Abstract

Pakistan occupies an elevated role in the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and hosts its so-called flagship project, the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). Existing literature has often interpreted this project from a geopolitical perspective, as a vehicle through which a rising China projects influence on a peripheral country and advances its own centrality in international affairs. While such motivations certainly played a major role in getting the project off the ground, they are not the sole determinant of its design, or the heated controversies it triggered within Pakistan. This paper seeks to capture both dimensions by analysing the development of CPEC, and the handling of the conflicts it sparked, through a lens of overlapping centre–periphery relations: one between China and Pakistan at the international level, and one between Islamabad and peripheral regions and groups within the country. I argue that this model best captures the pivotal position and resulting agency of national governments in shaping local BRI implementations. It also shows how the BRI is not a straight case of Chinese influence radiating outwards; rather, contestation by local actors in turn forces adaptations in Chinese foreign and security policy.

Introduction

China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is an issue that has seen no shortage of interest, particularly its heavily covered potential to transform geopolitics by tying smaller states into a Chinese orbit (Blanchard and Flint Citation2017; Ferdinand Citation2016; Rolland Citation2017). This perspective, which has dominated the early international literature on the BRI and its subsequent perception, focuses mainly on Chinese agency and strategic intent behind the project – specifically, the vision to rebuild a China-centric world order by infrastructural means, by economically integrating smaller states with its vast market, and perhaps ultimately pulling them into its political orbit (Callahan Citation2016; Rolland Citation2017, 131). More recently, attention has shifted towards specific implementations and their impact on the ground, often in the form of national-level case studies. Among these, Pakistan stands out as one of the first countries to sign up to the BRI, and the location of its ‘flagship’ project, the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). Pakistan has attracted the largest volume of investments under the BRI, with more than 30 billion USD already spent as of the time of writing, and expected total costs of over 60 billion (Scissors Citation2019; Small Citation2020). Its early phases have already seen major upgrades to Pakistan’s connectivity and electricity generation capacity (M. Ali Citation2020). Announced at a time of economic crisis, CPEC was hailed as a ‘game changer’ by the then-government of Pakistan, an opportunity to move beyond aid dependency and embark on a new, dynamic phase of industrial development (Markey Citation2020, 48; Wolf Citation2020, 79). Through its economic benefits, CPEC was also expected to serve as a nation-building project (Ahmed Citation2019), bringing greater unity and stability to a country riven with violent tensions between its diverse ethnic and religious constituencies.

However, the downside of CPEC quickly became visible in the form of political controversies over the distribution of its projects and its transparency, accountability and decision-making authority (Abb, Swaine, and Jones Citation2021; Hameed Citation2018); concerns about the future influence of China within the country (Hillman Citation2020, 147; Younus Citation2021); and violent resistance by local insurgent groups, resulting in multiple attacks on Chinese project sites and construction crews (M. Ali Citation2020; Small Citation2020). Economically, the viability of CPEC as a corridor is questionable, as there is little complementarity between Pakistan and China’s Xinjiang province (McCartney Citation2021, 86), overland trade is limited by the extremely challenging local geography (Garlick Citation2022, 38), and Chinese investors struggle with Pakistan’s alien business environment, bureaucracy and governance shortcomings. Politically, CPEC has contributed to centre–periphery tensions within the country and an erosion of trust in central governing authorities among more peripheral communities (Boni and Adeney Citation2020). The attempt to knit Pakistan’s national fabric closer together through the use of infrastructure also produced new tears, which then had to be mended with an ad hoc political strategy, and required direct Chinese involvement beyond China’s usual stance of ‘noninterference’.

This paper seeks to explain the evolution and impact of CPEC through a lens of centre–periphery relations, ie asymmetric relationships in which a ‘centre’ holds a power advantage over a ‘periphery’ and is able to exercise political, economic or ideational influence over it (Galtung Citation1971). Such relationships can occur and overlap on two levels: one internationally, and one within the peripheral country itself. In both relations, the respective ‘centres’ sought to reorder political spaces by infrastructural means. However, these centralising visions could not be simply imposed on a receptive (or captive) periphery, but required difficult negotiations with local interests.

As will be shown, this led to significant changes not just in the original designs, but also within the ‘centres’ themselves: to keep CPEC afloat, China had to move beyond its traditional diplomatic comfort zone of ‘noninterference’ in the domestic politics of other nations, and security threats encountered in Pakistan are now driving adaptation and even inner-Chinese discourses on overseas intervention. Meanwhile, the influx of resources into Pakistan also caused an intense jostling for their control within its political system, affecting both its federal designs and civil–military relations (Boni and Adeney Citation2020). The paper discusses two distinct Chinese strategies adopted in response, one narrowly focused on securing project sites, and the other on fostering a pro-CPEC political consensus among Pakistani elites. Based on this interpretation, I argue that CPEC, and the BRI in general, is not just a one-way street projecting Chinese influence abroad, but also exerts an adaptive pressure back on its origin.

The paper is based on interviews with experts, politicians and activists in Pakistan, a survey of Chinese and Pakistani analyses and media reports on CPEC’s challenges and how to overcome them, the known details of specific projects, and a review of previous publications on CPEC. It is structured as follows: the next section briefly introduces the model of overlapping centre–periphery relations and describes the main actors in the case of CPEC. Subsequently, I recount its development, and the tensions arising from it, through the interests and agency of central and peripheral actors in both relationships. The second half of the paper analyses the responses of both centres to challenges against their mutual project, specifically the strategies used to securitise it and rebuild a political consensus around it. The paper concludes with implications for CPEC in Pakistan and broader Chinese international agency in the age of the BRI.

Overlapping centre–periphery relationships: China, Islamabad and Pakistan’s internal periphery

This paper loosely adopts a model proposed by Johan Galtung in his structural theory of imperialism (Galtung Citation1971), which models such systems through relationships at two levels: between an upper-case ‘Centre’ and a ‘Periphery’ at the international level – the imperial metropolis and the colony – but also lower-case ‘centres’ and ‘peripheries’ within each of them, defined as in- and out-of-power groups. Power differences result in the submission and likely exploitation of both the Periphery and the two domestic peripheries. This can take the form of nineteenth-century-style, resource-exploitative imperialism, up to more modern forms of empire in which Centres may be more interested in the acknowledgement of their leadership or the exertion of cultural dominance, while material resources actually flow the other way (eg in the form of development aid). Notably, this model predicts that a stable and even ‘harmonious’ relationship can be established between the centres of the two nations, based on an alignment of interests and mutual benefit from international exchanges, but at the price of increased tensions and conflicts within the Periphery as its own, doubly marginalised periphery is driven to resistance. This model is useful for two reasons: first, it offers a chance to integrate both geopolitical and domestic politics perspectives on the BRI; and second, it highlights the agency of the Periphery’s centre, whose collaboration is necessary in a project like the BRI, and whose interests its local adaptations need to reflect.

Centre–periphery relations are an increasingly appropriate lens to study relations between a rising China and smaller developing nations, in which the former will almost inevitably be – and perceive itself as – the Centre, by virtue of its sheer size and increasing economic and political gravity. The notion of centrality is fundamental to China’s historical self-definition as the core of a ‘sinocentric’ regional order (Kang Citation2010), and informs its contemporary desire to reclaim what Chinese elites believe to be its legitimate position in the world. In the Xi Jinping era, slogans from the desired ‘rejuvenation of the Chinese nation’ to an ambition of ‘moving back to the center stage’ of world politics (Zhang Citation2019) have explicitly voiced the underlying ambition of re-establishing Chinese centrality (Reeves Citation2018). At the policy level, Beijing has formalised these designs under the rubric of its new ‘peripheral diplomacy’ since 2014, shifting the focus away from its traditional emphasis on great power relations and towards its immediate neighbourhood (Callahan Citation2016). To Chinese strategists, this space is ambiguously conceptualised, on the one hand, as offering great opportunities for China to integrate it economically, build its own institutions, and exercise political leadership within it; on the other, it is also marked by instability and requires a careful management of local relationships, as smaller countries feeling threatened by a rising China might otherwise seek to contain it in partnership with the US (Swaine Citation2014).

