Abstract

Over the past two decades, the Gulf states have emerged as leading humanitarian actors both regionally and globally. This paper charts the evolution of four of the six Gulf states–Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Kuwait, and Qatar–as humanitarian donors and actors. It analyses the evolving humanitarian sectors of the Gulf states, focussing on trends in humanitarian funding, the increasing centralisation of humanitarian governance, and growing capacities in logistics and operations. It then considers the dynamics of politicisation and securitisation of Gulf state humanitarian donors and the potential of and limits to humanitarian coordination and partnership between Gulf and international humanitarian donors. In sum, the study charts the rise and transformation of the Gulf states from merely funding humanitarian efforts to becoming multifaceted humanitarian actors playing diverse roles in the regional and international humanitarian systems.

Introduction

Over the past two decades, the four Gulf states of Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Kuwait, and Qatar have emerged as some of the world’s largest donors of both foreign aid and humanitarian assistance. However, the provision of foreign aid from the Gulf is not a recent phenomenon. Existing research literature has examined the role of the Gulf countries primarily through the lens of aid in relation to foreign policy–which is understandable given the increasing geo-strategic importance of the Gulf in contemporary conflict zones in the Middle East (AlMezaini Citation2012; Kharas Citation2015; Leichtman Citation2017). However, there is a significant gap in research focussing specifically on the humanitarian role of the Gulf states as a regional sub-grouping.

This paper contributes towards this small yet growing research sub-field through a comparative analysis of the humanitarian aid drivers and dynamics of four Gulf states–Saudi Arabia, UAE, Kuwait and Qatar. The paper charts the drivers and dynamics influencing the emergence and long-term evolution of the Gulf states, from limited roles as humanitarian funders to becoming multifaceted humanitarian actors playing a significant and proactive role in regional and global humanitarian systems. By examining the emergence and evolution of the Gulf states as humanitarian actors, this paper helps to clarify and narrow the gap in understanding Gulf donorship, which is an important step towards facilitating collaboration and coordination with other non-traditional and Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s Development Assistance Committee (OECD-DAC) donors.

The paper begins with a brief background on the historical evolution of foreign aid in the Gulf states. Following this, the paper provides an analysis of some key structural features of the Gulf states as donors. The paper then analyses several important trends and dynamics reshaping the context of contemporary humanitarian donorship in the Gulf–the politicisation and securitisation of humanitarianism, institutional adaptations to the changing humanitarian landscape, and the limits to and potential of humanitarian coordination. Finally, the paper concludes with several key findings and reflections on areas for future research.

The paper draws on a multi-method approach that utilises a range of data sources. Aid databases, including those from the United Nations (UN) Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) and the OECD Development Assistance Committee (OECD-DAC), were used to track patterns in humanitarian funding from the Gulf states. In addition, official statistics for Gulf donors were consulted where available. The paper also draws on primary data from interviews in addition to observational methods based on the professional engagement of the authors, who have been involved in humanitarian research, policy and training within the Gulf states in various capacities over many years. Finally, secondary sources, including academic research and quality media reporting, were consulted in a desk review.

Theoretical contribution

The paper contributes to the existing literature on foreign aid by providing a unique analysis of the Gulf states’ humanitarian donorship, which has not been previously researched in a comparative and comprehensive manner. The majority of studies on Gulf donorship tend to analyse the broader issue of foreign aid rather than independently analysing humanitarian donorship (Villanger Citation2007; Barakat and Zyck Citation2010; AlMezaini Citation2012; Kharas Citation2015; Leichtman Citation2017; Li Citation2019). The existing literature primarily assesses the role of foreign aid in the context of each state’s foreign policy (AlMezaini Citation2012; Young Citation2017; Turner Citation2019), and its relationship with various factors, such as oil prices and regional stability (Barakat and Zyck Citation2010; Cotterrell and Harmer Citation2005).

There has been even less research concerned with the comparative trends of Gulf state donorship, and this scant research has largely focussed on single donor countries, such as studies of Saudi Arabia (Al Yahya and Fustier Citation2011), UAE (Gökalp Citation2022), and Kuwait (Elkahlout Citation2020). By considering the Gulf sub-region as a comparative unit of analysis (AlMezaini Citation2021; Schmelter Citation2019), the paper augments the emerging body of literature concerned with humanitarian policy in the context of Gulf donors.

Additionally, the paper moves beyond scholarship that primarily focusses on the funding and politics of Gulf humanitarian donors to consider the broader processes of governance, operations, logistics and coordination that together constitute the Gulf experience with the humanitarian sector. Presently, Gulf state humanitarian aid is often reductively interpreted from two primary perspectives. The first is that Gulf humanitarian donors are often seen by the international humanitarian system as an opportunity to mobilise additional resources from ‘new donors’ in order to meet the funding gap for crisis response globally (Willitts-King and Spencer Citation2021). The second is that Gulf humanitarian donorship is also often analysed as a soft power instrument, in particular with the emergence of Saudi Arabia and the UAE amongst the world’s largest humanitarian donors being dismissed as reputation management tools in the aftermath of their intervention in the war in Yemen.

Whilst this focus of the Western humanitarian actors on the resource mobilisation potential of the Gulf states is understandable, the Gulf donorship experience offers a unique and important case study of the evolution of ‘non-traditional’ humanitarian donors in their own right. To this end, the paper contributes to the emerging comparative knowledge based on the broad category of ‘non-traditional’ donors (Call and De Coning Citation2017; Paczyńska Citation2020), seeking more nuanced, typological conceptualisations of emerging, pluralistic humanitarian practices on the global level that go beyond the binaries of ‘traditional/non-traditional’ donorship. ‘Non-traditional’ donors–including the BRICS countries (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa), Turkey, and the Gulf states–have all been analysed in comparison to the OECD-DAC or ‘traditional’ donors in terms of a combination of factors that shape their modalities of humanitarian and development cooperation (Kragelund Citation2011).

The available research on non-traditional humanitarian donors has included studies of Russia as a humanitarian actor (Brezhneva and Ukhova Citation2013), Turkey as an emerging humanitarian actor (Özerdem Citation2019), and China’s use of humanitarian diplomacy as a soft power strategy (Gong Citation2021). For other states, the ‘non-traditional’ or emerging donor categorisation is less clear cut. For instance, one study explores the question of whether Japan is positioned on the periphery of the international humanitarian system out of strategic choice or necessity (Gómez Citation2021).

Similarly, the Gulf states, with their long tradition of humanitarian funding and very high levels of resources, do not neatly fit the characterisation of ideal-typical ‘non-traditional’ or emerging donors. Thus, this paper seeks to articulate the Gulf donor experience to advance and contribute to the broader literature on foreign aid, offering a more nuanced understanding of an increasingly important ‘non-traditional’ or emerging set of donors in the humanitarian system. This provides a comprehensive and nuanced conceptualisation of the Gulf donor experience, filling a significant gap in the existing research literature.

Emergence of Gulf state donors

Following the discovery and subsequent nationalisation of oil in the 1960s and 1970s, three Gulf states–Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Kuwait–were able to play a minor role in shaping Middle Eastern politics through the supply of aid (AlMezaini Citation2012). During this period, the aftermath of the 1967 Arab–Israeli War served as a catalyst for Gulf aid, with these donors directing more than half of their aid to meet the needs of Palestinian refugees in Egypt, Syria, Jordan, and Lebanon (Barakat and Zyck Citation2010, 13).

