ABSTRACT

This article presents a new and innovative framework to help analyse policy-making and depoliticisation within subnational governance arrangements. By focusing on the capacity (not the autonomy) of subnational governments to achieve their political objectives, and incorporating external actors along both the vertical and horizontal dimensions, it provides a dynamic tool to understand the extent to which municipal governments influence local policy-making processes. Furthermore, it stresses that greater ‘localism’ (or independence) between vertical tiers of government is likely to weaken subnational bodies and result in them becoming more interdependent with (or even dependent on) horizontal non-state actors within the locality. This would weaken their position in local governance arrangements and exacerbate the depoliticised nature of decision-making.

Introduction

In recent decades, particularly as policy-makers have sought to address an increasing number of ‘wicked issues’ (Rittel and Webber Citation1973), scholars have begun to appreciate the crucial role of subnational bodies in the delivery of public goods and services (Ostrom Citation1990; Putnam, Leonardi, and Nonetti Citation1993; Savitch and Kantor Citation2002). Such issues (which include climate change, obesity, overfishing, migration and teenage pregnancy) cannot be solved solely by national governments: indeed, in order to deal with them effectively, a whole range of state and non-state actors need to be involved in ‘governance’ arrangements. In response, public bodies in many Western countries have developed policy together with non-state actors, in order to try and respond to complex problems more effectively (Rhodes Citation1997; Lowndes and Skelcher Citation1998; Geddes Citation2005; Weber and Khademian Citation2008; Mayntz Citation2010). At the same time, politicians have allocated an increasing number of functions to ‘arms-length’ institutions, which has ‘depoliticised’ decision-making (Flinders and Wood Citation2014), and led some to argue that we are moving towards a ‘post-democratic’ era (Crouch Citation2004). This is in spite of the fact that countries such as the UK and Australia have espoused principles of ‘localism’ and the devolution of responsibilities to subnational levels, in an attempt to strengthen democratic engagement and/or deal with such complex problems more effectively (Evans, Marsh, and Stoker Citation2013).

Since governance – by definition – means that various different actors are involved in decision-making processes, this new situation means it is much more difficult to identify who is influencing policy. This becomes even more complex when issues cut across jurisdictional and administrative tiers of government – an increasingly common occurrence in the era of wicked issues. Although ideas of ‘multi-level governance’ (Marks Citation1993; Hooghe and Marks Citation2003) have proved popular in the past, they do not provide the analytical tools to understand which actors are shaping decision-making processes and therefore the reasons why a particular jurisdiction takes a specific policy approach (Rosamond Citation2000; Smith Citation2003; Zito Citation2015).

This article builds on Rhodes' (Citation1981) notion of power dependency in central–local relations and Stone’s (Citation1989) concept of ‘urban regimes’ to present an innovative and dynamic theoretical framework that helps to understand policy-making at the subnational level. Notably, the model takes account of other governance actors along both the ‘vertical’ and ‘horizontal’ dimensions (higher tiers of government and other local organisations respectively), and allows scholars to pinpoint whether subnational bodies are independent of, interdependent with or dependent on these other stakeholders. This enables us to identify the most powerful actors within subnational jurisdictions, and therefore which stakeholders are influencing decision-making and policy outputs.

The next section gives a brief overview of the methodology adopted to develop the theoretical framework, and this is followed by a discussion of the existing literature on multi-level and urban governance. The article then sets out the new theoretical framework, before concluding with suggestions as to how scholars might wish to apply the approach in empirical study.

Methodology

This article developed from a critical reading of various literatures on subnational governance, which revealed gaps in the theoretical understanding of local policy-making arrangements. These gaps became apparent when existing theories could not adequately explain the empirical findings from comparative fieldwork in one English and one German municipality between 2012 and 2014. As such, the framework is the product of both inductive and deductive reasoning, since it draws not only on existing theoretical approaches but also on specific observations in the field.

Existing perspectives on multi-level and urban governance

Governance, defined as ‘the involvement of society in the process of governing’ (Hill and Hupe Citation2002, 14), suggests that public officials work more collaboratively with external actors in formulating and implementing policy. In recent decades it has become an influential leitmotif in studies of subnational policy-making in various sectors (Miller, Dickson, and Stoker Citation2000; John Citation2001; Heinelt Citation2002; Stoker Citation2003; Bulkeley and Betsill Citation2005; Pierre and Peters Citation2012). This is particularly the case where decision-makers have sought to involve a range of different actors in their strategies to address ‘wicked’ policy issues – problems that may defy resolution due to the conflicting interests of those stakeholders who are affected by them.

These studies have often referred to the idea of multi-level governance – the notion that governance ‘happens’ both within and between local, regional, national and international tiers. This term was first coined by Marks (Citation1993) to describe the workings of the European Union (EU) and its member states, before gaining wider currency. Indeed, the emergence of supranational institutions such as the EU, initiatives to decentralise functions within many nation-states and the implementation of structural reforms associated with New Public Management have made the term increasingly relevant to Western democracies (Peters and Pierre Citation2001). It recognises that policy priorities are shaped and delivered both ‘downwards’ (e.g. from central to local government) and ‘upwards’ (in the opposite direction) along the vertical dimension, whilst also acknowledging that governance is an important horizontal factor across each of these tiers.

