Abstract

A key but neglected dimension of developmental industrial policy is the formation of a mutually beneficial relationship among developing country governments, domestic capital and multinational corporations, or what Peter Evans has termed ‘dependent development’. Such relationships were a prominent feature of the growth trajectories of Latin American and East Asian industrialisers in the 1960s and 1970s. This article argues, however, that dependent development is a historically specific phenomenon; it is much harder to achieve for developing countries attempting industrial development after the 1990s, when multinationals have significantly more power and autonomy in relation to the state in developing countries, as a result of domestic liberalisation and changes in the international regimes of trade and investment. These power imbalances have persisted in the last two decades. The article examines the institutional relationships among states, multinationals and domestic firms after neoliberal economic reform and globalisation, and demonstrates the substantive constraints of multinationals in executing externally oriented industrial policies in a most likely case, that of India.

There has been a renewed focus on industrial policy among developing countries, resuscitating the recognition that now-wealthy countries achieved success through systematic intervention in the domestic economy and strategic engagement with international markets (Nem Singh and Ovadia Citation2018; Chimhowu, Hulme, and Munro Citation2019). Such interventionism is implicated in the growth experience of ‘developmental states’ in East Asia. Developing countries wishing to emulate their successes have launched programmes focusing on the coordination of domestic actors and deployment of resources to enable industrial investment.

An important related challenge in developing countries is executing transformations in the character of engagement with the global economy. The classical form of this activity was the use of trade protection to cultivate import-substituting or export-led infant industries. But a less-noticed but crucial aspect of the international dimensions of industrial policy is that of foreign direct investment (FDI), in which multinational corporations establish manufacturing operations in developing countries, thus providing the latter greater access to capital and technology in order to produce more sophisticated goods domestically, for home and foreign markets. Productive, long-term FDI entails transformations in the relationship between the state, local capital and multinationals. Evans powerfully argued that governments in developing countries with sufficient capacity and authority could, through strategic negotiations, form mutually beneficial relationships with multinationals and domestic firms – a ‘triple alliance’ – through localising industrial processes of sophisticated products, a dynamic he termed ‘dependent development’ (Evans Citation1979). Although the trajectories of dependent development in Latin America were stymied by debt crises in the early 1980s, the technology-intensive investment of multinational firms, through state facilitation and coordination with domestic capital, were implicated in the remarkable performance of East Asian countries.

In this article, I emphasise the historical specificity of the dependent development framework, and the related limits to mutually beneficial cooperation between multinationals and developing countries today. These arrangements were plausibly available to more advanced developing countries until the 1990s, but they may not be possible for countries attempting to pursue activist industrial policy today, because of profound changes in the nature of domestic and international political economy over the last three decades.

Specifically, ‘the neoliberal turn’ in the domestic political economy of developing countries and changes in the rules of trade and investment have provided multinationals with significantly more and state actors with significantly less power, autonomy and strategic direction in determining the nature and outcomes of investment. Economic liberalisation programmes have meant that the capacities and political interests of the state are not oriented towards a strategic, developmental direction. Changes in the institutions of global trade and investment have lowered trade barriers and tied trade access to rules of investment and intellectual property in ways that diminish key bargaining chips, such as that of market access, for developing country governments. These changes have enabled multinationals to construct cross-border production networks, over which they have significant control, and integrate domestic firms into them. Much domestic capital is either allied with multinationals in this manner or else engaged in rent-seeking activities, and thus would find cause to reject the state’s strategic direction. The nature of FDI and the skewed power relationships between multinationals and developing countries should thus be seen as a significant, if underappreciated, barrier to industrial growth for developing countries after the 1990s, one that must be overcome for industrial policy to be effective for developing countries.

Industrial policy, foreign investment and dependent development

Discussions of activist industrial policy centre around the coordinated allocation of resources and credit (Gerschenkron Citation1962). Activist governments develop tools to pool together domestic investible capital and direct it to where it might produce the greatest returns over the long term, formulating sectoral strategies and picking ‘national champions’. For our purposes, there are two salient features in this classical conception of industrial policy. First, the availability of technology was not a particular constraint. From the dawn of the industrial age until fairly recently, skilled immigrants and foreign technical advisors brought with them novel technologies; industrial espionage was rampant, and patent-holders lacked the means to enforce their intellectual property across borders. Second, FDI was not traditionally considered a salutary component of strategies of overcoming the constraints of late development. Lenin (Citation1917) famously argued that foreign investment was associated with imperial conquest. Dependency theorists similarly viewed FDI as perpetuating structurally inequitable power relations between rich and poor countries (Gunder Frank Citation1967).

Developing countries achieving their independence or asserting their autonomy in the interwar period and in the decades following World War II, from Brazil and Mexico to Turkey and India, thus shunned deep engagement with foreign agents and instead pursued state-directed import-substituting industrialisation (ISI) strategies. Foreign aid relieved constraints on capital, bridging savings and foreign exchange gaps (Chenery Citation1969). In addition, as a result of Cold War competition, both the United States and the Soviet Union provided significant technical assistance to their clients.

For the most industrially advanced countries in the developing world, these strategies had hard limits, which were reached by the early to mid-1960s. Once the domestic markets for products of the early, ‘horizontal’ stages of industrialisation, of light consumer goods, were exhausted, the most rapidly industrialising states in Latin America, and later in East Asia, sought to undertake the difficult transition to second-stage, ‘vertical’ ISI: the manufacturing of capital goods and complex consumer durables like automobiles. From the late 1960s, newly industrialising countries (NICs) even pursued export-promotion strategies of industrial components – such as those of the automotive industry in Mexico and Brazil – to alleviate balance-of-payment difficulties and secure sustainable trajectories of growth (see Hirschman Citation1968).

The transition from first-stage, horizontal to second-stage, vertical industrialisation, and ultimately towards export promotion, necessitated deeper engagement with multinational corporations. Multinationals owned the technology necessary to manufacture sophisticated components of capital goods and consumer durables at reasonable costs, and they controlled export markets. For their part, multinationals had previously been loath to locate production in developing countries, but by the mid-1960s, they were eager for greater access to growing markets in middle-income countries, as their own home markets were saturated.

Evans argued that the strength of the state was the necessary factor in forging positive-sum relationships with and between multinationals and domestic capital, thus creating a ‘triple alliance’ to manage the successful transition from autarkic, nationalist production of classic, early ISI – in Brazil and other Latin American countries from the 1930s to the late 1950s – to vertical, intensive forms of ISI and export promotion (Evans Citation1979). Writing within the context of the mature dependency theory that recognised national variation and institutional interplay between domestic and international dynamics (Cardoso and Faletto Citation1979), Evans framed the consequence of these alliances as ‘dependent development’. These dynamics were a feature of countries of the semi-periphery that still maintained relationships with industrialised countries but were, nonetheless, able to pursue and achieve autonomous trajectories in intensive industrial development. The politics behind these alliances were exclusionary – they were inconsistent with democracy and the active participation of labour – but they did represent a means of transcending the trap of lower value-added production in early-stage ISI.