The foreign aid provided by these three states was institutionalised through the establishment of sovereign foreign aid funds to provide humanitarian and development assistance. Kuwait was the first to create such a fund in 1961–the Kuwait Fund for Arab Development. From its early days, the Kuwait Fund only offered aid to other Arab countries. However, its operations expanded to include non-Arab countries in the mid-1970s. Subsequently, the UAE created the Abu Dhabi Fund for Development (ADFD) in 1971, and Saudi Arabia founded the Saudi Fund for Development (SFD) in 1974 (Shushan and Marcoux Citation2011). These three funds, along with other semi and ad hoc donor organisations, provide humanitarian and development assistance on behalf of the state (Barakat and Zyck Citation2010, 9). Aside from formal donations, Gulf rulers frequently and proactively donate monies through their charitable foundations or national organisations (Watanabe Citation2016, 171). Unlike the other three states, Qatar preferred to provide foreign assistance through direct financial transfers instead of employing an intermediary government agency (Barakat and Zyck Citation2010, 10). A major change occurred in 2002 with the establishment of the Qatar Fund for Development (QFFD), which was only fully activated in 2012.

Besides sovereign foreign aid funds, Gulf donors have participated and assisted in the establishment of a number of Arab multilateral organisations. The most prominent of these organisations include the Arab Fund for Economic and Social Development (AFESD) founded in 1974 in Kuwait, the Islamic Development Bank (IDB) founded in 1975 in Saudi Arabia, the Arab Bank for Economic Development in Africa (BADEA) based in Khartoum, the Organisation of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) Fund for International Development (OFID) based in Vienna, and the Arab Gulf Program for United Nations Development Organizations (AGFUND) founded in 1980 and based in Riyadh (Shushan and Marcoux Citation2011, 1970–1971).

Gulf state humanitarian donorship: funding, governance and coordination

This section analyses the Gulf states as humanitarian donors across several functional areas: funding, governance, logistics and operations, and coordination and partnerships. It will also consider the overall changing role of Gulf donors, from primarily playing a funding role to becoming proactive humanitarian actors.

Gulf state humanitarian funding

The increased scale of Gulf state assistance is a major trend within the changing global landscape of humanitarian financing over the past few decades (AlMezaini Citation2021). Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Kuwait, and Qatar were amongst the top 10 non-DAC donors from 2000 to 2010 (Billat Citation2015, 6), thus making them important international humanitarian actors. Whilst the Gulf states contributed only 1% of global humanitarian funding in 2000, by 2014, they had collectively contributed 7% (Billat Citation2016). By 2014, Saudi Arabia and the UAE had entered the top 10 and top 20 lists of the most generous humanitarian donors, respectively (Development Initiatives Citation2015). These two Gulf states, in particular, have recorded single years in which they rank as amongst the most generous donors worldwide. As such, this section presents data on the changing patterns of Gulf humanitarian assistance, focussing on the period between 2012 and 2021.

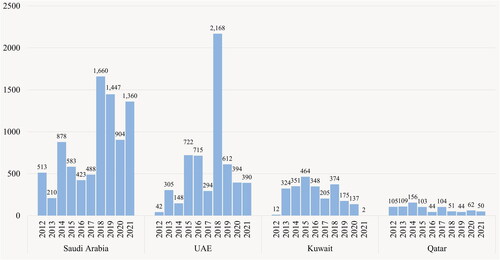

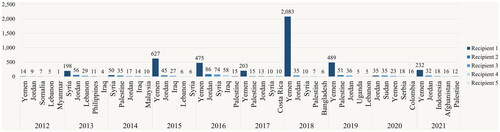

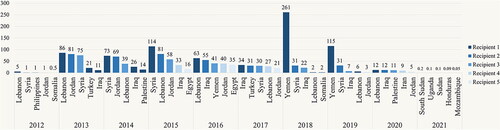

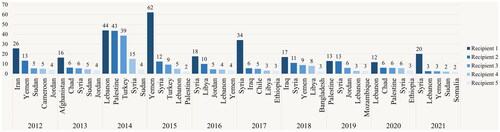

Upon examining the data on assistance provided by the four Gulf states, as presented in , several notable findings emerge. Firstly, it is apparent that of the four, Saudi Arabia is the most consistent large-scale humanitarian donor–having quadrupled its aid from 2017 to 2018. The UAE exhibits a similar pattern of funding, having increased nearly 10-fold in the same period of time and making it the largest annual humanitarian funding figure by any Gulf state on record. However, these patterns of funding show inconsistency amongst the Gulf states. For instance, Kuwaiti funding, in some years, saw drastic changes, with a high of $464 million in 2015 to a low of $3 million in 2021. As for Qatar, whilst its humanitarian assistance levels are the lowest of the four studied donors (), it has by far the most consistent contributions, averaging $83 million per year.

Figure 1. Total humanitarian assistance from four Gulf states, 2012–2021 (USD million). Source: OCHA FTS (Citationn.d.).

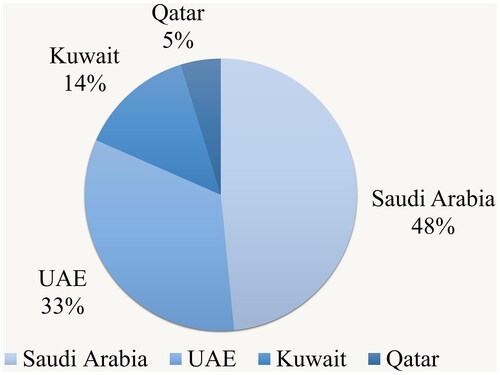

Figure 2. Share of combined Gulf humanitarian assistance by country, 2012–2021. Source: OCHA FTS (Citationn.d.).

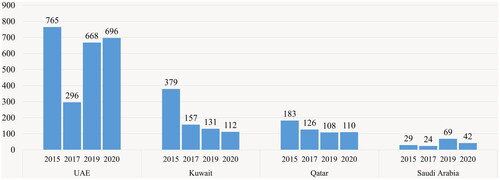

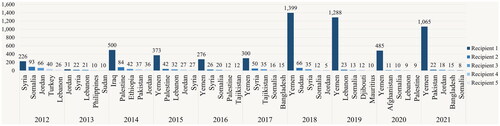

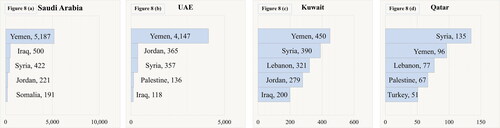

shows humanitarian aid per capita for the selected Gulf states based on official data retrieved from national databases and, whenever required, estimates made by the authors. The UAE consistently ranks first amongst the four states in this context, whilst Saudi Arabia ranks last. This rationalises and contextualises the total expenditures presented in and , where Saudi Arabia’s funding constituted nearly half of all Gulf humanitarian assistance (48%). further break down Gulf assistance by contributor and recipient. The data presented below only includes funding that can be allocated by country.

Figure 3. Total Gulf countries’ humanitarian aid per capita, 2015–2020 (USD million). Sources: OCHA FTS (Citationn.d.); UN DESA (Citation2020); GCC-Stat (Citationn.d.); Saudi General Authority for Statistics (Citationn.d.); Qatar Planning and Statistics Authority (PSA) (Citationn.d.).Footnote1

Figure 4. Saudi Arabia’s top five humanitarian aid recipients, 2012–2021 (USD million). Source: OCHA FTS (Citationn.d.).

