Abstract

The shift in global policymaking from the Group of Seven (G7) to the Group of Twenty (G20) is widely seen to reflect the rise to power of emerging markets in the South. It begs the question, though, whether the G20 has the right membership to legitimately govern the global economy. This paper applies a novel framework linking rightful membership to global governance institutions’ roles to address this question. A longitudinal analysis of (1) financial and economic indicators of G-group members; (2) their global ranking on these indicators; and (3) the position of G-group members in technical forums of financial governance demonstrates that the shift to the G20 was necessary to maintain rightful membership given the declining share of G7 members in the global economy. However, rightful membership as a source of legitimacy varies across G-group roles and diffuses across roles and across global governance institutions. These new insights demonstrate the added value of conceptualising rightful membership in relation to different roles of global governance institutions. The analytical framework proposed in this paper allows for better insights into the legitimation strategies and public legitimacy perceptions of global governance institutions, and points to interesting new hypotheses with respect to the legitimacy of global governance institutions.

Introduction

The 2008 global financial crisis established the Group of Twenty (G20) as the self-designated ‘premier forum for international economic cooperation’ (G20 Citation2009, 3). Western dominance, as epitomised by the Group of Seven (G7), seems to have given way to the rising powers of the Global South. However, the selective nature and informal membership criteria of the G20 lead to questions with respect to its representativeness.Footnote1 How can the G20 legitimately claim to be the premier forum of international cooperation when it has such a selective membership? And is the composition of its membership defensible empirically? This paper makes the case for rightful membership as a conceptual tool to analyse these questions (Slaughter Citation2013, Citation2020). It develops a novel framework of rightful membership that offers insights into the varying dynamics of global governance institutions’ legitimacy in relation to their different roles. In doing so, the paper makes an original contribution to the existing literature on legitimacy and global governance (Tallberg, Bäckstrand, and Scholte Citation2018; Tallberg and Zürn Citation2019).

The concept of rightful membership has particular applications in assessments of the legitimacy of global governance institutions with a selective membership, such as the G-groups. The overarching question guiding this paper is whether the G-groups conform with the normative standard of rightful membership as a source of legitimacy. After developing an amended and refined framework of rightful membership, the second part of the paper provides an empirical evaluation of the performance and record of the G7 and G20 on rightful membership criteria derived from the roles G-groups play in global governance. Three empirical questions guide the analysis: (1) how have the G-group members developed in terms of financial and economic indicators; (2) how has the ranking of the G-group membership developed on these indicators; and (3) how has the position of the G-group membership in technical forums of financial governance developed? These questions are addressed through a comparative, longitudinal analysis of G-group members. Surprisingly, the current literature lacks a systematic analysis of the economic and financial underpinnings of G-group membership. There is literature on individual countries (Cooper Citation2013; Kirton Citation2016; Downie Citation2017) and literature providing snapshots of the G-groups (G20 Citation2008b; Cooper Citation2010; Kahler Citation2013), but no longitudinal analysis of full G-group memberships in relation to different G-group roles. This paper will fill that gap with an empirical analysis that provides the building blocks for an assessment of the legitimacy of G-groups in terms of rightful membership.

Legitimacy denotes whether a global governance institution is perceived as having the right to govern, in the sense of the right to conduct governance (Reus-Smit Citation2007, 158; see also Hurd Citation1999, 381; Buchanan and Keohane Citation2006, 405). In other words, subjects consider the global governance institution to have normative qualities that provide it with legitimacy (Agné Citation2018, 29). This paper makes two main claims with respect to the qualities that confer legitimacy to global governance institutions. First, I will argue that rightful membership (ie ‘whether the relevant actors are included’ (Slaughter Citation2020, 9)) offers a useful analytical framework to understand the variegated dynamics of legitimacy when it is linked to the roles of global governance institutions. Analytically distinguishing rightful membership based on different roles enables us to refine the qualities on which global governance institutions are judged, with different roles pointing to different membership criteria. Applied to the G-groups, the framework shows that the G20, and earlier the G7, indeed can lay claim to rightful membership to fulfil different G-group roles in global economic governance. The aggregate membership dominates economic and financial indicators, and holds controlling stakes in technical forums. In addition, no individual country can make a strong claim to membership over current members based on these indicators. This contrasts with some of the starker denunciations of the G-groups’ legitimacy (Åslund Citation2009).

Second, I will argue that rightful membership as a source of global governance institutions’ legitimacy diffuses and interacts across different G-group roles. The shift from the G7 to the G20 was most relevant in relation to the G-groups’ role in accommodating rising powers. The diminishing share of the G7 in the real economy allowed the selected members of the G20 to claim rightful membership. This subsequently reverberated through technical forums of governance, rather than the G20 membership being selected ex ante to fulfil the role of providing strategic guidance to these forums. In other words, a claim to rightful membership in one role led to accommodation of the G20 in its role as orchestrator of technical forums so that it could claim rightful membership in that role as well. These variegated legitimacy dynamics across different G-group roles underscore the argument that the granular framework of rightful membership as a source of legitimacy developed in this paper offers analytical benefits.

The arguments developed here have significant implications for the wider literature on global governance and legitimacy. First, the granular framework developed in this paper can distinguish different dynamics of rightful membership in relation to different roles as a source of legitimacy in global governance, allowing for new insights. This is particularly relevant for global governance institutions with selective membership, where the rightfulness of the members is foundational for claims to legitimacy. When applying this to the G-groups, it becomes evident that rightful membership diffuses from one role (the accommodation of rising powers warranting the shift from the G7 to the G20) to another (the role of orchestrating technical forums). In other words, the original framework of rightful membership used in this paper results in refined insights in input sources of global governance institutions’ legitimacy across different roles. Second, the framework provides additional leverage in longitudinal analysis linking changes in global governance institutions’ roles to changes in membership. With the rise of new powers in the Global South, the role of G-groups as accommodators of rising powers became more prominent, warranting the shift from the G7 to the G20. Changes in roles in global governance institutions might thus lead to different compositions of the rightful membership, which need to be empirically investigated to understand the relevant publics’ perception of this quality as a source of legitimacy. In sum, the framework of rightful membership in relation to global governance institutions’ roles enables enhanced understanding of the variegated dynamics of legitimacy in global governance and has applications to a wide range of global governance institutions with a selective membership (Tallberg and Zürn Citation2019; Slaughter Citation2020).

The next section discusses the literature on legitimacy in global governance, rightful membership and G-group roles. In the third section, the background of the G7 and G20 in relation to the selection of their membership is discussed and the membership is analysed based on economic and financial indicators and position in technical forums. The fourth and final section concludes and discusses the implications of the analytical framework advocated here for the debate on the legitimacy of global governance institutions.

