Abstract

This article explores the role of Alessandro Blasetti in arguing for, and promoting, the development of the Italian film industry before and after the Second World War. Though a prominent film director for more than thirty years, Blasetti was never considered an auteur: he had no distinct authorial style and not did he specialise in any particular genre. Unlike some postwar directors, he never positioned himself in opposition to producers but, on the contrary, worked closely with many of them, winning a reputation for reliability and professionalism. A supporter of Fascism until the later 1930s, he encouraged state involvement in the industry and was the first to use the Cinecittà studios, inaugurated in 1937, to their full potential. After the war, he mediated between opposing political forces to defend the interests of the Italian cinema as an industry and a ‘collective art’. He was responsible for creating several stars, including Gino Cervi and Sophia Loren. Drawing on the Blasetti archive, the article considers the range of the director’s activities, political links and his way of conceiving his role, immersed in rather than against the industry.

Alessandro Blasetti is paradoxically both one of the most significant and one of the least recognised of Italian film directors. Though he started out as a critic and intellectual and was the principal promoter of some key state cinema institutions, such as the Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia, the national film school, he would never enjoy the high status of some postwar art directors. The main reasons for this are twofold. First, he did not have a recognisable personal style in the way that many directors did. While defending the prerogatives of the director, he championed an idea of cinema as a ‘collective art’ which granted more recognition, though not co-authorship, to screenwriters, cinematographers, set designers, costume designers and so on. The second reason is that Blasetti’s activism was geared more to an idea of cinema as an industry than as a creative art. Thus, despite a clash with Stefano Pittaluga, the leading industrialist of cinema at the time of the birth of sound film, he understood that films were products as much as they were works of art. In the 1950s and after, when the Italian art film enjoyed high national and international status, this stance relegated him to the second rank. It was Fellini, Visconti and Antonioni who won prizes, not Blasetti. Yet, his contribution to Italian cinema is incontestable. Over the entire period between the 1920s and the 1960s, he made films in many different genres and pioneered a number of new, specifically Italian, currents, including the episode film (made up of several episodes by one or more directors) and the sensational documentary, the best known example of which is Mondo cane (Gualtiero Jacopetti, 1962). Fascinated by the technical and expressive possibilities of the medium, he was the first to experiment with some forms of spectacle and was an acknowledged master of crowd scenes.1 He was consistently involved with the promotion of national cinema and this saw him engage with the political sphere through both the Fascist and republican periods. At a time when there were few long-established or large-scale production companies of the type which characterised the industry in the United States or France,2 he was, it is fair to say, a director with something of the mentality and vision of a producer. Unlike some of his colleagues, he never disparaged producers in general or sought to present his concerns as distinct from theirs.

The aim of this article is to explore Blasetti’s contribution to the development of the Italian film industry through his critical writings and his engagement with policy issues, his collaborations with producers, his interest in genre and his commitment to spectacle, as well his role in the formation of stars and the promotion of his films. It may be said that his entire career was marked by the co-existence of two, not readily reconcilable, impulses. On the one hand, he was an innovator, who championed new techniques, who studied and took inspiration from international cinema. He was the only film-maker with the status and credibility to comment widely on matters of film policy and to have the ear of politicians on these questions. On the other hand, he was in some respects a conformist, an integrato (integrated intellectual), to borrow a term coined by Umberto Eco.3 He often made films on commission, responded to producer’s suggestions and provided contributions or supervision to the films of others. His practice as a director was intrinsically bound up with the development of an industry able to invest, to think big and to combine quality and commercial appeal. In a period of industrial fragility, Blasetti was a constant promoter and theorist of Italian cinema’s industrial vocation and development. However, at times, he was also an integrato in a political sense. Though he distanced himself from Fascism’s political priorities long before its fall, and his commitment to the national industry over-rode possible controversy about his earlier professional and political engagement with Mussolini’s regime, he never meditated on the fact that his own artisanal approach to cinema sat well with film policy under the regime. Industrial conformism and political conformism were never entirely separable, either before or after the war.

In order to analyse the particular contribution that Blasetti made to Italian cinema, drawing out both innovations and relations with producers and the political sphere, reference will be made to the remarkably rich archive of personal papers, production materials from his films, correspondence and photographs that he left behind. The article is divided into four sections, each of which tackles an area in which the director’s interventions were significant. The first deals with issues of the industrial development of cinema, while the second examines his vision of the role of the director within an industrial context. The third section considers the genre system and the director’s contributions to its elaboration. Finally, attention will be paid to Blasetti’s view of actors and stars.

Blasetti and the Italian film industry: from crisis to state involvement

Blasetti is credited with having brought Italian cinema into the cultural sphere. He claimed that there were no film reviews in Roman newspapers before he created the first rubric of this type for L’Impero in 1924.4 It is also often argued that the term regista (director) was coined with him in mind following release of his first film, Sole (Sun) in 1929.5 The sense of Blasetti as a founding father of Italian cinema and as ‘a man of cinema in the widest sense’ is one that gave him a prominent status the 1930s and which he maintained until the late 1950s.6 It is central to his posthumous reputation as the architect of ‘a type of cinema that confidently asserted the interdependency of art and industry’.7 Though a number of directors, particularly those who would make their debuts in the period following World War Two, began as critics, few combined attention to aesthetic questions with sustained engagement with matters of industrial policy. Indeed, the young critics of the 1940s were ideologically averse to the very idea of cinema as an industry.8 Blasetti, who was born in Rome in 1900, belonged to a generation whose first experience of cinema occurred in the period of the Italian industry’s greatest crisis. After the First World War, a once florid production sector all but ceased to exist and the American studios asserted their hegemony in the Italian market. The over-riding task was to find a way to revive Italian cinema. To this end, Blasetti began a campaign of activism that saw him develop the remit of the critic beyond judgement of the single film. He founded no fewer than three film periodicals and wrote extensively on the way to promote production with a distinctive national character. His writings display knowledge of international cinema and familiarity with the specific problems of Italian cinema, justifying descriptions of him as ‘an intellectual who was not detached from issues of art, industry and technique’.9

Blasetti’s articles of the mid 1920s reflect his belief that the decline of Italian cinema had been the result of poor leadership. ‘Before it was destroyed by those who knowingly discredited it, our film industry was the third most important industrial activity in the country’, he asserted in support of his conviction that it could once more be a stable and profitable activity.10 The sheer scale of the American industry and of its operations in Italy was proof of the global significance of the market for film. Italy’s men of cinema were ‘poor administrators’ who were ‘incompetent technically’, people who were ‘more inclined to turn a sound stage into a tea room than a productive workshop’.11 The first aim was to find better qualified men who would invest sensibly in film production, supported by the banks. He exhorted businessmen to show a sense of patriotism and use their resources to create infrastructures and facilitate production.12 However, their role extended beyond this. In contrast to the image of the producer as being interested only in the bottom line, he asserted, in a text on the ideal organisation of a production company, that the director of production should have ‘the most polyhedral artistic sensibility in the whole establishment’.

