Abstract

Conflict generates uncertainty and a supply of violent actors willing to contract their services to third parties that makes identifying motivation for civilian victimisation difficult. In this paper, I examine how elites not only have opportunities to capitalise on violence during war for developmental interests, but also take advantage of the fog of war to lump all cases of victimisation under a clear overarching narrative of political contestation rather than repression for economic interests. I build on the literature of developmental violence in conflict to assess two cases of dam construction by the Public Enterprises of Medellin (EPM) in Antioquia, Colombia between 1995 and 2018: Hidroituango and Porce II. I argue that civilians opposing the dams were associated with one of the armed groups in the territory and elites dismissed their victimisation as a product of competition between insurgents and counterinsurgents. This conflict narrative obscures other potential realities and precludes deeper investigation into the ambiguous motivations behind attacks, even as the victims themselves may challenge and present counternarratives of developmental violence.

Introduction

War generates overlapping patterns of violence and motivation for civilian victimisation. On one level there are the clear-cut political aims of armed actors disputing territory with the aim to establish political authority; in civil wars this is the realm of the insurgent vs the state. Civilian victimisation is conceptualised along a logic of territorial competition, where civilians are killed for supporting the wrong group or as innocent bystanders (Steele Citation2017; De la Calle Citation2017; Stanton Citation2015; Kalyvas Citation2006). Counterinsurgent militias or paramilitary proxies complicate the landscape further and muddy the ability to determine the sequence of events and motivation behind civilian victimisation (Williamson Citation2023; Carey, Colaresi, and Mitchell Citation2015). On another level, developmental elites – private and state actors involved in large-scale infrastructure – may also rely on extra-legal violence during conflict to advance their economic interests against civilian challengers (Le Billon and Lujala Citation2020; Middeldorp and Le Billon Citation2019; McNeish Citation2018). Reno argues that this collaboration between elites and conflict actors is often perceived as ‘[t]he cheapest and most efficacious option for indirect management of disorder’ (Reno Citation2004, 623).

Armed conflict, however, does not simply offer elites opportunities to advance their interests through violence but also offers the discursive capacity to obscure personal or economic incentives in civilian repression. As Tellez (Citation2022, 407) notes, civil wars are ‘information-poor environments where uncertainty reigns as to which actors are responsible for what actions’. In Colombia, for instance, a large proportion of wartime deaths are never attributed to a known perpetrator (Echandía and Salas Citation2008). This heightens the fog of war not just for soldiers, but for civilians and researchers, who try to divine motive from imprecise or muddled accounts of victimisation. As a result, both academic and policy audiences seek simpler narratives of conflicts where ‘disputes are conceptualised as having single-issue causal factors’ (Olumba et al. Citation2022, 2084), rather than examine the relationship between these overlapping patterns of violence.

In this paper, I argue that the uncertainty of war provides elites a narrative that associates civilians to armed groups and dismisses other motives for their victimisation, including development interests. I build on scholarship that examines the links between extra-legal violence and developmental elites to show how elites can take advantage of the uncertainty of war in what I call an ‘elite inversion’ of Kalyvas (Citation2006, 338) ‘malicious denunciation’ to advance individual interests. In this article, I demonstrate how the framing of a political armed conflict becomes entangled with developmental interests and challenges. I present my findings – based on interviews with local leaders, project managers, and international observers, and secondary data collected from archival sources – in the displacement and assassination of civilian activists in the construction of the Hidroituango dam between 1998 and 2018 and the assassination of union leaders protesting working conditions in the construction of the Porce II dam in 1997 and 1998.

Through these two cases I present novel empirical contributions and show how overlapping patterns of violence allows elites to use conflict narratives to undermine civilian challengers and dismiss accusations relating violence to development. As Chenoweth, Perkoski, and Kang (Citation2017, 1962) observe, states and elites ‘rarely use repression in a vacuum’. Uncertainty around civilian victimisation led the private-public corporation Public Enterprises of Medellin (EPM), government officials, the military, and even judicial ruling by the Colombian court systems to frame these events –intentionally or not – as products of the territorial conflict dynamics without further investigation. Conflict provides such a compelling framework to understand violence that even parties without personal incentive to generate these narratives may reproduce them, such as academics or human rights organisations, particularly given the uncertainty surrounding the precise motivation behind attacks. These narratives may be challenged by the victims, but often such challenges bear no legal consequences or worse, appear to invite further repression.

Conflict, opportunity, and elite interests

War provides civilians the opportunity to take advantage of armed groups to falsely accuse other civilians of involvement with opposing groups to settle personal scores or advance personal interests (Barter Citation2016, 26; Bhatia Citation2021). Kalyvas terms this ‘malicious denunciation’ (2006, 338–339) which provides ‘the less powerful and the disadvantaged an opportunity to take out their spite’, to use ‘systems hungry for information’ for their own interests’ (Gellately Citation2001, 24; Clark Citation2014; Janssens Citation2021).

The elite inversion of Kalyvas’ ‘malicious denunciation’ can be deployed to silence or repress challenges to elite interests. Evidently if war offers opportunity to the less powerful, it offers ample opportunity for elites – a group of people ‘who have vastly disproportionate control over or access to a resource’ (Khan Citation2012, 362). The resources available to elites mean that these denunciations are not necessarily geared at ‘tricking’ one armed group to repress difficult civilians (activists, unionists, or un-cooperative land-owners) but rather can also obfuscate motives behind systematic civilian victimisation to broader audiences and avoid investigation even as targeted civilians are clear about who they fear criticising.

In this paper, I examine the elite inversion of this dynamic by focusing on how developmental elites respond to information scarcity and uncertainty. I use the term developmental elites, not merely economic elites, because I include both the private and public actors involved in funding and managing large-scale infrastructural roll-out, such as private contractors, public agencies, officials, and other government branches involved. Developmental elites may rely on colonial or entrepreneurial narratives that justify their interests and supress civilian opposition (Lima and Mafra Citation2023; Grajales Citation2020). Civil war not only facilitates material opportunities for elites to divest civilians from desired land in cases as diverse as Colombia, Indonesia, and Myanmar (Gutiérrez-Sanín and Vargas Reina Citation2016; Lund Citation2018; O’Connor Citation2011) or work with armed groups to capture resources such as cases in Central Africa (Berman et al. Citation2017; Patel Citation2016), but also a new narrative of justification.

Research has demonstrated that elites may have established agreements with armed groups built through mutual economic interests; counterinsurgent forces frequently target non-violent protestors as ‘extremists’ or insurgent’ to enforce the trajectory of elite development efforts (Dunlap Citation2019; Brock and Dunlap Citation2018; Grajales Citation2013). In the Philippines, for example, anti-dam activists were stigmatised as terrorist supporters and targeted by paramilitary actors (Delina Citation2020, 6). This stigmatisation happens when a person possesses or is believed to possess ‘some attribute or characteristic that conveys a social identity that is devalued in a particular social context’ (Crocker, Major, and Steele Citation1998, 505). It assigns blame to the victims for their supposed association to undesirable actors [i.e. armed groups] and reduces the need for investigation and accountability by state actors, similar to the ‘politics of naming’ of conflict actors (Bhatia Citation2005). Blaming the conflict, rather than development, for civilian victimisation draws useful ‘political frontiers between “insiders” and “outsiders”’ (Howarth, Norval, and Stavrakakis Citation2000, 4), that retains elites’ plausible deniability (Stephens Citation2017; Maassarani Citation2005).

The difficulty in investigating violence in ongoing conflict combined with the presence of armed groups in a territory offers a convenient discursive framing for civilian victimisation. This framing often becomes the dominating narrative as elites have better access to wider audiences through official statements, media, or even judicial rulings (Jäger and Maier Citation2015, 39). Conflict-affected regions like other informal or illicit spaces are often ‘subject to mischaracterizations (e.g. marginal, criminal, and chaotic) by powerful actors who stand to gain from certain narratives and thus strategically cultivate ambiguity’ that requires further investigation to challenge these dominating narratives (Dev et al. Citation2022, 666). In this paper I examine how elites capitalise on the uncertainty generated by armed conflict to advance these stigmatising narratives that undermine and discredit civilian opposition and the violence they face by shadowy actors.

