Abstract

Increasing community and parental connection with schools is a widely advocated means of improving levels of student learning and the quality and accountability of education systems across South Asia. This paper draws on a mixed-methods study of accountability relations in education in the Indian states of Rajasthan and Bihar. It explores two questions: what formal platforms exist to enhance connections between socially disadvantaged families and the schools serving them; and (how) do they influence engagement with student learning? It finds that various platforms have proliferated across public, low-cost private and non-government schools. But, while they promote enrolment attendance and monitoring, a substantive focus on student learning is empirically demonstrated to be missing everywhere. The paper argues that an apparently surprising similarity of (dis)connection is located in system features that are common across school types, locations and social structures. It proposes that this is a ‘field’ in which connection, facilitated by various platforms, is performed according to bureaucratised norms of accountability that even pervade family and community responses. Seeing this as a socially constituted ‘field’ that constrains meaningful discussion of learning across schooling provision for disadvantaged families contributes new insight for accountability-focused reforms in education.

Introduction

In South Asia, the past two decades have seen significant improvement in universalising access to schooling. Rates of primary school enrolment across the region are now high, and the numbers of out-of-school children are decliningFootnote1 (although significant numbers remain excluded; see Dyer and Rajan Citation2021). While South Asian education systems have made impressive gains in these respects, there are urgent concerns about what the World Bank (Citation2018) characterises as a ‘learning crisis’ across the Global South. South Asian countries (except Sri Lanka) persistently record ‘very low mean levels of student achievement in mathematics, reading, and language’ (Asim et al. Citation2017, 76) and learning outcomes ‘remain stubbornly resistant to improvements’ (Asim et al. Citation2017, 75): schooling, for many children, is not equating to learning (Pritchett Citation2013). Enhancing education quality and improving learning outcomes are key dimensions of regional education policy agendas, in line with commitments made to Sustainable Development Goal 4, ‘Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all’ (https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal4) (Asadullah, Savoia, and Sen Citation2020).

The parlous state of learning outcomes, and indeed their aforementioned resistance to improvement, has revealed the limitations of input-orientated and access-focused strategies for education inclusion, and demanded introspection about accountability for learning itself within education systems. Following from the 2004 World Development Report’s focus on accountability as integral to making services work for poor people (World Bank Citation2004), accountability was scrutinised in a dedicated Global Education Monitoring Report (UNESCO Citation2017), and has become a ‘cornerstone of contemporary education policy’ (Smith and Benavot Citation2019, 193). In South Asia, India’s 2020 National Education Policy (NEP 2020) (GoI Citation2020), for example, mentions accountability nine times, demonstrating a new national turn towards accountability that aligns with this global trend. Scholarly research on accountability has, accordingly, proliferated (Yan Citation2019). In the education sector, much of this research focuses on improving system performance and efficiency (eg Pritchett Citation2015; Mbiti Citation2016) to raise learning outcomes (eg Evans and Popova Citation2016), and on ‘stakeholder’ roles, capacity gaps and lack of voice (eg Yan Citation2019; Aiyar et al. Citation2009). Smith and Benavot (Citation2019, 194) argue, however, that ‘most accountability reforms in education do not achieve their intended impact’ and suggest that ‘a critical condition for strengthening accountability in education involves providing different actors with an opportunity to articulate and represent their views as the accountability process unfolds’ (see also Aiyar et al. Citation2009).

This paper draws these discussions of accountability, learning and actor engagement together to focus on relations of accountability in India, where elementary schooling is often considered to be a physical and discursive space which is largely closed off from children’s families and communities (Kumar Citation2008). Policy discourses themselves acknowledge this lack of connection. The NEP 2020 intends to ‘overhaul […] the service environment and culture of schools’ in the search for what it envisages as a ‘vibrant, caring, and inclusive communities of teachers, students, parents, principals, and other support staff, all of whom share a common goal: to ensure that our children are learning’ (GoI Citation2020, 21). This intention affirms and expands the stance of the national flagship programme, the Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan (SSA),Footnote2 which situated itself in part as a ‘response to the demand for quality basic education all over the country’, and advocated ‘an education system that is not alienating and that draws on community solidarity’ (GoI Citation1999). An important dimension of Indian policy discourse around ‘sharing’, ‘inclusion’, ‘alienation’ and ‘solidarity’ is concern over inequalities linked to the now marked stratification of the education system. Public dissatisfaction with the quality of state-managed provision, and the marketisation of education to meet demand and compensate for state gaps, have encouraged the growth of privately managed, low-fee paying schools (LFPSs) (Muralidharan and Kremer Citation2006; Pritchett Citation2013), and further delegitimised government provision (Kingdon Citation2020). In this context, community and parental participation is now folded into policy and public discourses of roles and mutual responsibilities for improving the schooling system for all learners (Dyer et al. Citation2022; GoI Citation2009; Maitrayee and Sriprakash Citation2018). Concerns over system stratification and enhancing stakeholder roles to address educational inequalities are of course not unique to India, and echo across the South Asian region (cf. Asadullah, Alim, and Hossain Citation2019; Asadullah and Chaudhury Citation2015).

Despite policy and scholarly agreement about the need for community engagement in policy processes, and the global and national-level advocacy for it, what seems nevertheless to be lacking is an in-depth analysis of why reforms that do so play out in ways that become characterised as ‘policy failure’. This is the point of departure for our analysis of the school–home–community interactions stimulated by policy initiatives in India, and what they tell us about learning-focused connection between schools and homes. We use the term ‘connection’ to denote a space and intersection between school and family/community, where they come together to communicate about a child’s education. We understand this as a spectrum, running from coherent and complementary interests, actions and expectations of sets of actors focused on facilitating a child’s learning, to a ‘disconnect’ characterised by misaligned interests, actions and expectations and absent focus on co-facilitating the learning of the child.

We will empirically show that, despite the now many formal platforms aiming to promote learning-focused connections between parents, communities and schools, there remains a considerable ‘disconnect’. The content of communications is remarkably similar across public (government-managed), low-cost private and non-government organisation (NGO) schools, across schools with different levels of ‘social distance’ with families, across rural and urban areas, and across two Indian states (Rajasthan and Bihar). We recognise that school–family/community relations and communications focused on student learning are by their very nature challenging. Further, the kinds of connections that policies seek to promote are socially mediated, and in the Indian context analysis should be attentive to matters of caste, gender, positional hierarchies and structural disadvantage. While the perspective of socially mediated relations is certainly important, we find that it does not adequately explain the content of school–family/community communications and, by extension, the nature of their relations.

We will argue that what at first appears to be a surprising similarity of (dis)connection across the diverse school situations we examine is likely to be located in system features that are common across school types, school locations and social structures. The common ‘system’ consists of the cultures, mindsets, expectations, norms, procedures and practices – the Bourdieusian ‘field’ (Bourdieu and Wacquant Citation1992) – constructed by decades of the state-driven agenda of universalising formal education. Indeed, these were not merely mediated by the state but actively set and driven by it; and what emerges is what Foucault describes as ‘the gradual, piecemeal, but continuous takeover by the state of a number of practices, ways of doing things, and, if you like, governmentalities’ (Foucault Citation2010, 77).

