ABSTRACT

Transport policies affect the quality of life and social wellbeing of citizens and communities; incorporating such impacts in policy and decision making, however, remains a challenge. This paper aims to: (1) present a systematic literature review that links transport policy to Community Wellbeing using the Capability Approach by Sen and Nussbaum, and (2) using that basis, establish a theoretical framework to systematically address Community Wellbeing impacts of municipal transport policies. This can improve qualitative assessments of policy interventions on multiple dimensions, such as safety, health, the (built) environment and accessibility, and inequalities within those dimensions. Using existing literature on the Capability Approach, Community Wellbeing dimensions can indeed successfully be integrated in transport policies. Additional tools and theories, such as the Theory of Change, are needed to structure relations between the sociotechnical transport system and the policy process. For analyses and assessment of policy interventions, additions from the affordances theory, potential accessibility, activity spaces, and sufficientarianism are needed to finalise the framework. Further development and testing of the framework is recommended. The most prominent research gaps are processes to set thresholds for sufficient accessibility, as well as potential limits to mobility behaviours through collective capabilities.

1. Introduction

Transport policy professionals are increasingly challenged to include quality of life, health, safety and environmental objectives in transport policies (Akse et al., Citation2021; Sunio et al., Citation2023). Also, accessibility, particularly its fair distribution, rather than providing maximal mobility, is recently emerging as a concern of several national and regional transport policies (e.g. Ministerie van Infrastructuur en Waterstaat, Citation2023; New Zealand Government, Citation2020; Norwegian Ministry of Transport, Citation2021; Scottish Government, Citation2022; Trendbureau Drenthe, Citation2021). Having to do with notions of individual and collective wellbeing on the one hand, and being the subject of public policies on the other, the term “community wellbeing” (CWB) is associated with this idea. CWB is often defined by scholars as “ … the combination of social, economic, environmental, cultural and political conditions identified by individuals and their communities as essential for them to flourish and fulfil their potential” (Wiseman & Brasher, Citation2008, p. 358). More specific operationalisations of CWB for the context of transport planning have not been found, however Alidoust et al. (Citation2022) reveal that many city planning policies that look into CWB contain transport and land use measures. Still, real-life municipal transport plans are slowly adapting (Akse et al., Citation2023), although municipalities do ask for practical knowledge to accelerate this effort (CROW-KpVV, Citation2022). For that purpose, policymakers must be enabled to evaluate whether transport policies meet CWB requirements, including fairness issues. This paper aims to create a common ground to operationalise CWB in transport policy evaluations, based on the Capability Approach (CA). To meet this aim, it provides a systematic literature review on CA in the transport domain, creating a theoretical CA framework to evaluate integrated transport policies, including the municipal level. The CA is used here because it is conceived to specifically assess multiple dimensions of people’s lives, including distributive issues such as sufficiency, fairness and justice (Nussbaum, Citation2000; Sen, Citation1979, Citation1985). The paper contributes to the literature, as, in previous studies, the link between CWB and transport policies through a CA lens has not been made explicit yet (Figure 1).

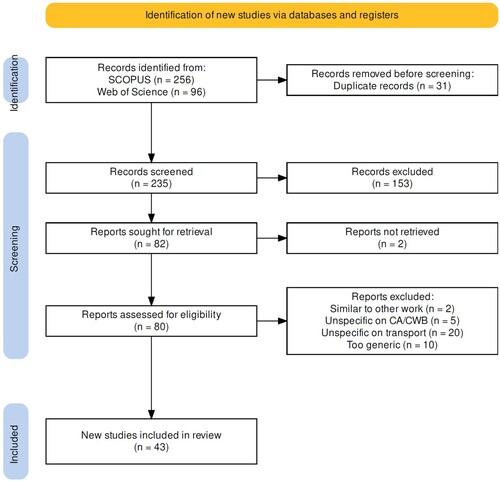

Figure 1. Literature review process (Haddaway et al., Citation2022).

In short, the CA describes aspects of wellbeing by looking at one’s combined conversion factors, determining one’s ability to convert available resources into a real capability set, of which one has the freedom to choose functionings. Functionings are the beings and doings that one has reason to value, and which eventually contribute to one’s wellbeing (Alkire, Citation2008; Gasper, Citation2007; Robeyns, Citation2005). The well-known example of a “bicycle as a resource” requires conversion factors, such as the ability to ride a bicycle, as well as proper infrastructure, to convert the resource into the capability of being mobile (Robeyns, Citation2005, Citation2017). If public transport is also available, the individual capability set and freedom to choose increase. Within the transport domain, there is extensive literature on the CA, rendering several frameworks for transport research and/or policy evaluation purposes. However, the interpretations and operationalisations of the CA differ greatly in the literature, as also pointed out by Akhavan and Vecchio (Citation2018). This makes it difficult to construct a uniform method to evaluate transport policies in terms of CWB. To reach some common ground, the research questions are:

How can the CA be used to connect transport policies to CWB?

How can existing studies on the CA and CWB in the transport domain be integrated in a generic framework to evaluate transport policies?

What are the implications of the theoretical framework for local transport policymaking, in particular for setting sufficiency thresholds?

Section 2 gives an overview and categorisation of academic literature on how transport research is related to CWB and the CA, leading to a proposed transport policy evaluation framework in section 3, where it is further elaborated. Section 4 discusses the question of thresholds-setting for sufficient accessibility, related to other CWB dimensions (health, safety and sustainability). Section 5 concludes, answering the research question with recommendations for further research and policy implementations.

2. Literature review

2.1. Method

A systematic literature review was carried out using the PRISMA (Citation2020) statement in March 2023, using the following search strings, no settings changed ():

SCOPUS: [“TITLE-ABS-KEY ((“community wellbeing” OR “community well-being” OR “capability approach” OR “capabilities approach”) AND (transport* OR accessibility) AND (theor* OR framework*))”]

Web of Science: [“(TS = (“capability approach”) OR TS = (“capabilities approach”)) AND (TS = (transport*) OR TS = (accessibility))”]

2.2. CA and justice approaches: choosing a structure

The potential of the CA as an ethical and justice-related philosophical base for transport policy analysis has been pointed out before, advocating for further research (Martens, Citation2017, p. 135, 136; van Wee, Citation2011, pp. 30–32). The found articles seem to have taken up that challenge, now covering over a decade of CA-based transportation research. Most use the generic model of Robeyns (Citation2005, Citation2017) to structure conceptual frameworks. In this paper, such an adaptation by Vecchio and Martens (Citation2021) is the baseline for further development. It was chosen for its straightforward contextualisation to the transport system, and for the addition of feedback and feedforward loops reflecting the dynamics between individual experiences and conversion factors. Their model incorporates the direct effects of “freedom of accessibility and mobility” on one’s wellbeing, linking it to the question whether thresholds for “sufficient accessibility” can and should be formulated. Their interpretation, however, focuses on individual wellbeing rather than community aspects of transport and accessibility issues. This is problematic since individual mobility behaviour bidirectionally relates to other, sometimes collective, capabilities of groups within society (Setti & Garuti, Citation2018). An improvement on the framework should, thus, allow for the distinction for individual and collective capabilities and wellbeing. For the purpose of this paper, a framework should also make clear where policy interventions should be placed in order to allow for (qualitative) policy evaluations. Following that the process of public reasoning is a form of collective capability, transport policies are here placed externally (Leßmann, Citation2020; Trani et al., Citation2011), rather than Randal et al. (Citation2020) who view policy as a social conversion factor. The literature furthermore shows that achieved mobility and accessibility functionings are usually separated from the wellbeing outcomes (Ryan et al., Citation2019; Vecchio & Martens, Citation2021). This separation coincides with the requirement that a policy evaluation framework explicates causal relations (Egessa et al., Citation2018; Hoogerwerf, Citation1990) and also that transport and mobility are not ultimate ends (Robeyns, Citation2017). This will be further detailed in the next paragraphs, making use of the literature as listed in Appendix 1.

