Abstract

Recent years have seen a proliferation of composite indicators or indexes of governance and their use in research and policy-making. This article proposes a framework of 10 questions to guide both the development and evaluation of such indexes. In reviewing these 10 questions – only six of which, it argues, are critical – the paper advances two broad arguments: First, more attention should be paid to the fundamentals of social science methodology, that is, concept formation, content validity, reliability, replicability, robustness, and the relevance of particular measures to underlying research questions. Second, less attention should be paid to other issues more commonly highlighted in the literature on governance measurement, that is, descriptive complexity, theoretical fit, the precision of estimates, and ‘correct’ weighting. The paper builds on review of the literature and on three years of research in practice in developing a well-known governance index.

Inroduction

Recent years have seen a proliferation of measures of governance and their use in both research and policy-making. Some of the best known include the World Bank's Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI) and Country Policy and Institutional Assessment (CPIA), Transparency International's Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI), and Freedom House's Freedom in the World. We might also add to this list measures designed to capture related topics, such the UNDP's Human Development Index (HDI) and the Legatum Prosperity Index.

Many of these measures combine, in some way, several metrics to get a single score, grade, or rating. Such ‘composite indicators’ or ‘indexes’ thus capture multiple facts or dimensions of a complex, multidimensional concept in a way that facilitates evaluation and comparison. Such measures can be useful tools for analyzing governance, assessing development priorities, building scientific knowledge, and even influencing ruling elites, but some are better tools than others and some are better suited to certain purposes than others. This paper proposes a framework of 10 questions for practitioners and scholars to consider in the process either of developing new indexes or evaluating existing indexes, offering examples from a handful of the best known measures of governance and related topics.

In reviewing these 10 questions – only the first six of which, it argues, are critical – the discussion advances two broad arguments: First, more attention should be paid in governance measurement to the fundamentals of social science methodology, that is, concept formation, content validity, reliability, replicability, robustness, and the relevance of particular measures to underlying research questions. Second, some other issues that have received more attention in work on governance measurement – that is, descriptive complexity, theoretical fit, the precision of estimates, and correct weighting – should also be considered, but are less critical.

The framework draws both on review of the research literature and on three years of research in practice, specifically the author's experience in developing a well-used measure of governance.Footnote1 As discussed further below, some of the points highlighted here are also discussed in other work and readers may wish to consult this literature for more extensive discussion (see, e.g., Van de Walle Citation2006; Arndt and Oman Citation2006; Thomas Citation2009; Andrews Citation2008; Bersch and Botero Citation2014). This piece adds to the existing literature, first, by proposing a more comprehensive framework, encompassing a broader set of considerations than most of the other work (which tends to focus on only a subset of the issues highlighted here, such as content validity but not data quality). It also challenges the focus in broader literature on the final four questions over the first six.

What this paper does not do is to provide a single, multipurpose rubric for the ‘best’ governance index. Indeed, it suggests this to be a futile task. The 10 questions highlighted here can be used to show that some ways of constructing indexes are objectively weaker than others (e.g., because indicators completely lack validity, are not presented transparently, results are cherry picked), and a task for another paper would be to apply the framework to existing indexes in this way. However, more importantly, the discussion here implies that there can be many ‘good’ indexes because different tasks require different measures. Among generally good governance indexes of the sort discussed here, focusing on which is best in the abstract is like asking whether a hammer or a screwdriver is a better tool. Thus, the focus in this paper is on providing a framework to help users and producers of indexes, both practitioners and researchers, to systematically develop and/or evaluate the best tool(s) for their purposes. In particular, working through the questions in roughly sequential order can provide a guide for index development, while users and evaluators of indexes may wish to skip around more in using the questions to map key strengths and weaknesses of particular measures.

The paper focuses on composite indicators of governance, although the framework is broadly applicable to the evaluation of ‘single’ governance indicators as well. Of course, some points (in particular those on weighting and aggregation) will not be relevant. The framework may also be used to consider composite indicators on topics other than governance. However, the four questions identified as less critical for the evaluation of governance indexes may be more important in measurement of other complex concepts for which causal theories are more developed, underlying data stronger, and components easier to measure.

It is worth highlighting that one major critique of national-level governance indicators is that they are just not useful because they are too simple to give a full picture of governance and to guide governance reform within particular countries. Hyden, Court, and Mease (Citation2003, 4), for instance, dismiss such projects as ‘not very helpful … in getting a better understanding of what really happens to governance on the ground.’ Other critics highlight the inability of country-level indexes to capture the significant variations in governance at sub-national levels (e.g., Harttgen and Klasen Citation2012) and the related question of actionability and whether the diagnosis of governance deficiencies can provide policy-relevant insight into how to fix them (e.g., Williams Citation2011). Related literatures on governance suggest epistemological concerns about the quantitative measurement of governance and the value of more interpretative approaches (e.g., Bevir and Rhodes Citation2006).

This broad set of critiques is well worth considering, especially when thinking about whether limited resources are invested in an index versus another sort of governance assessment – a point briefly returned to in the conclusion. However, it can also be a bit of a straw man: governance indexes are not generally designed to provide a standalone guide to governance and governance reform within countries. Experts use indexes to facilitate cross-national comparisons and quantitative analysis, to explore trends over time, and to identify relationships for further study using other sources of information. For experts focused on particular countries, indexes complement – not substitute for – other types of assessments. They can further be useful tools for engagement with nonexpert audiences who lack the time or interest to engage more broadly. Thus, this paper does not focus on whether indexes should be used at all, but rather on how they can best be developed and evaluated.

The paper begins with a brief discussion of governance measurement and its relevance to research and policy analysis. It then focuses on each of the 10 questions in turn, drawing on the literature and examples from various well-known measurement projects. The conclusion highlights three additional practical questions.

Governance measures and their uses

Governance is a contested concept, and this paper is intentionally agnostic about the many specific and competing definitions (see Gisselquist Citation2012; Keefer Citation2009; Andrews Citation2008; Grindle Citation2010; Fukuyama Citation2013). Broadly, the act of governance is understood here as the exercise of political power to manage a community's affairs (see Weiss Citation2000). The quality of governance, sometimes treated as equivalent to government performance, is understood to refer then to the quality of this exercise of power and the quality of this management, which may include (but is not limited to) its outcomes in terms of the quality of public goods and services received by citizens (see Bratton Citation2011, Citation2013; Rotberg and Gisselquist Citation2009; Stiglitz, Sen, and Fitoussi Citation2009).

Measurement is a major topic in the large literature on governance (see Rothstein and Teorell Citation2012; Davis et al. Citation2012; Hallerberg and Kayser Citation2013; Andrews, Hay, and Myers Citation2010). Governance can be assessed at multiple levels, but our focus is on the country level. The literature highlights a variety of approaches: Rotberg, Bhushan, and Gisselquist (Citation2013) for instance identify over a hundred country-level indexes and databases that seek to measure governance broadly defined or some core component of it.

