ABSTRACT

How should political leaders be evaluated? This article reviews existing approaches and argues that they are insufficiently developed to map the more complex policy effects of political leaders, since they tend to focus on electoral and broader regime level outcomes. In response, it maps out a layered framework based on scientific realism. The layered approach argues that analysis should focus on the effects of leaders within societal structures, formal political institutions, the framing of policy problems as well as policy. The approach requires that we are sensitive to the structure and agency relationships between layers when identifying where leaders brought about policy and political change, as well as the effects on the international system and on other polities. It is proposed that the new approach will help to develop a more complete and nuanced understanding of the policy effects of leaders that will uncover their effects in hidden spaces as well as broader societal shifts.

President Trump had, unusually, been off-screen for over a week when he delivered a pre-recorded farewell speech on his last day in office (Cathey Citation2021). Following the storming of the Capitol building by a pro-Trump mob, the President had been stripped of his much-used Twitter account for incitement of violence and some media networks showed reluctance to cover his speech (Graziosi Citation2021; Twitter Inc. Citation2021). In the scripted video he claimed that as he concluded his time as the 45th President of the United States, he was “truly proud of what we have achieved together. We did what we came here to do – and so much more” (Whitehouse Citation2021b). A “Trump Administration Accomplishments” list was simultaneously published on the White House website, which included achievements such as an “unprecedented economic boom”, “massive deregulation,” “achieving a secure border” and “restoring American Leadership Abroad” (Whitehouse Citation2021a). The President had passed the largest corporate tax cuts on record, eliminated environmental regulations and withdrew from several multinational agreements, it was observed – perhaps markers of decisive change (Dimock and Gramlich Citation2021). Outgoing Attorney General William Barr commented in his resignation letter to the President: “Your record is all the more historic because you accomplished it in the face of relentless, implacable resistance” (Lemire Citation2021).

His Presidency was also marked by a hailstorm of criticism. Opponents pointed out that he was the first president to have been impeached twice and “departed in disgrace” following the attack on the Capitol (Haltiwanger Citation2021). Trump’s comments following white-supremacist violence in Charlottesville were criticized even by allies for “dividing Americans, not healing them” when he seemed to “draw some kind of equivalency” between white nationalists and counter-protesters (Clark Citation2021). He was “an emotionally overwrought, mercurial and unpredictable leader” who had created “a nervous breakdown of the executive power of the most powerful country in the world” (Woodward Citation2020, xix). His personality was described by critics as sociopathatic (Berger Citation2021) and narcissistic (Williams Citation2021). His time in office quickly revealed, critics claimed, “how little prepared the president and his team were when they stepped into the White House” (Oliva and Shanahan Citation2018).

A third possible characterization of the Presidency is that it made little lasting difference to America or the world. There was a lot of hot talk about “fire and fury” and late-night sensationalist tweets. But in the end, it could be argued that there was no major lasting policy change in many policy areas. Political change can be difficult to introduce because, as historical institutionalists have shown, policies, norms and institutions can be sticky in nature with inbuilt path dependencies (Bubak Citation2021; Pierson Citation2001). We should also be beware of the “Great Man” theory of history, not just because it attributes change entirely to men, but to a sole individual. If he had not emboldened far-right extremist groups such as Proud Boys and encouraged the attack on the Capitol building to contest the election result, then other individuals or groups may have taken the limelight to incite such actions. And what difference does a President make anyway? The legislation passed during his term in office could be just as quickly repealed. This third interpretation might also have it that the constitutional constraints on the president and persistence of democratic norms in American society were always strong enough to mean that, for all the talk of democracy being under threat in America, there was no lasting effect of the Presidency. The President and his actions mattered little. History and events played out largely as they would have done without Donald J. Trump.

Which of these three perspectives better describe the reality? How can we judge? This special issue asks:

− How can we characterize the nature of Donald Trump’s policies?

− To what extent did the Trump administration mark a radical departure in American government, policy and governance? Was the Trump administration transformationalist in any area?

− What were the consequences of the Trump administration’s policies? What effects did it really have in many areas of American domestic and international policy?

− What are the broader lessons of the nature of presidential power over policy in America and beyond?

Although there have been some mid-term assessments, answering these questions become easier now that his time in office has ended (for now). To provide an answer, this opening article argues, we need to consider a broader social science question: how can we measure and understand the effects of a political leader on policy? To help answer this, it is suggested that is important to retrace two key debates. Firstly, we need to consider some yardsticks of success for political leaders and presidents that have often been put forward to compare Trump against. Secondly, we need to consider the nature and extent of presidential power. What, after all, is realizable? Given the strengths and weaknesses of these existing approaches, a new framework is set out to provide a more holistic and layered way of capturing the impact of the presidency and assessing whether we should consider Trump as a transformationalist presidency – or one which ultimately had little substantive impact. The debate about the effects of Donald Trump is important for not only understanding his time in office, but hold important questions about the nature of the US Presidency, and the extent to which political leaders can be the sources of policy change in the wider world.

The article then introduces a new layered approach for understanding the policy effects of political leaders. It is argued that this can develop a more nuanced understanding of the policy effects of leaders that will uncover their effects in hidden spaces as well as broader societal shifts. This approach then broadly frames the remainder of the special issue which includes studies exploring the policy effects across many aspects of American society and beyond.

Configuring the independent variable: distinguishing leaders from their movements

One of the most important, but overlooked aspects of political research, Frederick A. Frey (Citation1985) warned nearly 40 years ago, is the problem of actor designation. That is, when describing a “political actor” who do we mean? In trying to evaluate the reach, power and effects of a political leader, we therefore need to ask who are they? How conceptually speaking should we define the independent variable of the study whose effects we are seeking to explore – the leader?

