Abstract

Violence rising in Latin America since the early 1990s has puzzled media, policymakers and academia. Characterising high scales of violence in non-political confrontations has been one of the main challenges. The main argument of this essay is that the hybrid criminal nature of violence in Latin America by non-state organisations has pushed the discussion to several misinterpretations and conceptual stretching that produces fog rather than clarity. Instead, this essay proposes a concept of criminal war that can capture the complex nature of violence in Latin America by drawing convergences and divergences from diverse fields of literature and confronting usual mischaracterisations in current Latin American research.

Introduction

Contemporary violence on the scale witnessed in Latin America since the early 1990s is a subject of study that scholars have partially grappled with in several fields: economics, political science, international relations, international law, anthropology, sociology, and history. Naturally, violence in high levels of occurrence committed by criminal organisations is a challenging phenomenon to explain. Moreover, all these fields of study have different interpretations of how violence occurs or how criminal organisations behave.

Since the 1990s in Latin America, criminal organisations have benefitted from a growing illicit drug market in the United States (Bergman Citation2018). The deregulation of guns in the US led to massive arms smuggling (Dube, Dube, and García-Ponce Citation2013; Esparza and Weigend Citation2015), and barriers to international trade were steadily lifted due to the expansion of free trade agreements. This liberalisation process led to more opportunities for illicit trade across borders and via cargo ships (Herrera Citation2019). These economic changes happened in highly unequal but growing economies with large youth bulges. Combining these factors created the ideal preconditions for criminal wars: a perfect storm of state weakness, the weak rule of law, endemic corruption, and the availability of resources with which to build armies. Soon after, states fostered violent conflicts by prosecuting criminal organisations through the use of military techniques. Paradoxically, although the outcomes have been disastrous, governments in Latin America to date continue to respond to international drug prohibition as a result of continuous demands and pressure from the US government (Felbab-Brown Citation2019).

The main argument of this essay is that violence trends in Latin America can be confused using concepts from a wide range of social sciences. These concepts were meant for political violence, not interpersonal or ‘private’ violence. While using these concepts, many scholars have not noticed that they bypassed the importance of boundaries within their fields and are drawing essentially contested concepts to an ill-defined subject.

Using civil wars to describe what happens with organised crime is the perfect example of this tendency. As Kalyvas (Citation2015) argues, the literature on civil wars relies on the political content of civil wars, different from criminal organisations driven by profit and protection rackets. Even if criminal violence trends present themselves like those in civil wars, such as profiteering (Kaldor Citation2006) and rebel governance as racket protection (Arjona, Kasfir, and Mampilly Citation2015), Kalyvas (Citation2001) asserts that the main drivers of civil war are political motivations.

Indeed, concepts like civil wars are ideal types (Weber Citation1946) and, simultaneously, essentially contested concepts (Gallie Citation1956; Collier, Hidalgo, and Maciuceanu Citation2006), because of the changing historical trends of violence and conflict. Concept formation history is directly linked to ideas formed to respond to their contexts and trends (Skinner Citation1969). In this case, war and violence are intrinsically connected by state making and state formation. Naturally, researchers find answers from the seminal work of Tilly (Citation1985) on understanding high-scale violence.

Lessing (Citation2015) formally coined the concept of criminal wars. This concept is grounded in the historical examples of battles between criminal organisations –called turf, gang or bandit wars – that have occurred in Latin America since the late 1990s. This conflict trend arose after the so-called ‘lost decade’ of growth when the region experienced sustained economic development (Bértola and Ocampo Citation2012). However, growth in this period was unequal. Parallelly, in this decade Latin America experienced a process of democratisation, pacification after civil wars, and widespread state repression.

Simultaneously, Latin America has seen a new wave of militarised responses due to pressure from the US government on Latin American governments to tackle transnational drug trafficking under the framework of the international treaties that enforce drug prohibition. The result: Latin America has become a region as deadly as countries experiencing civil or conventional wars. Since then, criminal organisations have resisted military crackdowns while advancing their market capture of various illicit goods, especially marijuana and poppy, to produce heroin and synthetic drugs (Bergman Citation2018).

Although the studies of conflict, war, violent crime and terrorism share common traits, this literature review of the conduction of criminal wars in Latin America deals with the hybrid nature of this kind of conflict before appropriately adapting or discarding elements from these areas. This review aims to illustrate the general findings and dynamics of violence in the current criminal wars to understand this concept’s usage and question the vast concept stretching for these cases. This article is a conceptual essay and not a comprehensive systematic review. Interesting reviews can be found in Imbusch, Misse, and Carrión (Citation2011), Cruz (Citation2016), Albarracín and Barnes (Citation2020) and Vilalta (Citation2020). Moreover, this essay primarily draws examples from Latin America, focused on but not limited to Mexico, Colombia, Brazil, Peru, Central America, and some cases in the Caribbean.

It is necessary to clarify and distinguish criminal wars to separate them from other phenomena like civil wars. They might look the same in terms of some events, but criminal wars have ontological, epistemological and practical differences. Criminal wars should be understood as armed conflicts, paired with but separate from civil wars. Although drug trafficking is a transnational phenomenon, these conflicts are defined by how each government – national or subnational – confronts criminal organisations.

This essay is separated into two sections. The first section includes a review of the status of the discussion on the nature of criminal violence in Latin America and why the concepts used so far fall short of encompassing this phenomenon. The second section is a defence of criminal wars as an inclusive concept to work further in comparative terms and from a political economy perspective. The political economy perspective relies on how markets are shaped by governmental policy. In the case of the criminal wars, these markets are illicit markets prosecuted by governments. In other words, strategies of prosecution of illegal goods are a form of deadly regulatory policy (Flom Citation2022).

The conceptual struggle for criminal wars

The obvious comparisons between civil and criminal wars raised because of the increase of homicide rates in Latin America. Researchers, journalists and governments have used a wide range of concepts to describe the dynamics of violence. Some are essential intellectual efforts to comprehend such a novel and complex issue. Nonetheless, some comparisons reach exaggerations or understandable misconceptions.

There are five examples of this discussion: state failure, criminal insurgencies, counterinsurgency, terrorism and militarisation. In the case of state failure, Kenny and Serrano (Citation2013) criticised the use of this essentially contested concept to qualify a situation that could represent more of a collapse of part of the state judicial apparatus. In the Mexican case, this collapse happened after the state confronted an unexpected retaliation from criminal organisations after the army’s deployment in 2006. However, it was not the collapse of the whole Mexican state. Indeed, violence and criminal governance in Mexico regions indicate state weakness. However, the heavy burden of the ideological implications of failed state paraphernalia in the US foreign policy frame leads to discussions closer to Western ideals of the state than its actual development in Latin America (Call Citation2008).

In the second case, the civil war terms filtrated easily into the Mexican discussion, especially via two authors: Grillo (Citation2012) and Schedler (Citation2018). As Kalyvas (Citation2015) argued, using terms based on the research programme on civil war can lead to misleading interpretations. Grillo mischaracterises the ontological origin of criminal organisations by using the term ‘criminal insurgency’, arguing for this term because the word ‘revolt’ is in the Merriam-Webster dictionary definition of an insurgent, equating revolt to all violence against the state. However, several forms of violence used against authority are not necessarily revolutionary or insurgent. On the contrary, evidence about the orientation of criminal organisations’ tactics demonstrates that these organisations seek to change prosecution policy, not to begin a revolution. Also, this gives the false impression that these organisations use the exact mechanisms, techniques, ideas and mobilisation repertoire used by guerrillas for the same political goal: to replace the country’s elite.

