Abstract

In the last two decades, significant advances have characterised the study of hybrid political regimes. Yet, when distinguishing democratic from non-democratic varieties, this field has apparently been affected by the tendency to largely focus on the role of incumbents and the state. Drawing on the Colombian, El Salvadorean and Guatemalan examples, I argue that, because of this bias, a category of countries sharing distinctively non-democratic features has been incorrectly considered democratic, thus affecting the recognition of forms of democracy and non-democracy. In these countries, actors other than the state and the government have blatantly violated the fairness of elections through well-known practices generally considered problems of low democratic quality, such as vote-buying, political violence, and illegal campaign financing. I maintain that, when associated with certain conditions, such problems are in fact symptoms of a non-democratic regime. To describe these unrecognised non-democracies, I propose the concept of non-state electoral autocracy.

Introduction

Hybrid regimes have received increasing attention in the study of political regimes. While two decades ago Carothers (Citation2002) famously noted the existence of a ‘grey zone’ of countries combining democratic institutions and flaws, over time seminal contributions (eg Levitsky and Way Citation2010; Merkel Citation2004; Schedler Citation2006) have shed light on the crucial role that such regimes play in the post-Cold War era. Although the definition of the concept of hybrid regimes has represented a significant source of disagreement (see eg Cassani Citation2014; Gilbert and Mohseni Citation2011; Mufti Citation2018; Wigell Citation2008), following their appearance, political regimes have been increasingly classified according to taxonomies including also intermediate categories for both non-liberal democracies and hybrid non-democratic regimes (Lührmann, Tannenberg, and Lindberg Citation2018, 62; see also eg Howard and Roessler Citation2006; Cassani and Tomini Citation2020). Within these efforts, the freedom and fairness of multi-party elections have persisted as key factors to distinguish non-liberal or problematic democracies from competitive non-democratic regimes and, therefore, as necessary conditions for democracy (see Levitsky and Way Citation2010, 5–7; Schedler Citation2006, 3; Howard and Roessler Citation2006, 367–368; Cassani and Tomini Citation2020, 277–278; Lührmann, Tannenberg, and Lindberg Citation2018, 63–64).

In spite of these advances, drawing on the Colombian, El Salvadorean and Guatemalan examples, I argue that the distinction between problematic democracies and competitive non-democratic regimes – that is, non-democratic regimes with some form of competitive elections (eg competitive authoritarianism, electoral authoritarianism)Footnote1 – has been affected by the scholarly tendency to assess the crucial criterion of the fairness of elections through an almost exclusive or primary focus on the state and incumbents. As also noted by Schedler (Citation2014, 10) in his analysis of criminal violence in Mexico, by primarily focusing on the behaviour of incumbents, scholars have often overlooked or not sufficiently considered distortions by alternative actors. Particularly in the assessment of political regimes, this is problematic given that, in light of the centrality of free and fair elections, what should matter is whether and how elections are distorted and made unfair, not who distorts them. Resolving and shedding light on this possible bias is crucial given the importance of distinguishing democracies, albeit problematic, from non-democratic regimes. Although posing the question of the democratic rather than undemocratic character of a country ridden by non-state criminal violence such as Mexico, Schedler (Citation2014, 12) apparently leaned towards its inclusion in the category of democracies. While my argument is not limited to criminal violence, I maintain that because of the bias described above, a typology of hybrid regimes sharing distinctively non-democratic features has been commonly and, I believe incorrectly, included in the democratic camp. These countries present distinctive features that merit more attention in the study of non-democratic regimes, and I suggest that their recognition is important for both theoretical and practical reasons. A clear definition of the phenomenon is therefore needed.

Although multi-party elections are regularly celebrated there, in these countries actors other than the government and the state have systematically and severely distorted national electoral competition to their benefit, thus replicating defining key features of the executives described by Levitsky and Way (Citation2010) and Schedler (Citation2006) in competitive and electoral authoritarianism. Examples include the creation by political parties, clans or mixed networks of a systematic electoral advantage through a number of well-known practices such as illegal campaign financing, electoral violence and/or vote-buying. The reasons behind the arguably incorrect democratic categorisation of these cases may be associated with the fact that these countries are different from the typical hybrid non-democratic typologies discussed by the literature (eg electoral and competitive authoritarianism) while at the same time sharing some important features with many malfunctioning or low-quality democracies. Unlike competitive and electoral authoritarianism, where the distortion of the electoral competition originates from rulers and the state (Levitsky and Way Citation2010, 5; Schedler Citation2006, 3), in these countries systematic distortions originate from other actors, in a context where institutional checks on executive power are not necessarily compromised, thus not fitting the commonly accepted model of competitive non-democratic regime. Moreover, the distortions originating from actors other than the government tend to be less visible, particularly their systematic character, thus making their identification more difficult. Finally, when not considered in combination with other crucial features (see next section), the typical problems affecting these countries (eg vote-buying, illegal campaign financing, political violence) may be mistaken as signs of low democratic quality rather than the symptoms of a competitive non-democratic regime.

In short, this study questions the tendency to recognise non-democracies only in the presence of a repressive or manipulative government and, in parallel, the propensity to grant democratic labels in the presence of blatant, deliberate and systematic, although not governmental, distortions of electoral competition. By doing so, this paper sheds light on a possible, problematic bias in the field of political regimes. The goal is not simply to contribute to the correct interpretation of cases sharing similar characteristics. Similarly, this paper does not (unfairly) criticise projects classifying a large number of cases for the arguably questionable evaluation of some countries. Rather, the goal is to provide a number of insights and theoretical contributions that may complement the debate on political regimes. First, this study problematises how scholars often classify political regimes and draw the boundaries of democracy. Second, it highlights the characteristics and the particularly dangerous elements of an overlooked variant of competitive non-democratic regime. Moreover, it provides insights on how to tailor the promotion of democracy. Finally, by showing that countries can autocratise because of the initiative of actors other than the state, it complements the burgeoning literature on autocratisation processes.

To illustrate my argument, I draw on an analysis of the Colombian, Guatemalan and El Salvadorean cases. As suggested by Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser (Citation2013, 148, 155) drawing on Gerring in their analysis of populism’s varieties, the ‘prototypical’ nature of certain examples can contribute to the elaboration and a first assessment of an argument.

An overlooked variant of competitive non-democratic regime?

New concepts and regime types

The refinement or elaboration of new concepts to better understand and describe reality is a crucial and needed exercise, particularly in the study of political regimes. Since Sartori’s (Citation1970) classic recognition of the inadequacy of existing concepts to describe an expanding and increasingly diverse political world, the literature has produced significant conceptual advances thanks to key contributions such as Collier and Mahon (Citation1993), Gerring (Citation1999) and Collier and Levitsky (Citation1997). This last study was especially important in showing how scholars responded (sometimes unconsciously) to the appearance of new political regimes in an apparently democratising world, particularly hybrid regimes lacking certain democratic elements. Collier and Levitsky (Citation1997) noted that unlike the problem outlined by Sartori (Citation1970), scholars did try to avoid the ‘conceptual stretching’ of democracy, including through the adoption of new concepts. Their caveat to possibly consider these new cases as authoritarian rather than democratic subtypes was also important in the evolution of the political regimes field, particularly in pushing scholars to consider new non-democratic hybrid regimes. Importantly, aware of the risk of confusion associated with the appearance of new concepts, Collier and Levitsky (Citation1997) called for parsimony and, in essence, an analysis of both the costs and the benefits associated with conceptual innovation, a recommendation followed, for example, by Levitsky and Way (Citation2010, 13–16) in their seminal presentation of the concept of competitive authoritarianism. According to Levitsky and Way (Citation2010, 14), the novelty of the phenomenon and the limitations of alternative categories justified the elaboration of their new concept. Similarly, according to O’Donnell, creating a new concept responds to the need to define unrecognised, although not necessarily new, phenomena and specificities (Munck and Snyder Citation2007, 298). Crucial in the elaboration of a new concept, O’Donnell argued, is its role in the formulation of new research questions (Munck and Snyder Citation2007, 298).