This is a simple question, for which there are multiple available answers. At one extreme, one approach is to identify the leadership as a single person. They are the unitary actor who are responsible for overall control and decision-making. It is common place to reduce leadership to the individual especially in presidential or presidentialized systems of governance where the media focuses attention on the individual face of an administration (Foley Citation2008; Poguntke and Webb Citation2005). At the other, we might envisage the leader as part of a leadership group in which there are several people, who take collective ownership and responsibility for decisions. The volume and complexity of decisions that need to be made requires delegation to respective cabinets, executive teams, ministers or generals. The study of core executives in different countries has produced a variety of sets of terminology for describing the leadership and arguments have been made for focussing on a “prime ministerial clique” “cabinet government” or “the court”. They have alternatively been seen to have wider connections with business, industrial-military complexes or oligarchs who may exert influence on the leader.

In the case of Donald Trump, there was so much change in his key leadership appointments that it is difficult to see much continuity in his leadership outside of himself. Key advisors who helped to form the Trump campaign such as Steve Bannon lasted only a year in the Whitehouse. Likewise, office-holders for the Defence Secretary, Chief of Staff and US Attorney General (BBC Citation2020). A conception of Trump’s leadership as being about the individual is partly consistent with viewing the administration as leadership by a celebrity – or media star (Street Citation2019) so has some advantage. It should be noted, however, Mike Pence, Mike Pompeo, Betsy DeVos, Ben Carson, Steve Mnuchin, Wilbur Ross, Sonny Perdue, and Elaine Chao were there as members of cabinet throughout the administration. Members of the Trump family seemed to also be part of the “Trump court” and Kellyanne Conway remained in post for a long period of time. Trump was reported to have his own ongoing business interests while serving as President and his connections to overseas governments was a continued source of discussion.

Leaders also need to be analytically distinguished from the wider social movement, cleavage or political philosophy for which they are come to represent and lead. In this case, the impact of Donald Trump needs to also be differentiated from “Trumpism”. The term “Trumpism” is contested. As Dimitrova (Citation2018) sets out, different approaches have defined it as a form of political rhetoric, an ideological movement of the radical right, and a style of governance. It has had a unique electoral support base, which has arisen from long-running economic and cultural transformations (Hochschild Citation2018; Norris and Inglehart Citation2019). From this perspective Donald Trump the person is a figurehead of a wider political philosophy and movement for social change. Importantly, many elements of what became Trumpism pre-dated Trump, coming in the form of the Tea Party (Gervais and Morris Citation2018). But Trumpism was given a new shape and form by Donald Trump and will live on beyond his term in office. There is therefore a dialectical relationship between the leader, and the properties of the wider movement that they lead. The movement may mutate, losing and gaining followers along the way, to take a different shape.

We begin by focussing primarily on the individual leader in this article and the special issue. This not to say that that their relationship with other actors, such as the members of the administration, industrial-military complex, business or oligarchs are not important in our understanding of leadership. Rather, all of these relationships are important and should be the object of study. The effects of the leader in creating new or evolving existing ideological movements, forms of rhetoric and styles of governance are all also important areas to be mapped. But by focussing on Donald Trump as an individual, we have a clear analytical basis from which to consider these questions and explore these relationships.

Existing frameworks

Measuring presidential policy impact

How should we evaluate the impact of leaders? There has been a broader methodological debate in recent years, with a variety of approaches emerging within but also outside of the US. The US has been a net exporter of scholarship on political leadership, with theoretical frameworks developed for understanding the US Presidency being used elsewhere (Byrne, Randall, and Theakston Citation2017; Theakston and Gill Citation2006). Given the centrality of the presidency for international public policy, there seems no reason to limit the range of approaches to Americanist studies and we should consider importing frameworks from elsewhere if appropriate.

One broad approach has been to assess the impact of leaders in terms of their electoral outcomes. The (neo-)statecraft approach, for example, maps and evaluates leaders in terms of whether they maintain office and establish a degree of governing competence in office (Buller and James Citation2012; James Citation2016, Citation2018). In the broadest sense, Trump had mixed fortunes here. He was the much-unexpected victor at the 2016 US primaries – not even expecting himself to win in November 2016, but still went on to claim the White House. Despite this, he would become the 9th president only to serve one term, and the first since George HW Bush in 1993, to not win a second term. His net approval ratings turned negative within days of taking over the White House, never to become positive again, and compared poorly to all other post-WWII leaders (FiveThirtyEight Citation2021). The weakness of focussing on power maintenance and electoral outcomes alone is that this only captures part, albeit an important part, of the effects that leaders have. In seeking to achieve re-election, they might develop policies which have a profound effect across a variety of areas. Leaders may also enter politics trying to achieve more altruistic goals than pure power pursuits rather than just re-elections (James Citation2018). A more holistic evaluation of the effects of leaders is therefore needed.