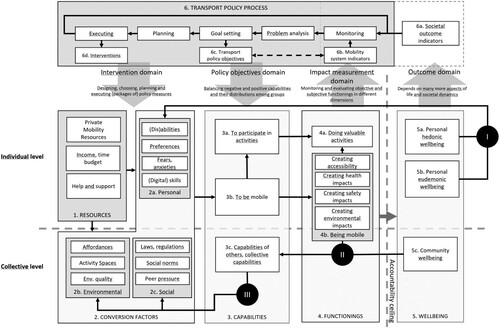

3. The CWB framework

Robeyns (Citation2017) describes in detail how a capability theory is generally constructed, giving insight in the shortcomings of the base framework by Vecchio and Martens (Citation2021) if it is to be applied in the praxis of transport policies. This mainly has to do with how resources and conversion factors are distinguished, making it hard to assess the completeness of policy intervention packages. Re-introducing Robeyns’ three types of conversion factors and separating functionings from wellbeing effects reveals analogies to the structure of the Theory of Change (ToC) methodology, earlier pointed out by Egessa et al. (Citation2018). It also opens the possibilities to discuss which domain-specific knowledge is relevant for the elements of the framework. Examples of such operationalisations are mentioned in . In the next paragraphs, each element and relation will be further explained. The numbers in the figure correspond to the “Element” column in Appendix 1.

Figure 2. The theoretical CA framework to evaluate integrated transport policies, based on Robeyns (Citation2005), adapted by Vecchio and Martens (Citation2021) and Egessa et al. (Citation2018).

3.1. The basic framework in a policymaking context

3.1.1. Resources and conversion factors (, blocks 1 and 2)

Many effects of mobility, accessibility, or its absence, correlate with personal, environmental, and social attributes and circumstances of individuals within their community. The CA calls these “resources” and “conversion factors” (Robeyns, Citation2005). Public policies intervene here, affecting individuals and communities directly and indirectly, ultimately leading to wellbeing effects. Policymakers need to assess if interventions contribute to policy objectives efficiently and effectively, without creating adverse effects, whilst maintaining a sense of proportionality (Givoni, Citation2014; van der Doelen & Klok, Citation1978/Citation1989; Vedung, Citation1998).

Although most literature acknowledges that material, personal, environmental, and social influences and constraints contribute to one’s capabilities, the term “conversion factor” is only explicitly used in about 30% of the literature. Some argue that this distinction is unnecessary (Azmoodeh et al., Citation2022). Most state that it suffices to separate personal and environmental attributes. This might be adequate for studies that focus on accessibility outcomes for specific groups or individuals (Lucas et al., Citation2019; Mitra, Citation2006; Vecchio & Martens, Citation2021). Policies, however, can be aimed both at the individual and/or the collective, and be social or technical in nature, all within the public socio-technical system (Marks, Citation2002). When plotted in quadrants, this again renders the four input types of the CA (blocks 1 and 2 in ).

Resources (block 1) are defined as all “technical” or “instrumental” objects and personal services, related to an individual. This is a narrower definition than e.g. Cooke et al. (Citation2022) who integrate resources and capabilities, or Luz and Portugal (Citation2021), Ryan et al. (Citation2019), Humberto et al. (Citation2020), and Azmoodeh et al. (Citation2022), who consider all potential input variables to be resources. The most common approach in the literature is to see “resources” as personal means of transport, (e.g. vehicle ownership, driver’s licence, transit subscription cards, etc.), including financial means to travel, and time budget resources (Inoi & Nitta, Citation2005; Kita et al., Citation2017; Nahmias-Biran & Shiftan, Citation2019). Even help and support from others can be considered a resource (Cao & Hickman, Citation2019a) which is dependent on the commitment and capabilities of others (Leßmann, Citation2020). In short, an individual can have, hold or use a resource, with (constrained) choices to do this or not. This relates resources mainly to individual and economic policy instrument types, such as subsidies, taxes, or the provision of aiding equipment or personal services.

Conversion factors (block 2), cannot be chosen to use, transform, or invoke; they are “given” attributes of a person in their particular circumstances. The literature diverges when defining transport-related conversion factors, often not mentioning them explicitly. Most studies describe types of (implicit) conversion factors. For example, Shin (Citation2011) studied the social constraints on mobility from the context of Christian Korean immigrant women in the United States. Goodman et al. (Citation2014) showed that the policy intervention of free bus travel for young people (resource) enabled them to meet friends and travel together, strengthening their social conversion factor as a co-benefit. Sometimes, conversion factors are quantified as weighting functions in a model (Bantis & Haworth, Citation2020; Nahmias-Biran & Shiftan, Citation2019; Rashid & Yigitcanlar, Citation2015; Tabandeh et al., Citation2019), analogous to Kuklys (Citation2005) and Dagsvik (Citation2013).

Personal conversion factors (2a) are non-transferable attributes of an individual. These include physical and cognitive (in)abilities, (digital) skills, psychological and psychosocial aspects, such as attitudes, preferences and anxieties. The generic CA literature mentions many characteristics as personal conversion factors: being a parent, a provider of main income, a school going child, etc. They might change over time, but they are determined through circumstances and experiences (Kuklys, Citation2005). Feedback loop I accounts for this phenomenon.

Environmental conversion factors (2b) are the physical and digital environment around the individual.Footnote1 For the context of transport policy these are well explored, since they encompass most of the technical subsystem, historically being the main subject of transport policies. The CA literature on transport relates environmental conversion factors either to land use (the geographical dispersion of activities), or to the quality of public spaces, and much less for environmental factors such as air quality or social safety. However, these “subdimensions” of environmental conversion factors should also be further operationalised to be linked to specific policy interventions.

For the land-use related factors, the concept of “activity spaces” (Hägerstrand, Citation1970; Patterson & Farber, Citation2015) is mentioned by Chen and Akar (Citation2016), and Babb et al. (Citation2017), linking it to accessibility-as-a-capability (see paragraph 3.1.2). Implicit references to activity spaces are found in studies by Vallee et al. (Citation2020), letting people with different attributes delimit their own neighbourhood, and Akhavan and Vecchio (Citation2018), confronting mobility attributes of groups of elderly with neighbourhood typologies. If the term “activity location” is relaxed to also contain mobility-related hubs (public transport stops, shared mobility locations), then Sherriff et al. (Citation2020) include the availability of shared bicycles within the activity space domain.

The “affordances theory” by Gibson (Citation1979/Citation2014), cited by Babb et al. (Citation2017) and Lennon et al. (Citation2019) is noteworthy to discuss the quality of (public) spaces as a variable. Attributes of objects within one’s direct surroundings translate into potential uses (affordances). Enhanced capabilities through affordances (e.g. using a resting bench as exercise equipment) are often overlooked from the cost-driven paradigm of most maintenance policies. Affordances-related studies describe different attributes of (public) spaces that co-determine whether activities, or travel modes, can be part of one’s capability set. This includes assessments such as “walkability” (Blečić et al., Citation2015), “level of maintenance” (Lewis, Citation2011), “peripherality” (Blečić et al., Citation2020), green infrastructure (Larson et al., Citation2016), play and exercise (Babb et al., Citation2017; Carpenter, Citation2013), or the potential to meet other people (Goodman et al., Citation2014; Radomskaya & Bhati, Citation2022), which can also be associated with CWB aspects outside the transport domain.

Digital information technology, such as mobile internet services, is an additional environmental conversion factor. Digital information, on e.g. road closures and congestion, or possibilities to plan or book a trip or a shared vehicle, can be either constructive or inhibiting – an increasingly important factor for transport policy, potentially creating more inequalities in perceived accessibility (Durand & Zijlstra, Citation2020; Luz & Portugal, Citation2021).

Social conversion factors (2c) constitute formal and informal rules and regulations, including social norms, peer pressure, stigmatisation and forms of discrimination, affecting individuals or groups. These can be constraining as shown by Shin (Citation2011). A “reversed” interpretation of social conversion factors by Leßmann and Masson (Citation2015) sees social conversion factors as targets for policy interventions that stimulate sustainable consumption behaviour, derived from the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB, Ajzen, Citation1991). Adding this to the framework makes it possible to meet the requirement of Randal et al. (Citation2020) to include sustainability issues in CA-based transport policies. Consequentially, the TPB can then be useful in analysing the discrepancies between “hedonic” and “eudemonic” wellbeing outcomes that correspond to certain (collective) capabilities or functionings (also see Friman et al., Citation2018; Gasper, Citation2007).

3.1.2. Capabilities and functionings (blocks 3 and 4)

Resources and conversion factors combine into a capability set (3), from which an individual has the freedom to choose certain functionings (4). The more functionings one can choose, the higher the degree of choice freedom, or agency, is (Robeyns, Citation2005). Functionings and/or capabilities form the “evaluative space” for transport policy assessment. Although the literature is clear that a theoretical framework for transport policy should be able to deal with multidimensional assessments, the included studies do not list these dimensions explicitly. The link to the community level is seldomly mentioned, while from a CWB perspective, multidimensional evaluative spaces are very common: Alidoust et al. (Citation2022) identify 13 potential dimensions to analyse planning policies for cities. Van Wee (Citation2023) mentions “health”, “safety”, “environment”, and “accessibility” as most relevant for transport policy. Since the latter coincides the most with the CWB dimensions mentioned by Wiseman and Brasher (Citation2008), and since current policies in the Netherlands use the same dimensions (Snellen et al., Citation2021), these will be used further within this study.