The BRI is key to the fulfilment of this political vision: by building a series of corridors through China’s periphery and connecting them to the vast Chinese market, they would not only serve the further development of its own interior, but eventually grow into its natural extension. The specific case of CPEC has been analysed through the same lens, focusing on Chinese strategic visions of transforming and securing its near abroad by means of infrastructure (Hillman Citation2020; Markey Citation2020). As will be detailed further below, these motivations weighed heavily on the Chinese decision to commit to a gargantuan project like CPEC. However, despite China’s considerable power and the amount of resources mobilised for the BRI, its actual implementation on the ground is not simply a result of Beijing imposing its strategic designs in a top-down fashion, but also a result of negotiations with local power holders pursuing their own aims (Boni and Adeney Citation2021). Accordingly, there is a second ‘centre’ and a lower-case periphery that need to be taken into account when analysing the impact of such projects.

Within Pakistan, centre–periphery tensions are highly pronounced, springing from its origin as a multiethnic, postcolonial state assembled from the Muslim-majority parts of British India. Aside from a shared religion, Pakistani nationhood has been defined by its rivalry with India, whose larger size and superiority in military capabilities have driven both efforts at self-strengthening and external cooperation with China (Markey Citation2020, 61; Small Citation2020). Pakistan’s ‘centre’ is less a geo- than a demographic one, formed by ethnic Punjabis who constitute a plurality of 45% of its citizens, the dominant voting constituency, and historically an elite that has dominated national-level politics, with an especially strong hold on the nation’s security apparatus and civil service (Waseem Citation2011). Equally important here, this centre constitutes itself through its privileged position in formulating visions for national development and nation-building, mainly in the form of five-year-plans and later development frameworks.

Minority ethnicities occupying Pakistan’s periphery (Gilgit-Baltistan, Khyber-Pakthunhwa and Balochistan, but also comparatively highly developed Sindh) have sought to counter centralising efforts with designs emphasising federalism, bicameralism, devolution and regional self-governance, scoring a major victory with a 2010 constitutional amendment (Adeney Citation2012). Infrastructure is a major locus for contestation between national and provincial administrations and constituencies, and has also repeatedly laid bare ethnic tensions: for example, the Tarbela dam on the Indus River, constructed in the 1970s, was pursued by national-level elites to advance the dual causes of technocratic developmentalism and political centralisation, but for the same reason faced stiff resistance from peripheral regions (Akhter Citation2015). The proposed Kalabagh dam has similarly divided constituencies in Punjab, who tend to back central authorities and their national development schemes, and downstream Sindh, which saw it as a threat to its water rights and provincial autonomy (Mustafa Citation2021, 36–40).

In this model, Islamabad is the point where the two relationships overlap, as the Periphery’s centre. Successive Pakistani governments have deftly used this pivotal position to pursue their own needs for external capital and infrastructure construction expertise, appealing to international funders with a strategic interest in the country, its stability or the advantages of its geography (Hillman Citation2020, 128). However, deficiencies in Pakistan’s internal governance have made these efforts highly contentious domestically, with distribution conflicts, concerns over corruption and a lack of transparency, and civil–military struggles over control of the project at the top of the list.

CPEC and its origins: interests, visions and priorities

CPEC builds on a long history of previous Chinese–Pakistani cooperation on strategic infrastructure, albeit on a much larger scale. This connection is immediately obvious from the two points anchoring CPEC, and which led to its designation as a ‘corridor’ running from the Pakistani–Chinese border to the port of Gwadar on the Indian Ocean. The former, a rugged mountain range, had been infrastructurally opened up through the construction of the Karakoram Highway in the 1960s and 1970s, carried out by Chinese and Pakistani military engineers. This work was initially motivated by strategic reasons – supporting the budding alliance between the two countries, carrying Chinese military aid to Pakistan, and enabling better control over the restive frontier territory (Haider Citation2005; Hillman Citation2020, 135). The development of Gwadar, which began in 2002, can similarly be traced to the initiative of Pakistan’s then-president Pervez Musharraf to lessen his country’s reliance on the port of Karachi, considered too close to the Indian border for comfort (Markey Citation2020, viii). In both cases, China transferred capital and infrastructural know-how to Pakistan in the hope of strengthening its quasi-ally.

A similar confluence of interests explains the origins of CPEC. At the time of the BRI’s announcement in 2013, Pakistan found itself mired in economic crisis. Over the preceding decade, the country had grown increasingly dependent on US development and military assistance in exchange for its participation in the ‘War on Terror’ (Hillman Citation2020, 139; Wolf Citation2020, 85). These were significantly curtailed amidst the drawing down of regional US counterterrorism campaigns, leaving Islamabad desperate to find a way out.Footnote1 In 2013, the newly elected Pakistan Muslim League (PML-N) government of Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif pitched a renewed design for infrastructural cooperation to Beijing, seeking to take advantage of its nascent vision for the BRI, and secured a quick commitment from premier Li Keqiang (Small Citation2020). The actual details of what would become CPEC took a lot longer to hash out (the process is arguably still ongoing), but key points had by 2017 been settled under a ‘long-term plan’ drawn up by the top-level economic planning agencies of both sides (MPDR/NDRC Citation2017).

According to this plan, CPEC’s implementation would span three phases, with the first focusing on the most immediate needs of electricity generation and connectivity. The former was covered by a dozen new power plants designed to end Pakistan’s plague of frequent black- and brownouts; the latter through providing an integrated road, rail and telecoms link along a North–South axis, running from the Chinese border to Gwadar. The port itself, intermittently managed by the Singapore Port Authority, would once again be run by China and expanded with further cargo facilities and a tourist zone. Phase two would seek to boost industrialisation in 12 new Special Economic Zones (SEZs) along the corridor, luring investors with new infrastructure, tax incentives and enhanced access to the Chinese market. A third phase would focus on the agricultural sector, encouraging Chinese companies to acquire lands in Pakistan and transfer knowledge on crop seeding, fertilisation and mechanised harvesting. The project’s total costs were initially estimated in the 40 billion USD range, making Pakistan the BRI’s number one investment destination by a wide margin; with about 35 billion USD already spent as of 2021, the projected total has now been revised to over 60 billion USD (Scissors Citation2019).

Establishing the Pakistani government’s interest in CPEC is straightforward. Most obviously, it promised to bring huge new investments to the country, solve the urgent electricity shortages in the country, and open up a viable pathway to industrialisation (Wolf Citation2020, 73–78). But it also had another dimension as a nation-building project, continuing previous attempts to integrate Pakistan’s national space through infrastructure. According to the PML-N government’s rhetoric of CPEC as a ‘game changer’, it would not only spur overall development but also reduce existing divisions within the country by letting all of its constituents share in the benefits of modernity and globalisation (Ahmed Citation2019; Hameed Citation2018). By portraying it as proof of the ‘all-weather friendship ‘between Beijing and Islamabad, proponents also encouraged the perception that CPEC was part of a strategic alliance bolstering Pakistan against its Indian archenemy – making criticism risky, as it could quickly be branded as unpatriotic’ (Afzal Citation2020). This politicisation initially helped to mobilise significant popular support for the project, but also raised expectations that would turn out to be very difficult to meet.