Global governance and legitimacy

The legitimacy challenges in global governance are well established (Coleman and Porter Citation2000; Kahler Citation2004; Brassett and Tsingou Citation2011). This section argues for rightful membership in relation to global governance institutions’ roles as an analytical lens to assess sources of legitimacy for global governance institutions. The second part of this section operationalises this framework of rightful membership with different understandings of G-group roles in global governance. Taken together, this develops a framework that allows for a granular analysis of G-group legitimacy dynamics in global governance.

Legitimacy of global governance institutions: rightful membership

This paper follows the conceptualisation of legitimacy introduced above: Legitimacy denotes whether a global governance institution is perceived as having the right to govern, in the sense of the right to conduct governance (Reus-Smit Citation2007, 158; see also Hurd Citation1999, 381; Buchanan and Keohane Citation2006, 405). Legitimacy is thus ascribed by society or relevant publics to institutions based on certain institutional qualities. The perceptions of legitimacy by the public are based on a normative yardstick that global governance institutions are assessed against (Bernstein Citation2011; Brassett and Tsingou Citation2011). In other words, subjects consider the global governance institution to have normative qualities that are sources of legitimacy (Agné Citation2018, 29). For example, a global governance institution might be deemed legitimate by members of the public because its decision-making procedures are democratic. Similarly, a global governance institution like the United Nations Security Council might use the diversity of its membership as a legitimation narrative, thus using normative standards to convince the public of its legitimacy (Hurd Citation2008; see also Gronau and Schmidtke Citation2016 on the Group of Eight (G8)).

I argue that the concept of rightful membership offers a useful normative yardstick to analyse the institutional qualities that can form a source of legitimacy. Rightful membership was initially used to designate states that were seen to have sufficient legitimacy to belong to the family of states. More specifically, it was used to exclude states such as Apartheid South Africa (Wight Citation1972). After the Cold War, a more general norm of ‘good governance’ developed as the criterion for acceptance as a rightful member of the international society of states (Clark Citation2007, chapter 10). In this use of the concept, rightful membership is determined by domestic political conditions of states. To apply the notion of rightful membership to global governance institutions, however, the concept needs to be adjusted to designate the conditions that makes these institutions rightful. In this use of rightful membership, the logic is reversed: It is not legitimate states that are rightful members of global governance institutions, but rather the rightful membership that confers legitimacy to these institutions (Hurd Citation2008, 204).

It is this latter conceptualisation that makes rightful membership a powerful analytical tool to apply to global governance institutions. It is the membership that forms the basis for legitimacy, especially when these institutions are selective. The restricted membership of G-groups, for example, has been criticised for excluding the ‘marginal majority of the G172’ (Payne Citation2010; Bishop and Payne Citation2021) and for circumventing more inclusive decision-making processes (Wade Citation2011; Vestergaard and Wade Citation2012). A more optimistic reading points out that the shift from the G7 to the G20 has increased legitimacy because it includes several rising powers – including some of the worlds’ most populous countries (Bergsten Citation2004; Beeson and Bell Citation2009). Since it has 12 more country members plus formal membership of the European Union, it is unmistakably true that the G20 is less exclusionary than the G7. There is also no doubt, however, that the G-groups remain exclusionary and therefore suffer from input legitimacy issues when they set the strategic direction of global governance. The rightfulness of the membership is thus the most pertinent issue relating to selective global governance institutions.

In the context of global governance institutions, Slaughter (Citation2020, 9) conceptualises rightful membership as ‘whether the relevant actors are included’ in decision-making. This standard, however, leaves open the question how the relevance of actors should be determined. It suggests there is only one notion of relevance, yet these notions might vary across roles and might change over time as well. Hurd (Citation2008), for example, demonstrates that multiple logics are used to assess relevance for membership of the United Nations Security Council. As Hurd acknowledges, these logics can suffer from a self-serving underpinning of countries that aim to become rightful members themselves. Moreover, the logics Hurd inductively distinguishes (representativeness, diversity, participation) do not address the multiple roles global governance institutions might play. For one role the diversity of the cultural make-up of the members might be more relevant, while for another regional diversity might be the more relevant quality. In addition, different publics might focus on different roles of global governance institutions and therefore have different notions of what the relevant members would be. A framework of rightful membership that takes into account the roles of the global governance institutions is therefore warranted.

The roles of global governance institutions might be deduced from their mandate, if they have one (Archer Citation2014, chapter 4). Such a deduction needs to be complemented by an analysis of their functioning in global governance as established in the literature, since the actual roles global governance institutions play might deviate from their original mandate (Barnett and Finnemore Citation1999; Best Citation2007). For each of the roles, the composition of the rightful membership might diverge. Linking the concept of rightful membership to notions of the roles global governance institutions play thus enables a granular analysis of legitimacy dynamics. Making this link explicit offers a number of benefits over the existing literature. Analytically distinguishing rightful membership based on different roles enables us to refine the normative standards against which global governance institutions are held, since different criteria are associated with different roles. In addition, this framework of rightful membership allows us to see whether changes in membership are also reflective of changes in role and vice versa; and whether rightful membership in one role influences or resonates with rightful membership in other roles. This enables a better understanding of legitimacy dynamics over time, where the roles of global governance institutions and, consequently, perceptions of their legitimacy might change.

The framework developed and tested in this paper provides a conceptual foundation that is able to contribute to the two main strands in the global governance and legitimacy literature: the normative and sociological legitimacy traditions Agné (Citation2018); see Buchanan and Keohane (Citation2006) for an elaboration of this canonical distinction of strands). In the normative tradition (Keohane Citation2011), a predetermined political-theoretical standard is applied to global governance institutions to assess their legitimacy (eg Woods Citation2010; Benson and Zürn Citation2019). This paper argues that rightful membership provides just such a standard, allowing the researcher to predetermine criteria for rightful membership in each role, and subsequently uses the framework to assess how the institution performs against this standard. In the sociological tradition (Tallberg and Zürn Citation2019), the focus is on perceptions of global governance institutions’ legitimacy among relevant publics (eg Guastaferro and Moschella Citation2012; Slaughter Citation2013; Chodor Citation2020). The granular and dynamic framework of rightful membership developed in this paper can be used to assess these perceptions of rightful membership of global governance institutions in different roles. This means that not only the perception of the relevant publics regarding legitimacy in the abstract of a global governance institution is examined, but also which roles the public perceives the institution is performing. This allows for refined insights into the public’s perceptions of legitimacy of global governance institutions as well as analysis of the relations between roles and legitimacy which are inferred by the public.

The next subsection demonstrates how this framework is operationalised in the context of the G-groups and discusses its analytical benefits for the analysis of sources of G-group legitimacy. As the G-groups do not have a formal mandate, their roles are deduced from the literature.

Operationalising the framework: G-group roles and rightful membership

Three main roles of G-groups emerge from the literature in international relations and international political economy. A realist strand of literature notes the role of G-groups as accommodating the main global powers. A second, functionalist strand of literature points to the inclusion of systemically relevant countries in global policymaking processes to address the challenges of financial globalisation. A third strand of literature emphasises the role of the G-groups in steering technical or executive global governance institutions. These three roles will be discussed below, after which the implications of these three perspectives for different operational indicators of rightful membership are discussed, as well as the leverage this framework offers in the analysis of G-groups.

