Abstract

Pesticides are becoming a key topic in critical academic research; they entail substantial negative global impacts on human health and other-than-humans’ existences. Even though decades of agroecological research and practice have demonstrated that no pesticides are needed to produce enough food, pesticides are still most typically taken for granted as an indispensable part of food production. In this article, we analyse events and policies through which Brazilian agriculture has become a global hotspot for pesticide consumption in the global agrarian capitalism. We provide an overview of the pesticide legalisation in Brazilian agriculture and discuss the ramifications of recent changes for pesticide-free agriculture. The post-2016 legalisation of pesticides has taken place concomitantly with a quick dismantling of the structures supporting agroecology and protecting the environment. The toxic turn of the Brazilian agriculture is seen in part as a reactionary response to the momentum of agroecology, which removes pesticides from agriculture, that had gained strength under the first Workers’ Party regime between 2003 and 2016. A pivotal policy goal for the new Lula government should be an agroecological transformation, which can be justified by politicising pesticide use as a major, multidimensional problem of the ‘agribusiness economy’.

Introduction

Pesticides entail substantial and increasing negative global impacts on humans’ health and other-than-humans’ existences (Pisa et al. Citation2021). They are becoming a key topic in critical academic research, including the social sciences (Clapp Citation2021; Shattuck Citation2021; Zaller Citation2022). Most typically pesticides are taken as granted as an indispensable part of food production, but decades of agroecological and agroforestry research have demonstrated that no pesticides are needed to produce enough food (Altieri Citation1989; IAASTD Citation2009; Ollinaho and Kröger Citation2021; Tomich et al. Citation2011). Instead, pesticides ought to be seen as critical ‘not for producing enough food to feed the population, but for the survival of a particular form of political economy’ (Shattuck Citation2021, 3), in which feed–meat production complexes, waste and unequal food distribution structurally support the pesticide regimes. It should be evident that a transition towards pesticide-free agriculture would be a long process and tantamount to revolutionalising not only rural realities (Altieri Citation1989) but also entire societies. The dependency on pesticides belongs to the particular mode of food production – that is, chemical input-intensive large-scale single-crop agriculture – that has been forcefully imposed as part of the green revolution and modernisation. The US as the world hegemon started to impose agricultural ‘modernisation’ elsewhere around the globe, making the rest of the world dependent on its input imports (Bauerly Citation2017). At the global level this model strengthens colonial relations between the Global North and the Global South, as the former provides value-added inputs to the latter that supplies raw materials to the former (Bombardi and Changoe Citation2022). Today, the global agricultural trade is very uneven, playing a pertinent part in the ongoing vast wealth extraction from the Global South to Global North (Hickel, Sullivan, and Zoomkawala Citation2021).

Global pesticide use has grown during the twenty-first century partly due to the proliferation of pesticide generics that pour from China, and to a lesser extent from India, to elsewhere in the Global South, especially to Brazil (Oliveira, He, and Ma Citation2020; Shattuck Citation2021; Werner, Berndt, and Mansfield Citation2022). For this article, we analysed events and policies through which Brazilian agriculture has become a global hotspot for pesticide consumption in the global agrarian capitalism. Part of the Latin American pink tide, the election of Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (Lula) at the end of 2002 as the Brazilian president launched the first Workers’ Party (PT)-led regime, which lasted from 2003 to 2016. We assessed the extent to which there was a toxic turn in the Brazilian agriculture since this regime ended with Dilma Rousseff’s impeachment in April 2016 and particularly since 2019 when Jair Bolsonaro started his far-right governance. We will discuss the ramifications of the major changes in political economy and pesticide regulation during this era and explore how, concomitantly with the promotion of chemical input-intensive agriculture, the institutional support for agroecology was dismantled. The role of the ultra-conservative faction behind these moves is scrutinised.

We analysed the toxic turn through critical agrarian studies, political economy and agroecology research, relating the findings to broader world-systemic analysis of the pesticides–agroecology schism in development policies. The research was based on policy analysis, using as material the numbers and types of pesticide approvals and concomitant policy and institutional changes in Brazil, with their international linkages. Below, we first provide an outline of what we call a toxic turn. We present a detailed analysis of the surge of approving new pesticides for the Brazilian markets in post-2016 Brazil, focusing on the Bolsonaro presidency. Second, we link these moves to the rise of China in the global commodity and pesticide markets. Third, we assess the authoritarian links of pesticide approval. We draw conclusions on the political economic situation in Brazil, and identify levers with the potential to curb the massive growth of pesticide use in Brazil and to transform the food system towards agroecological production.

Has there been a toxic turn in Brazil after 2016?

Brazil is among the world’s largest agricultural producers, and a major terrain in the contest between the various agricultural modes of production. Brazil has been one of the leading countries in promoting agroecology, ‘the application of ecological concepts and principles to the design and management of sustainable agricultural ecosystems’ (Altieri Citation2009, 103), which, however, ‘cannot be implemented without modifying the socio-economic determinants that govern what is produced, how it is produced, and for whom it is produced’ (Altieri Citation1989, 38). Brazil has a 40-year-old agroecology movement (Van den Berg et al. Citation2022) that gained momentum particularly during the two governments of Lula between 2003 and 2010, but also during the first term of Dilma Rousseff’s presidency (2011–2014). A series of policies supporting and aiming to scale out agroecological production were incubated in participatory policymaking arenas, councils of various types, where the voice of social movements and civil society was heard. However, even though the state support for family farming production increased more than 10-fold from 2003 to 2015, the main mechanism was subsidised agricultural credit to purchase inputs (Niederle et al. Citation2022), which does not help in agroecological production that approaches soil fertility and pest control without externally produced inputs. What is more, while the push towards agroecology was substantial, it remained an underdog in the ‘agribusiness economy’ that has been bolstered ever since 1999 when President Fernando Henrique Cardoso launched several key programmes supporting agribusiness exports (Sauer and Mészáros Citation2017). As part of the neo-extractivist development patterns (Andrade Citation2022), the PT governments subsequently retained and intensified these policies that helped the chemical input-intensive large-scale agriculture to grow rapidly along with other extractive sectors during the global commodity boom that still continues (Kröger Citation2022).

This PT-led regime ended with Dilma Rousseff’s impeachment in April 2016, which analysts have called a parliamentary coup (Braga and Purdy Citation2019). Immediately after the impeachment was concluded, the interim government of Michel Temer begun to dismantle policies of environmental protection and support for family farming and agroecology ‘by abolishing the Ministry of Agrarian Development and weakening the powers and finances of the National Institute of Colonization and Agrarian Reform (INCRA)’ (Sauer and Mészáros Citation2017, 406) and drastically reducing the budget for the Food Acquisition Program (PAA) (Niederle et al. Citation2022). With the far-right, science-hostile government of Jair Bolsonaro which started governing in January 2019, this process of dismantling policies around environmental protection and family farming was intensified and, concomitantly, chemical input-intensive agribusiness that threatens public health and environment was forcefully promoted (Menezes and Barbosa Citation2021; Milhorance Citation2022; Niederle et al. Citation2022).

One relevant point of pro-agribusiness support has been the approval and removal of restrictions on agrochemicals used in agriculture, an inherent part of the paradigm of industrial agriculture (Clapp Citation2021). When referring to pesticides here we also include herbicides, insecticides, fungicides and nematicides – that is, killing substances; the suffix ‘icide’ has the literal meaning ‘to kill’ (Bombardi Citation2019). The growth in pesticide use in Brazil has been breathtaking, starting from scratch; that is, from 16,000 tons in 1963 and increasing over 30-fold by 2020 (Burity Citation2020; Glaeser Citation2011). In both academic and public discourses, Brazil is often claimed to be the largest consumer of pesticides, but in fact Brazil is the second largest consumer and China is by far the largest, consuming nearly five times more pesticides than Brazil; and the US is the third largest (FAO Citation2019). However, Brazil is globally the biggest importer of pesticides, whereas China is the biggest exporter, these two tendencies being causally linked to each other (Oliveira, He, and Ma Citation2020). The global pesticide configuration has changed as part of the world systemic rise of China (McMichael Citation2020; Shattuck Citation2021). Without understanding the historically dependent political economic dynamics of regions with their world systemic relations, it is realistically impossible to conceive pesticide-free developments.

