Abstract

This article examines donor-driven skills training programmes and projects at the technical and vocational level in post-war Sierra Leone, using dependency theory as an analytical framework. Based on qualitative data collected from fieldwork in 2017, it emerges that such programmes and projects are driven by donor strategies and largely detached from local market demands, are oftentimes based on convenience and historical relationships in regions/sectors rather than evolving needs of the country, promise employment but instead deliver informal self-employment and focus heavily on outputs rather than outcomes. From these empirical observations, it can be argued that donor-driven skills development, as it has manifested in Sierra Leone, is unlikely to create skills that can meaningfully contribute to national growth and development. Instead, these interventions may drive outcomes that lead to continued aid dependency. The article thus presents a renewed argument for skills for self-reliant development.

Introduction

The expansion in skills development in Sierra Leone has not been matched by an absorption of workers into formal employment, and has been the subject of local media headlines and policy debates. Unemployment, underemployment and engaging in informal work until formal employment becomes available is increasingly common (SSL Citation2019). This is observed alongside employers reporting skills shortages and unfilled vacancies (Darwich Citation2018; Mannah and Gibril Citation2012). The limited absorption of skilled workers into formal employment is not unique to Sierra Leone – see for example Adams (Citation2008) and Fox and Kaul (Citation2018). This observation begs questions on both the demand and supply sides of the labour market. On the demand side, questions relate to constraints faced by firms that affect output and labour demanded. On the labour supply side, questions relating to the right type of workers are pertinent. For example, are workers acquiring skills that are demanded by employers? Can newly trained workers be easily absorbed into formal employment? Is skills training contributing to decent work and reduced precarity for those trained? These questions form the basis of enquiry of the present article.

The analysis specifically focuses on skills development programmes and projects that are funded/supported by and/or implemented by the development community. In so doing, the article problematises these initiatives, highlighting the potential negative, but unintended, consequences of such interventions on individual outcomes, the structure of the labour market and, by extension, wider development goals. These types of interventions require interrogation as they have become increasingly common in many ‘developing’ countries,Footnote1 in a bid to ‘improve’ local conditions and promote economic growth and development – the so-called ‘development project’ (Escobar Citation1995; Hodge Citation2016a, Citation2016b).

The notion of the development project has been widely critiqued and ‘the intellectual and political origins and context of development’ questioned (Hodge Citation2016a, 434). Scholars of critical development studies have argued (among other things) that the notion of development as a singular construct should be re-evaluated to consider its pluralities (Gudynas Citation2016; Hodge Citation2016b), that global institutions entrusted to enhance economic well-being in poorer countries instead use tenets of neoliberalism that deepen and reproduce inequalities (Peet Citation2009), that government elites utilise neoliberal/post-neoliberal development strategies to propagate extractive structures (Merino Citation2020), and that the implementation of aid can disempower local civil society (Szántó Citation2016). Eslava (Citation2015, 91) concludes that the project is itself ‘part of a long-term quest for the effective deployment of authority over territory and population in the Third World’. Others have not interrogated the positioning of international development in the world order or unpacked whether economic growth and development is ‘good’ for developing countries, and instead questioned the results of aid and development initiatives. For example, Easterly (Citation2001) notes that economic growth remained ‘elusive’ after decades of aid financing to developing countries; Moyo (Citation2010) metaphorically categorises aid as ‘dead’ in its ability to improve economic outcomes in Africa; and Chang (Citation2007) argues that the self-interest of Western countries, combined with ignorance of history, has led to bad policy decisions by international development practitioners.

The present article takes a similar approach to the latter group (Chang, Easterly, Moyo) in critiquing the impacts of development programming. It puts forward arguments that question the ability of skills development interventions to deliver on the promise of employment, economic growth and development. In so doing, the impact of such interventions is measured against ‘orthodox’ notions of development outcomes (Martinussen Citation1997; Peet and Hartwick Citation2015). The implication, thus, is not to accept that ‘development’ itself is a global public good, but rather to highlight that even with its best intentions to improve skills, capabilities, human capital and, ultimately, ‘development’, the results are still wanting – even by its own orthodox measures of success. In so doing, the article does not argue for a discontinuation of donor-funded skills training. Instead, it makes a renewed argument for skills for self-reliant development in developing countries, and particularly small low-income countries like Sierra Leone.

The analysis is positioned within a dependency theory framework. According to dependency theorists, interactions between dominant (centre) and dependent (periphery) states reinforce and intensify unequal patterns of economic development (Ferraro Citation2008). Using this lens, the article argues that current manifestations of skills development programmes and projects in Sierra Leone, our case study, likely intensifies these unequal patterns and can result in continued aid dependence.

Although dependency theory had been largely relegated to the sidelines in development studies, international political economy and international relations – often viewed as an ‘outdated, or defunct theoretical approach’ (Márquez Citation2020, 403) – there has been a relatively recent ‘revisiting’ of the theory (Ghosh Citation2019), a bid at ‘restating the relevance of the dependency research programme’ (Kvangraven Citation2021), and an acknowledgement of the ‘continued wisdom of Latin American dependency’ (Márquez Citation2020). Empirically, several scholars have studied Sino–African relations through the lens of dependency theory, interrogating whether these engagements will likely manifest in underdevelopment of African countries or a new form of interdependence (Agbebi and Virtanen Citation2017; Lisimba and Parashar Citation2021; Mason Citation2017). Kvangraven (Citation2021) has similarly used dependency theory to understand contemporary development challenges, drawing on comparative case studies in South Korea and Indonesia. Others have attempted to address broader topics like dependency in a financialised global economy (Musthaq Citation2021). The present article contributes to this recent re-emergence of development analyses that utilise a dependency theory framework.

Skills development at the technical and vocational level did not explicitly feature in the early writings of dependency theorists (Acero Citation1980) – although some made reference to the role of skills in higher education and impacts of brain drain on developing countries (Bhagwati Citation1976); and others to colonial systems of education that were detached from African societies and ultimately underdeveloped Africa’s intellectual resources (Rodney Citation1972). More recent work has looked at the role of donor interventions at tertiary institutions in potentially limiting growth in aid-dependent countries and the attractiveness of development sector jobs among ‘high ability’ skilled workers (Harris Citation2021, Citation2022). Technical and vocational skills training warrants its own analysis as this has been, and continues to be, a key intervention area among donors.

To explore the present topic, Sierra Leone is used as a case study. Sierra Leone provides an apt case study as a small low-income aid-dependent country. Official development assistance to Sierra Leone was an estimated 15% of gross national income in 2019, down from a high of 32% at the end of the civil war in 2002 (World Bank Citation2021). Foreign involvement in skills development in Sierra Leone is also an enduring phenomenon. Previous research has documented the boom in foreign-influenced skills development at the Technical Vocational Education and Training (TVET) and tertiary levels in the post-independence years (Roberts Citation1975). The present article limits the discussion to vocational skills and discusses these interventions in post-war Sierra Leone, as the development sector expanded in this era (Kanyako Citation2016). Importantly, this period (like the post-independence period analysed by Roberts (Citation1975)) was a time of (re)building and developing institutions. As such, skills programmes, and the skills composition that results from them, likely have lasting impacts on Sierra Leone’s development pathway.