He must be ‘the most cultured man in the whole company…, He must know, better than anyone., where and how to look for the ideas and the men who…are capable of producing ideas. He must know the minimum and maximum potential of the means and the men of which the company disposes. He must have the most exact grasp of the present and future demands of the audience. This should form part of a clear vision of future developments that should, in turn, be based on his own personal plan, method of work and scale of operation.13

This did not mean that Blasetti thought the industry should be financed by the state. ‘The convinced return of private capital’ was what was needed and not ‘the construction of a cinema paid for by the state – a horrible speculation that would serve to transfer taxpayers’ money into the safes of single savers while it would surely fail to achieve – due to its misconceived nature - the very aims that should bring it about’.16 The only valid economic motor was that which would give rise to ‘a healthy and autonomous industrial function’. However, for the industry to prosper, protection against foreign imports, reciprocal agreements with foreign countries and investment in production facilities were all needed.17 The role of the government, in its capacity as ‘propulsive force of every national activity’, was to create the conditions for this to occur.

Blasetti was critical of the way the film industry had been run. The experience of the Unione Cinematografica Italiana (UCI), which had absorbed several small production companies under one umbrella in an effort to consolidate an industry in crisis, had not been a positive one; by forsaking quality for quantity, it had ended up making matters worse.18 It was against this background, and at a time of government disinterest in cinema, that, together with other young intellectuals, Blasetti began agitating in favour of the national industry. In the magazines L’Impero, Lo schermo, Il mondo e lo schermo and especially Cinematografo, the future director advanced his idea of cinema as a ‘unitary complex of art-entertainment-industry-politics’.19 The last-mentioned magazine featured articles of various types, from theoretical pieces to practical treatments of economic questions. A close eye was kept on American and European experiences and a dialogue opened with Italian professionals working abroad.20 Augusto Genina, a pioneer writer, director and producer who had made many films between 1914 and 1920, was among these. After he moved to Berlin in 1926, he conducted an intense correspondence with the young Blasetti about the workings of the German film industry,21 which the latter took the opportunity to publish in his magazine Cinematografo in 1927. The title of the article, ‘Why the German Film Industry is in Full Development: Circumstances, Organisation, Nationalistic Spirit’ offers a clear synthesis of what Blasetti thought was the recipe to follow to revive Italian cinema.

Given his attention to industry, it is curious that the one serious entrepreneur in the sector, Stefano Pittaluga, should have been a particular target of his criticism.22 Pittaluga was the great hope of Italian cinema, the man who, after he transferred his activity from Turin to Rome in 1929, contributed more than anyone to the revival of the industry. He created a company equal to the challenges facing Italian cinema at the end of the 1920s, which was organised around the need to provide exhibitors with a regular supply of films that attracted audiences.23 As such, he deserved credit for promoting production in Italy and giving it a future. Blasetti had initially opposed sound cinema, in which Pittaluga had invested, seeing it as a tool of American domination, and was highly critical of the entertainment fare the producer was making.24 Instead he argued for a ‘policy of authors’ which would privilege creative talents. Though it is sometimes said that ‘the only “trade” he never undertook was that of producer’,25 Blasetti’s first film Sole (Sun, 1929) was made by a cooperative named Augustus that he created with the financial backing of sympathetic aristocrats and, in an anticipation of the much-later phenomenon of crowd-funding, by asking the readers of the magazine Cinematografo to each contribute one hundred Lire. This was an outgrowth of his belief that Italian cinema could develop a quality profile on the basis of low-cost films ().

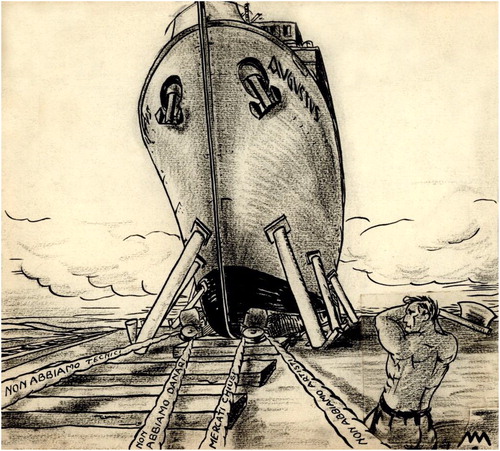

Figure 1. Cartoon by the set designer Gastone Medin about the birth of the Augustus production company, created by Blasetti to finance his first film, Sole (Sun, 1929). The writings on the ropes read ‘We have no technicians’, ‘We have no money’. ‘Closed markets’, ‘We have no artists’.

Archivio Alessandro Blasetti, Cineteca di Bologna.

Sole presented sufficient elements of interest for Pittaluga to approach Blasetti and draw him into the company stable.26 In the first instance, the producer made concessions, granting him creative freedom. However, after his first sound film, Resurrectio (Resurrection, 1931) proved a flop, the humbled director was more amenable to suggestions. The idea of a film with the variety star Ettore Petrolini was Pittaluga’s, but the conception of the film Nerone (Nero, 1930) was Blasetti’s. The scheme of filming the performer in a theatrical context, complete with audience, and opting for a compilation of sketches featuring his best-known characters, was a creative response to the commission. With this film, he began a long series of fruitful collaborations with producers.

Blasetti’s engagement with the cause of national cinema occurred in a particular context in which Mussolini’s regime was seeking to reinforce Italy as an economic, cultural and political power. His outlook situated him on the same wavelength as Fascism. He aligned himself with the regime and was instrumental in alerting government officials, who initially were not interested in cinema, to the economic and cultural significance of the medium. He was acutely aware of the range of developments that were required if Italy was once more to have a film industry of which it could be proud: intelligent industrialists, a supportive government, significant on-going investment, regulation of imports, technical expertise, talented and properly-trained creative and artistic personnel. Thus, he championed the cause of protectionism and of the creation of infrastructures. It was his idea to establish the first cinema school, which came to fruition in 1932 with the creation of an acting course held at the Saint Cecilia conservatory. In 1934, the state, personified by the leading official in the sector, Luigi Freddi, took over this initiative and founded the Centro Sperimentale per la Cinematografia in 1932, before establishing Cinecittà in 1937. Blasetti became the key director of the period, the one who most embodied the qualitative development of Italian cinema and the effort to create a national production that was dignified and inspiring while sensitive to the public’s demand for entertainment.

Blasetti directed a number of films which signalled his alignment with Fascism. He aspired to interpret, in terms of both the form and content of films, the climate of social and cultural reinvigoration which Fascism championed, by means of a combination of the lessons of such masters as Lang, Dreyer, Vertov, Eisenstein and D.W. Griffith with a realist aesthetic that was rooted in the national artistic tradition. From cinema’s greats, Blasetti learned to shoot outdoors, use complex camera movements, alternating longer shots with close-ups, and to employ editing to impose a precise rhythm on a film. Vecchia guardia (Old Guard), the film he made in 1934 extolling the activities of the violent Fascist squads of the early 1920s, which won Mussolini’s approval but not that of all officials, signalled his political affiliation, as did his Risorgimento film 1860 (1933), which included a final sequence of young blackshirts marching past approving, but now elderly, members of Garibaldi’s army.27 However, his output was by no means restricted to the political. The period between 1930 and 1942 was the most productive of his long career, during which he made fifteen films, many of the them for the Cines company, which was brought into the public sector two years after Pittaluga’s untimely death in 1931. He became known especially for his historical costume dramas Ettore Fieramosca (1938), adapted from a popular literary classic, Un’avventura di Salvator Rosa (An Adventure of Salvator Rosa, 1940), and La corona di ferro (The Iron Crown, 1941), all sumptuously staged studio films on a grand scale. Despite his position as the most ‘official’ director of the period, he had numerous battles with Freddi, the Director General of Cinematography and, later, director of both Cinecittà and Cines. These were battles that took place within the heterogeneous field of Fascist cinema (Freddi dubbed them ‘authentic’ in his memoirs),28 in which political and commercial considerations did not always combine easily.

