ABSTRACT

Policy integration has come to be known as the Holy Grail of public policy. Given the increased complexity of societal problems, academics and policymakers alike have called for better integrated governance approaches to deal with these problems more effectively. Despite the intuitive appeal of these calls, pursuing policy integration may not always be expedient, as it comes with significant costs and pitfalls. So far, the question of when pursuing policy integration may be considered opportune has remained largely unaddressed in the public policy literature. This article takes up this question and addresses it by discussing two interrelated elements: the desirability and the feasibility of policy integration. The former is reflected upon by synthesizing the main pros and cons that emerge from previous studies. The latter is addressed by proposing a heuristic that evaluates policy integration possibilities based on two key determinants: integrative capacity and leadership. Together, the synthesis and heuristic can serve as a point of departure for more critical reflections on pushes for more policy integration and on how to allocate scarce resources. The other way around, the heuristic allows policy entrepreneurs pushing for integrated “solutions” to focus their attention on the variables that matter most.

1. Introduction

The pursuit of policy integration has come to be known as the “Holy Grail”, “Philosopher's Stone”, or “the eternal problem” of public governanceFootnote1 (Perri 6 et al. Citation2002; Peters Citation2015; Candel Citation2017). Both academics and policymakers alike consider strengthening integrative governance approaches as the way forward in dealing with a range of societal problems that have become increasingly complex due to globalization, public sector reforms, and datafication, among other factors. A simple Scopus search shows that the amount of social science research on policy integration has steadily increased in the new millennium, from 5 peer-reviewed publications in 2000 to 63 in 2018.Footnote2 Examples of pressing problems that have attracted considerable attention from policy integration scholars include climate and environmental concerns, food insecurity, and gender inequalities (e.g. Cejudo and Michel Citation2017; Rees Citation2005; Jordan and Lenschow Citation2010; Runhaar et al. Citation2018). The central assumption of proponents of pushes for strengthened policy integration is that concerted policy efforts will be more effective in achieving desired outcomes compared to traditional compartmentalized policymaking.

Despite the intuitive appeal of calls for policy integration, investing scarce resources into its pursuit may not always be opportune. Indeed, public policy scholars have pointed at various downsides and costs associated with attempts to increase levels of policy integration (Jordan and Halpin Citation2006; Peters Citation2018). Others have argued that the desirability of more integration is first and foremost an empirical question (Hogl, Kleinschmit, and Rayner Citation2016). This raises the question of when exactly pursuing policy integration may be considered expedient. In his concluding thoughts in an article on coordination, Guy Peters (Citation2018, 9–10) summarizes this dilemma well:

The practical issues for producing coordination are troublesome, but the normative issues involved may be even more difficult. How much effort should be invested in attempting to create coordination, and in what circumstances? Can the resources be better used to deliver the services rather than coordinate them? Although much of the literature on policy coordination treats better coordinated programs as an unalloyed virtue, in the real world of governing some balancing may be required. The appropriate balance will depend upon a number of factors, but political and professional judgments are required to make the correct decision on coordination.

The synthesis and heuristic presented in this article are first and foremost a theoretical enterprise. Together, they can serve as a point of departure for more critical reflections on pushes for more policy integration and on how to allocate scarce resources, both in policy arenas and in academic debates. Regarding the latter, most studies still seem to automatically assume that (environmental/ climate/ etc.) policy integration is desirable in itself (Hogl, Kleinschmit, and Rayner Citation2016), which, following from the above, can be questioned. In addition, as will be further discussed in Section 5, the theoretical argument may open up new avenues of research on policy integration.

It is important to note that I develop the argument around horizontal policy integration, i.e. integration within and between policy sectors. That said, much of what follows may also be relevant to questions of vertical integration between levels of government (cf. Briassoulis Citation2004).

The article proceeds with a brief elaboration of how I conceptualize policy integration. Subsequently, section 3 presents a discussion of the desirability of policy integration by synthesizing the most frequently mentioned pros and cons. Section 4 then sets out the heuristic for assessing the feasibility of strengthening policy integration, after first discussing the two key determinants – integrative capacity and integrative leadership – in more detail. The article ends with a concise discussion reflecting on follow-up research opportunities and practical implications.

2. A processual understanding of policy integration

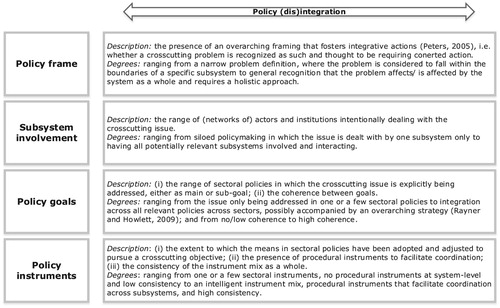

Policy integration has been conceptualized in different ways (Cejudo and Michel Citation2017; Tosun and Lang Citation2017). Here, I adopt a processual approach, in which policy integration is considered a process over time encompassing various degrees and dimensions (Candel and Biesbroek Citation2016). This conceptualization was developed following on criticism of earlier publications that approached integration as a static outcome or desired governance principle. Instead, we argued that policy integration should be as much about disintegration as about advances in integration, and that there are many shades of grey between sectoral policymaking and full policy integration (see also: Metcalfe Citation1994; Geerlings and Stead Citation2003). The four dimensions of policy integration distinguished are: (i) policy frame, (ii) subsystem involvement, (iii) goals, and (iv) instruments. presents a simplified version of this approach. Whereas the figure describes what the highest and lowest degrees of policy integration for each of the dimensions would entail, the original framework distinguishes two ideal-type manifestations in between these extremes. Strengthening policy integration thus refers to a shift towards higher degrees on this scale for one or more dimensions.

Figure 1. Simplified version of the processual policy framework (Candel and Biesbroek Citation2016).