While Indian elementary education has been analysed from a governmentality lens (see Corbridge et al. Citation2005), our contribution is to augment this literature by showing that the ‘continuous takeover by the state of a number of practices’ is also manifested in school–family/community connections. The nature of these connections, and the artefacts they produce, reflect and reproduce a pervasive culture of bureaucratic performativity (Apple Citation2004). This performativity bureaucratises accountability, converting the formal into the formalistic and ceremonious. What we are particularly interested in here is how this works to preclude the focus on student learning that, ostensibly, is the raison d’être of the education system (and of accountability discourses), and how this plays out for those in positions of social and structural disadvantage.

The paper proceeds as follows. We first briefly explain the platforms for connection that we will examine, and then set out our research design, methodological approach and empirical context. We next examine the empirical field of bureaucratised accountability relations, beginning with insights from qualitative data, including vignettes illustrative of ‘connections’ in three different school management types, followed by quantitative data analysis. We then reflect on dull performativity, the nature of school–family–community relations and why they are redolent of a wider ‘field’ of bureaucratised accountability relations in education in India. We conclude that the field is socially constituted in ways that constrain meaningful discussion of learning across schools, which has important implications for accountability reforms in education in India, and beyond.

Finding ‘connection’: policy ideals and empirical practices

Finding connection has been framed in India by two processes that converge around a broad ideal of community-driven development (Mansuri and Rao 2013) and community participation in education (Yan Citation2019). One such process is decentralisation, supported by the 73rd and 74th Constitutional Amendments, which emphasise the role of local elected bodies in (educational) governance (Jha et al. Citation2014). The second is the notion of school-based governance, reflected in sectoral policies, programmes and laws that emphasise the role of stakeholders, and particularly the ‘community’ (which, outside of policy, is a nebulous and contested concept) (Aiyar et al. Citation2009). Key examples of policy discourses reflecting these processes are the SSA’s objective of ‘community ownership of school based interventions through effective decentralisation’ (GoI Citation1999) and the 2009 Right to Free and Compulsory Education (RtE) Act’s delineation of responsibilities specific to different stakeholders, including parents and teachers (GoI Citation2009; Dyer et al. Citation2022). Reflecting the turn towards accountability in the context of the ‘learning crisis’, discussed above, the NEP 2020 identifies the ‘community’ as one of various ‘education system participants and stakeholders’ with roles in systemic accountability to all learners (GoI Citation2020, 31).

On the ground, reflecting policy directives, multiple ‘formal’ platforms now exist for ‘connection’ between schools and families, and between schools and communities: school management committees (SMCs), parent–teacher meetings (PTMs), annual school day celebrations, bal sabhas (children’s assemblies), circulars and notices generated by the school for parents, home-school diaries, and home visits by school representatives. Although education policymakers have apparently ‘come to view active community participation as an effective means of promoting primary education’ (Govinda and Diwan (Citation2003, 12; see also Maitrayee and Sriprakash Citation2018), the local institutions established for this purpose have generally underperformed in their expected role of co-ordinating connections between schools and families (Banerjee and Duflo Citation2008; Aiyar et al. Citation2009; Bruns, Filmer, and Patrinos Citation2011; Jha et al. Citation2014).

Research design and context

This paper draws on quantitative and qualitative data from a sequential mixed-method study in the states of Bihar and Rajasthan. In both states, about 5% of children are out of school; in Bihar, just 76.1% of enrolled children transition from primary Grade 5 to upper primary (Grades 6–8), while in Rajasthan the transition rate is 91.6% (NIEPA Citation2017; GoI Citation2017). In both states, in 2018, fewer than 40% of Grade 5 students in government schools could read a Grade 2 level text and more than three-quarters of all Grade 5 students could not do Grade 2 level arithmetic operations (ASER Citation2019).

We conducted empirical research in two districts, Patna (Bihar) and Udaipur (Rajasthan). The qualitative phase came first, with a sample in each district of 12 government and LFPSs and, in Udaipur only, non-formal education centres (known locally as NFEs), grouped into a rural and an urban cluster, each of six schools (n = 24; all Hindi-medium). For each school, we explored the perspectives and experiences of families, community members, teachers, principals and monitoring agencies (depending on school type), using individual and group interviews, observations and focus group discussions (FGDs). (All names have been changed to ensure anonymity.)

Quantitative data were collected through surveys from December 2019 to March 2020. Representative schools were chosen as follows. We first delineated geographical clusters in rural and urban areas of the two districts. Government schools and LFPSs were identified in each cluster using the government’s Unified District Information System for Education and then chosen randomly. NGO schools were identified using separate inquiries among NGOs and chosen randomly. In each district, 25 schools each from rural and urban clusters were chosen in this manner. For each chosen school, we identified representative teachers and parents, as well as community members from local government and other locally prominent individuals, and captured their responses in a survey questionnaire. In Patna, after surveys of 36 schools were completed, fieldwork had to stop because of Covid-19 induced lockdowns; in Udaipur, the selected 50 schools had been covered by then. presents information on the number of schools (government, LFPSs, NFE) by rural and urban location across the two districts. also gives some details of the 403 families and 70 community leaders surveyed across 86 schools. Our surveys omitted community leaders in LFPS areas because during the qualitative phase we found that they did not engage with LFPSs and did not have information about them. (This paper does not draw on the teacher surveys that were also conducted.)

Table 1. Information about schools and respondents.

provides summary background statistics regarding the 403 families surveyed. The majority of families were from disadvantaged social groups. Further, for most of them the income source was unstable and located in the ‘informal’ sector, with only 18% having salaried employment. In the rural clusters, a large number of adults engage in agriculture-related work, with some migration. The urban clusters are commercial and residential neighbourhoods in heterogeneously populated areas; men work in occupations such as rickshaw driving and vegetable vending, and women typically work as domestic maids or in home-based handicrafts and tailoring work. In both rural and urban areas, many families work as daily wage labourers in agriculture, construction and hotel industries.

Table 2. Backgrounds of surveyed families.

The empirical field of bureaucratised accountability relations

This section explores the empirical field of bureaucratised accountability relations, presenting a composite picture of diverse situations from our sites. It presents three vignettes, of a rural government school, an urban LFPS and a rural NFE, which we use to introduce the ‘platforms’ in use across schooling types (government, private low cost and non-government provision) to promote connections (such as SMCs, home visits, diary communications and PTMs), and to ground our qualitative analysis of the kinds of connection that these platforms generate. The section concludes by presenting quantitative data and findings about connection.

Connections in government schools

Our first vignette describes aspects of connection in Madhopur, a senior-secondary government school in the rural Adivasi (tribal) area of Udaipur. It gives a snapshot of pedagogical routines and illustrates aspects of bureaucratised accountability relations between teachers and parents and in the SMC’s functioning.

Madhopur has 14 teachers, deployed such that of the five appointed to teach across Grades 1–8, only two work in the primary (Grades 1–5) levels. Only these two live in the village and are known by name to parents; others commute from urban centres. Since his arrival in 2018, the principal has ‘put the school in order’: teachers can no longer come at any time of the day, sign and leave; there is a morning assembly; and students do not leave campus during school hours.

