Abstract

Why did the far-right Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro, with financial support from Donald Trump’s US government, preside over the group recognition of around 47,000 displaced Venezuelans as refugees? It would appear implausible that a far-right, nationalistic government led by a president who had expressed visceral hostility to migrants and refugees would use the provisions of a progressive regional framework to grant refugee status to thousands of displaced people, aided by a US president whose government was literally caging child refugees. To address this question, we show that recognition of Venezuelans as refugees was grounded in an existing and credible legal and bureaucratic process managed by the Brazilian National Committee for Refugees (CONARE) that also brought to bear the influence and presence of key international actors, particularly the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). An additional crucial factor was Bolsonaro’s anti-communism, which provided a strong ideological and instrumental motivation for his government to engage with the US government of Donald Trump in its efforts to undermine the Maduro regime in Venezuela and led to the seemingly paradoxical situation of a far-right Brazilian government granting refugee status to thousands of displaced people that exceeded responses in other South American countries.

Keywords:

Introduction

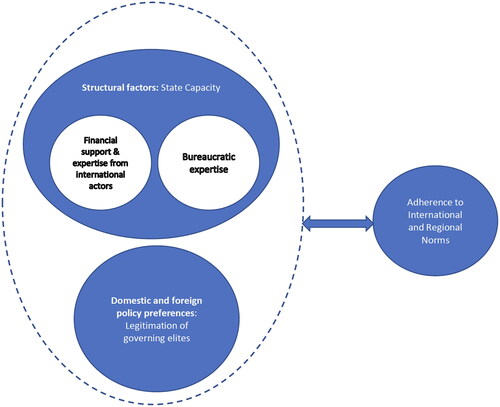

Why would a far-right, nationalistic government led by a president who had expressed visceral hostility to migrants and refugees use the provisions of a progressive regional framework to grant refugee status to thousands of displaced people? What is more, why was this seemingly progressive measure materially supported by a US president whose government was notably hostile to international refugee standards and was literally caging child refugees? More specifically, why, in 2019 and 2020, did the far-right Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro, with financial support from Donald Trump’s US government, preside over the group recognition of around 47,000 displaced Venezuelans as refugees using a simplified procedure? Our analysis focuses on the interplay between domestic and foreign policy preferences combined with structural factors that enabled international and regional norms and standards to be sources of change in Brazil. This occurred in a context where, after 2019, Bolsonaro had expressed hostility to migrants and refugees and with a bureaucratic system characterised as having ‘pockets of efficiency’ surrounded by ‘a sea of traditional clientelistic norms’ (Evans Citation1995, 61; Bersch, Praça, and Taylor Citation2017, 164–165). We argue that recognition of Venezuelans as refugees was grounded in an existing and credible legal and bureaucratic process managed by the Brazilian National Committee for Refugees (CONARE) that also brought to bear the influence and presence of key international actors, particularly the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Bolsonaro’s anti-communism was an additional crucial factor that provided a strong ideological and instrumental motivation for his government to engage with the US government of Donald Trump in its efforts to undermine the Maduro regime in Venezuela (Cintra and Cabral Citation2020; Zapata and Tapia Wenderoth Citation2022). If Bolsonaro’s anti-communism was the only explanatory factor, it would be unlikely that his government would allow similar protections for refugees from other regimes, while we show that CONARE’s influence has also been extended to refugees from other non-South American countries, albeit in smaller numbers.

We make three main contributions. First, by connecting the domestic, regional and international levels, we develop the discussion of the ‘liberal tide’ of progressive migration laws and policies in South America to show why and how liberalising measures are not necessarily dependent on liberal or left-of-centre governments (Cantor, Freier, and Gauci Citation2015). Second, we contribute to debate about the characteristics of migration governance beyond the more usual analytical focus on western liberal democracies (Natter Citation2018; Pedroza Citation2016; Adamson and Tsourapas Citation2019). Third, we move beyond a ‘liberal’ versus ‘illiberal’ dichotomy to focus on how state capacity interacts with domestic, regional and international influences that can lead, in this case, to policy liberalisation.

To begin, we outline the conceptual framework for our analysis with its focus on state capacity in the context of the interplay between domestic and foreign policy preferences. This is followed by a section that develops the broader context of Brazilian approaches to migration, asylum and refugees before we look very specifically at responses to Venezuelan displacement. To support our analysis, we draw from 24 semi-structured interviews, conducted in 2020, with 28 elite actors in the Brazilian government, bureaucracy and civil society who all played a key role in policy implementation of two main policies in the area of migration and refugee governance: refugee status determination; and, the settlement and management of Operação Acolhida (Operation Shelter). We triangulated this data with legislation, official documents and official declarations to trace the process of refugee recognition and to cross-check the interviewees’ claims.

The domestic impact of international norms and standards

Our interest is in the seemingly counter-intuitive adoption of progressive international standards by Jair Bolsonaro’s far-right, nationalistic government that ostensibly rejected international standards. Our analysis would seem to confound accounts that point to a correlation between Bolsonaro’s authoritarian style and restrictions on immigration and would also confound some of Bolsonaro’s own extreme rhetoric on migrants (Filomeno and Vicino Citation2021). In 2015, before becoming president, Bolsonaro referred to immigrants from Haiti, Senegal, Bolivia and Syria as the ‘scum of the world’. When expressing his opposition to the 2017 Migration Law, Bolsonaro stated that: ‘[immigrants’] behaviour, their culture, is completely different from ours’ and that the law would ‘open wide’ the country ‘to all sorts of people’. When speaking about Muslim and African immigrants to Europe, he said that they do not assimilate because ‘they have something inside of them that does not let their roots go’ (Filomeno and Vicino Citation2021, 605). One of his first acts upon becoming president was to withdraw Brazil from the UN’s Global Compact on Migration (GCM), stating that ‘not everyone can come into our home’ (quoted in Londoño Citation2019). He did, however, take a distinctly different tone regarding Venezuelan refugees, referring to the Venezuelan regime but also to his domestic political opponents when he said that Venezuelans ‘are fleeing a dictatorship supported by the Workers’ Party, Lula and Dilma, and we can’t leave them to their fate’ because they ‘are not merchandise or some product that can be returned’ (France24 Citation2018).

Since the onset of large-scale displacement from Venezuela after Maduro came to power in 2013 and subsequent protests in 2014, Brazil has combined the use of refugee and migratory routes as ways to increase access for Venezuelans to a regular status (Brumat Citation2022). Brazil is the only South American country to provide refugee status to large numbers of Venezuelan nationals based on the 1984 Cartagena definition of refugees and, more specifically, on the basis of a provision that goes beyond those of the Geneva Convention 1951, to protect those fleeing massive violations of human rights in Venezuela. This recognition allowed Venezuelans to access employment, health care, education and other social services without the need for an individual refugee status determination for those holding a valid ID and without a criminal record, thereby granting them permanent residence in Brazil. For the migratory route, Brazil has applied the region-wide Residence Agreement of the Common Market of the South (MERCOSUR) to Venezuelan nationalsFootnote1 providing a two-year residence permit with a simplified procedure. Strikingly, in terms of their adherence to regional norms and standards, Brazil’s actions exceeded those of South American countries with a 74% rate for ‘regularisation’ – meaning granting refugee status or a residence status – compared to a South American average of below 50%.Footnote2 The Brazilian government’s actions were lauded as ‘pragmatic, humane and sensible’ (Macklin Citation2020) and described by the UNHCR as ‘a milestone decision’ (UN News Citation2019).