The recognition of a variant of non-democracy originating from the electoral distortions of actors other than the government and the state responds to the important points raised by these key contributions. First, it considers an overlooked phenomenon, as demonstrated by the generally democratic classification of these regimes and by the fact that important typologies seem constructed on assumptions excluding their existence (see below). This last problem is significant given that it may lead to what Gerring (Citation1999, 383) defines as a ‘homeless entity’. Second, as discussed in the final part of this paper, the recognition of these non-democracies captures important features that may lead to new research questions and more adequate policies for the promotion of democracy. More generally, it is important for a more appropriate depiction of certain contexts that might not be otherwise properly understood. Finally, in light of the contribution to new possible research questions, to the refinement of existing taxonomies, and to the debate on the boundaries of democracy, the concept proposed in this paper also responds to what Gerring (Citation1999) indicates are other important features of a ‘good concept’, namely ‘theoretical utility’ as well as ‘field utility’. More specifically, introducing a concept describing a regime that is non-democratic due to non-state electoral distortions is important, first, because the nature of elections is central to distinguish democracies from non-democracies. And, combined with this, because the tendency of the literature to overlook non-state electoral distortions in regime classifications – and therefore arguably to misclassify certain non-democracies as democracies – results precisely from the lack of a concept of non-democracy that takes these distortions into account. Indeed, as noted below, electoral autocracies are commonly equated with competitive authoritarianism, where distortions originate from the state.

I call the new non-democracies considered in this paper non-state electoral autocracies. Although those who benefit from non-state electoral distortions in these regimes may be in government (eg incumbent parties), they do not use their position in the executive to systematically distort elections through the state such as in competitive or electoral authoritarianism. In other words, even in this case, the government as an institution does not distort elections. To build the concept, I follow in particular Goertz’s (Citation2006, Citation2020) key guidelines. Goertz (Citation2006, Citation2020) observes that concepts are often ‘multilevel’ and ‘multidimensional’ and can present different structures. Therefore, according to Goertz (Citation2006, Citation2020), concept builders should distinguish between a ‘secondary level’ with different dimensions and an ‘indicator/data’Footnote2 level, clearly explain how they combine dimensions or indicators at each level (including through the logical operators AND and OR), and always indicate sufficiency criteria. Moreover, according to Goertz (Citation2006, Citation2020), it is important to conceptualise both the positive and negative pole of the concept as well as the resulting continuum and ‘grey zone’.

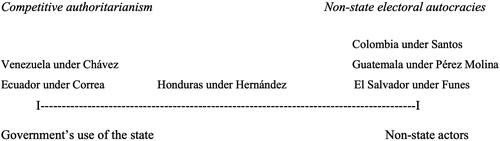

Regarding the definition of the conceptual structure, in line with Goertz’s (Citation2006, Citation2020) discussion of the ‘necessary and sufficient condition structure’, at the ‘secondary level’ of the concept I consider five conditions separately necessary and together sufficient to define a political regime as a non-state electoral autocracy. A non-state electoral autocracy is a political regime where (A) national elected officials exert effective power AND (B) national-level elections are inclusive AND (C) competitive AND (D) unfair AND (E) electoral unfairness results from the action of actors other than the government or the state. Once having outlined this structure of the concept, and considering that, following taxonomies à la Lührmann, Tannenberg, and Lindberg (Citation2018), competitive AND unfair elections distinguish electoral autocracies from both ‘closed’ autocracies and democracies, it should be evident that a political regime including the first four dimensions (A–D) is an electoral autocracy and that the proposed new concept of non-state electoral autocracy (including all five dimensions A–E) is a subtype of electoral autocracy. Although the literature has tended to consider the category of electoral autocracies as coincident with that of competitive authoritarian regimes, these are in fact only another subtype of electoral autocracy where, unlike non-state electoral autocracies, the actor responsible for the unfairness of elections is the government through the use of the state. Responding to the emphasis that Goertz (Citation2006, Citation2020) lays on the conceptualisation of the positive and negative poles of a concept and on the resulting continuum, within the category of electoral autocracies a competitive authoritarian regime can then be viewed as the negative pole of a non-state electoral autocracy. The continuum between these two poles (see for some illustrative, non-exhaustive cases) is populated by electoral autocracies where electoral unfairness results from both non-state actions and the government’s use of the state – that is, regimes where the nature of the systematic distortion of electoral fairness is neither completely societal nor completely governmental. Honduras under Hernández, where elections are arguably systematically distorted both by the government through state institutions and by the illegal actions of criminal organisations, is a possible example. It should be noted that the elected officials’ full power of government (dimension A) excludes systematic and severe (see below) state distortions not approved by the government.

Figure 1. Origin of electoral distortions in electoral autocracies.

Note: In countries on/close to the two extremes, electoral distortions originate exclusively/largely from the government’s use of the state or non-state actors. Between the two poles, distortions originate from both the government and non-state actors.

With respect to the indicator level of the concept and the specification of the second-level dimensions, national-level elections are unfair (dimension D) when, following defining features of incumbents’ distortive actions in competitive or electoral authoritarianism (Levitsky and Way Citation2010; Schedler Citation2006), one or more actors, irrespective of their nature, systematically and severely distort them to their advantage. This can occur in different ways, for example through systematic and extensive electoral violence, or vote-buying, or severe illegal campaign financing, or any of the typical manipulations arranged by governments through the state in competitive or electoral authoritarian regimes, including, among the practices described by Levitsky and Way (Citation2010, 5–13) and Schedler (Citation2006, 3), biased access to resources, the executive’s harassment of the opposition, or governmental electoral fraud. The use of the logical OR means that any of these systematic and extensive practices, regardless of its initiator, is sufficient to characterise an election as unfair. As noted by Goertz (Citation2020, 47), unlike second-level dimensions, at the ‘data-indicator level’ the list of indicators does not need to be complete.

Regarding the last dimension (E) concerning the non-state nature of the actors systematically and severely distorting elections, it refers to a scenario in which such distortions do not originate from the government’s use of the state and can come from illegal (eg criminal organisations, or insurgents, or clans) or legal actors such as political parties resorting to systematic vote-buying (see next section). By definition, because the electoral distortions of these actors do not take place through state institutions, they do not result from the manipulation of the law and occur exclusively through illicit practices (see below). While the inclusiveness of elections (dimension B) refers to right of the whole adult population to participate, elections are competitive (dimension C) in the presence of multi-party competition.

An overlooked phenomenon?