Another approach is to evaluate presidents by whether they were transformationalist in their effects on politics and society (Neustadt Citation1960). As Nye (Citation2013) notes, the term transformationalist is used in different ways, sometimes referring to leadership methods, sometimes outcomes. James McGregor Burns initially suggested that leaders were transformational when they used a method appealing to their followers to take higher values in the midst of ongoing conflict and crisis. If we are to take outcomes, however, then Franklin D. Roosevelt is often cited as an example of a transformational leader because of how he introduced transformational goals of social reform. In contrast, Bill Clinton’s reforms were more incremental. Making a difference and changing the path of history is assumed to be a sign of success, rather than maintaining the status quo. In Steven Skowronek (Citation2020)’s work, the key metric is whether leaders bring about change in the political regime. A regime consisted of the empowered political coalition in power and their governing commitments. Those orders included Federalist nationalism (1789–1800), Jeffersonian democracy (1800–1828), Jacksonian democracy (1828–1860) Republican nationalism (1860–1932), New Deal liberalism (1932–1980), before Reganism constructed a new political order. Leaders could be opposed or aligned with the current regime. Whether the regime is in a state of resilience or showing vulnerability will shape their opportunities to be transformationalist (Skowronek Citation2020, 83–86). A leader who is able to unpick elements of the incumbent regime and helped to construct a new one is deemed to have had considerable impact.

Such an approach provides the advantage of parsimony. The high-order impact of a leader across a society is summized. There are weaknesses though. Firstly, major political change is implicitly “rewarded” as “good” without a moral compass to evaluate the changes. Leadership could be transformationalist, but also fascist, racist, corrupt and cause devastating human and environmental suffering. As Skowronek (Citation2020, 171) notes:

The general impression is that transformational leadership is good leadership; it is certainly associated with great presidents. But there are presidents in our history who did the right thing at a critical moment whom we would not describe as transformational, and there are those whom we would describe as transformational who took actions we might well condemn. The notion that anything short of a political transformation represents a failure of leadership is a common conceit, but reflection reveals it as also a rather dangerous one.

Skowronek’s work is useful in another way, however, since it points to how leaders can be evaluated in terms of whether they were able to bring about substantial changes in the coalitions that underpin the defence of, and challenges to, the existing regime.Footnote1 Leaders may not be able to bring about major policy or regime changes themselves, but they could alter the balance of power within state institutions, political parties, political cleavages which will have policy effects in the future. This should form part of any policy assessment of the policy impact of leaders, and it will be returned to below. It should only be part of the assessment, however.

Rather than looking at transformationalist leadership, we could instead weigh leaders against their stated goals. In evaluating Trump, Hult (Citation2021) uses the administration’s stated goals as benchmarks to argue that the accomplishments included boosting conservative power on the federal courts and moving away from multilateral international relations. But the administration failed to bring about deregulatory policies that it hoped to pass and led to a decline in presidential capacity and trust in government. This approach is problematic, however, because there is clearly a risk that leaders may not be forthcoming about their real motives and goals. Strategic ambiguity in a leader stated goals may be a deliberate approach to interacting with the public, politicians and media. Politicians, and Trump especially, have often been accused of lying. Trump was described as the “biggest bullshitter to inhabit the modern presidency” (Kellner Citation2018, 89). Lying had advantages for Trump. It could generate publicity, controversy and attention, while also undermine established facts through friendly news outlets. There is also no role for a normative judgement about their desirability of the ambitions for wider society.

Leaders could alternatively be evaluated against the norms of their office. Pfiffner (Citation2021) argues that President Trump flouted the norms of the office of the Presidency which had come to be built up over many decades and centuries. These norms are not detailed in the Constitution but are the unwritten rules needed for democratic governance. Pfiffner claimed that Trump undermined these by, for example, a lack of civility in the election campaign, racism and xenophobia in office, lying, ignoring science and undermining the legitimacy of elections.

Other approaches include the examination of the personality of the leader, but this says more about the inputs into the political system that leaders provide, and only consider policy outcomes in so far as they can be explained by the personal characteristics of the leader. Fred I. Greenstein (Citation2000, Citation2009, Citation1988) argued that there are six core characteristics against presidents could be evaluated against. These were their proficiency as public communicator, their organizational capacity, their political skill, their public policy vision, cognitive style and emotional intelligence. Greenstein sadly died in 2018 and did not get his wish to “last long enough to write this one up” and only said that his “presidency is fascinating to a scholar of leadership because it’s so different from anything else” (Seelye Citation2018). But he scored highly on a Psychopathic Personality Inventory Index (Oxford University Citation2016) and there has been plenty of further psycho-analysis of Trump and whether he had the attributes required for the Presidency (Renshon Citation2020).

There is then the approach of the historian and the biographer. Rather than seeking to directly evaluate a leader using a specific set of abstract criteria, the aim is to describe and understand and provide more nuanced assessments.

Each of these approaches have considerable advantages and narrow the focus in a way that is useful for the analytical problem at hand. Should one wish to consider the wider effects of Presidency, however, then an alternative is needed. The US President has scope to have many direct and indirect ripple butterfly effects across a variety of policy areas around the world. Our lens should therefore be wide to capture this in a fuller resolution.

Measuring presidential power

The puzzle of how to evaluate a Presidency must be connected to the debate on the power that they effectively have. If a leader is deemed to have a rudderless set of levers which are incapable of bringing about change, then how can their term be criticized for not bringing or preventing change? How powerful are Presidents? Can they make a decisive difference?

There are a number of existing approaches to answering this part of the question. One is to focus on the formal constitutional powers that leaders are granted. In the context of US Presidents, Neustadt (Citation1960) pointed to how there were severe constitutional constraints on the leader which made them more reliant on negotiation around Capitol Hill, whereas modern scholars have pointed that unilateral action can be important. Arthur Schlesinger Jr. (Citation2004) warned, meanwhile, of the threat of the imperial presidency. There could be a potential abuse of presidential prerogative during national emergencies because of the war powers granted to the present and the widespread use of governmental secrecy. The president could therefore exceed the constitutional role that it was supposed to fulfil.