These seemingly counter-intuitive developments provide a test for the diffusion of international and regional norms and standards in unpromising circumstances. Given his track record after taking office in 2018, it is implausible to argue that Bolsonaro was transformed by the effects of high office into a progressive advocate of refugee rights, particularly given the far right, neoliberal and nationalistic tendencies that have been identified during his term of office (Iamamoto, Mano, and Summa Citation2021; Nobre Citation2020). As already noted, one of his first acts as president was to withdraw Brazil from the UN GCM, while Ordinance 666 of July 2019 amended the 2017 Migration law to allow expedited deportation procedures that were strongly criticised by civil society organisations (CSOs) for breaching due process (Filomeno and Vicino Citation2021, 606).

Bolsonaro’s declarations and policy decisions allow us to rule out the possibility that granting refugee status to displaced Venezuelans occurred because of an ideological transformation by Bolsonaro or that it necessarily marked a more general liberalising tendency by his government. We have also noted that other right-wing governments in South America did not adopt this expansive interpretation of refugee status (Acosta, Blouin, and Freier Citation2019; Brumat Citation2021).

A realist reading of these events would focus on key characteristics of the Brazilian political system (presidentialism, party competition) and the material capabilities of the Brazilian state (Neto and Malamud Citation2015). We broaden this perspective to include the persistent influence of a liberalising tendency in South American migration governance that has been evident for around 20 years that has led to significant reforms of national and regional standards (Acosta Citation2018). These were associated with left-wing governments elected in the 2000s, but, even after a right-wing turn in electoral politics across South America and some retrenchment, there remain legacies of these liberal approaches across South America and a distinct regional approach in terms of both the policies that developed and the ideas that informed them. By looking at Brazil and the influence of the South American liberalising tendency, our analysis complements an emerging body of work that looks at migration, asylum and refugee policy beyond the usual relatively small group of western liberal democratic states that have tended to be the focus for analysis. Natter (Citation2018), for example, notes an ‘illiberal paradox’ whereby illiberal states can enact liberal migration policies. Natter focuses her analysis on issue-specific and regime-specific characteristics of migration policy in order to offer a more ‘global’ theorisation of migration governance. We suggest to develop this approach to think about states with ‘limited’ democracies (Gardini Citation2011) and relatively weak state capacity, which, we would argue, has relevance to a significant number of states across the world. We also connect our work to new developments in the study of ‘migration diplomacy’ that links states’ economic and security interests and their position in the international migration system to their preferences for international cooperation (Adamson and Tsourapas Citation2019).

A key issue is the translation of grand declarations such as support for refugee rights into on-the-ground realities and the significant potential for implementation gaps. This is why in our discussion we focus on the issue of state capacity, which can be understood as a state’s ability to create and maintain order, to order and regulate its territory, to generate legitimacy and to attain policy goals. We specify state capacity as the ability to regulate access by non-nationals to a migratory status, which can take different forms, including refugee status. By focusing on state capacity we differ from most studies on migration governance in South America, which analyse compliance with legal categories and affirm that implementation is deficient (Acosta and Freier Citation2015; Ceriani Cernadas and Freier Citation2015; Zapata and Tapia Wenderoth Citation2022; Cintra and Cabral Citation2020). We also complement studies that acknowledge the capacity limits in South American states to process large amounts of asylum requests, but do not explain Brazil’s distinctive policy decision (Selee et al. Citation2019; Freier and Jara Citation2020). Instead, while there can be implementation deficiencies, regularisation into a migration status (refugee or residence via the MERCOSUR provisions) can be understood as a tool for increasing control over territory and population while guaranteeing access to basic rights (Jubilut, Espinoza, and Mezzanotti Citation2021; Domenech Citation2017). Brazil’s federal system also creates a complex interplay because of the highly uneven distribution of refugee populations with particular concentrations in the north-west regions of Amazonas and Roraima and in the São Paulo conurbation.

Since democratisation in the 1980s, the Brazilian state has been seen as maintaining a relatively high degree of coercive capacity but more modest administrative capacity within ‘a semi patrimonial administration’ (Grindle Citation2012). This semi-patrimonial public administration has been prone to corruption scandals, including politicians securing kickbacks from private companies to support election campaigns (see, for example, Alencastro Citation2019). Regional and international cooperation can then develop as way to build state capacity and to bolster the legitimacy of ruling elites and their governing projects (Petersen and Schulz Citation2018). It has been argued that this cooperation is likely to depend on presidential leadership giving rise to characterisation of South American regionalism as inter-presidential (Malamud Citation2005). We argue that in South America, cooperation and adherence to international and regional norms and standards cannot be entirely explained by inter-presidentialism because, albeit in specific ways and with some elements of fragility, the institutionalisation of capacity in discrete areas can facilitate policy liberalisation in ways that cannot be reduced only to presidential leadership (Hoffmann Citation2019; Agostinis Citation2019; Perrotta Citation2012). Consistent with influential work on the domestic impacts of international norms, we highlight the ‘salience’ international norms can acquire in domestic debate and the structural context within which this debate occurs (Cortell and Davis Citation2000; Risse-Kappen Citation1994; Legro Citation1997). ‘Salience’ can be understood as ‘a durable set of attitudes towards the norm’s legitimacy in the national arena’ (Cortell and Davis Citation2000, 69).

The norms in which we are interested for both protection and refuge have been consistently present in Brazilian political discourse since the late 1990s, and informed policy development as well as the operation of CONARE that, in turn, also enabled UNHCR influence and the empowerment of civil society (Jubilut, de Oliveira Selmi, and Apolinàrio Citation2008). The seemingly paradoxical events that we analyse become less paradoxical when it is shown that under Bolsonaro the existing norms on protection and residence and their institutionalisation via CONARE enabled a government that was driven not by concern about refugees but by foreign policy interests and relations with the US government of Donald Trump. The end result was a significant impact for international norms and standards because of the interaction between Bolsonaro’s efforts to legitimate his governing project through domestic links to the military and internationally to the US combined with extant state capacity in the specific area of refugee rights and protection.

