Abstract

How do external actors promote regional international organisations (RIOs) through their regional foreign aid? Whereas most leading theories of regionalism stipulate that RIOs are designed and shaped by intra-regional actors from ‘within’, this study develops a novel framework for exploring donor involvement in RIOs during various stages of the foreign aid policy cycle. The research design is based on a comparison of the four largest European donors of regional foreign aid (EU, Germany, Sweden and the UK) towards the largest recipient in Africa (African Union). The comparative analysis reveals considerable variation and each donor employ their own distinct approach, which we conceptualise as Bully (EU), Overseer (UK), Micromanager (Germany) and Samaritan (Sweden). This comparative design enables us not only to escape the EU-centrism that currently distorts the research field but also to analyse the different ways by which European donors try to influence and even control RIOs in Africa through their foreign aid. The deep donor involvement in RIOs in Africa challenges us to rethink external intrusion, the meaning of ownership as well as conventional boundaries of ‘inside’/’outside’ in the study of regionalism.

Introduction

While most scholars maintain that regional international organisations (RIOs)Footnote1 are driven and shaped from ‘within’ by intra-regional actors (Mattli Citation1999; Börzel and Risse Citation2016), a growing literature emphasises external pressures and the role of external actors (Katzenstein Citation2005; Krapohl Citation2017; Lenz Citation2021). To date, however, most research has concentrated on a limited set of external actors – first and foremost the European Union (EU), the United States and to a lesser extent China – and how they have used their resources and international status to either foster or undermine regional cooperation and integration in their neighbourhood and further afield (Diez and Tocci Citation2017; Söderbaum Citation2016). Previous research has to a considerable extent overlooked other external actors (such as Germany, United Kingdom, Sweden) as well as the importance of foreign aid in the promotion of regionalism from the ‘outside’.

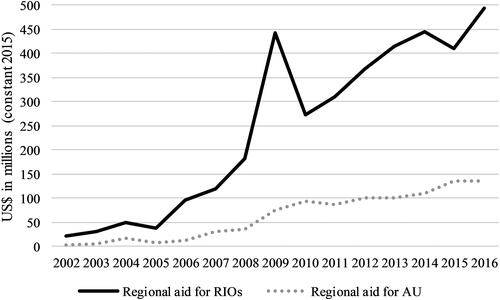

These omissions are problematic for at least three reasons. First, most scholarship disregards the fact that the promotion of regionalism from the outside is often causally linked to external funding. Although regional official development assistance (ODA) remains rather limited compared to the amount of country-based ODA, it is often indispensable to many RIOs in the Global South, especially in Africa.Footnote2 In fact, external funding amounts to between 50% and 70% of the budgets of the most prominent RIOs in Africa (Engel and Mattheis Citation2020). This neglect has become increasingly problematic with the increase of regional foreign aid during the last two decades. As shown in , African RIOs have received a total of US$3.7 billion in regional ODA between 2002 and 2016, spread over 4,348 projects, from a considerable number of donors. The African Union (AU) stands out as the most pronounced recipient of such aid, receiving roughly US$950 million during this time period and US$135 million in 2016 alone.

Figure 1. Regional ODA to African RIOs and the African Union, 2002–2016 (US$ million).

Source: authors’ dataset.

Second, although it is well-known that many RIOs in the Global South – not least in Africa – are aid-dependent, little is still known about the scope and nature of foreign aid to RIOs and the different ways donors promote and become involved in the activities of RIOs.

Third, research on regional foreign aid in Africa is EU-centric and there are very few studies on donors other than the EU. Although there is a rich literature on how donors promote and influence states from ‘outside’ (Whitfield Citation2009; Swedlund Citation2017; Honig Citation2018), there is virtually no corresponding research about how donors promote RIOs from the ‘outside’. Responding to this lacuna, this study explores the four largest European providers of regional ODA (the EU, Germany, Sweden and the UK) towards the largest recipient in Africa (the AU).

With inspiration from literature on the political economy of aid, we develop a framework that distinguishes donor involvement during two main stages of the foreign aid policy process: the policy design and the policy implementation phase. Empirically, we find that even if the four European donors share similar goals and strategies, they rely on strikingly different approaches in their involvement in the AU. The EU is deeply engaged but also intrusive in terms of its involvement in policy design and policy implementation. The UK also seeks strict control over policy design, but it is only indirectly involved during the implementation stage. Both Germany and Sweden remain passive during agenda setting and the policy design phase but differ sharply in their approaches regarding their involvement during the implementation stage. Germany has a massive field presence, whereas Sweden is only indirectly involved. On this basis, we identify four distinct donor approaches towards their involvement with the AU, which we refer to as Bully (EU), Overseer (UK), Micromanager (Germany) and Samaritan (Sweden). The study illuminates the variation in the way the four European donors promote and control RIOs in Africa through their foreign aid. Viewed in a broader perspective, the study challenges us to rethink the external involvement as well as the conventional boundaries of ‘inside’/’outside’ and members/non-members in relation to RIOs.

The study proceeds as follows. In the next section, we review and position ourselves in regard to previous research in the field of comparative regionalism and the finances of international organisations. In the third section, we develop our framework for the analysis of donor approaches towards recipient RIOs. In the fourth section, we justify the research design and our other methodological considerations. Thereafter, we analyse the varied patterns of European donor approaches towards the AU by comparing the four donors selected in this article. We conclude the article by outlining the implications of our results and sketching out avenues for future research.

Previous research

Promoting regionalism from the ‘outside’ is not a new phenomenon – although it has received rather limited attention compared to matters on the ‘inside’. Several bodies of literature have addressed how external actors play a role in the establishment, design and functioning of RIOs. First, some RIOs have colonial roots and were imposed by former colonial powers, such as the Southern African Customs Union (SACU) and the West African Economic and Monetary Union (UEMOA) (Bach Citation2016). Other RIOs have been promoted by major powers in their attempts to organise their neighbourhoods (Obydenkova and Libman Citation2019). Empirically, many studies in this field concentrate on a few powerful external actors, notably the USA, EU, China and Russia, and relatively few studies look into other powerful external actors, such as France and the UK (Mattheis Citation2022).

Second, studies of diffusion among RIOs highlight that decisions about institutions and policies are conditioned by prior decisions of other actors due to interdependent decision-making processes (Oksamytna and Wilén Citation2022; Stapel Citation2022). The overwhelming majority of studies treat the EU as the reference model, which either actively promotes its institutions and policies or passively serves diffuses to other parts of the world (Haastrup Citation2013; Lenz Citation2021).

Third, the debate around interregionalism also underlines the role of external actors, for instance through RIO-to-RIO or RIO-to-region cooperation and interaction (Hänggi, Roloff, and Rüland Citation2006). Again, most studies on interregionalism are EU-centric and focus strongly on the EU’s actions towards other RIOs and regions (Baert, Scaramagli, and Söderbaum Citation2014).