Dependent development in Latin America and East Asia

The ‘triple alliance’ between the state, local capital and multinational corporations at the heart of dependent development occurred at the conjunction of a number of specific processes in the international economy and domestic politics, in Latin America and in East Asia (Gereffi and Evans Citation1981). NICs faced powerful incentives to move away from the domestic production of consumer goods. The ‘easy’ stage of import substitution had been buoyed by a world boom during World War II and the Korean War and high commodity prices, as well as greater ideological support for the state’s autonomy. Once these salutary conditions ended, countries were faced with significant capital to broaden domestic production into consumer durables and capital goods, from cars and refrigerators to machine tools. At the same time, multinationals were keen on expanding sales to developing countries as home markets approached saturation, even if this meant localising production and transferring technology abroad. In Latin American NICs by the late 1960s, populist leadership had given way to more bureaucratic-authoritarian regimes hospitable to foreign investors wary of potential nationalisation (O’Donnell Citation1988). East Asian regimes, meanwhile, were more resolutely authoritarian, with one-party rule under the Kuomintang being established in 1949 and the military regime under Park Chung-Hee consolidating in 1961.

The actual operation of the triple alliance varied among NICs, but it had two core features. First, it was characterised by significant inward FDI, as multinationals like Ford, General Motors and Alfa Romeo increased the scale of ‘outsourced’ manufacturing operations, in joint venture partnerships with domestic capital – or, in the case of Brazil, state-owned enterprises – under the overall guidance and regulation of the government. Second, national governments provided concrete benefits for multinationals, usually in the form of exemptions from manufacturing licensing and trade barriers, as well as credit and other incentives for their local partners. It thus represented a positive-sum engagement among the state, domestic firms and multinationals, though this was predicated on the ability of the state to create and enforce rules autonomously from the interests of national and international capital.

These relationships were formed in Latin America decades before East Asian countries, and varied significantly by sector. Bennett and Sharpe (Citation1985) emphasise the nature of strategic bargaining between the Mexican state and automotive multinationals, in which the former sought to change and partially succeeded in changing the structure of the industry by requiring that domestic firms participate actively in the manufacturing of key components for Ford and GM cars made for the Mexican market. Gereffi (Citation1982), in his analysis of the Mexican pharmaceutical sector during roughly the same period, explored how multinationals sought and achieved much more total dominance over the national industry, effectively smothering it.

By the 1970s, the NICs included countries in East and Southeast Asia as well as those in Latin America. After the Latin American debt crisis in the early 1980s, the industrial development trajectories of Latin American countries faltered. Meanwhile, the Asian NICs –Taiwan, South Korea and the ‘Little Tigers’ of Singapore and Hong Kong – continued to develop, reaching the status of high-income countries by the 1990s. The remarkable successes of East Asian countries, particularly in relation to Latin American NICs, represented a significant puzzle for the political economy of development.

Evans (Citation1987) emphasised real differences in the external environment facing Latin American and East Asian countries that might account for differences in the level of dependency and thus the possibilities of autonomous development. During the period of dependent development in 1970s Latin America, both Korea and Taiwan had substantially lower FDI from the United States, as well as aid and trade patterns that supported states and domestic bourgeoisies to the exclusion of compradors due to geopolitical considerations; multinationals did not initially target these countries, which were seen as too poor to support investment. Further, a key feature of East Asia involved an intense regional security environment (Cumings Citation1984). The rise of the People’s Republic of China meant significant security-based aid and access to markets, providing both Taiwan and South Korea with security-linked and thus more autonomous opportunities than Mexico and Brazil. Further, the much longer and deeper legacies of western FDI in Latin America meant the persistence of powerful comprador interests, legacies that East Asian countries lacked. The post-war nationalisation of Japanese imperial investments additionally provided early industrial assets on which post-colonial states could build.

Comparisons between the Latin American and East Asian experiences have more explicitly emphasised the distinctive forms of state capacity in East Asian countries. Haggard, conducting comparative analysis of Brazil, Mexico, Taiwan and Korea, argued that while all four countries faced incentives to move to vertical import-substitution and to export promotion due to the impact of external shocks, East Asian countries were able to manage both transitions successfully due to the strength of the state relative to agrarian elites and the private sector (Haggard Citation1990; Chibber Citation2003). Further, the more conservative, state-directed nature of East Asian industrialisation allowed these countries to resist the impulse of easy commercial loans enabled by the global liquidity glut following oil shocks, leading to the Latin American debt crisis. Scholars have also emphasised the ways that the state manipulated prices and suppressed spending, deliberately ‘getting the prices wrong’ to shift the economies in a strategically productive direction (Amsden Citation1989).

The surprising successes of Taiwan and Korea inspired a research tradition known as ‘the developmental state’. Originally formulated to explain the institutional sources of post-war Japanese growth, it argues that state strength is both necessary and sufficient to overcome the obstacles associated with peripheral status and achieve successful industrialisation, using Taiwan and Korea as exemplars (Johnson Citation1982). These accounts suggest that the capacity, cohesion and strategic orientation of state institutions, and their dominance over a subordinate bourgeoisie, allowed for successful strategies of managing industrial policy and export-led industrialisation in developing countries in East Asia (Wade Citation1990; Woo-Cumings Citation1991, Citation1998; Evans Citation1995). The developmental state literature shifted the causal emphasis away from the structures of the international economy and towards the domestic capacities of the state and their relationships with society as a sufficient explanation for economic development (Amsden Citation2003). As a result, the triple alliance has not been regularly deployed as a part of East Asian industrialisation.

More recent analyses of East Asian growth trajectories have moved away from a single-minded focus on the state and domestic production, however. Key multinational firms in East Asian countries have outgrown home markets, state support and financial repression; many see their continuing successes as ‘strategic coupling’, or firm strategies to manage global production networks and maintain competitive positions in global markets, as well as adapting venture capital to regional contexts (Yeung Citation2016; Klingler-Vidra Citation2018).