Figure 5. UAE’s top five humanitarian aid recipients, 2012–2021 (USD million). Source: OCHA FTS (Citationn.d.).

Figure 6. Kuwait’s top five humanitarian aid recipients, 2012–2021 (USD million). Source: OCHA FTS (Citationn.d.).

Figure 7. Qatar’s top five humanitarian aid recipients, 2012–2021 (USD million). Source: OCHA FTS (Citationn.d.).

There is a very significant variation among the four states in terms of their recipients, which can be seen in . Here, several findings stand out. Firstly, since the start of the Yemen war in 2015, Saudi Arabia and the UAE have provided more humanitarian aid to Yemen than to any other recipient, whilst Kuwait and Qatar’s contributions to Yemen did not show a consistent pattern. Secondly, Saudi Arabia and the UAE tend to concentrate their aid towards a single recipient–Yemen–whilst Kuwait and Qatar showed greater diversity in their disbursement of aid. This is reflected in . Thirdly, all four states exhibit a similar focus on Arab states, making their aid regionally specific rather than a broader commitment to global aid. This does not imply that the four states did not play a global role, but rather that their focus was on a specific region, specifically the periphery of the Gulf. Fourthly, and especially in the case of Saudi Arabia, there is a noticeable shift in funding, in both amount and recipient, when a regional conflict arises. Moreover, the bulk of Gulf aid has been directed towards fragile contexts rather than a consistent funding mechanism akin to traditional development assistance. In the case of the UAE, some funding was directed towards non-fragile contexts, namely Colombia, Costa Rica and Serbia. However, it is not on a large scale and is inconsistent.

Figure 8. Total Gulf countries’ humanitarian aid to their top five recipients, 2012–2021 (USD million). Source: OCHA FTS (Citationn.d.).

The ‘gold standard’ for humanitarian aid donations to multilateral organisations is generally viewed as un-earmarked, consistent and multi-year funding that can enable both flexibility and predictability of humanitarian needs. The shift of the Gulf states from almost entirely bilateral aid towards significantly greater multilateral funding in the 2010s, whilst addressing some shortfalls in the global humanitarian funding system, was associated with ‘extremely large, one-off inputs to [the] UN system’ (EU Citation2016, 1). Whilst this increased the visibility of Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) aid, it also made aid predictability more challenging (EU Citation2016). Furthermore, much of this multilateral aid was earmarked for particular countries, which reduces the flexibility of multilateral assistance (EU Citation2016). For instance, research has shown that Saudi Arabia earmarks the crises that its multilateral aid is channelled to and, as a donor, is highly demanding of recipient organisations in terms of accountability and efficiency in processing donated funds (Binder, Meier, and Steets Citation2010). In contrast to this pattern, Qatar is notable for having provided highly consistent, un-earmarked funding to UN-OCHA over multiple years.

Gulf humanitarian aid reporting

Measuring the true volume of Gulf state humanitarian aid faces several limitations due to practices of aid reporting and transparency, characterised by numerous weaknesses. In this regard, Shushan and Marcoux (Citation2011) identify two major issues: national aid organisations do not fully disclose information on reported aid, and many aid flows go unreported–the latter often occurs outside the mechanisms of national aid organisations and instead through national ministries or in charitable donations by ruling families where the boundaries of the state are indistinct. Whilst this feature is common in Gulf state aid practice, it is not unique to the sub-region. Emerging donors tend to not share all of the information on their aid and assistance through established channels, do not abide by DAC standards of aid provision, and ‘the way that emerging donors define, disburse, and report aid is significantly different from traditional donors’ (Paczyńska Citation2020, 5).

In 2009, bucking the trend amongst non-traditional donors, the UAE began submitting disaggregated aid data to the OECD-DAC, clearly demarcating between humanitarian and development aid, which makes it an outlier (Cochrane Citation2021). Moreover, the UAE was the first non-Western donor to have participant status in the OECD-DAC and its activism and commitment to transparency and reporting have had a wider impact on improving humanitarian standards in the Gulf and wider Arab region (Lestra Citation2017). This shift by the UAE to standardise its humanitarian efforts forms part of a broader move towards reform, aligning itself with global aid norms and best practices.

There is a stark contrast between this high level of transparency and accountability in the humanitarian aid of the UAE and that of Qatar. Whilst Qatar released annual Foreign Aid Reports from 2007 to 2013, there is no single streamlined system for the reporting of Qatari aid. Furthermore, Qatar’s publicised humanitarian donations are often not reported to OCHA’s Financial Tracking Service (FTS). Whilst it is beyond the scope of this paper to provide a forensic assessment of this gap between reported donations and total humanitarian funding, this evidence suggests Qatar is a much larger humanitarian funder than is commonly understood. In 2021 alone, Qatar provided over $50 million in humanitarian aid to Afghanistan, yet FTS data shows no entry for aid to Afghanistan. Similarly, Qatari government sources claim that $2 billion in humanitarian assistance was provided to Syria during 2012–2017 (MOFA Citation2017)–yet a fraction of this total is reported to FTS. As reported by the Government Communications Office (GCO Citationn.d.), ‘from 2012 until June 2019, Qatar provided aid worth $6.75 billion to more than 100 countries around the world’. However, during the same period Qatar reported $716 million to the FTS. This gap between what is declared and what is reported certainly warrants further study to understand this phenomenon.

In sum, whilst the previous section identified broad trends in Gulf humanitarian funding, limitations in reporting and transparency entail that such an exercise does not capture the true picture of Gulf funding. This is in line with the argument that it is probable ‘that the “real” figures of humanitarian aid flows of “new” donors are higher than the ones reported in the FTS’ (Kot-Majewska Citation2015). Uncovering the ‘real’ level of humanitarian funding is necessary to understanding the full role Gulf states play in the international humanitarian system. Building on Billat’s estimate that the share of Gulf state funding of global humanitarian funding increased from 1% in 2000 to 7% in 2014, and in the absence of an update on this figure, we estimate that in 2023 it has increased to more than double the 2014 estimates.

Unquestionably, Gulf aid dipped in immediate response to the COVID-19 pandemic (AlMezaini Citation2021). However, the UAE (74.2%) and Saudi Arabia (86.7%) recorded the largest percentage increase in humanitarian donations of any major donors in 2021–demonstrating the resilience of Gulf donorship in a highly challenging global crisis (Development Initiatives Citation2022).

The trend of an increasing Gulf proportion of international humanitarian aid is likely to continue as the global influence of the Gulf states, particularly Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Qatar, continues to ascend. The consequences of the Russian–Ukrainian war for the energy market gave an opportunity for the Gulf states to further consolidate their grip on the global energy markets, which is evident in the expansion of their oil and gas production (The Economist Citation2022). The Gulf states would also likely use geopolitical shifts in the wake of the war in Ukraine and increased strategic importance of the Gulf in Western energy markets to further increase their standing via a combination of trade, diplomacy, and aid. With Gulf states bolstered by high oil and gas windfalls, coupled with soaring humanitarian needs and a global food security crisis, there is a high likelihood of an increase in Gulf humanitarian aid levels. This is similar to the trend of the 1970s when large foreign aid disbursals were partly a move to offset negative reputational effects that resulted from the role of the Gulf oil producers in the oil price crisis and came in the context of widespread stagflation globally (Young and Yaghi Citation2020).

