Abstract

Scholarly calls in the discipline of international relations (IR) for a more intimate and substantive dialogue between the disciplinary core and the periphery to fashion a truly ‘global’ IR have proliferated. The pivotal question is how to ensure the emergence of a veritable dialogue between the core and the periphery in a truly global discipline. In this article, first, it is contended that the current conditions of epistemic hierarchy and asymmetrical dialogue emanate from the epistemic gravity of the core based on its power of appeal. Second, in order to correct the abiding disciplinary asymmetry, dialogue with the periphery needs to become a matter of necessity for the core instead of a matter of choice. Third, to that end, the augmentation of the epistemic gravity of the periphery and its own power of appeal is required. Fourth, one promising path of increasing the epistemic gravity of the periphery is to foster its thematic density. To illustrate these points, a case study of Turkish IR academia is presented with reference to the global/local distribution of the universities from which IR scholars in Turkey have received their doctoral degrees.

Introduction

Scholarly calls have proliferated in the discipline of international relations (IR) for a more intimate and substantive dialogue between the disciplinary core and the periphery to fashion a truly ‘global’ IR (Acharya Citation2011, Citation2016; Kristensen Citation2015a; Acharya and Buzan Citation2017). Nonetheless, the very binary designation of core–periphery is a testament to the abiding epistemic hierarchy in global scholarship in which the core assumes a privileged position in the production and dissemination of knowledge while the periphery ‘is assigned a consumptive role due to its perceived inability to produce original scholarship, which then reinforces and sustains the asymmetrical patterns of dialogue and exchange’ (Turton Citation2016, 70).

The pivotal question is how to ensure the emergence of a true dialogue between the core and the periphery in a truly global discipline. In this article, first, it is contended that the current conditions of epistemic hierarchy and asymmetrical dialogue emanate from the epistemic gravity of the core based on its power of appeal. Second, in order to correct the abiding disciplinary asymmetry, dialogue with the periphery needs to become a matter of necessity for the core instead of a matter of choice. Third, it is further argued, rendering dialogue with the periphery a matter of necessity for the core entails, in turn, the augmentation of the epistemic gravity of the periphery and its own power of appeal. And, fourth, one promising path to increasing the epistemic gravity of the periphery is to foster its thematic density.

This article is organized as follows: First, the abiding asymmetry in global knowledge flows and the nexus between knowledge and power in the discipline is reaffirmed. Second, the forms of disciplinary power relations are discussed. Besides the power of coercion and the power of consent, another form of power in operation, which is called ‘the power of appeal’, is set forth. The power of appeal is conceptualised as the foundation of epistemic gravity. Subsequently, the constitutive interactions between epistemic gravity and dialogue are debated and rationales behind the peripheral dialogue are explored. Fourth, an alternative conception of disciplinary dialogue is propounded based on a classification that comprises dialogue of choice and dialogue of necessity. It is emphasised that while dialogue is mostly a matter of choice for the core, it is mostly a matter of necessity for the periphery.

Fifth, the measures required to augment the epistemic gravity of the periphery, and thereby to rectify the prevailing asymmetries in the production, dissemination and consumption of knowledge between the core and the periphery, are addressed. To that end, in addition to theoretical ingenuity and methodological proficiency, thematic density is introduced as a third alternative course. Finally, in order to illustrate the epistemic gravity entertained by the core and experienced by the periphery and its dialogic implications for the discipline, a case study of Turkish IR academia is presented with reference to the global/local distribution of the universities from which IR scholars in Turkey have received their doctoral degrees.

Hierarchy, asymmetry and power in global IR: the power of appeal

The disciplinary epistemic hierarchy in IR is the outcome of asymmetrical knowledge flows due to the functionally differentiated knowledge production in the discipline between a core and a periphery. As analytical categories, it should be noted, the core and the periphery do not represent unitary and uniform entities. Within both the core and the periphery, there are hierarchical patterns characterised by internal cores and peripheries (Aydınlı and Mathews Citation2000). One study notes the presence of spatial stratification structures within the IR academia in the United States (US), in which knowledge production is dominated by institutions of higher education located in Northeast US (Kristensen Citation2015b). Another study presents an incisive critique of the emergence of ‘new layers of epistemic hegemony and knowledge-production hierarchies’ within the periphery itself (Carrozza and Benabdallah Citation2022, 16).

In addition to internal heterogeneity and variation, there also exist interpenetrations between the core and the periphery. From a sociological point of view, for example, it is contended that societal groups, such as immigrant communities, constitute peripheral bodies within Western societies (Sajed Citation2020). From the perspective of disciplinary sociology, global IR is characterised by networks of mobility between the core and the periphery with scholars from the periphery working at core universities and scholars from the core working at peripheral universities. However, these two sets of disciplinary communities can be subject to different opportunity structures and institutional constraints. As an example, despite working at universities in the United Kingdom (UK), scholars from the periphery have to endure demanding (in terms of time, money, patience, and energy) visa application processes to be able to attend academic conferences in the US. For their fellow colleagues from the UK and other core countries working at universities in the UK, this is a non-issue. In another example of interpenetration between the core and the periphery, several institutions of higher education located in the core now have local branches in different countries of the periphery. In short, internal stratified heterogeneities within the core and the periphery and multiple forms of mutual interpenetration between the two need to be kept in mind in discussions of epistemic hierarchies and asymmetrical knowledge flows in global IR.

In global IR, while epistemic agency, ie the capacity to generate and deliver authentic and credible knowledge, is accorded to the core, the peripheral scholarship is relegated to a role of ‘native informants’ (Kristensen Citation2015c), culminating in an intellectual division of labour in the discipline (Niang Citation2016; Maliniak et al. Citation2018). Still, the consumptive dependency of the periphery on the productive agency of the core is critically attested to and analysed in several studies, especially by scholars in the periphery (Aydınlı and Mathews Citation2008). It is contended that there exists ‘a dual mechanism that reinforces the core–periphery hierarchy in IR in both quantity and quality’ (Turton and Freire Citation2016, 535). There is, on the one hand, ‘an asymmetry in the volume of the exchange of ideas across both sides, with a great quantity of publications, conferences and university professorships at the core contrasted with the scarcity of research and pedagogical resources on the periphery’, and, on the other hand, ‘an asymmetry in the type of knowledge flows across both sides, notably with the periphery’s dependence on the core’s theoretical production’ (Turton and Freire Citation2016, 535). Accordingly, as indicated by many a scholar, ‘while diversity in IR may be improving, the flow of knowledge has remained unidirectional’ (Odoom and Andrews Citation2017, 42).

