Abstract

Civil society organisations (CSOs) often communicate global gendered inequalities simplistically from a fundraising framework to Global North audiences. While the stereotypical and racialising portrayals of women and girls in the Global South have been widely criticised, the diverse perceptions and experiences of development professionals regarding contested campaigning practices have been less discussed. Furthermore, literature has focussed on the Anglo-Saxon world, while the complex relations between gendered representations and neoliberal fundraising have been less studied in the Nordic context, where the marketisation of development apparatus is a fairly recent phenomenon. Drawing on a poststructuralist critique of development apparatus and postcolonial feminist reading on representations of the Global South, this article investigates how CSOs discursively frame gendered inequalities in their fundraising campaigns. By examining three fundraising campaigns in Finland, we demonstrate how CSOs are not only turning towards the use of a technical and neoliberal gender discourse, but doing so within an unforeseen advertising framework, in times of right-wing populist politics and a collapse in development funding. Basing our findings on qualitative data, we argue that CSOs are pressured to create simplified knowledge on gendered issues, which has provoked critical views not only from activists, but also from within CSOs.

Introduction

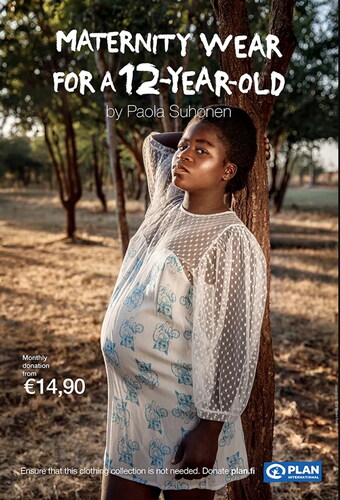

In 2017, one of Finland’s biggest development civil society organisations (CSOs), Plan Finland, provoked a heated public debate about the images it used for fundraising purposes. Its award-winning fundraising campaign Maternity Wear for a 12-Year-Old was built around fashion-like photos of a pregnant 12-year-old Zambian girl, modelling a mock maternity collection by a famous Finnish fashion designer. The photos, and the life-size mannequins presenting the maternity dresses, were displayed in the Helsinki city centre as if advertising the fashion collection, with the slogan ‘Ensure this clothing collection is not needed’. The combination of shock effect, racialised juxtapositions, and celebrity humanitarianism brought Plan Finland a record number of donations as it dramatically drew attention to child pregnancies. An intense debate arose on what should—and should not—be done in the name of doing good, as the campaign was fiercely criticised by many feminists, antiracism activists, and even fellow CSOs for neo-colonialism, racism, and violation of girls’ rights.

This highly contested campaign coincided with what many of the interviewees for this article called ‘the crisis in development cooperation’ in Finland. In parallel with the record levels of asylum and migration in Europe in 2015, a new Finnish government was formed that comprised a coalition of right-wing parties; this included an ethnonationalist populist party which had experienced a landslide increase in support in the parliamentary elections. With the pretext that citizens who supported development cooperation should donate to it privately, the government cut tax-based public aid funding by approximately 40%, leading to program cuts and employee layoffs within CSOs. Furthermore, Finnish corporations and the private sector in general became more prominent as development actors, as the government explicitly emphasised their role in investment and innovation, and portrayed other development efforts as old-fashioned and stale. This shook the development sector, as the state was an important funder of Finnish CSOs. The country was previously regarded, with the rest of the Nordic region, as pursuing an exemplarily generous ‘Nordic model’ of development aid (Elgström and Delputte Citation2016).

This article investigates how Finnish CSOs discursively frame gendered inequalities and solutions to them in their fundraising campaigns amidst an increasingly marketised development apparatus. We approach the changing fundraising markets through an examination of development professionals’ own diverse perceptions and experiences regarding the changing Finnish environment for fundraising campaigning. In so doing, we shed light on how development CSOs navigate changing circumstances such as those in Finland, where right-wing populist politics has been increasing in popularity and public funding has become more uncertain. To illustrate our claims, we introduce three fundraising campaigns that focus on gendered inequalities in the Global South and demonstrate, to varying degrees, responses to the increasing pressure towards private fundraising as government support has decreased. The campaigns investigated here are: (1) Walk a Woman a Profession, a campaign that promoted women’s economic independence; (2) the above-mentioned Maternity Wear for a 12-Year-Old by Paola Suhonen, which pushed for girls’ rights; and (3) Uncut, a campaign against female genital cutting (FGC). All three were executed in 2017, in the aftermath of the cuts in development funding, although the first was part of a larger framework of yearly campaigns (organised since 2010) and the third became, partly because of its fundraising success, a multi-annual campaign framework for the CSO.

Scholarly literature on gendered representations of global poverty has shown that development fundraising tends to simplify complex political issues into ahistorical and decontextualised personal narratives of surmounting suffering (Gellen and Lowe Citation2021; Wilson Citation2011; Vossen and Schulpen Citation2019), often enabled by an altruistic Northern individual in the form of a donor or a celebrity (Chouliaraki Citation2013; Repo and Yrjölä Citation2011; Kapoor Citation2013; Richey and Ponte Citation2008). While confirming that such trends exist in the Finnish CSO fundraising scheme, our article adds to the literature by focussing especially on development practitioners’ views and experiences of navigating increasingly competitive donor markets. Additionally, existing literature has tended to focus on the Anglosphere, while the complex relations between gendered representations and neoliberal fundraising have been less studied in the Nordic context, where the marketisation of the development apparatus is a fairly recent phenomenon. We argue that while representations of women and girls in development have always been problematic (and much examined), it is relevant to analyse their contemporary manifestations now that the complex intertwining of neoliberalism, right-wing populism, and racism is so acute in many development donor countries, including Finland.

Drawing on poststructuralist critique of development apparatus and postcolonial feminist reading on representations of the Global South, we demonstrate how CSOs are pressured to create simplified knowledge on gendered issues, which has provoked criticism not only from activists, but also within CSOs. We show that Finnish CSO campaigns tend to build on an institutionalised gender discourse that associates gendered inequalities with domestic work, traditional values, and reproductive functions, while promoting a right-wing policy framework that sees women’s economic empowerment as a technical tool for solving global problems, as has previously occurred in other countries (Davids, van Driel, and Parren Citation2014; Koffman and Gill Citation2013; Mukhopadhyay Citation2014; Wilson Citation2015). These simplistic discourses have not, however, emerged without surmounting a multiplicity of diverse views and internal battles among development professionals in Finnish CSOs. Some of our interviewees reflected critically on the discourses to which they adhere, while also expressing discomfort about working in increasingly competitive fundraising markets that they considered alien to how development cooperation should be organised in a Nordic welfare state.