Cases such as Colombia, El Salvador and Guatemala have been long affected by different problems including political violence, illegal campaign financing, vote-buying and organised crime. Although the severity of these problems has been often recognised, in the last decade both qualitative and quantitative evaluations have generally classified these countries as democratic or imperfectly democratic (eg Mainwaring and Pérez-Liñán Citation2015; Regimes of the World index in Coppedge et al. Citation2020a;Footnote3 Marshall and Gurr Citation2020a;Footnote4 see also Levitsky Citation2018).Footnote5

In these countries, the incumbent does not systematically distort elections through state institutions and, apparently, the problems mentioned above are typically considered compatible with democracy. However, these problems can and do distort electoral competition, a distortion that is sometimes even more intense than in competitive or electoral authoritarian regimes. In itself, the diffusion of these problems, however worrisome, would not be sufficient to categorise a political regime as non-democratic: after all, a number of other problems (eg high socio-economic inequality) have often undermined the functioning of elections, without being considered sufficient to make the electoral competition unfair. Yet I argue that, when combined with certain conditions, the distortions resulting from these problems do qualify a political regime as non-democratic. Borrowing what Schedler (Citation2006) and Levitsky and Way (Citation2010) view as defining features of rulers’ manipulations in other competitive non-democratic regimes, such as electoral and competitive authoritarianism, this is the case when such distortions are severe and result from systematic efforts aimed at the creation of an electoral advantage. Although not originating from the incumbent or the state, these efforts are not mere dysfunctions of the political system but, rather, the realisation of the systematic attempt of powerful actors to manipulate democracy. This, I argue, is a relatively common and not sufficiently considered phenomenon in countries typically defined as low-quality or imperfect democracies such as Colombia, El Salvador and Guatemala.

These are regimes where inclusive, competitive multi-party elections are regularly celebrated, national elected officials exert effective power, and, as noted above, the national incumbent does not systematically engage in the distortion of elections through the state. However, organised actors other than the government or the state do systematically and severely distort electoral contests for the national executive or the national legislature through various illegal practices. Because of these distortions, these actors gain a systematic electoral advantage, thus making the electoral competition unfair.

With respect to the nature of the actors responsible for the violation of the freedom and fairness of elections, these are organisations that, although sometimes collaborating with corrupt segments of the state (see eg Trejo and Ley (Citation2020) on criminal organisations), are not part of it. Their ability to distort elections does not derive from control of the state machinery but from their ability to resort to illegal practices, be they violent or not. These actors may include, but are not limited to, legal organisations such as political parties involved in systematic vote-buying, illegal organisations resorting to violence such as insurgents, clans and criminal organisations, or coalitions of these actors. While their origin may be domestic or foreign, different types of non-state actors may play a more or less relevant role depending on the context considered. Even though illegal organisations have often played a crucial role in the distortion of electoral competition, such distortion is not necessarily associated with their presence. In some instances, such as in the case of vote-buying, legal political actors have systematically distorted electoral competition without taking advantage of criminal organisations primarily devoted to illicit activities. In other words, although sometimes accompanied by different objectives, the goal of these distortions is essentially political and aimed at the attainment of political power.

With respect to how elections are distorted, like incumbents’ distortive practices in competitive or electoral authoritarian regimes (Levitsky and Way Citation2010; Schedler Citation2006, respectively), non-state actors’ use of illegal practices to skew elections is systematic and severe. This means that the distortion of elections does not merely result from the occasional initiatives of multiple actors that sum up to create a diffused problem. Rather, these practices are coherently used by certain actors on a systematic basis within strategies aimed at producing a consistent electoral advantage. Similarly, the distortion of elections is not a byproduct of practices conceived and implemented for other reasons, such as in a context where insecurity resulting from non-electoral violence discourages citizens from voting. Therefore, the mere existence or diffusion of problems able to affect elections, such as violence or vote-buying, is not sufficient, in itself, to characterise a regime as non-democratic. They need to result from the systematic efforts of certain organisations to skew elections.

Regarding the nature of the practices adopted to distort elections, as noted above, they are diverse and may include vote-buying, illegal campaign financing, electoral violence or their combination. In essence, they may include any illegal practice not based on state institutions designed and conceived to distort elections. Related to the role of state institutions, the exclusive use of illicit practices marks a difference with competitive authoritarianism where, as noted by authors such as Corrales (Citation2015) in his analysis of the Venezuelan case, ‘autocratic legalism’ and the manipulation of the law represent key autocratic features. Although such illicit practices are not necessarily associated with illegal organisations such as criminal groups or insurgents, the study of these organisations has shed light on the negative impact of non-state actors on elections. In particular, recent studies focusing on criminal–political coalitions (Albarracín Citation2018), armed actors in the context of a civil war (Arjona Citation2016) and drug cartels (Trejo and Ley Citation2020) have shown how these actors have deliberately distorted elections, particularly at the local level and through coercive practices concerning both candidates and voters. Regarding criminal groups, in his study of Brazilian peripheries, Albarracín (Citation2018) notes how different types of coalitions of political and criminal actors have been able to manipulate local elections through combinations of violence and clientelism. Similarly, as explained by Trejo and Ley (Citation2020), when the needs associated with their wars made it necessary, drug cartels in Mexico started taking control of numerous municipalities, including through the violent distortion of elections. Interestingly, both Albarracín (Citation2018) and Trejo and Ley (Citation2020) observe that these strategies have been predominantly deployed at the local level, but for different reasons. While according to Albarracín (Citation2018, 561), part of the reason has to do with the increased visibility of these practices at the national level, Trejo and Ley (Citation2020, 277) tentatively explain the local nature of the cartels’ political role by the specific needs associated with drug trafficking and the unviability of a national-scale victory against the state. However, cases such as El Salvador and Guatemala show that the visibility problem highlighted by Albarracín (Citation2018) has not deterred criminal–political coalitions from successfully dominating national politics in these countries. At the same time, while plausible for the Mexican context and for these organisations, Trejo and Ley’s (Citation2020) explanation of cartels’ local perspective may be less useful for different contexts or actors, for example organisations not openly at war with the state or not primarily involved in drug trafficking. In short, while these studies have meritoriously shed light on the ability of illegal actors to influence elections, more attention should be paid to the national level, which is obviously key for the definition of the political regime.

It should also be noted that what makes these regimes non-democratic is not that national elected officials do not hold effective power but, rather, that some actors enjoy a systematic, illicit electoral advantage. To be sure, especially at the local level, in these countries, some elected officials who won fair elections run the risk of falling under the coercive control of illegal organisations. In this respect, with a specific focus on organised crime, Albarracín (Citation2018, 561) distinguishes the cooperative efforts of political and criminal organisations to distort elections from sometimes violent and hostile attempts to shape the decisions of elected officials. However, while, as noted above, existing examples seem to contradict Albarracín’s (Citation2018, 561) thesis of the limited viability of criminal–political electoral coalitions at the national level, the coercive subjugation of elected officials at this level does appear more complicated and less likely.

In short, through illicit practices commonly and, I argue, mistakenly viewed as problems of democratic quality, in these countries actors other than the government and the state have operated in different parts of the national territory through structured organisations to gain a constant and systematic electoral advantage aimed at the creation of a durable system of power. In terms of outcomes, such distortions are not limited to the local level and can influence both congressional and presidential elections and the composition of national institutions. Interestingly, although different in their non-governmental origin, when systematic, some of the practices recurrent in these countries may resemble, in terms of the type of effects and purposes, some of the governmental manipulations indicated by Schedler (Citation2006, 3) and Levitsky and Way (Citation2010, 5–13) in electoral or competitive authoritarian regimes, for instance those concerning the persecution of opponents, electoral fraud or unequal access to economic resources. For example, the illegal campaign financing originating from sources such as drug trafficking may be comparable, in terms of effects, to an incumbent’s asymmetric use of state resources. Similarly, the systematic threats or physical elimination of voters and political candidates by illegal organisations can reproduce the effects of governmental intimidation of the opposition. Finally, the results of massive vote-buying can parallel the manipulations orchestrated by the government and state authorities in the electoral arena.

