ABSTRACT

More than half a million people in the U.S. experience homelessness every day. Lacking other options, many turn to transit vehicles, stops, and stations for shelter. Many also ride public transit to reach various destinations. With affordable housing scarce and the numbers of unhoused individuals often surpassing the capacities of existing safety nets and support systems, transit operators face homelessness as a pressing issue on their systems and must implement policy measures from other realms beyond transportation to address it. Because of the health and safety implications for transit of the COVID-19 pandemic and the anticipated further rise in homelessness from the resulting economic downturn, studying and responding to the needs of these vulnerable travelers is critical.

We conduct a comprehensive literature review to identify articles discussing homelessness in transit systems. While only a handful of articles exist from the 1990s, there is an emerging literature in the last 20 years that examines different aspects of homelessness in transit systems. We identify and review 63 articles on homelessness in transit systems and other public settings to better understand the extent of homelessness in the U.S., and how transit agencies perceive its impacts. We also summarise literature findings on the travel patterns of unsheltered individuals, which show that public transit represents an important and common mode of travel for them. Lastly, we focus on responses to homelessness from the part of transit operators. We find two types of responses: 1) punitive, in which criminalisation, policing and enforcement of laws and codes of conduct prevail, and 2) outreach-related, which aim towards providing help and support to unsheltered individuals. We conclude by summarising our findings as well as the existing gaps in the literature.

Introduction

Shelter is a basic human need that far too many people lack. Homelessness is particularly visible in the U.S., where more than half a million individuals experience it every single night (U.S. HUD, Citation2020). In the last decade, many U.S. metropolitan areas saw the number of their unhoused population rise, despite efforts from local governments and nonprofits to address this problem (U.S. HUD, Citation2020). Moreover, the geographic distribution of homelessness is uneven, resulting from an interplay of many variables ranging from housing affordability to climate to the availability of shelters. For example, 47 percent of the unsheltered population in the U.S. is concentrated in California (Council of Economic Advisers, Citation2019). Homelessness is also present and possibly rising in other parts of the world, such as in some European cities (Crisis, Citation2018; Strauß, Citation2020), though the number of unsheltered individuals is significantly higher and the homelessness crisis particularly acute in North America (Shinn, Citation2007; Toro et al., Citation2007).Footnote1

The limited capacity of shelters and other social service agencies to meet the needs of a rapidly growing unhoused population has forced individuals experiencing homelessness to find shelter in various public spaces, including transit vehicles, bus stops, and transit stations. Many of them also use transit to reach destinations such as workplaces, shelters, and community service centres. With affordable housing scarce in some metropolitan areas and the scale of homelessness crisis often surpassing the capacities of existing safety nets, transit operators face these pressing issues themselves and must implement policy measures from realms beyond transportation to address them.

The coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic has only exacerbated these problems. In some North American cities, the numbers of people experiencing homelessness on transit has risen during the pandemic (Loukaitou-Sideris, Wasserman, Caro, & Ding, Citation2020). Fear of infection in homeless shelters is driving more unhoused people to take shelter on the streets and transit, creating public health concerns for transit agencies about the safety of their cleaning and operating staff and riders (Guse, Citation2020; Jaffe & Gowen, Citation2020; Laughlin & Madej, Citation2020), who are mostly essential workers (TransitCenter, Citation2020).

Although discussions in popular media, albeit often anecdotal, raise awareness of homelessness in transit environments, the scale of the problem has not been well-documented in scholarly research. Because of the health and safety implications for transit of the COVID-19 pandemic and the anticipated further rise in homelessness from the resulting economic downturn, studying and responding to the needs of these vulnerable riders is now more critical than ever. To that end, this literature review aims to collect and synthesise knowledge on the intersection of transit and homelessness: the extent of the phenomenon, the mobility patterns of unhoused individuals, the response of transit agencies, and possible ways for transit agencies to serve all of their riders, housed and unhoused.

In the sections that follow, we first discuss our methodology for conducting a comprehensive search of articles discussing homelessness on transit systems. We then proceed to the findings of our literature review, first discussing the extent of the phenomenon in the U.S., how transit agencies perceive its impacts, the travel patterns of individuals experiencing homelessness, and the transit industry’s responses to homelessness. We conclude by summarising the findings and implications of this literature review. Throughout the paper, we use “people experiencing homelessness” and “unhoused individuals” interchangeably to refer to those without housing (but who may sleep in homeless shelters or other temporary accommodations); we use “unsheltered individuals” to refer specifically to the subset sleeping without a roof over their heads or in places otherwise unfit for human habitation.

Research methodology

To review issues of homelessness on transit, we conducted a comprehensive search for articles on homelessness in transit environments. However, we also recognise that a transit operator is a public agency that manages transit vehicles, stations and/or stops, and other facilities, which can be considered public spaces. Thus, we include in this review not only articles focussing on homelessness on transit but also those that discuss homelessness in other types of public space managed by public and quasi-public entities. Our exploration of articles on homelessness in other public spaces, while not comprehensive, was sufficiently thorough to offer useful reference points.

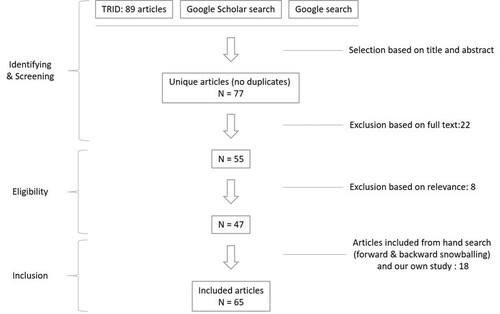

For the former search, we used keywords such as “homeless,” “(public) transit,” “(public) transport,” and variations thereon on databases including the Transport Research International Documentation (TRID) service and Google Scholar. We employed Google search to capture relevant “gray” literature, such as professional and agency reports. We did not limit the geographical scope of our search, but the articles we found almost exclusively study the North American experience—an indication of the severity of homelessness in North American cities in comparison with cities in other wealthy countries (Shinn, Citation2007; Toro et al., Citation2007). Nonetheless, the lessons from North America may be applicable to a large degree to metropolitan areas in other parts of the world that, as mentioned earlier, may face similar challenges. We also did not confine the temporal scope of our search but only found a handful of studies on the topic prior to 2000, and therefore, focussed primarily on studies of the last 20 years. For our search on homelessness in other public spaces, we used keywords including “homeless,” “(public) space,” “library,” “(public) park,” “business improvement district,” and variations thereon on Google Scholar. We first screened the articles based on their titles and abstracts and then based on their full texts. We then identified a few additional relevant works from the references of other articles. We also included our own empirical studies (Loukaitou-Sideris et al., Citation2020; Citation2021), which are the latest on the topic. In the end, we combined information from 65 articles to prepare this review. tracks this process.

Homelessness on transit

The phenomenon and its scale

Despite the scale of the homelessness crisis in many urban areas and its serious implications for transit operations, the intersection of transit and homelessness has received relatively little attention. In the 1980s and 1990s, only a few studies examined this topic, including a survey by the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey in which every responding transit agency and airport reported homelessness as an issue (Ryan, Citation1991, march), a survey of 203 unhoused individuals in Los Angeles (Meyerhoff, Micozzi, & Rowen, Citation1993), and an analysis of early efforts to connect unhoused individuals in transit facilities with social service providers (Schwartz, Citation1989, Citation1995). National analyses during the 1990s framed the issue as one of “vagrancy,” and were characterised largely by concern for the safety and security of housed riders (Boyd, Maier, & Kenney, Citation1996).

Recent studies from the past decade offer more detailed and nuanced insights (). A 2011 study surveyed unhoused individuals sleeping overnight in buses in Northern California’s Santa Clara County (Nichols & Cázares, Citation2011). Of 49 interviewees, about two thirds reported that the 24-hour bus line was their only shelter or one of their usual shelters; many slept on the bus every day. The sample of respondents had a greater share of men, African Americans, and unemployed people than the overall unhoused population of the area. Respondents cited dissatisfaction with shelter rules as a major reason for sleeping on the bus, while personal safety was another important consideration, especially for women. This study offers insights on who tends to use the bus as shelter, and why they do so; however, the small sample size from only one bus route in one region limits the generalizability of the findings.