The first role focuses on power politics and shifts in the global order (Kahler Citation2013; Newman and Zala Citation2018). Informal G-groups can easily incorporate rising powers, whilst their incorporation might be blocked in formal international organisations (Vabulas and Snidal Citation2013). The shift from the G7 to the G20, then, reflects the ability to co-opt or accommodate rising powers and prevent them from challenging the wider Western-led international order (Beeson and Bell Citation2009; Larson Citation2018). Kahler (Citation2013, 712) notes that

the impact of the large emerging economies on global governance is unlikely to be revolutionary. They do not differ from other powers, past and present, in wishing to extract as many benefits as possible from their engagement with the international order while giving up as little decision-making autonomy as possible.

This fits with the ‘minilateralism’ of the G-groups (Fioretos Citation2019), where limiting the number of members facilitates effective and efficient policymaking without the pitfalls of multilateralism (for example, small countries banding together to form blocking coalitions (Slaughter Citation2019)). Key for this role is the selective nature of G-groups, where only the most powerful states are members and the aggregate group dominates the global order.

A second role focuses on the emergence of the G-groups as a response to the challenges resulting from increasing interdependence in the global system (Kapstein Citation1994; Germain Citation2001, Citation2014). Financial globalisation and integration increased interlinkages between countries and between pillars of the financial system, warranting forums that have comprehensive overview and can make political decisions across different areas (Viola Citation2014, 116). The membership of the G-groups is dependent on the relevance of countries in terms of risks for global financial stability. Financial regulations need to take account of a diversity of local circumstances in systemically relevant countries to be effective, which requires the inclusion of local regulators and supervisors in the development of global financial governance (Underhill, Blom, and Mügge Citation2010). In addition, implementation of strengthened financial regulations requires ownership, which can be ensured through membership in the G-groups (Germain Citation2001). These different issues point to the importance of G-group members in the global financial system (‘systemically relevant’) as a key underpinning of the relevant membership in this role.

The third role focuses on the G-groups in relation to other international organisations. Baker (Citation2006, Citation2010) argues that first the G7 and now the G20 steer the more technical forums that produce financial regulations and execute instructions of the G-groups. This allows the G-groups to set governance patterns for a much wider set of actors (through the wider membership or reach of the technical institutions) without having to involve all of them in strategic decision-making. In addition, it allows the G-group to orchestrate among the proliferating technical institutions such as the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS), Financial Stability Board (FSB), International Monetary Fund (IMF), and International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO) (Viola Citation2015, 98; see Dobson’s (Citation2006) characterisation of the G7 as a plate spinner). In addition, by endorsing policy initiatives the G-groups confer a political blessing to technical forums (Eccleston, Kellow, and Carroll Citation2015). The G-groups can exercise this role through their dominant position in the decision-making bodies of the technical forums in terms of number of members or voting weight (Woods Citation2010). In sum, the position of G-group members in other international organisations is key in the relevance of a member for this role.

Distinguishing the various roles of the G-groups emerging from these strands of literature allows us to derive different empirical indicators for the ‘relevant actors’ that need to be included to obtain rightful membership. The realist logic (often implicitly) determines rising powers by their convergence to the main powers in the global economy or by their position in networks of economic interdependence (Cooper Citation2010, 750; Kahler Citation2013). In other words, rightful membership would be indicated by real-economy variables like gross domestic product (GDP) and trade. Under the second, functionalist role the focus is on the relevance of countries to the global financial system, as home countries to large banking or capital markets, for example. The third strand of literature emphasises the G-groups’ coordinating role; thus, the focus for indicators of rightful membership is on the stake of G-group members in technical forums.

In sum, linking rightful membership to G-group roles leads to a granular framework that can assess variation in legitimacy dynamics across roles. It allows researchers to empirically test a normative criterion like G-group representativeness by operationalising it in terms of, for example, economic or financial weight. In addition, distinguishing the different roles allows insights in a longitudinal analysis where roles might have shifted over time. Relatedly, the framework permits an assessment of claims to rightful G-group membership of different states over time, where the strength of the claim of potential members might differ depending on the G-group role. The following section will examine the rightfulness of G-group membership based on the indicators related to the three roles of G-groups. This will demonstrate the variety in legitimation dynamics that this framework can unearth.

The G-group membership in the global economy

This section starts with a discussion of the establishment and selection of the membership of the G7 and G20. Subsequently, the indicators derived in the previous section are analysed over the period 1985 to 2019 for the G-group membership.Footnote2 The online Supplementary material provides detailed information on the data.

The emergence of the G7 and G20 as selective forums

The G7 originated in the increasing financial interdependence and monetary instability in the 1960s and early 1970s (Baker and Carey Citation2014). Seeking to coordinate policies in less European-dominated settings than the IMF Board, the US selected France, Germany, Japan and the UK to participate in gatherings of the ministers of finance and central bank governors in the wake of the collapse of the Bretton Woods system (Fioretos Citation2019). When some of the original finance ministers became heads of state, they re-created this grouping at the level of leaders in 1976 and invited Canada, Italy and the European Community as well. Thus, the G7 was born (Putnam and Bayne Citation1988; Dobson Citation2006).Footnote3 The finance ministers and central bank governors continued to meet as the Group of Five (G5) for another decade, only becoming the Finance G7 in 1986 (Baker Citation2006, chapter 2). The G7 has no permanent secretariat, little bureaucratic support, and no formal decision-making procedures or votes.

In response to the 1997 East Asian crisis, the G7 established the G20 ministers of finance and central bank governors to include ‘systemically significant economies’ in global financial policymaking (G7 Finance Citation1999; see Viola (Citation2020) on the notion of systemically significant economies). Similar to the establishment of the G7, there were no formal criteria justifying membership of the Finance G20. Political deliberations between a few elite policymakers of the G7 countries determined which countries were deemed systemically significant (Wade Citation2011, 354; or see the slightly different account of Kirton Citation2013, 64–65). In response to the global financial crisis of 2008, US President Bush elevated the G20 to a heads-of-state forum, with the first G20 Summit taking place in Washington, DC, in November 2008. This concluded the development in which the G7 and G20 steadily widened their remit from monetary policymaking and added a heads-of-state summit. Both the G7 and G20 function as informal ‘apex policy forums’ (Baker Citation2006, Citation2010; cf. Cooper Citation2010) which emerged in response to contemporary challenges in the global financial system, without official mandate or membership criteria.

Although the informal nature and lack of procedural clarity can make it hard for outside stakeholders to influence the process, the G20 process is more open and transparent than the G7 meetings.Footnote4 In addition, the G20 regularly invites different non-members and international organisations as guests. Nevertheless, the issue of selectivity remains. The selection of the G7 and G20 membership took place without formal criteria by, respectively, the United States and the G7. This ad hoc procedure is difficult to characterise as appropriate from a legitimacy perspective (Slaughter Citation2013, 46). However, the membership itself might still be rightful – an issue to which we turn now.

