Abstract

Through a discourse-theoretic approach, this paper problematises the under-theorised chameleonic quality of populism. While populist politics is often expressed as construction of the people against the elite, this paper argues that the political should rather be sought in how populism revives itself despite (and through) constant discursive shifts. It examines the interrelations between populism, identity and foreign policy, inserting ‘dislocation’, the transitory moment of disruption in the discursive field, as the main enterprise of populist politics. Empirically, the paper scrutinises how Turkish President Erdoğan switched from conservative democratic to Islamist to nationalist discourses, each with repercussions in the field of foreign policy, and sustained the populist moment through successive dislocations. In particular, it focuses how the ‘Ottoman’ myth spelled different populisms and foreign policy discourses in different periods of the Justice and Development Party (Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi – AKP) rule.

Keywords:

If we want things to stay as they are, things will have to change.

(Di Lampedusa Citation1960, 31)

In August 2013, Egyptian security forces killed hundreds of Muslim Brotherhood supporters who were camping out in Rabaa al-Adawiyya Square, Cairo, to protest the military coup against President Mohammad Morsi. Rabaa soon became a rallying call for Islamist movements across the Middle East. A group of Turkish activists inspired by this cry created the Rabaa sign, a hand with four fingers extended, referring to its literal meaning ‘the fourth’ (). Turkish President Tayyip Erdoğan, the fiercest international critic of the Egyptian crackdown, popularised this hand gesture to show solidarity with Morsi supporters. Rabaa alluded to his undeclared affiliation with the Muslim Brotherhood, as well as his Islamist expansion efforts to back them in various post-‘Arab Spring’ countries and establish a new, Turkish-led Sunni order in the Middle East.

Figure 1. The Rabaa sign.

(Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Rabia_sign.svg)

In an ironic twist, soon after mid-2015, Turkey’s neo-Ottoman dreams in the region and hopes for a Kurdish resolution at home faded, and the Rabaa sign acquired a completely different meaning. It was adjusted to suit to the new political climate and dislocated from an Islamist discourse to a nationalist one with overtly ethnic appeals and no direct emphasis on religious values. Now, the four fingers symbolised the key principles of Erdoğan’s Justice and Development Party (Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi – AKP): ‘one nation, one flag, one homeland, one state’. This motto was adopted as a new article in the party bylaws (AK Parti Citation2019, 25) and Erdoğan, together with his audience, recited it at the end of each rally to garner support for Turkey’s successive military operations against Kurdish political formations within and beyond its borders.

The limits to foreign policy changes are very much imposed by regional and global power structures, as well as the thickness of the ideological elements. Nevertheless, populism, known for its ‘essential chameleonic quality’, always assimilates ‘the hue of the environment in which it occurs’ (Taggart Citation2000, 4). Populists may conveniently take on the colour of their surroundings based on changing power calculations, as reflected in the divergent uses of the same Rabaa sign in the hands of Turkey’s populist leader. This chameleon-like characteristic of populist actors in both domestic and foreign policy has already been empirically shown in the literature (Mikucka-Wójtowicz Citation2019; Muis Citation2015), though it still awaits extensive theorisation. This study problematises the oft taken-for-granted elusiveness and ‘empty shell’ composition of populism, and essentially argues that populism indeed sustains and re-generates itself through this volatile change.

Despite the extensive conceptual debate over populism, definitions agree on two of its components: anti-elitism (the antagonistic framework dividing a society vertically between the people and the elite) and people-centrism (politics as the expression of the general will and demand to restore popular sovereignty) (Aslanidis Citation2016). Due to its elusiveness, populism can only be identified in its outcomes. This article particularly examines its implications in foreign policy. In the scholarship on populism, the ‘people vs elite’ binary has largely been studied within a national boundary. Nevertheless, identities are constantly negotiated, challenged, and restated through discursive practices, including articulations of foreign policy. The purpose here, then, is not to identify and explain state behaviours, but to demonstrate the populist logic of this ‘co-constitutive’ relationship between representations of ‘the people’ and foreign policy (Hansen Citation2006, xii). Moreover, it is also a fruitful exercise to study chameleonic change in a field where such dramatic shifts are less expected since foreign policy is relatively insulated from other governmental agencies and largely rests on established principles and diplomatic traditions.Footnote1

Studies exploring the existence of a populist foreign policy vary widely, from an outright rejection of its reification (Balfour et al. Citation2016) to several categorisations of its sub-types (Chryssogelos Citation2021; Verbeek and Zaslove Citation2018).Footnote2 In particular, different conceptual genera lead to different research questions in the study of foreign policy. The ideational approach, for instance, defines populism as a thin ideology and primarily seeks to answer the ‘what’ question, such as the populist elements in foreign policy formulation and their measurement (Liang Citation2007; Mudde and Kaltwasser Citation2017; Verbeek and Zaslove Citation2018). The strategic approach considers populism a political strategy and tends to deal with the ‘why’ question, focusing on populist leadership and mobilisation in foreign policy decision-making (Weyland Citation2001). Lastly, the discourse-theoretic approach defines populism as a political logic, denying any substance to the phenomenon, and shifts the focus from the contents of populism to how populism articulates those contents (De Cleen and Stavrakakis Citation2017; Laclau Citation2005a). Consequently, it pursues the ‘how’ question behind foreign policy discourses.

This article, too, adopts a discourse-theoretic approach to understand the interrelations between populism, identity and foreign policy. Nevertheless, it first challenges the static conceptions of ‘populist foreign policy’ and discusses the neglected foreign policy change in populist settings. Populist variations should not only be sought across space in the multiple sub-types of foreign policy, but also across time in its re-orientations within a single case. Second, this study uses the foreign policy debate as an entry point to understanding populist politics in broader terms. References to the chameleonic quality of populism are not scant in the academic literature, but it is instead seen in the diversity of forms and ideologies populisms can adopt across the world (e.g. Aslanidis Citation2016, 89; Bonikowski et al. Citation2019, 60). This article explicitly focuses on how populism of the same populist leader, political party, or movement may shape-shift over time, depending on the context. While populism is often understood as the construction of the people against the elite, this article argues that the political should rather be sought in how populism revives itself despite (and through) constant shifts and disruptions in the discursive field. For this task, it, third, seeks to unearth the constitutive role of ‘dislocation’ in Laclauan terms along the identity-foreign policy nexus that is central to the making and unmaking of the populist moment (Laclau Citation1990). It revisits the concept and calls for further de-essentialisation and dynamisation to better grasp the volatility of populism.

Turkish populism aptly illustrates the constant foreign policy shifts under populist rule. Erdoğan has attracted much scholarly attention as one of the forerunners of the current populist wave, and the AKP rule since 2002 offers a broad timespan for researchers to investigate the populist impact in foreign policy as a site of constant power struggles and dramatic discursive shifts (Alpan Citation2016; Balta Citation2018; Yalvaç and Joseph Citation2019). Although the scholarship refers to the AKP (and Erdoğan) as a singular, coherent actor, there have actually been multiple AKPs since its inception in 2001. The party is in constant flux. Depending on volatile political contexts and power calculations, the party self-admittedly wriggles out of its old skin, as evidenced by major policy shifts and constant changes even to the list of its founding members (Hacısalihoğlu Citation2017). Pointing to this ever-changing state of the party’s identity, the article empirically clarifies how Turkish populism, as performed by the AKP, has articulated different foreign policy discourses – be they liberal international, Islamist or Turkish nationalist – while maintaining continuity under the populist umbrella.

To this end, the article opens up the basic tenets of the Laclauian approach to populism, discusses the central role of dislocation in retaining the populist moment, and offers a revisionist take on the concept. With that theoretical framework, the article moves to illustrate the AKP’s shifting discourses from conservatism to Islamism to nationalism, as reflected in identity and foreign policy. In particular, it focuses on how the ‘Ottoman’ myth spelled different populisms and foreign policy discourses in different periods of AKP rule. This paper focuses on the time frame from 2002 to 2021 and analyses official foreign policy texts, newspapers, and academic and popular writings.