Indeed, a multi-level perspective can help to set the scene for a more holistic analysis of policy processes and implementation strategies in a variety of scenarios. For example, higher tiers of government might impose specific targets on subnational tiers, or attach strings to funding grants to try and ensure that policy objectives are achieved. Alternatively, they may provide additional resources to help local authorities achieve their objectives fairly autonomously of other horizontal actors. For their part, private actors may also exercise significant influence over decision-making – due to the subnational body being inherently weak, and/or because public officials feel that involving other stakeholders could help to achieve strategic or political objectives.

Together with Lisbet Hooghe, Marks developed the initial idea further by characterising two different types of multi-level governance: Type I, which consists of relatively static, multi-purpose jurisdictions where a single public body has direct responsibility for a range of services; and Type II, where ad hoc, task-specific organisations are more common (Hooghe and Marks Citation2003). They acknowledged that the two types normally overlap in the real world, and that most (if not all) countries are positioned somewhere along a spectrum between the two ideal models. Nonetheless, they can be useful shorthand to highlight contrasting governance arrangements in different countries, or to illustrate changes in institutional structures within a single jurisdiction. Indeed, various studies have identified a shift towards governance structures that resemble Type II arrangements – often due to the increasing fragmentation and flexibility of political institutions, and the creation of more functional agencies to undertake particular tasks (Alexander Citation1991; Herrschel and Newman Citation2002; Miller, Dickson, and Stoker Citation2000; Goldsmith Citation2012). This article will use Hooghe and Marks’ typology to illustrate some of the key concepts within the new theoretical framework it presents.

Importantly, however, the multi-level perspective does not overcome a crucial problem inherent in the governance literature: ultimately, it can only describe governance arrangements, rather than help to understand the reasons for any differences between jurisdictions – or indeed their implications for policy-making (Smith Citation2003). Indeed, as Zito (Citation2015) points out, there has never been widespread agreement on what multi-level governance is trying to explain, with the result that scholars have tended to use the term as a metaphor rather than a theoretical tool (see also Rosamond Citation2000). In particular, since the typology does not assist with analysing relationships between governing actors, it cannot identify which stakeholders are most influential in policy-making arrangements. Perhaps reflecting its genesis in political science, multi-level governance also tends to focus primarily on vertical relationships between tiers – and therefore it neglects to take sufficient account of the influence of other horizontal actors within subnational jurisdictions. The framework set out in this article incorporates both of these dimensions and thereby supports a much more comprehensive and dynamic understanding of local governance.

A number of related theoretical perspectives suffer from similar shortcomings. For example, ‘meta-governance’ perspectives (Jessop Citation2002; Kooiman Citation2003) also do not include useful tools for analysing power dynamics, which means they cannot help us to identify which actors are influencing policy-making processes. Similarly, although some scholars of policy networks stress the importance of analysing degrees of integration between actors (see e.g. Atkinson and Coleman Citation1992; Jordan and Schubert Citation1992; Marsh and Rhodes Citation1992), they focus primarily on the extent of collaboration rather than how this may influence policy-making. As Börzel (Citation1998) argues, policy analysis needs to go beyond identifying which actors are involved in networks: instead, it has to try and understand the power relationships and structures that operate within them (see also Scharpf Citation1991; Dowding Citation1995).

Rhodes (Citation1997) does acknowledge the important role of power in shaping decision-making, but he retains the idea of a ‘policy network’ and therefore suggests that all affected stakeholders remain in frequent contact with each other and develop solutions collaboratively. In fact, it is unlikely that the plethora of actors affected by a complex wicked issue could form a cohesive ‘network’ in the true sense of the word, given that they would have potentially competing objectives and cross over multiple policy sectors (Schout and Jordan Citation2005). Furthermore, the network metaphor does not take sufficient account of the difference between vertical power dependencies (in other words, those that exist between tiers of government) and horizontal relationships (the way in which subnational bodies interact with other actors within their jurisdictions). As this article will demonstrate, the former can play a crucial role in determining the latter.

Although the urban governance literature also tends to provide useful typologies and categorisations, such geographical perspectives tend to focus on horizontal relationships between different actors at the local or regional level. For example, in their exposition of different ‘modes of governing’, Bulkeley and Kern (Citation2006) propose different approaches that municipalities might adopt to achieve political objectives. Drawing on fieldwork in several cities, they suggest that subnational governments are shifting increasingly towards an ‘enabling’ mode – in that they try to facilitate and encourage other local stakeholders to help with policy implementation, rather than introduce and enforce hierarchical regulations. However, the perspective does not provide the theoretical support to understand the nature of these horizontal relationships, and therefore which actors are ultimately shaping policy. Moreover, it fails to take sufficient account of other vertical actors. This means we do not have a holistic contextual understanding – and we also lack the theoretical tools to explain differences in subnational governing arrangements between countries.

Although a number of edited books have highlighted the contrasting legal and institutional contexts within which subnational governments in developed countries operate, they have focused on creating typologies of contrasting local government systems, rather than exploring the reasons for these differences (Goldsmith and Page Citation1987; Hesse and Sharpe Citation1991; Bennett Citation1993; Norton Citation1994; Pierre Citation1999; John Citation2001; Hulst and van Montfort Citation2007). This literature categorises systems of subnational government by its legal or constitutional status, scope of responsibility, the size of individual units and degree of fiscal autonomy from the centre. Some comparative studies have taken a similar approach in order to identify how different systems influence decentralisation or centralisation initiatives (see e.g. Dickovick Citation2011). Crucially, however, these typologies have lacked a robust assessment of how subnational institutions seek to achieve their political objectives. Indeed, this omission may explain the fact that scholars have developed various typologies of subnational government, and sometimes group certain countries together that might otherwise have little in common.

