ABSTRACT

Women in South and Southeast Asia encounter unique mobility barriers which are a combination of poor services by public transport modes and underlying patriarchal societal norms. Although international organisations provide guidelines for national policy makers to develop inclusive public transport systems, women’s mobility remains restricted and unsafe. This paper provides a critical review on women’s mobility barriers from built-environment to policy for public transport ridership. It includes three main aspects. Firstly, the key barriers encountered by women from poor service quality, sexual harassment and patriarchal societal norms. Secondly, the limitations in common methods adopted to measure these barriers. Finally, the effectiveness of international guidelines and national policies on women’s travel needs for public transport ridership. Findings revealed that women’s mobility barriers in South and Southeast Asian countries originate from the lack of adequate inclusive policies and protection laws from authorities. The underlying patriarchal societal norms form a toxic base, which allow for severe forms of sexual harassment to take place when riding public transport and for women to experience victim-blaming, if the incidents are reported. The paper concludes with knowledge gaps to assist practitioners and researchers to move toward safer journeys and development of inclusive public transport systems for women in developing countries.

1. Introduction

Public transport systems (PT) in developing countries provide unique challenges for women from the perspective of infrastructure (e.g. service quality, demand and route coverage) and patriarchal societal norms. In South and Southeast Asian countries, PT services are composed of formal services (mostly train and bus services) and informal, para-transit, services (such as rickshaws, tuk tuk, boat-taxis and motorised three-wheeler vehicles) (Gopal & Shin, Citation2019; Rahman, Citation2010; Tara, Citation2011). PT provides a common space which requires users to be in very close proximity to each other, due to over-crowded vehicles; an occurrence that is otherwise uncommon in other aspects of South Asian society where men and women are typically segregated. Most female PT riders experience some form of sexual harassments which are less common in developed countries (Ceccato, Citation2017; Lea et al., Citation2017). Rate of incidences is very high, with an estimated 90% of women having experienced harassment at least once in their lifetime (Gekoski et al., Citation2017; Women UN, Citation2017). Barriers to safe mobility hinder a woman’s progression in society by limiting their access to education, health care and employment.

In 2010, the World Bank identified that gendered mobility needs are often unknown by most government authorities (Clarke, Citation2010). Lack of disaggregate data on women’s travel needs has led to missed opportunities in planning and policy development (Thynell, Citation2016). The Asian Development Bank (ADB) published a “Gender Tool Kit” in 2013 for transportation projects in developing countries (Asian Development Bank, Citation2013b). In 2016, the United Nations (UN) launched the Sustainable Development Goal 11 to improve access for all (United Nations, Citation2016). However, these goals include only partial realisation of the barriers women face on a daily basis. Without a complete understanding of the barriers, women’s travel will remain restricted. This paper provides a critical and thought-provoking discussion on challenges encountered on PT journeys from built environment to policy.

The present study contributes to this knowledge gap and is motivated by the following questions. What are the knowledge gaps to improve women’s freedom of mobility and accessibility, in particular, for women from disadvantaged socio-economic backgrounds? With leading international organisations emphasising gender mainstreaming over the past two decades, were these initiatives and strategies successful in improving mobility for women in South and Southeast Asian countries? The review is undertaken from three aspects, including a concise discussion on the key barriers faced by women when using both formal and informal PT modes (Section 3); a review of issues and limitations of common methods (Section 4); and examining the effectiveness of international guidelines for women’s travel on national policies in South and Southeast Asian countries (Section 5). Lastly, Section 6 concludes with knowledge gaps for future research and recommendations for transport policy-makers. The outcomes are expected to assist policy-makers, planners and government organisations in developing strategic directions for an inclusive PT sector. The next section outlines the steps undertaken for a systematic literature review.

2. Methodology

Countries with common mobility barriers encountered by women in South and Southeast Asia were selected. A list of countries from the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) and Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) was attained. Bhutan and Singapore are excluded due to infrequent ridership of informal PT modes. Afghanistan is also excluded as the country has poor PT infrastructure and troubled with political instability. Countries which are selected include India, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Pakistan, Nepal, Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand, Vietnam, the Philippines, Myanmar, Brunei, Laos and Cambodia. These countries have developing economies, ridership of both formal and informal PT modes, and a common patriarchal socio-cultural background.

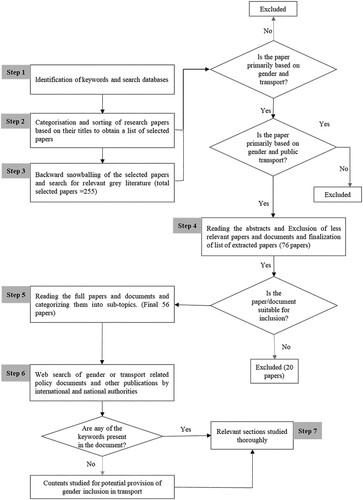

The review includes both scholarly articles and publicly available government documents related to women’s travel using PT in the selected countries. A systematic review approach was undertaken to avoid author-biases and to find a robust set of documents for review. In addition, a web-search for publicly available government transport policy documents for each of the selected countries was carried out to determine inclusion of gender needs at a national level. shows the process for both the systematic literature review (Step 1–5) and the web-search (Step 6 and 7).

Figure 1. Steps for literature review on women’s travel needs and government documents on the inclusion of gender in transport policies.

2.1. Systematic literature review

Scholarly papers were searched using mixed methods of “backward and forward snowballing” and search of keywords within the fields of “title”, “abstract” and “keywords”. The following steps outline the systematic literature review process.

Identification of keywords and searching them within the fields of “title”, “abstract” and “keywords” of well-known databases such as Scopus, Science Direct and Web of Science. The keywords used for searching papers are Boolean combinations of “public transport”, transit, travel, mobility, “para transit”, gender, women, female, harassment, violence. Searches were restricted to papers published from year 2000 onwards to capture relevant work.