3.1.2.1. Safety and health as capabilities

Safety and good health as capabilities in themselves and in general in a CA context have been well debated and studied over the recent decades (Alkire, Citation2016; Schramme, Citation2016; Venkatapuram, Citation2013). The CA literature for transportation research is limited on these dimensions, specifically when discussing the evaluative space (Carpenter, Citation2013; Hananel & Berechman, Citation2016; Lennon et al., Citation2019). In these cases, scholars focus on physical environments or modes that provide forms of exercise or mental health improvements. Most, however, treat being healthy as an input rather than a capability – a personal conversion factor (2a). Similar observations can be made of the capability of being safe, either from traffic accidents or crime as environmental and/or social conversion factors (Biagi et al., Citation2018; Luz & Portugal, Citation2021), versus the personal conversion factor of fearing to be killed or injured when traveling.

3.1.2.2. The environment as a capability

Like health and safety, the literature sees the physical environment mostly as an exogenous factor rather than a direct capability. Urban design scholars generally view it as a source of (in)justice and inequalities in terms of what places, the transport system, or policies do to people (Arenghi et al., Citation2021; Basta, Citation2015; Lennon et al., Citation2019; Lewis, Citation2011), implying that the living environment is a result of collective capabilities. Maintaining the earlier distinction between activity spaces and affordances, one might argue that activity space capabilities are part of the accessibility dimension (see next paragraph). On the other hand, one might say that by focusing on proximity, spatial planning policies address a specific capability to access valuable activities within sufficient time/cost budgets, while being independent of a car or public transport (Cooke et al., Citation2022). Viewing the (quality of) the built environment as a (collective) capability has consequences for dealing with externalities (see paragraph 3.3).

Cloutier et al. (Citation2019), studying CWB policies, conclude that stimulating eudemonic behavioural aspects, which are essential for the development of wellbeing on a community level, should be part of policy instruments. Enhancing environmental capabilities through the stimulation of “positive affordances” can increase the capabilities of e.g. disabled individuals to have access to valuable activities (Jónasdóttir et al., Citation2021). Positive affordances can help understand that being mobile is potentially a wellbeing-improving activity in itself (Carpenter, Citation2013; Radomskaya & Bhati, Citation2022), which creates potential for individuals to contribute to the community level. One’s environment can also contain “negative affordances”, such as crime rates, traffic safety, bad air quality, and noise pollution (Gibson, Citation1979/Citation2014). Here, individual capabilities such as being able to enjoy clean air, not being robbed or assaulted, et cetera are influenced by functionings on a community level. The transition towards transport policies that enhance sustainable capabilities is scarcely addressed in the CA and transport literature (Randal et al., Citation2020; Willberg et al., Citation2023). This gap can be closed, however, as further discussed in paragraph 3.3, from CA applications in other fields.

3.1.2.3. Accessibility as a capability

The general consensus in the literature is that accessibility-related capabilities contribute (in a positive or negative way) to a person’s and a community’s wellbeing. Three levels of capabilities are derived (Luz & Portugal, Citation2021):

Mobility as a capability (3b)

Accessibility as a capability

Participation as a capability (3a)

Most scholars agree that “mobility-as-a-capability” underestimates the importance of spatial proximity of activities. Being able to reach activities is considered more important than just being mobile, which should be reflected in the choice of which functionings and capabilities are addressed in transport policy. Another argument to discard mobility as the most important capability is, as Robeyns (Citation2017, p. 41) stresses, that capabilities are not necessarily positive contributions to the wellbeing of a person or a community: the capability of being discriminated, for example, is negative. Too much mobility has negative effects (Randal et al., Citation2020). Because individual accessibility generally positively contributes to wellbeing, this would be the preferred evaluative dimension for transport policies. One can then argue that policies can almost always strive for more (potential) accessibility, leaving room for the public debate on the consequences in terms of what is most beneficial for CWB, (realised) mobility and externalities. A downside for choosing the third level, participation as a capability, is that although it does reflect that better accessibility potentially contributes to a thriving community, these activities themselves depend on aspects that lie outside the scope of typical transport policies. Being too broad for a transport policy objective, it will, however, be informative to keep this “outcome” dimension in mind, as will be explained in paragraph 3.2.1.

This renders the level of accessibility to valuable activities as the preferred accessibility dimension for the evaluative space. The literature largely supports this stance, suggesting that potential accessibility, first coined by Hansen (Citation1959), and later refined (Akhavan & Vecchio, Citation2018; Geurs et al., Citation2010; Shen, Citation1998; Soukhov et al., Citation2023; van Wee, Citation2019; van Wee & Geurs, Citation2011) is a good indicator for accessibility-as-a-capability (Luz & Portugal, Citation2021). Further operationalisation of accessibility in a CWB context should therefore contain methods to analyse potential accessibility (see paragraph 3.2.1). Expanding one’s accessibility capability set can even be interpreted as increasing transport option values (Geurs et al., Citation2007; Kuklys, Citation2005), and also, any further improvement has a decreasing marginal gain (Nahmias-Biran & Shiftan, Citation2019), which may vary by type of destination (del Mar Parra López et al., Citation2022). Within the literature, the notion of accessibility as a means for people to be able to commit to the development of collective capabilities, such as volunteering as a school bus driver, is not explicitly found. The same goes for the idea that enhanced accessibility capabilities for specific groups, such as children or wheelchair users, reduces their dependence on forms of collective capabilities within the community.

3.1.3. Wellbeing (block 5)

The literature treats accessibility and mobility differently as intermediaries towards personal and community wellbeing. Firstly, active mobility enables people to travel in a way that promotes their physical or mental health (Sherriff et al., Citation2020; Wang et al., Citation2021). Reversely, the absence of real opportunities to use alternative modes can have a detrimental effect on one’s wellbeing (Humberto et al., Citation2020; Ryan & Pereira, Citation2021; Ryan & Wretstrand, Citation2019; Shin, Citation2011). Secondly, accessibility and activity participation can satisfy one’s direct, hedonistic needs and desires (5a), or one’s sense of purpose and personal growth (eudemonia, 5b). Thirdly, mobility and accessibility influence society as a whole, where interconnections of individual levels of wellbeing synergistically result in community wellbeing (5c; Atkinson et al., Citation2017). The latter feeds back into a concept that CA scholars call “collective capabilities” (3c, only mentioned by Humberto et al., Citation2020; Ibrahim, Citation2006; Randal et al., Citation2020). Leßmann (Citation2020) identifies collective capabilities as being linked to groups of people, either defined internally (being a voluntary member of that group) or externally (being defined from certain attributes that individuals share). These groups are either sharing similar potential functionings, such as collective goods, or their collective agency can contribute to the collective capabilities of groups of people (Rosignoli, Citation2019). These indirectly influence resources and conversion factors around the individual (feedback loops II and III in ). In general, the literature on collective capabilities is ill defined. For transport planning, it is non-existent.

3.1.4. Integrating the CWB framework into a transport policy context

The actual use of the CA in transport policies has not been observed. Randal et al. (Citation2020), and less prominently Nahmias-Biran et al. (Citation2017) do explore policymaking aspects, but most scholars apply the CA in an academic research setting, which also happens in other domains (Mitchell et al., Citation2017). Reasons for this could be:

unfamiliarity with the CA among policymakers;

the generic and under-defined nature of the approach itself (Deka, Citation2022)

the complexity of integrated planning (Dryzek, Citation1987; Hickman et al., Citation2017; Meijers & Stead, Citation2004), partly explained by the focus of transport-related CA models on the individual, or;

reluctancy to make normative statements regarding policy objectives or basic rights (Pereira et al., Citation2017; Vecchio & Martens, Citation2021).

The process of transport policymaking (block 6) is connected to the CA framework in several ways. While a majority of studies primarily aim to inform policymakers to create or adjust their plans inductively, policymakers also need explicit and implicit theoretical frameworks to improve their deductive reasoning on how different interventions can be applied, and how, at least qualitatively, causal relations will eventually lead to planned and unplanned outcomes (Fischer & Maggetti, Citation2016; Hoogerwerf, Citation1990). In , the inductive arrows point upwards towards the transport planning process. The intervening, deductive arrows point downwards, from the planning process. Appendix 1 shows which studies are interpreted as being more inductive or deductive in nature.