In the comparative literature, presidents are contrasted with prime ministers in the scope of their formal constitutional powers. Prime ministers often have the powers to set the legislative agenda directly. Presidents, however, are forced to respond via their veto power. This has led to the development of cross-national league tables of presidential power. These consider, for example, whether presidents have legislative veto powers, can issue decrees, have exclusive rights to introduce legislation or have budgetary powers (Doyle Citation2020; Metcalf Citation2000; Shugart and Carey Citation1992). For example, Doyle and Elgie (Citation2016) developed scores for presidential power for 116 countries at 181 timepoints. The US Presidential system ranked 105th of the 181 presidential systems. In other words, US presidents hardy hold the strongest of presidential positions.

Alternatively, the power of Presidents has been framed by their location in political time. Skowronek points out that power is different to authority – and leaders of similar parties and political persuasions might have much variation in their level of authority while still holding the same office. Presidents need to be considered in their place in political time and whether they are aligned or opposed to the existing political regime or order. Trump, writes Skowronek, was a late affiliate with the Reaganite political order, an order under considerable pressure with a divided Republican party, which made governing difficult. Affiliated leaders need to defend and support the existing order, but paradoxically present themselves as innovators. His position in political time therefore granted him little authority.

A key advantage of this regime history approach is that it helps to consider the interplay of structure and agency, but does reduce the understanding of structure to the leader’s relationship with the regime. This is reductionist and eliminates the more complex and varied opportunities and constraints that they have in a wider variety of policy areas. There are a wide set of areas where a leader could have an impact, especially in the case of the US because of the power that the US has traditionally had within the global international system. To what extent are there constraints on their ability to bring policy change on the nature of democracy? Capitalism? Covid-19? The environment? China? China’s environmental policy? Arguably, the relationship with the political order and place in political time says something very important, but not everything.

Mapping the policy effects of leaders: a layered policy process approach

To build a more overarching framework for policy impact, identifies three layers where the leader might affect change, which are overlapping in nature. This framework is underpinned by a scientific and critical realist understanding of the social sciences (Sayer Citation2010). This is a methodological orientation, built from the philosophy of the social sciences, which “steers a path between empiricist and constructivist accounts of scientific explanation” (Pawson Citation2006, 17). Key assumptions include that:

− The world exists independent of our knowledge it. Policies and policy problems cannot be reduced to ideational constructs as interpretivist policy analysis suggest (Yanow Citation2007) since, although ideational domain is also important, they have a material reality. Leaders may create myths (Pike and Diamond Citation2021) but also affect the real-world distribution of resources. Poverty, for example, is both a material policy problem, rather than one which is simply ideationally constructed. The narration of “poverty” as a policy problem can shape policy responses and can also have some effects on how individuals experience it – but the material inaccessibility to resources exists independent of our knowledge of it and this can shape, but not determine, the nature of policy problems.

− A stratified conception of reality. There are three distinct domains of reality. The empirical domain consists of the observable experiences that individuals can observe and record. The actual domain consists of events, which may often be unobservable to the researcher. The real domain, however, consists of the generative mechanisms and causal structures that influence events and experiences but may not be observable themselves. The sources of policy change cannot therefore be read from pure observation and a deeper analysis of the sociological mechanisms that influence outcomes is therefore needed.

− A generative model of causation. Realists seek to explain causation and identify regularities through the interaction of objects, agents and structures. Causation can't be identified or ruled out by trying to observe the regularity of events alone in the empirical domain, however. The non-occurrence of events may be for a variety of reasons, given the complexity of social life and multi-layered nature of reality.

− Societal betterment. Researchers are not independent of the world they study and the aim of social science is to “develop our understandings and reduce illusion” (Sayer Citation2010, 169). This learning is therefore itself a generative force in the world, which should be used for social betterment and emancipation (Sayer Citation2010, 169–173).

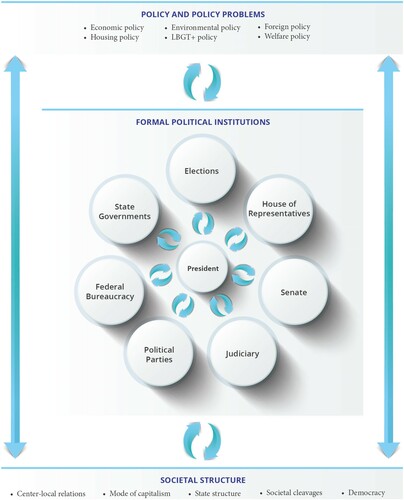

A layered nature of social reality has direct consequences for understanding the multitude of areas in which leaders have affects and effects. The three-tiered approach suggested here is introduced in layers.

Societal structure

At the broadest possible level, signified as being at the base of the pyramid in , is the societal or social structure, which are the broader set of human relationships and institutionalized patterns of behaviour in society. These might be economic, political, ideational or social relationships. Leaders who alter these would bring about major shifts in the nature of the society and state. This is likely be rare in the US, given that terms of office are limited to eight years. However, major political change can occur rapidly and unexpectedly – leaders may also set their countries on paths to incremental change or can act to consolidate existing orders.