Methodologically, we base this article on qualitative data from multi-sited observation, content analysis of CSO reports, semi-structured interviews with staff members from the three selected CSOs and professionals across the Finnish development sector, and interviews with individual donors who participated in campaign events. We also gathered data from the campaign webpages and 20 Facebook posts from each campaign during their peaks in 2017.Footnote1 We analysed these using multimodal critical discourse analysis, which critically investigates how linguistic and non-linguistic forms are used to communicate ideas, attitudes, and identities (Machin Citation2013), supplemented by tools from qualitative visual methodologies (Rose Citation2016). Thus we analysed the discourses of global gendered inequalities that the selected fundraising campaigns create.

We will start with a theoretical discussion on the power of the institutionalised gender discourse in development and how that power operates through CSO campaign discourses. It is followed by discussion of analytical insights into the contemporary political and policy scene in Finland, which contextualises CSO fundraising and the campaigns we examine.

Girls as agents of development and the power of CSO campaign discourses

One of the key driving forces of the post-WWII development apparatus has been its explicit rhetoric of doing good. This ‘will to improve’, as Li (Citation2007) puts it, informs the shaping and guiding of human conduct in the Global South through calculated means. Li argues that the development apparatus identifies specific problems—such as the unequal status of women and girls—that need to be corrected and then portrays as solutions the technical expertise and tools that the development apparatus itself entails and produces (Li Citation2007, 7). Consequently, many scholars have demonstrated that power operates in complex and diffuse ways in and through development policy, programming, and projects (Ferguson Citation1994; Li Citation2007; Ranta Citation2018; Rossi Citation2004). This approach to development goes beyond dependency scholarship and other structuralist and institutionalist approaches that correlate power with domination (Abrahamsen Citation2003, 198). Consequently, specific elites, state ministries, or finance sectors are not viewed as the sole loci of power. Rather, power as the moulding and regulating of groups and individuals can also be thought to operate in and through civil society, including development CSOs, their campaigns, and individual donors. Indeed, despite the often critical stance of CSOs, many scholars have demonstrated how they have increasingly become executors and reproducers of neoliberal governmental techniques, with effects both on CSOs’ own conduct and on expectations concerning the subjects of their interventions (Carroll Citation2009; Kurki Citation2011).

The institutionalised gender discourse has long been a powerful tool within the development apparatus, with changing emphases over the years. There has been a succession of ‘waves’ of gender discourse in development, including the agendas of Women in Development (WID), Gender and Development (GAD), and gender mainstreaming. The Fourth UN World Conference on Women in Beijing in 1995 proved to be a major landmark in putting gender equality on the development agenda, and CSOs that were booming during the 1990s were particularly active in pushing gender to the fore. (Kabeer Citation1994; Miller and Razavi Citation1995; Mukhopadhyay Citation2014). The gender agenda has been well incorporated in development discourse, and it has opened opportunities for women’s associations to gain political prominence in parts of the Global South (Tripp Citation2003).

Many scholars have, however, raised critical concerns about the practical implications of how gender equality is discussed within the development apparatus. For example, Mukhopadhyay (Citation2014) argues that while the institutionalisation of gender agenda was initially a radical force that brought feminist concerns from the margins to the mainstream, it has been reduced to a technical and heteronormative tool dissociated from structural inequalities (On the problems of gender mainstreaming, see also Parpart Citation2014). Others have discussed how the widely used development rhetoric of ‘empowering’ women in the Global South has further reduced women to ideal agents of neoliberal development (Cornwall and Rivas Citation2015; Davids, van Driel, and Parren Citation2014; Wilson Citation2015). Critics argue that such instrumentalisation of gender equality produces it as a technical tool to control reproductive and economic behaviour, while diluting its feminist edge (Jezierska and Towns Citation2018; Mukhopadhyay Citation2004, Citation2014; Repo Citation2016). In recent years, there has been a shift in emphasis from women to girls as objects of intervention, and girls are often seen as the unexpected solution to global poverty (Hickel Citation2014; Koffman and Gill Citation2013). If investing in women is smart economics, ‘investing in girls, catching them upstream, is even smarter economics’, as the World Bank’s managing director has put it (International Trade Centre Citation2009). According to Davids, van Driel, and Parren (Citation2014), such rhetoric constructs the essence of girls and women as possessing the qualities of a ‘good gender’: as potentially productive agents in neoliberal development, whose agency is restrained by domestic roles, traditional cultures, and fertility (Davids, van Driel, and Parren Citation2014; Wilson Citation2015).

As this particular version of the gender agenda as women’s and girls’ empowerment has gained prevalence in institutionalised aid discourses, development fundraising has increasingly focussed on a heroic individual woman and/or girl who overcomes suffering and becomes her true individual self through entrepreneurial spirit. In fact, ‘the emergence of the hyper-industrious entrepreneurial ‘girl’ from a low-income household in the Global South’, observes Wilson (Citation2015, 809), has become ‘a central trope of twenty-first century neoliberalism’, which is demonstrated in CSO communication. This marks a shift in the discursive frames of global inequalities used in CSO fundraising in the final decades of the twentieth century, when CSOs mainly represented global poverty with images of victimised and decontextualised children waiting for the (White) saviour from the Global North to come to the rescue (Dogra Citation2011; Kapoor Citation2013; Mitchell Citation2016; Wilson Citation2011). Postcolonial feminist critics claim that this discourse is often spiced with a gender difference that leans on the colonial idea of ‘saving brown women from brown men’, as Spivak (Citation1988) famously put it and as Abu-Lughod (Citation2002) and Mohanty (Citation1991) have flagged. Additionally, using this composition in gendered development discourse tends to categorise men in the Global South as sexually over-virile, oppressive (Fanon Citation2008 [1952]; Epprecht Citation2010), and ‘inherently “lazy”, irresponsible and preoccupied with sensual pleasure’ (Wilson Citation2011, 318).

While the shift from victimising ‘poverty porn’ images to a rhetoric of women and girls as worthy of investment has somewhat diversified gendered representations in the development discourse, they often still reduce the politics behind complex crises to a spectacle of helping in which the multidimensional forces at the root of inequalities are overlooked (Chouliaraki Citation2013; Gellen and Lowe Citation2021; Kapoor Citation2013; Repo and Yrjölä Citation2011; Sharp, Campbell, and Laurie Citation2010). Additionally, portraying women and girls as deserving objects of development intervention renders any critique of such interventions irrelevant, despite decolonial scholars’ decades-long criticism of the development apparatus and its intrinsic neocoloniality (Escobar Citation1995; Kothari Citation2006). Audiences in the Global North are provided with a clear-cut idea of development and its gendered instruments, as CSOs use their institutionalised power through campaign discourses. In Finland, CSOs produce such knowledge within a framework delimited by a changing political atmosphere, as will be discussed next.

