ABSTRACT

People travel by car for a wide variety of reasons. A large proportion of household travel is for non-commuting purposes, including social and recreational journeys. The emergence and (potential) diffusion of highly automated vehicles, also known as autonomous vehicles (AVs), could transform the way (some) people work and travel. Should they become mainstream, AVs could reshape patterns of leisure travel. To date, however, the impacts and implications of AVs beyond commuting trips have received minimal attention from transport scholarship. This paper presents a state-of-the-art review of literatures on AVs. It follows PRISMA guidelines and synthesises 63 papers on AV travel focusing on non-commuting journeys, including travel for purposes of leisure, tourism, shopping and visiting friends and relatives. Given the economic importance of the tourism sector and its inherent focus on non-commuting journeys, this analysis is supplemented with a review of the extent to which national tourism strategies of countries leading AV deployment include reference to AVs. The paper reveals an overwhelming focus on commuting journeys in existing AV studies as less than one-fifth of the reviewed academic sources include non-commuting as part of their wider analysis. The review's further key findings are that the interest of publics in AVs for leisure journeys appears to exceed that for commuting, sharing vehicles will be less likely when AVs are used for leisure and there is an absence of recognition in the literature that certain non-commuting journeys will require a lower SAE level of automation. Surprisingly, analysis of the national tourism strategies of countries most prepared to meet the challenges of AVs shows that just three countries make specific reference to AVs within their national tourism strategies. The paper contributes to setting future AV policy agendas by concluding that two gaps must be narrowed: one, the distance between how academic studies predominantly conceive of AV use (commuting) and articulated public interest in AVs for non-commuting journeys; and two, the lack of readiness in certain national tourism strategies to accommodate AVs. As non-commuting journeys are likely to represent some of the earliest trip purposes for which AVs could be adopted, the paper points to the potential barriers to AV uptake by remaining focused on a limited set of trip purposes.

1. Introduction

Within transport scholarship, it is well established that there are a variety of often interconnected trip purposes. Commuting trips (to work or education) are but one purpose for which people travel. Yet, commuting journeys remain the dominant focus of transport scholarship (Pudāne et al., Citation2019; Singleton, Citation2018; Woldeamanuel & Nguyen, Citation2018). This may be justified by the high number of regular commuting journeys undertaken globally on a daily basis. However, as an example, 40% of journeys in the United Kingdom are for non-commuting purposes (DfT, Citation2018). These journeys include recreational and social trips, such as for tourism, shopping, leisure or visiting friends and relatives (VFR).

The emergence of autonomous vehicles (AVs) has been coupled with highly divergent perspectives on their potential to improve the existing mobility system. Seen by some actor groups (e.g. innovators, national government agencies) as the solution to transport issues including congestion, collisions, inaccessibility and emissions, for others (Milakis, Thomopoulos, & van Wee, Citation2020; Thomopoulos & Givoni, Citation2015), AVs may represent a technology seeking a problem rather than a solution per se. Accordingly, critiques from the social sciences warn for instance that AVs will have distributional impacts across sections of society, wherein existing transport injustices and inequalities may be exacerbated (Cohen et al., Citation2020).

Many of the stated potential benefits from vehicle automation will only arise under a scenario of full vehicle automation, what the Society for Automotive Engineers (SAE) refer to as “Level 5” automation. The SAE levels present six stages (0–5) where responsibility for driving tasks transfers from the human-driver to the automated-driver. In brief, Level 5 depicts a scenario where all driving must be done by the automated system (such that even a person without a driving license could travel alone). Level 4 depicts full automation at particular times and places, but human-drivers must be able to regain control if required. Levels 0–3 describe degrees of driver assistance, but the human-driver retains responsibility. Since AV relevant standards are continuously updated based on technological and deployment advancements, this paper adopts the SAE defined levels of automation for the purposes of its review.

To date, there appears to be a skew in journey purpose towards commuting in AV research, which is accompanied by disciplinary and geographical imbalances, wherein the literature on AVs is slanted towards engineering and physical sciences, urban settings and the Global North (Cavazza et al., Citation2019; Gandia et al., Citation2019; Thomopoulos & Nikitas, Citation2019). Although there is speculation that urban tourism will be changed by future AV adoption (Cohen & Hopkins, Citation2019), the wider societal implications of AVs beyond commuting have received minimal academic attention (c.f. Kimber, Siegel, Cohen, & Thomopoulos, Citation2020). This paper helps address this important knowledge gap through a “state-of-the-art” review (c.f. Grant & Booth, Citation2009) of AV research that focuses on non-commuting journeys. Non-commuting journeys are understood here as those for recreational and social purposes including tourism, leisure, shopping or VFR.

Wider societal uses of AVs, such as for rural tourism, first/last mile travel for day-trippers or a trip to an out-of-town shopping mall can have important policy implications, in terms of both the business models required for non-commuting AV use and for regional and national tourism boards and destination management organisations (DMOs). For this reason, the review of academic literature in this paper is supplemented with an analysis of AV coverage within the national tourism strategy documents of leading countries according to the KPMG (Citation2019) Autonomous Vehicle Readiness Index. This signals the extent to which those countries deemed most ready for AV deployment overall actually consider strategic tourism planning for AVs.

This paper extends the work of Kimber et al. (Citation2020), which applied PRISMA search protocol to provide an initial review of the wider uses of AVs in non-commuting journeys. The present paper builds upon this previous work in three main ways: one, its review of AV literature uses the same PRISMA search protocol to provide a new search that includes all of 2019, which to date was by far the most prolific year for AV research; two, it reviews the extent to which national tourism strategies of countries leading AV deployment include reference to AVs, so as to evaluate the readiness of national tourism strategies to accommodate them, given the close links between travel and transport; and three, it develops a concluding set of agenda-setting recommendations for future AV research and policy development that includes the double-perspective of the status of non-commuting journeys in AV research and AVs in national tourism governance. The paper first considers the identified imbalances in AV research, highlighting the skew in AV literature towards commuting as the default journey purpose.

2. Imbalances in AV academic research

Academic research on AVs appears to be characterised by a number of imbalances, which at a minimum include disciplinary, geographical and trip purpose skews. As the primary purpose of this paper is to consider this last skew, the first two are only discussed briefly.