The socio-economic social structure for most contemporary societies is capitalist, after the end of the Cold War saw the end of the Soviet Union and communist societies, and feudal bartering systems are thought to be long gone. Divergent varieties of capitalism are often differentiated, however, with distinctions often made between liberal market and coordinated market economies (Soskice and Hall Citation2001). Elsewhere, regulation theorists have alternatively distinguished between accumulation regimes. They argue that capitalism can have periods of rapid growth but also face endemic and periodic crises. Accumulation regimes are the short-term socio-temporal fixes to provide societal stability. Aglietta (Citation2000) argued that the US had an accumulation regime from the end of World War II to the late 1960s known as Fordism. This involved a more Keynesian welfare stare and unionized political system, which compared to Europe, was still less welfarist in nature. This went into crisis, however, with declining profits, productivity and growth. This was also the experience of many other Western industrialized economies, who searched for a post-Fordist regime, and often settled on increased neo-liberalism. Economies were then opened up, globalized and an emphasis put on the “knowledge-based economy” as engines for growth. But these also experienced political and economic pressures and contradictions such as rising inequality, crises emanating from unregulated financial markets and indebtedness between states (Foster and Magdoff Citation2009; Jessop Citation2017; Thompson Citation2007). Few leaders made decisive changes to these broad developments – and the role of individuals might be too easily stated. But the contributions of Roosevelt and Reagan were often held up as being significant in shaping the US form of capitalism.

Social structures can also be separated by the extent to which they are democratic. The long march of history has been towards the advancement of democracy worldwide (Huntington Citation1993), but there has been recent evidence of democratic backsliding (Mechkova, Lührmann, and Lindberg Citation2017). The US is often categorized as an early democratizer, which became democratic during the first wave of democratization as it gained independence from Britain (Huntington Citation1993), but civil rights legislation was not passed until the 1960s outlawing discriminatory practices. Racial and ethnic minority political rights continue to be unrealized (Mcclain Citation2021). Other inequalities are also inbuilt into societies such as those centred on gender (Lovenduski Citation2005; Snipp and Cheung Citation2016).

Societies can also be structured into cleavages based on material antagonistic relations, and/or the consolidation of political values into opposed groups. Real material antagonisms may shape political values but the process can also be multi-directional. Lipset and Rokkan (Citation1967) classically pointed out that these cleavages might be crystallized around a left-right dichotomy, but they might also include cleavages between the church and state, centre versus periphery or agrarian versus periphery. Alternatives might also include those based on ethnicity, tribe, religion. More recently, it has been argued, some societies may have become separated between liberal-pluralist and authoritarian-populist (Norris and Inglehart Citation2019). These are important themselves, but societies cleavages can also serve as the basis of coalitions that underpin political orders and policy regimes.

The nature of centre-local relations are also structural in nature. The relationship could be lopsided with capital cities with entrenched power over the outer-regions, the opposite might be the case. This is more than just administrative capacity or the allocation of formal decision-making because identity, cultural traditions and economic resources are important too (Bulpitt Citation1983).

Leaders can have effects on each of these domains of a polity, to a greater or lesser degree. They could contribute towards the stability and prosperity of the social structure or create tensions; undermine or rejuvenate democracy; open political cleavages or resolve them; maintain centre-local relations or unsettle them. Whatever they do has important consequences for the second and third layers and should therefore be under study.

2. Formal political institutions

Political institutions are ubiquitous, as new institutionalists tell us. Formal political institutions, however, are the sites where politics and power plays out that provide a direct steer in setting policy. Alongside the executive, they include the legislature, judiciary and bureaucracy of the state. Each plays a central role in deliberating, bargaining, setting and adjudicating policies and contains balances of power within them. A key formal institution is also the practice of elections which provide citizens with a way of shaping policy by choosing their representatives. Political parties provide the mechanism for leaders and candidate to contest elections.

This is the layer where the leader is formally located. They have considerable scope to shape and affect policy by trying to initiate new policies or repeal old ones. Their interactions with these institutions can determine how successful they are. Working the Capitol Hill community is often claimed to be a key leadership skill for Presidents (Neustadt Citation1960) and they can have varied degree of success (Edwards Citation1985). They can, however, shape the nature of formal institutions themselves. The US President can make significant changes to the US Supreme Court through their power of appointment when vacancies become available. Whether they broker a partisan or bipartisan approach to their relationship with the Senate and the House of Representatives can have a lasting effect on the norms of interaction. They can shape the parties for which they win the presidential election nomination and obviously also the elections themselves. They can also shape the nature of territorial relations – the nature of power between the federal and state levels of government.

The study of the effects of leaders on these institutions are often not considered within the domain of policy studies – and are often studied separately in sub-disciplines and journals of comparative politics, legislative studies and the like. However, in so far as a policy is, at the base, “a set of ideas or plans that is used as a basis for making decisions” (Collins Citation2021) leaders will have explicit or unconscious policies towards other key political institutions. It is therefore possible and important to discuss the Donald Trump’s, or any other leaders’ policy towards the judiciary, congress, and their own political party. Did leaders successfully navigate policies within them? Did they change the balance of power with them? Did they change the nature of the institutions themselves?

3. Policy and policy problems

The third domain where leaders have effects are on what we might conventionally call policies and policy problems. Policy sciences and public administration commonly identify the conventional policy areas to include those such as the economy and welfare, which are included in . Psephologists argue that it is often “the economy stupid” and that there are valence issues which define the outcomes of electoral events. These valence issues tend to dominate media coverage, undergraduate textbooks and research funding streams. What constitutes the “most important” policy area and even a policy problem are, of course, the result of wider narrative framing, agenda setting and political forces. Policy areas such as LBGT+ rights are amongst those often receiving less attention (Pepin-Neff Citation2021). Those identified in are therefore listed alphabetically, without rank, and are obviously illustrate rather than exhaustive.

