ABSTRACT

An empirical puzzle exists regarding the failure of state parties to comply with international agreements. Offering new empirical insights, this article aims to enhance understanding of non (or weak) compliance with international human rights agreements by state parties. Documentary analysis supplemented with semi-structured interviews is used to explore UK compliance with the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. Through the empirical case study, the results provide valuable insights into the domestic compliance system and compliance barriers within the under researched human rights sector. The results show that multiple barriers impact compliance within the UK and its four nations, to varying degrees. Differences also exist regarding the extent to which specific barriers emerge within the state and domestic compliance systems. Lastly, the findings provide evidence to support a cyclical model of the domestic compliance system, thereby advancing the current, linear understanding.

1. Introduction

Traditional international relations theory suggests that upon ratification of an international treaty or convention, the state party intends to comply (Simmons Citation2009). Contrarily, “false positives” exist; research has evidenced that despite ratification, some state parties wilfully violate, and fail to comply with, international agreements (Hollyer and Rosendorff Citation2011; Simmons Citation2009; Hathaway Citation2007). Given that compliance is critical to the effectiveness of international agreements (Jacobson and Weiss Citation1995) and policy success (Howlett Citation2018; Weaver Citation2014; Shafir Citation2013), the persistent and challenging problem of non-compliance prompts an important question within the policy sciences. Why, despite ratification of international conventions, do state parties fail to comply with international agreements?

Efforts to explain state compliance with international agreements and policy have previously focused upon policy implementation (Lele Citation2018), policy adoption and institutional reform (Avdeyeva Citation2010) and domestic-systemic interactions (Coban Citation2020; Quaglia Citation2019). Recently, in recognition of their interlinking nature, increasing focus has been placed upon compliance and the surrounding policy design issues (Houlihan Citation2014; Weaver Citation2014; Shafir Citation2013). Despite being a significant aspect of policy design that offers insight into state compliance, few studies have analysed the compliance system. The dearth of research to utilize this theoretical framework has focused upon international compliance systems (Houlihan Citation2014; Mitchell Citation2001) and the ways in which domestic compliance and enforcement regimes secure target compliance (Weaver Citation2014). Nevertheless, the construction of compliance regimes requires more systematic analysis than currently exists (Howlett Citation2018). In particular, the domestic compliance system has attracted insufficient attention. Whereas Weaver (Citation2014) analysed target compliance, this research focused upon the domestic compliance system and state compliance.

Given that compliance with human rights treaties often occurs within the domestic environment (Simmons Citation2009), the human rights sector is perceived as an appropriate context for advancing understanding of the domestic compliance system. To demonstrate the practical significance of the empirical focus, human rights lie at the heart of the sustainable development goals (United Nations Citation2020). Although international human rights conventions possess the potential to improve and transform the quality of people’s lives globally, state compliance with human rights agreements has received limited empirical attention (Simmons Citation2009). Through the analysis, this article also contributes toward the need for greater academic understanding of the barriers to state compliance within the human rights sector (LeBlanc, Huibregtse, and Meister Citation2010; Simmons Citation2009).

Adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in 1989, the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) is uniquely positioned as the most widely ratified human rights treaty in the world; the USA remains the only country yet to ratify (United Nations Citation2021). Despite the scale of ratification, ongoing, worldwide child rights violations occur (United Nations Citation2017). The chosen case study was the UK. Despite being comprised of industrialized nations, the UK achieved a low position (169/182) in the 2021 KidsRights Index (KidsRights Citation2021). This ranking is intriguing as KidsRights (Citation2016) found a very strong (0.81) correlation between the KidsRights index and the Human Development index, evidencing that non-compliance was more likely amongst under-developed countries. Furthermore, recent assessments conducted by the Committee on the Rights of the Child (the Committee) and non-governmental organizations (NGOs), criticized the UK’s UNCRC compliance (CRAE Citation2018; Concluding Observations Citation2016). As a developed country that is failing to comply with international standards, the UK case study is empirically novel. The apparent lack of commitment makes the UK an interesting case for investigating UNCRC compliance. Additionally, the case study contributes towards the existing gap in the scrutiny of the UK’s UNCRC compliance (Scotland Civil Society Report Citation2020).

This research aimed to enhance understanding of non (or weak) compliance with international human rights agreements by state parties. Through empirical analysis of the chosen case study (UK UNCRC compliance), barriers to state compliance were explored. Within the state and domestic compliance systems, the emergence of specific compliance barriers varied. Barriers were found to impact UNCRC compliance within the UK and its four nations, to varying degrees. Lastly, the findings provide evidence to support a cyclical model of the domestic compliance system, thereby advancing the current, linear understanding.

2. Literature review

2.1. The compliance process

Compliance transcends implementation and refers to whether a country adheres to an accord’s provisions and the instituted implementing measures (Jacobson and Weiss Citation1995). Although this conceptualization defined compliance with international environmental agreements, scholars have successfully applied the definition to compliance regimes within different sectors, including the human rights sector (LeBlanc, Huibregtse, and Meister Citation2010).

Recently, the literature has established a dynamic link between international standard setting and the domestic compliance process (Coban Citation2020; Quaglia Citation2019; Farrell and Newman Citation2016). Coban (Citation2020) summarized three stages of the compliance process. First, policy formulation at the international level occurs. Second, during an interpretation phase, domestic actors make sense of the international standards. Third, state compliance is determined by interactions in the domestic policy process. Within the human rights sector, state compliance primarily occurs within the domestic environment (Simmons Citation2009). Therefore, to examine the UK’s UNCRC compliance, this study focused upon Coban’s (Citation2020) third stage of the compliance process; the domestic policy process.

In recognition of their interlinking nature, there has recently been renewed interest in compliance and policy design (Houlihan Citation2014; Weaver Citation2014; Shafir Citation2013). Studies to integrate compliance and policy theory have investigated the dynamics of policy implementation (Lele Citation2018), policy adoption and institutional reform (Avdeyeva Citation2010), and matched policy tools to behavioural compliance characteristics (Howlett Citation2018; Houlihan Citation2014). Despite being a significant aspect of policy design that offers insight into state compliance, the domestic compliance system has only received a small amount of attention and holistic application of the framework is rare (Weaver Citation2014; Mitchell Citation2001). As a significant aspect of policy design, the compliance regime requires more systematic analysis (Howlett Citation2018).