The importance of capacity for local choice

Perhaps one reason for the plethora of typologies is the potential for confusion between the notion of subnational autonomy (the de jure right to take political decisions without interference from central government) and capacity (the de facto ability to achieve political objectives). This distinction is crucial for understanding the nature of subnational policy-making. For example, local authorities that ‘surrender’ some of their freedom by working closely with external actors may find that they are better placed to deliver policy goals than municipalities that remain more autonomous. Such an argument is of course not new to international relations scholars, some of whom have been using similar concepts for several decades when discussing the nature of state capacity and power in the global arena (Keohane and Nye Citation1977; Baldwin Citation1980). Nonetheless, the concept is particularly relevant in wicked sectors and/or at the subnational level, given that municipal governments are unlikely to be able to address complex policy issues independently of other actors.

More generally, the urban governance literature has shown how the desire of municipalities to seek out resources from other actors to increase their capacity is accelerating the shift away from state hierarchy and traditional ‘government’ and towards more horizontal and inclusive subnational arrangements (Stoker Citation1999; John Citation2001; Schwalb and Walk Citation2007; Waterman Citation2014). Indeed, the extent to which public bodies need to rely on external support to achieve their goals will probably shape the nature of governance relationships (see Sellers and Lidström Citation2007).

Crucially, however, scholars have not incorporated the concept of capacity into theories that could help to explain differences in governance approaches across (and potentially within) countries. Given that the capacity of subnational bodies varies from country to country, this is somewhat surprising. For example, various studies have found that ‘urban regimes’ (semi-permanent governance arrangements in which the municipality works extremely closely with societal actors (Stone Citation1989)) are much more common in the US than elsewhere in the developed world (Stoker and Mossberger Citation1994; John Citation2001; Herrschel and Newman Citation2002). A key reason for this is that local authorities in the US do not have the same level of internal capacity as those in most Western European countries. Elected representatives in weak subnational bodies of this nature are ‘policy-seeking’ rather than ‘office-seeking’ (Müller and Strøm Citation1999), and they look to private businesses to provide them with the ‘power to’ achieve their objectives. This makes them much more likely to engage and compromise with other horizontal actors than their counterparts in many European countries.

Capacity and power dependence

Therefore, the vertical context within which subnational bodies operate is likely to shape their capacity to achieve policy objectives and influence the extent to which they collaborate with external actors. With this in mind, intergovernmental relations perspectives that highlight resource interdependencies between tiers are particularly helpful. These theories have their roots in organisational sociology and the idea that a high level of interdependency between companies makes them more likely to survive economic downturns (Pfeffer and Salancik Citation1978; Aldrich Citation1979). Scholars such as Benson (Citation1982) adapted this notion for the public sector, and stressed the interdependent nature of subnational and central governments. For example, although the centre normally allocates some funding to the periphery, subnational governments usually provide relevant information and implement central policy in return. Indeed, various studies in the 1970s found that local and state governments in Germany had access to crucial sources of local information and technical expertise (Baestlein et al. Citation1978; Garlichs and Hull Citation1978; Mayntz Citation1978) that eluded the federal government. Notably, this enabled them to exercise significant influence over federal policy programmes.

Of course, the extent to which subnational actors can shape decision-making is likely to vary from country to country. It might depend on how resources are distributed within these relationships (subnational actors that can raise additional revenues easily are in a stronger position than those who have no access to extra funding), or the degree of local discretion over policy directives. Nonetheless, by focusing on such variables within interdependent relationships we can begin to identify which actors are exerting most influence over decision-making.

Indeed, Rhodes (Citation1981) adopted the idea of power dependence very effectively in the context of central–local relations in the UK. Central to his analysis was identifying the nature of the interdependent relationship, namely which resources each tier of government requires and who can provide them. These resources are not solely financial: they may also be constitutional or political, shaped by the hierarchical nature of intergovernmental relations, or associated with particular expertise or access to information. Rhodes recognised that power dependencies are rarely symmetrical, but he stressed that different tiers of government are always interdependent to some extent.

His perspective provides a useful starting point for identifying which factors may be shaping governance arrangements within any given jurisdiction. This is because any change in the availability of resources or in the importance that a stakeholder attaches to any particular resource will affect power relationships. Therefore, his framework is also dynamic and responsive to changes in intergovernmental relations that may be due to ‘soft’ political, economic or personnel developments – not just ‘hard’ legal or constitutional reforms.

Rhodes developed his framework by studying a unitary country (the UK), but it is nonetheless applicable in federal contexts – or in countries where vertical governmental bureaucracies may be underdeveloped. Municipalities probably have different resource interdependencies with provincial governments compared to federal institutions, and these relationships are likely to vary across countries – see for example Fenwick’s (Citation2016) comparison of Argentina and Brazil. Similarly, in contexts where state institutions are weak and/or public officials resort to unofficial systems of clientelism or local patronage in order to achieve their objectives, the basic principle of resource interdependence remains valid (Kühn Citation2008; Hutchcroft Citation2014). If we wish to analyse the extent to which municipalities can exercise local choice, the identity of external actors in such situations is far less important than whether subnational governments want to access the resources they possess. By estimating the sum total of resources that municipalities require from all other actors, as well as those that they provide in return, we can see how these interdependencies shape governance relationships.