In short, these partly overlapping bodies of literature revolve around a limited set of external actors and how they use power and status to foster or undermine regional cooperation and integration. This study is motivated by the fact that previous research has often overlooked the role of foreign aid in the promotion of RIOs from the ‘outside’.

The modest attention given to foreign aid is surprising since the finances of regional and international organisations have attracted increasing scholarly attention in recent years (Graham Citation2015; Patz and Goetz Citation2019; Engel and Mattheis Citation2020). However, research in this field has concentrated heavily on internal revenues as opposed to external sources of funding. Scholars focus particularly on three sources of internal revenue: (i) direct and mandatory contributions from national budgets of member-states; (ii) voluntary contributions from national budgets of member-states, and (iii) direct supranational taxes (Boiar Citation2014; Ege and Bauer Citation2017). Recent studies have focussed on the drivers, processes and effects of internal revenue-generating principles, and how shifts from mandatory to voluntary contributions affect the authority, autonomy and governance structures of IOs (Graham Citation2017; Eichenauer and Reinsberg Citation2017). Wealthy actors leverage voluntary financial contributions to alter the policies and activities of international organisations according to their preferences and interests, for instance through trust funds and earmarked funding (Eichenauer and Reinsberg Citation2017).

By contrast, external funding comprises voluntary contributions from external actors that are not full members of these organisations (see also Jolliff Scott Citation2020). This type of funding applies mostly to RIOs in the Global South, which may help to explain why it has received so little interest compared to internal revenues. This omission is problematic since, as this study will show, external actors use foreign aid to become involved in the day-to-day activities of RIOs and shape their policies and activities in a range of ways which are hitherto poorly understood. Just like other forms of foreign aid, regional ODA to RIOs is deeply political and intrusive. Although donors officially declare that their funding is intended to ‘help’ and ‘assist’ recipients to build their ‘own’ RIOs, donors strategically decide who gets what, why, where and when. Each donor exercises discretion regarding which RIO it will fund, the designated policy field, which implementing partners will be involved, and what the intended (donor) goals should be. Therefore, donor strategies to RIOs deserve greater scholarly attention.

Framework

Given the near absence of relevant frameworks for the study of regional foreign aid to RIOs, we take inspiration from more general debates on donor strategies. A large body of literature identifies differences between donors in country-based foreign aid (Dietrich Citation2016; Schneider and Tobin Citation2016; Whitfield Citation2009). For instance, research on aid allocation often makes a fundamental distinction between a supply-driven logic headed by donors and a demand-driven logic focussing on recipient needs (Alesina and Dollar Citation2000; Hoeffler and Outram Citation2011). Literature on aid effectiveness and donor-recipient relationships stipulates rather similar distinctions between ‘donorship’, ‘ownership’, and various types of ‘partnership’ (Swedlund Citation2013; Brown Citation2017). Other literatures focus on the institutions that structure the delivery and implementation of foreign aid and the differences between top-down and bottom-up management of foreign aid (Honig Citation2018; Gibson, Andersson, and Shivakumar Citation2005).

With inspiration from these debates, we develop a framework that focuses on how donors get involved and engage with RIOs during two main stages of the foreign aid policy process. The term ‘involvement’ signifies that donors and recipients depend on each other, and that donors cannot impose their views and policies unilaterally and irrespective of recipient interests and preferences. We distinguish between ‘policy involvement’ and ‘implementation involvement’ (for a similar approach, see Swedlund Citation2017). The first phase focuses on the agenda and definition of policy goals. The second phase focuses on policy implementation, including the different aid modalities, accounting standards, planning methods and monitoring tools, and the development of specific bureaucratic routines as part of the delivery and implementation of regional foreign aid. Most literature in the field tends to be mainly concerned with only one of the phases of the aid policy cycle.

Policy involvement comes in two main forms. Active policy involvement occurs when donors seek to become actively involved in and shape recipients’ policy agendas in order to try to make recipients adjust agendas and policies to conform with the donors’ own aims and objectives (Whitfield Citation2009; Swedlund Citation2017). A passive stance towards the policy agenda and direction means that donors follow an approach that to a greater extent accords with the demands, needs and interests of recipients (when these are in alignment with their own interests) or do not expect that recipients’ policies are adjusted in return for external funding (when their own interests are not aligned with recipients’ demands). Nevertheless, even donors that pursue a passive approach get a ‘seat at the table’ and a ‘license to ask questions’ (Swedlund Citation2013, 365–367). In line with arguments of resource dependence (Pfeffer and Salancik Citation1978), these donors can still address a variety of issues that are in their strategic interests because simply providing resources has the effect of altering what recipients imagine they can do and plan to do along donor expectations.

Donor approaches also vary in the extent to which they seek to be involved during the implementation stage of the policy process (Swedlund Citation2017; Gibson, Andersson, and Shivakumar Citation2005; Honig Citation2018). Again, we distinguish between two main forms: direct and indirect implementation involvement. The former implies maximising the leverage over how, where and by whom external funding is spent, for instance, through control over aid modalities and implementation channels. Direct implementation involvement may also be exerted through rather rigid administrative rules and procedures and by results-based management frameworks. Donors sometimes even impose their own accounting standards, planning methods and monitoring tools or expect that recipients should harmonise their approaches with those of donors. Indirect implementation involvement entails a more lenient approach that allows for greater discretion and ownership on the part of recipients in the implementation of aid activities. It focuses on incremental capacity building rather than pushing for external experts within a tightly controlled project setting. The indirect involvement may still be focussed on results and aid effectiveness, but the approach usually contains a more long-term perspective than direct implementation involvement.

Policy and implementation involvement may unfold independently of each other. The configurations of active/passive involvement at the policy-design stage and direct/indirect involvement in the implementation results in four different donor approaches (see ). Active participation in defining the policy agenda may be accompanied by direct implementation involvement in one case (A), whereas it may be combined with an indirect approach towards implementation in another (B). When donors opt for passive participation in decision about the policy agenda, they may pursue direct (C) or indirect involvement (D) at the implementation stage.

Table 1. Policy and implementation involvement towards RIOs.

Research design and methodological considerations

This study concentrates on regional ODA as a source of external funding through which donors get involved with recipient RIOs (see fn. 2). The case selection of the AU is motivated by its role as the undisputed ‘donor darling’ among RIOs in Africa, and it is clearly the largest recipient of regional ODA in Africa. We therefore consider the AU to be the most relevant case for gaining more knowledge about different foreign aid approaches. The AU is also supported by a large number of ‘international development partners’, which implies that a single or few donors are unlikely to be able to dominate the organisation as might be the case of smaller or less resourceful RIOs.