As one of the causes of this differentiated knowledge production in the discipline, the initial emergence of an extensive, dynamic and productive IR scholarship concomitant with a high degree of institutionalisation in the core/West, especially the US, is advanced (Cotton Citation2009; Taylor Citation2012). A crucial parameter that has contributed to the perpetuation of the foremost position of the core in the global epistemic hierarchy in IR is the ‘ontological’ innovative capacity of the core. Effects of the shifts in the material conditions on knowledge production tend to be discounted in analyses of the sources of asymmetrical knowledge flows in the discipline. For example, emergence of the nation state as a sociopolitical institutional innovation first in Europe compelled Western scholarship to engage this new phenomenon and to produce an extensive intellectual body of work on nation states. The spread of the nation state to other parts of the globe was accompanied by the spread of Western conceptions of nation state the world over (Opello and Rostow Citation1999).

Technological innovations, as another example, are a major variable that induce significant shifts in the material conditions, which in turn stimulate relevant knowledge production in IR (Hoijtink and Leese Citation2019). Therefore, the creativity of the core in technological innovations has afforded it a leading starting point as well as a constant distance in knowledge production. Only with the spread of technological innovations, or at least their effects, has emerged the interest in and necessity of acquiring the relevant knowledge about them in the periphery. As an example, the capacity to manufacture nuclear weapons brought about contemplations on nuclear strategy in the US, and in the process a body of literature on different aspects of nuclear strategy was generated locally. This body of literature was to be consulted by the epistemic communities of the subsequent nuclear-capable states afterwards. The same process of core-dominated knowledge production is observable today in the fields of artificial intelligence and autonomous weapons systems, and their implications for IR (Garcia Citation2018; Bode and Huelss Citation2018).

Asymmetrical knowledge flows and the resultant epistemic hierarchy in the discipline have elicited impassionate discussions on the nexus between knowledge and power from a variety of perspectives. One observation related to the prospects of global dialogue is the emergence of certain states as alternative centres of influence and affluence in international affairs. It is highlighted, for instance, that ‘during the last decades … there have been inclinations toward new conceptualizations by IR scholars from India and China that can be related to their emerging agency in the world’ (Moshirzadeh Citation2018, 90). In a similar vein, Acharya (Citation2011, 625) states, ‘one probably would not hear much about a Chinese School of IR if China was not a “rising” power’.

In specifying the power relations underpinning the entitled epistemic status of the core in the discipline, a scholar draws a distinction between dominance and hegemony, the first being associated with coercion and the second with consent (Turton Citation2016). A Gramscian understanding of hegemony is espoused, which is ‘a special kind of social power relation in which dominant groups secured their positions of privilege largely (if by no means exclusively) thorough consensual means’ (Rupert Citation2009, 177). In short, academics ‘adopt different conceptualizations and understandings of how American dominance/hegemony operates in the discipline’ (Turton Citation2016, 8). Notwithstanding this, the general consensus appears to be that the dominance and hegemony of the core are underpinned by negative and positive inducements, respectively, associated with coercion and consent.

Nonetheless, there exists a wide range of academic practices in the discipline outside the explanatory purview of coercion and consent. One Brazilian scholar castigates, as an example, some other Brazilian scholars, both senior and junior, for their senseless avidity, in that scholar’s view, for the annual International Studies Association (ISA) conferences. They opine that ‘for them “that’s the meeting I absolutely have to go to even if I have to sell my apartment to pay for my trip [laughing] and I have to send lots of proposals because I cannot afford to not be accepted.” The students go crazy … you sell your dog, your car and then you go’ (cited in Kristensen Citation2019, 486). In Turkey, not infrequently, instead of selling their assets, PhD students and junior scholars take out loans from banks to afford participation in the annual ISA conferences. It appears difficult to explain these behaviours with reference to coercion or consent. There seems to be an attraction so irresistible that scholars feel compelled to respond to its gravitational pull, at times by voluntarily assuming heavy financial burdens. These individual decisions are affected by the prevailing global systemic structure of asymmetrical privilege in the production, dissemination, and consumption of knowledge, and in turn, serve to affect and perpetuate it.

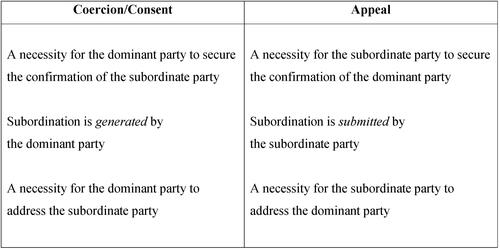

There is a third form of power relationship that underpins the epistemic hierarchy in the discipline apart from coercion and consent. In both coercion and consent, there exists a necessity for the dominant party to secure the confirmation of certain views, the endorsement of certain attitudes, and the performance of certain acts by the subordinate party. The dominant party is in need of the subordination of the subordinate party, attained either through coercion or consent. In brief, subordination is generated by the dominant party. Accordingly, in a dialogue of dominance marked by coercion or in a dialogue of hegemony marked by consent, it is a necessity for the dominant party to address the subordinate party.

Nevertheless, there exists a third form of power relationship, which can be called ‘appeal’. In appeal, in contrast to both coercion and consent, there exists a necessity for the subordinate party to secure the confirmation of certain views, the endorsement of certain attitudes, and the performance of certain acts by the dominant party. Here, the dominant party is not in need of the subordination of the other party. In brief, subordination is not generated by the dominant party. On the contrary, subordination is submitted by the subordinate party. Accordingly, in a dialogue marked by the power of appeal, it is not a necessity for the dominant party to address the subordinate party. On the contrary, it is a necessity for the subordinate party to address the dominant party.

To put it succinctly, in coercion and consent, the dominant party is invested in the relationship with the subordinate party. The dominant party necessarily cares about the relationship. In appeal, the subordinate party is invested in the relationships with the dominant party, and yet, the dominant party does not necessarily care about the relationship. Nonetheless, coercion/consent and appeal are not mutually exclusive; they can be simultaneously in operation in power relationships, and mostly they are.

As an example, many universities in the core charge fees for the posts of visiting scholarships and fellowships, and many academics from the periphery are more than ready to pay these sometimes exorbitant fees. It appears challenging to explain this behaviour of peripheral scholars to incur substantial amounts of financial costs for short-term visiting posts at core universities with reference to the power of coercion or consent.Footnote1 It becomes comprehensible, though, with reference to the power of appeal. There is a perceived necessity for the peripheral academic to address the core academia and to secure its confirmation which validates her/his scholarship through the provision of the post. Here, subordination is submitted by the peripheral scholar; an individual submission not necessarily cared about by the core university – as is obvious from the arbitrary financial barriers. On the other hand, so as to attract peripheral talent and expertise for permanent posts, core universities frequently exercise the power of consent, and have recourse to positive inducements of various sorts. Here, they necessarily care about the relationship. In brief, the power of appeal differs from the power of coercion and the power of consent; still, it exists and operates simultaneously with them ().

The power of appeal is the foundation of ‘epistemic gravity’. Using an analogy from the natural sciences, the gravity of objects rests in their mass, and the higher their mass, the higher their gravity. Likewise, the epistemic gravity of sites of knowledge rests on their power of appeal, and the higher their power of appeal, the higher their epistemic gravity. The epistemic hierarchy in the discipline is the result of differential epistemic gravities between the core and the periphery. The meta-dialogical question here is: How to ‘dialogue’ in a condition of differential epistemic gravities in which the power of appeal of the core overwhelmingly exceeds that of the periphery? To find a promising answer to this question, first, the concerns of the periphery in its dialogue with the core need to be examined.