2.2. The compliance system

Mitchell (Citation1996, 17) defined a compliance system as the “subset of the treaty’s rules and procedures that influence the compliance level of a given rule”. Three subsystems were identified: the primary rule system, compliance information system and non-compliance response system. The primary rule system (which shares key features of Weaver’s (Citation2014) compliance regime), refers to the rules, procedures and actors. Its purpose is to identify the actors subject to, and methods of, regulation. Obligational clarity is integral to the primary rule system (Mitchell Citation1996). Focusing upon the child rights regime, Kilkelly (Citation2019) evaluated domestic legislation and attributed variations to the relationship between international and national law; in monist states the UNCRC is automatically incorporated into national law, whereas in dualist states a selection of provisions are commonly transposed into the national legal system. Although useful from an implementation perspective, evaluating domestic legislation alone, does not provide sufficient insight into state compliance (Bafoil Citation2013; Jacobson and Weiss Citation1995).

Weaver (Citation2014) referred to the “enforcement regime” (the monitoring and enforcement of rules). Monitoring and enforcement are interlinked in practice; identification of non-compliance is an important prerequisite for enforcing international agreements (Hollyer and Rosendorff Citation2011). However, identification of non-compliance does not necessarily lead to enforcement (Weaver Citation2014). The enforcement regime shares similarities with Mitchell’s (Citation1996) compliance information and non-compliance response systems. The compliance information system aims to provide clarity regarding performance and compliance. This is achieved through the collection of relevant data that is rigorously analysed and widely circulated. Within the human rights sector, the UNCRC (Citation1989) was the first to invite specialized child rights agencies and NGOs to contribute to the compliance information system. Indicating the continued importance of non-governmental actors in the compliance monitoring process, written reports submitted to the Committee by civil society organizations, national human rights institutions and children’s commissioners, mark the beginning of the examination process. Informed by this data, the Committee develops a public list of limited issues for examination which the state party responds to (The Committee Citation2021). Within the human rights sector, a paucity of research has evaluated international compliance monitoring mechanisms (Krommendijk Citation2015; Kelly Citation2009; Collins Citation2008). Although LeBlanc, Huibregtse, and Meister (Citation2010) considered state compliance with the reporting requirements of human rights conventions, insights into the domestic compliance information system are missing.

The non-compliance response system comprises the actors, processes and rules that govern the formal and informal responses used to encourage non-compliant actors to comply (Mitchell Citation1996). This subsystem is most closely linked to theoretical debates surrounding the facilitation and enforcement of compliance. The compliance-deterrence orientation dominates the compliance discipline (Howlett Citation2018). Although deterrence mechanisms only affect compliance marginally, non-compliance is considerably affected by their absence (Yan, Heijden, and Rooij Citation2017). Within the human rights sector, the frequent absence of traditional enforcement mechanisms (e.g. sanctions, right of action in an international tribunal), combined with low non-compliance costs, means that agreement ratification may be perceived as a relatively costless expression of support; high ratification levels may exist alongside low compliance levels (Hathaway Citation2007). Contrary to the compliance-deterrence orientation, investigating the United Nations Convention Against Torture, Hollyer and Rosendorff (Citation2011) found that higher compliance costs can lead to a pool of signatories that is increasingly dominated by parties with no compliance intentions. Additionally, Simmons (Citation2009) argued that rationalist theories of compliance, which imply external enforcement mechanisms, are an awkward fit for analysing compliance with human rights due to the frequent absence of traditional enforcement mechanisms, low non-compliance costs and lack of reciprocal compliance. Although limited research has focused upon the non-compliance response system within the human rights sector, Avdeyeva (Citation2010) found that civil society plays an important role in mobilizing public opinion and influencing the political agenda through indirect and direct pressure on governments. In the absence of formal enforcement mechanisms, civil society campaigning has emerged as an informal response that can contribute toward state compliance (Becker Citation2012).

2.3. A cyclical model of the compliance system

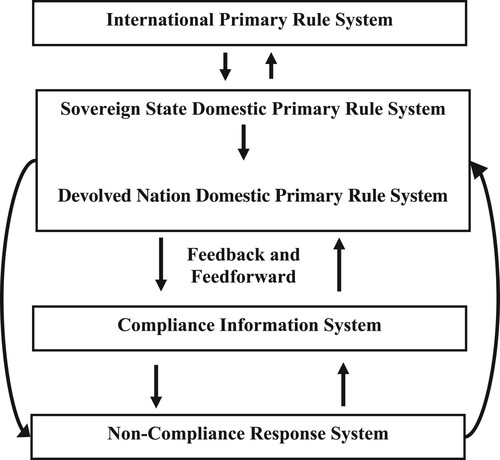

Regarding policy design and implementation, Ansell, Sørensen, and Torfing (Citation2017) proposed a new policy making model where collaborative feedback and feedforward connects policy design and implementation. Feedback within the policy process was also evidenced in the “new interdependence” literature (Farrell and Newman Citation2016); domestic policy changes are subject to policy feedbacks (Newman and Posner Citation2016) that are derived from international regulatory changes (Quaglia Citation2019). Within the domestic policy process, focusing upon Turkey’s compliance with Basel III, Coban (Citation2020) found evidence of a regulatory policy process that takes place through a feedback system. In contrast, the compliance system conveys a linear policy design process (Mitchell Citation1996). Informed by the literature, the author theorizes that the empirical analysis will evidence a cyclical model of the domestic compliance system, where the subsystems are interlinked and connected through feedback and feedforward ().

2.4. Barriers to compliance

The compliance system is a significant aspect of policy design that offers insight into state compliance (Mitchell Citation1996). However, to design effective policy (including an effective domestic compliance system), better understanding of compliance barriers is required. Weaver (Citation2014) demonstrates the interlinking nature of the theoretical frameworks; the degree of compliance is influenced by both the compliance regime and compliance barriers. Similarly, Coban (Citation2020) argued that the compliance process is equally as important as factors that facilitate (or hinder) compliance.

Whilst compliance motivations have received a large amount of academic attention (Carter and Siddiki Citation2019; Thornton, Gunningham, and Kagan Citation2005; Winter and May Citation2001), comparatively fewer studies have analysed compliance barriers. Weaver’s (Citation2014) study is a notable exception. Analysing the Swedish individual account pension system and welfare reform in the United States, Weaver conducted a preliminary test of a framework to examine barriers to target compliance with government policy. The first category, perceived incentives, included problems relating to incentives / sanctions, monitoring and enforcement. The second category, willingness to comply, included peer effects, information / cognition problems and attitude / belief problems. The third category, capacity, included resource and autonomy problems. Linked to the third category, in their analysis of policy capacity, Wu, Ramesh, and Howlett (Citation2015) provided a framework comprising three levels of resources and capabilities (individual, organizational and systemic) and three sets of skills and competencies (analytical, political and operational). Whereas Weaver (Citation2014) analysed target compliance, this research adopted a different analytical perspective by exploring the barriers to state compliance.