3.2.1. Analysis, monitoring and evaluation, and goal setting (6a, 6b, 6c)

At the right-hand side of the framework, the measuring and assessment part of policymaking is depicted. Here, the outcomes of society using the transport and land use system, in terms of (community) wellbeing, should become visible. Societal outcomes (6a) can, however, only be partially explained by specific transport policy interventions (Arenghi et al., Citation2021; Cao & Hickman, Citation2019a; Larson et al., Citation2016; Luz & Portugal, Citation2021; Randal et al., Citation2020). Analogous to Egessa et al. (Citation2018), general levels of wellbeing fall beyond the “accountability ceiling” of transport policies. Nevertheless, transport policymakers do monitor and evaluate the “direct” state of the transport system, which is expressed in the capability sets and achieved functionings (6b). Because, if from a CWB perspective, health and safety are to be defined as outcomes, as “beings and doings”, they automatically also become transport policy objectives – which they often already are, although managed as different government disciplines, using isolated policies. Community-oriented safety, health, and sustainability objectives can conflict with individual-oriented accessibility objectives (Randal et al., Citation2020), requiring either trading off other CWB dimensions, or finding novel interventions that are co-beneficial for more dimensions (Vasconcellos Oliveira & Thorseth, Citation2016).

The literature is most elaborate on the assessment of accessibility-as-a-capability, including distributional issues. Most scholars agree on the contextual nature of what type of accessibility should be evaluated, often referring to Geurs and van Wee (Citation2004) and Handy (Citation2020). Based on the observed literature, transport policies are ideally concerned with providing a sufficient level of accessibility for all groups within society, as advocated by Martens (Citation2017, p. 131). This requires a process of democratic deliberation, compatible to Sen’s idea of process freedom (Basta, Citation2015; Robeyns, Citation2017, p. 76, 173). This implies that a scientific, objective determination of a good sufficiency threshold is a task for policymakers and the public, within their context (Hananel & Berechman, Citation2016), which will be further discussed in section 4.

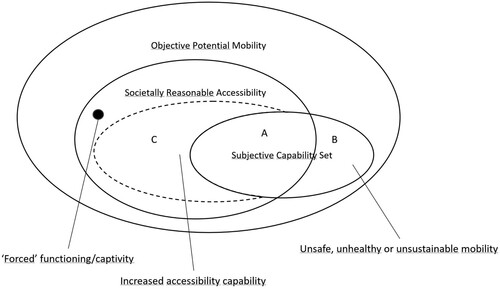

Goals are needed to direct the interventions that aim to promote “better” and “fairer” accessibility (6c). For this, the distinction between subjective accessibility-as-a-capability and objective potential mobility is now introduced (Kita et al., Citation2017; Ryan & Pereira, Citation2021; Vecchio, Citation2020). In , the total set of objective potential mobility capabilities is the largest, all-comprising set. This includes hypothetical options that are expensive, time-consuming, dangerous, or otherwise undesirable or prohibitive, either for the individual or for society. The subset of societally reasonable accessibility options consists of capabilities that society finds acceptable, which is a normative and contextual statement. For instance, most people in the Netherlands agree that an able-bodied student can be reasonably expected to cycle 3 km to university, even on an old and rusty bicycle, and that it is unreasonable for someone with respiratory problems to have to walk for 5 km to buy groceries in a supermarket. The individual, subjective capability set, then, is determined by one’s own resources and conversion factors, which is the current capability set (block 3 in ). The opportunities to travel for this individual can either be considered societally reasonable (A) or unreasonable (B). The (C) area represents the expansion of capabilities within the reasonable set, which is the objective of a CA-based transport policy. Reversely, some functionings are unreasonably burdensome for an individual, but they are nevertheless realised (Humberto et al., Citation2020). Such “forced” functionings give grounds to formulate a more precise definition of the term “captive” (Beimborn et al., Citation2003), basing it on a lack of agency rather than on observed behaviour only. In that sense, “forced car ownership” is a form of captivity, too (Curl et al., Citation2018).

As can be inferred from , there are many possibilities to express and measure accessibility inequalities that could inform policy objectives. Qualitative studies indicate causalities between circumstances and forms of exclusion due to transport poverty (Lennon et al., Citation2019; Shin, Citation2011; Vecchio, Citation2020). Quantitative studies based on survey data identified differences between potential mobility (capabilities) and the actual use of transport services (functionings) (Cao & Hickman, Citation2019a, Citation2019b, Citation2020; Hickman et al., Citation2017; Mella Lira, Citation2019), or described gaps between objectively determined accessibility and perceived accessibility (Humberto et al., Citation2020; Ryan & Pereira, Citation2021). Some studies use predictive models where the CA vocabulary is a basis to structure modelling parameters (Blečić et al., Citation2015; Nahmias-Biran & Shiftan, Citation2016). Empirical analyses utilise common inequality measures, such as the GINI coefficient and the Theil index, either for population groups (Bantis & Haworth, Citation2020; Boakye et al., Citation2022), or geographical areas, based on socio-spatial data (Blečić et al., Citation2020; Rashid & Yigitcanlar, Citation2015).

3.2.2. Policy delivery and execution (6d)

The choice of specific policy measures is closely tied to how policymakers want to achieve certain objectives. This is related to certain requirements in terms of financial means, legal constraints, and levels of acceptance on the one hand, compared to societal impact on the other. The framework should, at least qualitatively, be able to identify the mechanisms that lead to potential effects on the other CWB dimensions, including distributional consequences (Beyazit, Citation2011). Reciprocally, the multidimensionality also gives insight on how policies that aim for other societal goals, such as promoting climate neutral mobility (a part of the living environment dimension) can affect the accessibility of certain groups in society (Vasconcellos Oliveira & Thorseth, Citation2016).

Lennon et al. (Citation2019) see policy interventions as exogenous activities that alter the attributes of conversion factors. Generalising this notion of inductive reasoning, the work on disaster management is relevant (Boakye et al., Citation2022; Guidotti et al., Citation2016; Tabandeh et al., Citation2019). Not that all policy interventions have disastrous consequences, but, using a ToC lens on the CA (Egessa et al., Citation2018), policy interventions only affect resources and conversion factors. The effects (both ex post as ex ante) can be then assessed from a CA perspective, e.g. by projected changes in potential accessibility, achieved functionings or (community) wellbeing levels, including the probable distributional effects.

3.2.3. Feedback loops: experiences and externalities

The framework contains three feedback loops. Loop I has already been explained as the influence that achieved functionings can have on one’s personal wellbeing, in turn changing one’s personal conversion factors, either positively (practice, health gains), or negatively (bad experiences, becoming injured). Loops II and III are about the direct external effects of mobility behaviour, leading to different forms of exposure, such as bad air quality, noise, or increased unsafety. Within the field of transport, the CA has not been used much to systematically discuss externalities in a reciprocal way, which will be necessary to link the CA to all aspects of CWB. For this, the idea of “collective capabilities” is a potential chance, however that term should then be well defined (Robeyns, Citation2017), e.g. distinguishing between individual accessibility capabilities that are available through the collective, such as help from a neighbour, and more structural efforts from within society to strive for fairer and more sustainable accessibility capabilities (Schwanen & Nixon, Citation2020). Policies to promote sustainable modes and mobility patterns are also scarcely addressed. Randal et al. (Citation2020); and Vasconcellos Oliveira and Thorseth (Citation2016) acknowledge that policies are sometimes spearheading sustainability objectives over accessibility, and that these, including their distributional effects, should be included in transport policy analyses. Advancements in CA applications within the field of environmental studies did this already. White (Citation2020, p. 50) discusses a “capability ceiling” (see also Holland, Citation2008; Robeyns, Citation2019), ultimately following Peeters et al. (Citation2015):

… that the “ceiling” should be applied to functionings, rather than capabilities, in that: “it is not merely having the ability to pollute (i.e. the capability) … but the polluting itself (i.e. the functioning) that would have harmful effects” (p. 380, emphasis in original). This is consistent with Deneulin’s (Citation2002) acknowledgement that it might be more important, at particular times, “to focus on the human good (functionings), rather than on the freedom and opportunities to realise that human good (capabilities)” (p. 506).