Counterinsurgency and development in Colombia

In Colombia the link between private economic interests and the rise of paramilitary groups in the 1980s and 1990s has been well-established (Ballvé Citation2020, Citation2013; Grajales Citation2013, Citation2011), underscored by historic inequalities and weak property rights that enabled large-scale land appropriation (Kinosian Citation2012). Molano argues that civilian displacement in Colombia ‘is not an ‘effect’ of conflict but rather a weapon of war itself and a strategy of economic accumulation’ (2000, 42). The paramilitary violence against the Union Patriotica political party in the early 1990s was only in part a reaction to its association of the Armed Revolutionary Forces of Colombia (FARC), but also a systematic destruction of union leaders, civil rights activists, and left-wing politicians (Gomez-Suarez Citation2007). Indeed, statements by former president Alvaro Uribe on the ‘terrorist nature’ of anti-development activists delegitimsed their efforts and made them targets for violent attacks by the military and paramilitary groups (Chambers Citation2013, 126). Yet I argue that elites do not merely label undesirable civilians as terrorists, but rather capitalise on the very murkiness that conflict produces to attribute instances of civilian victimisation to local territorial competition.

There are few high-profile incidents that explicitly tie developmental interests to civilian victimisation. However, those that emerge reveal how elites instrumentalise not only conflict actors but conflict narratives. In 2020, Salvatore Mancuso, a former paramilitary commander, testified that he was sent by the Colombian state and its private contractors to supress dissent to the construction of the Urra dam in the department of Cordoba in 2001. In his testimony, he states that the targeting of the local Embera Indigenous people, especially the killing of leader Kimy Pernía Domicó, was to quash the opposition to the dam while disguising it as a counterinsurgent operation:

What happened to the Indigenous leader Kimy Pernía Domicó was a crime of the state. The excuses they were giving, because you remember that the State was censuring you and prohibiting you from entering the area freely, because they said you were supporting subversive armed groups in the area, and that when they were going to build the hydroelectric dam [Urrá], they started the systematic actions by the Colombian state intended to weaken you and end whatever effort to claim or realise your rights. (Florez Arias Citation2020)

Methods

This analysis revolves around two megadams (over $100 million each) built in Antioquia between 1995 and 2018. Both Hidroituango and Porce II were spearheaded by EPM and constructed in territories historically and currently affected by the Colombian civil war with the presence of multiple armed groups, including paramilitary groups, paramilitary successor groups such as the Clan del Golfo and Caparrapos, and the FARC, and National Liberation Army (ELN). Hidroituango was built on the site of some of the most violent paramilitary incursions of the 1990s, resulting in decades of fruitless investigations into links between then governor (later president) Alvaro Uribe and the counterinsurgent operations of the Bloque Minero of the Colombian United Self-Defence group (AUC). Porce II is less prolific but my own efforts in understanding its similar patterns of civilian displacement by paramilitary actors uncovered significant archival information on the suppression of union leadership during its construction. I do not take these as individual comparative cases given the overlap of timeframe and actors. Instead, these cases are representative of the different ways developmental elites take advantage of the fog of war to stigmatise and discredit civilian opposition to their interests.

This analysis draws on interviews collected with 15 community leaders, activists, and civilians, as well as government officials and functionaries from EPM. Interviews were carried out with informed oral consent of participants that all data should be kept anonymous and safely secured by the researcher as stipulated by the ethics approval granted by the University of Oxford. Citations only include the place and month of interview and a generalised description of their position to avoid identification. The case of Porce II builds on initial interviews with local leaders in the area, but the core of analysis examines eleven letters and attached material sent by the SINTRAPORCE union leaders to various offices in 1997. The letters were preserved by the Colombian government’s Virtual Archive of Human Rights and Historical Memory. The analysis, carried out between 2020 and 2022, also drew on additional publications by the National School of Syndicalists and contemporary news articles. This archival data was essential due to difficulty in tracking down first-hand testimony on the assassinations and events leading up to them. This archival data also contributes to understanding the ‘real-time’ uncertainty in how actors perceived and responded to the existing data at the time (Chenoweth, Perkoski, and Kang Citation2017, 1964).

The very uncertainty I assess in this paper poses a methodological challenge to researching violence. Conflict and civil war databases have issues in disaggregating potential conflict-related violence from other kinds, largely because of the difficulty in distinguishing between material and intellectual authors of such events (Eberwein and Chojnacki Citation2001). Armed groups with clear political ideologies can operate on multiple levels, either for political (i.e. counterinsurgency) or for economic (supressing challenges to developmental interests) objectives. Equally, the presence of uniformed combatants makes it relatively simple for others to pose as an established actor in the territory by using a uniform, badge, or announcing themselves as such.

Conflict environments therefore generate both uncertainty in data collection, and intentional efforts to mislead or obfuscate investigation (Chojnacki et al. Citation2012, 391). I therefore draw from Perrera’s Bermuda triangulation, which is not focused on ‘the verification of a single piece of information, but rather the uncovering of multiple narratives related to the initial information—each with their own additional details which lead to recursive processes of triangulation’ which ‘reveal important dynamics of conflict’ (Perera Citation2017, 54). In this paper, I make no claim about any specific elite’s complicity with the victimisation detailed below. Instead, I illustrate the empirical evidence surrounding instances of civilian victimisation, and the different narratives (elite and victims) employed to explain such events. I show that it is precisely the ambiguity that makes it easy for elites to frame every instance of victimisation as arising from territorial conflict disputes, despite credible justification for further investigation. This approach therefore incorporates the stories and silences – both in person or in archival gaps (Gonzalez-Ocantos and LaPorte Citation2019) – of counternarratives by victimised civilians to understand who they identify as responsible. Overlapping narratives of conflict and developmental violence are entangled, rather than discrete explanations for victimisation.

Findings

Counterinsurgency and Hidroituango

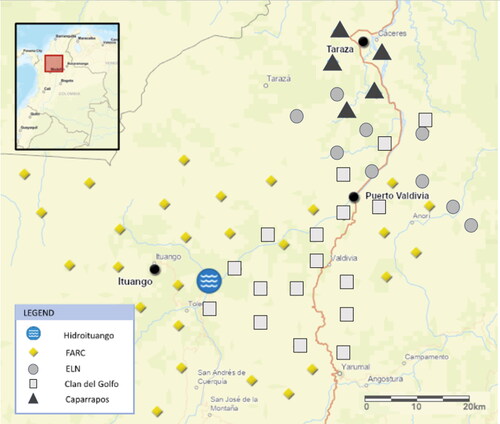

Thousands of civilians fled the municipality of Ituango and neighbouring municipalities in 1996 and 1997 when the Bloque Minero carried out some of the most notorious massacres in recent Colombian history in the veredas [sub-municipal units] of El Aro and the Granja. Between 1998 and 2008 a total of 62 additional massacres were recorded in the twelve municipalities in the area of Hidroituango’s influence, leading to a mass exodus of the population (Agencia Prensa Rural Citation2019). In her analysis of war-time displacement, Steele (Citation2017, 30) classifies the civilian flight from Ituango as displacement by paramilitary actors geared at counterinsurgency objectives, an assessment supported by the Interamerican Court for Human Rights in 2006 that ruled that displacement was part of ‘a counterinsurgent plan to terrorise the civilian population of the area to remove whatever support – real or imagined – in favour of the guerrilla’ (CIDH Citation2006, 2). While EPM denied any involvement in the displacement, they did justify the dam’s construction as part of a wider counterinsurgent effort; according to a former high-level official, Hidroituango was intended to ‘generate dynamics so that the project has a greater value [to the community] than the armed group [FARC]…[who] needed dynamics of exclusion to control’.Footnote1 The arrival of the dam was therefore a balm meant to turn the page on the history of ‘conflict and displacement in the region’ (EPM Citation2014, 22) ().

Figure 1. Hidroituango and armed group presence (2009–2018).

Source: Produced by author.