Governance measures have been used and produced by both scholars and practitioners, but international organizations like the World Bank have largely taken the lead (see Arndt Citation2008; Davis et al. Citation2012; Thomas Citation2007; Holmberg and Rothstein Citation2012). One reason is perhaps a desire by scholars to remain independent from the so-called good governance agenda (see Grindle Citation2004). Another reason may be the role of measurement in contemporary political science, where one leading school of thought sees the principal focus of the field instead in the testing of causal theories (see King, Keohane, and Verba Citation1994). This paper suggests, on the contrary, that concept formation on core topics such as governance is central to the building of social scientific knowledge and further that established methods of concept formation and measurement can and should be applied to governance indexes (see Sartori Citation1984; Collier and Gerring Citation2009; Gerring Citation1999). Concept formation and measurement are also necessary for the testing of causal theories. Scholars may have shied away from developing governance measures, but they still use (all too often with little critical examination) existing governance measures developed at and by practitioner organizations (see Apaza Citation2009).

The best known composite indicator of governance, the WGI, underscores such links between measurement, theory development, and policy. Developed through a long-standing research program at the World Bank, the WGI has been used both in Bank publications to identify and describe governance trends around the world (e.g., World Bank Citation2007) and in scholarly articles to explore major theoretical propositions such as the relationship between governance and growth (e.g., Kaufmann, Kraay, and Mastruzzi Citation2007a; Kaufmann and Kraay Citation2002; Kurtz and Schrank Citation2007). It is also regularly cited in policy discussions, especially with reference to foreign aid (e.g., Millennium Challenge Corporation Citation2012). Not surprisingly, there is a healthy body of work analyzing and critiquing the WGI (e.g., Kurtz and Schrank Citation2007; Thomas Citation2009; Arndt and Oman Citation2006; Langbein and Knack Citation2009; Knoll and Zloczysti Citation2011).

Other measures of specific aspects of governance have also received widespread public attention. The annual results of Transparency International's CPI, for instance, are regularly reported and debated in the mainstream press. Indeed, some organizations like Transparency International use measurement projects as public advocacy tools (see Sampson Citation2010). Regardless of whether it is a part of an explicit strategy, Freedom House's Freedom in the World similarly draws attention to its work on civil and political liberties around the world; the Index of Economic Freedom produced by the Heritage Foundation, in collaboration with the Wall Street Journal, helps to frame public debate on economic issues in (self-described) ‘conservative’ terms, highlighting free enterprise, limited government, and individual freedom; and Vision of Humanity's Global Peace Index raises awareness of the importance of peace for human progress.

Indexes and composite indicators are not new. Gross domestic product is a composite indicator (of the total value of goods and services produced in a country), although it is rarely described as such (OECD and JRC Citation2008, 22). Composite indicators cover a variety of topics, from economic progress to environmental sustainability to educational quality, and many technical issues are common for all (see Saltelli Citation2007; Bandura Citation2011).

As illustrated further below, however, governance indexes are relatively unique in several ways. One is the complexity and contested nature of the concept of governance itself. A second is the difficulty of measuring many of its components, as well as the extremely poor quality of relevant statistics. Third, and related, governance measures have employed a wider range of types of data than measures of many other topics. These include not only standard national statistics such as those compiled in the census and by nationally representative surveys but also ratings by experts based on their knowledge of particular cases (e.g., Freedom House's Freedom in the World), surveys of internal or external observers (e.g., World Economic Forum's Executive Opinion Survey), aggregation of multiple such elite surveys or of these and other information sources (e.g., CPI, WGI), ratings based on questionnaires that take into account both expert background knowledge and systematic review of relevant legislation or other documentary sources (e.g., Doing Business, World Justice Project Rule of Law Index), systematic coding of reports or other documents based on a detailed protocol to produce simple scores or ratings (e.g., Cingranelli-Richards [CIRI] Human Rights Dataset), and estimated data or imputed figures for key indicators (e.g., Save the Children's Mothers’ Index, HDI).Footnote2 Indeed, given the diversity of types of data used in governance measurement projects, it is hardly surprising that there is variation across assessments.

Critiques and reviews of existing governance indicators comprise a large literature by both scholars and practitioners (e.g., Hallerberg and Kayser Citation2013; Sudders and Nahem Citation2007). Likewise, there is a large literature on the use of composite indicators in development more generally (e.g., Stiglitz, Sen, and Fitoussi Citation2009; Høyland, Moene, and Willumsen Citation2012; Ravallion Citation2012). A comprehensive review of this work is out of the scope of this article, but key points are highlighted through the discussion below.

Critical and less critical questions: a framework for evaluation

Basic social science methodology provides the core framework for evaluating governance indexes, and the literature on governance measurement highlights a handful of other issues, for a total of 10 questions. The first six questions deal with critical issues that indexes should always aim to address (concept formation, content validity, reliability, replicability, robustness, and the relevance of particular measures to underlying research questions). The final four questions (on descriptive complexity, theoretical fit, the precision of estimates, and ‘correct’ weighting) have arguably received more attention in the extant literature on governance measurement and are also important to consider, but what to do about them is open to debate; they are thus less critical. For instance, as discussed further below, all indexes should aim for rigorous, theoretically grounded concept specification (see Question 1), and it is relatedly useful to consider whether an index behaves in a manner consistent with theoretically derived hypotheses – but it is not necessarily a bad thing if it does not (see Question 8). Likewise, it is valuable to consider the precision of estimates, but specifying confidence intervals is arguably not best practice for all indexes (see Question 9).

Question 1. What precisely does it aim to measure?

Producers of governance indexes often fail to answer this question, perhaps because the answer seems so obvious (governance). Concept specification is a simpler step for concepts with more broadly agreed definitions or common theoretical frameworks; because the concept is contested, common understandings cannot be assumed. At a minimum, this conceptualization should resonate with common understandings, popular or scholarly, and the differences between what is considered ‘governance’ and related concepts like democracy and development should be made clear. More broadly, Gerring's (Citation1999, 367) eight criteria provide a useful checklist for evaluating conceptual ‘goodness’:

Familiarity - How familiar is the concept (to a lay or academic audience)?

Resonance - Does the chosen term ring (resonate)?

Parsimony - How short is a) the term and b) its list of defining attributes (the intension)?

Coherence - How internally consistent (logically related) are the instances and attributes?

Differentiation - How differentiated are the instances and the attributes (from other most-similar concepts)? How bounded, how operationalizable, is the concept?

Depth - How many accompanying properties are shared by the instances under definition?

Theoretical Utility - How useful is the concept within a wider field of inferences?

