ABSTRACT

The paper provides a novel perspective for the examination of urban public transport (UPT) systems based on a literature review of new institutional economics (NIE). New institutional economics is a rapidly growing interdisciplinary economic perspective which seeks to explain the role of institutions in the performance of socio-economic systems. It encompasses various economic theories including transaction cost economics, agency theory, contract theory and property rights economics. Although NIE-based approaches have been utilised in different sectors and policy areas, management and organisation of UPT systems is a policy area where the implications of NIE-related theories have not been thoroughly explored. UPT systems are complex and involve a variety of transport actors such as transport authorities, regulators, operators and passengers. These actors interact with each other as embedded in an institutional environment which structures the rules, hence determines the incentives, roles and liabilities for the actors. However, previous studies have generally taken this institutional environment as given and have not problematised it. This paper seeks to provide a concise literature review of UPT through the perspective of NIE to delve into the institutional configuration of UPT systems so that an institutional account of UPT is given. An institutional framework is proposed to help structure the current literature on UPT. To explore the applicability of NIE in conceptualising and problematising the issues concerning the management of UPT, the paper attempts to delineate the institutional landscape of UPT. The informal and formal institutions, governance structures and contractual relationships in UPT are examined through the lens of NIE. These institutional levels constitute the building blocks for the institutional arrangement of the UPT systems, and the proposed institutional framework for the analysis of UPT systems reviews and examines each institutional level in a systematic way. The paper explores the potential added-value that NIE provides, identifies the research gaps in the literature, and finally, shows the future avenues for NIE-inspired UPT studies.

1. Introduction

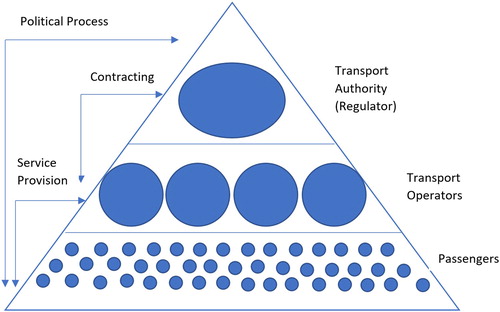

The urban public transport (UPT) systems have a significant role in reducing the traffic congestion, providing alternative means of travel for growing car usage and contributing to the sustainability for the quality of urban life (Vuchic, Citation2005). UPT systems are complex systems (Rietveld & Stough, Citation2004) which include social, economic, political, technological and organisational aspects. To develop and implement effective policies to improve the system, the relationships between these aspects as well as the actors constituting the system should be considered in an integrated and holistic way. Main actors of UPT systems are government, operators, and passengers. While the government in the form of a regulator or transport authority plays a regulatory role in the management of public transport systems, operators provide public transport services to the passengers. In some cases, local governments or municipalities directly provide public transport services to the passengers with or without franchised, contracted or deregulated private operators. Main modes of public transport include bus, rail, waterborne and paratransit modes with a variety of subcategories.

All public transport entities or organisations constituting UPT systems are embedded in an institutional environment which shapes the interests, incentives, and actions of these organisations. Defined as ‘the rules of the game’ (North, Citation1990), institutions play an important role in the organisation of UPT systems. The interdependence of actors providing complementary and integrated transport services requires an institutional framework by which roles, interests, and actions of the UPT actors are defined. Deregulated models, for example, can result in uncoordinated and disintegrated service provision unless such a well-defined institutional framework is in place. The role of institutions is also crucial in the selection of cost-efficient and effective UPT governance models. The institutional framework of UPT systems includes both informal (e.g. habits, traditions, customs, and norms) and formal (e.g. laws, property rights and regulations) institutional elements (Williamson, Citation2000). The organisational forms, governance structures, contractual practices and procurement methods can be given as examples of institutional issues in the management of UPT, which directly affect the performance of those systems.

Similar to the neoclassical economics view, classical urban transport management and planning approaches have tended to assume perfect rationality, full information and competitive markets (Small, Citation2013), deemphasizing the role of institutions. Phenomena in urban transport such as travel behaviour, transport demand, and decisions concerning investment are explained by aggregating over the behaviour of transport actors (Schwanen, Banister, & Anable, Citation2011). Most of the studies in UPT management and organisation literature take the institutional framework as granted and do not make the analysis of institutions as the object of their studies. However, transport actors relate with each other as embedded in an institutional environment which condition the behaviour of transport actors.

An institutional analysis of UPT seeks to consider the implications of institutional elements on the performance of the overall UPT system. New Institutional Economics (NIE) is the body of literature which deals with the institutions and the institutional environment which characterise the rules within which organisations and markets operate (Ménard, Citation1995). NIE encompasses different economic theories such as transaction cost economics (TCE), the principal-agent approach (agency theory), contract theory and property rights economics (Williamson, Citation2000). The main theoretical assumptions of NIE include positive transaction costs between the actors, incomplete contracts, costly information and imperfect property rights (Ménard & Shirley, Citation2014a), which is often overlooked in UPT literature. This is especially the case for developing countries and metropolitan areas where rapid urban growth and resulting transport problems together with a weak institutional setting make the consideration of institutions indispensable in UPT analysis.

The specific purpose of this paper is to identify and examine the institutional issues in UPT systems from a NIE perspective. The concepts and theories developed within the NIE literature, including transaction costs, agency theory, contracts and property rights are particularly relevant in that regard since they help conceptualise the interrelated role of organisations as actors within their institutional settings. These actors have interests, incentives, powers, liabilities, and actions which constitute the institutional environment. Asymmetries among the transport actors in terms of power, information and resources should be considered while conceptualising and examining the institutional environment. Therefore; a general account of actor relations within the public transport field is needed for any institutional analysis so that a robust institutional framework can be developed to mitigate the externalities resulting from those relations. To do this, two main branches of NIE are employed in this paper: the Williamsonian transaction cost economics branch focusing on the structure of governance and organisational arrangements and the Northean institutional analysis branch dealing with the institutional change and institutional environment (Ménard & Shirley, Citation2014b).

This paper intends to fill an important gap in the literature by exploring the implications of NIE for understanding UPT issues with a concise review of NIE literature, which mainly covers the fundamental issues of NIE. Although there are many studies in the literature addressing public transport issues by partially utilising NIE-related concepts, theories and approaches; this study is the first attempt to ‘systematically and holistically’ analyze and capitalise on the insights provided by NIE. The previous studies draw on agency theory, transaction cost economics and institutional change approaches to illuminate one aspect of a specific urban transport issue. This study not only consolidates the previous literature in UPT and provides an overview but also adds value by discussing the implications of NIE and highlighting the research gaps, aiming to be a literature review paper (Wee & Banister, Citation2016) in the field of UPT and NIE. Trying to conceptualise the UPT area as an action area and presenting a picture of UPT landscape based on a NIE perspective, this paper attempts to broaden our comprehension of the features, development, and functions of the real world UPT institutions and organisations.