Humanitarian governance in the Gulf states

Another major trend involves the centralisation and homogenisation within the governance of the humanitarian sector in the Gulf. Whilst this trend is not observed uniformly across the Gulf, it is nonetheless present in all four countries covered in this study. Some of the common features of this trend include increased central regulatory oversight, the establishment of single state-backed humanitarian organisations, and a shrinking space for non-state humanitarian charities to operate internationally. The four Gulf states have established, professionalised and institutionalised their respective humanitarian sectors.

The UAE has led the way, emerging over the past few decades as the fastest reforming Gulf state donor. In so doing, it has adopted a highly centralised, top-down aid governance model, thus following the OECD-DAC and global aid orthodoxy models (Lestra Citation2017). In 2008, the government established the UAE Office for the Coordination of Foreign Aid (OCFA) as an umbrella for UAE-based charities and organisations, largely drawing upon expertise from UN agencies, hiring international staff, and introducing international modalities in its agencies (Ziadah Citation2019b). These aid reforms undertaken by the UAE have made it a trendsetter within the Gulf region, where its humanitarian sectors have increasingly become professionalised and institutionalised in ways that converge with standard global aid norms.

Saudi Arabia, too, has emerged as one of the world’s largest non-DAC humanitarian aid donors and has increasingly adopted a centralised humanitarian governance model. Research published in 2011 characterised Saudi Arabia’s humanitarian sector as complex, weakly institutionalised, and highly fragmented with numerous humanitarian actors (Al Yahya and Fustier Citation2011). Prior to 2011, the humanitarian sector in Saudi Arabia had already undergone some streamlining and narrowing. For instance, the International Islamic Relief Organisation (IIRO)–which is a Saudi organisation that was once the largest Islamic humanitarian non-governmental organisation (NGO) worldwide–saw its activities significantly curtailed in the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks (Benthall Citation2018). However, the decade from 2010 to 2020 saw a major transformation from a fragmented to a centralised humanitarian sector.

In 2015, the King Salman Humanitarian Aid and Relief Center (KSRelief) was established, which was a major development in the humanitarian sector in Saudi Arabia and across the Gulf. Between 2015 and 2022, KSRelief claimed to have provided over $6 billion in humanitarian aid to 90 countries, and since its establishment has been the only body in Saudi Arabia authorised to provide relief abroad. In 2019, Arab News reported an edict from the Saudi government mandating that any international aid from Saudi Arabia must go through KSRelief–a policy that ‘manifest[s] the control of the Saudi state over international aid flows’ and ‘less visibly–reorients the role of religion in Saudi humanitarianism’ (Derbal Citation2022, 114). With this move, Saudi humanitarian aid came to resemble the UAE model in terms of highly top-down and centralised governance controls where humanitarian organisations can operate.

Following its declaration of independence from Britain in 1961, Kuwait established the Kuwait Fund for Arab Economic Development, which marked the first instance in the Gulf states where an institution was established with the purpose of providing aid for developing countries. Whilst the fund was initially only assisting Arab countries, Kuwait later realised the diplomatic importance of expanding it and thus started using it to aid developing countries in general (Turki Citation2014, 427). Although Kuwait’s humanitarian sector was the first to be institutionally developed prior to the other Gulf states, it is considered less centralised as it is ‘more devolved in terms of decision-making and is governed in a semi-democratic polity in which the royal family in addition to government institutions and al-Umma Council drive the decision-making process’ (Elkahlout Citation2020).

In that regard, Kuwait and Qatar retain more diverse humanitarian sectors, although the space in those two countries has also been narrowed in recent years. The humanitarian sector in Kuwait was subjected to greater state oversight in 2014 after the former Minister for Islamic Affairs resigned following accusations by a senior United States (US) official of supporting terrorist groups in Syria (Ramani 2018). More recently, there are reports that the Kuwaiti government is planning to ‘develop its humanitarian structure’ (Elkahlout Citation2020), which could indicate that Kuwait is attempting to institutionalise its aid sector further to, perhaps, follow the more centralised model of the other Gulf states.

Whilst the UAE, Saudi Arabia and Kuwait have long been donors, Qatar is notable for its late emergence as a humanitarian donor, only gaining prominence around 2004 (MOFA Citation2012). Qatar presents an intriguing case of a major non-DAC donor that lagged in institutionalising and bureaucratising its aid sector, relative to both international trends and sub-regional patterns of aid reform in the Gulf. Since its inception, Qatar has preferred a more personalised approach to aid distribution, with donations and grants often declared or pledged by the Emir himself. An example of this was the $400 million grant to Gaza from the former Emir Sheikh Hamad bin Khalifa Al Thani in 2012. Only in the past decade have major reforms been undertaken to operationalise existing aid governance structures and establish modern aid institutions.

For many years, Qatar boasted a thriving and diverse humanitarian sector, comprising charitable organisations and foundations including more than 10 that provided international humanitarian funding and relief. Actors in the Qatari humanitarian sectors engaged in a variety of humanitarian activities globally, including but not limited to education, healthcare and infrastructure (Barakat, Milton, and Elkahlout Citation2019). The Qatari state, however, restricted the humanitarian sector after the 2017 Gulf Crisis, rescinding the permission for two of the largest Qatari NGOs to operate internationally (Barakat, Milton, and Elkahlout Citation2019). This is mainly tied to the accusations of funding ‘terrorism’ made towards Qatar by Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Bahrain. After the resolution of the Gulf Crisis at the al-Ula Summit in January 2021, however, several Qatari NGOs have been given the green light to operate internationally, although at a much smaller scale than before.

Whilst the effects of these centralising reforms have been analysed as having net positive effects for Gulf donors due to increased efficiency (Lestra Citation2017), many individuals in the Gulf lament the loss of a diverse and more open humanitarian landscape.Footnote2 Overall, the centralisation, professionalisation, accountability and other regulatory reforms of the sector have had a homogenising effect, with Gulf humanitarian donors shifting towards global humanitarian norms and practices. Whilst driven by multiple domestic and external factors, these reforms are primarily a response to politicisation and securitisation in the landscape of humanitarian action in the Gulf.

Humanitarian logistics and operations

One major area in the evolution of the Gulf states as humanitarian actors is in the emergence of the Gulf as a physical site for humanitarian logistics and operations. The establishment of the Dubai Humanitarian City (DHC) in 2003 marked a major milestone in humanitarian role of the Gulf states. Later merged to form the International Humanitarian City (IHC), it has grown to be the world’s largest humanitarian hub and free zone, hosting many UN organisations, non-profits and NGOs, and commercial companies. It has become an attractive site for numerous international humanitarian and development organisations to establish their Gulf presence and operations, with eight UN agencies having opened offices there. In addition, in 2018, the IHC launched the Humanitarian Logistics Databank, enabling real-time tracking of relief supplies. Through these developments, Dubai has leveraged its role as a financial, commercial and transit hub to become a major humanitarian logistics centre with a multifaceted role in the humanitarian system. Whilst Dubai is the physical site for many of these humanitarian roles, in particular since the 2008 financial crisis and bail-out of Dubai, the Emirate of Abu Dhabi has been the primary power centre in the UAE (Ulrichsen Citation2016) and continues to play the decisive role in maintaining the strategy of investing in the humanitarian sector.