3. How desirable is strengthening policy integration?

The overall desirability of strengthening policy integration is first and foremost a normative question. Based on their weighing of the advantages and disadvantages, decision-makers may choose for alternate directions. It is therefore worthwhile to take a closer look at the most important pros and cons that can play a role in such weighing exercises. This section synthesizes three of each as these emerge from the public policy literature. Importantly, ultimate decisions will not only be affected by these factors, but also by the (perceived) urgency of the crosscutting problem at hand (cf. Jones and Baumgartner Citation2005).

A first, and perhaps obvious, reason for pursuing policy integration is that integrated approaches may simply be more effective in addressing crosscutting problems (Briassoulis Citation2004). Although this remains an empirical question, anecdotal evidence seems to suggest that concerted efforts may indeed be more effective in dealing with intractable problems compared to siloed approaches. Jochim and May (Citation2010), for example, suggest that the cross-sectoral pollution abatement regime that emerged in the U.S. in the 1970s played an important role in dealing more effectively with a range of environmental harms. Similarly, Brazil's success in reducing the amount of people suffering from food insecurity in the early 2000s is often attributed to its ambitious integrated Fome Zero (“Zero Hunger”) programme (Rocha Citation2009). As these and many other urgent challenges span the boundaries of jurisdictions, the myopic nature of policymaking may simply not suffice (Jochim and May Citation2010).

Secondly, increased policy integration can reduce many of the inefficiencies in public policymaking. The many duplications and contradictions that characterize contemporary governance arrangements are often a waste of public resources (Peters Citation2018). Releasing some of these resources through better integrated policy efforts vis-à-vis one issue may enhance capacities to govern others. This point can also be approached from the perspective of ultimate target groups. Reducing some of the incoherencies in demands and requirements that target groups face may allow them to use their time and energy for more productive activities as well as improve chances of achieving desired outcomes. Huttunen (Citation2015), for example, shows how Finnish farmers experienced well-intended agri-environmental schemes as incoherent in relation to their own goals and practices as well as to the goals of broader agricultural policy efforts, resulting in poor functioning of these schemes.

Third, apart from these more functionalist arguments, pursuing policy integration may serve an important political function. Aligning policies so that they come to contribute to a set of overarching goals, and deciding upon these goals in the first place, often requires extensive bargaining and compromising, both at political and administrative levels. Although these interactions may be time- and resource-consuming, they contribute to a better alignment of interests and prioritization of objectives. Adelle, Jordan, and Benson (Citation2015), for example, show how in the case of EU mercury policy increased interactions within an inter-sector network helped to reconcile economic and environmental interests.

Paradoxically, the most frequently mentioned cons of pursuing strengthened policy integration are about largely the same themes. First, in terms of effectiveness and efficiency, as argued before it remains to be seen whether integrated approaches are indeed more effective in achieving desired outcomes. Public policy scholars have shown that many policy integration attempts do not proceed beyond symbolic levels (Candel Citation2017), either because integrated goals are not complemented with instruments or because integrated policy outputs are not or not fully implemented (see Section 4.3). Examples are abundant and include sustainable development strategies and climate change mitigation plans (Casado-Asensio and Steurer Citation2014, Citation2016), the greening of agricultural policy (Alons Citation2017), integrated food security strategies (Drimie and Ruysenaar Citation2010), and mainstreaming climate change adaptation (Runhaar et al. Citation2018), inter alia. Although symbolic integration may have value of its own (cf. Dupuis and Biesbroek Citation2013; Casado-Asensio and Steurer Citation2014), the question of whether this always justifies the amount of resources invested in pursuing policy integration seems justified. In addition, policy integration may result in renewed pillarisation, as Adelle, Pallemaerts, and Chiavari (Citation2009) warned for in the case of the integration of energy and climate change by embedding them in a single department.

Second, there is the possibility of trade-offs as enhancing the integration around one issue requires transferring resources from other areas, which is likely to result in losses of performance elsewhere (Underdal Citation1980). Moreover, although integrated approaches are advocated for most pressing issues nowadays (e.g. see: United Nations Citation2015), strengthening integration vis-à-vis one issue often requires a weakening of integration versus another (cf. Adelle, Jordan, and Benson Citation2015). Furthermore, there is a risk that a preoccupation with strengthening policy integration among leadership may result in reduced attention and devotion to programmes at subsystem level (Mickwitz et al. Citation2009). It is with an eye on this risk that Jochim and May (Citation2010) stress that substantive policy efforts at subsystem level should be coordinated, not replaced, by procedural instruments at system-level.

Third, whereas integrated policymaking has become a pervasive ambition across governments, it may at times conflict with other political values, such as decentralization, broader participation, privacy, and citizens’ civil liberties (Underdal Citation1980; Peters Citation2018). Additionally, whereas better integration can help overcoming the short-sightedness of and overlaps in public bureaucracies, there are good grounds for governments to be organized along specialized entities in the first place (Peters Citation2015). There is a risk that specialisation comes to be considered as undesired by definition. What is more, a certain degree of redundancy is hypothesized to strengthen governments’ ability to signal and manage risks and shocks (Landau Citation1969; Termeer et al. Citation2015), and may foster some healthy competition between entities that can actually increase the efficiency of a system as a whole.

The overall impression that arises is that pursuing policy integration in a manner that does more good than harm requires careful consideration of the pros and cons at any given moment, which is largely a political activity. The outcome of such considerations may sometimes be that it would be more opportune to settle for relatively lower, less glamorous degrees of policy integration (Jordan and Halpin Citation2006). At other times, realizing higher levels of integration may still be considered desirable.

