Abstract

Whilst the state of precarity negatively impacts Syrian refugees in Turkey, an increasing number of scholars suggest that Syrians are integrating well in that country due to cultural similarities and relatively ‘liberal’ refugee policies. This paper asks why this discrepancy occurs between studies that depict a positive picture of integration and the reality on the ground that approximately 40% of Syrians in Turkey want to go to a country other than Syria and Turkey. The article explains this contradiction by introducing a new-grounded theory of ‘reluctant local integration’. Based on a sequential research design that is composed of a thematic analysis of original fieldwork with 106 participants in the city of Gaziantep and a follow-up theory-guided process tracing in wider Turkey between 2015 and 2021, the article identifies original links between three intertwined themes that lead to reluctant local integration. These are not only a by-product of temporary protection, and unevenly distributed precarity in the economic milieu, but also a result of similar types of ideological, ethnic and religious sectarianism that is deeply rooted in both refugee and host communities in Turkey.

Introduction

Since the outbreak of Syrian civil war in 2011, more than half the population in Syria have fled to Lebanon, Jordan and Turkey. The role of Turkey is very significant because the 3,7 million registered Syrians in Turkey (UNHCR 2022) have made it the biggest host of refugees in the world since 2014 and that the country has become the main transit route to Europe for those refuges who ultimately want to flee to Europe. Therefore, the role of neighbouring countries in the Syrian refugee crisis has become more important than ever. According to the World Food Programme (2021) only 1% of Syrians in Turkey reside in camps. The rest do their best to make ends meet in communities across the country, but particularly in the provinces of the southeast region, such as Gaziantep, Kilis and Hatay.

The impact of refugees on underdeveloped neighbouring countries has not received much attention before the Syrian War broke in 2011. Since then, the impact of refugee crises on third-world countries such as Turkey has been an emerging area of study. For example, Mahia et al. (Citation2020:23) find a positive economic impact of Syrian refugees of around 2% of GDP in the short term and 4% in the long term in Turkey. They argue, ‘Syrian immigration in Turkey is becoming a factor of economic dynamism that not only benefits the Syrian community itself but also the Turkish host communities.’ Erdogan (Citation2019) explains that the World Bank and many other international organisations welcome Turkey’s liberal refugee policies on the basis that the country allows refugees to live outside camps, work and contribute to the economy. One recent study by Blair, Grossman, and Weinstein (Citation2020) also argues that integration becomes more likely in such contexts as liberal refugee policies there including access to services, employment rights and free movement attract more refugees and transnational ethnic and religious linkages in such places also ease mutual acceptance by both refugees and host communities. This is also backed up by Rottmann and Kaya (Citation2021) who studied the aspirations of Syrian refugees to stay in Istanbul with a conclusion that most Syrians choose to integrate in Turkey because they believe they would not be able to do so in Europe. Similarly, Kılıçaslan (Citation2016) looks at the interactions of Kurdish refugees from Syria with internally displaced Kurds in Istanbul and find that this cultural affinity between the two groups has a transformative power.

This approach, however, is not able to explain what makes Syrian refugees in Turkey to flee to Europe risking their lives in the process, which is all well evidenced, by Crawley and Jones (Citation2021). The Syrians Baromoter by Erdogan (Citation2020:184) also shows that the percentage of Syrians who would like to go to another country other than Syria and Turkey has risen from 31,5% in 2017 to approximately 40% in 2019.

Research question and objective

Our research addresses this puzzle and answers why some Syrians still want to leave Turkey (Erdoğan Citation2020) although it is argued by an increasing number of scholars that Syrians integrate well into the Turkish society thanks to cultural similarities and so called ‘liberal refugee policies’ in the country.

Literature review and original contribution

We introduce three new arguments/themes to the theoretical and empirical literature that can develop an over-arching answer to this question.

Firstly, the theories of acculturation (Berry Citation1997) and similarity-attraction (Van Oudenhoven et al. Citation2006) explore the role of contact, cultural similarity (Brown Citation1984, Poslon and Lasticova Citation2019) and relationships with a like-ethnic group in facilitating the integration of refugees (Ager and Strang Citation2008). Recently, in the context of Turkey, Kilicaslan (2016), Kaya (Citation2017), Rottmann and Kaya (Citation2021) argued that a cultural affinity between Turks, Syrians and Kurds eases contact and integration in Istanbul. Jacoby et al. (2019) argued that Islam has played an important role in the integration of Syrian refugees in the city of Bursa, a stronghold of religious Sunni conservatism. Morgűl and Savaşkan (Citation2021: 1) also argue ‘religious motives have a bias-reducing effect on conservative Sunni Muslims’ attitudes towards Syrian refugees in Istanbul’. Şafak-Ayvazoğlu et al. (Citation2021:1) argue that ‘religion is a key element of cultural similarity for the majority of Syrian refugees, which was reported to contribute to their life satisfaction, positively affecting psychological adaptation’. However, neither Turks nor Syrians are a homogenous group. Although they share the same religion, both communities are divided along the similar lines of ethnic, ideological and sectarian polarisations. It may be true that Kurdish Syrians find it easier to socialise with Kurds in Turkey (Rottmann and Kaya Citation2021), and as can be seen in the example of Bursa where there is a strong religious Sunni Turkish community, Sunni Muslim Syrians may feel at ease (Jacoby et al. 2019). However, these accounts only show pockets of integration between Turkish and Syrian subgroups in silos. Syrians in Turkey, in the bigger picture, become a part of the country’s pre-existing culture of societal conflict, tension, and deep polarizations between ideological (secular vs. conservative), ethnic (Kurdish vs. Turkish), and sectarian (Alawite vs. Sunni) subgroups. This makes it especially difficult for Syrians when they need to interact with the members of potentially adversary groups in the host society. This is observable when the Syrian Kurds cannot trust Turkish officials and police forces; when secular Turks doubt religious Syrians; and when secular or Alawite Syrians likewise cannot trust conservative Sunnis in Turkey. The impact of these wide range of ideological, ethnic and religious divisions and polarisations on Syrian’s trust in the system and their integration prospects have not been fully studied. Our interviews from Gaziantep in Turkey provide original empirical evidence on how sub-groups of Syrians such as Kurds, Alawites, Sunnis, secular and conservatives deeply mistrust one another as these divisions created a conflict that pushed them away from Syria in the first place. This also translates into mistrust in officials and the broader society in Turkey that is also politically divided along the very same lines and makes Syrians fear that their information will reach to Syria if they share it with adversary groups in the host community. Differently from other studies such as that of Oner et al. (Citation2015) focussing on how economic vulnerability and precarity leads to exodus mobility from Turkey, we highlight the uncontrolled domestic mobility of urban Syrian refugees within Turkey due to cultural and ideological sectarianism and how this uncontrolled domestic mobility in return worsens the vulnerability of Syrians who thereby increasingly want to leave Turkey yet have no option other than staying put in the country.