Table 1. Extent and Character of Homelessness in Transit and Transport Environments.

While Nichols and Cázares (Citation2011) focussed on unhoused transit riders, a 2013 study surveyed state and provincial departments of transportation (DOT) in the U.S. and Canada about homelessness in their right-of-way (Bassett, Tremoulet, & Moe, Citation2013). The survey had 69 responses from 25 U.S. states and Canada’s British Columbia, out of which 70 percent reported either themselves or others at their agencies encountering people experiencing homelessness, and 40 percent said that their agencies regarded homelessness as an operational challenge. Although this study focussed on homelessness in state DOT-controlled right-of-way rather than in transit environments, the findings offer some reflection of the scale of the issue faced by transit agencies.

Two recent national syntheses, one under the Transit Cooperative Research Program (TCRP) (Boyle, Citation2016) and one for the American Public Transportation Association (APTA) (Bell et al., Citation2018), surveyed transit operators and conducted case studies on homelessness in transit environments. In the former, Boyle (Citation2016) surveyed 55 U.S. transit agencies to assess the presence of people experiencing homelessness and the extent to which agencies face challenges responding to homelessness. He found that homelessness was a challenge for most transit agencies (91%), about a third of which regarded it as a major issue. The survey also uncovered significant variations among agencies of different sizes: larger agencies with over 1,000 peak-time vehicles all characterised homelessness as a major issue; most agencies with fewer than 1,000 peak-time vehicles also deemed it an issue, but most of them only characterised it as a minor issue. However, only about 60 percent of responding agencies were able to provide an estimate of the size of the unhoused population on their systems, indicating a lack of accurate knowledge about the scale of homelessness. The APTA survey of 49 U.S. transit operators in 2018 inquired about their perceived “social responsibility” to address homelessness on their systems (Bell et al., Citation2018). It found that more than two thirds of these agencies believed that they should play a role in addressing homelessness.

In an attempt to understand how the problems of homelessness on transit have changed in recent years, how the COVID-19 pandemic has affected them, and how transit operators’ responses have evolved, the authors conducted a survey of 115 transit operators from the U.S. and Canada, and interviewed staff from agencies that implemented specific programmes to address homelessness on their systems. Our survey found that, excluding 30 agencies that could not provide an estimate, over half of agencies reported having 100 or more unhoused people on their systems daily, and 61 percent estimated that these numbers rose during the pandemic. Moreover, large agencies (with over 200 vehicles) were more likely to both report higher estimates and increases during the pandemic (Loukaitou-Sideris et al., Citation2020, Citation2021).

While the aforementioned studies inquire about the scale of homelessness, none drew directly on homeless counts or other systemically collected data. Only Nichols and Cázares (Citation2011) collected information directly from people experiencing homelessness who rode buses at night, though their study sample was small. The other studies sampled transit operators or departments of transportation, whose staff could only give estimated numbers of the unhoused population on their systems. These studies asked for staff’s subjective characterisations of the severity of the issue, offering a somewhat imprecise assessment of the extent of homelessness in transit environments. These limitations stem from the fact that very few transit agencies or municipal governments collect data on homelessness in transit environments (Loukaitou-Sideris et al., Citation2020).

Only a handful of researchers and nonprofits have undertaken such data collection. Saint Stephen’s Human Services counted unsheltered residents in Minneapolis, Minnesota (Legler, Citation2019, Citation2020). Across five biannual counts, over 55 percent of those counted were sleeping on transit. Also in Minnesota, an unpublished survey from Wilder Research (Citation2019) found that people seeking shelter on transit were more likely to be men between 25 and 54 years of age, low income, and unemployed. They were more likely than other unhoused individuals to have experienced homelessness for at least a year, to have been incarcerated, to be addicted to drugs or alcohol, to have a mental illness, and to panhandle. Synthesising these surveys with data from the few other places that disaggregate transit environments in their homeless counts, the authors found that transit serves as shelter in the U.S. for a high, though quite variable, share of unsheltered individuals, but that differences in data collection methodologies, climate, service hours, and the level of shelter space available complicate comparisons across cities (Loukaitou-Sideris, Wasserman, Caro, & Ding, Citation2021).

In Europe, Heriot-Watt University researchers estimated that 11,950 people in the United Kingdom slept in vehicles, transit, or tents in 2017; unfortunately, the research as published did not separate out transit from these other settings. (Crisis, Citation2018). In Berlin, where homelessness and panhandling are also present (Busch-Geertsema, Citation2006; Mahs, Citation2005), a homeless census counted 154 people sleeping in transit stations—16 percent of the city’s unsheltered individuals and eight percent of all people experiencing homelessness (Strauß, Citation2020). From this admittedly limited evidence, it appears that transit is a frequent place for shelter for a potentially significant share of people experiencing homelessness, who represent more disadvantaged populations than peers sleeping elsewhere.

Perceived impacts

The APTA survey of 49 transit operators found that 73 percent of them believed that homelessness on their systems affects their ridership (Bell et al., Citation2018). On one hand, people using buses and trains as shelter or traveling to social service destinations increase transit ridership; on the other, their presence makes some other riders uncomfortable and deters some “choice riders” from using transit (Bell et al., Citation2018). Boyle (Citation2016) found that additional negative effects of homelessness reported by transit operators include uncleanliness, crime, disruption and harassment, need for service re-routing, fare evasion, funding challenges, and community opposition. However, a study focussing on Bay Area Rapid Transit—a California operator whose homelessness issues have received intense media focus—found that homeless counts had no significant independent effect on ridership (Wasserman, Citation2019; Wasserman et al., Citation2020).

In general, most agencies do not seem to quantify the budgetary or ridership impacts of homelessness on their operations (Loukaitou-Sideris et al., Citation2020). As a result, while homelessness undoubtedly has effects on transit service, safety, and quality, the literature is not clear about the extent of those effects.

Travel patterns and constraints on mobility

In contrast to the dearth of literature on the scale of homelessness in transit environments and its operational impacts, there has been more scholarly research on the travel patterns of people experiencing homelessness (). These studies reveal the important role played by transit in providing mobility for this disadvantaged population and confirm that certain transit environments are also used by unsheltered individuals as spaces for shelter or rest.

Table 2. Mobility and Transit Use Patterns of People Experiencing Homelessness.

A 2019 systematic literature review on the mobility patterns of people experiencing homelessness found that the primary travel mode for them is public transit (Murphy, Citation2019)—a stark difference from the low rate of transit ridership among the general public in the U.S. Another frequent transportation mode is walking, while biking and private cars are less common. Unhoused people travel for a variety of purposes, commonly including accessing medical services, visiting friends and family, going to food banks, attending religious services, and searching for a job (Murphy, Citation2019). Unhoused people travel on average nine to 14 miles daily; those with higher education levels, experiencing homelessness for longer durations, and living closer to bus stops tend to travel longer distances, while men, African Americans, and those living closer to rail stations tend to travel shorter distances (Murphy, Citation2019). Thus, not only is the mobility of unhoused people constrained, it also varies significantly among different groups of unhoused individuals.

Several studies included in Murphy’s (Citation2019) review provide further nuance on how unhoused people use public transit. Jocoy and Del Casino (Citation2008, Citation2010) conducted focus group interviews and structured surveys of people experiencing homelessness in Long Beach, California to study their mobility patterns and use of public transit. They found that over half used transit at least daily, and even those who owned cars drove them infrequently. Public transit and shuttle service provided by social service agencies represented the primary modes of travel for most respondents (65%), especially to access healthcare, jobs or job searches, and social services (the most common travel purposes identified). About two thirds of respondents paid for their transit trips with tokens or passes that social service agencies distributed or with cash; 38 percent paid reduced fares or rode for free after negotiating with the driver; and 27 percent did not pay. Most respondents had positive experiences riding transit, though many still faced unpleasant encounters: 38 percent reported not being picked up by drivers, and 12 percent reported being harassed by other riders (Jocoy & Del Casino, Citation2008, Citation2010).

