ABSTRACT

Integrating horizontal perspectives in sectoral policies is an increasingly popular way to address complex, societal problems like climate change and gender inequality. Policy evaluation can contribute to policy integration by shedding light on the coherence between sectoral goals and the mitigation or solution of the problem in question – including possible synergies and/or conflicts. To denote this evaluation modality, we introduce the concept of “integrated evaluation” – i.e. integrating horizontal perspectives in evaluations of sectoral policies. A Swedish case study helps identify salient factors affecting the implementation of this type of evaluation. We find that the prospect for integrated evaluation is significantly affected by the perceived inappropriateness in asking independent evaluators to contribute to political agendas, the lack of requisite knowledge to produce credible integrated evaluations, and a disinterest in the integrated perspective among policymakers. In light of our case study, we discuss the outlook for this kind of evaluation and provide ideas on how to support its future implementation.

1. Introduction

There is a widespread belief among policy makers that many of today’s societal problems cannot be solved in the traditional way, where each and every policy problem is designated to a specific policy sector (Jochim and May Citation2010). Instead, complex societal problems, like climate change or gender inequality, are believed to be cross-cutting and thus require the attention of multiple or all policy sectors. Within both the policy and the academic sphere, this strategy to “distribute” a policy problem, its mitigation or solution across sectors is called “policy integration” (Rayner and Howlett Citation2009). Being popularized in the late 1990s, there is a growing literature addressing the integration of so-called horizontal policy perspectives in different policy areas; conditions that enable or hinder it; and/or its desirability and feasibility (Candel and Biesbroek Citation2016; Candel Citation2017; Howlett and Saguin Citation2018; Candel Citation2019; Candel and Biesbroek Citation2016). This article addresses a dimension of the policy cycle that has received little attention in this literature, namely evaluation. Our starting point is that evaluation can play three different roles in the implementation of policy integration strategies. First, evaluation can focus on such strategies in their entirety, like for example the integration of LGBT rights in social policy. Hertin and Berkhout (Citation2003) suggest evaluations of entire policy integration strategies could address four main policy components: agenda setting, horizontal communication, capacity building and policy learning, and their performance throughout governments. This provides the means for policy makers to assess the effectiveness of policy instruments used for integration purposes. Second, evaluation can provide insights on the result of integrated sectoral policies, one example being the study by Kivimaa and Mickwitz (Citation2006), who evaluated the integration of environmental perspectives in Finnish technology policy showing that the implementers indeed grasped the idea of environmental protection but that the perspective was only partially integrated, and implementers missed the crucial step of requiring an assessment of environmental impacts in funding applications. Third, evaluation can integrate horizontal perspectives prior to, or irrespective of, their integration in sectoral policies. We call this evaluation modality integrated evaluation. Such evaluation could pinpoint potentials and unintended synergies or areas where sectoral policies inadvertently contradict the aim to mitigate or solve a cross-cutting problem (Nilsson et al. Citation2012; May, Sapotichne, and Workman Citation2006). Ideally, integrated evaluation could provide insight on when policy integration is feasible and when it is not (Candel Citation2019). The Council of Europe, on the matter of evaluation and its role in the gender mainstreaming of policy, holds that evaluation should be a precept to policymaking, that' evaluations serve as a starting point for the development of new policies' in which the gender perspective is incorporated (The Council of Europe Citation1998, 18).

Whereas in theory, integrated evaluation could be a powerful tool in the process of integrating sectoral policies, implementing it in a sector-based government structure may prove challenging. Jacob, Volkery, and Lenschow (Citation2008) notes that “the sheer complexity of our world, the identification and explanation of all the myriad of possible effects resulting from governmental programs and policies require that evaluators employ a large range of expertise” (175). The author suggests several ways in which applying multiple perspectives in evaluations may be challenging: it requires knowledge in several fields; it may dilute instead of enhance the quality of findings if evaluators search and settle for the lowest common denominator between policy objectives or targets; the outlook of succeeding in applying multiple perspectives can be hampered by “disciplinary chauvinism”; such evaluation can be unintelligible because there is a disjunction between levels of analysis; and finally, it may be too difficult to coordinate.

Despite the promise and the potential pitfalls of integrating horizontal perspectives in sectoral policy evaluation, its practical implementation has not been studied. To start building an understanding thereof we ask the following research question: what are the factors affecting the integration of horizontal perspectives in sectoral policy evaluation? Our study focuses on the implementation of a gender mainstreaming assignment at an evaluation agency tied to the Swedish Ministry of Enterprise and Innovation. In essence, the assignment means that evaluators are charged to consider the national gender equality objectives by integrating a gender perspective in their evaluations and analyses of the Ministry’s policies and strategies. The Swedish government committed to gender mainstreaming (Govt. Bill Citation1993/Citation94:Citation147) in 1994, but thus far the implementation of the strategy has been fraught with problems (Sainsbury and Bergqvist Citation2009). The study is based on interviews with evaluators working at the evaluation agency in question. The interviews were semi-structured and revolved around the practical side of applying a gender perspective in evaluations of enterprise and innovation policies.

Our focus on the integration of a specific and single horizontal perspective in the evaluation of policies in a certain sector and country implies several limitations. First, the integration of a gender perspective in evaluations of enterprise and innovation policies may pose challenges that are similar to, or different from other combinations of perspectives and policy sectors (e.g. the integration of a climate perspective in the evaluation of transportation policies). Previous research has for example pointed out that in Sweden, a general lack of awareness about gender inequality is reinforced by the fact that Swedes believe gender equality is already achieved (Sainsbury and Bergqvist Citation2009). Another factor that may be specific to the integration of a gender perspective is that organizations tend to de-prioritize most things related thereto (Callerstig Citation2014). A second limitation is that we focus on the integration of a single perspective whereas in reality, evaluators may be charged to integrate several perspectives simultaneously (e.g. climate and gender). When this is the case, challenges may be augmented or there may be additional stumbling blocks and issues related to prioritization may arise. Limitations aside, we believe our study makes an important contribution in pointing out several factors that affect the implementation of an integrated approach in sectoral policy evaluation, an area that has received limited attention. Furthermore, our study points out several issues that future research could engage with.

The article is structured as follows: section two reviews some of the literature on policy implementation in general, and on the implementation of policy integration strategies in particular. We present our case study in section three and describe our research method in section four. Section five contains our interview findings, grouped in two primary categories: internal and external factors. Section six includes a discussion that puts our findings in a broader perspective. Given our findings, we also reflect on the potential of harnessing integrated evaluation as a force of change and relatedly, on issues that future research could explore.

2. Lessons from the implementation literature

There is a dearth of studies about the practical side of integrating horizontal perspectives in sectoral policy evaluation. On the other hand, there is a large policy implementation literature and numerous studies about the implementation of policy integration strategies (e.g. Candel Citation2017; Callerstig Citation2014; Rayner and Howlett Citation2009). We believe that this body of literature makes a pertinent starting point since the challenges generally related to implementation and to integrating policy, in particular, may also be relevant for implementing an integrated evaluation approach. For example, a central observation in the policy implementation literature is that the process of translating a policy objective into a product or practice is inherently complex. Matland (Citation1995), Saetren (Citation2005) and Hill and Hupe (Citation2009) provide but a few of the analytical frameworks that hold forth the complex aspects of such processes. Early on, scholars noted that implementation processes tend to be fluid, or non-linear, and represent the sum of different decisions made by various actors along the way rather than one specific factor (e.g. Pressman and Wildavsky Citation1984). Brodkin emphasized the necessity of ability “to convert the ‘state’s policy promises into the state’s policy products'” (Citation1990, 108). The importance of being able to make this “conversion” happen cannot be understated; policy objectives are often ambiguous both when it comes to the nature of the problem and its possible solutions. Thus, implementation often entails learning and innovation on the part of the implementers and in this process, its original objectives can be bent, shrunk, or expanded (Schofield Citation2004; Lombardo, Meier, and Verloo Citation2009).