The rest of the paper is organised as follows. Section 2 reviews the extant literature about NIE, its basic assumptions and theoretical underpinnings and the empirical studies using an institutional perspective in transport studies. It also proposes an institutional framework for the analysis of UPT systems. According to this proposed institutional framework, Section 3 examines the informal institutions, and the formal institutions are analyzed in Section 4. Section 5 focuses on the governance structures and organisational forms from a NIE perspective, and Section 6 gives an account of the contractual relations in UPT. Discussions of the issues are permeated throughout the paper. Section 7 concludes with a summary of important insights and suggests future research in the field.

2. New institutional economics: theoretical underpinnings and empirical applications

2.1. Theoretical underpinnings

Early or old institutional economics, with proponents John Commons, Thorstein Veblen and Daniel Bromley, underline the legal, social and cultural foundations of the economic structures and the evolutionary and habit-based processes by which institutions are established and changed. It was put forward against the individualist assumptions of neoclassical economics. According to old institutional economics, human preferences are determined by institutions rather than individual cognition. However, old institutional economics lacked rigorous and systematic theoretical foundations and concerned more with the description of specific cases. New institutional economics, on the other hand, emerged to fill this gap, integrated the assumptions of neoclassical economics such as ‘rational economic agent’ with the institutional assumptions and sought to explain, rather than describe, the determinants of institutions and examine the institutional change dynamics (Hodgson, Citation1998).

Although it is hard to pinpoint the exact definition of New Institutional Economics (NIE), its central claims and underpinnings can be propounded with some degree of generality. The central argument of the theories and approaches related with NIE is that institutions matter, and it is worth working through the relationship between institutional structure and the performance of any socio-economic system (Richter, Citation2005). NIE first emerged when Coase (Citation1937) underlined the importance of transaction costs to analyze the reasons for the existence of the firm. The concept of transaction costs was later applied to various issues of organisational theory (Alchian & Demsetz, Citation1972). Institutional factors such as property rights and governance structures are endogenized in NIE studies to reduce transaction costs, uncertainties as well as externalities and to increase collective social benefits from coordinated or cooperative actions (Rutherford, Citation2001). Transaction costs, property rights and contracts are some of the key concepts of NIE. The economics of property rights became the topic of interest in early studies of NIE. The study of Knight (Citation1924) on the social costs of road congestion can be regarded as an early precursor of future NIE studies in the transport field due to its emphasis on property rights arrangements. NIE is distinguished from other economic theories by its emphasis on institutions as rules and norms, its micro-level analysis of firms and market organisations together with their public policy implications, its dynamic capture of economic evolution which allows for interdisciplinary studies (Ménard & Shirley, Citation2014a).

Two approaches associated with two key figures stand out within the NIE tradition: Oliver E. Williamson and Douglass C. North. North (Citation1990) develops an analytical framework to explain how institutions and institutional change influence the performance of economies. According to North, institutions, or in other words ‘institutional environment’, constitute the general rules which shape and constrain the actions of the economic actors in individual level as well as organisational level. North’s historical perspective in NIE provides an important tool to examine the institutional change processes over time and how this translates into performance outcomes. Belief systems, ideologies, and mental models are important institutional factors in Northean approach (North, Citation1994). In traditional UPT literature, the effects of these factors on the management of UPT systems have seldom been considered.

Williamson, on the other hand, emphasises the transaction cost minimisation in the selection of a certain governance type (Williamson, Citation1981). Developing a transaction cost economics (TCE) view of governance structures, he regards the transaction as the central unit of analysis and argues that the comprehension of transaction cost economising is crucial for the study of organisations by assessing to what degree their governance structures help economise on these transaction costs. Unlike North’s emphasis on institutional environment, Williamson focuses on ‘institutional or organizational arrangements’ whereby economic entities structure their activities and carry out transactions according to the rules defined within the institutional environment. TCE tries to respond to the question of whether the market or the firm as a form of production is economically more efficient governance option for a certain transaction. In this sense, TCE logic is quite important in the analysis of government outsourcing (Williamson, Citation1997). In this paper, Northean and Williamsonian approaches are employed in a complementary manner to illuminate the issues in UPT systems. By this way, the mechanisms through which organisational arrangements including contractual relations in public transport systems are embedded in the institutional environment can be better explored to bridge the gap between those domains.

The term ‘institutions’ come to refer to different meanings in various contexts in the NIE literature. Various definitions in the literature underline different aspects of institutions. However, the concept of rules is central to all definitions. Denzau and North (Citation1994) refer to the rules as ‘embodied belief systems and norms of individual behavior’. Even though some studies tend to regard organisations as institutions (Linarelli, Citation2010); organisations are often considered a subset of institutions. In this paper; we adopt a Northean approach to institutions defined as ‘the formal rule set or rules of the game’ (North, Citation1990), and regard organisations as the players operating under this formal rule set. Since UPT systems are not just technical systems but also socio-political constructs, they are influenced by the institutions of the market and society in which they operate (Curtis & Low, Citation2016). This political play of power is a kind of game governed and influenced by the institutions. Therefore, Northean understanding of institutions suits our purpose in analyzing the UPT field.

2.2. Empirical applications

NIE-related approaches have been utilised in understanding the features and development of institutions and its effect on economic performance in various countries, sectors, markets, and organisations. Although there are many studies using an institutional analysis approach in transport studies (Gwilliam, Citation1979; Haynes, Gifford, & Pelletiere, Citation2005; Rietveld & Stough, Citation2004) and urban transport studies (Low & Astle, Citation2009; Macário, Citation2007; Stone, Citation2014); these studies do not employ a specifically NIE perspective in their analysis. These studies tend to regard institutions as the organisations managing transport or urban transport sector. The most widespread conception of institutions as ‘the rules of the game’ is lacking in those studies. The only study, to our knowledge, having a specific NIE orientation in transport studies is a study by Groenewegen and De Jong (Citation2008) which tries to explain the institutional change in the construction and maintenance of transport infrastructure in the context of liberalisation in Nordic countries. In addition to this study, Button (Citation2010) refers to NIE, though not in a detailed manner, in his book ‘Transport Economics’, when explaining the institutional structures.