2.1. Disciplinary skews in AV research

While in recent years there has been growing attention from the social sciences on the impacts and implications of AV development, the literature remains dominated by technologically focused outputs from computer science, engineering, transportation and automation control systems scholars (Gandia et al., Citation2019). In 2017, it was reported that just six percent of AV literature could be categorised as social sciences (Cavoli, Phillips, Cohen, & Jones, Citation2017). Since that time, the important and productive roles for the heterogeneous social sciences have been clarified and articulated (Cohen et al., Citation2020).

The focus on technologies and the material development of AVs can be partially explained by the early stage of innovation development, and the technological requirements for AVs including not just the vehicles themselves, but also sensors, infrastructures and so on. Yet tech-centred scholarship is problematic in that it does not account for the highly social dimensions of AV development and, ultimately, deployment. Gandia et al. (Citation2019) and Yun et al. (Citation2016), for example, show how it will become increasingly important to consider the broader impact of AVs, particularly associated with social implications and business models (Pardi & Calabrese, Citation2020). Within existing social science scholarship, moreover, there is a somewhat narrow focus on public acceptability of and willingness to pay for AVs, whereas Cohen et al. (Citation2020) point to a broader range of themes, including, for instance, governance and power, distributional impacts, and multiple futures, to which social scientists may speak, and which could offer critical insights into the development, emergence and potential diffusion of AVs.

2.2. Geographical skews in AV research

Mirroring more general trends in transport research (Schwanen, Citation2018), AV research to date is characterised by a notable geographical imbalance. Urban areas and urban mobility have been at the centre of testing AV applications (Canitez, Cantafio, & Thomopoulos, Citation2018; Hopkins & Schwanen, Citation2018a), and the home to most public demonstrations. Following this, research has focussed on urban environments, largely in cities of the Global North (Cohen et al., Citation2020; Cohen & Hopkins, Citation2019). This urban-centricity is likely because of a number of complex factors, including urban mobility challenges, greater opportunities for upscaling, concentration of large key players with significant capital and the availability of technological infrastructure (Hopkins & Schwanen, Citation2018b, Citation2019).

Nonetheless, scholars have questioned how visions of driverless futures may be “differently imagined in the global north to the global south” (Porter et al., Citation2018, p. 758). While research such as that by Jain, Bhumre, and Jain (Citation2016), examining autonomous transport solutions in India, are an exception, it has been suggested that perceptions of AVs may not differ substantially between cities in the Global South and North (Pojani & Stead, Citation2018; Sanaullah, Hussain, Chaudhry, Case, & Enoch, Citation2016), a contention which requires closer scrutiny (van Wee, Milakis, & Thomopoulos, Citation2020).

2.3. Trip purpose skews in AV research

Scholarship on social perspectives of AVs has thus far focused mainly on commuting and day-time urban mobilities (Kellerman, Citation2018), and especially how AVs could transform commuting patterns (Faisal, Kamruzzaman, Yigitcanlar, & Currie, Citation2019; Moreno, Michalski, Llorca, & Moeckel, Citation2018; Nazari, Noruzoliaee, & Mohammadian, Citation2018). This may result from entrenched “problem” framings in transport scholarship which – problematically – positions commuting time as “dead” time that needs to be minimised. Transport scholarship has a long history of examining values of travel time based on such opportunity cost notions, i.e. “dead” time perceived as lost time that needs to be minimised in order for traveller utility to be maximised (González, Citation1997; Wardman, Citation2004). Making commuting trips quicker and/or more “productive”, became – and arguably remains – a preoccupation for many transport ministries, consultancies and academics, and a key factor in transport cost–benefit analysis (Börjesson & Eliasson, Citation2019). As such, AVs represent an opportunity to “enliven” this time and render it productive. Yet Singleton (Citation2019) suggests that travel time savings from AVs may be relatively modest. In the wider transport literature, the focus on commuting has been challenged. Law (Citation1999) offered a critique of the literature for its overemphasis on work journeys and its inattention to the many other kinds of trips that constitute important parts of daily life, while Cresswell (Citation2006) contends that all types of travel and mobility should be the focus of academic inquiry.

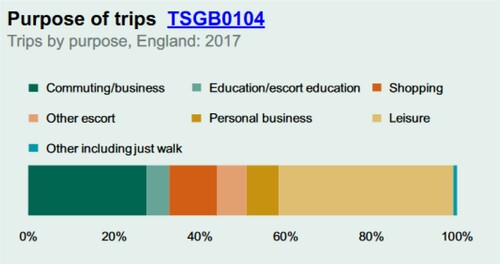

Nevertheless, travel statistics from the United Kingdom and the United States suggest that, contrary to this research focus, many trips are unrelated to commuting. Evidence from the UK Department for Transport (), for example, shows that 40% of all trips taken in England in 2017 were for leisure purposes (VFR, sports, holidays and daytrips). Whilst over 58% of surface rail journeys in England are for business and/or commuting purposes, this is not reflected in car-based journeys, where more are carried out for shopping than for commuting (DfT, Citation2014, Citation2018). In the United States this trend is more pronounced, with social and recreational journeys accounting for nearly 60% of household travel in 2009 (NTHS, Citation2009). In the early 2000s, the greatest growth in travel in the United States was unrelated to work.

Figure 1. Trip purpose of passenger travel in England. Source: DfT (Citation2018, p. 5).

Moreover, nascent studies suggest that the introduction of AVs will lead to increased AV use for non-commuting purposes (c.f. Cohen & Hopkins, Citation2019). These non-commuting trips are both interesting and important as they are discretionary trips taken with differing patterns, occupancies and storage needs from commuting journeys. Tourism, leisure, shopping and VFR journeys thus have significant implications for both AV design and right-sizing. Furthermore, AVs may ameliorate or exacerbate carrying capacity and crowding issues at visitor attractions and destinations, depending not only on whether the cars used are private or shared, but also on whether more collective AV forms are adopted, such as autonomous shuttles and buses (). The congestion found in the vicinity of tourist attractions and leisure spots can – at peak times of the day – be worse than city centre rush hour congestion (Federal Highways Administration, Citation2005). It therefore follows that the focus of AV research needs widening to incorporate recreational and social journeys beyond commuting.

Table 1. Dimensions of car-based commuting versus non-commuting.

Car-based commuting and non-commuting journeys may therefore be viewed as differing along a range of dimensions (), which are conceived in this paper as including travel purpose, whether the trip is by choice, regularity of the route, variability of distance, duration and time, typical occupancy in the vehicle, the material objects carried that dictate vehicle storage requirements and the key “problems” they pose for which AVs might render solutions. is of course a generalisation; we acknowledge overlaps and relationalities between these identified dimensions, that many trips do not have a single “purpose”, and that “non-commuting” is a rather broad category. Nevertheless, these differing features suggest that commuting and non-commuting can have substantial differences that demand attention when developing AV policies.