The populist configuration of politics and the constitutive role of dislocation

The elusiveness and vagueness of populism have led many academics to challenge the analytical value of the term and even avoid using it altogether (Herkman Citation2017, 471). However, it is exactly this elusiveness that brings populist politics into existence and enables it to accommodate multiple heterogeneous social demands that otherwise would not join. In Laclau’s words, ‘Populism's relative ideological simplicity and emptiness, […] which is in most cases the prelude to its elitist dismissal, should be approached in terms of what those processes of simplification and emptying attempt to perform’ (Citation2005a, 14).

By its profoundly political focus, Laclau’s discourse-theoretic approach differs from others treating populism either as a symptomatic effect of some objective causes (e.g. economic globalisation, socio-cultural changes) or as a thin ideology comprising particular ideas and beliefs (Mudde and Kaltwasser Citation2017; Rodrik Citation2018). A movement cannot be labelled populist on the basis of its ideology alone, ‘but because it shows a particular logic of articulation of those contents – whatever those contents are’ (Citation2005b, 33). Populism is, rather, a logic or reason: a distinctive set of discursive features organised around constructing a collective subject, the people, and articulated through an antagonistic political frontier that pits the people (the underdog, the common man, the little man) against the elite (the establishment, the regime, the imperialists etc.). This political frontier is drawn among a multitude of indeterminate ideological elements (the floating signifiers) that can be woven into any particular ideological formation (Laclau Citation2005a, 110). The analytical fulcrum of this theory is the role of the equivalential links built between dispersed social and political demands through nodal points, privileged points of signification, and empty signifiers, voicing them as a more universal opposition against the elite as a whole.

In the infinitude of the social, such chains of equivalence are neither random nor predetermined. The populist moment is improper and unstable ‘because it tries to operate performatively within a social reality which is to a large extent heterogeneous and fluctuating’ (Laclau Citation2005a, 118). Michael Hauser pushes this point further when raising his criticism against Laclau that the signifying chains today are even more ‘discontinued, decentralized, and dispersive’, and rather appear to be a heterogeneous assemblage of semantic segments only tied with the signifier of the populist leader (2018, 74). This contingency and structural undecidability, leading to a continuous process of (re-)signification, is especially important to grasp the dynamics of change in populism. Here, dislocation occurs when the structure cannot semanticise the new, and the possibility of signification reaches its limit as a structural failure in an encounter with the Real. Once the structure is dislocated, rival forces fight for recomposition and re-signification of the nodal points (Laclau Citation1990, 40–41). This constitutes the logic of displacement of political frontiers. New political frontiers can destabilise and shift power blocs and lead to the proliferation of floating signifiers; therefore, the partially fixed moments of discourse can be tethered to disarticulations and re-articulations by rival projects (Laclau Citation2005a, 153). Dislocation is then both traumatic/disruptive and productive, serving as the ground for new identities (Laclau Citation1990, 39). As such, by making new strategies and discourses available for signification, dislocation puts forward the political agency.

In a 1993 interview, Laclau criticises his earlier emphasis on antagonism in Hegemony and Socialist Strategy and argues for the analytical primacy of dislocation, because dislocation precedes both antagonism and articulation (quoted in Stavrakakis Citation2003, 324). However, this concept almost disappears in his 2005 work on populism. With an emphasis on antagonism, the Laclauian theory of populism does not differ from his general theory of the political constitution of group identities. Thus, several scholars have called for its revision (Aslanidis Citation2016; De Cleen and Stavrakakis Citation2017). This study too adopts a revisionist approach, arguing for dislocation to be the main enterprise of populist politics. Re-inserting dislocation will contribute to exploring the peculiar dynamics of populist politics. This, however, requires a re-adjustment of the concept. Mostly associated with the organic crisis in the Gramscian approach, dislocation appears as a response to the unavoidable failure of the structure when discourse encounters the Real but reaches the limits of its meaning. However, as Benjamin Moffitt argues, crises are not objective phenomena, but both ‘mediated’ and ‘performed’ by political actors (Citation2015, 190). The study of populism, recalling its chameleonic qualities and ever-shifting chains of equivalence, requires an even more dynamic and de-essentialised understanding of dislocation that problematises the conception of the Real. More importantly, dislocation may not necessarily result from a failed structure encountering the Real. Rather, it may hint at a populist governance technique to exploit new opportunities and sustain the hegemonic moment via transformation in a volatile context. In Laclau’s words, ‘the agents themselves transform their own identity insofar as they actualise certain structural potentialities and reject others’ (1990, 30), but this is not impinged on by a failed structure. Thus, dislocation is neither objective nor necessarily a failure of the established reality. It is, rather, intradiscursive and constitutive, allowing ‘conversions of articulatory practices and accompanying shifts in public discourses, which can then be used as a platform for a hegemonic intervention’ (Nabers Citation2019, 275).

The intradiscursive dislocations as a break in hegemonic discourse may lead to floating signifiers that can be captured by counter-discourses (Stavrakakis et al. Citation2018). Nonetheless, this does not mean anything is possible, since dislocation occurs over an existing structure; it entails the reactivation of previously sedimented nodal points (Wodrig Citation2018). With this operation, some existing demands are extended or taken up in another, and some formerly excluded demands may be incorporated into the camp. After dislocutory moments enable the creation of new antagonistic frontiers, new discursive elements such as empty signifiers, fantasies or myths are also to be stimulated in order to suture the dislocated structure and conceal dislocation. They function not only as the source of diverse collective social imaginaries but also as ‘surfaces of inscription’, over which dislocations and various demands can be inscribed (Laclau Citation1990, 63–67).

Overall, one should be aware that populism is not a synonym for ‘the political’ as Laclau suggests (2005a), nor is dislocation exclusive to populism. Differently from various forms of doing politics, populism articulates the society in a vertical axis and brings up a particular set of affective appeals, such as animosity towards the elite and painting the people as the underdog (De Cleen and Stavrakakis Citation2017). As such, dislocation can be observed in non-populist politics, too,Footnote3 but it appears inherent to populism. Compared to nationalism or other ideologies, populism is ‘something political actors do, not something they are’ (Bonikowski et al. Citation2019, 63). The emptiness and lack of programmatic scope allow for an intrinsic fluidity that could be filled with shifting contents. While this populist propensity to change may not always bring actual policy change, depending on the context and power positions, it looms as a political logic to ensure continuity.

Dislocations and foreign policy changes in AKP populism

Foreign policy change can be observed at multiple levels, varying from simple policy adjustments over a single issue to fundamental re-orientations (Haesebrouck and Joly Citation2021). Numerous scholars have addressed the question of how strongly the AKP era represents a rupture in the historical course of Turkish foreign policy. This is especially true of the so-called ‘shift of axis’ debate, problematising Turkey’s increased engagement with the Middle East, along with Euroscepticism towards the end of the first decade of the 2000s (Alpan Citation2016; Kösebalaban Citation2011; Öktem, Kadıoğlu, and Karlı Citation2009; Onar Citation2016). The literature often marks a sharp distinction between pro-European Union (EU) democratic ‘good old days’ in the early years and the creeping Islamist anti-Western authoritarianism in the second half of AKP rule; however, several other studies countered this dichotomy and aimed to integrate the AKP’s strategies in continuity with the larger course of Turkish foreign policy (Hatipoglu and Palmer Citation2016; Hoffmann and Cemgil Citation2016; Özpek and Yaşar Citation2018). While the AKP’s foreign policy choices may make sense within Turkey’s broader grand strategies (Aydın Citation2020), this study observes multiple ruptures within the AKP’s foreign policy discourse. In fact, it considers the discursive dislocations a constant and constitutive element of AKP populism.