Moreover, although Rhodes focused on central–local relations, his theory is equally applicable to horizontal relationships between government bodies and other actors operating within the same jurisdiction (such as quangos, voluntary organisations, private companies or clients). As with the vertical analysis, by amalgamating the support a municipality requires from all other horizontal actors, and comparing this with the resources it provides in return, we can identify the nature of power dependence within the area. At this point we can see the relevance of Stone’s (Citation1989) analysis of ‘urban regimes’, and the notion that municipalities work with other local actors to increase their ‘power to’ achieve political objectives.

Overall, therefore, the principle of resource interdependence shapes how municipalities interact with other stakeholders along both vertical and horizontal dimensions – and it can influence policy outputs accordingly. Bringing together political science and urban studies perspectives together in this way allows for a much more holistic analysis of subnational policy-making than existing theoretical approaches – and one that is not ‘fixed’ according to the de jure status of municipalities within the constitutional framework.

Although he does not address this explicitly, Rhodes implies that greater dependency is the converse of high levels of interdependency. In other words, if A is more dependent on the resources it receives from B and C than they are on the support that A provides in return, an asymmetrical relationship develops in which B and/or C can exert greater influence over A’s decision-making. However, if each organisation pursues its own objectives largely autonomously (in other words, if there is very limited reciprocity between the three actors because they already have sufficient capacity to achieve policy goals – or, alternatively, they refuse to provide additional resources to each other), they would actually be more independent of each other. In this scenario, no interdependent (or even dependent) relationship would develop. Such eventualities cannot be illustrated easily using Rhodes’ framework, but they are nonetheless perfectly possible.

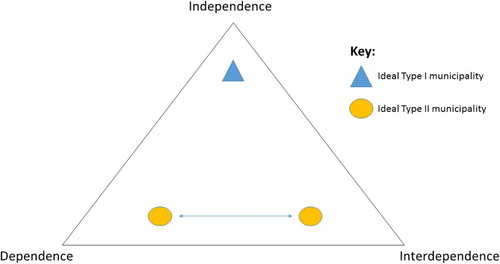

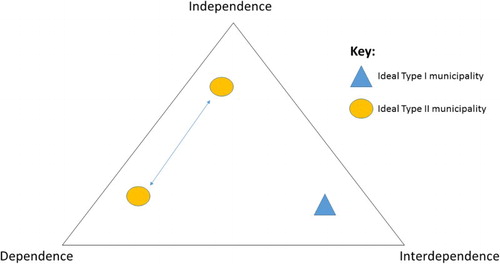

and show how any given subnational jurisdiction might be positioned according to these three poles of power dependency. They also highlight how we can apply the notion along both dimensions: in other words, map the extent to which the organisation is independent of, interdependent with or dependent on higher tiers of government and other local actors. The figures return to the characterisations of Hooghe and Marks (Citation2003) by mapping all three potential scenarios (interdependence, dependence and independence) against the ‘ideal’ Type I and Type II multi-level governance arrangements on both the vertical and horizontal dimensions. The diagrams take the subnational body’s perspective; in other words, where an organisation is located close to the dependence pole, this is because it relies more heavily on other actors than they do on it. By illustrating the type of relationships that exist both vertically and horizontally, they serve as a starting point for identifying the extent to which subnational governments have the power to achieve their political objectives.

illustrates the vertical dependency arrangements, and shows how subnational and central governments that operate in an ideal Type I jurisdiction are highly interdependent. This is because the structured institutional architecture encourages all levels to get involved in making and implementing policy – even if the legal framework may allocate specific competencies to particular tiers. Indeed, their interdependence may even reinforce the existing institutional structures, particularly if all actors along this vertical dimension believe that collaboration and pooling resources increases their capacity to achieve policy objectives. By way of contrast, since vertical Type II arrangements are flexible and dynamic, subnational bodies in these jurisdictions may operate more independently of higher tiers of government – or they could be asymmetrically dependent on resources from the centre. In other words, highlights some of the shortcomings of Hooghe and Marks’ typology, whilst nonetheless illustrating how their ideal models sit some distance away from each other along the vertical dimension.

Figure 1. Vertical power dependency relationships in Types I and II multi-level governance arrangements.

In a similar way, shows where ideal Type I and Type II municipalities would be located along the horizontal dimension. Since Type I arrangements suggest that responsibilities are concentrated into ‘multi-purpose’ jurisdictions, these bodies have responsibility for a wide range of functions and do not have to rely on other agencies to achieve their objectives. As such, they can operate largely autonomously of other horizontal actors and are positioned close to the independence pole. In contrast, subnational governments in Type II jurisdictions rely heavily on ‘task-specific’ bodies (such as special-purpose vehicles, external contractors and ‘depoliticised’ arms-length agencies) to achieve their objectives. This relationship may be interdependent, because the subnational body might provide democratic legitimacy, funding or other resources in return. Alternatively, it could be more dependent, if non-state actors do not need to rely very heavily on the public institution for resources – because, for example, they can find them elsewhere or manage without them. As such, Type II jurisdictions are positioned towards one of these two poles along the horizontal dimension.