The lack of NIE-oriented studies in the analysis of UPT does not mean that the concepts related to NIE are not used. For example, transaction cost economics and agency theory are utilised in the literature, which will be extensively examined in Sections 5 and 6. However, these studies do not aim to base their research on the conceptual foundation of NIE. They generally use these concepts to partially support their arguments. The fact that NIE has not attracted much attention in UPT studies is not surprising when we think of the compartmentalisation tendency in transport studies and NIE as a multidisciplinary perspective incorporating such disciplines as economics, political science, sociology, organisation theory, management, and law.

2.3. An institutional framework for urban public transport

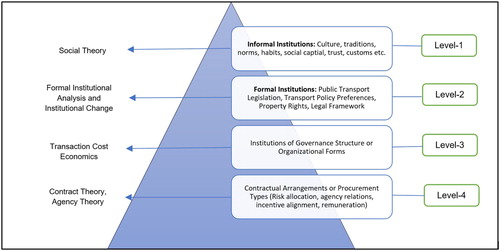

Williamson (Citation1998) proposes four levels of social analysis to analyze the economics of institutions. His schematisation of these levels is useful for conceptualising and positioning the institutional environment for any organisational field, including UPT systems. The transactional relationships between transport actors in any public transport system occur not in a vacuum, but in a particular institutional environment. shows the institutional levels of UPT systems, constructed by adapting Williamson’s illustration of the economics of institutions diagram.

Figure 1. Institutional levels in UPT, Adapted from Williamson (Citation1998).

The higher levels in the institutional pyramid influence and constrain the lower levels, and the lower levels give feedback to the higher levels. Although NIE has been mainly concerned with levels 2 and 3 (Williamson, Citation2000), levels 1 and 4 are not totally outside the domain of NIE-based approaches. Formal institutions are socially embedded in informal institutions such as culture, norms, and customs. Similarly, contractual arrangements cannot be totally separated from governance structures or organisational forms. Williamson refers to level 2 as the institutional environment, while levels 3 and 4 include institutional or organisational arrangements where actors structure their behaviour and transactions among them occur as prescribed by the rules defined in level 2.

In the following sections, the main theories and approaches in NIE are reviewed for each institutional level one by one with a view to accommodating them for UPT field. The Northean approach is drawn on for the institutional levels 1–2 where informal and formal institutional levels and institutional change dynamics are examined, whereas Williamsonian approach is utilised for the institutional levels 3–4 which covers the governance structures and contractual arrangements.

3. Informal institutions

The first institutional level deals with the informal institutions, an area which is often downplayed in UPT studies. Informal institutions include elements such as social capital, trust, culture, norms, routines, traditions, customs, and habits. Informal institutions take a long time to change; therefore, require long-term planning approaches. The economic actions of the actors together with the formal institutions are all embedded in informal institutions (Granovetter, Citation1985). Trusting partnership, for example, is a newly emerging type of contracting between transport operators and authorities, which try to capitalise on the level of trust (Stanley & Hensher, Citation2008). Habits and customs shape the passengers’ transport behaviours to a large degree, apart from economic considerations. Social theory is an appropriate methodological tool to develop theoretical frameworks to describe, examine and analyze the phenomena at this level.

Social networks having informal institutions such as norms and trust facilitate economic exchange where formal institutions have limited ability (Granovetter, Citation1985). Informal contracting mechanisms like relational governance have some advantages over formal contracting mechanisms (Zenger, Lazzarini, & Poppo, Citation2000). Long-term relationships among various actors lead to an increased cooperation and trust level; and an idiosyncratic culture, routines, customs, and habits develop over time. Social capital includes tacit knowledge, which develops through the relations between actors and tasks over time which is hard to codify, transfer or write down. Paratransit informal operators in most developing countries, for example, exhibit properties of social networks having its unique working culture, norms and routines in the way transport services are provided. In weak institutional environments, informal institutions may help promote good governance practices. Similarly, in weak UPT settings where formal transport modes fail to adequately deliver service provision, informal paratransit modes of transport fill an important gap. Collective action is also facilitated or hampered by the degree of social capital an actor group has. In many Indian cities, for example, informal transport modes such as rickshaws and casual carpooling systems fill an important gap left by uncoordinated, disconnected and inadequate formal bus and rail modes (Pojani & Stead, Citation2017). Even though they provide flexibility and first and last mile connectivity, the regulatory environment in which they are operating is often ambiguous. This ambiguity of the rules and norms in such an informal environment might lead to a lower service quality.

Community transport systems are another good example of how social capital, an important element of informal institutions, can positively contribute to the provision of transport services, especially for excluded social groups which have poor access to formal public transport modes such as financially disadvantaged, disabled or the elderly (Gray, Shaw, & Farrington, Citation2006). For example, Sheffield Community Transport is a non-governmental organisation which provides charitable community transport services in Sheffield, UK and funded by several trusts. However, the effectiveness of such schemes is dependent on the level of social capital along with other informal institutions such as social networks, norms, values, and trust.

Transport demand management (TDM) schemes provide useful policy tools to change the demand dynamics and travel behaviour of people, hence reduce or relocate the travel demand. Understanding the role of informal institutions such as travel habits, culture and norms is critical to figure out the effectiveness of TDM policies in changing behaviour. Therefore, the NIE approach can provide a broader conceptualisation of proposed TDM policies and underlines the dynamic interaction between first and second institutional levels, which correspond to the informal institutions and transport policies, respectively.

When we review the literature regarding the role of informal institutions in UPT, main issues which have been addressed so far mainly include the role of trust in partnerships (Sørensen & Longva, Citation2011), relational contracting (Stanley & van de Velde, Citation2008) and the relationships between formal and informal institutions in public transport (Hrelja, Monios, Rye, Isaksson, & Scholten, Citation2017). The issue of routines and habits in urban transport travel behaviour and mode choice has been covered extensively in the literature (Schwanen, Banister, & Anable, Citation2012; Van Acker, Van Wee, & Witlox, Citation2010). The collection of articles within the book ‘Transport Systems of Russian Cities: Ongoing Transformations’ (Blinkin & Koncheva, Citation2016) adopts a clear institutional perspective in their examination of Russian urban transport systems. Included in this book, the paper of Vorobyev, Shulika, and Vasileva (Citation2016) is particularly remarkable in its explicit expounding of informal institutions in UPT. It refers to ‘ideas, norms, cultural conventions and cognitive frames’ in shaping the behaviours of transport actors. It also examines in detail how the main actors in UPT and their interests shape the way UPT systems are designed and organised.

