ABSTRACT

Independent transport mobility is an important contributor to health, well-being, and participation. Several skills and competences are required for a person to use the transport system. The characteristics of cognitive disorders, such as Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) and Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), may pose barriers to independent travel.

Methods

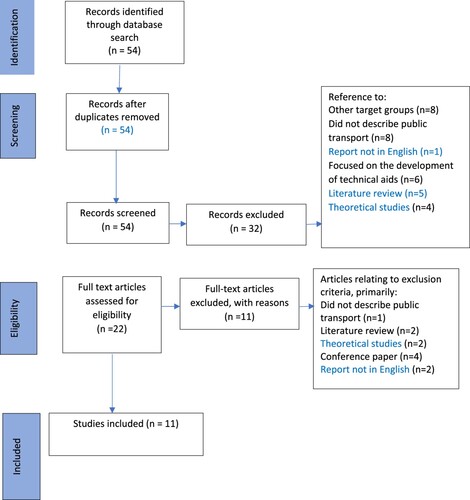

The study’s aim was to synthesise knowledge on the use of public transport among individuals with ASD or ADHD using the whole journey chain perspective. A scoping review using the PRISMA ScR framework was conducted, and included articles published between January 2012 and June 2022. A total of 11 studies from four countries were included in the analysis.

Results

This study complements the whole journey chain perspective with a phase that takes place long before the journey begins, and which concerns planning and preparation. Confident travellers could easily learn new routes, while those lacking confidence faced challenges, especially with unexpected route changes or cancellations.

Conclusions

There is a great need for emphasis on the design of public transport facilities and public spaces to increase the sense of safety for travellers with ASD, and to assist them with information-seeking, comprehension, and recovery between journeys.

1. Introduction

Independent transport mobility is an important contributor to health and well-being (Hillman et al., Citation1991; Jakobsen et al., Citation2017; Mackett & Thoreau, Citation2015). It increases physical activity (Marzi & Reimers, Citation2018; Schoeppe et al., Citation2015), enables interaction with friends and the local community (Cele, Citation2006; Villanueva et al., Citation2014), and enables participation in work life, education, and leisure activities (Gough, Citation2008; Schwanen & Ziegler, Citation2011). In recent decades, everyday transportation has largely relied on private car usage, facilitated by land use planning that prioritises car accessibility (Lucas & Jones, Citation2009; Rye & Hrelja, Citation2020). However, for individuals lacking access to private cars – such as children (Carver et al., Citation2008), low-income earners (Jones & Lucas, Citation2012), and those with disabilities (Darcy & Burke, Citation2018) – a reliable public transportation system is essential. Using public transport systems requires various resources and skills (Bezyak et al., Citation2017; Flamm & Kaufmann, Citation2006; Sharples, Citation2017; van Exel & Rietveld, Citation2009), including route planning, ticket purchasing, navigation, and overcoming physical barriers.

In today's society, digital advancements in public transit continue to evolve, introducing new ticketing systems, mobility services, travel planners, and vehicle technologies (Davidsson et al., Citation2016). While these digital developments aim to streamline travel, they pose challenges for many individuals due to the requisite digital literacy and personal responsibility (Durand et al., Citation2022). A Swedish investigation suggests that while individual physical or technical measures are emphasised, qualitative measures such as service quality, information availability, and traffic environment accessibility are equally crucial throughout the travel process (Trafikanalys, Citation2019). People with disabilities remain one of the most marginalised groups in society regarding transport opportunities (Park & Chowdhury, Citation2018; Visnes Øksenholt & Aarhaug, Citation2018; Wayland et al., Citation2022). Poor access to public transport is a key risk for social exclusion, and people with disabilities are especially vulnerable due to lesser opportunities to walk, bike or drive, due to both the personal limitations of the person and barriers in the physical and social environment (Clayton et al., Citation2017; Mao & Chen, Citation2022). While significant improvements have been made in recent decades to minimise physical barriers in public transportation systems and vehicles globally, individuals with disabilities still encounter numerous obstacles when using public transit (Bezyak et al., Citation2017; Davidson & Pfeiffer, Citation2024; Egard et al., Citation2022). Limited access to public transportation presents a significant risk of social exclusion (Lucas, Citation2012).

Individuals with ASD and ADHD often encounter challenges when travelling by public transport due to common symptoms and behaviours associated with their diagnoses (Berg & Ihlström, Citation2022; Davidson & Pfeiffer, Citation2024; Precin et al., Citation2012; Thériault & Morales, Citation2022). Berg and Ihlström (Citation2022) discovered that individuals with neuropsychiatric disabilities, wherein ASD and ADHD are the most common diagnoses, rely more heavily on public transportation for daily commuting and frequently experience fatigue from travel. Moreover, they tend to avoid using public transport more frequently than those without these diagnoses, resulting in absences from work or school due to the difficulties they encounter during travel. Challenges specific to individuals with ASD include sensitivity to sensory stimuli, difficulties in social interactions, communication, and emotional regulation (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013). Individuals with ADHD commonly struggle with maintaining attention and managing hyperactivity (Barkley, Citation2014). Both groups often face issues related to executive functioning, such as planning and executing tasks, sustaining attention, and adhering to routes (Precin et al., Citation2012). Executive functioning difficulties can lead to missing scheduled transport, boarding or alighting at incorrect stops, and difficulty reorienting to the correct route. Additionally, hypersensitivity to noise, crowded environments, and a lack of personal space can exacerbate the challenges faced by individuals with ASD and ADHD when using public transportation (Precin et al., Citation2012).