Whilst Weaver’s (Citation2014) research provides a comprehensive framework for analysing compliance barriers, further investigation is required (Howlett Citation2018; Weaver Citation2014). Additionally, compliance barriers can vary substantially across different sectors (Weaver Citation2014). To date, there is limited empirical investigation into compliance barriers with human rights agreements at the systemic, state and individual level (Simmons Citation2009). Therefore, the extent to which similar compliance barriers exist within the human rights sector is relatively unknown. The dearth of research to investigate this issue identified authoritarian regime design as a factor that influenced non-compliance with human rights agreements by state parties (Hollyer and Rosendorff Citation2011; Simmons Citation2009; Hathaway Citation2007). However, looking at single or few barriers is likely to yield poor understanding; non-compliance is caused by a range of interlinking barriers (Weaver Citation2014).

Contributing to the current literature, this paper offers valuable insights into an under researched area, specifically non (or weak) compliance with international human rights agreements by state parties. (Non) compliant behaviour is influenced by the compliance regime and compliance barriers (Weaver Citation2014). This research utilized both interrelated theories. In recognition that state compliance is determined by interactions in the domestic policy process (Coban Citation2020), Mitchell’s (Citation1996) compliance system was used as an analytical framework to provide insights into the domestic compliance policy process. Throughout the analysis, non (or weak) compliance within the three components of the compliance system was identified. Additionally, Weaver’s (Citation2014) barriers to compliance framework was used to explain non (or weak) compliance. Whereas Weaver (Citation2014) used the compliance regime and compliance barriers to explain patterns of individual and aggregate compliance, this research focused upon explaining state compliance.

3. Methods

A qualitative case study approach was used to investigate the UK’s UNCRC compliance. Though the UNCRC is uniquely positioned as the most widely ratified human rights treaty in the world, existing accounts do not shed sufficient light on the empirical puzzle of state compliance with the UNCRC. The UK and its four respective nations were chosen for analysis. Comprising five domains, the KidsRights Index is the only global, annual index that measures the extent to which countries are committed to improving the rights of children. Although KidsRights (Citation2016) found a very strong (0.81) correlation between the KidsRights index and the Human Development index, the UK represents an anomaly. Despite ranking 13th in the Human Development Report (Citation2020), the UK achieved a low position (169/182) in the KidRights Index (Citation2021). This apparent lack of commitment makes the UK an interesting case for investigating state compliance with the UNCRC.

Prior to conducting the research, ethical approval was obtained. A qualitative case study approach comprising documents, speeches and semi-structured interviews was used. The first stage involved a thematic analysis of government and non-governmental policy reports, documents and speeches that were specific to UNCRC compliance within the UK and its four nations. To enhance the quality of selected documents, Scott’s (Citation1990) quality control criteria (credibility, authenticity, representativeness and meaning) was utilized. To ensure authenticity, documents were sourced through the official websites of relevant organizations and departments (e.g. UNICEF UK, the Office of the Children’s Commissioner). Credibility was increased through the selection of documents that were produced independently from the research. Representativeness was ensured through the selection of data relevant to compliance that was published from 2016 onwards (to capture the UK’s current combined sixth and seventh periodic review). Regarding meaning, in addition to conducting a thematic analysis on the text, the researcher considered the political and social context within which the document was written.

State document examples include the Welsh Parliament’s Children’s Rights in Wales Report (Citation2020) and the House of Lords’ Children’s Rights Briefing (Citation2019). Written and oral evidence submitted for state reports was also analysed. Examples of non-governmental documents include reports and written evidence submitted by civil society to the Committee to inform its current List of Issues Prior to Reporting. Example documents submitted by non-departmental public bodies include the Equality and Human Rights Commission’s report and the UK and Northern Ireland Children’s Commissioner report. Children’s voices were captured through the analysis of reports such as the Children and Young Person’s version of the Commissioners’ Report. Each document was carefully read by the researcher and the analysis focused upon statements that linked to compliance, compliance barriers and the compliance system. In recognition that document analysis requires reflexivity, significant amounts of cross-referencing was used to create powerful documentary realities (Coffey Citation2014). The documentary analysis also informed the development of non-leading, semi-structured interview questions.

Documentary analysis was supplemented by semi-structured interviews. Semi-structured interviews provided rich data regarding the participant’s experience and viewpoint regarding the UK’s UNCRC compliance. Purposive sampling was used to target organizations, departments and individuals who contribute towards compliance monitoring in the UK, and enhance representation of the four nations, the public and third sector. Snowball sampling was also used to reach additional interviewees. Recruitment of interviewees continued until data saturation, defined as the point at which no new themes emerged, was reached (Fugard and Potts Citation2015). Ten interviews were conducted with representatives from Children England, Children in Northern Ireland (CiNI), Children in Scotland, Children’s Rights Alliance for England (CRAE), Together, UNICEF UK and the Wales Observatory on Human Rights of Children and Young People (Wales Observatory). Perspectives were also gained from the Welsh Youth Parliament Manager (WYPM) at Welsh Parliament, an independent child right’s consultant and CRAE’s founder who is currently a UK child rights consultant.

Prior to the interview, respondents received full disclosure of the research project and permission to use the interview data was obtained. Due to COVID-19, interviews that occurred during 2020 and 2021 were conducted via video call or telephone. Initially, interviewees were asked generic questions to build a rapport. Subsequently, to reduce bias, interviewees were asked non-leading questions (Bryman Citation2004) relating to the domestic compliance system, compliance barriers and UNCRC compliance by the UK and its four nations. All interviews were transcribed verbatim. Braun and Clarke’s (Citation2006) six phases of thematic analysis were followed to provide sound methodological and theoretical foundations for conducting thematic analysis. Regarding compliance barriers, Weaver’s (Citation2014) framework informed the deductive analysis. However, to maintain flexibility, where necessary, themes that could not be anticipated by this framework were inductively developed to capture the complexity of compliance. Throughout the analysis, triangulation of data sources occurred; information obtained through the interviews was validated through policy documents / reports and vice versa (Patton Citation2000). Where conflicting opinions emerged, these were reported within the empirical analysis. Extracts from the interviews were incorporated into the empirical discussion to support the documentary analysis and provide evidence that was specific to the research aim.

4. Findings and discussion

4.1. Primary rule system

Although not required by the international primary rule system (the UNCRC), the Committee has repeatedly recommended incorporation of the UNCRC into UK law (Concluding Observations Citation2016). Adding to Weaver’s (Citation2014) compliance barriers framework, the domestic legal system emerged as a factor that explained the UK government’s failure to comply with the Committee’s recommendations and incorporate the UNCRC; the UK’s dualist system requires an act of parliament to include the UNCRC in the domestic legal order. Reflecting on dualism, the independent consultant argued that “treaties are quite often on the periphery of mainstream policy development and law” (Independent Consultant Interview). The political system has previously emerged as a factor that influences state compliance with international environmental accords (Jacobson and Weiss Citation1995).