In the same terms, Sullivan and Elkus (Citation2008) argue that insurgency means changing policy with violence. Furthermore, Bunker and Sullivan (Citation2010) argue that drug cartels have come to rule territories in several countries opposed to the state. Again, this falls into a mischaracterisation of the function of the use of violence. While in civil wars, insurgencies govern territories (rebel governance) to advance an ideological goal, territorial advances are for protecting illicit private markets as criminal governance (Lessing Citation2017).

Furthermore, De la Calle and Schedler (Citation2021) situate Mexico’s political regime as the central part of the conflict by using civil war. However, the nexus between the two is unclear. Quite the reverse, as Varese (Citation1997, Citation2001, Citation2018) explains; for the cases of mafias and democratic tensions in Hong Kong and Russia, democracy is a space of opportunity for offering racketeering services to politicians or pressure groups. In this case, democracy is the scenario but not the main explanatory structure of violence. Furthermore, violent crime also happened in socialist economies, such as the Soviet Union or several parts of Africa (Bayart, Ellis, and Hibou Citation1999). Of course, Varese’s cases do not explain how mafias create large-scale violence in Latin America. His insights in the organised crime literature are closer to criminal organisations than guerrillas.

The aforementioned Latin American literature on criminal insurgencies borrowed notions from the debate on economic motivations in civil wars proposed by Collier and Hoeffler (Citation2004) and Kaldor (Citation2006). They did this by posing a supposed protracted ideological agenda of violent criminal organisations in Latin America, combined with their profits from transnational drug trafficking. Schedler (Citation2018) argued that criminal violence should be understood as an ‘economic civil war’. It was, again, assuming an ideological agency of criminal organisations. However, as another pitfall of concept stretching, these notions are highly contested. Indeed, economic motivations and greed are relevant in conflict, but Kalyvas (Citation2001, Citation2015; Berdal Citation2003, Citation2005) have argued that ideological motivations never stopped in civil wars during the twentieth century, and extraction was mainly functional for political purposes.

Furthermore, Felbab-Brown (Citation2005) and Gutiérrez Sanín (Citation2004; Citation2008) criticised the use of these notions to explain Latin American cases such as Peru and Colombia because Sendero Luminoso and the Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (FARC) were using drug trafficking as a funding mechanism. Preliminary results from the recent demobilisation process of the FARC in Colombia (UNSC Citation2020) back up this argument. Most FARC members effectively demobilised after the peace agreement instead of converging into drug trafficking. This finding challenges the idea that economic motivation is enough to participate in a civil war.

The second problem that Kalyvas (Citation2015) found in the usage of new wars, or greed and grievance frameworks for organised crime, was that it mischaracterises the motivations of individual members of violent organisations as the primary driver of conflicts rather than the conflict dynamics. In other words, it subtracts the agency of the state from the equation. Kalyvas noticed organised crime uses violence strategically and sporadically because these organisations are evading prosecution. However, when governments used militarised and counterinsurgency tactics against these organisations, these had to retaliate, starting the cycles of violence we know today.

However, it is noticeable that crime and conflict occur together. There is an extensive debate about this tactical use of crime to fund a war or whether criminal organisations can fuel those conflicts. For the purposes of this debate, I concur with some of the findings of De Boer and Bosetti (Citation2015) in their extensive review of the conflict–crime nexus. Criminal organisations tend to foster civil wars as spoilers, and some resource extraction can cause violence. However, this review was mainly done for civil wars in the Middle East. Again, the Colombian case shows the possibility of several wars happening in one region with different dynamics, although they sometimes converge. The signing of the FARC Peace Agreement in 2016 dramatically reduced homicides in that country, but criminal violence remains, showing that conflicts can materialise in parallel.

Derived from the securitisation (Buzan, Wæver, and Wilde Citation1998) of criminal violence as insurgency, two more strains of conceptual malformation grew: counterinsurgency and the characterisation of criminal organisations as terrorists. This led to policy circles fostering counterinsurgency, and academic discourse justifying it. On the academic side, again Bunker (Citation2012) argues that the violent nature of recent criminal organisations can be compared with insurgencies, justifying that these organisations challenge the ‘Westphalian state order’ – once more repeating the previous mischaracterisations. The criminal insurgency literature relied on the call of Metz (Citation2012) to re-think counterinsurgency away from the classic challenges. However, Metz also argues that policymakers should be wary of the consequences of a maladapted use of counterinsurgency.

Contrary to those ideas, Ucko (Citation2013) has criticised the expansion of counterinsurgency techniques for conflicts and situations beyond the classical missions by Western powers during the twentieth century. I concur with Ucko (Citation2012) that a more comprehensive understanding of war is fundamental beyond a narrow western-centric approach to insurgency. The consequences have already been documented in Latin America. Felbab-Brown (Citation2009) showed how counterinsurgency techniques against criminal organisations backfired because these gained popular support in specific communities and strengthened their capacity to respond to the military. In particular, Pérez Ricart (Citation2020) documented how the use of the ‘kingpin strategy’ (beheading criminal organisations) fostered by the United States Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) caused even worse cycles of violence in the region.

On the terrorism side of the discussion, indeed, criminal organisations in the region have used terror tactics: bombings, vehicle-ramming or rocket attacks. However, the field of terrorism studies is highly contentious. The same criminal insurgency authors filtrated the terrorism discussion into the criminal violence field (Teiner Citation2020). However, I concur with Phillips (Citation2018) and Shirk and Wallman (Citation2015). Bringing the essentially contested concept of terrorism carries confusion by re-introducing a contentious political ideology debate. However, understanding terrorist tactics as a communication method has helped criticise the use of counterinsurgency and anti-terrorist policies for organised crime. Phillips (Citation2015) showed convincingly how this strategy failed in Mexico, fostering cycles of violence. Again, this empirically shows how treating a criminal organisation as an insurgent or terrorist organisation has not worked so far.

Finally, although the debate about militarisation has brought wider clarity and engagement with the empirical evidence regarding the question of violence in Latin America, this field of research has fallen short of characterising the whole phenomenon. All the regional cases show that the military has intervened with their tactics, such as dismantling organisations with violence rather than detentions and substituting policing techniques (Garzón and Bailey Citation2016; Flores-Macías and Zarkin Citation2021; Flores-Macías Citation2018; Pion-Berlin and Trinkunas Citation2011). I concur with their observations: the military fosters violent cycles rather than stopping them. However, part of this literature needs to carefully connect the origin of the conflict: the international pressure for militarising the war on drugs in Latin America.

Evidence indicates that the onset of these wars’ most violent phases came from the pressure of the US government. This pressure escalated their regional enforcement operations via military forces (Andreas Citation1995; Nadelmann Citation1989; Levine Citation2003; Serrano Citation2003). That is why there were high homicide rates in the region after the 1990s. Indeed, the presence of the military in Latin America on drug trafficking operations is historical (Loveman Citation1999). Furthermore, anti-drug prohibition precedes militarisation (Gootenberg and Campos Citation2015). However, the difference is in how governments steadily escalated the use of force coming from the pressures of the US government.

Effectively, it can be argued that not only Latin America deploys violent methods to enforce drug prohibition. However, the critical difference relies on the diversity of techniques used. For example, it seems that the increase in homicide rates in cities of the United States or Europe was produced by disorganised gangs (Reuter Citation1983; Hagedorn Citation2005, Citation2008). These countries did not have militarised interventions because they did not implement the prohibition regime in their territories in the same way the US pressures Latin American governments to do. Instead, they repress using police brutality, high incarceration rates, and race labelling (Hinton and Cook Citation2021; Williams Citation2015). In Latin America, the full-scale military challenge to criminal organisations had two consequences. Either these entrepreneurial organisations perish by militarised force, or transform themselves, usually from protection rackets of illicit markets (in terms of Gambetta Citation1996) into fully operational armies.