The article employs qualitative analysis of interviews and texts. Forty-six interviews with interlocutors from 39 organisations across the private sector, local and international non-governmental organisations (NGOs), donor organisations, and government ministries are analysed. Interviews were conducted between August and December 2017, were semi-structured and averaged about one hour in duration. Participants were selected from a mix of snowball sampling and random calls using information from organisations’ webpages. Additionally, content analysis was applied to documents and texts that detail various skills intervention programmes such as donor and government reports and websites of NGOs and donor organisations. Collectively, 16 large donor-funded skills development programmes/projects are analysed, alongside various smaller projects managed by five NGOs.

The rest of the article is organised as follows. The next section describes the current manifestations of donor-driven skills development in Sierra Leone. Thereafter, the difference between skills development as it currently exists and skills for development which is needed to advance developing countries is explored. This is followed by a discussion on the developmental impacts of donor-driven skills development through the lens of dependency theory. The final section concludes and presents a renewed argument for skills for self-reliant development.

Donor-driven skills development in Sierra Leone

Foreign involvement in Sierra Leonean skills development, like other developing countries, has existed since independence in 1961, with interventions in both vocational and academic areas. Roberts (Citation1975, 345) estimated that 15% of all foreign aid flows in the 10 years succeeding independence was spent on technical assistance, scholarships and fellowships. Flows to TVET in Sierra Leone continued in a similar manner to that of other developing countries up to the 1990s until basic education was prioritised (Matsumoto Citation2018). The 1990s brought the civil war, which disrupted all aspects of the country, including education and skills development. The end of the war in 2002 saw an influx of donors and various training programmes (Kanyako Citation2016), many of which still shape the skills training landscape.

Kanyako (Citation2016, 27) notes that the largesse of aid, too plentiful for the post-war Sierra Leonean government to absorb and manage, led donors to turn to the NGO sector which expanded as aid continued to flow. Low capacity at the time also limited the government’s ability to regulate and monitor donors and NGOs (SSL Citation2014). Although the Sierra Leone Association of NGOs (SLANGO) was established in 1994 with the aim of coordinating NGO activities, its ability to do this was lacking in the post-war years, and still remains weak. It was not until 2008 that the government reacted to the already thriving development sector, by introducing the Non-Governmental Organisations Policy Regulations. The Government of Sierra Leone Aid Policy then followed in 2009. Both aimed to encourage oversight of development programmes operating in the country, although several organisations remain outside government purview according to the most recent national survey of NGOs (SSL Citation2014). The most recent survey is itself instructive as it was completed a decade ago in 2013 and published in 2014. Then, approximately 20% of NGOs surveyed were categorised into the education/training/skills sector (SSL Citation2014, 13).

In the immediate post-war years, a total of 51,122 ex-combatants participated in the Reintegration Opportunity Program under the Disarmament, Demobilisation and Reintegration (DDR) initiative (Sesay and Suma Citation2009, 13). Skills training often entailed short courses (two to three weeks in duration) and comprised vocational skills such as masonry, carpentry, hairdressing and gara tie-dying (Sesay and Suma Citation2009). Training in these types of skills continued to be dominant in many donor programmes in the decade after the war. According to Mannah and Gibril (Citation2012, 13), between 2007 and 2011, development partners such as the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), Irish Aid, the World Bank, the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA), the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (Norad) and Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) supported training an estimated 10,000 youths in TVET areas including tailoring, hair dressing, home management and catering, masonry, refrigeration and air conditioning, metal, welding and fabrication, plumbing, agriculture, carpentry and automotive skills. In addition to the influences from the DDR period, as in other developing countries, there has been evolution in skills development related to shifting donor priorities. For example, the global food crisis in 2008 saw the World Bank inject US$4 million in Sierra Leone to create temporary employment for over 360 cash-for-work projects, which benefitted over 16,000 people (Cubitt Citation2011, 10). More recently, skills development has been coupled with other donor objectives, and now have dual aims of targeting gender equality, poverty alleviation, youths and/or other vulnerable groups.

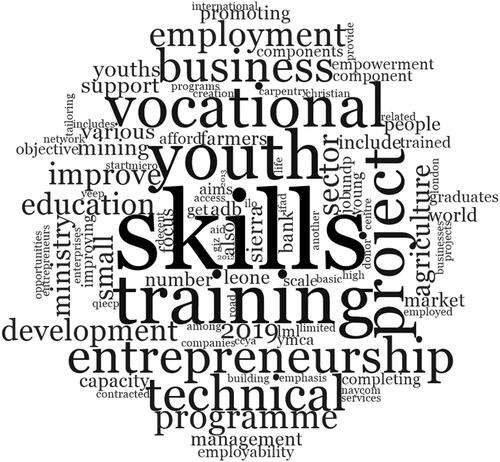

Responses to the interview question posed to donors and NGOs – ‘How has your organisation been involved in skills development in Sierra Leone?’ – together with data from donor reports and web pages is presented in the word cloud in . From , the majority of programmes and projects target youths. Regarding content, ‘vocational’, ‘technical’, ‘entrepreneurship’, ‘business’ and ‘agriculture’ were most commonly cited. Specific to vocational skills, some mentioned carpentry, tailoring, welding, mechanics and hairdressing. Skills for the mining sector were also named, and were mainly supported by GIZ.

Figure 1. Descriptions of skills development programmes and projects in Sierra Leone.

Source: Author’s illustration using data from interviews, donor reports and web pages.

The programmes and projects that inform range from 2010 (for example the ILO’s Quick Impact Employment Creation Project and the World Bank’s Youth Employment Support Project), up to those that were either in the pipeline or being implemented at the time of fieldwork in 2017.Footnote2 Some pipeline projects in 2017 are now in the implementation phase at the time of writing – for example the African Development Bank’s (AfDB) Youth Entrepreneurship and Employment Project and the World Bank’s Skills Development Project. GIZ’s Employment Promotion Programme was in the third phase, with the first phase having started in 2005. Each of these projects/programmes attempts to improve employability by improving skills and capabilities among beneficiaries – usually youths. Some, such as the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD)’s Smallholder Commercialisation Programme and the then-Department for International Development (DFID)-funded Sierra Leone Opportunities for Business Action, specifically target skills development for the agriculture sector.Footnote3 Others attempt to align skills training objectives with entrepreneurship promotion – for example, two projects by the AfDB (Youth Entrepreneurship and Employment Project and Enable Youth), the then-DFID funded Business Bomba, the International Finance Corporation (IFC)’s Business Edge Trainer, and the EU-supported Decent Work Programme. These interventions were often implemented through government agencies like the National Youth Commission, and/or local or international NGOs. Various local NGOs also provided skills training which were funded through small donations. For example, Sierra Leone Grass Roots Agency, a small local NGO, pooled funding from various small international donors to run vocational skills training in areas like carpentry and tailoring.Footnote4

At the policy level, donors have come together to form the National Technical Vocational Coalition. GIZ has been a key player in this area, organising stakeholder meetings and, more tangibly, funding the ‘Skills needs assessment initiative of the TVET coalition of Sierra Leone’. The AfDB financed the TVET Image Campaign under the Youth Entrepreneurship and Employment Programme. According to informants, however, representatives from the government had not driven the process, and few private-sector companies were involved.Footnote5 The absence of government and the private sector from the table arguably affects the coalition’s ability to promote skills that might be most relevant to the local labour market and consistent with the policy direction of the government.