Why China agreed to a project of this scope, in a country with known financial and governance problems, ongoing insurgencies and a history of militant attacks on Chinese construction crews, requires a yet more complex explanation. Several factors have been stressed in the writings of Chinese academics and international scholars, many of which are connected to the transformative potential CPEC had for China’s strategic geography. For one, the port of Gwadar and the proposed pipeline to the Chinese border were expected to enhance China’s energy security by lessening its dependence on shipping through the easily blockaded Malacca Strait (Yao Citation2015). Chinese scholars were notably more sceptical than international scholars about the feasibility of such a pipeline but assumed it was a main feature of CPEC, especially during the negotiation phase (Garlick Citation2022, 18). Rising tensions with India made Pakistan an attractive ally and counterweight (Markey Citation2020, 47; Small Citation2020). The security problems posed by insurgents and terrorist groups operating in many of the corridor’s proposed transit zones were brought up by many Chinese analysts (Liu Citation2015; Yao Citation2015; Zhang Citation2016), but the fact that they were a transnational, mutual threat to both Pakistan and China also provided one of the rationales for CPEC: here, the vision was that it would economically stabilise Pakistan and enable greater state control over the frontier spaces in which such groups thrived, reducing their manoeuvring space and ultimately yielding benefits for China’s own security (Markey Citation2020; Zheng Citation2016). Security risks could be managed in the short term through joint counterterrorism efforts, on which Pakistan and China were already cooperating, and in the long term resolved through greater economic opportunities and a projected reduction in militancy (Liu Citation2015). From this perspective, CPEC appears to be an international extension of the Chinese approach to alleviating instability in its own Western periphery, which had followed identical priorities.

An additional factor that made Pakistan an attractive partner was its perceived reliable pro-Chinese orientation. Chinese analysts weighing political risks to the BRI heavily focused on two factors: first, so-called ‘geopolitical risks’, mainly the firm opposition of the US and its allies to the BRI (Zhou Citation2016), and in the specific context of South Asia, Indian resistance to Pakistani–Chinese cooperation and CPEC’s routing close to disputed Kashmir (Jiang Citation2015). Against this backdrop, the new PML-N government presented an opportunity as it seemed less beholden to US influence than its predecessor, and its principal figures were known enthusiasts of infrastructure megaprojects. The second big concern was political instability, mainly assessed in terms of government turnovers and policy changes that might lead to the abrogation or renegotiation of earlier BRI agreements (Ma Citation2015; Tan Citation2015). A key requirement in picking a site for the BRI’s ‘flagship project’ was thus a partner who was prepared to resist external pressure and stick with China for the long term. Despite Pakistan’s complex internal politics, its strategic dependence on China as an ally, and the commitment of all major political actors to this partnership, seemingly ensured a long-term buy-in that outweighed other local risks (Yao Citation2015). Beijing was determined to go fast and big in kicking off the BRI, and Pakistan offered an enticing mixture of local demand, strategic benefits and a conducive political environment to accommodate this approach.

In summary, CPEC’s genesis can be seen as the confluence of two separate but compatible visions of how to reorder centre–periphery relations by infrastructural means: on the one hand, Pakistan’s desire to increase cohesion in its fractious society through a national development plan; and on the other, the BRI’s grand ambition to ‘recentre’ China on the world stage by linking sympathetic countries even more closely to it. Inherent to this approach, however, was a lack of consideration for peripheral interests, whose resistance subsequently required substantial policy adaptation.

The securitisation of CPEC

As a project devised by central authorities and intended to strengthen their control over the country, CPEC was naturally rejected by separatists dedicated to their own vision of independent nationhood. This opposition is especially pronounced in Balochistan, home to the port of Gwadar and one of the longest proposed stretches of CPEC. Pakistan’s south-western province is a geographically vast and resource-rich but sparsely populated and underdeveloped area, which has relegated it to the fringes of Pakistani politics (Bansal Citation2008). It is also one of the hotbeds of Pakistan’s insurgency problem and has seen repeated armed uprisings, met with an extensive counterinsurgency campaign by Pakistan’s armed forces. One of the main grievances motivating insurgent groups, the perceived exploitation of Balochistan’s natural wealth at the hands of outsiders (Khan Citation2009), directly implicates China and its projects in the area. In this narrative, CPEC is the latest instalment in a long line of infrastructural projects designed and operated by colonial powers to funnel local resources towards the metropolis, without delivering any benefits to the Baloch people (Hameed Citation2018). Both Gwadar and Chinese mining operations in the region (which are scheduled to expand under CPEC) are seen as redolent of British-era installations in their extractive orientation and top-down planning.Footnote2 By design, Gwadar is a national-level project overseen by the central government, which appoints the chairman of its Port Authority (GPA) and a supermajority of the board (GPA Citation2002). Under the treaties signed with China, the latter is entitled to 91% of its revenue for 40 years, while the GPA receives only 9% (Khan Citation2017). Multiple sources in Balochistan stressed this lack of control and stakeholdership as the main reason motivating resistance against CPEC, citing repeated failures of Pakistan’s national political authorities to involve them in planning and implementation processes.

Much of the resistance towards CPEC has been peaceful, but it has become a repeat target for insurgent attacks, mainly from the Balochistan Liberation Army (BLA) and the Pakistani Tehreek-e-Taliban. Since the launch of CPEC in 2015, these groups have committed 10 attacks against Chinese projects in the country that resulted in 61 deaths and 35 injuries – the vast majority of which have been Pakistani, 52 and 31, respectively.Footnote3 Chinese personnel work in fenced-off enclaves and move about under military escort, which has reduced their exposure to threats. However, it has also resulted in a heavily securitised version of development that is only feasible under constant military protection and considered a burden by local communities. To defend CPEC sites, the Pakistani military set up a ‘Special Security Division’ of 15,000 troops and a special naval detachment in Gwadar, which has made it a major stakeholder in the project. High-profile sites like Gwadar are fenced and ringed by multiple layers of checkpoints, which has resulted in harassment and affected the freedom of movement of local people.Footnote4 This has also had effects on their livelihood, as security ordinances have limited the access of local fishermen to the sea.Footnote5 The reality of CPEC – essentially, a fusion of Chinese developmentalism and Pakistan’s own security state – has so far proven incapable of generating local buy-in.

China was initially content to leave CPEC’s security entirely to the Pakistani military, a partner in which it holds great strategic trust,Footnote6 and which is also in line with its diplomatic stance of non-interference in the domestic concerns of other countries. However, the constant threat to its citizens and capital is now having an impact on inner-Chinese debates on how the country should go about protecting its overseas interests, and how to deploy its ever-growing power. The July 2021 bombing of a convoy which killed nine Chinese engineers (widely attributed to the Tehreek-e-Taliban) triggered Chinese media criticism of Pakistani security measures and calls for direct Chinese involvement in local counterterrorism operations (Global Times Citation2021). A 2022 BLA attack in Karachi that killed three Chinese teachers from the local Confucius Institute led to a significant sharpening in China’s official diplomatic rhetoric, with premier Li Keqiang conveying ‘shock and outrage’ to his newly elected counterpart Shehbaz Sharif, as well as making clear demands for stronger security measures (FMPRC Citation2022). Frustration with the existing security regime is mounting both in Beijing and among the Chinese community in Pakistan. One Chinese expat academic interviewed for this paper spoke of a pervasive and growing distrust in Pakistani security measures, citing poor training, ineffective administration and corruption among local forces.