Brazil has played a leading role in South American regionalism within MERCOSUR but also within other regional organisations such as the failed attempt by the Brazilian left when in power to build a progressive form of South American regionalism in the form of the Union of South American Nations (UNASUR) that floundered as the region took a rightward political turn after 2016 (Sanahuja Citation2012; Serbin Citation2009). This leading role was particularly salient in the area of asylum and refugee governance (Jubilut Citation2006). Significantly, as soon as he came to office, Bolsonaro effectively reversed Brazilian engagement with the South American region causing ‘deepened regional fragmentation’ and pursued ‘a unilateral and solitary international role’ as the ‘Trump of the tropics’ (Vadell and Giaccaglia Citation2021, 28, 41; Setzler Citation2021; Ramanzini Junior, Mariano, and Gonçalves Citation2022).

illustrates our argument. The regularisation of Venezuelan nationals was motivated by domestic and foreign policy preferences including Bolsonaro’s opposition to the Venezuelan regime that also attracted support from the Trump administration. While opposition to the Venezuelan regime also motivated the adoption of regularisation processes for Venezuelans in other South American countries with right-wing governments, such as Chile, Colombia, Ecuador and Peru, the Brazilian case is distinct because Brazil offers both MERCOSUR and Cartagena paths to a status in Brazil for Venezuelans. As we show in the empirical section below, Brazil has been able to adopt this dual regularisation path because of structural factors including established bureaucratic expertise for the recognition and protection of refugees, which has been aided by international (UNHCR) and civil society actors. This process enabled the salience of regional and international norms and standards in both domestic debate and in bureaucratic procedures.

Figure 1. Adherence to regional and international norms and standards. Source: Authors’ elaboration.

In addition, Brazil has another distinctive policy that has been adopted as a way of increasing capacity to deal with the arrival of Venezuelans in its poorer Northern border regions (Jarochinski Silva and Fontenele de Albuquerque Citation2021). Operation Shelter is a large-scale, multi-actor operation aimed at receiving, sheltering, and ‘interiorising’ or ‘relocating’ Venezuelan migrants and refugees to other parts of Brazil (see Casa Civil Citation2021). Brazil is the only South American country that has developed such a large and complex operation at its border. Framed as a ‘humanitarian’ operation and led by the military (Jarochinski Silva and Fontenele de Albuquerque Citation2021), Operation Shelter is a venue for obtaining international funds from international organisations and from the USA.

Migration governance in Brazil

Region-wide migration norms for protection and residence that have been present in South American political discourse since the late 1990s were included in governance frameworks as part of a distinctly progressive turn in South American migration policies that was closely associated with a resurgence in regionalism (Acosta Citation2018; Geddes et al. Citation2019; Cantor, Freier, and Gauci Citation2015). Left-wing governments across the region were seen as advancing ‘post-neoliberal’ or ‘post-hegemonic’ regionalism (Sanahuja Citation2012; Riggirozzi and Tussie Citation2012) as a way to advance ‘domestic growth, equity and regional governance … bringing the regulation of socio-economic activities back to the state’ (Margheritis Citation2016, 58). A ‘liberal tide’ of migration laws across the region ushered in a new approach and policies that proclaimed the right to migrate and disavowed the criminalisation of migration (Cantor, Freier, and Gauci Citation2015; Acosta Citation2018). At the regional level, the MERCOSUR Residence Agreement of 2002 established a right to residence and access to a wide set of rights for the nationals of most South American countries. This progressive turn in migration policies in South America was consciously designed in opposition to the restrictive policies and approaches that were being developed in the USA and Europe (Brumat and Freier Citation2021). Regional cooperation has helped to bolster domestic governing agendas, but cooperation has also been shaped by the extent to which there are shared ideas about the role and relevance of the region (Petersen and Schulz Citation2018, 103).

Brazil’s migration and refugee legislation has been characterised as liberal, open and progressive and is strongly influenced by regional norms, standards and policies (Freier Citation2015; Fischel de Andrade Citation2015; Acosta Citation2018). The National Constitution of 1988 enshrines the principle of equal rights between national and foreign residents (Presidência da República Citation1988, article 5) and promotes the ‘economic, political, social and cultural integration of the Latin American peoples’ (article 4).

Brazil became a pioneer and a model for other Latin American countries when in 1997 it adopted Law 9474/97 that defined the rights and provisions for refugees and asylum seekers with a definition of refugee that is broader than the 1951 Convention; it is narrower than the Cartagena definition but does include ‘a gross and generalized violation of human rights’ as a reason for seeking refugee status (Presidência da Republica Citation1997, article 1). CONARE was created by the 1997 Refugee Law as an inter-ministerial and inter-institutional body with both operational and policy roles to: determine refugee eligibility; promote refugee-related public policies; design and evaluate resettlement activities; and regulate the legal framework for asylum in Brazil (Presidência da Republica Citation1997, article 12). Organisationally, it is linked to the Ministry of Justice and Public Security and comprises representatives of the ministries of Justice and Public Security (chair), Foreign Affairs (vice chair), Health and Education plus the Federal Police department and CSOs. Each of these members has one vote. UNHCR and the Office of the Public Defender of the Union have a seat and voice but no vote. CONARE has been praised by UNHCR for its inclusion of civil society and also built on the provisions of the 1997 legislation, including in relation to protection for family members beyond a refugee’s legal companion and under-aged children eligible for refugee status to also include parents and under-aged orphan siblings, grandchildren, great-grandchildren, nephews and nieces. This meant that CONARE went beyond the requirements of the 1951 refugee convention to promote a broader understanding of the right to family life (Nogueira and Marques Citation2008). CONARE is more than an implementing authority because its competences go ‘beyond eligibility determination’ to encompass various actions for enhancing refugee protection, assistance, legal support and durable solutions (Fischel de Andrade Citation2015, 170). The active participation of civil society also distinguishes Brazil from other South American countries that do not have this provision in their national refugee laws.

UNHCR and CSOs, in particular CSOs linked to the Catholic Church, have played an important role in the refugee recognition process. Before CONARE’s creation, decisions on refugee recognition were based on analysis, assessment and the legal opinion of UNHCR, which collaborated closely with CSOs, which, at the same time, were responsible for assisting and orienting asylum seekers to create a ‘very strong bond’ (Jubilut, de Oliveira Selmi, and Apolinàrio Citation2008, 30–31). During the democratic transition of the 1990s, the Brazilian state sought international legitimation, which has been seen to explain the high reliance on UNHCR’s expertise and judgement (Jubilut, de Oliveira Selmi, and Apolinàrio Citation2008, 30). UNHCR has also heavily relied on CSOs (Granato Santos and Lima de Azevedo Citation2015). CONARE’s creation in 1997 was influenced by these previous developments and its institutional configuration gave a ‘supervisory role’ to UNHCR and, in practice, a key role in the reception, advising and initial processing of asylum requests to CSOs, something that usually would be done by the Federal Police (Jubilut, de Oliveira Selmi, and Apolinàrio Citation2008, 31; Granato Santos and Lima de Azevedo Citation2015). This led to the refugee recognition process being a ‘tripartite enterprise’ involving the state, International Organisations (IOs) and civil society. Significantly, CONARE is the only South American national refugee council that relies on this tripartite procedure (Granato Santos and Lima de Azevedo Citation2015). As such, and to return to a point made earlier, CONARE’s institutional configuration actively enables the domestic salience of international norms and procedures that can be understood as indicative of a durable set of attitudes towards the norm’s legitimacy in the national arena (Cortell and Davis Citation2000).