Extensive literature has pointed out how the state fosters violent retaliation by criminal organisations. Jones (Citation2016), Durán-Martínez (Citation2017), Lessing (Citation2017), Trejo and Ley (Citation2020), Wolf (Citation2009), Yashar (Citation2018), Castillo and Kronick (Citation2020), Moncada (Citation2013), Arias (Citation2006) and Koonings (Citation2012) have carried through the analysis of the increase of violence in Latin America from diverse perspectives. Nonetheless, they all include a remarkable coincidence: the use of military warfare has led to increased violence. Alternatively, the massive deportation of gang members from the US to El Salvador and Guatemala in Central America created, almost instantly, brand-new criminal armed organisations (Cruz Citation2016; Wolf Citation2010). None of the cases they have studied escapes the influence of the US government or the prohibition regime by using militarised violence.

The previous examples show how scholars, journalists and policy circles engage in concept stretching (Sartori Citation1970) – although, in epistemological terms, these debates are part of a historical process of theory building and crafting a research programme around the criminal war question. For Lakatos (Citation1976) all theories have fundamental presumptions that distinguish them from others. Those are called hardcore. Subsequently, evidence from hardcore and peripheral research supports it. Even when further research discards peripheral findings, a theory does not become obsolete in the research process if the hard core remains falsifiable and resistant to tests (Chalmers Citation2013). In criminal wars, basic assumptions are currently in development. Furthermore, more sophisticated scholarship on Latin America has appeared, and I review it below. This article is part of the primary endeavours of building the hardcore criminal wars theory.

Researchers have found convergences of criminal wars from several angles, such as violence logics and techniques, conformation and motivations of non-state violent organisations, protection racketeering and illicit traffic activities, patterns of diffusion of homicide, onset, duration and termination of conflicts, mobilisation mechanisms, structures, and individual profiles of violence specialists. Nevertheless, for clarity, these concepts must be tested and built congruently with criminal wars’ nature. Moreover, some of them probably are contested (Gallie Citation1956; Collier, Hidalgo, and Maciuceanu Citation2006) within their fields. Therefore, empirical results must lead to adaptations or reinterpretations.

The seminal literature on organised crime did not conceive the massive use of violence as part of the standard repertoire of actions in which these organisations could engage. Also, the studies of war and conflict have struggled with the possibility of non-state actors that do not have profound and inheritable ideological motivations. In the case of organised crime literature, Gambetta (Citation1996) in The Sicilian Mafia sharply portrays the political economy of organised crime. Violence is inherently costly and usually avoided, but it can happen under certain circumstances. In civil war literature, scholars use Kalyvas’s (Citation2006) The Logic of Violence in Civil War to explain organised crime violence because it describes how violence is used strategically in conflict. However, it is essential to remember that his focus is on political violence, not criminal.

Nonetheless, both Gambetta and Kalyvas’s books show a seminal clarity in understanding the perfectly ontological source of their subjects’ motivations in order to frame them in the landscape of strategic decisions theory. Unsurprisingly, scholars have complimented both books on explaining criminal wars in Latin America. One is helpful for the inherent motivations and structures of organised crime, and the other is on violence against the state. I argue that criminal wars in Latin America reflect these two phenomena.

Lessing coined the term ‘criminal war’ because these two words together can be a good concept. Paradoxically, Lessing (Citation2015, Citation2017), in his book and in his seminal article, does not define a single criminal war concept. Instead, he underlines a theory of their logic and proposes a typology of criminal wars. The logic of his violent lobbying theory is the main component of his concept because it shows how criminal organisations use violence strategically to protect illicit markets. However, Lessing wants to differentiate disputes between criminal organisations (turf wars) and the state (cartel–state).

Nonetheless, other scholars recognise a grey zone between cartel and turf wars. Therefore, it is essential to integrate the political economy side of the conflict. There is an international drug prohibition regime that, combined with the treaties regarding transnational organised crime, fosters the otherwise exceptional use of force, either by causing their onset or by amplifying their duration. These conflicts’ onset coincided with the US government’s pressure to deploy militarised tactics and agencies to regulate an illicit market that used to be controlled by criminal law agencies since Ronald Reagan confronted the ‘crack epidemic’ in the early 1980s. Therefore, I consider that the differentiation between cartel wars and turf wars is essentially artificial. The militarised governmental interventions nurture both types of criminal war cycles. Both concepts are useful but they represent the two sides of the same coin. As Sartori (Citation1970) argues, concepts that are too specific can lose their inclusiveness and capacity to be compared in the future.

In that sense, the directionality or logic of violence is not enough to give the concept of criminal wars the strength to understand what happens in Latin America. Profit cannot be enough as the distinction. The massive use of violence or policy change via violent lobbying by criminal organisations cannot either. The key marker is the government’s military use of force beyond the criminal law paradigm. The justification for this use of force is the existence of a new international system of drug prohibition and extraordinary measures against transnational organised crime.

An important caveat is necessary for the case of Brazil. Indeed, apparently, as Lessing (Citation2017) argues (chapter 6, Making Peace in Drug Wars), the setting for criminal wars in that country has been chiefly Rio de Janeiro. Furthermore, local police forces seem to copy military techniques from other countries to confront gangs in the favelas (Varsori Citation2021). However, as Nadelmann (Citation1988) argues, drug policy is an export acquired not only by pressure but also by imitation. Moreover, as Mora (Citation1996) defends, the effect of militarised efforts of Andean governments in South America trickled over to Brazil. Eventually, the Brazilian military has taken advantage of the lack of civil control to share its techniques with police forces to gain political power (Lima, Silva, and Rudzit Citation2021).

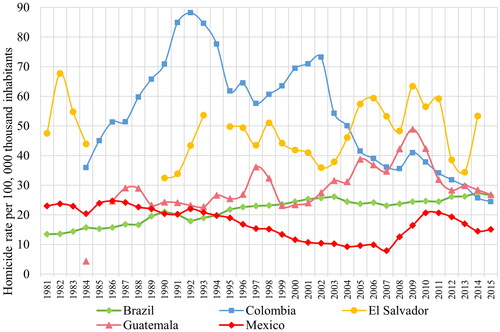

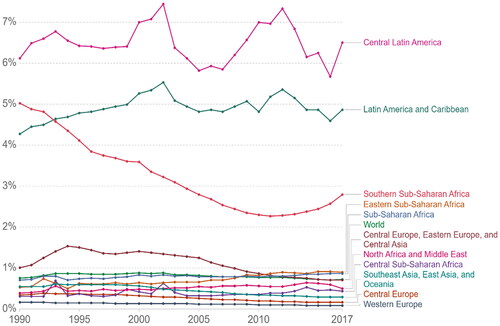

Data trends in show some fundamental changes in Latin America: the end of civil wars, and the beginning of military-driven drug policies and gang suppression policies. Also, as shown in , Latin America has higher homicide rates globally (Mandela Citation2002; UNODC Citation2019). A case country that might seem to be an outlier is Venezuela. However, Kronick (Citation2020) has recently found that military drug operations in Colombia have transferred the conflict to the Venezuelan territory. These findings show how criminal wars must be researched more from a regional scope. Criminal wars in some countries may spread to others.

Figure 1. Homicide rates in Latin America from 1981 to 2015.

Source: World Health Organization Causes of Death Database.

Figure 2. Share of deaths from homicide by regions, 1990 to 2017.

Source: Global Burden of Disease Collaborative Network. Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Results. Seattle, United States: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), 2018. Map: https://ourworldindata.org/homicides.