In the next sections, I address the important theoretical and practical implications associated with the recognition of this phenomenon. However, before moving to the analysis of specific cases, it is important to note that this recognition may contribute to the construction of taxonomies that are better equipped to exhaustively identify existing non-democratic hybrid regimes. With respect to the latter, since their diffusion, taxonomies and scholars have responded to the appearance of hybrid regimes in different ways, including adopting a unidimensional rather than multidimensional approach and considering them as both authoritarian and democratic subtypes or as a neither authoritarian nor democratic category (Cassani Citation2014; Mufti Citation2018). A generally recognised point has been, in fact, the recognition of conceptual confusion (Cassani Citation2014; Gilbert and Mohseni Citation2011; Mufti Citation2018; Wigell Citation2008). However, despite this confusion, the field has also shown promising signs of convergence. As noted by Cassani (Citation2014, 548–550), in spite of their differences, existing approaches have all referred to hybrid regimes as a combination of certain authoritarian and democratic institutional components, including, among the latter, multi-party elections. Moreover, some agreement has converged over taxonomies distinguishing democratic from autocratic regimes on the basis of requirements including the freedom and fairness of elections, and then, within these categories, more or less democratic or autocratic subtypes in accordance with other criteria (Cassani and Tomini Citation2020; Lührmann, Tannenberg, and Lindberg Citation2018; Howard and Roessler Citation2006). Precisely, some of these influential and useful taxonomies show the importance of introducing a concept that recognises the violation of minimum democratic requirements by actors other than the government or the state. While considering free and fair elections a key factor discriminating between democratic and non-democratic regimes, taxonomies such as those proposed by Howard and Roessler (Citation2006) and Cassani and Tomini (Citation2020) seem constructed on the assumption that only the incumbent can make the elections unfair. For example, Howard and Roessler (Citation2006, 367) consider competitive authoritarianism – a regime where by definition competition is made unfair by the incumbent (Levitsky and Way Citation2010, 5) – the only possible regime between democratic regimes with free and fair elections and regimes without competitive elections. Similarly, to define the concept of electoral autocracy as the only category between closed autocracies and democratic regimes, Cassani and Tomini (Citation2020, 278–279) draw on Schedler’s work on electoral authoritarianism, a regime where manipulations and distortions are viewed by Schedler (Citation2006, 3) as the result of the action of rulers.

In the second part of the paper, first I consider the Colombian, Guatemalan and El Salvadorean cases. Then, I discuss the important theoretical and practical implications deriving from the recognition of these regimes.

Colombia

If limited to the analysis of recent executives, particularly following Uribe’s controversial presidency (2002–2010), the common assessment of Colombia as a democratic country would seem justified. Although not flawless, in the last decade Colombian incumbents have not systematically attacked constitutive elements of democracy.Footnote6 Yet the evaluation of Colombia as a democracy, however imperfect or problematic, becomes questionable once we consider aspects not related to the executive’s use of the state.

Although not in themselves a reason to question Colombia’s democratic character, today, a number of significant problems continue to affect electoral competition, including widespread vote-buying (see Transparency International Citation2019), violence and fraud (see Vargas Betancourt Citation2018). What makes some of these problems even more worrisome is that they often appear, rather than diffused dysfunctions of democracy, to be part of the systematic efforts of organised actors to skew electoral competition. Around 10 years ago, recognising the negative impact of problems such as vote-buying and political violence on the quality of elections, authors such as Botero, Hoskin, and Pachón (Citation2010) noted that they typically resulted from the initiative of illegal groups, including drug trafficking organisations and the actors involved in the conflict, particularly the guerrilla groups and the paramilitaries. Interestingly, these authors still evaluated Colombia as a democracy, albeit one with serious problems, thus confirming the tendency to consider this regime democratic even before the last decade, when existing distortions were possibly even more profound. In spite of the process leading to the 2016 peace agreement, powerful actors not necessarily associated with the conflict have continued to skew electoral competition.

First, the influence of paramilitary or related groups on both national and local elections has apparently continued to be significant. In the now well-known phenomenon called parapolítica, paramilitary groups supported the elections of numerous politicians, thus developing significant influence in different elective institutions. According to the newspaper El Tiempo (Citation2016), although the investigations for parapolítica have led to the sentencing of several governors and large segments of Congress, the groups involved in this phenomenon have often maintained their presence in the country’s democratic institutions. Ardila Arrieta (Citation2014) argues that, in both the 2010–2014 and 2014–2018 Congress, more than 30 candidates allegedly associated with the parapolítica were eventually elected. This would amount to more than 10% of Congress.

Regarding the influence of powerful networks on vote-buying, in the wake of the 2018 congressional elections, following a police raid discovering material apparently used for vote-buying, Representative and Senator-elect Aida Merlano was accused of leading a network aimed at distorting elections for multiple national and subnational elective offices. The sentence of the Supreme Court (Corte Suprema de Justicia Citation2019), eventually condemning Merlano for conspiracy and vote-buying and confirmed in large part in 2020 in the second instance (Corte Suprema de Justicia Citation2020), highlighted the sophistication and organisation of this network, including the use of QR codes, ticket windows (taquillas) and houses where voters were instructed on how to vote. Drawing on a report of the judicial police, the sentence of the Supreme Court (Corte Suprema de Justicia Citation2019, 95–97) also highlighted the alleged connection between Merlano, her network and some of the most dominant political families on the Caribbean Coast. These groups have played a notable role in national politics, including a significant presence in Congress, while the Caribbean coast was widely recognised as key in former President Santos’s re-election in 2014. In the same sentence condemning Merlano, the Supreme Court (Corte Suprema de Justicia Citation2019) requested the investigation of a number of elected officials, including the 2020-2021 president of Congress, Arturo Char.

In a recently disclosed recorded conversation, and another major scandal of Colombian politics known as ñeñepolítica, an alleged collaborator of former President Uribe can be heard talking with ‘Ñeñe’ Hernández – a now-deceased entrepreneur allegedly part of a criminal organisation – about possibly buying votes in support of President Duque on the eve of the 2018 presidential elections (see Semana Citation2020). The Supreme Court opened an investigation against former President Uribe, while a commission in the House of Representatives is currently examining the charges formulated by a member of the opposition against Duque.

A further sign of the fact that the aforementioned problems may not be merely problems of democratic quality but, rather, the result of the systematic efforts of certain organisations to skew electoral competition seems to come from the analysis of a traditional feature of Colombian politics. As described by León Valencia (Citation2020), groups often centred around specific families and known as political clans have dominated regional politics, developing a significant representation also in Congress. Drawing, in some cases, on illegal activities ranging from electoral corruption to violence against candidates, Valencia (Citation2020) explains, they have accumulated significant power, in part thanks to what Valencia (Citation2020, Introduction) describes as the ‘symbiotic’Footnote7 and continuous relation with political parties, including the repartition of votes, material resources and political offices.