The economic and financial underpinnings of the G-group membership

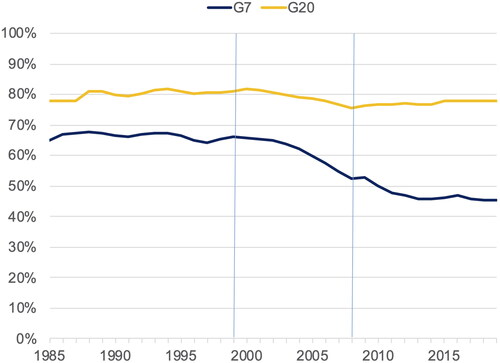

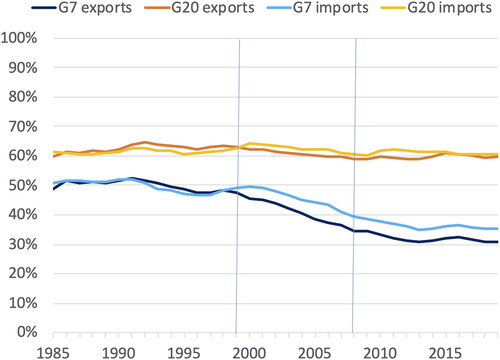

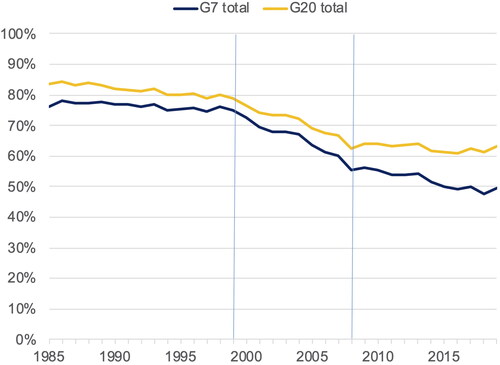

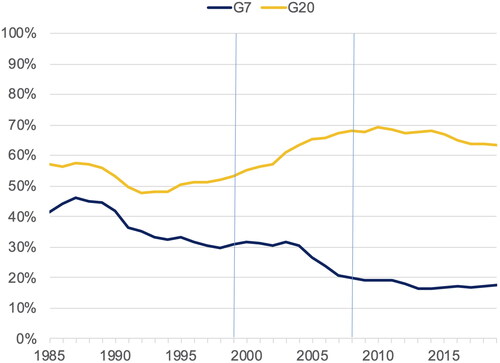

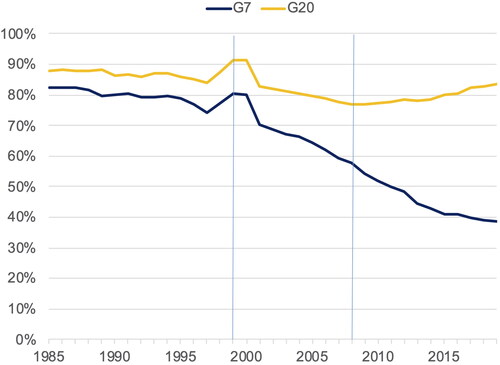

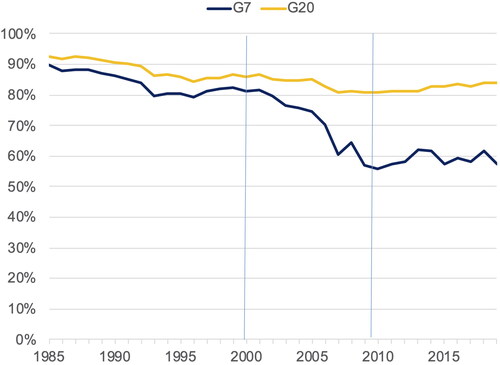

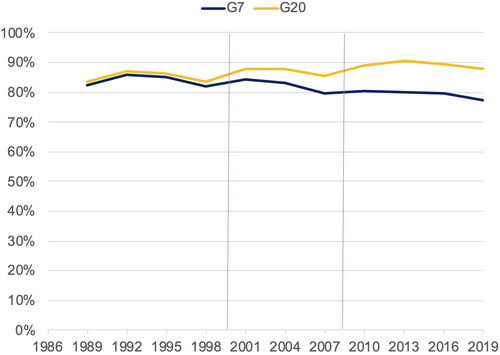

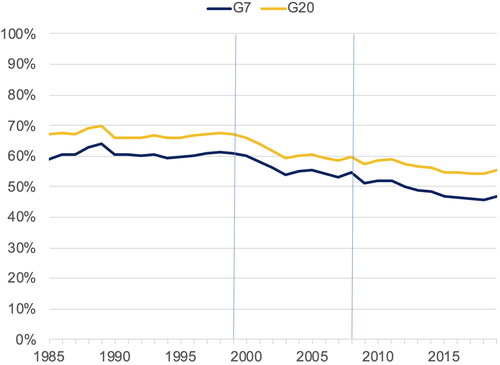

This subsection analyses economic and financial indicators underpinning G-group membership. From the perspective of accommodation of rising powers, three real-economy indicators (GDP, foreign direct investment (FDI), and trade) as well as an indicator of power in the monetary domain (official reserves) are examined. To analyse the extent to which the G20 has the relevant members to address challenges in the global financial system, four financial market indicators (bank assets, stock market capitalisation, market share of international finance (Armijo, Tirone, and Chey Citation2020) and foreign exchange trading) are examined. The analysis focuses on the share of the G7 and G20 members in the global economy and in the global financial system. provide an overview of G-group shares of world totals. The vertical lines in the graphs mark the establishment of the Finance G20 (1999) and the G20 Summit (2008).

Figure 7. Market share of international finance.

Source: External Wealth of Nations dataset (Lane and Milesi-Ferretti Citation2018).

The broad picture that emerges from the indicators is one of G7 decline in terms of its members’ share of world totals. The decline was most significant after the turn of the century and for the real-economy variables. For example, G7 GDP as a share of the global economy declined from 67% at the establishment of the Finance G7 in 1986 to 45% of the global economy in 2019. The G20 share of world totals is stable for GDP and trade at about 78 and 60%, respectively, meaning the emerging-market members compensated for the declining G7 share. Emerging-market members of the G20 ‘overcompensated’ in the build-up of official reserves, leading to a higher G20 share of the world total even when the G7 share declined. For FDI, a slight increase in the share of the global FDI stock of non-G7 members of the G20 (especially after 2008) does not compensate for the G7 decline. The rest of the world accounts for 37% of the global FDI stock in 2019.Footnote5

For the financial indicators, the emerging-market members of the G20 do not fully compensate for the declining share of the G7. Although the decline of G7 shares is more pronounced, the share of the G20 also declines. For example, the G7 share of the global banking sector declines from 83% in 1986 to 39% in 2019, while the share of the G20 also declines by five percentage points in that period. In other words: financial centres in the rest of the world have increased in importance (from a low base) and might thus have been more relevant members than the current emerging markets. That being said, the G20 is dominant in the global financial system, with a share of over 80% of bank assets, stock market capitalisation and foreign exchange trading (and about 55% on the market share of international finance indicator) over the whole period.