Though previous research has suggested that implementing agreements is more important than adoption into the national policy system (Lele Citation2018), civil society actors perceived full UNCRC incorporation as a critical requirement of the primary rule system. Interviewees stated that incorporation would reduce legislative fragmentation between the devolved primary rules systems and avoid “watered down legislation” (Together Interview) and “cherry picking” (Children in Scotland Interview) of UNCRC rights. Contrary to the Committee’s guidance, inclusion of select UNCRC provisions is increasingly apparent amongst state parties (Kilkelly Citation2019). However, without incorporation, duty bearers arguably have “limited legal, policy or political imperative to act in accordance with the UNCRC” (CRAE Citation2017, 4). Reiterating Kilkelly’s (Citation2019) findings, incorporation was recognized as an important structure that contributes towards full realization of the UNCRC and translates its principles into government legislation and policy structures. Indicating the theorized relationship between the primary rule system and the non-compliance response system (), the absence of incorporation directly impacts, and in this case weakens, the state and devolved non-compliance response systems; without incorporation, the UNCRC remains nonjusticiable in UK courts (Children’s Commissioner Report Citation2020).

The primary rule system requires clarity (Mitchell Citation1996). In contrast, echoing an opinion expressed by the interviewees, the CRAE representative stated that UNCRC terminology can be “alienating” (CRAE Interview). Likewise, at the state and devolved levels:

work that comes out from governments and parliaments isn’t always the most accessible and traditionally, policies aren’t easily understandable. (WYPM Interview)

Despite the absence of incorporation, the Minister for the School System reaffirmed the UK Government’s commitment to give due consideration to the UNCRC when designing policy and legislation (Lord Agnew of Oulton Citation2018). Primary consideration of children’s best interests (Article 3) is one of the UNCRC’s (Citation1989) four general principles. However, civil society actors contend that there has been “little progress in enshrining children’s best interests as a primary consideration” when developing laws and policy (England Civil Society Report Citation2020, 9). This argument is supported by the government’s failure to introduce a statutory obligation to systematically conduct child rights impact assessments (CRIAs) when developing laws, CRIAs that are frequently absent or ex-post, and the lack of democratic scrutiny for children’s rights when developing legislation and policy (England Civil Society Report Citation2020). Notably, the Royal Courts of Justice (Citation2020), judged that the Secretary of State acted unlawfully by failing to consult the Children’s Commissioner and other bodies representing the rights of children in care before introducing the Amendment Regulations.

Capturing a sentiment repeatedly expressed within the third sector reports (Equality and Human Rights Commission Citation2020) and interviewees, the Wales Observatory representative referred to the “low prioritization of children’s rights”, “lack of political will” and “political resistance” amongst the UK Government (Wales Observatory Interview). Similarly, Anne Longfield (Citation2021) (former Children’s Commissioner for England), stated “too often I have to cajole people to the table”. Indicating the interplay between compliance barriers, cultural beliefs were perceived to influence political resistance towards incorporation and the prioritization of children’s rights:

the sanctity of the family is a cultural value within Wales, within the UK. There can be reluctance among politicians to intrude into that domain. (Wales Observatory Interview)

in the West there are cultural barriers to believing that children are subjects of rights, to believing that children are not the property of parents. (Child Rights Consultant Interview)

4.2. Devolved primary rule systems

Although the UK government has not incorporated the UNCRC, statutory delegation of powers has resulted in varied devolved primary rule systems. Legislative changes within Scotland and Wales were perceived to indicate greater levels of political will and exemplify that “people make a difference” (Jacobson and Weiss Citation1995, 126), with some political leaders demonstrating greater levels of commitment towards compliance. Within Scotland, greater levels of political will contributed towards a primary rule system that better complies with the Committee’s incorporation and statutory CRIA recommendations (Concluding Observations Citation2016). In 2021, the landmark UNCRC (Incorporation) (Scotland) Bill was unanimously passed, making Scotland the world’s first devolved nation to directly incorporate the UNCRC (to the maximum extent of the Scottish Parliament’s devolved powers) into Scottish Law (Scottish Government Citation2021). Although incorporation is recognized as a huge step, the limitations of legislation alone (Bafoil Citation2013; Jacobson and Weiss Citation1995) were recognized:

we are not under any illusions that incorporation is a golden bullet. (Together Interview)

Though not equal to Scotland’s incorporation progress, the Rights of Children and Young Persons (Wales) Measure 2011 partially incorporated the UNCRC into Welsh Legislation (Equality and Human Rights Commission Citation2020) and is “significant in terms of policy processes and policy thinking” (Wales Observatory Interview). The Measure enshrines children’s rights in Welsh law and has positively impacted how children’s rights are considered in policy development (Equality and Human Rights Commission Citation2020). Contrary to England and Northern Ireland, Welsh Ministers are required under the Measure to have due regard to the UNCRC. To evidence Minister’s compliance with the Measure, when developing and reviewing legislation and policy, CRIAs are used. Although 208 CRIAs have been published to date (Welsh Government Citation2020), the Welsh Parliament (Citation2020) acknowledged there is insufficient evidence that the Measure is exercised across the whole of the Welsh Government. Additionally, the Measure’s ability to address cultural belief barriers (Weaver Citation2014) that exist within Welsh policy making has been slow due to the “time it takes to change approaches and mindsets” (Welsh Parliament Citation2020, 25). The repeated emergence of cultural barriers contrasts with Avdeyeva’s (Citation2010) gender equality research, which did not identify culture as a key factor that determined the degree of government compliance.

Despite evidence of legislative progress, particularly within Scotland and Wales, domestic legislation alone does not guarantee state compliance (Bafoil Citation2013; Jacobson and Weiss Citation1995). Echoing this problem, the Child Rights Consultant stated:

there are wonderful regulations and laws. But sometimes, there’s no resources, no strategic support for it, no training of the professionals and so on. (Child Rights Consultant Interview)

Autonomy issues can hinder compliance (Weaver Citation2014). Capturing this challenge and reinforcing the impact of the political and legal system (Jacobson and Weiss Citation1995), devolution emerged as a barrier that creates autonomy problems and contributes towards resource constraints at the devolved level:

the Welsh government relies on a budget from the UK government. We need more money for children’s rights. If the English government says no, which it has done, what can the Welsh government do? (Wales Observatory Interview)