The PT did embrace pesticides, in particular, with President Dilma Rousseff under dire political pressure and with focus on short-term aims in their ‘path of least resistance’ (Loureiro and Saad-Filho Citation2019, 67). Dilma nominated Kátia Abreu, the ‘chainsaw queen’, then the head of the influential lobby group the Brazilian Confederation of Agriculture and Livestock (CNA), as the Minister of Agriculture in 2015 (Sauer and Mészáros Citation2017). However, after the coup in 2016, there was a substantial shift in pesticide regulation and the pace of releasing new pesticides to Brazilian markets tripled from its previous level. This shift in the pesticide market broke the news threshold frequently in the international media. To date, social scientific focus on this acceleration of pesticide approval in Brazil has been limited (cf. Oliveira, He, and Ma Citation2020). Due to this surge of pesticides, we claim that Brazil took a toxic turn in 2016.

The accelerated legalisation of pesticides is not an isolated process, but a political strategy developed with the national and international agribusiness lobby that holds the key power in Brazilian politics (Castilho et al. Citation2022). We have situated this removal of political, legal and administrative barriers to pesticide liberation within the existing and shifting power relations in Brazil and its international alignments. Along with the rise in pesticide legalisation, support for family farming was dismantled, starting with the dissolution of the Ministry of Agrarian Development in 2016 that had provided support for family farming since the 1990s (Niederle et al. Citation2022). This toxic turn in Brazil seems to have enlightened an opposite development direction: avenues for detoxing agriculture through alternative agricultural systems. Alternatives, which in Brazil have been gathered under the label ‘agroecology’, require contesting the chemically intensive industrial paradigm at various dimensions. Perhaps most pertinently, this means that the civil society is able to participate, embed and co-produce the state and its policymaking arenas (Kröger Citation2020), which agroecology had succeeded in doing to an important extent during the PT governments (Niederle et al. Citation2022). While the number and harmful quality of new pesticides that have been liberated is impressive, we have seen that at a deeper level, the power shifts through a wholesale attack on agroecology and its supporting state structures may be an even more dramatic sign of the toxicity of Brazilian agriculture.

Outlook of global and Brazilian pesticide use

In 2019, the global pesticide markets was valued at an estimated USD85 billion (ReportLinker Citation2021), of which China’s share was USD57 billion (Fernández Citation2021). Highly hazardous pesticides are estimated to cover about 40% of the market (Gaberell and Hoinkes Citation2019). Even though various highly hazardous pesticides have been banned in the Global North, they continue to be produced there and shipped to the Global South (FAO and WHO Citation2019) where 99% of the associated acute poisonings take place (Zaller Citation2022). The industry has consolidated to a remarkable extent in the last few decades (Clapp Citation2021; Werner, Berndt, and Mansfield Citation2022). In China, the consolidation began in the early 2010s and continues to do so under China’s five-year plans, with the Syngenta Group spearheading this development (Werner, Berndt, and Mansfield Citation2022). With the purchase of the largest pesticide producer, Syngenta, by the Chinese state-owned chemical company (the China National Chemical Corporation or simply ChemChina) in 2017, China entered the inner circles of power within the global agrochemical industry (Oliveira, He, and Ma Citation2020). In 2021, the long rumoured SinoChem–ChemChina merger was confirmed, creating an agrochemical behemoth (Wu Citation2021). The expiration of pesticide patents has made further room for Chinese ascendancy in the global agrochemical markets (Shattuck Citation2021). The global industry and its regulation remain dominated by Croplife International companies (BASF, Bayer CropScience, Corteva, FMC Corp., Sumitomo and Syngenta), which control three-quarters of the global market of highly harmful pesticides (Gaberell and Hoinkes Citation2019). These companies further consolidated the agribusiness lobby in Brazil by creating Croplife Brasil in 2019 to influence the Brazilian regulatory system.

It is estimated that only 0.1% of pesticides actually reach their object and the percentage is even lower for aviation spreading (Peshin and Pimentel Citation2014). The rest is drained into the environing landscapes and watersheds, eventually accumulating in animal and human bodies. Pests tend to develop immunity to pesticides, which induces producers to engage in a ‘pesticide treadmill’; no increase in pesticides is enough as the ‘pests’ will keep evolving immunities (van den Bosch Citation1978). This treadmill is bad for farmers as it increases their expenses, bad for farm workers due to increased application rates and bad for the environment as more toxic pesticides and pesticide ‘cocktails’ are applied. In the 1980s, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that pesticides cause some 220,000 deaths annually and over three million acute poisonings, mostly in the Global South. Today, these WHO numbers are outdated and ‘are likely severe underestimates given the increase in pesticide use since that time’ (Blair et al. Citation2015, 81). Furthermore, these figures do not include the more chronic impacts that ought to count in the hundreds of millions or even the entire human species (Zaller Citation2022). Indeed, human fertility rates, particularly sperm quality, have been decimated since the end of World War II and the often cited main culprit is pesticide use (Mehrpour et al. Citation2014; Sabarwal, Kumar, and Singh Citation2018). Toxins also degrade the soil ecosystems, harming the health and productivity of soils, which necessitates even more inputs, which deepens the problem further (IPES-Food Citation2016). There is thus a need to assess the dramatic increase in pesticide usage.

Political economy of pesticides in Brazil

Pesticides have become entrenched in Brazil as key agricultural inputs as part of the modernisation of agriculture, imposed first through the US green revolution from the 1960s. This was transformed into a national green revolution with the creation of the first National Development Plan (PND, 1972–1974) and the founding of the Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation, Embrapa, in 1973 (Cabral Citation2021). Under the PND, farmers were obliged to purchase pesticides to obtain rural credit (Gonzales Citation2021). Agricultural modernisation meant massive government programmes such as Proceder and Proálcool that incentivised large-scale monocultures in vast areas. As a result of the Volcker shock that increased the US interest rates threefold at the turn of the 1980s (Smith Citation2017), Brazil among other countries in the Global South saw their economies become subservient to global financial cores in the US. This took the form of the International Monetary Fund (IMF)’s structural adjustment programmes that further imposed chemical input-intensive ‘modernisation’ on their agriculture (Bauerly Citation2017; Clapp Citation2021; Khoury Citation2018).

In Brazil, a little over half of all the pesticides sold are used in soy production and some 10% each in maize and sugarcane production (Bombardi Citation2019). In terms of volume, soy represents 66% of all the pesticides applied, maize coming second with 13% and sugarcane accounting for a little over 5% (Pignati et al. Citation2017). As these three crops are mainly exported, the rapid expansion in the use of new pesticides is a global health concern due to pesticide residues (Braga et al. Citation2020). Notably, 80% of the pesticides are applied to genetically modified (GM) crops – soybean, maize and cotton (Burity Citation2020). Cancer is currently the second highest cause of death in Brazil and researchers have shown that pesticides are related to various types of cancer in Brazil (Gaberell and Hoinkes Citation2019). According to the data of the Ministry of Health, tests made between 2014 and 2017 showed that in every fourth municipality – out of 1396 municipalities – in Brazil, drinking water included traces of all 27 pesticides tested for, of which 16 are highly hazardous (Aranha and Rocha Citation2019).