In sum, the decline of the G7 on real-economy indicators was most marked and best compensated by the non-G7 members of the G20. The expansion of the G7 to the G20 thus seems to have been driven most prominently by the role of the G-groups to accommodate rising powers.

Let the right ones in?

The previous subsection analysed the G-group membership in aggregate; this subsection looks at the membership in comparison to the ranking of all countries to determine whether the ‘rightful’ countries were included. compares G-group membership to the top-ranking countries at the time of establishment of the G7, Finance G20 and G20 Summit. In other words, this table shows whether the G-group members were actually the largest economies at the time.

Table 1. G7/G20 relative to top seven/top 19 economies (%).

As demonstrates, the G7 mirrored the top-ranking countries closely at its establishment. That was less the case for the G20, where Argentina and South Africa especially do not rank among the top 20 on several indicators (sometimes by far). The countries that could have been included instead of the lower ranking countries differ per indicator. A number of trading ports and financial centres (eg Hong Kong, the Netherlands, Singapore and Switzerland) warranted inclusion on trade and finance indicators, while other countries emerge in the top ranking on other indicators. Spain is among the top 20 on several finance and real-economy indicators, which has been addressed by making it a ‘permanent guest’ of the G20. In sum, although some G20 members were unlikely candidates for membership based on economic and financial indicators, there were no stand-out contenders with a stronger claim to membership on all indicators relating to a specific role. In that sense, we can say the G7 and later the G20 have rightful membership.

The literature on global elite perceptions of the legitimacy of G-group membership corroborates the assessment that there are no states with a clear claim to membership based on the indicators analysed above. Although non-members perceive the G20 membership as insufficiently rightful, individual non-members rarely lay claim to a seat on the basis of their economic or financial weight vis-à-vis current members. Rather, non-members proactively form groupings, such as the Nordic Council or the so-called Global Governance Group (3G), to advocate for membership on the basis of the aggregate grouping’s weight (Cooper and Momani Citation2014). Elites of the rising powers which are included in the G20 have a positive perception of its legitimacy (Beeson and Bell Citation2009; Brandi Citation2019). Finally, also, the self-legitimation of the G20 through its self-representation emphasises that is has members from all over of the world so that it can legitimately be the apex global governance institution (Gronau Citation2016).

Steering global governance

To assess the rightfulness of the G-groups’ membership in terms of their role in steering other global governance institutions, this section analyses the membership and voting procedures of four technical forums: the BCBS, FSB, IMF and IOSCO. These forums deal with regulation and supervision of the key pillars of the global financial system: banking, currency and capital markets (compare the financial indicators used above). provides a summary of the capacity of the G-group membership to steer these forums at key dates in the evolution of the G-groups (1986, 1999, 2008) and gives the situation in 2019. Since changes in the voting rules and participation in the forums occur on an irregular basis, this selection of years provides sufficient insight into longitudinal developments.

Table 2. G-group participation in technical forums (% of votes or seats).

The Basel Committee sets global standards for banking supervision. The membership at its establishment in 1974 consisted of Belgium, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and the United States (BIS Citation2001). Only in 2001 was membership expanded for the first time, with the addition of Spain (in terms of size, Spain’s banking sector ranked in the global top 10 continuously since 1985). In 2009 the BCBS extended membership to all G20 members as well as Hong Kong and Singapore. The current membership was reached in 2014 when the European Central Bank was added, making for a total of 28 members.Footnote6 The expansion of membership over time has decreased the weight of the G7 in deliberations, while the G20’s weight is now larger (81%) than that of the G7 ever was (58%).

The FSB was established alongside the Finance G20 in 1999 and deals with global coordination of financial market supervision and regulation (G7 Finance Citation1999).Footnote7 The initial membership of the FSB consisted of large financial centres and included national authorities from the G7 and Australia, Hong Kong, the Netherlands, Singapore and Switzerland.Footnote8 National authorities are allocated different numbers of seats based on their relative weight in the global financial system. In its original set-up, the G7 countries had three seats each, while the other national authorities had one each. In 2009, all G20 members gained membership and the number of seats per authority was revised (Pagliari Citation2014). Brazil, Russia, India and China were successful in getting representation on par with the G7. The other G20 members got two seats (Australia, the European Union, Mexico, South Korea, and permanent G20 guest Spain) or one (Argentina, Indonesia, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, and Turkey). In other words, the G7 was firmly in control of the FSB during its initial decade, with 81% of the national seats. Only after the global financial crisis of 2008 did this shift to a controlling position of the G20 with 86% of the national seats (the G7 share of national seats declined to about one-third).

The IMF is the oldest of these technical forums, originating as a pillar of the Bretton Woods system. Its current mission is to promote the stability of the international monetary system. Most countries in the world are members of the IMF, with voting rights based on a country’s position in the global economy. The alignment of voting weight to actual current position in the global economy is skewed towards traditional economic heavyweights, however, as quota reform is often stalled by members that stand to lose from the change. Although the G7 never had a decisive majority for all decisions, the United States alone has always held a veto over decisions which had to be taken with a qualified majority (such as changes to the articles of agreement). The voting weight of the G20 has stayed almost constant, although it has slightly rebalanced in favour of the emerging-market members.

IOSCO, lastly, was established in 1983 to develop regulatory standards that promote transparency and efficiency in global capital markets.Footnote9 Its membership consists of public regulatory agencies and self-regulatory organisations and has grown to 115 jurisdictions, covering most global capital market activity. Its most important decision-making body is the IOSCO Board.Footnote10 The Board originally consisted of key international financial centres (the G7 plus Australia, Hong Kong, the Netherlands, Singapore, Spain and Switzerland). In 2007 Mexico joined, followed by Brazil, China and India in 2009. Currently, the Board has expanded to 34 securities regulators. In practice these consist of the G20 plus a varying set of 15 countries. In other words: until 2008 the G7 held a majority of seats, while nowadays the G20 does.

In sum, the voice of rising powers in the technical forums has been significantly strengthened. The combined G20 voice in the technical forums is now stronger than the G7 voice ever was. Crucially, this increasing capacity of the G20 membership to steer the technical forums only came about after the initial G20 Summit in 2008 called for governance reforms of the technical forums in the wake of the global financial crisis (G20 Citation2008a). For the first 10 years of the Finance G20’s existence, the capacity to steer the technical forums was still firmly in the hands of G7 members. The membership of the G20 was thus initially not rightful in terms of the G-group’s steering role, but the membership of the technical forums has been adjusted retrospectively to create such rightful membership.