The emergence of the UAE as a key node in the regional and international humanitarian system can be attributed to two primary strategic rationales. First is the economic rationale, which emphasises the integration of Dubai as a humanitarian logistics hub within the wider approach in which these capacities can be utilised to provide aid or support the commercial activities of the UAE (Ziadah Citation2019a). In this regard, the UAE has been actively integrating its foreign aid policies with investment regulations that boost the prospects of UAE domestic capital groups entering regional markets, particularly in the real estate, agricultural and infrastructural sectors (Ziadah Citation2019b). Most notably, these capital-oriented ambitions have manifested in the expanding network of seaports, free zones and logistical hubs extending beyond the UAE’s borders. For instance, the UAE operates many ports around the world via its state-owned company, DP World. The annual Dubai International Humanitarian Aid and Development (DIHAD) conference is another embodiment of the UAE’s shift, serving as ‘a prime example of commercialised humanitarianism as a platform for businesses and for-profit social enterprises to showcase their goods and services’ (Gökalp Citation2022, 4).

Secondly, the UAE’s investment in developing its humanitarian sector has been interpreted in terms of state branding and forming part of a national strategy for progressing its global reputation as a ‘metropolitan, open-minded, sophisticated, and innovative’ state in order to boost its attractiveness as a regional and global hub for business, investment and tourism (AlMezaini Citation2012, 72). More recently, evidence of the UAE’s humanitarian efforts as part of its state branding has emerged, with ‘humanitarian diplomacy’ forming one of the six pillars of its soft power strategy (Gökalp Citation2020).

The emergence of humanitarian operations capacities in the Gulf is exemplified well by the large-scale and rapid evacuations of Afghan civilians following the fall of Kabul to the Taliban in August 2021. Qatar played a crucial role in the regional and international humanitarian response at multiple levels, including undertaking humanitarian diplomacy between the Taliban and the international community, operating Kabul International Airport, and evacuating over 70,000 Afghan evacuees to Doha (CBS Citation2021). Qatar also mobilised various domestic organisations to provide emergency social services and assistance to evacuees in Doha, including child protection and family reunification. For example, in just one week during August 2021, Qatar helped 62 unaccompanied minors reunite with their families.Footnote3

Other Gulf states also participated in the humanitarian evacuations, with over 20,000 Afghans being evacuated to Emirates Humanitarian City in Abu Dhabi (The National Citation2021) and 5000 evacuated to a military base in Kuwait, a process managed by the US military and other partners (Kochuba Citation2021). One factor that helped to facilitate the evacuation of Afghans to these Gulf capitals was the fact that they all own and operate state-backed, national airlines which they used to transport the evacuees. This also demonstrates a wider point in that the Gulf states utilise their positionality as a trade and transport hub in addition to close geographical proximity to many crisis zones in Asia and Africa to play an increasingly large role in humanitarian logistics and operations.

Humanitarian coordination and partnerships

The emergence of the Gulf as a logistical and operational hub provided an opportunity for greater humanitarian coordination and partnerships. However, despite the increasingly internationalised and centralised nature of their assistance, coordination has remained poor, both within the Gulf and between the Gulf states and the international humanitarian system. Firstly, intra-Gulf coordination has remained weak and largely irrelevant despite the existence of a number of mechanisms established for this purpose. AlMezaini (Citation2021, 3) notes that ‘despite similarities between the Gulf donors in terms of characteristics of humanitarian aid, there is a lack of cooperation and coordination between them’. This challenge was exacerbated by the 2017–2021 Gulf Crisis, which resulted in the complete severance of the limited forms of coordination and communication between Qatari and Saudi humanitarian organisations. However, the resolution of the Gulf Crisis at the al-Ula Summit in January 2021 enabled greater communication between humanitarian actors across the sub-region.

Secondly, humanitarian coordination between Gulf donors and the international humanitarian system is weak in many crisis settings. However, this is not to say that there is a complete lack of coordination within the context of the four Gulf states. Kuwait is often lauded as a positive example of humanitarian coordination in the Gulf (Elkahlout Citation2020). An early example is the role of Kuwait as the base for international civil–military cooperation to provide humanitarian assistance in Iraq during and following the 2003 invasion (Mack Citation2004). In 2012, OCHA hosted a conference in Kuwait that addressed the potential for cooperation between the UN and the humanitarian sectors in the Gulf (Billat Citation2016). Kuwait’s leadership was also evident when it utilised its convening power as a host for various international donor conferences–including a series of humanitarian and reconstruction conferences for Syria between 2013 and 2016 and the Kuwait International Conference for Iraq Reconstruction in 2018 (Fahim Citation2020; Leichtman Citation2017). To that end, Kuwait was amongst the first Gulf states to be recognised for this multifaceted role in the international humanitarian system, with former United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon designating Kuwait as an ‘international humanitarian center’ in 2014 and the late Emir Sabah al Jaber as a ‘humanitarian leader’ (Leichtman Citation2017, 1 and 2).

It is evident that the Gulf states have recently become more proactive donors, playing a more multifaceted role in the regional and global humanitarian systems. For instance, Saudi Arabia increased its participation in the international humanitarian system, with KSRelief chairing the OCHA Donor Support Group (ODSG) in 2022–2023 as well as participating in the Advisory Group of the Central Emergency Relief Fund (CERF) between 2016 and 2019 (Hamid Citation2022). Furthermore, the UAE has been a member of the OCHA Donor Support Group since 2006, whilst Qatar has been consistent in its support for OCHA with which it has entered into many humanitarian partnerships.

Beyond providing humanitarian aid, KSRelief also hosts pledging events and conferences, such as the biannual Riyadh International Humanitarian Forum, which aims to ‘promote dialogue on legislative, informational, and logistical mechanisms for delivering humanitarian aid’ (KSRelief Citationn.d.). The forum, which costs over $4 million to host, is one of the largest humanitarian conferences globally and attracts participation from many humanitarian leaders, donors, practitioners, researchers and others.

Qatar has also progressively positioned itself as a pivotal regional and global hub for humanitarian coordination, negotiation and diplomacy. At times, it drew controversy from its hosting of the political offices of the Taliban and Hamas in Doha when almost no other states globally would have done so. Hosting these offices and other political movements has positioned Doha as an important site for humanitarian negotiations and diplomacy, with many diplomatic engagements taking place there. For instance, it has hosted secret negotiations over humanitarian access in the Gaza Strip and hosted the US–Taliban talks, culminating in the signing of the Doha Agreement in February 2020. Whilst Qatar has low long-term UN presence in-country compared to the UAE, in 2022 Qatar pledged $500 million as part of an agreement to fund the UN House in Doha, which was established in March 2023, enabling the establishment of multiple new UN offices in the country. This deepened Doha’s position as a diplomatic hub and extends the opportunities for Qatar to play a role in regional and global coordination and policy-setting in humanitarian, development and other spheres.

Despite these efforts towards improved coordination, obstacles persist that hinder the further enhancement of coordination between Gulf donors and the global humanitarian system. Firstly, the gap between the self-perception of OECD-DAC donors as representing the gold standard of humanitarian donorship and the divergent, ‘non-traditional’ practices of the Gulf states has long been cited as an obstacle to international coordination. A study of non-traditional donors found that Western donors found it challenging to engage with Saudi Arabia as they were ‘unsure about how to position themselves towards what they see as a very different approach to humanitarianism’, particularly in terms of aid reporting and the definitions of humanitarian aid (Binder, Meier, and Steets Citation2010, 19).