Women and girls in Finnish development cooperation

Until the mid 1960s, Finland was a recipient of development aid. Several international organisations provided aid to war-torn Finnish Lapland, supporting the return of refugees and the post-war reconstruction. Finland’s largest development CSO, the Finn Church Aid, was established in 1947 to receive and implement foreign aid in Finland, while during the 1960s, it started to operate internationally at the same time as some other CSOs, such as the Finnish/Nordic Red Cross. Additionally, the involvement of Finnish CSOs in development cooperation took off through missionary work and left-wing international solidarity movements (Hakkarainen and Onali Citation2005). While the Finnish state continued receiving development loans from the World Bank during the early 1960s, it also initiated its own aid activities, with the aim of being identified with other Nordic countries and the West, but also as the result of pressure from solidarity movements and CSOs (Koponen and Saaritsa Citation2019). Tax-based public sector support for CSOs started in 1974 and, since the 1990s, the state has provided a major share of CSOs’ development aid funds, while private donations and corporate collaboration have played a subsidiary role in funding until recently (Onali Citation2005, 34). Currently, CSOs can apply for up to 85% of program and project costs from public funds, while volunteer work or similar contributions can cover 5% of the 15% self-financing share.

Gender equality has been among Finland’s development goals for decades, although its significance has varied between governments. In 2016, however, the strengthening of the status and rights of women and girls became the top priority area for the first time (Ulkoasiainministeriö Citation2016). This surprised many, because the Ministry for Foreign Affairs was led by Timo Soini, a conservative populist leader of the Finns Party, known, for example, for his anti-abortion agendas. This controversy was not specific to Finland but seemed to reflect the wider European political trend that intensified after 2015, in which gender equality rhetoric was instrumentalised to nationalist forces, supporting the vilification of racialised migrants (Colella Citation2021; Farris Citation2017). The overall program of the right-wing conservative and populist government was indifferent—even hostile—to gender concerns and proclaimed that Finland had already achieved gender equality (Elomäki et al. Citation2020, 68). The government’s development policy declared that ‘women’s and girls’ rights are an ordinary thing for Finns, but gender inequality is one of the biggest problems in developing countries’ (Ulkoasiainministeriö Citation2016, 16).

Such rhetoric uncritically continued the discursive juxtaposition between ‘Western feminism’ and ‘Third World Women’, against which Mohanty (Citation1991) had warned three decades earlier, and that also reflects the neocolonial and racialised categorisations used in development thinking more generally, as Kothari (Citation2006) suggests. The gender focus in development seemed particularly appealing in the Finnish context, where the myth of Nordic gender equality persists despite contradictory indications, such as the fact that Finland has one of the higher rates of gender-based violence in Europe European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE) (Citation2021). Gender equality, in addition to social justice and the education system, is linked with Finnish national identity to an exceptional degree (Keskinen et al. Citation2009; Rastas 2012; Stoltz Citation2020). This creates what Oinas (Citation2017, 180) refers to as the ‘Nordic paradox of a post-feminist idealization of achieved gender equality and neutrality’, which legitimises a self-proclaimed pioneer position in gender-related development aid.

Gender equality is high on the agendas of Finnish CSOs, including those whose campaigns are scrutinised here, and who all have women’s and girls’ rights as their top priority. In their official framings of their gender work, CSOs use many of the same wordings as the Ministry for Foreign Affairs. For example, when Plan Finland announced its new development program early in 2022, its focus on girls’ rights, particularly their sexual and reproductive health and rights, was an almost direct replication of the first priority area of the Finnish government’s development policy (Plan Finland Citation2022). Indeed, compliance with the Ministry and its effects on the CSOs’ self-regulation came to the fore in our interviews with Finnish development professionals (see also Onali Citation2005). An executive director of a middle-sized human rights CSO expressed their concern in the following way:

In Finland, sometimes, like in the 1960s, there was a movement and a conglomeration of organizations that were convinced that we need to look beyond our own borders, and to build global solidarity with developing countries. It grew from the realization of very big questions related to [global] gaps between the First and the Third World. How many of us talk about these issues today? Now we only talk of empowering these, let us say, Vietnamese women in this particular development project. Is it that we have actually started to limit the ways in which we understand [global] transformation? (Interview Feb 10, 2017)

Finland’s policy priorities—women, children and environment—have been good, and our organization also has them at the center of our work…But what drives the implementation seems to be the interests of Finnish businesses. It is like promoting Finnish exports above all. (Interview Feb 3, 2017)

The majority of the CSO representatives interviewed shared this concern about the growing importance of the private sector as a development actor. While rhetorically emphasising the plight of women and girls in the Global South, in practice the government enacted massive budget cuts of approximately 40% in 2016, particularly to UN institutions and CSOs that were known for their work on gender issues. The government reallocated 100 million euros of the remaining 800 million in aid funds as loans to private sector actors, a move that reflected the government’s wider strategic management interests (see Mykkänen Citation2016). CSOs were expected to form new alliances with Finnish corporations, and women and girls in the Global South were increasingly discussed in the framework of their potential to promote economic growth and private sector investments. We will next elaborate on the effects of these sudden changes in CSO funding framework.

Perceptions about changing CSO fundraising markets

The restructuring of development aid in 2016 was part of a 10-billion-euro public sector adjustment, efficiency, and competitiveness program, which in practice meant cuts to many of those progressive public sectors that were the basic pillars of the Nordic welfare system. As Elomäki et al. (Citation2020) have shown, the Finnish welfare state transformed into a ‘strategic state’ in which neoliberal economic objectives overruled any other political concerns. While the major reforms of the welfare state and its shift towards new public management had already been carried out during the 1980s and 1990s (Yliaska Citation2015), what particularly characterised the late 2010s neoliberal governmentality was an explicit shift towards nationalism and conservatism, visible in resistance to gender equality and immigration (Elomäki and Kantola Citation2018; Keskinen Citation2016).

The government’s new orientations on development aid were a major shock to the Finnish development sector. The three CSOs whose campaigns are scrutinised here were all deeply affected but, as became clear from interviews and their annual reports, they were quick to adapt to the increasing fundraising competition. A study conducted in 2016 revealed that CSOs had raised their investments in private fundraising after the cuts in the state development budget, and increasingly outsourced fundraising to advertising and communications agencies. Relatedly, CSO representatives reported increased perception of competition between CSOs that year (Taloustutkimus Citation2016). As the CEO of a mid-sized Finnish CSO described the dynamics of fundraising:

What has quite clearly happened [in Finland] is that the role of CSOs’ own fundraising has become emphasized. The powers of the market economy have taken over… Big CSOs with resources can conduct big campaigns and raise a great deal of money. It is impossible for medium and small organizations to compete [with them] in the fundraising market. In Finland, too, the atmosphere seems to be such that we are moving more and more toward a donation society, a charity society. (Interview Feb 18, 2017)

We are becoming a donation society, and more and more campaigns are being organised to appeal emotionally to people. Those images contribute to maintaining perceptions that everything is bad in developing countries and that there is no development at all. In general, people seem to think that things are much worse than they actually are. They do not know that poverty has reduced by half and that there are [fewer] people suffering from hunger than 20 years ago. Yet fundraising campaigns that portray everything as miserable reinforce inaccurate perceptions. Even if they attract money [to CSOs], I am not sure whether they are a good thing at all. (Interview Feb 18, 2017)