Hui and Habib (Citation2016, Citation2017) conducted in-person interviews with people experiencing homelessness in Toronto, Canada to understand their travel patterns and travel decisions. They found that healthcare, social service centres, food banks, and social visits to friends and families were the top travel purposes of those interviewed, and most either walked (46%) or used transit (41%) for these trips. People holding a bus pass and those without alternative mobility options were more likely to ride transit seven days a week. Their findings paint a nuanced picture of unhoused individuals’ travel modes. Most unhoused people walk to grocery stores but take transit to food banks, part-time work, and social visits, while biking represents the third-most common means of travel. Younger people are more likely to travel for work-related purposes. Older adults are more likely to pay for a transit ticket rather than rely on walking, in order to save time, whereas newly or chronically unhoused individuals are less willing to do so (Hui & Habib, Citation2017).

Given the importance of public transportation for unhoused people, some studies have also sought to understand the barriers they encounter when riding transit. Cost is a common obstacle, as many people experiencing homelessness simply cannot afford transit fares (Homeless Alliance of Western New York, Citation2006; Jocoy & Del Casino, Citation2008, Citation2010). While some transit agencies offer discounted fares and passes, often through partnerships with social service agencies, many unhoused people still have trouble with payment because the process of getting these passes and replacing lost ones can be difficult (Guo, Citation2017; Loukaitou-Sideris et al., Citation2021; Scott, Bryant, & Aquanno, Citation2020). In some cases, only certain groups within the unhoused population qualify for subsidised passes, while others have to rely on single-trip tickets given to them for specified travel purposes (such as job searches and healthcare). The latter only offer limited access to the transit system and may impair their holders’ ability to maintain contacts with important social and community networks (Scott et al., Citation2020).

Another major constraint on the mobility of people experiencing homelessness is the lack of transit connectivity to destinations that are important to them. In many metropolitan areas, transit service and route patterns often limit unhoused people’s access to the regional labor market and to social services that may be spread out throughout the region (Homeless Alliance of Western New York, Citation2006; Jocoy & Del Casino, Citation2008, Citation2010). Indeed, a survey of the transportation needs of unhoused and very low-income people in Erie County, New York found that 42 percent of respondents had to reject an employment opportunity due to lack of transportation access to the job location, while 21 percent had missed a job interview due to difficulties with public transit (Homeless Alliance of Western New York, Citation2006). Apart from the lack of spatial connectivity, sometimes the lack of an integrated fare structure among different agencies in a large metropolitan region can also pose a barrier. Additionally, transit networks often fail to connect to shelters and other social services that are important to those experiencing homelessness (Jocoy & Del Casino, Citation2008, Citation2010). Surveyed unhoused individuals indicate that inadequate information about transit services and schedules, as well as poor accommodation for those with physical disabilities, represent major challenges to using transit (Guo, Citation2017).

These studies of individual mobility patterns offer important insights on the travel of people experiencing homelessness, highlighting their heavy reliance on walking and public transit and their mobility disadvantage. However, as Murphy (Citation2019) points out, this area of research lacks a consistent way of measuring transportation disadvantages experienced by the unhoused population and of collecting accurate data. For this reason, transit agencies may often have to design responses to transit homelessness and evaluate their effectiveness without the benefit of reliable data.

Thus far, we have discussed the presence of homelessness on transit, its perceived negative impacts on transit agencies, and the heavy dependence of unhoused individuals on public transit for their daily travel. In the next section, we discuss how transit agencies have responded to these issues of homelessness on their systems. We also compare the practices of transit agencies to those of other entities such as public libraries and Business Improvement Districts (BIDs) that manage public spaces and often encounter unhoused individuals.

Current practices of the transit industry

The rising visibility of people experiencing homelessness in public spaces over the last three decades has led to more interactions and sometimes conflicts between them and homeowners, business owners, local governments, law enforcement, and transit agencies. As early as 1991, an article in Mass Transit, the transit industry’s professional publication, provocatively asked: “The nation’s homeless are seeking refuge in transit facilities across the country. How do transit authorities treat a plight that has no simple cure?” (Ryan, Citation1991, march). Thirty years later, the answer does not seem to be clear, as many agencies face significant challenges in addressing homelessness (). As mentioned above, 68 percent of transit operators surveyed by APTA believe that transit agencies have some responsibility to address homelessness. However, only five percent reported having resources dedicated to the issue (Bell et al., Citation2018). Similarly, Boyle (Citation2016) found that many transit agencies are concerned with behavioural issues of unhoused people who congregate on vehicles or in transit centres, and that lack of funding and resources, in combination with the extent of homelessness, represents a top challenge. Additionally, more than half of the agencies surveyed noted the need to balance customer concerns about unhoused riders with humane actions towards them; they also emphasized the need for staff training, and support from city and county governments. Similar to other public entities, transit agencies have been taking actions to address homelessness on their systems, mostly relying on a combination of punitive and outreach measures () and often through partnerships with outside agencies and organisations (Boyle, Citation2016).

Table 3. Transit Agencies’ Responses to Homelessness.

Data sources: (Bassett et al., Citation2013; Bell et al., Citation2018; Boyle, Citation2016; Loukaitou-Sideris et al., Citation2020)

Punitive Responses

Scholars have observed a general trend of increasing criminalisation of homelessness over the last three decades; transit environments are no exception. Broadly, this has entailed the adoption of ordinances restricting activities associated with homelessness (such as camping, loitering, and panhandling), more intensive policing, and the use of hostile architecture in public spaces (Ehrenfeucht & Loukaitou-Sideris, Citation2014) (). For example, a number of municipalities have enacted since the early 1990s “sit-lie” ordinances, which prohibit individuals from lingering, sitting, or sleeping in public spaces (including bus stops and station platforms). These often exclude and punish those experiencing homelessness for using public spaces in non-conforming ways, such as sleeping in the rough or sitting on the sidewalk. According to Amster (Citation2003), the ultimate aim of criminalising homelessness in public spaces is to sanitise such spaces. He argues that policymakers justify these strategies in the mainstream media through the demonisation of homelessness and its association with disease, and instigate anti-homeless regulations and law enforcement methods that punish and remove unhoused individuals from public spaces. Hall (Citation2017) further argues that sanitisation and cleansing of public spaces are deemed necessary for the reinvestment and redevelopment of previously deteriorating inner-cities but have substantially contracted the spaces that remain open to the unhoused population.

Table 4. Punitive Responses to Homelessness

Rose (Citation2017) documents the use of a public health narrative by local governments and private entities, such as BIDs, that embodies both material and social connotations of cleanliness and health in order to criminalise and displace unhoused individuals from public spaces. Turner, Funge, and Gabbard (Citation2018, december 2) argue that the criminalisation of homelessness is caused by public perceptions that tend to blame homeless individuals for their misfortune. They make a case to instead recognise the structural causes of homelessness and to shift policies towards addressing the needs of the unhoused population, reducing their criminalisation. The 2019 federal circuit court ruling in Martin v. Boise, which the U.S. Supreme Court let stand, makes it more difficult for cities to enforce absolute bans on unsheltered individuals sleeping or camping in public space, in the absence of alternative housing arrangements. Nevertheless, cities have continued to remove their unhoused population from public spaces, often against their will, and sending them to night-shelters. Punitive responses to homelessness encompass intensified encampment sweeps, involuntary commitment into mental health institutions, and forced segregation in mass shelters (Rankin, Citation2021).