Studies examining the role of informal institutions in UPT are still in their infancy. Although the examination of the role of trust in contracts and especially novel contracting types such as relational contracting have been well covered so far, there is still room for analyzing the role of trust between transport actors, other than authority-operator relations. For example, the role of trust and cooperation among transport operators, between operators and passengers and between authority and passengers in performance outcomes present interesting areas of research. To create an efficient as well as an integrated UPT system, the issue of designing an institutional environment where trust and cooperation between the operators and authorities, competition between transport operators and collaboration of all actors are ensured is critical. Considering the informal institutions through an NIE perspective can inform this discussion. The role of social capital and social networks have not been adequately covered in the literature. This issue can be illuminating in understanding the associations of operators especially in developing cities. Social capital can alleviate the collective action problems (Ostrom, Citation2007). Social capital including norms, trust, and networks can fill the gap left by the formal institutions in developing countries. Operationalisation of these factors in UPT remains still unexamined. Uncovering the effect of informal institutions will provide a broader framework for researchers to interpret the performance differences between different UPT systems, beyond simply comparing the key performance indicators of these systems.

4. Formal institutions or institutional environment

Formal institutions constitute the rules of the game, or the institutional environment (Williamson, Citation2000), covering the bureaucratic, legal and political rules and regulations. To analyze the formal institutional elements comprising this institutional level, one should focus on these rules as well as how these rules shape and influence the actions and behaviours of the actors. To give an example from property rights which is part of the legal environment, public ownership of assets brings about different incentives than private ownership (Alchian & Demsetz, Citation1973), having significant cost efficiency implications. The effect of public or private ownership of operations on performance outcomes is also dependent on the features of the institutional setting. Potential high agency costs between the private operators and public authorities, for example, negatively influence both cost efficiency as well as network effectiveness outcomes for the privately-owned operations. Agency costs are higher when the level of trust and cooperative culture, which are the elements of the informal institutional environment, is not adequate to counterbalance the effect of divergent motives displayed by the public authorities and the profit-seeking private operators. Besides the ownership forms, policy preferences and resulting regulatory reforms also change the way that the actors relate to each other. Regulation and deregulation trends change the way an industry is organised.

Unstable political institutions in developing countries play an important factor in the UPT performance. Institutional change in this level can be directed and orchestrated by policymakers, the outcomes of which can be observed in a shorter period of time compared to the change in level 1. Level of competition, market entry, and exit conditions, public or private ownership are all important formal institutional elements which substantially affect the performance of UPT systems. How market entry and exit conditions affect the service performance outcomes depends on the characteristics of the institutional environment. In an institutional setting where the rules of competition are not well defined or mature enough, and so the market is open to collusions and oligopolistic market arrangements, then strict barriers to market entry and exit are likely to lead to negative performance outcomes. The problem can be aggravated by the lack of cooperation and trust among the transport authorities and operators, the informal institutions which can potentially offset the lack of effective formal institutions.

The institutional environment might contain conflicting rules thereby actors are trapped in ‘institutional swamps’ (Olthaar, Dolfsma, Lutz, & Noseleit, Citation2017). To design an institutional environment where the rules are consistent and compatible with each other is crucially important for the effective functioning of UPT systems. In such an institutional fabric, actors can anticipate the outcomes of their actions together with the environmental responses and adjust their behaviours accordingly. On the contrary, in an institutional setting where different formal institutional elements require conflicting responses from the actors, the performance of this system is likely to be lower than the former one due to additional transaction costs for resolving such institutional dilemmas. On the other hand, a well-structured formal institutional environment can boost the effectiveness of transport policies by creating synergies among those policies. This is particularly important for policy packaging, the effectiveness of which is dependent on the implementation context (Givoni, Citation2014). NIE provides a broader understanding of the institutional context where the transport policies are embedded and implemented, hence increasing the chance of successful policy packaging implementations.

The most widely covered issues in the formal institutional level are regulations and ownership issues and how they shape the UPT policies and outcomes. Pucher (Citation1995) comparatively analyzes government policies regarding the UPT in US and Europe by taking into account the ownership structure (public or private), public regulation, financing arrangements and compares the costs and productivity in two papers. The issue of public or private ownership on technical efficiency of the urban transport sector has been widely discussed (Pina & Torres, Citation2001), underlining the role of contestable markets for positive outcomes such as high technical efficiency. Gwilliam (Citation2008) propounds the idea of the regulatory cycles where regulation and deregulation attempts alternate, and the role of public and private sector stabilises in the long run, focusing on the institutional environments in developing as well as developed countries. NIE, through property rights economics perspective, provides a theoretical perspective to frame this discussion. For example, the efficiency of competitive tendering as a procurement model depends on clearly defining and assigning the property rights of assets such as routes, bus stops, interchange stations. Besides cost efficiency, weak property rights also have implications for service quality. For example, paratransit minibus operators in Istanbul cause considerably low levels of service quality in terms of safety, reliability, and convenience due to a weak assignment of the property rights for the minibus routes (Akyuz, Citation2015).

Estache and Gómez-Lobo (Citation2005) add to the ownership and liberalisation literature in public transport policy by focusing on market failures and regulatory intervention mechanisms, the effectiveness of which can be regarded as a sign of the strength of formal institutional environment. Hensher and Wallis (Citation2005) draw attention to the effect of the regulatory framework on the success and failure of competitive tendering, which supports our argument that higher institutional levels influence the effectiveness of lower ones. A substantial body of literature in this area can be found in the Thredbo conference series, named ‘International Conference on Competition and Ownership in Land Passenger Transport’. The journal of ‘Research in Transportation Economics’ publishes selected papers from the conference, dedicating a special issue for Thredbo conference papers. NIE perspective has the potential to contribute to this literature with a broader institutional perspective which can account for the contextual local differences in a variety of institutional settings.

The change in a political landscape is one of the most significant factors affecting the formal institutional environment. The market integration of EU countries and the need for reducing public budgets and subsidies, for example, have brought about a change in policies opting for franchising as a form of public transport delivery (Andersen, Citation1992). Another study on the institutional evolution of the urban transport market from a more theoretical perspective comes from Macário (Citation2005). She focuses on the relationship between regulations and institutional behaviour, bringing a system dynamics and complexity perspective to the study of the formal institutional framework. Low and Astle (Citation2009) contribute to the literature of formal institutions by tracing the evolution of urban passenger institutions in Melbourne, Australia spanning a very broad time horizon from 1956 to 2006. They explore the implications of path dependence and compare the interaction between road planning and public transport planning institutions. There are also studies in the UPT literature addressing how to develop effective regulatory frameworks for sustainable UPT systems in developing countries. Sohail, Maunder, and Cavill (Citation2006) underline the importance of close collaboration between transport actors, including regulators, operators, and passengers for the effectiveness of regulatory measures, suggesting self-regulatory measures based on the participation of all transport actors.