Blasetti’s identification with Fascism grew weaker over time, with the Spanish Civil War and Mussolini’s friendship with Hitler shaking his convictions.29 While some projects were suggested to him by Freddi, other projects were taken on at moments when he was out of favour. He claimed to have made the light-weight romantic comedy La contessa di Parma (The Countess of Parma, 1937) after his naval film Aldebaran (1935) was found to be banal.30 Others were made in order to avoid propaganda commissions. His last film of the period, Nessuno torna indietro (No Turning Back, 1942), an adaptation of Alba de Cespedes’ novel which featured an all-female main cast, was taken on to excuse himself from Quelli di Bir el-Gobi, an African-set war film which was not in the end made. This alternation of official projects and commercial films was made possible by the existence of both a state-led production company and a range of private companies and producers who grew in number and financial strength following the withdrawal of the American companies from the Italian market in 1939.

From his earliest films, there had always been an element of realism in Blasetti’s work. Sole, Terra madre (Mother Earth, 1931), 1860, Vecchia guardia and other films were largely shot in the open air, as was Quattro passi tra le nuvole (Four Steps in the Clouds, 1942), a comedy with a ruralist theme that contrasted urban inauthenticity with the integrity of village life. His interest was in landscape, in the time-honoured traditions of rural Italy, and in the possibility of restoring these to the centre of a culture that was also embracing the modernity of which cinema itself, as a modern urban medium, was a part. Although this current in his output was, at the outset at least, entirely Fascist in orientation, some examples of it, notably Quattro passi tra le nuvole, were later seen as precursors of postwar neorealism. Blasetti’s detachment from officialdom assisted him in re-emerging as a champion of Italian cinema in the postwar period, when realism took on a different political connotation. Only a handful of directors were subjected to sanction for their Fascist associations and Blasetti was not among them.31 The film Un giorno nella vita (A Day in the Life, 1946), which explored the tragic consequences of an encounter between a group of partisans and nuns who allow them to take refuge in their convent, saw him establish plausible anti-fascist credentials.

Blasetti’s record of favouring an active role of the state was not something that worked in his favour in the immediate postwar years. All protectionist legislation was abolished in 1945 at the insistence of the Americans, who saw it as a fascistic invention, and there was reluctance on the part of the Christian Democrat-led government to restore it in any way. However, the severe crisis which befell the industry in 1947–49 as a consequence of the huge influx of foreign films produced a united front of all sectors in demanding government action to safeguard a national industry and protect employment. As a prominent exponent of cinema’s creative wing, with a record of support for free enterprise, Blasetti was well-placed to articulate the concerns both of those who wished to develop the realist current in postwar cinema and those who wanted to see the government backing growth of the industry. Taking care to avoid any further overt political alignment, he contributed to publications on both sides of the Cold War divide and used his authority to address the government directly on questions regarding the film industry and its crises. For Adriano Aprà, only Rossellini enjoyed a similar capacity to address all parties on such matters,32 though the director of Roma città aperta (Rome Open City, 1945) did not have the same close relationship with producers. The articles Blasetti wrote for a variety of publications in the 1950s testify to an ability to think about cinema in industrial terms and to demand serious attention to its problems from government.33 Though the period was florid one, it was still beset with periodic crises. The integration of the artistic with the commercial was expressed in a conviction that directors and actors should not isolate themselves from cinema as a business. Rather, he urged a ‘system of production in which the financial risk is shared between the various contributors to a film’s creation’.34 Indeed, directing an appeal in 1958 to Giulio Andreotti, the minister most responsible for the re-establishment of measures of support and control over cinema, he qualified himself as someone who understood that it was important for everyone to share in the risks of the industry.35

Cinema as a collective art

Though his initial activity as a critic is associated with what was termed ‘the policy of authors’, and the distinctive personal imprint he gave to Sole led to his being labelled the first Italian regista, in Blasetti’s view, cinema - even and perhaps especially when invested with cultural ambition - was a collective art that entailed the collaboration of a variety of people and competences. His conception of the director’s role was explicitly articulated and reflected a specific view that entailed a practice and an image that were different from that of the director as sole auteur. In his view, the director was ‘first among equals’. He advanced this most persuasively in relation to his own films. For the Risorgimento drama 1860, he renounced personal merits for the film and instead claimed that it was ‘the success above all of a method and of a category’.36 Even from a narrative point of view, 1860 saw Blasetti reject the sort of emblematic heroism that had been attributed to the protagonists of Sole, Terra madre and Palio in favour of the primacy of the group, a shift of direction that would be completed with Vecchia guardia. Adriano Aprà has suggested that Blasetti was seeking to set out an ‘American’ idea of the director’s role that was inspired by the studio system.37 Though he did not work in the USA or for a studio, ‘he seems to have given up speaking in the first person through cinema in order to give space to concerns of method and category, in order to offer a model of cinema that has as its partner the industry and the mass audience rather than political power and the “engaged” spectator’.38 It has been argued that this stance was due to a series of factors including his disagreements with Freddi and his growing detachment from Fascism. However, this is to reduce his attitude to conjunctural factors whereas the engagement with industry dated back to his rapprochement with Pittaluga. As would be seen in the postwar years, recognition of the roles of government and of industry was a constant that only varied according to the strength of the industry at given moments.

At various points, Blasetti acknowledged the contributions of screen writers, costume designers, cinematographers and actors. He asserted that his work as a director ‘was greatly facilitated by that collaborative network that is at the basis of every film’.39 The writer was the figure he stressed most; 40 the text or screenplay was a vital component of the success of a film and its elaboration required significant creative input.41 The encounter with the writer Cesare Zavattini, Vittorio De Sica’s close collaborator on Sciuscià (1946) and Ladri di biciclette (Bicycle Thieves, 1948), was an important one for him, that marked his detachment from an epic register in favour of a tragi-comic style that was more suited to the depiction of the ordinary lower-middle-class Italian. In time, Blasetti argued, film scripts would come to have the same status as theatrical texts. The lack of recognition accorded writers, he would argue in 1959, was a distortion that derived from the cult of the director. It meant that ‘the valid brains who have chosen the profession of screenwriter as opposed to that of director can be counted on the fingers of two hands’.42

In 1960, he argued that ‘cinema is a collective art, that is an art that is the product of a complex, organic and harmonious, of various creative inputs which must all be harmonised, blended and unified by one force which is direction’.43 ‘The author of a film therefore is the complex of artists who, honestly encountering each other on the plane of a creative collaboration, each offer their own capacity and inclination among those indispensable, all geared to the realisation of a cinematic work. Only one person is responsible if the film is artistically unsuccessful: the director. Those who share proportionately in the merits are all those who, with the director, have contributed to a film’.44