Following the previous arguments, I summarise part of this debate in . The table shows the commonly used concepts in the most critical research about Latin American violence. I reviewed them through the conceptual tests by Gerring (Citation1999). Overall, concept overstretching, too widely arching conceptual limits, and primarily non-differentiation from similar phenomena necessitates a new concept, the one I propose in the next section. The most frequent problem is that other concepts do not help to differentiate criminal violence in Latin America from other types of conflict. Indeed, concepts are ideal types and must be adjusted to material conditions. Moreover, transposing the grey zones directly into the conceptual frameworks does not clarify comparisons. The second most common problem is that by linking the concept to either just democracy or just drugs leaves other illicit markets or types of political regimes out of the question. Other concepts describe a part of the phenomenon as militarisation or anomie (paired for ecologies). Moreover, and finally, most authors recognise that criminal organisations are non-state armed groups. Mafias, gangs and cartels can be those. Being one of those should mean immediately that these are non-state armed groups.

Table 1. Concepts relating to Latin American violence and criticisms.

A criminal war concept

Following this argument, I propose the concept of criminal war: a violent conflict between the state and criminal organisations, or between criminal organisations. The onset, duration and continuation of which are fostered by local or national governments’ use of militarised force to implement a regime of prohibition of any illicit goods or activities. In these conflicts, criminal organisations form private armies to resist, combat and lobby against the strategies of the state and other criminal organisations to protect their profitable illicit activities. In the following paragraphs, I will defend this concept.

Regarding the political economy dimension of the conflict, the critical element of the concept is that the prosecution of illicit markets is a result of the political decision to implement prohibition regimes. Furthermore, as discussed before, these prohibition regimes are based on international treaties or national criminal law. Concerning the military strategy side, the use of physical force to enforce the prohibition regime aims to gain surrender after the criminal organisations no longer have any capacity to fight (Echevarria Citation2017).

According to Sartori’s (Citation1970) view, I defend that this concept can travel with parsimony because it does not explicitly mention the drug prohibition regime historically grounded in the twentieth century. Also, it recognises that any other prohibition regime, either national or international, can be implemented by the military, causing a violent conflict beyond disorganised crime. Based on Gerring’s (Citation1999) classification, a good concept allows clear differentiation from other types of conflict. This concept helps to classify and gather two familiar fields of knowledge: crime and conflict studies.

In comparative politics terms, although this concept comes from the aforementioned examples of Latin America, some other regions’ cases of widespread violence regarding criminal violence could be analysed using these lenses. However, there have been cases of non-organised conflict-based violence. So classifying a case requires careful examination. For example, there have been street gang violence and rising crime rates in Argentina and Chile in recent years. The US case with alcohol prohibition in the early twentieth century and current high rates of violence in US cities could be analysed; however, they do not seem to be cases of militarised force, but rather abuses of the police force. In Peru or Colombia, guerrillas could use drug trafficking to fund their political organisations, which are not motivated by profit. The same can be said for Afghanistan’s opium production, which is used, prosecuted or tolerated by the Taliban in-between foreign interventions.

It is crucial to revise essential questions regarding building criminal wars literature upon convergences with other fields. One of the most critical matters is defining the threshold behind how to describe it as war. Some scholars studying violence in Latin America have avoided using the term war because of the political and legal implications that it could entail. However, other scholars use the term war on drugs freely. It helps to differentiate this from other forms of violence in Latin America. For example, there are guerrillas, vigilantes, paramilitary groups and gangs.

Fortunately, Freedman (Citation2012, 20) has made critical remarks regarding this debate. Freedman argues that wars are a perennial human phenomenon regarding human organisations, and the modern era of states shapes our contemporary view. Freedman argues that war can happen on small scales, with diverse motives (not only ideological), and can also be about illicit markets. As Davis (Citation2009) argues, it is understandable that insecurity in Latin America also seems to be a state-building challenge for constructing central authority, not necessarily a war. However, in the terms of Freedman, Howard (Citation1984) and Echevarria (Citation2017), the critical element of wars is the willingness to use deadly force to get the enemy to surrender to fulfil wider strategic goals.

War is ingrained in the political will to use violence against an opponent, in the tradition of Clausewitz’s (Citation2008) study of conflict. A common misunderstanding of researchers on crime and violence in Latin America is that they believe political objectives are ideological. This has happened in the field of genocides (Maynard Citation2022). That explains why they struggle with defining the violence in the region, either by avoiding the word ‘war’ or using it without conceptual care. Even military historians have been clear that ideology is not the only driver of war (Soutou Citation2014). Political goals are not the same as ideological purposes or changes of the ruling class. Indeed, revolutions and civil war have ideological motivations, but the ideology it is rooted in is insurgencies’ organisational goals, not individual non-state combatants’ motives. However, just from reading Freedman’s argument, war comes from the challenger, against the state, and from the state itself.

Indeed, it seems paradoxical that weak states can wage war against seemingly powerful criminal organisations. Literature about mafias usually empathises that the state tolerates and negotiates with them, either by peaceful pacts or corruption (Gambetta Citation1996, 214–220). However, it is crucial to avoid the scholars and journalists who use the ‘failed state’ as a valid concept by misunderstanding Weber’s concept (Citation1946, 33; Citation1978, 90) as an absolute rather than an ideal type. The state gathers bureaucracy and leadership in various organisations, so implementing the prohibition regime can stand. At the same time, there can be corruption within organisations and bureaucrats, including the military (Trejo and Ley Citation2020).

The presence of the state in Latin America has not been historically uniform in the territory. Moreover, government policy capacities are considerably underdeveloped. These structural conditions came from the urgent need to build professional armies for civil and conventional wars in Latin America during the nineteenth century. Therefore, troops came first, civil bureaucracies later, and police enforcement agencies last until today (O’Donnell Citation1993; Mann Citation2008). The state’s formation in Latin America diverges from the European states’ state-building process (Centeno Citation2002). Nevertheless, they concur that political elites sometimes faced warlords and bandits disputing the central authority (Hobsbawm Citation2000; Olson Citation1993; Tilly Citation1985). However, it is not uncommon to think that criminal wars are also part of the process of state-building in the region.

There is a wide debate on the legal side about the nature of violent criminal organisations. Rodgers and Muggah (Citation2009) argued that Central American gangs could be understood as non-state armed groups. Effectively, they argue that these gangs do not seek to overthrow the state, just to undermine certain functions. Although I concur with this assessment by considering gangs as parts of criminal wars, I think the academic fields of international humanitarian law (IHL) and national law and the international organisms that discuss these matters must be careful in adaptating their precepts for criminal organisations.

As Rodiles (Citation2018) argues, simplifying the nature of violence in Latin America as non-international armed conflict as it is classically understood in IHL could reinforce violent military interventions. Unfortunately, wars usually begin without any legal mechanism behind them, although it can be claimed these are illicit. The facts that define social research are the ground events, not legality.

Presidents in the region have proposed several names for their efforts: democratic security policy in the case of Uribe in Colombia, mano dura or super mano dura in the case of presidents Francisco Flores and Antonio Saca in El Salvador, and combat against organised crime for Felipe Calderón in Mexico. These policies created the now known criminal wars without legal declarations. However, as Trevino-Rangel et al. (Citation2022) argue, governments have avoided IHL by creating new legal frameworks under the umbrella of the international drug prohibition and transnational organised crime regime (Andreas and Nadelmann Citation2008; Berdal and Serrano Citation2002, Andreas and Price Citation2001). In strategic terms (Howard Citation1984), these regimes are used as a political justification for the use of force. In other terms, military securitisation of criminal prosecution in Latin America already happened.