A clearly specified objective has been held forth as a key success factor by scholars studying the implementation of policy integration approaches (Candel Citation2017). In practice, however, the opposite is often the case, with both policy problems and possible solutions being described using vague language (Jordan and Lenschow Citation2010). Scholars have proposed interpreting the purpose of policy integration as either to prioritize the horizontal objective over sectoral goals or, as to find synergies between the two (Lombardo Citation2005; Squires Citation2005; Lafferty and Hovden Citation2003; Shaw Citation2002; Jahan Citation1995). For sectoral evaluators working within the government, it comes down to which outcomes to focus on: the achievement of horizontal objectives, both horizontal objectives and sectoral goals, or anticipated or serendipitous interlinkages between the two. Which one it is must be defined on all relevant levels.

Another factor that has been put forth as important when adopting an integration approach is that managers are willing to prioritize it (Palmén et al. Citation2020; Candel Citation2017). Typically, willingness among managers “travels” and will thus likely influence whether integration objectives are operationalized (Howlett Citation2009). Committing to integration requires accepting that it may compete with other objectives and thus require re-prioritizing, disrupt existing practices and perhaps affect performance negatively (Six et al. Citation1999; Pollitt Citation2003; Christensen, Fimreite, and Lægreid Citation2007; Candel and Biesbroek Citation2016; Bouckaert, Peters, and Verhoest Citation2010). When it comes to integrating horizontal perspectives in sectoral policy evaluation, it requires that managers are willing to initiate a process where evaluators change focus (fully or partially), adopt new ways of working and deliver essentially different evaluations compared to what the customer is used to.

Willingness is particularly important since integration approaches are rarely imperative, but often rather something policymakers try to persuade organizations to adopt (Palmén et al. Citation2020). Pollack and Hafner-Burton (Citation2010) argue that such soft measures require that the framing of the new approach resonates with the way officials view the world, or if measures have enough “persuasive strength” (Beveridge, Lombardo, and Forest Citation2012, 42). This takes us over to the question of resources and institutional capacities, pointed out by Candel (Citation2017) as being central to successfully implementing an integrated approach. In many ways, the prevailing government structure, where organizations specialized on individual sectors make, deliver and evaluate (Verhoest and Bouckaert Citation2005; Christensen, Lægreid, and Wise Citation2003) directly oppose integration. Indeed, the high degree of specialization that characterize such government structures is the very reason why integration is suggested as an alternative: compartmentalized and fragmented policymaking and delivery has been deemed less favourable for addressing cross-cutting problems (Peters Citation2018; Christensen and Lægreid Citation2007). On top of budgetary and other “hard” resource challenges, a central impediment is a niched knowledge that characterizes the body of staff in a government built around neatly defined policy sectors. Several authors point out that having a highly specialized skillset renders “blindness” to the relevance or application of new perspectives (Palmén et al. Citation2020; Benschop and Verloo Citation2006; Connell Citation2006; Meier Citation2006), whereas successfully integrating a horizontal perspective means that ideas and beliefs about problems and their possible solutions, may have to be re-defined (Bacchi Citation1999; Jochim and May Citation2010). Authors such as Hearn and McKie (Citation2008) point out that this is extra difficult if those ideas are implicit and built upon taken for granted norms.

3. Case description

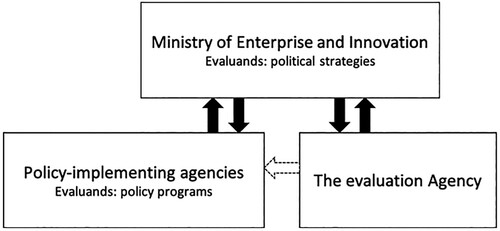

The evaluators interviewed for this case study work for an evaluation agency (henceforth the Agency), responsible for delivering objective evaluations and analyses directly to the Swedish Ministry of Enterprise and Innovation (henceforth the Ministry). Evaluations and analyses focus on both the Ministry’s overarching political strategies and on programmes implemented by agencies that report to the Ministry (). The Ministry is part of a self-proclaimed feminist Swedish government.Footnote1 The government has developed a specific “feminist foreign policy” but there is no corresponding aim associated with its enterprise and innovation policies. Nonetheless, several of the Ministry’s implementing agencies have adopted practices that aim to integrate gender perspectives in the design and delivery of specific programmes (see Anderson et al. Citation2012) ().

Table 1. Results.

The founding of the Agency in 2009 represents a two-dimensional specialization trend; a separation of policy evaluation from implementation and the ramping-up of sector-specific evaluation capacity. This particular “institutionalization” of evaluation is not unique to Sweden but found in many countries whose governments are organized according to the principles of New Public Management (Jacob, Speer, and Furubo Citation2015; Hood Citation1991). What is fairly unique to Sweden is the autonomy and independence of government agencies; the Swedish constitution largely prevents the government from interfering in the daily operations of agencies. Instead, the government exercises its influence through the annual assignment of tasks and the apolitical appointment of agency heads. As part of the balance of power, the parliament oversees agencies through laws, provisions, the National Audit Office, the Parliamentary Ombudsman, the Chancellor of Justice and the administrative court system.

The Agency we study conducts an evaluation of the Ministry’s strategies and programmes, which aim to contribute to the development, reappraisal, and improved efficiency of the government’s policies; where relevant, they should also highlight goal conflicts. The Agency is led by a general director and has three divisions focusing on (in turn) policies for innovation and the greening of the economy; infrastructure and investment; and internationalization and structural change. These divisions employ 32 evaluators and managers (excluding administrative personal), the majority of which are economists by training, while others have heterogeneous backgrounds in e.g. political science, business administration, cultural geography, etc. According to its website, the Agency’s work is governed by three principles: (1) quality, referring to the staff’s substance and methodological knowledge and quality assurance processes; (2) relevance, referring to their ability to provide knowledge in the areas that are most central to the policy sector they serve; and (3) integrity, referring to the heralding of values such as objectivity and impartiality. Furthermore, the Agency states that it does not shy away from identifying conflicts in the existing policy.

In 2015, the Agency was assigned to be part of Sweden’s Gender Mainstreaming of Government Agencies (GMGA) programme. The aim of the programme, originally launched in 2013, is for government agencies to contribute to the achievement of the national gender equality goals by way of integrating gender perspectives throughout their operations (Rönnblom Citation2008). A total of around 60 of Sweden’s 340 government agencies take part in the programme. For the Agency in our case study, the assignment stated that: “[the Agency shall] develop its practices so that it contributes, through evaluations of, for example, business support programmes, to the realization of the gender equality goals”. The only directive in the assignment was that the Agency was expected to present an implementation plan. The assignment was first limited to the period 2016–2018 but was extended indefinitely by the government in 2019.

The Agency went about the GMGA assignment by setting up a working group that reported to the Agency’s management. An initial survey among the Agency’s employees indicated that the level of gender knowledge was varied, but limited. The working group’s required implementation plan suggested several pilot projects, where evaluators would be coached by researchers specialized in the interface between enterprise, innovation and gender. The plan also included seminars with external researchers and the development of a manual for how to think about gender in relation to the evaluation of enterprise and innovation policy. The case study reported here was in addition to the implementation plan and carried out simultaneously. The details of our research process are described in the next section.

