Abstract

Despite the increased application of settler colonial theory to analyse settler colonial contexts, critical scholars have highlighted its inadequacies – primarily, that it has marginalised Indigenous knowledge and agency. Palestinian scholars have questioned the paradigm’s ability to fully capture the particularities of the Israel–Palestine context. This paper seeks to contribute to these critiques by exploring Palestinian youth’s interpretations of settler colonialism in the West Bank. It draws on qualitative research that explored Palestinian youth’s views on and experiences of human rights. This article suggests that Indigenous analyses of settler colonialism seem more relevant to Palestinian youth than the settler colonial analytic. These, along with consideration of the interplay between neoliberalism and colonisation, may better assist them to understand and articulate settler colonialism and strategise against it.

Introduction

The settler colonial paradigm was consolidated following Wolfe’s (Citation1999) seminal work on settler colonialism and the establishment of the Settler Colonial Studies journal in 2011. Despite the increased application of the analytic to understand different settler colonial contexts, First Nations scholars have underscored some of the inadequacies of the theoretical framework. The paradigm’s failure to foreground Indigenous voices, agency and acts of resistance (Snelgrove, Dhamoon, and Corntassel Citation2014) has been identified as its primary flaw.

This interpretative framework has been applied not only to analyse and compare New World white settler contexts but increasingly to the Palestinian context (see Amoruso et al. Citation2019; Salamanca et al. Citation2012; Svirsky Citation2014; Veracini Citation2015). However, concerns have been raised by some Palestinian scholars about the application of ‘borrowed metaphors’ such as the settler colonialism paradigm (and apartheid) to Palestine since it can fail to fully capture the situation on the ground (Abu-Lughod Citation2020; Barakat Citation2018; Rifkin Citation2017). This paper aims to contribute to these critiques by examining Palestinian youth’s interpretations of settler colonialism and how it plays out in their everyday lives in the occupied West Bank. It explores the potential and limitations of the analytic when it comes to assisting Palestinian youth in their struggle against settler colonialism.

As Palestinian scholar Barakat (Citation2018) contends, whether intentionally or not, Palestinian voices are at risk of being eclipsed within the field. I argue that the views of Palestinian youth are also largely missing within these scholarly debates. There are various reasons why youth’s voices, agency and acts of resistance in particular should be included within the settler colonial literature. Firstly, Palestinian young people are often disproportionately impacted by settler colonial violence. For instance, in 2021 alone, 78 Palestinian children living in the West Bank and Gaza were killed by live ammunition, airstrikes and tank-fired shells (Defense for Children International (DCI) Palestine Citation2021). As Shalhoub-Kevorkian (Citation2015a, 224) notes, youth are often the targets of settler colonial violence because they are perceived as a ‘demographic threat’ to the settler population’s present and future control over land. Secondly, within the Palestinian community, resistance against the occupation is often framed along the lines of various generations (Squires 2015). These generations are described in terms of the historical and political events they encountered as part of this broader ongoing struggle in which youth have played and continue to play a central role (Darweish and Rigby Citation2015). Furthermore, as I have argued elsewhere, it is often assumed that children, especially those living in ‘Third World’ contexts, do not have much to contribute epistemologically (Jiménez Citation2021) and in research these children often remain only empirical examples (Balagopalan Citation2019). Therefore, an overarching aim of this paper is to redress the lack of Indigenous youth views and experiences within the field as they may have contributions to make that are missing in adults’ accounts.

This paper argues that Indigenous readings of settler colonialism along with Clarno’s (Citation2018) framework of ‘neoliberal colonisation’ seem more relevant to Palestinian youth and more applicable the West Bank context than the settler colonial analytic. This is because the analytic inadequately captures the significance of land and the bonds that Palestinian youth in this study (as with other dispossessed peoples) have with it. The paradigm also unhelpfully suggests that the elimination of the native is unavoidable, whereas youth in this study largely anticipated that their liberation is inevitable. The analytic also fails to recognise the intersection of neoliberalism and colonialism, which was identified by youth in this study. The paradigm’s binaries around ‘settler’ and ‘native’ do not align with Palestinian youth’s observations of when natives become collaborators with the settler. Therefore, I propose that Clarno’s (Citation2018) framework, which combines settler colonialism and neoliberal capitalism, can also assist Palestinian youth – especially those from non-elite backgrounds – to make sense of the intersecting inequalities that they experience. However, this is not to suggest that there needs to be a complete departure from settler colonial studies, since aspects of the paradigm can be useful – such as when it comes to de-normalising settler colonial violence and contesting how Palestinians have come to be (mis)represented within Palestine–Israel relations. Rather, the analytic needs to undergo renewal by giving way to epistemic diversity.

This paper is informed by a qualitative study that explored how Palestinian youth understand and deploy human rights and how this is shaped by their human rights education (HRE hereafter) at their respective schools versus their lived experiences outside school. Specifically, it draws on participatory focus group discussions with Palestinian youth (aged 13–15) who attended private, government and United Nations Relief and Work Agency (UNRWA)-run schools in the occupied West Bank. Whilst it was not an explicit aim of this study to analyse youth’s interpretations of settler colonialism, discussions about human rights led to conversations about their encounters with settler colonialism and their efforts to resist it.

Occupation normalised and Palestinian children decontextualised

The occupation has been normalised across large parts of the international community and Israel and has even come to be accepted among segments of Palestinian society itself. Normalisation of the occupation in the international arena has been achieved by the way in which Israel has successfully re-framed the relationship between Palestine and Israel as an ethno-religious ‘conflict’ rather than an anticolonial struggle (Browne and Bradley Citation2021; Roy Citation2012). Furthermore, when the state of Israel was established, it was framed as a ‘humanitarian solution’ to the Holocaust which also gave the earlier Zionist settler colonial project ‘an aura of legitimacy’ (Perugini and Gordon Citation2015, 46). Consequently, over time Palestinians have come to be represented as ‘intruders in their own land’ as opposed to an Indigenous people who have experienced forced displacement (Roy Citation2012, 80). Palestinians, including children, have also been decontextualised and re-framed either as terrorists or as victims of a humanitarian crisis devoid of agency.

Palestinian youth’s engagement at demonstrations against the occupation has been used by Israel to justify their surveillance and detention of Palestinian children (boys in particular but not solely) and to construct them as terrorists in-the-making who pose a threat to Israel’s security (Shalhoub-Kevorkian Citation2019). For instance, videos of Palestinian activist Ahed Tamimi first went viral when she was 11 years old and sought to intervene in her mother’s arrest by Israeli forces. In 2017, she was found in the spotlight again as a video emerged of her slapping an Israeli soldier in response to the shooting of her 15-year-old cousin – who was shot in the face with a rubber coated steel bullet (VanderZee Citation2019). Days later she was arrested (at age 16) during a night-time raid and served an eight-month sentence in an Israeli prison (Yotam Citation2018). Notably, not only was she labelled as a terrorist but also her childhood was questioned by Miri Regeve, Israeli Culture Minister, who argued ‘she is not a little girl, she is a terrorist. It’s about time they understood that people like her have to be in jail and not allowed to incite racism and subversion against the state of Israel’ (quoted in Holmes Citation2018). Framing Palestinian children as terrorists and denying them their childhood can be an effective strategy by which to disqualify them as the beneficiaries of children’s rights.