Similar to municipal departments, many transit operators also seek to remove unhoused people from their systems. In both 2016 and 2020, around forty percent of agencies surveyed reported periodically conducting sweeps of transit environments where unhoused people congregate. Over those four years, the share of transit operators that require riders to exit the vehicle at the end of the line and pay an additional fare to board again rose from 36 percent to 67 percent (Boyle, Citation2016; Loukaitou-Sideris et al., Citation2020). Beyond transit, removal of unhoused people and encampments from rights-of-way is a common approach adopted by departments of transportation in many states, but in most cases such actions only serve as a temporary “solution” until those displaced or others return (Bassett et al., Citation2013).

Along with other overt means of criminalising homelessness in public space, the employment of law enforcement by municipalities, BIDs, and transit agencies has also intensified in more subtle ways. In the 1980s and 1990s, efforts by the police to address homelessness had a strong public safety emphasis, as they often dispersed homeless encampments, issued citations, and made arrests. Scholars have criticised such actions as ineffective, only dispersing or displacing rather than addressing homelessness (Berk & MacDonald, Citation2010; Hartmann McNamara, Crawford, & Burns, Citation2013). In later years, police have begun to rely more on “move along” orders, confiscation of properties, threats of arrests, and involuntary psychiatric commitments (Goldfischer, Citation2020; Herring, Citation2019). While many police officers do not believe that their role is to address the problem of homelessness, according to a survey by Hartmann McNamara et al. (Citation2013), they oftentimes interact with unhoused individuals in response to complaints from third parties. They may thus employ less directly confrontational enforcement strategies as part of what Herring (Citation2019) refers to as “burden shuffling”—the displacement of the unhoused both spatially and bureaucratically into the remit of other government departments. Nevertheless, this seemingly less violent approach often punishes people experiencing homelessness for their visibility in public space, and through a constant and pervasive process, inflicts material, psychological and social suffering (Goldfischer, Citation2020; Herring, Citation2019).

Under the threat of COVID-19 infection, the dispersal of homeless encampments from public rights-of-way like transit property was temporarily suspended in some places. In response to guidelines by the U.S. Center of Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to “allow people who are living unsheltered or in encampments to remain where they are,” (CDC, Citation2020), many state departments of transportation have refrained from removing homeless encampments during the pandemic (Falsetti, Citation2020; Stradling, Citation2021; Wiltz, Citation2020).

In addition to policing, another common, albeit more covert strategy, that cities and transit agencies employ is the use of “hostile architecture” in public spaces and transit—the arrangement of space and the use of materials that make sitting or lying uncomfortable or impossible. Hostile architecture often complements exclusionary ordinances and regulations. The installation of benches with high middle armrests in parks, transit stops, and station platforms or the addition of spikes or metal studs on ledges, make it difficult for unhoused people to use these spaces to sleep or rest (de Fine Licht, Citation2017, november 14; Petty, Citation2016; Rosenberger, Citation2017). Hostile architecture has faced criticism for being used to selectively design some population groups out of public spaces by making these spaces less hospitable for them and their activities (Johnsen, Fitzpatrick, & Watts, Citation2018; Petty, Citation2016; Rosenberger, Citation2017). Scholars also emphasize the intention of discipline and social control underlying the use of hostile architecture and the fact that it results in displacement instead of addressing the social problem of homelessness (Johnsen et al., Citation2018; Rosenberger, Citation2017, Citation2020; Smith & Walters, Citation2018). Our survey found that about half of the surveyed transit agencies employed hostile architecture by installing structural elements or landscaping to discourage sleeping at stops or stations (Loukaitou-Sideris et al., Citation2020). While other studies of transit agencies’ response to homelessness do not mention such design practices, Rosenberger (Citation2017) observes that benches with middle armrests, a typical element of hostile architecture, are often found in transit stops.

The 2016 TCRP survey found that punitive measures constitute a significant part of transit agencies’ responses: 63 percent of transit agencies enforced such laws, and 69 percent partnered with local law enforcement agencies (Boyle, Citation2016). Our 2020 survey found that about half of the responding agencies enforce on their system municipal anti-homeless ordinances such as those prohibiting loitering and panhandling (Loukaitou-Sideris et al., Citation2020). As the latter survey took place during the COVID-19 pandemic, this reduction may relate to the particular circumstances of the pandemic, but it may also indicate changing attitudes and policies.

Though detailed empirical evidence on the prevalence and efficacy of punitive measures taken by transit agencies is scant, such methods are part of a broader, more well-studied trend of enforcement to address homelessness in public spaces. The policing of unhoused people in transit systems parallels law enforcement efforts undertaken by BIDs that also heavily rely on anti-loitering and anti-panhandling laws and regulations and often result in citations and confiscation of personal property (Glyman, Citation2016; Herring, Citation2019). Enforcement actions specific to transit agencies include banning the carrying of large bags and backpacks on transit vehicles and requirements that all passengers disembark from vehicles at the end of transit routes (Loukaitou-Sideris et al., Citation2020).

Outreach Responses

In contrast to punitive measures, studies indicate that outreach is a more effective approach to addressing homelessness. This is also supported by ample empirical evidence on the positive effects of outreach efforts on housing and health outcomes for unhoused people (de Vet et al., Citation2013; Munthe-Kaas, Berg, & Blaasvær, Citation2018; Olivet, Bassuk, Elstad, Kenney, & Jassil, Citation2010; O’Shaughnessy & Greenwood, Citation2020). Indeed, studies find that training programmes such as crisis intervention training and collaborations with shelters and mental health agencies are important factors for successful outreach (Hipple, Citation2017; Turner, Citation2019).

Only limited literature exists on the outreach strategies of transit agencies. Thus, studies on how other entities reach out to support individuals experiencing homelessness are illustrative. Public libraries, police departments, and BIDs often have various outreach programmes to link unhoused individuals to social services (Giesler, Citation2017; Hipple, Citation2017; Lee, Citation2018). In parallel with transit agencies, these entities all interact with unhoused individuals on a daily basis.

For example, staff in public libraries work with people experiencing homelessness, who often use libraries as makeshift shelters or shelter extensions to spend their day and access technology and services (Giesler, Citation2017, Citation2019). Since the 2010s, public libraries have acted to accommodate the unhoused population and remove barriers for them to access library resources, offering information and training services and programmes tailored to their needs. Many libraries also connect unhoused patrons to shelters and other resources via outreach partnerships with social service agencies (American Library Association, Citation2012; Hill, Citation2011; Terrile, Citation2016; Willett & Broadley, Citation2011).

Still, public library staff face significant challenges, such as lack of training on how to best engage with different unhoused people and lack of formalised partnerships with shelters and other social services (Giesler, Citation2017, Citation2019). A recent case study (T. Hill & Tamminen, Citation2020) examined a partnership among public libraries, city governments, social services, nonprofit organisations, and universities in Mississauga, Ontario (Canada), which established a community hub in the library for unhoused individuals to receive help from an outreach worker on how to access resources. The study reveals the importance of collaboration among disparate agencies and organisations, as well as the critical role of a central liaison (the outreach worker in this case) in facilitating such collaborations and connecting unhoused people to resources and services.

Some law enforcement agencies have also begun using outreach- and engagement-based strategies in their encounters with people experiencing homelessness—often through collaboration with social service providers and by giving specialised training to their officers. In fact, some police departments (such as, for instance, the Indianapolis Metropolitan Police Department) have initiated efforts to refrain from arresting unhoused people and seek to connect them to treatment and assistance (Hipple, Citation2017; Turner, Citation2019; Turner et al., Citation2018, december 2).

BID staff and businesses also experience frequent interactions with unhoused individuals. A study of BID responses to homelessness in Washington, D.C. found that many BIDs have started pursuing a combined approach that encompasses not only law enforcement but also outreach activities (Lee, Citation2018). Follow-up interviews with BID staff in the same study revealed that BIDs can address homelessness in a sensitive and engaged manner that offers services and support to the unhoused population through partnerships with social service agencies (Lee, Citation2018).