Brazil’s new migration law of 2017 (Law 13445/17) was in line with the liberal approach of other South American countries and resulted from a participatory process with a very strong human rights focus (Marques de Oliveira and Sampaio Citation2020). Its guiding principles included non-discrimination, family reunion, equal treatment, social and labour integration of immigrants, equal access to public services independently of the nationality and migratory status of the person, and equal access to justice (Presidência da República 2017). The law prioritised and promoted respect for international and regional law, principles and agreements and international cooperation on migration (articles 2, 3, 46, 47, 111). Crucially, the law called for strengthened Latin American regional integration and the free movement of people (Article 3.XIV). However, former President Temer vetoed 20 of the most progressive articles of the law and adopted an implementing decree that has been characterised as ‘extremely conservative’ because it uses terminology such as ‘clandestine immigrant’ (Presidência da Republica Citation2017, article 172), allows the detention of irregular immigrants and hinders family reunion (Zapata and Fazito Citation2018, 235–236). While this vetoing of the most progressive measures was seen as a step back in the liberalisation of Brazilian migration policy, the law generally was viewed as an advance in Brazilian migration governance and protection of migrants’ rights (Ribeiro de Oliveira Citation2017).

Restrictive shifts in Brazilian migration policy have been linked to the re-emergence of ‘securitist actors’ within Brazil’s bureaucracy in the mid-2010s who proposed and endorsed policy proposals focused on detaining and deporting irregular immigrants, selecting immigrants, militarising borders and resisting policy liberalisation (Brumat and Espinoza forthcoming). These ‘securitist’ actors include the Casa Civil or Executive Office, led by the ‘Chief of Staff’, the most senior aide to the president, the Ministry of Defence, the Gabinete of Segurança Institucional and the Federal Police, which institutionally belongs to the Ministry of Justice (functioning as the Interior Ministry in Brazil). These actors were crucial to President Temer’s vetoes of the more progressive aspects of Law 13445/17 and its regulation (Ribeiro de Oliveira Citation2017).

These developments after 2016 would appear to be consistent with a rightwards shift even prior to Bolsonaro’s election that would also appear to be inconsistent with large-scale group-based recognition of refugee status for displaced Venezuelans. Before the mass displacement caused by the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Venezuela was the world’s leading producer of displaced people. By mid-2022, an estimated 6.8 million Venezuelan nationals lived out of their country of origin, with the vast majority, around 74%, in another South American country.Footnote3 Brazil is the fifth-largest recipient of Venezuelan migrants and refugees in the world, with 261,000 registered Venezuelan nationals in 2021, but is the second-largest recipient of asylum requests in South America after Peru, with around 90,000 pending asylum requests (R4V Citation2021). According to official sources, in 2020, 90% of all asylum requests in Brazil were registered in its Northern region, mostly in the poor state of Roraima, and the vast majority of these (around 43,000) were made by Venezuelan nationals (Silva et al. Citation2021, 18). The second-highest receiving state was Amazonas with 6500 requests, followed by São Paulo and the Federal District, Brasilia, which received 8.5% and 6.6%, respectively, of all asylum requests made in 2020 (Silva et al. Citation2021, 18). While São Paulo and Brasilia have large infrastructures and developed state bureaucracies, Roraima has very limited capacities and is relatively isolated from the rest of the Federation with an economic structure that is heavily reliant on the public sector (Fundação Getulio Vargas Citation2020). The limited capacities of the Roraima state, the main receiving state of Venezuelan nationals in Brazil, were reasons for the creation of ‘Operation Shelter’ for the regularisation of Venezuelan nationals.

Since the onset of large-scale Venezuelan displacement after 2011, the main basis for refugee recognition in Brazil has been the extended definition provided by the Cartagena Declaration. In that period, most asylum seekers were recognised as refugees based on a ‘gross and generalized violation of human rights’, meaning on the basis of the Cartagena definition, and this recognition mostly applied to Venezuelans (44,663 persons, representing 92.8% of the total of refugees recognised under this provision) (Silva et al. Citation2021, 44). Between 2011 and 2021, no asylum applicants from Venezuela were rejected (Silva et al. Citation2021). shows that for the period covered by this article, the majority of asylum applicants in Brazil were Venezuelan nationals (65% of total asylum requests in 2019 and 60% in 2020). also shows that the total number of approved asylum applications was higher in 2020 than in 2019 (53,583 in 2020 against 28,702 in 2019). This is explained by the group recognition of Venezuelan nationals, which affected asylum seekers whose requests had accumulated in the preceding years. In 2019 and 2020, most approved asylum requests benefitted Venezuelan nationals (almost 73% of the total approved requests in 2019 and almost 87% in 2020).

Table 1. Refugee recognition in Brazil (2019–2020).

Protection of displaced Venezuelans

We have shown that norms regarding protection and residence have been present in Brazil since at least the late 1990s, were institutionalised in legislation, and became part of the standard operating practices of the asylum and refugee system, and that a key role was played by CONARE that also enabled UNHCR and engagement with CSOs. Yet these factors alone would not seem to explain why a far-right nationalist such as Bolsonaro would grant refugee status to thousands of Venezuelans. To explain why this occurred we develop our account to show how, after 2019, foreign policy considerations were a key factor in the Bolsonaro government’s granting of refugee status to displaced Venezuelans with material US support from the Trump administration.

The Venezuelan crisis led to an exponential growth of asylum requests in Brazil, increasing from a total of 16,982 between 2011 and 2014 (Cavalcanti et al. Citation2015) to 82,552 total requests in 2019 alone (see ), representing a 5635% increase in asylum requests in eight years (Silva et al. Citation2020, 11). CONARE did not have the capacity to process such a large number of requests (Moulin Aguiar and Magalhães Citation2020, 9; Zapata and Tapia Wenderoth Citation2022, 10). Two measures were taken to address this lack of capacity. First, in March 2017, the MERCOSUR Residence Agreement was applied to Venezuelan nationals through Resolution 126 of the National Council of Immigration (CNIg), which was later extended via Presidential Decree no. 9285/2018 (Cintra and Cabral Citation2020, 129–130). Importantly, this decree, issued by right-wing President Temer, recognised a situation of humanitarian crisis in Venezuela (Presidência da Republica Citation2018). This was later to provide a basis for the Bolsonaro governments’ group-based recognition of Venezuelan nationals using the Cartagena definition. This was done in June 2019 in the CONARE Technical note no. 3.Footnote4 As stated by a CONARE member: ‘In CONARE we have the political reading of the government regarding the situation in Venezuela, which allowed us to say ‘yes, there is a generalised violation of human rights [in Venezuela]’ (interview with Brazilian government official, February 2021, emphasis added).

During the Bolsonaro presidency, this ‘political reading’ took the form of an extremely strong opposition to the Maduro regime. This can be seen in the declarations of Bolsonaro’s former Minister of Foreign Affairs, who described the human rights situation in Venezuela as ‘devastating’ (Araújo Citation2020b), called the Maduro regime ‘the worst dictatorship in the world’, linked it to transnational organised crime (Araújo Citation2019b, Citation2020a) and to ‘generalised misery, lies and oppression’ (Araújo Citation2019a). According to this interpretation of the situation in Venezuela, the rest of South America are ‘solidary neighbours’ (Araújo Citation2019b), which then justifies the adoption of relatively liberal policy responses to Venezuelan displacement.