However, it is not as simple as distinguishing this mass displacement as counterinsurgent rather than economic (Steele Citation2017, 16). One local inhabitant of El Aro recounted that a paramilitary combatant had told him their objective in the territory: ‘they said that we were on land that would be used [for the dam]. When we refused to leave, that’s when they started shooting’ (Parkin Daniels and Ebus Citation2018).Footnote2 One activist recounts that this practice continued up to the dam’s construction started in 2008; armed actors who identified themselves as paramilitary knocked on the doors of civilians who had refused to sell their land to EPM and told them to leave.Footnote3

Accusations of links between elites and armed groups dogged the implementation of the dam, but never resulted in charges, must less convictions. In 2010 the official tender for the construction of the project, managed by EPM, was administered by the governor of Antioquia, Luis Alfredo Ramos. He awarded it to the firms of Camargo Correa and Conconcreto (CCC) Consortium. In 2011 the Colombian Supreme Court opened an investigation into alleged links Ramos had with paramilitary groups (El Espectador Citation2021), while in 2015, the Conconcreto company was also implicated in financing the AUC by former paramilitary commander Rodrigo Zapata (UNHCHR Citation2015). Official investigations in 2010 by the Prosecutor of the Peace and Justice Unit, Patricia Hernandez, observed that ‘parallel to the [hydroelectric] project’s evolution was the paramilitary advancement’, and in her judgement, the incursions were to pacify the territory for the hydroelectric project and the paramilitaries ‘did the dirty work’. No legal action came of the investigation, Hernandez was moved to another office, and eventually the investigation appeared abandoned (Noticias Caracol Citation2011; Torres Ramírez Citation2018, 436).

Yet civilians continued to challenge the dam’s implementation. By 2012, various communities displaced by the dam formed the Rios Vivos (Living River) movement and started organising protests and marches against the construction, citing issues of civilian displacement, environmental concerns, and the fact that the dam would flood an area thought to contain mass graves from the conflict (Lombana Citation2020). While EPM attempted to win community favour in promising to pave roads and build football pitches (EPM Citation2014), for many activists it was seen as patronising and insufficient, ‘behaving like they were the head of the family who helps expecting the children and wife to be grateful’.Footnote4

Therefore the protests continued, even as shadowy threats emerged in response. In March 2013, when Rios Vivos began organising marches in Ituango, armed fighters calling themselves the AUC targeted organisers of the movement (Sumapaz Citation2014, 66), leading to their displacement and eventually the assassination of multiple leaders, including Nelson Giraldo who was found dead in the Cauca river, shot multiple times and his throat slit (El Mundo Citation2013a). A short investigation was quickly abandoned, but the brutal manner of his death send a clear and intimidating message to Rios Vivos about returning to Ituango (Semana Citation2013). In 2013, teachers who protested the military taking a local school in Ituango as a base to protect the dam were sent threatening letters by individuals claiming to work with the CCC Consortium. The letter warned them they had 24 hours to leave Ituango because the teachers’ ‘social leadership’ was interfering with their ‘political efforts’ against terrorism in the region (Rios Vivos Citation2013). The case was never followed up or investigated.Footnote5

A new wave of repression emerged after problems with the dam caused the river to rise rapidly in April 2018, leading to a crisis downstream in Puerto Valdivia and Tarazá. The Association for Pan-miners of Northern Antioquia (ASOCBARENA) established a refugee camp in Ituango for those displaced by the rising water. Three of its leaders were killed between June and August 2018 (Verdad Abierta Citation2018); according to one leader, those killings were ‘to finish with that camp. It was receiving too much attention and the company did not want that much attention’.Footnote6 Eventually those in the camp abandoned it out fear of continued reprisal.Footnote7 A member of Rios Vivos also explained: ‘they would attack us because EPM would pay them to threaten us….They would say to us at Rios Vivos, we will give you only so much time, like 15 days to stop bothering about the project’.Footnote8

The elites involved with Hidroituango had a different narrative to explain the attacks over the years. Military leaders claimed that the FARC had coerced the local community to protest, making them vulnerable to opposition groups (El Mundo Citation2013b). A former EPM official insisted that ‘social confrontations [against the dam] were directed by the FARC’ because the complaints were anti-development and critical of the state, though he acknowledged that probably not all protestors were guerrilla.Footnote9 A project manager in EPM also claimed that though Rios Vivos had caused a lot of noise, the project was not opposed by the real local community, calling into question the true identity of the organisation’s members.Footnote10 When asked about the assassination of community leaders protesting the dam in Ituango, the Secretary of Government of Antioquia, Victoria Eugenia Ramirez said that ‘the prosecutor must resolve if these were defenders of human rights or people implicated in other circumstances’ (Hernández Citation2018), effectively questioning and unsubtly hinting that the victims had actually been involved with local conflict actors. By contrast, even civilians not involved with and critical of Rios Vivos dismissed the idea of guerrilla involvement due to the FARC’s lukewarm opposition to the dam despite public statements against it.Footnote11

State actors appeared to understand explicitly how conflict dynamics could frame civilian victimisation. A local leader with ASOCBARENA recounted a conversation overheard between two military officials in 2017 near one of the camps for miners displaced by the Hidroituango dam:

A major told another major that they should ‘fill us full of lead’ and then say it was the guerrillas. But the other major said no, we cannot shoot them because everyone knows the guerrillas don’t get involved with the miners.Footnote12

The language of the threats is also informative. A miner displaced in 2018 from Tarazá became involved with ASOCBARENA protesting against EPM and began to receive threats from unknown sources, who accused him and fellow leaders of being ‘informants for the guerrilla’.Footnote13 If this conflict language is meant to stigmatise victims, the victims have a different idea about who is ultimately responsible. One local activist bluntly described why civilians were afraid to challenge Hidroituango: ‘No-one wants to be opposed to [the dam] because EPM has a lot of power and they will kill them’.Footnote14

Stigmatisation of civilians reinforces the dominant narrative of violence in the region to broader audiences as a struggle between insurgents and counterinsurgents. Elites do not need to prove this: rather they rely on the incontrovertible presence of conflict actors in the area and the existing uncertainty shrouding specific acts of violence. To illustrate the point, one local civilian in Ituango accused Rios Vivos of being infiltrated by guerrillas and causing violence – in line with EPM’s narrative – but then later admitted that the group appeared under threat for fighting for the rights of the local communities. He paused, and observed that ‘one never knows if that [threat] is motivated by the subversion, or who is killing these leaders protesting Hidroituango. It’s all a bit dark who is the actor behind these assassinations’.Footnote15 Overlapping violences obscure actual responsibility, while developmental elites maintain a simpler narrative of insurgency and counterinsurgency to account for civilian victimisation in the territory.

Insurgent revenge and Sintraporce

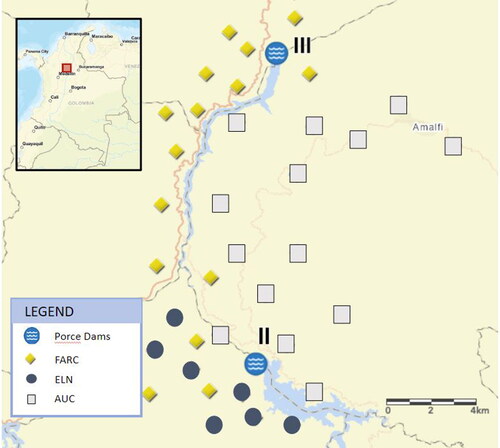

Mass displacements by counterinsurgent actors also occurred around the construction of Porce II (and later Porce III) dam by EPM and Conconcreto in northeastern Antioquia. The presence of the FARC’s 36th Front and the ELN Heroes and Martyrs of Anorí (Echandía Castilla Citation2013, 5) justified incursions by the paramilitary group Bloque Metro (Cívico Citation2009) and led to over 1045 forced displacements in the territories slated for dam construction in the Porce Canyon between 1990 and 2006 (CEV Citation2020, 88). Uncertainty pervaded the violence. According to local leaders, ‘one was not always sure who was directly responsible for the displacement. Different armed groups would come, and they would confront each other. Always in the areas of influence of the dams’.Footnote16 Another civilian leader explained that ‘suddenly, they were assassinating people and you did not know who, that was when people turned up who said they were working for EPM [to take a census], and that scared people because they were afraid that data would be used to kill them…as a result many people left’ (Cárdenas Delgado Citation2011) ().