Around 5917 results yielded from the search. Of them, 255 papers included the keyword “gender” and/or “transportation” in the title. Papers that included only gender, and did not focus on transportation were excluded from further review.

Studies with “gender” and “transportation” in the title were further sub-categorised into Category A which included papers based on gender inequalities in PT (including informal transport), and Category B which included papers on gender inequalities in transportation systems other than PT. Given the focus on this review is on PT, all papers in Category B were excluded from further review. All Category A papers (n = 70) carried through to the next step.

Backward and forward snowballing of Category A papers was conducted to locate any additional papers of relevance. References were checked using selected databases to capture any paper that may have been missed in Step 1. Six additional grey literatures were added to the total list of papers for review.

From the complete list of papers (n = 76), the abstracts were read to finalise the papers for full review. If a paper’s relevance was unclear from reading the abstract, a complete reading of the paper was conducted to help the authors with their decision to whether include or exclude. Twenty papers were excluded as the studies were outside the scope of the present study. The final number of papers for full review is 56.

The journal articles provided limited knowledge on local government policies. To determine any initiatives, strategies, a separate review of local and international polices was undertaken.

2.2. Web-search for public documentations on gender inclusion in transport policies

A web search was conducted for each of the selected countries (steps 6–7 in ) to examine inclusion of gender in existing policies by transport authorities, internationally and nationally for each of the selected countries. Documents since 2000 were searched for gender equality policies in government websites of transport authorities. Keywords such as “women”, “female”, “gender”; and “transport”, “public place/space” were used for the search. In absence of the keywords, contents of the transport policy documents were carefully examined for any potential provision on gender inclusion. Whereas, in presence of the keywords, the relevant sections were reviewed. Around 20 local and international documents were reviewed. Further, the search was not limited to transport policies. It was extended to other documents such as development plans, and gender action plans.

3. Mobility barriers in public transport

Mobility barriers encountered by women are exacerbated during the peak periods, due to over-crowded vehicles. Physical harassment can be almost expected during the peak periods. Most unemployed women carry out their household responsibilities outside peak periods (Gopal & Shin, Citation2019; Rahman, Citation2010; Tara, Citation2011). The complex socio-cultural norms in South and South Asian countries commonly encourage separation between men and women. This makes the close proximity in PT vehicles a unique place for interaction, including unwanted. Male passengers often adopt a patriarchal attitude towards any harassment as bystanders or even perpetrators (Adur & Jha, Citation2018; Lea et al., Citation2017; Valan, Citation2020). Women either quietly accept harassment at PT as a “normal occurrence”; take precautions such as travelling in groups; or avoid using PT when possible (Lea et al., Citation2017). Sexual harassments are often normalised by using terms such as “eve-teasing” and it remains a “regular and normal” part of PT ridership. In Islamic countries such as Pakistan, Bangladesh, Indonesia, religious restrictions on travelling with men compel women to choose more expensive non-sharing informal modes over subsidised formal PT services (Hoor-Ul-Ain, Citation2020). In rare instances when an assault is reported, women are often blamed for their clothing, time of day and place of travel (Masood, Citation2018). In an attempt to cope, most women display their martial identity by wearing vermilion (sindoor), bangles (chura), or (/and) necklace (mangal sutra) and wear conservative and culturally acceptable clothing (Neupane & Chesney-Lind, Citation2014). Patriarchal societal norms limit women’s freedom of travel using PT and contribute to their experience of sexual harassment. In addition, there have been a number of cases on harassment and violence against women by drivers of privately owned services such as Uber. Recently, in Nepal, electric tempos (Safas) are mostly operated by female drivers to counter this barrier (Regmi & Yamamoto, Citation2021).

Poor PT services create additional barriers for women. These include, but not limited to, over-crowded vehicles and platforms, delays, poorly designed interchanges, and inconsistent cost of travelling with informal modes (normally set by negotiation between driver and passenger). It is common for informal mode drivers to charge more during off-peak periods. This disproportionately affects women as they prefer to travel during off-peak hours (Tarigan et al., Citation2014). Most women do not have an alternative choice and need to make multiple trip-chains using informal modes despite the proportionately higher cost in comparison to formal modes (Mahadevia & Advani, Citation2016; Malik et al., Citation2020). The walking distance between modes such as metro and buses can be more than half a kilometre with up to four level changes (Turner, Citation2012). Not all level changes can be completed using escalators, restricting accessibility for women with luggage and/or children (Sil et al., Citation2022). In countries with low literacy rates for females (46% in Pakistan), it is difficult for women to understand signages and information displays, creating further obstacles when navigating through stations and interchanges (World Bank, Citation2022). Furthermore, most operators do not stop vehicles properly, making it difficult for women with luggage and/or children to board or egress from vehicles (Malik et al., Citation2020; Rahman, Citation2010). Some countries have acknowledged these barriers to women’s travel with formal PT modes and have taken initiatives to improve women’s transport choices. Bangladesh, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Thailand and Pakistan have adopted women-only services in major local cities and also reserved seats for women in vehicles, despite being rarely enforced (Regmi & Yamamoto, Citation2021). Countries such as Malaysia and India provide concessionary travel fares for students and female passengers (Agrawal & Sharma, Citation2015). Other countries have taken initiatives to encourage women to be operators. In Indonesia, an increase in the number of female-operated motorcycle taxis was seen. In Bangladesh, the conductors in women-only buses are female. India and Nepal developed policies to generate female-occupied employment in the transport sector such as owners and drivers of informal modes (Regmi & Yamamoto, Citation2021).