When Bolsonaro took office, foreign policy concerns powerfully motivated responses to Venezuelan displacement, particularly relations with the Trump administration. The two leaders shared a visceral dislike of Maduro’s Venezuelan regime. In some of their joint statements, they expressed their agreement on the Venezuelan situation and its potential solution, which they argued should be support for the opposition leader Juan Guaidó (US Embassy in Brazil Citation2020). By May 2019, all three branches of the Brazilian military were present at the border to provide assistance through Operation Shelter. As a UN spokesman put it: ‘It’s rare for the UN to work so closely with the military, but, in this case, it’s working. I mean you can look around you – it’s amazingly well-organised’ (quoted in Shenoy Citation2019). Between 2017 and 2019, the US provided $46 million to support displaced Venezuelans including US support for the International Organisation for Migration (IOM)-administered ‘Economic Integration of Vulnerable Nationals from Venezuela in Brazil Program’ (USAID Citation2020). As the US Embassy in Brazil put it: ‘The United States appreciates the generosity of the Government of President Jair Bolsonaro and the Brazilian people as they have hosted tens of thousands of Venezuelan refugees who have escaped the regime-driven political and economic crisis chaos in their home country’ (USAID Citation2020). The Trump administration demonstrated its interest in the Brazilian response to Venezuelan displacement very explicitly. In September 2019, US former Secretary of State Mike Pompeo visited Boa Vista, the capital of Roraima state. During that visit, he went to some of the ‘abrigos’ or shelters where newly arrived Venezuelans were hosted, where he described the Maduro regime as a dictatorship and linked it to transnational crime (DW Citation2020). Key implementing actors acknowledged that international funding played a crucial role in increasing the capacities of the Brazilian response to Venezuelan displacement:

The truth is that the city of Boa Vista has greatly benefitted from the foreign resources that arrived … we were asked to take ambassadors and other foreign missions to Boa Vista because it [Operation Shelter] generated great international interest. I used to go to Boa Vista two or three times a month, to assist [these foreign] missions, and they resulted in donations. So we had donations from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), who was very active in the Brazil-Venezuela border […]. Especially Japan, the European Union … and many others, a lot of people donated, from small things to bigger things, but there was a lot [of international funding]. Even UNHCR called for an international donation, and it was quite successful. (Interview with Brazilian government official, July 2021)

I think that a very positive point of making a prima facie recognition is that the process of recognition of Venezuelans is not that dependent on an individual interview. We cross reference data and we make a general recognition of Venezuelans. This is what allows us to make many recognitions simultaneously because the truth is, we did not have the structure to interview so many Venezuelans in this context. (official of Brazil, January 2021)

… with the Venezuelans, the adoption of this concept [of refugees based on the Cartagena definition] was the result of a long-term, enormous work of UNHCR and the civil society, together with the Ombudsman. I think that we worked for almost a year to recognise Venezuelans. We argued, we insisted, we showed the motivations and analyses …. We have consistently taken these arguments to the government, so that they would accept the serious and generalised human rights violation for Venezuelans. It was, for me, a triumph, which the government resisted at the beginning, but we finally managed to get. (CSO representative, December 2020)

It was a question of modernising the refugee system, simply because, even before Venezuelans, we already had a great number of requests from different parts of the world … So when we started receiving a great influx of Venezuelans, we already had the concern of modernising [the system] which allowed us to reach a consensus. So we had a plan of technical, technological and administrative development with the intention of creating a more responsive system, which could effectively analyse all the requests and avoid the backlog of cases that we were unable to address. […] Given that the Federal Police is part of the CONARE, they [the Federal Police] have the databases and they can cross-check the data, because that is something that they do in other areas as well, when they are fighting organised crime, you know? There is a technology of information against organised crime and other illegal activities, that was highly developed in Brazil and now it was applied to identify very clear cases of [political] persecution …. A small but highly relevant detail is the development of SiSCONARE, the digitalised system, which allowed us to make progress in a debate about the necessity of an individual interview for asylum requests. And it was much easier to advance in the discussion in the cases where there is an asylum request which is obviously positive, such as Venezuelans. This means that it is not necessary to interview individually all this group of persons. Because Cartagena already gives us a path. So, all these debates are materialised in the resolution that allowed the right to make group decisions, based on the proposal by the Federal Police and the Ministry of Justice of cross-checking the data and excluding the cases where a deeper investigation is necessary. (official of Brazil, February 2021, emphasis added)

The fact that non-discrimination is in the Constitution, in the [2017] Migration Law, I think that is a great beginning so that these persons have access to all the existing policies. I wouldn’t leave out the power and the force that [those principles] have because they are consolidated in Brazilian legislation. So, this is where all our discourse begins, all of our practices, in terms of ‘protection’. The simple fact of talking about a person having the same rights to protection as a Brazilian is … it is very strong. (official of Brazil, February 2021)

Conclusions

This paper seeks to account for the seemingly counter-intuitive outcome of a far-right anti-migrant/refugee government in Brazil extending protection to displaced people, that confounds our expectation for the actions of such a government and that also had the effect of, ostensibly at least, making Bolsonaro appear to be a regional leader on refugee protection. One explanation for this could be that it is possible that illiberal states can do liberal things. Our account has sought to move away from a liberal–illiberal dichotomy and, instead, to explore the impact of domestic and international factors on state capacity. By doing so, we seek to account for developments in Brazil, but, by highlighting the influence of limits to democratic politics and to state capacity, we would argue that our findings have implications for a much wider population of states that fall into what has been called a ‘middle quality institutional trap’ (Mazzuca and Munck Citation2020) and also for the governance of issue areas other than migration. We showed how migration and refugee issues became salient in Brazilian domestic politics from the late 1990s and how developments in Brazil were consistent with what has been referred to as a ‘liberal tide’ of progressive pro-migration laws and practices. We also showed how a pocket of efficiency within the Brazilian state that was associated with the work of CONARE served as a basis for the inclusion of CSOs and influence from international actors, particularly UNHCR. CONARE provides an example of a relatively strong system with a tripartite structure that allows the participation of international organisations such as the UNHCR and CSOs, which has facilitated the protection of rights since its creation in 1997. This is not to claim that protection issues in Brazil are resolved, because there remain protection and implementation gaps, but our analysis contributes to the assessment of factors that can influence the development of relatively progressive protection systems for asylum-seekers and refugees in circumstances where state capacity is constrained.

Crucial to our account during the Bolsonaro government after 2018 was also the role of the US with a stridently anti-migration regime under Trump providing financial aid to a fellow anti-migration political leader to offer protection to Venezuelan refugees. The key factor here was their shared visceral opposition to the Venezuelan regime. More broadly, we have sought to demonstrate how adherence to international norms and standards needs to be understood in the context of the ways in which domestic governing projects seek legitimation but also the crucial role played by state capacity which, as we have shown, was relatively well developed for refugee protection and provided a route for the incorporation of international – and regional – norms and standards that pre-dated Bolsonaro’s time in office.