The AU’s dependence on donor funding is well-known. By the end of the 2010s, donors contributed about 75% of the AU’s operating budget, and more than 90% of its program budget (Kagame Citation2017: 17). The AU’s extreme dependence on foreign aid has given rise to fundamental questions about donor penetration, autonomy, ownership, and the AU’s performance (Engel Citation2020; Stapel, Panke and Söderbaum, Citation2023; Söderbaum, Stapel, and Wennergren Citation2023). In a much-discussed report delivered to the AU Assembly in 2017, Rwandan President Paul Kagame fiercely opposed the over-reliance on foreign aid as it reinforces external control over the AU at the expense of African ownership (Kagame Citation2017, 13–15). Although intra-African funding has increased in recent years, the AU’s dependence on foreign aid will not disappear anytime soon. From this standpoint, it is essential to gain more knowledge about the different ways donors promote the AU from the outside through their regional foreign aid. The insights gained from the study of the AU will be relevant for other RIOs in Africa and beyond.

With regard to the selection of donors, European donors are particularly important. The EU, Germany, Sweden and the United Kingdom (UK) collectively contribute more than 80% of regional ODA to the AU. The ‘big four’ have defined comprehensive strategies and programmes towards the AU, stretching over long periods of time and covering a range of policy sectors. They belong to the most committed and most deeply involved AU donors (see Stapel et al. Citation2023). They nevertheless differ substantially with regard to design of aid activities and prioritised sectors (Söderbaum, Stapel, and Wennergren Citation2023). We therefore consider the ‘big four’ to be the most interesting from a theoretical point of view. While other bilateral and multilateral ‘international development partners’ also fund the AU, we consider them to be less suitable for comparison (see Söderbaum Citation2016). For example, although the US is the largest provider of regional ODA in Africa, it often prefers to work outside the frameworks of RIOs and its relationship with the AU is somewhat strained. Similarly, China has emerged as an important partner for the AU during the last decade, but it still remains selective in its approach towards the AU (see Alden et al. Citation2018). The fact that Chinese foreign aid is also compounded by secrecy further complicates comparisons with other donors.

The comparison builds on both quantitative and qualitative material. We have collected information about the prioritised sectors, size and type of funding, and the design of aid activities for each of the four donors. To this end, we draw on the OECD Development Assistance Committee database. We traced regional ODA activities that were reported to the Creditor Reporting System (CRS). The OECD data are highly respected and advantageous for its broad coverage, detailed information, and systematic assessment of donor activities and disbursements over extended periods of time. The database includes OECD countries as well as non-OECD countries who voluntarily share information about foreign aid, including Kuwait and Saudi Arabia. On the downside, the information is only systematically reported from 2002 onwards, and it is not possible to study previous ODA disbursements. The data collection for the database was concluded in 2018, when information was available only until 2016.

The quantitative data are complemented by a qualitative analysis of donor strategies, policy documents and more than 30 semi-structured interviews with both donors and recipients in Addis Ababa, Berlin, Brussels, London, Pretoria and Stockholm. Interviewees were selected through snowball sampling. We interviewed officials both in donor headquarters and in the field missions. On the recipient side, we interviewed high-level politicians and staff from the AU Commission as well as experts and non-state elites. Most interviews lasted between 60 and 90 min, and served to obtain information about motivations, objectives and interactions of donors and recipients. These data enabled us to examine how donors perceive themselves and how AU representatives perceive the donors at various stages of the policy cycle.

Donor involvement in the African Union: four approaches

Although the four donors adhere to the general goals and principles of supporting and helping the AU to achieve its own goals, they differ considerably with regard to prioritised sectors, size, type of funding, and project design (see ). They also differ in their involvement with the AU across the aid policy cycle. Each case study starts out with an introductory paragraph describing the general goals and basic features of each donor, and thereafter we analyse each donor in terms of policy and implementation involvement.

European Union

The 2007 Joint Africa–EU Strategy (JAES), the 2018 Memorandum of Understanding between the AU and the EU on Peace, Security and Governance, and the EU’s Joint Communication from 2020 ‘Towards a Comprehensive Strategy with Africa’ define the areas of common interest, goals and efforts (Haastrup Citation2013; Kell and Vines Citation2021). The EU’s interest in the AU and its activities is reflected both in the focus on particular issue-areas and in the large sums provided to the AU. The EU has allocated most of its US$191.5 million to the fields of governance (democracy, human rights), peace and security, and agriculture (also see Diez and Tocci Citation2017; Herrero and Gregersen Citation2016). Regional ODA is provided in the form of projects, programme support and technical assistance in a mix of stand-alone regional projects and large-scale support programmes (see ). Two EU programmes are particularly important: the AU Support Programme (AUSP; institutional capacity) and the African Peace and Security Architecture (APSA) Support Programme (peace and security).

Table 2. Overview of regional ODA to the African Union (2002–2016).

The EU is particularly active during the policy design phase. A number of EU as well as non-EU interviewees emphasise that the EU pursues active policy involvement, with rather straightforward demands and pressures on the AU’s governance procedures and institutional developments.Footnote3 The EU expects the AU and the AU Commission to align policies and strategies with those of the EU, especially in the peace and security sector. To this end, the AU Commission is required to regularly coordinate with EU staff and to hold meetings at ambassadorial level.Footnote4 The EU is viewed as the AU’s ‘most important’ and ‘strongest partner’ by the EU itself, its African counterparts and other donors.Footnote5 This widespread notion overlooks the fact that, between 2002 and 2016, Germany contributed more regional ODA to the AU than the EU (see ).Footnote6 Nevertheless, the EU’s involvement is ‘overwhelming’ and entails ‘multiple layers of influence’ at this stage of the aid policy cycle, both directly by the EU and in concert with some EU member states.Footnote7 As one AU Commission representative phrased it, the dependence on EU funding does not allow the AU to control the programs and agenda.Footnote8

The direct implementation involvement by the EU is not matched by any other donor. First, most of the EU’s contracts are designed and managed through a top-down approach that centralises decision-making to Brussels, by staff that lack direct experience of processes and procedures within the AU (Herrero and Gregersen Citation2016; European Court of Auditors Citation2018, 32). These processes favour the EU’s preconceived standards when it comes to project implementation, yet they also considerably prolong and delay implementation.Footnote9 Second, the EU staff in the field mission in Addis Ababa is closely involved in the implementation of aid activities, not least through various types of secondments (European Court of Auditors Citation2018, 32, 22–23). These externally funded employees are sometimes even viewed as potential ‘spies’ by African colleagues inside the organisation.Footnote10 Third, the EU maintains tight control over how resources are used by specifying administrative rules and procedures. Because the AU Commission frequently has ‘difficulties to present financing proposals of acceptable quality in due time’ (EU Commission Citation2018, 5–6), the EU seeks ‘to counter the institutional and operational weaknesses’ of the AU (European Court of Auditors Citation2018: 27).Footnote11 This external implementation involvement has become so comprehensive and intrusive so that both partners agree that neither can be satisfied with the situation.Footnote12 For instance, the AU Commission failed to meet the EU’s Seven Pillar assessment so that it could be entrusted with budget-implementation tasks and independent financial management. In 2015, the AU Commission did not fulfil these requirements in several areas (relating to internal control systems, accounting, independent external audits, and rules and procedures pertaining to grants, procurement and financial instruments). In order to continue the provision of external funding, the EU rather hastily put together an aide mémoire with the AU in April 2016, which was followed-up in May 2017. This document stipulated tightly controlled implementation tasks, an alignment of AU Commission financial management systems with EU standards, and provisions on financial spending. Progress in these areas needs to be reported at regular intervals.Footnote13 This package of control mechanisms highlight the direct implementation involvement exerted by the EU.