It is natural that scholars are finding elements of previous non-international armed conflicts (NIACs) in Latin American cases (Comer and Mburu Citation2016). Understandably, bringing IHL to the table creates the possibility to scrutinise governments’ use of force (Sassòli and Olson Citation2008; Padin Citation2022). The tactical use of violence and territorial disputes by criminal organisations are the main part of this side of the argument. But as David (Citation2014) argued, the existence of this figure has been discussed in international jurisprudence because it is still a challenging topic. As proof of this, Kalmanovitz (Citation2022) argues that criminal organisations could not comply with IHL standards to be responsive to international mechanisms, even if they use tactical violence and have territorial disputes against the state. The IHL field is rightfully responding to the political and field consequences of qualifying a conflict as a NAIC, but is not necessarily in sync with social sciences research. As David (Citation2014) argued, the existence of these conflicts precedes the defined essence of them. NIACs are a nascent figure in IHL trying to grapple with the complexity of civil wars in the twentieth century.

Certainly, high homicide rates can not constitute a war marker. On different sides, Reuter (Citation1983) and Collins (Citation2009) agree that those fights and retaliations driven by local conflict are part of urban street violence. From a different perspective, Eisner (Citation2001, Citation2003), echoing Norbert Elias’s work, argues that violence comes from other expressions, such as honour killings. Bergman (Citation2018, 73–77), endorsing social disorganisation and opportunity theory in general, proposes that economic growth and social processes also play a role in local violent disputes. These authors do not deny violence’s organisation. Nevertheless, they are sceptical that there is only one driver behind all homicides.

In this debate, the Uppsala Conflict Data Program (UCDP) (Sundberg, Eck, and Kreutz Citation2012, 352–353) has defined ‘non-state conflict as the use of armed force between two organized armed groups, neither of which is the government of a state. … In state-based conflicts, UCDP requires an incompatibility over government and/or territory’. However, they discarded ideological purposes as too subjective for classifying conflicts. Naturally, the UCDP non-state conflict concept coincides with the interpretation by Freedman of Clausewitz’s conception of war in the realm of violent criminal activities. However, it is problematic because their classification is so broad that it includes non-state conflicts like Brazil, Colombia, Mexico, El Salvador and Guatemala, and divergent cases such as Peru, Bolivia and Venezuela.

Again, as other scholars did, the UCDP examined non-state actors’ motivations but disregarded governments’ political willingness to use the military to deploy wars. By just counting and classifying without clear political distinctions, they merge ongoing criminal wars with cases with large-scale homicide rates. Some countries may be experiencing more interpersonal street violence rather than drug trafficking-related violence. And counting deaths as conflict evidence is problematic for other reasons. Simultaneously, Bergman (Citation2018, 315) shows the low quality of homicide data in Latin America. Krause (Citation2013) questions whether researchers can immediately attribute those deaths to the conflict.

Still, the historical coincidences between the international drug prohibition regime’s policies and homicide trends have proven a more amicable explanation for increasing violence. Nevertheless, to wind up this argument, I interrogate around the UCDP concept because it excludes the state’s motivations. They commit the same misidentification that brings a country with high-scale violence into the conflict realm without considering the dimension of prohibition regimes. I argue that massive violence must be understood within a theoretical framework regarding structural and meso-organisational conflict processes that war studies bring.

Governmental use of violent enforcement causes what Bergman (Citation2018) calls a high violent equilibrium, what Lessing (Citation2017) calls fierce lobbying, and what Castillo and Kronick (Citation2020) call interdiction. In response, criminal organisations must dissuade the state from using violence to disrupt their trafficking activities (Phillips and Ríos Citation2020; Durán-Martínez Citation2015; Phillips Citation2015). Moreover, they use violence strategically to confuse authorities into confronting their competitors (Atuesta Citation2017). Even these organisations can employ violence on a large scale to provoke a de-escalation from the government (Atuesta and Ponce Citation2017). Also, these tactics can create an opportunity for monopolising trafficking routes (Ramírez-de-Garay Citation2016).

On the other hand, some researchers point out that criminal organisations also look to monopolising regions. Agents of the state grant protection via corrupt agreements, as the mafia literature usually notes. These findings converge with the civil war literature that Lessing (Citation2017) has identified: criminal governance. Criminal organisations, as well as guerrillas, tend to govern spaces to advance their objectives. Indeed, their goals are not the same, but buying territorial management and corrupting authorities are both part of conflict and war (Lessing Citation2018; Arias Citation2006; Ley, Mattiace and Trejo Citation2019; Magaloni, Franco-Vivanco, and Melo Citation2020; Pansters Citation2018). On this matter, rather than an apparent contradicting fact, war-making, state weakness and criminal governance are deeply enmeshed parts of the complexity of wars.

Conclusions

The debate about violence in Latin America sheds light on the necessity for broader interdisciplinary conceptual debates to understand novel phenomena to craft careful studies. Understandably, war, conflict and organised crime gather discussions from close but not well-communicated fields of knowledge. Due to the temporality of the rise of homicides in the region, the debates about civil wars in Africa or Eastern Europe, or crime in Europe, filtrated easily to explain a novel situation in a region that traditionally experienced political violence.

Indeed, criminal wars might seem new to some observers. However, the phenomenon above is not, and there have been violent conflicts over illicit goods throughout human history. These wars are a by-product of a regional political economy of drug prohibition, and therefore are profoundly historical Latin American events. Fortunately, by carefully examining the evidence – qualitative and quantitative – recent scholars have shaped a detailed picture of the situation instead of using concepts without considering their inner contested debates. This is the pathway forward: building a research programme on the ongoing conflicts and using the analytical tools of the diversity of fields to draft a middle-ground theory of criminal wars.

Acknowledgments

A previous version of this manuscript was presented as a conference proceeding in the 2021 IPSA World Congress of Political Science. Also, I received helpful comments on previous versions by Mats Berdal, Sukanya Podder, Andrés Mejía Acosta, Diego Castañeda and Luis Ángel Monroy Gómez Franco, and the two anonymous reviewers. Of course, opinions, mistakes and misinterpretations are all mine.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Bibliography

- Albarracín, J., and N. Barnes. 2020. “Criminal Violence in Latin America.” Latin American Research Review 55 (2): 397–406. doi:10.25222/larr.975.

- Andreas, P. 1995. “Free Market Reform and Drug Market Prohibition: U.S. Policies at Cross-Purposes in Latin America.” Third World Quarterly 16 (1): 75–88. doi:10.1080/01436599550036248.

- Andreas, P., and E. Nadelmann. 2008. Policing the Globe: Criminalisation and Crime Control in International Relations. Oxford: OUP.

- Andreas, P., and R. Price. 2001. “From War Fighting to Crime Fighting: Transforming the American National Security State.” International Studies Review 3 (3): 31–52. doi:10.1111/1521-9488.00243.

- Arias, E. D. 2006. “The Dynamics of Criminal Governance: Networks and Social Order in Rio De Janeiro.” Journal of Latin American Studies 38 (2): 293–325. doi:10.1017/S0022216X06000721.

- Arjona, A., N. Kasfir, and Z. Mampilly, eds. 2015. Rebel Governance in Civil War. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9781316182468.

- Atuesta, L. H. 2017. “Narcomessages as a Way to Analyse the Evolution of Organised Crime in Mexico.” Global Crime 18 (2): 100–121. doi:10.1080/17440572.2016.1248556.

- Atuesta, L. H., and A. F. Ponce. 2017. “Meet the Narco: Increased Competition among Criminal Organisations and the Explosion of Violence in Mexico.” Global Crime 18 (4): 375–402. doi:10.1080/17440572.2017.1354520.

- Auyero, J., P. Bourgois, and N. Scheper-Hughes, eds. 2015. Violence at the Urban Margins. Oxford: OUP. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780190221447.001.0001.

- Bayart, J. F., S. Ellis, and B. Hibou. 1999. The Criminalization of the State in Africa. London: James Currey.