Secondly, the perceived loss of neutrality constrains the role of the Gulf states in coordination and cooperation with various stakeholders engaged in global humanitarian response. This is rooted in the highly interventionist role in the region undertaken by Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Qatar since the outbreak of the Arab Spring and the war in Yemen. A clear expression of the tension between humanitarian principles and state interests in nexus programming notes that:

In protracted crises, the discrepancies between, on the one hand, humanitarian principles, international human rights law, [and] international humanitarian law, and on the other hand, the diverging political objectives of State and non-state actors as well as other international stakeholders, generate tensions that make a coordinated and comprehensive response from the HDPN [Humanitarian-Development-Peace Nexus] actors difficult at best. (Perret Citation2019, 1)

Politicisation and securitisation from 9/11 to the Gulf Crisis

The emergence and evolution of the Gulf states as humanitarian donors have been fundamentally shaped by the shifting geo-political context of the past few decades. As noted earlier, the Arab–Israeli wars in the 1960s and 1970s were important for the emergence of Gulf humanitarian aid institutions. Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait in 1990 and the First Gulf War in 1991 also posed major geo-political crises for the Gulf sub-region, with severe consequences for the humanitarian sector where aid was heavily disrupted in those years (Cotterrell and Harmer Citation2005). In the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks in 2001, Gulf aid came under intense scrutiny from the international community, due to accusations of supporting terrorism. As a result, Gulf donors increased their efforts to raise their aid profile (Momani and Ennis Citation2012, 620). All this necessitates discussion of the politicisation and securitisation of aid, which has brought increased scrutiny of Gulf aid, the co-optation of humanitarian actors in counter-terrorism and security efforts, and obstacles to funding, coordination and partnerships (Pantuliano, Mackintosh and Elhawary Citation2011; Lacey and Benthall Citation2014).

Over the past two decades, foreign aid from the Gulf states, particularly aid directed towards Arab states, has attracted significant attention. Many international observers view the rise of affluent Gulf states as major aid donors with suspicion, identifying them as ‘financial backers’ of governments, politicians and armed movements often deemed to function as proxies. This suspicion grew with an emerging and sizable literature that tracks Gulf aid directed towards Arab Spring-affected states–whether to governments or the various opposition factions. These issues both led to and compounded the 2017–2021 Gulf Crisis, where mutual public accusations of terrorism financing were common, and stand as an example of the politicisation of humanitarian action in the Gulf.

There is indeed a pronounced tendency amongst Gulf donors to provide aid to favoured parties, allies and groups, significantly influencing political and conflict dynamics. For instance, Saudi and Emirati delivery of humanitarian aid to Yemen carried political considerations, mainly in the form of providing support to the internationally recognised Yemeni government. Furthermore, there is evidence that warring factions in Yemen had siphoned off food aid to reward their supporters or sold aid to acquire hard currency whilst obstructing aid distribution to civilians perceived to oppose them (Greig Citation2023). The deep politicisation of humanitarian aid in Yemen has itself come to be viewed as one of the primary macro-level drivers of conflict (Elnakib et al. Citation2021).

These dynamics of aid politicisation and securitisation in the Gulf are the primary drivers of several key trends within the sub-region’s changing humanitarian landscape. Firstly, as analysed in the previous sub-section, many pressures towards the centralisation of humanitarian governance and conformity with global aid norms in the Gulf donors are a response to the highly securitised and politicised environment. Secondly, the increasingly securitised aid environment has led to barriers to humanitarian operations in the Gulf and the MENA region, in particular bank de-risking and other financial regulations that have been implemented both by states within the Gulf and internationally. Whilst bank de-risking is intended as a counter-terrorism measure to prevent the flow of funds to proscribed terrorist groups and organisations, it produces a set of policy frameworks that have made financial transfers much more challenging and expensive. For instance, government restrictions on the external financial transactions of humanitarian actors working inside Saudi Arabia paralysed local and international NGOs from mobilising and transferring funding to local humanitarian partner organisations abroad (Mackintosh and Duplat Citation2013). Thirdly, as seen in a previous section, politicisation and securitisation have also shaped the potential for humanitarian coordination and partnerships–with concerns of Western donors regarding engagement with the Gulf serving as one barrier to greater coordination.

Lastly, the pressures of politicisation have catalysed some forms of increased transparency and accountability in Gulf humanitarian aid. There is some divergence between Gulf donors in terms of transparency, with Saudi Arabia viewed as the least transparent and Kuwait offering ‘perhaps the most long-standing transparent aid framework in the Gulf Arab states’ (Young Citation2017, 49). Yet the intense politicisation of Gulf aid and the subsequent increased international attention to the money flows of Gulf humanitarian actors created incentives for donors to improve transparency. This dynamic was most pronounced for Qatar in the context of the accusations of terrorist financing made by the UAE and Saudi Arabia. The Gulf Crisis placed immense pressure on Qatar’s humanitarian sector to prove that its state and non-state entities adhere to international law and do not finance proscribed terrorist individuals or organisations.

Conclusion

The aim of this paper has been to provide a more comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the evolution of the humanitarian donorship of the Gulf states, including the broader processes and practices involved. In doing, this paper contributes descriptively by providing a detailed account of the Gulf states’ transition from charitable funders to multifaceted humanitarian actors. Conceptually, it illuminates the unique characteristics and challenges facing the Gulf states as ‘non-traditional’ donors, thereby enriching the broader discourse on foreign aid. Improved understanding of the Gulf states as donors could facilitate improved regional and international coordination, thereby fostering more effective humanitarian action.

The paper began by presenting the theoretical contribution of the study, encompassing comparative analyses of Gulf humanitarian actors, a broader focus on humanitarian governance, logistics and coordination, and a theorisation of the Gulf states as ‘non-traditional’ donors–rather than a reductive focus on funding and politics as an approach to understanding the Gulf donor experience. The paper subsequently analysed trends in Gulf humanitarian donorship in the past decade and acknowledged some limitations to standard methodological approaches, which tend to underestimate the scale of Gulf humanitarian financing. The paper then delved into the trends towards centralisation and homogenisation of Gulf humanitarian sector governance, the expansion of the capacities of Gulf states in humanitarian logistics and operations, and the barriers and opportunities faced in humanitarian coordination and partnerships both within the Gulf and between Gulf and OECD-DAC donors. Finally, the issue of the politicisation and securitisation of Gulf humanitarian assistance was considered as a cross-cutting dynamic that has a major impact on the various trends analysed in the paper.

A central conclusion drawn is that over the past few decades, the role of the Gulf states has evolved from being mere humanitarian funders to emerging as humanitarian actors with multifaceted roles on both regional and global stages. Whilst it is often noted that the Gulf states are not ‘new donors’ due to their long-standing history of distributary largesse, these donors have taken on novel roles over the past decade or so, including in global humanitarian coordination, aid logistics and humanitarian diplomacy. This expansion in their humanitarian roles forms part of the long-term process by which Gulf donors have for years been ‘taking steps to avoid being seen as an “ATM” by their beneficiaries’ (Sons Citation2022). This perception had taken root with Kuwait’s responses to humanitarian and political issues in the region, characterised as ‘dinar diplomacy’ (Assiri 1991, 24–25) and Qatar’s role in conflict mediation, labelled as ‘checkbook diplomacy’ (Rabi Citation2009, 457).

As a result, this evolution has come to produce a unique Gulf donorship experience that necessitates analyses and studies in its own right. This Gulf experience, thus, provides a fresh conceptual lens through which to elucidate and unpack the complexities of foreign aid and humanitarian assistance, representing a distinct form of ‘non-traditional’ donorship. The role played by Gulf states in the humanitarian system will undoubtedly continue to evolve in line with an ever-changing and fluid regional and global context, and this provides a compelling rationale for further studies and research to build on the emerging comparative research agenda on Gulf humanitarianism that this paper contributes towards.