The barriers discussed in this section on women’s travel conditions are against basic rights and freedom by limiting women’s ease of access to necessities such as employment, education and health care facilities (Thynell, Citation2012). The consequences of these mobility barriers have left women to remain as second-class citizens, hindering their progression in society. In addition, victims of harassment do not receive adequate support (Gekoski et al., Citation2017; Hoor-Ul-Ain, Citation2020). The findings have been categorised into four main themes consisting of socio-cultural norms, poor operational performance, infrastructural limitations and sexual harassment. provides a summary of critical factors for each dimension and main findings for each factor.

Table 1. Mobility barriers for each dimension.

4. Common methods for data collection and limitations

Studies predominately on women’s perceptions of safety and their transport choices in South and Southeast Asian countries commonly use questionnaires for data collection. Major limitations discussed in research studies include sample size and targeted population groups (Natarajan, Citation2016; Sham et al., Citation2012; Verma et al., Citation2020). Sample size commonly range between 120 and 380 respondents for web-based and paper surveys. Limited sample sizes create inability to represent the population and intersectional groups of women. Only three studies conducted household travel surveys at a large scale. The sample size of these household surveys, with around 2500 participants along with in-depth interviews with 20–50 PT riders (Gopal & Shin, Citation2019; Neupane & Chesney-Lind, Citation2014). Research budget and response rate limit the sample size, making it difficult to include lower socio-economic groups, which require more resources. Targeted population groups are usually those who are easily accessible due to their literacy and means of communication (access to internet) such as commuters, employed women and university students. Only two studies included the journey experiences of women from low socio-economic groups (Hossain & Susilo, Citation2011; Rivera, Citation2010b; Tarigan et al., Citation2014). This limits the overall understanding of women’s journey experiences from vulnerable socio-economic groups, and the depth of knowledge available to practitioners and policy-makers.

Sexual harassment is the most studied topic for women’s travel experiences. Gekoski et al. (Citation2017) found that sexual harassment occurrence is higher in developing economies, due to differing cultural and gender norms, and that majority of incidences go unreported. One of the main reasons for underreporting of incidences is victim-blaming. This originates from complexities involving underlying societal and cultural patriarchy in law and enforcement, in addition to lack of protection laws in the PT sector (Lea et al., Citation2017; Natarajan, Citation2016; Neupane & Chesney-Lind, Citation2014). Transport authorities are left with limited data to inform any decisions in the planning and design of PT systems. Studies typically attain information on sexual harassment occurrence through surveys which include questions on frequency, type of harassment and severity of incidences experienced by female passengers in-vehicle, at platforms and by PT mode (Gopal & Shin, Citation2019; Hossain & Susilo, Citation2011). A limited number of studies examined the sociological and psychological consequences of victimisations (Hoor-Ul-Ain, Citation2020; Valan, Citation2020). Natarajan (Citation2016) is amongst the limited number of studies which examined the effects of built environments on the occurrence of sexual harassment. The study included interviews with the local police officers (n = 30) to discuss probability and types of sexual harassments reported. The safety audits were based on the overall impression of built-environment, lighting, sight-lines, nearby land use, design of bus shelters and general upkeep.

In the last decade, women in Asia are speaking up against sexual violence. In India, the Nirbhaya movement in 2012 (Times of India-Online, Citation2019) caused a shift in the way women respond to harassment and assault. Since then, there has been a significant increase in the number of sexual harassment and assault cases reported. A few studies explored the role of Information and Communication Technology in improving personal safety of women while travelling, with the additional benefit of collecting harassment data. “SafeBand” is an application developed in Bangladesh which sends GPS coordinates to the nearest police station in the event of an incidence and messages to saved contacts (Islam et al., Citation2018). In India, another application, Safetipin, based on crowdsourced data which allows users to rate the safety of a location and generates safety scores for various public places (Safetipin, Citationn.d.). Similarly, in Pakistan, the application “MehfoozAurat” features safe routes, emergency alerts and audio recording in regional languages (Sarosh et al., Citation2016). Despite successful testing of these initiatives, reasons for low uptake by transport authorities are still unclear (Sarosh et al., Citation2016).

The review found only two studies which examined international policies and initiatives to mitigate the barriers commonly encountered by women in these developing countries. Adur and Jha (Citation2018) discussed the Safe Cities global initiative by the United Nation post an incidence of sexual violence in Delhi (Nirbhaya movement). The study stated the importance of using an intersectional approach for women, over a homogeneous group, based on socio-economic characteristics to gain a holistic understanding of their travel needs. Turner (Citation2012) examined World Bank financed transport projects in countries such as Vietnam, Bangladesh, Laos and Cambodia. They concluded that there are provisions of gender inclusion at the planning phases, however, due to inadequate evaluation methods, the strategies and measures set at the planning phase were ignored and not incorporated in the policies for local authorities.

5. Policy

This section provides a critical look at international and national policies on gender inclusion in public transport planning, design and implementation. Some of the key policies and its objectives are summarised in .

Table 2. Key policies and tool kits by international organisations.

5.1. International toolkits and indicators for women’s travel needs

International organisations leading on policy and planning for inclusive PT systems are the World Bank, United Nations, Asian Development Bank (ADB), Institute for Transport and Development Policy (ITDP), and International Transport Forum (ITF). Although work began as early as 1998, the guidelines and operational plans were not implemented until 2013 when the ADB published a gender mainstreaming toolkit in transport. ADB shifted from “Women In Development (WID)” approach in 1995, in which women are considered to be a special target group, to a “Gender and Development approach”, in which gender is a cross-sectional factor at all levels of social and economic process (Asian Development Bank, Citation1998). This created a significant shift in the way women’s travel needs are considered in policies.