There is an unequal trade relation related to commodity exports and agribusiness input imports. While Brazil exported agricultural products valued at about USD100 billion in 2018 (IDEFS Citation2019), its pesticide imports likely exceeded USD10 billion in 2020 (Pedlowski Citation2021). While it is difficult to know exactly the market sizes and trade of pesticides due to fraud and illegalities, the loss of tax and tariff revenues due merely to smuggling of pesticides is estimated to be around USD4 billion per year for the industry and domestic revenue (IDEFS Citation2019). The Brazilian farming area grew by about 50% from 2000 to 2017, while pesticide use grew by 232% (Bombardi Citation2019). In parallel, the share of pesticides in the cost of production has increased for several key crops. On average, between 2006 and 2017, the proportion of production costs expended on pesticides increased in Brazil from 1% to 15% for cotton, from 2% to 14% for soybean, and from 4% to 8% for sugarcane (Bombardi Citation2019). The cost of inputs for Brazilian farmers was estimated to have doubled during 2021 (Mendes Citation2021). For instance, the price of glyphosate more than doubled in 2021 and there were shortages of it in some regions (Agropages Citation2021). It is estimated that in 2022, the cost of soy production will increase 42% due to higher input prices as well as higher interest rates (Benites Citation2022). Even though parallel price increases of soy compensate for part of these cost hikes, they threaten the feasibility of these crops for even the most specialised farmers (Colussi, Schnitkey, and Zulauf Citation2021).

Pesticide use is rooted in the global food system and entails active lobbying by the powerful actors who benefit from it, mainly large transnational agrochemical corporations (Bombardi and Changoe Citation2022). The types of lobbying include designing policy support for ever larger scale farming, tailoring agricultural credit for chemical input-intensive farming, promoting and financing the type of academic research acritical to the use and impacts of pesticides, and making it exceedingly difficult for consumers to know about the content of their food (Shattuck Citation2021). Perhaps a most important political economic issue with the over two decades’ bonanza of agribusiness economy is that the lobby formed by agribusiness producers and large landowners that controls the production of agricultural commodities has become even more formidable (Castilho et al. Citation2022). This power is translated into a range of policies that provide various types of support for agribusiness. With tax exemptions alone, Brazil incentivises pesticide use by around USD2 billion each year (Montezuma Citation2020). Highly subsidised agricultural credit is mostly used to purchase inputs that are needed in industrial agriculture (Niederle et al. Citation2022). A recent example of this power is that with the price increases of pesticides, the tax for glyphosate imports was slashed by 60% in August 2022 (Agropages Citation2022). Such government support works squarely against pesticide-free – in particular, agroecological – food production, as chemical input-intensive and agroecological food production compete for the same land, state support and human resources (Sencébé, Pinton, and Cazella Citation2020).

As most of the pesticides are used in the export sector in agriculture, pesticides cannot be seen as contributing to domestic or local food security. Family farmers produce most of Brazil’s food, not the agribusiness that nevertheless uses most of the land and collects most of the state support (Sauer and Mészáros Citation2017). Also, as most of the Brazilian soybean goes to the Chinese pork industry (Oliveira, He, and Ma Citation2020), in a process that wastes nutrients, it cannot be claimed to contribute to the global food security. Notoriously, while the animal agriculture uses some 77% of global agricultural land, it produces only 18% of global calories and 37% of the global food supply (Ritchie Citation2019). Regardless of this, the agribusiness lobby keeps claiming that it feeds the world. The impact of pesticides is not confined to agricultural lands; there are sinister practices of spraying pesticides on forests, such as in the Amazon, to deforest areas for cattle, soy and land speculation (Freitas Citation2021). Brazilian forest monitoring state organs have often reacted in time to stop conventional forest clearing with the help of satellite monitoring, but when pesticides are used, they can only spot deforestation when it has already been concluded (Kröger Citation2022).

Approval of new pesticides in post-2016 Brazil

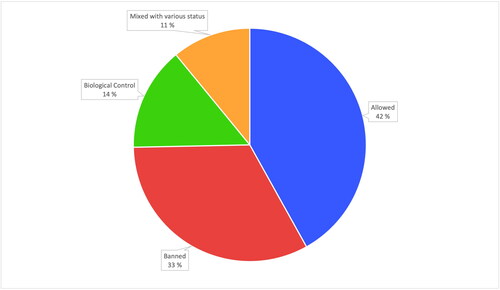

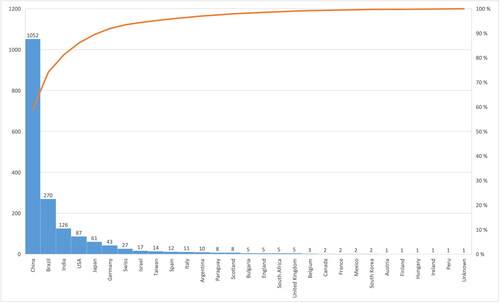

Based on our calculations, the surge in Brazilian pesticide approval means that instead of the typical approval of 100–150 pesticides per year during the PT era, the pace has been set at more than 500 pesticides per year since April 2016. From the beginning of 2019 until August 2022, 1783 newly approved pesticides were introduced into Brazilian markets. Of this set, 255 were biological controllers, biological substances or organisms that damage, kill, or repel organisms seen as pests, that were nearly entirely manufactured in Brazil. Of the 29 countries from which the pesticides were imported, China had by far the most products, 1052 or 59% of the entire set (see ). Of the total set of pesticides, a third are prohibited by the European Union (see ). Brazil produces 15% of all the products, and these are nearly all biological products. India manufactured 7% of all the products approved. The rest of the approved pesticides (less than 20% of the total) are produced in the other 26 countries, including European Union countries, which account for 4% of the total.

Figure 1. Classification of the pesticides approved by the Bolsonaro government in relation to their status within the EU, and biological pesticides.

Figure 2. Countries of origin of the 1783 pesticides released in Brazil under the Bolsonaro government from January 2019 to August 2022.

Considering world-systemic relations, the most important issue in the approval of new pesticides is that most of them come from China. The Chinese domination is premised on the expiration of patent rights of common pesticides and the subsequent rise of pesticide generics that China dominates (Shattuck Citation2021; Werner, Berndt, and Mansfield Citation2022). China has an interest in shipping back pesticides, as it imports massive amounts of soybean and other commodities from Brazil – both for the capitalist reason of controlling the input of these commodities and creating a dependent unequal trade relation. As soy production dominates the Brazilian pesticide scene, glyphosate generics that are used in soy production have been central to the surge in the use of pesticides (Clapp Citation2021) and most of these producers are Chinese. However, in terms of volumes of pesticides sold, the Croplife International members continue to dominate the Brazilian agrochemicals complex (Gaberell and Hoinkes Citation2019; Oliveira, He, and Ma Citation2020). The market leader, Syngenta, is nevertheless Chinese owned.

A significant proportion of the pesticides released for commercialisation in Brazil are banned in other countries because of their negative effects on human health and natural ecosystems. About 33% of registered pesticides are not authorised for sale in the European Union because they are too hazardous. Although most of the banned pesticides were already available in Brazil before, after the Brazilian National Health Surveillance Agency (ANVISA) relaxed regulations (Gurgel, Guedes, and Friedrich Citation2021), this paved the way for releasing generic and post-patent versions. Over 80% of the pesticides prohibited in the EU and released by the Bolsonaro government come from China.

Besides supposedly solving global hunger, the rapid growth in the approval of pesticides was justified by governmental officials as a means of lowering production costs for the Brazilian agricultural sector, as Tereza Cristina, the Minister of Agriculture of the Bolsonaro government until March 2022, kept arguing. However, in our view, the promise of lowering costs has not been fulfilled, for three basic reasons. The first is the governmental option to devalue the Brazilian real in relation to the US dollar. Given the dependency on pesticides produced abroad, a consequence of the national currency devaluation is that wholesale prices have increased, affecting the entire consumption chain of pesticides and chemical fertilisers. A second factor is the diminishing capacity of the Chinese industry to maintain its production levels because of the constraints associated with the COVID-19 pandemic. A third factor is related to the adoption of more stringent environmental laws in China that are stopping the use and production of pesticides largely used in Brazil. The combination of these three factors has caused production costs to skyrocket in Brazil, thereby placing additional constraints on profit margins.