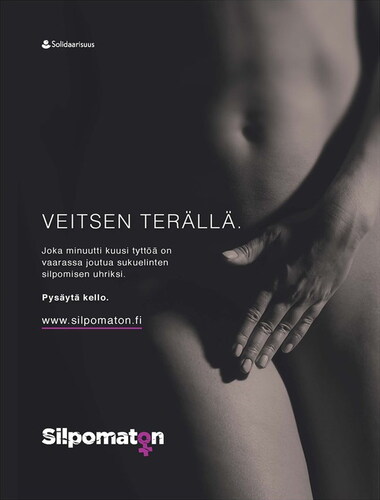

The second campaign is by Plan Finland, and it stresses girls’ rights to live out their youth as free and empowered individuals despite conservative, patriarchal environments that push them towards reproductive roles at an early age. Plan Finland is a national member of Plan International, best known for its child sponsorship program. It is among the largest CSOs in Finland (with a budget of19.5 million euro in 2020) and gains approximately half of its expenditure from sponsors and private donations, while over 30% is covered by public funds. Lastly, the third campaign sought to persuade aid donors to assist in saving girls from female genital cutting (FGC). It was executed by the International Solidarity Foundation (ISF), an aid organisation established in 1970 by the Finnish Social Democratic Party. During its early days, it channelled the party’s support for Third World decolonisation struggles, such as the Sandinista revolution in Nicaragua, and today it is known for its work against gender-based violence and FGC. While substantially smaller than the other two organisations, it is considered a large CSO in the Finnish context, with an annual budget of approximately 3 million euros.

Global South women as entrepreneurs

There is almost tangible positive energy in the damp September air as the group of a few dozen women, some holding colourful balloons, walk along the popular jogging track around the central bay in Helsinki. The chatty gathering is participating in the Walk a Woman a Profession event, organised annually by the Women’s Bank on the National Day of the Entrepreneur, which collects funds through a participation fee of 30 euros: the unit of measure for one profession for a woman in the organisation’s 15 program countries in the Global South. Walking ‘a better future for women in the Global South’, the campaign web page reassures, ‘support[s] women’s education, entrepreneurship, and independent livelihood in the Global South’ (Naisten Pankki Citation2017). This portrayal of women as the agents of change in development seemed to be absorbed by the red-cheeked women walking around the bay. One participant, a woman in her 60s, said she had seen in her travels in the Global South that ‘women work really hard, while men sit under a palm tree drinking beer and thinking their big thoughts’, and because of that, she argued, women were the ‘right target’ for development aid (Discussion Sept 5, 2017).

Women’s Bank is an exemplary follower of the Finnish government’s development policy agenda, presenting a clear focus on women’s entrepreneurship as the solution for global poverty. As a steering group member put it, ‘the reality is that in a developing country, the clearest and fastest way to earn money and to prosper is to start a business’ (Interview Oct 27, 2017). The organisation’s operative proximity to the business sector was also underlined in its use of corporate language: by ‘investing’ 750 euros one could become a Women’s Bank ‘shareholder’ and a ‘business angel’, while women in the Global South were referred to as ‘end customers’ in accordance to corporate, rather than development, jargon. All interviewees mentioned that they aim to avoid development jargon in their campaign communications and to detach the organisation from victimising development narratives. Many of the key figures in Women’s Bank were prominent business leaders from the worlds of banking, investment, law, and media, and adopted a somewhat sceptical attitude towards what the interviewees understood as ‘traditional’ development aid, which was perceived as inefficient. Another conscious detachment was made from work that was considered too radical: ‘[Women’s Bank] is not rage feminism’, as a board member put it, ‘but we have people involved who are capable and productive’ (Interview Oct 12, 2017).

The organisation’s logo was visibly present in the Women’s Bank Walk event (). The picture shows a silhouette of a presumably African woman, with symbols of different manual professions inside her head. There is a discursive relationship between the two main agents in the campaign frame: the imagined Global South female figure with its downward gaze, as if silenced, but possessed of inherent capacity for professional success, and the Finnish woman who grants her access to a profession. This juxtaposition is created when a gendered ‘Third World difference’, as discussed by Mohanty (Citation1991), is contrasted to the Finnish self-proclaimed exceptionalism in gender equality, while being underlined in the physical event where (White) Finnish women celebrated ‘doing good’ in an entrepreneurial spirit that reflected the country’s development policy discourse. As one interviewee put it, women in the Global South ‘possess great potential and power within, they just need that small support so that they can use that power and do the things they dream of’ (Interview Oct 27, 2017).

Figure 1. ‘Walk a woman a profession’.

Source: https://www.naistenpankki.fi/ (accessed September 2017). Credit: Finn Church Aid.

However, the interviews suggested that Women’s Bank leaned on a discourse of development as a non-hierarchical process disconnected from power relations:

In my choice of language, I try to be mindful about us being peers. That we [in Finland] have had better luck, and we try to even out this unfairness in the world, but we’re still on the same exact level. Of course our power builds on the fact that we can give money, but that’s it. (Interview 27 Oct 2017)

Figure 2. Plan Finland’s campaign advertisement.

Source: https://www.itsnicethat.com/news/hasan-and-partners-adceaward-advertising-120418 (accessed September 2018). Photograph by Meeri Koutaniemi. Credits: Plan Finland, Hasan & Partners.

Potential mothers

Plan Finland’s campaign, Maternity Wear for a 12-Year-Old by Paola Suhonen, was built around fashion-shoot-like photos of a pregnant, then-12-year-old Zambian girl, photographed by a celebrity Finnish photojournalist, Meeri Koutaniemi, while modelling a mock maternity collection by the prominent Finnish fashion designer Paola Suhonen. The suggested monthly donation to Plan Finland—14.90 euros—was displayed as if it were the price of a garment (). The campaign created a contrast between two worlds by portraying a young, pregnant African girl wearing clothes from the Finnish fashion industry, conceived in what the designer called ‘Hamptons style’: ‘that typical light blue, white, fresh, marine type of atmosphere, which is very far from the circumstances that girls live in [Zambia]’ (Plan Finland Citation2017).

According to campaign posters, 7 million children in developing countries become pregnant every year, including the campaign model. Although adolescent pregnancies have been diminishing globally for decades and the estimate refers to girls under the age of 18 (UNFPA Citation2015, 7), Plan Finland visually represented the phenomenon with a Black, pregnant, 12-year-old photographed against a savannah-like landscape. Although there was more information on child pregnancies and the model’s situation on the campaign website, the advertisements targeting the wider public elided such contextualisation. Representatives from Plan Finland who had been part of the campaign’s planning team revealed in an interview that the artistic choices were made in cooperation with an advertising agency. Using such a young girl as the face of the campaign was justified by its maximised emotional appeal to Finnish audiences (and thus, market potential) as, according to a communications planner, teenage pregnancies had generated compassion fatigue among donors (Interview Nov 11, 2017). Furthermore, the Maternity Wear campaign capitalised on the celebrity status of the Finnish designer and the Finnish photographer, whose humanitarian celebrity brands were greatly reinforced beside the campaign’s cause. Although perhaps not exceptional in international comparison, where celebrity humanitarianism has been common (Chouliaraki Citation2013; Kapoor Citation2013; Repo and Yrjölä Citation2011; Richey and Ponte Citation2008), the Maternity Wear campaign was notably more commercial and advertisement-like than usually seen in CSO campaign styles in the Finnish context.