An institutional view of UPT can illuminate the institutional change dynamics involved in the long-term transformations. For example, the development of competitive tendering as a procurement model in public transport cannot be fully understood without considering the broader shifts in economic interest towards deregulation and privatisation beginning around the 1980s. EU Regulation 1370/07 for public transport passenger services to foster competition in procurement came later as part of the new formal institutional environment. Public service obligations (PSOs) are defined during the implementation of those regulations and policies to avoid the conflict of commercial interests with social interests, leading to some transaction costs in the form of enforcement and monitoring costs between regulators/authorities and operators. This is one example of how broader institutional change dynamics influence the structuring of the lower institutional levels.

Although the formal institutional level is widely covered in the UPT literature with extensive discussions about regulations, ownership structures, market failures, legislative changes, property rights of transport actors and policy changes, there are still potentially new areas to explore from a new institutional economics perspective. The dynamics of institutional change have been paid little attention together with the interplay of the formal institutional level with other institutional levels. Designing a consistent formal institutional environment where institutional elements do not overrule one another is still an area to be explored in detail. Institutions are also key elements of the ‘socio-technical regime’ in UPT systems. Formulating policies for the transition to a more sustainable urban transport future involves examining the linkages between the proposed transport policies and current institutions and NIE, through institutional change approach, can help better understand those transition dynamics.

5. Governance structures and organizational forms from transaction cost economics perspective

The third institutional level is the level of governance structures and organisational forms. Selecting an appropriate governance structure and associated organisational form is key to reduce the transaction costs among the transport actors. The governance structures in UPT include in-house municipal operations, contracting (route or network) and free-market initiative, in some cases, with additional contracting (Van De Velde, Veeneman, & Schipholt, Citation2008). Transaction cost economics (TCE) is used to examine the efficiency of transactions taking place in a particular governance structure. TCE approach provides an important perspective, to better illuminate the characteristics of the transactions taking place between public transport operators and authorities. Whether to introduce contracting to private transport operators or stay with in-house municipal operations is a policy decision which can be settled by including transaction cost considerations. Yvrande-Billon (Citation2006) uses the TCE framework to assess the expected and realised results of contracting and explains the observed differences. Evaluating the effectiveness of a certain governance structure requires the analysis of transaction costs, inherent in the relationship.

Even though a formal institutional environment is well-structured, without a transaction cost economising governance structure the efficient realisation of policy objectives is hampered. This institutional level concerns itself with structuring and aligning the relationships among the actors by choosing an appropriate form of organisation. TCE is one of the theories within the NIE literature which is used in the analysis of this institutional level. Apart from TCE, the adaptive governance approach (Dietz, Ostrom, & Stern, Citation2003) along with the game-theoretic and evolutionary approaches (Nelson & Winter, Citation2002; Ostrom, Citation1990) are used, particularly for the governance of common-pool resources. Considering public transport as a common pool resource (Glover, Citation2012), those approaches are also helpful in organising effective governance structures for the management of UPT systems.

Although organisation and governance issues are widely covered in UPT literature, transaction cost perspective is rarely utilised in understanding why these specific organisational forms have been selected or which forms are more efficient and appropriate. The relationship between structural forms of urban public transport and performance together with the issue of organisational change is examined by Costa (Citation1996), without transaction cost perspective. On the other hand, the transaction cost approach has been widely employed without its implications on governance and organisation. For example, the study of Wegelin and von Arx (Citation2016) analyzes the transaction costs of different governance forms, namely competitive tendering in Germany and direct awarding in Switzerland, in rail public transport with implications on arguments for or against the competition. Canonico, De Nito, Mangia, Mercurio, and Iacono (Citation2013) analyze the alignment between transaction dimensions and governance structures in Italian public transport systems from a TCE perspective. Bel and Rosell (Citation2016) study the transaction costs of public and private firms within the urban bus system in Barcelona. The costs of vertical integration and vertical separation have been examined from a transaction cost perspective extensively in rail public transport systems (Merkert, Smith, & Nash, Citation2012; Mizutani, Smith, Nash, & Uranishi, Citation2015). However, in public bus operations, transaction cost perspective has not been utilised as widely as that of rail operations. This is understandable when we think of the much higher transaction costs involved in rail operations due to the high asset-specific investments.

Institutions facilitating lower transaction costs are crucial in terms of service quality outcomes as well as cost efficiency implications especially when contracting or competitive tendering is used as a procurement model. The measurement difficulties of the performance of an operator, one of the important constituents of the transaction costs, negatively influence the service quality outcomes. This is especially the case for the performance-based contracts where the remuneration is tied to the service performance outcomes such as ridership, reliability, and safety. TCE draws attention to search and information costs, bargaining costs and enforcement costs which are especially critical for competitively tendered public transport operations.

The indirect results of a well-structured institutional setting include ridership growth, better service design and service quality and, most importantly, cost efficiency. TCE, for example, helps reduce the costs associated with the transaction costs between the transport authorities and operators. Service planning functions such as scheduling, network planning, and station/stop planning are carried out by either the transport operators or the authorities. The effectiveness of these functions, when undertaken by either one of them, can be better understood with a TCE approach. Scheduling, for example, can be delegated to transport operators when transaction costs of authority-operator relations are low.

NIE, particularly through transaction cost economics (TCE) approach, can help better understand under which institutional circumstances deregulated models are more appropriate in terms of service effectiveness and cost efficiency. The decision of when to choose deregulation or competitive tendering as a governance model is influenced by the institutional features (Canıtez & Çelebi, Citation2018). In an institutional environment where the transaction costs between the transport operators and authorities are high due to high uncertainty, asset-specificity or frequency of relationships, market-based provision models (e.g. deregulated market models or competitive tendering) are less transactionally cost-economising. In this case, negotiated contracts or direct in-house provision models are more suitable. More generally, considering transition costs with a TCE approach for the selection of governance models offers a better cost-economising way.

Because of the differences in bus and rail transaction costs, separately seeking out the implications of transaction costs on governance structures is recommended. The literature still lacks a comprehensive understanding of transaction costs and governance structures in the organisation of public bus operations. Another deficiency is the relationship between the institutional environment and transaction costs. A well-designed institutional environment potentially reduces transaction costs by delineating the monitoring and enforcement rules in a clearer manner. Although TCE perspective has been widely used in operator-authority relations, an interesting research area might be the examination of passenger and authority relations. The identification of organisational forms through which the transaction costs of channelling passenger demands and interests are minimised is a problem area waiting to be explored. A comparative analysis of centralised transport authorities with decentralised fragmented governance forms in terms of their transaction cost implications is a topic that can be addressed via a TCE perspective.