Ethical approval

Research involving human subjects (national policymakers) obtained ethics approval on 17/07/2019 Ref. Ares(2019)4429409.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Leiza Brumat

Leiza Brumat is Senior Research Fellow at Eurac Research (Bolzano, Italy) where she works on her project ‘Policy Implementation in Global South Regionalism: Multilevel Migration Governance in South America (POLIM)’, funded by the Province of Bolzano/Bozen; and an Associated Research Fellow at the United Nations University – Institute for Comparative Regional Integration Studies (UNU-CRIS). She obtained her PhD in Flacso, Argentina. She previously worked as a research fellow at the Migration Policy Centre (MPC) of the European University Institute, as Lecturer in international relations and regional integration in Buenos Aires, and as a research fellow for the National Council of Scientific and Technical Research (CONICET) of Argentina. She is the co-author of Migration and Mobility in the EU (2nd edition, Palgrave, 2020, with Andrew Geddes and Leila Hadj Abdou). Her research focuses on regional and global migration governance.

Andrew Geddes

Andrew Geddes is Professor of Migration Studies and Director of the Migration Policy Centre at the European University Institute, Florence, Italy. Between 2014 and 2019, he was awarded an Advanced Investigator Grant by the European Research Council for a project on the drivers of global migration governance in Europe, North America, South America and Southeast Asia. He has published extensively on global migration, with a particular focus on policymaking, the politics of migration and regional cooperation and integration. Recent publications include The Dynamics of Regional Migration Governance (edited with Marcia Vera Espinoza, Leila Hadj-Abdou and Leiza Brumat; Edward Elgar, 2019) and Governing Migration Beyond the State: Europe, North America, South America and Southeast Asia in a Global Context (Oxford University Press, 2021).

Notes

1 As Venezuela has not ratified the Residence Agreement of Mercosur, Brazil applies the Agreement’s main provisions to Venezuelan nationals through lower-level legislation (see Zapata and Tapia Wenderoth Citation2022).

2 Authors’ calculations based on data from the Inter-Agency Coordination Platform for Refugees and Migrants from Venezuela, https://www.r4v.info/en/data.

3 Authors’ calculation based on data from the Inter-Agency Coordination Platform for Refugees and Migrants from Venezuela, https://www.r4v.info/en/data

4 Ministério da Justiça e Segurança Pública. Nota Técnica nº3/2019/CONARE_Administrativo/CONARE/DEMIG/SENAJUS/MJ. Processo nº 08018.001832/2018-01. Estudo de País de Origem – Venezuela, Brasília: 2019,

6 Two members of CONARE confirmed this (interviews in December 2020 and January 2021).

8 Declaración de los Estados Partes del Mercosur sobre la República Bolivariana de Venezuela -Buenos Aires, 1 de abril de 2017’, Ministério das Relações Exteriores, April 1, 2017, http://www.itamaraty.gov.br/es/notas-a-la-prensa/17907-declaracion-de-los-estados-partes-del-mercosur-sobre-la-republica-bolivariana-de-venezuela-buenos-aires-1-de-abril-de-2017.

Bibliography

- Acosta, D. 2018. The National versus the Foreigner in South America. 200 Years of Migration and Citizenship Law. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Acosta, D., C. Blouin, and L. F. Freier. 2019. “La emigración venezolana: respuestas latinoamericanas.” 3 (2a época). Documento de Trabajo. Madrid: Fundación Carolina.

- Acosta, D., and L. F. Freier. 2015. “Turning the Immigration Policy Paradox Upside down? Populist Liberalism and Discursive Gaps in South America.” International Migration Review 49 (3): 659–696. doi:10.1111/imre.12146.

- Acosta, D., and L. Madrid. 2020. “¿Migrantes o refugiados? La Declaración de Cartagena y los venezolanos en Brasil.” Análisis Carolina n.9/2020. n.9/2020. doi:10.33960/AC_09.2020.

- Adamson, F. B., and G. Tsourapas. 2019. “Migration Diplomacy in World Politics.” International Studies Perspectives 20 (2): 113–128. doi:10.1093/isp/eky015.

- Agostinis, G. 2019. “Regional Intergovernmental Organizations as Catalysts for Transnational Policy Diffusion: The Case of UNASUR Health.” JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 57 (5): 1111–1129. doi:10.1111/jcms.12875.

- Alencastro, M. 2019. “Brazilian Corruption Overseas: The Case of Odebrecht in Angola.” In Corruption in Latin America: How Politicians and Corporations Steal from Citizens, edited by R. I. Rotberg, 109–123. Cham: Springer International Publishing. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-94057-1_5.

- Araújo, E. 2019a. “O “Socialismo do Século XXI”, representado por Maduro na Venezuela, está ruindo…” @ernestofaraujo. Twitter. 5 February 2019. https://twitter.com/ernestofaraujo/status/1092788962450702336

- Araújo, E. 2019b. “Para os venezuelanos e demais sul-americanos, a pior ditadura do mundo é a de Maduro na Venezuela…” @ernestofaraujo. Twitter. 26 February 2019. https://twitter.com/ernestofaraujo/status/1100454102272786432

- Araújo, E. 2020a. “O regime de Maduro promoveu hoje “eleições parlamentares” na Venezuela para tentar legitimar-se…” @ernestofaraujo. Twitter. 1 January 2020. https://twitter.com/ernestofaraujo/status/1335782410554908673

- Araújo, E. 2020b. “Relatório do Cons. de Direitos Humanos da ONU sobre a Venezuela é devastador…” @ernestofaraujo. Twitter. 1 January 2020. https://twitter.com/ernestofaraujo/status/1306616503404564483

- Bersch, K., S. Praça, and M. M. Taylor. 2017. “State Capacity, Bureaucratic Politicization, and Corruption in the Brazilian State.” Governance 30 (1): 105–124. doi:10.1111/gove.12196.

- Brumat, L. 2021. “Gobernanza migratoria en Suramérica en 2021: respuestas a la emigración venezolana durante la pandemia.” Análisis Carolina n.12/2021. http://webcarol.local/gobernanza-migratoria-en-suramerica-en-2021-respuestas-a-la-emigracion-venezolana-durante-la-pandemia/ doi:10.33960/AC_12.2021.

- Brumat, L. 2022. “Migrants or Refugees? “Let’s Do Both”. Brazil’s Response to Venezuelan Displacement Challenges Legal Definitions.” MPC Blog (blog), 11 January 2022. https://blogs.eui.eu/migrationpolicycentre/migrants-or-refugees-lets-do-both-brazils-response-to-venezuelan-displacement-challenges-legal-definitions/

- Brumat, L., and M. V. Espinoza. Forthcoming. “Actors, Ideas, and International Influence: Understanding Migration Policy Change in South America.” International Migration Review.

- Brumat, L., and L. F. Freier. 2021. “Unpacking the Unintended Consequences of European Migration Governance: The Case of South American Migration Policy Liberalisation.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, doi:10.1080/1369183X.2021.1999223.

- Cantor, D., L. Freier, and J.-P. Gauci, eds. 2015. A Liberal Tide?: Immigration and Asylum Law and Policy in Latin America. London: Institute of Latin American Studies.