If we look back on the economic trajectories of East Asian countries as inseparable from the context facing other NICs in the 1970s, it becomes clear that, even though the particular dynamics are different, the generalised framework of dependent development and the dynamics of the triple alliance were as applicable to East Asia as in Latin America. For Korea, normalisation of diplomatic relations with Japan in 1965 – nearly at the end of its early, horizontal ISI push – meant imports of intermediate goods and then developmentalist foreign investment that focused on high technology products, such as in joint ventures between Mitsubishi and Hyundai in the automotive engine sector, and Sumitomo with Samsung in televisions and in the steel industry, guided by government policies – in other words, the operation of a triple alliance in strategic sectors (Amsden Citation1989, 175–176, 306–316). Similarly, state-driven strategic cooperation among state-owned enterprises, indigenous small business and multinationals in capital goods, electronics and eventually semi-conductors allowed Taiwan to escape crises following US aid withdrawal, the exhaustion of domestic markets and the normalisation of relations with the People’s Republic, and to manage domestic political tensions (Gold Citation1986). In different ways, both conform to Akamatsu’s (Citation1962) ‘wild-geese-flying’ pattern of regional growth, which itself represents in the East Asian context some of the key features of dependent development.

Globalisation, the neoliberal turn and the limits of dependent development

Yet the state’s capacity to manage relationships in the context of dependent development needs to be understood as a historically specific phenomenon, particular to the period between the 1960s and 1980s in which states, domestic bourgeoisies and multinational corporations – linked in a state-driven triple alliance – could productively bargain with one another over the terms of investment, market access and technology transfer. The international economy went through a profound series of transitions which, by the early 1990s, limited the capacities for this strategic bargaining towards positive-sum outcomes over the terms and conditions of foreign investment, by substantially increasing the power of multinationals and decreasing the power and autonomy of the state.

The latter occurred through domestic projects of neoliberal reform. Many countries in the developing world were forced to undertake International Monetary Fund and World Bank structural adjustment programmes due to economic crises. These programmes forced governments to privatise key industries, adopt floating exchange rates, marketise the allocation of credit and, crucially, decrease tariffs, eliminate quotas and dismantle industrial licensing. Together, they culminated in the state fundamentally changing its role in the economy. The state was increasingly unable to act as strategic coordinator of national development, as many of the key instruments of this role were placed under the control of the market (Naseemullah Citation2017). It also meant that developing countries had fewer bargaining chips related to market access, because the regulations barring this access were removed and multinationals could compete on a more level playing field with local firms, except in a few areas like defence. States also face increasing internal pressures to distribute resources and rents to clients, thus shifting their role as a strategic actor to a field of political contestation over these politically determined assets. Given these changes, the state is increasingly incapable of and disinterested in expending political capital to reconstitute triple alliances.

Further, global institutions changed in ways that dramatically increased the power and autonomy of multinationals, such that they have less need to submit to the state. In the 1990s, industrialised nations constructed a new architecture for global trade and investment, with the establishment of the World Trade Organization (WTO) at the end of the Uruguay Round of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) in 1995 (see Barton et al. Citation2008). This theoretically gave developing countries greater access to export markets in return for legal adherence to expanded protection for property rights, investors and trade in services. However, in reality, the additional market access was minimal relative to the greater freedom of multinationals to determine trade and investment.

The WTO combined trade, investment and intellectual property through the Trade-Related Investment Measures (TRIMS) and Trade-Related Intellectual Property (TRIPS) provisions. This provided a basis for the use of the WTO’s mechanisms for dispute resolution for amendment or abrogation of foreign investment contracts or insufficient protection of intellectual property, bringing to a multilateral forum on trade a set of bilateral investment relationships and features of domestic regulation. The increasing integration of investor and intellectual property protection in trade agreements, at multilateral, regional and bilateral levels, added to the coercive toolkit and strengthened the bargaining power of multinationals vis-à-vis host countries, especially given investor-friendly venues for dispute resolution (Morrissey and Rai Citation1995; Edwards Citation2016). These measures afforded multinationals greater freedom in outsourcing their production to developing countries while ensuring that most of the profits from these investments, particularly in export markets, would accrue to shareholders of multinationals as returns to intellectual property (Gereffi Citation2014; Schwartz Citation2017). Wade (Citation2003) has argued that the new rules of the WTO placed significant constraints on the operation of autonomous industrial policy.

There are, in addition, changes in the incentives of Western multinationals that precluded long-term ‘developmentalist’ FDI. The shareholder value revolution and corporate consolidation has meant that the collective owners of multinationals tend to prioritise high rates of return in the short to medium term, rather than the long-term investments, coordinated with the strategic interests of home governments, of earlier decades. Such returns are more easily realised by extracting the rents from protected intellectual property than by the longer-term but more positive-sum transfer of technology and permanent localisation of production that has greater spillovers.

Changes in the international economy in the twenty-first century

If the establishment of the WTO in 1995 heralded the high watermark of the multilateral trade and investment regime, then the 2000s and 2010s represented stagnation. Multilateral rules have been increasingly supplanted by bilateral or regional preferential trade agreements (PTAs). Further, the rise of China as a global economic power suggests a different approach to the investment regime envisioned by the Uruguay Round; indeed, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is self-consciously an alternative regime for trade and investment integration, with different goals and mechanisms. But collectively, these events have not in fact re-established the autonomy of developing countries.

Preferential trade agreements

PTAs have long been a part of the GATT/WTO architecture, even as they contravened most-favoured-nation principles. Originally, PTAs were understood as mechanisms for small countries with complementary economies to band together for collective action in trade negotiations, thus evening out the power differentials inherent in negotiations. Since the 1990s, PTAs have proliferated, particularly among countries with dissimilar levels of development, thus increasing the power of dominant countries over subordinate ones in more intimate institutional settings. Since the failure of the Doha Development Round, industrialised countries have turned to PTAs to pursue their trade liberalisation agendas. PTA provisions regularly contain the most far-reaching interpretations of intellectual property and investor protection, designed to benefit multinational corporations based in the richest countries party to the agreement (Lewis Citation2011; Flynn et al. Citation2012; Collins Citation2008).

Commentators have seen the proliferation of PTAs as a decline of legitimacy for the regime in its multilateral form (see Shadlen Citation2005). Yet broad continuities between WTO and PTAs complement one another. Further, as Shadlen (Citation2017) argues, PTAs have an even greater capacity to stymie industrial strategies than in multilateral institutions. From this perspective, PTAs have compensated for and indeed strengthened provisions that were central to the interests of developed countries, while other issues – such as liberalisation of agricultural trade – have languished. As such, they constitute vital components of the regime now much more than in the past, with significant consequences for the autonomy of developing countries and the capacity of the state to reforge triple alliances. Thus, PTAs, and the WTO itself, save multinationals from having to negotiate for market access by deepening in-country investment, a key feature that led multinationals to negotiate with the state in the era of dependent development.