Regarding incorporation, England is “lagging behind other parts of the UK”, with incorporation of the UNCRC “a very long way off” (England Civil Society Report Citation2020, 6). Similarly, Northern Ireland lacks notable movement towards incorporation and does not legally require ministers to have due regard to the UNCRC (Children’s Commissioner Report Citation2020). Although not identified within Weaver’s (Citation2014) compliance framework, political instability emerged as a compliance barrier. Due to the collapse of the Northern Ireland Assembly, there was a three-year absence of strategic decisions to improve child rights and “delays in legislative and policy reform in critical areas” (Children’s Commissioner Report Citation2020, 2). Although incapacity barriers (Houlihan Citation2014; Mitchell Citation2001) emerged within all four nations, government collapse was a unique barrier that halted Northern Ireland’s legislative progress and contributed towards comparatively weaker levels of compliance. Like the state level, cultural barriers (Jacobson and Weiss Citation1995) to recognizing children as the subject of rights were perceived to hinder Northern Ireland’s legislative and policy progress:

some political parties don’t like the term rights, so we find other ways to get politicians on side without using the word. It is about ending child poverty, ending family poverty. Those kinds of ways are how we have to approach child rights. (NiCI Interview)

4.3. Compliance information system

“View of the child” (Article 12) is one of the UNCRC’s four general principles and requires that children’s views are heard, taken seriously and given due weight by the state party (UNCRC Citation1989). Interviewees unanimously expressed the importance of children’s views; children can provide an “incredibly eloquent, powerful and very different narrative to the one being promoted by adults” (Child Rights Consultant Interview) and their influence lies in “sharing their stories and experiences” (Children in Scotland Interview). The compliance information system must therefore eliminate structural opportunities for tokenistic and “tick boxing” consultations with children and young people. Instead, at the national, devolved and local levels, consultations must be replaced with meaningful participation where children’s opinions are not only sought, but used to shape the domestic primary rule system, including decision making, legislative and policy development (Children in Scotland Interview, Together Citation2019; NICCY Citation2018). This principle is embedded into the CRIA process; following data collection and child consultation, the CRIA results should be published alongside insight into how the data was considered during legislative and policy developments (Concluding Observations Citation2016). Article 12, combined with the CRIA process, evidences the proposed relationship between the primary rule system and the compliance information system (). Developing Mitchell’s (Citation1996) conceptualization, the findings indicate that the compliance information system transcends the provision of information regarding performance and compliance through feedback processes. Instead, the compliance information system requires the integration of bottom-up data collection processes, in addition to feedforward processes, that are used to inform and redesign national policy reflected within the state and devolved domestic primary rule systems.

Reducing state compliance with Article 12, at the national level, children’s views are not systematically heard by the UK government; improved structures that allow meaningful child participation in policy development, legislation and monitoring are required (Children’s Commissioner Report Citation2020; Equality and Human Rights Commission Citation2020). The UK government’s failure to prioritize children’s voices was identified as a barrier to embedding child participation into the compliance information system (Children’s Commissioner Report Citation2020). Within the interviews, cultural barriers to recognizing children as independent subjects re-emerged as a factor that hindered the prioritization of child participation in the compliance information system. Consequently, within England, meaningful structures for children’s views to be heard are missing and children are rarely taken seriously, causing children to report feeling voiceless in the policy making process (England Civil Society Report Citation2020; CRAE Interview). Similarly, Northern Ireland’s government was criticized for their lack of willingness to “listen properly” to children’s views and for paying “too much lip service to listening to young people” (Northern Ireland Commissioner for Children and Young People Citation2020).

Capturing the relationship between the compliance information system and the primary rule system that was proposed in , the UNCRC (Citation1989) intends for children’s voices to inform legislative and policy developments. However, in Northern Ireland, feedforward between the compliance information system and primary rule system is limited; data collection from children is not strongly embedded and exhibits limited influence on legislation and policy development (Northern Ireland Civil Society Report Citation2020). On occasions where children were involved in the data collection process, children and civil society actors criticized policy makers for failing to provide children with feedback regarding the impact of their participation (Children and Young Person’s Report Citation2020; LLM Human Rights Clinic Citation2019; Together Interview).

Positively, there is some evidence of increased recognition and acceptance of children’s voices (Children and Young Person’s Report Citation2020). Reflecting on cultural barriers to child participation in Scotland, the Children in Scotland representative stated:

in terms of that culture change, we are moving towards hearing children and young people more, but that is going to take some time. (Children in Scotland Interview)

Evidencing good practice in Wales, following the 2018 establishment of the WYP, in 2019, the National Assembly for Wales held a joint session with the WYP. Subsequently, a joint political declaration stated that the WYP’s work would be an important element of decision making in Wales. Referring to this declaration, the WYPM stated, “that was a turning point, this wasn’t tokenistic, decision makers committed to listen to what young people have to say” (WYPM Interview). Avdeyeva’s (Citation2010) research found that government compliance with international norms and positive legislative change is more likely when representatives from the target population of a human rights agreement (for example women), are included in parliament. Although the UNCRC target population (children) are not eligible parliament candidates, the WYP provides an opportunity to “bring young people’s views to the attention of the Welsh Parliament” (WYPM Interview).

Despite the importance of qualitative and disaggregated data (Concluding Observations Citation2016; Collins Citation2008), at the state level and within all four nations, the compliance information systems were criticized for insufficient levels of qualitative data (Together Citation2019; UNICEF UK Interview), inconsistent data and infrequent disaggregated data (Children’s Commissioner Report Citation2020; Scotland Civil Society Report Citation2020; Wales Civil Society Report Citation2020; Concluding Observations Citation2016). Such factors arguably make it “impossible to track progress” (Together Interview), limit the extent to which the compliance information system provides performance and compliance clarity (Mitchell Citation1996), and limit state compliance with Article 44 of the UNCRC (Citation1989), specifically the provision of sufficient information regarding progress. Creating an additional challenge, governments may overemphasize compliance success and downplay challenges (Collins Citation2008). The UNICEF UK representative recognized this problem:

if you look at the reporting process, a government says it’s complying, but a non-governmental organisation says it’s not. That’s the point of the process, to come at it from two opposing views and get a balanced view of what’s going on. (UNICEF UK Interview)

Although the primary responsibility for data collection in each country was perceived to lie with the devolved governments, third sector organizations also play a significant role in data collection due to their contact with children and young people (Wales Observatory Interview, Children in Scotland Interview). Therefore, organizational collaboration between the government and third sector organizations is an important component of the compliance information system. In contrast to the state level, cultural barriers did not hinder child participation in the data collection process. Instead, organizational operational capacity issues (Wu, Ramesh, and Howlett Citation2015), were repeatedly reported:

to do meaningful participation with children and young people you need a lot of time, resources and dedicated staff. That is a challenge. A lot of organisations don’t have a lot of resources. (Children in Scotland Interview)

4.4. Non-compliance response system

Within the child rights regime, non-compliant states are not subject to traditional enforcement mechanisms (e.g. sanctions, a right of action in an international tribunal) (Hollyer and Rosendorff Citation2011; Simmons Citation2009). Instead, the Committee makes recommendations to enhance state compliance. Unfortunately, the frequent ineffectiveness of Concluding Observations at initiating behavioural change (including, but not limited to, legislative / policy changes and extra resource allocation) has previously been reported within the human rights sector (Krommendijk Citation2015). Similarly, the UK government has failed to comply with several of the Committee’s recurrent recommendations (e.g. incorporation, statutory CRIAs and sufficient resource allocation). As discussed in the previous sections, lack of political will, low prioritization of child rights and cultural barriers primarily hindered behavioural change by the UK government. Although Concluding Observations rarely initiate behavioural change (Krommendijk Citation2015), the Concluding Observations facilitate public scrutinization of governmental policies, provide NGOs with an agenda for campaigning and create opportunities to engage in serious dialogue with the government regarding the state’s efforts to comply with the UNCRC (Together Citation2019). In response to the absence of formal enforcement mechanisms, campaigning by civil society actors has emerged as an integral informal non-compliance response. NGOs play a crucial role in compliance and have the potential to influence the political agenda (Jacobson and Weiss Citation1995).