In a review of scientific literature concerning the needs of individuals with cognitive disabilities in public transportation, Risser et al. (Citation2015) noted that most studies primarily focus on outdoor mobility in a broad context, overlooking the various segments of a journey. However, their literature review did not encompass studies specifically addressing individuals with ASD or ADHD. Previous research has predominantly concentrated on children with ASD, neglecting the occupational and transportation requirements of young adults and adults transitioning into adulthood (Baric et al., Citation2017; Thériault & Morales, Citation2022). This current study aims to address this gap in knowledge by offering insights into the entire journey process, irrespective of the traveller’s age, and suggesting improvements and adjustments within public transportation systems to facilitate independent travel for individuals with ASD and ADHD.

1.1. The whole journey chain by public transport

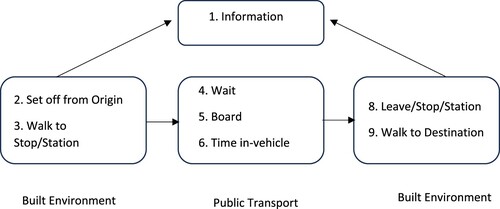

To be able to travel independently, the entire chain of events needs to be comprehensible and functional, referred to as the whole journey chain by Park and Chowdhury (Citation2018) (Please see ). The whole journey chain includes planning journeys, buying, and using tickets, moving around, and orienting oneself in the various places associated with public transport (waiting rooms, bus stops, etc.) in a safe and secure way, understanding information, boarding, finding somewhere to sit, knowing how to get off, and finding one’s way to the final destination. A few studies have taken into consideration the importance of the whole journey chain among people with disabilities. For example, Park and Chowdhury (Citation2018) studied key barriers in a typical public transport journey among people with visual and physical impairments. Martel et al. (Citation2021) studied in what way the built environment, including public transport amenities, supported people with disabilities to access work. Neven and Ectors (Citation2023) explored the mobility barriers and solutions for societal participation among people with physical and cognitive disabilities. Research that focuses on public transport journeys among people with ASD or ADHD is scarce. Such knowledge is important for knowing which adaptations can increase their mobility opportunities and participation in everyday life activities.

Figure 1. The accessible journey chain as described by Park and Chowdhury (Citation2018).

2. Study aim

The aim of this scoping review is to synthesise knowledge on the use of public transport among individuals with ASD or ADHD from a whole journey chain perspective. The research question guiding the search is:

What facilitators and barriers are related to public transport use, from the starting point to the final destination, among individuals with ASD or ADHD?

3. Methods

This scoping review was conducted using the PRISMA ScR (Tricco et al., Citation2018) framework for conducting a scoping study review.

3.1. Eligibility criteria

As the objective of this scoping review was to determine the breadth of original research on the topic, inclusion criteria were empirical studies published in peer-reviewed journals written in English. The timeframe was limited to studies published between January 2012 and June 2022 to include recent research in the field. Due to rapid digital advancements in the transportation sector, the decision was made to focus on the most recent 10 years to include the latest research.

3.2. Information sources

In accordance with PRISMA-ScR (Peters et al., Citation2020) inclusion criterions were based on participants, concept, and context. Participants included persons with neurodevelopmental disorder, primary with diagnoses of ASD and ADHD. Concept relates to public transport and context was to enable engagement in activities/services such as community participation, activities of daily living, or school and/or work.

The following databases were used to identify peer-reviewed literature: Scopus, PubMed, TRID and Google Scholar. A librarian was consulted to identify and refine key search words, to advise on what databases, Boolean operators, double quotes, and truncation to use, all of which might differ in different databases.

3.3. Database search

An initial search was conducted in Scopus and then converted for each subsequent database to ensure these would produce relevant results. For each database, a search strategy was adapted with a similar combination of descriptors and keywords. The search string used was as follows:

(“Attention deficit hyperactivity disord*” OR ADHD OR ASD OR ADD OR “Autism spectrum disord*” OR ASD OR Autism OR “Neurodevelopmental disord*” OR “Asperger syndrome” OR Tourette's OR developmental language disorder AND transport* OR “public transport*” OR special transportation service* OR travel OR trip OR journey OR mobility).

3.4. Selection of sources of evidence

Two researchers (VBB and JB) independently screened all articles by abstract and title for relevance. The decision to include or exclude sources that did not have agreement during this initial review was discussed by the authors until consensus was reached. When there was an uncertainty about relevance among the researchers, the article was kept for the next phase, which involved reading each of the selected articles in full to confirm their relevance and then extracting the data if relevance was confirmed. Inconsistencies or doubts were resolved by discussions among the authors. The comprehensive search in four databases using the key words presented in identified 54 articles. Given the inclusion and exclusion criteria, full text versions of 22 articles were read by the first and third authors and additional articles were excluded based on exclusion criteria as presented in .

3.5. Data extraction and analysis

After the articles were selected, data were extracted and recorded in a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. The extracted data were: (1) Author (s), (2) Year of publication, (3) Study location, (4) Aim, (5) Study population, (6) Sample size, (7) Age of the participants, (8) Study design, (9) Data used, and (10) the phases and related stages (n = 9) from the whole journey chain according to Park and Chowdhury (Citation2018). Data on characteristics of the articles was compiled and presented descriptively in the results. Data that was extracted based on the phases and stages were then analysed using directed content analysis as described by (Hsieh & Shannon, Citation2005), implying that the coding is based on predetermined categories. The data were compared and contrasted for each phase and stage. After that, the coded data were examined and compared with the theoretical description of the whole journey chain (Park & Chowdhury, Citation2018). The first author conducted the coding while the second and third authors served as peer reviewers. To increase the dependability of the scoping review the analysis of data was continuously discussed during the process until consensus was reached among the authors (Krefting, Citation1991).

4. Results

This scoping review yielded 11 articles from four countries (see ). The included articles are presented as Arabic numerals according to .

Table 1. Characteristics of included studies according to the whole journey stages (n = 11).