The programmes and projects analysed here are unlikely to be an exhaustive list. Several respondents noted that in addition to direct funding for skills development programmes, funds also flow to third-party organisations under private-sector development initiatives, which indirectly influence skills development.Footnote6 The data, however, capture the main/large donors in Sierra Leone, alongside a collection of smaller NGO projects. It is therefore a reasonable illustration of the skills development landscape over the past decade (2010–2020) from which key emerging patterns can be analysed.

Skills development versus skills for development

From the 46 interviews and analysis of documents and texts, four key themes emerge that characterise donor practices in funding/delivering skills development. The four themes are: (1) programming based on donor strategies over local labour market needs, (2) targeting based on convenience, (3) unmet promises of employment and (4) a substantial focus on outputs rather than outcomes. Collectively, these emergent issues bring into question whether skills development has been too distant from skills for development. The latter is concerned with equipping the labour force with skills that can meaningfully contribute to livelihoods, the economy and wider development goals. The inability of skills development interventions to meaningfully contribute to local development in turn has implications for continued aid dependence.

Donor wants versus local labour market needs

The need for skills development in Sierra Leone is not contested (Darwich Citation2018; Mannah and Gibril Citation2012). From the qualitative data collected in this study, most employers reported a skills gap and donors noted the current skills deficit as the motivation for their programmes and/or projects. However, there is a mismatch between skills training provided by donor initiatives on the supply side, and the skills needed by companies on the demand side. Based on interviews, the technical skills gap is still a major issue in Sierra Leone, and one that has persisted despite interventions. A national study revealed that as a share of total employment in each sector, unmet demand was 52.1% in the agriculture sector, 59.2% in the mining sector and 50.8% in the tourism sector (Mannah and Gibril Citation2012, 26–30). In addition to technical skills, recruiters also noted deficiencies in soft skills such as communication skills, worker motivation and being a team player.Footnote7 Darwich’s (Citation2018) study supports these findings, and highlights similar technical and soft skills deficiencies. These skills gaps persist despite decades of skills training interventions.

One factor contributing to this mismatch is the funding/implementation of training based on donor priorities. Interlocutors from four of the largest donor organisations noted that their programmes were often selected in accordance with ‘global strategies’ or priorities and determined by offices headquartered in (distant western) donor countries.Footnote8 Local NGOs are then used to implement these training priorities, functioning as agents of the donors, or ‘compradors’ in the terminology of Hearn (Citation2007). Three salient quotes from two NGOs and a donor organisation give voice to this:

We started just after the war and mainly work with youths. We get funding from the EU, UNDP, UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation), Government of Finland, US State Department, Bureau of Peace and Open Society Initiative. Our programmes are based on our strategic plan. We set our objectives to be aligned with our donor objectives.Footnote9

We are small. We run training centres in the provinces on technical skills like carpentry, tailoring. Also, capacity building of farming groups. Our donors are interested in these areas. We don’t have big donors. We have many small international donors.Footnote10

Renewables were encouraged because of the Africa Renewable Programme from head office. Agriculture also became a dominant sector as this links with the ‘making markets work for the poor’ strategy.Footnote11

Convenient choices

In addition to global strategies, many decisions on places and sectors of intervention were driven by convenience. As noted, several recent manifestations of vocational skills training by development partners trace back to the DDR initiative in post-war Sierra Leone. Enria (Citation2014) notes that contemporary programmes were often chosen based on what was previously done, hence the proliferation of DDR-style training. Data from this study reinforce Enria’s (Citation2014) arguments and reveal convenient choices by donors. Such convenient choices may not necessarily be correlated with the highest need, or the highest potential benefits. According to one respondent from one of the largest donor-funded employment programmes being implemented in 2017: ‘The [programme name omitted] works in Kono, Koinadugu and Kailahun. This is mainly for historical reasons as Kono and Koinadugu were affected by the war. I guess we stayed there a while so it’s comfortable now’.Footnote12 Selecting locations and skills training based on experience and convenience is rational and strategic at the donor level. In principle, working in familiar contexts using tried and tested methods increases the probability of being successful. However, this approach is unresponsive to changes in the needs of the country. Moreover, as discussed below, notions of success can also be debated.

Another example of convenient choices relates to decisions that fit donor funding cycles, although these decisions may be sub-optimal. In response to questions around why agriculture was the chosen focal sector, a staff member from another donor organisation noted: ‘We did a survey which identified agriculture, light manufacturing and renewables. Light manufacturing had the biggest need but required longer-term investment that the project could not make with the funding cycle. So, we went for agriculture and renewables’.Footnote13 This speaks to a wider issue of short-term donor programming alongside long-term engagement – an issue that has been argued to increase the risks of distracting attention, resources, and efforts away from sustainable development (Gulrajani and Calleja Citation2019). Such short-term programming has been identified as a challenge to achieving development objectives, and appears to be persistent or even increasing in international development (Gonsior and Klingebiel Citation2019).

The promise of employment

Most donors named employment as the key outcome of their initiative. This is unsurprising given programme and project names such as ‘Youth Entrepreneurship and Employment Project’, ‘Employment Promotion Programme’, ‘Quick Impact Employment Creation Project’, ‘Youth Employment Empowerment Programme’ and ‘Youth Employment Support Project’. However, it emerges that employment often relates to self-employment, as the notion of ‘employment creation’ is a common denominator across many programmes/projects. Integration into the formal labour market is often secondary to developing agricultural skills to engage in small-scale farming or TVET combined with business skills (and sometimes a small amount of start-up capital) to establish a small sewing business, or mechanic shop, for example. According to two of the main donors and a senior government representative:

The new Private Sector Development Plan will focus on jobs and incomes. We hope to use livelihood programming to boost returns to self-employment.Footnote14

Our programme is really self-employment in rural settings through agriculture. We promote labour within agriculture. So, it’s not just general employment but agriculture sector employment.Footnote15

Most people are in the informal sector just for survival. They are not trained in management, bookkeeping, financial literacy. The programme provides training and links the beneficiaries to financial institutions. We hope to make self-employment more sustainable.Footnote16

In 2011/2012 the skills mismatch became apparent with the mining boom. Jobs were being created in the mining sector during the boom, but mining companies were bringing in front-end tractor drivers from Ghana. Our skills training programme had not been structured to respond to this.Footnote17

Outputs versus outcomes

As noted, the objective is often employment and/or self-employment. However, many donor-funded skills development interventions in Sierra Leone measure success by the numbers of beneficiaries trained, and not numbers gainfully employed. Both publicly funded and donor-financed projects often utilise results frameworks/matrices – underscored by an assumed theory of change – that link inputs to activities to outputs to outcomes to achieving the overall project objectives (Roberts and Khattri Citation2012). According to these types of results frameworks, outputs are the products generated from an intervention, while outcomes are changes that result from the intervention (Roberts and Khattri Citation2012). Outputs fall under the control of the programme or project implementer, whereas outcomes result from the interaction between outputs and the wider environment. Applying this framework to skills development, an example of an output is the number of beneficiaries trained, whereas changes in employment status or wages of beneficiaries are examples of outcomes.