Alternatively, Palestinians have also been transformed into victims of a humanitarian crisis rather than a political one (Landy Citation2013) by the non-governmental organisation (NGO) sector and the international donor community. Following the signing of the Oslo Accords, foreign donors’ interest in funding projects focussed on ‘peace and co-existence’ and the two-state solution proposals (Pitner Citation2000, 35). Palestinian children were a particular target of these humanitarian initiatives. Projects involving children have appealed to foreign donors because of how children are perceived as politically neutral subjects and as mere victims of this so-called humanitarian crisis (Challand Citation2008). Thus, the trauma discourse has dominated humanitarian projects involving Palestinian children (Marshall Citation2013). However, these trauma relief projects do not address the causes of the ongoing trauma – the occupation – and they focus on individual healing rather than collective resilience (Marshall and Sousa Citation2017). Assumptions are made that Palestinian children are already traumatised, without naming the cause of that trauma, and that if left untreated they will inevitably turn to violence. As Marshall (Citation2013, 285) states, this creates ‘an image of a threatened but also threatening Palestinian child’. This way, Israel allows the decontextualisation of Palestinian children by portraying them as a psychological problem that warrants help from outside. Representing Palestinian youth as terrorists, intruders and victims has enabled Israel’s settler colonial violence to go largely unchallenged. And as Shalhoub-Kevorkian (Citation2015b, 238) comments, Palestinian children ‘occupy a liminal space in which their suffering is visible to the world, but they remain uncounted’.

Israel’s colonial project in the West Bank

As a result of the 1967 war, approximately 240,000 Palestinians were displaced alongside around 193,500 who were displaced for the second time (Badil Citation2015). Israel then began its military rule over Palestinians in the occupied West Bank, Gaza and East Jerusalem. The First Intifada in part led to peace initiatives and the signing of the Oslo Accords (1993–1995) as well as the establishment of the Palestinian Authority (PA) who were allotted areas of Gaza and the West Bank to govern. Due to the Oslo Interim Agreement, the West Bank became fragmented into three areas: Areas A, B, and C. Palestinian cities made up Areas A and to this day constitute 18% of the West Bank and are governed by the PA (Singer Citation2021). However, checkpoints, ID cards, the separation wall, permits and borders are methods by which Israel controls the mobility of Palestinians living in these enclaves within their own land and between Palestinian cities (Clarno Citation2018; Tawil-Souri Citation2012). The Israeli-controlled Area C today makes up 60% of the West Bank where settlements continue to be constructed (Singer Citation2021). Area C also acts as ‘strategic corridors’ that fragment the West Bank and Palestinians from one another (Gordon Citation2008, 36). Oslo and the dismemberment of the West Bank also enabled Israel to maintain control but eased them of the burden of responsibility towards the Palestinian people, whilst the PA gained the responsibilities of a state minus the sovereignty needed to enact the duties of one (Zreik Citation2004). Oslo not only led to this uneven distribution of land but also left the status of Jerusalem and the right of return for refugees unresolved. The establishment of the PA also enabled Israel to outsource security to a Palestinian security force who were assigned the role of suppressing their fellow Palestinians’ resistance against the occupation (Desai Citation2021). Moreover, the occupied Palestinian territory (oPt hereafter) was reconfigured into a humanitarian space rather than an illegal occupation (Landy Citation2013) for which the international community would remain largely responsible.

Changes to Israel’s colonial project were not only informed by the 1967 war and Oslo but also neoliberal restructuring. Israel’s economy began to transform in the 1980s from a ‘state-led, worker-centred economy focused on domestic consumption to a corporate-driven, profit-centred economy integrated into the circuits of global capital’ (Clarno Citation2018, 328). This neoliberal structuring and Oslo led to a diminished reliance on Palestinian labour, enabled the flow of foreign aid into the oPt and relieved Israel of some of the financial burden of military occupation in the West Bank (Tawil-Souri Citation2012). The PA’s economic approaches have also been underpinned by neoliberalism but ultimately controlled by Israel and shaped by the Word Bank, the International Monetary Fund, and the United States government (Clarno Citation2018). This has facilitated the formation of a small Palestinian elite made up of those from the political ruling class, capitalists from the diaspora and NGO officials who benefit off the back of the occupation – unlike most Palestinians living in the West Bank who face high rates of poverty, unemployment and curtailment of their freedoms (Clarno Citation2018; Farsakh Citation2005). Therefore, these enclaves have become sites of colonisation, inequality and ongoing repression. Despite these layers of oppression, Palestinians continue to struggle against factors that deepen settler colonial capitalism (Desai Citation2021).

When analysing the West Bank, Veracini (Citation2013) suggests that the Zionist project has reverted to a colonial model. He argues that the military occupation of the oPt, whilst necessary for the building of settlements, perpetuates the separation between native and settler and hinders the settlers’ ability to fully indigenise and consequently the ‘success’ of Israel’s settler colonial project. According to his analysis, this contrasts with how the settlers’ presence inside Israel has managed to become normalised to the point that they are no longer recognised as settlers but as natives. Nonetheless, these narratives around triumph and defeat have been found problematic as this approach risks privileging the settler historical narratives and neglecting the views of the colonised for whom the settler cannot become indigenised (Barakat Citation2018; Bhandar and Ziadah Citation2016). Moreover, in his efforts to differentiate colonialism from settler colonialism in the Israel–Palestine context, Veracini (Citation2013) implies that those living in land occupied in 1967 are not part of the Israeli settler colonial project, and in doing so he risks reinforcing the dismemberment of Palestinians in the West Bank from 48 Palestinians (Busbridge Citation2018). This analysis also potentially hampers the settler colonial framework’s ability to assist Palestinians and their struggle for autonomy and self-determination. The key features of the analytic as well as its inadequacies as highlighted by critical scholars are outlined below.

Features of the settler colonial analytic, its inadequacies and its application to Palestine

Distinct features of the settler colonial paradigm include the continuous displacement and dispossession of Indigenous people from their lands for the ongoing settlement of settler populations (Veracini Citation2007; Wolfe Citation2006, Citation1999). Settler colonialism, as Clarno (Citation2018, 324) explains, ‘operates through racial projects that devalue and dehumanize “native” populations, provide “ethical” or “legal” arguments for dispossession, and contribute to the formation of racialized structures of settler domination’. A return to settler colonial studies within western academe was largely prompted by the work of Wolfe (Citation2006, Citation1999) and developed by Veracini (Citation2015). According to Wolfe’s (Citation2006, Citation1999) analysis, settler colonialism is an ongoing structure rather than an event, and territorial expansion is crucial for the ‘elimination of the native’ and the establishment of the settler population upon that very land. Veracini (Citation2015) proposes that settlers aim to normalise their presence in the land to the point that they are no longer perceived as settlers but as Indigenous. Elsewhere, he also emphasises that what distinguishes settler colonialism from other forms of colonisation is the aim of elimination rather than exploitation of the native (Veracini Citation2011).