Conclusions

This paper has developed a framework of rightful membership in relation to different roles of global governance institutions to shed new light on the debate over legitimacy in global governance. This framework has the benefit of offering a granular insight into different dynamics of rightful membership as a source of legitimacy. In addition, it offers analytical leverage over the interactions between rightful membership in one role on dynamics in other roles as well as the variation of rightful membership as a source of legitimacy over time and roles.

The analytical leverage of this framework was demonstrated through an empirical analysis of the rightfulness of G-group membership, guided by three questions: (1) how have the G-group members developed in terms of financial and economic indicators; (2) how has the ranking of the G-group membership developed on these indicators; and (3) how has the position of the G-group membership in technical forums of financial governance developed? In this conclusion, the empirical patterns emerging from the answers to these questions are used as building blocks to demonstrate the added value of analysing sources of G-group legitimacy based on rightful membership in relation to global governance institutions’ roles.

First, it can be concluded that the G7 at its establishment and the G20 currently have rightful membership. Their aggregate shares in the global economy on the financial and economic indicators analysed in this paper are dominant and they have the capacity to orchestrate technical forums. Furthermore, the aggregates demonstrate why the shift from the G7 to the G20 was necessary to retain the rightful membership: the position of the aggregate G7 membership in the global economy diminished on all financial and economic indicators. The longitudinal analysis demonstrates that the decline of G7 shares in global totals was most prominent after the turn of the century. In other words, the G7’s claim to have the relevant membership to steer global governance rang increasingly hollow. For the real-economy indicators of GDP and trade, the emerging-market members of the G20 more or less compensated for the G7’s decline. For official reserves, they even overcompensated. For most financial variables the rising powers only partially compensate for the G7 decline. These findings suggest that the shift from the G7 to the G20 was mainly driven by real-economy variables – or, in other words, that the rightful membership of the G20 is mainly based on its role as accommodator of rising powers.

Second, the analysis of the ranking of world countries on the indicators demonstrates that while the G7 members at the time of selection were among the top seven on GDP, trade and bank assets, the G20 members selected in 1999 did not mirror the top 20 ranking countries on any indicator. There was no specific country that consistently ranked better on the different indicators. However, when we distinguish between the different roles, the selection of G20 membership seems to have been driven more by real-economy indicators than by financial indicators (otherwise, inclusion of financial centres like Hong Kong, the Netherlands and Switzerland would have been warranted). This corroborates the first conclusion above and reflects the variegated dynamics of rightful membership when analysed in terms of different roles of global governance institutions.

Third, with respect to the orchestration role, membership of the technical forums was adjusted to the G-group membership rather than the G-group members being selected for the G-group to have rightful membership in this role. This demonstrates how rightful membership differs between roles and how G-group rightful membership interacts with rightful membership of technical forums: rightful membership in one role diffused to the membership of technical forums to ensure rightful membership with respect to the orchestrator role as well.

These findings illustrate the analytical added value of using rightful membership in relation to different roles as a framework to approach the legitimacy of global governance institutions. This is all the more important for selective global governance institutions like the G-groups which have no official membership criteria: a claim to rightful membership is key to achieve input legitimacy. The conceptualisation of rightful membership in this paper provides tools to scrutinise such claims, and showed in the case of the G20 that there are variations in legitimation dynamics between the different roles and that rightful membership in one role (the accommodation of rising powers warranting the shift from the G7 to the G20) interacts with memberships in other roles (eg the role of orchestrating technical forums). In addition, expansion of membership has been one of the prime strategies used by global governance institutions to increase input legitimacy (Guastaferro and Moschella Citation2012). The analysis in this paper demonstrates the importance of selecting the right members and linking this selection process to the roles the global governance institutions fulfil if the potential legitimacy gains are to be realised.

The analysis points to a number of avenues for further work on the legitimacy of global governance institutions. First of all, a study of the legitimacy perceptions of different audiences can build on the framework developed in this paper. The case analysis has demonstrated the variegated nature of the legitimacy dynamics over different roles, which could be augmented and deepened by an investigation of how this plays out among different publics, and across time and regions (Brandi Citation2019). Do the legitimacy perceptions of the G-groups differ because they are based on different views on what constitutes the rightful membership as a source of legitimacy? For example, do audiences in the Global South focus on G-groups’ role as accommodator of rising powers and base their legitimacy assessment on that, while audiences in the North focus on the capacity to solve financial challenges? How do claims to legitimacy based on rightful membership in specific roles feed into political contestation by the wider public (Imerman Citation2018, 84)? Distinguishing rightful membership in terms of different roles thus offers a range of interesting research questions to come to a better understanding of the dynamics of the legitimacy of global governance institutions in countries across the globe. Secondly, the extension of membership of rising powers from the G20 to the technical forums points to the interaction of rightful membership across different global governance institutions. The potential synergies and conflicts that might emerge in this process warrant further study, as does the potential for competing legitimacy claims based on different role perceptions among global governance institutions (Tallberg and Zürn Citation2019).

In sum, as I have argued in this paper, rightful membership in relation to different roles in global governance provides a fruitful framework to guide further work on the legitimacy of selective global governance institutions in both the normative and sociological legitimacy traditions.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (25.5 KB)Acknowledgements

I thank Andrew Baker, Matt Bishop and the SPERI team for their valuable comments on a draft of this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Jasper Blom

Jasper Blom is a Marie Sklodowska-Curie Research Fellow at the Sheffield Political Economy Research Institute on the project G20LAP: G20 Legitimacy and Policymaking. His research interests include global financial governance, G20 policymaking, and the political ramifications of the Anthropocene. With Geoffrey Underhill and Daniel Mügge, he has edited Global Financial Integration Thirty Years On, from Reform to Crisis (Cambridge University Press, 2010).

Notes

1 On the one hand, Payne (Citation2010) and Vestergaard and Wade (Citation2012) point out the G20 excludes most of the world’s countries. On the other hand, Bergsten (Citation2004), Beeson and Bell (Citation2009) and Cammack (Citation2012) argue that the G20 is at least more inclusionary than the G7.

2 The membership and participation of the EU in the G-groups is complex (see Debaere and Orbie Citation2013) and the three largest EU economies (Germany, France and Italy) are also members on their own behalf. To avoid double counting or overestimation, the EU is therefore not included in the aggregate economic and financial indicators used here.

3 The European Community did not count as an official member towards the seven.

4 Compare, for example, the wealth of G20 policy documentation to that relating to the G7 at the University of Toronto’s G8/G20 information centres. See also Hajnal (Citation2014) on the different groups feeding into the G20 process.

5 This figure might be slightly misleading, though. In 2019, Hong Kong counts for 5% and likely reflects in part Chinese mainland FDI, while the Netherlands (a conduit for global FDI) counts for 6%.

