazil Decide to Deepen Anti-Terror Cooperation.” January 25. https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/india-brazil-decide-to-deepen-anti-terror-cooperation/story-LMDWU5sWTLw7YKE75DEKDO.html

- Hindustan Times. 2020b. “India-Brazil-South Africa (IBSA) Calls for Speedy Global Efforts to Reform UN Security Council.” September 16 https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/india-brazil-south-africa-ibsa-calls-for-speedy-global-efforts-to-reform-un-security-council/story-Zh5NsQcUHeQ4Rh66Dv5AaL.html

- Hurrell, A. 2008. “Lula’s Brazil: A Rising Power, but Going Where?” Current History 107 (706): 51–57. doi:https://doi.org/10.1525/curh.2008.107.706.51.

- IMF. 2021. “IMF Fifteenth General Review of Quotas Additional Considerations and Data Updates.” https://www.imf.org/-/media/Files/Publications/PP/2021/English/PPEA2021010.ashx

- Indian Ministry of External Affairs (Indian MEA). 2004. “India-Brazil-South Africa (IBSA) Dialogue Forum Trilateral Commission Meeting, New Delhi Agenda for Cooperation and Plan of Action.” March 5. https://www.mea.gov.in/Speeches-Statements.htm?dtl/3168/IndiaBrazilSouth+Africa+IBSA+ Dialogue+Forum+Trilateral+Commission+Meeting+New+Delhi+Agenda+for+ Cooperation+and+Plan+of+Action

- Indian Navy. 2019. “Exercise IBSAMAR-V between India, Brazil and South Africa.” https://www.indiannavy.nic.in/content/exercise-ibsamar-v-between-india-brazil-and-south-africa

- Jayaswal, R., and R. Laskar. 2020. “India Favours Bilateral Free Trade Agreements over China-Led RCEP.” Hindustan Times, November 16. https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/india-favours-bilateral-free-trade-agreements-over-china-led-rcep/story-fpBmI5hxfIxZLubDLqsznL.html

- Jordaan, E. 2003. “The Concept of a Middle Power in International Relations: Distinguishing between Emerging and Traditional Middle Powers.” Politikon 30 (1): 165–181. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0258934032000147282.

- Korolev, A. 2019. “On the Verge of an Alliance: Contemporary China-Russia Military Cooperation.” Asian Security 15 (3): 233–252. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14799855.2018.1463991.

- Korolev, A. 2019. “How Closely Aligned Are China and Russia? Measuring Strategic Cooperation in IR.” International Politics 57 (5): 760–789. doi:https://doi.org/10.1057/s41311-019-00178-8.

- Leeds, B., J. Ritter, A. Mitchell, and A. Long. 2002. “Alliance Treaty Obligations and Provisions, 1815-1944.” International Interactions 28 (3): 237–260. http://www.atopdata.org/data.html doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03050620213653.

- Lopes, D. B. G. Casarões, and C. F. Gama. 2020. “A Tragedy of Middle Power Politics: Traps in Brazil’s Quest for Institutional Revisionism.” In Status and the Rise of Brazil: Global Ambitions, Humanitarian Engagement and International Challenges, edited by P. Esteves, M. G. Jumbert, and B. de Carvalho, 51–69. Cham: Springer International Publishing. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-21660-3_4.

- Mahon, T. 2015. “Chinese Seek Brazilian Assistance with Jungle Training.” Defense News, August 9. https://www.defensenews.com/training-sim/2015/08/09/chinese-seek-brazilian-assistance-with-jungle-training/

- Marcondes, D., and P. H. B. Barbosa. 2018. “Brazil-China Defense Cooperation: A Strategic Partnership in the Making.” Journal of Latin American Geography 17 (2): 140–166. doi:https://doi.org/10.1353/lag.2018.0025.

- Medvedev, D. 2008. “Transcript of the Meeting with the Participants in the International Club Valdai.” President of Russia, September 12. http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/transcripts/1383

- Mijares, Víctor M. 2018. “Performance of the South American Defense Council under Autonomy Pressures.” Latin American Policy 9 (2): 258–281. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/lamp.12146.