The settler colonial theoretical framework has been employed to analyse Israel–Palestine (Amoruso et al. Citation2019; Salamanca et al. Citation2012; Svirsky, Citation2014; Veracini Citation2015). Even prior to this more recent work, the 1967 war and the ensuing occupation of what became known as the oPt led to a greater engagement with the analytic among scholars in Palestine studies (Morris Citation1988; Pappe Citation1992; Rodinson Citation1973). Applying a settler colonial lens to analyse Zionism can be useful since it has the potential to redress how Palestinians have come to be portrayed as a side in a ‘conflict’ as opposed to an occupied people; expose Oslo’s liberal peace paradigm, thereby challenging the rhetoric of a two-state solution; and enable solidarity with other Indigenous struggles (Amoruso et al. Citation2019; Salamanca et al. Citation2012; Seidel Citation2021). However, scholars (Abu-Lughod, Citation2020; Barakat Citation2018; Busbridge Citation2018; Rifkin Citation2017) highlight how this borrowed framework does not always neatly map onto Israel–Palestine. Abu-Lughod (Citation2020, 12) observes that unlike other settler colonial contexts, the Zionist enterprise gained momentum as other states were undergoing processes of decolonisation and that unlike Indigenous people’s claims, a core feature of the Palestinian struggle has been the pursuit of ‘a national territory in a world of nation-states’. She also notes that Palestinians were ‘never pressured, or even allowed to assimilate’ (Abu-Lughod, Citation2020, 11). Scholars who are cautious about applying this analytic to Palestine argue that its value lies in the ‘alternative political futures’ that this comparison can ‘enable us to imagine’ such as new forms of activism, struggles for self-determination and solidarities (Abu-Lughod, Citation2020, 13; Rifkin Citation2017).

Indigenous scholars have also highlighted some of the limitations of this analytic when analysing settler colonial contexts, a topic that will now be discussed alongside its relevance to the Palestinian context. First, a key criticism of the framework among Indigenous academics is the way in which the knowledge, agency and acts of resistance by Indigenous scholars and activists have been marginalised within this field (Snelgrove, Dhamoon, and Corntassel Citation2014). This has been interpreted as another mode of ‘elimination of the native’ (Kauanui Citation2016). When it comes to the Palestinian context, Barakat (Citation2018) highlights how some of the earlier work by Palestinian scholars such as Sayegh (Citation1965), Sayigh (Citation2007), Said (Citation1979) and Hilal (Citation1976), who experienced first-hand the Zionist project as a settler colonial one before the expansion of this academic field among Western scholarship, has been often overlooked. For instance, Sayegh (Citation1965) writes about Zionism as a settler colonial movement and situates it within the context of European colonialism but at the same time notes it is distinct from other forms of settler colonialism. He argues that central to the Zionist settler enterprise is the ‘racial elimination’ of the native, as opposed to the ‘racial discrimination’ of the native through ‘hierarchical racial co-existence’ (Sayegh Citation1965, 24 and 27). Therefore, in this work from the 1960s, he highlights the structural and physical nature of settler colonial violence as well as the Zionist movement’s expansion of territory, racial self-segregation and opposition to assimilation.

Second, Wolfe’s emphasis on land as a more geographical space and how it is expropriated by the settler fails to capture the complexities of Indigenous people’s bonds to the land and how even when forcibly removed, rootedness to the land can remain intact (Konishi Citation2019; Moreton-Robinson Citation2015). Regarding Palestine, Abu-Lughod (Citation2020, 9) explains, whilst the hijacking of Palestinian culture is found irksome, it is the theft of their land and demolition of their properties and agriculture which is ‘the focus of their outrage’. For Palestinians, the possession of land (al-ard) is linked to the possession of honour (al-’ird) (Bisharat Citation1997). Therefore, the loss of land can have implications for their honour.

Third, aspects of the structural element of Wolfe and Veracini’s work have been found problematic since it suggests the success of the settler and, in turn, the disappearance of the native is inevitable. Indigenous scholar Moreton-Robinson (Citation2015) instead proposes the term ‘postcolonising’ for contexts that have yet to be decolonised. She supports the structural element that Wolfe proposes, and yet her term suggests more hopeful outlooks for Indigenous futures in that their anti-colonial struggles are on the way to being realised. Narratives of success and failure also risk privileging settler historical narratives and neglecting the views of the colonised for whom the settler cannot become indigenised (Barakat Citation2018; Bhandar and Ziadah Citation2016). Notably, these binaries are present in Veracini’s (Citation2013) analysis of the West Bank (discussed above), where he claims that Israel’s settler colonial enterprise has returned to a colonial model. This analysis has been criticised for dismissing settler colonial violence experienced by West Bank Palestinians and the barriers to assimilation faced by 48 Palestinians (Barakat Citation2018).

Fourth, scholars grappling with some of the limitations of the settler colonial analytic illustrate how the relationship between colonisation and capitalism has remained largely under-developed and that aims of elimination and exploitation are not necessarily distinguishable (Clarno Citation2018; Coulthard Citation2014; Desai Citation2021). Desai (Citation2021) and Clarno (Citation2018) argue that when applying the settler colonial analytic it is also important to integrate racial capitalism. Racial capitalism considers capitalist modes of dispossession that benefit from and reproduce class and patriarchal structures alongside racial hierarchies and how these continue and are connected to histories of colonialism and empire (Bhandar and Ziadah Citation2016; Robinson Citation2020). Regarding Palestine, Desai (Citation2021, 53) demonstrates how the logic of elimination alone fails to portray how Palestinians – largely land-owning fellahin displaced during the Nakba (the catastrophe) – were not only made refugees but also ‘proletarianized’ since they lost the lands they had previously owned. Clarno’s (Citation2018) research highlights how Palestinians in the West Bank encounter neoliberal colonisation because of Oslo, the establishment of the PA, the reliance on international aid, and the restructuring of the Israeli economy from a welfare economy to a globalised one.

Therefore, critical scholars argue that a more rigid commitment to Wolfe’s settler colonial model shuts down Indigenous agency and projects a ‘colonial fatalism’ onto the Indigenous (Konishi Citation2019; Macoun and Strakosch Citation2013, 435). Alternatively, Indigenous scholars have also acknowledged that aspects of this theory are useful when there is ‘meaningful engagement’ with the Indigenous (Kauanui Citation2016). This research sought the meaningful participation of Palestinian youth, as outlined below.

Research methodology

This study explores Palestinian youth’s conceptual understandings of human rights, and so a qualitative methodological approach was adopted to best achieve the research aims. The transformative paradigm emerged as a response to the lack of representation of minoritised groups in other research paradigms (Mertens Citation2007). It seeks to engage qualitatively with these groups, highlight versions of reality that get privileged, expose power inequalities and centre Indigenous knowledge. Therefore, as this research was concerned with accessing Indigenous knowledge, it was conducted in accordance with a broadly transformative approach.