United Kingdom

The UK’s Regional Programme for Africa focuses on poverty reduction and economic development (DFID Citation2012, Citation2017). In the 2000s, British funding to the AU emphasised good governance, conflict prevention and general support of APSA (Apuuli Citation2018).Footnote14 The primary focus later shifted towards agriculture, environment and infrastructure. The UK takes a rather diversified approach, with funding spread evenly across these sectors. Moreover, most funding is disbursed in the form of short-term projects with time horizons of two years or less (see ). In general, the UK shows less enthusiasm for supporting the AU during the 2010s (Söderbaum, Stapel, and Wennergren Citation2023).

The UK has actively pushed for policy formulation and design at the AU Commission. In the past, when external funding to the AU focussed mainly on governance and peace/security, the UK expected both recognition and influence on account of its status as a permanent member of the UN Security Council.Footnote15 However, the UK’s actual policy influence remained limited, which led to frustration in British policy circles concerning the ‘politics’ of the AU (Söderbaum, Stapel, and Wennergren Citation2023). This resulted in a slow but steady shift of British support from the peace and security sector to the less politicised fields of infrastructure and agriculture during the 2010s.Footnote16 The UK seeks to make its voice heard in these policy areas and to shape policies that are in line with its own interests. Moreover, the UK prefers short-term, ad-hoc aid interventions (see ). These require less long-term planning and entail fewer, shorter negotiations with the AU. At the same time, because these policy areas are less politicised and bureaucratised, it is easier for the UK to steer the agenda in line with its preferences and to get actively involved in determining the policy directions of the AU.

British officials remain reluctant to become deeply involved in the implementation of aid activities, and the approach is thus one of indirect implementation involvement (Söderbaum, Stapel, and Wennergren Citation2023). First, since the UK has far fewer resources and staff compared to the EU and Germany, it is unable to maintain tight control over implementation, which gives the AU greater leverage at this stage of aid policy cycle. In contrast to EU practices, field officers do not regularly consult their headquarters in their day-to-day activities, for instance regarding contract management and project implementation.Footnote17 Second, external funding from the UK does not specify detailed implementation requirements. Nevertheless, the British approach is strongly geared towards results-oriented aid (Söderbaum, Stapel, and Wennergren Citation2023). In its engagement with the AU, it seeks to maximise the effectiveness of development cooperation and to create value for money (DFID Citation2012; D’Emidio and Wallace Citation2019). While the emphasis on concrete results reflects direct implementation involvement, there is still a considerable reluctance to become too deeply involved in the implementation. The UK manages to combine the results-oriented approach with indirect policy involvement through its emphasis on ad hoc and short-term funding. This enables the UK to stay away from implementation while at the same time maintain the possibility that funding can be quickly withdrawn if projects are not considered effective.Footnote18 Finally, while the AU is a strategic partner for the UK, the continental organisations is considered to be difficult and demanding. From the UK’s perspective, the political nature of the organisation makes it difficult to cooperate with. As one source put it: donors need to be directly involved in the implementation of projects in order to achieve positive and immediate results.Footnote19 The UK’s preference for limited implementation involvement helps to understand why the UK’s development cooperation department ‘does not want to work with the AU [and the regional economic communities] no more’.Footnote20 In fact, the UK’s approach has underwent a shift to either bypass the AU altogether or to support policy sectors that are less politicised, such as agriculture and infrastructure, where results can be achieved through policy involvement without too much involvement at the implementation stage.

Germany

Supporting regional integration is a cornerstone in Germany’s development cooperation with Africa (Auswärtiges Amt Citation2011, Citation2019; BMZ Citation2017) and ‘has become part of the German DNA by now’.Footnote21 The external funding focuses on governance and peace and security, and most of the US$278.7 million is distributed through long-term projects and programmes (see ). The AU is considered an important partner in the field of peace and security, good governance, economic integration, climate change, and sustainable development. Conflict prevention and resolution through the APSA, capacity-building, and strengthening institutions and frameworks therefore feature prominently in German support to the AU (Auswärtiges Amt Citation2019).Footnote22 Some projects – including the Capacity Strengthening of the AU Commission and the Support to the African Peace and Security Architecture – have undergone multiple rounds of restructuring and adjustments (see ).Footnote23

Germany follows the AU’s priority fields of interests outlined in the Agenda 2063 (Auswärtiges Amt Citation2019). Representatives from the German Ministry for Economic Cooperation (BMZ) and the German Corporation for International Cooperation (GIZ) often follow a recipient-centred approach according to which they focus on the demands of the AU and other recipient RIOs. As several interviewees pointed out, Germany provides external funding where support is needed or has been requested.Footnote24 In contrast to the EU and UK, Germany does not actively seek or demand policy adjustments according to its own preferences and its policies are instead very much geared towards the goals and objectives in the AU’s Agenda 2063 (Auswärtiges Amt Citation2019). However, in spite of the passive German approach, its support to the AU still comes with strings attached because ‘donors have their priorities’. Footnote25 Germany also supports the majority of Agenda 2063 objectives, but not all of them. Furthermore, Germany is frequently involved in planning meetings and expects its assessments to be heard and valued in discussions about policy and strategic directions. Because Germany provides external funding, German representatives have ‘a seat at the table’ and a ‘license to ask questions’ (Swedlund Citation2013, 365–367). This showcases passive policy involvement.

Germany prioritises involvement at the implementation stage. Since the AU and the AU Commission are considered ‘weak institutions’Footnote26 that are ‘not built to implement any kind of project’,Footnote27 they need support for institutional, financial and technical management during the implementation phase. Germany runs a number of large-scale support programmes for capacity-building and long-term institutional strengthening to overcome such implementation deficits. For these purposes GIZ staff and seconded staff are deeply involved over long periods of time and carry out implementation in close collaboration with staff at the AU Commission and other AU bodies, such as the African Union Development Agency-NEPAD.Footnote28 They facilitate the work between the AU and GIZ without compromising the confidentiality of information and documents.Footnote29 GIZ officials in Addis Ababa even claimed that they go every day in and out of certain AU Commission departments, which further underlines the active implementation involvement.Footnote30 Moreover, the projects and implementation entail detailed accountability, transparency and financial management requirements. Increasingly, the BMZ has shifted attention towards regular reporting on its aid activities, including audits and evaluations of effectiveness (‘Wirkungsprüfungen’).Footnote31 While also focussed on results, Germany’s understanding of results-based management differs considerably from the value-for-money approach of the UK. Indeed, the German approach to implementation is more similar to that of the EU as representatives maintain tight control during the implementation phase.