Gender equity policies have become more focused and tangible in the past decade. Amongst the available list of indicators, the ADB has developed a detailed and structured framework for each step of project planning and implementation. Toolkits by the ADB, ITF and World Bank provide indicators for gender inclusion in transport, which commonly include, travel patterns, affordability, and safety (Asian Development Bank, Citation2013b; ITF, Citation2022; World Bank, Citation2010). The “Gender Toolkit” in 2013 by ADB provides more explicit indicators on affordability, compared to other organisations, including proportion of income spent on transport by gender, subsidised and flexible tickets by gender, satisfaction of PT services (Asian Development Bank, Citation2013b). Another gender toolkit by ADB published in 2013 includes indicators on gender sensitisation of operators. Similarly, the ITF’s “Gender Analysis Toolkit for Transport 2022” has an additional indicator for public awareness of women’s personal safety and security. This toolkit by ITF has the least number of indicators on accessibility to services. Alongside indicators, appropriate tools are required to assist in the interpretation and evaluation of a project’s alignment with international policies. ADB provides detailed planning tools in comparison to other international organisations. Capacity building has been discussed to be the most important factor by all organisations. This includes participatory approaches to planning, changes in infrastructure design after consultation with women, and participation of women at training workshops on social impacts of transport. Intentional employment of women in the transport sector can improve gender representation and assist in the development of more inclusive PT systems from the early stages of planning and design. The ADB “Gender Toolkit 2013” includes indicators related to the number of market spaces reserved for women along highways, bus or train stations, and incentives designed to recruit women and increase their capacity in the transport sector. The World Bank’s “Making Transport Work for Women and Men Tools for Task Teams” in 2010 provides a different approach to ADB by identifying women’s employment in the developing countries as “smart economics” for a country’s economic growth. Although, the World Bank has given suggestions for “smart economics”, the United Nations Economic and Social Council has a more detailed toolkit to integrate a “caring economy” as a core component into economic analysis and policy-making (UNESCAP, Citation2008). It is recommended that authorities acknowledge women as major users of formal PT and use the indicators to set national budgets to benefit women.

Despite progress at an international level, there has been limited progress in inclusive PT systems for developing Asian cities (Thynell, Citation2016). One of the main issues is interpretation of the policies. The global indicator framework by the United Nations for SDGs, states “Proportion of population that has convenient access to public transport, by sex, age and persons with disabilities” for SDG 11.2 (United Nations, Citation2016). The term “convenient” has led to different interpretations at nation levels. The National Institution for Transforming India (NITI) Aayog, a government entity responsible for overseeing the implementation of SGDs, has developed a National Indicator Framework and proposed the indicator “Proportion of households in urban areas with convenient access to public transport”. This indicator in India has removed the need for disaggregated data on different population groups as stated in the SDG 11.2 (Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, Citation2021). Further, issues of misinterpretation can occur in development of state indicators based on national frameworks, which do not specify the requirement for disaggregated data (Tiwari et al., Citation2021). In Malaysia, SDG 11.2 was misinterpreted and categorised incorrectly. The SDG 11.2 goal is related to inclusive growth and development. However, the Voluntary Local Review 2021 for Shah Alam City in Malaysia has categorised it under the thematic group of environmental sustainability and climate change. The document discussed poor vertical and horizontal integration of government authorities as a major challenge in implementation of SDG goals (Malaysia, Citation2021). Misinterpretation of the same goal at different organisational levels and countries result in outcomes that do not achieve goals set by international governing authorities. A closer look at national toolkits in these countries shows a lack of specific indicators for evaluating international transport policies and their effectiveness in providing an inclusive PT system for women.

5.2. Inclusion of gender in regional transport documents

The web-search (described in Section 2) resulted in a very limited number of transport government documents that are publicly available in English. Countries such as Myanmar, Vietnam and Indonesia have public documents available in their native language and these could not be reviewed. Documents available in English from Bangladesh, Nepal, India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Philippines and Cambodia were reviewed. A common finding was that there are no dedicated sections for gender inclusion; with Bangladesh being the exception. Very few national and state policies include, or even mention, gender and women’s needs in the transport sector. This lack of inclusion of gendered mobility contributes to the “secondary” status of women’s needs in transport policy (Rivera, Citation2010a; Tiglao et al., Citation2020; You, Citation2019). For example, the Dhaka Urban Transport Project in 2012 in Bangladesh proposed gender inclusion at the planning stage but it was not carried through to the design stage. The planning documents discussed inclusion of women’s travel needs, however, in the design stage, there was no provision to collect data such as a national travel survey, and household surveys (Dhaka Transport Co-ordination Authority, Citation2015).

Gender mobility and transport policies were also found to be separate agendas and consequently independent of each other in the planning and design stages of transport projects. For example, the Malaysian transport authorities states, in general terms, “The laws and policies on gender equality are not explicitly stated. However, women-owned statistics released by … Malaysia has clearly shown that gender equality is being practiced in Malaysia”. Aside from this statement, there are no other information publicly available for how this is achieved (Department of Statistics Malaysia, Citation2021). Similarly, Nepal’s National Transport Policy does not mention any provisions for women, however, the National Environmentally Sustainable Transport Strategy 2014 provides guidelines for gender mobility by stating “Key indicators to ensure inclusiveness of transport system, and gender equity in transport services are percentage of PT coverage, and percentage of all-women public transport vehicles; and seats for women” (Ministry of Physical Infrastructure and Transport, Citation2014).