Participatory focus groups were carried out with 96 Palestinian youth aged 13–15 across four schools in Areas A of the West Bank in 2015. This included a girls’ government school (GGS), a boys’ government school (BGS), a private (co-educational) school (PS) and a UNRWA girls’ school (UNGS) attended by child refugees. Therefore, this study was also comparative in that participants came from various religious (Christian, Muslim and secular) and socio-economic (villages, refugee camps and cities) backgrounds and learned about human rights through their schools’ different HRE approaches. Pupils were invited to take part in focus groups via their school principals and could opt out at any time. Sampling was purposive and aimed not only to capture the extent to which western narratives influence HRE in these schools but also to ensure children from elite and non-elite families, and refugee and non-refugee children, were represented. A total of 11 adults were also interviewed in these respective schools, including teachers who taught HRE, principals, a senior educator at UNRWA who had been involved in developing the HRE toolkit used in these schools and a school counsellor who had worked in all three school contexts.

Prior to undertaking this research, I had visited the West Bank numerous times and had established networks with educators and academics over time. Yet my raced, gendered and classed positionalities influence my research and interactions with research participants. As a white researcher with UK citizenship, my ability to conduct the research was made easier since I was able to travel freely through checkpoints and between areas of the West Bank in a way Palestinians cannot. Negotiating access to research sites with male officials was at times complicated by being a woman due to gender relations in Palestine. Conducting this research at a Northern Irish university facilitated access because of the history of Irish–Palestinian solidarity, as did my decision to live in the West Bank and learn Arabic. Participants were very open to my research project, often stating how they wanted those in Ireland and beyond to hear about their experiences. Being from a working-class background also granted me an ease when relating to working-class Palestinians. I kept a reflective journal whilst conducting fieldwork to help monitor my positionality in relation to the research participants, the Young Persons Advisory Groups (YPAGs hereafter), and the context but also the ‘geopolitics of knowledge’ (Mignolo Citation2002, 59). My journal included reflections on my time spent with participants but also other experiences whilst I lived in the West Bank. I endeavoured to acknowledge underlying views and orientalist attitudes when they emerged during the research process (Jiménez Citation2021).

This research adopted a children’s rights-based approach and was conducted in consultation with two YPAGs made up of Palestinian youth who closely represented the child participants (Lundy and McEvoy Citation2009). Working alongside a YPAG can enable the researcher to know what questions to ask and how best to ask other youth about the topics being examined. The YPAGs were consulted on the research design, selection of the methods and analysis of the data. For instance, the YPAGs co-crafted the questions that their peers would be asked and recommended I conduct participatory activities that were more discussion- and group-based.

YPAG 1 was made up of six youth (four male and two female) aged 14–15 who attended a private school, and YPAG 2 consisted of six refugee girls aged 12–13 who attended a UNRWA-run school. These youth were recruited voluntarily to take part through their schools and could opt out at any time. Conducting research under the guidance of local YPAGs has the potential to be a decolonising strategy since they can suggest methods that are more appropriate to the Palestinian cultural context and provide a more nuanced analysis of their peers’ views. Analysis is an active process that is influenced by the positionality of the researcher along with the YPAGs, the research context and the data itself (Braun, Clarke, and Hayfield Citation2023). Additionally, western researchers often impose interpretations onto the narratives of subalterns (Spivak Citation1988); therefore, working with local YPAGs served to hinder some of my colonial tendency to inflict my own voices onto the child participants (for a thorough discussion on the process of working with a YPAG and its decolonising potential see Jiménez Citation2021). Therefore, the YPAG’s analysis guided my own analysis of the data, which indicated that Palestinian youth encounter three layers of marginalisation in their struggle for human rights: the occupation, which disqualifies them as the ‘humans’ of human rights; the authoritarian Palestinian quasi-state that hinders their voice; and the patriarchal aspects of their culture that deny them agency (Jiménez Citation2018). This paper attends to the first and second layers of marginalisation and how through discussions it is possible to ascertain their interpretations of settler colonialism.

Youth who took part in this study either as participants or in a YPAG had access to school counsellors and relevant staff who would provide long-term support after discussions had taken place. Focus groups and YPAG sessions were only conducted where written informed consent had been given by all. Ethical approval for this study was obtained by the (then) School of Education Ethics Standing Committee at Queen’s University Belfast.

Findings

De-normalising colonial violence and redressing misrepresentations

Whilst youth may not have used the term settler colonialism explicitly in their discussions, they were aware that as Palestinians they are targets of Israel’s ‘logic of elimination’ (Wolfe Citation2006: 387). As one boy simply put it: ‘The occupation wants to delete us’ (BGS).

They were also mindful of how settler colonial violence towards children has come to be accepted in the international arena, equating their lives to mere ‘numbers’. When describing their everyday encounters with settler colonial processes, they exposed the Israel–Palestine relationship as one between occupier and occupied rather than warring parties. For instance, one group of refugee girls recounted a military raid that had taken place in their camp the previous night:

Girl 1: Like yesterday Israeli soldiers were shooting guys spontaneously with live bullets.

Girl 2: They invaded the camp last night.

Girl 3: Yeah they came at 10.00pm and hit a pregnant woman.

[…]

Girl 1: They were searching for someone and they just broke into her house and they pushed her out of their way.

Girl 3: Last night they were so angry as they were shooting anyone in their way.

Girl 4: My cousin was on the roof of our house just looking around to see what was happening and he was shot in his leg. Now he is in the hospital because yesterday he went into surgery.

Girl 1: There was another guy who was shot in his knee.

[…]

Girl 2: They shut off the electricity in all the houses in the camp. We were scared. (UNGS)

Notably, this encounter between the armed Israeli soldiers and refugee child participants took place in a camp in a PA-controlled Area A of the West Bank which is supposedly off-bounds for Israelis. As Shalhoub-Kevorkian (Citation2015a) argues, these night-time raids raise questions often missing in discussions on the children’s rights in Palestine, such as: What is the settler doing in a Palestinian community? By including the way the pregnant woman is treated by soldiers, these girls expose the asymmetry during these encounters and challenge dominant discourses on Israel–Palestine relations. They also counter the Israeli-constructed and internationally accepted depictions of Palestinian children (and adults) as terrorists and instigators of violence, since they were woken up by armed soldiers whilst in bed. However, it is not that these girls planned to make these arguments, they were simply reiterating an encounter they had lived through less than 24 hours before. Youth’s accounts of settler colonial violence dismantled Veracini’s (Citation2013) analysis of the West Bank and confirmed his critics’ assertions that Israel’s eliminatory logic is still very much at play in this context (Barakat Citation2018).