Second, contrary to the argument that liberal policies including employment rights and free movement make it attractive for refugees to seek settlement in developing neighbour countries like Turkey, Kavak (Citation2016), Baban, Ilcan, and Rygiel (Citation2017) and Osseiran (Citation2020) show that when such ‘liberal policies’ are not legally binding they lead to the violation of labour rights, creates further inequalities in relation to refugees’ integration in practice. Ertorer (Citation2021) stresses that the precarious legal status of Syrian refugees in Turkey threatens their existence in the social and economic milieus and lead to exodus mobility. However, these studies, with their exclusive focus on precarity, cannot concurrently account for the other side of the coin that demonstrates a relatively positive experience of integration for some Syrians either. Our study fulfils this research gap and shows that precarity and its negative effects as experienced by Syrians are not evenly distributed. The emphasis here is on the ‘uneven precarity’ that while some Syrians are keen and able to integrate well in Turkey, others, who do not have the cultural or financial capital, experience protraction of their poverty in the process. Although the members of latter group remain in Turkey for the time being and participate in the labour market of that country, this does not mean that they integrate well. When conditions become unbearable, they in fact want to leave Turkey, but find out that they cannot do so through legal routes.

Third, cultural and economic determinants of desire to flee from Turkey are also compounded by the impact of legal precarity/temporary protection on community relationships. Differently from the studies mentioned above on direct ways in which precarity impacts Syrians, we account for how the temporary protection status of Syrians is perceived by various segments of the Turkish society and how their perception of the policies that define Syrians as ‘guests’ then indirectly shapes attitudes towards Syrians and their integration prospects. Yitmen et al. (Citation2022) argue that ‘when Syrian refugees are perceived as temporary residents, short term concerns – such as being hospitable and wanting to help Muslim brothers – may be more important than long term competitive considerations’. Our findings present a contrasting picture in which ‘guest status’ was perceived by locals as a reason to believe that Syrians do not have a legal ground to be there or entitled to the financial aids and welfare services they receive in Turkey. The uneven precarity, as explained above, and a perception that some Syrians in Turkey are wealthy also take away the sympathy for the less fortunate Syrian ‘guests’ in Turkey as they are mistaken for the members of the former group. This perception is especially relevant amongst locals who are financially vulnerable in the first place. The worsening economic crisis in the country and growing concerns over unemployment amongst locals in recent years galvanise the negative approaches to ‘guesthood’ that leaves room for questioning the legitimacy of Syrians to be in Turkey. Ten years after the onset of the refugee crisis, Syrians are still ‘guests’ in Turkey and made to feel they outstayed their welcome in Turkey (Karasapan Citation2019). As such ‘guesthood’ in Turkey can no longer be seen as a narrative that increases acceptance and hospitality towards Syrians as argued by Yitmen et al. (Citation2022). Syrians want to leave as a result of the hostile environment that their protracted guest status has created; but it is the very same system of ‘guesthood’/temporary protection that prevents them from legally seeking resettlement in third countries of their choice.

A new-grounded theory of ‘reluctant local integration’

The original contribution of this paper lies not only in the explanation of the three individual dynamics from new perspectives mentioned above but also in its overall implication that the combination of these three dynamics leads to what we will hereafter call ‘reluctant local integration’Footnote1. By introducing this new concept, we shed light on the reason why a big group of Syrians still want to seek asylum in Europe whilst an increasing volume of studies paradoxically find that Syrians are integrating well in Turkey.

We provide a balanced picture of diverse experiences and, for the first time, introduce the concept of ‘reluctant local integration’ for those refugees who find themselves marginalised most by the system and deteriorating community relationships, but have no options to exit. Local integration is defined as a combination of factors including a) legal rights to work, b) access to housing and welfare services, and c) mutual acceptance. (Crisp Citation2004). The concept of ‘reluctant local integration’ we introduce suggests that a certain number of refugees who can stay and legally work in Turkey or learn the Turkish Language cannot or should not be considered as a reliable indicator of successful integration or refugee crisis management in Turkey. In relation to other two possibilities of response as ‘return’ and ‘resettlement’ local integration implies that refugees prefer to remain in their country of refuge for the mid-to-long term to rebuild their lives. However, this could also be the result of the fact that when their chances of returning their country of origin is not possible due to the continuation of reasons for their flee and not being able to resettle into a third country of their choice. In other words, the so-called local integration becomes the only realistic option for those refugee populations even though this is not their preferred action. Therefore, it is important to recognise this phenomenon as ‘reluctant local integration’ to underline the fact that what is experienced by Syrians in Turkey as local integration is not their choice but enforced on them as they have no other choice.

Methodology

Our methodology is composed of a sequential two-step research design that utilises two methods for data collection and analysis in each step. We first conduct a fieldwork through open-ended interviews and use an inductive thematic analysis method to develop a grounded theory. In the second step we observe the relevance of emerging themes and our theory of reluctant local integration in the longer term by using a theory guided-process tracing method between 2015 and 2021. The following sections describe and reflect upon the operationalisation of each step including data collection, sampling techniques and analyses.

First step: grounded theory based on an inductive thematic analysis of open-ended interviews

Time and location

Our research started with a fieldwork in the city of Gaziantep that hosted the second biggest population of Syrians in Turkey in December 2014. This city was an ideal context because we were able to observe potential cultural frictions or positive relationships in a more palpable way than we could have done in cosmopolitan cities like Istanbul where people are more accustomed to diversity and cultural differences play a relatively less significant role in transactions. Syrians are also more scattered in cities like Bursa where they constitute only 6% of the population. Their presence and impact on the labour market and cultural relations in such cities is therefore not felt as much densely as it is in other places like Gaziantep and Hatay where Syrians respectively constitute 20 and 25% of the population (Multeciler Dernegi Citation2022).