- Casa Civil. 2021. “Sobre a Operação Acolhida.” Gov.Br Presidencia da República. https://www.gov.br/casacivil/pt-br/acolhida/sobre-a-operacao-acolhida-2/sobre-a-operacao-acolhida-1

- Cavalcanti, L., A. Tadeu de Oliveira, T. Tonati, and S. A. Dutra. 2015. “A Inserção Dos Imigrantes No Mercado de Trabalho Brasileiro. Relatório Anual 2015.” Brasilia: Observatório das Migrações Internacionais; Ministério do Trabalho e Previdência Social/Conselho Nacional de Imigração e Coordenação Geral de Imigração. http://portal.mte.gov.br/obmigra/home.htm

- Ceriani Cernadas, P., and L. F. Freier. 2015. “Migration Policies and Policymaking in Latin America and the Caribbean: Lights and Shadows in a Region in Transition.” In A Liberal Tide? Immigration and Asylum Law and Policy in Latin America, edited by D. Cantor, L. F. Freier, and J.-P. Gauci, 33–56. School of Latin American Studies: University of London.

- Cintra, d. O. T., and V. P. Cabral. 2020. “The Application of the Cartagena Declaration on Refugees to Venezuelans in Brazil: An Analysis of the Decision-Making Process by the National Committee for Refugees.” Latin American Law Review 05 (5): 121–137. doi:10.29263/lar05.2020.06.

- Cortell, A. P., and J. W. Davis, Jr. 2000. “Understanding the Domestic Impact of International Norms: A Research Agenda.” International Studies Review 2 (1): 65–87. doi:10.1111/1521-9488.00184.

- Domenech, E. 2017. “Las políticas de migración en Sudamérica. Elementos Para el análisis crítico del control migratorio y fronterizo.” Terceiro Milênio: Revista Crítica de Sociologia e Política 8 (1): 19–48.

- DW. 2020. “Em Roraima, Pompeo faz discurso linha-dura contra Maduro – DW – 19/09/2020.” dw.com, 19 September 2020. https://www.dw.com/pt-br/em-roraima-pompeo-faz-discurso-linha-dura-contra-maduro/a-54984194

- Evans, P. 1995. Embedded Autonomy: States and Industrial Transformation. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press. https://press.princeton.edu/books/paperback/9780691037363/embedded-autonomy

- Filomeno, F. A., and T. J. Vicino. 2021. “The Evolution of Authoritarianism and Restrictionism in Brazilian Immigration Policy: Jair Bolsonaro in Historical Perspective.” Bulletin of Latin American Research 40(4): 598–612. doi:10.1111/blar.13166.

- Fischel de Andrade, H. J. 2015. “Refugee Protection in Brazil (1921-2014): An Analytical Narrative of Changing Policies.” In A Liberal Tide? Immigration and Asylum Law and Policy in Latin America, edited by D. J. Cantor, L. F. Freier, and J.-P. Gauci, 153–183. London: Institute of Latin American Studies.

- France24. 2018. “Brazil’s Bolsonaro Rules out Sending Back Venezuelan Migrants.” https://www.france24.com/en/20181124-brazils-bolsonaro-rules-out-sending-back-venezuelan-migrants

- Freier, L. F. 2015. “A Liberal Paradigm Shift?: A Critical Appraisal of Recent Trends in Latin American Asylum Legislation.” In Exploring the Boundaries of Refugee Law: Current Protection Challenges, edited by Jean-Pierre Gauci, Mariagiulia Giuffré and Evangelina Tsourdi, 118–145. doi:10.1163/9789004265585_007.

- Freier, L. F., and S. C. Jara. 2020. “Regional Responses to Venezuela’s Mass Population Displacement.” E-International Relations (blog), 16 September 2020. https://www.e-ir.info/2020/09/16/regional-responses-to-venezuelas-mass-population-displacement/

- Fundação Getulio Vargas. 2020. A Economia de Roraima e o Fluxo Venezuelano [Recurso Eletrônico] : Evidências e Subsídios Para Políticas Públicas. Rio de Janeiro: FGV DAPP. https://hdl.handle.net/10438/29097

- Gardini, G. L. 2011. “MERCOSUR: What You See Is Not (Always) What You Get.” European Law Journal 17 (5): 683–700. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0386.2011.00573.x.

- Geddes, A., L. H. Abdou, M. V. Espinoza, and L. Brumat. 2019. The Dynamics of Regional Migration Governance. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Granato Santos, R., and N. Lima de Azevedo. 2015. “Los obstáculos y desafíos de las solicitudes de refugio en Brasil.” Revista IIDH (62): 147–166.

- Grindle, M. S. 2012. Jobs for the Boys: Patronage and the State in Comparative Perspective. Jobs for the Boys. Cambridge (Mass.): Harvard University Press. doi:10.4159/harvard.9780674065185.

- Hoffmann, A. M. 2019. Regional Governance and Policy-Making in South America. Cham: Springer International Publishing. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-98068-3.

- Iamamoto, S. A. S., M. K. Mano, and R. Summa. 2021. “Brazilian Far-Right Neoliberal Nationalism: Family, Anti-Communism and the Myth of Racial Democracy.” Globalizations, 1–17. doi:10.1080/14747731.2021.1991745.

- Jarochinski Silva, J. C., and É. B. Fontenele de Albuquerque. 2021. “Operação Acolhida: Avanços e Desafios.” Refugio, Migrações e Cidadania. Caderno de Debates 16 (16): 47–72.

- Jubilut, L. L. 2006. “Refugee Law and Protection in Brazil: A Model in South America?” Journal of Refugee Studies 19 (1): 22–44. doi:10.1093/jrs/fej006.

- Jubilut, L. L., M. de Oliveira Selmi, and S. Apolinàrio. 2008. “Refugee Status Determination in Brazil: A Tripartite Enterprise | Refuge: Canada’s Journal on Refugees.” Refuge: Canada’s Journal on Refugees 25 (2): 29–40. doi:10.25071/1920-7336.26029.

- Jubilut, L. L., M. V. Espinoza, and G. Mezzanotti, eds. 2021. Latin America and Refugee Protection. Regimes, Logics and Challenges. New York: Berghahn Books.

- Legro, J. W. 1997. “Which Norms Matter? Revisiting the “Failure” of Internationalism.” International Organization 51 (1): 31–63. doi:10.1162/002081897550294.

- Londoño, E. 2019. “Bolsonaro Pulls Brazil From U.N. Migration Accord.” The New York Times, 9 January 2019, sec. World. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/01/09/world/americas/bolsonaro-brazil-migration-accord.html

- Macklin, A. 2020. “Brazil’s Humane Refugee Policies: Good Ideas Can Travel North.” The Conversation. http://theconversation.com/brazils-humane-refugee-policies-good-ideas-can-travel-north-130749

- Malamud, A. 2005. “Presidential Diplomacy and the Institutional Underpinnings of Mercosur: An Empirical Examination.” Latin American Research Review 40 (1): 138–164. doi:10.1353/lar.2005.0004.

- Margheritis, A. 2016. Migration Governance across Regions: State-Diaspora Relations in the Latin America-Southern Europe Corridor. London: Routledge.

- Marques de Oliveira, E. M., and C. Sampaio. 2020. Estrangeiro, Nunca Mais! Migrante Como Sujeto de Direito e a Importância Do Advocacy Pela Nova Lei de Migração Brasileira. São Paulo: Centro de Estúdos Migratórios.