Palmer (Citation2014) reviews development policy on TVET since 1990 and contends that one of the biggest issues was the vague definition of goals related to skills development, and the resultant ambiguity in their measurement. Palmer (Citation2014) argues that addressing this ambiguity would increase the probability of developmental gains from skills training. Evaluating a similar time period of TVET policy, Johanson and Adams (Citation2004, 11) conclude that since non-government training institutions and enterprises accounted for most of Sub-Saharan African’s skills training capacity, a more coordinated reform framework with a clear focus on results is needed. The 2005 Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness aimed to overcome some of these challenges and promote joint ownership with clear results. However, there is tension between the tenets of the declaration and the realities of aid implementation (Monye, Ansah, and Orakwue Citation2010; Sjöstedt Citation2013).

Limited focus on results manifests in Sierra Leone as there is little to no follow-up with beneficiaries to understand their outcomes, despite the reported emphasis on employment/self-employment. Lack of follow-up indicates that the impact on employment outcomes of those trained is unclear. Of the 16 large donor programmes/projects analysed, only two reported tracing outcomes. The ‘Mines to Minds’ projects reported that employment outcomes were tracked,Footnote22 and the World Bank has conducted a systematic impact assessment for the 2010–2015 Youth Employment Support Project. The former was unable to provide results on outcomes at the time of data collection as this was still being analysed. For the World Bank project, the results show that those trained were 3.1% more likely to be employed, and 4.1% more likely to be a first-time entrepreneur (Rosas, Acevedo, and Zaldivar Citation2017, 13–14). The employment effect (3.1%) is smaller than that found in many other studies conducted in developing countries (McKenzie Citation2017, 131–132). The results are also unlikely to be generalisable to other skills development interventions in Sierra Leone as elements of selection bias were likely present (Rosas, Acevedo, and Zaldivar Citation2017). In addition to this, little can be said on long-term effects given the short follow-up period of six months. Insufficient focus on results may in part be influenced by limited government capacity to effectively regulate the sector. The consequence is self-regulation and self-monitoring by development organisations, which as the data suggest, may result in skills development without skills for development.

The developmental impacts of donor-driven skills development through the lens of dependency theory

The qualitative data suggest that donor-driven skills development, as it has manifested in Sierra Leone, is unlikely to create skills that can meaningfully contribute to national growth and development. This results from a mismatch between skills that are developed through donor-driven training and local labour market needs, with beneficiaries of training failing to secure employment and/or remaining in the precarious informal sector. The data suggest that the mismatch between donor-driven skills development and local labour market needs stem from two channels. The first is the way programmes and projects are selected – primarily informed by donor priorities and existing donor relationships and expertise rather than labour market demands. The second is the way programmes and projects are implemented – mainly geared towards self-employment and informal work, with success measured by numbers trained rather than employment outcomes. It can be argued that employment opportunities may indeed be limited in contexts like Sierra Leone. However, interviews with employers in this study as well as previous documented evidence (Darwich Citation2018; Mannah and Gibril Citation2012) indicate that there is still unmet labour demand alongside a plethora of skills training. Using dependency theory as a guiding framework, the rest of this article explores the possible developmental impacts of such interventions.

The ideas at the foundation of dependency theory were first proposed in the late 1950s by Raul Prebisch and colleagues, who were concerned by the divergent growth patterns between advanced industrialised countries and poorer countries (firstly in Latin America), contrary to predictions of classical economic theories and theories of modernisation (Ferraro Citation2008). Since then, dependency theory has been influenced by many scholars and has evolved over time (Ferraro Citation2008; Ghosh Citation2019; Martinussen Citation1997). What has remained fundamental to the theory is that interactions between ‘dominant’ developed countries and ‘dependent’ developing states reinforce and intensify unequal patterns of economic development. This understanding is most akin to Sunkel’s (Citation1969) conceptualisation of dependency as an explanation of the economic development of a country in relation to external influences on national development – be they political, economic and/or cultural influences. Unlike some perspectives that critique the concept of the development project (Eslava Citation2015; Escobar Citation1995; Gudynas Citation2016; Hodge Citation2016a, Citation2016b; Merino Citation2020), dependency theory does not challenge the notion of ‘development’, but instead challenges the interaction between ‘advanced’ and ‘developing’ countries.

Martinussen (Citation1997, 89) further notes that being ‘under-developed’ according to dependency theory is ‘a process and not a state’. The rest of this article argues that donor-driven skills interventions set in motion a process of change in the labour market that can negatively affect national development in recipient countries like Sierra Leone. In so doing, the recipient country can become more dependent on aid, perpetuating a vicious cycle of dependency. Specific to skills interventions there are three mechanisms that can drive this process: (1) continued informality in the labour market, (2) precarious employment and the risk of violence/conflict and (3) emphasis on sectors that may not sufficiently drive economic growth and development.

Continued informality

Many trainees in Sierra Leone end up in self-employment after training, because (1) there is a disconnect between donor wants and labour market needs, (2) local companies do not recognise donor-driven training, and/or (3) programmes/projects are specifically geared towards entrepreneurship training. In all cases, the result is an expansion, or at the very least no change, in the informal sector. Informality here refers to ‘the collection of firms, workers, and activities that operate outside the legal and regulatory systems’ (Loayza Citation2016, 2). The most recent Sierra Leone integrated household survey reveals that 86% of employment is informal (SSL Citation2019). This is consistent with estimates that self-employment in Sierra Leone has remained at about 90% between 1991 and 2019 (World Bank Citation2021).