While intending to communicate about child pregnancies, the campaign advertisement left the circumstances in which a 12-year-old girl became pregnant up to the audience’s interpretation. Without any access to an alternative discourse, it is not unlikely that many viewers took to familiar tropes of girls’ rights in the Global South, where discourses of African girls needing saving from sexually virile and violent African men flourish (Fanon Citation2008 [1952]; Epprecht Citation2010; Wilson Citation2011)—especially as studies suggest that the Finnish public’s preconceptions about girls’ rights in the Global South are excessively negative (Taloustutkimus Citation2015). In this gender discourse, girls in the Global South, whom the 12-year-old model represents, are portrayed as subjects whose productive potential is essentially restrained by traditional roles, framing gender inequality as being loose from power imbalances beyond the domestic (Davids, van Driel, and Parren Citation2014). Additionally, the campaign frames the highly victimised girl in sharp contrast with her imagined Finnish counterpart, of which the Finnish designer clothing is a reminder. In this imaginary, a Finnish post-feminist girlhood is carefree (Oinas Citation2017) and more closely associated with fashion and consumerism than motherhood.

By contrasting (African) misery with (Finnish) well-being, the campaign framed global poverty through a neocolonial juxtaposition that has been widely criticised over the past decades (Gellen and Lowe Citation2021; Vossen and Schulpen Citation2019; Wilson Citation2011; Kothari Citation2006). The discursive dichotomy is especially compelling in Finland, which has been shedding its national identity as a poor aid-receiver since the 1960s, while striving towards being associated with Western donors (Koponen and Saaritsa Citation2019). While admitting to reliance on an extreme discursive contrast, the interviewees nevertheless claimed that the campaign’s aims had been to ‘show [girls’] agency or potential and the power they have in them’ (Interview Nov 11, 2017). The same interviewee noted that the campaign’s aims were based on Plan International’s strategy to get 100 million girls to ‘learn, lead, decide, and thrive’, as part of the Because I’m a Girl movement, which the INGO had earlier rationalised with the statement that ‘girls mean business’ (Koffman and Gill Citation2013). However, this agenda was rather forced in the campaign discourse, which portrayed the pregnant girl less as an active entrepreneurial subject than a model example of what should not exist. Girls’ empowerment thinking was, however, present to the extent that the desired, imaginary girlhood was connected with the consumerist trope of neoliberal development through the fashion industry.

The campaign won national and international advertising awards (e.g. ADCE Citation2017) and became Plan Finland’s all-time most successful fundraising campaign (Plan International Suomi –konserni Citation2018). However, antiracism activists and feminists, including the Anti-Racist Research Network and the Finnish Society for Gender Studies, criticised the campaign’s gaze for being racist, voyeuristic, and consumerist. For example, it was criticised for portraying a young Black girl in an objectifying and sexualising way, which would not be considered dignified—or even legal, from a child protection perspective—if the child were blue-eyed and White (Mkwesha and Huber Citation2021). The public discussion brought development CSOs under unforeseen critical attention, as the Finnish mainstream media gave, to such an extent for the first time, space for the critical scrutiny of CSO campaigns as not just fundraising for a good cause, but as producers of knowledge about global inequalities. In 2018, Plan Finland apologised for their choices in the campaign, largely due to pleas for accountability by the antiracism organisation SahWira Africa International (Ruskeat Tytöt Citation2018).

Victims

Uncut was a fundraising campaign by the ISF, and focussed on work against FGC in a specific Kenyan community. The campaign was visible on the street level of Finland’s largest cities in 2016—2017, when ISF’s face-to-face fundraisers focussed on telling passers-by about FGC in Kenya. During the summer of 2017, one could not walk through Helsinki city centre without noticing the fundraisers and large banners with the Uncut campaign image (). It shows a simple, black-and-white photograph of a naked woman covering her genital area, drawing the viewer’s attention with intimacy and sex appeal. The slogan ‘On a knife edge’ quickly clarifies, however, that the woman’s body parts should be approached within a victimised rather than sexualised frame.

Figure 3. ‘On a knife edge. Every minute six girls are in danger of being mutilated. Stop the clock’.

Source: https://mobile.twitter.com/Solidaarisuus70/status/872039632090923008 (accessed September 2017). Credit: International Solidarity Foundation.

The campaign was the ISF’s first large fundraising campaign, and one of its main aims was to increase public awareness of the CSO, a respected actor in the Finnish development sector but not well known to the Finnish public (Interview Nov 26, 2017). This aim appeared in the ISF’s annual report of 2017, which mentioned that ‘brightening the ‘niche’ of ISF should be at the center of all operational reforms’ (Solidaarisuus Citation2018, 3). The organisation had been heavily affected by cuts in the state development budget, with a 26% decrease in outturn from 2015 to 2016, and, as the annual report stated, it was adapting to the new funding framework by ‘continuing with consistent investments to grow private fundraising’ (Solidaarisuus Citation2018, 3). The interviewees noted that FGC was chosen as a fundraising topic for its marketing appeal: ‘[FGC] appeals to Finnish people because it provokes emotions…and it provokes the need to do something’ (Interview Nov 26, 2017). Since then, the organisation has increasingly focussed its operations on FGC work, which has indeed become its increasingly visible niche in the Finnish development sphere.

FGC communication ethics were already fiercely debated in the Anglo-Saxon world in the 1990s, when Stephanie Welsh won the Pulitzer Prize for photos of FGC in Kenya, and the topic has been under academic critical scrutiny ever since (Njambi Citation2004; Johnsdotter and Mestre Citation2017). Although Finnish CSOs had worked against FGC for years without much public campaigning, it became the subject of heated public debate in 2014, after Finland’s largest newspaper published the same photographer, Meeri Koutaniemi’s photos of FGC in Kenya. These photos showed the faces and bodies of young girls who had been cut, leading to criticism from many activists and CSOs. Despite the controversy, Koutaniemi, whose celebrity status stems from her role as a do-gooder who travels around the Global South photographing human rights issues, became one of the best-known figures in anti-FGC work in Finland and was represented on the Uncut website as the ambassador of the campaign. After years of increasing public discussion on FGC in Finland, even ethnonationalist Finns Party politicians started lobbying alongside development CSOs for a legal initiative in 2019 to ban FGC.