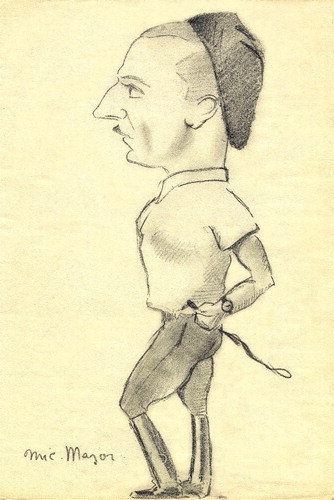

At the same time, Blasetti’s image was anything but humble. Much has been written about his authoritative image, his reputation as a director who adopted a position of commander, or even dictator, of the set. This image is one that attracted negative comment as early as 1932.45 The appellative of ‘director in boots’ was taken, the director later claimed, to mean ‘comedian, clown, fool, as well as dirty, ruffian, rough and ready, bossy, idiotic etc.’ ().46 He even claimed that the leading Fascist cinema official, Luigi Freddi, ever suspicious of unorthodoxy, saw them, as ‘a sign, if not of crypto-communism then of proletarian demogoguery’.47 His custom of sometimes wearing workers’ overalls on set completed this image. Yet it served him sufficiently under the regime, when it matched the authoritarianism that prevailed in all sectors of decision-making. For Fabio Andreazza, the wearing of boots contributed to the director’s ‘posture’ or self-image. Regardless of the various pragmatic explanations he advanced, the choice was a symbolic act that signalled an identification with the ‘revolutionary force of Fascism in the cinematic field’. ‘By wearing these boots’, Andreazza argues, Blasetti ‘exhibited his need for the so-called “revolution” of Fascism in order to make his contribution to his professional field: that of cinema’.48 They communicated vigour, decisiveness and perhaps even virility. However, it became a source of embarrassment requiring justification in the postwar years, when he was not keen to ‘pass for a director-despot’.49 Blasetti explained his choice of clothing as purely practical in an effort to distance himself from the resulting image, even treating it with a certain playfulness. It was with a degree of self-irony that he accepted to play himself on screen in Bellissima (Luchino Visconti, 1952; see ), in which he wore his overalls but no boots, though he would be hugely irritated by the director’s decision to mark his entry with the sounds of the ‘Charlatan’s Theme’ from Donizetti’s opera L’elisir d’amore.50 Blasetti never sought to play the role of ‘maestro’, to ‘protect’ younger directors or to set himself up as the founder of a cinematic current, as he had written to Visconti at the time of the latter’s debut, 51 but he was protective of his own dignity as a director. As he saw it, there was no inconsistency between the authoritative figure he cut on set and his insistence on the collective nature of the cinematic art. The set, in his view, was the place in which the director genuinely took sole control of the process of film-making, which was not the case either in the preparatory phases or in post-production or the management of the presentation and distribution of a film. In fact, Blasetti objected forcefully when the editor of Cinema nuovo, Guido Aristarco, accused him of wanting to downgrade the director. ‘It is clear that in any valid film it must always be him who holds the rudder, because he must know where to pilot the boat and because every boat must have a single pilot’. But ‘he must also know how to deliver a miracle of humility and firmness, of patience and understanding, of faith in himself as well as in others – from which only the sum of the contributions and the efforts of all will result in a work that is complete and unitary’.52

Figure 2. Caricature of Alessandro Blasetti, ‘the director in boots’ by Michele Majorana (c. 1930–1935). Archivio Alessandro Blasetti, Cineteca di Bologna.

Figure 3. Blasetti (at centre, with microphone, wearing trademark overalls), the elder statesman of the postwar years, playing the director in Bellissima (Luchino Visconti, 1952) (screenshot).

Even in the case of an art film, he asserted that ‘it will only be mistaken, and destructive, that the paternity of this art film is attributed solely to [the director]. Cinema is not painting or sculpture or music or literature; it does not have the unity of problems that characterise the arts born before it and which, by the way, all contribute to form it. …It cannot be achieved by the creative faculties of a single man even if a single man must in the end sum them up and unify them’.53 ‘Cinema is a collective art. It needs other poets beyond the director’.54 He insisted on this point, in opposition to the auteurist school, arguing that Visconti, ‘a director recognised as an artist’, was aided by Zeffirelli and Rosi, Fellini by Flaiano and Pinelli, just as he himself had been by Zavattini, Renato Castellani and Mario Soldati.55 ‘Antonioni, for example, is by no means alone; he has his collaborators, who are those who make up Antonioni, who is a product of a way of thinking, of reasoning. So, it is not as if he is alone’.56

Producers and genres

Blasetti did not hesitate to indicate good and bad practices by producers. He was especially content with his experience working on the eve of war on the blockbuster Un’avventura di Salvator Rosa, which was produced by a new company, Stella film, founded by Andrea De Robilant (a writer and producer also active in the immediate postwar years) and Augusto Turati (who would cease his activity in 1942). The company was run ‘by men who really know what they want and why they want it’.57 He was given adequate time for preparation that allowed him to achieve the appropriate climate. ‘For this, full recognition is due to my producer who stands as an example for all who in Italy today are engaged in financing a film’.58 The director of production also lent sympathetic support. ‘His merit lies in never having made me feel the need to renounce things that were vitally important for my job as director and to have kept control, without me even being aware of it, of the anything that might have damaged the project financially. By this, I do not mean that I was given complete freedom to spend and expand but, on the contrary, that I was helped and at the same time supervised, without my getting wind of it’.59

Blasetti had his own approach, but he was not identified with a sole genre, in the way that, say, Mario Camerini or Carmine Gallone were. His most significant contributions occurred in relation to two currents that were internal to Fascist culture. The first was ruralism, an anti-modernist strand commonly identified with – but not reducible to - the ‘Strapaese’ literary movement, which saw the countryside as the true repository of Italian values. Sole, about the reclamation of the Pontine marshes, was the first of a series which included Terra madre (Mother Earth, 1931), La tavola dei poveri (The Table of the Poor, 1932) and, in part, 1860. In these films, the rural theme was tackled in anti-bourgeois key, in line with Fascist policy which invested heavily in land reclamation in order to bolster the rural economy and reinforce an ideological identification with the countryside. The second was the historical costume drama. These took different forms. While Ettore Fieramosca and Un’avventura di Salvator Rosa, broadly conformed to the Fascist preference for films centred on heroic figures from national history, La corona di ferro and La cena delle beffe (The Jester’s Supper, 1942) did not. They sat far less easily with the war-time preoccupations of the regime than had the emphasis in earlier films on the organic unity of the Italian people and the land. In fact, in order to highlight his detachment from the regime, in the postwar years, he would often cite the negative reaction that the pacifistic message of La corona di ferro received from the Nazi propaganda minister Goebbels.60

For Orio Caldiron, Blasetti’s ‘singular artisanal ability’ consisted of ‘the chameleon-like ability to place himself at the service of the film, of every film, with a profound sense of cinematic rhythm and orchestration of expressive means, valorising to the maximum, in a conception of cinema as collective art, founded on the close collaboration of different elements, the support of writers an professional actors’.61 In terms of genres, there was a desire to innovate, to explore the expressive possibilities of cinema. This meant that he did not shy away from ‘big’ films, large-scale productions which exploited to the full the facilities of Cinecittà like La corona di ferro in the pre-war period or the Biblical epic Fabiola (1949) after the war. But he also made documentaries, light comedies and dramas (Quattro passi tra le nuvole and Nessuno torna indietro in 1942 and Prima comunione in 1950) and two films that could be considered typical 1930s entertainment fare, La contessa di Parma and Retroscena. Different considerations informed his decision to make each film. Blasetti was sensitive to a producer’s need to ensure the commercial success of a film. Asked years later about the reason La contessa di Parma, which was set in the fashion world, also included a football element, he responded that it offered a further ‘guarantee’ on account of the sport’s popularity. Quattro passi tra le nuvole owed much to Giuseppe Amato, director of production for Cines and one who, Blasetti would later state, recognised and appreciated his versatility.62