Acknowledgements

Open access funding provided by the Qatar National Library. The authors acknowledge the research assistance provided by Irina Andriiuc, Mohammad Alhamawi and Shatha al-Banna.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Ghassan Elkahlout

Ghassan Elkahlout, PhD, is Associate Professor at the Doha Institute for Graduate Studies where he serves as Head of the MA Programme in Conflict Management and Humanitarian Action. He is Director of the Center for Conflict and Humanitarian Studies, based within the Arab Center for Research and Policy Studies.

Sansom Milton

Sansom Milton, PhD, is Senior Research Fellow at the Center for Conflict and Humanitarian Studies, based within the Arab Center for Research and Policy Studies. He is also Adjunct Assistant Professor at the Doha Institute for Graduate Studies.

Notes

1 The calculations are conducted excluding the number of immigrants in the country for the selected year based on the population mid-year estimated values.

2 Authors’ observations and interviews.

3 Observations and on-site interviews at the evacuation centres.

References

- Al Yahya, K., and N. Fustier. 2011. “Saudi Arabia as a Humanitarian Donor: High Potential, Little Institutionalization.” Global Public Policy Institute. Paper No. 14, 1–35.

- AlMezaini, K. 2012. The UAE and Foreign Policy: Foreign Aid, Identities and Interest. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

- AlMezaini, K. 2021. Humanitarian Foreign Aid of Gulf States: Background and Orientations. Policy Report Number 20. Bonn: Konrad Adenauer Stiftung.

- Barakat, S., and S. Zyck. 2010. Gulf State Assistance to Conflict-Affected Environments. Kuwait Programme on Development, Governance and Globalisation in the Gulf States. London: London School of Economics and Political Science.

- Barakat, S., S. Milton, and G. Elkahlout. 2019. “The Impact of the Gulf Crisis on Qatar’s Humanitarian Sector.” Disasters 44 (1):63–84.

- Benthall, J. 2018. “The Rise and Decline of Saudi Overseas Humanitarian Charities.” CIRS Occasional Paper Number 20.

- Billat, C. 2015. “The Funding of Humanitarian Action by non-Western Donors: The Sustainability of Gulf States’ Contribution.” Master’s thesis, University of Geneva.

- Billat, C. 2016. “The Funding of Humanitarian Action by the Gulf States: A Longterm Commitment.” Humanitarian Aid on the Move. Urgence Rehabilitation Developpement.

- Binder, A., C. Meier, and J. Steets. 2010. “Humanitarian Assistance: Truly Universal? A Mapping Study of Non-Western Donors.” GPPi Research Paper No. 12.

- Brezhneva, A., and D. Ukhova. 2013. Russia as a Humanitarian Aid Donor. Oxford: Oxfam.

- Call, Charles, and Cedric De Coning, eds. 2017. “Conclusion: Are Rising Powers Breaking the Peacebuilding Mold?.” In Rising Powers and Peacebuilding: Breaking the Mold?, 243–272. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- CBS. 2021. “Qatar Helps Tens of Thousands of Afghans Flee the Taliban, CBS News.” CBS Interactive Inc. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/qatar-helping-afghans-flee-taliban/.

- Cochrane, L. 2021. “The United Arab Emirates as a Global Donor: What a Decade of Foreign Aid Data Transparency Reveals.” Development Studies Research 8 (1):49–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/21665095.2021.1883453

- Cotterrell, L., and A. Harmer. 2005. “Aid Donorship in the Gulf States.” HPG Background Paper. Humanitarian Policy Group: Overseas Development Institute.

- Derbal, N. 2022. “Humanitarian and Relief Organizations in Global Saudi Da’wa?” In Wahhabism and the World: Understanding Saudi Arabia’s Global Influence on Islam, edited by Peter G. Mandaville, 114–132. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Development Initiatives. 2015. Global Humanitarian Assistance Report 2015. Bristol: Development Initiatives.

- Development Initiatives. 2022. Global Humanitarian Assistance Report 2022. Bristol: Development Initiatives.

- Elkahlout, G. 2020. “‘Hearts and Minds’: Examining the Kuwaiti Humanitarian Model as an Emerging Arab Donor.” Asian Journal of Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies 14 (1):141–157.

- Elnakib, S., S. Elaraby, F. Othman, H. BaSaleem, N. A. Abdulghani AlShawafi, I. A. Saleh Al-Gawfi, F. Shafique, E. Al-Kubati, N. Rafique, and H. Tappis. 2021. “Providing Care under Extreme Adversity: The Impact of the Yemen Conflict on the Personal and Professional Lives of Health Workers.” Social Science & Medicine (1982) 272:113751. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.113751

- EU. 2016. Humanitarian Policy of the Gulf States. Strasbourg: European Parliament.

- European Commission. 2022. Questions and Answers on the Joint Communication on a Strategic Partnership with the Gulf. Brussels: European Commission, May 18. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/QANDA_22_3166

- Fahim, K. 2020. Kuwait and Qatar: Big Donors, Different Approaches. Washington DC: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, June 9. https://carnegieendowment.org/2020/06/09/kuwait-and-qatar-big-donors-different-approaches-pub-82005

- GCC-Stat. n.d. “Official Website.” GCC Statistical Center. Accessed January 2023. https://gccstat.org/en/.

- GCO. n.d. “Foreign Policy: In Focus.” Government Communications Office. Accessed 26 February 2023. https://www.gco.gov.qa/en/focus/foreign-policy-en/

- Gökalp, D. 2020. “The UAE’s Humanitarian Diplomacy: Claiming State Sovereignty, Regional Leverage and International Recognition.” CMI Working Paper. Chr. Michelsen Institute.

- Gökalp, D. 2022. “Recent Trends in the International Humanitarian Regime and the Rise of the United Arab Emirates on the World Humanitarian Stage.” NCHS Paper 04. Norwegian Centre for Humanitarian Studies.

- Gómez, O. A. 2021. “Japan and the International Humanitarian System: In the Periphery by Design, Principle or Strategy?” Asian Journal of Comparative Politics 6 (4):315–329. https://doi.org/10.1177/20578911211058141

- Gong, L. 2021. “Humanitarian Diplomacy as an Instrument for China’s Image-Building.” Asian Journal of Comparative Politics 6 (3):238–252. https://doi.org/10.1177/20578911211019257

- Greig, M. J. 2023. “Helping without Hurting: Ameliorating the Negative Effects of Humanitarian Assistance on Civil Wars through Mediation.” In International Conflict and Conflict Management, edited by Andrew P. Owsiak, J. Michael Greig, Paul F. Diehl, 79–106. Routledge: Abingdon. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003380832-4

- Hamid, M. 2022. Why the World Needs Partnership with Saudi Arabia: Saudi Arabia’s Global Humanitarian and Development Aid. Riyadh: King Faisal Center for Research and Islamic Studies.

- Kharas, H. 2015. “Trends and Issues in Qatari Foreign Aid.” Silatech Working Paper, 15–11.

- Kochuba, S. 2021. “A Global Response: Mission Kuwait.” State Magazine.

- Kot-Majewska, K. 2015. “Role of Non-Traditional Donors in Humanitarian Action: How Much Can They Achieve?” In The Humanitarian Challenge, edited by Pat Gibbons and Hans-Joachim Heintze, 121–134. Cham: Springer.