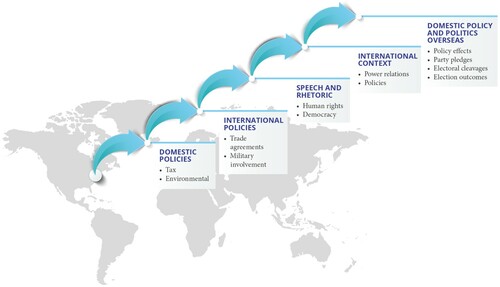

Internationalization

Analyses of the effects of political leaders often concentrate on their domestic effects, but they can have profound effects outside of the national borders. This is especially the case when the leader is the head of state of a global superpower. There has been a longstanding debate about whether the US has been in decline, given the rise of other states (Layne Citation2009). A framework for identifying the effects of leaders can help to contribute towards this debate by mapping the possible directions and nature of influence and then assessing it for each given leader.

identifies a number of pathways of impact for a political leader. Domestic policies set within the national ecosystem themselves may have a profound impact outside of national borders. The effect might be direct. Changes made to corporate tax rate might, for example, lead companies to relocate from other polities. The effect could also be signalling. Should a state lower corporation tax then other countries may respond in competition – but also because a norm has been set about the acceptability of such a change. Leaders may also shape their states’ international policies such as whether to have trade agreements with other states and whether to commit to military involvement. Speech and rhetoric can also have important causal effects by signalling, for example, the value of democracy and human rights in the world.

These actions could shape the broader international context by determining the power between states, the dynamics of the international system and the policies that are agreed to and become international law through bodies such as the UN, NATO and WHO. But leaders can also shape the domestic politics and policy in overseas states. Overseas leaders may gain inspiration and be emboldened by the electoral fortunes by counter-parts or may mimic their policies through processes of policy transfer (Marsh and Evans Citation2012a, Citation2012b).

These relationships are not unidirectional and their strength should be subject to scrutiny and evaluation through further research in a world that became ever globalized informationally. They certainly are not exhaustive.

Interconnectivity, structure and agency

The three layers provide a heuristic way of identifying the different effects of leaders but they are all closely and interactively connected. Policies and policy problems may change as a result of changes in political institutions. Policy problems may occur as a result of the nature of the societal structure. The nature of the societal structure can also frame what comes to be seen as a policy problem. Policies passed by political institutions can affect the nature of the societal structure. Changes to political institutions can affect the prospects of policies changing and serve as barriers or accelerants to societal change. There is therefore an endless web of interactions, as illustrated by . The effects caused by the leader, in this case, the president is therefore only one of the causal forces in the policy process.

The nature of this interconnectivity can be better understood through a structure and agency approach, which critical and scientific realism helps to illuminate. The strategic relational approach is one way of understanding cause and effect in the world which has been premised on scientific and critical realism. This was developed by Bob Jessop to overcome contradictions in the Marxist analysis of the state (Jessop Citation1990), but also used by Colin Hay (Citation2002, 115–134; Citation1996). The SRA involves examining “how a given structure may privilege some actors, some identities, some strategies, some spatial and temporal horizons, some actions over others” (Jessop Citation2001, 1223). Actors find themselves in strategically selective environments that favour certain strategies over others as a means to realize a given set of intentions or preferences. There is no level playing field. Strategically selective environments, however, do not determine outcomes because agents are reflexive actors capable of strategic learning. As Jessop put it, they can:

orient their strategies and tactics in the light of their understanding of the current conjuncture and their “feel for the game". (Jessop Citation2001, 1224)

Points of departure

The approach therefore departs from traditional theories of the policy process. Firstly, it sees the policy process less as a rationalistic cycle as it is commonly presented – most notably in stages. Secondly, it is centred around the political leader at the apex of the political system. It does not assume that they are all powerful in being able to institute policy change across the system, or even the most powerful. Rather, it is a lens for attempting to determine the extent to which they are able to alter policy, given the confluence of other sources of political change. Thirdly, the approach is anchored in critical/scientific realism rather than positivist or interpretivist traditions.

The special issue ahead

This introductory article has so far introduced the effects that the leader could have within a layered policy process. The articles which comprise the special issue then explore the nature of Donald Trump’s policies, the extent to which they involved change, and the effects that Donald Trump had to help us more fully understand his place in history and whether he represented a critical juncture in American politics and policy. They also help us to understand the nature of presidential power and strategically selective environment in which the Trump administration found itself. In doing so, they also say something important about the nature of the social structure, institutions and policy in American society.

The coverage is not exhaustive. Not every area where the administration had an imprint could be included, but there is extensive coverage nonetheless. Although the framework above encourages a stronger normative position on the presidency than some social scientists may usually take, no normative position is set out and the authors were free to make their own assessment. The conclusion then returns to the questions set out in this introduction in the light of the cases.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Christopher Byrne, Mònica Clua-Losada and colleagues in the University of East Anglia Politics, Media and International Relations Research group for comments on an earlier version of this paper. All errors remain the responsibility of the author.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Toby S. James

Toby S. James is Professor of Politics and Public Policy at the University of East Anglia. His previous books on political leadership includes co-edited volumes on British Labour Leaders and British Conservative Leaders (both Biteback, 2015). He has also published extensively on electoral integrity and is the Deputy Director of the Electoral Integrity Project. He is currently Editor-in-Chief of Policy Studies.

Notes

1 I am grateful to Christopher Burn for this point.

2 The SRA is simplified here for the purposes of space. There are a greater number of moments in dialectical relationship between structure and agency. See: Jessop (Citation2001).

References

- Aglietta, Michel. 2000. A Theory of Capitalist Regulation: The US Experience. New York, NY: Verso.

- BBC. 2020. “The White House Revolving Door: Who’s Gone?” BBC News, December 15, 2020. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-us-canada-39826934.