Four studies were conducted in the United States, four in Australia, two in Sweden and one in Singapore. Studies were published between 2012 and 2022; three studies were published between 2012 and 2015, five between 2016 and 2020, and three studies between 2021 and 2022.

Most of the studies included individuals with ASD (n = 9), one study focused on individuals with ADHD, as well as other conditions such as visual or mobility impairments (n = 1). Eight studies focused on adults and two on children. Two studies included parents to either children or young adults.

Four studies were cross-sectional using surveys, two studies had a qualitative approach with individual and/or focus group interviews, with two studies using ethnography. Three studies used different designs including a longitudinal design, q-method, and a laboratory study.

Besides the phases and stages based on the whole journey chain (Park & Chowdhury, Citation2018), an additional phase “Planning for a life as a traveller precedes information seeking and gathering”, containing four additional stages, was identified in the analysis (see ).

Table 2. Overview of the phases/stages, subthemes, and key findings.

4.1. Pre-stage: planning for becoming a traveller

This theme shows that planning preceded information-seeking and consisted of an overall planning for a life as a traveller, which included the decision on whether travelling is worth the effort. Several studies (1, 4, 6, 8–9) pointed to the need for extensive planning before the journey even takes place which required confidence to travel to achieve greater goals of independence, and careful planning and practice for a life as a traveller.

4.1.1. Public transport- is it worth it?

Public transport was described as a significant challenge and a mental burden (3–4, 6, 8) with the individual having to decide whether travelling is worth the effort. People with ASD described avoiding public transport due to the effort required to navigate the uncertain public system (4, 6–9), with some individuals developing home-based occupations and social participation patterns which reduced the need and motivation for public transport (4). Studies have reported that individuals with ASD never use any form of public transport (7, 9). The use of fixed-route transit, consisting of commuter train and buses, was not very common (3, 9). Having the opportunity to choose between buses, trains or taxi, participants with ASD expressed a preference for buses or taxi due to higher degree of predictability, comfort and seating and shorter waiting times (6). Participants who preferred taking buses highlighted reasons such as ease of learning, predictability of travel journeys, availability of seats, and convenience of travelling to their destination (4).

4.1.2. Travelling as a means to achieve greater goals

For individuals with ASD, travelling by public transport was described as essential for achieving independence (2, 5–6), quality of life (2, 7) as well as for future community participation (5). Most studies described public transport as being used for “essential” trips (9) to social and recreational activities, followed by trips for medical or healthcare appointments and education or training (2, 10). Public transport was also described as important for visiting family and friends, shopping, and running errands (6–7, 9). Individuals with ASD described an eagerness and an ambition to learn to travel independently to fully participate in society and be in control of their own lives (2, 5). Having the confidence (8) and economy to travel (11) were especially described by particiants with ADHD as a facilitator to independent travel. Need of support for transportation related issues tend to be higher among certain populations such as individuals with ADHD, and those living in areas with limited or no public transportation systems (e.g. rural settings) (11). Individuals with ADHD were reported as having higher odds for requesting support for transportation related issues such as community ride programmes and transit vouchers (11). Also, not having to worry about the attitudes of other people (2, 9), both staff and fellow passengers, were described as facilitators to public transport use by individuals with ASD. This theme described difficulties in planning public transport due to lack of information, unpredictability in public transport, need for visual and audio information and difficulties using electronic ticketing.

4.1.3. Uncertainty vs. confidence in travelling

The findings portrayed two different public transport travellers that can be characterised as being uncertain or having confidence in using public transport. Some individuals were portrayed in the studies as frequent and comfortable users of public transport (2) with confidence in their ability to learn new routes easily (2). These participants described managing train line maps and any anxiety or sensory issues they may experience on public transport (2). These individuals were characterised in the study as those who were frequent and comfortable users of public transport (2). However, studies (7, 9) also showed that individuals with ASD tend to make fewer journeys than the rest of the population due to their lack of confidence in travelling and the lack of consistency, unpredictability, and inflexibility of public transport. Participants that expressed a lack of confidence mainly highlighted their difficulties in managing to travel independently on a new route (2, 5, 7) due to interruptions such as quick changes that occur because of delays, cancellations or changes to routes or timetables. These traveller interruptions affect all travellers but may be particularly challenging for individuals with ASD, who have additional difficulties managing stress and problem-solving or quickly recalculating previous carefully planned itineraries (4).

4.1.4. Preparing for a life as a traveller by careful planning and practice

Using public transport required individuals with ASD to prepare for a life as an independent traveller, which can be considered as an overarching phase. This phase consisted of several strategies including tailored and practical help in travelling by public transport by practising travelling from a young age with parents (1, 4), or with a one-on-one travel companion ahead of time (1). Travel training usually involved participants practising interactions with the bus driver/train staff, as well as learning to ask for: a seat, help from strangers, and learning to cope with the unpredictability of public transport systems (6), all of which influenced the participants’ confidence in their capability to use public transport independently. Travel training included careful planning ahead (4, 8, 9) by using technical support systems such as planning apps and live travel information to extract information on timetables (3–4, 6), creating simple handwritten directions, and learning the route visually (1).

4.2. Stage 1: information seeking and gathering

This theme described difficulties in planning public transport due to lack of information, unpredictability in public transport, need for visual and audio information and difficulties using electronic ticketing.

4.2.1. Difficulties planning public transportation trips due to lack of information

Clear information in appropriate formats provided both before and during the journey was described by individuals with ASD as important for predictability and control and to make planning and timing as accurate as possible (1, 3–4, 5–6). This implies information was needed in a comprehensive format (1, 6). Several studies stated that confidence arise from the opportunity to obtain sufficient information both before and during the journey (3–4, 6, 8, 10) followed by the ability to process information effectively to make decisions at appropriate points throughout the journey (3–4, 6, 8).