An element that deserves further exploration is the feasibility of strengthening policy integration. Even if an integrated approach might be effective and desired, what is the point if it proves infeasible to organise? This point largely relates to the abovementioned arguments surrounding effectiveness and efficiency, though is about intermediate rather than final outcomes.

4. How feasible is strengthening policy integration?

This section proposes a heuristic that can be used to judge the feasibility of pursuing strengthened policy integration. Before presenting the heuristic, its two main variables are discussed. The public policy literature has identified a broad range of factors that enable or impede strengthened policy integration (e.g. see: Vince Citation2015; Candel Citation2017). Interestingly, many of these factors can work in both ways: depending on context and calibration they can either contribute to integration or disintegration (Peters Citation2015). Biesbroek and Candel (Citation2019) have therefore recently pleaded for moving beyond identifying static barriers or enabling conditions towards assessing the precise causal mechanisms through which these come to influence policy integration outcomes (see also: Biesbroek et al. Citation2014). That said, while many conditions may affect policy integration processes in some way, there is considerable agreement about the conditions that are considered key to making a success out of pushes for enhanced policy integration. Successful policy integration here refers to the ability to go beyond symbolic levels, i.e. to realize genuine policy change across sectors. I synthesize these key conditions along two variables: capacity and leadership (Ross and Dovers Citation2008; Nunan, Campbell, and Foster Citation2012). Whereas the former is largely related to the institutional context in which policy integration takes place, i.e. polity, the latter involves the politics of integration. The heuristic proposed in this section starts from the hypothesis that full policy integration (see below) will not be feasible without sufficient presence of these two variables.

4.1. Integrative capacity

Although policy capacity has been a subject of interest within the policy sciences for some time now (e.g. Bakvis Citation2000; Parsons Citation2004; Painter and Pierre Citation2005), an authoritative conceptualization has not yet emerged. Here, I follow Wu, Howlett, and Ramesh (Citation2018, 3) in defining policy capacity as the set of analytical, operational and political skills and competences necessary to perform policy functions, which can be discerned at three levels: individual, organizational, and systemic (see also: Gleeson et al. Citation2011). Analytical capacities serve to make sure that policies are technically sound and as such can contribute to attaining goals; operational capacities to align resources with actions to facilitate implementation; and political capacities to obtain and sustain political support for actions (Wu, Howlett, and Ramesh Citation2018, 5). Although the precise nature of the relationship between policy capacity and policy success remains underexplored (Howlett Citation2018), the presence of these skills and competences is assumed to be beneficial, or even prerequisite, to steering (through policy) society in desired directions.

Policy capacity for policy integration requires additional and specific types of these capacities. Whereas scholars of coordination and policy integration have pointed at the importance of capacity (Hertin and Berkhout Citation2003; Ross and Dovers Citation2008; Rayner and Howlett Citation2009), the precise relationship between the two concepts has hardly been elaborated. One of the more pronounced approaches is found in the work of Jordan and Schout (Citation2006) on environmental policy integration (EPI) in the European Union. Drawing upon the work of Mintzberg (Citation1983), they distinguish six coordination capacities that they use to assess EPI at EU level and in three Member States: (i) hierarchical mechanisms, (ii) bureaucratic procedures, (iii) skills development and training, (iv) specification of output, (v) horizontal coordination mechanisms, and (vi) mission statements. Although these categories are indicative of what to look for, they seem to follow from a rather broad understanding of “capacities” (the authors do not define the concept). More recently, Howlett and Saguin (Citation2018) have proposed to use Wu, Howlett, and Ramesh’s (Citation2018) distinction between analytical, operational and political capacities to assess integrative capacities. However, in their (working) paper they are primarily interested in the relevance of these categories of capacity for different “forms” of policy integration (“policy mainstreaming”, “policy institutionalisation”, “policy coordination”, and “policy harmonisation”), and only give some examples of the precise ways in which the three capacities affect policy integration. therefore combines these examples with insights from the work of Jordan & Schout as well as of other policy integration scholars to synthesize some of the key capacity-related variables.

Table 1. Examples of capacities that are important for policy integration.

Importantly, although this overview presents some of the most recurring capacity-related preconditions, it is far from exhaustive; capacities at individual level are particularly underrepresented. Nevertheless, it provides a good starting point for assessing whether a governance system possesses the skills, competences, resources and structures that need to be in place for attempts at strengthening policy integration to have a chance of succeeding. That said, the presence of these capacities is important but insufficient by itself (cf. Peters Citation2015). Previous studies have shown that for policy integration to succeed, these capacities need to be accompanied by a second precondition: leadership.Footnote3

4.2. Integrative leadership

Together with policy capacity, leadership has been identified as the critical aspect of policy integration processes. It also proves the aspect that is most often lacking, and has for that reason been frequently recurring in policy integration studies to account for policy failure (Candel Citation2017; Bagnall et al. Citation2019). For example, studies of sustainable development governance and environmental policy integration have shown that although governments often do invest in capacities, lacks of leadership make that these remain ineffective, e.g. when environmental and economic goals conflict (Casado-Asensio and Steurer Citation2014, Citation2016). To be precise, there may be leaders or champions available, but these either prioritise other goals or lack the political resources to overcome resistance.

It may well be argued that any form of public leadership is integrative by definition, as leaders are tasked with guiding more or less varied groups of people in performing certain tasks and/or realizing a particular set of goals. Leaders play an important role in propagating ideas about what the organization is about or should be doing, which become ingrained in the structures of and individuals working in the organization (Peters, Erkkilä, and Von Maravić Citation2016, 100–01). That said, leadership scholars have coined the concept of integrative leadership to refer to the type of leadership that is necessary for governing crosscutting problems (for a review of the concept, see: Crosby and Bryson Citation2010). Crosby and Bryson (Citation2014, 57) define integrative leadership as “the work of integrating people, resources, and organizations across various boundaries to tackle complex public problems and achieve the common good.” This concept has strongly rooted in the collaborative governance literature. As collaborations are often voluntary and involve stakeholders with diverse interests, it is the role of integrative leaders to set the rules, empower weaker stakeholders, and facilitate deliberations and setting shared goals (Ansell Citation2012).