The rise of China

The People’s Republic of China has presented itself as the most avid institutionaliser in the world economy, calling for openness, opportunity and predictability. Yet concrete Chinese actions and strategies do not protect the sovereign autonomy of developing countries. China’s approach to investment is fundamentally neomercantilist: the use of trade and investment policies to augment national economic power relative to others (Hirschman Citation1970 [1945]). By their very nature, China’s policies do not increase the autonomy of developing countries vis-à-vis multinationals, particularly those of Chinese origin; China represents a more old-fashioned threat in undercutting efforts of middle-income countries to compete in export markets (Paus Citation2012).

The BRI is a key illustration of this neomercantilist approach. Chinese commitments to trade and investment through the BRI are ex ante not conditional on host countries establishing standards for trade and creating an attractive environment for investment, as with many Western multinationals. Rather, China’s approach is focused on trade facilitation and connectivity. This approach to overseas investment in infrastructure is straightforwardly a subsidy to Chinese infrastructure companies suffering from over-capacity, although it may also present concrete benefits to poorer countries, such as Myanmar, lacking the resources to implement large-scale physical investment. Yet such investment makes them more dependent on China, particularly when developing countries suffer difficulties with loan repayment. Chinese multinational corporations, even when not actually publicly owned, maintain close ties to the state. As a result, China-based multinationals, far from submitting to a triple alliance, follow the strategic direction of the Chinese state, which is uninterested in transferring technology or localising production. Further, the emphasis of Chinese FDI on infrastructure and energy means the deployment of Chinese industrial assets, along with Chinese workers, abroad, with little to no participation of domestic industry and thus little long-term developmental benefit.

Chinese BRI investments do represent a sea change in patterns of trade and investment that would have been inconceivable just 20 years ago. But they also represent a strategy to maximise China’s national economic and security interests: by decreasing transportation costs with key trading partners, by increasing the size of their economies and thus their capacity to import Chinese goods, by increasing the power of the renminbi as an international currency, by providing unfettered access to energy through ports and pipelines in South and Southeast Asia, and by providing the surfeit of Chinese infrastructure construction businesses an outlet in foreign markets (Brooks and Menon Citation2008; Jiang Citation2013; Djankov and Miner Citation2016). As a result, Chinese BRI investments are orthogonal to the dynamics of the triple alliance, in which governments could forge strategic alliances with multinationals and domestic capital.

The constrained possibilities for dependent development: India in comparative perspective

To explore the dynamics of dependent development, and the factors that might prevent their successful establishment beyond particular regional and historical contexts, I turn now to a well-studied case in terms of industrial strategy: that of India. At first glance, India may be an odd case for discussions of dependent development and the forging of triple alliances. It represented a middling post-war case for scholars of state-directed development; Chibber argued that the relative failure of India in contrast to Korea was the result of bourgeois capture of state institutions and thus the pursuit of trade protection rather than export promotion, and Kohli situated these outcomes in the multi-class, fragmented nature of the Indian state, legacies of British colonial rule (Chibber Citation2003; Kohli Citation2004). The less-than-strategic orientation of the state in practice, along with its significantly underdeveloped industrial structure, and its peripheral status in Cold War competition and the world economy, represent a compelling set of explanations as to why India did not become a NIC at the same time as Mexico, Brazil, Korea and Taiwan, between the 1960s and 1980s.

But why could India not benefit from some new dynamics of dependent development today? This is a more difficult question, given India’s growth trajectory since liberalisation in the 1990s and the attention it has garnered from multinational corporations. Indeed, there are some factors that might make India the perfect candidate for successful industrial policy through strategic engagement with multinationals. First, it represents one of the most valuable internal markets, with hundreds of millions of middle-class consumers, thus a key target for multinationals. Second and relatedly, India maintains relatively high tariffs, particularly in key value-added segments, representing a powerful bargaining chip in negotiations with multinationals over the nature of FDI. Foreign investment itself has increased dramatically in India, FDI net flows as a proportion of gross domestic product (GDP) has gone from an average of 0.03 in the 1970s and 1980s to an average of 1.63% (of a much larger national product) since 2000. Third, the Indian state, now more than previously, has indicated a willingness to forge close, strategic connections with the private sector, as part of a ‘new developmentalist’ strategy, though not without its own drawbacks (Chatterjee Citation2022).

Perhaps most importantly, scholars have identified India as an emergent world power that brings a powerfully strategic orientation to harnessing international institutions of trade and investment for national priorities. Hopewell (Citation2016) argues that India, along with China and Brazil, proactively challenged the hypocrisies of the Western global trading system in the course of negotiations of the Doha Development Round of the GATT. Analysing India in comparative international perspective, Sinha (Citation2016) explored how the government augmented domestic institutional and bureaucratic capacities that allowed India to participate actively and assertively in the WTO. This suggests that India has sufficient state capacity and strategic orientation to use international institutions and incentives for domestic industry in order to augment industrial development, in a manner not unlike the triple alliances at the heart of dependent development 50 years ago. We might consider the capacities and strategic engagement of the Indian state, along with multinational interlocutors, as at least plausibly operating according to this logic.

The actual outcomes in terms of industrial development, however, are less sanguine. Manufacturing value added as a proportion of GDP has stagnated, with an average of 16.2 in the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s and an average of 15.8 between 2000 and 2019; the dramatic increases in FDI in India in the twenty-first century thus have not translated into transformations in industrial production. Even if we acknowledge the significant proportion of that FDI directed towards services, particularly in technology and business processing, we would still expect at least a moderate increase, as the Indian state might try to direct FDI towards value-added activities, particularly in key sectors such as pharmaceuticals, automotive products and chemicals. What could explain why increased FDI has not led to a greater proportion of manufacturing value added in national output, as the dependent development model might suggest?

Changes in domestic and international political economy since the 1990s have precluded the positive-sum dynamics resulting from a triple alliance among national states, multinational corporations and the domestic private sector. In what follows, I will present some suggestive evidence of these constraints, particularly technologically complex and externally embedded sectors, in terms of both domestic political economy and the international regimes of trade and investment in the twenty-first century.

The strategic orientation of the Indian state?