Besides being a major consumer, Brazil aims to become a major pesticide producer and exporter. Brazil’s biopesticide production has grown by two-digit numbers and it is currently the fourth biggest biopesticide supplier (Langenbach et al. Citation2021). However, Bolsonaro signed Decree 10.8833/2021 on 7 October 2021, authorising the production and export of pesticides not authorised for use in Brazil, which could lead the country to become a major producer and exporter of highly harmful pesticide generics. In February 2022, the Brazilian Congress Lower Chamber approved the Law Project 6.299/2002 that, at the time of writing this article (October 2022), was under analysis by the Federal Senate. If accepted, this law, dubbed the Poison Law, would weaken all existing controls on pesticide usage, commercialisation and production. If the law is accepted, Brazil could start producing many more pesticides that are banned in other parts of the world, including the European Union, the USA and China, but also Brazil itself. However, the election of Lula as Brazil’s president (slated to begin in January 2023) suggests that the pesticide regime’s most toxic paths are likely to be at least partly curbed or checked. In his victory speech on 30 October 2022, Lula hinted at his commitment to the adoption of a new agricultural model based on agroecological values that will protect forests and natural ecosystems.

Dismantling pesticide regulation

With the parliamentary coup of 2016 (Braga and Purdy Citation2019), the Brazilian state infrastructure that had supported and crafted agroecological family farming policies over decades with the participation of civil society organisations was dissolved through the termination of a series of laws, programmes and councils (Castro Citation2019; Niederle et al. Citation2022; Sabourin et al. Citation2020). In the first week in power, the interim government of Michel Temer abolished the Ministry of Agrarian Development (MDA) that had promoted family farming since the end of the 1990s. Right after being elected, Bolsonaro started weakening key environmental state institutions and ministries and staffing them with pro-agribusiness people (ASCEMA Citation2021). In December 2018 Bolsonaro stated: ‘I will no longer allow IBAMA [Brazilian Institute of Environment and Renewable Natural Resources] to go around fining left and right, as well as ICMBio [Chico Mendes Institute for Biodiversity Conservation]. This party will end’ (ASCEMA Citation2021, 5). Bolsonaro even attempted to terminate the Ministry of the Environment (MMA), a manoeuvre that did not work out but nevertheless ended up weakening the ministry (Menezes and Barbosa Citation2021). Bolsonaro said in a meeting with the Agriculture Parliamentary Front (FPA):

We had the idea of merging the Ministry of Agriculture with the Ministry of Environment, but then concluded that this was not the case, even talking to many of you. And we have now a minister of the environment who is married to you. (quoted in Rodrigues Citation2019)

After 2016, the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock, and Food Supply (MAPA), that supports the agribusiness category of producers, began to grab the former responsibilities of MMA and MDA, and other state organs, and dissolving their progressive agendas (Niederle et al. Citation2022). On his second day as president, Bolsonaro further consolidated the position of MAPA as a dominant ministry. For instance, the Brazilian Forestry Service (SFB) and Rural Environmental Registry (CAR) were moved to MAPA. However, before even that, on the first day in office, Bolsonaro dissolved CONSEA, the Brazilian National Food and Nutritional Security Council that had been created in 1993, previously dissolved by Fernando Henrique Cardoso (president from 1995 to 2002) and recreated by Lula in 2003. CONSEA had been the most prominent ‘space for dialogue, articulation, mutual learning and concertation between government and society’ (Castro Citation2019, 1). Within CONSEA, ‘civil society representatives were given the directorship and two-thirds of the seats, with ministerial representatives holding the remaining one-third’ (Sencébé, Pinton, and Cazella Citation2020, 200). Among other issues, this flagship agency in the policy agenda had advanced agroecology and hindered the use of pesticides (Niederle et al. Citation2022; Sencébé, Pinton, and Cazella Citation2020) and was pivotal in creating the Food Acquisition Program (PAA) that constituted the main institutional market for agroecological production (Niederle et al. Citation2022).

Regarding pesticide use, ANVISA was transformed under the Bolsonaro government, which downplayed research and impact analysis of pesticide usage (Gurgel, Guedes, and Friedrich Citation2021). In July 2019, ANVISA established a new set of regulations for approving pesticides in Brazil under the argument of conducting a necessary adjustment to the Globally Harmonized System of Classification and Labelling of Chemicals (GHS) (Burity Citation2020). Due to this change, the number of products classified as extremely toxic to humans fell dramatically, from 702 to 43 of the overall 1942 pesticides sold in Brazil in 2019 (Cancian Citation2019). The new guidelines do not even comply with the latest standards set by the GHS in 2015 because the evaluation of potential toxic effects of pesticides was limited to the immediate physical risks caused by inhalation, whereas ingestion, direct contact and the long-term health effects of handling and using these chemical products were disregarded. These policies are highly detrimental in the country in which ‘pesticides contaminate approximately 70% of food consumed by Brazilians, and they drink nearly 7.5 litres of pesticides per year – the highest per capita consumption rate in the world’, according to the estimations of the Brazilian Association of Collective Health (Lopes-Ferreira et al. Citation2022, 4).

As the above narration clarifies, clearing the way for the expansion of chemical input-intensive agriculture has been comprehensive and deliberate. It has taken place on several fronts: by attacking and undermining state institutions supporting agroecological family farming, dismantling the Brazilian environmental protection arrangements, and de-regulating the use and production of pesticides (Niederle et al. Citation2022). These moves also had direct impacts in terms of a slide from expert and democracy-based institutions towards science-ignoring authoritarianism. Why did the Temer and Bolsonaro governments see it as a top priority to dismantle the support for agroecological production in its diverse manifestations? To a significant degree, both agroecological family farming and environmental protection had been formulated within participatory decision-making spaces (Castro Citation2019; Menezes and Barbosa Citation2021), and it may well be that these participatory arenas of policymaking would have barred or at least challenged the policies that Bolsonaro wanted to advance. He said in an event with agribusiness, ‘we have to not do, first we have to undo what was done and then do it’ (quoted in Rodrigues Citation2019).

The inner workings of the agribusiness lobby

The Bolsonaro regime radically narrowed the kind of actors who can participate in policymaking arenas. A comprehensive report (Castilho et al. Citation2022) details how the agribusiness lobby took over the Ministry of Agriculture. This took place through the symbiosis of the FPA and a ‘think tank’ called Pensar Agro Institute (IPA). These entities have the same email address, same logo and same mailing address – a luxury mansion in which congress members met every Tuesday (Castilho et al. Citation2022, 6). The IPA wrote ‘drafts and reports for anti-environmental bills submitted by FPA politicians, such as the Poison Bill’ (Castilho et al. Citation2022, 4). The IPA is funded by its 48 members, industry associations such as the CNA and the Industrial Federation of the State of São Paulo (FIESP), the most powerful business association in the country, which also played a major role in Dilma Rousseff’s impeachment (Loureiro and Saad-Filho Citation2019). Companies and large landowners are members of these associations; the biggest companies are members of many of these associations. In June 2022, the IPA contained 1079 companies and nearly 70,000 individuals. Bolsonaro said in a breakfast meeting with the FPA that ‘this government is yours’ (Rodrigues Citation2019), this being reflected in their frequent state visits.

While most of the companies and individual landowners that constitute the membership of the IPA are Brazilian, the largest of them are multinational corporations, such as Syngenta, Bayer, BASF, Archer Daniels Midland (ADM), Bunge, Louis Dreyfus (LDC), Cargill and Cofco. Castilho et al. write: ‘national companies do not lead the political influence … [the] leaders are, mostly, multinationals’ (2022, 7). The most active have been Syngenta with 81 meetings with MAPA, followed by Bayer with 60 official and 16 unofficial meetings (Castilho et al. Citation2022). There could also be a corrupt relationship between the pesticide companies and lawmakers. For instance, Castilho et al. (Citation2022) claim that ‘Syngenta is directly connected to the “Poison Bill”’, because the rapporteur of the bill, federal deputy Luiz Nishimori, ‘signed in December 2020 an agreement to end a debt of R$1.5 million (USD 278,000) that his company had with the multinational’ (Castilho et al. Citation2022, 14). Through agribusiness associations, Bayer, BASF and Syngenta ‘contributed around 2 million euros to support the lobby activities’ of the IPA (Bombardi and Changoe Citation2022, 14).