The collaborative governance and leadership literatures have provided various more precise insights into what it is that (some) leaders do that makes them contribute to integration. In his study of civic engagement in Seattle, Richard Page (Citation2010), for example, identified three “tactics”: (i) framing the agenda, e.g. by using frames that call attention to shared problems or the common good, (ii) convening stakeholders to govern collaboratively, e.g. through influencing the scope of participation and the exclusivity of the venue, and (iii) structuring deliberation, e.g. by establishing ground rules and norms. Similarly, Crosby and Bryson (Citation2014) identified nine different “practices” of integrative leadership, which they clustered in three categories: (i) diagnosing context, e.g. shaping and taking advantage of windows of opportunities, (ii) practices related to structure and process, e.g. influencing and authorizing decision-makers, and (iii) outcomes and accountabilities, e.g. assessing outcomes and managing results.

Even though the integrative leadership literature is strongly rooted in the collaborative governance literature, it is important to note that in principle (variations on) integrative leadership is not restricted to collaborative forms of governance. Peters (Citation2015, 142), for example, points out that leaders may also depend on hierarchy to steer behaviour towards concerted action. Peters (ibid.: 143) also stresses that whereas much of the literature tends to focus on high-level political leadership, the presence of integrative leadership at administrative levels is just as, and possibly even more, important:

[for concerted action] [t]o be successful the individuals at the top of government will have to motivate the second or third or even lower tiers of government to provide that necessary direction to the system of governing. The leaders for coordination may be located far down in the hierarchy and indeed may be at the very bottom of the organisations where collaboration and networking are the dominant models employed to produce the needed coordination.

4.3. A heuristic to judge chances of successful policy integration

Juxtaposing integrative capacity and leadership allows for distinguishing the different starting points that policymakers can find themselves in when they intend to strengthen policy integration, see . Different degrees of these variables may allow for pursuing different types of policy integration. As such, policymakers and others with an interest in promoting integrated policy approaches can use this heuristic to judge the feasibility of their intentions. Such an evaluation may show that policy integration ambitions are or are not realistic, and in case of the latter what conditions ought to be strengthened if one aims to persevere with these ambitions.

Table 2. Possibilities for pursuing different types of policy integration.

First, capacity and leadership may both be absent or low. If such a situation remains unchanged, there is no or only limited potential for strengthening policy integration. Instead, policy is made in specialized subsystems between which there is no or little attuning. Calls for higher levels of policy integration will not engender good will; as the problem at hand is not understood as crosscutting, organizations and individual decision-makers will feel threatened in their mandates. This has for example happened with calls to strengthen the integration between the EU's Common Agricultural Policy and adjacent domains such as environment and public health: when various stakeholders and commentators called for moving towards a broader Common Food Policy and for using some of the agricultural budget to address upcoming concerns (e.g. Fresco and Poppe Citation2016; iPES Food Citation2016), behind closed doors, EU agricultural policymakers’ responses proved rather defensive (cf. Candel Citation2016; Greer Citation2017). This is not to say that no integrative steps can be made at all. It may well be feasible and opportune to aim for lower levels of policy integration (see Section 2), for example by adjusting goals and instruments to address some of the most harmful externalities (Jordan and Halpin Citation2006).

A second possibility is that integrative capacities are sufficiently available but that there is insufficient integrative leadership at one or more levels. In such a case, there is only potential for administrative integration. Administrative integration refers to a state in which various subsystems are involved in dealing with a crosscutting issue, goals and instruments are integrated at relatively high levels in policy outputs, and various information-sharing and collaborative structures exist, but which eventually does not proceed beyond a profusion of good intentions. Decisively, due to a lack of leadership, efforts related to the crosscutting issue will come off worst when conflicting with other sectoral or crosscutting priorities, leaving policy integration largely a paper reality. This type of policy integration has been abundant in policy integration studies and has been considered one of the main reasons why, for example, environmental policy integration initiatives generally remain poorly implemented and hardly seem to result in improved environmental outcomes (Jordan and Lenschow Citation2010; Russel and Jordan Citation2010). Similar observations have been made for Policy Coherence for Development (PCD) initiatives. Carbone and Keijzer (Citation2016, 30), for example, conclude their discussion of PCD in the EU with the statement that “successful promotion of PCD is more than just having the right arguments and ensuring sufficient technical support, [it] is first and foremost a political undertaking.”

A third option involves the reverse situation: a high level of integrative leadership but low capacities. In this case there is (only) a potential for symbolic integration. Symbolic integration entails a situation in which (mostly political) leaders commit to an integrated approach to tackle a particular crosscutting problem, but capacities lag behind. This often shows in the adoption of ambitious agreements, manifestos, or high-level strategies that have considerable symbolic value but do not result in genuine changes within administrations. Compared to administrative integration, symbolic integration is much less costly in terms of resources needed. However, administrative integration arguably provides a firmer base for full policy integration, as it implies the presence of architectures, processes and skills that take a long time to develop. Examples of symbolic integration are less prevalent, because, as mentioned earlier, policy integration initiatives seem to more often lack leadership than capacities. It may be argued that many policy integration efforts related to sustainable development commitments, such as the Sustainable Development Goals, show characteristics of symbolic integration: they generally find wide and genuine resonance among leadership, but capacities often remain very limited and separated from mainstream policy processes (Casado-Asensio and Steurer Citation2014).