At the devolved level, the Children (Scotland) Bill provides a notable example of organizational persistence and the subsequent impact of campaigning (Becker Citation2012). Although civil society actors positively reported greater evidence of political will amongst the Scottish Government, the importance of civil society campaigning in this legislative advancement is evident; the Bill was recognized as the culmination of more than a decade of collaborative efforts involving continuous persuasion and campaigning by civil society and children (Together Citation2019). The example supports Krommendijk’s (Citation2015) conclusion that without significant domestic mobilization, governments rarely introduce legislative changes recommended within the Concluding Observations. Additionally, the analysis supports the cyclical nature of the compliance system proposed in . In this instance, campaigning within the non-compliance response system resulted in legislative changes in the devolved primary rule system. Referring to this relationship, the independent consultant stated that the “children’s sector has been very effective at getting the UNCRC embedded into policy” (Independent Consultant Interview). The findings are in line with previous research in the human rights sector. Focusing upon gender equality, Avdeyeva (Citation2010) likewise identified the level of mobilization amongst civil society actors as a factor that can positively influence the degree of government compliance. However, similar to previous findings (Krommendijk Citation2015), civil society actors reported organizational operational capacity (Wu, Ramesh, and Howlett Citation2015) as a factor that hindered their policy capacity and ability to effectively engage in campaigning.

Despite Article 42, which requires that everyone knows about the UNCRC (UNCRC Citation1989), lack of awareness frequently prevents children (and other duty bearers) within all four nations from engaging in the non-compliance response system. Capturing this barrier, the Children in Scotland representative stated that “many children aren’t aware that they have rights” (Children in Scotland Interview). Children expressed a similar sentiment in the Children and Young Person’s Report (Citation2020). Awareness has previously been identified as a key factor that contributes to effective implementation of the UNCRC (Kilkelly Citation2019). To alleviate this problem, schools were identified as existing structures that could implement a nationally coordinated approach to awareness raising (Children’s Commissioner Report Citation2020). Beyond awareness raising, Koulla Yiasouma stated “we have a responsibility to make sure that they [children] understand what the tangible rights are” (Northern Ireland Commissioner for Children and Young People Citation2020). Regarding understanding, lack of clarity within the primary rule system creates cognition barriers (Weaver Citation2014) amongst children regarding their rights and the complaints procedure (Children’s Commissioner Report Citation2020; Scotland Civil Society Report Citation2020; WYPM Interview). This finding indicates that the empowerment of children must be at the heart of awareness building activities to leave children feeling knowledgeable enough to self-advocate and defend their rights through engagement in the non-compliance system (Together Citation2019).

Highlighting further challenges, financial barriers, specifically the scarcity of free legal advice for children (Equality and Human Rights Commission Citation2020) and inadequate structures (for example age-appropriate court services) (NSPCC Citation2019), hindered child participation in the non-compliance response system. Addressing barriers to children’s engagement in the non-compliance response system is essential to enhance compliance with the UNCRC’s (Citation1989) general principle, “voice of the child”. Indicating the interlinking nature of the compliance subsystems (), developing a more child friendly non-compliance response system requires the compliance information system to collect data regarding child participation in, and feedback regarding, the judicial process. However, the state and devolved compliance information systems fail to fulfil their objective of relevant data collection (Mitchell Citation1996); government statistics about such child participation is mostly unreliable or missing (NSPCC Citation2019).

5. Conclusion

The empirical analysis provided valuable insights into the domestic compliance system and compliance barriers within the under researched human rights sector. The findings confirmed that evaluating single barriers is likely to lead to a poor understanding of compliance; non-compliance is caused by a range of interlinking barriers (Weaver Citation2014). Although various compliance barriers were evidenced, the extent to which they impacted compliance, and emerged within the compliance systems of the four nations, varied.

Although the UK Government is the primary duty bearer, overall, lower levels of compliance were exhibited at the state level. At the state level, attitudinal and belief barriers (Weaver Citation2014) were widely reported. First, lack of political will and low prioritization of children’s rights emerged as barriers within, and weakened, all subsystems of the compliance system. Second, cultural barriers to believing children are autonomous agents who are the subject of their own rights, were evident within the primary rule and compliance information systems. Notably, the significance of cultural barriers contrasts previous compliance research within the human rights sector (Avdeyeva Citation2010). At the devolved level, the political system (Jacobson and Weiss Citation1995), in this case devolution, combined with the UK government’s failure to incorporate the UNCRC, contributed towards fragmentation between the devolved primary rule systems. Within England and Northern Ireland, attitudinal and belief barriers likewise hindered compliance. Although not identified within Weaver’s (Citation2014) compliance framework, political instability emerged as a compliance barrier; government collapse was a unique barrier that contributed towards Northern Ireland exhibiting one of the weakest devolved primary rule systems and lowest levels of overall compliance amongst the four nations. Overall, the greatest degrees of compliance were evidenced in Scotland and Wales. Advancements in the Scottish and Welsh devolved compliance systems were perceived, in part, to be the consequence of greater levels of political willingness within the respective governments. Although cultural barriers were still reported to exist in Scotland and Wales, cultural shifts demonstrated more successful (albeit slow) erosion of this barrier.

Additional compliance barriers emerged to a similar extent within all four nations. Consistent with compliance studies in different sectors, resource barriers emerged (Coban Citation2020; Weaver Citation2014; Houlihan Citation2014). Indicating the interplay between compliance barriers, resource constraints, in part, were intensified by the political system (Jacobson and Weiss Citation1995). Specifically, devolution created autonomy issues (Weaver Citation2014) regarding resource allocation. Amongst government officials and policy makers, analytical capacity problems (Wu, Ramesh, and Howlett Citation2015) (often exacerbated by inadequate training), emerged within, and reduced the strength of, the primary rule and compliance information systems. Information and cognition problems, financial resources (Weaver Citation2014) and inadequate child friendly structures, created barriers to compliance and hindered child participation within the non-compliance response systems. Although civil society actors were confirmed as important actors that can positively influence the degree of government compliance (Avdeyeva Citation2010), civil society contributions to the non-compliance response system (and the compliance information system), were limited by resource constraints.