Field Utility - How useful is the concept within a field of related instances and attributes?

Indeed, many if not most governance indexes can be criticized on similar grounds. The Ibrahim Index of African Governance (IIAG), for instance, offers an exceptionally broad definition:

Governance … is considered from the viewpoint of the citizen. The definition is intentionally broad so as to capture all of the political, social and economic goods and services that any citizen has the right to expect from his or her state, and that any state has the responsibility to deliver to its citizens. The IIAG is unique in that it assesses governance by measuring outputs and outcomes. This definition of governance does not focus on de jure measurements, but rather aims to capture attainments or results, reflecting the actual status of governance performance in a given context – be it national, regional or continental. (Mo Ibrahim Foundation Citation2012, 1)

Users of governance indexes should be especially wary of projects that purport to measure ‘new’ concepts. Creative linguistics are useful for marketing, but are problematic conceptually. For instance, Gerring's criteria suggest some of the challenges with the concept of ‘transformation’ in the Bertlesmann Stiftung's Transformation Index, a composite index of two others on ‘status’ and ‘management’: Terms are used in an unfamiliar way and (arguably) do not resonate; their relationship with more commonly used concepts is not fully specified (e.g., how is ‘transformation’ differentiated from democratization and economic liberalization?); it is not clear if their components form a coherent whole; and because they are not defined with reference to a theoretical framework, their theoretical utility is not obvious.

This is not to say that conceptual innovation is not possible. One of the best examples of an index measuring a new concept is the UNDP's HDI because of its explicit grounding in Sen's work on human capabilities (Stanton Citation2007).

Poorly conceptualized measures can still be useful, but there will be limits to their theoretical and field utility. Studies that use these measures will need to specify concepts post hoc and to the extent that measures were not developed with these same conceptualizations in mind, they can only offer second best operationalizations (see Kurtz and Schrank Citation2007).

Question 2. Content validity: does the operational definition capture the concept?

Once a concept has been properly specified, the next step logically and chronologically, is to operationalize it. An operational definition should identify the component(s) to be included in the measure and specify how these components are put together in a manner that is consistent with the core concept. In the case of governance, a multidimensional concept, this generally involves the aggregation of various categories, (sometimes) sub-categories, and indicators. Index producers have a number of options in terms of how to normalize data and weight and aggregate components (see OECD and JRC Citation2008).

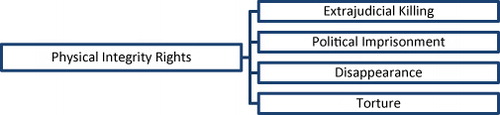

The CIRI Human Rights Dataset provides almost a textbook example of what the specification of an operational definition involves. CIRI has included two key composite indexes, a Physical Integrity Rights Index and an Empowerment Rights Index. Each is an additive index of four and seven indicators, respectively. Each indicator has a score of between 0 and 2 (which means that each indicator is weighted equally in the construction of each index). Scores for indicators are assigned based on the US State Department Country Reports on Human Rights Practices and Amnesty International's Annual Reports according to a detailed coding protocol (Cingranelli and Richards Citation2008, Citation2010). illustrates the Physical Integrity Rights Index.

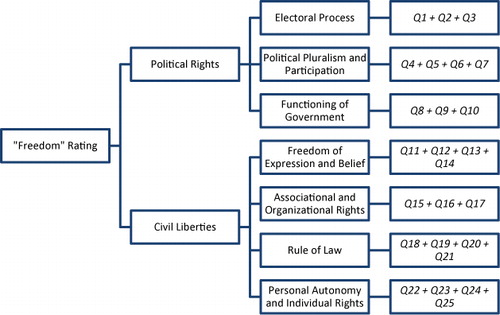

CIRI's operational definition is by no means the only way to capture these concepts. Freedom House's Freedom in the World offers one alternative focusing on the closely related concepts of ‘political rights’ (PR) and ‘civil liberties’ (CL). As summarized in , PR and CL scores are derived from scores on three and four sub-categories, respectively (Freedom House Citation2012). Each of these sub-categories aggregates the values of three to four questions, each with a value between 0 and 4, and so on. PR and CL scores are averaged to derive the overall score upon which the freedom rating is assigned.

Overall, this operational definition follows straightforwardly from Freedom House's core concept of ‘freedom,’ but several components of it call for a bit more justification. The sub-categories of ‘functioning of government’ under ‘political rights’ and ‘rule of law’ under ‘civil liberties’ in particular are somewhat unusual additions in that they do not follow clearly from the referenced Universal Declaration of Human Rights, nor are they included in other similar listings of such rights (e.g., ‘rule of law’ is not included in CIRI's Empowerment Rights Index). Weighting and some of the details of the aggregation method are also not explicitly justified, and several debatable claims about the relationships among components and their relative importance are implied by the method:

PR and CL are equally important to ‘freedom’ because they receive equal weight in deriving the final value.

PR and CL are compensatory; better scores in PR can make up for poorer scores in CL and vice versa. (CIRI's indexes are also compensatory.)

Electoral Process, Political Pluralism and Participation, and Functioning of Government are each slightly more important to freedom than are Civil Liberties, Freedom of Expression and Belief, Associational and Organizational Rights, Rule of Law, and Personal Autonomy and Individual Rights. Each of the first three sub-categories is weighted roughly 0.17 (=0.5*1/3) in the overall index, while each of the second four sub-categories is weighted 0.125 (=0.5*1/4) in the overall index. (A similar point can be made about the weighting implicit in most other governance indexes.)

For single indicators, lack of conceptual validity is often straightforward. For instance, a proposal to measure the quality of education in secondary schools based solely on an assessment of the quality of textbooks would raise validity concerns. It tends to be less clear for composite indicators. One approach that is commonly used is to assess the measure against other measures of the same concept or against other measures of different concepts that theory suggests should be related to it in a particular way. Asking whether such relationships hold is worthwhile, but as I argue under Question 8, it is less critical in assessing the validity of governance measures than it may be in some other areas.

In practice it seems that improving the fit between a concept and its operational definition tends to be an iterative process, involving adjustments over time as new techniques are proposed to fix identified weaknesses that become clear as the measure is used. Ongoing discussions over the best way to calculate the HDI offer one example (see UNDP Citation2011; Alkire Citation2010).

Question 3. How good (reliable, valid, and complete) are the data?

Technically sophisticated indexes can obscure the basic principle of garbage in, garbage out: the quality of a measure in capturing empirical realities is limited by the quality of the underlying data used to construct it. Assessing whether the operationalization of a concept is valid involves assessing not only design features (see Question 2) but also data quality. Validity refers to whether the measure accurately captures what it purports to capture. Reliability refers to the consistency of the measure. For instance, a national measure of pre-trial detention would be reliable if multiple sources (from prison officials to observers from the International Committee of the Red Cross) all provided the same estimate, but it would not be valid if all of these estimates actually pertained to pre-trial detention in the capital city only.