The primary section averages about 13 boys and girls per grade, all local and from the Adivasi community. Most parents have not been to school themselves. There is considerable irregularity in student attendance, and girls are tasked with household responsibilities when not at school. Children from the dominant Rajput community, and other castes who can afford it, go to a nearby private school: their fathers have studied at least to Grade 10.

In class, students are repeatedly told to ‘memorise’; teachers tell us which students are ‘dull/weak’ (kamzor) and ‘smart’ (tez) based on their ability to memorise. Much class time is spent watching Smart Boards which deliver content from the state curriculum, but on which teachers have not been trained. One day, Grades 1–5 sit together watching the Board while the teacher sits there busy with library documentation. Another day, the Board occupies children while the teacher documents their height and weight. Children watch the same content again and again.

Grade 5 student Yashavsi’s mother tells us, ‘No teaching happens in lower classes. Teachers switch on the “TV” and ask students to watch it’. Asked if she goes to school and raises this issue, she says ‘Who will go and talk to them? If I go and say something, they will ill-treat my daughter. Also, they do not take me seriously as I am not well-read. And I don’t have time as I do household chores and farming’. But she does go to the school for Republic and Independence Day functions and ‘whenever they call me for meetings, although meetings happen very rarely, maybe once or twice a year’. Most parents are, like her, irregular visitors to the school. But some, like Grade 2 student Gunjan’s mother, never go. She explains: ‘I never went to school. I do not get time. I work in a hostel as a cook and also do the household chores’.

Madhopur’s teachers visit homes to conduct the village dropout/out-of-school-children survey and for bal sabhas (both mandatory), to collect documents for administrative use, to call children for Board exams or check why a child has not been attending. Grade 5 Noji’s mother tells us that the teacher had come home to check why Noji had been absent; the other teacher, who she knows by name as he lives in the village, had visited to collect a photograph for the Board exam form.

The names of Madhopur’s SMC members are painted on the wall beside the principal’s office (but not updated). A parent member tells us the principal calls her once every a month or two to sign documents. But although SMC members are informed as to what they are signing, there are no meetings. Parents and community representatives (Ward Panch, Sarpanch) tell us they visit the school for SMC-related business when called in, but say that as they aren’t ‘educated’ they follow the principal’s decisions as he would know better on issues pertaining to the school.

School management committees

Any ‘recognised school’ imparting elementary education, regardless of type, is legally required to constitute an SMC comprising elected representatives of the local authority, children’s parents/guardians and teachers (GoI Citation2009 [21/1]); 75% of SMC members must be parents/guardians, with ‘proportionate representation’ (unspecified) of disadvantaged groups; and altogether, 50% of SMC members must be women (ibid 21/2). The specific functions designated for the SMC are to (1) monitor the working of the school, (2) prepare and recommend the school development plan and (3) monitor grant utilisation – alongside other functions ‘as may be prescribed’ (ibid).

SMCs are now the principal means by which community engagement with the school is inscribed into the education system. While that implies that SMCs are a crucial mechanism for connection and mutual accountability, there is agreement in the literature that their functioning ‘leaves much to be desired’, with a ‘huge gap’ between policy and practice in their formation and functioning (Jha et al. Citation2014, 27; Carr-Hill et al. Citation2018; Yan Citation2019). The participation ‘induced’ (Mansuri and Rao Citation2012) and mediated by the structure that policy has put in place formalises community representation in institutions of local governance, but does not necessarily result in the voices of all being heard, or heard equally; for women in particular, patriarchal norms still present challenges to their participation as equals in SMC meetings – and more so if they are uneducated (Jha et al. Citation2014).

Across our sample, SMC meetings take place rarely, or not at all. In Magri school, a teacher told us: ‘SMC meetings do not happen, but we call parents, they come to the school, sign, and go back. Most parents cannot afford to visit the school, as they will have to lose out on their daily wage’. The principal of Amloi’s rural government school, showing a display board listing SMC members, affirmed that representatives are not elected, but identified by the school: ‘We call people from the village. Whoever seems understanding and reliable, we ask them to be a member, and write their name’. In an FGD with Amloi villagers, three SMC members said meetings focus on ‘regularity of students and teachers, whether midday meals are being provided properly or not, and the importance of schooling’. Thus, for them, ‘education is discussed’. The father of a Grade 1 girl here, whose wife is an SMC member, reported: ‘The meeting happens when the teacher schedules it. They call us, she visits the school, signs the register and comes back. Since she is illiterate, she puts her thumbprint. I don’t go to the school’.

These accounts show how the SMC ‘performs’ accountability in light of legal and habitual norms of bureaucratic management, such that it apparently functions – yet without meaningful community connection. The silence of Madhopur’s SMC over the (mis)use of the ‘TV’ is particularly telling, for this is an issue relating to student learning over which parents have concerns that appear impossible to raise in this forum. This performative trend is widespread: connection with the community via the SMC is initiated by the school; and it is bureaucratised via the managerial scope of its concerns and signing off by SMC members. The signature itself is a presumed act of agency, an index of ability to operate as a modern citizen and of capacity for self-representation (Cody Citation2009). In government schools, the SMC is a community-level platform for connection whose character is shaped by the bureaucratised ‘field’ of education system management in general, and the management-orientated directives of the RtE Act specifically, which combine to exclude a remit focused on learning.

Home visits, enrolment drives and bal sabhas

Teachers in government schools are mandated to make home visits (GoI Citation2009). In our rural clusters, teachers focus home visits on collecting specific documents, registering students for Board exams or, since irregular attendance is an issue in many schools (as illustrated in the Madhopur vignette), discussing why a student is attending irregularly. Teachers in our urban clusters mostly make home visits only at the beginning of the year to conduct surveys of out-of-school children and dropouts, and in connection with the annual enrolment drive. All government schools have to conduct this enrolment drive, which takes the form explained by Amloi’s principal: ‘We take students around the village, they shout slogans on the importance of education, and ask parents to send their children to school’. They also have to organise bal sabhas – meetings in the public space to promote community participation, create awareness about the importance of schooling, and showcase students’ skills. How accountability is bureaucratised, and the pressures on school and community members to deliver an unarticulated, yet mutually understood, acceptable outcome is illustrated in this snapshot of a bal sabha in Amloi:

A teacher, showing the form to be filled, explained: ‘We have to fill the details of how many men, women and children are present, and amongst them how many are active and passive participants’. When the bal sabha started in the village, no women were present. A teacher announced, ‘Please call women, their presence is mandatory’ and went around a few households to invite them. A student went to a nearby house where people were gathered for a wedding. The groom, in his ceremonial attire, and other relatives attending, duly arrived to attend the bal sabha. The teacher gave a speech on the importance of education, students sang poems and narrated stories, and then songs were played on the loudspeaker in the groom’s household, to which children danced. Meanwhile, another teacher recorded thumbprints and signatures of men and women who attended the bal sabha, including ours.