Various difficulties with planning trips due to the unpredictability of train/bus arrival times were found and described as causing emotional distress (6) for individuals with ASD. One study highlighted difficulties assessing coherent travel planning information, both online and on paper, in bus/train schedules (5). Individuals with ASD highlighted the need for both visual and audio information, and information on time for the next departure (3, 7), providing them with a sense of control concerning when to board and/or alight the vehicle and reducing the need to ask others for information.

Mobile phone apps provided individuals with ASD travel route information on quick changes that often occurs in traffic information (6, 8) including real-time information on the time of arrival (6) and stops on the journey (3). Apps allowed the traveller’s location to be monitored by a carer and/or professional. When unexpected events happened, information on how to adjust a trip was needed (3). Participants described sourcing online information for planning via mobile apps to manage and make decisions about their trips, mostly by planning ahead (8–9), receiving real-time updates, or viewing travel routes and arrival timings during the journey (6). Individuals with ASD especially lacked information about crowded trains (3), and suggestions on other travel options in case of crowdedness. Information on crowding could facilitate planning a journey by providing e.g. information on standing room availability and seat availability ahead of a trip (3) and enabling individuals with ASD to foresee and avoid crowded services and journeys, which could reduce uncertainty during the journey (3).

4.2.2. Electronic ticketing

Several studies identified difficulties buying tickets and deciding on the type of ticket to buy (1–2, 8), sometimes due to financial reasons (11). Several aspects that made public transport journeys easier were mentioned in the studies including electronic ticketing, which made travel payments both more convenient and simpler (1–2, 8), and paying for fares before travel (1), which reduced the need for stressful social interactions. These aspects were often underpinned by having the self-confidence to undertake and begin the journey successfully rather than having the ability to travel or to buy public transport tickets from machines per se.

4.3. Stage 2–4: set of from origin, walk to stop, wait

Most travel journeys included an element of walking, for example from the origin to the bus stop, to the railway station, or to a car and then waiting for the bus/train to arrive. Most studies focus on how accessibility in the built environment influenced individuals with ASD departure from the origin. Key aspects described in the studies regarding departure from the origin included difficulties getting to the bus stop or train station without help (1, 3) having to combine different means of transport to get to the destination (9). Also, described in the studies were difficulties moving in the built environment by crossing the road and navigating in environments that were unfriendly for pedestrians (1). Other difficulties with travelling the built environment included wayfinding because of challenges understanding information from signposts and other visual clues, the need to have the confidence to travel alone (1), as well as low awareness of dangerous situations (6). One study reported that public transportation services were not available when needed, or not available to certain destinations, or were not reliable (9). Furthermore, inaccessible entrances, few elevators, inaccessible transport vehicles and bus stops (6, 10) and crowdedness in stations (3) were described as hindering use of public transport (8) for individuals with ASD.

4.4. Stage 5: board

Difficulties boarding a bus and/or train were mostly described in the studies in relation to home to school transportation (5–6, 10). The studies identified the need for support for children with ASD with verbal communication difficulties when boarding a vehicle with an unknown driver and/or unknown passengers (5–6). Strategies used to enable safe boarding described in the studies included bus roll-sheet/lists, name tags, parents and/or teachers putting the child on the bus or saying the child’s name to the driver (5–6). Unpredictability of train/bus arrival timings and the uncertainty concerning the arrival of the bus/train (Will it arrive on time? Where is it now? How far away is it?) (3, 6) was described as causing emotional distress in several studies (6, 8–9). Missing the bus/train in the morning resulted in significant others having to drive the person to the destination (1, 4–5).

4.5. Stage 6: time in vehicle

This theme was characterised by safety concerns and sensory overload difficulties.

4.5.1. Concerns about safety aspects

Several studies raised concerns about traffic safety and crime on public transport (1, 5–6, 9). Parents expressed concerns about their children being left on the bus because of lack of verbal communication (5) and, the drivers’ friendliness and helpfulness and whether they would take care of the children as passengers (1, 6, 9). Other passengers’ treatment of individuals with ASD was also raised as a concern in one study (6). Furthermore, concerns about how the individual would be treated by others (6, 9), having to deal with unfamiliar people (2), crowdedness on the vehicle (3), proximity to others and the risk of being touched by others (2) were raised as concerns.

4.5.2. Sensory overload

Sensory overload issues reported for individuals with ASD in the studies were balance and motion sickness (3), disturbing noise in public transport vehicles (2, 8), claustrophobia (in public transport vehicles) (8), tactile sensations (6, 8) and lights and smell (6). Sensory overload issues including noise, smell, and touch, together with the need for personal space, fear of unwanted social contact, and information overload (2–3, 6), influenced the preferred mode of transport, and the chosen time of travel as well as the choice of seating (1, 3, 6) such as a quiet train carriage, seating by the window or the front or rear end of the vehicle, based on preference (3–4, 6, 9).

4.6. Stage 6–9: alight, leave stop/station and arrive at destination

Studies have reported that travelling with public transportation requires stepping out of the vehicle and walking to make a transfer or to a destination by interacting with the physical built environment (3, 5, 8). Individuals with ASD experienced difficulties getting on or off trains or buses (3, 5, 8), were afraid of missing the right stop to get off (2–3) and requires information on how close the vehicle was to the stop (3, 10). Inaccessible bus stops were also mentioned (8) but it was unclear in what way.

Several safety issues regarding walking from the station/stop to the destination were raised in the studies. Fears of being assaulted when walking from the station/stop were reported (5), as well as fears of not arriving at the final destination (3–6). One study highlighted the need for information on safe roads to cross (3). Strategies and tools such as using handwritten directions, learning the travel route visually in case individuals forgot street names, and memorising landmarks were described in the studies as useful in finding the way when stepping out of the vehicle (1, 3).