Against this background, this review paper is motivated by the concern that academic literature on AVs is skewed towards commuting journeys, particularly in the Global North's urban metropoles. It is not argued that these biases are intentional, but rather are the combined product of disciplinary and geographical skews in where AV knowledge has been produced (c.f. Schwanen, Citation2018), and the consequent defaults in their research focus, i.e. the urban commute. This paper therefore seeks to challenge this implicit bias in trip purpose by focusing on AV non-commuting journeys.

3. Methodology

For this paper, a “state-of-the-art” review was selected as it provides a balanced overview of evidence-based suggestions founded in relevant literatures (Grant & Booth, Citation2009). The aim of this paper, then, is to carry out a state-of-the-art review on non-commuting AV journeys following PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines (Liberati et al., Citation2009; Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, & Altman, Citation2009). For a more comprehensive overview of the method applied in this paper see Kimber et al. (Citation2020).

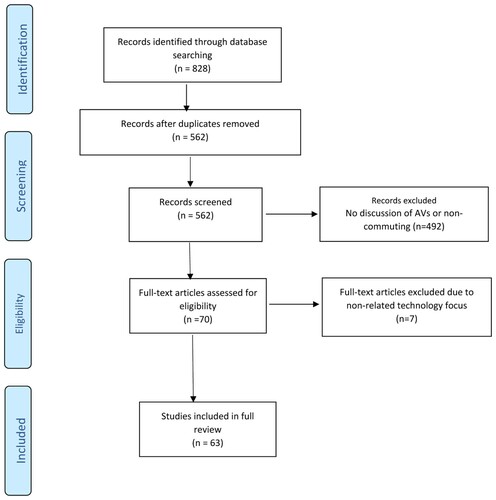

In sum, the review conducted and presented in this paper follows the PRISMA protocol (cf. Moher et al., Citation2009), adhering to a standard procedure that uses a PICO (Population, Intervention, Control and Outcome) framework that relates to the research question (Shamseer et al., Citation2015). Only written English-language academic sources (peer-reviewed articles, book chapters and conference proceedings) that focused on AVs and non-/commuting journeys were included in the review. No timeframes were applied to the review. To overcome potential biases or limitations from the use of a single database for the literature search the research identified sources through three databases: Scopus, Web of Science and Transport Research International Documentation (TRID).

The search terms (Table 3) were generated from the PICO Framework (). Building upon previous literature reviews (e.g. Cavoli et al., Citation2017; Gandia et al., Citation2019), the most commonly used words and phrases were identified and tested for relevance and suitability across the three databases. Following this, searches were run on the three databases multiple times between May 2019 and May 2020. The results were combined to form a single database of the literature retrieved and this was stored on Zotero.

Table 2. PICO Framework (Population, Intervention, Control and Outcome) utilised in this review.

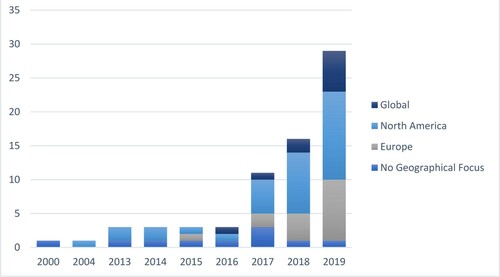

Across the three databases 828 publications were identified with publication dates between 1990 and 2019. Unsurprisingly, the majority of the retrieved literature was published since 2010, with the lion's share published in 2019 (). We followed PRISMA procedures to structure the review process (; Liberati et al., Citation2009; Moher et al., Citation2009). After removing duplicates 562 remaining publications were assessed for suitability according to the inclusion criteria described above. There are limitations to search engine retrieval, meaning that key sources may not be included in the sample (e.g. Cohen & Hopkins, Citation2019; Faisal et al., Citation2019; LaMondia, Fagnant, Qu, Barrett, & Kockelman, Citation2016; Nikitas, Kougias, Alyavina, & Njoya Tchouamou, Citation2017; Thomopoulos & Givoni, Citation2015). Where possible, the authorship accounted for this based on their knowledge of the literature. However it is acknowledged that this represents a limitation to the review and that important papers may still not be included in the review. This is unlikely to change the trends and findings reported below. In total, 63 articles were analysed by the authors. The contents of each source were analysed using a pre-determined framework. In order to account for reviewer bias (c.f. Barros et al., Citation2019), twenty percent of the articles were reviewed by multiple researchers.

Figure 3. PRISMA Flow Diagram. Source: Moher et al. (Citation2009).

In addition to this PICO state of the art review, this study reviewed national tourism strategy documents seeking to identify if and how AVs have been incorporated. Given that national tourism strategies tend to have a long-term horizon (e.g. 5 or 10 years), it has been anticipated that countries with strong tourism industries which also invest in AV deployment would include specific strategies merging these two objectives. Therefore, the KPMG AV Readiness Index 2019 (KPMG, Citation2019) was used to guide the country selection since this has been the only index available contrasting and ranking the capability of a country to deploy AVs. The top ranked countries for which relevant national tourism strategies could be found in English, again using the search strategy detailed in , have been reviewed.

Table 3. Search terms and strategy used in the review.

4. Findings

Our review of the published, academic, English-language AV literature depicts an overwhelming focus on commuting trips (). None of the reviewed literature focussed solely, and specifically, on non-commuting journeys. Twelve (19%) publications included non-commuting trips – such as leisure or recreational journeys – within their analysis and/or discussion. This finding points to the narrow focus of research on AVs, previously reported by Kellerman (Citation2018) and confirms the need for greater attention to be paid to a wider diversity of trip purposes in AV literature. It is particularly noteworthy that a number of papers within our review do not discuss trip types explicitly, but implicitly assume commuting as the default journey purpose. This is problematic in that it overlooks important differences between commuting and non-commuting (), and this is likely to inform dominant shared expectations of AV deployment.

Table 4. Overview of the 63 fully reviewed sources.