For teachers, their own performance in enabling the school to record achievement of the mandated attendance was at least as dominant a concern as the actual content of the bal sabha. Accountability, in this perspective, is orientated towards the state, their duty as teachers interpreted as keeping a record of the event and ensuring that participation meets guidelines in terms not only of numbers and representation (gender) but also levels of individuals’ engagement (active/passive), rather than the effectiveness of the event in terms of communicating messages about education. Amloi’s villagers, familiar with the expectations of the school about their role in signing paperwork, were compliant despite being in festive mode.

Connections in LFPSs

Our second vignette is of Vivek Public School, a family-owned LFPS in Patna District. While LFPSs have expanded access to basic education across India (Muralidharan and Kremer Citation2006), their presence has stimulated ‘parental abandonment of government schools’ and a shrinkage of state provision (Kingdon Citation2020), rather than exerting market-choice pressures to improve performance of government schools and greater overall systemic accountability for student learning (Yan Citation2019). Private schools are not required by law to hold SMC meetings, and do not need to hold enrolment drives, but they are legally required to hold PTMs and have an obvious imperative to demonstrate to fee-paying parents that their investment is justified.

Vivek school illustrates ostensibly more effort to create school–family connections than we saw in Madhopur, with a strong emphasis on homework and use of a daily diary to communicate. While considerable effort goes into sustaining connection by these means, the performance of accountability here is strikingly similar to that found in Madhopur and across government schools.

Vivek Public School serves Vivek village and some 45 other villages. It has a nursery and Grades 1–7, serving about 550 children, and 10 teachers, none of whom has the teaching qualification stipulated by the RtE Act. It charges monthly fees of Rs. 180–250. The mother of two students says the school is ‘nothing great but at least it’s better than government schools’.

Much emphasis is placed on homework. When two Grade 5 boys cannot not recite the set poem, the teacher complains, ‘You don’t study at home’. She walks round checking students’ books, asking ‘Have you shown your homework?’ and, striking an unresponsive child, says: ‘From today if you do not [do the homework], I will throw you out of class’. Teachers expect parents to support children with their homework. For Mrityunjay, from an educated, landowning family of a privileged caste, this form of connection is possible. But, as his father tells us, ‘We are educated families so we help our children in learning – but what about those children who don’t get help from parents, they get trapped’. Ajju, a girl from a ‘middle caste’ family, gets up at 4 am to do household chores so her mother can tend the family buffalo; her father is a manual labourer. Ajju’s mother asks us, ‘How can we help with homework? We are not literate. She does what she can, on her own’.

Homework is facilitated by the daily home-school diary. Teachers know that parents often cannot read or write, but since ‘parents and teachers together have the responsibility of keeping a student in check’, the diary facilitates connection. Teachers dictate homework tasks that students – even in Grade 1 – write in their diaries. The parent is expected to sign underneath the daily notice in the diary; the teacher countersigns, the following day. Chandni’s mother tells us she has a vague idea about the diary notices, and gives her thumbprint whenever required. As she can’t read herself, she sometimes gets her daughter to read it out to her, but mostly just signs.

Vivek school no longer holds PTMs. School teachers tell us, ‘We tried contacting parents. The first time we organised a PTM, you would not believe, no parent turned up for it. How stupid that felt, we can hardly explain. At most 10 out of 100 parents are interested in knowing their child’s progress’. Teachers also say ‘it is not possible to meet all the parents, we can meet only those who live nearby’ and ‘if we start to meet guardians one by one, when would we teach?’. There is a register with parents’ phone numbers: when a call comes, it is to summon a parent to school (usually, reflecting gendered norms, the father), and it was rare to find communication initiated by parents.

The daily diary

The daily diary is widely used in LFPSs. In Uday school, an urban LFPS in Udaipur, Samreen’s father explained: ‘Parents are expected to check and sign every day. Also, teachers write complaints, like the child not doing the homework, or not studying well’. While considerable teacher labour goes into communicating via the diary, there is no expectation that this is reciprocal. An Uday teacher explains:

We write in Hindi in the diary as parents cannot read English. We write all kinds of communication about homework, meetings, functions, fees … We fill the diary every day. Parents are expected to check and sign it. If they have any response, some of them (those who can write), respond in the diary only.

While the diary is evidence of teacher effort, it is a written communication that is perfunctory for all parents. Parents who cannot read or write sign off without comprehension (unless mediated); those who can read also just sign off. In the setting of LFPSs, the diary’s impersonal, inaccessible nature makes it a connection that perpetuates social distance – while further reinforcing the hierarchy of the educated/uneducated – and serves as a substitute for a more dialogic and contextually appropriate mode of communication. But for teachers and the school management, this written record of their ‘communications’ with parents is important because it symbolises their fulfilment of the formal obligations required by the 2009 RtE Act. Diary communications, then, are shorn of pedagogical meaning but constitute a mutual performance of bureaucratic accountability.

Parent–teacher meetings

The RtE Act also pursues connections by requiring a teacher, inter alia, to ‘hold regular meetings with parents and guardians’ (GoI Citation2009, 10 [24/1/e]): default may incur disciplinary action [24/2]. Since this mandate applies to all qualified teachers [23], both government and private schools must hold PTMs, to ‘apprise [parents and guardians] about the regularity in attendance, ability to learn, progress made in learning and any other relevant information about the child’ [23].

Across our sample, PTMs, held in the school, are the most common form of school–family connection. But although PTMs are supposed to be conducted regularly, their frequency varies. In government schools, the annual academic calendar lists two to four PTM dates. Some private schools hold PTMs more often, informing parents about dates via a note in the diary or in the child’s notebook, or an announcement on the noticeboard. The focus of interaction in PTMs tends to differ by school type, but not such that learning is in focus.

In government schools and NGO-run NFEs (as our third vignette will show), the key topics are children’s regularity in attendance and the importance of education. For example, the mother of Nandkishore (Grade 5 student, Amloi rural government school) goes to meetings at the school, and reported that ‘the teacher asks us to send children regularly and talks about the importance of education’. In our sample, in government schools, and with most teachers commuting to work, social distance is high. In PTMs, teachers rehearse their own priority concerns: attributing irregular attendance to parents’ poor awareness of the importance of education, they emphasise its importance and the need for regular attendance. Other than conveying examination scores, there is no discussion of students’ progress in learning or what parents might do to support it.

It was common, as the Madhopur vignette illustrates, for mothers of children in rural government schools to say that domestic and livelihood-related demands means they do not have time to attend PTMs. Archana’s (Grade 1 student, Amloi rural government school) mother exemplifies what many told us: ‘I went to the school only to enrol my child. I do not get time to attend meetings. I have to do the household chores and work in the fields’. PTMs are held in schools rather than homes, ie in a public domain where adult female participation is regulated and constrained by gendered norms of propriety (cf. Jha et al. Citation2014). In rural government school settings, parents (particularly mothers) did not know the teachers and were hesitant to talk to them. Nandkishore’s mother, who attends PTMs when called, alludes to social as well as physical distance when she says:

[The teachers] come from Gola in the morning and go back in the evening. They do not stay after school hours. They are from other far-off places and live in Gola. I knew the previous teacher. He was from the village.