Youth also contested how they have come to be portrayed as ‘intruders in their own land’ (Roy Citation2012, 80) as opposed to a dispossessed people, as the following girl’s commentary illustrates:

People are sleeping about Palestine … they think that … it doesn’t really belong to the Palestinians. That’s why maybe they don’t want to listen … they don’t want to hear anything about it because they don’t want to really believe that it’s … a Palestinian land and not an Israeli [land]. (PS)

Anticipating decolonisation not elimination

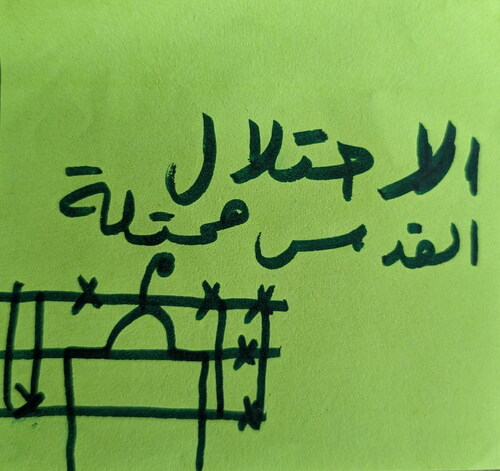

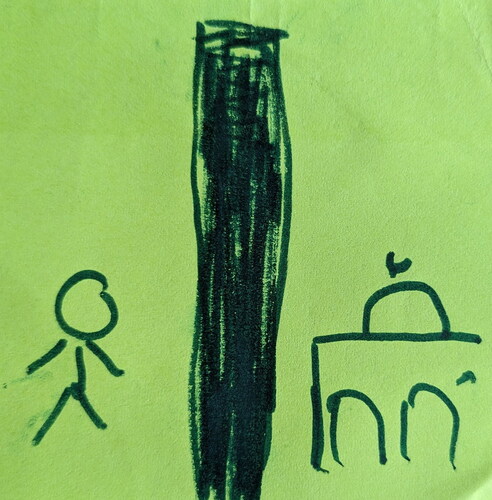

As discussed, apparent in the settler colonial literature is a preoccupation with binaries of success–failure of the settler–native. Implied in these hegemonic binaries is the assumption that the elimination of the colonised is unavoidable. Alternatively, youth in this study largely anticipated that their right to self-determination and return to their ancestral lands will one day be achieved – rather than their elimination. This was demonstrated in their appropriation of symbols inherent in the political narrative of Palestinian refugees into their own discourse. Youth reproduced images of the key (see ) and the iconic cartoon character of a barefoot refugee child known as Handala drawn by the cartoonist and Palestinian refugee Al Ali in 1969 (see ).

Figure 2. Handala.

Source: Private school.

They incorporated into their narratives symbols that represent the right of return (awda) and United Nations Resolution 194, which has yet to be resolved for Palestinians displaced during the Nakba. Literature on Palestinian refugees explains that families kept the keys to their original homes and used these as a form of concrete evidence of their personal experience of loss (Culcasi Citation2016). The frequent references to the key indicate that it is not merely a nostalgic artefact pointing to the past but has come to symbolise refugees’ anticipation that their right to return will be one day fulfilled (Feldman Citation2008). After drawing the image of a key, this boy further clarified what this symbol meant to him: ‘We can’t go back to our original house in Haifa, in Yafa … because it’s with Israelis, they came and they took it’ (PS).

Referring to the Nakba and how settlers ‘came’ from elsewhere and took the houses of Palestinians, he alludes to the structure of settler colonialism. Elsewhere, youth reintroduced the historical frame which is often erased in commentaries on Israel–Palestine, and did this to ‘maintain a remembered presence as Indigenous peoples’ (Atallah Citation2017, 370): ‘They took … over our land, they humiliate us …. You know sometimes they hit women, they hit children’ (boy, PS).

This boy binds the past (‘they took’) and the present (‘they humiliate… they hit’) acts of the settler within this one utterance. Again, the importance of land is emphasised by the youth. In the Palestinian cultural consciousness, land ownership and honour are intertwined (Bisharat Citation1997); therefore, when discussing a return to ancestral lands what is often also being conveyed is a return to honour (Atallah Citation2017).

Whilst the structural aspect of the analytic seems to assist Palestinian youth to make sense of the ongoing colonial violence they experience, their narratives seem to cast a more hopeful outlook onto Palestinian futures than the analytic would allow. Instead of expecting their eventual elimination they seem to anticipate that their decolonisation will one day be realised. This is more reflective of Indigenous contributions, especially Moreton-Robinson’s (Citation2015) notion of ‘postcolonising’ which supports the structural aspect of the framework and yet shirks its ‘colonial fatalism’ (Macoun and Strakosch Citation2013, 435). Alternatively, youth scrutinised how some of their older relatives have come to accept the occupation: ‘But we feel that adults have lost hope, for example, the right to return to our country, we still have hope but adults waited for … years and nothing has changed so they lost hope’ (girl, UNGS).

At times their analyses seemed to suggest that certain adults may have come to anticipate the settlers’ success. Despite this and the indifference of the international community, youth in this study, irrespective of whether they lived in refugee camps or villages or enjoyed socio-economic privileges, considered themselves to be protagonists within the resistance to Israel’s settler colonial project, as this girl asserted:

[Adults] should notice that the younger people are fighting, like when you look at the Palestinian issue, you will see that the … majority of people in jails or that are having huge conflicts with the occupation are of the younger generations. (PS)

Rejecting the dismemberment of Palestine

Child participants in this research had only known life post-Oslo, and parts of the land that their relatives were forced to flee remain largely inaccessible (Gould Citation2014). Nevertheless, according to the imagined geography of many participants, Palestine geographically remains the same as it did before the Nakba of 1948 and the Naksa (the setback) of 1967, as this girl’s comment illustrates: ‘Today we had a lesson with the title “Palestinians in Israel”, and our teacher changed it to “Palestinians in occupied Palestine” – and we love that’ (UNGS).

The teacher’s deviation from the taught curriculum can be interpreted as a mode of resistance to the settler colonial fragmentation of the Palestinian people from one another and their lands, which is in turn celebrated by the class. Elsewhere, youth and their educators discussed the challenges of being severed from other parts of the land such as Gaza, coastal towns and particularly Jerusalem. Educators also resisted fragmentation of the land; the following principal expressed her yearning for her pupils to know Jerusalem as well as other places such as Yafa:

You know how much students like journeys and to go for picnics, but we can’t take them … ‘You should know about Jerusalem, you should know about Yafa’ … ‘Ok, take me there …’ [mimics child’s voice]. ‘I can’t. It’s forbidden’. Who could let them know the meaning of ‘It’s forbidden?’ (UNGS)

Figure 3. Occupied Jerusalem.

Source: Girls’ government school.

Figure 4. Separation from Jerusalem.

Source: Private school.

In their discussions and drawings youth sought to resist their separation from other parts of the land as a decolonial strategy to counter the way they have been dislocated materially and discursively over time from one another and from their lands (Seidel Citation2021).