6 Data from the BIS website (www.bis.org), and various press releases.

7 Before 2008, the FSB was known as the Financial Stability Forum. For convenience, FSB is used throughout this paper.

8 Canadian prime minister Martin had originally proposed to mirror G20 membership but was rebuffed (Kirton Citation2013, 61), another indication that financial indicators were not leading in the selection of the G20 membership.

9 See the IOSCO website (www.iosco.org).

10 Before 2012 the Board was called the Technical Committee.

Bibliography

- Agné, H. 2018. “Legitimacy in Global Governance Research: How Normative or Sociological Should It Be?.” In Legitimacy in Global Governance: Sources, Processes, and Consequences, edited by J. Tallberg, K. Bäckstrand, and J. A. Scholte, 20–34. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Archer, C. 2014. International Organizations. 4th ed. London: Routledge.

- Armijo, L. E., D. C. Tirone, and H. Chey. 2020. “The Monetary and Financial Powers of States: Theory, Dataset, and Observations on the Trajectory of American Dominance.” New Political Economy 25 (2): 174–194. doi:10.1080/13563467.2019.1574293.

- Åslund, A. 2009. “The Group of 20 Must Be Stopped.” Financial Times, 26 November.

- Baker, A. 2006. The Group of Seven: Finance Ministries, Central Banks and Global Financial Governance. London: Routledge.

- Baker, A. 2010. “Deliberative International Financial Governance and Apex Policy Forums.” In Global Financial Integration Thirty Years on: From Reform to Crisis, edited by G. R. D. Underhill, J. Blom, and D. Mügge, 58–73. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Baker, A., and B. Carey. 2014. “Flexible ‘G Groups’ and Network Governance in an Era of Uncertainty and Experimentation.” In Handbook of the International Political Economy of Governance, edited by A. Payne and N. Phillips, 89–107. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

- Barnett, M. N., and M. Finnemore. 1999. “The Politics, Power, and Pathologies of International Organizations.” International Organization 53 (4): 699–732. doi:10.1162/002081899551048.

- Beeson, M., and S. Bell. 2009. “The G-20 and International Economic Governance: Hegemony, Collectivism, or Both?” Global Governance: A Review of Multilateralism and International Organizations 15 (1): 67–86. doi:10.1163/19426720-01501005.

- Benson, R., and M. Zürn. 2019. “Untapped Potential: How the G20 Can Strengthen Global Governance.” South African Journal of International Affairs 26 (4): 549–562. doi:10.1080/10220461.2019.1694576.

- Bergsten, F. C. 2004. “The G-20 and the World Economy.” World Economics Journal 5 (3): 27–36.

- Bernstein, S. 2011. “Legitimacy in Intergovernmental and Non-State Global Governance.” Review of International Political Economy 18 (1): 17–51. doi:10.1080/09692290903173087.

- Best, J. 2007. “Legitimacy Dilemmas: The IMF’s Pursuit of Country Ownership.” Third World Quarterly 28 (3): 469–488. doi:10.1080/01436590701192231.

- BIS. 2001. “History of the Basel Committee and Its Membership.” Accessed May 16, 2022. https://www.bis.org/publ/bcbsc101.pdf

- Bishop, M. L., and A. Payne. 2021. “Steering towards Reglobalization: Can a Reformed G20 Rise to the Occasion?” Globalizations 18 (1): 120–140. doi:10.1080/14747731.2020.1779964.

- Brandi, C. 2019. “Club Governance and Legitimacy: The Perspective of Old and Rising Powers on the G7 and the G20.” South African Journal of International Affairs 26 (4): 685–702. doi:10.1080/10220461.2019.1697354.

- Brassett, J., and E. Tsingou. 2011. “The Politics of Legitimate Global Governance.” Review of International Political Economy 18 (1): 1–16. doi:10.1080/09692290.2010.495297.

- Buchanan, A., and R. O. Keohane. 2006. “The Legitimacy of Global Governance Institutions.” Ethics & International Affairs 20 (4): 405–437. doi:10.1111/j.1747-7093.2006.00043.x.

- Cammack, P. 2012. “The G20, the Crisis, and the Rise of Global Developmental Liberalism.” Third World Quarterly 33 (1): 1–16. doi:10.1080/01436597.2012.628110.

- Chodor, T. 2020. “The G20’s Engagement with Civil Society: Participation without Contestation?” Globalizations 17 (6): 903–916. doi:10.1080/14747731.2019.1702804.

- Clark, I. 2007. Legitimacy in International Society. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199219193.001.0001.

- Coleman, W. D., and T. Porter. 2000. “International Institutions, Globalisation and Democracy: Assessing the Challenges.” Global Society 14 (3): 377–398. doi:10.1080/13600820050085769.

- Cooper, A. F. 2010. “The G20 as an Improvised Crisis Committee and/or a Contested ‘Steering Committee’ for the World.” International Affairs 86 (3): 741–757. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2346.2010.00909.x.

- Cooper, A. F. 2013. “Squeezed or Revitalised? Middle Powers, the G20 and the Evolution of Global Governance.” Third World Quarterly 34 (6): 963–984. doi:10.1080/01436597.2013.802508.

- Cooper, A. F., and B. Momani. 2014. “Re-Balancing the G-20 from Efficiency to Legitimacy: The 3G Coalition and the Practice of Global Governance.” Global Governance: A Review of Multilateralism and International Organizations 20 (2): 213–232. doi:10.1163/19426720-02002004.

- Debaere, P., and J. Orbie. 2013. “The European Union in the Gx System.” In Routledge Handbook on the European Union and International Institutions: Performance, Policy, Power, edited by K. E. Jørgensen and K. V. Laatikainen, 311–323. London: Routledge.

- Dobson, H. 2006. The Group of 7/8. London: Routledge.

- Downie, C. 2017. “One in 20: The G20, Middle Powers and Global Governance Reform.” Third World Quarterly 38 (7): 1493–1510. doi:10.1080/01436597.2016.1229564.

- Eccleston, R., A. Kellow, and P. Carroll. 2015. “G20 Endorsement in Post Crisis Global Governance: More Than a Toothless Talking Shop?” British Journal of Politics and International Relations 17 (2): 298–317. doi:10.1111/1467-856X.12034.

- Fioretos, O. 2019. “Minilateralism and Informality in International Monetary Cooperation.” Review of International Political Economy 26 (6): 1136–1159. doi:10.1080/09692290.2019.1616599.

- G20. 2008a. “Declaration of the Summit on Financial Markets and the World Economy.” Washington DC, G20.

- G20. 2008b. “The Group of Twenty: A History.” Accessed May 16, 2022. http://www.g20.utoronto.ca/docs/g20history.pdf

- G20. 2009. Leaders’ Statement of the Pittsburgh Summit. Pittsburgh: G20.

- G7 Finance. 1999. Communiqué of G-7 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors. Bonn: G7 Finance.