While there is a universal expectation that the Pakistani army will remain in charge of CPEC’s military security and direct Chinese military involvement is not on the cards,Footnote7 these problems are already spurring lower-profile changes in Chinese overseas activities. China has stepped up its intelligence-sharing on counterterrorism efforts and the export of surveillance and facial recognition technology to Pakistan (Layton Citation2020). According to local experts interviewed for this paper, Chinese representatives have also reached out to insurgent leaders in Balochistan and sought to pay them off in exchange for the safety of their projects.Footnote8 Although long reluctant to invest in project security, overseas-operating Chinese enterprises have stepped up training and emergency evacuation planning at the urging of their embassies (Ghiselli Citation2021, 103). China’s growing sector of private security contractors (PSCs) are already offering services in Pakistan, although Pakistan’s prohibition on foreigners carrying weapons is limiting them to training local personnel and acting as consultants. This has become a contentious point as China is now actively lobbying Pakistani authorities to relax restrictions on Chinese PSCs. In any case, the high costs of such services have so far limited them to large Chinese state-owned enterprises (SOEs), while smaller businesses or individuals have to hire local security or forgo it.Footnote9 These developments are ongoing, but they are evidence that the BRI is not just a tool through which China exerts a quasi-gravitational pull on its periphery, but is in fact being drawn into the latter itself, in ways it had not originally intended.

The breaking and remaking of a political consensus around CPEC

While the insurgent threat to CPEC has caught the most attention, a lower-intensity and non-violent, but arguably more significant, resistance has played out in Pakistan’s political arena. Here, CPEC sparked a heated debate over three key issues: the distribution of its projects, the location of decision-making authority, and the lack of transparency over the content of specific agreements.

Distribution conflicts can be traced to a familiar fault line in Pakistani politics, the perception that developmental efforts are the project of a technocratic elite drawn from the ranks of ethnic Punjabis, and designed for their benefit (Waseem Citation2011; Mustafa Citation2021). Support and opposition to large-scale infrastructure projects have often fallen along ethnic lines. Originally, CPEC was supposed to be different, with a planned corridor directly linking Gwadar to the Chinese border, which would have traversed and benefitted Pakistan’s less-developed Western periphery (Bengali Citation2015). As negotiations with Beijing dragged on in 2014–2015, however, it emerged that there was little Chinese interest in this route, due to the lack of existing infrastructure and the severe insurgent problem in these areas. Leaks that the central government was now exploring an ‘Eastern’ route through better-developed areas in Punjab and Sindh triggered fierce opposition from constituencies along the ‘Western’ route (Shah Citation2015). The routing controversy was seemingly resolved in May 2015, when an all-party conference established a compromise, replacing the single ‘corridor’ with three north–south ‘arteries’ and several lateral connections. However, finding Chinese financing for these roads proved challenging, and several years later, most of the promised roads in the West had still not been included in the CPEC portfolio, have yet to begin construction or even receive the necessary funding commitments (Aamir Citation2019). Far from being a ‘game changer’, CPEC thus reinforced existing feelings of betrayal among the concerned communities and led to a further loss of trust in central authorities.Footnote10

Similar problems have marred CPEC’s other priority, the amelioration of Pakistan’s chronic energy deficit and frequent blackouts. According to government statistics, nine new plants came online from 2015 to 2020, adding a total capacity of about 5000 MW mainly from coal power generation (CPEC Citation2021). In theory, this is enough to cover Pakistan’s previous nationwide deficit, caused by an inability of local energy providers to obtain foreign financing for new plants (Safdar Citation2021), but again it is unevenly distributed. With one exception, the finished plants are located entirely in Punjab and Sindh, and the power they generate is predominantly delivered to urban, well-developed eastern parts of Pakistan, while transmission grids in Pakistan’s western regions are too outdated, disconnected and sparse to adequately supply local households.Footnote11 Transmission losses of 10% and theft of 5% further reduce available power. Moreover, the new plants (except the Thar mining/plant complex) cannot make use of Pakistan’s domestic lignite coal and rely instead on imports, which need to be shipped through Karachi and moved by truck up North.Footnote12 The 2022 spike in resource prices and depreciation of the Pakistani rupee also made them too expensive to run at full capacity, resulting in widespread power cuts that predominantly affected rural households (Mangi Citation2022).

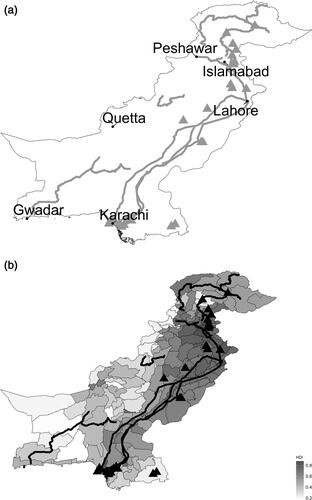

When mapping out projects that have been completed or begun construction using geolocation data (), both the connectivity gaps in the proposed ‘Western route’ and the heavy concentration of power plants in Eastern and Southern industrial centres are immediately apparent. This will also have consequences for the next phases of CPEC: while every province has been assigned at least one of the proposed SEZs, their progress in peripheral areas is hampered by the lack of connectivity and utility infrastructure. The most progress has occurred in Punjab’s Allama Iqbal Industrial City, which is located near the new M-3 motorway, part of CPEC’s ‘Eastern Route’. Kyber-Pakthunkwa’s Rashakai SEZ similarly benefits from its position along the modern M-1 motorway. Balochistan’s SEZ in Bostan near Quetta, however, is right in CPEC’s Western connectivity gap and can only be accessed via the older, two-lane N-25 and N-50 highways, whose expansion and modernisation remain in the planning stage. The viability of Gwadar’s ‘Free Trade Zone’ is similarly questionable due to its remote location and inconsistent supply of basic utilities like water and electricity. From this imbalance, it is easy to understand concerns that CPEC will cement existing developmental gaps, leaving peripheral areas even further behind (Hameed Citation2018).

Figure 1. CPEC’s eastern skew: (a) geographic location of connectivity (lines) and power plant (triangles) projects within Pakistan; and (b) overlaid on district-level human development index (HDI) data.

Source: Author’s compilation of project location data obtained from the Reconnecting Asia database (CSIS 2020), restricted to projects that are marked as ‘completed’ or ‘under construction’. HDI data obtained from Najam and Bari (Citation2017).

Given the importance of project selection, the question of who had the authority to do so and to negotiate specifics with the Chinese side emerged as the second point of contention. Here, the securitisation strategy also had a direct political impact as Pakistan’s military became increasingly involved in project selection and implementation.Footnote13 This reflected another familiar fault line in Pakistani politics – the struggle between civilian and military authorities (Waseem Citation2011) – and a reversal of the post-Musharraf trend of asserting civilian control over national infrastructure (Boni Citation2020, 94–95). Here, the government turnover in 2018 was a watershed moment, as the incoming administration of premier Imran Khan (a noted CPEC critic when in opposition) increasingly relied on the military as intermediaries in negotiations with Beijing,Footnote14 while also offering it a much greater role in the project’s domestic governance. In October 2019, it instituted a new ‘CPEC Authority’ by executive decree, headed by retired general Asim Bajwa, and following a model the army had proposed in 2016 (Boni and Adeney Citation2020). It is unclear whether Beijing had actively pushed for this reorganisation, but it certainly welcomed it after its initial experiences with the Khan government.Footnote15

A final major concern about CPEC – and one highlighted even by some of its supporters – is the lack of transparency over two aspects: the underlying funding agreements, which remain non-public; and the ultimate scope of the project, which is constantly evolving and branching into new areas of Pakistan’s economy. As with most of the BRI, CPEC’s projects are not financed through development aid, but using commercial loans, albeit at preferential rates. The exact interest rate and repayment scheme have not been publicised by the government, supposedly because the terms are so generous that this would complicate Chinese negotiations with other loan recipients.Footnote16 The master plan for CPEC has similarly remained a secret closely guarded by the central government until it was leaked to the press in 2017; notably, it had been shared in full with Punjabi authorities, while all other provinces received a version shortened to less than a fifth (Husain Citation2017). The level of secrecy has further contributed to an erosion of trust in the central authorities pursuing the project, and given rise to concerns about over-indebtedness even in a populace predisposed to welcoming Chinese involvement in their country (Small Citation2020).