Theoretical and practical implications of the framework

These diagrams illustrate how Hooghe and Marks’ typologies of multi-level governance interlock with and can be augmented by Rhodes’ theory of power dependence. More importantly, however, they can also help to examine power relationships within governance arrangements by highlighting the nature of resource dependencies between actors, along both the vertical and horizontal dimensions. This makes them useful tools for analysing policy-making approaches in multi-level and potentially dynamic contexts. In particular, by examining the nature of those resources that a jurisdiction exchanges in order to increase its capacity to achieve policy objectives, we can begin to understand which actors are likely to be more influential in decision-making processes.

Furthermore, we can propose that vertical power dependencies play a crucial role in influencing horizontal relationships and policy-making processes, particularly in sectors that require complex responses or specific expertise. For example, if a subnational organisation does not receive support from central government to help with policy formulation and implementation, it may lack the internal capacity to achieve its objectives autonomously. As a result, it will need to work more interdependently with (or it may even depend on) other horizontal actors in order to deliver its policy goals. Furthermore, its relatively weak position vis à vis other local stakeholders will probably result in a consensual policy style that is more open to compromise, since it will need to rely on external support. This consensual approach could mean that other horizontal actors are able to exercise significant influence in policy-making processes.

By way of contrast, if different tiers of government seek to increase their capacity by pooling resources and becoming more interdependent along the vertical dimension, this is much more likely to help subnational governments operate independently of other horizontal stakeholders (that is, if they choose to do so). Such a scenario would also enable the public body to act more hierarchically within its jurisdiction, since it would not require many external resources to achieve its policy objectives and therefore would not need to compromise with other local actors.

To complete the picture, we might also expect a subnational body that is highly dependent on vertical actors to operate more independently and hierarchically along the horizontal dimension. This is because it will not lack the capacity to achieve its policy objectives, and therefore does not need to rely heavily on other local stakeholders. Crucially, however, central government would be in a strong position to exert significant influence over subnational policy-making, since it would be providing most of the resources to help with implementation and therefore might link funding streams to the delivery of ministerial objectives, for example.

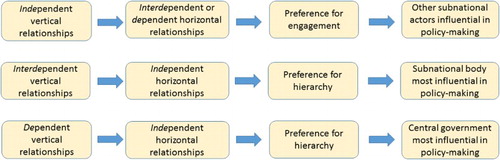

sets out this characterisation as a hypothesis for further empirical investigation. This could involve comparative study, in order to investigate whether more interdependent vertical relationships do indeed result in subnational governments exercising greater influence over policy-making within their jurisdictions. For example, we might expect subnational governments in countries such as Germany, with its culture of interdependent cooperative federalism (or Politikverflechtung, see Scharpf, Reissert, and Schnabel Citation1976), to be able to take decisions largely independently of other local stakeholders. By way of contrast, subnational bodies that operate more independently of the centre in a ‘dual polity’ such as the UK (Bulpitt Citation1983; Atkinson and Wilks-Heeg Citation2000) may need to rely much more on other horizontal actors in policy-making processes. The boxes on the far right-hand side of the diagram also have a number of normative implications, since they suggest that more dependent and independent vertical relationships reduce the ability of subnational governments to exercise local choice. This raises questions of ‘depoliticisation’ and democratic accountability – issues that are already at the centre of many critiques of New Public Management (Eckersley, Ferry, and Zakaria Citation2014) and governance (Palumbo Citation2015), as well as the shift towards political institutions seeking legitimacy based on their ‘outputs’ rather than just their ‘inputs’ (Scharpf Citation1999).

Figure 3. How vertical power dependencies might shape horizontal policy-making and local choice: A hypothesis for investigation.

also highlights the role of vertical relationships in shaping subnational decision-making. This is because subnational governments can only exert very limited influence over the vertical context within which they operate, whereas they tend to have significantly more freedom to determine their horizontal relationships. Crucially, if municipalities are unable to access the resources they require from other vertical actors, they will need to seek out this support horizontally – a situation that is likely to weaken their influence over policy-making and therefore increase the pace of depoliticisation. In other words, central governments exercise significant influence over subnational policy-making arrangements, because ministers need to initiate (or at least agree to) changes in vertical power dependencies.

As this article has demonstrated, however, it is important to note that ministers do not influence subnational governance solely by restricting or increasing the degree of local autonomy. A more important (and neglected) factor is the extent to which they work interdependently with subnational governments in order to give them enough capacity to achieve local political objectives. Vertical collaboration of this nature is perhaps even more crucial in those countries that have weakened state institutions significantly in recent decades – or where public bureaucracies are underdeveloped – because these conditions enable market actors to exert greater influence within horizontal governance arrangements.

By extension, any proposal to devolve more powers to subnational governments is unlikely to make much difference to local decision-making unless these bodies are (also) provided with sufficient support and capacity to achieve their political objectives. In other words, the rhetoric of ‘localism’ has failed to take account of organisational capacity and the crucial role that vertical interdependence plays in allowing subnational organisations to make and implement policy independently within their jurisdictions. Instead, localism has focused on increasing the degree of independence between tiers of government – a scenario that may well reduce the capacity of subnational bodies and mean that they become more dependent on other horizontal actors in policy-making processes. Indeed, as Evans, Marsh, and Stoker (Citation2013, 403) point out in the UK context, it has resulted in a situation ‘in which responsibilities, rather than power or resources, [are] devolved’. Paradoxically, it may actually reduce the ability of subnational governments to exercise local choice and shape decision-making within their jurisdictions, because they will need to rely more on other horizontal actors to achieve their objectives. This is particularly the case in those sectors that require a coordinated response from various stakeholders and/or specific expertise that may not exist within a single organisation.

Conclusions

This article has expanded on Rhodes' (Citation1981) theory of power dependence in central–local government relations to set out a more comprehensive and dynamic framework for analysing policy-making at the subnational level. In particular, it has combined Rhodes’ concept with Stone’s (Citation1989) notion of ‘urban regimes’ to develop a dynamic and bi-directional framework for analysing local governance. By applying Rhodes’ principle of power dependence along both the vertical and horizontal dimensions, this tool can provide a more holistic understanding of subnational policy-making arrangements than existing multi-level governance and urban studies perspectives.

The framework also stresses the important role that vertical resource dependencies play in determining how a subnational government operates within its jurisdiction. It suggests that if a subnational body is able to access sufficient resources from higher tiers of government to achieve its policy objectives, it will be better placed to adopt a hierarchical and independent position in local governance arrangements. However, if this necessary support is not forthcoming along the vertical dimension, it will need to work more interdependently with (or even depend on) other horizontal actors to increase its capacity. This would mean that it loses some influence over decision-making. In this way, a subnational government’s level of capacity, and the extent to which it receives support from higher tiers of government, can shape its relationships with other local actors – and ultimately influence policy outputs.

Initially, this framework was developed to support an empirical study that compared local policy-making arrangements in two countries that have contrasting intergovernmental structures. However, it has wider applicability in other contexts, and further studies may wish to test the hypotheses set out in . The framework also raises a number of normative concerns about the nature of local democracy and the extent to which subnational governments are becoming depoliticised – issues that scholars in the field of applied political theory may wish to consider. Finally, politicians and officials within subnational bodies may wish to ponder the likely implications of greater autonomy (or ‘localism’) from higher tiers of government. In particular, the perceived Holy Grail of greater vertical independence might prove to be a poisoned chalice if it reduces municipalities’ capacity to achieve policy objectives and therefore makes them more dependent on other horizontal actors in governance arrangements. Such a scenario could actually reduce the ability of subnational bodies to shape policy-making within their jurisdictions.

Notes on contributor

Peter Eckersley is a Research Associate at Newcastle University Business School with interests in local governance, comparative public policy, intergovernmental relations, accountability and sustainability. His PhD in political science compared climate change policy-making processes in English and German cities.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflict of interests.

ORCID

Peter Eckersley http://orcid.org/0000-0001-9048-8529

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aldrich, Howard E. 1979. Organisations and Environments. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Alexander, Alan. 1991. “Managing Fragmentation: Democracy, Accountability and the Future of Local Government.” Local Government Studies 17 (6): 63–76. doi: 10.1080/03003939108433606

- Atkinson, Michael M., and William D. Coleman. 1992. “Policy Networks, Policy Communities and the Problems of Governance.” Governance 5 (2): 154–180. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0491.1992.tb00034.x

- Atkinson, Hugh, and Stuart Wilks-Heeg. 2000. Local Government from Thatcher to Blair: The Politics of Creative Autonomy. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Baestlein, Angela, Gerhard Hunnius, Werner Jann, Manfred Konukiewitz, and Helmut Wollmann. 1978. “State Grants and Local Development Planning in the Federal Republic of Germany.” In Interorganisational Policy Making: Limits to Coordination and Central Control, edited by Kenneth Hanf and Fritz W. Scharpf, 115–142. London: Sage.

- Baldwin, David A. 1980. “Interdependence and Power: A Conceptual Analysis.” International Organization 34 (4): 471–506. doi: 10.1017/S0020818300018828

- Bennett, Robert J., ed. 1993. Local Government in the New Europe. London: Belhaven Press.

- Benson, J. Kenneth. 1982. “A Framework for Policy Analysis.” In Interorganisational Coordination: Theory, Research and Implementation, edited by David L. Rogers and David A. Whetten, 137–176. Ames: Iowa State University Press.

- Börzel, Tanja A. 1998. “Organizing Babylon: On the Different Conceptions of Policy Networks.” Public Administration 72 (2): 252–273.

- Bulkeley, Harriet, and Michelle M. Betsill. 2005. “Rethinking Sustainable Cities: Multilevel Governance and the ‘Urban’ Politics of Climate Change.” Environmental Politics 14 (1): 42–63. doi: 10.1080/0964401042000310178

- Bulkeley, Harriet, and Kristine Kern. 2006. “Local Government and the Governing of Climate Change in Germany and the UK.” Urban Studies 43 (12): 2237–2259. doi: 10.1080/00420980600936491

- Bulpitt, James G. 1983. Territory and Power in the United Kingdom. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Crouch, Colin. 2004. Post-democracy. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Dickovick, J. Tyler. 2011. Decentralization and Recentralization in the Developing World: Comparative Studies from Africa and Latin America. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press.