Many transit agencies also implement outreach measures that either provide assistance and resources to those experiencing homelessness or at least ensure that their interactions with unhoused riders are more sensitive (). Additionally, as providers of a public service, some transit agencies have programmes to lower or remove barriers for unhoused travelers to access their service. These include free or heavily discounted transit tickets, which are often distributed though shelters and social service providers (Boyle, Citation2016; Loukaitou-Sideris et al., Citation2021). Some agencies, such as Metro Transit in Madison, Wisconsin, have also specifically provided transportation to or between shelters during the pandemic or extreme weather events (Loukaitou-Sideris et al., Citation2021). Moreover, around four in ten agencies have training programmes for front-line employees to prepare them for interactions with unhoused riders (Boyle, Citation2016; Loukaitou-Sideris et al., Citation2020). During the pandemic, a number of U.S. transit agencies have suspended fare collection or paused fare inspection to reduce the risk of virus transmission. In our survey, these agencies were more likely to report increased homelessness on their systems than agencies which did not suspend fare collection or inspection, but differences in enforcement explained the correlation, rather than the change in the listed fare price itself. (Loukaitou-Sideris et al., Citation2020).

Because homelessness is a social problem, which cannot be addressed fully by one public entity, outreach programmes tend to be administered through external partnerships. This is especially true given how few transit agencies have dedicated budget items or outside funding for homelessness efforts (Loukaitou-Sideris et al., Citation2020). These collaborations focus on connecting people experiencing homelessness to the broader social service system, beyond what transit agencies directly administer, which can better deliver assistance and support. Boyle (Citation2016) found that 71 percent of transit agencies partnered with social service or nonprofit agencies on outreach efforts. Other common partners include the city and county police, and homeless shelters. Our survey, distributed five years later than Boyle’s (Citation2016), revealed a shift to even more outreach and partnership strategies (Loukaitou-Sideris et al., Citation2020).

The Hub of Hope, a walk-in outreach center in a Philadelphia transit center, represents an exemplar partnership between a transit agency (the Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority (SEPTA)), law enforcement, and a nonprofit organisation (Project HOME) (Loukaitou-Sideris et al., Citation2021). Its apparent success parallels that of public libraries that have set up similar programmes and collaborations (Hill & Tamminen, Citation2020). But unlike public libraries that closed down during the pandemic, the Hub remained open, albeit reducing its hours of daily operations and the provision of some services (Loukaitou-Sideris et al., Citation2021). Another well-developed partnership takes place in the San Francisco Bay Area, where multiple transit agencies, local governments, and nonprofits collaborate on a multipronged strategy, including homeless outreach teams of social workers, automated “pit stop” bathrooms, elevator attendants, transit ambassadors, and crisis intervention team training for police officers (Boyle, Citation2016; Loukaitou-Sideris et al., Citation2021; Powers, Citation2019).

summarises different outreach and support strategies and their main purposes.

Table 5. Outreach and Supportive Responses to Homelessness

Evaluation of Responses

Very few studies have attempted to evaluate the effectiveness of transit agencies’ responses to homelessness, and most of them are case studies of singular interventions. For instance, Rudy and Delgado (Citation2006) reported on an initiative in Orange County, California that involved police, bus drivers, and mental health professionals on hotspot routes and resulted in more unhoused people receiving services and fewer customer complaints. The few existing case studies of partnerships and other outreach response measures conclude that forging strong partnerships with external stakeholders like social service agencies, hiring dedicated staff for homelessness response, crafting policies to target behaviours rather than groups or individuals, and routing to serve social service destinations are best practices (Bell et al., Citation2018; Boyle, Citation2016; Loukaitou-Sideris et al., Citation2021).

A 2020 audit of the outreach programme on New York City’s subway, carried out through a partnership between New York City’s Department of Homeless Services, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA), and the Bowery Residents’ Committee, a nonprofit homeless service provider, found that the programme failed to meet its original targets of reducing homeless counts in the system. There was a lack of oversight and monitoring, and data on outreach outcomes, such as placement in shelters, were unverified and unreliable (New York State Comptroller, Citation2020). In another recent study, Dembo (Citation2020) evaluated Los Angeles Metro’s homeless outreach programmes, many of which are contracted out to the service provider People Assisting the Homeless (PATH) and three police departments; the PATH teams were more cost-effective, referred more unsheltered individuals to social services, and secured housing for a greater share of them, as compared to the police teams. Both these studies sought to evaluate the success of outreach programmes, but each used different metrics, which partly explains the different outcomes of evaluation. The MTA audit inquired whether the programme was able to achieve preset targets in reducing homeless counts, whereas the evaluation of LA Metro’s programmes focussed on the relative success of the different programmes in terms of referrals and cost-effectiveness. Such differences in evaluation metrics reflect the ambiguity of how success can be defined, by different stakeholders and from different perspectives, which is among the biggest challenges for assessing and evaluating transit agencies’ efforts to address homelessness.

In both Boyle’s (Citation2016) and our (2020) surveys, most transit agencies rated their responses as “somewhat successful” or “neutral,” with few deeming them either as “very successful” or “unsuccessful.” However, the reasons behind these self-assessed ratings may vary widely. The three most cited reasons in Boyle’s (Citation2016) survey for deeming a response as “successful” were that unhoused people and other customers were treated equally, that good relationships were forged with partnering agencies, and that the agency had done a reasonable job with the few resources available. These reasons, though, do not actually reflect the effectiveness of agencies’ strategies at producing tangible positive outcomes for agency performance or meeting the needs of the unhoused. The first cited reason comes closest, though it is hard to quantify, and equates equal treatment with good treatment; the second reason may at best be deemed as a positive by-product of efforts to address homelessness, rather than an evaluation of whether the objectives of such partnerships are met; and the third is more of a reflection on why some measures cannot achieve greater success than an assessment of actual outcomes.

As for barriers to success, frequently cited limitations include resource and funding constraints; aspects of the unhoused population like their appearance, personal hygiene and unwillingness or inability to accept help; and critically, the belief that transit agencies can only deliver some temporary fixes rather than address the underlying issues of homelessness (Boyle, Citation2016). As noted above, such a belief is also common among the police (Hartmann McNamara et al., Citation2013; Herring, Citation2019). Thus, it seems that transit agencies often find themselves in a dilemma. On one hand, they worry about their ridership being affected by homelessness and feel motivated to take actions to address the issue. On the other, they are impeded by lack of funding and resources and also conclude that even if they do take some measures to respond to homelessness on their systems, their efforts are not likely to yield significant successes.

The few studies that evaluate responses to homelessness do so from the perspective of transit agencies. No research we could find has evaluated transit agencies’ responses from the perspective of people experiencing homelessness, but a couple of studies that evaluated responses in other sectors may serve as helpful references. For example, a study that interviewed people experiencing homelessness about their encounters with police found that they tended to feel that officers harassed them and constrained their movement and activities rather than offering help (Hartmann McNamara et al., Citation2013). People experiencing homelessness view even certain outreach efforts, like those provided through partnerships between BIDs and social services, as surveillance and harassment instead of assistance and support (Selbin et al., Citation2018). The lack of trust among unhoused people towards the police, BIDs, and even social service agencies and transit agencies underscores the difficulty of outreach efforts and the importance of training programmes for those charged with engaging with unhoused people.

Conclusion

Through our search and analysis of prior studies, we have synthesised the literature on homelessness in transit environments seeking to understand three particular topics, each understudied and not often examined together: 1) the extent of the challenge; 2) the travel patterns of unhoused individuals and the importance of transit services for them; and 3) the strategies that transit agencies follow to address homelessness on their systems and respond to the needs of their unhoused riders.

The limited literature that exists on the first topic is primarily based on surveys of transit operators around the country and presents the perceptions of their staff about the extent of the homelessness challenge. Largely missing are counts of unhoused individuals and their spatial concentrations, as well as their perceptions of the challenges they are facing. Additionally, the literature is not clear about the impacts of homelessness on transit agency resources, operations, and ridership. This lack of knowledge and ambiguity are problematic, as they may hinder the crafting of targeted policy responses.