5. Discussion

In this scoping review, the whole journey chain perspective (Park & Chowdhury, Citation2018) was used to systematically identify different parts of an individual’s journey in public transport related to physical, social, and psychological facilitators. What was found, and which complements Park & Chowdhury´s whole journey chain perspective, was a planning phase that occurs long before the journey commences. This pre-stage involves planning and preparation, such as scheduling departure times a few days in advance or acquiring knowledge and information about train travel. Thus, there is a planning stage that is significant for embarking on a journey for individuals with ASD, preceding the first step in the whole journey chain, namely information-seeking as described by Park and Chowdhury (Citation2018).

This planning phase consists of an overall planning for a life as a traveller for individuals with ASD and starts with deciding if the journey is even worth the effort and having the confidence to leave home to make a journey. Findings from earlier studies by Chowdhury and Ceder (Citation2013), has highlighted the importance of individuals’ perceived confidence in themselves to make transfers with public transport successfully with ease. Deciding to travel is followed by careful planning and practising of the route and modes of transport to ensure that individuals reach their destination. Individuals with ASD may face unique challenges when using public transportation, due to cognitive symptoms commonly associated with their disorder making careful planning essential to ensure a smooth and comfortable travel experience (Precin et al., Citation2012). For example, careful planning for individuals with ASD involves addressing sensory sensitivities by consideration of quieter times for travelling, less crowded routes, or support to ease sensory overload (Precin et al., Citation2012; Davidson & Pfeiffer, Citation2024). Further, planning for travelling also includes consideration of alternative routes, allowing extra time for potential delays, and having contingency plans in case of unexpected disruptions (Sheppard et al., Citation2010). Manning et al. (Citation2023) suggests providing maps in various formats, in particular sensory to make spaces more predictable for individuals with ASD.

Findings of this study point to the need to include the phase of planning for becoming a traveller in discussions on the whole journey chain, especially as it may be argued that the significance of the journey, in addition to the level of confidence in independent travelling, and the amount of planning and preparation needed, may influence whether people with ASD travel by public transport at all. The level of planning required for people with ASD to make a smooth journey is important to consider in transport policy and planning as well as other policy arenas such as the labour market, education, and the built environment. Especially as the restricted mobility people with ASD face in using public transport as reported in this study can lead to further isolation, home-bound occupations, and dependency on friends and family which could negative effect vocational and educational outcomes and well-being (Deka, Citation2014; Ditchman et al., Citation2018).

Being able to travel by public transport independently implies several skills and experiences, which for most people occur unreflectively. For individuals with ASD, travelling by public transport involves several barriers and challenges which have been identified in this scoping review. Factors within the transport system that complicate travel concerned changes in timetables, understanding routes and changes in routes, lack of general information, crowding, and unknown masses of people. Seeking and gathering information during the whole journey chain (Park & Chowdhury, Citation2018) caused a series of problems for individuals with ASD. Public transport is often unpredictable due to delays and variations in timings, and such information can be difficult to access for individuals with ASD who in many cases need a sense of predictability and control over the situation (Kersten et al., Citation2020). The need for sufficient information to be able to make decisions both during the pre-planning stage and throughout the whole journey was emphasised in several of the included articles. Thus, the findings point to the need to consider the step of seeking and gathering information as an overarching step influencing all other steps in the whole journey chain and not only as a precursor to the journey (Park & Chowdhury, Citation2018).

The findings reveal that perceptions of personal safety are of major importance for parents of children with ASD when travelling by public transport. Despite this, only limited research has focused on the influence of perceived safety on travel behaviour in public transport among individuals with cognitive or sensory disabilities (Park et al., Citation2023). The safety of people with disabilities using public transport often covers the steps of getting to a stop, waiting, boarding, getting off and walking to the destination, and are limited to individuals with motor disability (Bęczkowska & Zysk, Citation2021). However, this is not a complete picture and the findings of this study point to the need to consider the concept of public transport safety for people with ASD much more broadly. The findings show that the primary safety concerns about public transport for individuals with ASD resulted from the behaviour of other travellers, drivers, or bystanders. For people with ASD, the attitudes of others, including intolerance and discrimination by drivers and other passengers, having to deal with unfamiliar people, and closeness to others were found to influence the sense of personal safety during public transport use. A recent review article emphasised the significant influence of the general public's attitudes (including safety, fear, and perceptions of helpfulness by staff and riders) on individuals with disabilities, impacting their confidence, independence, security, and travel-related anxiety (Park et al., Citation2023). Other studies have shown that people with disabilities were subjected to interpersonal discriminatory experiences on public transport leading to avoidence of public transport due to for example fellow traveller or staff’s attitudes (Wayland et al., Citation2022). Additionally, individuals with invisible disabilities described being met by staff with aggression and confrontational behaviour when choosing to disclose their disability on public transport, increasing the risk of sending individuals to a very difficult path of consoling their disabilities (Wayland et al. Citation2022). Previous studies have underscored the importance of implementing guidelines and policies, such as enhanced lighting at bus stops, accessible wayfinding and comprehensive staff training (Bezyak et al., Citation2020; Park et al., Citation2023; Pfeiffer et al., Citation2020), as means to foster a sense of safety, alleviating fear, and enhancing perceptions of helpfulness for both staff and riders supporting individuals with ASD. Also, increased public awareness on interpersonal discrimination related barriers to travel have been highlighted (Wayland et al., Citation2022). Furthermore, overcrowded vehicles and crowded stops and stations were described as barriers to the sense of safety of users with ASD on public transport. Other studies have found that stress and anxiety in crowded situations, and unpleasant people-to-people meetings influenced the sense of safety among individuals with disabilities (Bęczkowska & Zysk, Citation2021). Efforts that reduce contact with other passengers, directly by limiting the number of passengers in vehicles or indirectly by operating with large vehicles have been described as means to make users feel safe while travelling (Lucchesi et al., Citation2022). This also has implications for the provision of travel information for people with ASD as information on crowdedness in vehicles during the planning phase as well during transfer has the potential to increase the sense of safety of people with ASD during a journey by public transport. Therefore, it is essential to identify which variables contribute to the feeling of security and control of individuals with ASD while travelling on public transport, and to clarify what information is necessary to make them feel safe during commuting.