Sweden

The Swedish regional development cooperation strategies for sub-Saharan Africa assert that regional cooperation is necessary to deal with common transboundary challenges (Regeringskansliet Citation2010; Regeringskansliet Citation2016). Since its first regional strategy in 2002, Sweden has strongly emphasised the need to support and strengthen the AU and the most important RIOs in Africa, especially via capacity-building and demand-driven cooperation (Regeringskansliet Citation2010, 2, 7; Regeringskansliet Citation2016, 10; Söderbaum, Stapel, and Wennergren Citation2023). Swedish support concentrates mainly on peace and security, governance, and the environment, with a mix of core support, technical assistance, and short-term and ad-hoc projects (worth US$100 million, see ; also see Söderbaum and Brolin Citation2016). While earlier Swedish regional strategies focussed on security and conflict management, economic growth, and regional trade, there has been increasing emphasis on environmental sustainability, climate change, anti-corruption and research capacity. The most recent strategies feature the priorities of democracy, gender equality and human rights as well as migration (Regeringskansliet Citation2016, 2021).

Swedish representatives strongly emphasise that Sweden does not take an active role in shaping the AU’s policy agenda (Söderbaum, Stapel, and Wennergren Citation2023). Swedish representatives take pride in that they merely respond to the AU’s requests and needs ‘without trying to actively shape [its] policy agenda’ from outside as several other donors are trying to do (Söderbaum and Brolin Citation2016, 54–55).Footnote32 Even if Sweden has defined a clear strategy on the basis of its own foreign aid objectives, Swedish support is stated as demand-driven and it is centred on the AU’s priority areas in accordance with Agenda 2063: peace and security; social, economic and human development; trade integration and industry; shared values (i.e. political affairs); and institutional capacity-building and communications. The Swedish approach thus represents, to a large extent, a form of passive involvement at the policy design stage of the aid policy cycle.

Similarly to the first stage of the policy cycle, Sweden grants the AU considerable discretion also during the implementation stage, not least because Sweden lacks the resources and staff to become closely involved in the day-to-day operations of its aid interventions. According to Swedish officials, implementers and experts should be recruited from within the recipient organisation. This type of indirect involvement is considered to be low-cost yet sustainable, as it contributes to long-term capacity-building, which lies at the heart of Swedish regional strategies (Regeringskansliet Citation2016, 2021).Footnote33 Representatives from Sweden and Sida emphasise that it is paramount to strengthen the capacities of the AU and the AU Commission, for instance through human resource management, procurement procedures, IT facilities, communication procedures as well as core funding to cover salaries in the AU’s peace and security council. To this end, Sweden has been providing stable and reliable amounts of ODA, an approach that representatives consider necessary for the achievement of sustainable outcomes rather than short-term outputs.Footnote34 In other words, Swedish representatives are reluctant to become directly involved in the implementation of aid activities and they seek to pursue a long-term agenda that are believed to be in line with the AU’s own agenda. However, despite this long-term vision and strategy, many Swedish projects only last for two years or less (see ). The practices of short-term and ad hoc aid interventions contradict these long-term aims (and seems to deviate from conventional Swedish aid practice in other contexts). Finally, results are considered important, but the results-based framework is less rigid than the British approach (Söderbaum, Stapel, and Wennergren Citation2023). Taken together, the Swedish approach represents indirect implementation involvement.

Comparison

Although the four donors pursue rather similar overarching goals and principles, they differ sharply with regard to both policy and implementation involvement. The framework guiding the analysis enables us to identify four different approaches towards the AU (see ). While the analytical distinctions serve the purpose to classify the donors in the matrix, the labels have been generated inductively through the empirical analysis. The classification of each donor is based on aggregate trends and does not imply that a particular donor never acts according to any of the other types of involvement.

Table 3. Donor approaches towards the African Union.

The EU takes an active role in developing the overall policy agenda and the direction of recipient RIO, while it is also directly involved in the implementation of aid activities. Its desire for control and the focus on details pertains to the whole project cycle – from big decisions to the smallest task. The EU specifies and predefines how to do things step-by-step throughout the policy cycle. In its interactions with the AU, the EU puts heavy pressure to conform to pre-established ideas, norms and standards, and expects the AU to adjust its policies and strategies accordingly. A similar intrusiveness is seen at the implementation stage, where the EU is directly involved in the day-to-day operations of projects. This is underlined by various types of conditionalities, ear-marked funding and the two aide mémoires where the AU Commission is demanded to strictly follow EU guidelines and standards in project reporting and management. The EU’s intrusive and patronising approach to the AU has been criticised, and numerous interviewees from both Africa and Europe, referred to the EU as a ‘bully’.Footnote35 These findings are consistent with the literature, which characterises the EU ‘as a patronising, potentially dangerous and even imperialist great power’ (Bengtsson and Elgström Citation2012, 104).

The UK has a keen interest in inducing policy change according to its own preferences, but seeks to remain only indirectly involved in the implementation of aid activities. Representatives criticise the political and bureaucratic nature of the AU, which gradually has pushed the UK into less politicised policy fields where it is easier to maintain active policy involvement while at the same time only be loosely and indirectly involved in policy implementation. This type of approach can be understood as an Overseer.

Germany is rather passive regarding policy involvement in the sense that its foreign aid is centred on the goals and preferences of the AU. The German approach is also field-centred and bottom-up so that the AU remains in the driving seat of outlining policies and strategies. At the implementation stage, however, Germany asserts a position of direct involvement, which is rather similar to that of the EU. The GIZ has a very large secretariat in Addis Ababa and its representatives are closely and directly involved in the day-to-day implementation of its regional foreign aid to the AU. Clearly, GIZ has clear-cut and very strict guidelines and requirements when it comes to project implementation, which sets it apart from both the UK and Sweden (but not from the EU). Germany also has a very comprehensive program with seconded experts and technical staff within the AU headquarters and in different policy programmes. The German approach can therefore be described as a Micromanager.

Finally, Swedish representatives are determined that they do not interfere with the AU’s independence and autonomy.Footnote36 Accordingly, Sweden is passive in addressing overall policy change and only indirectly involved in the implementation of aid projects. This approach is showcased by the focus on capacity-building programmes, which are predominantly defined and driven by the recipient. Sweden has minimal involvement in projects and activities at the implementation stage, and provides rather large disbursements related to salaries of AU Commission staff as a way of promoting sustainable capacity-building. In sharp contrast to the massive German and EU staff in Addis Ababa, Sweden has only a small number of officials managing a rather comprehensive aid portfolio. Several Swedish officials refer to their own approach in terms of ‘Good Samaritan’, a label which has been used to characterise the Swedish aid model more broadly (Gibson, Andersson, and Shivakumar Citation2005; Borring Olesen, Pharo, and Paaskesen Citation2013; Herrero and Gregersen Citation2016).