The integration between land use and transport is important for sustainable urban development (Geerlings & Stead, Citation2003). Both policy integration (second institutional level) and governance integration (third institutional level) is crucial to realise the expected benefits of this integration. The compatibility of the policies influencing the UPT area is an integral element of a strong formal institutional setting. The fragmentation in the management and governance of land use and transport is a major problem, especially in developing countries. NIE provides a broader institutional framework to address both policy and governance aspects of land use and transport integration. For example, integration in governance on its own without integrating the policies at higher scales is not sufficient to ensure a full-fledged integration.

6. Contractual arrangements from agency theory and contract theory perspectives

Designing effective contractual arrangements where risks are allocated optimally and incentives are established to align with the conflicting interests is the main objective of the last institutional level. Here two theories from NIE literature stand out: contract theory and agency theory. Contracts being imperfect and incomplete are the two basic assumptions which are critical to NIE (Ménard & Shirley, Citation2014b). Contracts are unavoidably incomplete due to bounded rationality (Williamson, Citation2000). It is not possible to foresee all future contingencies. Incompleteness of contracts, when combined with other problems such as opportunism, adverse selection, and moral hazard, pose serious problems for the credibility of the markets. Elimination of these contractual hazards is the objective of the attempts at this institutional level. Procurement types in UPT including direct awarding, competitive tendering, negotiated performance-based contracts are arranged at this level. Remuneration models such as gross-cost, net-cost or incentive-based (Stanley & van de Velde, Citation2008) are selected so that incentives are properly set, risks are distributed, and agency costs are mitigated.

Agency relations between transport authorities, operators and passengers occur at this level, with different risk allocation and incentive alignment outcomes. Consideration of Principal-Agent relations between regulators and operators through an agency theory approach helps designing contracts that are effective in combating contractual hazards. Almost all contractual arrangements contain elements of agency. In planning UPT services, NIE also helps overcome the limitations of neoclassical outlook by taking into account the asymmetric information, bounded rationality and vested interests of the transport actors. This is especially important when planning the functions of transport operators and authorities.

Approaches based on agency theory are also utilised in the UPT literature. Authority operator relations are examined through agency theory by Pilar Socorro and de Rus (Citation2010) in Spanish urban transport contracts. Other studies include traveller mode-choice problems (Anwar, Citation2016), the role of social networks and moral hazard in the taxi industry (Schneider, Citation2010). Overall, this institutional level seems to be the most extensively researched institutional level together with the formal institutional environment level.

Concerns with asymmetric information, moral hazard, adverse selection, opportunism, principal-agent relationships should be addressed at this level. Agency theory provides a useful methodological tool to analyze the principal-agent relations between transport actors, including authorities, operators, and passengers. illustrates the relationships between those main transport actors:

The illustration in shows the main transport actors together with their relative powers and the type of relations among them. The size of spheres illustrates the relative power of the actors. Transport authorities or regulators are the most powerful actors of the UPT field. Transport authorities have a contractual relationship with transport operators, delegating the liability of transport provision to them. This makes transport authorities ‘Principal’, and transport operators, ‘Agents’, in agency theory terms. Passengers, individually, have the least degree of power; however, acting collectively, they elect the local government, who in turn appoints the board of directors of transport authorities. Conceptualising the relative power in these terms facilitate our understanding of many problems, arising from the agency relations between actors.

NIE can provide a conceptual backdrop for the contract design process where the behaviours, motivations, and interests of the actors involved are taken into consideration. Contract design elements are decided with different effects on incentives and risks. Even though the assumptions of neoclassical economics are applied at this level, the higher institutional factors such as the regulatory environment or governance structure influence and shape the actors’ behaviours. The consideration of this level as embedded in the higher institutional levels can help explain the performance differences among different urban areas, or cities, having different institutional arrangements. The same contract can result in different performance outcomes in different institutional settings. Hence, recourse to higher institutional levels can facilitate explaining the factors leading to those performance differences.

There is a broad literature in UPT covering the issue of contracting (Pedro & Macário, Citation2016; Veeneman & Smith, Citation2016). The notion of incomplete contracts is examined by Yvrande-Billon (Citation2006) in public transport contracts. Hensher and Stanley (Citation2010) suggest a performance-based negotiation contract to eliminate contractual hazards in competitive tendering. The positive service quality outcomes of the tactical level trusting partnerships (Stanley, Betts, & Lucas, Citation2007) depend on the critical role of informal institutions such as trust, a disciplined and cooperative partnership culture between the operators and authorities. The bus services in Melbourne, Australia where a tactical level trusting partnership is implemented provides a case for increased service quality performance indicators, including patronage growth, the timeliness of service provision and customer satisfaction (Stanley & Hensher, Citation2008).

Although research gaps within contractual relations have been quickly filled by new studies, what is lacking in those studies is an institutional outlook encompassing different institutional levels together. The effect of formal or informal institutional arrangements on contracting, for instance, brings a more dynamic perspective to NIE studies in UPT. Design of contracts can vary depending on the broader institutional environment. In an institutional setting where trust is high, and actors share a collaborative culture, one expects a more negotiation-based contracting. Empirical studies can confirm the validity of this argument. How different formal institutional elements such as ownership structure, regulatory environment, financing arrangements influence the contractual arrangements can be explored by further studies. Implications of agency theory, on the other hand, can be further sought out through the analysis of different urban transport actors besides operator-regulator relations. Passengers and regulators are also related to each other through an agency relation, where passengers are ‘principals’, and regulators are ‘agents’. The democratic political processes guiding this relationship is a potentially new area to study.

7. Conclusion

The complexity of the issues related with UPT requires an interdisciplinary perspective encompassing various fields such as economics, organisation theory, urban planning, engineering, political science, law and management, which is just what NIE is intended to provide. Although different theories and approaches from NIE literature such as agency theory and transaction cost economics have already been used in many UPT studies, a systematic and concise analysis and review of NIE literature with regard to its implications on UPT have not been attempted before. This review tried to fill that gap. In this respect, this paper does not just provide an overview of the relevant literature, but it also provides a critical review of UPT from a NIE perspective. Inspired by the exciting development of NIE in other research fields, we prepared the ground for future NIE-oriented transport studies. We believe that the NIE perspective is a useful conceptual framework for both practitioners as well as researchers. Although in this review, we first targeted researchers in NIE and UPT fields, the ideas and insights offered throughout the paper can be utilised by practitioners focusing on the institutional reform, policy transfer or systematic improvement initiatives.