Epistemic gravity and dialogue in IR: peripheral concerns

Power bends dialogue as gravity bends light.Footnote2 In IR, achieving a veritable ‘dialogue’ in a condition of differential epistemic gravities represents a disciplinary challenge. It is underlined, for example, that ‘power structures and intellectual predispositions, shaped by history and identity, stand in the way of acknowledging the agency and contribution of other voices, even when one knows them to be out there’ (Acharya Citation2011, 636–637). Contrary to the assertion that there exists no meaningful dialogue in the discipline between the core and the periphery, there does exist a forceful dialogue that originates in the periphery and orients towards the core. This dialogic orientation is conditioned by the epistemic gravity of the core.

There appear to be three rationales for the peripheral dialogue. The first is the desire to acquire substantive knowledge produced by the core. The core functions as the site for the acquisition of knowledge represented by higher education institutions and specialised research centres on many a dimension of international affairs. The second is the desire to acquire instrumental knowledge. The core similarly functions as the site for the cultivation of knowledge about the modes and methods of scholarly performance (Aydinli Citation2020). Here, modes of scholarly performance involve a wide range of practices from writing academic papers to supervising students, learning theory and applying methodology. Theory can be considered instrumental knowledge as it is a mode of perceiving and conceiving the world. Likewise, methodology is a mode of collecting and processing information.

The third rationale for the peripheral dialogue is the desire to acquire recognition that is accorded by the core. The core functions as the site for recognition as well as the conferrer of recognition. The core is the disciplinary locality where substantive knowledge and instrumental knowledge is acquired. More importantly, it is arguably more critical for the peripheral dialogue as recognition delivered by the core confers validation on legitimate scholarship involving both scholars themselves and the knowledge they produce. As one example, the acceptance of an article for publication in a Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI) journal is a prerequisite for graduating from some PhD programmes in the periphery of the global IR. It is taken as the validation of scholarship akin to a ceremony of initiation into an epistemic order. Desire for recognition and relevance, and the social and material benefits associated with them, is a potent motive behind the peripheral dialogue. Recognition is even advanced as a strategic means to resist dominance in the discipline. For instance, it is argued that ‘by establishing a dialogue with the mainstream, gaining recognition from the “core” due to its familiar appearance, peripheral scholarship presents itself as a challenge from within’ (Turton and Freire Citation2016, 551).

Furthermore, recognition is the critical rationale for the peripheral dialogue arguably since its absence is tantamount to marginalisation of peripheral scholarship, scholars, and knowledge alike. ‘Peripheral scholars have little choice, it is argued, but to conform to and work within the defined theoretical boundaries [of the core] or face further marginalization’ (Turton Citation2016, 53). Fear of marginalisation and irrelevance, and the associated social and material costs, is a strong motive behind the peripheral dialogue. One of the outcomes of the peripheral dialogue taking place in a condition of differential epistemic gravities between the core and the periphery is a certain mode of socialisation in the discipline. ‘Socialization into this competitive environment’, it is asserted, ‘requires imitation and utilization of those core ideas as reference points; for otherwise periphery scholars are regarded as less than competent’ (Aydınlı and Biltekin Citation2018a, 3). This mode of socialisation serves to sustain and enhance the epistemic gravity of the core for which dialogue with the periphery is only matter of choice, and not a matter of necessity.

Dialogue between the core and the periphery in global IR: dialogue of choice, dialogue of necessity

The meaning of asymmetry in dialogue needs to be investigated prior to any discussion of the dialogue taking place between the core and the periphery in the contemporary global IR. Asymmetry in dialogue can take two forms. One can be called quantitative asymmetry. Assuming that there are just two participants in the dialogue, in quantitative asymmetry, the expressions of one side, in oral or written forms, enjoy a greater share of the conversation. In the global IR, for example, the core retains a greater share of reciprocal academic exchange with the periphery in quantitative terms in a specific period of time, such as the number of publications it produces, or the number of citations it procures (Risse, Wemheuer-Vogelaar, and Havemann Citation2022).

In qualitative asymmetry, on the other hand, the expressions of one side enjoy greater influence in the conversation, even though it does not necessarily have a greater quantitative share. In this case, one side’s contribution to the conversation weighs more than the other side’s contribution in qualitative terms, such as authenticity, prestige, credibility or authority. In the global IR, for example, one article in a core journal by an academic from a core university would enjoy a higher ‘impact factor’ than another article in a periphery journal by an academic from a periphery university, regardless of the essential quality of the research.Footnote3 The current dominance of the core in the discipline predicates on the presence of both the quantitative and the qualitative asymmetry in favour of the core.

The global IR scholarship constitutes a peculiar dialogical community. Be that as it may, for agents of knowledge, non-engagement with this dialogical community can still be an option. As an example, ‘the French and Italian IR communities are more insular in their orientation … and as such French and Italian IR scholars tend not to publish in the discipline’s international journals as much as Nordic or German IR scholars for example’ (Turton Citation2016, 16). However, the fact that the French and Italian IR communities are still located within the core, and accordingly assume a certain measure of recognition, needs to be taken into consideration in accounting for their relative self-isolation. Peripheral scholarship would not have such freedom of inaction if it aspires to achieve recognition and validation.

Still, it is not posited here that dialogue with the core is unequivocally embraced by scholars in the periphery. Many peripheral academics would insist that dialogue with the core scholarship is neither necessary nor desirable, and adopt a strategy of what Tickner calls ‘delinking’, which is ‘distinguishable primarily by the fact that it stakes out a position of difference outside of or in opposition to core IR, and is unconcerned with passing as “real” IR’ (Tickner Citation2013, 640). Even so, the question here is not whether categorical insularity and complete detachment from the core is desirable for the peripheral IR scholarship but whether it is possible.

For individual academics in the periphery, disengagement from a dialogue with the core could be conceivable and preferable. However, in the discipline of IR, exposure to knowledge flows originating in the core is unavoidable. Being an IR scholar today, whether in the core or in the periphery, means having been exposed to the ideas cultivated in the core, at the very least during the process of becoming a scholar. Accordingly, for a peripheral IR scholar, renouncing a dialogue with the core through detachment and insularity, however impractical, represents a choice. And yet, this choice would only position the peripheral scholar on the receiving end of the core’s monologue. Collective dialogic disengagement from the core is not a disciplinary possibility for the periphery either – all the more so because there are, and there always will be, individual IR scholars or communities of IR scholars in the periphery engaging in organisational, institutional, pedagogical and textual relationships with the core scholarship. In the discipline of IR, dialogue between the core and the periphery is a present reality and a future certainty.