4. Methods and data

Our study was conducted as an interactive research project with the ambition to assist the Agency in the implementation of the GMGA assignment. The project was initiated by one of the authors who, at the time, was an Agency employee. The other author had previously been invited to the Agency to present concepts associated with gender mainstreaming. The type of interactive research carried out here, with an “insider” and an “outsider”, can be seen as a middle ground between the distant observation of traditional research and the immersion of action research. The central feature of interactive research is joint learning (Nielssen and Svensson Citation2006) with the dual purpose of contributing to theory development and developing practice (the latter being the responsibility of the practitioners engaged in the project). Following the principles of interactive research, the authors formulated the overarching research question together, i.e. What are the critical factors in integrating a gender equality perspective in the Agency’s analyses and evaluation?

The method included interviews to address the research question, aiming to capture a representative sample of agency staff with regard to gender, position, seniority, and educational background. In total, 17 individuals were interviewed, representing approximately half of the Agency’s evaluators. The interview questions, which were presented to the Agency’s working group for feedback, focused on the practical side of integrating a gender equality perspective in analyses and evaluations. We also asked general questions about educational background, experiences of working with a gender perspective, and evaluation and analysis practice. Other questions focused on the organization and on its relation to the Ministry. We presented each interviewee with an email previewing these themes prior to the interviews. A criticism of the interactive research design is the embeddedness of (one of) the researchers (i.e. the “insider”). To mitigate this effect the “outsider” conducted the interviews with Agency evaluators, rather than the “insider” whose relationship with colleagues may have affected the willingness of the latter to share open and honest views on the gender integration assignment. Two employees declined to participate in an interview (reason unstated) and one asked not to be recorded. Nonetheless, the relationship and discussion between researchers and the Agency management and staff could reasonably be characterized as open and consisting of an atmosphere of mutual trust, suggesting that the results of the study can be considered robust and internally valid (Eikeland Citation2006; Gunnarsson Citation2006).

The interviews varied between 30 minutes and two hours, with all but one being recorded. The interviews were conducted by one of the authors but transcribed and analyzed by both authors independently. A thematic analysis, inspired by Gioia, Corley, and Hamilton (Citation2013), focused on first organizing and coding the transcripts using concepts utilized by the interviewees themselves. This procedure rendered two preliminary coding templates (first-order categories), generated independently by each author. These were compared, discussed, and modified to account for discrepancies before finalizing a set of 10 themes. We grouped these into two distinct meta themes (1) internal factors (e.g. related to the evaluators experiences and skills and the Agency’s management) and (2) external factors (e.g. related to the relationship between the Agency and the Ministry). The final interpretation of the data included two separate consultations with the Agency, in which the initial coding was presented and interpreted, including a discussion of implications for the Agency’s path forward. After some revisions, we presented the final results to the Agency’s management in a report. The present article builds on these data but represents a distinctly different analysis.

5. Findings

5.1. Internal factors

The first set of questions focused on the evaluators themselves and on the Agency’s way to structure work; the interviews spurred a series of introspective statements and reflections on the evaluators' occupational identity, their experience and ability to conduct gender analysis and how they felt about it.

5.1.1. Evaluator’s occupational identity

The interviewees described themselves as producers of knowledge and evidence: “we provide the government with evidence” or “knowledge” that “makes a difference”. In order to be objective, the interviewees believed that it was crucial that knowledge, or evidence, was founded in theory and based on established methods. One of the interviewees talked about the dread of being perceived as “whimsy”.

Besides describing themselves and their colleagues as experts, the majority of the evaluators identified themselves as economists. Indeed, the interviews we conducted were mostly with economists, with only a small group of people belonging to other social science fields, which seemed to be representative of the Agency’s structure. Consequently, there seemed to be a consensus that mainstream neoclassical economic theory was the dominant “house theory”. Some of the economists talked explicitly about how these central assumptions (e.g. that individuals are fully informed, rational, and utility maximizing) provided the basis for how they approach their work. Non-economists typically contrasted their approach, which was described as more “realistic” or “pragmatic” in relation to their economist colleagues. Several were frustrated that their theoretical and methodological approaches were seen as less rigorous despite the fact that, in their view, the complexities of policy interventions into the economic and social world were often better evaluated with other (noneconomic based) theories and methods. One of the non-economists, a self-described social constructivist who worked with qualitative research methods said that: “the world is complex and that’s important for politicians to understand. The correct intervention may not always be the ‘optimal’ one, but rather one that can capture the complexity. We’re much more pragmatic [than the economists] in that sense.” One of the managers also seemed to concur, suggesting that employees of different disciplinary backgrounds had different ideals, different ways of working and different ways of expressing themselves.

5.1.2. Lack of experience

No interviewees had any substantial experience in integrating gender perspectives in analyses or evaluations, according to their own assessment. A handful said that they had, on occasion, discussed gender perspectives as part of their formal education – interestingly, none of these were economists – yet, they did not see themselves as capable of conducting comprehensive gender analyses. While one self-described economist had tried once to integrate the gender perspective in an evaluation, nearly all economists stated that they had not come across gender perspectives during their formal education. One or two were aware of the existence of research at the intersection between economics and gender studies but the majority noted that gender perspectives did not have a big presence in economics. One respondent suggested that: “economics might not be one of the world’s the most open-minded disciplines”.

5.1.3. Inability to “find” gender

One of the main difficulties in implementing the integration assignment was understanding gender in relation to the scope of analyses and evaluations. Several talked about the “ambition level” of integration, saying that it may range from just “showing the picture” to “explaining the picture”. Interviewees instead talked about theoretical gender perspectives and political gender equality goals as if they were one and the same thing; thereby conflating gender as an explanatory variable and gender equality as an outcome. However, deeper discussions in the interviews often revealed that a “feasible scope of analysis” was simply to address gender as an explanatory variable, for example by drawing on and providing gender-disaggregated data.

The interviewees indicated that a key challenge was trying to “find” a gender perspective while also holding to the traditional focus of their analyses and evaluations which, for the most part addressed policies targeting industries, companies, or regions. For gender to be an interesting perspective, the interviewees thought analyses and evaluations had to focus on individuals. As one of them put it: “there has to be people in there”. On the other hand, some interviewees pointed out that “all human activity is gendered” and that with the right knowledge, it should be possible to explore gender dimensions even in policies that were not directly targeting individuals.

Knowledge, or the lack thereof, was thought to be one of the main sticking points. The evaluators regretted the lack of theory to rely on and said that not being in command of what was believed to be the requisite theories made them uncertain about other steps of the evaluation process too. A prominent uncertainty revolved around what data to draw upon and how to access or collect it. Quantitatively oriented interviewees, which represented the majority of our subjects, were primarily concerned with the “measurability” of different phenomena. One person said: “We measure things, that is simply what we do.” Evaluators primarily trained in qualitative methods also expressed concerns about data collection, but their focus was more on their own lack of theoretical knowledge, which prevented them from collecting data relevant for gender analysis. One person said: “You get the answers you ask for.”

5.1.4. Reluctance to venture outside the comfort zone

The perceived lack of knowledge appeared to be arresting to the evaluators themselves, leading to a sort of paralysis that made them reluctant to venture into new territory. The hesitancy manifested itself in remarks such as: “I was a bit scared being thrown into this [gender mainstreaming] without knowing anything about it”, “Many of us lack knowledge and would therefore rather not do it”, and “I would rather stick to what feels safe.” Several respondents reflected on how habits are self-reinforcing since it is more comfortable to stick to the “tried and tested”. One said: “There is a logic to what you do, stemming from the fact that it is what you do.”