In LFPSs, where parents pay fees and ensure that their child attends regularly, PTM discussion focuses on fees, examination scores and discipline. Neha, a teacher at Badhoi (Udaipur rural LFPS), explains: ‘We discuss the child’s studies, and whether parents are monitoring their child’s studies at home or not. We ask them to pay attention to students at home’. The father of a Grade 1 female student of Motherland, an urban LFPS in Udaipur, provides a parental perspective: ‘I visit the school whenever the teacher calls me to pay fees or come for a meeting. We tell teachers to pay attention to our children’. Nazia, mother of a Grade 1 Motherland student, when asked what happens in the PTMs, says:

Nothing much. The teacher informs me how many marks my daughter has scored in different subjects and asks me to sign on the marksheet. I can neither read the score nor understand what is written there. I listen to the teacher and sign the marksheet.

In LFPSs, the parental capacity to pay fees, and their entitlement to service in exchange, confer a status that is denied to parents of students attending government schools. While this might reduce the social distance between the school and parents, or render it less significant, in LFPSs parental engagement is generally transactional and – as in government schools – driven by the school rather than by parents. Parents routinely visit the school to pay fees, and attend PTMs if called by school authorities; but these connections are not frequent. In Pratap Sangha school, a Grade 1 child’s mother reports that she visits the school whenever the principal calls her, mostly to pay fees or pick her daughter up when she is not well; otherwise, ‘I attend annual functions on Independence Day and Republic Day. No meetings happen in school other than this’. In the same school, a Grade 4 student’s mother said much the same: ‘Teachers do not call us. We go to school only to submit fees and for functions on Republic day and Independence Day’. But she added, ‘If we do not attend the functions, they scold and punish the children the next day’.

Connections in NGO-managed schools (NFEs)

Our third vignette is of Madhopur-Bhilwara, an NFE in rural Udaipur’s Adivasi region and in the vicinity of the Madhopur government school presented in the first vignette. Here, the spatial norms of the ‘neighbourhood’ school envisaged by the RtE Act (GoI Citation2009) do not fit the terrain and habitation patterns of Adivasi populations, and are unable to ensure that government provision is accessible (Veerbhadranaika et al. Citation2012). Adivasi children, especially girls, have high rates of school dropout, particularly in the transition from Grade 1 to Grade 2, and low rates of transition to higher educational levels (Veerbhadranaika et al. Citation2012).

The Madhopur-Bhilwara NFE is one of 150 NFEs in the region, run by a local NGO, which enrol children aged 6–10 in hamlets where government schools are not accessible, or formal school enrolment is low. Teachers are local, selected and trained by the NGO. The language of instruction is formally Hindi, but teachers often use Mewari, the children’s home language. ‘Classes’ are flexible about how long a child needs before moving to the next level, and teachers incorporate play into their pedagogy. Compared with the previous two vignettes and types of schooling they illustrate, these NFEs might be expected to have close connections with communities and families, with strong alignment in actions and expectations to facilitate a child’s learning, mediated by the NGO. Yet here too we see glimpses of bureaucratised accountability relations in connections.

Madhopur-Bhilwara hamlet comprises 80 households of the same Adivasi community. Women do agricultural labour, graze domestic animals and fetch firewood and fodder, typically helped by their daughters. Men often migrate in summer to augment their cash income. About 10 children attend a government school three kilometres away, which provides free midday meals and scholarship incentives. Most families prefer the NFE: they know the teachers, respect the NGO, and several previously studied there themselves. Over 50 students are enrolled, yet they are often seen out grazing animals, doing household chores, caring for siblings and playing. The NFE has one classroom: students work in three ‘levels’, taught by one male and one female teacher who both have a post-secondary qualification. Neither teacher is Adivasi, but the community around the NFE is close-knit and the teachers know every family.

Formal engagement between NFE and parents/community is limited to paying the annual fee (Rs. 200), attending meetings and monitoring attendance. Teachers are paid for the day only if at least 10 students are present. The Sarpanch tell us, ‘We check if teachers are coming to school on time or not. If not, we ask them why they didn’t come on time. I tell them, “You get salaries, and if you are not teaching children then what are you doing?”’

About half the children attend erratically. Kesulal’s mother says: ‘I cannot leave my work and keep checking whether he went to school or not. He goes to the far hills to play. I cannot leave my work and my infant to go and call him. I sometimes do tell him to go to school. But he does not listen’. The Sarpanch says, ‘Students do not go regularly, this is because of the carelessness of parents’, and worries: ‘How will the students pass like this? They won’t [be able to] continue their education’. One of the teachers says children ‘come here because of the bond that we share … parents ask their children to go to school, but in many houses, there is nobody to guide or supervise them’. Teachers often visit students’ homes to follow up, which elicits promises to send children, but only temporary improvement.

Teachers do not give homework, recognising that most parents are in positions similar to Kesulal’s mother, who explains: ‘I am illiterate and do household chores from morning to evening. His father goes to Gola from morning to evening. We do not have time to sit with him or supervise him’. Formal feedback on children’s progress is through communicating results from mid- and end-term exams.

Participatory attendance monitoring

In the NFEs, PTMs aim to grow awareness about education and regular attendance. Engagement with parents typically takes the form explained by an NFE teacher:

We have one meeting at the start of each academic year [in July] where we discuss with parents how fees collected are used to buy school uniforms, bags and sweaters. Then, we conduct meetings every two months where we call parents to discuss the importance of sending their children regularly. The students perform a dance or skit, give speeches and recite poems. When parents see their children do this, they feel happy and know that students are learning at the school.

Once the annual fee is paid, the predominant focus of school-family/community interactions is regular student attendance, as it is in government provision; and reporting of student results, found in both government and LFPSs. As the vignette suggests, attendance of teachers is itself a concern (as in government schools), so the NGO has given the community a transparent role in monitoring teacher presence, requiring four photos to be taken daily to evidence presence (of teachers and children), to be signed off by the voluntary Village Development Committee facilitated by the NGO, in order for a teacher’s salary to be released. While the government system functions through top-down monitoring (Aiyar and Bhattacharya Citation2016), the NFE evidences community monitoring through NGO presence. Importantly, despite the closer teacher–parent relations here, this broad field does not encourage consideration of how connections can nurture parental capabilities to talk about individual students’ learning.

Survey findings

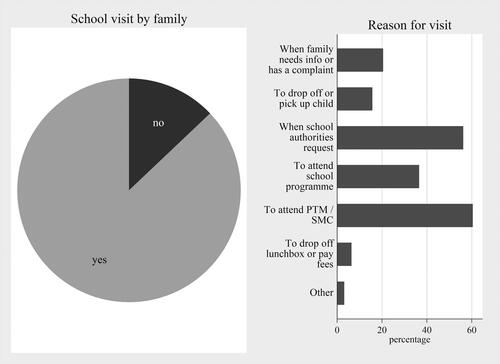

We conclude this empirical discussion of the field with insights from the representative quantitative data. In respect of school visits, (left graph) shows that about a tenth of parents never visit their child’s school at all. For the large majority who do visit (right graph), over half go for PTMs and over half also visit the school when called by school authorities (often in relation to fees for private schools and irregular attendance in government schools). Further, a third go when invited for formal school events such as Independence and Republic Day celebrations. Note that all the higher-frequency interactions in are initiated by the school, not parents.