4. Thresholds for sufficient accessibility

Low accessibility, or lacking accessibility freedom, is prohibitive in terms of achieving reasonable levels of wellbeing. Specifically, CWB policies are concerned with distributive issues. This implies that transport policy interventions solve, or mitigate, insufficient accessibility, as well as insufficiencies on the other dimensions that are related to the transport system. As Nielsen and Axelsen (Citation2016) argue for the CA generically, this can be achieved through a sufficientarianist approach. In that case, transport policies are “better” when more people experience sufficient accessibility, rather than some people with sufficient accessibility gaining more (Geurs, Citation2018; Luz & Portugal, Citation2021; Nahmias-Biran & Shiftan, Citation2019; Pereira et al., Citation2017; van Wee & Geurs, Citation2011; Vecchio & Martens, Citation2021). A transport policy intervention should thus be assessed in terms of “reduced insufficiency”. However, sufficiency thresholds for accessibility are ill-defined, and subject to public deliberation (Martens, Citation2017; Vecchio & Martens, Citation2021). Usually, this implies public participation (surveys, stakeholder meetings, etc.). However, as Sen (Citation2009) states, a transparent debate among informed professionals can also inform such thresholds. If principles of good governance hold, public servants could be the impartial observers (Drydyk, Citation2021; Sen, Citation2009): imaginary judges of what is “sufficient” for an individual (Stracke, Citation2016; Timmer, Citation2021; Volacu, Citation2017). As Stracke states, sufficientarian thresholds should at least be (1) unambiguous and non-arbitrary, (2) not over- or under demanding, and (3) multidimensional. A relative threshold is determined by comparing the accessibility levels of groups within society. Public servants, being impartial spectators, can also include insights regarding current levels of accessibility, legal commitments, professional guidelines, and the public means available. Policymakers could even use multiple thresholds, which can inform them on relative priorities to address problems (as proposed by Martens, Citation2017).

Drydyk (Citation2021) states that a fundamental capability, such as being healthy, is the ultimate end – not a derivative like the capability to access basic health care. Such an indicator is related to living a healthy life that complies to reasonable expectations of self-respecting people: a group that could be called representative for a societally accepted long and healthy life is then compared to other groups. For transport planning, distinct types of capability sets () could be constructed along the same line of “reasonable expectations”, also taking positive and negative collective capabilities into account. Since it is the domain of public policy, one could also argue that a first inventory can be made by people who assume the position of impartial observer, subject to professional and political norms of transparency, such as government professionals. They could describe combinations of potential activities and distances, or (mode-dependent) travel times, deemed reasonable, to inform political debates.

5. Conclusions

This paper sought to link CWB to transport policy evaluation through the CA by constructing a framework that is founded in existing research. The consequences of this approach for the process of setting sufficiency thresholds were discussed, leading to the following conclusions.

5.1. Using the CA to connect CWB to transport policies

The CA is well equipped to account for CWB policies, including transport policies, due to its multidimensional nature. Still, such applications have not been observed in actual governmental transport policy documents. By focusing on the purpose of policy evaluation, most discrepancies in the extant academic literature CA and transport can be resolved. For this, additional approaches have to be combined with the CA, such as the ToC and typologies of policy measures. These help distinguish between the domain where policy measures are applied (resources and conversion factors), the domain where policy goals are formulated (capabilities), and the domain where effects and outcomes are measured (functionings and wellbeing).

5.2. Using existing studies to construct a CWB framework

The existing literature provided enough rigorous underpinnings to create a consistent evaluative framework. Individual capabilities are ideally formulated in terms of potential accessibility, including its distribution among groups and geographical areas. Additional concepts, such as the affordances theory, the TPB, and notions of option value can be used to further operationalise elements, depending on the specific policy context. More work is needed on collective capabilities, however, in order to be compatible with the granularity and level of abstraction that (strategic) transport plans work with. Using combinations of collective capabilities, the capabilities of others, and the notion of “commons” for the dimensions of CWB, trade-offs and potential co-benefits of prospective government interventions can be more systematically reasoned about by transport planning professionals using this framework.

5.3. Thresholds for sufficient accessibility

The CA implies that transport policies are not specifically aimed at maximal utility, but at enhancing the capabilities of people to live a good life, thus contributing to a thriving community. This implicitly selects sufficientarianism as the preferred theory of distributive justice for the accessibility dimension. Based on applications of the CA in other disciplines, a method to establish accessibility thresholds, even accounting for sustainability, health, and safety could be derived, but this has not been researched yet for the transport domain. Scientifically speaking, it is undesirable to objectively determine what sufficient accessibility is. We conclude that policymakers should be responsible for setting the thresholds, preferably following a public deliberation process. Depending on the issue at hand, this can be done by having structured discussions with stakeholders (Vecchio, Citation2020), up to more quantitatively underpinned methods as a public value evaluation (Mouter et al., Citation2019). Thresholds, and the processes to set them, remain one of the urgent knowledge gaps to improve CWB in municipal transport policy making (Ryan & Martens, Citation2023). That said, further understanding of the mechanisms that lead to “unreasonable functionings” is essential to choose appropriate policy measures that limit one’s capabilities to travel in certain ways, or expand the capabilities of “captives” to have access to meaningful activities in safer, healthier, and more sustainable ways. This expansion can be both an “objective” expansion, or an expansion of one’s “subjective” capability set (Kita et al., Citation2017) in case there is a mismatch.

5.4. Further research

The framework has not yet been applied in real policymaking activities, which would be a logical next step, leading to further improvements. The question whether this framework leads to less classical and predictable policy discourses deserves specific interest (Lennon et al., Citation2019). Also, a further exploration into quantitative (model) operationalisations could improve ongoing efforts to conduct non-utilitarian, heterodox accessibility analyses, including the use of CWB indicators. These, in turn, can guide efforts to gather social and spatial data, accounting for CWB in transport policy.

Further research is needed into the process of threshold setting as a collective capability within government institutions. Using the notion of “impartial observers”, information should be gathered about what transport planning professionals consider sufficient accessibility, as well as excessive mobility, for different types of activities, contexts, regions, and population groups, and how they come to their conclusions. These insights can be related to e.g. their task of allocating government budgets to certain activities, their knowledge of the transport system, and their implicit and explicit ToCs.

One potential example is the extent to which government involvement in shared mobility schemes actually progresses CWB in neighbourhoods. By systematically going over resources and conversion factors involved in shared mobility policies, policymakers can qualitatively test the extent to which it actually increases the capability set of groups with insufficient accessibility (rather than looking at ridership). This might lead to additional efforts on e.g. the pricing for low-income groups (resources), planning round trips with shared bikes for specific cultural groups (social conversion factors), or providing assistance with the digital reservation systems for digitally illiterate people (personal conversion factors).

Appendix.docx

Download MS Word (48.2 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Some consider the built environment as a resource, implying free choices of residence, job, or school location. These are not always perceived as free, especially for low-income groups (Hemerijck, Citation2020; Laurent, Citation2014), but even in free location choice situations, accessibility issues can be underestimated by individuals (Bijker et al., Citation2015; Levy et al., Citation2008).

References

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

- Akhavan, M., & Vecchio, G. (2018). Mobility and accessibility of the ageing society. Defining profiles of the elderly population and neighbourhood. TeMA-Journal of Land Use, Mobility and Environment, (Special issue 2.2018), 9–22.

- Akse, R., Albert de la Bruhèze, A., & Geurs, K. (2023). Transport planning, paradigms and practices: Finding conditions for change. In R. Hickman & C. Hannigan (Eds.), Discourse analysis in transport and urban development (pp. 11–23). Edward Elgarr Publishing Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781802207200

- Akse, R., Thomas, T., & Geurs, K. (2021). Mobility and accessibility paradigms in Dutch policies: An empirical analysis. Journal of Transport and Land Use, 14(1), 1317–1340. https://doi.org/10.5198/jtlu.2021.2097

- Alidoust, S., Gleeson, N., & Khalaj, F. (2022). A systematic review of planning policies for community wellbeing. Journal of Urbanism: International Research on Placemaking and Urban Sustainability, Advance online publication, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/17549175.2022.2071971

- Alkire, S. (2008). Using the capability approach: Prospective and evaluative analyses (The capability approach: Concepts, measures and applications) (pp. 26–50). Cambridge University Press.

- Alkire, S. (2016). The capability approach and well-being measurement for public policy. In M. D. Adler & M. Fleurbaey (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of well-being and public policy (pp. 615–644). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199325818.013.18

- Arenghi, A., Camodeca, R., & Almici, A. (2021). Accessibility and universal design: Do they provide economic benefits? (Universal design 2021: From special to mainstream solutions) (pp. 3–12). IOS Press.