While NIC governments in East Asia (and, earlier, Latin America) formed strategic relationships with multinationals and domestic firms during a time of significant state intervention and direction of the economy, countries like India saw significant increases in FDI only after economic liberalisation, when the state’s key instruments to control domestic capital and bargain with international capital have been greatly diminished. This is, in turn, implicated in bureaucratic authoritarianism, whereas India has been a democracy since 1951, with the exception of the 1975-1977 Emergency. Although dependent development was strongly associated with authoritarian rule in the 1970s, there is no reason why it cannot exist with democracies in the twenty-first century; the biggest threat to investment was from organised workers, but neoliberal reform from the 1990s has fundamentally eroded the independent power of workers to make claims on profits or public resources. Even while acknowledging domestic institutional weaknesses, the timing of opening up and inflows of investment has critically limited the ability of the state to effect the dynamics of dependent development and of the triple alliance for industrial growth.

This is most obvious in the dramatic global decreases in trade protection in the 1990s, associated with the accession of many developing countries to the WTO; in 1992, average weighted Indian tariffs for all products and manufactured products was 27 and 42%, respectively; by 2005, they were 13.9 and 12.7%; and in 2018, they were 4.9 and 6%. Particular sectors, such as vehicles, retained significant tariffs and non-tariff barriers. But the Uruguay Round and its aftermath represented a seismic reduction of formal barriers of trade protection, which then removed a major incentive among multinationals to use developmentalist FDI to gain access to valuable domestic markets protected by trade barriers. Further, trade-related investment measures eroded the necessity of engagement with domestic capital in joint ventures; currently, the only sectors that require government approval (above a certain amount) for FDI are in air transport services, brownfield investments in pharmaceuticals and biotechnology, broadcasting content, defence, digital media, mining, multibrand and food products retail trading, petroleum refining, print media and telecommunications (see Invest India Citation2001). Thus, the government cannot dangle approval for international investment as a bargaining chip to enforce local content requirements that might facilitate technology transfer.

More subtly but no less impactfully, liberalisation removed finance from quotidian state control, thus making it almost impossible for the state to discipline local capital and bring it into productive alliances with multinationals. While much of the Indian banking system has remained under state ownership, the incentives of financiers are to pursue investments with the largest returns given risk, rather than following long-term social mandates. Further, the development of equities markets and portfolio investment over the last three decades has further impeded the government’s ability to strategically direct capital, which was an important feature of the East Asian experience (Naseemullah Citation2017, 135–176).

This is not of course to suggest that the Indian state, and the elected governments that rule it, do not influence the direction of capital and investment, but rather to argue that they tend to do this in a non-strategic fashion. Much of the oligarchic wealth in post-liberalisation India is implicated in rent-thick sectors – such as mining, telecommunications and energy – over which government licences and active support are necessary (Gandhi and Walton Citation2012). The Modi government since 2014, despite coming into power on the basis of sound and proactive economic management, has directed resources through public contracts toward favoured conglomerates in areas such as infrastructure development and public services, while largely pursuing a not particularly strategic deregulatory agenda, such as loosening labour protections (Findlay and Lockett Citation2020). Thus, while the Indian state certainly maintains some resources and instruments that could be deployed in the service of an outward-oriented industrial policy – as well as organisations like sector-specific export promotion agencies – the actual interests and incentives of the state, in the context of a pervasive political economy of rent-seeking, militates against strategic bargaining and the disciplining of capital in the service of forming triple alliances.

Linkages between multinational and local capital

The absence of the strategic direction of the state might by itself doom the prospects for effective triple alliances. But multinationals have also independently engaged with local firms in ways that represent enduring constraints for the pursuit of activist industrial policy. In other words, even if the Indian government at the national level or particular governments at the state level were able to formulate and implement a more strategic orientation in its relationships with multinationals and domestic capital, the persistent influence of relationships between multinationals and domestic firms, and the latter’s integration into global value chains in the 1990s, are likely to circumscribe the possibilities for triple dependent development. An exploration of the international integration of two successful industries in India with contrasting trajectories – pharmaceuticals and automotives – illustrates these issues.

The automotive industry in India began global integration before liberalisation and the Uruguay Round reforms, at a time when multinationals had to bargain for domestic market access. The Tariff Commission report (Government of India Citation1953) ordered that companies wishing to remain in operation in India would have to localise their production in a phased process over three years if they were to receive manufacturing licences. This led foreign firms with assembly operations to leave India, based on assessments that the internal market was too small to sustain local production. In their place, three domestic companies established production facilities under government licence. Between the 1950s and 1970s, cars like the Ambassador were the only cars on Indian roads.

In the 1980s, however, the automotive industry was transformed through government intervention to promote locally manufactured and affordable passenger cars. In 1983, the government chose Suzuki as the joint venture partner for its own failing government car enterprise, Maruti Udyog (Venkataramani Citation1990). The choice of Japanese multinationals as partners by the state was a deliberate and strategic one. Japanese systems of ‘lean production’ were better able to capture the gains from technology by decentralising manufacturing and encouraging subcontracting, collapsing hierarchies and encouraging worker participation, and minimising inventory through ‘just-in-time’ production (see Womack, Jones, and Roos Citation2007, ch. 3). The flexibility of production and scale of more compact Japanese cars were attractive for developing countries (see DCosta Citation1995). Suzuki was interested because of the crowding of the Japanese domestic market and thus the necessity for overseas expansion through exports and FDI, facilitated by government agencies like MITI (Venkataramani Citation1990, 30–41). The Maruti Udyog-Suzuki collaboration was a tremendous success: the smaller, lighter and thus more fuel-efficient and cheaper Maruti 100 car was able to achieve 75% market share in the passenger car segment over the next decade (Krishnan Citation1996, 2t). The Maruti-Suzuki collaboration led to an exponential increase in and development of domestic component manufacturers – many of whom are successful exporters – which represents a key indicator of industrial autonomy. Other multinational original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) actively sought joint ventures with established Indian companies as a way of entering the Indian market, following the patterns of dependent development. By the mid-1990s, there were upwards of 10 international OEMs from the US, Europe, Japan and Korea present in India. Most entered the market through joint ventures with established domestic concerns, and relied on a vibrant domestic industry in high-quality components.

While government licensing requirements have been largely eliminated, the incentives for localising technology and the production of components have remained, for three reasons. First, the Indian government has continued to levy relatively high tariffs on importing wholly built cars. Second, because of the lower incomes of Indian consumers, firms must sell their vehicles at lower prices than in home markets, and incorporating domestically produced components drives down costs. As a result, both international and domestic OEMs have strong incentives to maintain domestic supplier networks. Third, vehicles and especially components must be adapted to climatic and road conditions in South Asia, which requires substantive collaboration. Thus, while the automotive industry in India might seem to contradict the demise of dependent development as a viable framework, the timing of international integration and the particular features of the industry are key (and perhaps unique) explanatory factors for its viability.