Although neoliberal scholars in the 1950s and 1960s often diverged in views from Marxist writers in the 1970s, both groups saw little potential for independent growth from the informal sector and the informalisation of labour (Meagher Citation1995). Arguments imbedded in both perspectives were based on assumptions that the informal sector (1) is transitory and would be transformed with so-called modernisation, (2) only leads to subsistent activities and incomes, and, related to the first assumption, (3) is largely a feature of ‘peripheral economies’ – using the terminology of dependency theory (Meagher Citation1995, 261). The neoliberal view shifted in the 1970s under the influence of the International Labour Organization (ILO) and later the World Bank, which characterised the informal sector as ‘an indigenous entrepreneurial dynamism suggesting a potential for employment creation and growth’ (Meagher Citation1995, 262). Recent evidence suggests that informality – and specifically involuntary informality – contributes little to growth and development, for a number of reasons.Footnote23

First, both La Porta and Shleifer (Citation2014) and Loayza (Citation2016) accurately note that informal employment provide livelihoods for billions in developing countries, but also argue that such informality arises out of poverty and that the informally self-employed have low productivity and produce low-quality products. Such informal production is often ‘small, unproductive and stagnant’ (La Porta and Shleifer Citation2014, 112), and therefore contributes little to economic growth in comparison to the formal sector.

Second, from a public finance perspective, high levels of informality imply lower levels of government tax revenue. Given that informal firms are outside the regulatory framework, they can avoid taxes on labour and profits (Loayza Citation2016). This is one reason why developing countries collect between 10 and 20% of gross domestic product (GDP) in taxes, while the average high-income country collects about 40% of GDP (Besley and Persson Citation2014). Low tax collection in turn limits the ability of the government to fund infrastructure and social spending that are necessary for national development.

Third, poverty is strongly associated with informality (Kanbur Citation2017). As noted by La Porta and Shleifer (Citation2014), those who are poorer are more likely to enter the informal sector. However, it can also be argued that poverty can be a consequence of informality as those in the informal sector often have low and insecure earnings. Kanbur (Citation2017, 951) terms this the ‘informality–poverty trap’, where ‘informality causes poverty, and in turn poverty leads to informality’. Further to this, informality has also been associated with inequality (Chong and Gradstein Citation2007), with additional implications for gender equality as evidence suggests women are more likely to be informally employed (Kanbur Citation2017). In Sierra Leone, 92% of women are reported to be in vulnerable employment in comparison to 80% of men (Danish Trade Union Development Agency (DTDA)) Citation2020, 17).

Collectively, continued informality can reinforce dependency as developing countries that have little/low economic growth, low levels of tax collection and higher levels of poverty are more likely to receive aid, as aid often explicitly targets these challenges.

Precarious employment and the risk of violence/conflict

Continued informality has several negative economic consequences, as discussed above. In addition to this, the relationship between precarious employment and the risk of violence/conflict needs special consideration.Footnote24 According to one respondent from the National Youth Commission in Sierra Leone:

Unemployment, low paid self-employment – this used to be about the uneducated average Joe. Now we have graduates and people who are trained either unemployed or doing these little jobs. It is a threat to security. A young person can easily be radicalised with US$500 after having small small income for five, six years.Footnote25

Several scholars have theorised about the link between labour market prospects (mainly unemployment) among youths (often young men) and the emergence of violence, with the term ‘youth bulge’ featuring heavily in the literature (Cincotta, Engelman, and Anastasion Citation2003; Hoffman Citation2011). Empirically, cross-country evidence supports this. Using a sample of 24 developing countries spread across geographical regions, Azeng and Yogo (Citation2013) show that youth unemployment is associated with increased risk of political instability, especially in contexts where there is social inequality and corruption. Research from Sierra Leone shows that it is not only unemployment that matters, but precarious employment as well, and that the latter correlates with the proclivity for engaging in political violence. In particular, young men in precarious low-income employment use violence as a tactic to signal loyalty to political strongmen (Enria Citation2015). In a highly networked society, signalling such loyalty is one strategy aimed at establishing relations of reciprocity with the ultimate hope that the relationship will offer a path to socially valued employment (Enria Citation2015).

As noted, the only skills development intervention assessed here that tracked employment reported that those trained were a mere 3.1% more likely to be employed (Rosas, Acevedo, and Zaldivar Citation2017). The others did little tracking of employment outcomes, instead focussing on outputs like numbers trained, and several designed programmes/projects which facilitated self-employment in the informal sector. If skills interventions have a low probability of meaningfully reducing precarious employment and boosting prospects of secure decent work, the ability of these interventions to positively contribute to maintaining peace in post-conflict settings can be questioned. This in turn relates to continued aid dependency as countries that either are in conflict or have recently emerged from conflict are more likely to rely on foreign aid (UNCTAD Citation2019, 19).

Sectoral choice and implications for economic growth and development

In addition to the explicit focus on entrepreneurship, and the sometimes unintended influence on informalisation, emphasis has been placed on the agriculture sector by many donor initiatives in Sierra Leone. This raises the question: is this the best sector to target as a panacea for development? And, in particular, a less dependent style of development?

Traditional arguments in favour of targeting the agriculture sector relate to food security, generating income and employment for poor rural farmers, reducing urban–rural inequalities, and fostering structural transformation of the economy (Dethier and Effenberger Citation2012). Albeit, how the agriculture sector is targeted matters. A focus on subsistence farming – which many of the agriculture skills training programmes in Sierra Leone target, arguably engenders and further promotes a subsistence economy, where rural farmers continue to subsist with little commercialisation of output and a lack of integration into value chains, with many barely existing above the poverty line (Kolade, Mafimisebi, and Aluko Citation2020; Singh-Peterson and Iranacolaivalu Citation2018). On the other hand, developing an agriculture sector aimed at export markets can reinforce unequal exchange as argued by early dependency theorists like Arghiri Emmanuel, where countries export relatively cheap raw material and then import expensive manufactured products (Martinussen Citation1997); or, more fundamentally, export-driven agriculture can erode traditional practices as countries attempt to comply with western standards (Rodney Citation1972).

In more contemporary discourse, there is a general scepticism among many about the ability of subsistence and semi-subsistence agriculture to meaningfully drive growth in African countries. Ha-Joon Chang has long called for industrial policy and manufacturing-led growth that generates employment, provides value addition and promotes export earnings (Chang Citation2007). Historically, rapid growth in both developed and developing countries – particularly fast-growing developing countries in Asia – has been driven by industrialisation (Chang Citation2007). This is not to say that agriculture serves no purpose in the developmental process. However, for the purpose of skills development that aims to enhance development prospects in recipient countries, training should be better targeted at equipping the workforce with technical skills for high-growth sectors, and in areas where there is labour demand. In fact, in Sierra Leone the skills gap reported in the formal agriculture sector was an estimated 52.1% of all employment among agriculture sector companies (Mannah and Gibril Citation2012, 26–30), but workers trained by donor programmes/projects could not be easily absorbed into these roles. Moreover, as noted above, there is unmet skills demand in the manufacturing sector in Sierra Leone as many employers continue to report basic technical skills shortages. It is only in targeting these high-growth sectors that countries like Sierra Leone can become less aid dependent.