- Atkinson, S., Bagnall, A., Corcoran, R., & South, J. (2017). What is community wellbeing? Conceptual review. W. W. C. f. Wellbeing. https://eprints.leedsbeckett.ac.uk/id/eprint/5237/

- Azmoodeh, M., Haghighi, F., & Motieyan, H. (2022). Capability index: Applying a fuzzy-based decision-making method to evaluate social inclusion in urban areas using the capability approach. Social Indicators Research, 165(1), 77–105. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-022-03005-5

- Babb, C., Olaru, D., Curtis, C., & Robertson, D. (2017). Children’s active travel, local activity spaces and wellbeing: A case study in Perth, WA. Travel Behaviour and Society, 9, 81–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tbs.2017.06.002

- Bantis, T., & Haworth, J. (2020). Assessing transport related social exclusion using a capabilities approach to accessibility framework: A dynamic Bayesian network approach. Journal of Transport Geography, 84(102673), 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2020.102673

- Basta, C. (2015). From justice in planning toward planning for justice: A capability approach. Planning Theory, 15(2), 190–212. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473095215571399

- Beimborn, E. A., Greenwald, M. J., & Jin, X. (2003). Accessibility, connectivity, and captivity: Impacts on transit choice. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board, 1835(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.3141/1835-01

- Beyazit, E. (2011). Evaluating social justice in transport: Lessons to be learned from the capability approach. Transport Reviews, 31(1), 117–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/01441647.2010.504900

- Biagi, B., Ladu, M. G., & Meleddu, M. (2018). Urban quality of life and capabilities: An experimental study. Ecological Economics, 150, 137–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2018.04.011

- Bijker, R. A., Haartsen, T., & Strijker, D. (2015). How people move to rural areas: Insights in the residential search process from a diary approach. Journal of Rural Studies, 38, 77–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2015.01.002

- Blečić, I., Cecchini, A., Congiu, T., Fancello, G., Talu, V., & Trunfio, G. A. (2020). Capability-wise walkability evaluation as an indicator of urban peripherality. Environment and Planning B: Urban Analytics and City Science, 48(4), 895–911. https://doi.org/10.1177/2399808320908294

- Blečić, I., Cecchini, A., Congiu, T., Fancello, G., & Trunfio, G. A. (2015). Evaluating walkability: A capability-wise planning and design support system. International Journal of Geographical Information Science, 29(8), 1350–1374. https://doi.org/10.1080/13658816.2015.1026824

- Boakye, J., Guidotti, R., Gardoni, P., & Murphy, C. (2022). The role of transportation infrastructure on the impact of natural hazards on communities. Reliability Engineering & System Safety, 219, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ress.2021.108184

- Cao, M., & Hickman, R. (2019a). Understanding travel and differential capabilities and functionings in Beijing. Transport Policy, 83, 46–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2019.08.006

- Cao, M., & Hickman, R. (2019b). Urban transport and social inequities in neighbourhoods near underground stations in reater London. Transportation Planning and Technology, 42(5), 419–441. https://doi.org/10.1080/03081060.2019.1609215

- Cao, M., & Hickman, R. (2020). Transport, social equity and capabilities in east Beijing (handbook on transport and urban transformation in China. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Carpenter, M. (2013). From ‘healthful exercise’ to ‘nature on prescription’: The politics of urban green spaces and walking for health. Landscape and Urban Planning, 118, 120–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2013.02.009

- Chen, N., & Akar, G. (2016). How do socio-demographics and built environment affect individual accessibility based on activity space? Evidence from greater Cleveland, Ohio. Journal of Transport and Land Use, 10(1), 477–503. https://doi.org/10.5198/jtlu.2016.861

- Clark, S. S., Peterson, S. K. E., Shelly, M. A., & Jeffers, R. F. (2022). Developing an equity-focused metric for quantifying the social burden of infrastructure disruptions. Sustainable and Resilient Infrastructure, 8(sup1), 356–369. https://doi.org/10.1080/23789689.2022.2157116

- Cloutier, S., Ehlenz, M. M., & Afinowich, R. (2019). Cultivating community wellbeing: Guiding principles for research and practice. International Journal of Community Well-Being, 2(3-4), 277–299. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42413-019-00033-x

- Cooke, S., Ryseck, B., Siame, G., Nkurunziza, A., Molefe, L., & Zuidgeest, M. (2022). Proximity is not access: A capabilities approach to understanding non-motorized transport vulnerability in African cities. Frontiers in Sustainable Cities, 4, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.3389/frsc.2022.811049

- CROW-KpVV. (2022). Brede Welvaart en Mobiliteit. CROW. Retrieved 29-12-2022 from https://www.crow.nl/thema-s/brede-welvaart

- Curl, A., Clark, J., & Kearns, A. (2018). Household car adoption and financial distress in deprived urban communities: A case of forced car ownership? Transport Policy, 65, 61–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2017.01.002

- Dagsvik, J. K. (2013). Making Sen’s capability approach operational: A random scale framework. Theory and Decision, 74(1), 75–105. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11238-012-9340-5

- Deka, D. (2022). Trip deprivation among older adults in the context of the capability approach. Journal of Transport Geography, 100, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2022.103325

- del Mar Parra López, M., Annema, J. A., & van Wee, B. (2022). The added value of having multiple options to travel to an explorative study. Journal of Transport Geography, 98, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2021.103258

- Deneulin, S. (2002). Perfectionism, paternalism and liberalism in Sen and Nussbaum's capability approach. Review of Political Economy, 14(4), 497–518. https://doi.org/10.1080/0953825022000009924

- Dillman, K. J., Czepkiewicz, M., Heinonen, J., & Davíðsdóttir, B. (2021). A safe and just space for urban mobility: A framework for sector-based sustainable consumption corridor development. Global Sustainability, 4(e28), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1017/sus.2021.28

- Drydyk, J. (2021). Healthy enough? A capability approach to sufficiency and equality. Canadian Journal of Practical Philosophy, 5(1), 18–34.

- Dryzek, J. S. (1987). Complexity and rationality in public life. Political Studies, 35(3), 424–442. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.1987.tb00198.x

- Durand, A., & Zijlstra, T. (2020). The impact of digitalisation on the access to transport services: a literature review (https://www.kimnet.nl/publicaties/rapporten/2020/06/29/de-impact-van-digitalisering-op-de-toegang-tot-vervoersdiensten-een-literatuurreview

- Egessa, M., Liyala, S., & Ogara, S.. (2018). What theory of change can contribute to capability approach. 2018 IST-Africa Week Conference, Gaborone, Botswana, 9-11 may 2018.

- Fischer, M., & Maggetti, M. (2016). Qualitative comparative analysis and the study of policy processes. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice, 19(4), 345–361. https://doi.org/10.1080/13876988.2016.1149281

- Friman, M., Ettema, D., & Olsson, L. E. (2018). Quality of life and daily travel. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-76623-2

- Gasper, D. (2007). What is the capability approach? Its core, rationale, partners and dangers (development ethics) (pp. 217–241). Routledge.

- Geurs, K. T. (2018). Transport planning with accessibility indices in the Netherlands, International Transport Forum Discussion Paper, No. 2018-09. International Transport Forum, Paris.

- Geurs, K. T., Haaijer, R., & Van Wee, B. (2007). Option value of public transport: Methodology for measurement and case study for regional rail links in The Netherlands. Transport Reviews, 26(5), 613–643. https://doi.org/10.1080/01441640600655763

- Geurs, K. T., & van Wee, B. (2004). Accessibility evaluation of land-use and transport strategies: Review and research directions. Journal of Transport Geography, 12(2), 127–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2003.10.005

- Geurs, K. T., Zondag, B., de Jong, G., & de Bok, M. (2010). Accessibility appraisal of land-use/transport policy strategies: More than just adding up travel-time savings. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment, 15(7), 382–393. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trd.2010.04.006

- Gibson, J. J. (2014). The theory of affordances (The ecological approach to visual perception) (Vol. 1, pp. 67–82). Psychology Press. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315740218

- Givoni, M. (2014). Addressing transport policy challenges through policy-packaging. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 60, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2013.10.012

- Goodman, A., Jones, A., Roberts, H., Steinbach, R., & Green, J. (2014). We can all just get on a bus and go’: Rethinking independent mobility in the context of the universal provision of free bus travel to young londoners. Mobilities, 9(2), 275–293. https://doi.org/10.1080/17450101.2013.782848

- Guidotti, R., Chmielewski, H., Unnikrishnan, V., Gardoni, P., McAllister, T., & van de Lindt, J. (2016). Modeling the resilience of critical infrastructure: The role of network dependencies. Sustainable Resilient Infrastructure, 1(3-4), 153–168. https://doi.org/10.1080/23789689.2016.1254999

- Haddaway, N. R., Page, M. J., Pritchard, C. C., & McGuinness, L. A. (2022). PRISMA2020: An R package and Shiny app for producing PRISMA 2020-compliant flow diagrams, with interactivity for optimised digital transparency and open synthesis. Campbell Systematic Reviews, 18(2), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1002/cl2.1230