- Ministry of Defense of Brazil (MoD Brazil). 2008. “National Strategy of Defense: Peace and Security for Brazil.” https://css.ethz.ch/en/services/digital-library/publications/publication.html/154868

- Ministry of Defense of Brazil (MoD Brazil). 2012. “Política Nacional de Defesa.” https://www.defesa.gov.br/estado-e-defesa/politica-nacional-de-defesa

- Ministry of Defense of Brazil (MoD Brazil). 2017. “Cenários de Defesa 2020-2039.” https://www.defesa.gov.br/arquivos/ensino_e_pesquisa/defesa_academia/cadn/palestra_cadn_xi/xiv_cadn/cenarios_de_defesa_2039.pdf

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MoFA Brazil). 2019. “Theme and Priorities.” BRICS Brasil 2019. http://brics2019.itamaraty.gov.br/en/2019-brazilian-presidency/theme-and-priorities#

- Nau, H. R. 2008. “Scholarship and Policy Making: Who Speaks Truth to Whom?” In The Oxford Handbook of International Relations, edited by C. Reus-Smit and D. Snidal, 1st ed., 636–651. New York: Oxford University Press. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199219322.003.0036.

- Nolte, D. 2010. “How to Compare Regional Powers: Analytical Concepts and Research Topics.” Review of International Studies 36 (04): 881–901. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S026021051000135X.

- Oliveira, M. F. d. 2005. “Alianças e Coalizões Internacionais Do Governo Lula: O Ibas e o G-20.” Revista Brasileira de Política Internacional 48 (2): 55–69. doi:https://doi.org/10.1590/S0034-73292005000200003.

- Ozkan, M. 2010. “Turkey–Brazil Involvement in Iranian Nuclear Issue: What Is the Big Deal?” Strategic Analysis 35 (1): 26–30. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09700161.2011.530980.

- Panova, V. 2018. “The BRICS Security Agenda and Prospects for the BRICS Ufa Summit.” In BRICS and Global Governance, edited by M. Larionova and J. J. Kirton, 119–139. New York: Routledge. doi:https://doi.org/10.17323/1996-7845-2015-02-119.

- Papa, M., and R. Verma. 2021. “Scenarios for BRICS Evolution in Light of the India-China Conflict.” In R. Verma and M. Papa, eds., Special Section: India-China Conflict and BRICS: Business as Usual?, Global Policy 12 (4): 539–544. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1758-5899.13010.

- Pape, R. A. 2005. “Soft Balancing against the United States.” International Security 30 (1): 7–45. doi:https://doi.org/10.1162/0162288054894607.

- Paraguassu, L, and A. Alper. 2019. “Bolsonaro Touts ‘Changed’, US-Friendly Brazil to Washington.” Reuters, March 19. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-brazil-idUSKCN1QZ1T0

- Poast, P. 2012. “Does Issue Linkage Work? Evidence from European Alliance Negotiations, 1860 to 1945.” International Organization 66 (2): 277–310. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0738894213484030.

- Pontes, M. R. D. 2016. “Ideas, Beliefs, Strategic Culture, and Foreign Policy: Understanding Brazil’s Geopolitical Thought.” PhD diss., University of Central Florida. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/5105

- Roche, E. 2019. “India, Other BRICS Members to Strengthen Cooperation in Digital Economy: Modi.” Livemint, November 12. https://www.livemint.com/news/india/brics-summit-to-focus-on-strengthening-counter-terror-cooperation-pm-modi-11573561454271.html

- Rooyen, F. C. v. 2017. “The India-Brazil-South Africa (IBSA) Collective and the Socio-Political Construction of Security.” PhD diss., University of the Free State Bloemfontein.

- Røren, P, and P. Beaumont. 2019. “Grading Greatness: Evaluating the Status Performance of the BRICS.” Third World Quarterly 40 (3): 429–450. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2018.1535892.

- Salzman, R. S. 2019. Russia, BRICS, and the Disruption of Global Order. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvcj2sb2.

- Samuels, B. 2019. “Trump Officially Designates Brazil a Non-NATO Ally.” The Hill. July 31, 2019. https://thehill.com/homenews/administration/455642-trump-officially-designates-brazil-non-nato-ally

- Selcher, W. A. 2018. Brazil in the International System: The Rise of a Middle Power. New York: Routledge. doi:https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429052101.

- Schirm, S. A. 2010. “Leaders in Need of Followers: Emerging Powers in Global Governance.” European Journal of International Relations 16 (2): 197–221. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066109342922.