Faced with these problems, rebuilding political support for CPEC was a major task that also involved China in an active role, a highly significant development given its long-standing commitment to non-interference in the domestic politics of other nations. In the planning stage, Chinese diplomats had already reached out to opposition parties, seeking to counter perceptions of CPEC as a PML-N pet project and to insulate it against future government turnovers (Small Citation2020). Chinese negotiators were somewhat willing to alter the subnational distribution of CPEC projects and, for example, agreed to an even number of proposed industrial parks for all provinces (Hussain and Rao Citation2020). In 2019, Beijing convened a format of its own, the Joint Consultation Mechanism (JCM), in which representatives of Pakistani parties can engage with high-level Chinese officials. On the Pakistani side, it includes nine parties (including all three major national parties and four Balochistan-based ones) and a selection of individual opinion leaders (Gitter, Bowie, and Callen Citation2019). On the Chinese side, it is organised by the International Department of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), which handles contacts with foreign political parties, and also involves official diplomatic staff in Pakistan. The first JCM, held in March 2019 in Beijing, issued a declaration that appears mainly designed to formally commit the Pakistani participants to supporting CPEC (JCM Citation2019). Its language clearly mirrors China’s preferred rhetoric around CPEC and the BRI as building blocks for a ‘community with a shared future for mankind’, while also urging participants to ‘create favorable conditions’ for CPEC and exercise ‘political guidance’ over their constituencies. From what little is known about the content of these discussions, they mostly involve the signalling of political loyalty to CPEC and the China–Pakistan friendship, not exchanges on contentious issues. Summarised remarks from the second JCM meeting strongly focused on rebutting criticism of the project (Express Tribune Citation2020). Recordings from this and similar formats held in 2020 also had a heavy emphasis on praising China’s Covid-19 response,Footnote17 an issue which had little to do with CPEC, but was an urgent priority for Chinese domestic and international propaganda efforts at the time (Gill Citation2020). In exchange, participants received access to Chinese representatives within Pakistan – where the embassy is the crucial gatekeeper – and China itself through party channels. The asymmetry of this bargain neatly summarises the relationship between the two sides, in which a would-be Centre obtains symbolic recognition of its desired status, and actors from the periphery receive privileged access in return.

At the level of policy communities, Chinese think tanks have been closely engaging sympathetic counterparts in Pakistan, following a domestic directive to ‘build a strong social foundation for the BRI’, ie to promote it with opinion leaders in member countries and counter local and Western criticism of the project (Abb Citation2016). In Islamabad, they found ready partners, predisposed to positive attitudes towards the strategic value of CPEC and partnering with China in general. In interviews conducted for this study, Islamabad-based policy elites were by far the most positive about CPEC and its effects, citing China’s attractiveness as a source of capital, its commitment to Pakistan as a partner and respect for its sovereignty, and the speed of implementation despite Pakistan’s cumbersome bureaucratic and political processes. Setbacks were usually ascribed to a lack of Chinese familiarity with local conditions, which has created a demand for consultant services by Pakistani experts.

A central function is played by the Pakistan–China Institute (PCI), a think tank founded in 2009 by Senator Mushahid Hussain, the chairman of the Senate’s Foreign Affairs Committee since 2018 and the Parliamentary Committee on CPEC since 2015. Upon CPEC’s launch in 2015, it established a joint research and consultation platform with the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS), China’s largest think tank, and has since acted as a conduit to hold regular meetings between policymakers and experts from both sides, disseminated a large number of pro-CPEC reports (PCI Citation2020), and helped Chinese companies broker local business deals and navigate Pakistan’s political landscape (Markey Citation2020, 56). The PCI advocates for CPEC in particular and robust ties with China in general, and sees its role as building a domestic consensus on both issues, which includes co-organising the all-party conferences under the JCM.Footnote18 Other ties exist with established institutes within Pakistan’s strategic studies community, such as the Institute of Strategic Studies Islamabad (ISSI) and the Islamabad Policy Research Institute (IPRI). In the past several years, they have staged an enormous number of conferences and webinars on CPEC and China–Pakistan ties – PCI alone held 14 in the last two years.Footnote19 These exchanges mainly involve policy elites in Islamabad who are already a highly supportive constituency for CPEC, while more critical voices from the periphery either found themselves outright excluded from such gatherings or left with little confidence that their input was taken seriously.Footnote20 And while they are also intended to inform the Chinese side about challenges in Pakistan, the heavy participation of elites with strong pro-CPEC opinions or personal stakes in the project precludes frank discussions.Footnote21 Still, the development of an intellectual infrastructure underpinning Centre–Periphery relations is rapidly following the physical one, and ties between policy communities are increasingly reminiscent of the networks underlying transatlantic relations.

Beyond political and policy elites, a China-led civil society outreach has aimed at groups that are sceptical or hostile towards CPEC. Before the pandemic, local politicians and journalists from Balochistan were regularly invited on tours of China, allowing it to showcase its own successful modernisation and portraying it as a friend to all of Pakistan. However, according to one participant, these attempts did not produce the desired effect because they followed a general image-building template rather than addressing issues of specific concern to Baloch communities.Footnote22 A similar problem has marred local corporate social responsibility (CSR) efforts provided by Chinese enterprises. Many local citizens in the immediate vicinity of projects see Chinese companies as aloof and either ignorant of or indifferent to their concerns (Jafri 2020). Where CSR efforts have been undertaken at all – eg through the construction of a school in Gwadar – they have been perceived as inadequate.Footnote23 More progress has been made in education and training, where Chinese-funded programmes have been specifically designed to address the concerns that peripheral communities would be locked out of desirable employment within CPEC due to a lack of marketable skills.Footnote24 Bilateral cooperation has improved vocational training in Pakistan and focused it on areas likely to be of specific relevance to CPEC.Footnote25 China has committed to funding a vocational training centre within each of the new SEZs and major projects like Gwadar or the Sahiwal coal plant, focusing on the skills required by local industries, and offering scholarships for advanced studies in China.Footnote26 Locally provided Mandarin classes have served to reduce the language gap, while over 20,000 Pakistani students have received scholarships to Chinese universities, meeting a rising interest in China-facing careers (Safdar Citation2021). In the long run, this may effect a shift in the orientation of Pakistani elites, who have traditionally pursued higher education at US or UK universities – one interviewee who obtained her PhD in Beijing considered it an alternative window on the world.Footnote27

Finally, both Chinese and Pakistani actors undertook (partially joint) media efforts to promote CPEC, control the narrative surrounding it, and push back on criticism. This became an especially urgent task in 2017–2018, as concerns over the lack of transparency surrounding CPEC, the leak of internal planning documents, and new prime minister Imran Khan’s apparent scepticism of the project threatened the shaky domestic consensus (Afzal Citation2020). On the Chinese side, former deputy ambassador to Pakistan Zhao Lijian took on a very active and unusual role, especially when it came to social media engagement. While Zhao is best known for pioneering the so-called ‘wolf warrior diplomacy’ through his aggressive rebuttals of CPEC criticism on Twitter, he also used the medium to provide detailed information in response to factual inquiries (Palmer Citation2021). Within Pakistan, proponents of CPEC sought to insulate the project against criticism by stressing its relevance for national security and casting its detractors as ‘enemies’ of the Pakistani state (Afzal Citation2020). Chinese and Pakistani actors are also increasingly coordinating their counter-messaging: when former US Deputy Secretary of State Alice Wells criticised CPEC as an example of ‘debt-trap diplomacy’ in November 2019 (and on a subsequent visit to Islamabad in January 2020), her points were immediately rebutted by officials from both countries (Aamir Citation2020). The PCI played a major role in this, publishing no less than seven op-eds and organising two media seminars together with the Chinese embassy directly referencing Wells’ criticism.Footnote28 Bilateral cooperation in the media sector is being further institutionalised through content-sharing agreements carrying Chinese messaging on CPEC to a Pakistani audience. In September 2021, the two sides agreed to establish a ‘media corridor’, specifically intended to counter foreign ‘fake news and propaganda jeopardizing the Pak–China relationship and CPEC’ (S. Ali Citation2021).