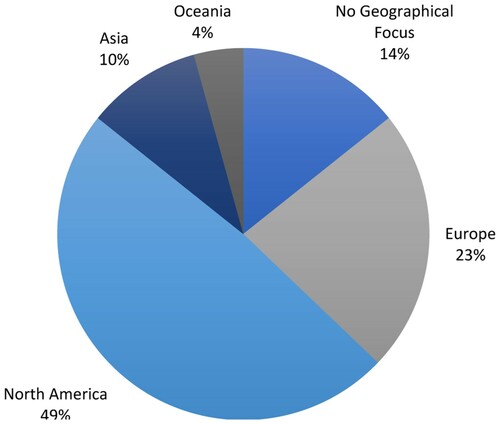

The reviewed literature was heavily skewed towards countries of the Global North, with a particular dominance of literature relating to case studies in North America (). Given the search was focused on English-language literature, it is unsurprising that nearly three quarters of the sources reviewed had an empirical focus on North America or Europe and it is likely that we excluded large volumes of scholarship published in non-Anglophone journals. This mirrors claims – albeit in English-language publications – that Anglophone countries (i.e. the US and European countries) are leading the trials and testing of AVs (Canitez et al., Citation2018), as also confirmed by the AV Readiness Index (KPMG, Citation2019); a claim which demands closer scrutiny and may well be refuted by non-Anglophone countries. Nevertheless, geographical differences were found within the sample, for example with differences between anticipated AV use in Europe and the United States, particularly as this related to business and ownership models, which is expanded upon below.

From the review, three key themes arose:

The interest of publics in AVs for leisure journeys appears to exceed that for commuting purposes (4.1);

Sharing of AVs is less likely for non-commuting journeys (4.2);

For some non-commuting purposes AVs may be operational sooner as they will require a lower SAE level of automation (4.3).

The review of national tourism strategies is summarised in , with only The Netherlands, Finland and Japan including some explicit reference to AVs or new mobility services within their tourism strategy. The Netherlands have realised the direct link between tourism and transport, which is reflected through the inclusion of smart transport within the accessibility pillar of their strategic priorities. Similarly, Finland is among the few countries that have also identified this link and make explicit references to all emerging technologies in their tourism strategy, including artificial intelligence and blockchain alongside AVs. The latter is no surprise given the investments and AV trials within the country during the past decade. On the other hand, there are references to AVs in the case of Japan, but they focus on non-directly relevant areas such as unmanned maritime vessels and the technology of road AVs, particularly about last-mile and platooning. Overall, this review clearly confirms that the lack of focus on non-commuting in AV literature is mirrored by contemporary national tourism policies largely ignoring AVs. The implications of these omissions are returned to in the concluding section.

Table 5. Explicit references to AVs within national tourism strategies in AV-ready countries. Blanks indicate unavailable for the purposes of this review – Data based on the 2019 AV Readiness Index (KPMG, Citation2019).

4.1. Leisure surpasses commuting in AV public interest

Of the papers which addressed leisure travel (n = 12), we find greater interest among publics in AVs for leisure trip purposes than for commuting. Laidlaw and Sweet (Citation2017), for example, found in Ontario (Canada) survey participants were interested in using an AV for discretionary trip purposes and more likely to use a shared automated vehicle for the purpose of recreation and entertainment than for errands and shopping, though they do not speculate why. Pudāne et al. (Citation2019) find that AVs may induce demand for irregular trips, such as VFR, and more frequent leisure travel. Moreover, when Kellett, Barreto, Van Den Hengel, and Vogiatzis (Citation2019) asked whether participants would consider using an AV for non-commuting journeys such as shopping, recreation and VFR, 71% agreed they would. So, then, it is interesting that just 12 of the reviewed sources (n = 63) mention leisure or recreation in their analysis. This may suggest a missing link between how academic studies conceive of AV use (and perhaps trip purpose more generally) and articulated public interest and stated intended behaviour. Framing AVs in commuting terms, akin to Cohen et al.'s (Citation2020, p. 2) critique of predominant technological framings, may work to obscure the social complexities surrounding AVs and “narrow the range of possible futures currently being imagined”.

One explanation for the interest of publics in AV leisure trips may come from Ashkrof, Homem de Almeida Correia, Cats, and van Arem (Citation2019) who point to the different distance types of leisure versus commuting travel and find greater interest for AV journeys used for long-distance leisure travel rather than short-distance commuting trips. This could be explained by way of the marginal value of travel time, which has been estimated as less negative for leisure over commuting trip purposes, and long-distance over short-distance (Ashkrof et al., Citation2019). This could be due to activities such as sleeping during an AV trip appearing more feasible for long-distance/duration travel, and when occupants are at leisure. It has been suggested that AVs could allow sleeping holidaymakers to arrive at their destination after travelling overnight, hardly noticing the journey time (Pudāne et al., Citation2019). The use of AVs for long-distance leisure journeys may then compete with other transport modes including rail and coach journeys and short-haul flights (Cohen & Hopkins, Citation2019). Such a mode shift has potentially significant implications for a variety of transport sectors, as well as sector emissions, therefore the non-commuting (potential) use of AVs, in relation to other modes, demands further attention. This should include future consideration of not only “driverless cars”, but also public forms of transport such as potential autonomous shuttles, buses and coaches.

There are important overlaps between commuting trips and travel for other purposes. Trip chaining patterns (Primerano, Taylor, Pitaksringkarn, & Tisato, Citation2007), for example, show complex and interlinked purposes and places of travel which often include different household members. Research on trip chaining has shown how work-related travel is often overrepresented when chains are overlooked. Moreover, trip chaining behaviour has been shown to prevent some people from using active or public modes (Hensher & Reyes, Citation2000) including for non-worker groups (Daisy, Millward, & Liu, Citation2018). Shared AVs may present an opportunity for trip chaining to occur with multiple trip purposes. Within our review, for instance, it became clear that some studies make assumptions of trip purpose for commuting, but later acknowledge that leisure activities – such as watching television – may be undertaken within the AV during the commute (Pudāne et al., Citation2019; Wadud & Huda, Citation2018). This adds complexity to the picture, with trip-purpose data becoming muddled, but even more important when considering AV journeys.