Conclusion

While extant research emphasises that regionalism is driven by actors from ‘within’ the region, this study focuses on the different ways by which donors promote regionalism and RIOs from ‘outside’ through regional foreign aid. With inspiration from previous research on the politics of aid in country settings, we started out the paper by developing a novel framework that accounts for donor involvement at various stages of the aid policy process. The comparative empirical analysis reveals that in spite of that the four donors covered in the study share rather similar general goals, they rely on strikingly different approaches regarding their involvement with the AU. More specifically, the EU’s intrusive involvement during both the policy and implementation phase has earned it a reputation of a Bully. While the UK is active and even controlling during agenda-setting and the policy design phase, it is only indirectly involved during the implementation phase. We therefore refer to the UK as an Overseer. Conversely, while Germany has adopted rather passive stance during the policy design phase, it micro-manages the implementation phase, hence the Micromanager. Finally, the Swedish approach is strongly geared towards ‘helping’ the AU achieve its own agenda without being too involved in either policy design or implementation. As a result, many Swedish officials try to build the image of Sweden as a Samaritan.

Our findings have important implications for the way we analyse and understand regionalism and RIOs in the Global South. First, the study forces us to reject the conventional belief that the EU is the main funder and supporter of RIOs in the developing world in general and in Africa in particular. In fact, as far as regional ODA to the AU is concerned, Germany’s contribution is even larger than that of the EU. Other donors, such as the UK and Sweden, also have sizeable regional ODA portfolios. Second, our findings are consistent with previous research that shows that ‘development cooperation remains a scene for the manifestation of international donor identities’ (Delputte and Söderbaum Citation2012: 54). Third, and closely related to the first two points, our study highlights the diversity among donors, and the fact that donors are by no means ‘all the same’. It follows that future research ought to conduct additional comparisons between the EU and other external actors and donors.

Another implication is that the study clearly shows that donors may exploit their role as donors to shape and even control RIOs from the ‘outside’, albeit in different ways. The magnitude and intrusiveness of large and influential donors raises the question of whether these external actors are just as important for RIOs as many of its regular member-states. Hence, the study forces us to rethink boundaries of ‘inside’/’outside’ and members/non-members as well as who really ‘owns’ and ‘controls’ RIOs that are heavily dependent on foreign funding (Söderbaum, Stapel, and Wennergren Citation2023). This is consistent with characterisations of donors to the AU as ‘outside-insiders’ (Tieku Citation2017) and of France as a ‘quasi-member’ of Francophone RIOs in Africa (Mattheis Citation2022).

In this context it needs to be understood that the key focus of this study—donor approaches and the delivery of foreign aid—must not be confused with the effects of foreign aid on RIO performance or broader developmental outcomes. From this perspective, one relevant avenue for future research is to investigate the development effects of the four donors analysed in this paper. It is, for example, worth exploring whether the Bully has more positive effects on RIO performance and development outcomes than those donors with a more passive orientation, such as the Samaritan. While the Samaritan appears to be normatively superior to a Bully, the question is relevant since Swedish regional foreign aid (including that to the AU) is geared towards ‘activities’ and ‘outputs’ and donor evaluations reveal that it has been very difficult to observe measurable and sustainable impact on development (Sida Citation2013; Söderbaum and Brolin Citation2016). For the same reasons, it is equally relevant to assess the development impact of the top-down approach of the Overseer compared to the field-centred approach of the Micro-manager.

Although we advocate a new research agenda on the role of external actors for the promotion of regionalism from the outside, there are certain limitations regarding the generalisability of the study beyond the case of the AU. The first constraint relates to which external actors are engaged in external promotion of regionalism in Africa. Whereas more than 40 bilateral and multilateral donors provide regional ODA to Africa as a whole, only about 10--15 donors provide the bulk of the funding, and many of them are from Europe. With this said, there is a strong tendency for donors to specialise on some regions and recipients, which means that donor influence may be substantial in specific cases. A second limitation concerns the fact that there is extreme variation in the funding levels across different RIOs in Africa (which is persistent over time). The AU and a few other prominent RIOs (such as SADC and to a lesser extent EAC and ECOWAS) attract most of the funding, whereas many other RIOs receive much less or nothing at all. As we also discuss in another recent article (Stapel, Panke, and Söderbaum Citation2023), the rather disturbing policy implication is that regional ODA does not seem to be allocated on the basis of recipient needs, democratic standards or institutional effectiveness and performance.

Acknowledgments

Previous versions of this article were presented at workshops at the University of Gothenburg, the Annual Conference of the Swedish Network for European Studies in Political Science (SNES) in 2018 and the Swedish Development Research Conference in 2018. We are grateful for valuable comments by Anja Karlsson Franck, Sofie Hellberg, Adrian Hyde-Price, Merran Hulse, Johan Karlsson Schaffer, Frank Mattheis, Mariel Reiss, Kilian Spandler, Ueli Staeger and Jan Vanheukelom. We also thank Robin Alnäs and Sally Wennergren for research assistance.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Sören Stapel

Sören Stapel is Post-Doctoral Researcher at the University of Freiburg. His research interests include global and regional governance, regional development cooperation, norm and policy diffusion, and overlapping regionalism. He recently published Regional Organisations and Democracy, Human Rights, and the Rule of Law: The African Union, Organisation of Americas States, and the Diffusion of Institutions (Palgrave Macmillan, 2022) and Comparing Regional Organisations: Global Dynamics and Regional Particularities (Bristol University Press, 2020, with Diana Panke and Anna Starkmann).

Fredrik Söderbaum

Fredrik Söderbaum is Professor of Peace and Development Research at the School of Global Studies, University of Gothenburg, and Associate Research Fellow at the United Nations University Institute of Comparative Regional Integration Studies (UNU-CRIS), Bruges, Belgium. He is widely published in leading journals on topics such as comparative regionalism, global governance, African politics, development research, and the EU’s external policies. His most recent books include Contestations of the Liberal International Order: A Populist Script of Regional Cooperation (with Kilian Spandler and Agnese Pacciardi, Cambridge University Press, 2021) and Rethinking Regionalism (Palgrave Macmillan, 2016).

Notes

1 We define RIOs as geographically confined international organizations; as institutionalized forms of cooperation between three or more states in more than one narrowly defined policy area where membership criteria relate to geographical considerations (Panke, Stapel, and Starkmann Citation2020: 1). There are 18 multi-purpose RIOs where membership is granted only to states on the African continent.

2 Regional ODA is a distinct category compared to both national (country-based) ODA and multilateral ODA. Regional ODA targets two or more countries within the same region or subregion. It can be provided by countries or multilateral agencies. The funds are often (but not always) channeled through regional recipients and frameworks (such as a RIO, a regional NGO, a regional committee) or through donor-driven mechanisms (Engel and Mattheis Citation2020). Moreover, regional foreign aid needs also to be distinguished from other types of external transfers, such as loans, investments, or philanthropic donations.