The change from the Temer interim government to the Bolsonaro regime was drastic in terms of the connections between agribusiness and government officials. While the Bolsonaro administration in the MAPA met with the associates of IPA more than 400 times between January 2019 and June 2020, the MAPA of the Temer government met only 36 times with agribusiness lobbies within a similar time frame (Castilho et al. Citation2022). For their part, peasant associations embracing agroecology had meetings with the MAPA officials during the Bolsonaro government only twice and the indigenous groups never. During the PT era (2003–2016), the peasant and indigenous social movements were a legitimate part of several important state–civil society governance councils. With the dissolution of various councils that secured the access of civil society to policymaking arenas, alternative voices within the state organs seems to be effectively silenced. At a structural or systemic level of the political economy, this shift in access to decision-making can be partly explained by the challenge that agroecology produces for the pesticide regime.

Alternatives to pesticides

Agriculture faces a quadruple challenge: increasing food production; mitigating climate change; adapting to climate change; and enhancing equity and social justice (Ollinaho and Kröger Citation2021). Expensive solutions, such as practices that rely on externally produced inputs, including pesticides, create virtually indispensably unequal creditor–debtor relations not only at the level of production, but also at the international level (McMichael Citation2020). Through such practices, a system of dependence is imposed on farmers and Third World countries that is typically highly disadvantageous for them. One of the extreme cases has been India, where hundreds of thousands of peasants have committed suicide due to indebtedness (Mohanty Citation2005).

Agroecological practices, a broad set of multi-species land-use practices having as their common aim the improvement of yields in a sustainable manner by addressing soil fertility and pest control through biological and in-farm methods, make soil ecosystems thrive, thereby also increasing soil carbon. Such practices are cheap to adopt and they increase the capacities and autonomy of producers (van der Ploeg and Schneider Citation2022) as well as the food sovereignty of the nations within which they are situated (Dale Citation2021). Obviously, abruptly banning the use of chemical inputs would be ill advised, as Sri Lanka’s 2022 catastrophe, when food production radically dropped with the top-down ban of agrochemical imports, testifies (Bhowmick Citation2022). Cuba was forced to start agroecological transition as the agrochemical imports from the Soviet Union stopped abruptly with the collapse of the communist bloc in 1989–1990. It took a long time for Cuba to refashion its agricultural system, and central in this was social re-organisation towards agroecological practices. Agroecological transition in Cuba took place through a social movement (Campesino-to-Campesino Agroecology Movement), in which agroecological practices are taught through peasant networks (Rosset et al. Citation2011). This movement worked within the National Association of Small Farmers (ANAP), itself a member of La Vía Campesina (LVC).

Agroecological transition requires changing the structure of land ownership and access to state support, both of which entail changes in the political system governing these. Land reform has been a watershed policy that divided countries that were allowed to be developed, such as Japan and South Korea, and those that were kept underdeveloped, such as Guatemala and Brazil (Evans Citation1995). While agroecological practices such as agroforestry have been pilot tested in larger farms of some thousands of hectares (Levidow, Sansolo, and Schiavinatto Citation2021), it ought to be seen that agroecological practices are more suitable for smaller areas due to the more intensive land use. For this density, agroecological transitions would more likely also mean a halt in the expansion of agricultural frontiers and migration back to the countryside. This would have major political impacts locally and nationally (Kröger Citation2022). Agroecology is not only about diffusing good farming practices that embrace and build on socio-biodiversity, entail multiple-species land use, and enhance soil ecosystems, but also about radically reorganising food production.

Before 2016, Brazil was one of the main countries advancing agroecological public policies (da Costa et al. Citation2017; Van den Berg et al. Citation2022), even though agribusiness interests were advanced in parallel (Sauer and Mészáros Citation2017). Agroecology managed to enter various university curricula (Rivera-Ferre et al. Citation2021), succeeding in reshaping the work of public research actors and in particular their relationships with policymakers in various participatory food governance and decision-making councils (Castro Citation2019; Niederle et al. Citation2022). The PT governments provided mechanisms for promoting pesticide-free agroecological family farming, such as participative policymaking arenas and public food procurement programmes (Niederle et al. Citation2022). The PT governments also created laws, policies and councils that articulated the needs of agroecology at the state level through transparent and participatory means. Consultation and participatory forms of decision-making have been at the core of agroecology (Van den Berg et al. Citation2022). It may be that the participatory system in and over which pesticides lobby had little say might have been a key reason for the urgency with which the far-right began to dismantle the participatory system. Moreover, pesticides also function as a technological lock-in, thus preventing future opportunities for using the poisoned lands or lands close to them for organic production (Clapp Citation2021). The topic of land control has been the most important goal of Brazil’s elites for over 500 years.

Conclusions

While Brazil has been on the bandwagon of chemical input-intensive agricultural development for a long time (even during the first PT regime, 2003–2016), there has been a rapid increase in legalisation of highly toxic pesticides in Brazil since the parliamentary coup of 2016, and especially since 2019 when Jair Bolsonaro assumed the presidency of Brazil. Based on the legalisation statistics and policy analysis, we explored several explanations for how and why this toxic turn has taken place. There has been a parallel dissolution of state support for agroecology and environmental regulations. In this light, the transnational agribusiness behind these moves, joined with the political ‘rural elite’ through the symbiosis of IPA and the FPA, have been seen as driving extractivist and increasingly poisonous patterns of maldevelopment in Brazil (Russo Lopes, Bastos Lima, and dos Reis Citation2021).

The set of pesticides liberated for use in Brazil reaffirms the generic turn in global pesticide production (see Shattuck Citation2021). Indeed, the most important aspect in the current global pesticide trade is the ever-tightening China–Brazil nexus, their relationship reproducing the historically unequal core–periphery trade relations. China increasingly produces inputs for Brazil for it to produce especially soybeans for the Chinese pork industry (Oliveira, He, and Ma Citation2020). While the US- and EU-based agrochemical giants maintain their dominant role in the Brazilian pesticide market, the US has lost some control (or at least direct ownership) in these corporations – in parallel with China entering the core of the agrochemical sector with the purchase of Syngenta, the biggest player in the Brazilian markets and most active in lobbying for deregulation of pesticides (Castilho et al. Citation2022).

It seems that Brazilian agriculture has ‘locked in’ a process of increasing pesticide use through manifold policy and institutional changes, hard-to-reverse approvals of new pesticides, and establishment of a pro-pesticide import and export regime. From a developmental and sustainability perspective, this lock-in can be seen as highly disadvantageous to Brazil as a whole, as the business-as-usual continuation (Ollinaho Citation2022) of such a pattern would deepen Brazil’s peripheral position in the world system as a raw material supplier for the central states (Bombardi and Changoe Citation2022). Both the global superpowers, the US and China, but also Japan and European countries have been involved in these developments through their agribusiness giants (Castilho et al. Citation2022). Brazilian soybean and corn plantation owners have been profiting much from the state-supported bonanza and the seemingly inexhaustible Chinese demand for their produce. However, the profits of these entrepreneurial farmers who rely on the importation of pesticides have been vanishing due to the rising pesticide and fertiliser prices (Colussi, Schnitkey, and Zulauf Citation2021; Kröger Citation2022).

Despite the overall weakening and capture attempt of state institutions for a pro-pesticide agenda, the political support for agroecology that succeeded to embed the state during the PT regime still resides in several Brazilian public organs, as exemplified by the Brazilian National Cancer Institute (INCA), which argues that agroecology is the solution to pesticides (INCA Citation2021). As another example, the Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation, Embrapa, has been capable of promoting and developing biological pesticides that are less problematic than chemical pesticides, including in matters of national autonomy. This suggests that the toxic turn, while being a reality in post-2016 Brazil and particularly in the Bolsonaro era, has not been completely victorious, and important vestiges of agroecology remain in some institutions and several rural practices. Perhaps the most evident resistance to the pro-pesticide agenda resides in the social movements that increasingly rely on agroecological production (Niederle et al. Citation2022; Van den Berg et al. Citation2022) and that often bring women to the fore as central actors in more inclusive, respectful, just, and sustainable agriculture (Naves and Fontoura Citation2022).