On the other hand, scholars have propounded different conceptualisations of dialogue that take place in the discipline. In a succinct review, for instance, ‘a typology of four ideal-typical models of academic dialogue’ is presented in terms of purpose, procedure and product, which are the hierarchical model of dialogue, the reflexive model of dialogue, the transformative model of dialogue, and the eristic model of dialogue (Valbjørn Citation2017, 292). In another study, after reviewing the Socratic, Habermasian and Weberian conceptions of dialogue, Eun and Pieczara (Citation2013, 137) introduce an ‘instrumentalist’ approach in which dialogue is to ‘be understood and practiced as a reciprocal exchange of perspectives for mutual learning’ between the core and the periphery. Yong-Soo (Citation2019, 139) believes that ‘this “instrumentalist” approach to existing IR theories … can motivate Western IR scholars to listen more carefully to non-Western voices, which can in turn open up possibilities for dialogue between Western and non-Western IR scholars’.

In another study, three ways of stimulating dialogue by the peripheral scholars are presented. Mimicry, hybridity and denationalisation of ideas, it is proposed, ‘are tactics that could be adopted by peripheral scholars in order to elicit conversation and exchange of ideas [with the core]’ (Turton and Freire Citation2016, 538). In reference to hybridity, as an example, it is claimed that ‘producing hybrid research can be seen as a means of engaging with the perceived dominant “other” in order to gain detection, acceptance and, possibly, entrance into the “big conversation”’ (Turton and Freire Citation2016, 549). Another recent study presents ‘a typology of seven sets of practices, which are adopted by scholars as they engage with dominant knowledge production practices in IR’ (Loke and Owen Citation2022, 31). In addition, there are calls for transcending core–periphery classification ‘as a way of characterising the participants in dialogic exchange oriented towards the expansive transformation of disciplinary imaginaries’ (Hutchings Citation2011, 640).

It is contended here that there are two essential forms of dialogue in the discipline. These are dialogue of choice and dialogue of necessity. While dialogue is mostly a matter of choice for the core scholarship, it is mostly a matter of necessity for the peripheral scholarship. For the core, tangible and intangible benefits that are relinquished by not engaging the periphery are non-existent or negligible. Publishing in peripheral journals or doing post-doctoral research at peripheral universities constitute optional choices for core scholars in general since, first and foremost, it is not conceived as recognition of their scholarship. On the other hand, for the periphery, tangible and intangible benefits that are accrued by engaging the core are real and consequential. The paramount benefit chased and cherished, to emphasise, is the recognition and validation of peripheral scholars and their scholarship.

To repeat, for the core scholarship, dialogue is mostly a matter of choice while for the peripheral scholarship, dialogue is mostly a matter of necessity. This difference is caused by the differential epistemic gravities between the core and the periphery. Amplifying the epistemic gravity of the periphery is imperative to stimulate ‘veritable’ dialogue between the core and the periphery. Dialogue is a matter of power, and a transformation from unidirectional peripheral dialogue to a bidirectional global dialogue requires an increase in the periphery’s own power of appeal, which is the foundation of its epistemic gravity. And one promising avenue of amplifying the periphery’s power of appeal and its epistemic gravity is to foster its thematic density.

Thematic density of the periphery in global IR

What is required in the discipline, therefore, is epistemic revisionism; a transition from epistemic unipolarity to epistemic multipolarity (Peters and Wemheuer-Vogelaar Citation2016). The critical question here is to transform dialogue with the periphery from a matter of choice into a matter of necessity for the core. Situated at a higher stratum of epistemic hierarchy, the core is characterised by an entrenched propensity to conceive dialogue with the periphery as a matter of choice, a matter of intellectual experimentation, a matter of academic curiosity, a matter of disciplinary magnanimity. In order to transform dialogue with the periphery from a matter of choice to a matter of necessity for the core, asymmetries in the production, dissemination and consumption of knowledge in global IR need to be revised and rectified.

Of fundamental importance here is the realisation that the remedial measures for the rectification of asymmetrical knowledge flows lie first and foremost within the periphery itself. There exist, for example, peripheral critiques against the perceived parochialism of publishing practices in scholarly journals produced in the core, and accompanying appeals for greater inclusivity and diversity to transcend the prohibitive insularity. Judicious as it may be, this approach is certain to protract the current subordination of the periphery through supposedly correcting the faults of the core, and inadvertently creating the impression that the practices of the core are to become more proper and befitting for a global IR. Nevertheless, instead of aspiring to the consummation of the core, it would be more remedial to strive for the cultivation of the periphery.

As a matter of fact, the emergence of non/post-Western theory as a research programme in the discipline originates in the recognition of the exigency of rehabilitating the periphery.Footnote4 Since the inception of the discipline, ‘peoples of rich diversity in their historical and contemporary practices in IR are generally relegated to secondary, and even subordinate, analytical categories, such as “the periphery,” in relation to “the West”’ (Ersoy Citation2018, 204). Accordingly, ‘the majority of the world, called “the non-West,” who are constitutive of the reality that is called IR are not interpretative of that reality, and are only deemed illustrative for Western theory’ (Ersoy Citation2018, 204). Today, research on the epistemic marginalisation of the periphery in the discipline, and the ways to address and redress it, constitute the scholarly impetus stimulating a worldwide interest in, preoccupation with, and commitment to peripheral theorisation (Shahi Citation2019; Zhang Citation2020; Cooke Citation2022; Bakir and Ersoy Citation2022).

Theorisation in the periphery by the periphery seems to entertain virtually universal endorsement in the discipline and is regarded as the foremost auspicious course of surmounting the structural impoverishment of the periphery. Peripheral theorisation, accordingly, is expected to culminate in the emergence of more symmetrical flows in the production, dissemination and consumption of knowledge between the core and the periphery. Eventually, the prevailing epistemic hierarchy characterised by a vertical division of labour is to be superseded by an epistemic heterarchy characterised by a horizontal participation of labour between the core and the periphery. A true dialogue is to ensue in a truly global discipline.

This course of augmenting the epistemic gravity of the periphery – that is, peripheral theorisation – is not without potential deficiencies leading to unintended consequences. For example, discussing the prospects of indigenous theorisation in Asia, one scholar contends that

most intellectual endeavors to construct non-Western IRT [international relations theory] in Asia run the risk of inviting nativism – the mirror image of universalism – which do not involve a critical self-reflection and questioning of the a priori assumptions, procedures and values embedded in the modernization and development enterprise. (Chen Citation2011, 16)

By the same token, another scholar asserts, ‘uncovering the culturally specific character of particular ways of understanding the world … can also lead to a cultural and regional inwardness that may work to reproduce the very ethnocentricities that are being challenged’ (Hurrell Citation2016, 150; also see Viramontes Citation2022).