The basic takeaway from NIE is to consider the elements of UPT as embedded within the broader institutional environment. Rules of the game shape the actions of actors and actors, in turn, shape the rules of the game in a mutually reinforcing way. This institutional perspective helps contextualise the problem areas in UPT so that they can be better addressed. Empirical evidence, on the other hand, to support the argument that NIE-based approaches indeed improve the service delivery outcomes can be the subject of further studies. In this study, we limited ourselves to showing the theoretical and conceptual links of NIE with how it can add value to the management and organisation of the UPT systems. The implications of behavioural economics-based approaches on transport planners’ or policymakers’ decision-making processes with respect to the institutional issues can also be studied in future studies.

The review structure developed in this paper by adapting Williamson’s framework to contextualise the economics of institutions can also be used in other review papers attempting to explore new sectors or economic fields in transport studies. Throughout the paper, this structure helped us specify the scope of our review by disentangling the institutional landscape in sublevels so that we are able to keep our focus on the salient institutional issues. All in all, NIE can indeed provide powerful tools, novel conceptions and helpful insights in the analysis of UPT issues. Taking stock of the current literature, we tried to open up new avenues for future research in this area and further studies with a NIE approach in other transport fields besides UPT promise new research territories. Therefore, future interest or disinterest in the subject of NIE in transport fields can validate or invalidate our endeavour for this review.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

References

- Akyuz, E. (2015). The solutions to traffic congestion in Istanbul. The Journal of Academic Social Sciences, 16, 442–449.

- Alchian, A. A., & Demsetz, H. (1972). Production, information costs, and economic organization. The American Economic Review, 62(5), 777–795.

- Alchian, A. A., & Demsetz, H. (1973). The property right paradigm. The Journal of Economic History, 33(1), 16–27.

- Andersen, B. (1992). Factors affecting European privatisation and deregulation policies in local public transport: The evidence from Scandinavia. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 26(2), 179–191.

- Anwar, A. M. (2016). Presenting traveller preference heterogeneity in the context of agency theory: Understanding and minimising the agency problem. Urban, Planning and Transport Research, 4(1), 26–45.

- Bel, G., & Rosell, J. (2016). Public and private production in a mixed delivery system: Regulation, competition and costs. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 35(3), 533–558.

- Blinkin, M., & Koncheva, E. (Eds.). (2016). Transport systems of Russian cities: Ongoing transformations. Cham: Springer.

- Button, K. (2010). Transport economics. Gloucester: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Canonico, P., De Nito, E., Mangia, G., Mercurio, L., & Iacono, M. P. (2013). Regulation issues in the Italian local transport system: Aligning transactions and governance structures. Journal of Management & Governance, 17(4), 939–961.

- Canıtez, F., & Çelebi, D. (2018). Transaction cost economics of procurement models in public transport: An institutional perspective. Research in Transportation Economics. Available online 21 March 2018. In Press, Corrected Proof.

- Coase, R. H. (1937). The nature of the firm. Economica, 4(16), 386–405.

- Costa, Á. (1996). The organisation of urban public transport systems in Western European metropolitan areas. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 30(5), 349–359.

- Curtis, C., & Low, N. (2016). Institutional barriers to sustainable transport. Oxford: Routledge.

- Denzau, A. T., & North, D. C. (1994). Shared mental models: Ideologies and institutions. Kyklos, 47(1), 3–31.

- Dietz, T., Ostrom, E., & Stern, P. C. (2003). The struggle to govern the commons. Science, 302(5652), 1907–1912.

- Estache, A., & Gómez-Lobo, A. (2005). Limits to competition in urban bus services in developing countries. Transport Reviews, 25(2), 139–158.

- Geerlings, H., & Stead, D. (2003). The integration of land use planning, transport and environment in European policy and research. Transport Policy, 10(3), 187–196.

- Givoni, M. (2014). Addressing transport policy challenges through policy packaging. Transportation Research Part B: Methodological, 60, 1–15.

- Glover, L. (2012). Public policy options for the problem of public transport as a common pool resource. Proceedings for the Australasian Transport Research Forum 2012.

- Granovetter, M. (1985). Economic action and social structure: The problem of embeddedness. American Journal of Sociology, 91(3), 481–510.

- Gray, D., Shaw, J., & Farrington, J. (2006). Community transport, social capital and social exclusion in rural areas. Area, 38(1), 89–98.

- Groenewegen, J., & De Jong, M. (2008). Assessing the potential of new institutional economics to explain institutional change: The case of road management liberalization in the Nordic countries. Journal of Institutional Economics, 4(1), 51–71.

- Gwilliam, K. (2008). Bus transport: Is there a regulatory cycle? Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 42(9), 1183–1194.

- Gwilliam, K. M. (1979). Institutions and objectives in transport policy. Journal of Transport Economics and Policy, 13(1), 11–27.

- Haynes, K. E., Gifford, J. L., & Pelletiere, D. (2005). Sustainable transportation institutions and regional evolution: Global and local perspectives. Journal of Transport Geography, 13(3), 207–221.

- Hensher, D. A., & Stanley, J. (2010). Contracting regimes for bus services: What have we learnt after 20 years? Research in Transportation Economics, 29(1), 140–144.

- Hensher, D. A., & Wallis, I. P. (2005). Competitive tendering as a contracting mechanism for subsidising transport: The bus experience. Journal of Transport Economics and Policy (JTEP), 39(3), 295–322.

- Hodgson, G. M. (1998). The approach of institutional economics. Journal of Economic Literature, 36(1), 166–192.

- Hrelja, R., Monios, J., Rye, T., Isaksson, K., & Scholten, C. (2017). The interplay of formal and informal institutions between local and regional authorities when creating well-functioning public transport systems. International Journal of Sustainable Transportation, 11(8), 611–622.

- Knight, F. H. (1924). Some fallacies in the interpretation of social cost. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 38(4), 582–606.

- Linarelli, J. (2010). Organizations matter: They are institutions, after all. Journal of Institutional Economics, 6(1), 83–90.

- Low, N., & Astle, R. (2009). Path dependence in urban transport: An institutional analysis of urban passenger transport in Melbourne, Australia, 1956–2006. Transport Policy, 16(2), 47–58.

- Macário, R. (2005). Institutional frameworks, regulatory agencies and the land passenger transport industry: Reflections on recent evolutions. Competition and ownership in land passenger transport. 8th International conference (Thredbo 8) Transport Engineering Programme Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

- Macário, R. (2007). Restructuring, regulation and institutional design: A fitness problem. Competition and ownership in land passenger transport. 9th International conference (Thredbo 9).