5.1. Conclusions

Taking the whole journey perspective into account, the aim of this study was to synthesise knowledge on the experiences of public transport use among individuals with ASD or ADHD. The scoping review suggests expanding the whole journey chain perspective to include a pre-planning stage for individuals with ASD before embarking on a journey. This phase involves deciding if the journey is worth the effort, building confidence to leave home, and meticulous planning and practicing of the route and modes of transport. The significance of the journey, level of confidence, and the amount of pre-planning needed may influence whether individuals with ASD choose to travel by public transport at all. Failure to address the planning requirements for individuals with ASD may lead to restricted mobility, isolation, and dependence on others, affecting vocational, educational, and overall well-being outcomes.

Further, there is a need for a comprehensive understanding of the safety concerns faced by individuals with ASD during public transport travel and the importance of addressing public attitudes as crucial aspects to enhance the overall travel experience for individuals with ASD. Safety concerns extend beyond physical disabilities and encompass the behaviour of other travellers, drivers, and bystanders. Attitudes of others, including intolerance and discrimination, significantly impact the sense of safety for individuals with ASD.

5.2. Recommendations for future research

The study recommends further research on the impact of public attitudes towards individuals with ASD, the design of public transport facilities to enhance safety and early identification and effective interventions to address safety concerns experienced by individuals with ASD.

Despite the highlighted importance of information seeking and gathering as the first step in the whole journey chain, as described by Park and Chowdhury (Citation2018), we found an overarching pre-planning stage that occurs long before the journey commences. Given the extensive need for planning and preparation for individuals with ASD, it is urgent to consider the step of seeking and gathering information as an overarching step influencing all other steps in the whole journey chain and not only as a precursor to the journey.

Second more evidence is needed regarding the impact of the general public's attitudes (e.g. perceptions of helpfulness by staff and riders) on confidence, security, and travel-related anxiety of individuals with ASD. There is a great need for emphasis on the design of public transport facilities and public spaces (buses/trains, seats, platforms and waiting halls) to increase the sense of safety for travellers with ASD, and assist them with information-seeking, comprehension of information and recovery between journeys. Further, training staff on non-visible disabilities may help people with ASD feel safer and more confident when using public transport, which warrants further research.

5.3. Methodological considerations

Several limitations need to be acknowledged. The scoping review included published and peer-reviewed research, with no grey literature being included. Most studies that were found in the search concerned individuals with autism. Only one study focused solely on individuals with ADHD, which implies that the transport situation is unnoticed among people with ADHD and there is a risk that perceived barriers that prevent them from travelling cannot be considered in policies and planning concerning public transport and infrastructure. One of the limitations concerns the small number of articles and participants, highlighting the scarcity of research on this topic. The seemingly small number of articles found in the initial search (n = 54) may be a result of few studies considering public transport as a certain means of transport for people with ASD or ADHD. The narrow search criteria for scientific, peer-reviewed literature, excluding grey literature, may also explain the low number. More articles could have been retrieved using a wider time span, although with the rapid development in all sectors of society today due to digitalisation the decision was to embrace the latest 10 years to include the most recent research. The included articles tend to emphasise and describe the barriers encountered during the whole journey chain rather than considering interventions on how to encounter these difficulties.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5™ (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

- Angell, A. M., & Solomon, O. (2018). Understanding parents’ concerns about their children with autism taking public school transportation in Los Angeles County. Autism, 22(4), 401–413. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361316680182

- Baric, V. B., Hemmingsson, H., Hellberg, K., & Kjellberg, A. (2017). The occupational transition process to upper secondary school, further education and/or work in Sweden: As described by young adults with Asperger syndrome and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 47(3), 667–679. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-016-2986-z

- Barkley, R. A. (Ed.). (2014). Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. A handbook for diagnosis and treatment (4th ed.). The Guilford Press.

- Bęczkowska, S. A., & Zysk, Z. (2021). Safety of people with special needs in public transport. Sustainability (Switzerland), 13(19), 10733. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131910733

- Berg, J., & Ihlström, J. (2022). Experiences of public transport among people with neuropsychiatric disabilities [Sw: Erfarenheter och upplevda hinder i kollektivtrafiken hos personer med neuropsykiatriska funktionsnedsättningar]. Statens väg-och transportforskningsinstitut.

- Bezyak, J. L., Sabella, S. A., & Gattis, R. H. (2017). Public transportation: An investigation of barriers for people with disabilities. Journal of Disability Policy Studies, 28(1), 52–60. https://doi.org/10.1177/1044207317702070

- Bezyak, J. L., Sabella, S., Hammel, J., McDonald, K., Jones, R. A., & Barton, D. (2020). Community participation and public transportation barriers experienced by people with disabilities. Disability and Rehabilitation, 42(23), 3275–3283. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2019.1590469

- Carver, A., Timpero, A., & Crawford, D. (2008, June). Playing it safe: the influence of neighbourhood safety on children’s physical activity. A review. Health Place, 14(2), 217–227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2007.06.004

- Cele, S. (2006). Communicating place: Methods for understanding children's experience of place [Doctoral dissertation]. The Department of Human Geography, Stockholm University. https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:186613/FULLTEXT01.pdf