- Hägerstrand, T. (1970). What about people in regional science? Papers of the Regional Science Association, 24(1), 6–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01936872

- Hananel, R., & Berechman, J. (2016). Justice and transportation decision-making: The capabilities approach. Transport Policy, 49, 78–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2016.04.005

- Handy, S. (2020). Is accessibility an idea whose time has finally come? Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment, 83, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trd.2020.102319

- Hansen, W. G. (1959). How accessibility shapes land use. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 25(2), 73–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944365908978307

- Hemerijck, A. (2020). Correlates of capacitating solidarity. Housing, Theory and Society, 37(3), 278–288. https://doi.org/10.1080/14036096.2019.1705386

- Hickman, R., Cao, M., Lira, M., Fillone, B., Biona, A., & B, J. (2017). Understanding capabilities, functionings and travel in high and low income neighbourhoods in Manila. Social Inclusion, 5(4), 161–174. https://doi.org/10.17645/si.v5i4.1083

- Holland, B. (2008). Ecology and the limits of justice: Establishing capability ceilings in Nussbaum's capabilities approach. Journal of Human Development, 9(3), 401–425. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649880802236631

- Hoogerwerf, A. (1990). Reconstructing policy theory. Evaluation and Program Planning, 13(3), 285–291. https://doi.org/10.1016/0149-7189(90)90059-6

- Humberto, M., Pizzol, B., Moura, F., Giannotti, M., & de Lucca-Silveira, M. P. (2020). Investigating the mobility capabilities and functionings in accessing schools through walking: A quantitative assessment of public and private schools in São Paulo (Brazil). Journal of Human Development and Capabilities, 21(2), 183–204. https://doi.org/10.1080/19452829.2020.1745163

- Ibrahim, S. S. (2006). From individual to collective capabilities: The capability approach as a conceptual framework for self-help. Journal of Human Development, 7(3), 397–416. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649880600815982

- Inoi, H., & Nitta, Y.. (2005). The planning of the community transport from the viewpoint of well-being: Applying Amartya Sen’s capability approach. Proceedings of the Eastern Asia Society for Transportation Studies, Vol. 5, Bangkok, Thailand, 21-24 September, 2005.

- Jónasdóttir, S. K., Egilson, S.Þ., & Polgar, J. (2021). Structural factors affecting community mobility for people with mobility impairments in Iceland: A human rights and occupational perspective. Journal of Occupational Science, 28(1), 59–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2021.1896570

- Kita, H., Yotsutsuji, H., Ikemiya, M., & Suga, Y. (2017). How to measure the level of activity opportunities secured by rural public transport service: The capability approach. Transportation Research Procedia, 25, 3865–3874. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trpro.2017.05.296

- Kuklys, W. (2005). Amartya Sen's capability approach: Theoretical insights and empirical applications. Springer.

- Larson, L. R., Jennings, V., & Cloutier, S. A. (2016). Public parks and wellbeing in urban areas of the United States. PLoS One, 11(4), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0153211

- Laurent, É. (2014). Environmental inequality in France: A theoretical. Empirical and Policy Perspective, 36(2), 251–262. https://doi.org/10.1515/auk-2014-0204

- Lennon, M., Douglas, O., & Scott, M. (2019). Responsive environments: An outline of a method for determining context sensitive planning interventions to enhance health and wellbeing. Land Use Policy, 80, 68–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2018.09.037

- Leßmann, O. (2020). Collectivity and the capability approach: Survey and discussion. Review of Social Economy, 80(4), 461–490. https://doi.org/10.1080/00346764.2020.1774636

- Leßmann, O., & Masson, T. (2015). Sustainable consumption in capability perspective: Operationalization and empirical illustration. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics, 57, 64–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socec.2015.04.001

- Levy, D., Murphy, L., & Lee, C. K. C. (2008). Influences and emotions: Exploring family decision-making processes when buying a house. Housing Studies, 23(2), 271–289. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673030801893164

- Lewis, F. (2011). Toward a general model of built environment audits. Planning Theory, 11(1), 44–65. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473095211408056

- Lucas, K., Martens, K., Di Ciommo, F., & Dupont-Kieffer, A. (2019). Measuring transport equity. Elsevier.

- Luz, G., & Portugal, L. (2021). Understanding transport-related social exclusion through the lens of capabilities approach. Transport Reviews, 42(4), 503–525. https://doi.org/10.1080/01441647.2021.2005183

- Marks, D. H. (2002). The evolving role of systems analysis in process and methods in large-scale public socio-technical systems.

- Martens, K. (2017). Transport justice: Designing fair transportation systems. Routledge.

- Meijers, E., & Stead, D. (2004). Policy integration: What does it mean and how can it be achieved? A multi-disciplinary review. Berlin Conference on the Human Dimensions of Global Environmental Change: Greening of Policies-Interlinkages and Policy Integration.

- Mella Lira, B. (2019). Using a capability approach-based survey for reducing equity gaps in transport appraisal: Application in Santiago de Chile (measuring transport equity) (pp. 247–264). Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-814818-1.00016-0

- Ministerie van Infrastructuur en Waterstaat. (2023). Mobiliteitsvisie 2050 Hoofdlijnennotitie, https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/documenten/rapporten/2023/03/17/bijlage-hoofdlijnennotitie-mobiliteitsvisie-2050

- Mitchell, P. M., Roberts, T. E., Barton, P. M., & Coast, J. (2017). Applications of the capability approach in the health field: A literature review. Social Indicators Research, 133(1), 345–371. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-016-1356-8

- Mitra, S. (2006). The capability approach and disability. Journal of Disability Policy Studies, 16(4), 236–247. https://doi.org/10.1177/10442073060160040501

- Mouter, N., Koster, P., & Dekker, T. (2019). An introduction to participatory value evaluation.

- Nahmias-Biran, B.-h., Martens, K., & Shiftan, Y. (2017). Integrating equity in transportation project assessment: A philosophical exploration and its practical implications. Transport Reviews, 37(2), 192–210. https://doi.org/10.1080/01441647.2017.1276604

- Nahmias-Biran, B.-h., & Shiftan, Y. (2016). Towards a more equitable distribution of resources: Using activity-based models and subjective well-being measures in transport project evaluation. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 94, 672–684. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2016.10.010

- Nahmias-Biran, B.-h., & Shiftan, Y. (2019). Using activity-based models and the capability approach to evaluate equity considerations in transportation projects. Transportation, 47(5), 2287–2305. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11116-019-10015-9

- New Zealand Government. (2020). Government Policy Statement on Land Transport. https://www.transport.govt.nz/consultations/government-policy-statement-on-land-transport-2021/

- Nielsen, L., & Axelsen, D. V. (2016). Capabilitarian sufficiency: Capabilities and social justice. Journal of Human Development and Capabilities, 18(1), 46–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/19452829.2016.1145632

- Norwegian Ministry of Transport. (2021). National Transport Plan 2022-2033: Report to the Sorting (whit paper) English Summary. https://www.regjeringen.no/en/dokumenter/national-transport-plan-2022-2033/id2863430/?ch=6

- Nussbaum, M. C. (2000). Women and human development: The capabilities approach (Vol. 3). Cambridge University Press.

- Patterson, Z., & Farber, S. (2015). Potential path areas and activity spaces in application: A review. Transport Reviews, 35(6), 679–700. https://doi.org/10.1080/01441647.2015.1042944

- Peeters, W., Dirix, J., & Sterckx, S. (2015). The capabilities approach and environmental sustainability: The case for functioning constraints. Environmental Values, 24(3), 367–389. https://doi.org/10.3197/096327115(14273714154575)

- Pereira, R. H. M., Schwanen, T., & Banister, D. (2017). Distributive justice and equity in transportation. Transport Reviews, 37(2), 170–191. https://doi.org/10.1080/01441647.2016.1257660

- PRISMA. (2020). PRISMA Statement. Retrieved 29-1-2023 from http://prisma-statement.org/

- Radomskaya, V., & Bhati, A. S. (2022). Hawker centres: A social space approach to promoting community wellbeing. Urban Planning, 7(4), 167–178. https://doi.org/10.17645/up.v7i4.5658

- Randal, E., Shaw, C., Woodward, A., Howden-Chapman, P., Macmillan, A., Hosking, J., … Keall, M. (2020). Fairness in transport policy: A new approach to applying distributive justice theories. Sustainability, 12(23), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122310102

- Rashid, K., & Yigitcanlar, T. (2015). A methodological exploration to determine transportation disadvantage variables: The partial least square approach. 5.