The literature on the travel patterns of people experiencing homelessness, which draws from focus groups, interviews, and surveys of them, univocally points to the importance of transit services for unhoused individuals. This part of the literature is better developed, though rarely put in an aggregate context. These studies show that public transit is a common mobility option and a critical public good for those experiencing homelessness. It is, therefore, important that transit systems connect to the locations to which they travel disproportionately, such as social services, shelters, food banks, healthcare, etc. Some of these destinations may not be where housed transit riders (who typically outnumber their unhoused peers) usually travel, but transit agencies should value, not discount, the travel needs of all their riders. Doing so may involve incorporating the knowledge and input of riders experiencing homelessness themselves, and also their advocates and service providers, in transit service planning.

We found few studies on the strategies that transit agencies employ in response to homelessness, and for this reason we also reviewed literature on the responses of other public and private entities (such as libraries, BIDs, and law enforcement agencies) that also interact with unhoused individuals. We found that the responses of most transit agencies involve both punitive and outreach strategies. The literature indicates a growing awareness that law enforcement alone can only temporarily remove or displace homelessness rather than address the structural issues causing homelessness. Thus, outreach efforts at agencies, which offer assistance and support to people experiencing homelessness or at least connect them to resources offered elsewhere, are critical. As the social movement to reallocate funding and responsibilities away from armed police grows in the U.S.—and as unhoused transit riders face continued violence from police for their use of public space (e.g. Russo, Citation2020)—we note that existing research shows little to no evidence for the long-term efficacy of law enforcement efforts towards those experiencing homelessness. The most successful strategies instead involve unarmed, trained, civilian staff.

Given the realisation that homelessness is a wider societal problem, collaboration between agencies and organisations that often encounter homelessness is on the rise. These various partnerships include transit agencies, public libraries, BIDs, police, and agencies and organisations that support the unhoused population, such as social services, shelters, and nonprofits. However, we see a need for more research on how these partnerships are formed and sustained.

We also found a general lack of evaluative studies and few clear metrics on how to measure the effectiveness of response efforts. Both practitioners and researchers should pursue more before-and-after studies, more data-driven evaluations, and better monitoring and systematic assessment of transit agency efforts. This is especially necessary given that many transit agencies often conduct both law enforcement and outreach activities through partnerships with outside organisations. In structuring such external relationships, agencies can and should both quantify and operationalise metrics such as homeless counts, numbers of referrals made, numbers of homeless individuals engaged through outreach programmes, or numbers of people ultimately sheltered or housed.

Homelessness in transit systems is prevalent in many U.S. and Canadian cities and also visible (though even less studied) in some European cities. Transit agencies have a social responsibility to ensure that their services are easily accessible to their unhoused riders and also help these riders access assistance and support. Documenting their experiences and needs and learning from other agency responses and best practices are important steps towards this goal.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 For comparison, Berlin (population: 3.77 million) had 1,976 unhoused individuals in the city in 2020, pre-pandemic, while the similarly-sized City of Los Angeles (population: 3.98 million) had 41,290 unhoused individuals in 2020, also pre-pandemic (Berlin-Brandenburg Office of Statistics, Citation2020; Strauß, Citation2020; U.S. Census Bureau, Citation2021; LAHSA, Citation2020).

References

- American Library Association. (2012). Extending Our Reach: Reducing Homelessness through Library Engagement. American Library Association. Retrieved October 1, 2020, from https://alair.ala.org/bitstream/handle/11213/8694/poorhomeless_FINAL.pdf

- Amster, R. (2003). Patterns of exclusion: Sanitizing space, criminalizing homelessness. Social Justice, 30(91), 195–221. Retrieved October 1, 2020, from https://www.jstor.org/stable/29768172

- Bassett, E., Tremoulet, A., & Moe, A. (2013, July). Relocation of Homeless People from ODOT Rights-of-way (OTREC-RR-12-14). Oregon Transportation Research and Education Consortium. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.15760/trec.67

- Bell, L., Beltran, G., Berry, E., Calhoun, D., Hankins, T., & Hester, L. (2018, September 19). Public Transit and Social Responsibility: Homelessness (Leadership APTA). APTA. Retrieved October 8, 2020, from https://www.apta.com/wp-content/uploads/Transit_Responses_Homeless/REPORT-2018-Leadership-APTA-Team-4-Public-Transit-and-Social-Responsibility.pdf

- Berk, R., & MacDonald, J. (2010). Policing the homeless: an evaluation of efforts to reduce homeless-related crime. Criminology and Public Policy, 9(4), 813–840. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9133.2010.00673.x

- Berlin-Brandenburg Office of Statistics. (2020). Demographic Data. Berlin Business Location Center. Retrieved February 9, 2021, from https://www.businesslocationcenter.de/en/business-location/berlin-at-a-glance/demographic-data/

- Boyd, M., Maier, M., & Kenney, P. (1996, June). Perspectives on Transit Security in the 1990s: Strategies for Success (FTA-MA-90-7006-96-1 and DOT-VNTSC-FTA-96-2). Volpe Center. Retrieved October 8, 2020, from https://www.transit.dot.gov/oversight-policy-areas/perspectives-transit-security-1990s-strategies-success-june-1996

- Boyle, D. (2016, March 14). Transit Agency Practices in Interacting with People who Are Homeless (TCRP Synthesis 121). Transportation Research Board. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.17226/23450

- Busch-Geertsema, V. (2006, October). Urban Governance, Homelessness and Exclusion. Homelessness and Access to Space in Germany. European Observatory on Homelessness, FEANTSA. Retrieved January 22, 2021, from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/238083501_Urban_Governance_Homelessness_and_Exclusion_Homelessness_and_Access_to_Space_in_Germany

- CDC. (2020, August 6). Interim Guidance on Unsheltered Homelessness and Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) for Homeless Service Providers and Local Officials. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved February 8, 2021, from https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/community/homeless-shelters/unsheltered-homelessness.html

- Council of Economic Advisers. (2019, September). The State of Homelessness in America. Council of Economic Advisers. Retrieved October 7, 2020, from https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/The-State-of-Homelessness-in-America.pdf

- Crisis. (2018, December 14). More Than 24,000 People Facing Christmas Sleeping Rough or in Cars, Trains, Buses and Tents, Crisis Warns. Crisis. Retrieved February 9, 2021, from https://www.crisis.org.uk/about-us/media-centre/more-than-24-000-people-facing-christmas-sleeping-rough-or-in-cars-trains-buses-and-tents-crisis-warns/

- de Fine Licht, K. ((2017, November 14). Hostile urban architecture: A critical discussion of the seemingly offensive Art of Keeping people away. Etikk i Praksis: Nordic Journal of Applied Ethics, 11(2), 27–44. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5324/eip.v11i2.2052

- Dembo, M. (2020). Off the Rails: Alternatives to Policing on Transit (MURP Applied Planning Research Project). UCLA, Los Angeles. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.17610/T6XK56

- de Vet, R., van Luijtelaar, M., Brilleslijper-Kater, S., Vanderplasschen, W., Beijersbergen, M., & Wolf, J. ((2013, October). Effectiveness of case Management for homeless persons: A systematic review. American Journal of Public Health, 103(10), e13–e26. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2013.301491

- Ehrenfeucht, R., & Loukaitou-Sideris, A. (2014). The irreconcilable tension between dwelling in public and the regulatory state. In V. Mukhija, & A. Loukaitou-Sideris (Eds.), The informal American city: Beyond taco trucks and day labor. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press (pp. 155–172). Retrieved April 18, 2020, from https://mitpress.mit.edu/books/informal-american-city

- Falsetti, R. (2020, July 14). Unsheltered Encampments—COVID-19 Project Effects [Memorandum]. Retrieved March 8, 2021, from https://dot.ca.gov/-/media/dot-media/programs/construction/documents/policies-procedures-publications/cpd/cpd20-17.pdf

- Giesler, M. (2017, October 2). A place to call home?: A qualitative exploration of public librarians’ response to homelessness. Journal of Access Services, 14(4), 188–214. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15367967.2017.1395704

- Giesler, M. (2019, January 2). The collaboration between homeless shelters and public libraries in addressing homelessness: A multiple case study. Journal of Library Administration, 59(1), 18–44. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01930826.2018.1549405

- Glyman, A. (2016). Blurred Lines: Homelessness and the Increasing Privatization of Public Space (S. Rankin, Ed.). Homeless Rights Advocacy Project, Seattle University School of Law. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2776876

- Goldfischer, E. (2020). From encampments to hotspots: The changing policing of homelessness in New York city. Housing Studies, 35(9), 1550–1567. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2019.1655532.