Lastly, when both integrative capacities and leadership are readily available, it becomes possible to pursue full policy integration. Full policy integration refers to a process of policy change in which all of the four dimensions of integration move towards higher or the highest levels, meaning that an integrative policy frame emerges, all relevant subsystems are involved, there is a set of overarching, coherent policy goals as well as a consistent mix of policy instruments (Howlett and Rayner Citation2007; Candel and Biesbroek Citation2016). In this type of policy integration, objectives and interventions related to the crosscutting issue do get prioritized over others in case of conflicts, and are implemented in line with policy design. As such, full policy integration is the type of integration that policymakers and scholars generally have in mind when calling for concerted actions. At the same time, clear examples of successful full policy integration seem relatively sparse, largely due to the aforementioned challenges. Various of the U.S. “boundary-spanning policy regimes” – around community empowerment, pollution abatement, drug criminalization, disability rights, welfare responsibility, and homeland security – and associated policy configurations discussed by Jochim and May (Citation2010) arguably fall within this category (but see: May, Jochim, and Sapotichne Citation2011).

Importantly, as with any typology, these four types of policy integration “merely” serve as analytical constructs. In practice, rather than a dichotomy between low and high, the availability of integrative capacities and leadership should be considered on a scale. In addition, the governance of crosscutting issues will often show characteristics of various types of policy integration depending on time and context. For example, it was already noticed before that environmental policy integration and sustainable development initiatives have been found to “suffer” from both administrative and symbolic policy integration.

5. Discussion

This article started with the question of when pursuing strengthened policy integration may be considered expedient. By discussing the most recurring pros and cons, it became clear that there can be various reasons for investing scarce reasons in policy integration, but, importantly, that there may also be grounds for not doing so. The latter often tend to be ignored, both in the scientific literature and in policy arenas. Judging the desirability of policy integration will for a large part depend on assessments of the feasibility of organizing integration within an political-administrative system. The heuristic presented in the previous section can provide some guidance in determining whether sufficient integrative leadership and capacities are present to allow for genuine integrative processes, i.e. whether there is the potential for full policy integration.

Whereas more reflexive decision-making about the expediency of strengthening policy integration may at times result in more modest, less resource-intensive ways of organizing interactions across subsystems, the argument should not be stretched by shunning ambitious integrative approaches at all times. As many of the most pressing challenges of the twenty-first century have undermined the problem-solving abilities of sectoral governance arrangements (Kettl Citation2006), not recognizing the need for policy integration can be dangerous when governing potentially destructive problems (Candel and Biesbroek Citation2016). Indeed, the disruptive effects of recent financial crises (Gieve and Provost Citation2012), or famines (Devereux Citation2009), are not for a small part explained by faltering coordination. For that reason, in spite of the rather critical perspective on policy integration in this article, the heuristic may actually be a helpful tool in efforts to strengthen integrated approaches to some of these critical concerns, including climate change, hunger, and economic instability.

Of course, the ideal of rational decision-making implicitly underlying the article's argument does not correspond with the much messier practices on the ground. Policy integration processes are subject to the same political dynamics as any kind of policy change, including organizational routines, turf wars, and clientelism (Peters Citation2015; Hartlapp Citation2016). In fact, even the question of what is to be integrated or requiring an integrated approach is often contested, as contending publics have separate agendas and problem perceptions (Jordan and Halpin Citation2006). That said, policymakers and stakeholders do at times engage in more reflexive deliberations about desired modes of governance and how to allocate scarce resources; the considerations laid out in this article may contribute to such reflections.

From a more scholarly perspective, the endeavour set out in this article gives rise to various follow-up questions and associated possible avenues of empirical research. First, although integrative leadership and capacities have been put forward as the key variables for explaining policy integration in the public policy literature, and therefore serve as the building blocks of the heuristic presented in this article, the supportive evidence base is relatively scarce and anecdotal. The heuristic can therefore also be used for hypothesis-testing purposes, i.e. to test the relationship between the two variables and the four types of policy integration. A more specific question about the capacities is whether particular stages of policy integration also require particular types or calibrations of capacities.

Second, as discussed in Section 2, the extent to which strengthened policy integration results in improved effectiveness remains contested. Although attribution problems make that assessing the influence of public policy in general is very challenging at best, avoiding this question altogether would be throwing away the baby with the bathwater. A promising direction, in this respect, is to move towards more comprehensive assessments and tracking of governments’ policy choices, and particularly the instruments they deploy (e.g. see: Ford et al. Citation2015). This would then permit more systematic comparisons of outputs with impacts (Knill and Tosun Citation2012, 292–93), for example allowing for better understandings of interactions in instrument mixes.

Third, whereas both this article as well as the broader policy integration scholarship generally take a rather generic approach to “policymaking”, distinguishing between policy formulation and implementation, i.e. programme management and service delivery, would provide a more refined understanding of policy integration dynamics and associated normative considerations. In this respect, it would be worthwhile to complement existing top-down policy integration studies with more qualitative empirical analyses of how pushes for policy integration are experienced at the level of middle management, street-level bureaucrats, and ultimate target groups (cf. Yanow Citation1996; Huttunen Citation2015). This would most likely open up additional perspectives on the desirability and feasibility of policy integration processes to the ones presented in this paper.