Grounded theory approach

Case studies may contain a bias towards confirmation; that is, a tendency to verify the researcher’s predetermined notions (Creswell Citation2007). At the time of data collection, we did not have any pre-identified hypotheses to prove therefore we adopted a grounded theory approach, which is used to develop new theories and concepts grounded in data from the field. Our motivation was to conduct inductive research and develop a balanced understanding of wide variety of perceptions and experiences regarding the integration prospects of Syrians and perceptions of the local community that have an important role in this process. For this, we conducted open-ended interviews. We asked our participants from the local community how they experience the interaction with Syrians, what they make of the situation in legal, economic, and cultural terms, and if they would be okay if Syrians were to stay in Turkey for good. For interviews with Syrians, we also asked them about their relationship with the host community, their circumstances, grievances and whether they like to stay in Gaziantep/Turkey or move elsewhere.

Data collection, sampling technique and recruitment of interviewees

We conducted open-ended interviews with 106 people by using a snowball/’chain referral’ sampling method. Interviews were conducted in English, Turkish and Arabic. We ensured that the initial set of respondents was sufficiently varied in order to facilitate a diverse representation of both the host community and Syrians from different districts, age and gender groups, and financial backgrounds within the rest of our sample.

Characteristics of participants

We have interviewed 36 members of the local Turkish host community including 4 journalists, 10 local authorities called ‘muhtars’ and 10 of the residents living in their districts (both affluent and less wealthy areas of Gaziantep), 4 academics from Zirve University and 8 people who worked for ASAM (Association for Solidarity with Asylum Seekers and Migrants) in Gaziantep. All these participants representing the local community also acted as a gatekeeper and introduced us to those Syrians who then participated in this research. 70 of our participants were Syrians who fled their hometown as result of the war in Syria. We both interviewed our participants individually as well as in focus groups. Amongst our Syrian participants were 20 university students over 18. Some of them relied on scholarships provided by the EU as well as by universities they attended, and some were coming from families that are relatively well off. Other groups of Syrians we interviewed include 9 Syrian business owners who are financially secure as well as the 2 Syrian families (totalling to 13 people) who are struggling to meet ends and heavily dependent on welfare services and aid programs. We also had open-ended interviews and focus groups with 28 more Syrians who were involved in the workshops organised by ASAM. It is important to clarify here that Syrians are not recognised as refugees in Turkey (See section on guesthood). However regardless of their official status, all the Syrian participants we interviewed for this research were in Turkey at the time because they were escaping the war in Syria and all self-identified as a refugee. The 1951 Refugee Convention also spells out that a ‘refugee is someone who, owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted/killed for reasons of war race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality, and is unable to, or owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country’. We therefore by definition refer to our participants in this article as ‘Syrian refugees’. The nature and extent of services, rights and opportunities enjoyed by different groups of Syrians are mostly determined by their registration status as guests and their pre-existing economic conditions, whether they have enough capital to navigate through the economic hardships that come with their ‘guest’ status. We factor in the heterogeneity of our sample through direct reference to different characteristics when assessing the impact of different conditions such as employment, studentship, age, gender, ideology, ethnicity and economic status on integration experiences and prospects.

Ethical considerations

Three researchers received an ethics approval from Coventry University and then simultaneously collected data in Gaziantep. All our participants gave oral consent to participate, and their names have been anonymised for safety reasons. Each was later given a participant number for analysis. As part of the ethical considerations the investigators reflected on their positionality and formed a team of three researchers from different national, ethnic, religious and gender backgrounds to make sure that the data collection and analysis processes do not suffer from potential barriers between the researchers and participants.

Analysis of interviews

After the translation of all materials to English we conducted an inductive thematic analysis of our interviews, through identifying codes based on their frequency and meaning (sentiment) and then by clustering them into themes. We present more detail about the coding process and emerging themes in .

Table 1. Inductive thematic analysis of interview data (Sample No: 106).

Limitations and mitigation

We were aware of how short the time period that our observations covered through this fieldwork, and our observations were limited to Gaziantep. In order to mitigate time and space limitations, we decided to observe and analyse how some of the themes that we found out as a result of our fieldwork would play out in the longer term. This also enabled us to compare the findings of other scholars who followed up with more fieldwork beyond the city of Gaziantep where we had originally focussed on. We therefore used a follow-up, theory-guided process tracing method before we could come to a reliable and theoretical conclusion about the relevance of our findings.

Second step: theory-guided process tracing between 2015 and 2021

‘Process tracing focuses on the unfolding of events or situations over time. Hence, the descriptive component of process tracing begins not with observing change or sequence, but rather with taking good snapshots of specific moments’ (Collier Citation2011: 824). Our interviews in Gaziantep provided these important snapshots in 2014. Unlike the first step that was grounded in primary data and inductive, the second step is more aligned with a case study approach. It starts with pre-identified themes emerging from the first step and uses a theory guided process tracing (Falleti Citation2006) to deductively observe if and how our themes and our initial theory of reluctant integration have held up in time. We test the reliability and consistency of our findings in a broader context between 2015 and 2021, a period that represents changes and some continuity regarding the refugee movements, citizenship policies, economic conditions, access to education/health services and community relationships in the country. Our process tracing of these circumstances and their impact on the ‘reluctant local integration’ was made possible through the observation of further sources in the period following 2015 and included more recent empirical data from 2017, 2018, 2020 and 2021 that then informed our analysis. These data include UNHCR (Citation2020) ‘Syria emergency’ report, Erdogan (Citation2020) Syrians Barometer 2019 survey, Turkish Red Crescent and World Food Programme (Citation2019) survey on Refugees in Turkey, Carlo (2019) International Labour Organisation report on the Syrian Refugees in the Turkish Labour Market, Şimşek’s (Citation2018) findings on the class-based integration processes of Syrians in Turkey and more recent news content from Ihlas News Agency and Economist since 2017. The following pages offer an extrapolation of findings based on the combination of two phases of our research.

Findings and analysis

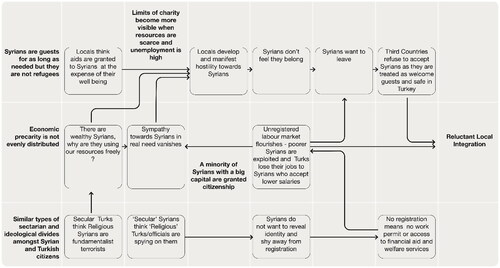

Some codes that lead to a certain theme can also be found in excerpts that are elaborated as part of other themes in the following pages. This points out to the links between and intertwined nature of themes that in combination present a picture of complex causality ().