Transport policies often refer to vulnerable groups, which include children, women, disabled and the elderly together as a single group (Ministry of Planning, Citation2018; Ministry of Transport and Civil Aviation, Citation2015; Ministry of Urban Development, Citation2014; National Economic and Development Authority, Citation2017). This aggregation of vulnerable population groups makes it difficult for operators to fulfil requirements for specific groups with differing travel needs. Such aggregation dissolves women’s travel needs and they are often neglected in any decision-making process. For example, the National Urban Transport Policy in India by the Ministry of Urban Development states that “The Constitution … ensures equality … people with reduced mobility. It includes people with different abilities, senior citizens, women, and children, pregnant women, families with small children, people carrying heavy luggage��� (Ministry of Urban Development, Citation2014). Sri Lankan’s transport policy states to “adequately” address the needs of women, children, disabled and elderly; wherein women are considered as part of vulnerable passengers, and there is no specific definition or objective for “adequate” (Ministry of Transport and Civil Aviation, Citation2015). Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and India, have produced policies to improve affordability of PT for women from lower socio-economic characteristics through fare subsidisation (2014–2017). In Bangladesh, the Urban Transport Policy, Dhaka states that employers are required to provide safe and secure transport for female garment workers (Dhaka Transport Co-ordination Authority, Citation2015). Sri Lanka’s National Transport policy proposes subsidies and other pricing strategies for targeted groups, including women (Ministry of Transport and Civil Aviation, Citation2015). India’s National Urban Transport Policy states that financial support will be given to local agencies for implementation of safe and secure transport for women to their workplaces (Ministry of Urban Development, Citation2014).

A major limitation in existing transport policies is the lack of explicit initiatives to target the safety and security of women in transport; despite higher rates of harassments in these countries. Only a few countries including India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Philippines have some guidelines on women passengers’ safety when riding PT (Dhaka Transport Co-ordination Authority, Citation2015; Ministry of Planning, Citation2018; Ministry of Urban Development, Citation2014; National Economic and Development Authority, Citation2017). India has a policy (Ministry of Urban Development, Citation2014) to deploy only police-verified drivers and conductors on buses. However, a major share of bus fleet are privately owned and the operators do not need to pass police verification; thereby exempting them from this requirement. Similarly, drivers of informal transport modes in most South and Southeast Asia countries are not required to verify their vehicles after the initial check (Times of India, Citation2013). Those who privately operate such as Uber are outside any law or policy set by transport authorities for the PT sector. Bangladesh’s government proposes to review existing provisions to respond to women’s safety and security travel needs (Dhaka Transport Co-ordination Authority, Citation2015). However, these enforcement policies do not reflect the seriousness of the issue. Policies and laws which are explicit in terms of actions and resulting consequences are lacking from transport authorities and law enforcement. Without adequate protection laws, women will continue to face harassment, struggle to meet their travel needs and be discouraged from riding formal PT modes (Hossain & Susilo, Citation2011; Panjwani, Citation2018).

6. Knowledge gaps for future research

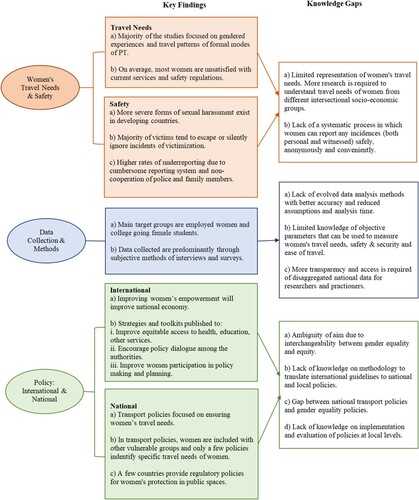

This review has identified key knowledge gaps on gender inclusion in PT systems. The knowledge gaps are grouped under three themes, women’s travel needs and safety; data collection and methods; and international and national policies, as shown in .

6.1. Women’s travel needs and safety

Most studies limit their sample to educated women from higher socio-economic backgrounds and to commuters. The experiences of women who are illiterate, accompanied riders, those who refuse to take part in the survey remain uncaptured. Trips of many women in these countries are predominately non-commute trips, which are less examined. This poses difficulty in generalising the results from the studies to a broader population due to small sample sizes and biased demographic sample groups (Malik et al., Citation2020). Most of the studies on gendered experiences with PT portray journeys on the safest and least critical mode, often by the least vulnerable. There is a need to examine gendered experiences of informal PT and travel requirements of a diverse range of women including illiterate women and those from lower socio-economic backgrounds.

High rates of underreporting of sexual harassment in official records undermine women’s safety and security when riding PT. Specific laws to protect women against victimisation in PT are absent in most of these countries. This impacts the reporting incidences as patriarchally influenced authorities can ignore or refuse to file cases due to lack of protection laws. Most women do not feel confident to report cases knowing that there is an absence of protection laws on which they base the incidence. Software applications such as SafeBand and SaftiPin were developed to help women travel safely, including using PT, yet the responsibility to stay safe remains with women; the police and perpetrators are not held accountable. The tools are unable to lodge formal complaints with the police, making the information redundant when reporting a case. Such tools act on the symptoms of inefficient laws, whereas the root causes such as lack of protection laws, and gender sensitisation of public and police remain. Addressing the travel needs of women from different sociodemographic groups, in particular those with lower literacy and reliant on PT, is required to develop an inclusive PT system. Furthermore, suitable tools to collect data of sexual harassment incidences anonymously would provide authorities with a better representation of the barriers faced by women.

6.2. Data collection and methods

Most studies predominately adopt subjective methods to evaluate PT systems; the objective parameters such as levels of service, schedule information, infrastructure design, design capacity, are often excluded. This limits the evaluation of PT systems to be assessed objectively to determine improvement in the built environment to make the systems more inclusive for women. Machine learning techniques can be explored to analyse data to overcome the shortcomings of traditional data analysis methods. A detailed evaluation method can assist policy makers in setting targets for gender equity in PT and assist in determining the extents of existing gender gap in policy-making.

Although some national transport policies have included women’s travel needs, national travel surveys are commonly not publicly available and difficult to attain from transport authorities. For example, transport policies in Sri Lanka, Pakistan and India state provisions for women’s travel needs, however, some studies (Panjwani, Citation2018; Tripathi et al., Citation2017) have discussed the lack of understanding of women’s travel needs by transport agencies and policy-makers as a prerequisite to form policies. Another commonly reported limitation is lack of quality data available from the authorities. Access to detailed data is cumbersome, insufficient and infrequently updated (Natarajan, Citation2016). This leads to development of uninform policies which disproportionately favours the more privileged population groups (Rahman, Citation2010).