Figure 2. Porce II and Porce III dams and armed group presence (1995–2010).

Source: Produced by author.

Violence associated with the dam did not end with displacement. The assassination of five leaders of SINTRAPORCE (Porce II workers union) Leadership Committee between 1997 and 1998 provides a different case for how developmental elites benefit from extralegal violence and ambiguity produced by armed conflict. On the 25th of January 1997 SINTRAPORCE raised a complaint on a series of violations of workers’ rights by Conconcreto, including issues of payment, safe working conditions, and the presence of medical support onsite (SINTRAPORCE Citation1997a, Citation1997b). The president of the union, Alberto Jaramillo, was assassinated on the 20th of March 1997 by hooded armed men wearing ELN armbands. On the 7th of October, the leadership of SINTRAPORCE received a pamphlet signed by the ELN explicitly threatening their lives and demanding that they leave the territory, which the leadership did, in Medellin by the 17th of October (SINTRAPORCE Citation1997h). The letter accuses the leadership of complicity with local paramilitary organisations and warns them ‘not to cry when we take you off the buses to apply the full weight of revolutionary justice’ (DDHH Citation1997).

Yet it remains unclear if the ELN were behind the threats, or whether these accusations were legitimate. While the new president Hector Castrillon was kidnapped and threatened in March after Jaramillo’s assassination by men dressed as ELN, he also later received threatening voice messages from paramilitary groups in the area (ENS Citation1998, 35). On the 24th of October 1997, after the letter was sent, the ELN stopped trucks taking workers to the Porce II campsite in a show of strength. Several workers took the opportunity to ask the combatants about the letter and attacks. The combatants denied sending the letter or responsibility for the assassination of Jaramillo (Juan Diego Citation1997), adding additional uncertainty about why a leftist armed group would openly intimidate union leaders for corruption one moment and deny it the next.

Further testimony by other workers indicated that the head of security onsite, Jaramillo Panesso, had warned the new union leadership after Alberto Jaramillo’s death that ‘they should not make a lot of problems for the company because there is a lot of danger with so many guerrilla organisations and paramilitary in the area’ (ENS Citation1998, 35). In 1998, members of the union testified that the ‘paramilitaries were using the camp as well as the company vehicles for their own work and that the head of security was an active supporter of Convivir’ (ENS Citation1998, 35–37). The SINTRAPORCE leadership at the time also suspected the company’s involvement and reported receiving various anonymous threatening calls to their house that included specific details about family members and contact numbers that the leadership believed was only accessible in the company employee records (SINTRAPORCE Citation1997h).

From the assassination of Jaramillo until October of 1997 tensions mounted as the new union leadership continued to publish detailed lists of workplace violation and demands (SINTRAPORCE Citation1997c, Citation1997d, Citation1997e, Citation1997f, Citation1997g). In October one of their leaders, Moises Caicedo, was forcibly removed from the worksite by the security guards (SINTRAPORCE Citation1997h). After the phone calls, harassment, and the pamphlet, the leadership fled to Medellin. There they met with officials from the Council of Medellin and agreed to travel back to the worksite on the 10th of November to inspect working conditions alongside government functionaries; the Committee even wrote to General Ospina of the 4th Brigade requesting security for Elkin Clavijo – the new president – and Alberto Niño, another union leader, to travel back to Anori on the 10th of November (SINTRAPORCE Citation1997j). In a chilling bit of irony, General Ospina would later be accused of supporting the paramilitary massacres in Ituango two weeks prior (Restrepo Citation2015).

The plan was to fly to the worksite from Medellin by helicopter with government functionaries but a few days before Clavijo and Niño were informed that there was not enough space and that they alone would need to return by bus (ENS Citation2000, 36).Footnote17 En route, other passengers reported that hooded armed men wearing ELN armbands stopped the bus and asked for Clavijo and Niño by name. Their bodies – showing signs of torture – reappeared by the road on the 13th of November (ENS Citation2000, 37–38; SINTRAPORCE Citation1997j). Several weeks later, another member of the displaced leadership, Luis Puerto, was assassinated during his lunch in Medellin by unknown assailants (ENS Citation2000, 38; SINTRAPORCE Citation1997i). The remaining members of the Committee moved to Bogota in December to receive protection from the national office of Human Rights in the Ministry of Interior (Ministerio del Interior Citation1997). However, financial pressure forced Moises Caicedo to return to Medellin in June 1998 to find work, where he was assassinated a few days later (ENS Citation2000, 38).

The perpetrators remain unknown, yet the end result appears to be in EPM and Conconcreto’s interests. In early 1998, after the murder of Clavijo and Niño, the Constitutional Court of Colombia ruled against SINTRAPORCE when members of the Committee tried to sue the Consortium, claiming their involvement in the threats made them responsible for paying for protection and compensation. The judge ruled that the companies had no obligation to pay since:

the Consortium of Porce II is not responsible for the acts of violence directed against the workers of SINTRAPORCE…indeed, the plaintiffs did not provide any evidence that would lead to presume the veracity of the accusations levelled against the company, much less, of its alleged complicity with the armed groups that sow terror in that area of the Antioquia department. In short, the cause of the violation of the rights of the guardians does not come from the action of the company but from dark forces, presumably of guerrilla origin [emphasis own]. (Tribunal Superior de Antioquia Citation1998)

In contrast, other union leaders were more critical of the ruling and its implications of who was behind the attack: Jorge Ortega, the president of the Single Confederation of Workers of Colombia (CUT) with whom SINTRAPORCE was affiliated, was concerned that it allowed corporations to leave workers unprotected in conflict areas, and particularly undermined the safety and position of union leadership (El Tiempo Citation1998). According to further testimony from other union members of SINTRAPORCE:

the Committee never believed that the pamphlet was sent by the ELN. They were more suspicious that the head of security was fishing in turbulent waters and he wanted to make the threat look like it came from the ELN. (ENS Citation1998, 35–37)

Conclusion

What is the value in taking such a granular view in tracing the repression of a handful of civilian activists and union leaders? I argue that these cases show how developmental elites use conflict narratives to delegitimise civilian challengers and dismiss their victimisation. While existing research has demonstrated the material links and shared incentives between elites and armed groups during war (Brosché Citation2014; Reina Citation2022; Ballvé Citation2013; Gutiérrez-Sanín Citation2019; Biberman Citation2018), here I argue that war also allows elites to invert ‘malicious denunciations’ and frame victims in the language of territorial conflict to broader audiences. This narrative is countered by the experiences and perceptions of victimised civilians, but the fog of war and the obvious presence of conflict actors makes claims of developmental violence more difficult to support.

When armed actors force civilians off land, or accuse activists or union leaders of supporting opposing armed groups, elites turn to easy narratives of armed conflict and territorial competition even while the victims themselves offered counter-narratives that implicate developmental elites. Paramilitaries such as the AUC have combined counter-insurgent efforts with broader targeting of activists and union leaders (Gomez-Suarez Citation2007; Chambers Citation2013) even without specific involvement by developmental elites. Yet elites advance a narrative that associates the victims with insurgency and conflict rather than their activism and opposition to the dam. Guerrilla groups may also have motivation for targeting civilian activists and union leaders: corruption, association with other armed groups, or theoretically even to silence activists that threaten a source of extortive income in the form of the dam. However, whether or not there are cases of guerrilla groups targeting civilians, the focus of this paper is precisely on how ambiguity around motive permits elites to advance a narrative that denies or dismisses any connection between the violence and development interests.