- Germain, R. D. 2001. “Global Financial Governance and the Problem of Inclusion.” Global Governance: A Review of Multilateralism and International Organizations 7 (4): 411–426. doi:10.1163/19426720-00704006.

- Germain, R. D. 2014. “The Historical Origins and Development of Global Financial Governance.”, In Handbook of Global Economic Governance: Players, Power and Paradigms, edited by M. Moschella and C. Weaver, 97–114. London: Routledge.

- Gronau, J. 2016. “Signaling Legitimacy: Self-Legitimation by the G8 and the G20 in Times of Competitive Multilateralism.” World Political Science 12 (1): 107–145. doi:10.1515/wps-2016-0005.

- Gronau, J., and H. Schmidtke. 2016. “The Quest for Legitimacy in World Politics – International Institutions’ Legitimation Strategies.” Review of International Studies 42 (3): 535–557. doi:10.1017/S0260210515000492.

- Guastaferro, B., and M. Moschella. 2012. “The EU, the IMF, and the Representative Turn: Addressing the Challenge of Legitimacy.” Swiss Political Science Review 18 (2): 199–219. doi:10.1111/j.1662-6370.2012.02067.x..

- Hajnal, P. I. 2014. The G20: Evolution, Interrelationships, Documentation. London: Routledge.

- Hurd, I. 1999. “Legitimacy and Authority in International Politics.” International Organization 53 (2): 379–408. doi:10.1162/002081899550913.

- Hurd, I. 2008. “Myths of Membership: The Politics of Legitimation in UN Security Council Reform.” Global Governance: A Review of Multilateralism and International Organizations 14 (2): 199–218. doi:10.1163/19426720-01402006.

- Imerman, D. 2018. “Contested Legitimacy and Institutional Change: Unpacking the Dynamics of Institutional Legitimacy.” International Studies Review 20 (1): 74–100. doi:10.1093/isr/vix039.

- Kahler, M. 2004. “Defining Accountability Up: The Global Economic Multilaterals.” Government and Opposition 39 (2): 132–158. doi:10.1111/j.1477-7053.2004.00003.x.

- Kahler, M. 2013. “Rising Powers and Global Governance: Negotiating Change in a Resilient Status Quo.” International Affairs 89 (3): 711–729. doi:10.1111/1468-2346.12041.

- Kapstein, E. B. 1994. Governing the Global Economy: International Finance and the State. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

- Keohane, R. O. 2011. “Global Governance and Legitimacy.” Review of International Political Economy 18 (1): 99–109. doi:10.1080/09692290.2011.545222.

- Kirton, J. J. 2013. G20 Governance for a Globalized World. London: Routledge.

- Kirton, J. J. 2016. China’s G20 Leadership. London: Routledge.

- Lane, P. R., and G. M. Milesi-Ferretti. 2018. “The External Wealth of Nations Revisited: International Financial Integration in the Aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis.” IMF Economic Review 66 (1): 189–222. doi:10.1057/s41308-017-0048-y.

- Larson, D. W. 2018. “New Perspectives on Rising Powers and Global Governance: Status and Clubs.” International Studies Review 20 (2): 247–254. doi:10.1093/isr/viy039.

- Newman, E., and B. Zala. 2018. “Rising Powers and Order Contestation: Disaggregating the Normative from the Representational.” Third World Quarterly 39 (5): 871–888. doi:10.1080/01436597.2017.1392085.

- Pagliari, S. 2014. “The Financial Stability Board as the New Guardian of Financial Stability.” In Handbook of Global Economic Governance: Players, Power and Paradigms, edited by M. Moschella and C. Weaver, 143–155. London: Routledge.

- Payne, A. 2010. “How Many Gs Are There in ‘Global Governance’ after the Crisis? The Perspectives of the ‘Marginal Majority’ of the World’s States.” International Affairs 86 (3): 729–740. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2346.2010.00908.x.

- Putnam, R., and N. Bayne. 1988. Hanging Together: Cooperation and Conflict in the Seven-Power Summits. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

- Reus-Smit, C. 2007. “International Crises of Legitimacy.” International Politics 44 (2-3): 157–174. doi:10.1057/palgrave.ip.8800182.

- Slaughter, S. 2013. “Debating the International Legitimacy of the G20: Global Policymaking and Contemporary International Society.” Global Policy 4 (1): 43–52. doi:10.1111/j.1758-5899.2012.00175.x.

- Slaughter, S. 2019. “The G20 and Realist International Relations Theory.” In The G20 and International Relations Theory: Perspectives on Global Summitry, edited by S. Slaughter, 37–55. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

- Slaughter, S. 2020. The Power of the G20: The Politics of Legitimacy in Global Governance. London: Routledge.

- Tallberg, J., K. Bäckstrand, and J. A. Scholte, eds. 2018. Legitimacy in Global Governance: Sources, Processes, and Consequences. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Tallberg, J., and M. Zürn. 2019. “The Legitimacy and Legitimation of International Organizations: Introduction and Framework.” The Review of International Organizations 14 (4): 581–606. doi:10.1007/s11558-018-9330-7.

- Underhill, G. R. D., J. Blom, and D. Mügge. 2010. “Introduction.” In Global Financial Integration Thirty Years on: From Reform to Crisis, edited by G. R. D. Underhill, J. Blom, and D. Mügge, 1–22. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Vabulas, F., and D. Snidal. 2013. “Organization without Delegation: Informal Intergovernmental Organizations (IIGOs) and the Spectrum of Intergovernmental Arrangements.” The Review of International Organizations 8 (2): 193–220. doi:10.1007/s11558-012-9161-x.

- Vestergaard, J., and R. Wade. 2012. “Establishing a New Global Economic Council: Governance Reform at the G20, the IMF and the World Bank.” Global Policy 3 (3): 257–269. doi:10.1111/j.1758-5899.2012.00169.x.

- Viola, L. A. 2014. “The G-20 and Global Financial Regulation.” In Handbook of Global Economic Governance: Players, Power and Paradigms, edited by M. Moschella and C. Weaver, 115–128. London: Routledge.

- Viola, L. A. 2015. “Orchestration by Design: The G20 in International Financial Regulation.” In International Organizations as Orchestrators, edited by K. Abbott, 88–113. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Viola, L. A. 2020. ““Systemically Significant States”: Tracing the G20’s Membership Category as a New Logic of Stratification in the International System.” Global Society 34 (3): 335–352. doi:10.1080/13600826.2020.1739630.

- Wade, R. 2011. “Emerging World Order? From Multipolarity to Multilateralism in the G20, the World Bank, and the IMF.” Politics & Society 39 (3): 347–378. doi:10.1177/0032329211415503.

- Wight, M. 1972. “International Legitimacy.” International Relations 4 (1): 1–28. doi:10.1177/004711787200400101.

- Woods, N. 2010. “Global Governance after the Financial Crisis: A New Multilateralism or the Last Gasp of the Great Powers?” Global Policy 1 (1): 51–63. doi:10.1111/j.1758-5899.2009.0013.x.