The Indian pharmaceutical industry has, meanwhile, followed a different trajectory towards international integration. While widely recognised as one of India’s most vibrant and internationally competitive sectors – the Serum Institute of India was a key global producer of the COVID-19 Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine – it has not maintained the level of industrial autonomy that represents a key goal of dependent development. Its firms have instead established tight, hierarchical relations with multinationals, largely as a result of the WTO’s rules on intellectual property.

Pharmaceutical production in India, particularly of more technology-intensive ingredients, began with a dramatic break from the international system towards the establishment of a horizontal import-substitution regime that was quite successful in developing the infant industry, even without multinational cooperation. Industrial Policy Resolutions of 1948 and 1956 had encouraged the participation of foreign capital in the industry because of the need for foreign technology (Barnwal Citation2000, 13, 30). As a result of hospitable policies encouraging foreign investment, multinationals dominated the pharmaceutical industry through the 1960s, first importing medicines for direct sales, and then importing active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) from the parent company for formulation in India, often at very high internal prices (Barnwal Citation2000, 59).

The passage of the Patent Act of 1970 by Indira Gandhi’s Congress government transformed the industry. This legislation eliminated patent protection for pharmaceutical products while maintaining patent protection for manufacturing processes (Mehrotra Citation1987, 1461). It enabled commercial production of a drug molecule patented abroad if that molecule could be manufactured through different industrial processes. It also spurred process-based and drug delivery innovation in India, and prevented multinationals from maintaining market monopolies of APIs imported from the parent company. The revision of the patent laws enabled private industry to establish sustainable indigenous production. Observers have argued that the modified Indian patent regime after 1970 was the principal cause of the surge in local control of Indian domestic market-share, and the dynamism of Indian companies in both APIs and downstream formulations, at much cheaper prices than the multinationals.

The dismantling of the process patent regime began with the trade policy conditionalities of structural adjustment associated with the 1991 liberalisation (Chossudovsky Citation1993, 385). As a precondition of India’s accession to the WTO on 1 January 1995, the government agreed to revise its patent laws by 2005. Provisions included replacing the process patent regime with product patents, establishing an automatic ‘black-box’ process for patent applications from abroad, increasing the duration of patent protection from seven to 20 years and guaranteeing exclusive marketing rights for patented goods (Dasgupta Citation1999, 988).

With the restructuring of the industry, we have seen the emergence of an unequal dual alliance between multinationals and domestic firms operating in export markets, to the exclusion of the state’s developmental objectives (see Shadlen Citation2017). The independence of India from the patent regime for a quarter-century allowed firms to build substantial research and sophisticated production capacities. This has, in turn, allowed multinationals to integrate Indian firms into global value chains. A number of India’s largest pharmaceutical firms manufacture patented drugs under licence from global multinationals; multinationals benefit from lower costs, while protecting monopoly prices as returns to protected intellectual property. These firms also conduct research in drug delivery – including conducting randomised controlled trials in Indian hospitals – because of lower costs, but multinationals, and not their local partners, own the resulting intellectual property. As a result, major pharmaceutical companies have thrived, but at the expense of autonomy from multinational investment (Kapstein and Busby Citation2013). Most major Indian manufacturers are much more dependent on multinationals and are thus more likely to conform to international norms and standards.

Is the Indian economy as a whole more like the pharmaceutical industry, in which multinationals have more recently integrated the sector into global value chains to the exclusion of nationalist objectives, or the automotive industry, in which earlier patterns of integration have retained some features of the triple alliance and dependent development? Circumstantial evidence suggests that the former represents the dominant pattern, at least relative to earlier developers that were able to take advantage of strategic negotiation, and construct triple alliances, around the terms of developmentalist FDI. The proportion of high-technology exports in total manufactured exports, a key measure of the success of export-led industrialisation, averaged just 8.2% between 2009 and 2018, following at least two decades of dramatic inward FDI; Korea’s proportion during the same period was 31.1%. How might we explain such a dramatic difference in national outcomes?

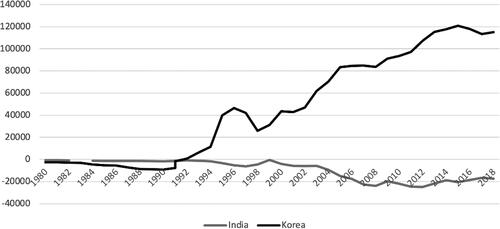

Korea has been able to maintain relative autonomy from international regimes of investment and intellectual property protection, as a result of strategic engagement with multinationals and domestic capital in the decades before the formation of the WTO, while India saw dramatic increases in inward FDI only after these new regimes were established. presents the difference between resident and non-resident patents registered in national intellectual property agencies over time; non-resident patents reflect multinationals’ efforts in registering and protecting their intellectual property in host and foreign countries, while resident patents reflect the protection of domestic innovation.

In the 1980s, India and Korea had comparable measures. But from the mid-1990s, Korea has dramatically increased its resident patents relative to non-resident patents, whereas India has seen non-resident outpace resident patents. While there are significant differences in both state capacity and industrial structure between the two countries that preconfigure both the nature and the timing of international integration, as discussed above, these differences are expressed in the different means by which FDI and the relationship between domestic and international capital can be deployed for industrial development.

***

India is a developing country with perhaps the best possible chance of being able to derive benefits from engagement with multinationals. As a member of the BRIC category, if significantly the poorest one, its growing markets of middle-class consumers have long been identified as a target for multinationals. The government has recently returned to industrial strategy in its dealings with domestic firms. One might suppose that the attractiveness of these markets and latent state capacities would lead multinationals to make more significant concessions in allowing for the localisation of production, and engage productively with domestic capital in order to further positive-sum objectives. One might also assume that a deep if implicit sense of economic nationalism among bureaucrats and politicians, which has limited the reform and opening up of the economy relative to peers in developing countries, might allow for greater strategic negotiation over localisation and market access.

This has not come to pass, however, for two reasons. First, core capacities of the state in directing industry – particularly the disciplining of finance for productive purposes (Thurbon Citation2016) – have been liberalised, such that firms are subject to the dictates of the market rather than the direction of the state. This means that local capital is less likely to be allied with the state in strategic negotiations with multinationals, and multinational and local capital are more likely to have aligned interests in a perverse dual alliance embodied in global value chains. Second, the political interests of the state and those of the democratic governments that govern it are not oriented in a particularly developmental direction. Electoral imperatives lead governments to disburse rents to elite allies and client constituencies, constraining the resources available for industrial policy (Naseemullah Citation2017, 90–95). Since 2014, Modi’s explicitly nationalist government, although commanding significant majorities and centralising political and bureaucratic authority, has largely focused its efforts on stimulating spending on infrastructure, supported by public-sector banks (Chandra and Walton Citation2020). This suggests a lack of the concerted attention required for strategic negotiation with multinationals as a key component of industrial policy and the formulation of a triple alliance, led by the state, with multinationals and with domestic capital.