While, in the postwar years, Blasetti argued in favour of neorealism as an authentic innovation, he was never counted as belonging to the most progressive part of the film community. His personal history meant that, in the division between the critical-political wing of Italian cinema and the industrial wing – which would become marked after passage of the Andreotti law of 1949 – he was more aligned with the latter. Blasetti praised the Excelsa company, and its head Angelo Mosco, for its courage in producing Roma città aperta (Rome Open City, 1945).63 He would personally ally himself with Salvo D’Angelo, producer for the Vatican-sponsored Orbis company and then founder of Universalia. D’Angelo was a man who, like Blasetti himself, liked to think big and no postwar film was bigger than Fabiola. In the 1930s, Blasetti had won a reputation for his sense of the spectacular and his ability to stage large-scale scenes involving many extras. He was an obvious choice to direct a blockbuster that, more than any other film, signalled the industrial ambitions of Italian cinema. Coming after the victory of the Vatican-backed Christian Democrats in the 1948 election, it was seen as by some as a political statement and a tribute to the Church in view of the Holy Year of 1950. Blasetti was aware that the Lit. 700 m cost of the film caused uneasiness and that some saw it as monstrous and in poor taste. ‘The “big film” is always a “massive machine” that justifies the greatest diffidence and the most natural aversion for the implicit threat of suffocation that its proportions entail’, he admitted.64 He defended his film by arguing for its industrial rather than political significance:

‘Fabiola was presented on our screens at a particularly critical time for Italian cinema. It was the time of the polemics against exhibitors who were even accused, more or less explicitly, of sabotage. Well, the exhibitors competed to show Fabiola. In Rome, it was shown in five cinemas and offers from three further cinemas were declined. This was a benefit for Italian film production; it entailed a break in the situation. In fact, after Fabiola, other Italian films had successes superior to other films of equal value shown earlier. Second point: Fabiola established the industrial and financial bases for that Italian-French collaboration that the two governments would develop and confirm with their very important accords. Third point: Fabiola restored to Italy the industrial pride of the sale sight unseen (a scatola chiusa). No fewer than thirty foreign countries bought it before it was completed, on the basis of the names that were involved with it, the scale of the project and the photographs of the production. Fourth point: the Centro Sperimentale, a most necessary institution for the refreshments of personnel, had been left in very poor state by the war. The production of Fabiola brought its large studio back into action, it refurbished and enlarged its small one and it added to these two a third one almost as big as the big one. …In addition, Cinecittà, from being a refugee camp, has returned to being – thanks to the money and the needs of Fabiola – the largest and most important complex in Europe to the point that it was able to host, immediately afterwards, an American production. Fifth point: Fabiola gave work to thousands of people at a moment of crisis in film production’.65

The basic message of the film, he claimed, was one of peace and tolerance that ran through all his films. To him, it was a source of pride that his film opened the way to the restoration of Italian cinema’s fortunes and preceded the filming in the Cinecittà studios of an even larger production, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer’s Quo Vadis. The film can be seen as a metaphor of the deep division that the watershed 1948 election revealed and exacerbated between a Catholic centre-right and the forces of the left. By tackling the theme of the end of the persecution of early Christianity and reconciliation between people of different faiths, Fabiola ‘advanced a discourse of social pacification’, recalled Veniero Colasanti, who was the costume and set designer of the film. In addition, it became the prototype which inspired various later ancient Roman blockbusters made by Hollywood studios. Indeed, according to Colasanti, ‘the costumes and the furnishings of the film were bought as a job lot by Sam Zimbalist, the MGM producer who was preparing Quo Vadis.66

The last film Blasetti made with D’Angelo was the first film to be made under the Italian-French co-production accords. Prima comunione (Father’s Dilemma, 1950) was produced by the newly-created Universalia company. Completely different in scale and significance to Fabiola, it was a minor comedy that descended from Quattro passi tra le nuvole, both films originating from an idea by Zavattini. Starring Aldo Fabrizi and Gaby Morlay, the story centred on a shopkeeper’s hapless efforts to ensure the success of his daughter’s first communion. The film heralded the revival of the type of Roman comedy in which Fabrizi had starred in the 1940s, prior to his dramatic triumph in Roma città aperta. In 1950, it reinforced the turn to comedy that would contribute to the re-conquest of the domestic market. Though traces of neorealism remained in the ever-present voiceover and the concern with realistic detail, the film’s exuberance suggested a change of tone. With a number of French cast members and a strongly Roman feel, the film combined the aspects of the international and the provincial, which would both prove vital to the fortunes of Italian cinema.

The film underlined Blasetti’s versatility and commended him to the new producers who were piloting the expansion of Italian cinema at home and abroad. No-one would ever suggest that Blasetti was a routine director, but he was a reliable pair of hands, a director with the experience and inventiveness to ensure that bread and butter comedies were delivered in the best possible way. He was also a director who was engaged with thinking out new formulas for an industry that was growing rapidly.67 His most significant invention was the episode film, which would soon become a staple of the Italian film industry. Typically composed of a number of short films by different directors, sometimes but not always on a common theme, films constructed on this model would turn out to be an important formula for Italian cinema in the 1950s and 1970s. By tying up directors and stars for a limited period, they allowed for the use of the time lags between larger projects or could be shot during idle moments on the former. The resulting works did not always have the stellar appeal of the multi-protagonist film, as pioneered by MGM’s Grand Hotel (Edmund Goulding, 1932), but they provided a useful addition to the armoury of Italian producers and were often box office hits. Though the six episodes of Rossellini’s Paisà (1946) constituted a precursor, Blasetti pioneered the genre with his film Altri tempi (Olden Times, 1952), which was composed of episodes taken from Italian literature, all directed by himself.68 A commercial success, the film inspired many others which together formed a current that, over time, involved the whole of Italian cinema, from high to low, overcoming a division that was enshrined in the practices of many production companies. By means of this film, it has been argued, Blasetti ‘offered a proposal of production methodology to the industry…without stretching the overall possibilities and the requirements of Italian cinema’.69 ‘The episode film, in fact, served to test out new narrative formulas and to develop the techniques of the screenplay, to deploy actors and preserve the element of spectacle without spending too much money’. The episode film perhaps never quite became the fully-fledged genre that Blasetti hoped (it was more of a filone, or transitory current), but it provided an extraordinarily useful resource in the repertoire of Italian cinema.

One significant offshoot of it was the sensationalist documentary, a sub-genre that prospered in the early 1960s and which saw Jacopetti’s Mondo cane emerge as the most notorious example. Blasetti pioneered the current with his Europa di notte (Europe by Night, 1959), which offered a compilation of night club acts and titillating erotica. The film was a type of episode film with documentary (or fake documentary) footage taking the place of scripted episodes of a fictional nature. Touristic in inspiration, the film was referred to by Blasetti as an investigation into the lives of those who worked out of hours to entertain others, a sort of filmed journalistic project. He argued that the film was a risky enterprise that, when he first proposed it, was greeted with perplexity on account of the lack of precedents: ‘A film without stars? A film without a plot? Without even episodes? A documentary consisting purely and simply of entertainers and their audiences?’70 His producers imposed certain constraints on him, but at the same time it was, he stated, due to their ‘exceptional courage’ that he was able to conclude the film in the face of mounting objections from the production sector and distributors in both Italy and France.71 It has recently been shown by Raffaele De Berti how the complex production history and promotional strategies adopted for this film reflected efforts to grasp and cater to the tastes of the new middle class that was taking shape during the period of rapid economic development.72 The success of the film marked a new step in Blasetti’s commercial career but did little to enhance a reputation in the cultural field which was by this point considerably reduced.