Lastly, in the above I argued that policy integration processes are highly political, and that judgments of the desirability of pursuing strengthened policy integration ultimately rely upon political weighing. So far, these “politics of policy integration” have remained relatively underexplored in the literature. Instead, many policy integration studies have tended to follow a rather instrumentalist perspective, e.g. assessing (barriers in) the mainstreaming of a particular crosscutting concern. Although valuable in itself, the risk of the dominance of this perspective is that policy integration has come to be seen as largely a technocratic endeavour. Paying more attention to questions of how integrative approaches emerge on the agenda, who pushes for these using what sort of strategies, and who wins and loses from integration, will allow for what Underdal (Citation1980) already called an “integrated” view on policy integration.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Jeroen J. L. Candel

Jeroen J. L. Candel works as an Assistant Professor at the Public Administration and Policy Group of Wageningen University, The Netherlands. He draws on public policy and public administration theories to study emerging forms of food and agricultural policy, both in European and developing country contexts. His previous work has been published in various leading journals, including Journal of European Public Policy, Policy Sciences, Environmental Science & Policy, Food Policy, and Food Security. In 2016, he was awarded the Van Poelje Award for his PhD dissertation, entitled ‘Putting Food on the Table: The European Union Governance of the Wicked Problem of Food Security’. Beside his research, he frequently advises policymakers and stakeholders and engages in the public debate.

Notes

1 The concepts of policy integration and coordination have been used interchangeably by many public administration and policy scholars (Tosun and Lang Citation2017). I approach policy integration as the attempt to align policy variables (e.g. goals and instruments) and coordination as alignment at polity-level (i.e. of institutional variables). As both are strongly interrelated, much of the argument deals with both challenges; however, for the sake of clarity of the argument I henceforth use the term policy integration.

2 Based on titles, keywords and abstracts.

3 Note that some scholars approach leadership as an element of capacity. In line with the policy integration literature I consider them as separate variables.

References

- Adelle, C., A. Jordan, and D. Benson. 2015. “The Role of Policy Networks in the Coordination of the European Union’s Economic and Environmental Interests: The Case of EU Mercury Policy.” Journal of European Integration 37 (4): 471–489. doi: 10.1080/07036337.2015.1004632

- Adelle, C., M. Pallemaerts, and J. Chiavari. 2009. Climate Change and Energy Security in Europe: Policy Integration and its Limits. Stockholm: Swedish Institute for European Policy Studies.

- Alons, G. 2017. “Environmental Policy Integration in the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy: Greening or Greenwashing?” Journal of European Public Policy 24 (11): 1604–1622. doi: 10.1080/13501763.2017.1334085

- Ansell, C. 2012. “Collaborative Governance.” In The Oxford Handbook of Governance, edited by D. Levi-Faur, 498–511. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bagnall, A.-M., D. Radley, R. Jones, P. Gately, J. Nobles, M. Van Dijk, J. Blackshaw, S. Montel, and P. Sahota. 2019. “Whole Systems Approaches to Obesity and Other Complex Public Health Challenges: A Systematic Review.” BMC Public Health 19 (1): 8. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-6274-z

- Bakvis, H. 2000. “Rebuilding Policy Capacity in the Era of the Fiscal Dividend: A Report from Canada.” Governance 13 (1): 71–103. doi: 10.1111/0952-1895.00124

- Biesbroek, R., and J. J. L. Candel. 2019. “Mechanisms for Policy (Dis)integration: Explaining Food Policy and Climate Change Adaptation Policy in the Netherlands.” Policy Sciences. doi:10.1007/s11077-019-09354-2.

- Biesbroek, G. R., C. J. A. M. Termeer, J. E. M. Klostermann, and P. Kabat. 2014. “Rethinking Barriers to Adaptation: Mechanism-Based Explanation of Impasses in the Governance of an Innovative Adaptation Measure.” Global Environmental Change 26: 108–118. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2014.04.004

- Briassoulis, H. 2004. “Policy Integration for Complex Policy Problems: What, Why and How.” Paper presentat at the Berlin Conference on the Human dimensions of Global environmental change: greening of policies – Interlinkages and policy integration, Berlin.

- Candel, J. J. L. 2016. Putting Food on the Table: The European Union Governance of the Wicked Problem of Food Security. PhD., Wageningen University.

- Candel, J. J. L. 2017. “Holy Grail or Inflated Expectations?” The Success and Failure of Integrated Policy Strategies. Policy Studies 38 (6): 519–552.

- Candel, J. J. L., and G. R. Biesbroek. 2016. “Toward a Processual Understanding of Policy Integration.” Policy Sciences 49 (3): 211–231. doi: 10.1007/s11077-016-9248-y

- Carbone, M., and N. Keijzer. 2016. “The European Union and Policy Coherence for Development: Reforms, Results, Resistance.” The European Journal of Development Research 28 (1): 30–43. doi: 10.1057/ejdr.2015.72

- Casado-Asensio, J., and R. Steurer. 2014. “Integrated Strategies on Sustainable Development, Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation in Western Europe: Communication Rather than Coordination.” Journal of Public Policy 34 (03): 437–473. doi: 10.1017/S0143814X13000287

- Casado-Asensio, J., and R. Steurer. 2016. “Bookkeeping Rather than Climate Policy Making: National Mitigation Strategies in Western Europe.” Climate Policy 16 (1): 88–108. doi: 10.1080/14693062.2014.980211

- Cejudo, G. M., and C. L. Michel. 2017. “Addressing Fragmented Government Action: Coordination, Coherence, and Integration.” Policy Sciences 50 (4): 745–767. doi: 10.1007/s11077-017-9281-5

- Crosby, B. C., and J. M. Bryson. 2010. “Integrative Leadership and the Creation and Maintenance of Cross-Sector Collaborations.” The Leadership Quarterly 21 (2): 211–230. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2010.01.003

- Crosby, B. C., and J. M. Bryson. 2014. “Public Integrative Leadership.” In The Oxford Handbook of Leadership and Organizations, edited by D. V. Day, 57–72. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Devereux, S. 2009. “Why Does Famine Persist in Africa?” Food Security 1 (1): 25–35. doi: 10.1007/s12571-008-0005-8

- Drimie, S., and S. Ruysenaar. 2010. “The Integrated Food Security Strategy of South Africa: An Institutional Analysis.” Agrekon 49 (3): 316–337. doi: 10.1080/03031853.2010.503377