Conclusion

This article has argued that activist industrial policy needs to pay attention to the power of a neglected actor, that of multinationals, in relation to the state and domestic capital. In the process of intervening to transform industrial outcomes in the developing world until the 1980s, the possibility of mutually beneficial relationships between states, multinationals and local firms, predicated on strategic bargaining driven by the state’s developmentalist objectives, arose. Evans and other scholars framed ‘dependent development’ as a defining feature of industrial development in Latin America (and East Asia) from the 1960s to the 1980s and posited the triple alliance as the core of positive-sum, developmentalist engagements. This paper emphasises the historical and regional specificity of the dependent development framework, which enabled state actors to strategically negotiate with multinationals, and discipline domestic firms, over the terms of investment. After the neoliberal turn and globalisation in the 1990s, states became significantly less powerful and autonomous relative to multinationals; this has continued in the twenty-first century, despite the increased incoherence of the multilateral order and the rise of alternative structures like the BRI. Though we see differences in outcomes by sector, countries like India face a much more difficult challenge in securing and maintaining autonomous development today than NICs in earlier periods did.

What does this mean for industrial policy? First, garnering domestic capacity and authority might be necessary but is unlikely to be sufficient for securing industrial development over the long term, at least following past practices. Even countries like Brazil with active and rejuvenated statist traditions, supporting national champions, have not seen such domestic industrial policy translate into transformative industrial success (see Kröger Citation2012; Hochstetler and Montero Citation2013). In countries like India, where liberalising reform has been accompanied by a political economy of rent-seeking and cronyism, the sense of purpose required for strategic negotiations with multinationals and domestic capital is lacking. The external environment and the institutional structure of global markets are also important. Specifically, developing countries face a more adverse context in securing benefits from FDI, because of both the absence of key instruments domestically and changes in the trade and investment regimes globally. These challenges have not receded over the last two decades, despite the rise of China and the stagnation of the WTO, signifying path-dependent trajectories. These adversities need to be acknowledged and confronted.

Second and relatedly, developing countries that seek to implement industrial policy must adopt strategies to respond to these constraints. Some governments in developing countries will undoubtedly continue to seek to maximise their advantage relative to other countries within extant rules and frameworks; it is certainly in the interest of multinationals to encourage this competition, among developing countries. And such competition will mean that only some countries, often those with structural advantages that make them attractive for multinationals, will succeed. Alternatively, developing countries could collectively confront the excesses of rules like intellectual property and investor protection that foreclose autonomous development. These rules were formulated at a time of greater consensus (or hegemony) over the international economy. Nearly 30 years later, there may be greater scope for revising these rules such that the relative returns from production on one hand and intellectual property and branding on the other are rebalanced.

Lastly, we may need to recognise dramatic recent changes in the global economy and international politics that challenge key assumptions of what successful developmentalism looks like. The coronavirus pandemic and its aftermath have signalled key weaknesses in supply chains that represent the very viscera of the globalised production that heightens the zero-sum nature of development. Even successful developers, like Korea, are facing increasing inequality and crushing household debt, as reflected in evocative illustrations like Parasite and Squid Game. And the bureaucratic-authoritarianism and violent political repression, particularly of workers, that was closely associated with the developmental state in East Asia and the dependent development phase of Latin American NICs is a normatively dubious proposition. It may be that a true new developmentalism requires balancing a single-minded focus on growth based on competitiveness in international markets with enabling capabilities of a majority of citizens to live lives consistent with their needs, desires and principles (Sen Citation1999). It must also mean a much greater focus on environmentally sustainable production, given the existential threat of climate change and its need to dramatically reduce the carbon that has fuelled both globalisation and developmentalism.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks the participants of a virtual workshop on industrial policy held in 2020, Jojo Nem Singh and two anonymous reviewers for their insights and suggestions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Correction Statement

This article was originally published with errors, which have now been corrected in the online version. Please see Correction (http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2023.2236873).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Adnan Naseemullah

Adnan Naseemullah is Senior Lecturer in International Relations at King’s College London, and the author of Development after Statism (Cambridge, 2017) and Patchwork States (Cambridge, 2022). His research focuses on the political economy of national and international development, state formation, political order and violence, electoral politics and populism.

Bibliography

- Akamatsu, Kaname. 1962. “A Historical Pattern of Economic Growth in Developing Countries.” The Developing Economies 1: 3–25. doi:10.1111/j.1746-1049.1962.tb01020.x.

- Amsden, Alice. 1989. Asia’s Next Giant. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Amsden, Alice. 2003. “Good-Bye Dependency Theory, Hello Dependency Theory.” Studies in Comparative International Development 38 (1): 32–38. doi:10.1007/BF02686320.

- Barnwal, Bijay. 2000. Economic Reforms and Policy Change: A Case Study of the Indian Drug Industry. Delhi: Classical Publishing.

- Barton, John, Judith Goldstein, Timothy Josling, and Richard Steinberg. 2008. The Evolution of the Trade Regime. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Bennett, Douglas, and Kenneth Sharpe. 1985. Transnational Corporations versus the State. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Brooks, Douglas, and Jayant Menon. 2008. Infrastructure and Trade in Asia. Tokyo: Asia Development Bank Institute.

- Cardoso, Fernando, and Enzo Faletto. 1979. Dependency and Development in Latin America. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Chandra, Rohit, and Michael Walton. 2020. “Big Potential, Big Risks? Indian Capitalism, Economic Reform and Populism in the BJP Era.” India Review 19 (2): 176–205. doi:10.1080/14736489.2020.1744997.

- Chatterjee, Elizabeth. 2022. “New Developmentalism and Its Discontents: State Activism in Modi’s Gujarat and India.” Development and Change 53 (1): 58–83. doi:10.1111/dech.12579.

- Chenery, Hollis. 1969. “The Two-Gap Approach to Aid and Development.” American Economic Review 59 (3): 446–449.

- Chossudovsky, Michel. 1993, March 6. “India under IMF Rule.” Economic & Political Weekly 28: 385–387.

- Chibber, Vivek. 2003. Locked in Place. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Chimhowu, Admos, David Hulme, and Lauchlan Munro. 2019. “The ‘New’ National Development Planning and Global Development Goals.” World Development 120: 76–89. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.03.013.

- Cumings, Bruce. 1984. “The Origins and Development of the Northeast Asian Political Economy.” International Organization 38 (1): 1–40. doi:10.1017/S0020818300004264.