In summary, the political strategy that China and its local allies employed to strengthen support for CPEC went far beyond the elite cooptation model China has used elsewhere to promote the BRI. It included outreach to many actors that have to be considered peripheral or marginal to Pakistan’s governing processes: minority and regional parties, individual experts, intellectuals and community leaders, and the public at large through traditional and social media channels. This, too, represents a significant departure from previous interpretations of ‘non-interference’ in the domestic politics of other states. It is also evidence of the Centre–Periphery relationship at work, and in fact mirrors the dense, multi-channel relations which the US has developed with its own allies. The strategy has proven highly successful in insulating CPEC against political power shifts: an important success was achieved in managing the 2018 government turnover, bringing the previously sceptical Imran Khan and his new administration on board with CPEC, and arguably establishing the broadest domestic elite consensus since its onset. Khan’s ouster by a no-confidence vote in 2022, which returned a PML-N led coalition to power and resulted in Shehbaz Sharif’s election to prime minister, is likely to continue this trend. The coalition parties are unanimous in their support for CPEC, and several of the new members of government are outspoken proponents and alumni of formats like the JCM. The new premier is known for his personal enthusiasm for CPEC, penchant for mega-projects and facilitating their rapid implementation.Footnote29 Changes to the project may affect its domestic governance – like abolishing the CPEC Authority and re-strengthening civilian control – but not its fundamental progress.Footnote30

Among ordinary Pakistani citizens, China continues to enjoy a highly positive image and a great deal of trust (Pew Research Citation2015), while the activities of Chinese companies there received a 63% approval in a Chinese survey, far higher than the 44% average in a sample of BRI countries (ACCWS/Kantar 2020). Crucially, with the exception of some separatist groups in Balochistan, most of the remaining CPEC critics do not disagree with the project as a whole, but in fact often want a bigger piece of it. The failure to achieve a more equitable distribution is blamed not on China but on authorities in Islamabad and the shortcomings of Pakistan’s own political system – in fact, this was a unanimous view among interviewees for this paper, regardless of their attitude towards CPEC.

Accordingly, the work on a joint strategy to promote CPEC has strengthened ties at the international level and indeed established a ‘community of common destiny’ between Beijing and Islamabad. The BRI outcomes the two sides negotiated are not a case of China imposing strategic designs on a peripheral neighbour; they also reflect the interests of local elites, who subsequently rallied in defence of the project. This is particularly important at a time of rising international tensions between China and the US, and accompanying inner-Pakistani debates over which side (if any) their country should take: to China-leaning elites, CPEC is proof of China’s economic and strategic commitment to Pakistan, and provides a cornerstone for the further development of social and intellectual ties. External (especially Indian and Western) criticism of CPEC has actually reinforced this international realignment, as Pakistani elites consider the narrative that they are being snared into a ‘debt trap’ to be baseless and insulting.Footnote31 At the same time, the genuine problems with CPEC – mainly its pursuit without meaningful input from peripheral constituencies – have exacerbated tensions within Pakistan, and whether the intensified political outreach will prove effective at this level remains to be seen.

Conclusion

CPEC has its origins in two separate but overlapping visions of how to reorder political spaces by means of infrastructure, in which ambitious ‘centres’ sought to tie their respective peripheries closer to themselves. These have been realised to different extents, and not always in line with the original designs: at the international level, CPEC has locked Pakistan into a close, and arguably symbiotic, partnership with China. Despite a widening economic crisis, Chinese capital has flooded into the country and allowed the pursuit of an extremely ambitious industrialisation strategy, with substantial early results in the energy sector. This relationship can build on long-established strategic trust, mutually compatible notions of the national interest, and increasingly closely connected policy communities – not unlike the factors undergirding transatlantic ties. From a Chinese perspective, CPEC has delivered on many of the sought-after benefits of centrality: the ability to implement grand strategic visions, the close diplomatic and economic alignment of one of its largest neighbours, and the political flattery from abroad which the CCP increasingly demands. However, this relationship is not one-sided – it has also tied China irrevocably into Pakistan’s complicated, and sometimes hostile, political landscape. As China seeks to reshape the world through infrastructure and has made the BRI the centrepiece of its bid for greater status, the pathways so created also exert a transformative pressure back on China itself, moving foreign threats closer to it and the national consciousness. Setbacks in Pakistan are contributing to debates over the future of China’s diplomatic and security policies, which are trending in a more interventionist direction. At least in the short term, China’s engagement in Pakistan is likely to focus on domestic security efforts like counterterrorism, surveillance and intelligence-sharing rather than outright military efforts, although the physical infrastructure of CPEC would also make the latter easier.

Within Pakistan, CPEC has not been able to deliver on all of its overly ambitious promises, especially when it comes to the integration of peripheral regions and groups. On the one hand, CPEC has become a rallying point for political parties across the spectrum, and a robust elite consensus in its favour is being maintained with a sophisticated and multi-pronged strategy. On the other, violent resistance among separatists and distributional conflicts inside Pakistan continue to plague the project. From this perspective, CPEC is a cautionary tale for how such projects can overwhelm political institutions ill-equipped to handle them. In a fragmented country with low levels of trust in the central government, neither the restrictive information policy surrounding CPEC nor the top-down mode of implementation was appropriate. As these problems became apparent, China and Islamabad moved quickly to shore up support – which has, however, focused more on obtaining symbolic statements of loyalty than addressing underlying grievances. Given the apparent lack of domestic capacities or will to effectively address them, Chinese agency – as is already underway in the fields of CSR and education – is likely to be decisive here. This, too, may turn out to be another way in which China ultimately emulates the way Western ‘centres’ have been interacting with their global peripheries, and in which the BRI draws China out of its previous comfort zone even as its global influence continues to grow.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to the two anonymous reviewers, the participants of a 2021 virtual conference on CPEC, and Jonas Wolff for offering their feedback on my evolving manuscript. Research on this article began in late 2020, when international travel was impossible under pandemic restrictions, and local sources could only be contacted remotely. This effort would not have gotten off the ground without the help of Farooq Yousaf, who introduced me to many knowledgeable contacts in Pakistan and abroad. In 2022, proper field research was finally made possible thanks to a grant from the Stiftung Ökohaus Foundation and Hasan Karrar, who hosted me at Lahore University of Management Sciences. Finally, I am particularly grateful to the many interviewees who gave their views on CPEC and its controversial effects on condition of anonymity.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Pascal Abb

Pascal Abb is a senior researcher at the Peace Research Institute Frankfurt (PRIF), focusing on how a rising China interacts with global conflict environments. He is currently conducting a research project on the impact of the Belt and Road Initiative on conflict-affected states. His latest publications are ‘Road to Peace or Bone of Contention? The Impact of the Belt and Road Initiative on Conflict States’ (with Robert Swaine and Ilya Jones, PRIF Report 1/2021) and ‘From “Peaceful Rise” to “Peacebuilder”? How Evolving Chinese Discourses and Self-Perceptions Impact Its Growing Influence in Conflict Societies’ (Journal of Contemporary China 30 (129), 2021).