Figure 1. Purpose of school visit by family.

Note: The pie chart summarises survey data from 402 families averaged across Udaipur and Patna. The bar chart is for the 350 families who report that they visit their child’s school (averaged across Udaipur and Patna); the sum of bar percentages exceeds 100 as the survey question allowed multiple responses.Footnote3

Of the 11% that do not visit school at all, further probing (not presented in ) elicited that about 30% said nobody from the school had asked them to visit, 50% said that they could not visit because of work pressures; and 20% felt intimidated because they were not literate. This suggests that parents do not visit the school for reasons that reflect (intersecting) disadvantaged structural position(s) (work, non-literacy), and/or an expectation that the school would initiate any interaction, rather than seeing themselves in a proactive role. Pro-activity is relatively rare even among the large majority who do visit the school: only a fifth of parents initiate a school visit themselves, whether to seek information, understand activities or complain. Further, the findings presented in do not vary substantively according to whether the school is urban or rural, or government or LFPS.

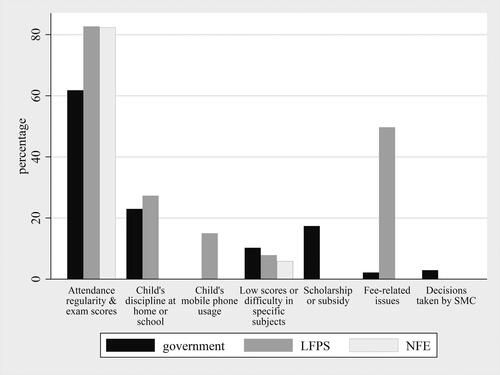

Although in many instances parents visit schools purely for administrative and related reasons (as shown in ), our survey found that about half the parents (54%) do have discussions on matters connected with their child. presents data on what is discussed by this subset of parents. The content of discussions prominently features: exam scores (private schools); student attendance (government schools); fee-related matters (private schools); and child discipline. Discussions around student learning – understanding why exam scores are what they are, whether the child faces difficulties in particular subjects and why – are strikingly rare: less than a tenth of parents reported having such discussions during school visits. In this small minority, further, discussion was guided by a student scoring poorly in a particular subject and teachers/parents asking each other to focus specifically on that subject. One parent requested the researcher: ‘The teacher tells us he is weak in English and maths. But we don’t know what that means – you explain’.

Figure 2. Topics of discussion between school and family.

Note: The bar chart represents the 193 families who reported that they discuss matters connected with their child (averaged across Udaipur and Patna); the sum of bar percentages exceeds 100 as the survey question allowed multiple responses. Missing bars indicate 0 respondents for that option (for instance, child’s mobile phone usage in government schools or NFEs).

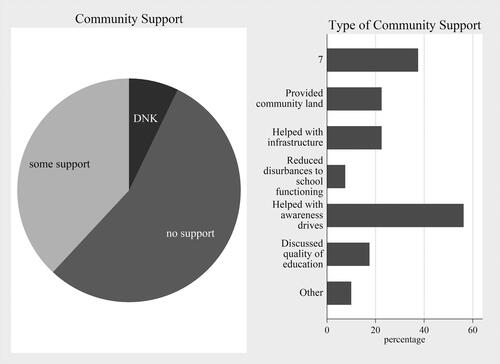

Community leaders (those formally designated, such as the Sarpanch, and others such as caste leaders) were asked ‘What support does the community provide to the school?’ summarises answers to this question. We found there was no support at all for LFPSs. For other schools (government schools and NFEs), the left graph indicates that a small subset (7%) did not know – which is itself telling – and over half of the respondents did not provide any support. Only a little over a third (38%) said that communities provide some support. The right graph summarises their responses: less than a quarter mentioned providing land, and similarly less than a quarter said that the community provided help with building construction (overall, 38% mentioned at least one of the two, land or buildings); and over half mentioned support through awareness drives to increase school enrolment. Importantly, even among the community leaders who said that communities provided some support, less than a fifth mentioned discussion of the quality of education. The vast majority of community leaders said they do not see student learning as within their ‘competence’ or ‘jurisdiction’ – a language of explanation that directly evokes a bureaucratised perspective.

Figure 3. Community support for government schools and NFEs.

Note: The pie chart summarises survey data from 70 community leaders in the location of the schools studied (averaged across Udaipur and Patna); DNK stands for ‘do not know’. The data presented are for government schools and NFEs alone; in all cases, LFPSs received no support. The bar chart represents the subset of respondents who said that the community provides ‘some support’ (averaged across Udaipur and Patna); the sum of bar percentages exceeds 100 as the survey question allowed multiple responses.

Dull performativity and bureaucratised school–family–community relations

The school–family/community connections in the field are redolent of a dull performativity that is a far cry from the active participation and ‘vibrancy’ to which India’s 2020 NEP aspires (GoI Citation2020). Despite the volume and variety of school-driven communications aiming to engender the connections that policy discourses envisage, these are largely concerned with news about school events, attendance and monitoring, with some discussion of test results serving as a proxy for learning. From the school side, the concern is about accounting, that is, about numerically countable matters (student attendance, the number and attendance of PTMs, ‘cultural events’, and fees). Activity is monitored by enumeration, and reported up the hierarchy. These are formally mandated requirements of the 2009 RtE Act, executed in a bureaucratic space where principals, teachers and administrators can be upbraided and face penalties if the numbers they present – shorn of interpretive context and meaning – are unsatisfactory.

Although school–family communications and relations are dull and performative, they clearly involve labour on the part of both schools and families. Yet the labour of communication is focused on ‘inputs’ and ‘outputs’ (attendance, fees, holding events and so on), not processes and ‘outcomes’. We repeatedly observed that outcomes are narrowed to numerical marks that are reported in PTMs and diaries – particularly in LFPSs compared to government schools or NFEs – but without any attempt by either school or family to understand what learning the marks may represent. In fact, marks are better interpreted as ‘outputs’ rather than meaningful ‘learning outcomes’. The bureaucratisation of accountability appropriates the language of programme design, creating an input/output focus: learning outcomes do not disappear but are made static, narrow, acontextual and countable. Labour is not devoted to examining or reflecting on the processes through which communications may possibly transmute (or not) to enhancing student learning. The connections that are created fail to communicate how children are doing, their learning processes and progress and challenges. They do not extend to a forward-looking contextualised discussion of what the school and the family can do for a student – or, similarly, discussion of what the school and the community can do for the student body as a whole.