Such basic data problems are more common than users of governance measures tend to expect. One example is offered by literacy rates used in several sources for Zimbabwe in the 2000s: at 89.5% (2004) and 91.2% (2007), the highest in Africa after the Seychelles’ (UNESCO Institute of Statistics Citation2009). These rates rely on national reporting and Zimbabwe adopts a relatively minimal definition based on ‘the population aged 15 years and above who have completed at least grade three’ (UNESCO Citation2000). Regardless of whether the Zimbabwean definition should be considered valid for Zimbabwe, the use of varying definitions across countries complicates the validity of cross-national comparison. Similar challenges with the measurement of some indicators such as maternal mortality have been addressed by using available measurements to estimate new figures (although again these estimates are only as good as the model from which they are derived) (e.g., Say et al. Citation2007).

In measurement projects that rely on coding based on detailed protocols, such as Polity IV and CIRI, for instance, variations in assessments across coders can also pose reliability challenges. Validity poses problems as well, even with expert coders. For instance, a rating of institutional quality for a country for a given year would be reliable if it was consistent with multiple sources, but it would not be valid if it was based on assessment of institutional quality in the previous year (due to lack of new information or the assumption of stability). For countries and topics for which information is poor, multiple experts may assess institutional quality for this country in the same way, giving reliable, but not valid, ratings.

A final issue is data incompleteness. Given the extremely poor quality of statistics in many developing countries and particularly for sub-Saharan Africa, it is not unusual for a quarter of relevant data points to be missing in standard statistical compilations on governance-relevant topics (see Rotberg and Gisselquist Citation2009).

Assessing crime and rule of law in governance indexes poses especially difficult challenges (see Stone Citation2012). For one, definitions and methods tend to vary across countries (e.g., some may focus on murder but not on manslaughter, some may compile information on reported crimes and others on convictions only). Other challenges relate to incentives by perpetrators and others to conceal criminal activity or corrupt practices. The functioning of the criminal justice system itself affects statistics as very weak rule of law institutions and cultural norms may deter reporting of crimes (thus complicating the interpretation of variation in official crime statistics).

Question 4. Is the measure (including all of its sub-components) transparent and replicable?

In order to answer Questions 2 and 3, users of governance indexes need to dig deep into data and methods. All too often, this is not possible because index producers release only final scores or rankings without underlying data and methods. This lack of transparency means that far too many index projects disregard a basic principle of good social science, replicability.

Being fully transparent poses clear risks and challenges for index producers. First, it makes finding mistakes much easier, giving index producers an incentive to obscure information to avoid correction and embarrassment. This is arguably the main reason that we should be concerned if index producers are not transparent. Second, index authors may have a variety of concerns about the use of their data and methods. For instance, they may naturally want to publish off the data themselves before releasing them. Third, making available detailed information takes work. The producers of policy-relevant indexes generally do not enjoy the same luxury of control and time in publishing their results as authors of articles in scholarly journals and it may take several editions of an index for its authors to catch up with the writing and reporting needed for full transparency. Fourth, many indexes are ultimately produced as advocacy tools, a way to engage with policy-makers and the wider public, audiences for which detailed notes on sources and methodology may be of little interest. Websites offer a very simple solution here: make the details available on the web for those interested. A fifth and especially difficult issue is what to do about underlying data that is proprietary or should not be in the public domain for other reasons. For instance, it is not ethical to publically release data that can be used to identify individual survey respondents, and the World Bank's CPIA cannot release its raw data because it would reveal assessment of country politics by Bank staff. Solutions in such cases are complicated, but the basic principle should be to make as much of the information available as possible, at least to other experts who can independently evaluate it.

Beyond good scientific methods, index producers should care about transparency and replicability because they carry political weight. Indeed, the literature on good governance itself emphasizes the value of transparency and of strengthening processes of accountability and engagement – including through open data (see United Nations Citation2013; Round Citation2012).

Question 5. How sensitive and robust is the measure to different data and design choices?

As the preceding text suggests, data and design choices in governance measurement are not an exact science, despite what some of the literature suggests. There are few hard rules about the ‘best’ data sources, indicators, methods of normalization, and weighting and aggregation. Well-designed indexes however describe and justify their choices in each of these areas and examine the impact of these choices on the robustness of results. Index producers can make final scores illustrate almost anything by carefully selecting indicators and adjusting the weighting of components; they have the burden of showing that they are not (at least intentionally) cherry picking.

Sensitivity and robustness should ideally be assessed in multiple ways. One good example of how to assess the effect of data sources is provided by the CIRI project, which conducted analyses using different sources to code its indicators (Cingranelli and Richards Citation1999; Richards, Gelleny, and Sacko Citation2001). Another is offered by the work of the JRC, which has conducted sensitivity analyses for multiple indexes focused on the impact of different weighting choices (Saisana, Annoni, and Nardo Citation2009; Paruolo, Saisana, and Saltelli Citation2013; Saisana, Saltelli, and Tarantola Citation2005). As each of these analyses suggests, the final values of an index will change to some extent when different data and methods are used – no matter how well constructed the index. The purpose of such analysis is to understand precisely how, making clear the impact of data and design choices that may not otherwise be obvious and pointing either to the need for further justification of these choices or for reassessment and redesign.

Question 6. Does the measure allow the analyst to address key questions of interest?

Question 6 is the first question most index users will ask, but to answer it well, they first need answers to the above questions. In addition to considering whether the concept and operational definition are relevant, index users should consider whether it captures empirically what is under investigation, including country coverage, time coverage, and the level of analysis at which measurement is taken (see Gingerich Citation2013). The predictive ability of an index is also important for many users.

This question is deceptively simple. Sometimes answers are straightforward: the IIAG compiles information on Africa only so is not relevant to addressing questions about governance trends in Asia, nor can the WGI give governance measures prior to 1996, the first year for which it was compiled. Nor do either reflect the latest current events – as each are only annually produced.

Sometimes they are open to debate: For instance, both the CPI and WGI are regularly used to analyze governance over time. For the CPI, this is against the warnings of its producers, who have noted that because it relies on different sources in each year, it should not be used to study corruption over time.Footnote3 However, the WGI also uses different sources in each year and its producers find that it can be used to study diachronic variation (Kaufmann, Kraay, and Mastruzzi Citation2007b).

Question 7. Does the measure fully capture governance in all its complexity?

As noted above, a major critique of governance indexes is that they are just too simple and thus add little to other forms of governance assessment. A related set of critiques highlight how national governance indicators can be made more useful by including more components (e.g., Farrington Citation2010) or moving in various ways beyond national aggregates, for instance, to capture sub-national variation (e.g., Gingerich Citation2013).