Pesticide legalisation in Brazil is one example of the broader power changes since 2016 in the country. The authoritarian post-2016 governments in Brazil started to pull apart the inner workings of the state governance system in which civil society had managed to enter in the form of various councils, such as CONSEA. Creating broader support for agroecology and environmental protection seems to require challenging the power of the ultra-conservative elites in situ in the arenas where policies are crafted, but also the world systemic lock-in in pesticide-based agriculture. We see that the ‘agrobattle’ over the Brazilian food system is perhaps the most prominent issue determining the success of the new PT regime and that the new government should politicise pesticide use as a major, multidimensional problem of the ‘agribusiness economy’. While pesticides are typically not experienced as relevant to the average citizen due to their cumulative impacts over time, researchers should translate the harms of pesticides so that they also touch on the pragmatic relevance of the typical citizen (Ollinaho Citation2016). At the global level, it would be essential for adherents of agroecology to be able to embed and co-produce the state and global governance organisations (Kröger Citation2020), in the form of participatory decision-making arenas.

Scientists and practitioners of agroecology have already shown that pesticides are not needed to feed the world (IAASTD Citation2009), but more research is needed on the actual political economic settings hindering the systemic transformations and actions needed to pursue pesticide-free futures. There is in particular a need to provide further knowledge on paths to agroecological solutions, spanning from feasibility calculations designed for agroecological production to policy tools on governing decentralised, rhizomatic (Deleuze and Guattari Citation1989; Kuronen and Huhtinen Citation2017), agroecological production systems and symbioses (Helenius, Hagolani-Albov, and Koppelmäki Citation2020). Agroecolocial agroforestry transitions would be important regarding restoring depleted soils, and fostering biodiversity and soil carbon (Ollinaho and Kröger Citation2021; Toensmeier Citation2016). Increased social scientific research on pesticides and their alternatives carries high potential for starting to challenge the pesticide-based global agribusiness models: a shift to and increase in focus on these issues by social scientists would carry major policy impacts, given the deep institutionalisation of pesticide acceptance among governments and trade agreements.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to two anonymous referees who offered critical but helpful and supportive comments and questions to improve the article. It is rare to find a more encouraging referee’s opening sentence than ‘I am wildly enthusiastic about this piece and I want it in print as soon as possible’. We also thank the Managing Editor Madeleine Hatfield for the sound and smooth publication process. An initial version of this article was presented in 2020 in the Development Days conference of the Finnish Society for Development Research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ossi I. Ollinaho

Ossi I. Ollinaho works currently as a lecturer in global development studies at the University of Helsinki, Faculty of Social Sciences, Finland. In his research on social theory, building on Alfred Schutz’s social phenomenology, Dr. Ollinaho has theorised a cumulative type of change as one basic type of social change prevalent in contemporary realities. He has also provided conceptual insights on issues such as ‘business as usual’, environmental change, virtualisation of life-worlds, extractivisms, and economics with an aim to better understand contemporary human and other-than-human conditions. In his more empirical work conducted mostly in Brazil, he has focused on agroforestry, agroecology and renewable energies as part of critical agrarian studies. To date, he has published his work in (in chronological order): Environmental Sociology, Autrepart, Review of African Political Economy, Revista NERA, Human Studies, Sustainability, Journal of Rural Studies, Journal of Peasant Studies, and Globalizations.

Marcos A. Pedlowski

Marcos Antonio Pedlowski completed his bachelor’s degree in geography at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro in 1986, where he also obtained his master’s degree in geography in 1990. In 1997, he obtained his PhD in environmental design and planning at the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University (Virginia Tech). Since 1998 he has been Associate Professor at the Laboratory of Studies of the Anthropic Space at the Darcy Ribeiro North Fluminense State University, Brazil. He has extensive experience in the area of environmental studies, with an emphasis on geographic approaches. He has been working mainly on agrarian reform, changes in vegetation cover and land use in the Amazon, and on studies about the social and environmental impacts of the use of pesticides in Brazilian agriculture. He keeps a blog (https://blogdopedlowski.com) that aims to make critical research on these issues more visible.

Markus Kröger

Markus Kröger is a professor of global development studies at the University of Helsinki, Faculty of Social Sciences, Finland. He has published extensively on the political economy of development and natural resource extraction, social movements, and forestry and mining policies. He has published four monographs. His first book, Contentious Agency and Natural Resource Politics, discusses the global industrial forestry sector. Iron Will: Global Extractivism and Mining Resistance in Brazil and India presents a theory of investment politics and spatial causalities to explain through which strategies social movements succeed in their resistance. Studying Complex Interactions and Outcomes Through Qualitative Comparative Analysis is a hands-on methodological guidebook. His latest book, Extractivisms, Existences and Extinctions: Monoculture Plantations and Amazon Deforestation, offers a new theory of political economy of existences.

Bibliography

- Agropages. 2021. “Agri-Input Prices More than Double in 2021, Increase Costs for 2022 in Brazil.” Agropages, November 8.

- Agropages. 2022. “Brazil Reduces Glyphosate Import Tax from 9.6% to 3.8%.” Agropages, August 8.

- Altieri, M. A. 1989. “Agroecology: A New Research and Development Paradigm for World Agriculture.” Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 27 (1-4): 37–46. doi:10.1016/0167-8809(89)90070-4.

- Altieri, M. A. 2009. “Agroecology, Small Farms, and Food Sovereignty.” Monthly Review 61 (3): 102. doi:10.14452/MR-061-03-2009-07_8.

- Andrade, D. 2022. “Neoliberal Extractivism: Brazil in the Twenty-First Century.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 49 (4): 793–816. doi:10.1080/03066150.2022.2030314.

- Aranha, A., and L. Rocha. 2019. “Coquetel’ Com 27 Agrotóxicos Foi Achado Na Água de 1 Em Cada 4 Municípios – Consulte o Seu.” Agência Pública, April 15.

- ASCEMA. 2021. Cronologia de Um Desastre Anunciado: Ações Do Governo Bolsonaro Para Desmontar as Políticas de Meio Ambiente No Brasil. Brasília, Brazil: Associação Nacional dos Servidores de Meio Ambiente.

- Bauerly, B. 2017. The Agrarian Seeds of Empire: The Political Economy of Agriculture in US State Building. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill.

- Benites, S. 2022. “Alta de Insumos e Guerra Elevam Em 42% Custo Da Produção de Soja.” Correio Do Estado, August 24.

- Bhowmick, S. 2022. “Understanding the Economic Issues in Sri Lanka’s Current Debacle.” Observer Research Foundation Occassional Paper, no. 357, 36.

- Blair, A., B. Ritz, C. Wesseling, and L. B. Freeman. 2015. “Pesticides and Human Health.” Occupational and Environmental Medicine 72 (2): 81–82. doi:10.1136/oemed-2014-102454.

- Bombardi, L. M. 2019. A Geography of Agrotoxins Use in Brazil and Its Relations to the European Union. São Paulo, Brazil: FFLCH, USP.

- Bombardi, L. M., and A. Changoe. 2022. Toxic Trading: The EU Pesticide Lobby’s Offensive in Brazil. Brussels, Belgium: Friends of the Earth Europe & Seattle to Brussels Network.

- Braga, A. R. C., V. V. de Rosso, C. A. Y. Harayashiki, P. C. Jimenez, and . Braga Castro. 2020. “Global Health Risks from Pesticide Use in Brazil.” Nature Food 1 (6): 312–314. doi:10.1038/s43016-020-0100-3.

- Braga, R., and S. Purdy. 2019. “A Precarious Hegemony: Neo-Liberalism, Social Struggles, and the End of Lulismo in Brazil.” Globalizations 16 (2): 201–215. doi:10.1080/14747731.2018.1479013.