- Berdal, M. 2003. “How “New” Are “New Wars”? Global Economic Change and the Study of Civil War.” Global Governance: A Review of Multilateralism and International Organizations 9 (4): 477–502. doi:10.1163/19426720-00904007.

- Berdal, M. 2005. “Beyond Greed and Grievance: And Not Too Soon… a Review Essay.” Review of International Studies 31 (4): 687–698. doi:10.1017/S0260210505006698.

- Berdal, M., and M. Serrano. 2002. “Transnational Organised Crime and International Security: The New Topography.” In Transnational Organized Crime and International Security: Business as Usual?, edited by M. Berdal and M. Serrano, 197–207. London: Lynne Rienner. doi:10.1515/9781626370197.

- Bergman, M. 2018. More Money, More Crime: Prosperity and Rising Crime in Latin America. Oxford: OUP. doi:10.1093/oso/9780190608774.001.0001.

- Bértola, L., and J. A. Ocampo. 2012. The Economic Development of Latin America since Independence. Oxford: OUP.

- Bunker, R. J. 2012. “Changing Forms of Insurgency: Pirates, Narco Gangs and Failed States.” In The Routledge Handbook of Insurgency and Counterinsurgency, edited by P. Rich and I. Duyvesteyn, 55–63. London: Routledge.

- Bunker, R. J., and J. P. Sullivan. 2010. “Cartel Evolution Revisited: Third Phase Cartel Potentials and Alternative Futures in Mexico.” Small Wars & Insurgencies 21 (1): 30–54. doi:10.1080/09592310903561379.

- Buzan, B., O. Wæver, and J. D. Wilde. 1998. Security: A New Framework for Analysis. London: Lynne Rienner Publishers. doi:10.1515/9781685853808.

- Call, C. T. 2008. “The Fallacy of the ‘Failed State’.” Third World Quarterly 29 (8): 1491–1507. doi:10.1080/01436590802544207.

- Castillo, J. C., and D. Kronick. 2020. “The Logic of Violence in Drug War.” American Political Science Review 114 (3): 874–887. doi:10.1017/S0003055420000246.

- Centeno, M. A. 2002. Blood and Debt: War and the Nation-State in Latin America. United States: Penn State Press. doi:10.1515/9780271031620.

- Chalmers, A. F. 2013. What Is This Thing Called Science?. London: Hackett Publishing.

- Clausewitz, C. V. 2008. On War. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Collier, D., F. D. Hidalgo, and A. O. Maciuceanu. 2006. “Essentially Contested Concepts: Debates and Applications.” Journal of Political Ideologies 11 (3): 211–246. doi:10.1080/13569310600923782.

- Collier, P., and A. Hoeffler. 2004. “Greed and Grievance in Civil War.” Oxford Economic Papers 56 (4): 563–595. doi:10.1093/oep/gpf064.

- Collins, R. 2009. Violence: A Micro-Sociological Theory. Princeton: Princeton University Press. doi:10.1515/9781400831753.

- Comer, C. A., and D. M. Mburu. 2016. “Humanitarian Law at Wits’ End: Does the Violence Arising from the “War on Drugs” in Mexico Meet the International Criminal Court’s Non-International Armed Conflict Threshold?.” In Yearbook of International Humanitarian Law, edited by T. D. Gill, 180: 67–89. The Hague: TMC Asser Press. doi:10.1007/978-94-6265-141-8_3.

- Cruz, J. M. 2010. “Central American Maras: From Youth Street Gangs to Transnational Protection Rackets.” Global Crime 11 (4): 379–398.

- Cruz, J. M. 2016. “State and Criminal Violence in Latin America.” Crime, Law and Social Change 66 (4): 375–396. doi:10.1007/s10611-016-9631-9.

- David, E. 2014. “Internal (Non-International) Armed Conflict.” In The Oxford Handbook of International Law in Armed Conflict, edited by A. Clapham and P. Gaeta, 353–362. London: OUP. doi:10.1093/law/9780199559695.003.0014.

- Davis, D. E. 2009. “Non-State Armed Actors, New Imagined Communities, and Shifting Patterns of Sovereignty and Insecurity in the Modern World.” Contemporary Security Policy 30 (2): 221–245. doi:10.1080/13523260903059757.

- De Boer, J., and L. Bosetti. 2015. “The Crime-Conflict "Nexus": State of the Evidence.” Occasional Paper 5 (9): 1–25.

- De la Calle, L., and A. Schedler. 2021. “¿Borrón sin cuenta nueva? La injusticia transicional en guerras civiles económicas.” Perfiles Latinoamericanos 29 (51): 195–220. doi:10.18504/pl2957-008-2021.

- Dube, A., O. Dube, and O. García-Ponce. 2013. “Cross-Border Spillover: US Gun Laws and Violence in Mexico.” American Political Science Review 107 (3): 397–417. doi:10.1017/S0003055413000178.

- Durán-Martínez, A. 2015. “To Kill and Tell? State Power, Criminal Competition, and Drug Violence.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 59 (8): 1377–1402.

- Durán-Martínez, A. 2017. The Politics of Drug Violence: Criminals, Cops and Politicians in Colombia and Mexico. Oxford: OUP.

- Echevarria, A. J., II. 2017. Military Strategy: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: OUP.

- Eisner, M. 2001. “Modernisation, Self-Control and Lethal Violence. The Long-Term Dynamics of European Homicide Rates in Theoretical Perspective.” British Journal of Criminology 41 (4): 618–638. doi:10.1093/bjc/41.4.618.

- Eisner, M. 2003. “Long-Term Historical Trends in Violent Crime.” Crime and Justice 30: 83–142. doi:10.1086/652229.

- Esparza, D. P., and E. Weigend. 2015. “The Illegal Flow of Firearms from the United States into Mexico: A State-Level Trafficking Propensity Analysis.” Journal of Trafficking, Organized Crime and Security 1 (2): 115–125.

- Felbab-Brown, V. 2005. “The Coca Connection: Conflict and Drugs in Colombia and Peru.” Journal of Conflict Studies 25 (2): 104–128.

- Felbab-Brown, V. 2009. Shooting up: Counterinsurgency and the War on Drugs. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press.

- Felbab-Brown, V. 2019. “The Crime-Terror Nexus and Its Fallacies.” In The Oxford Handbook of Terrorism, Edited by Chenoweth, E. English, R. Gofas, A and Kalyvas, S.N. Oxford: OUP: 366–383.

- Flom, H. 2022. The Informal Regulation of Criminal Markets in Latin America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781009170710.001.

- Flores-Macías, G. 2018. “The Consequences of Militarising Anti-Drug Efforts for State Capacity in Latin America: Evidence from Mexico.” Comparative Politics 51 (1): 1–20. doi:10.5129/001041518824414647.

- Flores-Macías, G. A., and J. Zarkin. 2021. “The Militarisation of Law Enforcement: Evidence from Latin America.” Perspectives on Politics 19 (2): 519–538. doi:10.1017/S1537592719003906.

- Freedman, L. 2012. “Defining War.” In The Oxford Handbook of War. Edited by Boyer, Y. and Lindley-French, J.Oxford: OUP: 16–29.

- Gallie, W. B. 1956. “IX. – Essentially Contested Concepts.” Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society 56 (1): 167–198. doi:10.1093/aristotelian/56.1.167.

- Gambetta, D. 1996. The Sicilian Mafia: The Business of Private Protection. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Garzón, C. J., and J. Bailey. 2016. “Displacement Effects of Supply-Reduction Policies in Latin America. A Tipping Point in Cocaine Trafficking, 2006-2008.” In The Handbook of Drugs and Society, edited by H. H. Brownstein, 482–523. New York: Wiley Blackwell.