- Berger, Daniel. 2021. “Donald Trump: Profile of a Sociopath.” Huffington Post, March 8, 2016. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/trump-profile-of-a-sociopath_b_11318128.

- Bubak, Oldrich. 2021. “The Structure-in-Evolution Approach: A Unified View of Evolutionary Change in Policy Systems.” Policy Studies, 1–20. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/https://doi.org/10.1080/01442872.2021.1908534.

- Buller, Jim, and Toby S. James. 2012. “Statecraft and the Assessment of National Political Leaders: The Case of New Labour and Tony Blair.” The British Journal of Politics & International Relations 14 (4): 534–555.

- Bulpitt, Jim. 1983. Territory and Power in the United Kingdom. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Byrne, Chris, Nick Randall, and Kevin Theakston. 2017. “Evaluating British Prime Ministerial Performance: David Cameron's Premiership in Political Time.” British Journal of Politics and International Relations 19 (1): 202–220.

- Cathey, Libby. 2021. “Trump Releases Taped ‘Farewell Address.’” ABC News, January 19, 2021. https://abcnews.go.com/Politics/trump-releases-taped-farewell-address/story?id=75351020.

- Clark, Dartunorro. 2021. “Democratic, Republican Lawmakers Decry Trump's Latest Charlottesville Remarks.” NBC News, August 15, 2017. https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/white-house/not-my-president-lawmakers-decry-trump-s-latest-charlottesville-remarks-n793021.

- Collins. 2021. “Collins Dictionary.” p.

- Dimitrova, Anna. 2018. “The Risks of Trumpism.” In Europe – Against the Tide, edited by Matthias Waechter, 139–146. Nomos.

- Dimock, Michael, and John Gramlich. 2021. “How America Changed During Donald Trump’s Presidency.” Pew Research Center, January 29, 2021. https://www.pewresearch.org/2021/01/29/how-america-changed-during-donald-trumps-presidency/.

- Doyle, David. 2020. “Measuring Presidential and Prime Ministerial Power.” In The Oxford Handbook of Political Executives, edited by Robert Elgie, Rudy B. Andeweg, Ludger Helms, Juliet Kaarbo, and Ferdinand Müller-Rommel, 382–401. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Doyle, David, and Robert Elgie. 2016. “Maximizing the Reliability of Cross-National Measures of Presidential Power.” British Journal of Political Science 46 (4): 731–741.

- Edwards, George C. 1985. “Measuring Presidential Success in Congress: Alternative Approaches.” The Journal of Politics 47 (2): 667–685.

- FiveThirtyEight. 2021. How Unpopular Is Donald Trump?, https://projects.fivethirtyeight.com/trump-approval-ratings/.

- Foley, Michael. 2008. “The Presidential Dynamics of Leadership Decline in Contemporary British Politics: the Illustrative Case of Tony Blair.” Contemporary Politics 14 (1): 53–69.

- Foster, John Bellamy, and Fred Magdoff. 2009. The Great Financial Crisis: Causes and Consequences. New York, NY: NYU Press.

- Frey, Frederick W. 1985. “The Problem of Actor Designation in Political Analysis.” Comparative Politics 17 (2): 127–152.

- Gervais, Bryan T, and Irwin L Morris. 2018. Reactionary Republicanism: How the tea Party in the House Paved the way for Trump's Victory. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Graziosi, Graig. 2021. “Trump Farewell Video: Major Networks Boycott President’s Speech.” Independent, January 19, 2021. https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/americas/us-politics/trump-farewell-video-speech-today-b1789745.html.

- Greenstein, P. I. 1988. Leadership in the Modern Presidency. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

- Greenstein, Fred I. 2000. “The Qualities of Effective Presidents: An Overview from FDR to Bill Clinton.” Presidential Studies Quarterly 30 (1): 178–185.

- Greenstein, Fred I. 2009. The Presidential Difference: Leadership Style from FDR to Barack Obama. 3rd ed. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Haltiwanger, John. 2021. “Trump's Biggest Accomplishments and Failures from his 1-term Presidency.” Business Insider, January 20, 2021. https://www.businessinsider.com/trump-biggest-accomplishments-and-failures-heading-into-2020-2019-12?r=US&IR=T.

- Hay, Colin. 1996. Re-stating Social and Political Change. Buckingham: Open University Press.

- Hay, C. 2002. Political Analysis. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hochschild, Arlie Russell. 2018. Strangers in Their own Land: Anger and Mourning on the American Right. New York, NY: The New Press.

- Hult, Karen M. 2021. “Assessing the Trump White House.” Presidential Studies Quarterly 51 (1): 35–50.

- Huntington, Samuel. 1993. The Third Wave: Democratization in the Late Twentieth Century. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

- James, Toby S. 2016. “Neo-statecraft, Historical Institutionalism and Institutional Change.” Government and Opposition 51 (1): 84–110.

- James, Toby S. 2018. “Political Leadership as Statecraft? Aligning Theory with Praxis in Conversation with British Party Leaders.” The British Journal of Politics and International Relations 20 (3): 555–572.

- Jessop, B. 1990. State Theory: Putting the Capitalist State in its Place. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Jessop, Bob. 2001. “Institutional re(Turns) and the Strategic – Relational Approach.” Environment and Planning A 33: 1213–1235.

- Jessop, Bob. 2017. “The Organic Crisis of the British State: Putting Brexit in its Place.” Globalizations 14 (1): 133–141.