- Burity, V. T. A. 2020. Pesticides in Latin America: Violations against the Right to Adequate Food and Nutrition. Brasília, Brazil: FIAN Brasil.

- Cabral, L. 2021. “Embrapa and the Construction of Scientific Heritage in Brazilian Agriculture: Sowing Memory.” Development Policy Review 39 (5): 789–810. doi:10.1111/dpr.12531.

- Cancian, N. 2019. “Regra Nova Faz Agrotóxicos Extremamente Tóxicos Irem de 702 a 43.” Folha de S. Paulo, August 2.

- Castilho, A. L., B. S. Bassi, C. d. Freitas Paes, L. Linder, L. Fuhrmann, and M. F. Ramos. 2022. The Financiers of Destruction: How Multinational Companies Sponsor Agribusiness Lobby and Sustain the Dismantling of Socio-Environmental Regulation in Brazil. São Paulo, Brazil: De Olho nos Ruralistas: Observatório do agronegócio no Brasil.

- Castro, I. R. R. d. 2019. “The Dissolution of the Brazilian National Food and Nutritional Security Council and the Food and Nutrition Agenda.” Cadernos de saude publica 35 (2): e00009919. doi:10.1590/0102-311x00009919.

- Clapp, J. 2021. “Explaining Growing Glyphosate Use: The Political Economy of Herbicide-Dependent Agriculture.” Global Environmental Change 67: 102239. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2021.102239.

- Colussi, J., G. Schnitkey, and C. Zulauf. 2021. “Rising Fertilizer Prices to Affect Brazil’s Largest Corn Crop.” Farmdoc Daily, November 8.

- da Costa, M. B. B., M. Souza, V. M. Júnior, J. J. Comin, and P. E. Lovato. 2017. “Agroecology Development in Brazil between 1970 and 2015.” Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems 41 (3-4): 276–295. doi:10.1080/21683565.2017.1285382.

- Dale, B. 2021. “Food Sovereignty and the Integral State: Institutionalizing Ecological Farming.” Geoforum 127: 137–150. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2021.10.010.

- Deleuze, G., and F. Guattari. 1989. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

- Evans, P. B. 1995. Embedded Autonomy: States and Industrial Transformation. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- FAO. 2019. Pesticides Use: Global, Regional and Country Trends 1990–2018. 16. Rome, Italy: FAO.

- FAO and WHO. 2019. Detoxifying Agriculture and Health from Highly Hazardous Pesticides: A Call for Action. Rome, Italy: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations World Health Organization.

- Fernández, L. 2021. “Market Value of Chemical Pesticide Manufacturing in China from 2011 to 2021.” Statista, October 11.

- Freitas, H. 2021. “Fazendeiros Jogam Agrotóxico Sobre Amazônia Para Acelerar Desmatamento.” Repórter Brasil, November 16.

- Gaberell, L., and C. Hoinkes., 2019. Highly Hazardous Profits: How Syngenta Makes Billions by Selling Toxic Pesticides. Lausanne, Switzerland: Public Eye.

- Glaeser, B., ed. 2011. The Green Revolution Revisited: Critique and Alternatives. London, UK: Routledge.

- Gonzales, J. 2021. “Brazil’s Fundamental Pesticide Law under Attack.” Mongabay, February 20.

- Gurgel, A. M., C. A. Guedes, and K. Friedrich. 2021. “Flexibilização da regulação de agrotóxicos enquanto oportunidade Para a (necro)política brasileira: avanços do agronegócio e retrocessos Para a saúde e o ambiente.” Desenvolvimento e Meio Ambiente 57: 135–159. doi:10.5380/dma.v57i0.79158.

- Helenius, J., S. E. Hagolani-Albov, and K. Koppelmäki. 2020. “Co-Creating Agroecological Symbioses (AES) for Sustainable Food System Networks.” Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems 4: 588715. doi:10.3389/fsufs.2020.588715.

- Hickel, J., D. Sullivan, and H. Zoomkawala. 2021. “Plunder in the Post-Colonial Era: Quantifying Drain from the Global South Through Unequal Exchange, 1960–2018.” New Political Economy 26 (6): 1030–1047. doi:10.1080/13563467.2021.1899153.

- IAASTD. 2009. Agriculture at a Crossroads: The Global Report of the International Assessment of Agricultural Knowledge, Science, and Technology. Washington, DC: Island Press.

- IDEFS. 2019. Smuggling of Pesticides in Brazil. Foz do Iguaçu, Brazil: Instituto de Desenvolvimento Econômico e Social de Fronteiras.

- INCA. 2021. “Agrotóxico.” Accessed November 15, 2021. https://www.inca.gov.br/en/node/1909

- IPES-Food. 2016. From Uniformity to Diversity: A Paradigm Shift from Industrial Agriculture to Diversified Agroecological Systems International Panel of Experts on Sustainable Food Systems report 02.

- Khoury, S. 2018. “Pesticideland: Brazil’s Poison Market.” Pp. 174–187 in Revisiting Crimes of the Powerful: Marxism, Crime and Deviance, edited by S. Bittle, L. Snider, S. Tombs, and Whyte. London, UK: Routledge.

- Kröger, M. 2020. Iron Will: Global Extractivisms and Mining Resistance in Brazil and India. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

- Kröger, M. 2022. Extractivisms, Existences, and Extinctions: Monoculture Plantations and Amazon Deforestation. Oxon, UK: Routledge.

- Kuronen, T., and A.-M. Huhtinen. 2017. “Organizing Conflict: The Rhizome of Jihad.” Journal of Management Inquiry 26 (1): 47–61. doi:10.1177/1056492616665172.

- Langenbach, T., L. Caldas, T. De Campos, F. Correia, N. Lorenz, D. Marinho, D. Mano, et al. 2021. “Perspectives on Sustainable Pesticide Control in Brazil.” World 2 (2): 295–301. doi:10.3390/world2020018.

- Levidow, L., D. Sansolo, and M. Schiavinatto. 2021. “Agroecological Practices as Territorial Development: An Analytical Schema from Brazilian Case Studies.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 48 (4): 827–852. doi:10.1080/03066150.2019.1683003.

- Lopes-Ferreira, M, A. L. A. Maleski, L. Balan-Lima, J. T. G. Bernardo, L. M. Hipolito, A. C. Seni-Silva, J. Batista-Filho, M. A. P. Falcao, and C. Lima. 2022. “Impact of Pesticides on Human Health in the Last Six Years in Brazil.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19 (6): 3198. doi:10.3390/ijerph19063198.

- Loureiro, P. M., and A. Saad-Filho. 2019. “The Limits of Pragmatism: The Rise and Fall of the Brazilian Workers’ Party (2002–2016).” Latin American Perspectives 46 (1): 66–84. doi:10.1177/0094582X18805093.

- McMichael, P. 2020. “Does China’s ‘Going Out’ Strategy Prefigure a New Food Regime?” The Journal of Peasant Studies 47 (1): 116–154. doi:10.1080/03066150.2019.1693368.

- Mehrpour, O., P. Karrari, N. Zamani, A. M. Tsatsakis, and M. Abdollahi. 2014. “Occupational Exposure to Pesticides and Consequences on Male Semen and Fertility: A Review.” Toxicology Letters 230 (2): 146–156. doi:10.1016/j.toxlet.2014.01.029.

- Mendes, P. 2021. “Agronegócio Bate Recorde de Exportações Em 2021.” R7 Brasília, December 8.

- Menezes, R. G., and R. Barbosa. 2021. “Environmental Governance under Bolsonaro: Dismantling Institutions, Curtailing Participation, Delegitimising Opposition.” Zeitschrift für Vergleichende Politikwissenschaft 15 (2): 229–247. doi:10.1007/s12286-021-00491-8.

- Milhorance, C. 2022. “Policy Dismantling and Democratic Regression in Brazil under Bolsonaro: Coalition Politics, Ideas, and Underlying Discourses.” Review of Policy Research 39 (6): 752–770. doi:10.1111/ropr.12502.