In short, powerful organised actors have apparently engaged in the systematic distortion of the electoral competition in both local and congressional elections, possibly influencing the political balance in Congress. Moreover, in Colombia distortions of the electoral competition may have concerned even presidential races, as possibly suggested by the recent Ñeñepolítica scandal. This would not be the first time in the history of the country, as evidenced, for example, by the infamous Proceso 8000 scandal, when the campaign of President Samper was financed also by the Cali drug cartel. What appears particularly worrisome is that the distortion of electoral competition seems to result in large part from the efforts of stable and organised structures. While these practices are widespread, they have concerned and favoured certain political actors or groups over others, thus systematically skewing Colombian politics.

Guatemala

In 1985, Cerezo’s election to the presidency marked the end of military rule in Guatemala. The long civil war between the state and insurgents came to an end in 1996. The end of the conflict did not prove a panacea to the many problems affecting the country, and in 2006 the government and the United Nations created the International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG), an institution whose creation, in cooperation with national institutions, was meant to fight specific criminal organisations.

Similar to the Colombian case, despite its generally recognised democratic or imperfectly democratic character, in Guatemala key non-state actors have deliberately and systematically skewed electoral competition to their benefit. Many of these practices have come to light thanks to the key investigations of local prosecutors and, particularly, the CICIG. In the last decade, several presidents have been sentenced, arrested for or accused of crimes ranging from corruption to illegal campaign financing, while major contenders in the latest presidential election in 2019 have been accused of various crimes including illegal campaign financing and ties with drug cartels. Already investigated for a case of corruption leading to his and Vice-President Roxana Baldetti’s resignation and arrest in 2015, former President Pérez Molina was later investigated for crimes related to his rise to power. In the description of its investigation, the CICIG (Citation2016) highlights how Pérez Molina and Baldetti led a complex criminal structure with political goals. This structure, according to the CICIG (Citation2016), illegally financed the presidential campaign of Pérez Molina in his successful 2011 bid through a money-laundering scheme involving a network of different companies. US authorities have also accused former Vice-President Baldetti of developing ties with a Mexican drug cartel, including the promise of facilitating the cartel’s drug-trafficking activities in exchange for money and even the provision of armed security during the presidential campaign (Prensa Libre Citation2017).

As suggested above, Pérez Molina’s and Baldetti’s are not isolated cases. In 2017, former President Jimmy Morales was investigated by the country’s prosecutors and the CICIG for illegal campaign financing, an investigation apparently contributing to Morales’s decisions not to renovate the CICIG’s mandate and even terminate it prematurely, a decision then suspended by the Constitutional Court. Among the candidates participating in the 2019 presidential contest, Sandra Torres, defeated by current President Giammattei in the runoff, was later accused of and arrested for conspiracy and illegal campaign financing during the 2015 elections. According to the accusations, part of the illegal campaign financing allegedly took place through a scheme of companies belonging, in some cases, to a congressman of Torres’s party (La Prensa Citation2019). In 2020, Mario Estrada, a multiple presidential candidate and leader of the National Change Union (UCN, one of the largest parties in congress), was sentenced in the US for trying to establish an alliance with the Sinaloa drug cartel during the 2019 presidential campaign, an attempt including a request for financial resources and even for the physical elimination of other politicians for electoral reasons (see US Department of Justice Citation2020). On the basis of information that she received during the 2019 campaign from the US Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), Thelma Aldana, a former attorney general, one of the key actors in the fight against corruption and a presidential candidate in 2019, revealed that she was a target of Estrada’s assassination plans (Fernández C Citation2019). Ironically, with controversial timing, during the campaign Aldana was first the object of an arrest warrant for crimes including embezzlement (see El Periodico Citation2019) and was later barred from elections. Aldana has since been granted asylum in the Unites States.

As suggested by the Pérez Molina, Torres and Estrada cases, rather than the result of individual or extemporaneous initiatives, the distortions affecting the electoral game in Guatemala seem to originate from the systematic activities of stable and structured organisations, a point apparently further supported by the CICIG’s (2015) description of what it defines as ‘illicit political-economic networks’.Footnote8 With a regional basis, these networks are involved in both legal and illegal activities that fuel, among other things, illegal campaign financing (CICIG Citation2015, 19–21). As explained by the CICIG (Citation2015, 20), while their boundaries do not coincide with those of political parties, these networks also act in coordination both in Congress and during presidential elections to pursue their political and economic goals.

Although the collaboration between the CICIG and some local prosecutors has contributed to dismantle some illegal networks, Congress’s denial of the CICIG’s request to remove Morales’s immunity in 2017, the decision of Morales not to renew the CICIG’s mandate, and the support provided by current President Giammattei to this decision can be viewed as a reaffirmation of the power of the anti-CICIG front. Therefore, the dismantlement of these networks by the CICIG should not be viewed as a sign of the ability of the democratic system to reject distortions. Rather, it should be viewed as an exceptional intervention that exposed some of the practices and organisations that are structural in Guatemalan politics and that arguably would have survived without the CICIG. The non-renovation of the CICIG’s mandate thus does not bode well for the future of Guatemalan politics.

El Salvador

The end of the civil war in 1992 opened a new phase in El Salvador allowing the transition of former insurgent Frente Farabundo Martí para la Liberación Nacional (FMLN) to electoral politics and the evolution of the country into a more representative political regime. Since the end of the conflict, the FMLN and the right-wing Alianza Republicana Nacionalista (ARENA) have largely dominated El Salvadorean politics. For the first time, in 2019, the presidency was won by a candidate of a different party, Nayib Bukele. Since his election, Bukele’s style of government has raised significant concerns.

During the long era characterised by the alternation of the FMLN and ARENA in power, in spite of its generally recognised democratic label, in El Salvador too key political actors appear to have systematically skewed elections through instruments other than those deriving from the control of the executive. Among the problems affecting El Salvador’s political system, violence and gangs known as pandillas or maras have certainly played a crucial role. According to official estimates, the number of their members would amount to around 65,000 or 1% of the population (Valencia Citation2018). While the power and influence of the pandillas is generally recognised, recent investigations of local prosecutors have highlighted the alleged continuous attempts by traditional parties and high-ranking politicians to take advantage of their capabilities to influence elections. Recently, the Fiscalía (public prosecutors) has accused top members of the FMLN and ARENA, including former national ministers and the current mayor of the capital San Salvador, respectively, of trying to gain the support of two pandillas in the 2014 elections in exchange for money (see Fiscalía General de la República Citation2020a). Videos or recordings, including negotiations concerning the 2014 elections between the pandillas and some of these politicians, have been circulating for years (Martínez and Valencia Citation2016).

In another case, in January 2020, the Fiscal General (Attorney General) submitted to the Congress a request to strip former ARENA presidential candidate and former President of the Legislative Assembly Norman Quijano of his immunity for his alleged attempt to gain the support of the pandillas in the 2014 presidential campaign. Although the Legislative Assembly rejected it, based on witnesses’ accounts and a video of a meeting including Quijano, the Attorney General’s request (Fiscalía General de la República Citation2020b) is useful to highlight the alleged ties among the FMLN, ARENA and the pandillas. Besides describing the competition between ARENA and the FMLN to gain the support of the pandillas, in its request the Fiscalía describes the ability of the pandillas to distort elections through violence, threats and supply of votes (Fiscalía General de la República Citation2020b). Interestingly, the competition between the FMLN and ARENA to gain the favour of the pandillas seems to suggest that these parties viewed these organisations as crucial to win elections. While possibly accurate also for other electoral contests, this perception may have been particularly plausible with respect to the 2014 presidential election, when the FMLN candidate won with a margin of approximately 0.2% over his opponent.