3 Interview with AU Commission representative, Addis Ababa, 10 May 2017; interview with EU representative and Swedish representatives, Addis Ababa, 11 May 2017.

4 Interview with AU Commission representative, Addis Ababa, 10 May 2017; interview with civil society representative, Addis Ababa, 9 May 2017.

5 Interview with AU Commission representative, Addis Ababa, 10 May 2017; interview with EU representative, Addis Ababa, 11 May 2017.

6 However, the EU has provided additional, non-ODA funding in the peace and security sector through the African Peace Facility (since 2021 the European Peace Facility), the Instrument for Stability, and the Common Foreign and Security Policy.

7 Interview with civil society representative, Addis Ababa, 9 May 2017.

8 Interview with AU Commission representative, Addis Ababa, 10 May 2017.

9 Interview with EU representative, Addis Ababa, 11 May 2017.

10 Interview with civil society representative, Addis Ababa, 9 May 2017.

11 Interview with EU representative, Addis Ababa, 11 May 2017.

12 Interview with EU representative, Addis Ababa, 11 May 2017.

13 Interview with EU member-state representative, Addis Ababa, 11 May 2017; interview with EU member-state representative, Addis Ababa, 16 May 2017.

14 Interview with DFID representative, Addis Ababa, 11 May 2017.

15 Interview with DFID representative, Addis Ababa, 11 May 2017.

16 Interview with DFID representative, London, 12 December 2017.

17 Interview with DFID representative, Addis Ababa, 11 May 2017.

18 Interview with DFID representative, Addis Ababa, 11 May 2017.

19 Interview with DFID representative, Addis Ababa, 11 May 2017.

20 Interview with DFID representative, Addis Ababa, 11 May 2017; Interview with DFID representative, Pretoria, 4 April 2017.

21 Interview with German officials, Berlin, 7 June 2018.

22 Interview with GIZ representative, Addis Ababa, 19 May 2017.

23 Interview with GIZ representative, Addis Ababa, 19 May 2017.

24 Interview with GIZ representative, Addis Ababa, 12 May 2017; interview with German officials, Berlin, 7 June 2018; interview with GIZ representative, Pretoria, 18 June 2017.

25 Interview with GIZ representative, Pretoria, 18 June 2017

26 Interview with German officials, Berlin, 7 June 2018.

27 Interview with GIZ representative, Addis Ababa, 16 May 2017.

28 Interview with GIZ representative, Pretoria, 18 June 2017

29 Interview with GIZ representative, Addis Ababa, 16 May 2017.

30 Interview with GIZ representative, Addis Ababa, 16 May 2017.

31 Interview with GIZ representative, Addis Ababa, 12 May 2017.

32 Interview with Sida representatives, Addis Ababa, 11 May 2017.

33 Interview with Sida representatives, Addis Ababa, 11 May 2017.

34 Interview with Sida representatives, Addis Ababa, 11 May 2017.

35 Interview with civil society representative, Addis Ababa, 9 May 2017; interview with AU Commission representative, Addis Ababa, 10 May 2017; interview with Sida representatives, Addis Ababa, 11 May 2017; interview with UNECA representative, Addis Ababa, 15 May 2017.

36 Interview with Sida representatives, Addis Ababa, 11 May 2017.

Bibliography

- Alden, C., A. Alao, Z. Chun, and L. Barber (eds.). 2018. China and Africa: Building Peace and Security Cooperation on the Continent. Cham: Springer.

- Alesina, A., and D. Dollar. 2000. “Who Gives Foreign Aid to Whom and Why?” Journal of Economic Growth 5 (1):33–63. doi:10.1023/A:1009874203400.

- Apuuli, K. P. 2018. “The UK and Africa Relations: Construction of the African Union’s Peace and Security Structures.” In Britain and Africa in the Twenty-First Century: Between Ambition and Pragmatism, edited by D. Beswick, J. Fisher, and S. R. Hurt, 54–72. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Auswärtiges Amt. 2011. Germany and Africa: A Strategy Paper by the German Government. Auswärtiges Amt: Berlin.

- Auswärtiges Amt. 2019. Afrikapolitische Leitlinien der Bundesregierung. Auswärtiges Amt: Berlin.

- Bach, D. C. 2016. Regionalism in Africa. Genealogies, Institutions and Trans-State Networks. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Baert, F., T. Scaramagli, and F. Söderbaum (eds.) 2014. Intersecting Interregionalism: Regions, Global Governance and the EU. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Bengtsson, R., and O. Elgström. 2012. “Conflicting Role Conceptions? The European Union in Global Politics.” Foreign Policy Analysis 8 (1):93–108. doi:10.1111/j.1743-8594.2011.00157.x.

- BMZ. 2017. Africa and Europe - A New Partnership for Development, Peace and a Better Future. Cornerstones for a Marshall Plan with Africa. BMZ: Berlin.

- Boiar, A. O. 2014. “Revenue-Generating Schemes for International Unions.” Journal of Economic Integration 29 (3):407–429. doi:10.11130/jei.2014.29.3.407.

- Borring Olesen, T., H. O. Pharo, and K. Paaskesen. 2013. Saints and Sinners: Official Development Aid and Its Dynamics in a Historical and Comparative Perspective. Oslo: Akademika Pub.

- Börzel, T. A. and T. Risse (eds.). 2016. The Oxford Handbook of Comparative Regionalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Brown, S. 2017. “Foreign Aid and National Ownership in Mali and Ghana.” Forum for Development Studies 44 (3):335–356. doi:10.1080/08039410.2017.1344728.

- D’Emidio, F., and T. Wallace. 2019. “The Value for Money Agenda: From a Straitjacket to a Learning Approach.” Development in Practice 29 (6):685–696. doi:10.1080/09614524.2019.1586834.

- Delputte, S., and F. Söderbaum. 2012. “European Aid Coordination in Africa: Is the Commission Calling the Tune?.” In The European Union and Global Development: An ‘Enlightened Superpower’ in the Making?, edited by S. Gänzle, S. Grimm, and D. Makhan, 37–56. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

- DFID. 2012. Operational Plan 2011-2015: DFID Africa Regional Programme. London: DFID.

- DFID. 2017. DFID Africa Regional Department Profile: July 2017. London: DFID.

- Dietrich, S. 2016. “Donor Political Economies and the Pursuit of Aid Effectiveness.” International Organization 70 (1):65–102. doi:10.1017/S0020818315000302.

- Diez, T. and N. Tocci (eds.) 2017. The EU, Promoting Regional Integration, and Conflict Resolution. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

- Ege, J., and M. W. Bauer. 2017. “How Financial Resources Affect the Autonomy of International Public Administrations.” Global Policy 8 (5):75–84. doi:10.1111/1758-5899.12451.

- Eichenauer, V. Z., and B. Reinsberg. 2017. “What Determines Earmarked Funding to International Development Organizations? Evidence from the New Multi-Bi Aid Data.” The Review of International Organizations 12 (2):171–197. doi:10.1007/s11558-017-9267-2.