6.3. International and national policies

A closer examination of the policies showed that there exists some ambiguity in the terms adopted for gender inclusion, in particular an interchange of “equality” and “equity”. The ADB (Citation2008) in one of its strategy reports, discussed action plans to resolve gender equity issues in transport. Then in 2013, ADB published a gender-specific operational plan aiming towards gender equality and empowerment (Asian Development Bank, Citation2013a). A study by the ITF in 2018 explored gendered urban travel behaviour for equitable transport policies, whereas the 2020 toolkit project exclusively discussed gender equality (International Transport Forum, Citation2021; Ng & Acker, Citation2018). Such ambiguity between gender equality and equity at a global level can lead to misinterpretation by national and local policy makers; leaving women’s travel needs mostly unaddressed. There must be clear definitions and distinctions established for gender equality and equity when forming international guidelines and policies.

Guidelines by international organisations focused on development of PT systems to be inclusive are contingent on its implementation at national and local levels. It is unknown how a guideline provided at international level is interpreted and percolated through the various levels of authorities from national to regional to local levels. Despite the existence of some national policies, its implementation at local levels to realise the objectives has been of limited success. The process of policy formation and planning at different levels remains unclear and so are the gaps in its implementation. Further studies on the filtration of gender in the administrative, operational, infrastructural and enforcement aspects would provide deeper insights to produce more effective policies. They would provide a better understanding of the process involved in the implementation of international guidelines at local levels, and identifying any key gaps in the process. In some countries, separate gender and transport policies exist, wherein both aspects are considered separate agendas and thereby as separate responsibilities for authorities. Consideration of gender and transport together is important for addressing women’s travel needs.

Finally, evaluation of a policy is a crucial step to determine its success. There have been few attempts to examine policies, as discussed in Section 5. There is limited understanding on how policies can be evaluated in a holistic manner. In countries with limited funding and resources with high demand-supply mismatch of PT services, policy-makers typically rely on economic indicators to evaluate transportation systems. Moreover, lack of key indicators and performance targets for gender inclusion in the transport sector further prevent policies from having effective outcomes. Therefore, clear evaluation frameworks are required to better serve the purpose of a policy (Uteng, Citation2011).

In summary, addressing the above-mentioned knowledge gaps are steps toward improving women’s PT ridership in South and Southeast Asian countries. Availability of quality and disaggregated data on women’s travel needs will assist policy makers and practitioners to develop inclusive PT systems. Along with data availability, proper tools and methods for data collection by utilising machine learning techniques, and adopting objective parameters to assess women’s travel needs can improve the development of more effective policies. This may result in better implementation of policies to address women’s mobility barriers. Although, the patriarchal societal norms remain out of scope for this review, mitigating, and where possible eliminating, mobility barriers may have a positive impact on women’s overall status in society.

7. Conclusion

Awareness movements by the public on women’s safe mobility, such as the Nirbhaya campaign against sexual violence in India, have caused transport authorities to rethink the design and policies for inclusive public transport (PT) systems. Still, there is more work to be done before women can step outside their homes and travel safely. The present study provides a critical review of the typical barriers women in South and Southeast Asian countries encounter on their PT journeys, limitations in common methods used to attain data on women’s travel needs, ambiguity in international guidelines and lack of adequate national policies for inclusive PT systems. An overarching issue is the frequency and severity of sexual harassment faced by women on a daily basis when riding any modes of PT. Although an in-depth discussion of patriarchal societal norms is outside the scope of this review, its effects came through strongly in the frequency and severity of harassment women experience. It also comes through in the unclear gender inclusion guidelines, lack of and ambiguity in transport policies, and reluctancy in the approach frequently taken by law enforcement towards rarely reported sexual harassment incidents. Inefficient reporting systems, and lack of protection laws for women add to how easily violence against women can go unrecorded, even after being reported by a victim. Without any data, it is difficult for transport authorities to create effective strategies and initiatives for a safe transport environment. A common limitation is the limited sample sizes and over-sampling of easily accessible groups of women such as university students, professionals and educated women with access to internet. There is a significant lack of understanding on the travel needs of women from lower-socio-economic groups and intersectionality of different socio-economic groups.

A major limitation in the policy sector is the interpretation of international guidelines for national policies. Amongst the national transport policy documents, those that are publicly available and include gender-specific provisions are difficult to find and in countries where they do exist, some are found in other non-transport documents. Despite higher rates of sexual harassment, there are no existing provisions in national transport policies to improve reporting mechanisms by the victims. Safe mobility for women and access to basic necessities is critical for economic vitality in South and Southeast Asian countries. This can only be achieved if gendered travel needs are understood in-depth and incorporated consistently throughout the pipeline from international guidelines to local policies, and practices by transport professionals.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Adeel, M., Yeh, A. G. O., & Zhang, F. (2017). Gender inequality in mobility and mode choice in Pakistan. Transportation, 44(6), 1519–1534. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11116-016-9712-8

- Adur, S. M., & Jha, S. (2018). (Re) centering street harassment – An appraisal of safe cities global initiative in Delhi, India. Journal of Gender Studies, 27(1), 114–124. https://doi.org/10.1080/09589236.2016.1264296

- Agrawal, A., & Sharma, A. (2015). Gender contests in the Delhi metro: Implications of reservation of a coach for women. Indian Journal of Gender Studies, 22(3), 421–436. https://doi.org/10.1177/0971521515594279

- Anand, A., & Tiwari, G. (2006). A gendered perspective of the shelter–transport–livelihood link: The case of poor women in Delhi. Transport Reviews, 26(1), 63–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/01441640500175615

- Asian Development Bank. (1998). Gender and development. The Journal of Educational Sociology, 66(0), https://doi.org/10.11151/eds1951.66.67

- Asian Development Bank. (2008). Strategy 2020: The long-term strategic framework of the Asian development bank 2008-2020. In Development.