While appreciating the overlaps and relationalities between different trip purposes, there are a range of features which characterise and distinguish between commuting and non-commuting journeys (c.f. ). One such feature can be storage requirements, as also pointed out by Hao, Li, and Yamamoto (Citation2019). It has long been acknowledged that car purchasing behaviours are based on hypothetical and rare uses – such as a potential desire to go camping. Therefore, some purchase decisions are made with extra capacity for camping equipment, even though the vehicle may be used for this purpose a limited number of times. Although some publications have focussed on the requirement for storage for commuting trips (e.g. Singleton, Citation2018; Woldeamanuel & Nguyen, Citation2018), to date there has been limited attention paid to storage needs for non-commuting travel (for exceptions who briefly consider this see Haboucha, Ishaq, & Shiftan, Citation2017; Malokin, Circella, & Mokhtarian, Citation2019; Pudāne et al., Citation2019). This is a significant omission, as storage becomes more – rather than less – important when considering leisure and tourism travel with items including luggage, baby carriers, pets and sports equipment (e.g. skis) impacting upon AV user requirements and ultimately, AV design. Under a private ownership business model, it is likely that vehicle purchasing behaviours will remain as described above, yet under a shared use business model, people can select a “right size” vehicle for the trip purpose, and this may require some redesign of vehicles.

4.2. Sharing of AVs is less likely for non-commuting journeys

Encompassed by the term shared autonomous vehicles (SAVs), vehicle and ride sharing is a vital issue highlighted in scholarship in relation to AV deployment. Shared mobility practices are already an important part of discussions on the potential benefits of AVs (c.f. Haboucha et al., Citation2017; Narayanan, Chaniotakis, & Antoniou, Citation2020), and sharing is widely held to be a desirable and fundamental element of AV deployment, particularly from the perspective of policy-making, as claims of environmental benefits are highly dependent on shared ownership models.

It has been claimed that travellers may be prepared to use SAVs if it would reduce their time and financial costs for commuting trips (Webb, Wilson, & Kularatne, Citation2019). It is likely that willingness to use a SAV will vary depending on current mode of transport and trip purpose. Laidlaw and Sweet (Citation2017) reported that current car drivers are the least likely to use SAVs overall, but 60% of public transport commuters articulated interest in using them for their commute, suggesting that SAVs would take ridership from public transport rather than reducing private vehicle numbers. Our review has also found that studies from the United States primarily assume privately owned AVs, whereas those assuming SAVs are largely originating from European contexts. These findings were reiterated by Lavieri and Bhat (Citation2019), who reported that the presence of a stranger was more acceptable for a commuting trip than for a leisure trip. Different social dynamics and norms may explain this, for instance, for commuting journeys, silence amongst strangers is socially acceptable and often preferred (although this will differ within and between countries and cities), whereas for group social and recreational trips sharing a vehicle with stranger/s may be less comfortable as the group may wish to talk and have private communication. Moreover, when journeys involve recreational passengers drinking alcohol (Malokin et al., Citation2019), sharing with strangers may become even more undesirable, particularly if it is unpredictable. Such anxieties associated with sharing AVs will only be heightened in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic.

When considering sharing outside of commuting some nuances emerge, which resonates with Cohen et al.'s (Citation2020) assertion that social context plays a crucial role in publics’ opinions of potential AV use. For example, Moreno et al. (Citation2018) observe that pick-up waiting time for SAV journeys are important if users are going to a doctor appointment or running errands. This does not mean that pick-up waiting time is not also important in routine commuting, but it suggests that sharing may be less feasible for some non-commuting journeys due to their irregularity, depending on how punctual and rapid on-demand SAVs become (Hao et al., Citation2019). Nazari et al. (Citation2018) also observe that interest in using SAVs is less for non-commuters than commuters and suggest this may be because productive use of in-vehicle time is less urgent outside of a regular commute.

Using a “willingness to share” concept in comparing commuting and leisure journeys in Dallas (United States), Lavieri and Bhat (Citation2019) draw attention to the importance of privacy, in addition to the typical variables of cost and time used in such studies. Although they find that sharing may be more easily promoted within commuters, the authors suggest that ride hailing services appear to be an option for promoting AV ride sharing for leisure journeys. Barriers to sharing are likely to remain when non-commuting journeys are taken as a group of friends and/or a family. AV shape, size and occupancy is an important consideration and requires further exploration. More can be learned from the introduction of services such as “Uber Pool” and “Lyft Shared / Line”, yet the current presence of a human driver is thought to create a greater sense of safety and trust (Kaur & Rampersad, Citation2018). The well-documented relationships and status associated with personal vehicles, alongside ownership regimes (Meelen, Frenken, & Hobrink, Citation2019), reflect the cultural norms of specific countries and cities, particularly in the Global South. Thus, it is highly unlikely that a universal model will exist. The contextual and cultural influences on willingness to share has significant implications for sustainability that will affect both non-commuting and commuting journeys. Finally, studies have not yet considered non-commuting SAV journeys by autonomous bus or coach. These more collective forms of AV transport, if leisure travellers are willing to adopt them, could result in less vehicles on the road for non-commuting purposes.

4.3. Lower levels of automation required for some non-commuting journeys

Automation levels, as described by the SAE and other levels of automation, emerged as an important theme in the review. There is significant interest in highly automated vehicles because it is only with this that many of the various activities (i.e. watching television, reading books) while travelling can be achieved (Kang & Miller, Citation2018; Malokin et al., Citation2019). There is a general consensus that the claimed benefits of AVs can only be realised at SAE Level 4 and above, with full – SAE Level 5 – automation often assumed in literature discussing the potential of AVs (e.g. Pudāne et al., Citation2019). Full automation will be required if one seeks to commute from home to workplace, in any (weather) conditions, whilst engaging in work or leisure activities.

Within literature on non-commuting AV trips, the possibility that non-commuting journeys could be taken at SAE Level 4, i.e. under restricted conditions, has been largely overlooked. These are likely to be SAVs that operate on predefined routes and under tightly controlled conditions, for example, as airport shuttles, linking airports or train stations and city centres, on urban sightseeing routes or at off-road locations such as zoos (c.f. Bainbridge, Citation2018 for an industry perspective on AV sightseeing tours, or “auto-tours”). Such Level 4 non-commuting AV applications may decide to operate only during the day, or in good weather conditions. provides an initial understanding of the ways in which AVs may vary by SAE level in their application to non-commuting journeys. While applications at Levels 2 and 3 are limited, it is evident that significant applications already begin at Level 4. Lower levels of automation, along with greater reported interested in AVs for leisure purposes rather than for commuting trips (Laidlaw & Sweet, Citation2017), points towards non-commuting journeys as having the potential to become some of the earliest adopters. This finding further extends the importance of stimulating academic interest, and research into the application of AVs beyond commuting, to include the diversity of purposes for which travel is taken, and particularly trips currently taken by private car.

Table 6. Non-commuting AV applications by SAE Level.