Some of the evaluators felt a burden in admitting that they had not integrated gender in their work, irrespective of whether it was a choice or a failure to identify such aspects. This concern was connected to an apprehension of coming through as political or normative. One interviewee said, “The fact that gender equality is seen as something thoroughly positive makes it a sensitive topic.” Another person was weary that “scientific considerations would be influenced by moral indignation”. Several seemed to suggest that charging an evaluation agency to consider political goals is not without complication. The typical stance taken was that the knowledge produced by the agency should only be used as an “indirect input” into the political pursuit of gender equality and that their knowledge-producing outputs (analyses) should be as neutral as possible with respect to political goals. Some expressed uneasiness in pointing out what they saw as obvious conflicts between the Ministry’s goals (i.e. economic growth) and the (political) ones related to gender equality. The discomfort could be traced to the fact that gender equality is seen as “thoroughly positive” and “impossible to be ‘against'”. One respondent was concerned about being “against” it if the analysis came to the “wrong conclusions”.

5.1.5. Need to build institutional capacity

More or less all the interviewed evaluators stated a need for formal efforts to increase the knowledge about gender issues. However, some doubted that training efforts would be useful since they believed that individual evaluators’ expertise were too narrow to render any general gender education fruitful. Instead, they believed that additional resources needed to be tied to the agency, either through recruitment or on a consultancy basis (the latter was included as part of the implementation plan developed by the Agency).

Consultancy by researchers who worked at the intersection between gender and innovation and industrial policy would ideally, as one of the interviewees expressed it, help “see what I cannot see”. Yet, some of the analysts who had worked with such external researchers felt their input to be less relevant in an evaluation context and too centred on gender. This impression reoccurred in the context of recruitment; the Agency’s management had tried but failed to recruit an analyst well versed in both gender studies and enterprise and innovation policy. Some of the analysts expressed a suspicion that gender theorists were “too heavy” on qualitative research methods, and that the agency required someone who was in command of quantitative methods. One interviewee talked about economists that “cheated”; i.e. worked on gender issues with theories from other disciplines. This person could not think of an economist who worked on gender while still adhering to the basic tenets of economic theory. Recruitment of such experts faced the same normative challenges faced by the evaluators themselves. One manager said: “I get nervous at the thought of bringing someone in. Are we comfortable with whatever that person will advocate? We do not want to be perceived as being ideological. There is huge potential for tensions.”

5.1.6. Unclear signals from agency managers

While evaluators admitted to their own shortcoming with respect to knowledge and skills, they stressed the importance of clear guidance from the Agency’s managers in terms of both the goal of the assignment and the resources available for addressing it. Several noted the need for open-minded managers; otherwise, gender integration would never happen. The majority thought that managers should be more explicit in this regard; i.e. when and what evaluations to integrate and how much time to spend on it. One said: “I feel lost, I want more help. I don’t even know what the goal is, what are we trying to achieve here?” Another evaluator contemplated: “When it comes down to it, we are all curious experts who do what we think is fun. Managers need to take [the gender mainstreaming assignment] seriously, but I don’t think they do. The results reflect that.”

Agency managers, on the other hand, looked to the government’s assignment and the appropriation directions for guidance (see also Section 5.1.1): “It is hard to tell from the government’s instruction how much time we should allocate to this.” One manager concluded that “it is up to us to prioritize between this and our core mission”. Without any direction from the management, evaluators were doubtful that they had the backing to push for integration: “as a project leader, I have all the incentives in the world to just spend my resources on the core issue”.

5.2. External factors

The interviews suggested that the preconditions for integrating gender perspectives in evaluations were also related to its principal: the Ministry, and the relation between the Agency and the Ministry.

5.2.1. Vague instructions from the Ministry

The Agency employees struggled to understand the intentions behind the GMGA assignment and suggested a need to map the relationship between two of the government’s policy objectives: the first on gender equality and the second on promoting enterprise and innovation. Several interviewees suggested that the policy connections should be made clear on the level of single programmes, strategies and/or interventions in order to serve as a useful guide for when and how to consider gender perspectives. Without clear direction, employees were unclear which objective should be prioritized. The existence of multiple objectives was seen as problematic from a methodological point of view. The majority of evaluators concluded that the government’s innovation and industrial policy objective should continue to be the Agency’s chief concern, rather than “explaining gender equality”. In practice, many suggested that a path forward could be to focus on gender as a potential explanans of economic growth or factors contributing thereto. The impact on gender inequality could be relevant to explore but only as a potential explanation to changes in the economic growth rate. As one interviewee put it: “If there is an effect of gender inequality on economic growth, it would be a sin not to highlight that.”

5.2.2. The origin of the assignment

Some interviewees suggested that the assignment’s ambiguity could be traced to the fact that it came from the Ministry of Social Affairs, rather than the Agency’s principle (the Ministry). Interviewees described how government assignments are typically developed in one policy sector and then spread to other sectors. As such, the policy development process can be seen as a power struggle between government branches. Hence, several of the interviewees suspected that the integration assignment was forced into the Agency’s mission and not something that the Ministry wanted or had sanctioned. One interviewee said:

The government is an extreme case of a vertically structured organization. All ministries stick to their own principles. There is an inherent skepticism against anything coming from another ministry and a reluctance to deal with disagreements. Such “knots” are just passed on to the agencies. We inherit all conflicts.

Some elaborated on what they thought was a fundamental mismatch between the vertically organized government and the integration assignment. One analyst made the remark that today’s talk of multi-level governance had yet to materialize, at least not in the sense of practical solutions for implementing policy.

5.2.3. Disinterested Ministry staff

None of the interviewees believed that there was any genuine interest in gender equality at the Ministry. Gender issues had never been brought up by Ministry policymakers or bureaucrats in any communication (formal or informal) with the Agency, other than the reporting requirements related to the GMGA assignment. Several said that Ministry bureaucrats had never insisted on gender aspects being incorporated in evaluations. The interviewees interpreted this lack of interest as a clear signal that the Ministry was, at best, unconcerned about integrating gender issues and, at worst, outright opposed to it. One interviewee said that “gender is seen as a complication, and [Ministry bureaucrats] don’t want that”. Another said that “[Ministry bureaucrats] don’t like being critiqued, especially not in that field.” Another person commented that in general, “the civil servants at the Ministry only want to learn about good examples”. Others shared a hunch that the Ministry bureaucrats were not particularly open to out-of-the-box input. One said that: “Generally, their absorptive capacity is poor. It’s a big problem for us.”

5.2.4. It takes two …

The interviewees expressed stark differences when it came to defining the roles and responsibilities for the Agency and Ministry, respectively. Some suggested that the Ministry should establish a set of expectations for the Agency, in particular clarifying the connection between policies aimed at entrepreneurship and innovation and those aimed at gender equality goals. These individuals believed that such actions by the Ministry could provide the legitimization that evaluators felt was necessary in order to explore possibilities for integrating gender perspectives. One person said: “If you look at the Ministry’s strategies and goals you will see that none of them are related to gender equality. We cannot address something that isn’t there.”

Others thought that the Agency should take on a more proactive role vis-à-vis the Ministry, i.e. venture out of the evaluator’s traditional “box” and educate their client about the significance and relevance of gender perspectives in relation to sectoral policies. One interviewee said optimistically: “I think [policymakers and Ministry bureaucrats] would be interested if we do interesting stuff that really adds value.” Another person said: “we have to remind them of this perspective. If we don’t do it, who else will?” Those who suggested that evaluations include these out-of-the-box dimensions stressed the importance of packaging the message. One person said: “we have to be really sophisticated in how we communicate things like that. I’m afraid we load reports too heavy if we incorporate several dimensions. We have to think hard about the presentation”. Another person made the general remark that: “We try to make our products accessible; we make them easy reads and we offer to do oral presentations. We consider timing, we try to sync publications so that they fit with the policy cycle.” Other interviewees, who embraced the freedom associated with a vaguely formulated assignment, stated an ambition to address gender equality both as a potential explanatory variable and as an outcome variable, even if it was an unintended outcome.

6. Discussion

This article explores factors that affect the integration of horizontal perspectives in sectoral government evaluation, a reform that has received little scholarly attention. We presented a case study focusing on the attempt to integrate a gender perspective in evaluations conducted by an agency tied to the Swedish government’s Ministry of Enterprise and Innovation. We identified ten types of decisive challenges which among which we saw two distinct categories: internal and external factors ().

Several of these challenges are similar to those observed in the literature describing the process of integrating policies or implementing policy integration strategies. These include the need for a clear objective and willingness among managers. Others seem to be particularly pertinent to government evaluation. Eleanor Chelimsky, evaluation scholar and former president of the American Evaluation Association, has described such evaluation as “deriv[ing] its role and mandate, the questions it must answer, its need for credibility, and its right to publications of its findings from the structure of the government it serves” (Citation2007, 14). Our study shows that in several senses, assigning sectoral government evaluators to integrate a certain perspective in their practice made them unsure about their role, their mandate, the questions they should answer. Not surprisingly, the result was that evaluators were concerned about the credibility of their evaluations.

The evaluators in our study were asked to integrate a gender perspective so that their evaluations could contribute to reducing gender inequalities. Our interview data make clear that evaluators considered this to be in conflict with their established methods and principles since it contributed to the realization of political goals rather than objective analysis. Evaluators considered gender to be a particularly sensitive topic because, among other things, they believed gender equality to be a political rather than analytical topic. As a result, they were weary that their evaluation results may be viewed through a political lens while at the same time themselves often expressing normative views and having little prior knowledge on gender analysis or gender theories.

Independent of whether the assignment was appropriate, the evaluators felt that they lacked the competencies required to deliver relevant analyses. These results would seem to support previous research, which suggests that sector-specific evaluation has limited capacity to help policymakers and bureaucrats address challenges that extend beyond the sector domain (Drimie and Ruysenaar, Citation2010; Kivimaa and Mickwitz Citation2006). Since the evaluators in our study were experts in enterprise and innovation policy, they lacked the tools to address questions of gender into their evaluations. Since knowledge is the key currency of evaluation, the perceived deficit was vexing.

What then, is to be expected in terms of government evaluators’ competencies given what we know from previous research? Studies into the backgrounds and training of evaluators show that the community is made up of professionals with diverse backgrounds, and that few evaluation practitioners have formal evaluation training (Christie, Quinones, and Fiero Citation2014; Sturges Citation2014; LaVelle and Donaldson Citation2010; Stevahn et al. Citation2005). Jacob, Speer, and Furubo (Citation2015) note for example that a “broad spectrum of social scientists including sociologists, psychologists, political scientists, public administrators, and educational scientists” make up the evaluation community, “with specific mixtures in the various policy sectors” (15). Jacob, Volkery, and Lenschow (Citation2008) notes that “professional evaluation reflects the traditional disciplinary boundaries in academia” (181), and that individual evaluators draw on their “domain-specific knowledge” (175) to an extent that renders “disciplinary isolation” (176). Empirical studies have demonstrated how the disciplinary backgrounds of evaluators inform not only their theoretical knowledge but also their judgement about things like what role to take on vis-à-vis the client and the reliability of different methods (Azzam Citation2010 ; Tourmen Citation2009). For example, Shadish and Epstein (Citation1987) showed that psychologists, economists and political scientists are more likely to be theoretically oriented and draw on quantitative methods than are educators, sociologists, and anthropologists.

Other studies focus on evaluators’ experiential skills (e.g. Tourmen Citation2009). Such knowledge tends to be adapted to specific evaluation contexts (e.g. sectoral domain) and be both theoretically and methodologically pragmatic (Rog, Fitzpatrick, and Conner Citation2012; Donaldson and Lipsey Citation2008; Schwandt Citation2007; Fitzpatrick Citation2004). Still, other studies suggest that over the course of their careers, evaluators develop generic evaluation skills, like for example how to apply ethical evaluation standards (Schwandt Citation2015; King et al. Citation2001). King and Stevhan (Citation2015, 24) discuss the overlap between disciplinary, experiential, and generic skills and suggest they overlap to form the practice profile of individual evaluators. The evaluators we interviewed saw their own profiles, the substance of this overlap, to be less than suited to integrate gender in evaluations in a way that was credible. Our results, together with the research reviewed here, underscore the problem of defining “evaluators” as some “occupational aggregate”, when in fact their skills and training often exist along several “dimensions” (van Maanen and Barley Citation1984). Therefore, the future outlook and relevance of integrated evaluation may be a function of, and perhaps depend on, the policy sector and perspective to be integrated. In short, some horizontal perspectives may be easier to integrate into some policy sectors and more difficult in others.

The evaluators we interviewed were uneasy about their new assignment in large part because they did not fully understand what it entailed. This can be considered an example of “role strain”, which Goode (Citation1960) suggests can be mitigated when there is a belief that important stakeholders may respond positively to accepting (or rejecting) a new role. Policymakers and government bureaucrats committed to integrated evaluation could make all the difference; commitment could make integrated evaluation a legitimate pursuit while a lack thereof will lead to downplaying of its importance, attempts to steer evaluators away from integration, or simply just ignoring evaluation results (van der Knapp Citation2004). In our case, the lack of commitment was decisive.

The literature suggests several explanations for why policymakers or government bureaucrats may be ambivalent about supporting evaluation. Evaluation risks exposing failure, which makes it inherently sensitive (Bovens, ‘t Hart, and Kuipers Citation2006). Further, the fear of exposing such failure is likely determined by how far the integration of sectoral policies has come. Candel and Biesbroek (Citation2016) note that policy integration is rarely linear; instead it is often partial and may contain considerable time lags between different sectors and different governance levels. The fact that evaluation my highlight the existence of only symbolic or “cosmetic” integration ((Mickwitz and Kivimaa Citation2007, 82)), or even worse, only instances of dis-integration (i.e. moving deeper into sectoral realms) will only heighten a ministry’s perception of risk. In these cases, stakeholders’ endorsement of integrated evaluation may well be a function of their level of risk aversion (Howlett Citation2014) and/or their willingness to learn.

It may be instructive to consider an entirely different scenario in which evaluation is integrated before integration of sectoral policy processes and policies has even started. In theory, at least, this scenario could increase the opportunities for key stakeholders like policymakers and government bureaucrats, to learn from the process of integrated evaluation itself. Yet, this type of staging – integration of evaluation first and integration of sectoral policy second – appears to be rare according to Podems (Citation2010), who suggests that evaluation is typically the last stage of the policy process to be integrated. In our particular case, the opportunity for stakeholder learning was not only missed but could have led to a very different outcome for integrating gender equality perspectives in evaluations.

For example, the evaluators we interviewed reported meager support for integrated evaluation by Ministry staff – despite the fact that relevant sectoral policies were already partially integrated. The evaluators were surprised by the staffs’ level of gender-related knowledge, and also the fact that they had never asked evaluators to address gender aspects nor foster debate or dialog about the problems or issues it raises in policy development or implementation. The fact that evaluators criticized their own lack of knowledge, which made it hard for them to “place” gender within their traditional evaluation approaches – seems to have resulted in a gridlock or status quo-like scenario for both the policymakers and the evaluators where it is difficult to distinguish between “cannot do it” and “do not want to do it”. This can be viewed in light of the predominant thinking that these two groups are governed by fundamentally different values and occupational cultures; one develops and implements policy while the other assesses it in a supposedly apolitical sphere (Chelimsky Citation2009). Our study shows, however, that in terms of substance knowledge, the two were in fact quite similar in a way that was decisive for the implementation of gender-integrated evaluation practices: rather than a lack of knowledge hampering their assessment of gender, these groups may have consciously chosen to aspire to “blindness” in the sense of neutrality and objectivity (see e.g. Lundine et al. Citation2019). In fact, previous studies of gender perspectives in mainstream economics suggest that both the “lack of knowledge” and “virtuous aspirations” may be valid explanations (Pearse, Hitchcock, and Keane Citation2019; Woolley, Citation1993). In this Scandinavian-based case study, there may be something more at play: a belief that gender equality has already been achieved, at least relative to many of the world’s other countries (Sainsbury and Bergqvist Citation2009).

Against this background, how can the concept of integrated evaluation be harnessed as a force of change? Candel (Citation2019) note that both capacity and leadership are required for successful policy integration. Our results suggest that although this also holds for integrated evaluation, increased evaluator capacity is not sufficient: even if the evaluation is integrated, the results may not be applied if policymakers and government bureaucrats are not commitment or lack the capacity themselves. Such asymmetries may even render policymakers and bureaucrats averse to integrated evaluation, especially in cases where there is a fear that evaluation will expose the failure to integrate policy adequately (Howlett Citation2014). Some of the evaluators interviewed for this study hinted at such aversion among Ministry staff. Previous work suggests that involving stakeholders in evaluations can increase the knowledge and capacity of both parties (O’Sullivan Citation2004; Cousins Citation2003; Cousins et al. Citation2004). A path forward could thus be to consider the first attempts at integrated evaluation a learning process itself (Schofield Citation2004) in which both the Agency and the Ministry participates. Such evaluations could then constitute a “constructive dialogue” (van der Knapp Citation2004) about the relation between sectoral policies and horizontal perspectives in terms of e.g. assumptions about the characteristics of programme beneficiaries. This type of dialogue – though more time consuming – may result in better outcomes through the conceptual learning and re-framing of policy goals, problems and strategies, which Nilsson (Citation2005) argue are the critical precursors to policy integration processes. Moret-Hartman, Reuzel, Grin, Kramers & van der Wilt (Citation2011, 37) argues that' the quality of an evaluation largely depends on the quality of the underlying problem definition and the quality of the problem definition often improves as stakeholder involvement increases'. In our case, such joint efforts seem especially cumbersome given that both the Agency and the Ministry staff lacked the relevant (gender) knowledge.

Two cardinal problems remain: (1) what policy or programme should be in focus and (2) how to re-define the policy problem to incorporate gender. Jacob, Volkery, and Lenschow (Citation2008) provide a heuristic (originally developed in the context of cross-disciplinary evaluation) that may help in addressing the former. First, the nature of the policy or programme must be such that it allows for some innovation. Second, there must be an evolving scientific understanding of the context of the policy or programme. With regard to re-defining the policy problem itself (so to incorporate gender in our case), Archibald (Citation2020) suggests Carol Bacchi’s “What’s-the-problem-represented-to-be” approach, which we believe may be an apt way forward. This approach represents a way to think critically about the assumptions underlying the definition of policy problems. In an example from Archibald (Citation2020, 14) equal pay for women may be unfairly attributed to lack of training instead of true discrimination, if the problem is defined in terms of a “training problem.”. Both these suggestions require that evaluators themselves are skilled, “open-minded” and “capable of looking past assumptions, ready to engage in a process that goes beyond their traditional comfort zones” (Jacob, Volkery, and Lenschow Citation2008, 187). This goes for Ministry staff too if they are to engage in some first attempts at integrated evaluation. The interviewed evaluators expressed scepticism that there existed individuals with the “right” mix of competencies; those that could undertake thorough and robust gender analysis of enterprise and innovation policies. Whether or not this assumption is correct is an empirical question, which could ultimately improve the outlook of integrated evaluation at the Agency in question. Integrated evaluation is likely to require inter-disciplinary collaboration, whose successful undertaking demands “the capacity to build links between individuals and construct bridges to transfer the conceptual understandings from one to another. These conceptions are often determined by the disciplinary formation of the individuals” (Jacob, Volkery, and Lenschow Citation2008, 187). This case study has focused on one horizontal objective: gender mainstreaming. Evaluators often face the reality of having to integrate several horizontal objectives which raises concerns both about how to understand the relationship between different objectives and, given the reality of limited policy resources, how to make necessary prioritizations between different objectives when drawing conclusions and making recommendations. Different horizontal objectives furthermore reside within different knowledge and political fields making “one size fit all” type of frameworks difficult. These are questions previously addressed in policy integration but that needs to be highlighted and further explored in integrated evaluations.

In conclusion, fundamentally changing the preconditions for integrated evaluation seems to suggest a re-negotiation of the nature of sectoral government evaluation. Future research should explore whether such re-negotiation, is feasible in an institutional landscape where evaluation is characterized by sectoral specialization.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Karolin Sjöö

Karolin Sjöö, PhD, Chalmers University of Technology, Gothenburg, SwedenKarolin Sjöö is a post-doctoral fellow in Science, Technology and Society (STS) studies at the Department of Technology Management and Economics. Her current research focus is the implementation and effects of gender mainstreaming policies within the research policy sphere. Previously, Karolin worked for an independent government agency that conducted evaluations and analyses of research and innovation policies.

Anne-Charlott Callerstig

Anne-Charlott Callerstig, PhD, Senior Researcher, Örebro UniversityAnne-Charlott Callerstig is a Senior Researcher in Gender Studies at the Centre for Feminist Social Studies (CFS) in Örebro University, Sweden. Anne-Charlott has long experience from both research and working practically with gender equality policy issues and gender mainstreaming in Sweden and on a European level. Anne-Charlott has participated in several EU and national research projects focusing the practical implementation of equality objectives and gender mainstreaming in various local and national public authorities and policy areas. Her focus of work includes gender mainstreaming, equality policy and organisation, policy implementation and evaluation, public administration, labour market politics, and interactive research approaches.

Notes

1 www.regeringen.se Accessed 4 June 2020.

References

- Anderson, S., K. Berglund, E. Gunnarsson, and E. Sundin. 2012. Promoting Innovation – Policies, Practices and Procedures, VINNOVA REPORT VR 2012:8. Stockholm: VINNOVA.

- Archibald, T. 2020. “Whats the Problem Represented to be? Problem Definition Critique as a Tool for Evaluative Thinking.” American Journal of Evaluation 41 (1): 6–19.

- Azzam, T. 2010. “Evaluator Responsiveness to Stakeholders.” American Journal of Evaluation 31 (1): 45–65.

- Bacchi, C. L. 1999. Women, Policy and Politics: The Construction of Policy Problems. London: Sage.

- Benschop, Y., and M. Verloo. 2006. “Sisyphus’ Sisters: Can Gender Mainstreaming Escape the Genderedness of Organizations?” Journal of Gender Studies 15 (1): 19–33.

- Beveridge, F., E. Lombardo, and M. Forest. 2012. “‘Going Soft’? Analysing the Contribution of Soft and Hard Measures in EU Gender law and Policy.” In The Europeanization of Gender Equality Policies: A Discursive-Sociological Approach, edited by E. Lombardo and Forest, M. 28–46. London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bouckaert, G., G. B. Peters, and K. Verhoest. 2010. The Coordination of Public Sector Organizations: Shifting Patterns of Public Management. Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bovens, M., P. ‘t Hart, and S. Kuipers. 2006. “The Politics of Policy Evaluation.” In The Oxford Handbook of Public Policy, edited by M. Moran, M. Rein, and R. E. Goodin, 319–335. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Brodkin, E. Z. 1990. “Implementation as Policy Politics.” In 1990. Implementation and the Policy Process: Opening up the Black Box, edited by D. J. Palumbo and D. J. Calista, 107–118. New York: Greenwood Press.