Towards a national star system

According to Gianfranco Gori, in the postwar years, Blasetti worked in two main directions: towards the stabilisation of the genre system and towards the birth of a national star system.73 He defended neorealism as a significant moment in national cinema but, despite having himself experimented with nonprofessional actors during the 1930s, he never embraced neorealism’s practice of casting non-professionals in leading roles. It is significant that Un giorno nella vita was made with a cast of professionals, as was Prima comunione, another film which, the director acknowledged, could have dispensed with them. In this, Blasetti acted in a manner that was consistent with the commitment he had displayed to the industrial development of Italian cinema. In the course of the 1930s, he had contributed to the creation of some of the most significant national stars including Amedeo Nazzari, Alida Valli, Clara Calamai, Maria Denis, Luisa Ferida and Gino Cervi. Indeed, he had imposed some – notably Ferida – whose qualities were not immediately obvious to distributors.74

Writing in 1944, he acknowledged that the Americans had taken over the idea of film stardom and made it into something of their own. The ‘divo’ of early cinema became the star – ‘stars that the economic power of the American market allows to be sold at the price of light bulbs’.75 Douglas Fairbanks and Priscilla Dean, armed with sex appeal, marched across Europe ‘bolstered by the inexhaustible resources of the dollar’.76 Fairbanks was not a great actor but he had physical beauty and personality. In an industrial cinema, Blasetti argued, ‘the actor must be subordinated to the artistic discipline of the director, but he cannot be ignored or under-valued or reduced to the second rank’.77 ‘It is on him that the public fixes its eyes; it is in him that the public must believe; it is the appeal of his personality that is required to draw millions of spectators into the auditorium with the aim of taking them into the imaginary world of the poet’.78 ‘Actors’, he later wrote, ‘have to be professionals to succeed in overcoming the distance between the screen and the heart of the spectator, to be able to consciously express the words of the writer and interpret consciously the intentions of the director’.79

In the postwar years, Blasetti remained a reference point for the actors he worked with. The correspondence files of the Blasetti Archive contain numerous letters from actors who were no longer receiving offers of work. In 1947, Germana Paolieri told him she was ‘in perfect shape’ and offered to send him ‘some recent photographs’ to prove it.80 Greta Gonda acknowledged that she was no longer in demand but begged for a ‘small part’.81 To the latter, Blasetti wrote that he would not make ‘vague expressions and illusory promises’; instead he frankly told her that ‘the implacable requirements of distributors (and age)’ made it impossible for him to keep former collaborators in consideration.82 However, he also received letters from young hopefuls who saw in him the great director who had made many careers.83

The two most significant stars of the postwar years were Anna Magnani and Silvana Mangano. The overnight success of the latter in Giuseppe De Santis’ Riso amaro (Bitter Rice, 1949) opened the way to a steady flow of young actresses from beauty pageants to the cinema. However, the phenomenon did not emerge fully or acquire a label until Gina Lollobrigida, who had been runner-up in the 1947 Miss Italia contest, was cast as an adulterous murderess in his episode film Altri tempi (in the episode ‘The trial of Frine’).84 At the end of her trial, the woman is acquitted following a passionate speech from her lawyer which hinges entirely on her beauty: if a mentally sub-normal person cannot be held criminally responsible, then why should a physically exceptional one, he argues. The film turned the term maggiorata fisica into label and made Lollobrigida’s breasts into a key feature of her stardom and of the whole postwar star system. The following year, the director observed that another actress, Goliarda Sapienza, ‘lacked the Lollobrigidean elements necessary for success in the postwar period’.85 Il processo di Frine also revived the screen fortunes of Vittorio De Sica, a matinee idol in the 1930s before he turned his hand, with great acclaim, to film directing. Blasetti deployed the ‘humorous body’ of De Sica as a foil for the ‘sexual body’ of Lollobrigida, staging each with artful expertise.86

Blasetti also directed Sophia Loren in two films he produced for the Documento Film company, which initiated her highly successful screen pairing with Marcello Mastroianni. The two films Peccato che sia una canaglia (Too Bad She’s Bad, 1955), which also featured De Sica, and La fortuna di essere donna (Lucky to be a Woman, 1956) were engaging comedies with strong story lines. In the first Loren is a thief who seeks to con a taxi driver out of his earnings. In the second, Mastroianni is a photographer whose casual snap of Loren leads to her coming into contact with the world of cinema. It was a source of disappointment to Blasetti that Loren subsequently attributed her success principally to De Sica, who directed her in the episode of L’oro di Napoli (The Gold of Naples, 1954) which brought to the fore her Neapolitan origins. ‘It matters greatly to me that you recognise that the first director to declare -urbis et orbis – and, before others, to you yourself – that you would have become a real actress was me’, he wrote to her in 1957.87 ‘As for Peccato che sia una canaglia’, he continued, ‘I think I can state that it was your first complete and utterly brilliant affirmation as an actress of temperament and intelligence, aside from your glamour and personal sexiness’. In these letters, it was evident that Blasetti felt he was no longer a central figure in Italian cinema. He wanted her public endorsement to show that he was still important. It would be helpful, he declared to her, ‘if the “great” Sophia Loren were to rejuvenate my old name by according it the tribute of the intuition that it is due. Hearing you speak solely of L’oro di Napoli – notwithstanding my admiration for De Sica and the great performances you gave him, which however are not superior to those of Canaglia and Fortuna – causes me great distress’. He was not to find satisfaction in this quest. As Loren’s career headed towards prestigious national and international productions, she developed a personal narrative that highlighted the contributions of De Sica and the producer Ponti over others. But, whether acknowledged or not, Blasetti helped forge her screen persona and played a part in her emergence as one of postwar Italy’s most emblematic stars.

Conclusion

Alessandro Blasetti was a key figure in Italian cinema for more than forty years. The publication of two collections of his writings in the early 1980s stood as testimony to the regard with which he was viewed.88 As a critic, activist, teacher, director and innovator, he was a vital contributor to the revival of cinema in the 1930s, its development in the 1940s and its affirmation in the 1950s and 1960s. At a time when there were few serious production companies, he promoted the cause of the national industry, sought the engagement of government, and worked to develop the quality of commercial cinema. It was this commitment to cinema as a spectacle and as mass entertainment that distinguished him from other intellectual directors who began their careers as critics and saw themselves as artists who stood above industry. A believer in the collective nature of the creative process in cinema, he did not renounce the prerogatives of the director while seeking due credit for writers, costume designers and other skilled practitioners. Blasetti himself was sometimes described as an artisan, on account of his interest in technique and effect over aesthetics. His eclecticism, which led him to work with many genres, saw his standing decline in an age in which the distinctions between the different levels of cinema became enshrined in the strategies of production companies and in which critics focussed mainly on prestige films.