- Guo, J. (2017). Barriers for Homeless People in San Jose when Accessing Valley Transportation Authority (VTA)’s Transit Service (Master of Urban Planning Planning Report). SJSU. Retrieved October 2, 2020, from https://www.inist.org/library/2017-05.Guo.Barriers%20for%20Homeless%20People%20in%20San%20Jose%20when%20Accessing%20VTA%27s%20Transit%20Service.SJSU%20Urban%20and%20Regional%20Planning.pdf

- Guse, C. (2020, April 21). NYC Homeless Turn to Subway during Coronavirus Crisis. New York Daily News. Retrieved October 2, 2020, from https://www.nydailynews.com/coronavirus/ny-coronavirus-homeless-population-subway-fires-mta-20200421-vr26xwjowzce7hrpimfghrdxxy-story.html

- Hall, T. (2017). Citizenship on the edge: Homeless outreach and the city. In H. Warming, & K. Fahnøe (Eds.), Lived Citizenship on the edge of society: Rights, belonging, intimate life, and spatiality . London: Palgrave Macmillan (pp. 23–44). Retrieved October 1, 2020, from https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007%2F978-3-319-55068-8.pdf

- Hartmann McNamara, R., Crawford, C., & Burns, R. (2013, January 1). Policing the Homeless: policy, practice, and perceptions. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies and Management, 36(2), 357–374. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/13639511311329741

- Herring, C. (2019, September 5). Complaint-oriented policing: Regulating homelessness in public space. American Sociological Review, 84(5), 769–800. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122419872671

- Hill, N. (2011, December). Public libraries and the homeless. Public Libraries, 50(6), 13–22. Retrieved October 1, 2020, from http://publiclibrariesonline.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/November-December-2011-Perspectives-on-Serving-Homeless.pdf

- Hill, T., & Tamminen, K. (2020, July 3). Examining the Library as a site for intervention: A mixed-methods Case Study evaluation of the “innovative solutions to homelessness” project. Journal of Library Administration, 60(5), 470–492. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01930826.2020.1729626

- Hipple, N. (2017, March). Policing and homelessness: Using partnerships to address a cross system issue. Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice, 11(1), 14–28. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/police/paw010

- Homeless Alliance of Western New York. (2006, September). Left Behind: How Difficulties with Transportation Are a Roadblock to Self-Sufficiency. Homeless Alliance of Western New York. Retrieved October 2, 2020, from https://ppgbuffalo.org/files/documents/environment/transit/environment-_left_behind.pdf

- Hui, V., & Habib, K. (2016). Transportation-Related Social Exclusions and homelessness: What does the Role of Transportation play in Improving the Circumstances of homeless individuals. 95th Annual Meeting of the Transportation Research Board, 2664, 1–19. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/284452343_Transportation_Related_Social_Exclusions_and_Homelessness_What_Does_the_Role_of_Transportation_Play_in_Improving_the_Circumstances_of_Homeless_individuals

- Hui, V., & Habib, K. (2017). Homelessness Vis-à-vis transportation-induced Social Exclusion: An econometric investigation of travel Behavior of homeless individuals in toronto, Canada. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board, 2665(1), 60–68. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3141/2665-07

- Jaffe, G., & Gowen, A. (2020, April 13). The High Price of Keeping Detroit Moving: Michigan Has Among the Highest Number of COVID-19 Deaths in the Country. Transit Workers Say They’re Unfairly Put at Risk. Washington Post. Retrieved October 2, 2020, from https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/2020/national/detroit-coronavirus/

- Jocoy, C., & Del Casino, V. (2008, February). The Mobility of Homeless People and Their Use of Public Transit in Long Beach, California (METRANS Project # 06-13). METRANS Transportation Center. Retrieved October 2, 2020, from https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Vincent_Del_Casino/publication/266864914_The_Mobility_of_Homeless_People_and_Their_Use_of_Public_Transit_in_Long_Beach_California/links/55dcefcc08ae591b309abcc2/The-Mobility-of-Homeless-People-and-Their-Use-of-Public-Transit-in-Long-Beach-California.pdf

- Jocoy, C., & Del Casino, V. (2010, August 1). Homelessness, Travel Behavior, and the politics of Transportation mobilities in Long Beach, california. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 42(8), 1943–1963. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1068/a42341

- Johnsen, S., Fitzpatrick, S., & Watts, B. (2018, October 3). Homelessness and social control: A typology. Housing Studies, 33(7), 1106–1126. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2017.1421912

- LAHSA. (2020, June 12). 2020 Greater Los Angeles Homeless Count Results. Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority. Retrieved February 9, 2021, from https://www.lahsa.org/news?article=726-2020-greater-los-angeles-homeless-count-results

- Laughlin, J., & Madej, P. (2020, June 18). Between Feces and Bodily Fluids, the Coronavirus Makes SEPTA’s Dirtiest Jobs Even Tougher. Philadelphia Inquirer. Retrieved October 2, 2020, from https://www.inquirer.com/transportation/coronavirus-septa-shortages-dirty-jobs-workers-cleaners-20200618.html

- Lee, W. (2018, January 1). Downtown Management and homelessness: The versatile roles of business Improvement districts. Journal of Place Management and Development, 11(4), 411–427. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/JPMD-06-2017-0052

- Legler, M. (2019). Hennepin County Unsheltered Point-in-time Count for July 24, 2019. Hennepin County Office to End Homelessness and St. Stephen’s Human Services. Retrieved January 7, 2021, from https://www.hennepin.us/-/media/hennepinus/your-government/projects-initiatives/end-homelessness/unsheltered-report-jul-2019.pdf

- Legler, M. (2020). Aug 13, 2020 [Personal communication].

- Loukaitou-Sideris, A., Wasserman, J., Caro, R., & Ding, H. (2020). Homelessness in Transit Environments: Volume I, Findings from a Survey of Public Transit Operators (UC-ITS-2021-13). UCLA ITS. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.17610/T6V317

- Loukaitou-Sideris, A., Wasserman, J., Caro, R., & Ding, H. (2021). Homelessness in Transit Environments: Volume II, Transit Agency Strategies and Responses. UCLA ITS. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.17610/T6JK5S

- Mahs, J. (2005, April 1). The sociospatial Exclusion of single Homeless People in Berlin and Los Angeles. American Behavioral Scientist, 48(8), 928–960. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764204274201

- Meyerhoff, A., Micozzi, M., & Rowen, P. (1993). Running on empty: Travel patterns of extremely poor people in Los Angeles. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board, 1395, 153–160. Retrieved October 5, 2020, from http://onlinepubs.trb.org/Onlinepubs/trr/1993/1395/1395-020.pdf

- Munthe-Kaas, H., Berg, R., & Blaasvær, N. (2018). Effectiveness of Interventions to reduce homelessness: A Systematic Review and meta-analysis. Campbell Systematic Reviews, 14(1), 1–281. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4073/csr.2018.3

- Murphy, E. (2019, July 3). Transportation and homelessness: A Systematic review. Journal of Social Distress and the Homeless, 28(2), 96–105. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10530789.2019.1582202