Violence by conflict actors combined with elite denial produces what Beban, in her analysis of violent landgrabs and state-making in Cambodia, refers to as the cyclical production of uncertainty (2021, 215). Civilian victimisation when there are political armed groups already present in a territory warrant less investigation by authorities who frame their existence as explanation enough. Only a handful of actual attacks and fatalities may occur that advance a developmental rather than conflict agenda, lost in the wider miasma of war-time violence and uncertainty, but these attacks send a clear message to civilian challengers of elite interests. The very nature of such dynamics shroud actions in secrecy so that few are unable to concretely identify the authorship of the abuses (Krahmann Citation2016, 1412), or unwilling to verbalise if they do know (Global Witness Citation2012, 8). The civilians who continue to press counternarratives do so bravely – and challenge elite’s dominating narrative – but there is little to no actual consequences or even investigation for the elites accused.

Peace processes can reveal the explanatory weaknesses of conflict narratives. Optimism about peace dividends began to fade not long after the historic 2016 peace accord with the FARC. While overall rates of violence dropped, the assassination of social leaders remained alarmingly high. The administration of President Ivan Duque attributed these killings to territorial competition between various remaining armed groups, including dissident FARC (Manetto Citation2020; Banchon Citation2020). Yet these killing are difficult to fit into old conflict narratives, even as government officials use the old playbook to lump the killings under ‘criminal disputes’, reporting the armed group associated with the attack rather than investigating their motives (COEuropa Citation2021; Manetto Citation2021). Grajales (Citation2020) argues that peace in Colombia presents a challenge to elites to adapt old frontier narratives that legitimised legally-dubious land acquisition in times of war as bold investments in dangerous and marginal territories. As one Colombian analyst observed, ‘there are no more easy narratives of guerrilla and paramilitaries [to explain assassinations]. Now you wonder who the social leaders are, who are the labour unionists, when are they linked to the FARC and when is this just an excuse?’Footnote18 The transition marks not merely a shift in violence, but also the dissolution of convenient narratives. These findings therefore add to the urgent need for peacebuilders to address not merely the political motives for national and local actors in armed conflict, but the economic interests that intersect with violence against civilians (Meger and Sachseder Citation2020).

The cases examined in this paper and the continued assassination of social leaders challenges us to consider how political armed conflict overlays one logic of violence over others, generating uncertainty about motivation and challenges to peace. The civilians displaced by the Hidroituango and Porce II dam call themselves victims of development rather than conflict (Lombana Citation2020, 7),Footnote19 inverting Steele’s assessment. Yet I argue the civilians displaced, threatened, or killed in these cases are victims of both. Both dams were unquestionably built in war-affected contexts with the presence of revolutionary armed groups and politically-motivated counterinsurgents. But to collapse all violence in these territories under the convenient aegis of conflict ignores how developmental elites may take advantage of both conflict’s extra-legal violence and its narrative to undermine and discredit civilian opposition to their interests. Though the study of these overlapping patterns generates incongruities and precludes one clear explanation for civilian repression, it is these very incongruities that scholars and policy-makers alike should take seriously in attempting to disentangle the violences of conflict and development.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Professor Abbey Steele and Professor Ana E Juncos for their insights and feedback on this manuscript. I am especially grateful to the research participants for their openness and generosity with their time and stories.

Disclosure statement

The author reports there are no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Clara Voyvodic

Dr Clara Voyvodic Casabó is Senior Research Fellow at the University of Bristol in the School of Sociology, Politics, and International Studies (SPAIS), as well as the Chair of the Peace, Conflict, and Violence Research Group at the School. She holds a PhD in International Relations from the University of Oxford, a Masters in Criminology from the University of Glasgow – for which she was a Carnegie Scholar – as well as a first-class MA in International Relations from the University of St Andrews. She has professional experience in the international humanitarian and security sector, including human rights protection, anti-corruption monitoring, and fugitive investigation. Her research focuses on the impact of armed conflict, organised crime, and development on local order and civilian victimisation. She also researchers qualitative methods and ethics in fieldwork in conflict and contentious areas.

Notes

1 Interview with former employee of EPM, Medellin – February 2019.

2 Also reported in interview with local teachers (2), Ituango – November 2018 and an interview with a local leader from Yarumal (3), a neighbouring municipality also in the area of the dam (Santa Rosas – December 2019).

3 Interview with local activist (4), Puerto Valdivia – April 2019.

4 Interview with activist (8) [not affiliated to Rios Vivos], Ituango – November 2018; interview with local activist [Rios Vivos] (4), Puerto Valdivia – April 2019.

5 Interview with local teachers (2), Ituango – November 2018.

6 Interview with local leader (5), Santa Rosas – December 2018.

7 Interview with local leader (5), Santa Rosas – December 2018; this was reiterated in an interview with a displaced panminer from Ituango (6), Medellin – December 2018.

8 Interview with local activist (4), Puerto Valdivia – April 2019.

9 Interview with former EPM official (1), Medellín – January 2019.

10 Interview with EPM project manager (7), Medellin – January 2019.

11 Many of the locals interviewed also claimed the FARC was more interested in extorting the dam constructors for money than blocking the project (Interview with local inhabitants of Ituango (2, 6, 8, 9), Ituango – November 2018. For more on this co-option see Voyvodic (Citation2022).

12 Interview with local leader (5), Santa Rosas – December 2018.

13 Interview with panminer (3), Medellin – December 2018.

14 Interview with local activist (4), Puerto Valdivia – April 2019.

15 Interview local inhabitant of Ituango (10), Ituango – November 2018.

16 Interview with local leader from Porce Canyon (11), Amalfi – November 2018. Reiterated in interviews with two other local leaders from Porce Canyon (12, 13), Amalfi – November 2018 and a fisherman in who had lived in Porce Canyon (14), Tarazá – December 2018.

17 The situation is eerily similar to that of Jesus Maria Valle, the famous human rights defender who brought national attention to the massacres of Ituango in 1997 and accused the Colombian government of complicity. Valle was offered a similar helicopter ride along with a group of officials to Ituango by Uribe (who later accused him publicly as an ‘enemy of the Armed Forces’) to show where the graves were and prove his claims. Last minute Valle was informed that the helicopter ride was full and that he would have to drive alone. Valle decided against it. He was killed a year later in his office in Medellin (Sánchez-Moreno Citation2018, 23).

18 Interview with national analyst (15), Bogota – September 2018.

19 Interview with local activist (8) Ituango – November 2018.

References

- Agencia Prensa Rural. 2019. 62 Masacres En Los 12 Municipios Donde Se Desarrolla Proyecto Hidroituango. La Nueva Prensa. https://lanuevaprensa.com.co/component/k2/62-masacres-en-los-12-municipios-donde-se-desarrolla-proyecto-hidroituango

- Ballvé, T. 2013. “Grassroots Masquerades: Development, Paramilitaries, and Land Laundering in Colombia.” Geoforum 50: 62–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2013.08.001.

- Ballvé, T. 2020. The Frontier Effect: State Formation and Violence in Colombia. Ithaca, USA: Cornell University Press.

- Banchon, M. 2020. “Líderes En Colombia: “Asesinar Sigue Saliendo Gratis”.” DW Times. https://www.dw.com/es/l%C3%ADderes-en-colombia-asesinar-sigue-saliendo-gratis/a-52144097

- Barter, S. 2016. Civilian Strategy in Civil War: Insights from Indonesia, Thailand, and the Philippines. New York, USA: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Beban, A. 2021. Unwritten Rule. Ithaca, USA: Cornell University Press.

- Berman, N., M. Couttenier, D. Rohner, and M. Thoenig. 2017. “This Mine Is Mine! How Minerals Fuel Conflicts in Africa.” American Economic Review 107 (6): 1564–1610. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20150774.

- Bhatia, J. 2021. “Unsettling the Peace? The Role of Illicit Economies in Peace Processes.” The International Journal on Drug Policy 89 (March): 103046. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2020.103046.

- Bhatia, M. V. 2005. “Fighting Words: Naming Terrorists, Bandits, Rebels and Other Violent Actors.” Third World Quarterly 26 (1): 5–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/0143659042000322874.

- Biberman, Y. 2018. “Self-Defense Militias, Death Squads, and State Outsourcing of Violence in India and Turkey.” Journal of Strategic Studies 41 (5): 751–781. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402390.2016.1202822.