- Callerstig, A.-C. 2014. “Making Equality Work: Ambiguities, Conflicts and Change Agents in the Implementation of Equality Policies in Public Sector Organisations.” PhD diss., Linköping University Press, Linköping.

- Candel, J. J. L. 2017. “Holy Grail or Inflated Expectations? The Success and Failure of Integrated Policy Strategies.” Policy Studies 38 (6): 519–552.

- Candel, J. J. L. 2019. “The Expediency of Policy Integration.” Policy Studies 42 (4): 346–361. doi:10.1080/01442872.2019.1634191.

- Candel, J. J. L., and R. Biesbroek. 2016. “Toward a Processual Understanding of Policy Integration.” Policy Sciences 49 (3): 211–231.

- Chelimsky, E. 2007. “Factors Influencing the Choice of Methods in Federal Evaluation Practice.” New Directions for Evaluation 2007: 13–33.

- Chelimsky, E. 2009. “Integrating Evaluation Units Into the Political Environment of Government: The Role of Evaluation Policy.” New Directions for Evaluation 2009: 51–66.

- Christensen, T., L. A. Fimreite, and P. Lægreid. 2007. “Reform of the Employment and Welfare Administrations the Challenges of co-Coordinating Diverse Public Organizations.” International Review of Administrative Sciences 73 (3): 389–408.

- Christensen, T., and P. Lægreid. 2007. “The Whole-of-Government Approach to Public Sector Reform.” Public Administration Review 67 (6): 1059–1066.

- Christensen, T., P. Lægreid, and L. R. Wise. 2003. “Evaluating Public Management Reforms in Central Government: Norway, Sweden and the United States of America.” In Evaluation in Public Sector Reform: Concepts and Practice in International Perspective, edited by H. Wollman, 56–79. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Christie, C. A., P. Quinones, and L. Fiero. 2014. “Informing the Discussion on Evaluator Training: A Look at Evaluators’ Course Taking and Professional Practice.” American Journal of Evaluation 35 (2): 274–290.

- Connell, R. 2006. “The Experience of Gender Change in Public Sector Organizations.” Gender, Work and Organization 13 (5): 435–452.

- Cousins, J. B. 2003. “Utilization Effects of Participatory Evaluation.” In International Handbook of Educational Evaluation, edited by T. Kelleghan and D. L. Stufflebeam, 245–265. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic.

- Cousins, J. B., S. C. Goh, S. Clark, and L. E. Lee. 2004. “Integrating Evaluative Inquiry Into the Organizational Culture: A Review and Synthesis of the Knowledge Base.” Canadian Journal of Program Evaluation 19 (2): 99–141.

- Council of Europe. 1998. “Gender Mainstreaming: Conceptual Framework, Methodology and Presentation of Good Practices.” Council of Europe. EG-S-MS (98) 2 rev.

- Drimie, S., and S. Ruysenaar. 2010. “The Integrated Food Security Strategy of South Africa: An Institutional Analysis.” Agrekon: Agricultural Economics Research, Policy and Practice in Southern Africa 49 (3): 316–337.

- Donaldson, S. I., and M. W. Lipsey. 2008. “Roles for Theory in Contemporary Evaluation Practice: Developing Practical Knowledge.” In The Handbook of Evaluation: Policies, Programs, and Practices, edited by I. Shaw, J. Greene, and M. Mark, 56–75. London: Sage.

- Eikeland, O. 2006. “Condescending Ethics and Action Research.” Action Research 4 (1): 37–47.

- Fitzpatrick, J. L. 2004. “Exemplars as Case Studies: Reflections on the Link Between Theory, Practice and Context.” American Journal of Evaluation 25 (4): 541–559.

- Gioia, D. A., K. G. Corley, and A. L. Hamilton. 2013. “Seeking Qualitative Rigor in Inductive Research: Notes on the Gioia Methodology.” Organizational Research Methods 16 (1): 15–31.

- Goode, W. J. 1960. “A Theory of Role Strain.” American Sociological Review 25 (4): 483–496.

- Govt. Bill 1993/94. 147 Gender Equality Policy: Shared Power—Shared Responsibility. (Prop. 1993/94:147). Jämställdhetspolitiken: delad makt – delat ansvar.

- Gunnarsson, E. 2006. “The Snake and the Apple in the Common Paradise.” In Action Research and Interactive Research. Beyond Practice and Theory, edited by K. Aagard Nielsen and L. Svensson, 117–143. Maastricht: Shaker Publishing.

- Hearn, J., and L. McKie. 2008. “Gendered Policy and Policy on Gender: The Case of ‘Domestic Violence.’” Policy & Politics 36 (1): 75–91.

- Hertin, J., and F. Berkhout. 2003. “Analysing Institutional Strategies for Environmental Policy Integration: The Case of EU Enterprise Policy.” Journal of Environmental Policy and Planning 5 (1): 39–56.

- Hill, M., and P. Hupe. 2009. Implementing Public Policy. London: SAGE publications.

- Hood, C. 1991. “A Public Management for all Seasons?” Public Administration 69 (1): 3–19.

- Howlett, M. 2009. “Policy Analytical Capacity and Evidence-Based Policy-Making: Lessons from Canada.” Canadian Public Administration 52 (2): 153–175.

- Howlett, M. 2014. “Why Are Policy Innovations Rare and so Often Negative? Blame Avoidance and Problem Denial in Climate Change Policy-Making.” Global Environmental Change 29: 395–403.

- Howlett, M., and K. Saguin. 2018. “Policy Capacity for Policy Integration: Implications for the Sustainable Development Goals.” Working paper, Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy Research Paper No. 18-06.

- Jacob, S., S. Speer, and J.-E. Furubo. 2015. “The Institutionalization of Evaluation Matters: Updating the International Atlas of Evaluation 10 Years Later.” Evaluation 21 (1): 6–31.

- Jacob, K., A. Volkery, and A. Lenschow. 2008. “Instruments for Environmental Policy Integration in 30OECD Countries.” In Innovation in Environmental Policy? Integrating the Environment for Sustainability, edited by A. Jordan and A. Lenschow, 24–48. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

- Jahan, R. 1995. The Elusive Agenda: Mainstreaming Women in Development. London: Zed Books.

- Jochim, A. E., and P. J. May. 2010. “Beyond Subsystems: Policy Regimes and Governance.” Policy Studies Journal 38 (2): 303–327.

- Jordan, A., and A. Lenschow. 2010. “Policy Paper Environmental Policy Integration: A State of the art Review.” Environmental Policy and Governance 20 (3): 147–158.

- King, J. A., and L. Stevahn. 2015. “Competencies for Program Evaluators in Light of Adaptive Action: What? So What?” Now What? New Directions for Evaluation 2015: 21–37.

- King, J. A., L. Stevahn, G. Ghere, and J. Minnema. 2001. “Toward a Taxonomy of Essential Evaluator Competencies.” American Journal of Evaluation 22 (2): 229–247.

- Kivimaa, P., and P. Mickwitz. 2006. “The Challenge of Greening Technologies – Environmental Policy Integration in Finnish Technology Policies.” Research Policy 35 (5): 729–744.

- Lafferty, W., and E. Hovden. 2003. “Environmental Policy Integration: Towards an Analytical Framework.” Environmental Politics 12 (3): 1–22.