Conceptual development is important (see Question 1) and this question is worth considering, but I propose it is less critical than the six above for two reasons. First, as Gerring's criteria highlight, there is value in parsimony. A challenge for most measurement projects is to develop an operational definition that is just complex enough to capture key concepts or processes and to facilitate comparisons. Identifying particular indicators left out of governance indexes thus is generally not much of a challenge. Simplicity is also only problematic when it involves excluding core dimensions of governance or means that the index does not then capture what it purports to.

Indeed, one school of thought implies that indicators should be stripped down to include only the components most important to the measure (e.g., through principal components analysis) (see Langbein and Knack Citation2009). This approach also does not make sense for all governance indexes. Particularly when the objective of an index is conceptual development, and when it is not clear how components should fit together, more rather than less descriptive complexity may be justified.

A second reason that this question is less critical than the others has to do with how governance indexes should be used. Governance indexes are useful tools in comparing complex sets of information and exploring trends and relationships, essentially first cuts at developing and testing broad hypotheses at the aggregate level. An analyst trying to understand in detail the mechanisms and processes behind the sort of broad relationships described in indexes should be expected to look beyond such aggregates, for instance, through careful qualitative case studies or quantitative analysis of more disaggregated data. Sole focus on developing an increasingly complex single aggregate measure often means that this sort of (equally important) disaggregated analysis is ignored.

Question 8. Does the measure behave as theory predicts?

Theory is important to rigorous governance measurement in the sense that measures should be developed with reference to and within theoretical frameworks so that they can speak to and be used to test theoretical propositions (see Andrews Citation2008). Thus, it is worth considering whether an index behaves as theory predicts. The literature highlights two approaches in particular. The first involves assessing the validity of a measure by assessing it against other measures of the same concept with the implication that valid measures of the same concept should be consistent (see Thomas Citation2009). The second involves assessing the validity of a measure by exploring how it is related to other concepts in a manner consistent with theoretically derived hypotheses, for instance, exploring the relationship between governance and growth as has been done using the WGI (Kaufmann and Kraay Citation2002, Citation2008).

In the case of governance indicators, however, both of these approaches are problematic and this question is thus less critical in their design and evaluation. One problem with using the first approach goes back to Question 1: Given the diversity of ways in which governance is defined, we need to be careful about comparing measures of ‘governance’ that are actually designed to capture different things. Another problem given the current state of governance measurement is that, even if we can be sure that measures should be equivalent, the approach is only as good as existing measures. Even the most well-cited measures of governance have weaknesses, as the literature highlights, and given these weaknesses, it is not clear that a new indicator of governance that does not correlate well with existing governance measures should be rejected.

The key problem with the second approach is that we simply do not know if hypothesized relationships are correct, in particular the relationship between governance and growth (Khan Citation2009; Resnick and Birner Citation2006). Thus, evaluating the goodness of constructs based on whether they fit theoretical hypotheses – that is, unproven propositions – limits our ability to use these constructs to test hypotheses, as well as to build conceptual knowledge and theory more generally.

Question 9. How precise are index values and are confidence intervals specified?

Governance indexes produce overall scores that are imprecise and uncertain. Given this, the numerical differences between some scores or ranks may in fact not be very meaningful. One way to capture this sort of imprecision and uncertainty in survey research is to report confidence intervals or margins of error in addition to point estimates, an approach often preferred by statisticians and common, for instance, even in popular reporting on the results of pre-election polling. In general, the smaller the sample size, the larger the possibility of measurement error and thus the larger the margin of error or confidence interval. For this reason, the WGI and the CPI report 90% ‘confidence intervals’ and many observers have argued that such reporting should be done for all governance indexes (see Kaufmann and Kraay Citation2008, 18).

The underlying desire here for clear, accurate reporting of results is important, and Question 9 is well worth asking. However, it is less critical to the development and evaluation of governance indexes than other questions because of the type of data often used in government measurement.

In practice, the reporting of confidence intervals in governance indexes can be misleading because what are reported as confidence intervals are not the same thing we normally think of as confidence intervals. For instance, the WGI is not a survey but a compilation of data from multiple sources, some of which are surveys of public or elite opinion (e.g., Afrobarometer, Latin American Public Opinion Project, Gallup International Millennium Survey) and some of which are based on coding by experts (e.g., International Country Risk Guide, EIU Country Risk Service, Freedom in the World, Index of Economic Freedom). The WGI's ‘confidence intervals’ are calculated as the point estimate plus and minus 1.64 times its estimated standard error, which is estimated based on the number of sources and the authors’ estimation of the accuracy of these sources (Arndt and Oman Citation2006, 64). The estimation of the standard error is not based on the survey sample size, but rather on the number of assessments for each country and the degree to which their scores are consistent with each other. This calculation further involves the key assumption that sources are independent of each other and thus that correlation of their scores is due to better measurement of the ‘real’ value of governance. However, even the WGI's authors recognize that this is a major assumption (Kaufmann, Kraay, and Zoido-Lobatón Citation1999). It is likely for instance that some of its sources in fact draw on each other in their assessments.

In short, there may be good reasons for governance indexes not to publish such constructed confidence intervals so not doing so is not necessarily a weakness. On the other hand, index producers should somehow acknowledge the uncertainty and imprecision surrounding scores. Indexes that rank countries in particular may effectively obscure this imprecision because assigning ranks may suggest to users that small differences in scores are more meaningful than they are. This is one argument against ranking. One approach to consider is the assignment of grouped scores or ranks, rather than single figures for each country. Freedom House's Freedom in the World, for instance, assigns only one of three overall values (free, partially free, and not free).

Question 10. Is the weighting ‘correct’?

Discussions of governance indicators, especially in policy circles, pay a lot of attention to this question, especially relative to the consideration given to other index design features such as data normalization and aggregation (see Paruolo, Saisana, and Saltelli Citation2013). It is worth considering: As Question 2 suggests, weighting decisions are an important component of an operational definition and should be carefully considered in developing and evaluating an index. As the Freedom in the World example illustrates, many governance indexes average across components and do not explicitly discuss weighting, but implicit weighting choices can still be evaluated. As Question 5 highlights, the sensitivity of an index to different weighting choices is one issue to consider in evaluating its robustness.