The parent as ‘governmentable subject’ (an unwitting agent in the processes that reinforce the bureaucratisation of accountability) is typified by perhaps the only (ostensibly) ‘outcome’-related question that some parents may ask: ‘Kitne number aaye?’ (‘What score [did my child get]?’). For many parents across our sample, structural inequalities reinforce parental quiescence – and while the socially mediated character of bureaucratic accountability is then particularly visible, it merely reinforces existing trends. A signature is an apt metaphor for this ‘dull performativity’; it signals the thorough bureaucratisation of relations driven by record-keeping and ticking of boxes. Schools and families merely go through the motions; and this, we surmise, is because they are ‘on the same side’, with little productive tension to move them along. By ‘same side’ we do not mean solidarity and convergence of views, but rather performativity in mandated activities with little demurral or questioning – and none when it comes to the question of student learning. Formal-turned-formalistic communication and accountability relations characterise not only the activities organised by government schools but also schools outside the direct control of government, particularly LFPSs, but even NGO-run schools to an extent. That is, bureaucratised accountability relations encompass the entire space of schooling accessible to the less privileged strata of Indian society.

The prevalence of such relations supports our argument that bureaucratised accountability is systemic, and not restricted to government schools. These relations constitute, and are constituted by, a culture of bureaucratic performativity that strips school–parent–community connections of learning-orientated content. Even if we ignore the silence on learning progress in mathematics, language, and so on, the absence of meaningful relations around student learning is a tragedy for the ‘public good’ insofar as the community does not engage in school learning activities regarding social relations and democratic citizenship; and so, potential community contestation of the conditionalities of participation is also compromised. Bureaucratised accountability constitutes a ‘field’ where schooling reinforces the very patterns of social disadvantage that formal education could mitigate if interactions were orientated towards matters of pedagogy, learning and formative engagements.

The separation of the school from families and the community goes along with the aura of the school as a ‘technical space’ dealing in recondite information. Bureaucratisation enables and perpetuates this aura. This separation is intimidating for poor and uneducated parents (particularly mothers); and the casting of the school as a technical space makes it still more difficult for parents to inquire about what learning is happening. From a normative perspective, parents – especially those living lives of social and economic precarity – need to want, and have the confidence, to pierce the veil of bureaucratisation and technicality if they are to meaningfully engage with the school on matters of their children’s learning. The bureaucratised school–family/community relations of accountability in the field of education fulsomely discourage any such connection.

We have presented empirical data and critically discussed the hollowing out of formal mechanisms of school–family connection. Many ways exist to show the presence of SMCs and PTMs on paper, for instance, although those same SMCs and PTMs are not substantively bringing together schools and families in understanding children’s learning trajectories. Therefore, if data on the existence or mandated activities of these formal mechanisms are insufficient guides to assess the health of school-family connects, where may we turn? Although addressing this is beyond our scope here, process-oriented approaches may have a better fit than current decontextualised, indicator-oriented approaches. The methodological literature on process-tracing (Gerring and Thomas Citation2006) and backward mapping (Elmore Citation1985; Dyer Citation1999) offers useful possibilities; and more generally, especially in the context of policy interventions, we see much promise in the ‘realist evaluation’ approach developed by Ray Pawson (Pawson Citation2013) and others, and inspired by the critical realism of Roy Bhaskar. Focusing on ideas of context–mechanism–outcome critically examines pathways – in our case, pathways through which formal mechanisms get hollowed out, and possibly also other pathways through which connects and disconnects occur.

This paper has identified and presented aspects of what we argue is a ‘field’ of bureaucratised accountability relations in India. We close with the suggestion that this case has wider resonance. Our argument that the ‘field’ we have identified here is socially constituted in ways that constrain meaningful discussion of learning across the schools has important implications for accountability-focused education reforms in India, the South Asia region, and beyond.

Ethical approval

This project received ethical approval from the University of Leeds in July 2018 (ref no. AREA 17-151).

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to all members of our research teams in Rajasthan and Bihar for their many and various contributions (details at https://raise.leeds.ac.uk/): to Rahul Mukhopadyay and Priyanka Saxena for their leadership in the field; to Arathi Sriprakash for commenting on an early version; and to Shaurya Gupta and Jyoti Dey who, along with Indira Patil, wrote first versions of the vignettes included here. An early version of this paper was presented at the annual conference of the Comparative & International Education Society (CIES) in April 2021.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Caroline Dyer

Caroline Dyer ([email protected]) is Professor of Education in International Development at the University of Leeds, UK. She has interests in education policy, inclusion and marginalisation, particularly for mobile pastoralist communities. Recent co-authored publications critique the sedentary ontology of education systems (in Compare, doi: 10.1080/03057925.2021.1907175) and the social contract of India’s right to education (in Development and Change, doi: 10.1111/dech.12715).

Suraj Jacob

Suraj Jacob ([email protected]) is with the Azim Premji University (Bengaluru, India) and has interests in development and governance. He previously served as chief executive of Vidya Bhawan, an education NGO in Rajasthan, India. His recent publications include the co-authored book Governing Locally: Institutions, Policies and Implementation in Indian Cities (Cambridge University Press, 2021).

Indira Patil

Indira Patil ([email protected]) works with the International Initiative for Impact Evaluation (3ie) and is interested in public policy and governance. She previously worked with Vidya Bhawan as a RAISE project researcher, and has recently contributed to an article on teacher accountability to Ideas for India https://www.ideasforindia.in/profile/indira1.html.

Preeti Mishra

Preeti Mishra ([email protected]) currently heads the Education Resource Centre of Vidya Bhawan. Her areas of interest are large-scale student assessment, and teacher professional development and management.

Notes

1 The Covid pandemic, which has led to widespread and extended school closures across the region, has interrupted this trend, but it is too early to predict its longer term impacts.

2 The Sarva Shisksha Abhiyan (universal education campaign) is now amalgamated into the Samagra Shiksha Abhiyan (https://samagra.education.gov.in/features.html).

3 The reported figures are averages across Udaipur and Patna, giving equal representation to the two field sites as the purpose here is not to explore differences in family–school connections across locations.

Bibliography

- Aiyar, Y., and S. Bhattacharya. 2016. “The Post Office Paradox.” Economic & Political Weekly 51 (11): 61–69.

- Aiyar, Y., B. Posani, A. Patnaik, and M. Devasher. 2009. “Institutionalizing Social Accountability: Considerations for Policy.” Accountability Initiative Policy Paper. https://pria-academy.org/pdf/2.36_1255255017.pdf

- Apple, M. 2004. “Schooling, Markets and an Audit Culture.” Educational Policy 18 (4): 614–621. doi:10.1177/0895904804266642.

- Annual Status of Education Report. 2019. The Annual Survey of Education Report (Rural) 2018-19. New Delhi: Pratham/ASER Centre.

- Asadullah, M., M. A. Alim, and M. Hossain. 2019. “Enrolling Girls without Learning: Evidence from Public Schools in Afghanistan.” Development Policy Review 37 (4): 486–503. doi:10.1111/dpr.12354.

- Asadullah, M., and N. Chaudhury. 2015. “The Dissonance between Schooling and Learning: Evidence from Rural Bangladesh.” Comparative Education Review 59 (3): 447–472. doi:10.1086/681929.