- Mohanty, B. B. 2005. “‘We Are Like the Living Dead’: Farmer Suicides in Maharashtra, Western India.” Journal of Peasant Studies 32 (2): 243–276. doi:10.1080/03066150500094485.

- Montezuma, T. d. F. P. F. 2020. “A Politica de Isenção Fiscal de Agrotóxicos No Brasil: discursos e interesses em disputa na ADI 5553.” InSURgência: revista de direitos e movimentos sociais 5 (1): 562–577. doi:10.26512/insurgencia.v5i1.28901.

- Naves, F., and Y. Fontoura. 2022. “Feminist Resistance Building in the Brazilian Agroecology Movement: A Gender Decoloniality Study.” Gender, Work & Organization 29 (2): 408–426. doi:10.1111/gwao.12767.

- Niederle, P., P. Petersen, E. Coudel, C. Grisa, C. Schmitt, E. Sabourin, E. Schneider, A. Brandenburg, and C. Lamine. 2022. “Ruptures in the Agroecological Transitions: Institutional Change and Policy Dismantling in Brazil.” The Journal of Peasant Studies, 1–23. doi:10.1080/03066150.2022.2055468.

- Oliveira, G. d. L. T., C. He, and J. Ma. 2020. “Global-Local Interactions in Agrochemical Industry: Relating Trade Regulations in Brazil to Environmental and Spatial Restructuring in China.” Applied Geography 123: 102244. doi:10.1016/j.apgeog.2020.102244.

- Ollinaho, O. I. 2016. “Environmental Destruction as (Objectively) Uneventful and (Subjectively) Irrelevant.” Environmental Sociology 2 (1): 53–63. doi:10.1080/23251042.2015.1114207.

- Ollinaho, O. I. 2022. “What Is ‘Business as Usual’? Towards a Theory of Cumulative Sociomaterial Change.” Globalizations, 1–17. doi:10.1080/14747731.2022.2142013.

- Ollinaho, O. I., and M. Kröger. 2021. “Agroforestry Transitions: The Good, the Bad and the Ugly.” Journal of Rural Studies 82: 210–221. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2021.01.016.

- Pedlowski, M. 2021. “Lucro Tóxico: Venda de Agrotóxicos Teve Maior Resultado de Vendas Dos Últimos Cinco Anos Em 2020.” Blog de Pedlowski. https://blogdopedlowski.com/2021/02/17/lucro-toxico-venda-de-agrotoxicos-teve-maior-resultado-de-vendas-dos-ultimos-cinco-anos-em-2020/

- Peshin, R., and D. Pimentel, eds. 2014. Integrated Pest Management. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands.

- Pignati, W. A., F. A. N. d. S. Lima, S. S. d. Lara, M. L. M. Correa, J. R. Barbosa, L. H. d. C. Leão, and M. G. Pignatti. 2017. “Spatial Distribution of Pesticide Use in Brazil: A Strategy for Health Surveillance.” Ciencia & Saude Coletiva 22 (10): 3281–3293. doi:10.1590/1413-812320172210.17742017.

- Pisa, L., D. Goulson, E.-C. Yang, D. Gibbons, F. Sánchez-Bayo, E. Mitchell, A. Aebi, et al. 2021. “An Update of the Worldwide Integrated Assessment (WIA) on Systemic Insecticides. Part 2: Impacts on Organisms and Ecosystems.” Environmental Science and Pollution Research International 28 (10): 11749–11797. doi:10.1007/s11356-017-0341-3.

- ReportLinker. 2021. “Pesticide And Other Agricultural Chemicals Global Market Report 2021: COVID 19 Impact and Recovery to 2030.” GlobeNewsWire, February 3.

- Ritchie, H. 2019. “Half of the World’s Habitable Land Is Used for Agriculture.” Our World in Data. Accessed October 27, 2022. https://ourworldindata.org/global-land-for-agriculture

- Rivera-Ferre, M. G., D. Gallar, Á. Calle-Collado, and V. Pimentel. 2021. “Agroecological Education for Food Sovereignty: Insights from Formal and Non-Formal Spheres in Brazil and Spain.” Journal of Rural Studies 88: 138–148. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2021.10.003.

- Rodrigues, S. 2019. “Esse governo é de vocês’, diz Bolsonaro a Ruralistas.” ((o))eco, April 7.

- Rosset, P. M., B. M. Sosa, A. M. R. Jaime, and D. R. Á. Lozano. 2011. “The Campesino-to-Campesino Agroecology Movement of ANAP in Cuba: Social Process Methodology in the Construction of Sustainable Peasant Agriculture and Food Sovereignty.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 38 (1): 161–191. doi:10.1080/03066150.2010.538584.

- Russo Lopes, G., M. G. Bastos Lima, and T. N. P. dos Reis. 2021. “Maldevelopment Revisited: Inclusiveness and Social Impacts of Soy Expansion over Brazil’s Cerrado in Matopiba.” World Development 139: 105316. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105316.

- Sabarwal, A., K. Kumar, and R. P. Singh. 2018. “Hazardous Effects of Chemical Pesticides on Human Health–Cancer and Other Associated Disorders.” Environmental Toxicology and Pharmacology 63: 103–114. doi:10.1016/j.etap.2018.08.018.

- Sabourin, E., C. Grisa, P. Niederle, S. Pereira Leite, C. Milhorance, A. Damasceno Ferreira, S. Sauer, and J. M. Andriguetto-Filho. 2020. “Le démantèlement des politiques publiques rurales et environnementales au Brésil.” Cahiers Agricultures 29: 31. doi:10.1051/cagri/2020029.

- Sauer, S., and G. Mészáros. 2017. “The Political Economy of Land Struggle in Brazil under Workers’ Party Governments.” Journal of Agrarian Change 17 (2): 397–414. doi:10.1111/joac.12206.

- Sencébé, Y., F. Pinton, and A. A. Cazella. 2020. “On the Unequal Coexistence of Agrifood Systems in Brazil.” Review of Agricultural, Food and Environmental Studies 101 (2-3): 191–212. doi:10.1007/s41130-020-00099-8.

- Shattuck, A. 2021. “Generic, Growing, Green?: The Changing Political Economy of the Global Pesticide Complex.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 48 (2): 231–253. doi:10.1080/03066150.2020.1839053.

- Smith, J. 2017. “The Global South in the Global Crisis.” Journal of Labor and Society 20 (2): 161–184. doi:10.1111/wusa.12282.

- Toensmeier, E. 2016. The Carbon Farming Solution. White River Junction, VT: Chelsea Green Publishing.

- Tomich, T. P., S. Brodt, H. Ferris, R. Galt, W. R. Horwath, E. Kebreab, J. H. J. Leveau, et al. 2011. “Agroecology: A Review from a Global-Change Perspective.” Annual Review of Environment and Resources 36 (1): 193–222. doi:10.1146/annurev-environ-012110-121302.

- Van den Berg, L., J. H. Behagel, G. Verschoor, P. Petersen, and M. Gomes da Silva. 2022. “Between Institutional Reform and Building Popular Movements: The Political Articulation of Agroecology in Brazil.” Journal of Rural Studies 89: 140–148. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2021.11.016.

- van den Bosch, R. 1978. The Pesticide Conspiracy. Garden City, NY: Doubleday.

- van der Ploeg, J. D., and S. Schneider. 2022. “Autonomy as a Politico-Economic Concept: Peasant Practices and Nested Markets.” Journal of Agrarian Change 22 (3): 529–546. doi:10.1111/joac.12482.

- Werner, M., C. Berndt, and B. Mansfield. 2022. “The Glyphosate Assemblage: Herbicides, Uneven Development, and Chemical Geographies of Ubiquity.” Annals of the American Association of Geographers 112 (1): 19–35. doi:10.1080/24694452.2021.1898322.

- Wu, S. 2021. “China Merges Sinochem, ChemChina to Create World’s Biggest Chemicals Firm.” YICAI Global, May 10.

- Zaller, J. G. 2022. Daily Poison: Pesticides – an Underestimated Danger. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing.