ABSTRACT

Scholars in political science and policy studies have been paying increasing attention to a specific kind of actor, the policy entrepreneur, as an agent of change. Less attention has been paid to the contextual factors that may shape entrepreneurial action as most of the extant research is performed in pluralistic systems and in high complexity policy sectors. This is a study of a routine planning process in the municipality of Östersund in Northern Sweden with the purpose of studying the kind of actors that may act entrepreneurially (the who); the kind of strategies they use; and what contextual powers facilitate these strategies (the how). This two-and-a-half-year routine, low-complexity process was analyzed with in-depth interviews and a survey, participant observation, document analysis, and formal social network analysis. Findings suggest that professional administrators acted entrepreneurially by employing a set of six strategies while the members of civil society were central – though not entrepreneurial – participants.

Introduction

The complexity of the public policy process is evidenced in the multitude of institutions and actors it involves and the nature of societal problems public policies seek to solve. In order to understand public policies, scholars employ not an insignificant number of frameworks, theories, and models, which tend to be complementary rather than competing in terms of explanatory value; while they all offer some explanation of policy outcomes, they also have weaknesses (Peters Citation2015; Peters and Pierre Citation2006). Recent developments in policy process theories evince a synthesizing trend; what is more, older theories become the springboard for new ones (Petridou Citation2014). Peters (Citation2015) notes that most theoretical approaches downplay the role of agency and a way to address this shortfall is to further theorize the role of the policy entrepreneur.

Policy entrepreneurs are ‘political actors who seek policy changes that shift the status quo in given areas of public policy’ (Mintrom Citation2015, 103); they are people who ‘seek to realize a particular vision of how society should work’ (Windrum Citation2008, 236). The concept of policy entrepreneurship has gained traction over the past three decades (Ackrill and Kay Citation2011; Kingdon Citation1984/Citation2003; Mintrom Citation2000, Citation2013, Citation2015; Mintrom and Norman Citation2009; Mintrom and Vergari Citation1996; Petridou, Narbutaité Aflaki, and Miles Citation2015; Schneider, Teske, and Mintrom Citation1995; Sheingate Citation2003). In a recent review, Petridou (Citation2014) shows the evolution of the policy entrepreneur(ship) (PE) toward a meso-level framework to understand public policies. A broad interpretation of the definition of public policy – and one adopted in this paper – includes not only formal laws and regulations, but also the output produced by the interaction of governmental and non-governmental actors, as well as the output of groups and associations charged with the provision and production of public goods (Theodoulou and Cahn Citation1995; Weible Citation2014).

The policy entrepreneurship framework has been used to explore complex policy contexts involving many levels of governance and divergent interests (see, for example, Carter and Scott Citation2009; Christopoulos and Ingold Citation2011; David Citation2015; Ingold and Christopoulos Citation2015; Kingdon Citation1984/Citation2003; Meydani Citation2009; Mintrom Citation2000); environmental policies (Huitema and Meijerink Citation2010; Meijerink and Huitema Citation2010; Verduijn Citation2015); urban growth and economic development (Mintrom, Salisbury, and Luetjens Citation2014; Schneider, Teske, and Mintrom Citation1995); and recently ‘morally’ controversial issues such as stem cell research (Mintrom Citation2013, Citation2015). Thus, policy entrepreneurship has been examined by-and-large in pluralistic systems conducive to competition, conflict, and in controversial, high visibility policy sectors with more-or-less delineated winners and losers.

By contrast, this study analyzes the routine planning process that resulted in the drafting of the community development vision plan at a Swedish municipality. Change in this paper is defined as the drafting of the community vision plan for the municipality of Östersund in terms of output as well as process. In line with Mackenzie (Citation2004), the theoretical objective of this paper is to investigate how the theoretical constructs of policy entrepreneurship and the policy entrepreneur, designed and developed elsewhere, might travel in other contexts. This has theoretical and practical implications. Exploring and possibly reformulating the concept of the policy entrepreneur and the theoretical relationships in the policy entrepreneurship framework by examining it in an under-researched context contributes to the theorization of agency, which, by reducing the degree of randomness, can add leverage to a theoretical framework (Peters Citation2015). What is more, Mintrom and Norman (Citation2009) call for the application of the policy entrepreneurship framework in diverse contexts in order to conceptually enhance its constituent parts and the relationships among them. At the same time and from a practitioner’s perspective, understanding agency can broaden the toolbox of policy-makers; at the local level in routine planning processes, the application of the policy entrepreneurship framework in Sweden can have an impact on the provision of public goods and services.

More specifically then, this study focuses on the contingencies of entrepreneurial capacity in relation to the formal position and the institutional context of the actors – that is, the who of the policy entrepreneur – as well as the strategies they use – that is, the how (Petridou, Narbutaité Aflaki, and Miles Citation2015). Policy entrepreneurs, as part of the Multiple Streams Approach (MSA), emerged in conditions of ambiguity, crisis, and conflict (Kingdon Citation1984/Citation2003; Zahariadis Citation2007, Citation2014). Following Mintrom and Norman (Citation2009), who called for the research of policy entrepreneurship in diverse contexts, and in dialogue, for example, with work such as the recent piece by Zahariadis and Exadaktylos (Citation2016), who examined policy entrepreneurs in conditions of ambiguity, crisis, and conflict, this research seeks to understand how might policy entrepreneurs use strategies during unambiguous, routine planning processes, in a low-conflict, consensual, collective decision-making system. As Zahariadis and Exadaktylos (Citation2016) state, ‘[w]hile entrepreneurs have the capacity to choose behavior, explanations of policy outcomes cannot be devoid of the context (institutions, roles, and resources) that regulates social interaction. Agency and context, therefore, should not be viewed in isolation but as linked through strategy’ (62). If policy entrepreneurs do emerge in the Swedish, routine planning context, what kind of political actors are they and what kind of strategies do they use in their effort to affect change?

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: first, I outline the background of the case study and elaborate on the theoretical tenets underpinning this research. I continue with an explanation of the methodology and data, followed by an analysis of the results and a section discussing the main findings. The article is wrapped up with short concluding remarks.

Planning in the Swedish context and the strategies of policy entrepreneurs

The rational paradigm prominent in planning in the 1960s was challenged by advocacy planning and a pluralistic approach (Davidoff Citation1965/Citation2012; Ioannides Citation2015), which was followed by what is termed collaborative or communicative planning (Forester Citation1989, Citation2008/Citation2012; Smedby and Neij Citation2013). Citizen participation in the planning process views the planner as a facilitator, while the output is a set of strategies defined by goals set by the participation group. The eternal challenge these processes face is to actually get citizens to participate (Alterman, Harris, and Hill Citation1984; Forester Citation2008/Citation2012).

In general terms, public administration in Sweden is characterized by strong state governing combined with considerable independence of local governments and national agencies. These have had for some time extensive decision-making powers and public officials generally enjoy high levels of autonomy, while major disagreement among the political parties as well as the major interest groups is uncommon (Hall Citation2013; Olsson and Hysing Citation2012; Wollman and Thurmaier Citation2012). The Scandinavian corporatist system, in general, implies that while the state is the central actor, the decision-making process involves a number of actors and stakeholders (Pierre and Peters Citation2005). In contrast to pluralist concepts, which stress the breadth of actors and the ensuing competition among them, corporatist concepts emphasize the cooperation among few and central actors (Adam and Kriesi Citation2007). At the local level, corporatist governance features the considerable involvement of civil society organizations in politics and public service delivery (Pierre Citation2011).

In planning matters, in particular, the local level (municipality) has competence – the ‘planning monopoly’ – according to the 1987 Plan and Bygglag, PBL (Planning and Building Law) (Montin Citation2016). PBL also stipulates that every municipality have a general vision plan (Granberg Citation2004). The municipality as an administrative unit became as important, as the central government in matters relating to economic development especially after the ascension of Sweden to the EU in 1995 (Pierre Citation2009). The law aimed at replacing control by the central government with increased citizen input on municipal matters. PBL was flexible as to what the planning process would look like, especially in terms of citizen participation, but the results were mixed (Granberg Citation2004). Even though citizen participation got attention in the PBL, an interactive form of planning is not the dominant paradigm in Sweden. The municipality has to notify the public about a planned action by a posting on the municipal notice board and/or by an announcement in the press, but no other input is formally required. Many municipalities use their websites as a means of communication as well (Nyström and Tonell Citation2012). Conversely, there is an intense interaction between professional administrators and politicians during planning processes. Very few planners would propose anything that has not been accepted by leading elected officials: ‘politicians influence professional administrators who in turn influence politicians’ (Bengtsson quoted in Montin Citation2016).

In comparison with the quote above and the frontloaded interactive process between professional administrators and politicians, citizen participation in the planning process translates to collecting comments from different (organized) interests after the municipality has decided on the contents of a vision plan. Though the final decision to initiate and approve a vision plan rests with the city council – thus ensuring citizen input through representative democracy – it is most often public officials with specialized knowledge who are tasked to implement the planning process. In some small municipalities, the task may be assigned to a consultant (Nyström and Tonell Citation2012). A notable exception to this practice was Det Goda Samtalet (The Constructive Dialogue). This was a collaborative planning experiment, part of a larger program between 2004 and 2009, aimed at a more sustainable built environment by 2025 (Smedby and Neij Citation2013). In this context, citizens were co-producers of policy, formulated in a series of dialogues among various stakeholders for a sustainable urban development (Montin Citation2016; Smedby and Neij Citation2013). This is an example of a networked governance arrangement, where even though governments are still in the business of governing, they do so within non-hierarchical forms of governance structures, including networks consisting of public, private, and quasi-public actors (Bogason Citation2000; Capano, Rayner, and Zito Citation2012; Pierre Citation2000; Pike, Rodríguez- Pose, and Tomaney Citation2006; Rhodes Citation1997, Citation2000).

Hysing and Olsson (Citation2012) outline five ways in which Swedish professional administrators have power. First, they have the power of initiative. They are usually experts in the area in which they work, with intimate knowledge of the policy sector and the political landscape surrounding it, allowing them to seize opportunities for change. Second, they have the power of the pen because they write and formulate the text which is sent to the elected officials for consideration. Third, they have the power of prioritization in the sense that they can push issues horizontally or upwards to the attention of elected officials. Fourth, professional administrators have the power of implementation, which is a complicated process that can significantly transform the original policy decision (Hysing and Olsson Citation2012; Lipsky Citation1980/Citation2010; Pressman and Wildavsky Citation1984). Finally, professional administrators have the power of evaluation. By developing criteria for the evaluation of policies and programs, they steer, to a certain extent, the attention of future political actions (Hysing and Olsson Citation2012; see also Hysing and Olsson Citation2011; Olsson and Hysing Citation2012).

The agentic salience of professional administrators and other actors has also been documented elsewhere in the literature in the context of local and regional planning processes. At the same time, entrepreneurial actors may be professional administrators, elected officials, interested citizens, or members of interest groups (Petridou, Narbutaité Aflaki, and Miles Citation2015). As defined earlier in this paper, an entrepreneur in the polis is essentially an actor,

embedded in the sociopolitical fabric, who is alert to the emergence of opportunities and acts upon them; he or she amasses coalitions for the purpose of effecting change in a substantive policy sector, political rules, or in the provision of public goods. (Petridou, Narbutaité Aflaki, and Miles Citation2015, 1)

I argue that a different context may alter not only the outcome of a given strategy, but also the way a strategy plays out, whether it is used at all, as well as affect the very emergence of actors that would use the strategy in the first place. Such entrepreneurial strategies have been theorized extensively by scholars (such as Böcher Citation2015; Brouwer and Biermann Citation2011; Huitema and Meijerink Citation2010; Klein Woolthuis et al. Citation2013; Meijerink and Huitema Citation2010; Schneider, Teske, and Mintrom Citation1995; Verduijn Citation2015) in the context of complex local planning, urban governance processes involving resistance, articulated conflict, wicked problems, and diverse interests vying for scarce resources.

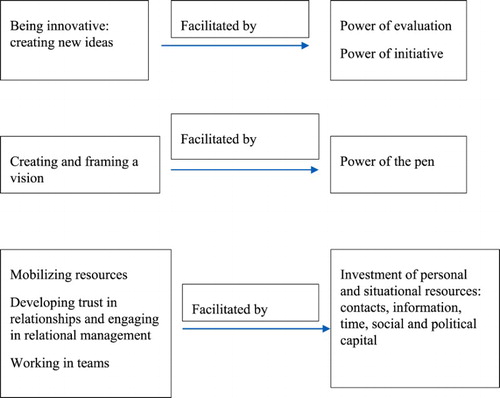

These strategies can be synthesized in the following categories: First, entrepreneurs create and frame a vision and provide leadership. They are actors who actively promote a well-articulated idea. Second, entrepreneurs are innovating in the sense that they create new ideas, even if these are a synthesis of existing concepts. Third, they have to be able to sell these ideas, perhaps through different forms of lobbying. Fourth, entrepreneurial actors are able to collaborate and merge divergent interests, engaging in arbitrage. Fifth, entrepreneurs are able to build coalitions and may tap on their own resources, such as political expertise, to do this. Sixth, they are able to develop trust in relationships and must be able to engage in relational management. Seventh, entrepreneurs may engage in venue manipulation. Eighth, they form and operate in, entrepreneurial teams, and finally, they mobilize resources: monetary, social, or information (Böcher Citation2015; Brouwer and Biermann Citation2011; Huitema and Meijerink Citation2010; Klein Woolthuis et al. Citation2013; Mintrom Citation2000; Mintrom, Salisbury, and Luetjens Citation2014; Schneider, Teske, and Mintrom Citation1995; Verduijn Citation2015). A synthesis of the literature regarding these strategies and the contextual power of actors informing them is presented in .

Table 1. Entrepreneurial strategies and actors’ powers at the local level: a synthesis of the literature.

I seek to leverage the theoretical framework of policy entrepreneurship in terms of the who and the how by applying these strategies in the hitherto under-researched context of routine planning processes.

Method and data

The Östersund case study is treated here as an influential case (Eckstein Citation1992; Gerring Citation2008). This single case design logic casts doubt upon a theory and provides the rationale for a closer inspection. Thus, the interrogation of one Swedish municipality becomes theoretically relevant as it may provide the impetus for a further reconceptualization of the theory or framework (Gerring Citation2008), which has been a theoretical ambition of this paper.

The community vision plan drafting process spanned from the summer of 2013 until December 2015. A brief timeline is as follows: In the summer of 2013, a set of 19 possible development factors are devised and designed. In October 2013, a large plenary meeting ranked these and seven factors were decided upon to be the ones on which the vision plan would center. The city council voted on these in March 2014. A reference group meeting was called in June 2014 to kick-start the seven workshops (one for each factor) that followed. The last one was held in March 2015.

At the onset, the municipal unit responsible for community development (henceforth called Tillxväxt Östersund) assigned a group of international design students to devise and design a set of possible community development factors; two-and-a-half years later, the process ended with the launching of a detailed action program titled More [*] Östersund: Strategic investments for increased development Footnote1 after being voted by the city council (Östersunds Kommun Citationn.d. a). The unit consisted of four professional administrators, one of which was the director. The data collected during these two-and-a-half years included: interviews, informal communication and meetings with the professional administrators and several participants; document analysis (reports, web pages, emails, Prezi, and PowerPoint presentations); participant observations in meetings and workshops; an internet survey to all the participants, and finally a relational survey for the participants of one workshop.

I attended all nine meetings and workshops that this participatory process entailed. These meetings also provided the forum for informal, unstructured interviews with participants, for the purpose of ‘ … [capturing] the perceptions of respondents “from the inside”’(Idler, Hudson, and Leventhal Citation1999, 458; Miles and Huberman Citation1994). Four formal interviews with the professional administrators were recorded and transcribed. They were semi-structured interviews lasting an average of 60 minutes at their place of work. I took notes during all the informal meetings and workshops; one workshop was recorded in its entirety. All the material was thematically analyzed to tease out possible entrepreneurial strategies and the contextual powers informing them.

In an effort to pluralize the method(s) used in this research (Peters, Pierre, and Stoker Citation2010) and in order to shore up the analytical salience of the interviews and participant observations, I also sent an internet survey to 109 of the 127 workshop participants,Footnote2 first in June 2015, with a second mailing in September 2015. Additionally and more to the point, early observations pointed to the importance of the personal and professional relationships among the participant actors who became co-producers of policy through their input in this networked process. The flat(ter) architecture of such structures notwithstanding, (policy) networks imply an uneven distribution of power among actors based on their structural position; recent researched has focused on networks for the theorization of policy entrepreneurs (Adam and Kriesi Citation2007; Borgatti, Everett, and Johnson Citation2013; Christopoulos Citation2006, Citation2008; Ingold and Christopoulos Citation2015; Scott Citation2013). Formal social network analysis (SNA) is the most fruitful way to lift networks from a heuristic to an analytical tool, linking, inter alia, actors’ structural positions with their effectiveness in the policy-making process (Adam and Kriesi Citation2007; Christopoulos Citation2008).

Networks are analytical constructs; that is, they are constructed and delineated by the researcher (Borgatti, Everett, and Johnson Citation2013; Scott Citation2013). In order to maximize the potential of observing structural power differentials, I defined my network as the participants who were tasked to provide input for the one workshop in this series of workshop meetings that would most likely engage a member of civil society; this was the group tasked to produce guidelines to increase enterprise in the municipality. I elaborate on this issue and others in the following section.

Analysis

This section sets the stage by discussing briefly the community vision plan. I then show how the professional administrators behaved entrepreneurially by fleshing out the strategies they used and connecting them with their contextual powers. Finally, I turn my attention to the remaining participants and show that though some actors were central, they did not behave entrepreneurially.

The vision plan

The former vision plan for the years 2009–2013 was outsourced to a consultant. The plan itself was inconsequential with a prominent focus on the town hall and the public sector in general. The goals listed in the document consist mostly of numerical objectives regarding housing, businesses, and infrastructure. Conversely, the brochure of the latest plan has a ‘softer’ and more personal focus (for a similar discussion on vision plan discourse, see Granberg Citation2004). The main message of the planning strategy focuses on the seven factors the municipality needs more of in order to grow. The title and logo are Mer [*] Östersund (More [*] Östersund) with the wild card asterisk representing each of these factors: welcomeness; creativity; enterprise; knowledge; solicitude, culture,Footnote3 and attractive housing. The narrative includes vignettes by the municipality’s residents, including non-ethnic Swedes with a strong message on inclusiveness.

A total of 127 people participated the workshops, 72 women and 55 men. The overall response rate just over 54%. The vast majority of respondents (almost 84%) reported representing an organization, ranging from municipal departments, the county administration, the regional administrative body, the local destination management organization, as well as local businesses and associations. This was not unintentional, but rather a direct consequence of the format of the workshops, the time of day in which they were held, as well as a feature of Swedish corporatism.

All these meetings opened with an introduction by the Tillväxt Footnote4 Östersund director, followed by a presentation relevant to the factor discussed that day. Subsequently, the participants broke off in groups to discuss concrete proposals based on three or four questions posed a priori by Tillväxt Östersund, documented by designated secretaries. Each workshop concluded with a discussion among all participants and the minutes were posted on the website. The workshops were held during business hours.

The who: Tillväxt Östersund, (bureaucratic) entrepreneurs in the polis

In line with Mintrom, Salisbury and Luetjens (Citation2014) and employing counterfactual logic, the question that emerges here is whether the municipality of Östersund would have driven a two-and-a-half-year in-house focus group process if it were not for the initiative of Tillväxt Östersund. The argument outlined in this paper is that in drafting the development plan of the city, the Tillväxt Östersund team acted entrepreneurially in their conceptualization of the process and in the way they went about carrying it out. Moreover, had it not been for them, the vision plan would not have been drafted in this long, participatory fashion. This is in line with Hysing and Olsson (Citation2012, 12), who call for more attention to bureaucrats as ‘creative and capable actors who become influential through cooperation and interaction with networks, organizations, individual politicians, etc.’ (author’s translation). I will now demonstrate the how – the strategies entrepreneurial actors used and how some of these were facilitated by their contextual power while others were leveraged on their investing personal resources.

Being innovative: creating new ideas

Tillväxt Östersund was originally tasked in 2013 to evaluate and only revise the previous plan by tweaking objectives for the new timeframe. The evaluation of the 2009–2013 vision plan showed that its contents were very poorly communicated to the citizenry (Respondent 2) and that ‘[t]his was something that should have been done in-house. People did not see themselves in it’ (Respondent 4). The unit seized the opportunity to undertake the drafting process in-house and in a manner that deviated from the past thus aiming at change both in procedural and in output terms; they used the power of evaluation and the power of initiative to do so.

Their goal was to reach as many different people and groups as possible (Respondent 1) in comparison to the external consultant who had drafted the previous document. Concluding that the previous plan had not reached the citizens as intended (Respondent 2) and after a presentation for the city manager (Respondent 3), Tillväxt Östersund got the green light to run an in-house participatory process.

An early process innovation was the fact that Tillväxt Östersund assigned a group of exchange students, in town for the summer of 2013, to devise and design a number of factors that could be deemed as community development factors. The students also designed the logo. The result was a set of 19 factors, presented as a deck of playing cards, with the logo of the new vision plan (Mer [*] Östersund). The participants of the initial plenary meeting in October 2013 were asked to rank these factors. The top seven factors (as outlined elsewhere in this paper) became the community development factors on which the vision plan centers. In 2016, both the team of students and the municipality of Östersund won prizes: the former nationally for the sustainability of the design and the latter for the best community development plan in the county of Jämtland (Östersunds Kommun Citation2016a; Östersunds Kommun Citation2016b; SYNA Citation2016)

The innovation here lay with the process and not necessarily with the content of the vision plan. The adoption of soft economic development factors aiming at quality of life issues by city planners in Europe, US, and beyond is by no means new and an issue well documented in the literature after Florida’s (Citation2002) (see Petridou and Ioannides Citation2012) work on the rise of the creative class and its contribution to urban economic development. That having said, both the process and the content were new and innovative for the municipality of Östersund.

Creating and framing a vision

The public officials used the newly established logo to convey a significantly more inclusive notion of what ‘growth’ means. ‘More [*] Östersund’ opens the door to a multitude of factors beyond jobs or residents. Not only had a logo not been employed before to convey a vision plan, but also this logo is now used extensively by the municipality – on the website, in documents, and more recently in building sites. Though the latter is common practice in most cities and municipalities worldwide, the use of the vision plan logo in a sign marking a building site is not a common practice in Östersund and speaks for the continued effort to mainstream the vision plan narrative.

The entrepreneurs used the power of the pen in order to articulate their vision. The four professional administrators were responsible for putting the input that workshop participants provided to paper and impartial though they may have been, this process involves a certain amount of translation. These concrete ideas fleshing out the general vision plan comprise the action program which constituted the conclusion and final output of the process (Lundberg Citation2017; Östersunds Kommun Citation2016a)

Mobilizing resources

Unlike political entrepreneurs who are politicians or member of civil society and can engage in a diverse range of fund-raising activities ranging from concerts (Meydani Citation2015) and the courting of political donors (Mintrom Citation2015), these bureaucratic entrepreneurs’ toolkit was rather limited. They applied for, and received, project funds in order to run a series of workshops reaching as many diverse interest groups as possible for a six-month period (Respondents 1, 2, 3, and 4). As with any grant writing exercise, it was optional and demanded time out of the professional administrators’ work schedule.

Building coalitions, building consensus

The team engaged in a continuous dialogue with other municipal departments as well as the politicians who will eventually vote on the document (Respondents 1 and 2). The goal of the unit was to reach all 5000 municipality employees in a focused attempt to raise awareness regarding community development and to mainstream the development factors outlined in the initial vision plan.

If one looks at the overarching goal [of community development], then it is hard for a kindergarten teacher, for example, to see how they can have any influence towards achieving it. But we need to have a discussion and maybe we come to the conclusion that through having a great school or by offering great services we actually create desirability. Something that perhaps people talk about around town and maybe people will move here – or stay here if they already live here – because things work so well. That’s how we create development. (Respondent 1)

Relational management

The Tillväxt Östersund unit acted not only as an idea maker through the framing of the growth issue within the municipal organization, but also as a network maker. Entrepreneurs in the polis are networked by definition, but a further strategy to achieve their goals centers on creating networks for other actors. The professional administrators of Tillväxt Östersund worked purposefully toward bringing together a wide network of diverse actors. The four professional administrators used the personal contacts in the community at large, the immigrant community, young people, the art community, as well as the business sector to actively involve people in the workshops. Continuous feedback through email was also encouraged. Tillväxt Östersund also provided logistical support to the spin-off group that was created in conjunction with the More [Enterprise] workshop.

Collective entrepreneurship: entrepreneurial team leadership

Finally, the four members of Tillväxt Östersund operated as an entrepreneurial team. Because of the dominant image of the lone entrepreneurs in the market, research has tended to focus on individual political entrepreneurs. However, Mintrom has long recognized that entrepreneurs in the polis operate in teams (see, for example, Mintrom Citation2000) and he and colleagues offered insights on team arrangements in the way policy entrepreneurs build knowledge economies in Queensland and Victoria (Mintrom, Salisbury, and Luetjens Citation2014; see also Petridou Citation2014).

The head of the unit was a buoyant person fronting the process and working closely with the business community, something that was facilitated by his previous work experience in the private sector. He supported the members of his team by giving them space, allowing them to take initiatives, even on ‘crazy ideas’ (R2). They felt they were given the space to try new things and fail and that if they did, the head of the unit would assume responsibility (Respondent 3). Each member was allocated tasks according to their individual competences, though they were very clear about the benefits of working together and learning from each other. Because of this, they were able to reach groups not normally active in participatory planning arrangements, such as young people.

What is more, there was a common vision inculcated to the team by its entrepreneurial leader. Using his interpersonal skills, he motivated the team, binding it with ‘organic solidarity’ (Schneider, Teske, and Mintrom Citation1995, 151). All four professional administrators spoke with passion about their job, about community development and about the future of Östersund. There was a shared narrative about development (see also Mintrom, Salisbury, and Luetjens Citation2014) and the importance of the seven factors outlined on the vision plan for the municipality, resulting in shirking avoidance (Schneider, Teske, and Mintrom Citation1995). summarizes this section and shows the strategies employed by the professional administrators as bureaucratic entrepreneurs and their situational powers and resources that facilitated them. The strategies involving the production of an output ideational or otherwise are facilitated by the actors’ situational powers, while it becomes apparent it takes the investment of resources in order to mobilize resources.

Networking practices of the members of civil society

I took a network approach with a focus on the interactions among the group members for the purpose of determining the function of certain actors based on their structural position (Borgatti, Everett, and Johnson Citation2013; Henning et al. Citation2012; Wasserman and Faust Citation1994). Network boundaries depend on the research question and in this study a combination of a realist and event-based strategies are used to define the network boundaries on substantive and practical grounds (Borgatti, Everett, and Johnson Citation2013). This network is limited to the participants to the More [Enterprise] workshop for two reasons: first, the entire group of participants, though interested in community development in some way, was a large, incoherent group. The participants to the More [Enterprise] workshop were the only ones who formed a spin-off group that met on a couple of later occasions and asked the municipality to provide them with a report inventorying clusters, which it did. What is more, in the literature, business, and economic (in the strict sense) development issues have been often been used as case studies for political entrepreneurship (Schneider and Teske Citation1992; Schneider, Teske, and Mintrom Citation1995; Verduijn Citation2015).

Most respondents felt that they had a say in the process; only about 2% reported perceiving that they had no influence at all. Just over half of the respondents (about 51%) reported that the issue of development in general (though not the vision plan in particular) was most urgent in their minds. The perception of conflict was not as a straightforward question, however. I did not observe any conflict whatsoever during the workshops; neither did the officials of the municipality. When I talked to respondents informally during the workshops, they also said that they experienced the process as quite orderly and without strife and indeed almost 68% of those who answered this question reported no or very little conflict. However, 44% of respondents did not answer this question at all, the highest instance of non-response. Though this might be interpreted in any number of ways, an unwillingness to answer this question could, in fact, speak to latent conflicts belying the Swedish consensual decision-making model, especially in workshops which by design and necessity do not allow for extended debates and resolution of conflicting interests. Nevertheless, there was no articulated conflict in the process. At the same time, workshop participants seem to have a shared image of what ‘development’ means. Their answers included ‘more of something’; ‘change for the better’; ‘more inhabitants’; ‘developing our city together’; and ‘being sustainable’.

I added an extra question in the online survey geared toward the 34 participants of the More [Enterprise] workshop. Each actor was asked if and how they know each of the remaining 33 participants in the workshop. I did not include the strength of tie and instead constructed a binary network: 0 for the absence of a tie, 1 for the presence of one. The result was an undirected, whole network, analyzed with UCINET (Borgatti, Everett, and Freeman Citation2002). The response rate was just over 54% and because the network was dichotomous and non-directional, I imputed the missing data with the REPLACENA command within matrix algebra (Borgatti, Everett, and Freeman Citation2002).

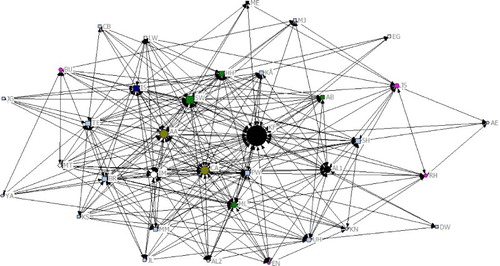

The first step was to calculate the centrality of each actor, as well as each actor type. I used the betweenness centrality measure, typically understood in terms of the capacity for control of information flows through the network, a sort of gatekeeping role implying power (Borgatti, Everett, and Johnson Citation2013). I made the assumption, based on Christopoulos and Ingold (Citation2011) and Ingold and Christopoulos (Citation2015) that entrepreneurs can be detected through positive Bonacich power. This measure qualifies the number of ties of each actor with the relational power of their alters. A positive power means that an actor’s power increases if they are connected to well-connected actors (Ingold and Christopoulos Citation2015). The centrality of alters of the focal actors increases the power of the focal actor; so betweenness centrality was also calculated for each actor as well as each actor type (Bonacich Citation1987; Christopoulos and Ingold Citation2011; Ingold and Christopoulos Citation2015).

shows that organizations supporting businesses (both state-controlled and member-owed) have the highest average betweenness score, as well as the highest average Bonacich power, followed by the politicians, making these two groups most central. Members of the regional authority and the county have the third highest scores in both the centrality measures in the network dedicated to come up with policy proposals regarding enterprise and commerce in the municipality. is a visualization of the network reflecting the data above.

Figure 2. Betweenness centrality. Shape by sex. Circle: female actors, square: male actors. Color by organizational affiliation: Pink: education; light blue: private businesses; black: business support organizations; white: municipal workers (public sector); green: region/county officials (public sector); olive green: politicians; dark blue: private persons. Shape: Bigger: higher betweenness score; smaller: smaller betweenness score. Colored version of this figure can be found in the journal website.

Table 2. Betweenness and Bonacich power per actor type.

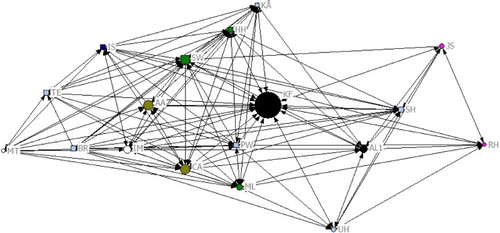

shows only the actors who scored above the mean in positive Bonacich power confirming the prevalence of actors from business support organizations, politicians, and officials from the region/county.

Figure 3. Actors scoring above the mean on positive Bonacich Power. Shape by sex. Circle: female actors, square: male actors. Color by organizational affiliation: Pink: education; light blue: private businesses; black: business support organizations; white: municipal workers (public sector); green: region/county officials (public sector); olive green: politicians; dark blue: private persons. Shape: Bigger: higher Bonacich power score; smaller: smaller Bonacich power score. Colored version of this figure can be found in the journal website.

These central actors have the potential of being entrepreneurs; whether they can be identified as such, however, is determined through triangulation with interview and survey data. To the survey question asking respondents to identify actors with influence, 18 answers were recorded. The local politicians are named as influential by two respondents, business support organizations are named by one person while (unsurprisingly and supporting my own judgement) the Tillväxt Östersund team is named by five respondents. What is more, I asked all members of Tillväxt Östersund whether one group or actor had been noticeably vocal in an attempt to get their proposal on the vision plan; all four reported that no group had lobbied them. What they did report, however, is that a spin-off group was created after the More [Enterprise] workshop, a group that met a few times to discuss the business environment in Östersund, asking among other things, for the municipality to inventory the business clusters in the area. Three of the most central actors in the network (one from a business support organization, one from the region and one from the municipality) and with Bonacich power scores above the mean were part of that group. The question that emerges, however, is whether the members of civil society behaved entrepreneurially in this situation. Indeed, they were more central than other workshop participants but other than forming a coalition, no other behavior typical of policy entrepreneurs was observed.

Discussion

The four professional administrators of Tillväxt Östersund acted as policy entrepreneurs employing six strategies: first, facilitated by the power of evaluation and the power of initiative, they were innovative and created a new idea. Second, facilitated by the power of the pen, they used framing strategies to shift to an inclusive vision of ‘growth’ beyond the traditional idea of more jobs or more residents. Third, they mobilized resources and persevered through a long and tedious process with a view to see it through and make a transformative change for the municipality. Fourth, they worked continuously to achieve consensus. Fifth, they worked to create informal networks in which to anchor the new vision plan. Finally, they did this as a team. Their drive stemmed from their perception of urgency regarding community development issues and on the fact that it was their job as public officials to be creative and ‘do a good job’ (Respondent 2). The latter four strategies required the investment of personal and situational resources: contacts, information, time, social, and political capital.

These strategies are in line with entrepreneurial strategies used by actors in pluralistic environments and in more complex policy sectors. However, there exist nuances. More specifically, the professional administrators were trying to achieve consensus, not merely a coalition. This may be explained by the consensual sensibilities of the Swedish corporatist system as well as by the low complexity of the process. Additionally, it was very clear that these entrepreneurs worked in a team and that no one actor could have achieved the same results. This is a function of the position of the entrepreneur as a professional administrator in a bureaucratic organization which does not lend itself to one person ‘going it alone’. This participatory process was too multifaceted to have been run by one person.

Members of civil society also reported a sense of urgency regarding the issue of development. Indeed, even though everyday planning processes such as this one may appear routine in comparison to high politics, there are actors who are more central and more active than others. Notably, the actors that were most central were the most ‘inside’ ones as well – politicians and representatives from business support organizations. Having said this, the finding suggests that the members of civil society did not act entrepreneurially. This is perhaps not surprising when we pause to consider what ‘opportunity’, ‘gain’, and ‘change’ mean for the agentic capacity of different groups of actors. This participatory planning process had no clear winners and losers. Furthermore, there were neither clear ‘gains’ involved nor any funds tied to a specific policy outcome. Lastly, even in practice, the process was quite inclusive when it came to attracting as many local interest organizations as possible.

Conversely, the concepts of ‘opportunity’, ‘gains’, and ‘change’ were of sharper focus from the viewpoint of the bureaucrats. The Tillväxt Östersund team considered the issue of development very urgent for the prosperity of the municipality and it was their job to do something about it. All four spoke of their jobs in terms pointing to a very strong commitment to, and even passion for, their profession. They partly owned the decision-making resources and the path to change, if not straightforward, at least only had one stop: the approval of the plan by the politicians.

Additionally, we must not lose sight that this process took place in the larger background of the Swedish corporatist system with its specific consensual sensibilities. On the one hand, public sector officials have considerable leeway in their everyday workflow; on the other hand, political interests are organized and at times seen as co-opted in the decision-making arrangements. The fact that interest organizations have a guaranteed seat at the table may result in them becoming too complacent to be willing to spend the energy in being creative when pursuing an issue or even shy away from innovative solutions in general. Additionally, a system built around organized interest organizations may make it hard for an interested but unorganized citizen to pursue a single issue. This is in line with the results of this research suggesting that the public officials were entrepreneurial, the members of civil society were active and there were not any single-issue policy entrepreneurs among interested, unorganized citizens.

Finally, the causal mechanism between contextual factors and entrepreneurship cannot be determined from the research conducted in this paper alone. It is unclear whether the lack of policy entrepreneurship among members of civil society was due to the low complexity of the policy process or the consensual nature of the Swedish political system in general. The possibility emerges that different groups of actors (public officials vs. members of civil society vs. single citizens) have different thresholds when it comes to engaging a process in an entrepreneurial way based on the level of competition engendered by a given policy problem in a given policy context. Furthermore, comparative research in routine participatory planning processes is required to further flesh out contextual factors such as policy complexity and political system that may foster or hinder entrepreneurship among bureaucrats and members of civil society, respectively.

Conclusion

This research aimed at contributing to the scholarship on the theories of policy process by leveraging entrepreneurial agency in a context hitherto under-researched, that of routine planning processes at the local level. The change effected in this case was the drafting of the community vision plan in procedural as well as output terms.

The main findings of this paper suggest that the strategies of the entrepreneurial bureaucratic actors in the routine planning process in the Swedish consensual system are generally in line with strategies employed by entrepreneurs elsewhere in more complex and conflictual planning processes. However, there are differences: more than assembling a coalition, the professional administrators aimed at achieving consensus; what is more, the element of working in a team was of great salience for the success of the process. The strategies that aimed at producing an output, such as a vision or an idea, were facilitated by situational powers of these professional administrators, whereas the strategies that involved mobilizing resources required the investment of personal and situational resources of these entrepreneurs.

Civil society members were found to be central, but not entrepreneurial. More research is required to further investigate the conditions under which entrepreneurs may emerge in contexts without articulated conflict involving low-complexity processes.

Notes on Contributor

Evangelia Petridou is adjunct assistant professor of Political Science at the Risk and Crisis Research Center and Mid Sweden University in Sweden. She is a public policy and public administration scholar and her research interests focus on policy and institutional entrepreneurship; routine emergency management; collaborative management; networked governance, and social network analysis. Evie's recent work has appeared in the Policy Studies Journal (2014) and Policy and Society (2017). She was co-editor of Entrepreneurship in the Polis: Understanding Political Entrepreneurship (Ashgate, 2015).

ORCID

Evangelia Petridou http://orcid.org/0000-0001-7316-4899

Notes

1 Mer [*] Östersund: Strategiska satsningar för ökad tillväxt.

2 It was not possible to contact six of the participants because they had not provided a valid email address.

3 ‘Culture’ here means ‘art’.

4 This is the team of four municipal workers working on issues of economic development and the vision plan.

References

- Ackrill, Robert, and Adrian Kay. 2011. “Multiple Streams in EU Policy-making: The Case of the 2005 Sugar Reform.” Journal of European Public Policy 18 (1): 72–89. doi:10.1080/13501763.2011.520879.

- Ackrill, Robert, Adrian Kay, and Nikolaos Zahariadis. 2013. “Ambiguity, Multiple Streams, and EU Policy.” Journal of European Public Policy 20: 871–887. doi: 10.1080/13501763.2013.781824

- Adam, Silke, and Hanspeter Kriesi. 2007. “The Network Approach.” In Theories of the Policy Process, edited by Paul A. Sabatier, 129–154. Boulder, CO: Westview.

- Alterman, Rachelle, David Harris, and Morris Hill. 1984. “The Impact of Public Participation on Planning: The Case of the Derbyshire Structure Plan.” The Town Planning Review 55 (2): 177–196. doi: 10.3828/tpr.55.2.f78767r1xu185563

- Böcher, Michael. 2015. “The Role of Policy Entrepreneurs in Regional Government Processes.” In Entrepreneurship in the Polis: Understanding Political Entrepreneurship, edited by Inga Narbutaité-Aflaki, Evangelia Petridou, and Lee Miles, 73–86. Burlington, VT: Ashgate.

- Bogason, Peter. 2000. Public Policy and Local Governance. Northampton: Edward Elgar.

- Bonacich, Phillip. 1987. “Power and Centrality: A Family of Measures.” American Journal of Sociology 92: 1170–1182. doi: 10.1086/228631

- Borgatti, Stephen P., Martin G. Everett, and Linton C. Freeman. 2002. Ucinet 6 for Windows. Software for Social Network Analysis. Harvard, MA: Analytic Technologies.

- Borgatti, Stephen P., Martin G. Everett, and Jeffrey C. Johnson. 2013. Analyzing Social Networks. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Brouwer, Stijn, and Frank Biermann. 2011. “Towards Adaptive Management: Examining the Strategies of Policy Entrepreneurs in Dutch Water Management.” Ecology and Society 16. doi: 10.5751/ES-04315-160405

- Capano, Giliberto, Jeremy Rayner, and Anthony R. Zito. 2012. “Governance from the Bottom Up: Complexity and Divergence in Comparative Perspective.” Public Administration 90 (1): 56–73. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9299.2011.02001.x.

- Carter, Ralph G., and James M. Scott. 2009. Choosing to Lead: Understanding Congressional Foreign Policy Entrepreneurs. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Christopoulos, Dimitrios C. 2006. “Relational Attributes of Political Entrepreneurs: A Network Perspective.” Journal of European Public Policy 13 (5): 757–778. doi:10.1080/13501760600808964.

- Christopoulos, Dimitrios C. 2008. “The Governance of Networks: Heuristic or Formal Analysis? A Reply to Rachel Parker.” Political Studies 56: 475–481. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9248.2008.00733.x.

- Christopoulos, Dimitrios C., and Karin Ingold. 2011. “Distinguishing between Political Brokerage and Political Entrepreneurship.” Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 10: 36–42. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.01.006

- David, Charles-Philippe. 2015. “How Do Entrepreneurs Make National Security Policy? A Case Study of the G.W. Bush Administration.” In Entrepreneurship in the Polis: Understanding Political Entrepreneurship, edited by Inga Narbutaité Aflaki, Evangelia Petridou, and Lee Miles, 151–170. Burlington, VT: Ashgate.

- Davidoff, Paul. 1965/2012. “Advocacy and Pluralism in Planning.” In Readings in Planning Theory, edited by Susan S. Fainstein and Scott Campbell, 191–205. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

- Eckstein, Harry. 1992. Regarding Politics: Essays on Political Theory, Stability and Change. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Florida, Richard. 2002. The Rise of the Creative Class. New York: Basic Books.

- Forester, John. 1989. Planning in the Face of Power. Berkeley: University of California.

- Forester, John. 2008/2012. “Challenges of Deliberation and Participation.” In Readings in Planning Theory, edited by Susan S. Fainstein and Scott Campbell, 206–213. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

- Gerring, John. 2008. “Case Selection for Case-Study Analysis: Qualitative and Quantitative Techniques.” In The Oxford Handbook of Political Methodology, edited by Janet M. Box-Steffensmeier, Henry E. Brady, and David Collier, 645–684. Oxford: OUP.

- Granberg, Mikael. 2004. “Från lokal välfärdsstat till stadspolitik. Politiska Processer mellan demokrati och effektivitet: Vision Mälarstaden och Östra hamnen i Västerås.” PhD diss., Political Science, Örebro.

- Hall, Patrik. 2013. “NPM in Sweden: The Risky Balance Between Bureaucracy and Politics.” In Nordic Lights: Work, Management and Welfare in Scandinavia, edited by Åke Sandberg, 406–419. Stockholm: SNS Förlag.

- Henning, Marina, Ulrik Brandes, Jürgen Pfeffer, and Ines Mergel. 2012. Studying Social Networks. Frankfurt: Campus Verlag.

- Huitema, Dave, and Sander Meijerink. 2010. “Realizing Water Transitions: The Role of Policy Entrepreneurs in Water Policy Change.” Ecology and Society 15.

- Hysing, Erik, and Jan Olsson. 2011. “Who Greens the Northern Light? Green Inside Activists in Local Environmental Governing in Sweden.” Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy 29 (4): 693–708. doi:10.1068/c10114.

- Hysing, Erik, and Jan Olsson. 2012. Tjänstemän I Politiken. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

- Idler, Ellen L., Shawna V. Hudson, and Howard Leventhal. 1999. “The Meanings of Self-Ratings of Health.” Research on Aging 21: 458–476. doi: 10.1177/0164027599213006

- Ingold, Karin, and Dimitris Christopoulos. 2015. “The Networks of Political Entrepreneurs: A Case Study of Swiss Climate Policy.” In Entrepreneurship in the Polis: Understanding Political Entrepreneurship, edited by Inga Narbutaité Aflaki, Evangelia Petridou, and Lee Miles, 17–30. Burlington, VT: Ashgate.

- Ioannides, Dimitri. 2015. “City Planners as Political Entrepreneurs: Do They Exist? Can They Exist?” In Entrepreneurship in the Polis: Understanding Political Entrepreneurship, edited by Inga Narbutaité Aflaki, Evangelia Petridou, and Lee Miles, 43–54. Burlington, VT: Ashgate.

- Kingdon, John. 1984/2003. Agendas, Alternatives, and Public Policies. 2nd ed. New York: Longman.

- Klein Woolthuis, Rosalinde, Fransje Hooimeijer, Bart Bossink, Guus Mulder, and Jeroen Brouwer. 2013. “Institutional Entrepreneurship in Sustainable Urban Development: Dutch Successes as Inspiration for Transformation.” Journal of Cleaner Production 50: 91–100. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2012.11.031

- Lipsky, Michael. 1980/2010. Street Level Bureaucracy: Dilemmas of the Individual in Public Services. New York: Russell Sage.

- Lundberg, Tobias. 2017. Mer[*] Östersund. Kul att Det Händer Något. [More [*] Östersund. Cool That Something Is Happening]. Accessed May 27, 2017. https://prezi.com/mmfarysiidfn/mer-ostersund-kul-att-det-hander-nagot/?utm_campaign=share&utm_medium=copy.

- Mackenzie, Chris. 2004. “Policy Entrepreneurship in Australia: A Conceptual Review and Application.” Australian Journal of Political Science 39: 367–386. doi: 10.1080/1036114042000238564

- Meijerink, Sander, and Dave Huitema. 2010. “Policy Entrepreneurs and Change Strategies: Lessons from Sixteen Case Studies of Water Transitions Around the Globe.” Ecology and Society 15 (2). doi: 10.5751/ES-03509-150221

- Meydani, Assaf. 2009. Political Transformations and Political Entrepreneurs: Israel in Comparative Perspective. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Meydani, Assaf. 2015. “Political Entrepreneurs and Institutional Change: Governability, Liberal Political Culture, and the 1992 Electoral Reform in Israel.” In Entrepreneurship in the Polis: Understanding Political Entrepreneurship, edited by Inga Narbutaité-Aflaki, Evangelia Petridou, and Lee Miles, 87–102. Burlington, VT: Ashgate.

- Miles, Matthew, and A. Michael Huberman. 1994. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Mintrom, Michael. 2000. Policy Entrepreneurs and School Choice. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

- Mintrom, Michael. 2013. “Policy Entrepreneurs and Controversial Science: Governing Human Embryonic Stem Cell Research.” Journal of European Public Policy 20: 442–457. doi: 10.1080/13501763.2012.761514

- Mintrom, Michael. 2015. “Policy Entrepreneurs and Morality Politics: Learning from Failure and Success.” In Entrepreneurship in the Polis: Understanding Political Entrepreneurship, edited by Inga Narbutaité Aflaki, Evangelia Petridou, and Lee Miles, 103–118. Burlington, VT: Ashgate.

- Mintrom, Michael, and Phillipa Norman. 2009. “Policy Entrepreneurship and Policy Change.” Policy Studies Journal 37 (4): 649–667. doi:10.1111/j.1541-0072.2009.00329.x.

- Mintrom, Michael, Chris Salisbury, and Joannah Luetjens. 2014. “Policy Entrepreneurs and Promotion of Australian State Knowledge Economies.” Australian Journal of Political Science 49: 423–438. doi: 10.1080/10361146.2014.934657

- Mintrom, Michael, and Sandra Vergari. 1996. “Advocacy Coalitions, Policy Entrepreneurs, and Policy Change.” Policy Studies Journal 24 (3): 420–434. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0072.1996.tb01638.x

- Montin, Stig. 2016. “Municipalities, Regions, and County Councils: Actors and Institutions.” In The Oxford Handbook of Swedish Politics, edited by Jon Pierre, 367–382. Oxford: OUP.

- Nyström, Jan, and Lennart Tonell. 2012. Planeringens Grunder. 3rd ed. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

- Olsson, Jan, and Erik Hysing. 2012. “Theorizing Inside Activism: Understanding Policymaking and Policy Change from Below.” Planning Theory & Practice 13 (2): 257–273. doi: 10.1080/14649357.2012.677123

- Östersunds Kommun. 2016a. Unikt designpris till Östersunds Kommun för ett Hållbart Samhälle. [Unique Design Prize to the Municipality of Östersund för a Sustainable Society]. Accessed February 27, 2017. http://ostersund.se/om-webbplatsen/nyhetsarkiv/nyhetsarkiv/2016-11-24-unikt-designpris-till-ostersunds-kommun-for-ett-hallbart-samhalle.html.

- Östersunds Kommun. 2016b. Östersund Wins Pris ‘Bästa Tillväxt 2016’ [Östersund Wins Prize ‘Best Development 2016’]. Accessed February 27, 2017. http://ostersund.se/om-webbplatsen/nyhetsarkiv/nyhetsarkiv/2016-11-16-ostersund-vinner-priset---basta-tillvaxt-2016.html.

- Östersunds Kommun. n.d. a. Mer [*] Östersund: Strategiska Satsningar för Ökad Tillväxt [More[*] Östersund: Strategic Investments for Increased Development]. Accessed March 24, 2017. http://www.regionjamtland.se/innovation/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Strategiska-satsningar-f%C3%B6r-%C3%B6kad-tillv%C3%A4xt.pdf.

- Östersunds Kommun. n.d. b. Så Skapar Vi Mer Östersund [This Is How We Create More Östersund]. Accessed February 27, 2017. http://www.ostersund.se/tillvaxt.

- Peters, B. Guy. 2015. Advanced Introduction to Public Policy. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Peters, B. Guy, and Jon Pierre. 2006. “Introduction.” In The Handbook of Public Policy, edited by B. Guy Peters and Jon Pierre, 1–9. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Peters, B. Guy, Jon Pierre, and Gerry Stoker. 2010. “The Relevance of Political Science.” In Theory and Methods in Political Science, edited by David Marsh and Gerry Stoker, 325–342. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Petridou, Evangelia. 2014. “Theories of the Policy Process: Contemporary Scholarship and Future Directions.” Policy Studies Journal 41 (S1): 12–32. doi: 10.1111/psj.12054

- Petridou, Evangelia, Inga Narbutaité Aflaki, and Lee Miles. 2015. “Unpacking the Theoretical Boxes of Political Entrepreneurship.” In Entrepreneurship in the Polis: Understanding Political Entrepreneurship, edited by Inga Narbutaité Aflaki, Evangelia Petridou, and Lee Miles, 1–16. Burlington, VT: Ashgate.

- Petridou, Evangelia, and Dimitri Ioannides. 2012. “Conducting Creativity in the Periphery of Sweden: A Bottom-up Path Towards Territorial Cohesion.” Creative Industries Journal 5: 119–137. doi: 10.1386/cij.5.1-2.119_1

- Pierre, Jon. 2000. “Introduction: Understanding Governance.” In Debating Governance: Authority, Steering and Democracy, edited by Jon Pierre, 1–12. Oxford: OUP.

- Pierre, Jon. 2009. “Tillväxtpolitikens Styrningsproblem.” In Samhällsstyrning i förändring, edited by Jon Pierre and Göran Sundström, 72–89. Malmö: Liber.

- Pierre, Jon. 2011. The Politics of Urban Governance. New York: Palgrave McMillan.

- Pierre, Jon, and B. Guy Peters. 2005. Governing Complex Societies. New York: Palgrave McMillan.

- Pike, Andy, Andrés Rodríguez- Pose, and John Tomaney. 2006. Local and Regional Development. New York: Routledge.

- Pressman, Jeffrey L., and Aaron Wildavsky. 1984. Implementation. 3rd ed. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Rhodes, R. A. W. 1997. Understanding Governance: Policy Networks, Governance, Reflexivity, and Accountability. Buckingham: Open University Press.

- Rhodes, R. A. W. 2000. “Governance and Public Administration.” In Debating Governance. Authority, Steering and Democracy, edited by Jon Pierre, 54–90. Oxford: OUP.

- Schneider, Mark, and Paul Teske. 1992. “Toward a Theory of the Political Entrepreneur: Evidence from Local Government.” American Political Science Review 86 (3): 737–747. doi: 10.2307/1964135

- Schneider, Mark, Paul Teske, and Michael Mintrom. 1995. Public Entrepreneurs: Agents of Change in American Government. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University.

- Scott, John. 2013. Social Network Analysis. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Sheingate, Adam D. 2003. “Political Entrepreneurship, Institutional Change, and American Political Development.” Studies in American Political Development 17: 185–203. doi: 10.1017/S0898588X03000129

- Smedby, Nora, and Lena Neij. 2013. “Experiences in Urban Governance for Sustainability: The Constructive Dialogue in Swedish Municipalities.” Journal of Cleaner Production 50: 148–158. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2012.11.044

- SYNA. 2016. Vinnarna av Bästa Tillväxt 2016 [Winners of Best Development 2016]. Accessed February 27, 2017. https://upplysningar.syna.se/Nyheter/Nyhet?id=vinnarna-av-basta-tillvaxt-2016/.

- Theodoulou, Stella Z., and Matthew A. Cahn. 1995. “The Contemporary Language of Public Policy: A Starting Point.” In Public Policy: The Essential Readings, edited by Stella Z. Theodoulou and Matthew A. Cahn, 1–19. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Verduijn, Simon. 2015. “Setting the Policy Agenda: A Policy Entrepreneurial Perspective on Urban Development in the Netherlands.” In Entrepreneurship in the Polis: Understanding Political Entrepreneurship, edited by Inga Narbutaité-Aflaki, Evangelia Petridou, and Lee Miles, 55–72. Burlington, VT: Ashgate.

- Wasserman, Stanley, and Katherine Faust. 1994. Social Network Analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Weible, Christopher M. 2014. “Introducing the Scope and Focus of Policy Process Research and Theory.” In Theories of the Policy Process, edited by Paul A. Sabatier, and Christopher M. Weible, 3–21. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

- Windrum, Paul. 2008. “Conclusions: Public Innovation and Entrepreneurship.” In Innovation in Public Sector Services: Entrepreneurship, Creativity and Management, edited by Paul Windrum and Per Koch, 228–243. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Wollman, Hellmut, and Kurt Thurmaier. 2012. “Reforming Local Government Institutions and the New Public Management.” In The Oxford Handbook of Urban Politics, edited by Karen Mossberger, Susan E. Clarke, and Peter John, 180–209. Oxford: OUP.

- Zahariadis, Nikolaos. 2007. “The Multiple Streams Framework: Structure, Limitations, Prospects.” In Theories of the Policy Process, edited by Paul A. Sabatier, 65–92. Boulder, CO: Westview.

- Zahariadis, Nikolaos. 2014. “Ambiguity and Multiple Streams.” In Theories of the Policy Process, edited by Paul A. Sabatier and Christopher M. Weible, 25–58. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

- Zahariadis, Nikolaos, and Theofanis Exadaktylos. 2016. “Policies That Succeed and Programs That Fail: Ambiguity, Conflict, and Crisis in Greek Higher Education.” Policy Studies Journal 44: 59–58. doi: 10.1111/psj.12129