Refusing to be uprooted

Indigenous inhabitants are often constructed by colonisers as nomads who are rootless and therefore disposable (Wolfe Citation2006). However, youth in this study asserted their rootedness to the land as they included their responses to the settler colonial project in the West Bank. This was particularly evident when one boy described how his uncle had been killed by Israeli forces whilst planting olive trees. As he spoke, he adjoined his uncle’s stewardship of physical land to the symbolic collective national right of Palestinians to this same land by stating that it was ‘his and our lands’ (PS). Whilst this experience was about the planting of literal olive trees, on a symbolic level, the olive tree has often been used as a representation of steadfastness (sumud) due to the fact that it remains rooted despite changes to the climate (Gould Citation2014). The olive tree has also become an icon of Palestinian nationalism with multiple meanings. It can represent Palestine itself, the land and the determination of the people to stay. There is also an intergenerational aspect to the planting of olive trees in that Palestinian farmers plant olive trees for future generations, often citing the Palestinian proverb ‘Gharasu fa-akalna wa-naghrosu fa-yaekolun’ (‘They [past generations] planted so we ate and we plant so they [future generations] eat’) (Abufarha, Citation2008, 358). Therefore, this act of planting also facilitates the bond of future generations with the land. This boy, by narrating his family’s recent story of dispossession and loss, which ties into the broader Palestinian discourse, strengthened the boys’ resolve to remain in the land, as demonstrated through his assertion – ‘we will stay’ (PS). This refusal to be uprooted was articulated elsewhere by other participants such as when they discussed how, as part of their school’s community outreach work, ‘we build the houses that the occupation destroyed’ (PS). Therefore, their very refusal to be uprooted and their insistence on staying put can be interpreted as an act of resistance in the settler colonial context (Peteet Citation2017). Their accounts yet again lend support to the Indigenous arguments that contend rootedness to the land can remain firm even when the colonised have been displaced from their lands (Konishi Citation2019; Moreton-Robinson Citation2015).

Exposing neoliberal colonisation

Youth criticised how the occupation has come to be accepted in the international arena but also by some parts of Palestinian society itself, including the Palestinian government and ruling elites. Referring to the war in Gaza that took place in 2014, this girl commented: ‘Our government acts as if like they don’t care whether we are occupied or not […]. Israelis are killing kids and the government is not letting Israel pay for it’ (PS). In her condemnation of the PA’s inaction in the wake of settler colonial violence towards Gazan children, she demonstrates how she refuses to be dislocated from her Palestinian peers in parts of Palestine from whom she is severed.

As Desai (Citation2021) contends, consideration must be taken of emerging class hierarchies within settler colonial sites when adopting the settler colonial critique. These differences in class shaped the analysis of the complex political relationship between the PA and Israel articulated by the youth. Whilst educators at UNRWA and government schools were less inclined to criticise the PA due to fears around surveillance via the Ministry of Education, other youth discussed the role of the PA’s security forces in instilling fear among the population and preventing resistance. This boy explained:

In 2001, there was a resistance to the occupation but after the death of President Yasser Arafat, our current president chose to negotiate with Israel. Consequently, we are not supposed to struggle or raise our voice against Israel because Israel will offer us a ‘good life’. (BGS)

These boys who attended the government school were from lower-income families and were therefore more likely to bear the brunt of such measures. They offered examples of how this had been experienced in healthcare and education. Whilst they did not use terms such as ‘neoliberalism’ and ‘racial capitalism’, their different analyses offered insights into how these factors play out in their everyday lives. In doing so, they once more challenged the more reductionist approach to settler and native binaries found in Wolfe’s work since they exposed ways that the native can become a collaborator with the occupier. Therefore, Clarno’s (Citation2018) framework, which considers neoliberal colonisation, may be helpful in enabling non-elite Palestinian youth to understand the various injustices they experience. Being able to make sense of the workings of neoliberal capitalism may also offer paths of solidarity with other Indigenous struggles and antiracism movements.

Conclusions

This article has contributed to debates that extend settler colonial theory and scrutinise the applicability of the paradigm to analyse Palestine. It has argued that the settler colonial framework does not map neatly onto the West Bank. Instead, Indigenous theorisations of settler colonialism along with Clarno’s (Citation2018) framework of neoliberal colonisation seem more relevant to Palestinian youth and may better assist them in understanding, articulating and strategising against settler colonialism than interpretations found in mainstream analyses such as in the work of Wolfe and Veracini. However, dimensions of the analytic can still be useful when it comes to challenging the way Palestinians and Israel–Palestine relations have been portrayed. Overall, what this study indicates is that the settler colonial analytic needs to undergo renewal and create space for epistemic diversity.

The findings I have presented suggest that youth’s readings of settler colonialism contrast with Veracini’s (Citation2013) analysis of the West Bank in that they make it clear that they are still very much part of Israel’s settler colonial project and its logic of elimination. And whilst the colonialist project in Israel (as opposed to the West Bank) may be deemed a ‘success’ within certain theoretical debates in the field of settler colonial studies (Veracini Citation2013) or accepted in the international arena, for these youth, as with other colonised groups, the settler cannot become indigenised (Mamdani Citation2015). Building on Indigenous arguments, the significance of the land is emphasised by these youth in a way that is missing in Wolfe and Veracini’s work (who focus on settler expropriation of land) in that their connectedness to the land is tied up with notions of honour, sumud, and past and future intergenerational struggles. They refuse to accept the dismemberment of Palestine, resist how they have come to be separated from one another and their lands and assert their rootedness to the land.

Youth were integrating racial capitalism into their discussions of settler colonialism even if they did not use such terms explicitly. They analysed the entanglement of neoliberalism and colonialism in their everyday lives. Therefore, this paper suggests that Clarno’s (Citation2018) framework of neoliberal colonisation has the potential to further assist youth, especially from non-elite families, to understand the layers of inequalities they face as well as why their participation in demonstrations is met with opposition from fellow Palestinians working for the PA’s security forces. Their narratives demonstrate that the settler colonial theory’s binaries around settler and native do not neatly correspond to their situation, since natives can become collaborators with the occupation because of Israel’s conscription of Palestinians into its neoliberal settler colonial project (Clarno Citation2018).

Despite its limitations, the settler colonial paradigm’s potential seems to lie in its ability to de-normalise settler colonial violence and contest dominant narratives in international discourses about the Israel–Palestine relationship. The structural aspect of the analytic also enables youth to make sense of their current encounters with settler colonial processes in light of historic events – in other words, the ongoing Nakba they experience. However, I suggest that to allow Palestinians to shirk the imposition of ‘colonial fatalism’ (Macoun and Strakosch Citation2013, 435), Moreton-Robinson’s (Citation2015) concept of ‘postcolonising’ may offer more hopeful political futures for Palestinian youth – that decolonisation rather than their elimination is inevitable.

Since this study was confined to youth in the West Bank, it was not possible to access the views of those living in other places under Israel’s occupation such as East Jerusalem, Gaza and the Syrian Golan Heights; therefore, it is unknown whether such narratives would emphasise other theorisations of settler colonialism. More research accessing the views of these youth is needed.

Throughout, this paper has maintained that the inclusion of Palestinian youth’s theorisations of settler colonialism is important since they may shed light on the intricacies and particularities of how settler colonialism plays out in the West Bank in a way that is missing in Palestinian adults’ accounts or western scholarship. For instance, in this research, adults were not as comfortable offering their criticisms of the PA and its security arrangement with the occupation nor their capitalist politics. Therefore, youth discussions of the interplay between settler colonialism and neoliberalism might not have been captured to the same extent had youth not been interviewed. Similarly, through their accounts, refugee children raise an issue barely present in discourses on children’s rights in Palestine – that settlers are entering areas that are supposedly under PA control and off-limits for Israelis. Finally, most youth also anticipated more hopeful possibilities for the Palestinian people than some of the adults they know who may have come to believe their elimination is inevitable.