- LaVelle, J. M., and S. I. Donaldson. 2010. “University-based Evaluation Training Programs in the United States 1980-2008: An Empirical Examination.” American Journal of Evaluation 31 (1): 9–23.

- Lombardo, E. 2005. “Integrating or Setting the Agenda? Gender Mainstreaming in the European Constitution-Making Process.” Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State & Society 12 (3): 412–432.

- Lombardo, E., P. Meier, and M. Verloo. 2009. The Discursive Politics of Gender Equality. Stretching, Bending and Policymaking. London: Routledge.

- Lundine, J., I. L. Bourgeault, K. Glonti, E. Hutchinson, and D. Balabanova. 2019. ““I Don't see Gender”: Conceptualizing a Gendered System of Academic Publishing.” Social Science & Medicine 235: 1–9.

- Matland, R. E. 1995. “Synthesizing the Implementation Literature: The Ambiguity-Conflict Model of Policy Implementation.” Journal of Public Administration and Theory 5 (2): 145–174.

- May, P. J., J. Sapotichne, and S. Workman. 2006. “Policy Coherence and Policy Domains.” Policy Studies Journal 34 (3): 381–403.

- Meier, P. 2006. “Implementing Gender Equality: Gender Mainstreaming or the Gap Between Theory and Practice.” In Women's Citizenship Rights and Political Rights, edited by S. K. Hellsten, H. A. Maria, and K. Daskalova, 179–198. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Mickwitz, P., and P. Kivimaa. 2007. “Evaluating Policy Integration: The Case of Policies for Environmentally Friendlier Technological Innovations.” Evaluation 13 (1): 68–86.

- Moret-Hartman, M., R. Reuzel, J. Grin, C. Kramers, and G. J. Van der Wilt. 2011. “Strengthening Evaluation Through Interactive Problem Structuring: A Case Study of Hospital Care After Attempted Suicide.” Evaluation 17: 37–52.

- Nilsson, M. 2005. “Learning, Frames, and Environmental Policy Integration: The Case of Swedish Energy Policy.” Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy 23 (2): 207–226.

- Nielsen, K. A., and L. Svensson. (Eds). 2006. Action Research and Interactive Research. Beyond Practice and Theory. Maastricht: Shaker Publishing.

- Nilsson, M., T. Zamparutti, J. E. Petersen, B. Nykvist, P. Rudberg, and J. McGuinn. 2012. “Understanding Policy Coherence: Analytical Framework and Examples of Sector Environment Policy Interactions in the EU.” Environmental Policy and Governance 22 (6): 395–423.

- O’Sullivan, R. G. 2004. Practicing Evaluation: A Collaborative Approach. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Palmén, R., L. Arroyo, J. Müller, S. Reidl, M. Caprile, and M. Unger. 2020. “Integrating the Gender Dimension in Teaching, Research Content & Knowledge and Technology Transfer: Validating the EFFORTI Evaluation Framework Through Three Case Studies in Europe.” Evaluation and Program Planning 79 (April 2020): 1-10. 101751.

- Pearse, R., J. N. Hitchcock, and H. Keane. 2019. “Gender Inter/Disciplinarity and Marginality in the Social Science and Humanities: A Comparison of six Disciplines.” Women’s Studies International Forum 72 (Jan–Feb): 109–126.

- Peters, G. B. 2018. “The Challenge of Policy Coordination.” Policy Design and Practice 1 (1): 1–11.

- Podems, D. R. 2010. “Feminist Evaluation and Gender Approaches: There’s a Difference?” Journal of MultiDisciplinary Evaluation 6 (14): 1–17.

- Pollack, M. A., and E. M. Hafner-Burton. 2010. “Mainstreaming International Governance:The Environment, Gender, and IO Performance in the European Union.” The Review of International Organizations 5: 285–313.

- Pollitt, C. 2003. “Joined-up Government: A Survey.” Political Studies Review 1 (1): 34–49.

- Pressman, J. L., and A. Wildavsky. 1984. Implementation. How Great Expectations in Washington Are Dashed in Oakland; Or, Why It's Amazing That Federal Programs Work at All. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Rayner, J., and M. Howlett. 2009. “Introduction: Understanding Integrated Policy Strategies and Their Evolution.” Policy and Society 28 (2): 99–109.

- Rog, D. J., J. L. Fitzpatrick, and R. F. Conner. 2012. Context: A Framework for its Influence on Evaluation Practice. New Directions for Evaluation: No. 135. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Rönnblom, M. 2008. “De-politicising Gender? Constructions of Gender Equality in Swedish Regional Policy.” In Critical Studies of Gender Equalities: Nordic Dislocations, Dilemmas and Contradictions, edited by E. Magnusson, M. Rönnblom, and H. Silius, 112–134. Göteborg: Makadam Publishers.

- Saetren, H. 2005. “Facts and Myths About Research on Public Policy Implementation: out- of-Fashion, Allegedly Dead, but Still Very Much Alive and Relevant.” Policy Studies Journal 33 (4): 559–582.

- Sainsbury, D., and C. Bergqvist. 2009. “The Promise and Pitfalls of Gender Mainstreaming.” International Feminist Journal of Politics 11 (2): 216–234.

- Schofield, J. 2004. “A Model of Learned Implementation.” Public Administration 82 (2): 283–308.

- Schwandt, T. 2007. “The Role of Practical Knowledge in Learning.” Paper delivered at the 21st annual conference of the American Evaluation Association, ‘learning to evaluate, evaluating to learn.’ Baltimore, 11/08/2007.

- Schwandt, T. 2015. Evaluation Foiundations Revisited: Cultivating a Life of the Mind for Practice. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Shadish, W. R., and R. Epstein. 1987. “Patterns of Program Evaluation Practice among Members of the Evaluation Research Society and Evaluation Network.” Evaluation Review 11 (1): 555–590.

- Shaw, J. 2002. “The European Union and Gender Mainstreaming: Constitutionally Embedded or Comprehensively Marginalised?” Feminist Legal Studies 10 (3): 213–226.

- Six, Perri, D. Leat, K. Seltzer, and G. Stoker. 1999. Governing in the Round. Strategies for Holistic Government. London: Demos.

- Squires, J. 2005. “Is Mainstreaming Transformative? Theorizing Mainstreaming in the Context of Diversity and Deliberation.” Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State & Society 12 (3): 366–388.

- Stevahn, L., J. A. King, G. Ghere, and J. Minnema. 2005. “Evaluator Competencies in University-Based Evaluation Training Programs.” Canadian Journal of Program Evaluation 20 (2): 101–123.

- Sturges, K. M. 2014. “External Evaluation as Contract Work.” American Journal of Evaluation 35 (3): 346–363.

- Tourmen, C. 2009. “Evaluators’ Decision Making: The Relationship Between Theory, Practice, and Experience.” American Journal of Evaluation 30 (1): 7–30.

- van der Knapp, P. 2004. “Theory-based Evaluation and Learning: Possibilities and Challenges.” Evaluation 10 (1): 16–34.

- van Maanen, J., and S. Barley. 1984. “Occupational Communities: Culture and Control in Organizations.” In Research in Organizational Behaviour, edited by B. Straw and L. Cummings, 287–365. Greeneich, CT: JAI Press.

- Verhoest, K., and G. Bouckaert. 2005. “Machinery of Government and Policy Capacity: The Effects of Specialization and Coordination.” In Challenges to State Policy Capacity: Global Trends and Comparative Perspectives, edited by M. Painter and J. Pierre, 92–111. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave MacMillan.

- Woolley, F. R. 1993. “The Feminist Challenge to Neoclassical Economics.” Cambridge Journal of Economics 17 (4): 485–500.