- Chowdhury, S., & Ceder, A. (2013). A psychological investigation on public-transport users’ intention to use routes with transfers. International Journal of Transportation, 1(1), 1–20. http://dx.doi.org/10.14257/ijt.2013.1.1.01

- Clayton, W., Parkin, J., & Billington, C. (2017). Cycling and disability: A call for further research. Journal of Transport & Health, 6, 452–462. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jth.2017.01.013

- Darcy, S., & Burke, P. F. (2018). On the road again: The barriers and benefits of automobility for people with disability. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 107, 229–245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2017.11.002

- Davidson, A., & Pfeiffer, B. (2024). Community participation challenges for young adults with autism spectrum disorders during COVID-19 A photovoice study. Community Mental Health Journal, 60(1), 60–71. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-023-01199-7

- Davidsson, P., Hajinasab, B., Holmgren, J., Jevinger, Å, & Persson, J. A. (2016). The fourth wave of digitalization and public transport: Opportunities and challenges. Sustainability, 8(12), 1248. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8121248

- Deka, D. (2014). The role of household members in transporting adults with disabilities in the United States. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 69, 45–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2014.08.010

- Deka, D., Feeley, C., & Lubin, A. (2016). Travel patterns, needs, and barriers of adults with autism spectrum disorder: Report from a survey. Transportation Research Record, 2542(1), 9–16.

- Ditchman, N. M., Miller, J. L., & Easton, A. B. (2018). Vocational rehabilitation service patterns: An application of social network analysis to examine employment outcomes of transition-age individuals with autism. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin, 61(3), 143–153. https://doi.org/10.1177/0034355217709455

- Durand, A., Zijlstra, T., van Oort, N., Hoogendoorn-Lanser, S., & Hoogendoorn, S. (2022). Access denied? Digital inequality in transport services. Transport Reviews, 42(1), 32–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/01441647.2021.1923584

- Egard, H., Hansson, K., & Wästerfors, D. (Eds.). (2022). Accessibility denied: Understanding inaccessibility and everyday resistance to inclusion for persons with disabilities (p. 232). Taylor & Francis.

- Falkmer, M., Barnett, T., Horlin, C., Falkmer, O., Siljehav, J., Fristedt, S., Lee, H. C., Chee, D. Y., Wretstrand, A., & Falkmer, T. (2015). Viewpoints of adults with and without Autism Spectrum Disorders on public transport. Transportation Research Part A, 80, 163–183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2015.07.019

- Falkmer, T., Horlin, C., Dahlman, J., Dukic, T., Barnett, T. (2014). Usability of the SAFEWAY2SCHOOL system in children with cognitive disabilities. European Transport Research Review, (6), 127–137.

- Flamm, M., & Kaufmann, V. (2006). Operationalising the concept of motility: A qualitative study. Mobilities, 1(2), 167–189. https://doi.org/10.1080/17450100600726563

- Garg, R., Muhammad, S. N., Cabassa, L. J., Mcqueen, A., Verdecias, N., Greer, R., & Kreuter, M. W. (2022). Transportation and other social needs as markers of mental health conditions. Journal of Transport and Health, 25, 101357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jth.2022.101357

- Gough, K. V. (2008). ‘Moving around’: The social and spatial mobility of youth in Lusaka. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography, 90(3), 243–255. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0467.2008.290.x

- Hillman, M., Adams, J., & Whitelegg, J. (1991). One false move … a study of children's independent mobility. The Town Planning Review, 62, 264–265.

- Hsieh, H. F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687

- Jakobsen, J. C., Gluud, C., Wetterslev, J., & Winkel, P. (2017). When and how should multiple imputation be used for handling missing data in randomised clinical trials – a practical guide with flowcharts. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 17(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-017-0442-1

- Jones, P., & Lucas, K. (2012). The social consequences of transport decision-making: Clarifying concepts, synthesising knowledge and assessing implications. Journal of Transport Geography, 21, 4–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2012.01.012

- Kersten, M., Coxon, K., Lee, H., & Wilson, N. J. (2020). Independent community mobility and driving experiences of adults on the autism spectrum: A scoping review. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 74(5), 7405205140p1–7405205140p17. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2020.040311

- Krefting, L. (1991). Rigor in qualitative research: The assessment of trustworthiness. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 45(3), 214–222. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.45.3.214

- Lim, P. Y., Kong, P., Cornet, H., & Frenkler, F. (2021). Facilitating independent commuting among individuals with autism - A design study in Singapore. Journal of Transport and Health, 21, 101022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jth.2021.101022

- Lindqvist, R., & Lundälv, J. (2012). Participation in work life and access to public transport - Lived experiences of people with disabilities in Sweden. The Australian Journal of Rehabilitation Counselling, 18(2), 148–155. https://doi.org/10.1017/jrc.2012.15

- Lubin, A., & Feeley, C. (2016). Transportation issues of adults on the autism spectrum: Findings from focus group discussions. Transportation Research Record, 2542(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.3141/2542-01

- Lucas, K. (2012). Transport and social exclusion: Where are we now? Transport Policy, 20, 105–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2012.01.013

- Lucas, K., & Jones, P. (2009). The car in British society. The RAC foundation for motoring.