- Gerring, J. 1999. “What Makes a Concept Good? A Criterial Framework for Understanding Concept Formation in the Social Sciences.” Polity 31 (3): 357–393. doi:10.2307/3235246.

- Gootenberg, P., and I. Campos. 2015. “Toward a New Drug History of Latin America: A Research Frontier at the Center of Debates.” Hispanic American Historical Review 95 (1): 1–35. doi:10.1215/00182168-2836796.

- Grillo, I. 2012. El Narco: Inside Mexico’s Criminal Insurgency. London: Bloomsbury Publishing USA.

- Gutiérrez Sanín, F. 2004. “Criminal Rebels? A Discussion of Civil War and Criminality from the Colombian Experience.” Politics & Society 32 (2): 257–285. doi:10.1177/0032329204263074.

- Gutiérrez Sanín, F. 2008. “Clausewitz Vindicated. Economics and Politics in the Colombian War.” In Order, Conflict, and Violence, edited by S. S. I. Kalyvas and T. Masoud, 219–241. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511755903.

- Hagedorn, J. M. 2005. “The Global Impact of Gangs.” Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice 21 (2): 153–169. doi:10.1177/1043986204273390.

- Hagedorn, J. 2008. A World of Gangs: Armed Young Men and Gangsta Culture. Vol. 14. Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press.

- Herrera, J. S. 2019. “Cultivating Violence: Trade Liberalisation, Illicit Labor, and the Mexican Drug Trade.” Latin American Politics and Society 61 (03): 129–153. doi:10.1017/lap.2019.8.

- Hinton, E., and D. Cook. 2021. “The Mass Criminalization of Black Americans: A Historical Overview.” Annual Review of Criminology 4 (1): 261–286. doi:10.1146/annurev-criminol-060520-033306.

- Hobsbawm, E. 2000. Bandits. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolso.

- Howard, M. 1984. “The Relevance of Traditional Strategy.” In The Causes of Wars and Other Essays, Edited by Howard, M. 85–101. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Imbusch, P., M. Misse, and F. Carrión. 2011. “Violence Research in Latin America and the Caribbean: A Literature Review.” International Journal of Conflict and Violence 5 (1): 87–154.

- Jones, N. P. 2016. Mexico’s Illicit Drug Networks and the State Reaction. Georgetown: Georgetown University Press.

- Kaldor, M. 2006. New & Old Wars. London: Polity.

- Kalmanovitz, P. 2022. “Can Organised Criminal Organisations Be Non-State Parties to Armed Conflict?” International Review of the Red Cross, 1–19. doi:10.1017/S1816383122000510.

- Kalyvas, S. N. 2001. ““New” and” Old” Civil Wars: A Valid Distinction?” World Politics 54 (1): 99–118. doi:10.1353/wp.2001.0022.

- Kalyvas, S. N. 2006. The Logic of Violence in Civil War. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511818462.

- Kalyvas, S. N. 2015. “How Civil Wars Help Explain Organised Crime – and How They Do Not.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 59 (8): 1517–1540. doi:10.1177/0022002715587101.

- Kenny, P., and M. Serrano. 2013. “Introduction: Security Failure versus State Failure.” In Mexico’s Security Failure, edited by P. Kenny and M. Serrano. 13–38. London: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203805787-6.

- Koonings, K. 2012. “New Violence, Insecurity, and the State: Comparative Reflections on Latin America and Mexico.” In Violence, Coercion, and State-Making in Twentieth-Century Mexico, edited by W. G. Panster, 255–278. Stanford: Stanford University Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctvqsdwmh.18.

- Krause, K. 2013. “Challenges to Counting and Classifying Victims of Violence in Conflict, Post-Conflict, and Non-Conflict Settings.” In Counting Civilian Casualties: An Introduction to Recording and Estimating Nonmilitary Deaths in Conflict, edited by T. B. Sybolt, J. F. Aronson, and B. Fischhoff, 265–284. Oxford: OUP. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199977307.003.0013.

- Kronick, D. 2020. “Profits and Violence in Illegal Markets: Evidence from Venezuela.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 64 (7-8): 1499–1523. doi:10.1177/0022002719898881.

- Lakatos, I. 1976. “Falsification and the Methodology of Scientific Research Programmes.” In Can Theories Be Refuted?, edited by S. G. Harding, 205–259. London: Springer.

- Lessing, B. 2015. “Logics of Violence in Criminal War.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 59 (8): 1486–1516. doi:10.1177/0022002715587100.

- Lessing, B. 2017. Making Peace in Drug Wars: Crackdowns and Cartels in Latin America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781108185837.

- Lessing, B. 2018. “Conceptualising Criminal Governance.” Perspectives on Politics, 19 (3): 1–20.

- Levine, H. G. 2003. “Global Drug Prohibition: Its Uses and Crises.” International Journal of Drug Policy 14 (2): 145–153. doi:10.1016/S0955-3959(03)00003-3.

- Ley, S., S. Mattiace, and G. Trejo. 2019. “Indigenous resistance to criminal governance: why regional ethnic autonomy institutions protect communities from narco rule in Mexic.” Latin American Research Review 54 (1): 181–200. doi:10.25222/larr.377.

- Lima, R. C., P. F. Silva, and G. Rudzit. 2021. “No Power Vacuum: National Security Neglect and the Defence Sector in Brazil.” Defence Studies 21 (1): 84–106. doi:10.1080/14702436.2020.1848425.

- Loveman, B. 1999. For la Patria: Politics and the Armed Forces in Latin America. Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Magaloni, B., E. Franco-Vivanco, and V. Melo. 2020. “Killing in the Slums: Social Order, Criminal Governance, and Police Violence in Rio De Janeiro.” American Political Science Review 114 (2): 552–572. doi:10.1017/S0003055419000856.

- Mandela, N. B. 2002. World Report on Violence and Health. Geneva: World Health Organisation.

- Mann, M. 2008. “Infrastructural Power Revisited.” Studies in Comparative International Development 43 (3-4): 355–365. doi:10.1007/s12116-008-9027-7.

- Maynard, J. L. 2022. Ideology and Mass Killing: The Radicalized Security Politics of Genocides and Deadly Atrocities. Oxford: OUP.

- Metz, S. 2012. “Rethinking Insurgency.” In The Routledge Handbook of Insurgency and Counterinsurgency, edited by P. Rich, and I. Duyvesteyn, 42–54. London: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203132609.ch3.

- Moncada, E. 2013. “The Politics of Urban Violence: Challenges for Development in the Global South.” Studies in Comparative International Development 48 (3): 217–239. doi:10.11126/stanford/9780804794176.003.0006.

- Mora, F. O. 1996. “Victims of the Balloon Effect: Drug Trafficking and U.S. Policy in Brazil and the Southern Cone of Latin America.” The Journal of Social, Political, and Economic Studies 21 (2): 115.

- Nadelmann, E. A. 1988. “U.S. Drug Policy: A Bad Export.” Foreign Policy 70 (70): 83–108. doi:10.2307/1148617.

- Nadelmann, E. A. 1989. “Drug Prohibition in the United States: Costs, Consequences, and Alternatives.” Science 245 (4921): 939–947. doi:10.1126/science.2772647.

- O’Donnell, G. 1993. “On the State, Democratisation and Some Conceptual Problems: A Latin American View with Glances at Some Postcommunist Countries.” World Development 21 (8): 1355–1369. doi:10.1016/0305-750X(93)90048-E.

- Olson, M. 1993. “Dictatorship, Democracy, and Development.” American Political Science Review 87 (3): 567–576. doi:10.2307/2938736.

- Osorio, J. 2015. “The Contagion of Drug Violence: Spatiotemporal Dynamics of the Mexican War on Drugs.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 59 (8): 1403–1432. doi:10.1177/0022002715587048.