In yet another example, Xuetong (Citation2019), considered the leading figure in the so-called Tsinghua approach in Chinese IR (Zhang Citation2012), propounds what he calls a theory of moral realism. Moral realism is a theoretical undertaking to advance the realist theory by virtue of drawing on indigenous Chinese thought and experience, in both historical and contemporary forms. Accordingly, Xuetong’s study is expected to intensely engage, at least critically, the extant realist literature. However, the bibliography registers just one entry for Kenneth Waltz, another entry (a commentary) for Stephen M. Walt, and two entries for John J. Mearsheimer, who are the leading figures in realist scholarship. The propensity to exercise a dismissive attitude towards established canons of scholarship, albeit Western in origin, is bound to subvert rather than support peripheral theorisation. In global IR, originality emanating from seclusive and insular indigeneity would be tantamount to disciplinary marginality.

Another proposed course of augmenting the epistemic gravity of the periphery pertains to methodology. Scholars in the periphery, it is urged, ‘must undergo critical self-reflection to try and overcome the many quality problems that do exist. They must work to combat methodological poverty in the periphery’ (Aydınlı and Biltekin Citation2018b, 233). In this view, methodological proficiency rather than theoretical ingenuity needs to take precedence for the periphery to attain epistemic gravity. Aydinli (Citation2020, 291), for instance, is of the opinion that

absent a revolution focused on methodological quality, any proposals as regards theorising and goals which address the production problem by developing either local disciplinary communities or the broader IR discipline through direct promotion of theorising in the periphery may be untenable.

In addition to theoretical ingenuity and methodological proficiency, a third course for augmenting the epistemic gravity of the periphery can be advanced, which is called here thematisation. Thematisation simply refers to specialisation in particular fields of substantive research represented by research programmes in the periphery primarily cultivated and sustained by local epistemic communities. It is not suggested, though, that peripheral scholarship concentrate primarily on peculiar niche areas of expertise in global IR. Neither is it suggested that the expected outcome from thematisation is to supplant the core in particular fields of substantive research. Rather, the expected outcome is the emergence of alternative sites of substantive research in the periphery even in the common areas of expertise. Still, thematisation would not serve the augmentation of the epistemic gravity of the periphery. What is required, therefore, is thematic density. Thematic density refers to focussed specialisation in particular fields of substantive research. Hypothetically, two cases can be compared to clarify the significance of thematic density for peripheral scholarship. In the first case, 10 scholars from a peripheral academia publish one article each on 10 different fields of research. In the second case, 10 scholars from the same peripheral academia publish one article each on the same field, or similar fields, of research. The first case represents a peripheral research community lacking a collective research programme. The second case represents a peripheral research community that collectively sustains a focussed research programme. Even though the scholarly output remains the same in both cases (10 articles in total), the academic weight, impact and appeal of the second case in all likelihood surpasses those of the first case in the discipline. In brief, thematic density in the periphery constitutes an alternative course of augmenting the epistemic gravity of the periphery. This is expected to make dialogue with the periphery a matter of necessity for the core.

Epistemic hierarchies predicate upon the movement of ideas as well as the movement of people in global IR. Not just the asymmetrical flows of knowledge but also the asymmetrical movement of scholars forge the contemporary hierarchical structure of the discipline. Therefore, for a more symmetrical disciplinary dialogue, the volume of knowledge originating in the periphery and flowing towards the core needs to be intensified, accompanied by a concomitant intensification of the movement of academics from the core to the periphery. The augmentation of the periphery’s thematic density serves both of these disciplinary objectives. It is expected to increase the flow of knowledge from the periphery to the core, and to attract more academics from the core to the periphery.

The ultimate outcome expected from an increase in the thematic density of the periphery is to render it impossible to disregard, to discount, to silence or to marginalise the peripheral scholarship. To paraphrase, the ultimate outcome is to render epistemic engagement with the periphery an essential and inescapable dimension of scholarship for the core – that is, to render dialogue a matter of necessity for the core. Accordingly, given that the core’s power of appeal is balanced with the periphery’s power of appeal, dialogue with the other side becomes a necessity for both sides, resulting in a non-hierarchical dialogue between the core and the periphery and a more symmetrical distribution of ‘power, privilege, and place in the global knowledge chain’ (Tickner Citation2013, 642).

Epistemic gravity of the core and its dialogic implications: the case of Turkish IR academia

As a case study, the dynamics of the differential epistemic gravities of the core and the periphery in the discipline are discussed here in terms of the positionality of Turkish IR academia within the global IR. The positionality of Turkish IR academia is analysed by reference to the spatiality of academic institutions from which IR scholars in Turkey have received their PhDs. In addition, dialogic implications of the global/local distribution of the universities from which IR scholars in Turkey have received their doctoral degrees are discussed.

The discipline of IR has a relatively established pedigree in the Turkish academia. The intellectual genesis of the discipline predates the establishment of the Turkish Republic and has its origins in the higher education institutions of the late Ottoman Empire (Özcan Citation2020). Nonetheless, the inception of a robust institutionalisation of the discipline came only in the aftermath of the Second World War. After a long period of steady existence, the evolution of the discipline has gained a good deal of momentum since the end of the Cold War. Today, the progress of the Turkish IR academia is characterised by an ongoing struggle for disciplinary ‘maturity’ (Turan Citation2018; Aydınlı and Biltekin Citation2017; Kostem and Sen Citation2020). The current state of the Turkish IR academia displays the symptoms of a discipline situated in the periphery of the global IR discipline and beset by the institutional, pedagogical and intellectual complications of the prevalent epistemic hierarchy (Ongur and Gürbüz Citation2019). The exposure of the Turkish IR discipline to the asymmetrical knowledge flows in the contemporary global IR is periodically investigated by Turkish scholars, which conveys an elevated sense of disciplinary self-awareness and self-reflexivity (Balci et al. Citation2019; Aydın and Dizdaroğlu Citation2019).

There is a multitude of indicators by which to ascertain the power of appeal of the core, such as the significance accorded in peripheral epistemic communities to publishing in core journals. In a similar vein, one of the avenues for assessing the epistemic gravity entertained by the core and experienced by the periphery is to identify the patterns of academic mobility between the core and the periphery. A consequential exemplar of academic mobility in global IR is the location of universities from which IR scholars receive their doctoral degrees.

A spatial analysis of the preferences of periphery scholars for the pursuit of PhD degrees provides an indicator for the existence and the extent of the core’s epistemic gravity. The institutional location of PhD degrees pursued by peripheral scholars bears additional significance for the epistemic hierarchy and associated asymmetries in global IR. For example, academic experiences and professional relations of peripheral scholars, or lack thereof, during the PhD period condition the interaction patterns later in their academic lives. Thus, the sites of higher education that peripheral scholars interact with have the capacity to reproduce the relational patterns between the core and the periphery, and thereby to sustain the status quo in global IR.