- Raworth, K. (2017). Doughnut economics: Seven ways to think like a 21st-century economist. Chelsea Green Publishing.

- Robeyns, I. (2005). The capability approach: A theoretical survey. Journal of Human Development, 6(1), 93–117. https://doi.org/10.1080/146498805200034266

- Robeyns, I. (2017). Wellbeing, freedom and social justice: The capability approach re-examined. Open Book Publishers.

- Robeyns, I. (2019). What, if anything, is wrong with extreme wealth? Journal of Human Development and Capabilities, 20(3), 251–266. https://doi.org/10.1080/19452829.2019.1633734

- Rosignoli, F. (2019). Categorizing collective capabilities. Partecipazione e conflitto. http://siba-ese.unisalento.it/index.php/paco/article/view/20229/17197

- Ryan, J., & Martens, K. (2023). Defining and implementing a sufficient level of accessibility: What’s stopping us? Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 175, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2023.103792

- Ryan, J., & Pereira, R. H. M. (2021). What are we missing when we measure accessibility? Comparing calculated and self-reported accounts among older people. Journal of Transport Geography, 93, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2021.103086

- Ryan, J., & Wretstrand, A. (2019). What’s mode got to do with it? Exploring the links between public transport and car access and opportunities for everyday activities among older people. Travel Behaviour and Society, 14, 107–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tbs.2018.10.003

- Ryan, J., Wretstrand, A., & Schmidt, S. M. (2019). Disparities in mobility among older people: Findings from a capability-based travel survey. Transport Policy, 79, 177–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2019.04.016

- Schramme, T. (2016). The metric and the threshold problem for theories of health justice: A comment on venkatapuram. Bioethics, 30(1), 19–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/bioe.12218

- Schwanen, T., & Nixon, D. V. (2020). Understanding the relationships between wellbeing and mobility in the unequal city: The case of community initiatives promoting cycling and walking in São Paulo and London (Urban transformations and public health in the emergent city). Manchester University Press.

- Scottish Government. (2022). National Transport Strategy - Second Delivery Plan 2022 2023. https://www.transport.gov.scot/publication/national-transport-strategy-nts2-second-delivery-plan-2022-2023/

- Sen, A. (1979). The Tanner Lectures on Human Values (Vol. 1, pp. 353–369). Salt Lake City, USA: University of Utah Press.

- Sen, A. (1985). Commodities and capabilities. North-Holland.

- Sen, A. (2009). The idea of justice. Harvard University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvjnrv7n

- Setti, M., & Garuti, M. (2018). Identity, commons and sustainability: An economic perspective. Sustainability, 10(2), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10020409

- Shen, Q. (1998). Location characteristics of inner-city neighborhoods and employment accessibility of low-wage workers. Environment and Planning B: Urban Analytics and City Science, 25(3), 345–365. https://doi.org/10.1068/b250345

- Sherriff, G., Adams, M., Blazejewski, L., Davies, N., & Kamerāde, D. (2020). From mobike to no bike in greater Manchester: Using the capabilities approach to explore Europe's first wave of dockless bike share. Journal of Transport Geography, 86, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2020.102744

- Shin, H. (2011). Spatial capability for understanding gendered mobility for Korean Christian immigrant women in Los Angeles. Urban Studies, 48(11), 2355–2373. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098010388955

- Smith, Noel, Hirsch, Donald, & Davis, Abigail. (2012). Accessibility and capability: the minimum transport needs and costs of rural households. Journal of Transport Geography, 21, 93–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2012.01.004

- Snellen, D., ‘t Hoen, M., & Bastiaanssen, J. (2021). Brede welvaart en mobiliteit. Planbureau voor de Leefomgeving. https://www.pbl.nl/publicaties/brede-welvaart-en-mobiliteit

- Soukhov, A., Paez, A., Higgins, C. D., & Mohamed, M. (2023). Introducing spatial availability, a singly-constrained measure of competitive accessibility. PLoS One, 18(1), 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0278468

- Stracke, E. (2016). Thresholds in sufficientarianism, BA thesis. Universität Bayreuth.

- Sunio, V., Fillone, A., Abad, R. P., Rivera, J., & Guillen, M. D. (2023). Why does demand-based transport planning persist? Insights from social practice theory. Journal of Transport Geography, 111, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2023.103666

- Tabandeh, A., Gardoni, P., Murphy, C., & Myers, N. J. A. J. R. U. A. (2019). Societal risk and resilience analysis: Dynamic Bayesian network formulation of a capability approach. ASCE-ASME Journal of Risk and Uncertainty in Engineering Systems, Part A: Civil Engineering, 5(1), Article 04018046. https://doi.org/10.1061/AJRUA6.0000996

- Timmer, D. (2021). Thresholds in distributive justice. Utilitas, 33(4), 422–441. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0953820821000194

- Trani, J.-F., Bakhshi, P., Bellanca, N., Biggeri, M., & Marchetta, F. (2011). Disabilities through the capability approach lens: Implications for public policies. Alter, 5(3), 143–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.alter.2011.04.001

- Trendbureau Drenthe. (2021). Monitor Brede Welvaart Drente 2021, https://trendbureaudrenthe.nl/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/TD_MonitorBredeWelvaartDrenthe2021-def.pdf

- Vallee, J., Shareck, M., Le Roux, G., Kestens, Y., & Frohlich, K. L. (2020). Is accessibility in the eye of the beholder? Social inequalities in spatial accessibility to health-related resources in Montreal, Canada. Social Science & Medicine, 245, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112702

- van der Doelen, F. C. J., & Klok, P. J. (1989). Beleidsinstrumenten. In A. Hoogerwerf (Ed.), Overheidsbeleid (pp. 73–90). Samsom H.D. Tjeenk Willink (Original work published 1978).

- van Wee, B. (2011). Transport and ethics: Ethics and the evaluation of transport policies and projects. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- van Wee, B. (2019). Land use policy, travel behavior, and health. In M. Nieuwenhuijsen & H. Khreis (Eds.), Integrating human health into urban and transport planning: A framework (pp. 253–269). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-74983-9_13

- Van Wee, B. (2023). The transport system and its effects on accessibility, the environment, safety, health and well-being: An introduction. In B. V. Wee, J. A. Annema, D. Banister, & B. Pudāne (Eds.), The transport system and transport policy: An introduction (2nd ed., pp. 3–16). Edward Elgar Publishing, Inc.

- van Wee, B., & Geurs, K. T. (2011). Discussing equity and social exclusion in accessibility evaluations. European Journal of Transport and Infrastructure Research, 11(4), 350–367.

- Vasconcellos Oliveira, R., & Thorseth, M. (2016). Ethical implications of co-benefits rationale within climate change mitigation strategy. Etikk i Praksis – Nordic Journal of Applied Ethics, (2), 141–170. https://doi.org/10.5324/eip.v10i2.1942

- Vecchio, G. (2020). Microstories of everyday mobilities and opportunities in Bogotá: A tool for bringing capabilities into urban mobility planning. Journal of Transport Geography, 83, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2020.102652

- Vecchio, G., & Martens, K. (2021). Accessibility and the capabilities approach: A review of the literature and proposal for conceptual advancements. Transport Reviews, 41(6), 833–854. https://doi.org/10.1080/01441647.2021.1931551

- Vedung, E. (1998). Policy instruments: Typologies and theories. In M.-L. Bemelmans-Videc, R. C. Rist, & E. Verdung (Eds.), Carrots, sticks, and sermons: Policy instruments and their evaluation (pp. 21–58). Transaction Publishers.

- Venkatapuram, S. (2013). Health justice: An argument from the capabilities approach. John Wiley & Sons.

- Volacu, A. (2017). Maximization, slotean satisficing, and theories of sufficientarian justice. Croatian Journal of Philosophy, 17(49), 73–90.

- Wang, J., Lindsey, G., & Fan, Y. (2021). Exploring the interactions between modal options, destination access, and travel mood. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour, 82, 450–461. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trf.2021.09.012

- White, R. G. (2020). Mental wellbeing in the Anthropocene: Socio-ecological approaches to capability enhancement. Transcultural Psychiatry, 57(1), 44–56. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363461518786559

- Willberg, E., Tenkanen, H., Miller, H. J., Pereira, R. H. M., & Toivonen, T. (2023). Measuring just accessibility within planetary boundaries. Transport Reviews, 44(1), 140–166. https://doi.org/10.1080/01441647.2023.2240958

- Wiseman, J., & Brasher, K. (2008). Community wellbeing in an unwell world: Trends, challenges, and possibilities. Journal of Public Health Policy, 29(3), 353–366. https://doi.org/10.1057/jphp.2008.16