- Brock, A., and A. Dunlap. 2018. “Normalising Corporate Counterinsurgency: Engineering Consent, Managing Resistance and Greening Destruction around the Hambach Coal Mine and Beyond.” Political Geography 62 (1): 33–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2017.09.018.

- Brosché, J. 2014. Masters of War: The Role of Elites in Sudan’s Communal Conflicts. Dissertation defended at Uppsala University.

- Cárdenas Delgado, O. 2011. “Porce IV: Las Comunidades o Los Macroproyectos.” Periferia Prensa. https://www.periferiaprensa.com/index.php/component/k2/item/715-porce-iv-las-comunidades-o-los-macroproyectos

- Carey, S. C., M. P. Colaresi, and N. J. Mitchell. 2015. “Governments, Informal Links to Militias, and Accountability.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 59 (5): 850–876. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002715576747.

- CEV. 2020. “San Roque: De La Doctrina Contrainsurgente al Extractivismo.” Comision para el Esclarecimiento de la Verdad, la Convivencia, y la no Repeticion. https://cjlibertad.org/comunicaciones/Informe%20San%20Roque%20De%20la%20Doctrina%20Contrainsusrgente%20al%20Extractivismo.%20Final.pdf

- Chambers, P. A. 2013. “The Ambiguities of Human Rights in Colombia: Reflections on a Moral Crisis.” Latin American Perspectives 40 (5): 118–137. https://doi.org/10.1177/0094582X1349212.

- Chenoweth, E., E. Perkoski, and S. Kang. 2017. “State Repression and Nonviolent Resistance.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 61 (9): 1950–1969. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002717721390.

- Chojnacki, S., C. Ickler, M. Spies, and J. Wiesel. 2012. “Event Data on Armed Conflict and Security: New Perspectives, Old Challenges, and Some Solutions.” International Interactions 38 (4): 382–401. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050629.2012.696981.

- CIDH. 2006. “Caso de Las Masacres de Ituango vs Colombia: Sentencia 1 de Julio de 2006.” Corte Interamericana de Derechos Humanos. https://www.corteidh.or.cr/docs/casos/articulos/seriec_148_esp.pdf

- Cívico, A. 2009. No Divulgar Hasta Que Los Implicados Estén Muertos: Las Guerras de “Doblecero”. Bogotá, Colombia: Intermedio.

- Clark, G. 2014. Everyday Violence in the Irish Civil War. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- COEuropa. 2021. “Organizaciones de DD.HH. Aseguran Que Iván Duque Busca Mostrar Cifras Reducidas de Homicidios de Líderes Sociales En El Exterior.” Coordinacion Colombia Europa Estados Unidos. https://coeuropa.org.co/organizaciones-de-dd-hh-cifras-reducidas-lideres/

- Crocker, J., B. Major, and C. Steele. 1998. “Social Stigma.” In The Handbook of Social Psychology, edited by D. Gilbert, S. Fiske, and G. Lindzey, 504–553. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- DDHH. 1997. “Carta Amenazadora Por Presupuesto ELN: Dirigido a Elkin Clavijo, Hector Castrillon, Moises Caicedo, Uriel Hernandez, Alfonso Nino.” Plataforma Colombiana de Derechos Humanos, Democracia, y Desarrollo. http://www.archivodelosddhh.gov.co/saia_release1/fondos/carpeta_digitalizacion/co_aminga_01/Caja%2023/Carpeta%202/217-221.pdf

- De la Calle, L. 2017. “Compliance vs. Constraints: A Theory of Rebel Targeting in Civil War.” Journal of Peace Research 54 (3): 427–441. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343316686823.

- Delina, L. L. 2020. “Indigenous Environmental Defenders and the Legacy of Macli-Ing Dulag: Anti-Dam Dissent, Assassinations, and Protests in the Making of Philippine Energyscape.” Energy Research & Social Science 65: 101463. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2020.101463.

- Dev, L., K. M. Miller, J. Lu, L. S. Withey, and T. Hruska. 2022. “Ambiguous Spaces, Empirical Traces: Accounting for Ignorance When Researching around the Illicit.” Progress in Human Geography 46 (2): 652–671. https://doi.org/10.1177/03091325211058898.

- Dunlap, A. 2019. ““Agro Sí, Mina NO!”: The Tía Maria Copper Mine, State Terrorism and Social War by Every Means in the Tambo Valley, Peru.” Political Geography 71 (May): 10–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2019.02.001.

- Eberwein, W.-D., and S. Chojnacki. 2001. “Scientific Necessity and Political Utility: A Comparison of Data on Violent Conflicts.” Discussion Paper. Berlin: Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung (WZB).

- Echandía, C., and G. Salas. 2008. Dinámica Espacial de Las Muertes Violentas En Colombia. Informe Vicepresidencia de La Republica. Bogotá: Observatorio del Programa Presidencia de Derechos Humanos.

- Echandía Castilla, C. 2013. “Auge y Declive Del Ejército de Liberación Nacional (ELN): Análisis de La Evolución Militar y Territorial de Cara a La Negociación.” Fundacion Ideas para la Paz. https://ideaspaz.org/publicaciones/investigaciones-analisis/2013-12/auge-y-declive-del-eln

- El Espectador. 2021. “Luis Alfredo Ramos: Un Caso a Punto de Definirse Tras Años de Demoras’. El Espectador: Redaccion Judicial. https://www.elespectador.com/noticias/judicial/luis-alfredo-ramos-un-caso-a-punto-de-definirse-tras-anos-de-demoras/

- El Mundo. 2013a. “Asesinan a Un Activista Colombiano Que Se Había Enfrentado a Una Hidroeléctrica.” Europa Press. https://www.elmundo.es/america/2013/09/26/colombia/1380197021.html

- El Mundo. 2013b. “Golpe a Red de Apoyo de Las Farc En Ituango.” El Mundo Seguridad. https://www.elmundo.com/portal/noticias/seguridad/golpe_a_red_de_apoyo__de_las_farc_en_ituango.php#.YCpJ4uDLeAx

- El Tiempo. 1998. “Amenazas En El Trabajo.” https://www.eltiempo.com/archivo/documento/MAM-791621

- ENS. 1998. “Cuaderno de Derechos Humanos No 6: Los Derechos de Los Trabajadores Colombianos En 1998.” Escuela Nacional de Sindical. https://www.ens.org.co/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Cuaderno-de-Derechos-Humanos-6-Los-derechos-humanos-de-los-trabajadores-colombianos-en-1998.pdf

- ENS. 2000. “Cuaderno de Derechos Humanos No 9: Galeria de Casos.” Escuela Nacional de Sindical. https://ens.org.co/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Cuaderno-de-Derechos-Humanos-No.-9-Mayo-2000-Asociacion-y-Contratacion-Colectiva-Galeria-de-Casos.pdf

- EPM. 2014. “La Voz Del Proyecto Ituango: El Beso Que Dio Vida a Un Nuevo Puente Sobre El Río Cauca.” Empresas Públicas de Medellín. https://cu.epm.com.co/Portals/institucional/publicaciones-impresas/la-voz-del-proyecto-ituango-edicion-39.pdf

- Florez Arias, J. M. 2020. “Confesión de Mancuso Sobre Kimy Pernía Remueve La Verdad Pendiente de Los Paras.” La Silla Vacia. https://lasillavacia.com/confesion-mancuso-sobre-kimy-pernia-remueve-verdad-pendiente-los-paras-79061

- Gellately, R. 2001. “Denunciation as a Subject of Historical Research.” Historical Social Research 26 (2/3): 16–29. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20757865.

- Global Witness. 2012. “A Hidden Crisis? Increase in Killings as Tensions Rise over Land and Forests.” Global Witness Briefing 19. London: Global Witness.

- Gomez-Suarez, A. 2007. “Perpetrator Blocs, Genocidal Mentalities and Geographies: The Destruction of the Union Patriotica in Colombia and Its Lessons for Genocide Studies.” Journal of Genocide Research 9 (4): 637–660. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623520701644440.