- New York State Comptroller. (2020, January 16). Homeless Outreach Services in the New York City Subway System (2018-S-59). New York State Comptroller. Retrieved April 19, 2021, from https://www.osc.state.ny.us/files/state-agencies/audits/pdf/sga-2020-18s59.pdf

- Nichols, L., & Cázares, F. (2011, April). Homelessness and the mobile shelter system: Public Transportation as shelter. Journal of Social Policy, 40(2), 333–350. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047279410000644

- Olivet, J., Bassuk, E., Elstad, E., Kenney, R., & Jassil, L. (2010, March 22). Outreach and Engagement in Homeless Services: A review of the literature. Open Health Services and Policy Journal, 3(1), 53–70. Retrieved October 1, 2020, from https://benthamopen.com/ABSTRACT/TOHSPJ-3-53

- O’Shaughnessy, B., & Greenwood, R. (2020, September). Empowering features and outcomes of homeless interventions: A Systematic Review and narrative synthesis. American Journal of Community Psychology, 66(1–2), 144–165. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp.12422

- Petty, J. (2016, March 1). The London Spikes controversy: Homelessness, Urban securitisation, and the question of “Hostile architecture. International Journal for Crime, Justice, and Social Democracy, 5(1), 67–81. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5204/ijcjsd.v5i1.286

- Powers, B. (2019, June). Quality of Life Initiative. Presented at the APTA Rail Conference, Toronto. Retrieved April 18, 2020, from https://www.apta.com/wp-content/uploads/Transit-Agency-Interactions-with-People-Who-Are-Homeless_Bob-Powers.pdf

- Rankin, S. (2021). Hiding homelessness: The transcarceration of homelessness. California Law Review, 109(2), 1–55. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3499195

- Rose, J. (2017, September 27). Cleansing public nature: Landscapes of homelessness, health, and displacement. Journal of Political Ecology, 24(1), 11–23. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2458/v24i1.20779

- Rosenberger, R. (2017). Callous objects: Designs against the homeless. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Rosenberger, R. (2020, March 1). On Hostile design: Theoretical and empirical prospects. Urban Studies, 57(4), 883–893. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098019853778

- Rudy, J., & Delgado, A. (2006). Homelessness and Problems It Presents to the Orange County Transportation Authority: A Social Approach to a Social Problem. Presented at the APTA Bus and Paratransit Conference, Orange County. Retrieved April 17, 2020, from https://trid.trb.org/view/793108

- Russo, M. (2020, July 15). NYPD Cop Seen Punching, Choking, Macing Homeless Subway Rider in Arrest Video: In the Disturbing Clip, Transit Officers Are Seen Hitting and Dragging a Man Off a Nearly Empty 6 Train Car who They Accused of Taking Up Two Seats, Leaving Him Crying, Bloody, and Fearing for His Life. NBC New York. Retrieved October 9, 2020, from https://www.nbcnewyork.com/news/local/nypd-officer-seen-punching-choking-macing-homeless-subway-rider-in-violent-arrest-video/2518123/

- Ryan, D. (1991, March). No other place to go. Mass Transit, 18(3), 16–17, Retrieved October 2, 2020, from https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015026564271&view=1up&seq=76

- Schwartz, R. (1989). The end of the line: The homeless and the transportation industry. Portfolio, 2(2), 38-46, Retrieved April 17, 2020, from https://trid.trb.org/view/300779

- Schwartz, R. (1995). The Homeless—Helping Them to Find Hope. APTA Rapid Transit Conference. Presented at the APTA Rapid Transit Conference, New York City. Retrieved April 17, 2020, from https://trid.trb.org/View/522301

- Scott, H., Bryant, T., & Aquanno, S. (2020). The role of transportation in sustaining and reintegrating formerly homeless clients. Journal of Poverty, 24(7), 591–609. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10875549.2020.1740375

- Selbin, J., Campos-Bui, S., Epstein, J., Lim, L., Nacino, S., Wilhlem, P., & Stommel, H. (2018, July 27). Homeless Exclusion Districts: How California Business Improvement Districts Use Policy Advocacy and Policing Practices to Exclude Homeless People from Public Space (UC Berkeley Public Law Research Paper). UC Berkeley School of Law. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3221446

- Shinn, M. (2007). International homelessness: Policy, socio-cultural, and individual perspectives. Journal of Social Issues, 63(3), 657–677. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.2007.00529.x

- Smith, N., & Walters, P. (2018, October 1). Desire lines and defensive architecture in modern Urban environments. Urban Studies, 55(13), 2980–2995. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098017732690

- Stradling, R. (2021, February 12). NCDOT Shifts Its Approach to Clearing Homeless Camps from Along State’s Highways. Raleigh News and Observer. Retrieved March 8, 2021, from https://www.newsobserver.com/news/coronavirus/article249175285.html

- Strauß, S. (2020, February 7). Erste Ergebnisse der Obdachlosenzählung: Senatorin Breitenbach will Hilfsangebote vor Ort für obdachlose Menschen verbessern. Berlin Senate Office for Integration, Labor, and Social Affairs. Retrieved February 9, 2021, from https://www.berlin.de/sen/ias/_assets/presse/downloads/20_02_07_pm_auswertung_nds.pdf

- Terrile, V. (2016, July 2). Public Library support of families experiencing homelessness. Journal of Children and Poverty, 22(2), 133–146. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10796126.2016.1209166

- Toro, P., Tompsett, C., Lombardo, S., Philippot, P., Nachtergael, H., Galand, B., … Harvey, K. (2007, September). Homelessness in Europe and the United States: A comparison of prevalence and public opinion. Journal of Social Issues, 63(3), 505–524. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.2007.00521.x

- TransitCenter. (2020, March 24). Transit Is Essential: 2.8 Million U.S. Essential Workers Ride Transit to Their Jobs. TransitCenter. Retrieved October 2, 2020, from https://transitcenter.org/2-8-million-u-s-essential-workers-ride-transit-to-their-jobs/

- Turner, R. (2019). Law Enforcement Officers Training and the Challenges in Policing Homeless Individuals (D.M. diss.). Colorado Technical University, Colorado Springs, CO. Retrieved October 1, 2020, from https://search.proquest.com/docview/2355988627

- Turner, M., Funge, S., & Gabbard, W. (2018, December 2). Victimization of the homeless: Public perceptions, public policies, and implications for social work practice. Journal of Social Work in the Global Community, 3(1), 1-12, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5590/JSWGC.2018.03.1.01

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2021). American Community Survey. Data.census.gov. Retrieved March 25, 2020, from https://data.census.gov

- U.S. HUD. (2020, January). 2019 AHAR: Part 1—PIT Estimates of Homelessness in the U.S. HUD Exchange. Retrieved October 1, 2020, from https://www.hudexchange.info/resource/5948/2019-ahar-part-1-pit-estimates-of-homelessness-in-the-us/

- Wasserman, J. (2019). A Time and a Place for Every Rider?: Geographic and Temporal Changes in Bay Area Transit Ridership (MURP Applied Planning Research Project). UCLA, Los Angeles. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.17610/t6kw22

- Wasserman, J., Taylor, B., Blumenberg, E., Garrett, M., King, H., Paul, J., … Schouten, A. (2020, February 26). What’s behind Recent Transit Ridership Trends in the Bay Area?: Volume II, Trends among Major Transit Operators (UCLA ITS-LA1908). UCLA ITS. Retrieved February 26, 2020, from https://escholarship.org/uc/item/96w4g18f

- Wilder Research. (2019, July). Metro Transit Riders: A Special Analysis of Data from the 2018 Minnesota Homeless Study. Metro Transit.

- Willett, P., & Broadley, R. (2011, January 1). Effective public Library outreach to homeless people. Library Review, 60(8), 658–670. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/00242531111166692

- Wiltz, T. (2020, April 28). Against CDC Guidance, Some Cities Sweep Homeless Encampments. Pew. Retrieved March 8, 2021, from https://pew.org/2W4sXhq