- Asadullah, M., A. Savoia, and K. Sen. 2020. “Will South Asia Achieve the Sustainable Development Goals by 2030? Learning from the MDGs Experience.” Social Indicators Research 152 (1): 165–189. doi:10.1007/s11205-020-02423-7.

- Asim, S., R. Chase, A. Dar, and A. Schmillen. 2017. Improving Learning Outcomes in South Asia: Findings from a Decade of Impact Evaluations. Oxford University Press/World Bank. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/30140.

- Banerjee, A., and E. Duflo. 2008. “Mandated Empowerment: Handing Antipoverty Policy Back to the Poor?” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1136: 333–341. doi:10.1196/annals.1425.019.

- Bourdieu, P., and L. Wacquant. 1992. An Invitation to Reflexive Sociology. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Bruns, B., D. Filmer, and H. Patrinos. 2011. Making Schools Work: New Evidence on Accountability Reforms. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Carr-Hill, R., C. Rolleston, R. Schendel, and H. Waddington. 2018. “The Effectiveness of School-Based Decision Making in Improving Educational Outcomes: A Systematic Review.” Journal of Development Effectiveness 10 (1): 61–94. doi:10.1080/19439342.2018.1440250.

- Cody, F. 2009. “Inscribing Subjects to Citizenship: Petitions, Literary Activism, and the Performativity of Signature in Rural Tamilnadu.” Cultural Anthropology 24 (3): 347–380. doi:10.1111/j.1548-1360.2009.01035.x.

- Corbridge, S., G. Williams, M. Srivastava, and R. Véron. 2005. Seeing the State: Governance and Governmentality in India. Vol. 10. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Dyer, C. 1999. “Researching the Implementation of Educational Policy: A Backward Mapping Approach.” Comparative Education 35 (1): 45–61. doi:10.1080/03050069928062.

- Dyer, C., and V. Rajan. 2021. “Left behind? Internally Migrating Children and the Ontological Crisis of Formal Education Systems in South Asia.” Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 1–18. doi:10.1080/03057925.2021.1907175.

- Dyer, C., A. Spriprakash, S. Jacob, and N. Thomas. 2022. “The Social Contract and India’s Right to Education.” Development and Change. doi:10.1111/dech.12715.

- Elmore, R. F. 1985. “Forward and Backward Mapping: Reversible Logic in the Analysis of Public Policy.” In Policy Implementation in Federal and Unitary Systems, edited by K. Hanf and T. Toonen. Dordrecht: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-94-009-5089-4_4.

- Evans, D. K., and A. Popova. 2016. “What Really Works to Improve Learning in Developing Countries? An Analysis of Divergent Findings in Systematic Reviews.” The World Bank Research Observer 31 (2): 242–270. doi:10.1093/wbro/lkw004.

- Foucault, M. 2010. The Birth of Biopolitics: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1978–1979. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Gerring, J., and C. Thomas. 2006. “Internal Validity: Process Tracing.” In Case Study Research: Principles and Practices, edited by J. Gerring. 172–186. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Government of India. 1999. “Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan. Framework for Implementation.” Ministry of Human Resource Development, Government of India. http://www.educationforallinindia.com/SSA1.htm

- Government of India. 2009. “The Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education Act, 2009.” New Delhi: Ministry of Law and Justice, Government of India. https://legislative.gov.in/sites/default/files/The%20Right%20of%20Children%20to%20Free%20and%20Compulsory%20Education%20Act,%202009.pdf

- Government of India. 2017. “Elementary Education in India: Where Do We Stand?” In DISE State Report Cards 2016-17. New Delhi: Government of India, MHRD. http://udise.in/Downloads/Elementary-STRC-2016-17/All-India.pdf

- Government of India. 2020. National Education Policy 2020. New Delhi: Ministry of Human Resource Development, Government of India. https://www.education.gov.in/sites/upload_files/mhrd/files/NEP_Final_English_0.pdf

- Govinda, R., and R. Diwan, eds. 2003. Community Participation and Empowerment in Primary Education. New Delhi: Sage Publications.

- Jha, J., N. Ghatak, S. Chandrasekharan, S. Veigas, and G. Prasad. 2014. “A Study on Community Engagement with Schools in Five States.” https://cbps.in/wp-content/uploads/SMC_SCF_5states.pdf

- Kingdon, G. 2020. “The Private Schooling Phenomenon in India: A Review.” The Journal of Development Studies 56 (10): 1795–1817. doi:10.1080/00220388.2020.1715943.

- Kumar, K. 2008. “Partners in Education?” Economic and Political Weekly 43 (3): 8–11. doi:10.2307/40276915.

- Maitrayee, R., and A. Sriprakash. 2018. “The Governance of Families in India: Education, Rights and Responsibility.” Comparative Education 54 (3): 352–369.

- Mansuri, G., and V. Rao. 2012. Localizing Development: Does Participation Work? Washington, DC: World Bank. https://www.worldbank.org/en/research/publication/localizing-development-does-participation-work

- Mbiti, I. 2016. “The Need for Accountability in Education in Developing Countries.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 30 (3): 109–132. doi:10.1257/jep.30.3.109.

- Muralidharan, K., and M. Kremer., 2006. “Public and Private Schools in Rural India.” In School Choice International: Exploring Public-Private Partnerships, edited by F. Chakrakbarti and P. Peterson. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- NIEPA. 2017. Elementary Education in India: Where Do We Stand? State Report Cards 2016–17. New Delhi: National Institute of Educational Planning and Administration.

- Pawson, R. 2013. The Science of Evaluation: A Realist Manifesto. London: Sage Publications.

- Pritchett, L. 2013. The Rebirth of Education: Schooling Ain’t Learning. Center for Global Development/Brookings Institution Press. https://www.cgdev.org/sites/default/files/rebirth-education-introduction_0.pdf

- Pritchett, L. 2015. “Creating Education Systems Coherent for Learning Outcomes: Making the Transition from Schooling to Learning.” RISE-WP-15/005. https://riseprogramme.org/sites/default/files/2020-11/RISE_WP-005_Pritchett.pdf

- Smith, W., and A. Benavot. 2019. “Improving Accountability in Education: The Importance of Structured Democratic Voice.” Asia Pacific Education Review 20 (2): 193–205. doi:10.1007/s12564-019-09599-9.

- UNESCO. 2017. Accountability in Education: Meeting Our Commitments. Global Education Monitoring Report, 2017/18. Paris: UNESCO.

- Veerbhadranaika, P., R. Kumaran, S. Tukedo, and A. Vasavi. 2012. The Education Question’ from the Perspective of Adivasis: Conditions, Policies, and Structures. Bangalore, India: National Institute for the Advanced Studies.

- World Bank. 2004. “Making Services Work for Poor People: World Development Report 2004.” https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/5986/WDR%202004%20-%20English.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- World Bank. 2018. “Learning to Realize Education’s Promise: World Development Report 2018.” https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/wdr2018

- Yan, Y. 2019. “Making Accountability Work in Basic Education: Reforms, Challenges and the Role of the Government.” Policy Design and Practice 2 (1): 90–102. doi:10.1080/25741292.2019.1580131.