- Padin, J. F. 2022. “Opening Pandora’s Box: The Case of Mexico and the Threshold of Non-International Armed Conflicts.” International Review of the Red Cross, 1–23. doi:10.1017/S1816383122000571.

- Pansters, W. G. 2018. “Drug Trafficking, the Informal Order, and Caciques. Reflections on the Crime-Governance Nexus in Mexico.” Global Crime 19 (3-4): 315–338. doi:10.1080/17440572.2018.1471993.

- Pérez Ricart, C. A. 2020. “Taking the War on Drugs down South: The Drug Enforcement Administration in Mexico (1973–1980).” The Social History of Alcohol and Drugs 34 (1): 82–113. doi:10.1086/707645.

- Phillips, B. J. 2015. “How Does Leadership Decapitation Affect Violence? The Case of Drug Trafficking Organisations in Mexico.” The Journal of Politics 77 (2): 324–336. doi:10.1086/680209.

- Phillips, B. J. 2018. “Terrorist Tactics by Criminal Organisations: The Mexican Case in Context.” Perspectives on Terrorism 12 (1): 46–63.

- Phillips, B. J., and V. Ríos. 2020. “Narco-Messages: Competition and Public Communication by Criminal Groups.” Latin American Politics and Society 62 (1): 1–24. doi:10.1017/lap.2019.43.

- Pion-Berlin, D., and H. Trinkunas. 2011. “Latin America’s Growing Security Gap.” Journal of Democracy 22 (1): 39–53.

- Ramírez-de-Garay, D. 2016. “Las barbas del vecino. Los patrones de difusión del crimen violento en México (1990-2010).” Foro Internacional 56 (4): 977–1018. doi:10.24201/fi.v56i4.2382.

- Reuter, P. 1983. Disorganised Crime: The Economics of the Visible Hand. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Rodiles, A. 2018. “Law and Violence in the Global South: The Legal Framing of Mexico’s ‘NARCO WAR’.” Journal of Conflict and Security Law 23 (2): 269–281. doi:10.1093/jcsl/kry003.

- Rodgers, D., and R. Muggah. 2009. “Gangs as Non-State Armed Groups: The Central American Case.” Contemporary Security Policy 30 (2): 301–317. doi:10.1080/13523260903059948.

- Sartori, G. 1970. “Concept Misformation in Comparative Politics.” American Political Science Review 64 (4): 1033–1053. doi:10.2307/1958356.

- Sassòli, M., and L. M. Olson. 2008. “The Relationship between International Humanitarian and Human Rights Law Where It Matters: Admissible Killing and Internment of Fighters in Non-International Armed Conflicts.” International Review of the Red Cross 90 (871): 599–627. doi:10.1017/S1560775508000072.

- Schedler, A. 2018. En la niebla de la guerra: Los ciudadanos ante la violencia criminal organizada. Mexico: CIDE.

- Serrano, M. 2003. “Unilateralism, Multilateralism, and U.S. Drug Diplomacy in Latin America.” In Unilateralism and U.S. Foreign Policy: International Perspectives, edited by D. M. Malone and Y. Foong Khong, 117–138. London: Lynne Reinner. doi:10.1515/9781685859268-007.

- Shirk, D., and J. Wallman. 2015. “Understanding Mexico’s Drug Violence.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 59 (8): 1348–1376. doi:10.1177/0022002715587049.

- Skinner, Q. 1969. “Meaning and Understanding in the History of Ideas.” History and Theory 8 (1): 3–53. doi:10.2307/2504188.

- Soutou, G.-H. 2014. “How History Shapes War.” In The Oxford Handbook of War. Edited by Boyer, Y. and Lindley-French, J. Oxford: OUP: 43-56. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199562930.013.0004.

- Sullivan, J. P., and A. Elkus. 2008. “State of Siege: Mexico’s Criminal Insurgency.” Small Wars Journal 12 (4): 1–12.

- Sundberg, R., K. Eck, and J. Kreutz. 2012. “Introducing the UCDP Non-State Conflict Dataset.” Journal of Peace Research 49 (2): 351–362. doi:10.1177/0022343311431598.

- Teiner, D. 2020. “Cartel-Related Violence in Mexico as Narco-Terrorism or Criminal Insurgency.” Perspectives on Terrorism 14 (4): 83–98.

- Tilly, C. 1985. “War-Making and State-Making as Organized Crime.” In Bringing the State Back in, edited by P. Evans, D. Rueschemeyer, and T. Skocpol, 169–191. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Trejo, G., and S. Ley. 2020. Votes, Drugs, and Violence: The Political Logic of Criminal Wars in Mexico. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781108894807.

- Trevino-Rangel, J., R. Bejarano-Romero, L. H. Atuesta, and S. Velázquez-Moreno. 2022. “Deadly Force and Denial: The Military’s Legacy in Mexico’s ‘War on Drugs’.” The International Journal of Human Rights 26 (4): 567–590. doi:10.1080/13642987.2021.1947806.

- Ucko, D. H. 2012. “Whither Counterinsurgency: The Rise and Fall of a Divisive Concept.” In The Routledge Handbook of Insurgency and Counterinsurgency, Edited by Rich, P. and Duyvesteyn, I. 77–89. London: Routledge.

- Ucko, D. H. 2013. “Counterinsurgency in El Salvador: The Lessons and Limits of the Indirect Approach.” Small Wars & Insurgencies 24 (4): 669–695. doi:10.1080/09592318.2013.857938.

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). 2019. Global Study on Homicide.

- United Nations Security Council. 2020. “Report of the Secretary-General, United Nations Verification Mission in Colombia.” S/2020/943. Accessed September 16, 2022. https://www.securitycouncilreport.org/atf/cf/%7B65BFCF9B-6D27-4E9C-8CD3-CF6E4FF96FF9%7D/S_2020_943_E.pdf

- Varese, F. 1997. “The Transition to the Market and Corruption in Post-Socialist Russia.” Political Studies 45 (3): 579–596. doi:10.1111/1467-9248.00097.

- Varese, F. 2001. The Russian Mafia: Private Protection in a New Market Economy. Oxford: OUP. doi:10.1093/019829736X.001.0001.

- Varese, F. 2018. Mafia Life: Love, Death, and Money at the Heart of Organized Crime. Oxford: OUP.

- Varsori, A. 2021. “‘The Elite Troops of Trafficking’. An Assessment of the Phenomenon of Military-Trained Gang Members in Rio De Janeiro.” Small Wars & Insurgencies 32 (1): 80–102. doi:10.1080/09592318.2020.1804721.

- Vilalta, C. 2020. “Violence in Latin America: An Overview of Research and Issues.” Annual Review of Sociology 46 (1): 693–706. doi:10.1146/annurev-soc-073018-022657.

- Weber, M. 1946. Weber’s Rationalism and Modern Society. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Weber, M. 1978. Economy and Society: An Outline of Interpretive Sociology. Vol. 1. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Whitehead, N. L., J. E. Fair, and L. A. Payne. 2010. Violent Democracies in Latin America. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Williams, P. “Criminalising the Other: Challenging the Race-Gang Nexus.” Race & Class 56, no. 3 (2015): 18–35. doi:10.1177/0306396814556221.

- Wolf, S. 2009. “El control de pandillas en la relación El Salvador-Estados Unidos.” Foreign Affairs Latinoamérica 9 (4): 85–96.

- Wolf, S. 2010. “Maras Transnacionales: Origins and Transformations of Central American Street Gangs.” Latin American Research Review 45 (1): 256–265.

- Yashar, D. J. 2018. Homicidal Ecologies: Illicit Economies and Complicit States in Latin America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781316823705.