- Lucchesi, S. T., Tavares, V. B., Rocha, M. K., & Larranaga, A. M. (2022). Public transport COVID-19-safe: New barriers and policies to implement effective countermeasures under user’s safety perspective. Sustainability, 14(5), 2945–2945. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14052945

- Mackett, R. L., & Thoreau, R. (2015). Transport, social exclusion and health. Journal of Transport & Health, 2(4), 610–617. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jth.2015.07.006

- Manning, C., Williams, G., & MacLennan, K. (2023). Sensory-inclusive spaces for autistic people: We need to build the evidence base. Autism, 27(6), 1511–1515. https://doi.org/10.1177/13623613231183541

- Mao, X., & Chen, L. (2022). “To go, or not to go, that is the question”: Perceived inaccessibility among individuals with disabilities in Shanghai. Disability & Society, 37(10), 1659–1677. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2021.1899897

- Martel, A., Day, K., Jackson, M. A., & Kaushik, S. (2021). Beyond the pandemic: The role of the built environment in supporting people with disabilities work life. Archnet-IJAR: International Journal of Architectural Research, 15(1), 98–112. https://doi.org/10.1108/ARCH-10-2020-0225

- Marzi, I., & Reimers, A. K. (2018). Children’s independent mobility: Current knowledge, future directions, and public health implications. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(11), 2441. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15112441

- Neven, A., & Ectors, W. (2023). “I am dependent on others to get there”: Mobility barriers and solutions for societal participation by persons with disabilities. Travel Behaviour and Society, 30, 302–311. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tbs.2022.10.009

- Park, J., & Chowdhury, S. (2018). Investigating the barriers in a typical journey by public transport users with disabilities. Journal of Transport & Health, 10, 361–368. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jth.2018.05.008

- Park, K., Esfahani, H. N., Long Novack, V., Sheen, J., Hadayeghi, H., Song, Z., & Christensen, K. (2023). Impacts of disability on daily travel behaviour: A systematic review. Transport Reviews, 43(2), 178–203. https://doi.org/10.1080/01441647.2022.2060371

- Peters, M. D. J., Godfrey, C., & McInerney, P. (2020). Chapter 11: Scoping reviews (2020 version). In E. Aromataris & Z. Munn (Eds.), JBI manual for evidence synthesis (pp. 408–452). JBI. https://synthesismanual.jbi.global.

- Pfeiffer, B., Sell, A., & Bevans, K. B. (2020). Initial evaluation of a public transportation training program for individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities: Short report. Journal of Transport & Health, 16, 100813–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jth.2019.100813

- Precin, P., Otto, M., Popalzai, K., & Samuel, M. (2012). The role for occupational therapists in community mobility training for people with autism spectrum disorders. Occupational Therapy in Mental Health, 28(2), 129–146. https://doi.org/10.1080/0164212X.2012.679533

- Rezae, M., Mcmeekin, D., Tan, T., Krishna, A., Lee, H., & Falkmer, T. (2019). Public transport planning tool for users on the autism spectrum: from concept to prototype. Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology, 16(2), 177–187. https://doi.org/10.1080/17483107.2019.1646818

- Risser, R., Lexell, E. M., Bell, D., Iwarsson, S., & Ståhl, A. (2015). Use of local public transport among people with cognitive impairments – a literature review. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour, 29, 83–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trf.2015.01.002

- Rye, T., & Hrelja, R. (2020). Policies for reducing car traffic and their problematisation. Lessons from the mobility strategies of British, Dutch, German and Swedish cities. Sustainability, 12(19), 8170. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12198170

- Schoeppe, S., Duncan, M. J., Badland, H. M., Oliver, M., & Browne, M. (2015). Associations between children׳s active travel and levels of physical activity and sedentary behavior. Journal of Transport & Health, 2(3), 336–342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jth.2015.05.001

- Schwanen, T., & Ziegler, F. (2011). Wellbeing, independence and mobility: An introduction. Ageing and Society, 31(5), 719–733. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X10001467

- Sharples, R. (2017). Travel competence: Empowering travellers. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour, 44, 63–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trf.2016.09.013

- Sheppard, E., Ropar, D., Underwood, G., & van Loon, E. (2010). Brief report: Driving hazard perception in autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40(4), 504–508. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-009-0890-5

- Thériault, W., & Morales, E. (2022). Accessibility and social particiation in urban settings for people with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) or an intellectual disability (ID). Journal of Accessibility and Design for All, 12(1), 155–179. https://doi.org/10.17411/jacces.v12i1.352

- Trafikanalys. (2019). Public transport barriers – mapping of obstacles in the availability of public transport for people with disabilities [Sw: Kollektivtrafikens barriärer – kartläggning av hinder i kollektivtrafikens tillgänglighet för personer med funktionsnedsättning]. Rapport 2019:3.

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O'Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D. J., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson, M. G., Garritty, C., … Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473. https://doi.org/10.7326/m18-0850

- van Exel, N. J. A., & Rietveld, P. (2009). Could you also have made this trip by another mode? An investigation of perceived travel possibilities of car and train travellers on the main travel corridors to the city of Amsterdam, The Netherlands. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 43(4), 374–385.

- Villanueva, K., Giles-Corti, B., Bulsara, M., Trapp, G., Timperio, A., McCormack, G., & Van Niel, K. (2014, January 1). Does the walkability of neighbourhoods affect children's independent mobility, independent of parental, socio-cultural and individual factors? Children's Geographies, 12(4), 393–411. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733285.2013.812311

- Visnes ��ksenholt, K., & Aarhaug, J. (2018). Public transport and people with impairments – exploring non-use of public transport through the case of Oslo, Norway. Disability & Society, 33(8), 1280–1302. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2018.1481015

- Wayland, S., Newland, J., Gill-Atkinson, L., Vaughan, C., Emerson, E., & Llewellyn, G. (2022). I had every right to be there: Discriminatory acts towards young people with disabilities on public transport. Disability & Society, 37(2), 296–319. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2020.1822784

- Wilson, N. J., Stevens, A., Srasuebkul, P., Kersten, M., Lin, Z., & Trollor, J. N. (2021). Exploring the relationship between community mobility and quality of life, employment and completing further education for autistic adults. Journal of Transport and Health, 22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jth.2021.101117