Informed by the empirical analysis, this article advances previous linear conceptualisations of the compliance system (Mitchell Citation1996) and indicates that the domestic compliance system may be understood as a cyclical process; the three subsystems are interlinked and connected through feedback and feedforward (). Although these findings provide preliminary insights, from a theoretical perspective, the cyclical model of the domestic compliance system would benefit from further investigation. Given the lack of compliance research within the human rights sector, future research could also use different empirical settings (including alternative countries or human rights conventions), to explore the extent to which similar barriers to state compliance exist. In recognition that state parties often comply with some convention articles whilst violating others, future research could utilize the compliance system to evaluate barriers to, and compliance with, a specific UNCRC article. Comparative, cross-national research into domestic compliance systems may also identify policy approaches that could improve the UK’s UNCRC compliance.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to express gratitude to the interviewees who took their time to participate in this research.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are partially available from the University of Northampton Research Explorer at: 10.24339/412d7416-17b7-4119-9eb9-60d84aef6ac6. A subset of the data is not publicly available due to information that could compromise the privacy of research participants.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Stacie Gray

Stacie Gray is a senior lecturer and researcher in the Faculty of Arts, Science and Technology at the University of Northampton, UK. Broadly, her research interests lie in the policy sciences, with a particular focus upon compliance and implementation.

References

- Ansell, C., E. Sørensen, and J. Torfing. 2017. “Improving Policy Implementation Through Collaborative Policy Making.” Policy and Politics 45: 467–486.

- Avdeyeva, O. 2010. “States’ Compliance with International Requirements.” Political Research Quarterly 63 (1): 203–217.

- Bafoil, F. 2013. Resilient States from a Comparative Regional Perspective. Singapore: World Scientific Publishing.

- Becker, J. 2012. Human Rights Advocacy in Practice. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Braun, U., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101.

- Bryman, A. 2004. Social Research Methods. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Carter, D., and S. Siddiki. 2019. “Participation Rationales, Regulatory Enforcement, and Compliance Motivations in a Voluntary Program Context.” Regulation and Governance, 15 (2): 1–16.

- Children and Young People’s Report. 2020. “Are We there Yet?” Accessed May 8, 2020. https://cypcs.org.uk/wpcypcs/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/cco-are-we-there-yet-final.pdf.

- Children’s Commissioner Report. 2020. “Report of the Children’s Commissioners.” Accessed May 8, 2020. https://www.childrenscommissioner.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/cco-uncrc-report.pdf.

- Coban, M. 2020. “Compliance Forces, Domestic Policy Process, and International Regulatory Standards: Compliance with Basel III.” Business and Politics 22 (1): 161–195.

- Coffey, A. 2014. “Analysing Documents.” In The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Data Analysis, edited by U. Flick, W. Scott, and K. Metzier, 367–379. London: Sage Publications.

- Collins, T. 2008. “The Significance of Different Approaches to Human Rights Monitoring: A Case Study of Child Rights.” The International Journal of Human Rights 12 (2): 159–187. doi:10.1080/13642980801899626.

- The Committee. 2021. “Simplified Reporting Procedure.” https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/HRBodies/CRC/InfoNoteStakeholdersSRPDec2017.pdf [accessed 10.06.2021].

- Concluding Observations. 2016. “Concluding Observations of the Fifth Periodic Report of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland.” Accessed May 13, 2020. https://www.unicef.org.uk/babyfriendly/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2016/08/UK-CRC-Concluding-observations-2016-2.pdf.

- CRAE. 2017. “Barriers and Solutions to Using Children’s Rights Approaches in Policy.” Accessed June 21, 2020. http://www.crae.org.uk/media/123572/Barriers-and-solutions-to-using-childrens-rights-in-policy-E.pdf.

- CRAE. 2018. “State of Children’s Rights in England.” Accessed June 12, 2020. http://www.crae.org.uk/media/127101/B1_CRAE_EXEC-SUM_2018_WEB.pdf.

- England Civil Society Report. 2020. “England Civil Society Submission to the United Nations Committee.” Accessed January 5, 2021. http://www.crae.org.uk/media/129724/CRAE_LOIPR_09-DEC-20.pdf.

- Equality and Human Rights Commission. 2020. “Children’s Rights in Great Britain.” Accessed May 14, 2020. https://www.equalityhumanrights.com/sites/default/files/childrens_rights_in_great_britain_0.pdf.

- Farrell, H., and A. Newman. 2016. “The new Interdependence Approach: Theoretical Development and Empirical Demonstration.” Review of International Political Economy 23 (5): 713–736.

- Fugard, A. J. B., and H. W. W. Potts. 2015. “Supporting Thinking on Sample Sizes for Thematic Analyses: A Quantitative Tool.” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 18 (6): 669–684.

- Hathaway, O. 2007. “Why Do Countries Commit to Human Rights Treaties?” The Journal of Conflict Resolution 51 (4): 588–621.

- Hollyer, J., and P. Rosendorff. 2011. “Why Do Authoritarian Regimes Sign the Convention Against Torture? Signaling, Domestic Politics and non-Compliance.” Quarterly Journal of Political Science 6 (3): 275–327.

- Houlihan, B. 2014. “Achieving Compliance in International Anti-Doping Policy: An Analysis of the 2009 World Anti-Doping Code.” Sport Management Review 17 (3): 265–276.

- House of Lords’ Children’s Rights Briefing. 2019. “Children’s Rights in 2019.” Accessed June 20, 2020. https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/LLN-2019-0148/LLN-2019-0148.pdf.

- Howlett, M. 2018. “Matching Policy Tools and Their Targets: Beyond Nudges and Utility Maximisation in Policy Design.” Policy and Politics 46 (1): 101–124.

- Human Development Report. 2020. “Human Development Index.” Accessed February 12, 2020. http://hdr.undp.org/en/content/latest-human-development-index-ranking.

- Jacobson, H., and E. Weiss. 1995. “Strengthening Compliance with International Environmental Accords: Preliminary Observations from a Collaborative Project.” Global Governance 1 (2): 119–148.

- Kelly, T. 2009. “The UN Committee Against Torture: Human Rights Monitoring and the Legal Recognition of Cruelty.” Human Rights Quarterly 31 (3): 777–800. doi:10.1353/hrq.0.0094.

- KidsRights. 2016. “KidsRights Index.” Accessed February 3, 2020. https://files.kidsrights.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/04130820/The-KidsRights-Index-2016-Research-Report-1.pdf.

- KidsRights. 2021. “KidsRights Index.” Accessed January 5, 2021. https://files.kidsrights.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/03095317/KidsRights-Index-2021-Report.pdf.