- Kellner, Douglas. 2018. “Donald Trump and the Politics of Lying.” In Post-Truth, Fake News: Viral Modernity & Higher Education, edited by Michael A. Peters, Sharon Rider, Mats Hyvönen, and Tina Besley, 89–100. Singapore: Springer Singapore.

- Layne, Christopher. 2009. “The Waning of US Hegemony—Myth or Reality? A Review Essay.” International Security 34 (1): 147–172.

- Lemire, Jonathan. 2021. “Trump Administration Cushions the President in Praise as his Term Draws to a Close.” Global News, December 20, 2020. https://globalnews.ca/news/7533843/trump-praise-presidency-ending/.

- Lipset, Seymour Martin, and Stein Rokkan. 1967. Party Systems and Voter Alignments: Cross-National Perspectives. New York: Free press.

- Lovenduski, Joni. 2005. Feminizing Politics. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

- Marsh, David, and Mark Evans. 2012a. “Policy Transfer: Coming of age and Learning from the Experience.” Policy Studies 33 (6): 477–481.

- Marsh, David, and Mark Evans. 2012b. “Policy Transfer: Into the Future, Learning from the Past.” Policy Studies 33 (6): 587–591.

- Mcclain, Paula D. 2021. Can We All Get Along?: Racial And Ethnic Minorities In American Politics. London: Routledge.

- Mechkova, Valeriya, Anna Lührmann, and Staffan I Lindberg. 2017. “How Much Democratic Backsliding?” Journal of Democracy 28 (4): 162–169.

- Metcalf, Lee Kendall. 2000. “Measuring Presidential Power.” Comparative Political Studies 33 (5): 660–685.

- Neustadt, R. 1960. Presidential Power: The Politics of Leadership. New York: Wiley.

- Norris, Pippa, and Ronald Inglehart. 2019. Cultural Backlash: the Rise of Authoritarianism-Populism. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Nye, Joseph S. 2013. “Transformational and Transactional Presidents.” Leadership 10 (1): 118–124.

- Oliva, Mara, and Mark Shanahan. 2018. “Introduction.” In The Trump Presidency: From Campaign Trail to World Stage, edited by Mara Oliva and Mark Shanahan, 1–15. CT: Springer.

- Oxford University. 2016. “Presidential Candidates May Be Psychopaths – but that could be a Good Thing.” https://www.ox.ac.uk/news/2016-08-23-presidential-candidates-may-be-psychopaths-%E2%80%93-could-be-good-thing.

- Pawson, Ray. 2006. Evidence-based Policy. London: Sage.

- Pepin-Neff, Christopher. 2021. LGBTQ Lobbying in the United States. London: Routledge.

- Pfiffner, James P. 2021. “Donald Trump and the Norms of the Presidency.” Presidential Studies Quarterly 51 (1): 96–124.

- Pierson, Paul. 2001. The new Politics of the Welfare State. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Pike, Karl, and Patrick Diamond. 2021. “Myth and Meaning: ‘Corbynism’ and the Interpretation of Political Leadership.” The British Journal of Politics and International Relations 1369148121996252. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/https://doi.org/10.1177/1369148121996252.

- Poguntke, T., and P. Webb. 2005. The Presidentialization of Politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Renshon, Stanley Allen. 2020. The Real Psychology of the Trump Presidency. Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

- Sayer, A. 2010. Method in Social Sciences. Revised 2nd ed. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Schlesinger, Arthur M. 2004. The Imperial Presidency. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company.

- Seelye, Katharine Q. 2018. “Fred Greenstein, 88, Dies; Political ‘Psychologist’ Assessed Presidents.” New York Times, December 14, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/12/14/obituaries/fred-greenstein-dead.html.

- Shugart, Matthew Soberg, and John M Carey. 1992. Presidents and Assemblies: Constitutional Design and Electoral Dynamics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Skowronek, Stephen. 2020. Presidential Leadership in Political Time: Reprise and Reappraisal. 3rd ed. Lawrence: The University Press of Kansas.

- Snipp, C. Matthew, and Sin Yi Cheung. 2016. “Changes in Racial and Gender Inequality Since 1970.” The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 663 (1): 80–98.

- Soskice, David W, and Peter A Hall. 2001. Varieties of Capitalism: The Institutional Foundations of Comparative Advantage. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Street, John. 2019. “What is Donald Trump? Forms of ‘Celebrity’ in Celebrity Politics.” Political Studies Review 17 (1): 3–13.

- Theakston, K., and M. Gill. 2006. “Ranking 20th Century British Prime Ministers.” British Journal of Politics and International Relations 8: 193–213.

- Thompson, Helen. 2007. “Debt and Power: The United States’ Debt in Historical Perspective.” International Relations 21 (3): 305–323.

- Twitter Inc. 2021. “Permanent Suspension of @realDonaldTrump.” Twitter Blog, January 8, 2021. https://blog.twitter.com/en_us/topics/company/2020/suspension.html.

- Whitehouse. 2021a. “As of January 2021: Trump Administration Accomplishments.” https://www.whitehouse.gov/trump-administration-accomplishments/.

- Whitehouse. 2021b. “Remarks by President Trump In Farewell Address to the Nation.” https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/remarks-president-trump-farewell-address-nation/.

- Williams, Zoe. 2021. “‘Is Trump a psychopath? I’d call him a Narcissist.’” Guardian, August 23, 2016. https://www.theguardian.com/science/shortcuts/2016/aug/23/donald-trump-psychopath-hitler.

- Woodward, Bob. 2020. Rage. London: Simon & Schuster.

- Yanow, Dvora. 2007. “Interpretation in Policy Analysis: On Methods and Practice.” Critical Policy Studies 1 (1): 110–122.