However, in evaluating governance measures, I propose that this question is less critical than others because existing theory in fact gives us little clear guidance on assessing the ‘correctness’ of weighting without reliance on normative or practical considerations: Weighting in governance indexes is generally derived with one of two principles in mind, the degree of confidence in each component's accuracy (e.g., WGI) and the relative importance of each component to governance (e.g., IIAG). In practice, the first tends to rely on the problematic assumption that sources’ errors are uncorrelated, which is touched on above (Arndt and Oman Citation2006). The second is problematic because most theories of governance are not very specific about the relative importance of governance dimensions. Rotberg and West (Citation2004), for instance, propose a hierarchy of political goods in which security is especially important, but it still does not tell us precisely how much security should be weighed in quantitative terms relative to other components. One might also argue that security is so important in the hierarchy that the value of governance should be zero if security is poor, regardless of values on all other dimensions. In short, this question should be considered carefully, but keeping in mind the limitations of existing theory.

Conclusions

This paper has argued that the users and producers of governance measures should, first, pay more attention to the fundamentals of social science methodology – that is, concept formation, content validity, reliability, replicability, robustness, and the relevance of particular measures to underlying research questions – and second, pay less attention to some other issues more commonly highlighted in the literature on governance measurement – that is, descriptive complexity, theoretical fit, the precision of estimates, and ‘correct’ weighting. Both sets of questions are worth consideration, but it argues that the first set is more critical than the second.

For would-be index producers and funders, there are also additional practical and strategic questions to consider. First, in deciding whether to produce a new governance index, they should consider its value-added in a field with dozens of existing measures. Second, does the utility of the index justify its costs? Would money better be spent on other types of governance assessments? Is it cost-effective to undertake intensive data gathering efforts for an index? In every country or selected ones? For which indicators? Third, legitimacy: Governance assessments can have major real-world implications, from aid allocations to investor perceptions. Will the index as designed and implemented be considered legitimate by those assessed? In general, we might expect an assessment to be considered more legitimate when it is conducted by impartial observers, as well as when methods and data are transparent, allowing for replication. In governance assessment, however, it is clear that local evaluation is often important for local legitimacy. Should this be taken into account in the design of a particular index? And so on.

Clearly, many well-known governance indexes are first and foremost practical and political tools for promoting better governance. This paper argues, however, that their development can nevertheless also engage some of the core skills of social science: concept specification and measurement. Indeed, the best governance indexes, as judged by the framework proposed here, contribute to social scientific knowledge by ‘combin[ing] discrete facts … into a category, helping us to see the confusing universe in which we live a more patterned way’ (Laitin Citation1995, 455–456).

Notes on contributor

Rachel M. Gisselquist, a political scientist, is a Research Fellow with United Nations University, World Institute for Development Economics Research. She works on the politics of the developing world, with particular attention to ethnic politics and inequality, state fragility, governance, democratization, and sub-Saharan African politics. Her research is published in various scholarly journals and edited books. Among her policy publications, she is co-author of the first two editions of the Ibrahim Index of African Governance.

Acknowledgments

Many of the ideas in this paper were developed through my work at Harvard on the Index of African Governance with Robert I. Rotberg. I am grateful to him for the invitation to the work on the project and his insightful comments and advice, as well as to our many contributors and collaborators in the project. This paper was written at the United Nations University, World Institute for Development Economics Research and its support is gratefully acknowledged. I thank also Aniket Bhushan, Omar McDoom, three anonymous reviewers, and participants in a June 2013 workshop on ‘Measuring Governance Effectiveness: National and International Dimensions’ hosted by the Centre for International Governance Innovation and the North-South Institute, for thoughtful comments.

Notes

1. The author worked with Robert I. Rotberg to design and co-author the first two editions of the Ibrahim Index of African Governance (IIAG), which has become one of the best-known measures of governance for Africa (see Rotberg and Gisselquist Citation2009). Mitra (Citation2013, 489) describes the IIAG as ‘a well-established index that has become a reference point for governments and NGOs’. This paper draws on several examples from that research, but it is not the focus here.

2. As this list suggests, an important related issue is how to quantify qualitative observations. Questions 2 and 3 touch on this issue, but readers may wish to refer to more extensive discussions in the literature (see, e.g., Chi Citation1997; Nardo Citation2003; Mitchell, Smith, and Weale Citation2002; Hanson Citation2008).

3. See, e.g., http://www.transparency.org/cpi2011/in_detail#myAnchor6. The 2012 CPI, however, employs a slightly different method for greater comparability.

References

- Alkire, Sabina. 2010. “Human Development: Definitions, Critiques, and Related Concepts.” Human Development Research Paper. New York: United Nations Development Programme.

- Andrews, Matt. 2008. “The Good Governance Agenda: Beyond Indicators without Theory.” Oxford Development Studies 36 (4): 379–407. doi:10.1080/13600810802455120.

- Andrews, Matt, Roger Hay, and Jerrett Myers. 2010. “Can Governance Indicators Make Sense? Towards a New Approach to Sector-Specific Measures of Governance.” Oxford Development Studies 38 (4): 391–410. doi:10.1080/13600818.2010.524696.

- Apaza, Carmen R. 2009. “Measuring Governance and Corruption through the Worldwide Governance Indicators: Critiques, Responses, and Ongoing Scholarly Discussion.” PS: Political Science & Politics 42 (1): 139–143. doi:10.1017/S1049096509090106.

- Arndt, Christiane. 2008. “The Politics of Governance Ratings.” International Public Management Journal 11 (3): 275–297. doi:10.1080/10967490802301278.

- Arndt, Christiane, and Charles Oman. 2006. Uses and Abuses of Governance Indicators. Paris: OECD Development Centre.

- Bandura, Romina. 2011. “Composite Indicators and Rankings: Inventory 2011.” Unpublished paper.

- Bersch, Katherine, and Sandra Botero. 2014. “Measuring Governance: Implications of Conceptual Choices.” European Journal of Development Research 26 (1): 124–141. doi:10.1057/ejdr.2013.49.

- Bevir, Mark, and Rod Rhodes. 2006. Governance Stories, Routledge Advances in European Politics. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Bratton, Michael. 2011. “The Democracy-Governance Connection.” In Governing Africa's Changing Societies: Dynamics of Reform, edited by Ellen Lust and Stephen Ndegwa, 19–44. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner.

- Bratton, Michael. 2013. “Governance: Disaggregating Concept and Measurement.” APSA-Comparative Politics Newsletter 23 (1): 12–13.

- Chi, Michelene T.H. 1997. “Quantifying Qualitative Analyses of Verbal Data: A Practical Guide.” Journal of the Learning Sciences 6 (3): 271–315. doi:10.1207/s15327809jls0603_1.

- Cingranelli, David L., and David L. Richards. 1999. “Measuring the Level, Pattern, and Sequence of Government Respect for Physical Integrity Rights.” International Studies Quarterly 43 (2): 407–417. doi:10.1111/0020-8833.00126.

- Cingranelli, David L., and David L. Richards. 2008. The Cingranelli-Richards (CIRI) Human Rights Data Project Coding Manual Version 7.30.08. Accessed June 4, 2013. http://ciri.binghamton.edu/documentation/ciri_coding_guide.pdf.