- Dowding, Keith. 1995. “Model or Metaphor? A Critical Review of the Policy Network Approach.” Political Studies 43 (1): 136–158. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9248.1995.tb01705.x

- Eckersley, Peter, Laurence Ferry, and Zamzulaila Zakaria. 2014. “A ‘Panoptical’ or ‘Synoptical’ Approach to Monitoring Performance? Local Public Services in England and the Widening Accountability Gap.” Critical Perspectives on Accounting 25 (6): 529–538. doi: 10.1016/j.cpa.2013.03.003

- Evans, Mark, David Marsh, and Gerry Stoker. 2013. “Understanding Localism.” Policy Studies 34 (4): 401–407. doi: 10.1080/01442872.2013.822699

- Fenwick, Tracy B. 2016. Avoiding Governors: Federalism, Democracy, and Poverty Alleviation in Brazil and Argentina. Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press.

- Flinders, Matthew, and Wood, Matt. 2014. “Depoliticisation, Governance and the State.” Policy and Politics 42 (2): 135–149. doi: 10.1332/030557312X655873

- Garlichs, Dietrich, and Chris Hull. 1978. “Central Control and Information Dependence: Highway Planning in the Federal Republic of Germany.” In Interorganisational Policy Making: Limits to Coordination and Central Control, edited by Kenneth Hanf and Fritz W. Scharpf, 143–166. London: Sage.

- Geddes, Mike. 2005. “Neoliberalism and Local Governance: Cross-national Perspectives and Speculations.” Policy Studies 26 (3–4): 359–377. doi: 10.1080/01442870500198429

- Goldsmith, Mike. 2012. “Cities in Intergovernmental Systems.” In The Oxford Handbook of Urban Politics, edited by Karen Mossberger, Susan E. Clarke, and Peter John, 133–151. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Goldsmith, Mike, and Edward Page, eds. 1987. Central and Local Government Relations. London: Sage.

- Heinelt, Hubert. 2002. “Achieving Sustainable and Innovative Policies Through Participatory Governance in a Multi-level Context: Theoretical Issues.” In Participatory Governance in a Multi-level Context: Concepts and Experience, edited by Hubert Heinelt, Panagiotis Getimis, Grigoris Kafkalas, Randall Smith, and Erik Swyngedouw, 17–32. Opladen: Leske & Budrich.

- Herrschel, Tassilo, and Peter Newman. 2002. Governance of Europe’s City Regions: Planning, Policy & Politics. London: Routledge.

- Hesse, Joachim J., and Laurence J. Sharpe, eds. 1991. Local Government and Urban Affairs in International Perspective. Baden-Baden: Nomos.

- Hill, Michael, and Peter Hupe. 2002. Implementing Public Policy: Governance in Theory and in Practice. London: Sage.

- Hooghe, Lisbet, and Gary Marks. 2003. “Unraveling the Central State, But How? Types of Multi-level Governance.” American Political Science Review 97 (2): 233–243.

- Hulst, Rudie, and Andre van Montfort. 2007. Inter-municipal Cooperation in Europe. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Hutchcroft, Paul D. 2014. “Linking Capital and Countryside: Patronage and Clientelism in Japan, Thailand and the Philippines.” In Clientelism, Social Policy and the Quality of Democracy, edited by Diego A. Brun and Larry Diamond, 174–203. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Jessop, Bob. 2002. “Governance and Meta-governance: On Reflexivity, Requisite Variety and Requisite Irony.” In Participatory Governance in a Multi-level Context: Concepts and Experience, edited by Hubert Heinelt, Panagiotis Getimis, Grigoris Kafkalas, Randall Smith, and Erik Swyngedouw, 33–58. Opladen: Leske & Budrich.

- John, Peter. 2001. Local Governance in Western Europe. London: Sage.

- Jordan, A. Grant, and Klaus Schubert. 1992. “A Preliminary Ordering of Policy Network Labels.” European Journal of Political Research 21 (1–2): 7–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6765.1992.tb00286.x

- Keohane, Robert O., and Joseph S. Nye. 1977. Power and Interdependence: World Politics in Transition. Boston: Little, Brown and Company.

- Kooiman, Jan. 2003. Governing as Governance. London: Sage.

- Kühn, Florian P. 2008. “Aid, Opium, and the State of Rents in Afghanistan: Competition, Cooperation, or Cohabitation?” Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding 2 (3): 309–327. doi: 10.1080/17502970802436338

- Lowndes, Vivien, and Chris Skelcher. 1998. “The Dynamics of Multi-organisational Partnerships: An Analysis of Changing Modes of Governance.” Public Administration 76 (2): 313–333. doi: 10.1111/1467-9299.00103

- Marks, Gary. 1993. “Structural Policy and Multi-level Governance in the EC.” In The State of the European Community, edited by Alan W. Cafruny and Glenda G. Rosenthal, 391–410. Harlow: Longman.

- Marsh, David, and Rod A. W. Rhodes. 1992. “Policy Communities and Issue Networks: Beyond Typology.” In Policy Networks in British Government, edited by David Marsh and Rod A. W. Rhodes, 249–268. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Mayntz, Renate. 1978. “Intergovernmental Implementation of Environmental Policy.” In Interorganisational Policy Making: Limits to Coordination and Central Control, edited by Kenneth Hanf and Fritz W. Scharpf, 201–214. London: Sage.