By centring Palestinian youth’s interpretations, agency and acts of resistance to settler colonialism, this paper has attempted to respond to Barakat’s (Citation2018, 356) argument that ‘indigeneity must be the frame of how we read settler colonial studies’. Further, elevating these narratives within research can also help facilitate the formation of solidarities with other youth living in settler colonial contexts elsewhere.

Acknowledgements

The author acknowledges the contributions made by all participants, YPAG members, and the schools that facilitated their participation. Additional thanks to Jumana Kaplanian, her translator. Thanks to the anonymous reviewers for their helpful recommendations.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Erika Jiménez

Erika Jiménez, PhD, is a Leverhulme Early Career Fellow at the School of Law, Queen’s University Belfast, working on a project entitled ‘Golani youth, human rights and the forgotten occupation’. Her research interests include decolonial approaches to human rights, childhood and research.

Bibliography

- Abufarha, N. 2008. “Land of Symbols: Cactus, Poppies, Orange and Olive Trees in Palestine.” Identities 15 (3): 343–368. doi: 10.1080/10702890802073274

- Abu-Lughod, L. 2020. “Imagining Palestine’s Alter-Natives: Settler Colonialism and Museum Politics.” Critical Inquiry 47 (1): 1–27. doi: 10.1086/710906

- Amoruso, F., I. Pappé, and S. Richter-Devroe. 2019. “Introduction: Knowledge, Power, and the ‘Settler Colonial Turn’ in Palestine Studies.” Interventions 21 (4): 451–463. doi: 10.1080/1369801X.2019.1581642

- Atallah, D. 2017. “A Community-Based Qualitative Study of Intergenerational Resilience with Palestinian Refugee Families Facing Structural Violence and Historical Trauma.” Transcultural Psychiatry 54 (3): 357–383. doi: 10.1177/1363461517706287

- Badil. 2015. Survey of Palestinian Refugees and Internally Displaced Persons 2013–2015. Vol. 8. Bethlehem: BADIL Resource Center for Palestinian Residency and Refugee Rights. https://www.badil.org/phocadownloadpap/badil-new/publications/survay/Survey2013-2015-en.pdf

- Balagopalan, S. 2019. “Childhood, Culture, History: Redeploying ‘Multiple Childhoods.” In Reimagining Childhood Studies, edited by S. Spyrou, R. Rosen, and D. T. Cook, 23–39. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Barakat, R. 2018. “Writing/Righting Palestine Studies: Settler Colonialism, Indigenous Sovereignty and Resisting the Ghost(s) of History.” Settler Colonial Studies 8 (3): 349–363. doi: 10.1080/2201473X.2017.1300048

- Bhandar, B., and R. Ziadah. 2016. “Acts and Omissions: Framing Settler Colonialism in Palestine Studies.” Jadaliyya, January 14. https://www.jadaliyya.com/Details/32857

- Bisharat, G. E. 1997. “Exile to Compatriot: Transformations in the Social Identity of Palestinian Refugees in the West Bank.” In Culture, Power, Place: Explorations in Critical Anthropology, edited by A. Gupta and J. Ferguson, 203–233. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Braun, V., V. Clarke, and N. Hayfield. 2023. Thematic Analysis: A Reflexive Approach. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

- Browne, B. C., and B. Bradley. 2021. “Promoting Northern Ireland’s Peacebuilding Experience in Palestine–Israel: Normalising the Status Quo.” Third World Quarterly 42 (7): 1625–1643. doi: 10.1080/01436597.2021.1903310

- Busbridge, R. 2018. “Israel-Palestine and the Settler Colonial ‘Turn’: From Interpretation to Decolonization.” Theory, Culture & Society 35 (1): 91–115. doi: 10.1177/0263276416688544

- Challand, B. 2008. Palestinian Civil Society: Foreign Donors and the Power to Promote and Exclude. London: Routledge.

- Clarno, A. 2018. “Neoliberal Colonization in the West Bank.” Social Problems 65 (3): 323–341. doi: 10.1093/socpro/spw055

- Coulthard, G. S. 2014. Red Skin, White Masks: Rejecting the Colonial Politics of Recognition. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Culcasi, K. 2016. “Images and Imaginings of Palestine: Territory and Everyday Geopolitics for Palestinian Jordanians.” Geopolitics 21 (1): 69–91. doi: 10.1080/14650045.2015.1100993

- Darweish, M., and A. Rigby. 2015. Popular Protest in Palestine: The Uncertain Future of Unarmed Resistance. London: Pluto Press.

- Defense for Children International (DCI) Palestine. 2021. “2021 is Deadliest Year for Palestinian Children Since 2014.” 10 December. https://www.dci-palestine.org/2021_is_deadliest_year_for_palestinian_children_since_2014

- Desai, C. 2021. “Disrupting Settler-Colonial Capitalism: Indigenous Intifadas and Resurgent Solidarity from Turtle Island to Palestine.” Journal of Palestine Studies 50 (2): 43–66. doi: 10.1080/0377919X.2021.1909376

- Farsakh, L. 2005. Palestinian Labour Migration to Israel: Labour, Land and Occupation. London: Routledge.

- Feldman, I. 2008. “Refusing Invisibility: Documentation and Memorialization in Palestinian Refugee Claims.” Journal of Refugee Studies 21 (4): 498–516. doi: 10.1093/jrs/fen044

- Gordon, N. 2008. “From Colonization to Separation: Exploring the Structure of Israel’s Occupation.” Third World Quarterly 29 (1): 25–44. doi: 10.1080/01436590701726442

- Gould, R. 2014. “Sumud: The Palestinian Art of Existence.” World Policy Journal 31 (3): 99–106. doi: 10.1177/0740277514552979

- Hilal, J. 1976. “Imperialism and Settler Colonialism in West Asia: Israel and the Arab Palestinian Struggle.” Utafi 1 (1): 51–70.

- Holmes, O. 2018. “Palestinian Ahed Tamimi Accepts Prison Term Plea Deal.” The Guardian, March 21. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/mar/21/palestinian-ahed-tamimi-accepts-plea-deal-to-serve-eight-months-in-jail

- Jiménez, E. 2021. “Decolonising Concepts of Participation and Protection in Sensitive Research with Young People: Local Perspectives and Decolonial Strategies of Palestinian Research Advisors.” Childhood 28 (3): 346–362. doi: 10.1177/0907568221102558

- Jiménez, E. 2018. “Palestinian Young People’s Perspectives and Experiences of Human Rights, inside and outside Schools: A Participatory Qualitative Study in the Occupied West Bank.” PhD thesis, Queen’s University Belfast, UK.