- Mazzuca, S., and G. Munck. 2020. A Middle Quality Institutional Trap: Democracy and State Capacity in Latin America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Moulin Aguiar, C., and B. Magalhães. 2020. “Operation Shelter as Humanitarian Infrastructure: Material and Normative Renderings of Venezuelan Migration in Brazil.” Citizenship Studies 24 (5): 642–662. doi:10.1080/13621025.2020.1784643.

- Natter, K. 2018. “Rethinking Immigration Policy Theory beyond “Western Liberal Democracies.” Comparative Migration Studies 6 (1): 4. doi:10.1186/s40878-018-0071-9.

- Neto, O. A., and A. Malamud. 2015. “What Determines Foreign Policy in Latin America? Systemic versus Domestic Factors in Argentina, Brazil, and Mexico, 1946–2008.” Latin American Politics and Society 57 (4): 1–27. doi:10.1111/j.1548-2456.2015.00286.x.

- Nobre, M. 2020. Ponto-final: A guerra de Bolsonaro contra a democracia. São Paulo: Todavia.

- Nogueira, M. B., and C. C. Marques. 2008. “Brazil: Ten Years of Refugee Protection.” Forced Migration Review 30 (April): 57–58.

- Pedroza, L. 2016. “Innovations Rising from the South? Three Books on Latin America’s Migration Policy Trajectories.” Migration Studies 5 (1): mnw018. doi:10.1093/migration/mnw018.

- Perrotta, D. 2012. “¿Realidades presentes – conceptos ausentes? La relación entre los niveles nacional y regional en la construcción de políticas de educación superior en el MERCOSUR.” Integración y Conocimiento 1 (June): 4–17.

- Petersen, M., and C.-A. Schulz. 2018. “Setting the Regional Agenda: A Critique of Posthegemonic Regionalism.” Latin American Politics and Society 60 (1): 102–127. doi:10.1017/lap.2017.4.

- Presidência da República. 1988. “Constituição Da República Federativa Do Brasil de 1988.” http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/constituicao/constituicao.htm.

- Presidência da Republica. 1997. “Lei 9474. Define Mecanismos Para a Implementação Do Estatuto Dos Refugiados de 1951, e Determina Outras Providências.” http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/l9474.htm

- Presidência da Republica. 2017. “Decreto 9199/17, de 20 de Novembro de 2017.” https://presrepublica.jusbrasil.com.br/legislacao/522434860/decreto-9199-17

- Presidência da Republica. 2018. “D9285.” http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2015-2018/2018/decreto/D9285.htm

- R4V. 2021. “Situation Response for Venezuelans.” Coordination Platform for Refugees and Migrants from Venezuela. https://www.r4v.info/es

- Ramanzini Junior, H., M. P. Mariano, and J. d. S. B. Gonçalves. 2022. “The Quest for Syntony: Democracy and Regionalism in South America.” Bulletin of Latin American Research 41 (2): 305–319. doi:10.1111/blar.13263.

- Ribeiro de Oliveira, A. T. 2017. “Nova lei brasileira de migração: avanços, desafios e ameaças.” Revista Brasileira de Estudos de População 34 (1): 171–179. doi:10.20947/S0102-3098a0010.

- Riggirozzi, P., and D. Tussie, eds. 2012. The Rise of Post-Hegemonic Regionalism: The Case of Latin America. United Nations University Series on Regionalism. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Risse-Kappen, T. 1994. “Ideas Do Not Float Freely: Transnational Coalitions, Domestic Structures, and the End of the Cold War.” International Organization 48 (2): 185–214. doi:10.1017/S0020818300028162.

- Sanahuja, J. A. 2012. “Regionalismo Post-Liberal y Multilateralismo En Sudamérica: El Caso de UNASUR.” In El Regionalismo “Post–Liberal” En América Latina y El Caribe: Nuevos Actores, Nuevos Temas, Nuevos Desafíos, edited by A. Serbin, L. Martinez, and H. Ramanzani Júnior. Buenos Aires: Coordinadora Regional de Investigaciones Económicas y Sociales.

- Selee, A., J. Bolter, B. Muñoz-Pogossian, and M. Hazán. 2019. “Creativity amid Crisis: Legal Pathways for Venezuelan Migrants in Latin America.” Policy Brief. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/research/legal-pathways-venezuelan-migrants-latin-america

- Serbin, A. 2009. “América Del Sur En Un Mundo Multipolar: ¿es La Unasur La Alternativa?” Nueva Sociedad (219): 146–156.

- Setzler, M. 2021. “Did Brazilians Vote for Jair Bolsonaro Because They Share His Most Controversial Views?” Brazilian Political Science Review 15 (1) 1–16. doi:10.1590/1981-3821202100010006.

- Shenoy, R. 2019. “Brazil Resettles Venezuelan Refugees – with US Help.” The World from PRX. https://theworld.org/stories/2019-07-15/brazil-resettles-venezuelan-refugees-us-help

- Silva, B. G., L. Cavalcanti, L. F. L. Costa, and M. F. R. de Macêdo. 2021. Refúgio Em Números. 6th ed.. Brasilia: Observatório das Migrações Internacionais; Ministério da Justiça e Segurança Pública/Comitê Nacional para os Refugiados. https://portaldeimigracao.mj.gov.br/pt/dados/refugio-em-numeros

- Silva, B. G., L. Cavalcanti, A. T. d. Oliveira, and M. F. d. Macedo. 2020. Refúgio Em Números. 5th ed. Brasilia: Observatório das Migrações Internacionais; Ministério da Justiça e Segurança Pública/Comitê Nacional para os Refugiados. https://www.justica.gov.br/seus-direitos/refugio/refugio-em-numeros

- UN News. 2019. “UN Agency Hails Brazil “Milestone” Decision over Venezuelan Refugees.” UN News. https://news.un.org/en/story/2019/12/1052921

- US Embassy in Brazil. 2020. “Declaração Conjunta do Presidente Jair Bolsonaro e do Presidente Donald J. Trump.” Embaixada e Consulados dos EUA no Brasil. 8 March 2020. https://br.usembassy.gov/pt/declaracao-conjunta-do-presidente-jair-bolsonaro-e-do-presidente-donald-j-trump/

- USAID. 2020. “United States Announces New Program to Support Venezuelans in Brazil | Press Release | U.S. Agency for International Development.” 29 January 2020. https://www.usaid.gov/news-information/press-releases/jan-29-2020-united-states-announces-new-program-support-venezuelans-brazil

- Vadell, J. A., and C. Giaccaglia. 2021. “Brazil’s Role in Latin America’s Regionalism: Unilateral and Lonely International Engagement.” Global Governance: A Review of Multilateralism and International Organizations 27 (1): 25–48. doi:10.1163/19426720-02701007.

- Zapata, G. P., and D. Fazito. 2018. “Comentário: o significado da nova lei de migração 13.445/17 no contexto histórico da mobilidade humana no Brasil.” Revista da Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais 25 (1 e 2): 224–237. doi:10.35699/2316-770X.2018.19540.

- Zapata, G. P., and V. Tapia Wenderoth. 2022. “Progressive Legislation but Lukewarm Policies: The Brazilian Response to Venezuelan Displacement.” International Migration 60 (1): 132–151. doi:10.1111/imig.12902.