Notes

1 Interview with an academic expert on CPEC.

2 Interview with a Baloch politician.

3 Based on a query of the Global Terrorism Database (LaFree and Dugan Citation2007) of all terror incidents in Pakistan during this time period that had a relation to CPEC or other Chinese projects in the country.

4 Interview with an advisor to the government of Balochistan.

5 Interview with a Baloch politician.

6 Interview with an academic expert on CPEC and an expert on Pakistani civil–military relations.

7 Interviews with two think tank experts and a CPEC Authority official.

8 Interview with two academic experts on CPEC and a Pakistani think tank expert.

9 Interview with a Chinese resident scholar in Pakistan.

10 Interviews with a former advisor to the government of Khyber-Pakhthunkwa and a Baloch politician.

11 Interviews with a former advisor to the government of Khyber-Pakhthunkwa and a Baloch politician.

12 Interviews with two Pakistani non-governmental organisation (NGO) representatives.

13 Interview with an academic expert on CPEC.

14 Interview with a journalist based in Balochistan.

15 Interview with a Pakistani expert on civil–military relations.

16 Interview with an academic expert on CPEC.

17 See a recording of senator Sherry Rehman’s speech to the 2nd JCM meeting (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a4pc7Xh7874) and a recording of the ‘Webinar on

Balochistan’s Political Parties’ Dialogue’ organized by the Emerging Policymakers Institute (https://www.facebook.com/epi.org.pk/videos/1660403694126379).

18 Interview with a PCI executive.

19 Based on entries on the PCI website (pakistan-china.com) and its affiliated CPEC information platform (cpecinfo.com).

20 Interviews with a former advisor to the government of Khyber-Pakhthunkwa, 22 November 2020, and an advisor to the government of Balochistan.

21 Interviews with two think tank experts specialising in China–Pakistan relations, and a journalist.

22 Interview with a journalist based in Balochistan.

23 Interview with an advisor to the Balochistan provincial government.

24 Interview with an academic expert on CPEC.

25 Interview with an academic expert on CPEC.

26 Interview with a CPEC Authority official.

27 Interview with a think tank expert.

28 Based on entries on the PCI website (pakistan-china.com) and its affiliated CPEC information platform (cpecinfo.com).

29 Interview with a businessman and former member of the Gwadar board.

30 Interviews with two NGO representatives.

31 Interviews with multiple Pakistani think tank experts, scholars and officials.

Bibliography

- Aamir, A. 2019. “The Myth of CPEC’s Western Route.” The Friday Times, November 8, 2019.

- Aamir, A. 2020. “Pakistan and CPEC Are Drawn into the U.S.-China Rivalry.” China Brief 20 (1): 18–23.

- Abb, P. 2016. “China’s New Think Tank Diplomacy.” ECFR China Analysis, August 2016.

- Abb, P., R. Swaine, and I. Jones. 2021. “Road to Peace or Bone of Contention? The Impact of the Belt and Road Initiative on Conflict States.” PRIF Report 1/2021.

- Academy of Contemporary China and World Studies (ACCWS)/Kantar. 2020. Chinese Enterprise Global Image Survey Report 2020, BRI Edition (Zhongguo Qiye Haiwai Xingxiang Diaocha Baogao 2020, ‘Yidaiyilu’ Ban). Beijing: ACCWS.

- Adeney, K. 2012. “A Step Towards Inclusive Federalism in Pakistan? The Politics of the 18th Amendment.” Publius: The Journal of Federalism 42 (4): 539–565. doi:10.1093/publius/pjr055.

- Afzal, M. 2020. “At All Costs: How Pakistan and China Control the Narrative on the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor.” Brookings Report, June 2020.

- Ahmed, Z. S. 2019. “Impact of the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor on Nation-Building in Pakistan.” Journal of Contemporary China 28 (117): 400–414. doi:10.1080/10670564.2018.1542221.

- Akhter, M. 2015. “Infrastructure Nation: State Space, Hegemony, and Hydraulic Regionalism in Pakistan.” Antipode 47 (4): 849–870. doi:10.1111/anti.12152.

- Ali, M. 2020. “China–Pakistan Economic Corridor: Prospects and Challenges.” Contemporary South Asia 28 (1): 100–112. doi:10.1080/09584935.2019.1667302.

- Ali, S. 2021. “Pakistan, China Media to Jointly Counter False Propaganda.” The Nation, September 29, 2021.

- Bansal, A. 2008. “Factors Leading to Insurgency in Balochistan.” Small Wars & Insurgencies 19 (2): 182–200. doi:10.1080/09592310802061356.

- Bengali, K. 2015. China-Pakistan Economic Corridor: The Route Controversy. Quetta: Government of Balochistan.

- Blanchard, J-M., and Colin F. 2017. “The Geopolitics of China’s Maritime Silk Road Initiative.” Geopolitics 22 (2): 223–245. doi:10.1080/14650045.2017.1291503.

- Boni, F. 2020. Sino-Pakistani Relations: Politics, Military and Security Dynamics. London: Routledge.

- Boni, F., and K. Adeney. 2020. “The Impact of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor on Pakistan’s Federal System: The Politics of the CPEC.” Asian Survey 60 (3): 441–465. doi:10.1525/as.2020.60.3.441.

- Boni, F., and K. Adeney. 2021. How Pakistan and China Negotiate. Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment.

- Callahan, W. 2016. “China’s ‘Asia Dream’: The Belt Road Initiative and the New Regional Order.” Asian Journal of Comparative Politics 1 (3): 226–243. doi:10.1177/2057891116647806.

- China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). 2021. “CPEC Official Website: Energy.” http://cpec.gov.pk/energy

- Express Tribune. 2020. “Political Parties Unite to Support ‘Game-Changer’ CPEC.” Express Tribune, August 20, 2020.

- Ferdinand, P. 2016. “Westward Ho – The China Dream and ‘One Belt, One Road’: Chinese Foreign Policy under Xi Jinping.” International Affairs 92 (4): 941–957. doi:10.1111/1468-2346.12660.

- Foreign Ministry of the People’s Republic of China (FMPRC). 2022. “Li Keqiang Speaks with Pakistani Prime Minister Shahbaz Sharif on the Phone." Accessed June 2, 2022. https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/zxxx_662805/202205/t20220516_10686660.html

- Galtung, J. 1971. “A Structural Theory of Imperialism.” Journal of Peace Research 8 (2): 81–117. doi:10.1177/002234337100800201.

- Garlick, J. 2022. Reconfiguring the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor: Geo-Economic Pipe Dreams Versus Geopolitical Realities. London: Routledge.

- Ghiselli, A. 2021. Protecting China’s Interests Overseas: Securitization and Foreign Policy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Gill, B. 2020. “China’s Global Influence: Post-COVID Prospects for Soft Power.” The Washington Quarterly 43 (2): 97–115. doi:10.1080/0163660X.2020.1771041.

- Gitter, D., J. Bowie, and N. Callen. 2019. “CCP Watch Weekly Report 3.16.2019-3.20.2019.” Accessed September 9, 2021. https://www.ccpwatch.org/single-post/2019/03/25/weekly-report-222-3162019-3202019

- Global Times. 2021. “Terrorists Attacking Chinese: Though You Are Far Away, You Will Be Punished (Dui Zhongguoren Shishi Kongxizhe, Sui Yuan Bi Zhu).” Global Times, 16 July 2021.