- Kilkelly, U. 2019. “The UN Convention on the Rights of the Child: Incremental and Transformative Approaches to Legal Implementation.” The International Journal of Human Rights 23 (3): 323–337.

- Krommendijk, J. 2015. “The Domestic Effectiveness of International Human Rights Monitoring in Established Democracies. The Case of the UN Human Rights Treaty Bodies.” The Review of International Organisations 10 (4): 489–512.

- LeBlanc, L. J., A. Huibregtse, and T. Meister. 2010. “Compliance with the Reporting Requirements of Human Rights Conventions.” The International Journal of Human Rights 14 (5): 789–807.

- Lele, G. 2018. “Compliance Under the Fragmented Governance: The Case of ASEAN Economic Community Implementation in Four Indonesian City Governments.” Policy Studies 39 (6): 607–621.

- LLM Human Rights Clinic. 2019. “Children’s Rights Approach Report.” Accessed May 14, 2020. https://www.togetherscotland.org.uk/media/1302/crwia-report-group-a-214.pdf.

- Longfield, Anne. 2021. “Building Back Better.” Accessed March 21, 2021. https://www.childrenscommissioner.gov.uk/2021/02/17/building-back-better-reaching-englands-left-behind-children/.

- Lord Agnew of Oulton. 2018. “Written Ministerial Statement for Universal Children’s Day HLWS1064.” Accessed July 1, 2021. https://questions-statements.parliament.uk/written-statements/detail/2018-11-20/HLWS1064.

- Mitchell, R. 1996. “Compliance Theory: An Overview.” In Improving Compliance with International Environmental Law, edited by J. Cameron, J. Werksman, and P. Roderick, 3–28. London: Routledge.

- Mitchell, R. 2001. “Institutional Aspects of Implementation, Compliance, and Effectiveness.” In International Relations and Global Climate Change, edited by U. Luterbacher, and D. Sprinz, 221–224. Boston: MIT Press.

- Newman, A., and E. Posner. 2016. “Transnational Feedback, Soft law, and Preferences in Global Financial Regulation.” Review of International Political Economy 23 (1): 123–152.

- NICCY. 2018. “Statement on Children’s Rights in Northern Ireland.” Accessed June 12, 2020. https://www.niccy.org/about-us/our-current-work/statement-on-childrens-rights-in-northern-ireland/.

- Northern Ireland Civil Society Report. 2020. “Northern Ireland NGO Submission.” Accessed January 12, 2021. https://childrenslawcentre.org.uk/uncrc_report/.

- Northern Ireland Commissioner for Children and Young People. 2020. “Ad hoc Committee on a Bill of Rights.” Accessed July 1, 2021. http://data.niassembly.gov.uk/HansardXml/committee-22886.pdf.

- NSPCC. 2019. “Falling Short?” Accessed June 17, 2020. https://learning.nspcc.org.uk/media/1672/falling-short-snapshot-young-witness-policy-practice-full-report.pdf.

- Patton, M. 2000. “Enhancing the Quality and Credibility of Qualitative Analysis.” Health Services Research 35 (2): 1189–1208.

- Quaglia, L. 2019. “The Politics of State Compliance with International “Soft Law” in Finance.” Governance 32 (21): 45–62.

- Royal Courts of Justice. 2020. “Case No: C1/2020/1279.” Accessed June 11, 2021. https://www.judiciary.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/R-Article-39-v-SSE-judgment.pdf.

- Scotland Civil Society Report. 2020. “Children’s Rights in Scotland.” Accessed January 11, 2021. https://www.togetherscotland.org.uk/media/1767/together-loipr_final.pdf.

- Scott, J. 1990. A Matter of Record, Documentary Sources in Social Research. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Scottish Government. 2021. “Landmark for Child Rights.” Accessed March 16, 2021. https://www.gov.scot/news/landmark-for-childrens-rights/.

- Scottish Parliament. 2021. “Scotland Bill.” Accessed March 21, 2021. https://digitalpublications.parliament.scot/ResearchBriefings/Report/2020/11/2/The-United-Nations-Convention-on-the-Rights-of-the-Child–Incorporation—Scotland–Bill.

- Shafir, E. 2013. The Behavioural Foundations of Public Policy. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Simmons, B. 2009. Mobilizing for Human Rights; International law in Domestic Politics. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Thornton, D., N. A. Gunningham, and R. A. Kagan. 2005. “General Deterrence and Corporate Environmental Behaviours.” Law and Policy 27 (2): 262–288.

- Together. 2019. “State of Children’s Rights in Scotland.” Accessed May 14, 2020. https://www.togetherscotland.org.uk/resources-and-networks/state-of-childrens-rights-reports/.

- UNCRC. 1989. “Convention on the Rights of the Child.” Accessed March 1, 2020. https://www.ohchr.org/en/professionalinterest/pages/crc.aspx.

- United Nations. 2017. “Ongoing Child Rights Violations.” Accessed February 17, 2020. https://news.un.org/en/story/2017/01/549562-ongoing-violations-child-rights-highlighted-un-monitoring-body-opens-annual.

- United Nations. 2020. “Human Rights Day.” Accessed April 13, 2020. https://www.un.org/en/observances/human-rights-day.

- United Nations. 2021. “Convention on the Rights of the Child.” Accessed August 8, 2021. https://treaties.un.org/pages/ViewDetails.aspx?src=IND&mtdsg_no=IV-11&chapter=4&clang=_en.

- Wales Civil Society Report. 2020. “Wales Civil Society Submission.” Accessed January 12, 2021. https://www.childreninwales.org.uk/application/files/6116/1676/8681/All-Presentations-launch-of-report-event-10.12.20-compressed.pdf.

- Weaver, K. 2014. “Compliance Regimes and Barriers to Behavioural Change.” Governance 27 (2): 243–265.

- Welsh Government. 2020. “Children’s Rights Legislation.” Accessed June 12, 2020. https://gov.wales/childrens-rights-in-wales.

- Welsh Parliament. 2020. “Children’s Rights in Wales Report.” Accessed May 14, 2020. https://senedd.wales/laid%20documents/cr-ld13405-r/cr-ld13405-r-e.pdf.

- Winter, S. C., and P. J. May. 2001. “Motivations for Compliance with Environmental Regulations.” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 20 (4): 675–698.

- Wu, X., M. Ramesh, and M. Howlett. 2015. “Policy Capacity: A Conceptual Framework for Understanding Policy Competences and Capabilities.” Policy and Society 34 (3–4): 165–171.

- Yan, H., J. Heijden, and B. Rooij. 2017. “Symmetric and Asymmetric Motivations for Compliance and Violation: A Crisp set Qualitative Comparative Analysis of Chinese Farmers.” Regulation and Governance 11 (1): 64–80.