Figure 1. Process of reluctant local integration.

Source: Author’s own work.

Ideological, sectarian, and ethnic polarizations in Turkey and their impact on reluctant integration

The societal aspects of local integration in terms of relations between the refugee and host communities require specific attention to make the process successful (Daley Citation2009). However, it needs to be noted that neither the local nor the refugee communities are homogenous. The division between secular and more religious groups in Turkey is a well-known factor that has shaped the political discourse as well as the community relationships in that country for almost a century (Çelik et al. Citation2017). Turkish nationalism in the early years of the Republic was a top-down constructivist attempt of social engineering aimed at forming one people out of many. However, it created a zone of conflict and a power struggle between the religious and secular, between the Kurds and Turks, between Alevis and Sunnis that would haunt Turkey for the duration of its entire existence (Kuzu Citation2019). Similarly, the same tension was also palpable in Syria. Syrian refugees are not a unanimous group and the conflict between them is what caused the intensive civil war back in their own country. Some escape from the Alawite regime of Bashir Assad, some of them escape from the ISIS. Those who flee the country are not only the Arabs but also the Kurds. Syrians are highly suspicious of each other in the first place and their distrust in each other reflects on their relationship with the Turkish community that is also divided along similar ideological, sectarian and ethnic lines.

What we used to observe between intra-groups in each community now seems to have an impact on inter-group community relationships between Turks and Syrians as well. Syrian interviewees in Gaziantep, especially the younger, well-educated ones who have a more secular outlook implied that sectarian differences might be sometimes invisible and subtle, but they play an important role in the background when it comes to community relationships. One of the Syrian students stated:

The cultural and ideological differences between myself and some other Syrians are also one of the determining factors why I find it difficult to engage with more religious Turkish groups in Gaziantep. (Participant 38)

We used to live in harmony in Syria before the war. Religious and ideological differences did not cause violence until fundamentalists exploited them. I see that those fundamentalists do exist in here too and this scares me. (Participants 45)

The majority of female Turks, who are strongly against the Islamic practice of polygamy, accuse single female Syrians for taking part in such practices. They think Syrians are a threat to the conventional concept of ‘family’ in Turkey and to their marriages. (Participant 15)

I don’t feel any enmity towards Syrian refugees; on the contrary, I want to help those who are in need. But I talked to some Syrian refugees with conservative, even fundamentalist, views and I know this worries a lot of secular Turks in Gaziantep. They don’t want those Syrians here. (Participant 3)

Here (in Turkey) there are many people threatened by ISIS or the regime. The regime has many members here. I want resettlement. I don’t feel safe here. I would like to go to the UK or Canada. Here there is an open border policy and Turks cannot control the border. So, they cannot protect us. People are using a different name. Even at their jobs, they are using a nickname. (Participant 16)

It is obvious that there are similar ideological polarisations amongst Syrians and Turks and now these polarisations are replicated and amplified in the relationship between refugees and the host community in Gaziantep as well. Sectarian tensions are observed in places beyond Gaziantep. For example, ‘the large Alawite population in the border towns of Hatay strongly opposes the rising numbers of Sunni Syrians settling in the town’ (Icduygu Citation2015). Following the fieldwork in 2014, our process tracing of this important factor in different locations through the analysis of media channels and newspapers in Turkish and English in 2017 also supported the relevance of this finding in the longer term and in locations other than Gaziantep. For instance, the Alawite population just outside the Turkish city of Kahramanmaraş protested the presence of a refugee camp there in 2016 because of their suspicion towards the Sunni refugees and the apprehension of sectarian tensions (Ihlas Haber Citation2017). The Economist (Citation2017) quotes a Turkish human rights activist, saying ‘Alawites think the refugees are jihadists, and the refugees think the villagers are Assad supporters’.

It is not our aim to show that these ideological, ethnic and sectarian polarisations are seen and felt equally everywhere in Turkey. It is likely that these divisions are felt more in smaller places close to the border than more developed and diverse cities like Istanbul and Izmir in the West of the country. However, compared to 542. 045 Syrians in Istanbul and 184.298 in Bursa, 1.583.149 Syrians in smaller cities such as Gaziantep, Hatay, Sanliurfa, Adana and Kilis seem to represent a bigger portion of Syrians and their experience in Turkey (Multeciler Dernegi Citation2022).

Having been pushed out of where they are not welcome Syrians are desperate to move on into the other parts of the country. In the process they are dragged from one place to another. This is also why tracking the registration of Syrians in Turkey is much more difficult than it would have been in another country that is not as culturally and politically divided along the same lines as the Syrian community.

Uneven economic precarity and its link with reluctant integration

‘The Turkish state, which provides both camp-based services and assistance to urban refugees, finds itself shouldering a significant financial burden: by early 2015 the cost had reached more than US $5 billion, of which the international community covered some 3%’ (Icduygu Citation2015:1). It is claimed that in 8.5 years Turkey spent close to $37 billion. However, majority of Syrians continue to find themselves in a dire financial difficulty. This section will elaborate on how the ‘liberal refugee policies’ in Turkey have had a discrepant effect on different segments of Syrian refugees.

In 2019, the monthly minimum wage in Turkey was 2,020 Turkish liras (TL) after taxes. However, according to the ‘Refugees in Turkey: Livelihoods’ survey findings conducted by the Turkish Red Crescent and World Food Programme in 2019 ‘Syrians with regular jobs averaged 1,312 TL, the 54% who were irregular workers made 1,058 TL. Also, 1.6 million of the most vulnerable refugees are supported by the EU-funded Emergency Social Safety Net providing 120 TL monthly per family member’ (Karasapan Citation2019) this has increased to 230 Turkish Lira (around €12.5) monthly per family member in 2022.

Minimum wage compliance presents a more sinister picture when examined from an hourly point of view. The International Labour Organisation report by Caro (Citation2020) reveals that ‘Syrians tend to work more than the 45 hours required to earn a full-time salary and, as a result, 3 out of 4 Syrian employees earn less than the minimum wage per hour. On average, Turkish natives earn 63.1% more than Syrians’ (Caro Citation2020:19). One of the most straightforward answers as to why Syrian refugees desire to leave Turkey would be the economic hardship that they can no longer survive in the country. Today it is a part of the daily routine in Turkey to see hundreds of homeless Syrians in despair on the streets. An extended family of eight Syrians residing together in a flat expressed the difficulty of finding accommodation not only because they can hardly afford it but also because the locals do not want to rent their flats to Syrians.