- Engel, U. 2020. “The Finances of the African Union (AU).” In The Finances of Regional Organisations in the Global South: Follow the Money, edited by U. Engel and F. Mattheis, 19–34. London: Routledge.

- Engel, U. and F. Mattheis. (eds.). 2020. The Finances of Regional Organisations in the Global South: Follow the Money. London: Routledge.

- EU Commission. 2018. Replies of the Commission and the EEAS to the Special Report of the European Court of Auditors "The African Peace and Security Architecture: Need to Refocus EU Support. Brussels: EU Commission.

- European Court of Auditors. 2018. The African Peace and Security Architecture: Need to Refocus EU Support. Special Report No. 20/2018. Luxembourg: European Court of Auditors.

- Gibson, C. C., K. Andersson, and S. Shivakumar. 2005. The Samaritan’s Dilemma: The Political Economy of Development Aid. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Graham, E. R. 2015. “Money and Multilateralism: How Funding Rules Constitute IO Governance.” International Theory 7 (1):162–194. doi:10.1017/S1752971914000414.

- Graham, E. R. 2017. “Follow the Money: How Trends in Financing Are Changing Governance at International Organizations.” Global Policy 8 (S5):15–25. doi:10.1111/1758-5899.12450.

- Haastrup, T. 2013. “EU as Mentor? Promoting Regionalism as External Relations Practice in EU–Africa Relations.” Journal of European Integration 35 (7):785–800. doi:10.1080/07036337.2012.744754.

- Hänggi, H., R. Roloff, and J. Rüland (eds.). 2006. Interregionalism and International Relations. London: Routledge.

- Herrero, A., and C. Gregersen. 2016. Prospects for Supporting Regional Integration Effectively: An Independent Analysis of the European Union’s Approach to the 11th European Development Fund Regional Programming. ECDPM Discussion Paper 192. Maastricht: ECPDM.

- Hoeffler, A., and V. Outram. 2011. “Need, Merit, or Self-Interest—What Determines the Allocation of Aid?” Review of Development Economics 15 (2):237–250. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9361.2011.00605.x.

- Honig, D. 2018. Navigation by Judgment: Why and When Top Down Management of Foreign Aid Doesn’t Work. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Jolliff Scott, B. 2020. “Explaining a New Foreign Aid Recipient: The European Union’s Provision of Aid to Regional Trade Agreements, 1995–2013.” Journal of International Relations and Development 23 (3):701–727. doi:10.1057/s41268-018-0163-z.

- Kagame, P. 2017. The Imperative to Strengthen Our Union. Report on the Proposed Recommendations for the Institutional Reform of the African Union, Decision on the Institutional Reform of the African Union, Assembly/AU/Dec.606 (XXVII). Addis Ababa: African Union.

- Katzenstein, P. J. 2005. A World of Regions. Asia and Europe in the American Imperium. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Kell, F., and A. Vines. 2021. “The Evolution of the Joint Africa-EU Strategy (2007-2020).” In The Routledge Handbook of EU-Africa Relations, edited by T. Haastrup, L. Mah, and N. Duggan, 105–120. London: Routledge.

- Krapohl, S. (ed.). 2017. Regional Integration in the South. External Influence on Economic Cooperation in ASEAN, MERCOSUR and SADC. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

- Lenz, T. 2021. Interorganizational Diffusion in International Relations: Regional Institutions and the Role of the European Union. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Mattheis, F. 2022. “How to Wield Regional Power from Afar: A Conceptual Discussion Illustrated by the Case of France in Central Africa.” International Politics, Online First. doi:10.1057/s41311-021-00347-8.

- Mattli, W. 1999. “Explaining Regional Integration Outcomes.” Journal of European Public Policy 6 (1):1–27. doi:10.1080/135017699343775.

- Obydenkova, A. V., and A. Libman. 2019. Authoritarian Regionalism in the World of International Organizations: Global Perspective and the Eurasian Enigma. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Oksamytna, K., and N. Wilén. 2022. “Adoption, Adaptation or Chance? Inter-Organisational Diffusion of the Protection of Civilians Norm from the UN to the African Union.” Third World Quarterly 43 (10):2357–2374. doi:10.1080/01436597.2022.2102474.

- Panke, D., S. Stapel, and A. Starkmann. 2020. Comparing Regional Organizations: Global Dynamics and Regional Particularities. Bristol: Bristol University Press.

- Patz, R., and K. H. Goetz. 2019. Managing Money and Discord in the UN: Budgeting and Bureaucracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Pfeffer, J., and G. R. Salancik. 1978. The External Control of Organizations: A Resource Dependence Perspective. New York: Harper & Row.

- Regeringskansliet. 2010. Cooperation Strategy for Regional Development Cooperation with Sub-Saharan Africa 2010-2015. Stockholm: Ministry for Foreign Affairs.

- Regeringskansliet. 2016. Strategy for Sweden’s Regional Development Cooperation in Sub-Saharan Africa 2016-2021. Stockholm: Ministry for Foreign Affairs.

- Sida. 2013. Midterm Review. Strategy for Regional Development Cooperation with Sub-Saharan Africa 2010-2015, 5 April 2013, Stockholm: Sida.

- Schneider, C. J., and J. L. Tobin. 2016. “Portfolio Similarity and International Development Aid.” International Studies Quarterly 60 (4):647–664. doi:10.1093/isq/sqw037.

- Söderbaum, F., and T. Brolin. 2016. Support to Regional Cooperation and Integration in Africa—What Works and Why? EBA Report 2016:01. Stockholm: Expert Group for Aid Studies.

- Söderbaum, F. 2016. Rethinking Regionalism. Cheltenham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Söderbaum, F., S. Stapel, and S. Wennergren. 2023. “Something for Everyone”: Ownership as a Moving Target in Swedish and British Regional Foreign Aid to Africa.” Development Policy Review, Online First. doi:10.1111/dpr.12684.

- Stapel, S. 2022. Regional Organizations and Democracy, Human Rights, and the Rule of Law: The African Union, Organization of American States, and the Diffusion of Institutions. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Stapel, S., D. Panke, and F. Söderbaum. 2023. “Regional International Organizations in Africa as Recipients of Foreign Aid: Why Are Some More Attractive to Donors than Others?” Cooperation and Conflict, Online First. doi:10.1177/00108367221147791.

- Swedlund, H. J. 2013. “From Donorship to Ownership? Budget Support and Donor Influence in Rwanda and Tanzania.” Public Administration and Development 33 (5):357–370. doi:10.1002/pad.1665.

- Swedlund, H. J. 2017. The Development Dance: How Donors and Recipients Negotiate the Delivery of Foreign Aid. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Tieku, T. K. 2017. Governing Africa: 3D Analysis of the African Union’s Performance. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Whitfield, L. (ed.). 2009. The Politics of Aid: African Strategies for Dealing with Donors. Oxford: Oxford University Press.