5. Conclusion

Whether or not AVs mainstream in the forms and volumes some expect, remains to be seen. Nonetheless, many academics and practitioners (as well as many other actor groups) around the world are interested in the potential offered by AVs, as well as offering important critical reflections and interpretations. Yet, to date, we have shown that the vast majority of literature on AVs is either explicitly or implicitly focused on their use for commuting purposes. This is despite, for instance, 40% of journeys in the UK being for non-commuting purposes. The review presented in this paper was motivated by this concern; namely, that academic literature on AVs focuses heavily on commuting journeys, particularly in urban metropoles of the Global North. We acknowledge, however, that reviewing only English-language literature may work to replicate a bias towards Anglophone academia, and particularly the case studies of AV use in Euro-America and Australasia.

The paper's review has revealed an overwhelming focus on commuting journeys in existing AV studies. Just under one-fifth of the reviewed sources included non-commuting as part of their wider analysis, albeit this was often a marginal concern, with the remainder ignoring non-commuting entirely. Some papers failed to explicitly state the trip purpose focus of their research, but by default appeared to be excluding non-commute journeys. Of papers in which a geographical focus could be identified, all but three focused on countries and cities of the so-called Global North, confirming this paper's argument that not only a journey purpose, but also a geographical skew exists in AV research.

Further key findings from the review are that interest among publics in AVs for leisure journeys appears to be higher than that for commuting, sharing vehicles will be less likely when AVs are used for non-commuting purposes, and that some non-commuting journeys will require a lower SAE level of automation. These findings suggest that, while currently not receiving much attention in the academic literature, non-commuting trip purposes could well be some of the earliest types of AV use. This suggests a gap exists between public interest and stated intended behaviour and how academic studies predominantly conceive of AV use. More scholarly attention is therefore required to investigate the multiple and diverse potential uses of AVs beyond commuting. This is even more important given the articulated barriers to sharing in non-commuting AV journeys, the negative consequences of this for the sustainability of the transport system and claims of sustainability benefits associated with AV development and diffusion (Thomopoulos & Givoni, Citation2015). The COVID-19 pandemic has heightened the urgency of this issue, as travellers are likely to be even less willing to use SAVs going forward in light of their perceived health risks through exposure to unknown fellow passengers.

Where AV research has considered non-commuting journeys, a surprising omission has been a lack of consideration as to how the built environment will be impacted. Potential changes, for instance to congestion, urban sprawl and parking requirements, are well-developed in AV literature that has assumed commuting as the dominant trip purpose (e.g. Tian, Sheu, & Huang, Citation2019; Zakharenko, Citation2016). However, AV use for leisure, tourism, shopping and VFR will also have significant impacts on the built environment, though these implications, aside from work by Cohen and Hopkins (Citation2019) on AVs in urban tourism, have barely been thought through. Future research and destination management policies will need to give particular emphasis to the positive and negative impacts of AV use for non-commuting purposes on built environments, such as the implications of AVs for parking areas at visitor attractions or shopping complexes.

The paper's review of academic literature was supplemented with an analysis of AV coverage within the national tourism strategy documents of leading countries based on the 2019 Autonomous Vehicle Readiness Index (KPMG, Citation2019). Analysis of the national tourism strategies in countries most prepared to meet the challenges of AVs showed that only The Netherlands, Finland and Japan have some explicit link between AVs and their tourism strategy. Given the high interest and investment devoted to AVs this indicates a lack of readiness in national tourism strategies and policies to accommodate AVs, where they, ironically, are most likely to be deployed first. This widespread omission is especially problematic given the likelihood that non-commuting trips, including those for tourism, are anticipated to be at the forefront of AV adoption.

In light of these gaps in AV research and national tourism strategies, this paper offers the following agenda-setting recommendations to future AV research and policy development:

AV literature should widen its focus to include non-commuting journeys and their associated impacts on AV deployment and the built environment;

AV-related policies and development require a greater focus on leisure and tourism journeys, particularly as these journeys may be the first for potential AV users;

National tourism office/administrations and destination management organisations should consider AVs and their wider impact within their future strategies, especially in countries that are readying themselves for SAE Level 4 AV deployment;

Ways must be found to overcome unwillingness to share AVs for non-commuting journeys. Actions will be needed to make passengers (e.g. families, vulnerable travellers) feel comfortable and safe travelling with unknown fellow passengers. Cultural and contextual influences on willingness to share will play an important role here;

Accommodating non-commuting travel needs in AV design (i.e. occupancy and equipment storage) will be key in expanding the global SAV passenger base;

Future AV research on non-commuting journeys should widen its focus beyond cars, to include more collective forms of transport such as autonomous buses and coaches;

The Global South needs greater research attention and inclusion in AV policy developments due to the high levels of urban growth forecasted, particularly in light of the potential of SAVs to serve urban transport network needs (for both commuting and non-commuting journeys) with a reduced fleet.

This paper's primary intention has been to shed light on the dominant focus on commuting in AV literature, which has neglected the importance of non-commuting journeys. It is our hope that this paper provides a basis and agenda for academics and policymakers to widen their focus on AVs in the future to include trip purposes such as leisure, tourism, shopping and VFR. The skew towards commuting found in the AV literature, and especially cases where commuting trips appear as the default purpose when it is not explicitly discussed, has a range of implications for not just AV deployment, but for how academics and policymakers understand the transport system more widely.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Ashkrof, P., Homem de Almeida Correia, G., Cats, O., & van Arem, B. (2019). Impact of automated vehicles on travel mode preference for different trip purposes and distances. Transportation Research Record, 2673(5), 607–616. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0361198119841032

- Bainbridge, A. (2018). Autonomous vehicles & auto-tours: What is an auto-tour and how will autonomous vehicles impact tours, attractions & cities? Retrieved June 30, 2020, from https://www.destinationcto.com/docs/AutoTour.pdf

- Barros, P., Fat, L. N., Garcia, L. M., Slovic, A. D., Thomopoulos, N., de Sá, T. H., … Mindell, J. S. (2019). Social consequences and mental health outcomes of living in high-rise residential buildings and the influence of planning, urban design and architectural decisions: A systematic review. Cities, 93, 263–272. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2019.05.015

- Börjesson, M., & Eliasson, J. (2019). Should values of time be differentiated?. Transport Reviews, 39(3), 357–375. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01441647.2018.1480543

- Canitez, F., Cantafio, G., & Thomopoulos, N. (2018). WISE-ACT Atlas of AV trials. WISE-ACT Workshop #1, Bratislava, Slovakia.