Nobody wants to rent their flat to us, they say we are too big of a family and will damage their property, but the reality is that we cannot afford a bigger property or rent two. Although we have a roof above our head it is less than ideal and taking its toll (Participant 42)

Alongside the problems with accommodation, the arrival of Syrians has been a big problem for the job market too. Turkish community has increasingly raised concerns over Syrians working illegally for below minimum wage and without any social security driving Turks out of the labour market. According to the survey findings of a report investigating the economic effects of Syrians on Turkey by ORSAM (Citation2014:17) 40% to 100% of the people who lost their jobs in border cities believe that they lost their jobs because of Syrians.

The same study also states that in November 2014, the unemployment rate reached double digits with a rate of 10.1% and it is possible that Syrians entering the job market has also influenced the unemployment rates in Turkey. Tumen (Citation2016:1) documents ‘moderate employment losses among native informal workers, which suggests that they are partly substituted by refugees’. This results in hostility between the communities. One unemployed Turkish person we interviewed stated that:

Syrians work illegally for below minimum wage and without any social security driving us out of the labour market. I don’t think they should be here. We like our guests, but some Syrians are not even poor and do not deserve our sacrifices. (Participant 8)

Those Syrian refugees who did not present their passports to the officials could not be given residency permit and those who did not hold a residency permit could not apply for a work permit either. There are several reasons as to why Syrian refugees do not register with the police. Some have lost and some did not have time to collect their passports while leaving their houses under attack. ‘19% of people entered Turkey on a passport, 3% through a border crossing but without a passport, and 78% via other routes’ (ASAM Citation2014). As a result of this process, only a total of 132,497 out of more than 5 million Syrian nationals were granted a work permit in Turkey between 2016 and 2019 (Revel Citation2020). However, Erdogan (Citation2019) explains that 1.2 million Syrians in Turkey are still in employment making 95% of them illegal workers with no rights. We have already elaborated on socio-cultural reasons for shying away from registration but as far as its relationship with work permits in the long term is concerned an interview we had with a Syrian Kurd before the work permits were introduced signalled that some Syrians would continue to work illegally for less money because they fear that if they document their identity now, this information can be used against them in the future.

I do not want to reveal and document my identity here when registering with the officials or applying for a work. I cannot trust the officials here. I know they have their opinions about Kurds. If they decide to send some of us back to Syria, I don’t want to be the first one. (Participant 44)

The informal labour market seems to be taking advantage of poor Syrians who may also have cultural/political reservations for registration that is crucial for attaining work permit. This implies that the so-called liberal refugee policies create an economic system of structural inequality in which many Syrians are practically turned into modern day slaves (Pelek Citation2019).

The possible contribution that Syrians might be making to the Turkish economy seems to benefit only the Turkish business owners (Belanger and Saracoglu Citation2020) not most Turkish citizens who have been expected to pay their taxes on an increasingly higher rate to finance public expenditure a great deal of which was seemingly spent on Syrians. One of the Turkish business owners we interviewed expressed content by stating that

Syrian workers are good for my business. They work hard and don’t ask for much money. (Participant 18)

The 2016 amendments to the Turkish citizenship law facilitated a process that granted citizenship to Syrians on the condition that they make a capital investment of at least 2 million USD in Turkey; or purchase property worth at least one million USD and secure employment for at least 100 workers (Akcapar and Simsek Citation2018:180). Inequalities emerging as a result of these policies also manifest themselves in the levels of integration for different segments of refugees. Şimşek (Citation2018) argues that Syrian refugees in Turkey go through ‘class-based integration’, which is in favour of refugees who have the capital. This leaves out refugees who are unskilled and do not have economic resources to invest in the receiving country but still find that they must continue living there. This development has strengthened our initial findings that economic precarity is not evenly distributed and those whose poverty is protracted are the ones who find they must reluctantly integrate into a system that cannot give them citizenship unless they financially contribute to the economy in significant measures.

The impact of ‘guesthood’ status on reluctant integration

Turkey is a signatory to the 1951 Geneva Convention and its 1967 Additional Protocol on the status of refugees, but it has maintained a geographical limitation that grants asylum rights only to Europeans. The 2013 Law on Foreigners and International Protection clarified conditions for submitting an asylum claim in Turkey, but maintained the geographic limitation of the 1951 Geneva Convention. Turkey has been reluctant to accept asylum seekers for resettlement from non-European countries ‘after the mass influx of close to 500,000 refugees fleeing ethnically targeted violence in northern Iraq’ (Icduygu Citation2015). As a result, Syrians have been accepted to Turkey and allowed to stay in the country for unlimited duration as guests and not refugees (Abdelaaty Citation2019). Having been deprived from refugee rights, millions of Syrians have also been left in a limbo with no prospects for what comes next (Ineli-Ciger Citation2017). They do not have guaranteed rights to social security, health services, education or employment all of which has been offered to them as a gesture of goodwill as explained above. As promising as it looks at first sight, the state of uncertainty that accompanies the generous open-door policy of Turkey is one of the most prominent factors leading the Syrians to seek asylum in Europe more and more often every day. This has been evident through Syrians’ reluctance to learn the Turkish language, as they are not sure if they will even stay in the country and need to use the language for the rest of their lives. Most of those young Syrian interviewees we spoke to in Gaziantep are educated to university level and have expressed their interest in moving up to Europe by pointing out:

I don’t see Syria being stable any time soon. And most of us cannot go back. Working with NGOs, we have question marks over our names. I don’t think it is easy to put an end to a life I have been working on and go back to zero. But the obstacle here is the legal situation. I don’t want to be a guest the rest of my life either. (Participant 60)

Looking at it from the perspective of Syrian families, there are reasons why they are not sending their children to school. A lack of interest in registering with authorities for cultural reasons is one of them as explained above. This is compounded by the fact that Syrian families want their children to work instead of going to school because they know that they are guests which means they will need to leave one day, and that they need to save money for what is to come. One of the poorer Syrian participants stated that