Concluding remarks

This article examined donor-driven skills training at the technical and vocational level in post-war Sierra Leone. Emerging themes suggest that such skills training programmes and projects are largely detached from local market demands and instead driven by donor strategies, are oftentimes based on convenience and historical relationships in regions/sectors rather than evolving local needs, promise employment but instead deliver informal self-employment and focus heavily on outputs rather than outcomes. From these empirical observations, it can be argued that donor-driven skills development, as it has manifested in Sierra Leone, is unlikely to create skills that can meaningfully contribute to national growth and development. The reasons for the hypothesised disconnect between skills training and national development stems from the tendency of skills development initiatives to promote continued informality and precarious employment, and the failure to target employment generation in high-growth sectors. When assessed through the lens of dependency theory and drawing on various studies related to informality and growth, youth unemployment and conflict, and agriculture and development, it can be argued that these interactions can set countries like Sierra Leone on a path of continued aid dependence.

The article takes the centre–periphery/dominant–dependent framing in its application of dependency theory, with the country as the main unit of analysis. This framing usefully allows skills training interventions to be assessed, but says little about the nature of relationships between donors, the government and local NGOs during implementation. Arguably, in a resource-constrained setting like Sierra Leone with a government unable to effectively regulate development organisations, donors enjoy a great degree of power to shape the policy space – for example, promoting TVET as a strategy in Sierra Leone, which the government may then adopt as a result of inertia, lack of capability to deviate, or compliance with donor priorities. Donor funding of skills development may also crowd out government spending in these areas. This could then lead to continued reliance on donors to provide skills training, accompanied by low government capacity to drive TVET and other non-academic pathways. Another layer of analysis lies in the local NGO sector, which often implements donor-funded training. Hearn’s (Citation2007) critique of using and over-using local NGOs to do donors’ bidding can be applied here. In the long run, the use and over-use shifts local civil society away from its origins and, as Szántó (Citation2016) argues, can lead to disempowerment in Sierra Leone.

In highlighting these important issues, the article does not argue for a discontinuation of donor-funded skills training. Instead, it makes a renewed argument for skills for self-reliant development in developing countries, and particularly small low-income countries like Sierra Leone. In 1980, Liliana Acero wrote: ‘In the context of dependent societies, skills for self-reliance are skills for transformation’ (Acero Citation1980, 385). This notion still holds true today and remains ever important as donors continue to spend on skills training. A first step in developing transformative skills is ensuring training interventions are useful and valued in the labour market. This requires programmes and projects to be aligned with national development priorities (and not primarily driven by donor priorities), but also for the formal private sectors to be actively involved in developing skills training programmes/projects, which can increase the likelihood of workers being absorbed into the formal productive workforce. In the absence of this, skills training alone is unlikely to facilitate self-reliant development.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (18.2 KB)Acknowledgements

This work would not have been possible without financial support from the International Growth Centre (IGC) – project number 39408. I extend a special thank you to my research participants who gave of their time. I am also grateful for comments and feedback from Christopher Adam, Andy McKay, Martin Williams and Alex Jones, and to the taxpayers of Trinidad and Tobago, who funded my doctoral studies.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Jamelia Harris

Jamelia Harris is Research Fellow at the Institute for Employment Research, University of Warwick. Her research focuses on aid and the labour market in developing countries, skills mismatch, the education-to-work transition, and how political/economic institutions affect job search and labour market outcomes. She holds a DPhil in international development from the University of Oxford.

Notes

1 According to data from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), between 2009 and 2018, developed countries spent US$126 billion on education and training-related activities in developing countries, or an estimated US$20 per person. Issues related to skills are subsumed in the eighth sustainable development goal (SDG 8) – decent work for all, and of all interventions listed in the International Labour Organisation (ILO)’s Youth Employment Program Inventory database, 82% are training programmes (Fox and Kaul Citation2018, 9).

2 See Table S1 of the supplemental material for more details on the programmes and projects analysed.

3 DFID has since been rebranded as the Foreign Commonwealth and Development Office. ‘DFID’ is still used here as this was the funding body at the time of data collection.

4 Interview, Director of local NGO 1, Freetown, 12 September 2017.

5 Interview, Advisor at donor organisation 1, Freetown, 13 September 2017; Interview, Managing Director of recruitment company 1, Freetown, 5 October, 2017; Interview, National Capacity Building Advisor at donor organisation 1, Freetown, 5 October 2017.

6 Interview, Director of local NGO 2, Freetown, 26 September 2017.

7 Interview, Managing Director of recruitment company 1, Freetown, 5 October 2017.

8 Interview, Advisor at donor organisation 1, Freetown, 13 September 2017; Interview, Programme Officer at donor organisation 2, Freetown 8 September 8, 2017; Interview, Deputy Programme Coordinator at donor organisation 2, Freetown 8 September 8, 2017; Interview, Economist at donor organisation 3, Freetown, 17 September 2017; Interview, Project Officer at donor organisation 4, Freetown, 4 December 2017.

9 Interview, Director of local NGO 3, Freetown, 12 September 2017. Text in the parentheses have been added to aid the reader.

10 Interview, Director of local NGO 1, Freetown, 12 September 2017.

11 Economist at donor organisation 3, Freetown, 17 September 2017.

12 Interview, Deputy Programme Coordinator at donor organisation 1, Freetown, 11 September 2017.

13 Economist at donor organisation 3, Freetown, 17 September 2017.

14 Ibid.

15 Interview, Deputy Programme Coordinator at donor organisation 1, Freetown, 11 September 2017.

16 Interview, Programme Officer at National Youth Commission, Freetown, 18 August 18, 2017.

17 Interview, Programme Officer at donor organisation 2, Freetown, 8 September 2017.

18 Ibid.; Interview, Founder and Chief Executive Officer of mining company, Freetown, 23 November, 2017.

19 Interview Human Resource Manager of manufacturing company, Freetown, 13 September 2017;

Interview, Human Resource Manager of logistics company, Freetown, 29 September 2017;

Interview, Chief Financial Officer of engineering company, Freetown, 30 September 2017;

Interview, Head of construction company, Freetown, 30 September 2017; Interview, Human Resource Director of telecommunications company, Freetown, 3 October 2017.

20 Interview, Advisor at donor organisation 1, Freetown, 13 September 2017; Interview, Founder and CEO of mining company, Freetown, 23 November, 2017.

21 Interview, Deputy Programme Coordinator at donor organisation 1, Freetown, 11 September 2017; Interview, Project Manager at international NGO, Freetown, 18 September 2017.

22 Interview, Advisor at donor organisation 1, Freetown, 13 September 2017.

23 The arguments may be different for voluntary self-employment. See Maloney (Citation2004) for a discussion on this.

24 It is recognised that the emergence of political violence and conflict can be linked to a multitude of causes or ‘stress factors’ – see discussions in Cincotta, Engelman, and Anastasion (Citation2003). The argument here is not to reduce the importance of other contributors, but instead to highlight the role of labour market factors.

25 Interview, Programme Officer at National Youth Commission, Freetown, 18 August 2017.

Bibliography

- Acero, L. 1980. “Workers’ Skills in Latin America: An Approach towards Self-Reliant Development.” Development and Change 11 (3): 367–389. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7660.1980.tb00075.x.