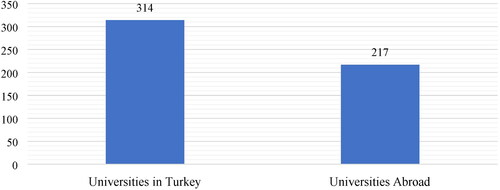

In order to ascertain the extent of the core’s epistemic gravity for the Turkish IR academia, a study is conducted for a spatial analysis of the universities from which IR scholars in Turkey have received their doctoral degrees.Footnote5 A sampling is made for the analysis. Only the scholars employed at universities with departments that confer PhD degrees in IR are selected.Footnote6 There are 50 universities in Turkey that confer PhD degrees in IR. In total, there are 532 IR scholars employed at these 50 universities ().Footnote7

Figure 2. Locality of universities from which international relations scholars in Turkey have received their PhD degrees.

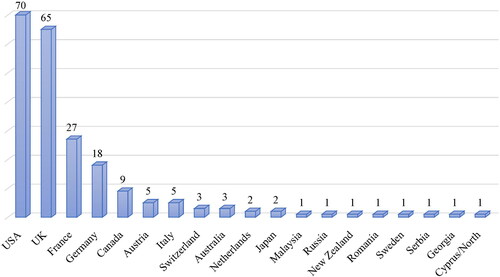

Among these, 314 (59%) IR scholars have received their PhD degrees from Turkish universities. On the other hand, 217 (41%) IR scholars have received their PhDs from universities abroad. These figures show that Turkish IR academia enjoys a relatively high level of international mobility. Nonetheless, once the figures are further disaggregated, a manifest imbalance in international mobility is observed ().

Figure 3. Country-specific locations of universities abroad from which Turkish international relations scholars have received their PhD degrees.

Among the countries IR scholars in Turkey have received their PhD degrees from, the US occupies the leading position, closely followed by the UK. In addition, France, Germany and Canada are also preferred sites of higher education for IR scholars in Turkey. In general, 208 IR scholars (96%) in the sampled Turkish universities received their PhDs from universities located in the West while only nine IR scholars (4%) received their PhDs from universities outside the West. Here, the West is a geographical denomination representing only Europe and North America, and thus excludes Australia and New Zealand as well as Russia and Georgia. If the West is taken in a civilisational sense, the figures become even more strikingly disproportionate. Among the West, Europe is the more favoured destination of higher education for IR scholars in Turkey: 128 scholars received their PhDs from universities in Europe while 79 scholars obtained theirs from universities in North America. In Europe, the UK is the leading destination, with 65 scholars receiving their PhD degrees from UK universities.

Moreover, absences are equally telling concerning the location of universities abroad from which IR scholars in Turkey have received their PhDs. Among Asian countries, for instance, only three IR scholars have received their PhD degrees from Australia, two from Japan, one from Malaysia, and one from New Zealand. Not a single scholar with a PhD from universities in China or India is employed at the Turkish universities that are sampled here. Likewise, the Middle East, Africa and Latin America are all absent in the overall academic scene. For the Turkish IR academia, the epistemic gravity of the core represented by the West appears to be overwhelming, even hegemonic.Footnote8

The epistemic gravity of the core manifests itself in the spatial distribution of universities from which IR scholars in Turkey have received their PhDs. This disciplinary state of affairs carries dialogic implications for the state of the discipline in Turkey. The origins of PhD degrees are intimately associated with the research practices and publishing tendencies of scholars insofar as doctoral training functions ‘as a mechanism of academic socialization’ (Lohaus, Wemheuer-Vogelaar, and Ding Citation2021, 3). Hence, the location of doctoral degree studies wherein they were socialised as scholars conditions the dialogic orientations of Turkish academics as well.

With regard to the thematic density in the Turkish IR discipline, two sociological divisions emanating from the global/local distribution of the origins of PhDs need to be taken into consideration. First, there emerges a stratification in the local academia between those academics who have doctoral degrees from ‘overseas’ and those academics who obtained their degrees from Turkish universities. This division informs the configuration of social networks and research clusters in the Turkish IR academia, in which academics with doctoral degrees from ‘overseas’ entertain varied privileges. For one example, similar to other peripheral contexts, ‘authors [read: scholars] holding PhDs from “core” regions have markedly more freedom of choice, indeed can publish anywhere, while authors [read: scholars] with PhDs from “periphery” regions can only publish in “periphery” journals’ barring individual exceptions (Wemheuer-Vogelaar Citation2022, 12). In a similar vein, as an informal rule, being ‘with an overseas PhD’, using the Turkish parlance, is a required qualification for departmental hiring practices at many universities in Turkey, including IR departments. The second division involves those academics who are socialised into the disciplinary practices during their doctoral education in Northern America, especially the US, and those academics who have received their PhDs from European universities.

These sociological divisions add to the many divisions afflicting the Turkish IR community and militate against the augmentation of thematic density in the local academia. Since Turkish scholars will continue to pursue doctoral education abroad, primarily in the core, these divisions are expected to persist. Therefore, what is needed is the cultivation of focussed research programmes in particular fields of the discipline that are self-consciously sustained by the Turkish IR community with viable and sustainable institutional, organisational, pedagogical and financial commitments. This approach also has the potential to bridge the divisions mentioned above.

Conclusion

Despite the increasingly vocal appeals in the discipline for a more sustained and empathetic dialogue between the disciplinary core and the periphery, the imperative question remains how to ensure the emergence of a true dialogue between these two sides in a truly global discipline. In the current conditions of epistemic hierarchy and asymmetrical dialogue, to recapitulate, dialogue is mostly a matter of choice for the core while it is mostly a matter of necessity for the periphery. Dialogue is mostly a matter of necessity for the periphery inasmuch as dialogue with the core is expected, above all, to confer recognition and validation for the peripheral scholar and their scholarship. To rectify the abiding disciplinary asymmetry, dialogue with the periphery needs to become a matter of necessity for the core instead of a matter of choice. To that end, the epistemic gravity of the periphery and its own power of appeal need to be augmented. One promising avenue for increasing the epistemic gravity of the periphery is to foster its thematic density. That is, focussed specialisation in particular fields of substantive research represented by research programmes that are primarily cultivated and sustained by local epistemic communities in the periphery appears to be imperative for a truly ‘global’ IR.

As an answer to a question in scientific research usually begets further questions, ways of fostering the thematic density of the periphery call for further scrutiny. Local IR academia in the periphery seems to be afflicted with an absence of focussed specialisation characterised by established institutions, committed researchers and sustainable financial resources. Individual academics in peripheral IR academia conducting exceptional research on particular issues abound. And yet, collective specialisation in certain research programmes crucial for viable thematic density is wanting. There are mainly two sets of causes impeding the fostering of thematic density in the periphery. One set concerns exogenous factors, such as the research opportunities presented by the core. The other set concerns endogenous factors, such as the violation, or the prospects of violation, of individual rights and academic liberties within the periphery.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks Deniz Kuru, Ali Murat Kurşun, and two anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments on the earlier drafts of this paper. The author also thanks Cansu Yetimoğlu Sağlam for their assistance in data collection.