The dislocations entail re-linking disparate demands to create new antagonistic frontiers and re-signifying the elements to reach or maintain the moment. Therefore, their analysis requires us to capture the ideological elements the AKP employed in the reconfiguration of those disparate demands. These are conservatism, Islamism and Turkish nationalism, which Tanıl Bora describes as ‘three phases of the Turkish Right’ (Citation2007). In the Turkish practice, the boundaries between these three ideologies have been quite flawed, enabling diverse mutations. ‘Islamism is our water of life. Nationalism is the ice, and conservatism is the steam. All three nourish the same soil. The name of those soils is Turkey’, a pro-government columnist states, referring to this interpenetrable nature in AKP politics (Küçük Citation2017). The co-occurrence of these three ideologies generates a discursive heterogeneity, as the dislocation is never total, either. Nevertheless, in each period, one ideology comes forward as the dominant framework informing the populist discourse and foreign policy. While the populist template of the disadvantaged, inherently virtuous people against the corrupt elite holds after each dislocation, the people and the elite are re-signified each time according to those changing ideological elements.

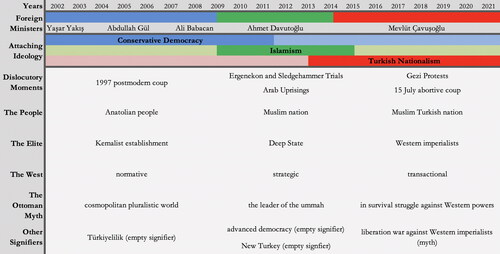

In the Turkish case, such dislocations are concealed and sutured by several empty signifiers, but mainly by the Ottoman myth, which also serves as a surface of inscription revealing the accompanying shifts. The Ottoman is the heartland of AKP populism. In AKP discourse, the glorification of the imperial era and self-flattering references to the good old times of ‘şanlı ecdad’, the glorious ancestors, are more frequent than ever, in contrast to the mainstream Kemalist conception of the Ottoman as a corrupted episode of decline (Aydın-Düzgit, Rumelili, and Topal Citation2022). AKP populism has always been all about the Ottoman; however, what the Ottoman past signifies has been dislocated multiple times. In a ‘restorative nostalgia’, this myth has selectively informed the dominant articulations of ‘the people’ in the AKP’s pursuit to revive the past (Boym Citation2001). The following analysis shows how Turkish foreign policy shifts can be read through the lens of dislocation in AKP populism, as reflected in the constant re-signification of its nodal points and myths ().

Figure 2. Dislocations and discursive shifts in the Justice and Development Party (Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi – AKP) populism.

Note: The darker colours in the attached ideologies show the dominant one in that period. The era of Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu also includes the brief tenure of Feridun Sinirlioğlu in 2015.

AKP populism as conservative democracy

The 1997 military intervention shaped much of Turkish politics in the 2000s by drawing the antagonistic front line between the ‘defensive nationalists’ and ‘conservative globalists’ (Öniş Citation2007). Along with fears that the EU accession process would grant more space to political Islam and Kurdish nationalism – the twin enemies of Kemalism – the intervention accelerated the militarisation and anti-Westernisation of secular groups. A loose but tangible form of Kemalist mobilisation called the Ulusalcı front (Ulusalcı cephe) flourished, bringing diverse actors together, such as members of Turkey’s centre-left Republican People’s Party (Cumhuriyet Halk Partisi – CHP), the far-right Nationalist Action Party (Milliyetçi Hareket Partisi – MHP), and various secular civil society associations (Çınar and Taş Citation2017). Another consequence of this intervention was the moderation of political Islam, either ideologically or tactically, in the face of state repression. The AKP founded in 2001 embodied this transformation.

Constructing politics in binary categories such as ‘state vs society’, ‘White Turks vs Black Turks’, ‘Istanbul vs Anatolia’ or ‘happy minority vs silent majority’, the AKP was built on an anti-elitist and anti-establishment discourse.Footnote4 Its populist politics was about the construction of ‘the people’ via an equivalential chain weaving together heterogeneous demands through its opposition against an illegitimate elite, ie the Kemalist political and bureaucratic elite who ran the country for decades (Ongur Citation2018; Yalvaç and Joseph Citation2019). Erdoğan popularised the term ‘CHP’s oppression’ (‘CHP zulmü’), a term characteristic of the Turkish centre-right, which marks the recent past by the perpetual victimhood of conservative Anatolian people under the oppressive secular bureaucratic elite (Milliyet Citation2014). He repeatedly expressed his scorn towards the political and cultural elite who ‘drink their whisky on the Bosphorus […] and hold the rest of the people in contempt’ (Bucak Citation2014). Likewise, he presented himself as the voice of the oppressed and gave a ‘one of us’ image when proclaiming: ‘In this country, there is segregation of black Turks and white Turks. Your brother Tayyip belongs to the black Turks’ (Özkök Citation2004). This is how AKP populism managed to present its ascendance to power as a revolution from below, compared to the top-down modernisation project of Kemalism. AKP politics performed a passive revolution by incorporating wider conservative groups into the neoliberal system (Tuğal Citation2021). This notwithstanding, it was a populist hegemonic project that claimed the space for representation of all groups disadvantaged by the Kemalist system. To that end, the AKP invented the empty signifier ‘Türkiyelilik’ (literally ‘being from Turkey’) as an all-inclusive supra-identity under which Kurds, Islamists and liberals might all find space (Hürriyet Citation2003).

To cleanse itself of Islamist stripes and achieve a legitimate standing in the national and international arena, the founders of the AKP opted for ‘conservative democracy’ modelled on the Christian Democrats in Europe. The term was coined by Yalçın Akdoğan, then-Chief Advisor to Prime Minister Erdoğan, in a key text that attempted to situate the AKP within the Western tradition of conservatism (Citation2003). While avoiding any single reference to Islamist figures such as Necip Fazıl Kısakürek, who once inspired many of the AKP cadres, Akdoğan tried to create a new genealogy and made constant references to Western thinkers such as Michael Oakeshott, Edmund Burke and Friedrich Hayek, occasionally linking them to Turkish conservative intellectuals such as Nurettin Topçu and Ali Fuat Başgil (Citation2003). Until the 1990s, a rejectionist discourse determined to combat Westoxification in politics and society was dominant among Turkish Islamists. Now, conservative democracy was taking Europe and European values as the normative framework. Integration with the Western world and embracing the plurality of society as a richness were common motives, as Erdoğan stated: ‘I want to see Turkey making a meaningful contribution to the mosaic of cultures that one observes in Europe. My motto is a local-oriented stance in a globalizing world’ (Citation2004). AKP populism articulated a cosmopolitan discourse targeting integration with Europe and the rest of the world in political, economic and cultural terms (Alpan Citation2016, 16).

In its initial years, the AKP pursued a people-centric politics of hope towards a more democratic and powerful country, while also realising a concrete agenda mostly driven by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and EU. Prior to the AKP’s ascendance to power, the declaration of Turkey’s candidacy status at the 1999 Helsinki Summit brought a wave of constitutional reforms on human rights and freedoms. Later, at the Copenhagen Summit of December 2002, the EU’s conditional decision to open accession negotiations led to widespread euphoria and an increasing belief that Turkey was destined to join the EU. This incentive of full membership resulted in the parliament passing successive harmonisation packages to fulfil the Copenhagen political criteria. Europeanisation became the main paradigm, overhauling the civil and penal codes in line with the acquis and leaving its imprints on all facets of social and political life, from civil–military relations to corruption and employment (Aydın-Düzgit and Kaliber Citation2016, 3).

While maintaining Turkey’s pro-Western orientation and European anchor in a liberal internationalist framework (Balta Citation2018), this was also the era when the AKP, with its like-minded foreign ministers Yaşar Yakış, Ali Babacan and Abdullah Gül, in succession, systematically endeavoured to de-securitise its foreign policy issues and employ its soft power assets such as economic interdependence and promoting mediation roles in regional conflicts (Altunişik and Martin Citation2011, 571). Turkish foreign policy pursued ‘active globalization’, targeting the construction of regional and global networks of shared interests (Öktem, Kadıoğlu, and Karlı Citation2009, 21). The AKP became over time more vocal in Middle Eastern affairs too. Apart from symbolic moves such as the appointment of Turkish diplomat Ekmeleddin Ihsanoğlu as the Secretary General of the Organization of the Islamic Conference in 2005, Turkey assumed mediating roles, such as during the 2008 Golan Heights conflicts and the 2009 free trade agreement between Israel and Syria (Kösebalaban Citation2011, 176; Özerim Citation2018, 173). Nevertheless, EU relations remained the top priority.