- Adams, A. V. 2008. Skills Development in the Informal Sector of Sub-Saharan Africa. Washington, DC: World Bank. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/206591468008460175/Skills-development-in-the-informal-sector-of-Sub-Saharan-Africa

- Agbebi, M., and P. Virtanen. 2017. “Dependency Theory – A Conceptual Lens to Understand China’s Presence in Africa?” Forum for Development Studies 44 (3): 429–451. doi:10.1080/08039410.2017.1281161.

- Azeng, T. F., and T. U. Yogo. 2013. “Youth Unemployment and Political Instability in Selected Developing Countries.” African Development Bank Group Working Paper Series No. 171. Tunis: African Development Bank.

- Besley, T., and T. Persson. 2014. “Why Do Developing Countries Tax So Little?” Journal of Economic Perspectives 28 (4): 99–120. doi:10.1257/jep.28.4.99.

- Bhagwati, J. N. 1976. “Taxing the Brain Drain.” Challenge 19 (3): 34–38. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40719435. doi:10.1080/05775132.1976.11470220.

- Chang, H.-J. 2007. Bad Samaritans: The Guilty Secrets of Rich Nations and the Threat to Global Prosperity. London: Random House; New York: Bloomsbury USA.

- Chong, A., and M. Gradstein. 2007. “Inequality and Informality.” Journal of Public Economics 91 (1-2): 159–179. doi:10.1016/j.jpubeco.2006.08.001.

- Cincotta, R. P., R. Engelman, and D. Anastasion. 2003. The Security Demographic: Population and Civil Conflict after the Cold War. Washington, DC: Population Action International.

- Cubitt, P. C. 2011. “Employment in Sierra Leone: What Happened to Post-Conflict Job Creation?” African Security Review 20 (1): 2–14. doi:10.1080/10246029.2011.561007.

- Danish Trade Union Development Agency (DTDA). 2020. “Labour Market Profile Sierra Leone – 2020.” Copenhagen. https://www.ulandssekretariatet.dk/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/LMP-Sierra-Leone-2020.pdf

- Darwich, M. 2018. Skills Needs Assessment Initiative of the TVET Coalition of Sierra Leone. Freetown, Sierra Leone: Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH.

- Dethier, J.-J., and A. Effenberger. 2012. “Agriculture and Development: A Brief Review of the Literature.” Economic Systems 36 (2): 175–205. doi:10.1016/j.ecosys.2011.09.003.

- Easterly, W. R. 2001. The Elusive Quest for Growth: Economists’ Adventures and Misadventures in the Tropics: Economists Adventures and Misadventure in the Tropics. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Escobar, A. 1995. Encountering Development: The Making and Unmaking of the Third World. STU-Student ed. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

- Eslava, L. 2015. Local Space, Global Life: The Everyday Operation of International Law and Development. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9781316135792.

- Enria, L. 2014. Real Jobs in Fragile Contexts: Reframing Youth Employment Programming in Liberia and Sierra Leone. London: International Alert.

- Enria, L. 2015. “Love and Betrayal: The Political Economy of Youth Violence in Post-War Sierra Leone.” The Journal of Modern African Studies 53 (4): 637–660. doi:10.1017/S0022278X15000762.

- Ferraro, V. 2008. “Dependency Theory: An Introduction.” In The Development Economics Reader, edited by G. Secondi, 58–64. London: Routledge.

- Fields, G. S. 2011. “Labor Market Analysis for Developing Countries.” Labour Economics 18:S16–S22. doi:10.1016/j.labeco.2011.09.005.

- Fox, L., and U. Kaul. 2018. “The Evidence Is in: How Should Youth Employment Programs in Low-Income Countries Be Designed?” World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 8500. Washington, DC: World Bank. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/837861530219586540/The-evidence-is-in-how-should-youth-employment-programs-in-low-income-countries-be-designed

- Ghosh, B. N. 2019. Dependency Theory Revisited. London: Routledge.

- Gonsior, V., and S. Klingebiel. 2019. “The Development Policy System under Pressure: Acknowledging Limitations, Sourcing Advantages and Moving towards a Broader Perspective.” German Development Institute Discussion Paper No. 6/2019. Bonn: German Development Institute. doi:10.23661/dp6.2019.

- Gudynas, E. 2016. “Beyond Varieties of Development: Disputes and Alternatives.” Third World Quarterly 37 (4): 721–732. doi:10.1080/01436597.2015.1126504.

- Gulrajani, N., and R. Calleja. 2019. “Understanding Donor Motivations: Developing the Principled Aid Index.” ODI Working paper 548. London: Overseas Development Institute https://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/resource-documents/12633.pdf

- Harris, J. 2021. “Foreign Aid, Human Capital Accumulation and the Potential Implications for Growth.” The Review of International Organizations 16 (3): 549–579. doi:10.1007/s11558-020-09408-8.

- Harris, J. 2022. “Occupational Preferences of Skilled Workers in the Presence of a Large Development Sector.” The Journal of Development Studies, 1–18. doi:10.1080/00220388.2022.2139605.

- Hearn, J. 2007. “African NGOs: The New Compradors?” Development and Change 38 (6): 1095–1110. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7660.2007.00447.x.

- Hodge, J. M. 2016a. “Writing the History of Development (Part 1: The First Wave).” Humanity: An International Journal of Human Rights, Humanitarianism, and Development 6 (3): 429–463. http://humanityjournal.org/issue6-3/writing-the-history-of-development-part-1-the-first-wave/ doi:10.1353/hum.2015.0026.

- Hodge, J. M. 2016b. “Writing the History of Development (Part 2: Longer, Deeper, Wider).” Humanity: An International Journal of Human Rights, Humanitarianism, and Development 7 (1): 125–174. http://humanityjournal.org/issue7-1/writing-the-history-of-development-part-2-longer-deeper-wider/ doi:10.1353/hum.2016.0004.

- Hoffman, D. 2011. The War Machines: Young Men and Violence in Sierra Leone and Liberia. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Johanson, R. K., and A. V. Adams. 2004. “Skills Development in Sub-Saharan Africa.” Regional and Sectoral Studies 28820. Washington, DC: World Bank. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/15028

- Kanbur, R. 2017. “Informality: Causes, Consequences and Policy Responses.” Review of Development Economics 21 (4): 939–961. doi:10.1111/rode.12321.

- Kanyako, V. 2016. “Donor Policies in Post-War Sierra Leone.” Journal of Peacebuilding & Development 11 (1): 26–39. doi:10.1080/15423166.2016.1146035.

- Kolade, O., O. Mafimisebi, and O. Aluko. 2020. “Beyond the Farm Gate: Can Social Capital Help Smallholders to Overcome Constraints in the Agricultural Value Chain in Africa?.” In The Palgrave Handbook of Agricultural and Rural Development in Africa, edited by E. S. Osabuohien, 109–129. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-41513-6_6.

- Kvangraven, I. H. 2021. “Beyond the Stereotype: Restating the Relevance of the Dependency Research Programme.” Development and Change 52 (1): 76–112. doi:10.1111/dech.12593.