- Dunlop, C. A. 2015. “Organizational Political Capacity as Learning.” Policy and Society 34 (3–4): 259–270. doi: 10.1016/j.polsoc.2015.09.007

- Dupuis, J., and G. R. Biesbroek. 2013. “Comparing Apples and Oranges: The Dependent Variable Problem in Comparing and Evaluating Climate Change Adaptation Policies.” Global Environmental Change 23 (6): 1476–1487. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2013.07.022

- Ford, J. D., L. Berrang-Ford, R. Biesbroek, M. Araos, S. E. Austin, and A. Lesnikowski. 2015. “Adaptation Tracking for a Post-2015 Climate Agreement.” Nature Climate Change 5 (11): 967–969. doi: 10.1038/nclimate2744

- Fresco, L. O., and K. J. Poppe. 2016. Towards a Common Agricultural and Food Policy. Wageningen: Wageningen University.

- Geerlings, H., and D. Stead. 2003. “The Integration of Land Use Planning, Transport and Environment in European Policy and Research.” Transport Policy 10 (3): 187–196. doi: 10.1016/S0967-070X(03)00020-9

- Gieve, J., and C. Provost. 2012. “Ideas and Coordination in Policymaking: The Financial Crisis of 2007–2009.” Governance 25 (1): 61–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0491.2011.01558.x

- Giljum, S., T. Hak, F. Hinterberger, and J. Kovanda. 2005. “Environmental Governance in the European Union: Strategies and Instruments for Absolute Decoupling.” International Journal of Sustainable Development 8 (1–2): 31–46. doi: 10.1504/IJSD.2005.007373

- Gleeson, D., D. Legge, D. O’neill, and M. Pfeffer. 2011. “Negotiating Tensions in Developing Organizational Policy Capacity: Comparative Lessons to be Drawn.” Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice 13 (3): 237–263.

- Greer, A. 2017. “Post-Exceptional Politics in Agriculture: An Examination of the 2013 Cap Reform.” Journal of European Public Policy 24 (11): 1585–1603. doi: 10.1080/13501763.2017.1334080

- Hartlapp, M. 2016. “Integrating Across Policy Sectors: How the Wider Public Impacts on the Drafting Process of EU Trans-Border Healthcare.” International Review of Administrative Sciences 84 (3): 486–502. doi: 10.1177/0020852316648225

- Hertin, J., and F. Berkhout. 2003. “Analysing Institutional Strategies for Environmental Policy Integration: The Case of EU Enterprise Policy.” Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 5 (1): 39–56. doi: 10.1080/15239080305603

- Hogl, K., D. Kleinschmit, and J. Rayner. 2016. “Achieving Policy Integration Across Fragmented Policy Domains: Forests, Agriculture, Climate and Energy.” Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy 34 (3): 399–414. doi: 10.1177/0263774X16644815

- Howlett, M. 2018. “Policy Analytical Capacity: The Supply and Demand for Policy Analysis in Government.” In Policy Capacity and Governance: Assessing Governmental Competences and Capabilities in Theory and Practice, edited by X. Wu, M. Howlett, and M. Ramesh, 49–66. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Howlett, M., and J. Rayner. 2007. “Design Principles for Policy Mixes: Cohesion and Coherence in ‘New Governance Arrangements’.” Policy and Society 26 (4): 1–18. doi: 10.1016/S1449-4035(07)70118-2

- Howlett, M., and K. Saguin. 2018. Policy Capacity for Policy Integration: Implications for the Sustainable Development Goals. Singapore: Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy Research – Paper No. 18-06.

- Huttunen, S. 2015. “Farming Practices and Experienced Policy Coherence in Agri-Environmental Policies: The Case of Land Clearing in Finland.” Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 17 (5): 573–592. doi: 10.1080/1523908X.2014.1003348

- Ipes Food. 2016. Why We Need a Common Food Policy for the EU: An Open Letter to Mr Jean-Claude Juncker, President Of The European Commission

- Jochim, A. E., and P. J. May. 2010. “Beyond Subsystems: Policy Regimes and Governance.” Policy Studies Journal 38 (2): 303–327. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0072.2010.00363.x

- Jones, B. D., and F. R. Baumgartner. 2005. The Politics of Attention: How Government Prioritzes Problems. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- Jones, M. D., and H. C. Jenkins-Smith. 2009. “Trans-Subsystem Dynamics: Policy Topography, Mass Opinion, and Policy Change.” Policy Studies Journal 37 (1): 37–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0072.2008.00294.x

- Jordan, G., and D. Halpin. 2006. “The Political Costs of Policy Coherence: Constructing a Rural Policy for Scotland.” Journal of Public Policy 26 (1): 21–41. doi: 10.1017/S0143814X06000456

- Jordan, A., and A. Lenschow. 2010. “Environmental Policy Integration: A State of the art Review.” Environmental Policy and Governance 20 (3): 147–158. doi: 10.1002/eet.539

- Jordan, A., and A. Schout. 2006. The Coordination of the European Union: Exploring the Capacities of Networked Governance. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Kettl, D. F. 2006. “Managing Boundaries in American Administration: The Collaboration Imperative.” Public Administration Review 66: 10–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6210.2006.00662.x

- Knill, C., and J. Tosun. 2012. Public Policy: A New Introduction. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Landau, M. C. F. P. D. J. A. 1969. “Redundancy, Rationality, and the Problem of Duplication and Overlap.” Public Administration Review 29 (4): 346–358. doi: 10.2307/973247

- May, P. J., A. E. Jochim, and J. Sapotichne. 2011. “Constructing Homeland Security: An Anemic Policy Regime.” Policy Studies Journal 39 (2): 285–307. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0072.2011.00408.x

- Metcalfe, L. 1994. “International Policy Co-Ordination and Public Management Reform.” International Review of Administrative Sciences 60 (2): 271–290. doi: 10.1177/002085239406000208

- Mickwitz, P., F. Aix, S. Beck, D. Carss, N. Ferrand, C. Gorg, A. Jensen, P. Kivimaa, C. Kuhlicke, and W. Kuindersma. 2009. Climate Policy Integration, Coherence and Governance. Vol. 2. Helsinki: Partnership for European Environmental Research.