Compared to the subsequent periods, references to the Ottoman past are less frequent or explicit in the AKP’s early years under the military’s dominance over politics. Akdoğan’s book, for instance, does not even contain the word ‘Ottoman’ and instead underlines that the AKP’s political stance originates from a globally established practice, not from the past or a civilisational background (Citation2003, 6). This precautious take results from the much-contested status of history, particularly the Ottoman episode, in Turkish politics. For instance, when then-Istanbul mayor Erdoğan was removed from office in 1998, the articles on the website of the municipality, referring to Istanbul as the capital of the Ottoman-Islamic civilisation, were also removed out of fear of the military’s wrath under the shadow of the 1997 intervention (Çınar 2005, 189). Nevertheless, after the AKP came to power in 2002, its political elite occasionally used the Ottoman myth to cherish the liberal ideal of pluralism. Through references to the Ottoman millet system to manage religious and ethnic diversity, the myth signified a harmonious, plural world. Establishing 1453, the Conquest of Istanbul, as the founding moment of Turkish history, Erdoğan frequently praised the Ottoman Istanbul for hosting multiple beliefs and cultures together (ANKA Citation2008; Çınar Citation2005). This articulation enabled the AKP elite not only to frame the Western liberal principles as a home-grown idea, but also to challenge the Kemalist modernisation from a ‘legitimate’/Western vantage point for eradicating the plural texture of the society. The Ottoman practice, arguably reconciling Islam and multiculturalism, was invoked as an antidote to the Huntingtonian ‘clash of civilisation’ thesis. Reviving the Ottoman tolerance (Osmanlı hoşgörüsü), Turkey could be a beacon of co-existence in an otherwise fragmented region (Albayrak Citation2007). In the post-9/11 world, Turkey, a Muslim-majority country, becoming an EU member or co-sponsoring the United Nations ‘Alliance of Civilizations’ would further reinforce this cosmopolitan discourse. Nevertheless, as Menderes Çınar notes, this global emphasis on the AKP’s or Turkey’s Muslim identity also maintained the civilisational outlook, located Turkey as a representative of a different (Islamic) civilisation, and increased stress on Islam in the definition of Turkish national identity both at home and abroad (Çınar Citation2018, 183–184).

AKP populism as Islamism

Pinpointing when the AKP drifted away from its reformist European route to other shores is a controversy among students of Turkish politics. The variance in the breaking points offered in the academic literature, such as 2005 (Aydın-Düzgit and Kaliber Citation2016), 2007 (Alpan Citation2016), 2009 (Onar Citation2016) or 2010–2011 (Çınar Citation2018), indeed epitomises the ambivalence of Turkish foreign policy discourse that tries to articulate heterogeneous demands simultaneously.

Towards the end of the first decade of the 2000s, Turkey witnessed a dramatic power shift, challenging the long reign of the Kemalist establishment. The secularist/Kemalist hold in the military and judiciary was neutralised not only by the civilianising reforms along with the EU acquis, but also the 2008 Ergenekon and 2010 Sledgehammer Trials and 2010 Constitutional Referendum. This left the dominant party in the parliament, the AKP, without any mechanism to challenge itself (Taş Citation2015, 781). The logic of equivalence was again articulated by a populist discourse against the Kemalist elite, and more specifically its collusive networks, ie the ‘deep state’, which those trials were supposed to investigate. Nevertheless, the antagonistic frontiers were dislocated according to the change of power. Some AKP figures, more confident about the party’s electoral power and less needy of the legitimacy derived by the support of liberal intellectuals and the EU leaders, began stating that their collaboration with the liberals had ended and the new era would be different (T24 Citation2013). The new populism was given an Islamist twist that is constantly signified by elements of Sunni victimhood across the region. Inclusionary depictions of Anatolia as a mosaic culture left the discourse to a civilisational re-articulation of Turkey as a Sunni Muslim nation.

Parallel to the re-signification of the people with dominantly religious elements, the new revisionist foreign policy discourse took a Eurosceptic turn. Several external factors contributed to this discursive shift; for instance, EU actors’ repeated statements about the possibility of a ‘privileged membership’ instead of a full membership, their blockage of several negotiation chapters because of the Cyprus Conflict, and the growing Islamophobic sentiments across Europe led only to more resentment against the EU. Moreover, Turkey intended to diversify its scope and pursue alternative foreign policy paths to survive the Great Recession (2007–2009) already gripping the West. In that regard, the Arab Uprisings overhauling the Middle East appeared to be a political bonanza for Turkey to exploit the new geopolitical opportunities.

The discursive shift roughly coincides with Ahmet Davutoğlu’s appointment to the office of Foreign Minister in 2009. The new era was boldly marked by his treatise on foreign policy, Stratejik Derinlik (Strategic Depth), which outlined the blueprint of a grand vision for post-Cold War Turkey (2001). Also known as the Davutoğlu Doctrine, it meant the establishment of Pax Ottomana by invoking historical and religious connections in the formerly Ottoman territories. While EU membership was still a strategic goal, the AKP approached it purely in pragmatic terms (Alpan Citation2016). The EU now became only one aspect of Turkey’s multi-dimensional foreign policy. While this new discourse challenged the normative superiority of Europe, defining Turkey as part of another civilisation slowed down the reformist momentum. Davutoğlu’s distinction between the Western and Islamic civilisations is clearer in his dissertation Alternative Paradigms: The Impact of Islamic and Western Weltanschauungs on Political Theory (Citation1994). Here, Davutoğlu argues for essential, rather than political, differences between the two civilisational paradigms. Nevertheless, the pan-Islamist and pan-Ottoman expansionist foreign policy was balanced by a pro-Western realism (Onar Citation2016).

According to Davutoğlu, Turkey, no longer content to be a junior/regional player, had a historic mission to lead the looming transformation in its region and was destined to be a global power and a ‘central state’ due to its history. The emphasis on the ‘central state’ was an implicit and revisionist critique to the post-Cold War foreign policy assigning Turkey a passive ‘bridge’ role. This revisionist tone was later boldly manifested in the slogan ‘The world is greater than five’ that Erdoğan used at the United Nations (UN) General Assembly in September 2014, directed against the five permanent members of the UN Security Council (Al Jazeera Turk Citation2014). Turkey should be an ‘order-setter’ due to its ‘strategic depth’ that rests on two pillars: historical depth and geographic depth (Davutoğlu Citation2001). In a paper titled ‘Principles of Turkish Foreign Policy and Regional Political Structuring’, Davutoğlu also identified the basic pillars of new foreign policy as ‘rhythmic diplomacy, multi-dimensional foreign policy, zero problems with neighbors, order instituting actor, international cooperation, or proactive foreign policy’ (Davutoğlu Citation2012, 4). A zero-problem foreign policy entailed bold activism aimed at establishing economic and security co-operation with neighbours. In tandem with this policy, the new National Security Policy Document (Milli Güvenlik Siyaset Belgesi), commonly referred to as the Red Book, no longer identified Russia, Iran, Iraq and Greece as existential security threats (Kösebalaban Citation2011, 152). The other pillars, multi-dimensional foreign policy and rhythmic diplomacy, were meant to expand Turkey’s political, economic and cultural reach in a flexible and dynamic approach. To enhance Turkey’s soft power assets, several official bodies, such as the Presidency for Turks Abroad and Related Communities (Yurtdısı Türkler ve Akraba Topluluklar Baskanlığı – YTB) and Yunus Emre Institutes (Turkish cultural centres), were installed to serve this proactive foreign policy. The Turkish Cooperation and Development Agency (TİKA), providing developmental and humanitarian aid to several countries in the region, was restructured by a 2011 decree (KHK/656), increasing its geographical reach and capacity (Sevin Citation2017, 145–147).