- Asian Development Bank. (2013a). Gender equality and women’s empowerment operational plan, 2013–2020 (Vol. 13, Issue October).

- Asian Development Bank. (2013b). Gender tool kit: Transport.

- Bachok, S., Osman, M. M., Murad, M., & Ibrahim, M. (2014). An assessment of commuters’ perceptions of safety and comfort levels of ‘women-only coach’: The case study of KTM Komuter Malaysia. Procedia Environmental Sciences, 20, 197–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proenv.2014.03.026

- Ceccato, V. (2017). Women’s victimisation and safety in transit environments. Crime Prevention and Community Safety, 19(3–4), 163–167. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41300-017-0024-5

- Clarke, M. (2010). Making transport work for women and men: Tools for task teams. World Bank Social Development. World Bank Publications - Reports 12555, The World Bank Group.

- Department of Statistics Malaysia, Laws and Policy on Gender Equality. Retrieved 25 July 2022, from https://www.malaysia.gov.my/portal/content/30715

- Dhaka Transport Co-ordination Authority. (2015). Urban transport policy (Issue November).

- Dhillon, M., & Bakaya, S. (2014). Street harassment: A qualitative study of the experiences of young women in Delhi. SAGE Open, 4(3), 2158244014543786. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244014543786

- Gekoski, A., Gray, J. M., Adler, J. R., & Horvath, M. A. H. (2017). The prevalence and nature of sexual harassment and assault against women and girls on public transport: An international review. Journal of Criminological Research, Policy and Practice, 3(1), 3–16. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCRPP-08-2016-0016

- Gopal, K., & Shin, E. J. (2019). The impacts of rail transit on the lives and travel experiences of women in the developing world: Evidence from the Delhi metro. Cities, 88, 66–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2019.01.008

- Hoor-Ul-Ain, S. (2020). Public sexual harassment mayhem on public transport in megacities-Karachi and London: A comparative review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 52, 101420. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2020.101420

- Hossain, M., & Susilo, Y. O. (2011). Rickshaw use and social impacts in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Transportation Research Record, 2239(1), 74–83. https://doi.org/10.3141/2239-09

- International Transport Forum. (2021). Gender analysis toolkit for transport policies. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789282107782-en

- Iqbal, S., Woodcock, A., & Osmond, J. (2020). The effects of gender transport poverty in Karachi. Journal of Transport Geography, 84, 102677. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2020.102677

- Islam, M. N., Promi, N. T., Shaila, J. M., Toma, M. A., Pushpo, M. A., Alam, F. B., Khaledur, S. N., Anannya, T. T., & Rabbi, M. F. (2018). SAFeband: A wearable device for the safety of women in Bangladesh. In Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Advances in Mobile Computing and Multimedia (pp. 76–83).

- ITDP. (2015). Mobility for all: A strategic transportation plan for Ranchi, Retrieved April 12 from Mobility for all: A strategic transportation plan for Ranchi - Institute for Transportation and Development Policy (itdp.org).

- ITF. (2022). Gender analysis toolkit for transport (pp. 2–8). OECD Publishing. https://www.itf-oecd.org/itf-gender-analysis-toolkit-transport

- Kranrattanasuit, N. (2017). Inaccessible public Bus services in Thailand. Asia-Pacific Journal on Human Rights and the Law, 18(1), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1163/15718158-01801001

- Lea, S. G., D’Silva, E., & Asok, A. (2017). Women’s strategies addressing sexual harassment and assault on public buses: An analysis of crowdsourced data. Crime Prevention and Community Safety, 19(3–4), 227–239. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41300-017-0028-1

- Mahadevia, D., & Advani, D. (2016). Gender differentials in travel pattern–the case of a mid-sized city, Rajkot, India. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment, 44, 292–302. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trd.2016.01.002

- Malaysia, U. (2021). Voluntary local review 2021.

- Malik, B. Z., ur Rehman, Z., Khan, A. H., & Akram, W. (2020). Women’s mobility via bus rapid transit: Experiential patterns and challenges in Lahore. Journal of Transport & Health, 17, 100834. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jth.2020.100834

- Masood, A. (2018). Negotiating mobility in gendered spaces: Case of Pakistani women doctors. Gender, Place & Culture, 25(2), 188–206. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2017.1418736

- Ministry of Physical Infrastructure and Transport. (2014). National environmentally sustainable transport (EST) strategy for Nepal (Issue April).

- Ministry of Planning, D. & R. (2018). National transport policy of Pakistan. www.pc.gov.pk

- Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation. (2021). National indicator framework version 3.0. 44.

- Ministry of Transport and Civil Aviation. (2015). National transport policy of Sri Lanka.

- Ministry of Urban Development. (2014). National Urban Transport Policy, 2014. In NUTP (2014) ‘National Urban Transport Policy, 2014’ (pp. 1–39). www.iutindia.org. www.iutindia.org

- Murali, V. S. (2020). Transport solutions for violence against women in India. In Voices on south Asia: Interdisciplinary perspectives on women’s status, challenges And futures, 89.

- Natarajan, M. (2016). Rapid assessment of “eve teasing” (sexual harassment) of young women during the commute to college In India. Crime Science, 5(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40163-016-0049-6

- National Economic and Development Authority. (2017). National transport policy and its implementing rules and regulations.

- Neupane, G., & Chesney-Lind, M. (2014). Violence against women on public transport in Nepal: Sexual harassment and the spatial expression of male privilege. International Journal of Comparative and Applied Criminal Justice, 38(1), 23–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/01924036.2013.794556

- Ng, W.-S., & Acker, A. (2018). Understanding Urban travel behaviour by gender for efficient and equitable transport policies (No. 2018–01; International Transport Forum Discussion Paper).