ISF interviewees seemed more familiar with critical discussions on gendered representations of global poverty than those from the other two organisations. The information provided on the Uncut campaign website and social media challenged some preconceptions that Finnish audiences may have had about FGC: misconceptions about FGC’s connection with Islam were addressed by focussing on a Christian community, while Kenyan male activists’ stories received equal coverage with women’s stories in social media publications to highlight male agency. The interviewees noted that while FGC was an easy-to-sell fundraising subject, it was also a difficult topic ethically. The ISF communications manager perceived that while CSOs strive to communicate their work truthfully, pressure for fundraising forces them to consider whether donors find such messaging interesting. They added:

I think that CSOs are panicking a bit. It was awful, the cuts in the development budget were dramatic to everyone. Us, CSOs who receive program support, we have all been in distress. If 30–40% of operations is cut, you need to get those funds raised. (Interview Nov 26, 2017)

Conclusions

Finnish CSOs work within an increasingly neoliberalised environment for running development cooperation, which has pressured them to communicate gendered development issues in the Global South with a more marketised frame that tends to elide critical thought. This was visible in the campaigns scrutinised here, which reflected a shift towards commercialisation unforeseen in the Finnish context (as in the case of Plan’s campaign), while also causing slight unease among the campaign CSOs (as the ISF interviews suggested). However, our data reveal that more critical tones were articulated at higher levels of CSO management. Development professionals recognised a pressure towards thriving in the increasingly competitive fundraising scheme and were worried about how the markets of altruism more commonly seen in the Anglo-Saxon world will steer the public development discourse in Finland. In addition, they expressed concern about the increased emphasis on business strategies in Finnish development policy, and the simplistic and technical narratives in the women’s empowerment discourse—somewhat reflecting scholarly critique of the gender agenda in development.

For the most part, however, the interviewees behind the three campaigns had internalised the institutionalised gender discourse in development, in which ‘the “empowerment” of “developing world” women via the market is the “solution”’ (Wilson Citation2011, 323). The differences in perceptions may reflect the recent trend of increasing investments in fundraising, as employees in CSO marketing and communications units may have expertise in those areas, but not necessarily in critical perspectives on global development. Women’s Bank’s campaign organisers proudly dissociated themselves from the development apparatus and feminist thought, while highlighting an entrepreneurial, technical idea of development and women’s role in it—thus ironically complying with the Finnish development policy. Plan Finland, on the other hand, unapologetically mirrored the government’s development agenda and girls’ empowerment rhetoric that renders global power relations invisible, although the campaign’s frame relied on explicit neocolonial juxtapositions and fell short of even its unradical aim. The ISF was the only organisation to demonstrate some critical self-reflection about communicating gender-based violence, but much of that awareness, too, was lost in its campaign.

While Finnish CSOs had previously enjoyed a relatively secure model of steady public funding, the crisis suffered by the development sphere in 2016 left them permanently alert to the possibility of such crises recurring whenever governments change. Confirming earlier findings in studies about representations of gendered inequalities in development fundraising, we suggest that CSOs are likely to utilise a conservative discourse as a pragmatic strategy to engage with presumably conservative audiences in the increasingly competitive fundraising markets. However, it is important to note that there are nuances to how campaigns target different audience demographics, and how those groups respond to such discourse. We have demonstrated that Finnish CSOs have reduced complex feminist struggles to neocolonial and neoliberal advertisements with which even the ethnonationalist Finns Party voter can sympathise as a potential donor.

However, the oversimplified narratives that frame well-intentioned fundraising campaigns should not be overlooked only because CSOs face external pressure, as they then compromise the important purpose of educating the public about complex global development issues. The Finnish development apparatus needs a more thorough, critical discussion of its own role in the creation and maintenance of gendered neocolonial discourses in the face of rising ethnonationalist and misogynist politics, as such images may also negatively impact anti-racist and feminist work more generally. Development CSOs have until recently enjoyed a position shielded from criticism as the altruists in Finnish civil society, but as Plan Finland’s campaign demonstrates, this is changing as antiracism and decolonial activist voices gain a foothold in public discourse. Further, as this article has discussed, the marketisation of altruism has raised critical concerns among development professionals too, which suggests the need for more thorough critical self-reflection in the Finnish and Nordic development policy spheres.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the peer reviewers and Elina Oinas for invaluable comments and feedback on versions of this work.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Martta Kaskinen

Martta Kaskinen is a PhD researcher in global development studies at the University of Helsinki. Her research focuses on feminist activism and its relations with institutionalised gender work in Kenya. Her research interests include feminism, gender and development, and representations of global poverty.

Eija Ranta

Eija Ranta is an Academy of Finland research fellow (2021–2026) and University Lecturer in Global Development Studies at the University of Helsinki. Her research interests include activism, state formation and democracy in the Global South, as well as development alternatives, such as Buen Vivir/Vivir Bien.

Notes

1 In terms of the division of labor between the authors, Kaskinen conducted multi-sited observation, analysis of CSO reports, analysis of social media posts, and 10 semi-structured interviews with CSO professionals related to the three campaigns. Ranta conducted 22 semi-structured interviews with professionals from across the Finnish development CSO sphere. The latter interviews were originally conducted for the purpose of research on the state of civil society in Finland, commissioned by the Ministry for Foreign Affairs of Finland (Kontinen et al. Citation2017). The contract allows the use of the same data in academic articles. Furthermore, each participant gave their informed consent for the use of the interviews as data for academic articles.

Bibliography

- Abrahamsen, R. 2003. “African Studies and the Postcolonial Challenge.” African Affairs 102 (407):189–210. doi:10.1093/afraf/adg001.

- Abu-Lughod, L. 2002. “Do Muslim Women Really Need Saving? Anthropological Reflections on Cultural Relativism and Its Others.” American Anthropologist 104 (3):783–790. doi:10.1525/aa.2002.104.3.783.

- ADCE. 2017. “Teen Maternity Clothing Campaign Recognized with ADCE’s Creative Distinction Award.” https://www.adceurope.org/news/creative-distinction-2018/. last visited: Jul 2018. Web page since removed.

- Carroll, T. 2009. “Social Development’ as Neoliberal Trojan Horse: The World Bank and the Kecamatan Development Program in Indonesia.” Development and Change 40 (3):447–466. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7660.2009.01561.x.

- Chouliaraki, L. 2013. The Ironic Spectator: Solidarity in the Age of Post-Humanitarianism. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Colella, D. 2021. “Femonationalism and anti-Gender Backlash: The Instrumental Use of Gender Equality in the Nationalist Discourse of the Fratelli D’Italia Party.” Gender & Development 29 (2–3):269–289. doi:10.1080/13552074.2021.1978749.

- Cornwall, A., and A.-M. Rivas. 2015. “From ‘Gender Equality’ and ‘Women’s Empowerment’ to Global Justice: Reclaiming a Transformative Agenda for Gender and Development.” Third World Quarterly 36 (2):396–415. doi:10.1080/01436597.2015.1013341.