The AKP’s work to strengthen ties with the Middle East always had an anti-Kemalist sentiment, as it responds to the Kemalist establishment’s alleged negligence of the region. Unlike the Kemalist opposition’s criticism of the government for dragging the country into ‘the Middle East swamp’, Davutoğlu elevated the region into ontological and religious status, depicted it as ‘the center of sacred revelation’, and assigned Turks a mission of re-civilising the region (Daily Sabah Citation2014). In this regard, Davutoğlu read the Arab uprisings within an Islamist framework and saw them as an opportunity to empower the suppressed Islamic groups and restore a Muslim civilisational identity to the region under Turkey’s leadership (Ozkan Citation2014).

The temporary arrest of a basically unsteady structure with an Islamist populist discourse permitted the AKP to maintain its power, but the Ottoman myth, as a surface of inscription, reveals the dislocation. What the Ottoman signified shifted from a pluralist world to the rejection of Europe as another civilisation and the leadership of the ummah. The muted Ottoman pluralism left its place to a more pan-Islamist conception that equates nation and Islam. In this re-signification and re-romanticisation of the Ottoman, its unique past grants Turkey a hierarchically superior position and the self-declared right – as well as the duty – to speak on behalf of the silenced regimes in the region. This is not a relation among Muslim fellows on an equal footing but based on an exceptionalist understanding entrusting Turkey with a historic mission: helping the oppressed in the face of plots and treachery, and rehabilitating the region suffering from the void left by the demise of the Ottoman empire. ‘As in the 16th Century, when the Ottoman Balkans were rising, we will once again make the Balkans, the Caucasus and the Middle East, together with Turkey, the center of world politics in the future’, Davutoğlu said, and set the goal of Turkish foreign policy as follows: ‘On the historic march of our holy nation, the AK Party signals the birth of a global power and the mission for a new world order’ (Bekdil Citation2015).

The AKP also tried to suture the dislocation by inventing empty signifiers, such as ‘advanced democracy’ (‘ileri demokrasi’) and ‘New Turkey’ (‘Yeni Türkiye’). Advanced democracy aimed to strip off ‘conservative democracy’ from the universal liberal norms but emphasised the distinct local roots (Alpan Citation2016). Likewise, the idea of ‘New Turkey’ as another empty signifier was put into circulation around 2010. It served as a utopia, discrete and ambivalent, but an appealing dream for all (Hürriyet Citation2013). These signifiers aimed to discursively sustain the progressive politics of hope the AKP pursued in the very beginning.

With an adamantly secularist and nationalist position, the main opposition, CHP, under Deniz Baykal, long reaped the benefits of political polarisation and did not initiate a rival hegemonic project. His successor, Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, was more compromising, as in the case of placing Ihsanoğlu as the joint candidate of the opposition in the 2014 presidential elections. Nevertheless, his modest manoeuvres to transform the party largely failed (Tuğal Citation2021, 47), and, already incapacitated by the anti-coup trials and repressive environment that followed, the political opposition generally did not succeed in building a new antagonistic line that goes beyond the old Ulusalcı articulations. The AKP’s neoliberal political and economic project, however, faced substantial resistance on the streets. From the general strike of at the Tobacco, Tobacco Products, Salt and Alcohol Enterprises (TEKEL) (2009–2010) to the 2012 Republic Day marches to the 2013 Gezi Protests (Ongur Citation2018, 51), the massive street mobilisation would challenge the AKP rule and pave the way for another shift in its populism.

AKP populism as Turkish nationalism

The 2013 Gezi protests, which began on 28 May as an environmental reaction to the demolition of Gezi Park at Taksim Square, Istanbul, exploded into mass demonstrations against the government. Leaving aside the low-hanging fruits of the so-called ‘Arab Spring’ that was soon suppressed by authoritarian regimes, the AKP elite now had to worry about the coming of the ‘Turkish Spring’ against them. With the Kemalist establishment subdued in domestic politics, Erdoğan had to demonstrate extraordinary dexterity in fashioning an elite, against which an equivalential chain among heterogeneous demands could be pitted. The elite in this new populism came from outside, ie the Western countries, global financial centres, international institutions or, overall, the international ‘mastermind’ (‘üst akıl’), which is determined to divide and conquer Turkey (Yeni Akit Citation2016). Depictions of Anatolia as a mosaic culture in the first period of AKP rule switched first to a civilisational re-signification of the people as comprising a Muslim nation, and then to a nativist articulation as a Muslim Turkish nation, which was reproduced in domestic and foreign policy realms.

The AKP was now holding the reins of state power; however, the two years from the beginning of Gezi Protests in May 2013 to the June 2015 elections, when the AKP lost the parliamentary majority for the first time, were quite challenging for the government. In addition to the continuing waves of the Gezi Protests across the country, the 17–25 December graft probe into Erdoğan’s entourage the same year and the all-out war between the Gülen Movement (GM) and the AKP put further strain on Turkish politics (Taş Citation2018). Moreover, not unrelated to Kurds’ lack of support for a presidential system, the Kurdish resolution process also came to an end following the consecutive terrorist attacks in Suruç and Ceylanpınar that killed several Kurds and policemen, respectively, in July 2015. While Erdoğan parted with earlier stakeholders – first liberals, now the Gülenists and the Kurds – he responded to the growing opposition by mobilising the myth of a liberation war against Western imperialists and its domestic pawns. Amidst shifting power blocs, this helped him consolidate his electoral base (Destradi, Johannes, and Taş Citation2022).

In his early years, Erdoğan frequently stated that he trampled on all nationalisms, and he reiterated this until 2013 (Erdoğan Citation2013). However, the rise of transnational Kurdish irredentism provided the grounds for the AKP’s new alliance with the MHP and anti-Western Kemalists around a nativist nationalist discourse (Christofis Citation2022). Ankara saw the formation of Rojava, the de facto autonomous Kurdish administration in Northern Syria, as a direct threat to its territories. In this regard, the repeated cross-border operations in Syria and Iraq punctuated a new elite pact. Yet they also sparked a rally-around-the-flag effect, which Erdoğan has effectively used in all the polls since the November 2015 general election (Çevik Citation2020a). Amidst the rising nationalist fervour, the new antagonistic frontier became most visible during the 2019 local elections, when Erdoğan designated his cooperation with the right- and left-wing ultranationalists as the People’s Alliance (Cumhur İttifakı) and the political opposition, including the Kurds and Gülenists, as the Alliance of Despicables (Zillet İttifakı) (Erdoğan Citation2019).

After Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu’s 2015 appointment as Foreign Minister, and especially following Davutoğlu’s forced resignation from his leader post in May 2016, President Erdoğan increasingly micromanaged foreign policy along with conspiratorial discourse. In the aftermath of the 15 July 2016 abortive coup, he resorted to fierce anti-Western rhetoric and strengthened its discourse of war against Western imperialists and their domestic collaborators. ‘Turkey is witnessing its biggest struggle since the war of independence’, Erdoğan warned, and called for Turks to prepare to fight for ‘a united nation, a united fatherland, a united state’ (von Schwerin Citation2017). In particular, the United States’ support for Kurdish fighters in Northern Syria against the Islamic State (ISIS) or refusal to extradite the GM's Pennsylvania-based leader Fethullah Gülen signalled varied security frameworks, among a variety of reasons (Balta Citation2018). While the AKP government increasingly took unilateral aggressive actions, such as its gas drilling activities in the Eastern Mediterranean basin, it also sought to balance the Western powers via rapprochement with Russia and China. In this period, Turkey’s purchase of the Russian S-400 air defense system was widely seen as a drifting away from its historic transatlantic security structure represented by the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). Erdoğan also occasionally brought up his intention to join the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) as an alternative to the EU; however, Turkey’s Euroasianist vision had its political limits as well due to conflicting security interests (Kubicek Citation2022).