- Cingranelli, David L., and David L. Richards. 2010. Short Variable Descriptions for Indicators in the Cingranelli-Richards (CIRI) Human Rights Dataset. Document Version 11.22.10. Accessed June 4, 2013. http://www.humanrightsdata.org/documentation/ciri_variables_short_descriptions.pdf.

- Collier, David, and John Gerring. 2009. Concepts & Method in Social Science: The Tradition of Giovanni Sartori. Oxford: Routledge.

- Davis, Kevin E., Angelina Fisher, Benedict Kingsbury, and Sally Engle Merry, eds. 2012. Governance by Indicators: Global Power through Quantification and Rankings, Law and Global Governance. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Farrington, Conor. 2010. “Putting Good Governance into Practice II: Critiquing and Extending the Ibrahim Index of African Governance.” Progress in Development Studies 10: 81–86. doi:10.1177/146499340901000106.

- Freedom House. 2012. “Methodology.” Freedom House. Accessed June 11, 2013. http://www.freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world-2012/methodology.

- Fukuyama, Francis. 2013. “What Is Governance?” Governance 26 (3): 347–368. doi:10.1111/gove.12035.

- Gerring, John. 1999. “What Makes a Concept Good? A Criterial Framework for Understanding Concept Formation in the Social Sciences.” Polity 31 (3): 357–393. doi:10.2307/3235246.

- Gingerich, Daniel W. 2013. “Governance Indicators and the Level of Analysis Problem: Empirical Findings from South America.” British Journal of Political Science 43 (3): 505–540. doi:10.1017/S0007123412000403.

- Gisselquist, Rachel M. 2012. “Good Governance as a Concept, and Why This Matters for Development Policy.” UNU-WIDER Working Paper. Helsinki: United Nations University, World Institute for Development Economics Research (UNU-WIDER).

- Grindle, Merilee S. 2004. “Good Enough Governance: Poverty Reduction and Reform in Developing Countries.” Governance 17 (4): 525–548. doi:10.1111/j.0952-1895.2004.00256.x.

- Grindle, Merilee S. 2010. “Good Governance: The Inflation of an Idea.” Faculty Research Working Paper Series, RWP 10-023. Harvard Kennedy School.

- Hallerberg, Mark, and Mark Kayser. 2013. “Measuring Governance.” APSA-Comparative Politics Newsletter 23 (1): 1–2.

- Hanson, Barbara. 2008. “Wither Qualitative/Quantitative? Grounds for Methodological Convergence.” Quality & Quantity 42 (1): 97–111. doi:10.1007/s11135-006-9041-7.

- Harttgen, Kenneth, and Stephan Klasen. 2012. “A Household-Based Human Development Index.” World Development 40 (5): 878–899. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2011.09.011.

- Holmberg, Sören, and Bo Rothstein, eds. 2012. Good Government: The Relevance of Political Science. Cheltenham and Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar.

- Høyland, Bjørn, Karl Moene, and Fredrik Willumsen. 2012. “The Tyranny of International Index Rankings.” Journal of Development Economics 97 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1016/j.jdeveco.2011.01.007.

- Hyden, Goran, Julius Court, and Kenneth Mease. 2003. Making Sense of Governance: The Need for Involving Local Stakeholders. London: Overseas Development Institute.

- Kaufmann, Daniel, and Aart Kraay. 2002. “Governance without Growth.” Economia 3 (1): 169–229.

- Kaufmann, Daniel, and Art Kraay. 2008. “Governance Indicators: Where Are We, Where Should We Be Going?” The World Bank Research Observer 23 (1): 1–30. doi:10.1093/wbro/lkm012.

- Kaufmann, Daniel, Aart Kraay, and Massimo Mastruzzi. 2007a. “Growth and Governance: A Reply.” Journal of Politics 69 (2): 555–562. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2508.2007.00550.x.

- Kaufmann, Daniel, Aart Kraay, and Massimo Mastruzzi. 2007b. “The Worldwide Governance Indicators Project: Answering the Critics.” World Bank Policy Research Working Paper. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Kaufmann, Daniel, Aart Kraay, and Pablo Zoido-Lobatón. 1999. Aggregating Governance Indicators. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Keefer, Philip. 2009. “Governance.” In The Sage Handbook of Comparative Politics, edited by Todd Landman and Neil Robinson, 439–462. London: Sage.

- Khan, Mushtaq H. 2009. “Governance, Growth and Poverty Reduction.” DESA Working Paper No. 75. Department of Economic and Social Affairs, United Nations.

- King, Gary, Robert O. Keohane, and Sidney Verba. 1994. Designing Social Inquiry: Scientific Inference in Qualitative Research. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Knack, Stephen. 2006. “Measuring Corruption in Eastern Europe and Central Asia: A Critique of the Cross-Country Indicators.” SSRN eLibrary.

- Knoll, Martin, and Petra Zloczysti. 2011. “The Good Governance Indicators of the Millennium Challenge Account: How Many Dimensions Are Really Being Measured?” DIW Berlin Discussion Papers. Berlin: Deutsches Institut fur Wirtschaftsforschung.

- Kraay, Art, and Peter Murrell. 2013. “Misunderestimating Corruption.” Policy Research Working Paper 6488. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Kurtz, Marcus J., and Andrew Schrank. 2007. “Growth and Governance: Models, Measures, and Mechanisms.” Journal of Politics 69 (2): 538–554. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2508.2007.00549.x.

- Laitin, David. 1995. “Disciplining Political Science.” American Political Science Review 89 (2): 454–456. doi:10.1017/S0003055400096453.

- Langbein, Laura, and Stephen Knack. 2009. “The Worldwide Governance Indicators: Six, One, or None?” The Journal of Development Studies 46 (2): 350–370. doi:10.1080/00220380902952399.

- McFerson, Hazel M. 2009. “Measuring African Governance: By Attributes or by Results?” Journal of Developing Societies 25 (2): 253–274. doi:10.1177/0169796X0902500206.

- Millennium Challenge Corporation. 2012. Guide to the MCC Indicators and the Selection Process for Fiscal Year 2013. Washington, DC: Millennium Challenge Corporation.

- Mitchell, James, Richard J. Smith, and Martin R. Weale. 2002. “Quantification of Qualitative Firm-Level Survey Data.” The Economic Journal 112 (478): C117–C135. doi:10.1111/1468-0297.00021.

- Mitra, Shabana. 2013. “Towards a Multidimensional Measure of Governance.” Social Indicators Research 112 (2): 477–496.

- Mo Ibrahim Foundation. 2012. The 2012 Ibrahim Index of African Governance (IIAG) – Methodology. London: Mo Ibrahim Foundation.