- Kauanui, J. K. 2016. “A Structure, Not an Event.” Lateral 5 (1). doi: 10.25158/L5.1.7

- Konishi, S. 2019. “First Nations Scholars, Settler Colonial Studies, and Indigenous History.” Australian Historical Studies 50 (3): 285–304. doi: 10.1080/1031461X.2019.1620300

- Landy, D. 2013. “Talking Human Rights: How Social Movement Activists Are Constructed and Constrained by Human Rights Discourse.” International Sociology 28 (4): 409–428. doi: 10.1177/0268580913490769

- Lundy, L., and L. McEvoy. 2009. “Developing Outcomes for Education Services: A Children’s Rights-Based Approach.” Effective Education 1 (1): 43–60. doi: 10.1080/19415530903044050

- Macoun, A., and E. Strakosch. 2013. “The Ethical Demands of Settler Colonial Theory.” Settler Colonial Studies 3 (3-04): 426–443. doi: 10.1080/2201473X.2013.810695

- Mamdani, M. 2015. “Settler Colonialism: Then and Now.” Critical Inquiry 41 (3): 596–614. doi: 10.1086/680088

- Marshall, D. J. 2013. “‘All the Beautiful Things’: Trauma, Aesthetics and the Politics of Palestinian Childhood.” Space and Polity 17 (1): 53–73. doi: 10.1080/13562576.2013.780713

- Marshall, D. J., and C. Sousa. 2017. “Decolonizing Trauma: Liberation Psychology and Childhood Trauma in Palestine.” Conflict, Violence and Peace 11: 287–306. doi: 10.1007/978-981-287-038-4_7

- Mertens, D. 2007. “Transformative Paradigm: Mixed Methods and Social Justice.” Journal of Mixed Methods Research 1 (3): 212–225. doi: 10.1177/1558689807302811

- Mignolo, W. 2002. “The Geopolitics of Knowledge and the Colonial Difference.” South Atlantic Quarterly 101 (1): 57–96. doi: 10.1215/00382876-101-1-57

- Moreton-Robinson, A. 2015. The White Possessive: Property, Power, and Indigenous Sovereignty. Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press.

- Morris, B. 1988. The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem, 1947–1949. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Pappe, I. 1992. The Making of the Arab-Israeli Conflict, 1947–1951. London: I.B. Tauris.

- Perugini, N., and N. Gordon. 2015. The Human Right to Dominate. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Peteet, J. 2017. Space and Mobility in Palestine. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Pitner, J. 2000. “NGOs’ Dilemmas.” Middle East Report (214): 34. http://www.merip.org/mer/mer214/ngos-dilemmas. doi: 10.2307/1520193

- Rifkin, M. 2017. “Indigeneity, Apartheid, Palestine: On the Transit of Political Metaphors.” Cultural Critique 95 (1): 25–70. doi: 10.5749/culturalcritique.95.2017.0025

- Robinson, C. 2020. Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

- Rodinson, M. 1973. Israel: A Colonial-Settler State? New York: Monad Press.

- Roy, S. 2012. “Reconceptualizing the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict: Key Paradigm Shifts.” Journal of Palestine Studies 41 (3): 71–91. doi: 10.1525/jps.2012.XLI.3.71

- Said, E. W. 1979. The Question of Palestine. London: Routledge.

- Salamanca, O. J., M. Qato, K. Rabie, and S. Samour. 2012. “Past is Present: Settler Colonialism in Palestine.” Settler Colonial Studies 2 (1): 1–8. doi: 10.1080/2201473X.2012.10648823

- Sayegh, F. A. 1965. Zionist Colonialism in Palestine. Beirut: Palestine Liberation Organization Research Center.

- Sayigh, R. 2007. The Palestinians: From Peasants to Revolutionaries. London: Zed.

- Seidel, T. 2021. “Settler Colonialism and Land-Based Struggle in Palestine: Toward a Decolonial Political Economy.” In Political Economy of Palestine. Middle East Today, edited by A. Tatir, T. Dana, and T. Seidel, 81–107. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Shalhoub-Kevorkian, N. 2019. Incarcerated Childhood and the Politics of Unchilding. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Shalhoub-Kevorkian, N. 2015a. “Childhood: A Universalist Perspective for How Israel is Using Child Arrest and Detention to Further Its Colonial Settler Project.” International Journal of Applied Psychoanalytic Studies 12 (3): 223–244. doi: 10.1002/aps.1456

- Shalhoub-Kevorkian, N. 2015b. “Necropolitical Debris: The Dichotomy of Life and Death.” State Crime Journal 4 (1): 34–51. doi: 10.13169/statecrime.4.1.0034

- Singer, J. 2021. “West Bank Areas A, B and C- How Did They Come into Being?” International Negotiation 26 (3): 391–401. doi: 10.1163/15718069-bja10030

- Snelgrove, C., R. Dhamoon, and J. Corntassel. 2014. “Unsettling Settler Colonialism: The Discourse and Politics of Settlers, and Solidarity with Indigenous Nations.” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 3 (2): 1–32.

- Spivak, C. 1988. “Can the Subaltern Speak?” In Can the Subaltern Speak?: Reflections on the History of an Idea, edited by R. Morris, 21–78. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Svirsky, M. 2014. “The Collaborative Struggle and the Permeability of Settler Colonialism.” Settler Colonial Studies 4 (4):327–333. doi: 10.1080/2201473X.2014.911649

- Tawil-Souri, H. 2012. “Uneven Borders, Coloured (Im)Mobilities: ID Cards in Palestine/Israel.” Geopolitics 17 (1): 153–176. doi: 10.1080/14650045.2011.562944

- VanderZee, L. 2019. “Ahed Tamimi and the Symbolization of Appearance, Childhood, and Gender.” Theory in Action 12 (2): 99–114. doi: 10.3798/tia.1937-0237.1914

- Veracini, L. 2015. “What Can Settler Colonial Studies Offer to an Interpretation of the Conflict in Israel-Palestine?” Settler Colonial Studies 5 (3): 268–271. doi: 10.1080/2201473X.2015.1036391

- Veracini, L. 2013. “The Other Shift: Settler Colonialism, Israel, and the Occupation.” Journal of Palestine Studies 42 (2): 26–42. doi: 10.1525/jps.2013.42.2.26

- Veracini, L. 2011. “Introducing Settler Colonial Studies.” Settler Colonial Studies 1 (1): 1–12. doi: 10.1080/2201473X.2011.10648799

- Veracini, L. 2007. “Settler Colonialism and Decolonization.” Borderlands e-Journal 6 (2).

- Wolfe, P. 2006. “Settler Colonialism and the Elimination of the Native.” Journal of Genocide Research 8 (4): 387–409. doi: 10.1080/14623520601056240

- Wolfe, P. 1999. Settler Colonialism and the Transformation of Anthropology: The Politics and Poetics of an Ethnographic Event. London: Cassel.

- Yotam, B. 2018. “Palestinian Teen Ahed Tamimi Reaches Plea Bargain, to Serve 8 Months in Israeli Prison.” Haaretz, March 21. https://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/palestinian-teen-ahed-tamimi-reaches-plea-bargain-to-serve-8-months-i-1.5933423

- Zreik, R. 2004. “Palestine, Apartheid, and the Rights Discourse.” Journal of Palestine Studies 34 (1): 68–80. doi: 10.1525/jps.2004.34.1.68