- Kragelund, P. 2011. “Back to Basics? The Rejuvenation of Non-Traditional Donors’ Development Cooperation with Africa.” Development and Change 42 (2):585–607. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7660.2011.01695.x

- KSRelief. n.d. “The Riyadh International Humanitarian Forum.” KSRelief website. https://rihf.ksrelief.org/Home/index#about

- Lacey, Robert, and Jonathan Benthall, eds. 2014. Gulf Charities and Islamic Philanthropy in the “Age of Terror” and Beyond. Berlin: Gerlach Press.

- Leichtman, M. 2017. Kuwaiti Humanitarianism: The History and Expansion of Kuwait’s Foreign Assistance Policies. Washington DC: Stimson Center.

- Lestra, M. 2017. “The More It’s Centralized, the More It’s Divided: A Historical-Institutionalist Reading of Qatar’s Foreign Aid Landscape.” Oxford Middle East Review 1 (1):67–89. https://hdl.handle.net/1814/49344.

- Li, Y. 2019. “Saudi Arabia’s Economic Diplomacy through Foreign Aid: Dynamics, Objectives and Mode.” Asian Journal of Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies 13 (1):110–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/25765949.2019.1586367

- Mack, A. 2004. “The Humanitarian Operations Centre, Kuwait: Operation Iraqi Freedom, 2003.” International Peacekeeping 11 (4):683–696. https://doi.org/10.1080/1353331042000248722

- Mackintosh, K., and P. Duplat. 2013. Study of the Impact of Donor Counter‑Terrorism Measures on Principled Humanitarian Action. Oslo: Independent Study Commissioned by the United Nations, the Norwegian Refugee Council or the Study’s Advisory Group.

- MOFA. 2012. Qatar Foreign Aid Report, 2011–2012. Qatari Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

- MOFA. 2017. Foreign Ministry Secretary-General: Qatar Is Proud of Its Humanitarian Efforts. Ministry of Foreign Affairs Qatar. https://mofa.gov.qa/en/all-mofa-news/details/2017/06/14/foreign-ministry-secretary-general-qatar-is-proud-of-its-humanitarian-efforts.

- Momani, B., and C. A. Ennis. 2012. “Between Caution and Controversy: Lessons from the Gulf Arab States as (Re-)Emerging Donors.” Cambridge Review of International Affairs 25 (4):605–627. https://doi.org/10.1080/09557571.2012.734786

- OCHA FTS. n.d. “Official Website.” United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs Financial Tracking Service. Accessed January 2023. https://fts.unocha.org/.

- Özerdem, A. 2019. “Turkey as an Emerging Global Humanitarian and Peacebuilding Actor.” In The Routledge Handbook of Turkish Politics, edited by Alpaslan Özerdem and Matthew Whiting, 470–480. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Paczyńska, Agnieszka, ed. 2020. The New Politics of Aid: Emerging Donors and Conflict-Affected States. Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

- Pantuliano, S., K. Mackintosh, and S. Elhawary. 2011. “Counter-Terrorism and Humanitarian Action Tensions, Impact and Ways Forward.” HPG Policy Brief 43. Humanitarian Policy Group: Overseas Development Institute.

- Perret. 2019. Operationalizing the Humanitarian–Development–Peace Nexus: Lessons Learned from Colombia, Mali, Nigeria, Somalia and Turkey. Geneva: IOM.

- Planning and Statistics Authority. n.d. “Qatar Monthly Statistics.” Qatar Planning and Statistics Authority. Accessed January 2023. https://www.psa.gov.qa/en/Pages/default.aspx.

- Rabi, U. 2009. “Qatar’s Relations with Israel: Challenging Arab and Gulf Norms.” The Middle East Journal 63 (3):443–459. https://doi.org/10.3751/63.3.15

- Saudi General Authority for Statistics. n.d. “Official Website.” Saudi General Authority for Statistics. Accessed January 2023. https://www.stats.gov.sa/en.

- Schmelter, S. 2019. “Gulf States’ Humanitarian Assistance for Syrian Refugees in Lebanon.” Civil Society Knowledge Centre 1 (1). Beirut. https://doi.org/10.28943/CSKC.001.70000

- Shushan, D., and C. Marcoux. 2011. “The Rise (and Decline?) of Arab Aid: Generosity and Allocation in the Oil Era.” World Development 39 (11):1969–1980. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2011.07.025

- Sons, S. 2022. “Why Gulf Aid Donors Are Moving to End ‘ATM’ Perceptions.” Amwaj Media, March 15. https://amwaj.media/article/humanitarian-aid-gcc-saudi-arabia-uae.

- The Economist. 2022. “An Energy Crisis and Geopolitics Are Creating a New-Look Gulf.” The Economist. https://www.economist.com/leaders/2022/09/22/an-energy-crisis-and-geopolitics-are-creating-a-new-look-gulf.

- The National. 2021. “UAE assists evacuation of more than 20,000 refugees as they flee Afghanistan, The National.” The National. https://www.thenationalnews.com/uae/2021/08/24/uae-assists-evacuation-of-more-than-20000-refugees-as-they-flee-afghanistan/.

- Turki, B. 2014. “The Kuwait Fund for Arab Economic Development and Its Activities in African Countries, 1961–2010.” The Middle East Journal 68 (3):421–435. https://doi.org/10.3751/68.3.15

- Turner, M. 2019. “Aid Intervention’ in the Occupied Palestinian Territory: Do Gulf Arab Donors Act Differently from Western Donors?” Conflict, Security & Development 19 (3):283–288. https://doi.org/10.1080/14678802.2019.1608024

- Ulrichsen, K. C. 2016. The United Arab Emirates: Power, Politics and Policy-Making. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

- UN DESA. 2020. World Social Report 2020. New York: United Nations.

- Villanger, E. 2007. “Arab Foreign Aid: Disbursement Patterns, Aid Policies and Motives.” Forum for Development Studies 34 (2):223–256. https://doi.org/10.1080/08039410.2007.9666378

- Watanabe, L. 2016. “Gulf States’ Engagement in North Africa: The Role of Foreign Aid.” In The Small Gulf States: Foreign and Security Policies before and after the Arab Spring, edited by Khalid Almezaini and Jean-Marc Rickli, 168–182. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315619576

- Willitts-King, B., and A. Spencer. 2021. Reducing the Humanitarian Financing Gap: Review of Progress since the Report of the High-Level Panel on Humanitarian Financing. London: Humanitarian Policy Group: Overseas Development Institute.

- Young, K. E. 2017. “A New Politics of GCC Economic Statecraft: The Case of UAE Aid and Financial Intervention in Egypt.” Journal of Arabian Studies 7 (1):113–136. https://doi.org/10.1080/21534764.2017.1316051

- Young, K., and M. Yaghi. 2020. Workshop 4 GRM: Foreign Aid and the Gulf States. Jeddah: Gulf Research Center Cambridge (GRC Cambridge).

- Ziadah, R. 2019a. “Circulating Power: Humanitarian Logistics, Militarism, and the United Arab Emirates.” Antipode 51 (5):1684–1702. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12547

- Ziadah, R. 2019b. “The Importance of the Saudi-UAE Alliance: Notes on Military Intervention, Aid and Investment.” Conflict, Security & Development 19 (3):295–300. https://doi.org/10.1080/14678802.2019.1608026