- Schweller, R. L. 1994. “Bandwagoning for Profit: Bringing the Revisionist State Back In.” International Security 19 (1): 72–107. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/2539149.

- Sidiropoulos, E. 2013. “IBSA: Avoiding Being BRICked Up.” Strategic Analysis 37 (3): 285–290. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09700161.2013.782628.

- Silva, da A. L. R. 2015. “Geometria Variável e Parcerias Estratégicas: A Diplomacia Multidimensional Do Governo Lula (2003-2010).” Contexto Internacional 37 (1): 143–184. doi:https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-85292015000100005.

- SIPRI (Stockholm International Peace Research Institute). 2021. “SIPRI Arms Transfers Database.” https://www.sipri.org/databases/armstransfers

- Snyder, G. H. 1997. Alliance Politics. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/2658079.

- Sotero, P., and L. E. Armijo. 2007. “Brazil: To Be or Not to Be a BRIC?” Asian Perspective 31 (4): 43–70. doi:https://doi.org/10.5195/jwsr.2016.628.

- South African Government. 2010. “Multi-National Exercise between Indian, Brazil and South African Navies: Exercise IBSAMAR.” September 7. https://www.gov.za/multi-national-exercise-between-indian-brazil-and-south-african-navies-exercise-ibsamar

- StrategyPage. 2013. “Naval Air: Brazil Shows China How It Is Done.” February 1. https://www.strategypage.com/htmw/htnavai/articles/20130201.aspx

- Stuenkel, O. 2014. India-Brazil-South Africa Dialogue Forum (IBSA): The Rise of the Global South. New York, NY: Routledge. doi:https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315765051.

- Tyushka, A. L. Czechowska, A. Domachowska, K. Gawron-Tabor, and J. Piechowiak-Lamparska. 2019. “States, International Organizations and Strategic Partnerships: Theorizing an ‘Ideal Model.’” In States, International Organizations and Strategic Partnerships, edited by L. Czechowska, A. Tyushka, A. B. Domachowska, K. Gawron-Tabor, and J. Piechowiak-Lamparska, 44–80. Northhampton, MA: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited. doi:https://doi.org/10.4337/9781788972284.

- US Department of Defense. 2018. “Summary of the 2018 National Defense Strategy of The United States of America.” https://dod.defense.gov/Portals/1/Documents/pubs/2018-National-Defense-Strategy-Summary.pdf

- Vaz, A. C. 1999. “Parcerias Estratégicas No Contexto Da Política Exterior Brasileira: Implicações Para o Mercosul.” Revista Brasileira de Política Internacional 42 (2): 52–80. doi:https://doi.org/10.1590/S0034-73291999000200004.

- Viotti, M. L. R. 2011. “Integrated and Coordinated Implementation of and Follow-Up to the Outcomes of the Major United Nations Conferences and Summits in the Economic, Social and Related Fields-Follow-up to the Outcome of the Millennium Summit.” November 9. https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/716109?ln=en

- Visentini, P. G. F, and da A. L. R. Silva. 2010. “Brazil and the Economic, Political, and Environmental Multilateralism: The Lula Years (2003-2010).” Revista Brasileira de Política Internacional 53 (SPE): 54–72. doi:https://doi.org/10.1590/S0034-73292010000300004.

- Vitelli, M. G. 2017. “The South American Defense Council: The Building of a Community of Practice for Regional Defense.” Revista Brasileira de Política Internacional 60 (2): 2–19. doi:https://doi.org/10.1590/0034-7329201700202.

- Weiffen, B., L. Wehner, and D. Nolte. 2013. “Overlapping Regional Security Institutions in South America: The Case of OAS and UNASUR.” International Area Studies Review 16 (4): 370–389. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/2233865913503466.

- Wilkins, T. S. 2012. “‘Alignment’, Not ‘Alliance’ – The Shifting Paradigm of International Security Cooperation: Toward a Conceptual Taxonomy of Alignment.” Review of International Studies 38 (1): 53–76. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0260210511000209.

- Xi, J. 2019. “Zai Jinzhuanguojia Lindaoren Baxiliya Huiwu Gongkaihuishi Shang de Jianghua [The Speech at the BRICS leaders’ Summit in Brasilia].” Xinhua news, in Chinese. http://www.xinhuanet.com/politics/leaders/2019-11/15/c_1125233767.htm