- Davids, T., F. van Driel, and F. Parren. 2014. “Feminist Change Revisited: Gender Mainstreaming as Slow Revolution.” Journal of International Development 26 (3):396–408. doi:10.1002/jid.2945.

- Dogra, N. 2011. “The Mixed Metaphor of ‘Third World Woman’: Gendered Representations by International Development NGOs.” Third World Quarterly 32 (2):333–348. doi:10.1080/01436597.2011.560472.

- Elgström, O., and S. Delputte. 2016. “An End to Nordic Exceptionalism? Europeanisation and Nordic Development Policies.” European Politics and Society 17 (1):28–41. doi:10.1080/23745118.2015.1075765.

- Elomäki, A., and J. Kantola. 2018. “Theorising Feminist Struggles in the Triangle of Neoliberalism, Conservatism and Nationalism.” Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State & Society 25 (3):337–360. doi:10.1093/sp/jxy013.

- Elomäki, A., J. Kantola, A. Koivunen, and H. Ylöstalo. 2020. “Changing Feminist Politics in a ‘Strategic State.” In Feminisms in the Nordic Region: Neoliberalism, Nationalism, and Decolonial Critique, edited by Suvi Keskinen, Pauline Stoltz, and Diana Mulinari, 67–88. Cham: Palgrave MacMillan.

- Epprecht, M. 2010. “The Making of ‘African Sexuality’: Early Sources, Current Debates.” History Compass 8 (8):768–779. doi:10.1111/j.1478-0542.2010.00715.x.

- Escobar, A. 1995. Encountering Development: The Making and Unmaking of the Third World. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE). 2021. Combating Violence against Women: Finland. Vilnius: The European Institute for Gender Equality.

- Fanon, F. [1952] 2008. Black Skin, White Masks. London: Pluto Press.

- Farris, S. R. 2017. In the Name of Women’s Rights: The Rise of Femonationalism. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Ferguson, J. 1994. The anti-Politics Machine: Development, Depoliticization, and Bureaucratic Power in Lesotho. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Gellen, S., and R. D. Lowe. 2021. “(Re)Constructing Social Hierarchies: A Critical Discourse Analysis of an International Charity’s Visual Appeals.” Critical Discourse Studies 18 (2):280–300. doi:10.1080/17405904.2019.1708762.

- Hakkarainen, O., and A. Onali. 2005. Suomi ja köyhdytetyt: Kehitysmaaliike vuosituhannen vaihteessa. Helsinki: Like.

- Hickel, J. 2014. “The ‘Girl Effect’: Liberalism, Empowerment and the Contradictions of Development.” Third World Quarterly 35 (8):1355–1373. doi:10.1080/01436597.2014.946250.

- International Trade Centre. 2009. “The Girl Effect.” International Trade Forum, Issue 1 https://www.tradeforum.org/Girl-effect/.

- Jauhola, M., and M. Lyytikäinen. 2020. “Kutistettu feminismi? Suomen ulkosuhteiden tasa-arvopolitiikka kylmän sodan YK-feminismistä 2010-luvun tolkkutasa-arvoon.” In Tasa-Arvopolitiikan Suunnanmuutoksia: talouskriisistä Tasa-Arvon Kriiseihin, edited by J. Kantola, P. Koskinen Sandberg, and H. Ylöstalo, 150–168. Helsinki: Gaudeamus.

- Jezierska, K., and A. Towns. 2018. “Taming Feminism? The Place of Gender Equality in the ‘Progressive Sweden’ Brand.” Place Branding and Public Diplomacy 14 (1):55–63. doi:10.1057/s41254-017-0091-5.

- Johnsdotter, S., and R. Mestre. 2017. “Female Genital Mutilation’ in Europe: Public Discourse versus Empirical Evidence.” International Journal of Law, Crime and Justice 51. doi:10.1016/j.ijlcj.2017.04.005.

- Kabeer, N. 1994. Reversed Realities: Gender Hierarchies in Development Thought. London: Verso.

- Kapoor, I. 2013. Celebrity Humanitarianism: The Ideology of Global Charity. New York: Routledge.

- Keskinen, S. 2016. “From Welfare Nationalism to Welfare Chauvinism: Economic Rhetoric, the Welfare State, and Changing Asylum Policies in Finland.” Critical Social Policy 36 (3):352–370. doi:10.1177/0261018315624170.

- Keskinen, S., S. Tuori, S. Irni, and D. Mulinari. 2009. Complying with Colonialism: Gender, Race and Ethnicity in the Nordic Region. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Koffman, O., and R. Gill. 2013. “The Revolution Will Be Led by a 12-Year-Old Girl’: Girl Power and Global Biopolitics.” Feminist Review 105 (1):83–102. doi:10.1057/fr.2013.16.

- Kontinen, T., E. Ranta, C. Lohenoja, and A. Nguyahambi. 2017. Kansalaisyhteiskuntaselvitys: Kansalaisyhteiskunnan toimijoiden rooli kehitysyhteistyössä. Jyväskylä: University of Jyväskylä.

- Koponen, Juhani and Sakari Saaritsa, eds. 2019. Nälkämaasta hyvinvointivaltioksi: Suomi kehityksen kiinniottajana. Helsinki: Gaudeamus.

- Kothari, U. 2006. “An Agenda for Thinking about ‘Race’ in Development.” Progress in Development Studies 6 (1):9–23. doi:10.1191/1464993406ps124oa.

- Kurki, M. 2011. “Governmentality and EU Democracy Promotion: The European Instrument for Democracy and Human Rights and the Construction of Democratic Civil Societies.” International Political Sociology 5 (4):349–366. doi:10.1111/j.1749-5687.2011.00139.x.

- Li, T. M. 2007. The Will to Improve: Governmentality, Development, and the Practice of Politics. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Machin, D. 2013. “What is Multimodal Critical Discourse Studies?” Critical Discourse Studies 10 (4):347–355. doi:10.1080/17405904.2013.813770.

- Miller, C., and S. Razavi. 1995. “From WID to GAD: Conceptual Shifts in the Women and Development Discourse.” UNRISD Occasional Paper, No. 1. Geneva: United Nations Research Institute for Social Development (UNRISD).

- Mitchell, K. 2016. “Celebrity Humanitarianism, Transnational Emotion and the Rise of Neoliberal Citizenship.” Global Networks 16 (3):288–306. doi:10.1111/glob.12114.

- Mkwesha, F., and S. Huber. 2021. “Rethinking Design: A Dialogue on anti-Racism and Art Activism from a Decolonial Perspective.” In Feminisms in the Nordic Region: Neoliberalism, Nationalism and Decolonial Critique, edited by Suvi Keskinen, Pauline Stoltz, and Diana Mulinari, 223–245. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Mohanty, C. T. 1991. “Under Western Eyes: Feminist Scholarship and Colonial Discourses.” In Third World Women and the Politics of Feminism, edited by Chandra Mohanty, Ann Russo and Loudres Torres, 51–80. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Mukhopadhyay, M. 2004. “Mainstreaming Gender or “Streaming” Gender Away: Feminists Marooned in the Development Business.” IDS Bulletin 35 (4):95–103. doi:10.1111/j.1759-5436.2004.tb00161.x.