Disclosure statement

The author declares there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Eyüp Ersoy

Eyüp Ersoy is a visiting research fellow in the Institute of Middle Eastern Studies at King’s College London. He is also a visiting lecturer in the Department of Political Science and International Studies at the University of Birmingham. He received his PhD from the Department of International Relations at Bilkent University. He previously worked as a senior research fellow at the Center for Foreign Policy and Peace Research (CFPPR). His research interests include power and influence in IR, home-grown theorising in global IR, and knowledge production in Turkish academia about the Middle East.

Notes

1 In this article, a peripheral scholar is defined as a scholar who has citizenship in a country located in the periphery, and whose primary institutional affiliation is with an institution of higher education in a country located in the periphery.

2 This sentence is a reformulation of the opening sentence of a recent book, which reads: ‘As gravity bends light, so power bends time’ (Clark Citation2019, 1).

3 This state of affairs is not confined to IR, or to the social sciences for that matter. See Kilina (Citation2021).

4 On research programs in the theoretical progress of the discipline from a Lakatosian perspective, see Elman and Elman (Citation2003).

5 The project was conducted by the author in 2020 in the Center for Foreign Policy and Peace Research (CFPPR) located in Ankara, Turkey. See http://www.foreignpolicyandpeace.org/index.php/en/homepage/.

6 There are two classes of departments conferring PhD degrees in international relations in Turkey: departments of international relations, and departments of political science and international relations.

7 These figures include scholars of Turkish nationality as well as of non-Turkish nationality.

8 There are a variety of reasons for this asymmetrical state of affairs in the Turkish IR academia. Still, a discussion of these reasons is beyond the scope of this article, and calls for further research.

Bibliography

- Acharya, A. 2011. “Dialogue and Discovery: In Search of International Relations Theories beyond the West.” Millennium: Journal of International Studies 39 (3): 619–637. doi:10.1177/0305829811406574

- Acharya, A. 2016. “Advancing Global IR: Challenges, Contentions, and Contributions.” International Studies Review 18 (1): 4–15. doi:10.1093/isr/viv016

- Acharya, A., and B. Buzan. 2017. “Why Is There No Non-Western International Relations Theory? Ten Years on.” International Relations of the Asia-Pacific 17 (3): 341–370. doi:10.1093/irap/lcx006

- Aydın, M., and C. Dizdaroğlu. 2019. “Türkiye’de Uluslararası İlişkiler: TRIP 2018 Sonuçları Üzerine Bir Değerlendirme [International Relations in Turkey: An Evaluation on the Findings of TRIP 2018].” Uluslararası İlişkiler Dergisi 16 (64): 3–28. doi:10.33458/uidergisi.652877

- Aydinli, E. 2020. “Methodology as a Lingua Franca in International Relations: Peripheral Self-Reflections on Dialogue with the Core.” The Chinese Journal of International Politics 13 (2): 287–312. doi:10.1093/cjip/poaa003

- Aydınlı, E., and G. Biltekin. 2017. “Time to Quantify Turkey’s Foreign Affairs: Setting Quality Standards for a Maturing International Relations Discipline.” International Studies Perspectives 18 (3): 267–287. doi:10.1093/isp/ekv009

- Aydınlı, E., and G. Biltekin. 2018a. “Introduction: Widening the World of IR.” In Widening the World of International Relations: Homegrown Theorizing, edited by E. Aydınlı and G. Biltekin, 1–12. Oxon: Routledge.

- Aydınlı, E., and G. Biltekin. 2018b. “Conclusion: Toward a Global Discipline.” In Widening the World of International Relations: Homegrown Theorizing, edited by E. Aydınlı and G. Biltekin, 226–233. Oxon: Routledge.

- Aydınlı, E., and J. Mathews. 2000. “Are the Core and Periphery Irreconcilable? The Curious World of Publishing in Contemporary International Relations.” International Studies Perspectives 1 (3): 289–303. doi:10.1111/1528-3577.00028

- Aydınlı, E., and J. Mathews. 2008. “Periphery Theorising for a Truly Internationalized Discipline: Spinning IR Theory out of Anatolia.” Review of International Studies 34 (4): 693–712. doi:10.1017/S0260210508008231

- Bakir, A., and E. Ersoy. 2022. “The Rise and Fall of Homegrown Concepts in Global IR: The Anatomy of ‘Strategic Depth’ in Turkish IR.” All Azimuth 11 (2): 257–273. doi:10.20991/allazimuth.1150360

- Balci, A., F. Cicioğlu, and D. Kalkan. 2019. “Türkiye’deki Uluslararası İlişkiler Akademisyenleri ve Bölümlerinin Akademik Etkilerinin Google Scholar Verilerinden Hareketle İncelenmesi [a Study for Scholarly Impacts of International Relations Academics and Departments in Turkey through Google Scholar Data].” Uluslararası İlişkiler Dergisi 16 (64): 57–75. doi:10.33458/uidergisi.652913

- Bode, I., and H. Huelss. 2018. “Autonomous Weapons Systems and Changing Norms in International Relations.” Review of International Studies 44 (3): 393–413. doi:10.1017/S0260210517000614

- Carrozza, I., and L. Benabdallah. 2022. “South-South Knowledge Production and Hegemony: Searching for Africa in Chinese Theories of IR.” International Studies Review 24 (1): 1–21. doi:10.1093/isr/viab063

- Chen, C. 2011. “The Absence of Non-Western IR Theory in Asia Reconsidered.” International Relations of the Asia-Pacific 11 (1): 1–23. doi:10.1093/irap/lcq014

- Clark, C. 2019. Time and Power: Visions of History in German Politics, from the Thirty Years’ War to the Third Reich. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Cooke, S., ed. 2022. Non-Western Global Theories of International Relations. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Cotton, J. 2009. “Realism, Rationalism, Race: On the Early International Relations Discipline in Australia.” International Studies Quarterly 53 (3): 627–647. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2478.2009.00549.x

- Elman, C., and M. F. Elman. 2003. Progress in International Relations Theory: Appraising the Field. London: MIT Press.

- Ersoy, E. 2018. “Conceptual Cultivation and Homegrown Theorizing: The Case of/for the Concept of Influence.” In Widening the World of International Relations: Homegrown Theorizing, edited by E. Aydınlı and G. Biltekin, 204–225. Oxon: Routledge.

- Eun, Y.-S., and K. Pieczara. 2013. “Getting Asia Right and Advancing the Field of IR.” Political Studies Review 11 (3): 369–377. doi:10.1111/j.1478-9302.2012.00290.x

- Garcia, D. 2018. “Lethal Artificial Intelligence and Change: The Future of International Peace and Security.” International Studies Review 20 (2): 334–341. doi:10.1093/isr/viy029

- Hoijtink, M., and M. Leese, eds. 2019. Technology and Agency in International Relations. Oxon: Routledge.