The strategic relationship with the EU was replaced by a transactional one. As a reflection of this quid pro quo approach, Turkey once again used its geopolitical location as a gatekeeper for the EU and a buffer zone between the latter and millions of Middle Eastern refugees and militants. While immediate concerns such as the 2016 refugee deal and counterterrorism prevented European leadership from putting strong pressure on Turkey’s anti-liberal practices, such a transactional relationship helped Erdoğan’s regime sustain its legitimacy. Nevertheless, amidst the ebbs and flows of Turkish foreign relations, Erdoğan’s ambitious foreign policy activism and later efforts to save the day have resulted in a series of sharp foreign policy reversals and eventually in Turkey’s ‘precious loneliness’, which he has sought to overcome by mending fences with regional powers, especially after Citation2020 (Dalacoura Citation2021).

The dislocation can be seen again in the re-signification of the Ottoman myth. The earlier emphasis on the glory of the empire and its position as the leader of the ummah faded. As reflected in many drama series aired on pro-government TV channels during these years, the Ottoman was now signified in a defensive frame built around cult figures like Sultan Abdulhamid II as the target of Western imperialists and the nation’s survival struggle (Çevik Citation2019). Anti-Western nationalist fervour is evident in the re-signification of the people in a liberation war, as epitomised in the last chapter of the empire. According to Erdoğan, ‘World War I has not yet ended’, so the task of saving the Ottoman Empire from Western imperialists and their domestic collaborators, like the Arabs, is still there (Citation2017). The war is quite multi-faceted. For instance, Erdoğan compared Turkey’s economic crisis to the capitulations and debt spiral that led to the collapse of the empire a century ago: ‘We are now waging a struggle of historic importance against those who seek to yet again condemn Turkey to modern-day capitulations through the shackles of interest rates, exchange rates and inflation’ (Citation2020). The AKP also ‘discovered’ the battle of Kut al Amara (1915–1916), an Ottoman victory against the British forces during World War I, and invented the tradition of celebrating its anniversaries since its centennial in 2016 (Milliyet Citation2016).

In the securitised context of post-coup Turkey, the AKP heavily repressed equally valid alternative discourses and left little room for the fractured opposition to survive. However, the opposition’s solidarity and victory in the 2019 Istanbul mayoral elections demonstrated the limits of the AKP’s coercive and consensual tactics to sustain its rule. In particular, the new mayor Ekrem İmamoğlu, who bought the iconic painting of Ottoman Sultan Mehmed II and hosted the descendants of the royal Ottoman family in 2020, challenged the AKP’s monopoly over the Ottoman myth (Karar Citation2020).

Conclusion: AKP populism from unity to uniformity

Unlike Laclau’s emphasis on the unifying equivalential chains, this article argues that dislocation plays a central role in retaining the populist moment. However, this requires a different take on dislocation. Instead of using the concept to refer to a crisis or structural failure as the root cause (or beginning) of populism, one may approach dislocation as an intrinsic element of populism, building on the latter’s chameleonic quality. In the case of Turkey, the Ottoman as a surface of inscription reveals such successive dislocations from conservative to Islamist to nationalist populisms. Rather than analysing the AKP era as a whole or in two broad episodes (democratic and authoritarian), one should instead consider these intra-discursive dislocations as an inherent and constant element of Turkish populism. Yet the same signifiers (the nodal points, the empty signifiers, the political leader, the myths) function like glue that cements over fissures, alterations, shifts and ruptures, and enables continuity in the populist moment.

According to Laclau, the ‘people’ becomes ‘intensionally poorer’ the more it extends and encompasses more heterogeneous social demands, so it becomes a ‘tendentially empty signifier’ (Laclau Citation2005a, 96). Turkish populism demonstrates a reverse tide, in which the meaning of the ‘people’ slides from a unity-driven, broad discourse to a uniform construct. Despite including the demands of the ultranationalists, ‘the people’ in AKP populism today signifies a more restricted equivalential chain. Former foreign ministers Babacan and Davutoğlu, who represented the conservative democratic and Islamist wings of the AKP, cut off their relationship with the party and formed their own splinter parties, abandoning the AKP to nationalist discourse. With the weakened flexibility in the party’s political discourse, Erdoğan instead incorporated external alternatives such as the centre-right Tansu Çiller and Islamist Fatih Erbakan to his electoral bloc (Çevik Citation2020b). Nevertheless, Turkish nationalism is still rewarding for Erdoğan, since divergence around the Kurdish Question still impedes the formation of an alternative equivalential chain by the opposition. Overall, the AKP’s constant shape-shifting – from a vanguard of the EU membership process to anti-Western nationalism – should not necessarily be thought of in its ideological pursuits, but its populist calculations, depending on the changing circumstances. This tide of continual change in foreign policy is not an anomaly, but an intrinsic element of populism.

Acknowledgements

Earlier versions of the article were presented at the 2018 DVPW Conference, Frankfurt (25–28 September 2019), the Colloquium of Turkish Studies, University of Duisburg Essen (22 January 2019), and the InIIS Colloquium, University of Bremen (2 June 2021). I thank all the participants for their feedback. I am also immensely grateful to André Bank, Burcu Uçaray Mangıtlı, Stefanie Wodrig, and the anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments on several versions of the manuscript – although any errors are my own.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Hakkı Taş

Hakkı Taş is a research fellow at GIGA, Hamburg. His research interests include populism, Islamic movements, and identity politics, with a special focus on Turkey and Egypt. His articles have appeared in journals including Comparative Studies in Society and History, PS: Political Science and Politics, British Journal of Politics and International Relations and Third World Quarterly. His research has been funded by several institutions such as the Swedish Institute, the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation and the Gerda Henkel Foundation.

Notes

1 Comparing to domestic politics, Daniel Drezner relates this difference, first, to the thin interest-group environment in this field and, second, to the difficulty of achieving monopoly control over foreign affairs.

2 For a recent review, see Destradi, David, and Plagemann (Citation2021).

3 Anthony Smith, for instance, argued that nationalism can display a chameleonic feature, able ‘to transmute itself according to the perceptions and needs of different communities’ (1995, 13). Yet, his ethno-symbolic approach, in between perennialism and modernism, still adheres much substantive content to the category of the nation. Even in modernist approaches, nation-building draws on objective differences such as language, ethnicity, or territory, which later acquire subjective and symbolic meaning in the hands of the political elite.

4 Studies in the ideational approach accept AKP rule as populist only after the advent of its second term in 2007. This article, in contrast, considers the AKP populist from its onset, while recognising the varying degrees of its populism in different periods, as the ideational approach suggests. The divergence mainly stems from different conceptions of populism. The ideational approach sees anti-pluralism as part of populism, but the discourse-theoretic approach relates it to the attaching ideologies (Katsambekis Citation2022).

Bibliography

- AK Parti. 2019. “Tüzük.” https://www.akparti.org.tr/media/279929/cep-boy.pdf

- Akdoğan, Yalçın. 2003. Muhafazakar Demokrasi. Ankara: AK Parti.

- Al Jazeera Turk. 2014. “Erdoğan: Dünya Beşten Büyüktür.” 24 September. http://www.aljazeera.com.tr/haber/erdogan-dunya-5ten-buyuktur.

- Albayrak, Hakan. 2007. “Osmanlı gidince işler bozuldu.” Yeni Şafak, September 23.

- Alpan, Başak. 2016. “From AKP’s ‘Conservative Democracy’ to ‘Advanced Democracy’: Shifts and Challenges in the Debate on ‘Europe’.” South European Society and Politics 21 (1): 15–28. doi:10.1080/13608746.2016.1155283.

- Altunişik, Meliha B., and Lenore G. Martin. 2011. “Making Sense of Turkish Foreign Policy in the Middle East under AKP.” Turkish Studies 12 (4): 569–587. doi:10.1080/14683849.2011.622513.

- ANKA. 2008. “Başbakan Erdoğan'dan İstanbul'un Fethi Mesajı.” Haberler, 29 May. https://www.haberler.com/guncel/basbakan-erdogan-dan-istanbul-un-fethi-mesaji-haberi/

- Aslanidis, Paris. 2016. “Is Populism an Ideology? A Refutation and a New Perspective.” Political Studies 64 (1_suppl): 88–104. doi:10.1111/1467-9248.12224.