It is appropriate, in a context in which production studies has become a recognised current of film history, that Blasetti should be re-evaluated. The only impediment to a recognition of his role lies in the controversial issue of his relationship with Fascism. Addressing this matter, he would seek to argue that his films, though they lacked a personal aesthetic, were unified by a pacifist thread. This led him to assert that the medieval fantasy La corona di ferro ‘anticipated, with the impulse of our most honest sentiments, the basic theme of neorealism: “No” (one would say today) to oppression, violence and war’.89 He even argued, stretching credibility, that Vecchia guardia, his controversial film about the provincial origins of Fascism, won admiration from all sides on account of its portrayal of the boy Mario, whose tragic death has the effect of calming social and political tensions.90 Blasetti deserves credit for not having sought to conceal or explain away his support for Fascism or to renege the films he made at that time. His progressive detachment from Mussolini’s regime and the fact that a number of his films, most famously Quattro passi tra le nuvole, were seen having anticipated neorealism, allowed him to enter the postwar world with his credibility intact. However, his insistence on the continuity of his work, and indeed of his engagement with matters of concern to the industry contrasted with the dominant narrative of a watershed. ‘Through Blasetti, there would be a tendency to furnish a unitary, harmonious, pacified image of Italian cinema’, one prominent critic has argued.91 This reflected a certain reality, but it was a view that led him, for example, to defend retrospectively Luigi Freddi, the Fascist film chief with whom he had in fact repeatedly argued.92

Blasetti pressed the cause of Italian cinema with producers as he did with politicians. He was an ally of both, though by no means an acritical one. Indeed, he often castigated those who lacked the qualities of imagination and intelligence he believed people dealing with a business-like cinema should have. But he never sought to set up an opposition between art and commerce and he never indulged in the sort of anecdotal disparaging of producers of some postwar art directors. He was ready to place his talents and skills at the service of the industry and many of his films were conceived and realised in close collaboration with producers. When he claimed that he had no ‘dreams in the drawer’, that he had always been able to make the films he wished, he was not suggesting that he had enjoyed complete creative freedom so much as stating that his projects had always been conceived with industry and the public in mind. This does not mean that he was a hack director, of which there were many in Italy, but rather that he understood the needs and functions of an industry whose growth and development he had consistently encouraged.

Acknowledgements

Research for this article was conducted as part of the AHRC project on ‘Producers and Production Practices in the History of Italian Cinema’. The authors thank Mara Blasetti for her help in understanding aspects of her father’s career and the Cineteca di Bologna for access to the Blasetti archive.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Stephen Gundle

Stephen Gundle is Professor of Film and Television Studies at the University of Warwick. He is the author of several books on Italian cinema and society, including most recently Death and the Dolce Vita (Canongate 2011), Mussolini’s Dream Factory: Film Stardom in Fascist Italy (Berghahn, 2013) and Fame amid the Ruins: Italian Film Stardom in the Age of Neorealism (Berghahn, 2020). Between 2016 and 2019, he was Principal Investigator on the AHRC project ‘Producers and Production Practices in the History of Italian Cinema’.

Michela Zegna

Michela Zegna is curator of paper archives at the Cineteca di Bologna. For five years she worked on the cataloguing and promotion of the Charles Chaplin archive. In more recent times she has been responsible for the Alessandro and Mara Blasetti archives, as well as those dedicated to Giuditta Rissone and Vittorio De Sica and others. From 2016, she coordinated the cataloguing and digitisation of the Franco Cristaldi archive for the Cineteca di Bologna with the sponsorship and collaboration of the AHRC project on ‘Producers and Production Practices in the history of Italian Cinema’.

Notes

1 For example, he shot the crowd scenes for Mino Monicelli’s La grande guerra (The Great War, 1959) at the request of Dino De Laurentiis and refused to be paid for this work. See Archivio Alessandro Blasetti, Cineteca di Bologna (henceforth AAB-CdB), CRS 17, fasc. 0486, sottofasc. 13, Letter to Blasetti from Dino De Laurentiis, August 21, 1959.

2 On the production context of the period, see M. Nicoli, The Rise and Fall of the Italian Film Industry (London: Routledge, 2017), parts 2 and 3.

3 In his 1964 book Apocalittici e integrati (Milan: Bompiani), Umberto Eco divided the intellectuals into two categories in terms of their responses to modernization: the ‘apocalittici’ were those who railed against it, while the ‘integrati’ were those who found an accommodation in relation to the opportunities it brought.

4 Blasetti testimony in F. Savio, ed., Cinecittà anni trenta (Rome: Bulzoni, 1979), 106.

5 Anon. ‘Per lui fu coniata la parola “regista”’, Il Resto del Carlino, February 3, 1987, ix.

6 W. Veltroni, untitled preface to Comune di Roma, ed., Alessandro Blasetti: Il mestiere del cinema (Rome: Gangemi, 2002), page unnumbered.

7 A. Aprà, ‘Blasetti regista italiano’ in A. Blasetti, Scritti sul cinema, ed. A. Aprà (Venice: Marsilio, 1982), 7.

8 On this aversion, see A. Abruzzese, ‘Per una nuova definizione del rapporto politica-cultura’, in Il neorealismo cinematografico italiano, ed. L. Miccichè (Venice: Marsilio, 1975).

9 Aprà, ‘Blasetti regista italiano’, 8.

10 A. Blasetti, ‘Lettera aperta ai banchieri d’Italia’ (1926), in Blasetti, Scritti sul cinema, 98.

11 Ibid., 99.

12 A. Blasetti, ‘Un’ora di osservatorio dalla nostra trincea’ (1927), in Blasetti, Scritti sul cinema, 115.

13 A. Blasetti, ‘Come nasce un film’ (1931–32), in Blasetti, Il cinema che ho vissuto, ed. F. Prono (Bari: Dedalo, 1982), 170–71.

14 Ibid., 171.

15 Ibid., 171.

16 A. Blasetti, ‘Un’ora di osservatorio dalla nostra trincea’, 115.

17 A. Blasetti, ‘Lettera aperta ai banchieri d’Italia’, 99.

18 A. Blasetti, ‘Cinema italiano ieri’ (1950), in Blasetti, Scritti sul cinema, 195. See also, Blasetti testimony in Savio, Cinecittà anni trenta, 108–9.

19 See Comune di Roma, Alessandro Blasetti, 19.

20 In an interview by G. L. Rondi, published in Il Tempo, July 3, 1975 and cited in L. Verdone, I film di Alessandro Blasetti (Rome: Gremese, 1989), 36–7, the director stressed that he had not seen any Russian films before he made Sole. The films that most influenced him were Vidor’s The Big Parade and Lang’s Die Niebelungen, films ‘in which the hero and heroism, myth and the masses, dominate’.

21 Between February 1927 and September 1928, Genina wrote seven letters to Blasetti in which he recounted frankly his experience of working in Berlin. The correspondence is preserved in AAB-CdB, busta CRS 01, fasc. 0433. Some extracts were published in an article that appeared in Cinefilia Ritrovata: https://www.cinefiliaritrovata.it/cinema-ritrovato-2017-augusto-genina-a-berlino/

22 Blasetti testimony in Savio, Cinecitta anni trenta, 110–11.

23 A. Blasetti, ‘Non incognite: Responsabilità’ (1931), in Blasetti, Scritti sul cinema, 129–30.

24 Aprà, ‘Blasetti regista italiano’, 14–15.

25 Ibid., 7.

26 F. Andreazza, ‘Director in Boots: The Posture of Alessandro Blasetti’, L’avventura, no. 1 (2016): 21–38. Blasetti testimony in Savio, Cinecittà anni trenta, 115–16.

27 Blasetti testimony in Savio, Cinecittà anni trenta, 131–33.

28 Blasetti would later refer to the ‘papacy’ of Freddi on account of his dogmatism and political orthodoxy. See A. Blasetti, ‘La marcia su Hesperia’ (1956), in Blasetti, Il cinema che ho vissuto, 32.