To me, being a guest means that we will need to leave sooner or later. I don’t think I can ever go back to Syria. In the meantime, I need to save money to take my family to Europe. Everyone in the family, even the children are doing their best to earn money now instead of going to school. (Participant 52)

Looking at the status of ‘guesthood’ from the locals’ perspective, some of the Turkish people we interviewed in poorer areas of Gaziantep were convinced that everything allocated to the Syrians from the treasury is being taken away from them. The tension is especially relevant in areas such as education, health and employment where there is a remarkable scarcity of the resources available to Turkish people in the first place (Özerim and Tolay Citation2020). The problem is also accelerated by the fact that precarity is distributed unevenly and there is also a group of wealthy Syrians living in Turkey alongside the poor. As a result of this, there is a widespread perception that Syrians are living a good life as guests and they do not have a reasonable ground to freely use welfare services that are already under pressure in Turkey. One of the wealthier Syrian interviewees we spoke to said

Our house in Syria is a 1-million-dollar house. But we are also refugees here. And some people are destitute, living in the street. People say, ‘If you are refugee then why are you sitting in a café’. But just because you are a refugee, you are not necessarily poor. I am not here because I am poor. I am here because I cannot go back to a country that is in war. (Participant 40)

The antagonistic approach of local community towards Syrians in Gaziantep was intensified by the fact that a group of Syrians were commuting between Turkey and Syria and by a consequential perception that those very Syrians had no legitimate ground to use the services provided to them in that city. This was evident in our interviews with Muhtars as one of them stated

Syrian refugees living outside the camps travel back and forth between Turkey and Syria. Some of these people do not cross the border because they flee their home country out of fear of death or execution, but because they would like to take advantage of the employment opportunities and health services available to them here. Residents in my district often complain about those Syrians who abuse our hospitality and welfare services that are already under huge pressure. (Participant 25)

The government narrative and policy that Syrians are ‘Guest’ leads to the perception that what Syrians get as ‘guests’ in Turkey are not their right but a gesture of good will that has its limits. In dire circumstances of decreasing public spending on welfare services and of increasing unemployment, Syrians are seen as a burden on the host society and welfare state (Morgűl and Savaşkan Citation2021). This perception of burden translates into an increasing level of antagonism that Syrians face daily. As a result, they desire to seek resettlement in European countries but the same system of ‘guesthood’ that allows Syrians to stay in Turkey for unlimited time makes it impossible for Syrians to do this legally. European countries use the system of ‘guesthood’ in Turkey to justify their refusal to accept Syrians from Turkey as ‘refugees’ because they are no longer escape the war and that their lives are no longer in danger while in Turkey where they can move freely, work and live outside camps. ‘Guesthood’ creates a context and a process in which Syrians stay put in Turkey reluctantly as they have no other option.

Conclusion

Following the sheer number of Syrian refugees who have been stranded in neighbouring countries such as Turkey and Lebanon, there has been acceleration in studies focussing on the merits of hosting refugee populations in these countries. Liberal refugee policies in Turkey that allowed Syrians to stay and work there were more than often praised by international organisations. Cultural similarities between Syrians and Turks were also interpreted by an increasing number of scholars as a positive dynamic that eases integration. We have analysed why this picture presents a stark contrast to the reality on the ground that almost 40% of Syrians still would like to resettle in a third country. In order to solve this puzzle, we have introduced a new concept of ‘reluctant local integration’, which suggests that a certain number of refugees who choose to stay and work in Turkey or learn the Turkish Language cannot or should not be considered as a reliable indicator of successful integration or refugee crisis management in Turkey. Majority of Syrians who stay in Turkey are doing so reluctantly as they have no other choice.

It is true that Turkey needs to be praised for its open-door policy and willingness to help its neighbours, but the country’s socio-economic and cultural fabric has its limits and it is often overlooked at what cost Turkey is presented as a successful and desirable arena to manage refugee crises.

The article showed that a significant percentage of Syrians who refrain from registration for cultural reasons and proximity to the on-going conflict in Syria increasingly suffer from protracted poverty especially in less cosmopolitan border cities such as Gaziantep where Syrians constitute more than 20% of the population. They are inadvertently locked into a system of inequality and turned into modern day slaves by liberal refugee policies that only favour those who have the capital.

Turkey may decide to recognise Syrians as refugees in the future in order to open legal routes for possible resettlement in third countries and to create a public perception that Syrians as refugees have rights granted by international law which cannot/should not be violated. However, having already spent billions for its Syrian ‘guests’, Turkey cannot embrace the financial cost of further employment, educational and housing benefits that would come with the refugee status to the Syrians in the country.

Even if it could, a significant portion of Syrians in Turkey are still not taking advantage of housing and educational opportunities to integrate when there is an increasing spending on the education and housing of Syrians in Turkey. Our study showed that it is not only the ‘guesthood’ status or economic difficulties that discourage Syrians from integrating into the Turkish community, but it is also their lack of interest to register with authorities in Turkey and mix with its broader society for socio-cultural and ideological reasons.

Broader significance of ‘reluctant local integration’ for scholarship and policy making

The significance of the study is especially for the broader scholarship on acculturation and similarity-attraction theories arguing that cultural similarity eases integration. This study shows that cultural similarities may be positively important in integration processes, but its role depends on the context and nature of the ‘culture’ at stake. When refugees escape from a war the root cause of which is a culture of ideological and sectarian polarizations, it becomes questionable to argue that they would appreciate finding a similar culture of polarisation in their final destinations. The existing literature that presents a positive picture of integration in Turkey due to cultural similarities and shared religion overlooks what is in fact a polarised environment between subgroups that protract the vulnerability of Syrians. Our study raises the point that the culture of sectarianism and ideological polarisations that may negatively affect registration processes, the distribution of employment opportunities and access to social services might be a distinctive feature of neighbouring countries like Turkey making them characteristically less of an ideal environment for the accommodation of refugees to start with. Although the concept of ‘reluctant local integration’ is grounded in data from Turkey, the paper introduces an important phenomenon that can be applied and generalised to similar contexts in neighbouring countries such as Jordan and Lebanon.