- Cavazza, B. H., Gandia, R. M., Antonialli, F., Zambalde, A. L., Nicolaï, I., Sugano, J. Y., & Neto, A. D. M. (2019). Management and business of autonomous vehicles: A systematic integrative bibliographic review. International Journal of Automotive Technology and Management, 19(1-2), 31–54. doi:https://doi.org/10.1504/IJATM.2019.098509

- Cavoli, C., Phillips, B., Cohen, T., & Jones, P. (2017). Social and behavioural questions associated with automated vehicles: A literature review. London: Department for Transport.

- Cohen, S. A., & Hopkins, D. (2019). Autonomous vehicles and the future of urban tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 74, 33–42. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2018.10.009

- Cohen, T., Stilgoe, J., Stares, S., Akyelken, N., Cavoli, C., … Wigley, E. (2020). A constructive role for social science in the development of automated vehicles. Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives, 6, 100133.

- Cresswell, T. (2006). On the move: Mobility in the modern western world. New York: Routledge.

- Daisy, N. S., Millward, H., & Liu, L. (2018). Trip chaining and tour mode choice of non-workers grouped by daily activity patterns. Journal of Transport Geography, 69, 150–162. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2018.04.016

- DfT. (2014). Transport Statistics Great Britain 2014 – Average number of trips (trip rates) and distance travelled by purpose and length- NTS0409. Retrieved June 12, 2020, from https://www.gov.uk/government/statistical-data-sets/nts04-purpose-of-trips

- DfT. (2018). Transport statistics Great Britain 2018 – moving Britain ahead, DfT Report, OGL. Retrieved June 1, 2020, from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/787488/tsgb-2018-report-summaries.pdf

- Faisal, A., Kamruzzaman, M., Yigitcanlar, T., & Currie, G. (2019). Understanding autonomous vehicles: A systematic literature review on capability, impact, planning and policy. Journal of Transport and Land Use, 12(1), 45–72. doi:https://doi.org/10.5198/jtlu.2019.1405

- Federal Highways Adminstration. (2005). Traffic congestion and reliability: Trends and advanced strategies for congestion mitigation. No FHWA-HOP-05-064. Retrieved June 10, 2020, from https://ops.fhwa.gov/congestion_report/chapter3.htm

- Gandia, R. M., Antonialli, F., Cavazza, B. H., Neto, A. M., de Lima, D. A., Sugano, J. Y., … Zambalde, A. L. (2019). Autonomous vehicles: Scientometric and bibliometric review. Transport Reviews, 39(1), 9–28. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01441647.2018.1518937

- González, R. M. (1997). The value of time: A theoretical review. Transport Reviews, 17(3), 245–266. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01441649708716984

- Grant, M. J., & Booth, A. (2009). A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information & Libraries Journal, 26(2), 91–108. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

- Haboucha, C. J., Ishaq, R., & Shiftan, Y. (2017). User preferences regarding autonomous vehicles. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies, 78, 37–49. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trc.2017.01.010

- Hao, M., Li, Y., & Yamamoto, T. (2019). Public preferences and willingness to pay for shared autonomous vehicles services in Nagoya, Japan. Smart Cities, 2(15), 230–244.

- Hensher, D. A., & Reyes, A. J. (2000). Trip chaining as a barrier to the propensity to use public transport. Transportation, 27, 341–361.

- Hopkins, D., & Schwanen, T. (2018a). Automated mobility transitions: Governing processes in the UK. Sustainability, 10(4), 956. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/su10040956

- Hopkins, D., & Schwanen, T. (2018b). Governing the race to automation. In G. Marsden & L. Reardon (Eds.), Governance of smart mobility (pp. 65–84). Emerald: Bingley.

- Hopkins, D., & Schwanen, T. (2019). Experimenting with vehicle automation. In K. Jenkins & D. Hopkins (Eds.), Transitions in energy demand: A sociotechnical perspective (pp. 72–93). Abingdon: Routledge.

- Jain, P., Bhumre, P., & Jain, S. (2016). Common Automobile Program to Improve Mass Transportation, SAE Technical Paper. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4271/2016-01-0154.

- Kang, D., & Miller, J. (2018). Low-effort techniques for incorporating driverless vehicles in legacy regional planning models. Transportation Research Board 97th Annual Meeting. Washington DC.

- Kaur, K., & Rampersad, G. (2018). Trust in driverless cars: Investigating key factors influencing the adoption of driverless cars. Journal of Engineering and Technology Management, 48, 87–96.

- Kellerman, A. (2018). Automated and autonomous spatial mobilities. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Kellett, J., Barreto, R., Van Den Hengel, A., & Vogiatzis, N. (2019). How might autonomous vehicles impact the city? the case of commuting to Central Adelaide. Urban Policy and Research, 37(4), 442–457.

- Kimber, S., Siegel, L., Cohen, S., & Thomopoulos, N. (2020). The wider use of autonomous vehicles in non-commuting journeys. In D. Milakis, N. Thomopoulos, & B. van Wee (Eds.), Policy implications of autonomous vehicles. Elsevier. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.atpp.2020.02.003

- KPMG. (2019). Autonomous vehicles readiness index, report. Retrieved June 1, 2020, from https://assets.kpmg/content/dam/kpmg/xx/pdf/2019/02/2019-autonomous-vehicles-readiness-index.pdf

- Laidlaw, K., & Sweet, M. N. (2017). Estimating consumer demand for autonomous vehicles in the greater Toronto-Hamilton Area: 2016 survey and model results. Transportation Research Board 97th Annual Meeting. Washington DC.

- LaMondia, J. J., Fagnant, D. J., Qu, H., Barrett, J., & Kockelman, K. (2016). Shifts in long-distance travel mode due to automated vehicles: Statewide mode-shift simulation experiment and travel survey analysis. Transportation Research Record, 2566(1), 1–11. doi:https://doi.org/10.3141/2566-01

- Lavieri, P. S., & Bhat, C. R. (2019). Modeling individuals’ willingness to share trips with strangers in an autonomous vehicle future. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 124, 242–261. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2019.03.009

- Law, R. (1999). Beyond ‘women and transport’: Towards new geographies of gender and daily mobility. Progress in Human Geography, 23(4), 567–588. doi:https://doi.org/10.1191/030913299666161864

- Liberati, A., Altman, D. G., Tetzlaff, J., Murlow, C., Gøtzsche, P. C., … Moher, D. (2009). The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), e1000100. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100

- Malokin, A., Circella, G., & Mokhtarian, P. L. (2019). How do activities conducted while commuting influence mode choice? Using revealed preference models to inform public transportation advantage and autonomous vehicle scenarios. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 124, 82–114. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2018.12.015

- Meelen, T., Frenken, K., & Hobrink, S. (2019). Weak spots for car-sharing in The Netherlands? The geography of socio-technical regimes and the adoption of niche innovations. Energy Research & Social Science, 52, 132–143.