- Ménard, C. (1995). Markets as institutions versus organizations as markets? Disentangling some fundamental concepts. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 28(2), 161–182.

- Ménard, C., & Shirley, M. M. (2014a). The contribution of Douglass North to new institutional economics. In Institutions, property rights, and economic growth: The legacy of Douglass North (pp. 11–29). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Ménard, C., & Shirley, M. M. (2014b). The future of new institutional economics: From early intuitions to a new paradigm? Journal of Institutional Economics, 10(4), 541–565.

- Merkert, R., Smith, A. S., & Nash, C. A. (2012). The measurement of transaction costs—evidence from European railways. Journal of Transport Economics and Policy (JTEP), 46(3), 349–365.

- Mizutani, F., Smith, A., Nash, C., & Uranishi, S. (2015). Comparing the costs of vertical separation, integration, and intermediate organisational structures in European and East Asian railways. Journal of Transport Economics and Policy (JTEP), 49(3), 496–515.

- Nelson, R. R., & Winter, S. G. (2002). Evolutionary theorizing in economics. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 16(2), 23–46.

- North, D. C. (1990). Institutions, institutional change and economic performance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- North, D. C. (1994). Economic performance through time. The American Economic Review, 84(3), 359–368.

- Olthaar, M., Dolfsma, W., Lutz, C., & Noseleit, F. (2017). Markets and institutional swamps: Tensions confronting entrepreneurs in developing countries. Journal of Institutional Economics, 13(2), 243–269.

- Ostrom, E. (1990). Governing the Commons: The evolution of institutions for collective action. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Ostrom, E. (2007). The meaning of social capital and its link to collective action.

- Pedro, M. J., & Macário, R. (2016). A review of general practice in contracting public transport services and transfer to BRT systems. Research in Transportation Economics, 59, 94–106.

- Pilar Socorro, M., & de Rus, G. (2010). The effectiveness of the Spanish urban transport contracts in terms of incentives. Applied Economics Letters, 17(9), 913–916.

- Pina, V., & Torres, L. (2001). Analysis of the efficiency of local government services delivery. An application to urban public transport. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 35(10), 929–944.

- Pojani, D., & Stead, D. (2017). The urban transport crisis in emerging economies: An introduction. In The urban transport crisis in emerging economies (pp. 1–10). Cham: Springer.

- Pucher, J. (1995). Urban passenger transport in the United States and Europe: A comparative analysis of public policies: Part 2. Public transport, overall comparisons and recommendations. Transport Reviews, 15(3), 211–227.

- Richter, R. (2005). The new institutional economics: Its start, its meaning, its prospects. European Business Organization Law Review (EBOR), 6(2), 161–200.

- Rietveld, P., & Stough, R. (2004). Institutions, regulations and sustainable transport: A cross-national perspective. Transport Reviews, 24(6), 707–719.

- Rutherford, M. (2001). Institutional economics: Then and now. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 15(3), 173–194.

- Schneider, H. (2010). Moral hazard in leasing contracts: Evidence from the New York City taxi industry. The Journal of Law and Economics, 53(4), 783–805.

- Schwanen, T., Banister, D., & Anable, J. (2011). Scientific research about climate change mitigation in transport: A critical review. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 45(10), 993–1006.

- Schwanen, T., Banister, D., & Anable, J. (2012). Rethinking habits and their role in behaviour change: The case of low-carbon mobility. Journal of Transport Geography, 24, 522–532.

- Small, K. (2013). Urban transportation economics (Vol. 4). London: Taylor & Francis.

- Sohail, M., Maunder, D. A. C., & Cavill, S. (2006). Effective regulation for sustainable public transport in developing countries. Transport Policy, 13(3), 177–190.

- Sørensen, C. H., & Longva, F. (2011). Increased coordination in public transport—which mechanisms are available? Transport Policy, 18(1), 117–125.

- Stanley, J., Betts, J., & Lucas, S. (2007). Tactical level partnerships: A context of trust for successful operation. Competition and ownership in land passenger transport. 9th international conference (Thredbo 9).

- Stanley, J., & Hensher, D. A. (2008). Delivering trusting partnerships for route bus services: A Melbourne case study. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 42(10), 1295–1301.

- Stanley, J., & van de Velde, D. (2008). Risk and reward in public transport contracting. Research in Transportation Economics, 22(1), 20–25.

- Stone, J. (2014). Continuity and change in urban transport policy: Politics, institutions and actors in Melbourne and Vancouver since 1970. Planning Practice and Research, 29(4), 388–404.

- Van Acker, V., Van Wee, B., & Witlox, F. (2010). When transport geography meets social psychology: Toward a conceptual model of travel behaviour. Transport Reviews, 30(2), 219–240.

- Van De Velde, D., Veeneman, W., & Schipholt, L. L. (2008). Competitive tendering in The Netherlands: Central planning vs. functional specifications. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 42(9), 1152–1162.

- Veeneman, W., & Smith, A. (2016). Workshop 2 report: Effective institutional design, regulatory frameworks and contract strategies. Research in Transportation Economics, 59, 60–64.

- Vorobyev, A., Shulika, J., & Vasileva, V. (2016). Formal and informal institutions for urban transport management. In Transport systems of Russian cities (pp. 167–206). Cham: Springer.

- Vuchic, V. R. (2005). Urban transit: operations, planning, and economics. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

- Wee, B. V., & Banister, D. (2016). How to write a literature review paper? Transport Reviews, 36(2), 278–288.

- Wegelin, P., & von Arx, W. (2016). The impact of alternative governance forms of regional public rail transport on transaction costs. Case evidence from Germany and Switzerland. Research in Transportation Economics, 59, 133–142.

- Williamson, O. E. (1981). The economics of organization: The transaction cost approach. American Journal of Sociology, 87(3), 548–577.

- Williamson, O. E. (1997). Transaction cost economics and public administration. In Public priority setting: Rules and costs (pp. 19–37). Dordrecht: Springer.

- Williamson, O. E. (1998). Transaction cost economics: How it works; where it is headed. De Economist, 146(1), 23–58.

- Williamson, O. E. (2000). The new institutional economics: Taking stock, looking ahead. Journal of Economic Literature, 38(3), 595–613.

- Yvrande-Billon, A. (2006). The attribution process of delegation contracts in the French urban public transport sector: Why competitive tendering is a myth. Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics, 77(4), 453–478.

- Zenger, T. R., Lazzarini, S. G., & Poppo, L. (2000). Informal and formal organization in new institutional economics. In The new institutionalism in strategic management (pp. 277–305). Emerald Group Publishing Limited.