Interestingly, while the Fiscalía describes the creation of a stable relationship between ARENA and the pandillas since the 2014 election, it also notes how the electoral collaboration between the rival FMLN and these criminal organisations dated back to the 2009 presidential campaign when the FMLN won the presidency (Fiscalía General de la República Citation2020b). This would seem to corroborate the existence of systematic and continuous efforts by the country’s traditional parties to skew electoral competition through undemocratic means. Although it could be argued that both ARENA and the FMLN engaged in distortive practices, thus possibly offsetting their illicit advantages, they developed a clear advantage over other parties while, at the same time, hindering the rise of alternative political forces. Moreover, the fact that both parties allegedly gained illicit advantages makes the competition not fairer but more unfair, given that elections are transformed into a competition rewarding those who are most skilled at manipulating the electoral contest.

Importantly, the investigations described above seem to suggest that the attempts to distort elections were not isolated and resulted not from the actions or decisions of specific individuals but, rather, from the systematic initiative of the two parties that have dominated the country since the end of the civil war.

Theoretical and practical implications

The analysis of the category of countries considered in this paper presents important practical and theoretical implications. First, it provides the opportunity to reflect on the definition and classification of political regimes. As noted above, these countries present features other than those of a merely problematic democracy; they also present aspects that distinguish them from other regimes within the competitive non-democratic family. With respect to the elements distinguishing these countries from democratic regimes, their recognition can contribute to a more accurate representation of the state of democracy in the world and may reduce the risk of overestimating its global presence. Moreover, the recurrent attribution of democratic labels to countries where the separation of powers is generally respected but electoral competition is largely and deliberately distorted – although not by the government – calls into question the way the boundaries of democracy are often drawn. In particular, the combination of such a tendency with the readiness of scholars to accept the undemocratic character of regimes where incumbents distort elections after dismantling checks and balances may signal the paradoxical, de facto tendency to consider the intentional, systematic and severe distortion of elections as an insufficient element to define a regime as non-democratic, unless accompanied by other conditions such as the weakening of checks and balances. This is questionable given the widely recognised centrality of elections in any type of democratic regime.

Related to the point above and to the elements distinguishing the countries under consideration from other competitive non-democratic regimes, unlike regimes such as competitive or electoral authoritarianism, where the distortion of the playing field is closely related to the erosion of checks on executive power, these cases may combine systematic and severe distortions of electoral competition and relatively undamaged checks and balances, a perhaps insufficiently studied combination. The recognition of such specificities may complement existing taxonomies and help distinguish problems of democratic quality from symptoms of a non-democratic regime.

Second, fully recognising that democracy may be hijacked through means other than the control of the state is also important from the perspective of the promotion and defence of democracy. While international pressure can prove an effective instrument to promote democracy, it is often directed at abusive governments. In the countries considered in this paper, this pressure should be adapted to their specificities. For example, international pressure should target political parties, political factions or local actors most heavily involved in practices such as vote-buying or illegal campaign financing. This pressure should also concern political forces that, although largely foreign to such practices, take advantage of the alliance with questionable actors. Moreover, initiatives such as the CICIG in Guatemala have shown how international assistance may greatly support democracy in certain contexts. Precisely because they are likely to generate rejection and controversy, similar instruments require significant support at the international level.

Third, what also emerges from the analysis of these regimes are their threatening features. While a key feature and requirement of post-Cold War autocrats has been the ability to maintain power without excessively damaging their democratic credentials (see Levitsky and Way Citation2010; Balderacchi Citation2018), in countries such as Colombia, El Salvador and Guatemala, systems of power have perverted essential democratic mechanisms in even more clandestine ways that are less likely to generate international pressure. The distortions described in these countries are certainly less visible than those of autocrats eroding checks and balances from the national government and can be easily mistaken for diffused problems of democratic quality. Although power is obviously less concentrated than in competitive authoritarianism, precisely this difference makes the identification of severe distortions of the electoral arena even more complicated.

Moreover, such regimes seem less reversible than competitive and electoral authoritarian regimes. Dismantling the institutional arsenal of previous competitive authoritarian governments may be relatively doable for a highly motivated new government. This seems to emerge, for example, from the experience of Lenín Moreno in Ecuador. Although Moreno’s democratic performance is subject to different interpretations, it seems clear that Moreno was successful in the dismantlement of former President Correa’s structure of power – an example, for some, of competitive authoritarianism. Instead, it may be much more difficult to eliminate practices such as those described in Colombia, El Salvador and Guatemala, these being associated with hardly eradicable problems such as the presence of illegal organisations, corruption and poverty.

Finally, this paper can also complement the burgeoning literature on autocratisation or similar processes. A number of authors (Lührmann and Lindberg Citation2019; Cassani and Tomini Citation2020; Bermeo Citation2016; Dresden and Howard Citation2016) tend to consider such processes the result of the action of either the incumbent or the state. When considering democratic regimes, in addition to invasion, Lührmann and Lindberg (Citation2019, 1104–1105) only consider autocratisation processes brought about by incumbents or the military, while apparently equating democratic erosion with incumbents’ gradual dismantlement of democracy. While Bermeo (Citation2016, 5) refers to ‘democratic backsliding’ as a ‘state-led’ process, Dresden and Howard (Citation2016,1123–1124) address the debate by adopting the concept of ‘authoritarian backsliding’ as a process originating from a powerful government. By referring to autocratisation as a process affecting the balance of power between rulers and citizens, Cassani and Tomini (Citation2020, 277) too seem to equate autocratisation with a process essentially driven by the government. Given Lührmann and Lindberg’s (Citation2019, fn 59) observation that autocracy is generally viewed as a mere ‘non-democracy’, this paper suggests that an autocratisation process does not necessarily result from the action of the state or of the government and that, therefore, it may also occur through different dynamics or patterns, including one in which a democratic regime evolves into a non-democratic regime without the previous erosion of checks and balances. Importantly, this is not to say that the cases under consideration have necessarily autocratised or increased their non-democratic features in the last decade but, rather, that the non-state distortions responsible for their non-democratic character may produce an autocratisation process.

Conclusions

In commonly defined democracies such as Colombia, Guatemala and El Salvador, actors and organisations other than the incumbent and the state have secured a significant, continuous advantage over competitors through the systematic and profound distortion of electoral competition. This undermines the idea that the typical problems described in these countries are mere dysfunctions of democracy and highlights a number of important theoretical and practical implications. In particular, it questions the consolidated tendency to classify similar countries as democratic or imperfectly democratic and calls for the definition of a largely unrecognised category of non-democratic regimes.

The countries under consideration seem examples of a more general phenomenon. Some of the problems related to the scenario described above (eg vote-buying, organised crime, electoral violence) are widespread in Latin America as well as in other regions. Although not sufficient in themselves to characterise a regime as non-democratic, they may contribute, when combined with the conditions discussed above, to the evolution of imperfect democracies into cases of competitive non-democratic regimes. Moreover, the opportunity to demonstrate the non-democratic character of these regimes is contingent on the availability of information concerning particularly secretive, although organised and systematic, activities. Further research on the topic is certainly needed and could highlight the existence of an even more diffused problem.