- Milakis, D., Thomopoulos, N., & van Wee, B. (2020). Policy implications of autonomous vehicles, Vol. 5. Elsevier. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.atpp.2020.02.003

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Annals of Internal Medicine, 151(4), 264–269. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b2535

- Mongeon, P., & Paul-Hus, A. (2016). The journal coverage of web of science and scopus: A comparative analysis. Scientometrics, 106(1), 213–228. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-015-1765-5

- Moreno, A. T., Michalski, A., Llorca, C., & Moeckel, R. (2018). Shared autonomous vehicles effect on vehicle-Km traveled and average trip duration. Journal of Advanced Transportation. doi:https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/8969353

- Narayanan, S., Chaniotakis, E., & Antoniou, C. (2020). Shared autonomous vehicle services: A comprehensive review. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies, 111, 255–293.

- Nazari, F., Noruzoliaee, M., & Mohammadian, A. (2018). Shared versus private mobility: Modeling public interest in autonomous vehicles accounting for latent attitudes. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies, 97, 456–477. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trc.2018.11.005

- Nikitas, A., Kougias, I., Alyavina, E., & Njoya Tchouamou, E. (2017). How can autonomous and connected vehicles, electromobility, BRT, hyperloop, shared use mobility and mobility-as-a-service shape transport futures for the context of smart cities? Urban Science, 1(4), 36. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci1040036

- NTHS. (2009). National household travel survey 2009. Federal Highway Administration. Retrieved June 13, 2020, from https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/policyinformation/pubs/hf/pl11028/onh2011.pdf

- Pardi, T., & Calabrese, G. (2020). Editorial: New frontiers of the automotive industry. International Journal of Automotive Technology and Management, 20(2), 131–136.

- Pojani, D., & Stead, D. (2018). Policy design for sustainable urban transport in the global south. Policy Design and Practice, 1(2), 90–102. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/25741292.2018.1454291

- Porter, P., Stone, J., Legacy, C., Curtis, C., Harris, J., … Stilgoe, J. (2018). The autonomous vehicle Revolution: Implications for planning/The driverless city?/autonomous vehicles – a planner’s response/autonomous vehicles: Opportunities, challenges and the need for government action/three signs autonomous vehicles will not lead to less car ownership and less car use in car dependent cities – a case study of Sydney, Australia/planning for autonomous vehicles? Questions of purpose, place and pace/ensuring good governance: The role of planners in the development of autonomous vehicles/putting technology in its place. Planning Theory & Practice, 19(5), 753–778. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2018.1537599

- Primerano, F., Taylor, M. A. P., Pitaksringkarn, L., & Tisato, P. (2007). Defining and understanding trip chaining behaviour. Transportation, 35, 55–72. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11116-007-9134-8

- Pudāne, B., Rataj, M., Molin, J. E., Mouter, N., van Cranenburgh, S., & Chorus, C. G. (2019). How will automated vehicles shape users’ daily activities? Insights from focus groups with commuters in the Netherlands. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment, 71, 222–235. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trd.2018.11.014

- Sanaullah, I., Hussain, A., Chaudhry, A., Case, K., & Enoch, M. (2016, July 27–31). Autonomous vehicles in developing countries: A case study on user’s view point in Pakistan. Paper presented at AHFE 2016 International Conference on Human Factors in Transportation, Florida.

- Schwanen, T. (2018). Towards decolonised knowledge about transport. Palgrave Communications, 4, 79. doi:https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-018-0130-8

- Shamseer, L., Moher, D., Clarke, M., Ghersi, M., Liberati, A., … Stewart, L. A. (2015). Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: Elaboration and explanation. BMJ, 349, g7647. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g7647

- Singleton, P. A. (2018). How useful is travel-based multitasking? Evidence from commuters in Portland, Oregon. Transportation Research Record, 2672(50), 11–22. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0361198118776151

- Singleton, P. A. (2019). Discussing the ‘positive utilities’ of autonomous vehicles: Will travellers really use their time productively? Transport Reviews, 39(1), 50–65. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01441647.2018.1470584

- Thomopoulos, N., & Givoni, M. (2015). The autonomous car—a blessing or a curse for the future of low carbon mobility? An exploration of likely vs. desirable outcomes. European Journal of Futures Research, 3(1), 14. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s40309-015-0071-z

- Thomopoulos, N., & Nikitas, A. (2019). Smart urban mobility futures: Editorial for special issue. International Journal of Automotive Technology and Management, 19(1-2), 1–9.

- Tian, L., Sheu, J., & Huang, H. (2019). The morning commute problem with endogenous shared autonomous vehicle penetration and parking space constraint. Transportation Research Part B: Methodological, 123, 258–278.

- van Wee, B., Milakis, D., & Thomopoulos, N. (2020). Overall synthesis and conclusions. In D. Milakis, N. Thomopoulos, & B. van Wee (Eds.), Policy implications of autonomous vehicles. (pp. 315–326). Elsevier. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.atpp.2020.02.003

- Wadud, Z., & Huda, F. Y. (2018). The potential use and usefulness of travel time in fully automated vehicles. Transportation Research Board 97th Annual Meeting, Washington DC.

- Wardman, M. (2004). Public transport values of time. Transport Policy, 11(4), 363–377. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2004.05.001

- Webb, J., Wilson, C., & Kularatne, T. (2019). Will people accept shared autonomous electric vehicles? A survey before and after receipt of the costs and benefits. Economic Analysis and Policy, 61, 118–135. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eap.2018.12.004

- Woldeamanuel, M., & Nguyen, D. (2018). Perceived benefits and concerns of autonomous vehicles: An exploratory study of millennials’ sentiments of an emerging market. Research in Transportation Economics, 71, 44–53. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.retrec.2018.06.006

- Yun, J. J., Won, D., Jeong, E., Park, K., Yang, J., & Park, J. (2016). The relationship between technology, business model, and market in autonomous car and intelligent robot industries. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 103, 142–155. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2015.11.016

- Zakharenko, R. (2016). Self-driving cars will change cities. Regional Science and Urban Economics, 61, 26–37.