Our findings have also significant policy implications for the governance of refugee crisis through temporary protection in neighbouring countries such as Turkey. The example of Turkey shows that whilst the international actors seem to be benefiting from keeping Syrians in Turkey as ‘guests’ (Stel Citation2021) the human cost that many Syrians and Turkish citizens pay for is increasing. Neither Turkey’s unwavering efforts to shoulder the economic burden on its own nor the international aid offered to refugees in that country can rectify the divisive socio-cultural dynamics that lead to reluctant local integration and protracted vulnerability of many Syrian refugees there. Organisations such as the EU and the UN should start taking more responsibility in accommodating Syrians in contexts that are not as conflicted, divided and financially burdened as neighbouring countries like Turkey.

Acknowledgements

An earlier version of the paper was presented during the 2017 British Society for Middle Eastern Studies Conference at Edinburgh University and Inaugural Annual Workshop of the Near East Institute in Cyprus on South-South Migration and Post National Citizenship in the MENA Region in 2021. We would like to thank the participants in these events for their valuable feedback. We also would like to thank the anonymous reviewers and editors of Third World Quarterly for their invaluable comments and suggestions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Durukan Imrie-Kuzu

Dr. Durukan Imrie-Kuzu is Associate Professor of Politics at Coventry University. He is the author of Multiculturalism in Turkey (Cambridge University Press) and an editor of Nations and Nationalism based at the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Alpaslan Özerdem

Prof. Alpaslan Özerdem is Professor of Peace and Conflict Studies at George Mason University and Dean of Jemmy and Rosalynn Carter School for Peace and Conflict Resolution. He is a co- editor of the 2019 Routledge Handbook of Turkish Politics and an editor of Edinburgh Studies on Modern Turkey.

Notes

1 We have conducted a systematic review in January 2022 by using the search string “reluctant local integration” on CIAO (Columbia International Affairs Online), Academic Search Complete, ASSIA (Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts); Sage Premier; ScienceDirect; SCOPUS; SSRN (Social Science Research Network) Open Grey; BASE (Bielefield Academic Search Engine); NDLTD (The Networked Digital Library of Theses and Dissertations). Our review confirmed that the concept and phenomenon it describes has not been studied so far in the context of refuges.

Bibliography

- Abdelaaty, L. 2019. “Refugees and Guesthood in Turkey.” Journal of Refugee Studies 34 (3):2827–2848. doi:10.1093/jrs/fez097.

- Ager, A., and A. Strang. 2008. “Understanding Integration: A Conceptual Framework.” Journal of Refugee Studies 21 (2):166–191. doi:10.1093/jrs/fen016.

- Akcapar, S. K., and D. Simsek. 2018. “The Politics of Syrian Refugees in Turkey: A Question of Inclusion and Exclusion through Citizenship.” Social Inclusion 6 (1):176–187. doi:10.17645/si.v6i1.1323.

- ASAM. 2014. Rapid Needs Assessment of Gaziantep Based Syrian Refugees Survey Results, https://documents.wfp.org/stellent/groups/public/documents/op_reports/wfp2 3947.pdf.

- Belanger, D., and C. Saracoglu. 2020. “The Governance of Syrian Refugees in Turkey: The State-Capital Nexus and Its Discontents.” Mediterranean Politics 25 (4):413–432. doi:10.1080/13629395.2018.1549785.

- Baban, F., S. Ilcan, and K. Rygiel. 2017. “Syrian Refugees in Turkey: Pathways to Precarity, Differential Inclusion, and Negotiated Citizenship Rights.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 43 (1):41–57.

- Berry, J. W. 1997. “Immigration, Acculturation, and Adaptation.” Applied Psychology 46 (1):5–34.

- Blair, C., G. Grossman, and J. M. Weinstein. 2020. “Forced Displacement and Asylum Policy in the Developing World.” International Organization 76 (2):337–378.

- Brown, R. J. 1984. “The Effects of Intergroup Similarity and Cooperative vs. competitive Orientation on Intergroup Discrimination.” British Journal of Social Psychology 23 (1):21–33.

- Caro, L. P. 2020. “Syrian Refugees in the Turkish Labour Market’ ILO Office in Tukey. Caro, L.P., 2020. Syrian Refugees in the Turkish Labour Market: A Socio-Economic Analysis.” Sosyoekonomi 28 (46):51–74.

- Çelik, A. B., R. Bilali, and Y. Iqbal. 2017. “Patterns of ‘Othering’ in Turkey: A Study of Ethnic, Ideological, and Sectarian Polarisation.” South European Society and Politics 22 (2):217–238.

- Collier, D. 2011. “Understanding Process Tracing.” Political Science & Politics 44 (4):823–830.

- Crawley, H., and K. Jones. 2021. “Beyond Here and There:(Re) Conceptualising Migrant Journeys and the ‘in-between.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 47 (14):3226–3242.

- Creswell, J. W. 2007. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Traditions (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Crisp, J. 2004. The Local Integration and Local Settlement of Refugees: A Conceptual and Historical Analysis. Geneva: UNHCR, Evaluation and Policy Analysis Unit.

- Daley, C. 2009. “Exploring Community Connections: community Cohesion and Refugee Integration at a Local Level.” Community Development Journal 44 (2):158–171.

- Erdogan, M. 2014. ‘Syrians in Turkey: Social Acceptance and Integration Research’. Available at https://mmuraterdogan.files.wordpress.com/2014/12/hugo-report syrians-in-turkey-social-acceptance-and-integration-november-201404122014 en1.pdf.

- Erdogan, M. 2019. ‘Turkiye’deki Suriyeli Multeciler’ (Syrian Refugees in Turkey). Konrad Adenauer-Stiftung Report: 1–25.

- Erdogan, M. 2020. Syrians Barometer 2019: A Framework for Achieving Social Cohesion with Syrians in Turkey. Ankara: Orion Kitabevi.

- Ertorer, S. E. 2021. “Asylum Regimes and Refugee Experiences of Precarity: The Case of Syrian Refugees in Turkey.” Journal of Refugee Studies 34 (3):2568–2592. doi:10.1093/jrs/feaa089.

- Falleti, T. G. 2006. “Theory-Guided Process-Tracing in Comparative Politics: something Old, Something New. Newsletter of the Organized Section in Comparative Politics of the American.” Political Science Association 17 (1):9–14.

- Icduygu, A. 2015. ‘Syrian Refugees in Turkey: The Long Road Ahead’. DC: Migration Policy Institute. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/research/syrian-refugees-turkey long-road-ahead.