- Hurrell, A. 2016. “Beyond Critique: How to Study Global IR?” International Studies Review 18 (1): 149–151. doi:10.1093/isr/viv022

- Hutchings, K. 2011. “Dialogue between Whom? The Role of the West/Non-West Distinction in Promoting Global Dialogue in IR.” Millennium: Journal of International Studies 39 (3): 639–647. doi:10.1177/0305829811401941

- Kilina, Y. 2021. “It’s Not Science, If It’s Not European.” Ukrant. https://www.ukrant.nl/magazine/its-not-science-if-its-not-european/?lang=en

- Kristensen, P. M. 2015a. “International Relations in China and Europe: The Case for Interregional Dialogue in a Hegemonic Discipline.” The Pacific Review 28 (2): 161–187. doi:10.1080/09512748.2014.948568

- Kristensen, P. M. 2015b. “Revisiting the ‘American Social Science’ – Mapping the Geography of International Relations.” International Studies Perspectives 16 (3): 246–269. doi:10.1111/insp.12061

- Kristensen, P. M. 2015c. “How Can Emerging Powers Speak: On Theorists, Native Informants and Quasi-Officials in International Relations Discourse.” Third World Quarterly 36 (4): 637–653. doi:10.1080/01436597.2015.1023288

- Kristensen, P. M. 2019. “Southern Sensibilities: Advancing Third Wave Sociology of International Relations in the Case of Brazil.” Journal of International Relations and Development 22 (2): 468–494. doi:10.1057/s41268-017-0107-z

- Kostem, S., and O. F. Sen. 2020. “International Political Economy in Turkey: The Evolution and Current State of a Maturing Subfield.” Uluslararası İlişkiler 17 (66): 77–91. doi:10.33458/uidergisi.720626

- Lohaus, M., W. Wemheuer-Vogelaar, and O. Ding. 2021. “Bifurcated Core, Diverse Scholarship: IR Research in Seventeen Journals around the World.” Global Studies Quarterly 1 (4): 1–16. doi:10.1093/isagsq/ksab033

- Loke, B., and C. Owen. 2022. “Mapping Practices and Spatiality in IR Knowledge Production: From Detachment to Emancipation.” European Journal of International Relations 28 (1): 30–57. doi:10.1177/13540661211062798

- Maliniak, D., S. Peterson, R. Powers, and M. J. Tierney. 2018. “Is International Relations a Global Discipline? Hegemony, Insularity, and Diversity in the Field.” Security Studies 27 (3): 448–484. doi:10.1080/09636412.2017.1416824

- Moshirzadeh, H. 2018. “Iranian Scholars and Theorizing International Relations: Achievements and Challenges.” In Widening the World of International Relations: Homegrown Theorizing, edited by E. Aydınlı and G. Biltekin, 83–103. Oxon: Routledge.

- Niang, A. 2016. “The Imperative of African Perspectives on International Relations (IR).” Politics 36 (4): 453–466. doi:10.1177/0263395716637092

- Odoom, I., and N. Andrews. 2017. “What/Who Is Still Missing in International Relationship Scholarship? Situating Africa as an Agent in IR Theorising.” Third World Quarterly 38 (1): 42–60. doi:10.1080/01436597.2016.1153416

- Ongur, H. Ö., and S. E. Gürbüz. 2019. “Türkiye’de Uluslararası İlişkiler Eğitimi ve Oryantalizm: Disipline Eleştirel Pedagojik Bir Bakış [The Education of International Relations in Turkey and Orientalism: A Critical Pedagogical Approach to the Discipline].” Uluslararası İlişkiler Dergisi 16 (61): 23–38. doi:10.33458/uidergisi.541517

- Opello, W. C., and S. J. Rostow. 1999. The Nation-State and Global Order: A Historical Introduction to Contemporary Politics. Boulder: Lynne Rienner.

- Özcan, G. 2020. “Siyasiyat’tan ‘Milletlerararası Münasebetler’e: Türkiye’de Uluslararası İlişkiler Disiplininin Kavramsal Tarihi [From Politics to International Relations: A Conceptual History of the International Relations Discipline in Turkey].” Uluslararası İlişkiler 17 (66): 3–21. doi:10.33458/uidergisi.720619

- Peters, I., and W. Wemheuer-Vogelaar, eds. 2016. Globalizing International Relations: Scholarship Amidst Divides and Diversity. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Risse, T., W. Wemheuer-Vogelaar, and F. Havemann. 2022. “IR Theory and the Core-Periphery Structure of Global IR: Lessons from Citation Analysis.” International Studies Review 24 (3): 1–38. doi:10.1093/isr/viac029

- Rupert, M. 2009. “Antonio Gramsci.” In Critical Theorists and International Relations, edited by J. Edkins and N. Vaughan-Williams, 176–186. Oxon: Routledge.

- Sajed, A. 2020. “From the Third World to the Global South.” E-International Relations. https://www.e-ir.info/2020/07/27/from-the-third-world-to-the-global-south/

- Shahi, D. 2019. Advaita as a Global International Relations Theory. Oxon: Routledge.

- Taylor, L. 2012. “Decolonizing International Relations: Perspectives from Latin America.” International Studies Review 14 (3): 386–400. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2486.2012.01125.x

- Tickner, A. B. 2013. “Core, Periphery and (Neo)Imperialist International Relations.” European Journal of International Relations 19 (3): 627–646. doi:10.1177/1354066113494323

- Turan, İ. 2018. “Progress in Turkish International Relations.” All Azimuth 7 (1): 137–142. doi:10.20991/allazimuth.328455

- Turton, H. L. 2016. International Relations and American Dominance: A Diverse Discipline. Oxon: Routledge.

- Turton, H. L., and L. G. Freire. 2016. “Peripheral Possibilities: Revealing Originality and Encouraging Dialogue through a Reconsideration of ‘Marginal’ IR Scholarship.” Journal of International Relations and Development 19 (4): 534–557. doi:10.1057/jird.2014.24

- Valbjørn, M. 2017. “Dialoguing about Dialogues: On the Purpose, Procedure and Product of Dialogues in Inter-National Relations Theory.” International Studies Review 19 (2): 279–309. doi:10.1093/isr/vix009

- Viramontes, E. 2022. “Questioning the Quest for Pluralism: How Decolonial Is Non-Western IR?” Alternatives: Global, Local, Political 47 (1): 45–63. doi:10.1177/03043754211064545

- Wemheuer-Vogelaar, W. 2022. “The Global Division of Labor in a Not So Global Discipline.” All Azimuth 11 (1): 3–27. doi:10.20991/allazimuth.1034358

- Xuetong, Y. 2019. Leadership and the Rise of Great Powers. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Yong-Soo, E. 2019. “Global IR through Dialogue.” The Pacific Review 32 (2): 131–149. doi:10.1080/09512748.2018.1461680

- Zhang, F. 2012. “The Tsinghua Approach and the Inception of Chinese Theories of International Relations.” The Chinese Journal of International Politics 5 (1): 73–102. doi:10.1093/cjip/por015

- Zhang, Y. 2020. “The Chinese School, Global Production of Knowledge, and Contentious Politics in the Disciplinary IR.” All Azimuth 9 (2): 283–298. doi:10.20991/allazimuth.725252