29 Luigi Freddi, head of the Direzione generale della cinematografia created by the regime to control cinema production, recalled, in his memoirs Il cinema (Rome: L’arpa, 1949): ‘My duty would have been to reject the film, also to reaffirm a principle, insofar as the regime, in my view, had no need for revivalism of that sort, which could easily have provoked damaging reactions. I did not ban the film; however, had censorship worked according to my criteria at the outset, that film would not have been made’.

30 Blasetti testimony in Savio, Cinecittà anni trenta, 135.

31 Augusto Genina was one who was subjected to sanction. See D. Forgacs and S. Gundle, Mass Culture and Italian Society from Fascism to the Cold War (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2007), 219–20.

32 Aprà, ‘Blasetti regista italiano’, 44.

33 Exemplary in this respect is the article ‘Il cinema dopo Fanfani’ (1951), in Blasetti, Scritti sul cinema, 210–13, in which the possible transfer of the cinema brief from the prime minister’s office to the Ministry of Industry is discussed.

34 A. Blasetti, ‘Cinematografo: barca e timone’ (1958), in Blasetti, Scritti sul cinema, 244.

35 Ibid., 244.

36 A. Blasetti, ‘Ancora del “Salvator Rosa”’ (1940), in Blasetti, Scritti sul cinema, 285.

37 A. Blasetti, ‘Cinematografo: barca e timone’ (1958), in Blasetti, Scritti sul cinema, 244.

38 Aprà, ‘Blasetti regista italiano’, 45.

39 A. Blasetti, ‘Ancora sul “Salvator Rosa”’, 287.

40 The influence, in both pre- and postwar periods, of a such a powerful and multi-faceted figure as Cesare Zavattini, a writer of several of his films, has been seen as important here. See O. Caldiron, La bella compagnia (Rome: Bulzoni, 2009), 41. Blasetti discussed the unusual recognition accorded to Zavattini while most writers received none at all. See ‘Dieci anni contro la dittatura del regista’ (1959), in Blasetti, Scritti sul cinema, 261.

41 A. Blasetti, ‘Il cinema arte composita o arte specifica’ (1952), in Blasetti, Scritti sul cinema, 233.

42 Blasetti, ‘Dieci anni contro la dittatura del regista’ (1959), in Blasetti, Scritti sul cinema, 261.

43 A. Blasetti, ‘Ancora contro la dittatura’ (1962), in Blasetti, Il cinema che ho vissuto, 155. The director could not be the sole author because ‘the actual making of a film is one only of the phases of the realisation of a cinematic work’.

44 Ibid., 155.

45 See A. Blasetti, ‘Alessandro Blasetti dei miei stivali’ (1956), in Blasetti, Il cinema che ho vissuto, 23.

46 Ibid., 23.

47 Blasetti, ‘La marcia su Hesperia’. 32.

48 Andreazza, ‘Director in Boots’, 34.

49 Aprà, ‘Blasetti regista italiano’, 46.

50 See F. Faldini and G. Fofi, eds., L’avventurosa storia del cinema italiano: raccontato dai suoi protagonisti, 1935-1959 (Milan: Feltrinelli, 1979), 248–49.

51 AAB-CdB, CRS 14, fasc. 0470, sotto-fasc. 3.

52 A. Blasetti, ‘Contro la dittatura’ (1959), in Blasetti, Il cinema che ho vissuto, 154.

53 A. Blasetti, ‘Il cinema arte composita o arte specifica’ (1952), in Blasetti, Scritti sul cinema, 225.

54 Ibid., 225–26.

55 L. Fioravanti and others, ‘Film-inchiesta e cinema moderno’ (1962), in Blasetti, Scritti sul cinema, 329.

56 Ibid., 329.

57 A. Blasetti, ‘Ancora sul “Salvator Rosa”’, in Blasetti, Il cinema che ho vissuto, 285.

58 Ibid., 285–6.

59 Ibid., 286.

60 Blasetti testimony, in Savio, Cinecittà anni trenta, 145.

61 Caldiron, La bella compagnia, 41.

62 A. Blasetti, ‘Il successo di un film incidente involontario’ (1978), in Blasetti, Il cinema che ho vissuto, 103.

63 Blasetti, Il cinema che ho vissuto, 21.

64 Aprà, ‘Blasetti regista italiano’, 44.

65 Dom, ed., ‘Blasetti e i “pregiudizi”’, in Blasetti, Il cinema che ho vissuto, 230.

66 S. Masi, ed., Costumisti e scenografi del cinema italiano, Vol. 1 (L’Aquila: Istituto Cinematografico dell’Aquila, 1989), 80–1. Veniero Colasanti recalls that in Quo Vadis one can see various items that he designed for Fabiola, including a chariot, sedan chairs and wine glasses that he had made in Murano.

67 Producers faced considerable difficulties in managing art films and genre products, not least because critics drew sharp distinctions which gave little credit to the latter. On these issues, see L. Bayman and S. Rigoletto, ‘The Fair and the Museum’, in Popular Italian Cinema, ed. Bayman and Rigoletto (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013), 11–15.

68 There was also a precursor in Blasetti’s own filmography: his Petrolini film, Nerone (Nero).

69 Aprà, ‘Blasetti regista italiano’, 82.

70 A. Blasetti, ‘Dio ricompensa in terra’ (1959), in Blasetti, Scritti sul cinema, 315.

71 Ibid., 315.

72 R. De Berti, ‘Europa di notte: The Revue Show in the Italy of the Economic Boom’, L’avventura no. 2 (2016): 337–56.

73 G. Gori, Alessandro Blasetti (Florence: Il Castoro/La Nuova Italia, 1984), 91.

74 See Blasetti’s account in Faldini and Fofi, L’avventurosa storia, 19.

75 A. Blasetti, ‘L’attore nel cinema’ (1944), in Blasetti, Scritti sul cinema, 174.

76 Ibid., 174.

77 Ibid., 179.

78 Ibid., 180.

79 A. Blasetti, ‘Perchè ho diretto proprio questo film (Prima comunione)’ (1950), in Blasetti, Scritti sul cinema, 301.

80 AAB-CdB, busta CRS 13, fasc. 0475, sottofasc. 6, Corrispondenza attrici donne, Letter from Germana Paolieri April 28, 1947.

81 Ibid., Card from Greta Gonda April 12, 1953.

82 Ibid., Letter to Greta Gonda April 17, 1953.

83 Ibid., Letter from Edy Campagnoli December 29, 1953. Campagnoli, at the time Miss Lombardia in the Vie Nuove beauty competition, would go on to work in television.

84 For a discussion of this, see S. Gundle, Bellissima: Feminine Beauty and the Idea of Italy (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007), 147–61.

85 AAB-CdB, CRS 13, busta 0475, sottofasc. 6, Corrispondenza attrici donne, Letter from Blasetti, July 24, 1953.

86 Aprà, ‘Blasetti regista italiano’, 83.

87 AAB-CdB, CRS 13, busta 0475, sottofasc. 6, Corrispondenza attrici donne, Letter from Blasetti, December 2, 1957.

88 Blasetti, Scritti sul cinema and Blasetti, Il cinema che ho vissuto. In addition, Gremese published the monographic volume I film di Alessandro Blasetti by Luca Verdone in 2007.

89 A. Blasetti, ‘Il successo di un film incidente involontario’ (1978), in Blasetti, Il cinema che ho vissuto, 103.

90 Blasetti testimony in Savio, Cinecittà anni trenta, 131–33.

91 Aprà, ‘Blasetti regista italiano’, 8.

92 Blasetti’s views on Freddi are quoted in Faldini and Fofi, L’avventurosa storia, 24.