- Gwadar Port Authority (GPA). 2002. “Gwadar Port Authority Ordinance LXXVII of 2002.” Accessed August 31, 2021. http://www.gwadarport.gov.pk/file/ordinance%20gpa.pdf

- Haider, Z. 2005. “Sino-Pakistan Relations and Xinjiang’s Uighurs: Politics, Trade, and Islam along the Karakoram Highway.” Asian Survey 45 (4): 522–545. doi:10.1525/as.2005.45.4.522.

- Hameed, M. 2018. “The Politics of the China – Pakistan Economic Corridor.” Palgrave Communications 4 (1): 64. doi:10.1057/s41599-018-0115-7.

- Hillman, J. 2020. The Emperor’s New Road: China and the Project of the Century. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Husain, K. 2017. “Exclusive: CPEC Master Plan Revealed.” Dawn, June 21, 2017.

- Hussain, E., and M. Rao. 2020. “China–Pakistan Economic Cooperation: The Case of Special Economic Zones (SEZs).” Fudan Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences 13 (4): 453–472. doi:10.1007/s40647-020-00292-5.

- Jiang, H. 2015. “Evaluation and Management of Geopolitical Risks in the ‘Belt and Road’ (‘Yidaiyilu’ Diyuan Zhengzhi Fengxian De Pinggu Yu Guanli).” International Trade 8/2015.

- Joint Consultation Mechanism (JCM). 2019. “Beijing Declaration of the First Meeting of the CPEC Political Parties.” Published online by a participant. https://twitter.com/qasimkhansuri/status/110800058361987481

- Kang, D. 2010. “Hierarchy and Legitimacy in International Systems: The Tribute System in Early Modern East Asia.” Security Studies 19 (4): 591–622. doi:10.1080/09636412.2010.524079.

- Khan, A. 2009. “Renewed Ethnonationalist Insurgency in Balochistan, Pakistan: The Militarized State and Continuing Economic Deprivation.” Asian Survey 49 (6): 1071–1091. doi:10.1525/as.2009.49.6.1071.

- Khan, I. 2017. “China to Get 91pc Gwadar Income, Minister Tells Senate.” Dawn, November 25, 2017.

- Lafree, G., and L. Dugan. 2007. “Introducing the Global Terrorism Database.” Terrorism and Political Violence 19 (2): 181–204. doi:10.1080/09546550701246817.

- Layton, P. 2020. “Artificial Intelligence, Big Data and Autonomous Systems along the Belt and Road: Towards Private Security Companies with Chinese Characteristics?” Small Wars & Insurgencies 31 (4): 874–897. doi:10.1080/09592318.2020.1743483.

- Liu, Z. 2015. “Current Status, Problems and Countermeasures for China’s ‘Belt and Road’ Initiative in the Southeastern and Southwestern Periphery (Woguo ‘Yidaiyilu’ Changyi Zai Dongnan, Xinan Zhoubian Jinzhan Xianzhuang, Wenti Ji Duice).” Indian Ocean Economic and Political Review 4: 92–109.

- Ma, Y. 2015. “Risk Management Issues in the Construction of the "Belt and Road" (‘Yidaiyilu’ Jianshe Zhong De Fengxian Guankong Wenti).” China Review of Political Economy 6 (04): 189–203.

- Mangi, F. 2022. “Cash-Strapped Pakistan Cuts Power to Households on Fuel Shortage.” Bloomberg, April 18, 2022.

- Markey, D. 2020. China’s Western Horizon: Beijing and the New Geopolitics of Eurasia. New York: Oxford University Press.

- McCartney, M. 2021. The Dragon from the Mountains: CPEC From Kashgar to Gwadar. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Ministry of Planning, Development and Reform and National Development and Reform Commission (MPDR/NDRC). 2017. “Long-Term Plan for China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (2017-2030).”

- Mustafa, D. 2021. Contested Waters: Sub-National Scale Water and Conflict in Pakistan. London: I.B. Tauris.

- Najam, A., and F. Bari. 2017. Pakistan National Human Development Report. New York: United Nations Development Programme.

- Palmer, A. 2021. “The Man Behind China’s Aggressive New Voice.” The New York Times, July 7, 2021.

- Pakistan-China Institute (PCI). 2020. “Projects: Research and Education.” Accessed October 20, 2021. https://www.pakistan-china.com/mn-research-and-education.php

- Pew Research). 2015. “Global Indicators Database: Pakistan.” Accessed October 5, 2022. https://www.pewresearch.org/global/database/indicator/24/country/pk/

- Reeves, J. 2018. “Imperialism and the Middle Kingdom: The Xi Jinping Administration’s Peripheral Diplomacy with Developing States.” Third World Quarterly 39 (5): 976–998. doi:10.1080/01436597.2018.1447376.

- Rolland, N. 2017. China’s Eurasian Century? Political and Strategic Implications of the Belt and Road Initiative. Seattle: National Bureau of Asian Research.

- Safdar, M. 2021. The Local Roots of Chinese Engagement in Pakistan. Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment.

- Scissors, D. 2019. China Global Investment Tracker. Washington, DC: American Enterprise Institute. https://www.aei.org/china-global-investment-tracker/

- Shah, S. A. 2015. “Economic Corridor: ANP Denounces Change in Route, Calls APC.” Dawn, May 1, 2015.

- Small, A. 2020. Returning to the Shadows: China, Pakistan, and the Fate of CPEC. Washington, DC: German Marshall Fund.

- Swaine, M. “Chinese Views and Commentary on Periphery Diplomacy.” China Leadership Monitor 44, no. 1 (2014): 1–43.

- Tan, C. 2015. “Chinese Enterprises’ Overseas Investment Risks and Countermeasures under the ‘Belt and Road’ Strategy (‘Yidaiyilu’ Zhanlüe Xia Zhongguo Qiye Haiwai Touzi Fengxian Ji Duice).” China Circulation Economy 29 (7): 114–118.

- Waseem, M. 2011. “Patterns of Conflict in Pakistan: Implications for Policy." Brookings Working Paper No. 5, January 2011.

- Wolf, S. 2020. The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor of the Belt and Road Initiative. Cham: Springer.

- Yao, Y. 2015. “Analysis of Risks Facing the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (Zhong-Ba Jingji Zoulang Mianlin De Fengxian Fenxi).” South Asian Studies 2: 35–45.

- Younus, U. 2021. “Pakistan’s Growing Problem with Its China Economic Corridor." United States Institute of Peace. Accessed October 27, 2021. https://www.usip.org/publications/2021/05/pakistans-growing-problem-its-china-economic-corridor

- Zhang, F. 2019. “The Xi Jinping Doctrine of China’s International Relations.” Asia Policy 26 (3): 7–23. doi:10.1353/asp.2019.0029.

- Zhang, Y. 2016. “Baloch Separatist Forces Views on the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor and Causes (Biluzhi Fenlizhuyi Shili Dui Zhongbajingjizoulang De Kanfa Jiqi Chengyin).” South Asian Studies 2: 24–42.

- Zheng, G. 2016. “Strategic Challenges to the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, Grand Strategy and Policy Suggestions (Zhong-Ba Jingji Zoulang De Fengxian Tiaozhan, Da Zhanlüe Sikao Jiqi Duice Jianyi).” Pacific Journal 24 (04): 89–95.

- Zhou, P. 2016. “Geopolitical Risks Faced by the “Belt and Road” and Their Management. (‘Yidaiyilu’ Mianlin De Diyuan Zhengzhi Fengxian Ji Qi Guankong).” Exploration and Free Views 1: 83–86.