- Mukhopadhyay, M. 2014. “Mainstreaming Gender or Reconstituting the Mainstream? Gender Knowledge in Development.” Journal of International Development 26 (3):356–367. doi:10.1002/jid.2946.

- Mykkänen, J. 2016. Strategic Government Program: Overview of the Procedure and Its Execution. Helsinki: Talouspolitiikan arviointineuvosto.

- Njambi, W. N. 2004. “Dualisms and Female Bodies in Representations of African Female Circumcision.” Feminist Theory 5 (3):281–303. doi:10.1177/1464700104040811.

- Naisten Pankki. 2017. “Ammatteja käveltiin naisille yli 88 000 eurolla 70 paikkakunnalla Suomessa ja maailmalla.” September. Accessed 6 February 2022. https://www.naistenpankki.fi/tiedotteet/ammatteja-kaveltiin-naisille-85-000-eurolla-70-paikkakunnalla-suomessa-maailmalla/

- Oinas, E. 2017. “The Girl and the Feminist State? Subjectification Projects in the Nordic Welfare State.” In Nordic Girlhoods: New Perspectives and Outlooks, edited by Bodil Formark, Heta Mulari, and Myry Voipio, 179–206. Cham: Springer.

- Onali, A. 2005. “Kansalaisjärjestöjen kehitysyhteistyön rahoitus – renki vai isäntä?” In Suomi ja köyhdytetyt: Kehitysmaaliike vuosituhannen vaihteessa, edited by Outi Hakkarainen and Anja Onali, 20–37. Helsinki: Like.

- Parpart, J. L. 2014. “Exploring the Transformative Potential of Gender Mainstreaming in International Development Institutions.” Journal of International Development 26 (3):382–395. doi:10.1002/jid.2948.

- Plan Finland. 2017. “12-vuotiaan äitiysvaatteet.” Accessed December 2017. https://plan.fi/sv/node/19999 web page since removed.

- Plan Finland. 2022. “Työmme tasa-arvon ja tyttöjen oikeuksien puolesta vahvistuu.” January. Accessed February 2022. https://plan.fi/artikkelit/tyomme-tasa-arvon-ja-tyttojen-oikeuksien-puolesta-vahvistuu/

- Plan International Suomi –konserni. 2018. “Tilinpäätös 2018.” June 30 https://plan.fi/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Tilinpaatos-fy18.pdf.

- Ranta, E. 2018. Vivir Bien as an Alternative to Neoliberal Globalization: Can Indigenous Terminologies Decolonize the State? Abingdon: Routledge.

- Repo, J. 2016. “Gender Equality as Biopolitical Governmentality in a Neoliberal European Union1.” Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State & Society 23 (2):307–328. doi:10.1093/sp/jxu028.

- Repo, J., and R. Yrjölä. 2011. “The Gender Politics of Celebrity Humanitarianism in Africa.” International Feminist Journal of Politics 13 (1):44–62. doi:10.1080/14616742.2011.534661.

- Richey, L. A., and S. Ponte. 2008. “Better (Red)tm than Dead? Celebrities, Consumption and International Aid.” Third World Quarterly 29 (4):711–729. doi:10.1080/01436590802052649.

- Rose, G. 2016. Visual Methodologies: An Introduction to Researching with Visual Materials. London: SAGE.

- Rossi, B. 2004. “Revisiting Foucauldian Approaches: Power Dynamics in Development Projects.” Journal of Development Studies 40 (6):1–29. doi:10.1080/0022038042000233786.

- Ruskeat Tytöt . 2018. “Sahwira Africa International Reaches Compromise with Plan International Finland and Ad Agency.” August 29, Visited June 21, 2022. https://www.ruskeattytot.fi/sahwira-africa-plan-international

- Sharp, J., P. Campbell, and E. Laurie. 2010. “The Violence of Aid? Giving, Power and Active Subjects in One World Conservatism.” Third World Quarterly 31 (7):1125–1143. doi:10.1080/01436597.2010.518789.

- Solidaarisuus. 2016. Silpomaton. https://silpomaton.fi/. last visited July 2018, page changed since.

- Solidaarisuus. 2018. Tilinpäätös ja toimintakertomus. May. Accessed February 2022. https://solidaarisuus.fi/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Solidaarisuus-tilinp%C3%A4%C3%A4t%C3%B6s-2017.pdf.

- Spivak, G. C. 1988. “Can the Subaltern Speak?” In Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture, edited by Cary Nelson and Lawrence Grossberg, 271–313. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

- Stoltz, P. 2020. “Co-Optation and Feminisms in the Nordic Region: ‘Gender-Friendly’ Welfare States, ‘Nordic Exceptionalism’ and Intersectionality.” In Feminisms in the Nordic Region: Neoliberalism, Nationalism, and Decolonial Critique, edited by Suvi Keskinen, Pauline Stoltz, and Diana Mulinari, 23–43. Cham: Palgrave MacMillan.

- Taloustutkimus. 2015. Kansalaisten tietämys kehitysyhteistyöasioista. Ministry for Foreign Affairs of Finland.

- Taloustutkimus. 2016. Kansalaisjärjestöjen taloudellisten toimintaedellytysten nykytila 2016. Tutkimusraportti. VaLa, KANE, Kepa, SOSTE & Valo.

- Tripp, A. M. 2003. “Women in Movement Transformations in African Political Landscapes.” International Feminist Journal of Politics 5 (2):233–255, July. doi:10.1080/1461674032000080585.

- Tufte, T. 2017. Communication and Social Change: A Citizen Perspective. Cambridge: Polity Books.

- Ulkoasiainministeriö. 2016. “Suomen Kehityspolitiikka: Yksi Maailma, Yhteinen Tulevaisuus – Kohti Kestävää Kehitystä.” Valtioneuvoston selonteko 4.2.2016, VNS 1/2016 vp.

- UNFPA. 2015. Girlhood, Not Motherhood: Preventing Adolescent Pregnancy. New York: United Nations Population Fund.

- Vossen, M., and L. Schulpen. 2019. “Media Frames and Public Perceptions of Global Poverty in the UK: Is There a Link?” Communications 44 (1):59–79. doi:10.1515/commun-2018-2006.

- Wilson, K. 2011. “Race’, Gender and Neoliberalism: Changing Visual Representations in Development.” Third World Quarterly 32 (2):315–331. doi:10.1080/01436597.2011.560471.

- Wilson, K. 2015. “Towards a Radical Re-Appropriation: Gender, Development, and Neoliberal Feminism.” Development and Change 46 (4):803–832. doi:10.1111/dech.12176.

- Yliaska, V. 2015. “New Public Management as a Response to the Crisis of the 1970s: The Case of Finland, 1970–1990.” Contemporary European History 24 (3):435–459. doi:10.1017/S0960777315000247.