A deeper understanding of the type of cases considered in this paper may complement the debate on political regimes and shed further light on a crucial and recurring phenomenon in Latin America and beyond.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their very helpful comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Claudio Balderacchi

Claudio Balderacchi is Assistant Professor in the Department of International Relations and Political Science at Universidad del Norte, Colombia. His research interests include democratization and autocratization processes, regime change, and hybrid political regimes.

Notes

1 For the definitions of competitive and electoral authoritarianism, see Levitsky and Way (Citation2010) and Schedler (Citation2006), respectively.

2 ‘Indicator/data’ in Goertz (Citation2006); ‘data-indicator’ in Goertz (Citation2020).

3 On the Regimes of the World index, see also Lührmann et al. (Citation2018) and Coppedge et al. (Citation2020b). Since 2000, the value of the Regimes of the World measure for Colombia, El Salvador and Guatemala has been 2, which corresponds to electoral democracy (Coppedge et al. Citation2020a, Citation2020b).

4 In the Dataset Users’ Manual of Polity 5, regimes are indicated as full or partial democracies when the value of Polity ranges from 7 to 10 or from 1 to 6, respectively (Marshall and Gurr Citation2020b, 35). Since 2000, the value of Polity for Colombia and Guatemala has been 7 and 8, respectively, while for El Salvador the value was 7 from 2000 to 2008 and has been 8 since 2009 (Marshall and Gurr Citation2020a).

5 With the exception of Guatemala in its 2020 edition, the Bertelsmann Transformation Index also has included Colombia, El Salvador and Guatemala in the camp of democracies, however defective or highly defective, since its 2006 edition (Bertelsmann Stiftung Citation2020a). The non-democratic classification of Guatemala in its 2020 edition is not due to negative scores concerning the freedom and fairness of elections, but rather due to the failure to reach a minimal score in the ‘Effective power to govern’ and ‘Separation of powers’ dimensions (Bertelsmann Stiftung Citation2020a, Citation2020b).

6 During the writing of this paper, the government’s response to popular protests against a tax reform proposal has generated significant concerns and criticisms, both domestically and internationally.

7 Author’s translation of ‘simbiótica’.

8 Author’s translation of ‘redes político-económicas ilícitas’.

Bibliography

- Albarracín, Juan. 2018. “Criminalized Electoral Politics in Brazilian Urban Peripheries.” Crime, Law and Social Change 69 (4): 553–575. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10611-017-9761-8.

- Ardila Arrieta, Laura. 2014. “La foto de la parapolítica de 2010 a 2014.” Accessed September 15, 2020. https://lasillavacia.com/historia/la-foto-de-la-parapolitica-de-2010-2014-46856

- Arjona, Ana. 2016. Rebelocracy: Social Order in the Colombian Civil War. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Balderacchi, Claudio. 2018. “Political Leadership and the Construction of Competitive Authoritarian Regimes in Latin America: Implications and Prospects for Democracy.” Democratization 25 (3): 504–523. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2017.1388229.

- Bermeo, Nancy. 2016. “On Democratic Backsliding.” Journal of Democracy 27 (1): 5–19. doi:https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2016.0012.

- Bertelsmann Stiftung. 2020a. “BTI 2006-2020 Results Dataset.” Accessed November 25, 2020. https://www.bti-project.org/en/index/political-transformation.html

- Bertelsmann Stiftung. 2020b. “Methodology.” Accessed December 27, 2020. https://www.bti-project.org/en/methodology.html

- Botero, Felipe, Gary W. Hoskin, and Mónica Pachón. 2010. “Sobre forma y sustancia: Una evaluación de la democracia electoral en Colombia.” Revista de Ciencia Política 30 (1): 41–64. doi:https://doi.org/10.4067/S0718-090X2010000100004.

- Carothers, Thomas. 2002. “The End of the Transition Paradigm.” Journal of Democracy 13 (1): 5–21. doi:https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2002.0003.

- Cassani, Andrea. 2014. “Hybrid What? Partial Consensus and Persistent Divergences in the Analysis of Hybrid Regimes.” International Political Science Review 35 (5): 542–558. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0192512113495756.

- Cassani, Andrea, and Luca Tomini. 2020. “Reversing Regimes and Concepts: From Democratization to Autocratization.” European Political Science 19 (2): 272–287. doi:https://doi.org/10.1057/s41304-018-0168-5.

- CICIG. 2015. “Financiamiento de la política en Guatemala.” Accessed May 29, 2020. https://www.cicig.org/uploads/documents/2015/informe_financiamiento_politicagt.pdf

- CICIG. 2016. “Caso cooptación del Estado de Guatemala.” Comunicado 047, June 2. Accessed June 2, 2020. https://www.cicig.org/casos/caso-cooptacion-del-estado-de-guatemala/

- Collier, David, and James Mahon. 1993. “Conceptual ‘Stretching’ Revisited: Adapting Categories in Comparative Analysis.” American Political Science Review 87 (4): 845–855. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/2938818.

- Collier, David, and Steven Levitsky. 1997. “Democracy with Adjectives: Conceptual Innovation in Comparative Research.” World Politics 49 (3): 430–451. doi:https://doi.org/10.1353/wp.1997.0009.

- Coppedge, Michael, John Gerring, Carl H. Knutsen, . . ., and Daniel Ziblatt. 2020. “V-Dem [Country-Year/Country-Date] Dataset v10.” Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project. doi:https://doi.org/10.23696/vdemds20.

- Coppedge, Michael, John Gerring, Carl H. Knutsen, . . ., and Daniel Ziblatt. 2020b. “V-Dem Codebookv10.” Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project.

- Corrales, Javier. 2015. “The Authoritarian Resurgence: Autocratic Legalism in Venezuela.” Journal of Democracy 26 (2): 37–51. doi:https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2015.0031.

- Corte Suprema de Justicia, Sala especial de primera instancia. 2019. “SEP 00100-2019. Radicación No52418.” Magistrado Ponente: Ariel Augusto Torres Rojas (September 12, 2019). Accessed May 15, 2020. http://www.cortesuprema.gov.co/corte/wp-content/uploads/prensa/SEP00100-2019.pdf

- Corte Suprema de Justicia, Sala de casación penal. 2020. “SP954-2020. Radicación 56400.” Magistrado Ponente: Luis Antonio Hernández Barbosa (May 27, 2020). Accessed June 20, 2020. http://www.cortesuprema.gov.co/corte/index.php/2020/05/29/corte-suprema-ratifica-condena-contra-aida-merlano-y-remite-sentencia-al-senado-para-que-aplique-la-silla-vacia/

- Dresden, Jennifer R., and Marc Morjé Howard. 2016. “Authoritarian Backsliding and the Concentration of Political Power.” Democratization 23 (7): 1122–1143. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2015.1045884.