- Panjwani, N. (2018). Mainstreaming gender in Karāchī’s public transport policy. European Journal of Sustainable Development, 7(1), 355. https://doi.org/10.14207/ejsd.2018.v7n1p355

- Rahman, M. S.-U. (2010). Bus service for ‘women only’ in Dhaka city: An investigation. Journal of Bangladesh Institute of Planners, 3(December 2010), 17–32. www.springwise.com

- Regmi, M. B., & Yamamoto, J. (2021). Gender mainstreaming in transport – A long route to transport equality. ESCAP. https://www.unescap.org/blog/gender-mainstreaming-transport-long-route-transport-equality#

- Rivera, R. L. K. (2010a). Gender and transport: Experiences of marketplace workers in Davao city, Philippines. Environment and Urbanization ASIA, 1(2), 171–186. https://doi.org/10.1177/097542531000100205

- Rivera, R. L. K. (2010b). Gender and transport. In International transport forum (Vol. 1, Issue 2, pp. 171–186). https://doi.org/10.1177/097542531000100205

- Safetipin, Safetipin, Creating Safe Public Spaces for Women. (n.d.). Retrieved 3 March 2022, from https://safetipin.com/

- Sarosh, M. Y., Yousaf, M. A., Javed, M. M., & Shahid, S. (2016). Mehfoozaurat: Transforming smart phones into women safety devices against harassment. Proceedings of the Eighth International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies and Development (pp. 1–4).

- Shah, S., Viswanath, K., Vyas, S., & Gadepalli, S.. (2017). Women and transport in Indian cities (pp. 1–80). ITDP and Safetipin.

- Sham, R., Hussein, M. Z. S. M., & Ismail, H. N. (2013). A dilemma of crime and safety issues among vulnerable travellers in Malaysian urban environment. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 105, 498–505. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.11.053

- Sham, R., Soltani, S. H. K., Sham, M., & Mohamed, S. (2012). Travel safety fear factor among vulnerable group of travelers: The urban scenario. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 50, 1033–1042. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.08.103

- Sil, A., Chaniotakis, E., Roy, U. K., & Antoniou, C. (2022). Exploring satisfaction for transfers at intermodal interchanges: A comparison of Germany and India. Journal of Public Transportation, 24, 100005. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubtr.2022.100005

- Tara, S. (2011). Private space in public transport: Locating gender in the Delhi metro. Economic and Political Weekly, 46(51), 71–74.

- Tarigan, A. K. M., Susilo, Y. O., & Joewono, T. B. (2014). Segmentation of paratransit users based on service quality and travel behaviour in Bandung, Indonesia. Transportation Planning and Technology, 37(2), 200–218. https://doi.org/10.1080/03081060.2013.870792

- The World Bank. (2022). Literacy rate, adult female (% of females ages 15 and above) – Vietnam, Indonesia, India, Bangladesh, Philippines, Pakistan, Malaysia | Data. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SE.ADT.LITR.FE.ZS?locations=VN-ID-IN-BD-PH-PK-MY

- Thynell, M. (2016). The quest for gender-sensitive and inclusive transport policies in growing Asian cities. Social Inclusion, 4(3), 72–82. https://doi.org/10.17645/si.v4i3.479

- Tiglao, N. C. C., De Veyra, J. M., Tolentino, N. J. Y., & Tacderas, M. A. Y. (2020). The perception of service quality among paratransit users in Metro Manila using structural equations modelling (SEM) approach. Research in Transportation Economics, 83, 100955. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.retrec.2020.100955

- Times of India. (2013). Autorickshaw drivers told to get police verification done within 15 days. Gurgaon News - Times of India. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/gurgaon/autorickshaw-drivers-told-to-get-police-verification-done-within-15-days/articleshow/27231120.cms

- Times Of India-Online. (2019). What is Nirbhaya case? | What is Nirbhaya case full story? India News - Times of India. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/what-is-nirbhaya-case/articleshow/72868430.cms

- Tiwari, G., Chauhan, S. S., & Varma, R. (2021). Challenges of localizing sustainable development goals in small cities: Research to action. IATSS Research, 45(1), 3–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iatssr.2021.02.001

- Tripathi, K., Borrion, H., & Belur, J. (2017). Sexual harassment of students on public transport: An exploratory study in Lucknow, India. Crime Prevention and Community Safety, 19(3), 240–250. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41300-017-0029-0

- Turner. (2012). Urban mass transit, gender planning protocols and social sustainability – The case of Jakarta. Research in Transportation Economics, 34(1), 48–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.retrec.2011.12.003

- UNESCAP. (2008). The Inland Transport Committee and gender issues in transport. https://www.unece.org/fileadmin/DAM/trans/doc/2009/itc/ECE-TRANS-2009-07e.pdf

- United Nations. (2016). THE 17 GOALS. https://sdgs.un.org/goals

- Uteng, T. P. (2011). Gender and mobility in the developing world. In World Development Report Background Paper.

- Valan, M. L. (2020). Victimology of sexual harassment on public transportation: Evidence from India. Journal of Victimology and Victim Justice, 3(1), 24–37. https://doi.org/10.1177/2516606920927303

- Verma, M., Rodeja, N., Manoj, M., & Verma, A. (2020). Young women’s perception of safety in public buses: A study of Two Indian cities (Ahmedabad and Bangalore). Transportation Research Procedia, 48, 3254–3263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trpro.2020.08.151

- Women UN. (2017). Safe cities and safe public spaces: Global results report. In UN Women, New York.

- World Bank. (2010). Making transport work for women and men tools for task teams. December.

- You, S. (2019). Women’s unsafe mobility in public transport in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. SAGE Publications Sage CA.