- Mickwitz, P., and P. Kivimaa. 2007. “Evaluating Policy Integration: The Case of Policies for Environmentally Friendlier Technological Innovations.” Evaluation 13 (1): 68–86. doi: 10.1177/1356389007073682

- Mintzberg, H. 1983. Designing Effective Organizations: Structure in Fives. Englewood Cliffs, NY: Free Press.

- Nunan, F., A. Campbell, and E. Foster. 2012. “Environmental Mainstreaming: The Organisational Challenges of Policy Integration.” Public Administration and Development 32 (3): 262–277. doi: 10.1002/pad.1624

- Page, S. 2010. “Integrative Leadership for Collaborative Governance: Civic Engagement in Seattle.” The Leadership Quarterly 21 (2): 246–263. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2010.01.005

- Painter, M., and J. Pierre. 2005. “Unpacking Policy Capacity: Issues and Themes.” In Challenges to State Policy Capacity: Global Trends and Comparative Perspectives, edited by M. Painter and J. Pierre, 1–18. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Parsons, W. 2004. “Not Just Steering but Weaving: Relevant Knowledge and the Craft of Building Policy Capacity and Coherence.” Australian Journal of Public Administration 63 (1): 43–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8500.2004.00358.x

- Perri 6, Leat, D., K. Seltzer, and G. Stoker. 2002. Toward Holistic Government: A New Reform Agenda. London: Palgrave.

- Peters, B. G. 2015. Pursuing Horizontal Management: The Politics of Public Sector Coordination. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas.

- Peters, B. G. 2018. “The Challenge of Policy Coordination.” Policy Design and Practice 1 (1): 1–11. doi: 10.1080/25741292.2018.1437946

- Peters, B. G., T. Erkkilä, and P. Von Maravić. 2016. Public Administration: Research Strategies, Concepts, and Methods. New York: Routledge.

- Rayner, J., and M. Howlett. 2009. “Conclusion: Governance Arrangements and Policy Capacity for Policy Integration.” Policy and Society 28 (2): 165–172. doi: 10.1016/j.polsoc.2009.05.005

- Rees, T. 2005. “Reflections on the Uneven Development of Gender Mainstreaming in Europe.” International Feminist Journal of Politics 7 (4): 555–574. doi: 10.1080/14616740500284532

- Rocha, C. 2009. “Developments in National Policies for Food and Nutrition Security in Brazil.” Development Policy Review 27 (1): 51–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7679.2009.00435.x

- Ross, A., and S. Dovers. 2008. “Making the Harder Yards: Environmental Policy Integration in Australia.” Australian Journal of Public Administration 67 (3): 245–260. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8500.2008.00585.x

- Runhaar, H., B. Wilk, Å Persson, C. Uittenbroek, and C. Wamsler. 2018. “Mainstreaming Climate Adaptation: Taking Stock About “What Works” from Empirical Research Worldwide.” Regional Environmental Change 18 (4): 1201–1210. doi: 10.1007/s10113-017-1259-5

- Russel, D., and A. Jordan. 2010. “Environmental Policy Integration in the UK.” In Governance for the Environment: A Comparative Analysis of Environmental Policy Integration, 157–177. Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Steurer, R. 2007. “From Government Strategies to Strategic Public Management: An Exploratory Outlook on the Pursuit of Cross-Sectoral Policy Integration.” European Environment 17 (3): 201–214. doi: 10.1002/eet.452

- Termeer, C. J. A. M., A. Dewulf, G. Breeman, and S. J. Stiller. 2015. “Governance Capabilities for Dealing Wisely with Wicked Problems.” Administration and Society 47 (6): 680–710. doi: 10.1177/0095399712469195

- Tosun, J., and A. Lang. 2017. “Policy Integration: Mapping the Different Concepts.” Policy Studies 38 (6): 553–570. doi: 10.1080/01442872.2017.1339239

- Underdal, A. 1980. “Integrated Marine Policy: What? Why? How?” Marine Policy 4 (3): 159–169. doi: 10.1016/0308-597X(80)90051-2

- United Nations. 2015. Policy Integration in Government in Pursuit of the Sustainable Development Goals: Report of the Expert Group Meeting Held on 28 and 29 January 2015 at United Nations Headquarters, New York. New York: United Nations.

- Vince, J. 2015. “Integrated Policy Approaches and Policy Failure: The Case of Australia’s Oceans Policy.” Policy Sciences 48 (2): 159–180. doi: 10.1007/s11077-015-9215-z

- Woo, J. J., M. Ramesh, and M. Howlett. 2015. “Legitimation Capacity: System-Level Resources and Political Skills in Public Policy.” Policy and Society 34 (3–4): 271–283. doi: 10.1016/j.polsoc.2015.09.008

- Wu, X., M. Howlett, and M. Ramesh, eds. 2018. Policy Capacity and Governance. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Wu, X., M. Ramesh, and M. Howlett. 2015. “Policy Capacity: A Conceptual Framework for Understanding Policy Competences and Capabilities.” Policy and Society 34 (3–4): 165–171. doi: 10.1016/j.polsoc.2015.09.001

- Yanow, D. 1996. How Does a Policy Mean? Interpreting Policy and Organizational Actions. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.