- Nardo, Michela. 2003. “The Quantification of Qualitative Survey Data: A Critical Assessment.” Journal of Economic Surveys 17 (5): 645–668. doi:10.1046/j.1467-6419.2003.00208.x.

- OECD and JRC. 2008. Handbook on Constructing Composite Indicators: Methodology and User Guide. Paris: OECD.

- Olken, Benjamin A. 2009. “Corruption Perceptions vs. Corruption Reality.” Journal of Public Economics 93 (7–8): 950–964. doi:10.1016/j.jpubeco.2009.03.001.

- Paruolo, Paolo, Michaela Saisana, and Andrea Saltelli. 2013. “Ratings and Rankings: Voodoo or Science?” Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series A (Statistics in Society) 176 (3): 609–634. doi:10.1111/j.1467-985X.2012.01059.x.

- Ravallion, Martin. 2012. “Mashup Indices of Development.” The World Bank Research Observer 27 (1): 1–32. doi:10.1093/wbro/lkr009.

- Razafindrakoto, Mireille, and François Roubaud. 2010. “Are International Databases on Corruption Reliable? A Comparison of Expert Opinion Surveys and Household Surveys in Sub-Saharan Africa.” World Development 38 (8): 1057–1069. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2010.02.004.

- Resnick, Danielle, and Regina Birner. 2006. “Does Good Governance Contribute to Pro-Poor Growth? A Review of the Evidence from Cross-Country Studies.” DSGD Discussion Paper No. 30. Development Strategy and Governance Division, International Food Policy Research Institute.

- Richards, David L., Ronald Gelleny, and David Sacko. 2001. “Money with a Mean Streak? Foreign Economic Penetration and Government Respect for Human Rights in Developing Countries.” International Studies Quarterly 45 (2): 219–239. doi:10.1111/0020-8833.00189.

- Rotberg, Robert I., Aniket Bhushan, and Rachel M. Gisselquist. 2013. “The Indexes of Governance.” Measuring Governance Effectiveness: National and International Dimensions, a conference sponsored by the Centre for International Governance Innovation and the North-South Institute, Waterloo, Canada, June 19–20.

- Rotberg, Robert I., and Deborah L. West. 2004. “The Good Governance Problem: Doing Something about It.” WPF Reports. Cambridge, MA: World Peace Foundation and Harvard Kennedy School.

- Rotberg, Robert I., and Rachel M. Gisselquist. 2009. Strengthening African Governance – Index of African Governance: Results and Rankings 2009. Cambridge, MA: Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University, and World Peace Foundation.

- Rothstein, Bo, and Jan Teorell. 2012. “Defining and Measuring Quality of Government.” In Good Government: The Relevance of Political Science, edited by Sören Holmberg and Bo Rothstein, 13–39. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

- Round, Jeffery I. 2012. “Aid and Investment in Statistics for Africa.” Working Paper No. 2012/93. UNU-WIDER.

- Saisana, M., A. Saltelli, and S. Tarantola. 2005. “Uncertainty and Sensitivity Analysis Techniques as Tools for the Quality Assessment of Composite Indicators.” Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series A (Statistics in Society) 168 (2): 307–323. doi:10.1111/j.1467-985X.2005.00350.x.

- Saisana, Michaela, Paola Annoni, and Michela Nardo. 2009. “A Robust Model to Measure Governance in African Countries.” JRC Scientific and Technical Reports. European Commission Joint Research Centre, Institute for the Protection and Security of the Citizen.

- Saltelli, Andrea. 2007. “Composite Indicators between Analysis and Advocacy.” Social Indicators Research 81 (1): 65–77. doi:10.1007/s11205-006-0024-9.

- Sampson, Steven. 2010. “Diagnostics: Indicators and Transparency in the Anti-corruption Industry.” In Transparenz: Multidiszplinäre Durchsichten durch Phönomene und theorien des Undurchsichtigen, edited by S. Jansen, E. Schröter, and N. Stehr, 97–111. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

- Sartori, Giovanni. 1984. Social Science Concepts: A Systematic Analysis. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

- Say, Lale, Mie Inoue, Samuel Mills, and Emi Suzuki. 2007. Maternal Mortality in 2005: Estimates Developed by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, and the World Bank. Geneva: WHO.

- Stanton, Elizabeth A. 2007. “The Human Development Index: A History.” In PERI Working Paper. Amherst, Massachusetts: Political Economy Research Institute (PERI), University of Massachusetts-Amherst.

- Stiglitz, Joseph E., Amartya Sen, and Jean-Paul Fitoussi. 2009. Report by the Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress. www.stiglitz-sen-fitoussi.fr.

- Stone, Christopher. 2012. “Problems of Power in the Design of Indicators of Safety and Justice.” In Governance by Indicators: Global Power through Quantification and Rankings, edited by Kevin E. Davis, Angelina Fisher, Benedict Kingsbury, and Sally Engle Merry, 281–294. Oxford: Institute for International Law and Justice, New York University School of Law, and Oxford University Press.

- Sudders, Matthew, and Joachim Nahem. 2007. Governance Indicators: A Users’ Guide. Oslo: Oslo Governance Centre, United Nations Development Programme.

- Thomas, M.A. 2007. “The Governance Bank.” International Affairs 83 (4): 729–745. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2346.2007.00649.x.

- Thomas, M.A. 2009. “What Do the Worldwide Governance Indicators Measure?” European Journal of Development Research 22 (1): 31–54. doi:10.1057/ejdr.2009.32.

- UNDP. 2011. Human Development Report 2011. Sustainability and Equity: A Better Future for All. New York: UNDP.

- UNESCO. 2000. “The EFA 2000 Assessment: Country Reports.” In Education for All the 2000 Assessment: Republic of Zimbabwe, edited by UNESCO. New York: UNESCO.

- UNESCO Institute of Statistics. 2009. “National Literacy Rates for Youths (15–24) and Adults (15+).” Accessed June 3. http://stats.uis.unesco.org.

- United Nations. 2013. A New Global Partnership: Eradicate Poverty and Transform Economies through Sustainable Development. The Report of the High-Level Panel of Eminent Persons on the Post-2015 Development Agenda. New York: United Nations.

- Van de Walle, Steven. 2006. “The State of the World's Bureaucracies.” Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice 8 (4): 437–448. doi:10.1080/13876980600971409.

- Weiss, Thomas G. 2000. “Governance, Good Governance and Global Governance: Conceptual and Actual Challenges.” Third World Quarterly 21: 795–814. doi:10.1080/713701075.

- Williams, Gareth. 2011. “What Makes a Good Governance Indicator?” Policy Practice Brief. Brighton: The Policy Practice.

- World Bank. 2007. A Decade of Measuring the Quality of Governance. Governance Matters 2007: Worldwide Governance Indicators, 1996–2006. Washington, DC: World Bank.