- Ihlas Haber, A. 2017. ‘Kahramanmaraş’ta Köylülerden Mülteci Kampı Eylemi’ (Villagers’ protests against Refugee Camps in Kahramanmaras) https://www.haberler.com/kahramanmaras-ta-koylulerden-multecikampi eylemi 8204995haberi/.

- Ineli-Ciger, M. 2017. “Protecting Syrians in Turkey: A Legal Analysis.” International Journal of Refugee Law 29 (4):555–579. doi:10.1093/ijrl/eex042.

- Karasapan, O. 2019. “Turkey’s Syrian Refugees-the Welcome Fades.” Future Development Brookings Turkey’s Syrian refugees—the welcome fades (brookings.edu)

- Kaya, A. 2017. “Istanbul as a Space of Cultural Affinity for Syrian Refugees: “Istanbul is Safe despite Everything!.” South-Eastern Europe 41 (3):333–358. doi:10.1163/18763332-04103003.

- Kavak, S. 2016. “Syrian Refugees in Seasonal Agricultural Work: A Case of Adverse Incorporation in Turkey.” New Perspectives on Turkey 56:185–185. doi:10.1017/npt.2017.1.

- Kılıçaslan, G. 2016. “Forced Migration, Citizenship, and Space: The Case of Syrian Kurdish Refugees in İstanbul.” New Perspectives on Turkey 54:77–95. doi:10.1017/npt.2016.8.

- Kuzu, D. 2019. “The Politics of Turkish Nationalism: Continuity and Change.” In The Routledge Handbook of Turkish Politics (69–80. New York: Routledge.

- Mahia, R., R. de Arce, A. A. Koç, and G. Bölük. 2020. “The Short and Long-Term Impact of Syrian Refugees on the Turkish Economy: A Simulation Approach.” Turkish Studies 21 (5):661–683.

- Migration Policy Centre (MPC). 2014. ‘Syrian Refugees’. http://syrianrefugees.eu.

- Morgül, K., and O. Savaşkan. 2021. “Identity or Interests? Religious Conservatives’ Attitudes to Syrian Refugees in Turkey.” Migration Studies 9 (4):1645–1672. doi:10.1093/migration/mnab039.

- Dernegi, M. 2022. ‘Number of Syrians in Turkey.’ https://multeciler.org.tr/eng/number-of-syrians-in-turkey/.

- ORSAM. 2014. ‘Effects of the Syrian Refugees on Turkey’ http://www.orsam.org.tr/en/enUploads/Article/Files/201518_rapor195ing.pdf

- Oner, N., A. Sirin, and H. D. Genc. 2015. “Vulnerability Leading to Mobility: Syrians Exodus from Turkey.” Migration Letters 12 (3):251–262. doi:10.33182/ml.v12i3.278.

- Osseiran, S. 2020. “The Intersection of Labour and Refugee Policies in the Middle East and Turkey: exploring the Dynamics of “Permanent Temporariness.” Civil Society Review 4 (2):94–112.

- Özerim, M. G., and J. Tolay. 2020. “Discussing the Populist Features of anti-Refugee Discourses on Social Media: An anti-Syrian Hashtag in Turkish Twitter.” Journal of Refugee Studies 34 (1):204–218. doi:10.1093/jrs/feaa022.

- Özden, Senay. 2013. Syrian Refugees in Turkey Available online: http://cadmus.eui.eu/bitstream/handle/1814/29455/MPC-RR-2013%2005.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- Pelek, D. 2019. “Syrian Refugees as Seasonal Migrant Workers: Re-Construction of Unequal Power Relations in Turkish Agriculture.” Journal of Refugee Studies 32 (4):605–629. doi:10.1093/jrs/fey050.

- Poslon, X. D., and B. Lasticova. 2019. “The Silver Lining between Perceived Similarity and Intergroup Differences: Increasing Confidence in Intergroup Contact.” Human Affairs 29 (1):63–73. doi:10.1515/humaff-2019-0006.

- Revel, B. 2020. “How to maximize Syrian refugee economic inclusion in Turkey” Atlanti Council. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/turkeysource/how-to-maximize syrian refugee economic-inclusion-in-turkey/

- Rottmann, S., and A. Kaya. 2021. “We Can’t Integrate in Europe. We Will Pay a High Price I we Go There’: culture, Time and Migration Aspirations for Syrian Refugees in Istanbul.” Journal of Refugee Studies 34 (1):474–490. doi:10.1093/jrs/feaa018.

- Şafak-Ayvazoğlu, A., F. Kunuroglu, and K. Yağmur. 2021. “Psychological and Socio-Cultural Adaptatiof Syrian Refugees in Turkey.” International Journal of Intercultural Relations 80:99–111.

- Şimşek, D. 2018. “Integration Processes of Syrian Refugees in Turkey: ‘Class-Based Integration.” Journal of Refugee Studies 33 (3):537–554.

- Stel, N. 2021. “Uncertainty, Exhaustion, and Abandonment beyond South/North Divides: Governing Forced Migration through Strategic Ambiguity.” Political Geography 88:102391.

- The Economist. 2017. ‘The new neighbors: Turkey is taking care of refugees but failing to integrate them’ https://www.economist.com/europe/2017/06/29/turkeyis-taking care of-refugees-but-failing-to-integrate-them.

- Tumen, S. 2016. “The Economic Impact of Syrian Refugees on Host Countries: Quasi- Experimental Evidence from Turkey.” American Economic Review 106 (5):456–460.

- Turkish Red Crescent and World Food Programme. 2019. Refugees in Turkey: Livelihoods Survey Findings. Ankara, Turkey.

- UNHCR. 2015. Syrian Refugees Regional Responses. http://www.unhcr.org/pages/49e48e0fa7f.html

- UNHCR. 2020. ‘Syria emergency’. t https://www.unhcr.org/syria-emergency.html

- World Food Program. 2021. ‘Country Brief Turkey’. https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/2021%2004%20Turkey%2 Country%20Brief.pdf

- Van Oudenhoven, J. P., C. Ward, and A. M. Masgoret. 2006. “Patterns of Relations between Immigrants and Host Societies.” International Journal of Intercultural Relations 30 (6):637–651.

- Yitmen, Ş., M. Verkuyten, B. Martinovic, and M. Erdoğan. 2022. “Acceptance of Syrian Refugees in Turkey: The Roles of Perceived Threat, Intergroup Contact, Perceived Similarity and Temporary Settlement.” In Examining Complex Intergroup Relations, 150–174. New York: Routledge.