- Gonzalez-Ocantos, E., and J. LaPorte. 2019. “Process Tracing and the Problem of Missing Data.” Sociological Methods & Research 50 (3): 1407–1435. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124119826153.

- Grajales, J. 2011. “The Rifle and the Title: Paramilitary Violence, Land Grab and Land Control in Colombia.” Journal of Peasant Studies 38 (4): 771–792. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2011.607701.

- Grajales, J. 2013. “State Involvement, Land Grabbing and Counter‐Insurgency in Colombia.” Development and Change 44 (2): 211–232. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118688229.ch2.

- Grajales, J. 2020. “A Land Full of Opportunities? Agrarian Frontiers, Policy Narratives and the Political Economy of Peace in Colombia.” Third World Quarterly 41 (7): 1141–1160. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2020.1743173.

- Gutiérrez-Sanín, F. 2019. Clientelistic Warfare: Paramilitaries and the State in Colombia (1982-2007). Oxford: Peter Lang.

- Gutiérrez-Sanín, F., and J. Vargas Reina. 2016. El Despojo Paramilitar y Su Variación: Quiénes, Cómo, Por Qué. Bogotá, Colombia: Editorial Universidad del Rosario.

- Hernández, C. 2018. “Bajo Cauca Antioqueño, En Vilo Por Asesinatos de Líderes Sociales.” El Tiempo. https://www.eltiempo.com/colombia/medellin/asesinatos-de-lideres-sociales-en-el-bajo-cauca-antioqueno-en-la-ultima-semana-215574

- Howarth, D. R., A. J. Norval, and Y. Stavrakakis. 2000. Discourse Theory and Political Analysis: Identities, Hegemonies and Social Change. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press.

- Jäger, S., and F. Maier. 2015. “Theoretical and Methodological Aspects of Foucauldian Critical Discourse Analysis and Dispositive Analysis.” In Methods of Critical Discourse Analysis, edited by R. Wodak and M. Meyer, Vol. 2, 34–61. Milton Park, UK: Routledge.

- Janssens, J. F. 2021. ““It’s Not Gossip, It’s True”: Denunciation and Social Control during the Guatemalan Armed Conflict (1970–85).” Journal of Latin American Studies 53 (1): 107–132. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022216X20001029.

- Jaramillo, E. 2011. Kimy, Palabra y Espíritu de Un Río. Bogotá: Editorial Codice Ltda.

- Juan Diego, R. 1997. “Sera Que Quieren Acabar La Actividad Sindical?” El Colombiano. http://www.archivodelosddhh.gov.co/saia_release1/fondos/carpeta_digitalizacion/co_aminga_01/Caja%2023/Carpeta%202/217-221.pdf

- Kalyvas, S. N. 2006. The Logic of Violence in Civil War. Cambridge Studies in Comparative Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Khan, S. R. 2012. “The Sociology of Elites.” Annual Review of Sociology 38: 361–377. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-071811-145542.

- Kinosian, S. 2012. “Colombia to Indict 19 Palm Oil Companies for Forced Displacement.” Colombia News.

- Krahmann, E. 2016. “NATO Contracting in Afghanistan: The Problem of Principal–Agent Networks.” International Affairs 92 (6): 1401–1426. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2346.12753.

- Le Billon, P., and P. Lujala. 2020. “Environmental and Land Defenders: Global Patterns and Determinants of Repression.” Global Environmental Change 65: 102163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2020.102163.

- Leguizamón Castillo, Y. R. 2015. “Conflictos Ambientales y Movimientos Sociales: El Caso Del Movimiento Embera Katío En Respuesta a La Construcción de La Represa Urrá (1994-2008).” Memoria y Sociedad 19 (39): 94–105. https://doi.org/10.11144/Javeriana.mys19-39.cams.

- Lima, A. D. C. C. d., and F. L. N. Mafra. 2023. “Coloniality of Power and Social Control Strategies in Mining: An Analysis of MAM Activists’ Narratives.” Third World Quarterly 44 (2): 300–319. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2022.2144826.

- Lombana, E. 2020. “Proyecto Hidroituango: La Historia de Una Tragedia.” Revista Kavilando, Victimas del Desarrollo 12 (2): 582–587.

- Lund, C. 2018. “Predatory Peace. Dispossession at Aceh’s Oil Palm Frontier.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 45 (2): 431–452. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2017.1351434.

- Maassarani, T. F. 2005. “Four Counts of Corporate Complicity: Alternative Forms of Accomplice Liability under the Alien Tort Claims Act.” New York University Journal of International Law and Politics 38: 39–66.

- Manetto, F. 2020. “Iván Duque: “Mi Idea de Paz Con Legalidad No Está Atada al Antes o al Después Del Proceso Con Las FARC”.” El Pais.

- Manetto, F. 2021. “Colombia Vivanco: “Duque Dice Que En Colombia Hay Millones de Líderes Sociales y Sugiere Que Proteger a Todos Es Imposible”.” El Pais. https://elpais.com/internacional/2021-02-23/vivanco-duque-dice-que-en-colombia-hay-millones-de-lideres-sociales-y-sugiere-que-proteger-a-todos-es-imposible.html

- McNeish, J. A. 2018. “Resource Extraction and Conflict in Latin America.” Colombia Internacional 3 (93): 3–16. https://doi.org/10.7440/colombiaint93.2018.01.

- Meger, S., and J. Sachseder. 2020. “Militarized Peace: Understanding Post-Conflict Violence in the Wake of the Peace Deal in Colombia.” Globalizations 17 (6): 953–973. https://doi.org/10.1080/14747731.2020.1712765.

- Middeldorp, N., and P. Le Billon. 2019. “Deadly Environmental Governance: Authoritarianism, Eco-Populism, and the Repression of Environmental and Land Defenders.” Annals of the American Association of Geographers 109 (2): 324–337. https://doi.org/10.1080/24694452.2018.1530586.

- Ministerio del Interior. 1997. “Carta J: Carta Del Ministerio al Mayor Herriberto Herrera (DAS) Sobre Proteccion de SINTRAPORCE.” Unidad Administrativa Especial para los Derechos Humanos Direccion General. http://www.archivodelosddhh.gov.co/saia_release1/fondos/carpeta_digitalizacion/co_aminga_01/Caja%2023/Carpeta%202/212-213.pdf

- Molano, A. 2000. “Desterrados: Papeles de Cuestiones Internacionales.” Centro de Investigacion Para La Paz, Papeles de Cuestiones Internacionales 1 (70): 41–46.

- Noticias Caracol. 2011. “Investigan Relación Hidroituango y Paramilitares.” Caracol Radio. https://caracol.com.co/radio/2011/12/29/judicial/1325149140_599019.html

- O’Connor, J. 2011. “State Building, Infrastructure Development and Chinese Energy Projects in Myanmar.” Irasec’s Discussion Papers 10: 1–22.

- Olumba, E. E., B. U. Nwosu, F. N. Okpaleke, and R. C. Okoli. 2022. “Conceptualising Eco-Violence: Moving beyond the Multiple Labelling of Water and Agricultural Resource Conflicts in the Sahel.” Third World Quarterly 43 (9): 2075–2090. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2022.2083601.

- Parkin Daniels, J., and B. Ebus. 2018. “Colombians Who Once Fled War Now Forced to Run from Catastrophic Flooding.” The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/jun/12/colombia-river-cauca-breach-flooding-farc

- Patel, R. 2016. “How Did a Gold Rush in Eastern DRC Leave Life Unchanged for Its People?” International Business Times. https://www.ibtimes.co.uk/how-did-gold-rush-eastern-drc-leave-life-unchanged-people-1568875

- Perera, S. 2017. “Bermuda Triangulation: Embracing the Messiness of Researching in Conflict.” Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding 11 (1): 42–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/17502977.2016.1269528.

- Reina, J. V. 2022. “Coalitions for Land Grabbing in Wartime: State, Paramilitaries and Elites in Colombia.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 49 (2): 288–308. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2020.1835870.