- Aydın, Mustafa. 2020. “Grand Strategizing in and for Turkish Foreign Policy: Lessons Learned from History, Geography and Practice.” Perceptions 25 (2): 203–226.

- Aydın-Düzgit, Senem, and Alper Kaliber. 2016. “Encounters with Europe in an Era of Domestic and International Turmoil: Is Turkey a De-Europeanising Candidate Country?” South European Society and Politics 21 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1080/13608746.2016.1155282.

- Aydın-Düzgit, Senem, Bahar Rumelili, and Alp Eren Topal. 2022. “Challenging Anti-Western Historical Myths in Populist Discourse: Re-Visiting Ottoman Empire–Europe Interaction during the 19th Century.” European Journal of International Relations, 1–25. doi:10.1177/13540661221095945.

- Balfour, R., J. A. Emmanouilidis, H. Grabbe, T. Lochocki, C. Mudde, J. Schmidt, and C. Fieschi. 2016. Europe’s Troublemakers the Populist Challenge to Foreign Policy. Brussels: European Policy Center.

- Balta, Evren. 2018. “The AKP’s Foreign Policy as Populist Governance.” Middle East Report 288. https://merip.org/2018/12/the-akps-foreign-policy-as-populist-governance/

- Bekdil, Burak. 2015. “We Trust You, You Know What You Are Doing.” Hürriyet Daily News, 15 July.

- Bonikowski, Bart, Daphne Halikiopoulou, Eric Kaufmann, and Matthijs Rooduijn. 2019. “Populism and Nationalism in a Comparative Perspective: A Scholarly Exchange: Populism and Nationalism in a Comparative Perspective.” Nations and Nationalism 25 (1): 58–81. doi:10.1111/nana.12480.

- Bora, Tanıl. 2007 [1998]. Türk Sağının Üç Hali. 10th ed. Istanbul: Iletişim.

- Boym, Svetlana. 2001. The Future of Nostalgia. New York: Basic Books.

- Bucak, S. 2014. “Turkey’s Erdogan Seen Softening Style Not Substance as President.” Reuters, 24 August. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-turkey-erdogan-rhetoric/turkeys-erdogan-seen-softening-style-not-substance-as-president-idUSKBN0GO0EI20140824

- Çevik, Salim. 2020a. “Turkey’s Military Operations in Syria and Iraq.” SWP Comment 37: 1–8.

- Çevik, Salim. 2020b. “New Political Parties and the Reconfiguration of Turkey’s Political Landscape.” SWP Comment 22: 1–4.

- Çevik, Senem B. 2019. “Turkish Historical Television Series: Public Broadcasting of Neo-Ottoman Illusions.” Southeast European and Black Sea Studies 19 (2): 227–242. doi:10.1080/14683857.2019.1622288.

- Christofis, Nicos, ed. 2022. The Kurds in Erdogan’s ‘New’ Turkey – Domestic and International Implications. London: Routledge.

- Chrysseogelos, Angelos. 2021. Is there a populist foreign policy?. London: Chatham House.

- Çınar, Alev. 2005. Modernity, Islam, and Secularism in Turkey: Bodies, Places, and Time. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Çınar, Alev, and Hakkı Taş. 2017. “Politics of Nationhood and the Displacement of Founding Moment: Contending Histories of the Turkish Nation.” Comparative Studies in Society and History 59 (3): 657–689. doi:10.1017/S0010417517000202.

- Çınar, Menderes. 2018. “Turkey’s ‘Western’ or ‘Muslim’ Identity and the AKP’s Civilizational Discourse.” Turkish Studies 19 (2): 176–197. doi:10.1080/14683849.2017.1411199.

- Daily Sabah. 2014. “Turkey Won’t Let the Middle East Be Called a ‘Swamp,’ Says Davutoğlu.” 20 July.

- Dalacoura, Katerina. 2021. “Turkish Foreign Policy in the Middle East: Power Projection and Post-Ideological Politics.” International Affairs 97 (4): 1125–1142. doi:10.1093/ia/iiab082.

- Davutoğlu, Ahmet. 1994. Alternative Paradigms: The Impact of Islamic and Western Weltanschauungs on Political Theory. Lanham, MD: University Press of America.

- Davutoğlu, Ahmet. 2001. Stratejik Derinlik. Istanbul: Küre Yayınları.

- Davutoğlu, Ahmet. 2012. “Principles of Foreign Policy and Regional Political Structuring.” Sam Vision Papers, 3 April. http://sam.gov.tr/principles-of-turkish-foreign-policy-and-regional-political-structuring/

- De Cleen, Benjamin, and Yannis Stavrakakis. 2017. “Distinctions and Articulations: A Discourse Theoretical Framework for the Study of Populism and Nationalism.” Javnost – The Public 24 (4): 301–319. doi:10.1080/13183222.2017.1330083.

- Destradi, Sandra, Cadier David, and Johannes Plagemann. 2021. “Populism and Foreign Policy: A Research Agenda (Introduction).” Comparative European Politics 19 (6): 663–682. doi:10.1057/s41295-021-00255-4.

- Destradi, Sandra, Plagemann Johannes, and Hakkı Taş. 2022. “Populism and the Politicisation of Foreign Policy.” The British Journal of Politics and International Relations 24 (3): 475–492. doi:10.1177/13691481221075944.

- Di Lampedusa, Giuseppe. 1960. The Leopard. London: Collins and Harvill Press.

- Erdoğan, Recep Tayyip. 2004. “Conservative Democracy and the Globalization of Freedom – Speech at the American Enterprise Institute.” In The Emergence of a New Turkey, Democracy and AK Party, edited by Hakan Yavuz, 333–340. Salt Lake City, UT: The University of Utah Press.

- Erdoğan, Recep Tayyip. 2013. “Ben Mardin’de dedim.” Twitter, 23 February. https://twitter.com/rterdogan/status/305296130470731776?lang=en

- Erdoğan, Recep Tayyip. 2017. “Kapanmamış Parantezin Kilidi: Misak-ı Milli.” Yeni Türkiye 93: 9–10.

- Erdoğan, Recep Tayyip. 2019. “Bugün Türkiye’de iki ittifak karşı karşıyadır.” Twitter, 26 February. https://twitter.com/RTErdogan/status/1100651748602056705

- Erdoğan, Recep Tayyip. 2020. “Turkey Continuing Now […].” TCCB, 10 November. https://www.tccb.gov.tr/en/news/542/122739/-turkey-continuing-now-in-a-stronger-manner-the-war-of-independence-it-launched-a-century-ago-is-the-reason-why-it-faces-such-a-nefarious-encirclement-

- Hacısalihoğlu, Devrim. 2017. “Ertuğrul Günay: Ak Parti büyük ölçüde tasiye edildi.” Euronews, 7 August.

- Haesebrouck, Tim, and Jeroen Joly. 2021. “Foreign Policy Change: From Policy Adjustments to Fundamental Reorientations.” Political Studies Review 19 (3): 482–491. doi:10.1177/1478929920918783.

- Hansen, Lene. 2006. Security as Practice – Discourse Analysis and the Bosnian War. London: Routledge.

- Hatipoglu, Emre, and Glenn Palmer. 2016. “Contextualizing Change in Turkish Foreign Policy: The Promise of the ‘Two-Good’ Theory.” Cambridge Review of International Affairs 29 (1): 231–250. doi:10.1080/09557571.2014.888538.

- Hauser, Michael. 2018. “Metapopulism in-between Democracy and Populism: Tranformations of Laclau’s Concept of Populism with Trump and Putin.” Distinktion: Journal of Social Theory 19 (1): 68–87. doi:10.1080/1600910X.2018.1455599.

- Herkman, Juha. 2017. “Articulations of Populism: The Nordic Case.” Cultural Studies 31 (4): 470–488. doi:10.1080/09502386.2016.1232421.

- Hoffmann, Clemens, and Can Cemgil. 2016. “The (Un)Making of the Pax Turca in the Middle East: Understanding the Social-Historical Roots of Foreign Policy.” Cambridge Review of International Affairs 29 (4): 1279–1302. doi:10.1080/09557571.2015.1119015.