- Mayntz, Renate. 2010. “Governance im modernen Staat [Governance in the Modern State].” In Governance – Regieren in komplexen Regelsystemen [Governance – Governing in Complex Systems of Control], edited by Arthur Benz and Nicolai Dose, 65–76. Wiesbaden: Springer.

- Miller, William L., Malcolm Dickson, and Gerry Stoker. 2000. Models of Local Governance: Public Opinion and Political Theory in Britain. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

- Müller, Wolfgang C., and Kaare Strøm, eds. 1999. Policy, Office, or Votes? How Political Parties in Western Europe Make Hard Decisions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Norton, Alan. 1994. International Handbook of Local and Regional Government: A Comparative Analysis of Advanced Democracies. Aldershot: Edward Elgar.

- Ostrom, Elinor. 1990. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Palumbo, Antonio. 2015. Situating Governance: Context, Content, Critique. London: ECPR Press.

- Peters, B. Guy, and Jon Pierre. 2001. “Developments in Intergovernmental Relations: Towards Multi-level Governance.” Policy & Politics 29 (2): 131–135. doi: 10.1332/0305573012501251

- Pfeffer, Jeffrey, and Gerald R. Salancik. 1978. The External Control of Organizations: A Resource Dependence Perspective. New York: Harper and Row.

- Pierre, Jon. 1999. “Models of Urban Governance: The Institutional Dimension of Urban Politics.” Urban Affairs Review 34 (3): 372–396. doi: 10.1177/10780879922183988

- Pierre, Jon, and B. Guy Peters. 2012. “Urban Governance.” In The Oxford Handbook of Urban Politics, edited by Karen Mossberger, Susan E. Clarke, and Peter John, 71–86. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Putnam, Robert D., Robert Leonardi, and Rafaella Y. Nonetti. 1993. Making Democracy Work: Civic Traditions in Modern Italy. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Rhodes, Rod A. W. 1981. Control and Power in Central-local Relations. Westmead: Gower.

- Rhodes, Rod A. W. 1997. Understanding Governance: Policy Networks, Governance, Reflexivity and Accountability. Bristol: Open University Press.

- Rittel, Horst W. J., and Melvin M. Webber. 1973. “Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning.” Policy Sciences 4 (1): 155–169. doi: 10.1007/BF01405730

- Rosamond, Ben. 2000. Theories of European Integration. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

- Savitch, Hank V., and Paul Kantor. 2002. Cities in the International Marketplace: The Political Economy of Urban Development in North America and Western Europe. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Scharpf, Fritz W. 1991. “Political Institutions, Decision Styles, and Policy Choices.” In Political Choice: Institutions, Rules and the Limits of Rationality, edited by Roland M. Czada and Adrienne Windhoff-Héritier, 53–86. Frankfurt: Campus.

- Scharpf, Fritz W. 1999. Governing in Europe: Effective and Democratic? Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Scharpf, Fritz W., Bernd Reissert, and Fritz Schnabel, eds. 1976. Politikverflechtung: Theorie und Empirie des kooperativen Föderalismus in der Bundesrepublik [Political Integration: Theory and Practice of Cooperative Federalism in West Germany]. Kronberg: Scriptor.

- Schout, Adriaan, and Andrew Jordan. 2005. “Co-ordinated European Governance: Self-organizing or Centrally-steered?” Public Administration 83 (1): 201–220. doi: 10.1111/j.0033-3298.2005.00444.x

- Schwalb, Lilian, and Heike Walk, eds. 2007. Local Governance – mehr Transparenz und Bürgernähe? [Local Governance – More Transparent and Closer to Citizens?]. Wiesbaden: Springer.

- Sellers, Jeffrey M., and Anders Lidström. 2007. “Decentralisation, Local Government, and the Welfare State.” Governance 20 (4): 609–632. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0491.2007.00374.x

- Smith, Andy. 2003. “Multi-level Governance: What It Is and How It Can Be Studied.” In Handbook of Public Administration, edited by B. Guy Peters and Jon Pierre, 377–386. London: Sage.

- Stoker, Gerry, ed. 1999. The New Management of British Local Governance. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Stoker, Gerry. 2003. Transforming Local Governance: From Thatcherism to New Labour. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Stoker, Gerry, and Karen Mossberger. 1994. “Urban Regime Theory in Comparative Perspective.” Environment and Planning C 12 (2): 195–212. doi: 10.1068/c120195

- Stone, Clarence N. 1989. Regime Politics: Governing Atlanta, 1946–1988. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas.

- Waterman, Chris. 2014. “Local Government and Local Governance: 1944–2011.” Local Government Studies 40 (6): 938–953. doi: 10.1080/03003930.2012.719101

- Weber, Edward P., and Anne M. Khademian. 2008. “Wicked Problems, Knowledge Challenges, and Collaborative Capacity Builders in Network Settings.” Public Administration Review 68 (2): 334–349. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6210.2007.00866.x

- Zito, Anthony R. 2015. “Multi-level Governance, EU Public Policy and the Evasive Dependent Variable.” In Multi-level Governance: The Missing Linkages, edited by Edoardo Ongaro, 15–39. Bingley: Emerald.