- Reno, W. 2004. “Order and Commerce in Turbulent Areas: 19th Century Lessons, 21st Century Practice.” Third World Quarterly 25 (4): 607–625. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436590410001678889.

- Restrepo, J. D. 2015. “La Masacre de El Aro Mas Alla Que Alvaro Uribe.” UN HCHR. https://www.hchr.org.co/index.php/compilacion-de-noticias/72-columnas-de-opinion/7430-la-masacre-de-el-aro-mas-alla-de-alvaro-uribe

- Rios Vivos. 2013. “Sobre La Amenaza a Los Docentes Del Municipio de Ituango Antioquia.” Movimiento Vivos. https://riosvivoscolombia.org/sobre-la-amenaza-a-los-docentes-del-municipio-de-ituango-antioquia/

- Rodríguez Garavito, C. A., and N. Orduz Salinas. 2012. Adiós Río: La Disputa Por La Tierra, El Agua y Los Derechos Indígenas En Torno a La Represa de Urrá. Dejusticia. Bogotá: Centro de Estudios de Derecho, Justicia y Sociedad.

- Sánchez-Moreno, M. M. 2018. There Are No Dead Here: A Story of Murder and Denial in Colombia. New York, USA: Hachette.

- Semana. 2013. “Drama de Los Mineros En El Campus de Universidad de Antioquia.” https://www.semana.com/nacion/articulo/mineros-en-el-campus/358378-3/

- SINTRAPORCE. 1997a. “Carta A: Carta a Minsterio de Trabajo y Seguridad Social Antioquia de SINTRAPORCE 25 Enero 1997.” Plataforma Colombiana de Derechos Humanos, Democracia, y Desarrollo. http://www.archivodelosddhh.gov.co/saia_release1/fondos/carpeta_digitalizacion/co_aminga_01/Caja%2023/Carpeta%202/266-308.pdf

- SINTRAPORCE. 1997b. “Carta B: Carta a Jefe de Trabajo Consorcio Porce II 31 Enero 1997.” Plataforma Colombiana de Derechos Humanos, Democracia, y Desarrollo. http://www.archivodelosddhh.gov.co/saia_release1/fondos/carpeta_digitalizacion/co_aminga_01/Caja%2023/Carpeta%202/266-308.pdf

- SINTRAPORCE. 1997c. “Carta C: Carta de Denuncio a Departamento de Recursos Humanos Consorcio Porce II 6 Mayo 1997.” Plataforma Colombiana de Derechos Humanos, Democracia, y Desarrollo. http://www.archivodelosddhh.gov.co/saia_release1/fondos/carpeta_digitalizacion/co_aminga_01/Caja%2023/Carpeta%202/266-308.pdf

- SINTRAPORCE. 1997d. “Carta D: Carta a Minsterio de Trabajo y Seguridad Social Antioquia de SINTRAPORCE 6 Mayo 1997.” Plataforma Colombiana de Derechos Humanos, Democracia, y Desarrollo. http://www.archivodelosddhh.gov.co/saia_release1/fondos/carpeta_digitalizacion/co_aminga_01/Caja%2023/Carpeta%202/266-308.pdf

- SINTRAPORCE. 1997e. “Carta E: Carta a Minsterio de Trabajo y Seguridad Social Antioquia de SINTRAPORCE 23 Mayo 1997.” Plataforma Colombiana de Derechos Humanos, Democracia, y Desarrollo. http://www.archivodelosddhh.gov.co/saia_release1/fondos/carpeta_digitalizacion/co_aminga_01/Caja%2023/Carpeta%202/266-308.pdf

- SINTRAPORCE. 1997f. “Carta F: Carta a Minsterio de Trabajo y Seguridad Social Antioquia de SINTRAPORCE 29 Mayo 1997.” Plataforma Colombiana de Derechos Humanos, Democracia, y Desarrollo. http://www.archivodelosddhh.gov.co/saia_release1/fondos/carpeta_digitalizacion/co_aminga_01/Caja%2023/Carpeta%202/266-308.pdf

- SINTRAPORCE. 1997g. “Carta G: Carta a Minsterio de Trabajo y Seguridad Social Antioquia de SINTRAPORCE 30 Julio 1997.” Plataforma Colombiana de Derechos Humanos, Democracia, y Desarrollo. http://www.archivodelosddhh.gov.co/saia_release1/fondos/carpeta_digitalizacion/co_aminga_01/Caja%2023/Carpeta%202/266-308.pdf

- SINTRAPORCE. 1997h. “Carta H: Carta a La Minga Por Parte SINTRAPORCE Aclaracion de Caracter Urgente 17 Octubre 1997.” http://www.archivodelosddhh.gov.co/saia_release1/fondos/carpeta_digitalizacion/co_aminga_01/Caja%2023/Carpeta%202/266-308.pdf

- SINTRAPORCE. 1997i. “Declaracion Sobre El Asesinato de Luis Puerta 18 Diciembre 1997.” Plataforma Colombiana de Derechos Humanos, Democracia, y Desarrollo. http://www.archivodelosddhh.gov.co/saia_release1/fondos/carpeta_digitalizacion/co_aminga_01/Caja%2023/Carpeta%202/200-200.pdf

- SINTRAPORCE. 1997j. “Solicitud de Proteccion Del SINTRAPORCE al General Carlos Ospina Antes de Viajar El 10 Noviembre de Medellin a Amalfi.” Plataforma Colombiana de Derechos Humanos, Democracia, y Desarrollo. http://www.archivodelosddhh.gov.co/saia_release1/fondos/carpeta_digitalizacion/co_aminga_01/Caja%2023/Carpeta%202/14-14.pdf

- Stanton, J. 2015. “Regulating Militias: Governments, Militias, and Civilian Targeting in Civil War.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 59 (5): 899–923. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002715576751.

- Steele, A. 2017. Democracy and Displacement in Colombia’s Civil War. Ithaca, USA: Cornell University Press.

- Stephens, B. 2017. “The Amorality of Profit: Transnational Corporations and Human Rights.” In Human Rights and Corporations, edited by D. Kinley, 21–66. Milton Park, UK: Routledge.

- Sumapaz. 2014. Estado de Los Derechos Humanos En Antioquia 2014 : Entre El Sueño de La Paz y La Continuidad de La Guerra. Bogotá, Colombia: Coordinación Colombia Europa Estados Unidos.

- Tellez, J. F. 2022. “Land, Opportunism, and Displacement in Civil Wars: Evidence from Colombia.” American Political Science Review 116 (2): 403–418. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055421001003.

- Torres Ramírez, A. 2018. Colombia Nunca Más: Extractivismo—Graves Violaciones a Los Derechos Humanos. Caso Hidroituango, Una Lucha Por La Memoria y Contra La Impunidad. Medellín, Colombia: Corporación Jurídica Libertad.

- Tribunal Superior de Antioquia. 1998. “Accion de Tutela: De Parte de Elkin Clavijo y Otros Contra Consorcio Porce II (Sentencia T-278/98).” Corte Constitucional. https://www.corteconstitucional.gov.co/relatoria/1998/T-278-98.htm

- UNHCHR. 2015. “El Misterioso Frente Suroeste de Las Auc.” Oficina del Alto Comisionado de Derechos Humanos. https://www.hchr.org.co/index.php/compilacion-de-noticias/63-paramilitares-y-grupos-post-desmovilizacion/7004-el-misterioso-frente-suroeste-de-las-auc

- Voyvodic, C. 2022. “Contested Statebuilding? A Four-Part Framework of Infrastructure Development during Armed Conflict.” In The Social and Political Life of Latin American Infrastructures, 1st ed., 127–144. London, UK: University of London Press.

- Verdad Abierta. 2018. “Violencia e Hidroituango Mantienen En Zozobra a Comunidades Del Norte de Antioquia.” Verdad Abierta. https://verdadabierta.com/la-violencia-e-hidroituango-mantienen-zozobra-comunidades-del-norte-antioquia/

- Williamson, S. 2023. “Do Proxies Provide Plausible Deniability? Evidence from Experiments on Three Surveys.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 68 (2-3): 322–347. https://doi.org/10.1177/00220027231170562.