- Hürriyet. 2013. “Yeni Türkiye’yi inşa ediyoruz.” 17 November.

- Hürriyet. 2003. “Türkiyelilik bilincini geliştirmeliyiz.” 2 September.

- Karar. 2020. “Fatih’in tablosu torunlarıyla buluştu.” 5 October.

- Katsambekis, Giorgos. 2022. “Constructing “the People” of Populism: A Critique of the Ideational Approach from Adiscursive Perspective.” Journal of Political Ideologies 27 (1): 53–74. doi:10.1080/13569317.2020.1844372.

- Kösebalaban, Hasan. 2011. Turkish Foreign Policy: Islam, Nationalism, and Globalization. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Kubicek, Paul. 2022. “Structural Dynamics, Pragmatism, and Shared Grievances: Explaining Russian-Turkish Relations.” Turkish Studies, 1–18. doi:10.1080/14683849.2022.2060637.

- Küçük, Cem. 2017. “Can suyumuz İslamcılıktır.” Twitter, 24 April. https://twitter.com/cemkucuk55/status/856438177002860544

- Laclau, Ernesto. 1990. New Reflections on the Revolution of Our Time. London: Verso.

- Laclau, Ernesto. 2005a. On Populist Reason. London: Verso.

- Laclau, Ernesto. 2005b. “Populism. What’s in a Name?” In Populism and the Mirror of Democracy, edited by Francisco Panizza, 32–49. London: Verso.

- Liang, Christina Schori, ed. 2007. Europe for Europeans – The Foreign and Security Policy of the Populist Radical Right. London: Routledge.

- Mikucka-Wójtowicz, Dominika. 2019. “The Chameleon Nature of Populist Parties. How Recurring Populism Is Luring ‘the People’ of Serbia and Croatia.” Europe-Asia Studies 71 (3): 450–479. doi:10.1080/09668136.2019.1590534.

- Milliyet. 2014. “Başbakan Erdoğan: ‘Cemaat yok onlar örgüt’.” 26 March.

- Milliyet. 2016. “Unutulan zafer Kut’ül Amare 100 yaşında.” 29 April.

- Moffitt, Benjamin. 2015. “How to Perform Crisis: A Model for Understanding the Key Role of Crisis in Contemporary Populism.” Government and Opposition 50 (2): 189–217. doi:10.1017/gov.2014.13.

- Mudde, Cass, and Cristobal Rovira Kaltwasser. 2017. Populism – A Very Short Introduction. New York: OUP.

- Muis, Jasper. 2015. “Populists as Chameleons? An Adaptive Learning Approach to the Rise of Populist Politicians.” European Quarterly of Political Attitudes and Mentalities 4 (2): 56–74.

- Nabers, Dirk. 2019. “Discursive Dislocation: Toward a Poststructuralist Theory of Crisis in Global Politics.” New Political Science 41 (2): 263–278. doi:10.1080/07393148.2019.1596684.

- Öktem, Kerem, Ayşe Kadıoğlu, and Mehmet Karlı, eds. 2009. Another Empire? A Decade of Turkey’s Foreign Policy under the Justice and Development Party. Istanbul: Bilgi UP.

- Onar, Nora Fisher. 2016. “The Populism/Realism Gap: Managing Uncertainty in Turkey’s Politics and Foreign Policy.” Turkey Project Policy Paper 8. Washington, DC: Brookings.

- Ongur, Hakan Ovunc. 2018. “Plus Ça Change … Re-Articulating Authoritarianism in the New Turkey.” Critical Sociology 44 (1): 45–59. doi:10.1177/0896920516630799.

- Öniş, Ziya. 2007. “Conservative Globalists versus Defensive Nationalists: Political Parties and Paradoxes of Europeanization in Turkey.” Journal of Southern Europe and the Balkans 9 (3): 247–261. doi:10.1080/14613190701689902.

- Özerim, Mehmet Gökay. 2018. “Stretching, Opening or Sealing the Borders: Turkish Foreign Policy Conceptions and Their Impact on Migration, Asylum and Visa Policies.” Journal of Balkan and near Eastern Studies 20 (2): 165–182. doi:10.1080/19448953.2018.1379751.

- Ozkan, Behlül. 2014. “Turkey, Davutoglu and the Idea of Pan-Islamism.” Survival 56 (4): 119–140. doi:10.1080/00396338.2014.941570.

- Özkök, Ertuğrul. 2004. “Kardeşiniz bir zenci Türk’tür.” Hürriyet, 15 May.

- Özpek, Burak Bilgehan, and Nebahat Tanriverdi Yaşar. 2018. “Populism and Foreign Policy in Turkey under the AKP Rule.” Turkish Studies 19 (2): 198–216. doi:10.1080/14683849.2017.1400912.

- Rodrik, Dani. 2018. “Populism and the Economics of Globalization.” Journal of International Business Policy 1 (1-2): 12–33. doi:10.1057/s42214-018-0001-4.

- Sevin, Efe. 2017. Public Diplomacy and the Implementation of Foreign Policy in the US, Sweden and Turkey. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Smith, Anthony. 1995. Nations and Nationalism in a Global Era. Cambridge, MA: Polity Press.

- Stavrakakis, Yannis. 2003. “Laclau with Lacan: Comments on the Relation between Discourse Theory and Lacanian Psychoanalysis.” In Jacques Lacan: Critical Evaluations in Cultural Theory (Volume III – Society, Politics, Ideology), edited by Slavoj Zizek, 314–337. London: Routledge.

- Stavrakakis, Yannis, Giorgos Katsambekis, Alexandros Kioupkiolis, Nikos Nikisianis, and Thomas Siomos. 2018. “Populism, Anti-Populism and Crisis.” Contemporary Political Theory 17 (1): 4–27. doi:10.1057/s41296-017-0142-y.

- T24. 2013. “Babuşçu: Gelecek 10 yıl, liberaller gibi eski paydaşlarımızın arzuladığı gibi olmayacak.” 1 April. http://t24.com.tr/haber/babuscu-onumuzdeki-10-yil-liberaller-gibi-eski-paydaslarimizin-kabullenecegi-gibi-olmayacak,226892

- Taggart, Paul. 2000. Populism. Buckingham: Open University Press.

- Taş, Hakkı. 2015. “Turkey – from Tutelary to Delegative Democracy.” Third World Quarterly 36 (4): 776–791. doi:10.1080/01436597.2015.1024450.

- Taş, Hakkı. 2018. “A History of Turkey’s AKP-Gülen Conflict.” Mediterranean Politics 23 (3): 395–402. doi:10.1080/13629395.2017.1328766.

- Tuğal, Cihan. 2021. “Turkey at the Crossroads?” New Left Review 127 (1): 25–54.

- Verbeek, Bertjan, and Andrej Zaslove. 2018. “Populism and Foreign Policy.” In The Oxford Handbook of Populism, edited by C. R. Kaltwasser, et al., 384–405. Oxford: OUP.

- von Schwerin, Ulrich. 2017. “Erdogan and Turkish Foreign Policy: Neo-Ottoman Rumblings.” Qantara, 18 January. https://en.qantara.de/content/erdogan-and-turkish-foreign-policy-neo-ottoman-rumblings

- Weyland, Kurt. 2001. “Clarifying a Contested Concept: Populism in the Study of Latin American Politics.” Comparative Politics 34 (1): 1–22. doi:10.2307/422412.

- Wodrig, Stefanie. 2018. “New Subjects in the Politics of Energy Transition? Reactivating the Northern German Oil and Gas Infrastructure.” Environmental Politics 27 (1): 69–88. doi:10.1080/09644016.2017.1384469.

- Yalvaç, Faruk, and Jonathan Joseph. 2019. “Understanding Populist Politics in Turkey: A Hegemonic Depth Approach.” Review of International Studies 45 (5): 786–804. doi:10.1017/S0260210519000238.

- Yeni Akit. 2016. “Kim bu üst akıl?.” 7 August.