- Collins, Michael. 2008. “New Trade Deal with Mexico, Canada Borrows Heavily from Pact That Trump Abandoned.” USA Today, October 3.

- D’Costa, Anthony. 1995. “The Restructuring of the Indian Automobile Industry: Indian State and Japanese Capital.” World Development 23: 485–502.

- Dasgupta, Biplab. 1999. “Patent Lies and Latent Danger.” Economic & Political Weekly 34: 979–993.

- Djankov, Simeon, and Sean Miner. 2016. China’s Belt and Road Initiative. Washington, DC: Peterson Institute.

- Edwards, Hayley. 2016. Shadow Courts. New York: Columbia Global Reports.

- Evans, Peter. 1979. Dependent Development. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Evans, Peter. 1987. “Class, State and Dependence in East Asia: Lessons for Latin Americanists.” In The Political Economy of the New Asian Industrialism, edited by Frederic Deyo. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Evans, Peter. 1995. Embedded Autonomy. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Findlay, Stephanie, and Hudson Lockett. 2020. “‘Modi’s Rockefeller’: Gautam Adani and the Concentration of Power in India.” The Financial Times, November 13.

- Flynn, Sean, Brook Baker, Margot Kaminski, and Jimmy Koo. 2012. The US Proposal for an Intellectual Property Chapter in the Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement. American University International Law Review 28:105.

- Gandhi, Aditi, and Michael Walton. 2012. “Where Do India’s Billionaires Get Their Get Their Wealth?” Economic and Political Weekly 47 (40): 10–14.

- Gereffi, Gary. 1982. The Pharmaceutical Industry and Dependency in the Third World. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Gereffi, Gary. 2014. “Global Value Chains in a Post-Washington Consensus World.” Review of International Political Economy 21 (1): 9–37. doi:10.1080/09692290.2012.756414.

- Gereffi, Gary, and Peter Evans. 1981. “Transnational Corporations, Dependent Development, and State Policy in the Semiperiphery.” Latin American Research Review 16 (3): 31–64.

- Gerschenkron, Alexander. 1962. Economic Backwardness in Historical Perspective. New York: Praeger.

- Gold, Thomas. 1986. State and Society in the Taiwan Miracle. New York: ME Sharpe.

- Government of India. 1953. Report of the Tariff Commission on the Automobile Industry. New Delhi: Udyog Bhavan.

- Gunder Frank, Andre. 1967. The Development of Underdevelopment. New York: New Left Books.

- Haggard, Stephan. 1990. Pathways from the Periphery. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Hirschman, Albert. 1968. “The Political Economy of Import-Substituting Industrialization in Latin America.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 82 (1): 1–32. doi:10.2307/1882243.

- Hirschman, Albert. 1970 [1945]. National Power and the Structure of Foreign Trade. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Hochstetler, Kathryn, and Alfred Montero. 2013. “The Renewed Developmental State." Journal of Development Studies 49 (11): 1484–1499. doi:10.1080/00220388.2013.807503.

- Hopewell, Kristen. 2016. Breaking the WTO. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Invest India. 2001. “FDI Rules.” Delhi: National Investment Promotion and Facilitation Agency. https://www.investindia.gov.in/foreign-direct-investment

- Jiang, Yang. 2013. China’s Policymaking for Regional Economic Cooperation. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Johnson, Chalmers. 1982. MITI and the Japanese Miracle. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Kapstein, Ethan, and Joshua Busby. 2013. AIDS Drugs for All. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Klingler-Vidra, Robyn. 2018. The Venture Capital State. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Kohli, Atul. 2004. State-Directed Development. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Krishnan, Viswanathan. 1996. “Indian Automotive Industry.” IMVP Working Papers. 22 (34): 1461–1465.

- Kröger, Markus. 2012. “Neo-Mercantilist Capitalism and Post-2008 Cleavages in Economic Decision-Making Power in Brazil.” Third World Quarterly 33 (5): 887–901. doi:10.1080/01436597.2012.674703.

- Lenin, Vladmir. 1917. “Imperialism: The Highest Stage of Capitalism.” https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1916/imp-hsc/

- Lewis, Meredith. 2011. “Trans-Pacific Partnership: New Paradigm of Wolf in Sheep’s Clothing.” Boston College International & Comparative Law Review 34: 27.

- Morrissey, Oliver, and Yogesh Rai. 1995. “The GATT Agreement on Trade Related Investment Measures.” The Journal of Development Studies 31 (5): 702–724. doi:10.1080/00220389508422386.

- Mehrotra, N. N. 1987, August 22. “Indian Patents Act, Paris Convention and Self-Reliance.” Economic & Political Weekly, 24.

- Naseemullah, Adnan. 2017. Development after Statism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Nem Singh, Jewellord, and Jesse Ovadia. 2018. “The Theory and Practice of Building Developmental States in the Global South.” Third World Quarterly 39 (6): 1033–1055. doi:10.1080/01436597.2018.1455143.

- O’Donnell, Guillermo. 1988. Bureaucratic Authoritarianism. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Paus, Eva. 2012. “Confronting the Middle-Income Trap.” Studies in Comparative International Development 47 (2): 115–138. doi:10.1007/s12116-012-9110-y.

- Schwartz, Herman. 2017. “Club Goods, Intellectual Property Rights, and Profitability in the Information Economy.” Business and Politics 19 (2): 191–214. doi:10.1017/bap.2016.11.

- Sen, Amartya. 1999. Development as Freedom. London: Penguin.

- Shadlen, Ken. 2005. “Exchanging Development for Market Access? Deep Integration and Industrial Policy under Multilateral and Regional-Bilateral Trade Agreements.” Review of International Political Economy 12 (5): 750–775. doi:10.1080/09692290500339685.

- Shadlen, Ken. 2017. Coalitions and Compliance. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Sinha, Aseema. 2016. Globalizing India. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Thurbon, Elizabeth. 2016. Developmental Mindset. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Wade, Robert. 1990. Governing the Market. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Wade, Robert. 2003. “What Strategies Are Viable for Developing Countries Today?” Review of International Political Economy 10 (4): 621–644. doi:10.1080/09692290310001601902.

- Womack, James, Daniel Jones, and Daniel Roos. 2007. The Machine That Changed the World. New York: Simon and Schuster.

- Woo-Cumings, Meredith. 1991. Race to the Swift. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Woo-Cumings, Meredith, ed. 1998. The Developmental State. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Venkataramani, Raja. 1990. Japan Enters Indian Industry: The Maruti-Suzuki Joint Venture. Delhi: Radiant Publishers.

- Yeung, Henry. 2016. Strategic Coupling. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.