- La Porta, R., and A. Shleifer. 2014. “Informality and Development.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 28 (3): 109–126. doi:10.1257/jep.28.3.109.

- Lisimba, A. F., and S. Parashar. 2021. “The ‘State’ of Postcolonial Development: China–Rwanda ‘Dependency’ in Perspective.” Third World Quarterly 42 (5): 1105–1123. doi:10.1080/01436597.2020.1815527.

- Loayza, N. V. 2016. “Informality in the Process of Development and Growth.” World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 7858. Washington, DC: World Bank. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/25303

- Maloney, W. F. 2004. “Informality Revisited.” World Development 32 (7): 1159–1178. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2004.01.008.

- Mannah, E., and Y. N. Gibril. 2012. “A Skills Gap Analysis for Private Sector Development in Sierra Leone 2012.” Economic and Sector Work Working Paper. African Development Bank. https://nctva.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Skills_Gap_Analysis_2012_AfDB.pdf

- Márquez, D. M. Z. 2020. “Decentering International Relations: The Continued Wisdom of Latin American Dependency.” International Studies Perspectives 21 (4): 403–423. doi:10.1093/isp/ekaa007.

- Martinussen, J. 1997. Society, State and Market: A Guide to Competing Theories of Development. London: Zed Books.

- Mason, R. 2017. “China’s Impact on the Landscape of African International Relations: Implications for Dependency Theory.” Third World Quarterly 38 (1): 84–96. doi:10.1080/01436597.2015.1135731.

- Matsumoto, M. 2018. “Technical and Vocational Education and Training and Marginalised Youths in Post-Conflict Sierra Leone: Trainees’ Experiences and Capacity to Aspire.” Research in Comparative and International Education 13 (4): 534–550. doi:10.1177/1745499918807024.

- McGrath, S. 2002. “Skills for Development: A New Approach to International Cooperation in Skills Development?” Journal of Vocational Education & Training 54 (3): 413–430. doi:10.1080/13636820200200207.

- McKenzie, D. 2017. “How Effective Are Active Labor Market Policies in Developing Countries? A Critical Review of Recent Evidence.” The World Bank Research Observer 32 (2): 127–154. doi:10.1093/wbro/lkx001.

- Meagher, K. 1995. “Crisis, Informalization and the Urban Informal Sector in Sub-Saharan Africa.” Development and Change 26 (2): 259–284. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7660.1995.tb00552.x.

- Merino, R. 2020. “The Cynical State: Forging Extractivism, Neoliberalism and Development in Governmental Spaces.” Third World Quarterly 41 (1): 58–76. doi:10.1080/01436597.2019.1668264.

- Monye, S., E. Ansah, and E. Orakwue. 2010. “Easy to Declare, Difficult to Implement: The Disconnect between the Aspirations of the Paris Declaration and Donor Practice in Nigeria.” Development Policy Review 28 (6): 749–770. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7679.2010.00508.x.

- Moyo, D. 2010. Dead Aid: Why Aid Is Not Working and How There Is Another Way for Africa. Reprint ed. London: Penguin.

- Musthaq, F. 2021. “Dependency in a Financialised Global Economy.” Review of African Political Economy 48 (167): 15–31. doi:10.1080/03056244.2020.1857234.

- Palmer, R. 2007. “Skills for Work?: from Skills Development to Decent Livelihoods in Ghana’s Rural Informal Economy.” International Journal of Educational Development 27 (4): 397–420. doi:10.1016/j.ijedudev.2006.10.003.

- Palmer, R. 2014. “Technical and Vocational Skills and Post-2015: Avoiding Another Vague Skills Goal?” International Journal of Educational Development 39: 32–39. doi:10.1016/j.ijedudev.2014.08.007.

- Peet, R. 2009. Unholy Trinity: The IMF, World Bank and WTO. 2nd Revised ed. London: Zed Books Ltd.

- Peet, R., and E. Hartwick. 2015. Theories of Development, Third Edition: Contentions, Arguments, Alternatives. 3rd ed. New York: Guilford Press.

- Roberts, G. O. 1975. “The Role of Foreign Aid in Independent Sierra Leone.” Journal of Black Studies 5 (4): 339–373. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2783665. doi:10.1177/002193477500500401.

- Roberts, D., and N. Khattri. 2012. Designing a Results Framework for Achieving Results: A How-to Guide. Washington, DC: World Bank. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/32158

- Rodney, W. 1972. How Europe Underdeveloped Africa. London: Bogle-L’Ouverture Publications.

- Rosas, N. R., M. C. Acevedo, and S. C. Zaldivar. 2017. “They Got Mad Skills: The Effects of Training on Youth Employability and Resilience to the Ebola Shock.” Policy Research Working Paper WPS8036. Washington, DC: World Bank. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/700321493126707105/They-got-mad-skills-the-effects-of-training-on-youth-employability-and-resilience-to-the-Ebola-shock

- Sesay, M. G., and M. Suma. 2009. “Transitional Justice and DDR: The Case of Sierra Leone.” International Center for Transitional Justice. https://www.ictj.org/sites/default/files/ICTJ-DDR-Sierra-Leone-CaseStudy-2009-English.pdf

- Singh-Peterson, L., and M. Iranacolaivalu. 2018. “Barriers to Market for Subsistence Farmers in Fiji – A Gendered Perspective.” Journal of Rural Studies 60: 11–20. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2018.03.001.

- Sjöstedt, M. 2013. “Aid Effectiveness and the Paris Declaration: A Mismatch between Ownership and Results-Based Management?” Public Administration and Development 33 (2): 143–155. doi:10.1002/pad.1645.

- Statistics Sierra Leone (SSL). 2019. “Sierra Leone Integrated Household Survey (SLIHS) Report 2018.” Freetown. https://www.statistics.sl/images/StatisticsSL/Documents/sierra_leone_labour_force_survey_report_2014.pdf

- Statistics Sierra Leone (SSL). 2014. “2013 Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) Survey for National Accounts Compilation.” https://www.statistics.sl/images/StatisticsSL/Documents/Publications/2013/2013_ngo_survey_for_national_accounts_compilation.pdf

- Sunkel, O. 1969. “National Development Policy and External Dependence in Latin America.” Journal of Development Studies 6 (1): 23–48. doi:10.1080/00220386908421311.

- Szántó, D. 2016. “The NGOization of Civil Society in Sierra Leone – A Thin Dividing Line between Empowerment and Disempowerment.” In Democratization and Human Security in Postwar Sierra Leone, edited by M. Mustapha and J. J. Bangura, 133–161. New York: Palgrave Macmillan US. doi:10.1057/9781137486745_7.

- United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). 2019. The Least Developed Countries Report 2019: The Present and Future of Development Finance – Old Dependence, New Challenges. New York: United Nations. https://unctad.org/en/PublicationsLibrary/ldcr2019_en.pdf

- World Bank. 2021. “World Development Indicators Online Database.” https://data.worldbank.org/data-catalog/world-development-indicators