- El Periodico. 2019. “Giran orden de aprehensión contra Thelma Aldana.” Accessed October 12, 2020. https://elperiodico.com.gt/nacionales/2019/03/19/giran-orden-de-aprehension-contra-thelma-aldana/

- El Tiempo. 2016. “10 años de un huracán llamado ‘parapolítica’.” Accessed September 15, 2020. https://www.eltiempo.com/archivo/documento/CMS-16647142

- Fernández C., Juan Manuel. 2019. “DEA alertó a Thelma Aldana sobre plan de Mario Estrada para asesinarla.” Accessed October 12, 2020. https://www.prensalibre.com/guatemala/politica/dea-alerto-a-thelma-aldana-sobre-plan-de-mario-estrada-para-asesinarla-exclusiva/

- Fiscalía General de la República. 2020a. “Fiscalía presentó requerimiento contra miembros de partidos políticos por fraude electoral y agrupaciones ilícitas.” (written by Arturo Villeda). Accessed June 11, 2020. http://www.fiscalia.gob.sv/fiscalia-presento-requerimiento-contra-miembros-de-partidos-politicos-por-fraude-electoral-y-agrupaciones-ilicitas/

- Fiscalía General de la República. 2020b. “Denuncia de antejuicio y petición de desafuero.” REF.9-UIF-2013. Accessed June 11, 2020. https://www.asamblea.gob.sv/sites/default/files/documents/correspondencia/73A7E6A3-20E0-4AE4-AC09-4EB1CA533094.pdf

- Gerring, John. 1999. “What Makes a Concept Good? A Criterial Framework for Understanding Concept Formation in the Social Sciences.” Polity 31 (3): 357–393. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/3235246.

- Gilbert, Leah, and Payam Mohseni. 2011. “Beyond Authoritarianism: The Conceptualization of Hybrid Regimes.” Studies in Comparative International Development 46 (3): 270–297. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s12116-011-9088-x.

- Goertz, Gary. 2006. Social Science Concepts: A User’s Guide. Kindle ed. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Goertz, Gary. 2020. Social Science Concepts and Measurement. Princeton: Princeton University.

- Howard, Marc Morjé, and Philip G. Roessler. 2006. “Liberalizing Electoral Outcomes in Competitive Authoritarian Regimes.” American Journal of Political Science 50 (2): 365–381. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2006.00189.x.

- La Prensa. 2019. “La Fiscalía de Guatemala acusa a Sandra Torres de negociar campaña presidencial ilegal.” Accessed October 10, 2020. https://www.laprensa.hn/mundo/1316827-410/fiscal%C3%ADa-de-guatemala-sandra-torres-guatemala

- Levitsky, Steven. 2018. “Democratic Survival and Weakness.” Journal of Democracy 29 (4): 102–113. doi:https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2018.0066.

- Levitsky, Steven, and Lucan A. Way. 2010. Competitive Authoritarianism: Hybrid Regimes after the Cold War. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Lührmann, Anna, Marcus Tannenberg, and Staffan I. Lindberg. 2018. “Regimes of the World (RoW): Opening New Avenues for the Comparative Study of Political Regimes.” Politics and Governance 6 (1): 60–77. doi:https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v6i1.1214.

- Lührmann, Anna, and Staffan I. Lindberg. 2019. “A Third Wave of Autocratization Is Here: What Is New about It?” Democratization 26 (7): 1095–1113. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2019.1582029.

- Mainwaring, Scott, and Aníbal Pérez-Liñán. 2015. “Cross-Currents in Latin America.” Journal of Democracy 26 (1): 114–127. doi:https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2015.0003.

- Marshall, Monty G., and Ted R. Gurr. 2020a. “Polity 5: Political Regime Characteristics and Transitions, 1800-2018.” Annual Time-Series Dataset. Center for Systemic Peace Dataset. Accessed August 27, 2020. https://www.systemicpeace.org/inscrdata.html

- Marshall, Monty G., and Ted R. Gurr. 2020b. “Polity 5: Political Regime Characteristics and Transitions, 1800-2018.” Dataset Users’ Manual. Center for Systemic Peace. Accessed August 27, 2020. https://www.systemicpeace.org/inscrdata.html

- Martínez, Carlos, and Roberto Valencia. 2016. “EL FMLN hizo alianza con las pandillas para la elección presidencial de 2014.” Accessed November 14, 2020. https://elfaro.net/es/206005/salanegra/18560/El-FMLN-hizo-alianza-con-las-pandillas-para-la-elección-presidencial-de-2014.htm

- Merkel, Wolgang. 2004. “Embedded and Defective Democracies.” Democratization 11 (5): 33–58. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13510340412331304598.

- Mudde, Cas, and Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser. 2013. “Exclusionary vs. Inclusionary Populism: Comparing Contemporary Europe and Latin America.” Government and Opposition 48 (2): 147–174. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2012.11.

- Mufti, Mariam. 2018. “What Do We Know about Hybrid Regimes after Two Decades of Scholarship?” Politics and Governance 6 (2): 112–119. doi:https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v6i2.1400.

- Munck, Gerardo, and Richard Snyder. 2007. Passion, Craft, and Method in Comparative Politics. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Prensa Libre. 2017. “Roxana Baldetti recibió más de US$250 mil y seguridad armada de los Zetas.” Accessed October 5, 2020. https://www.prensalibre.com/guatemala/justicia/roxana-baldetti-recibio-250-mil-de-los-zetas-durante-campaa-electoral/

- Sartori, Giovanni. 1970. “Concept Misformation in Comparative Politics.” American Political Science Review 64 (4): 1033–1053. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/1958356.

- Schedler, Andreas. 2006. “The Logic of Electoral Authoritarianism.” In Electoral Authoritarianism: The Dynamics of Unfree Competition, edited by Andreas Schedler, 1–23. Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

- Schedler, Andreas. 2014. “The Criminal Subversion of Mexican Democracy.” Journal of Democracy 25 (1): 5–18. doi:https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2014.0016.

- Semana. 2020. “Ñeñe Hernández: quién era el hombre que habló de compra de votos para Duque.” Accessed September 25, 2020. https://www.semana.com/nacion/articulo/nene-hernandez-prontuario-del-hombre-que-vinculo-a-uribe-y-duque-en-comprar-votos/655081/

- Transparency International. 2019. “Political Integrity Lacking in Latin America and the Caribbean, Especially Around Elections.” Accessed July 27, 2020. https://www.transparency.org/en/news/political-integrity-lacking-in-latin-america-and-the-caribbean-especially-a#

- Trejo, Guillermo, and Sandra Ley. 2020. Votes, Drugs, and Violence: The Political Logic of Criminal Wars in Mexico. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- US Department of Justice. 2020. “Mario Estrada, Former Guatemalan Presidential Candidate, Sentenced to 15 Years in Prison in Connection with Scheme to Import Tons of Cocaine into the United States.” February 11, 2020. Accessed June 3, 2020. https://www.justice.gov/usao-sdny/pr/mario-estrada-former-guatemalan-presidential-candidate-sentenced-15-years-prison

- Valencia, Roberto. 2018. “El país de las Maras.” Accessed December 3, 2020. https://elfaro.net/es/201806/columnas/21997/El-pa%C3%ADs-de-las-maras.htm

- Valencia, León. 2020. Los clanes políticos que mandan en Colombia. Bogotá: Planeta.

- Vargas Betancourt, Camilo. 2018. “Análisis de los factores de riesgo para las elecciones nacionales de 2018.” In Mapas y factores de riesgo electoral: Elecciones nacionales Colombia 2018, ed. Misión de observación electoral, 30–47. Accessed December 2, 2020. https://moe.org.co/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/Mapas_y_Factores_de_Riesgo_Electoral_MOE_Elecciones_en_Colombia_2018.pdf

- Wigell, Mikael. 2008. “Mapping ‘Hybrid Regimes’: Regime Types and Concepts in Comparative Politics.” Democratization 15 (2): 230–250. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13510340701846319.