ABSTRACT

While extensive research has shown that policy outputs are punctuated, there is a paucity of research about the punctuation of public opinion and political participation. We know policymakers rely on political participation to understand public opinion, so we need to understand the patterns and flows of this participation, to help understanding democratic responsiveness, and how policy outputs behave. I advance punctuated equilibrium theory by applying it to individuals’ decision to participate, and the policy issue they choose to engage with. I argue that bounded rationality and disproportionate information processing, driven by media and interest group coverage of trigger events, will result in a punctuated equilibrium pattern in both the decision to participate and the issues focused on. Using new datasets on the volume and topic of letters to the Australian Prime Minister and American President, I find consistent evidence of punctuations, using weekly, fortnightly, and annual data, across Australia and America, notwithstanding institutional, cultural, and behavioural differences. These results extend punctuated equilibrium further up the policy process chain than has previously been done, supporting its claim as a “full theory of government information processing.” Doing this helps us to understand the difficulty in translating environmental and public demands into policy.

Introduction

Punctuated equilibrium research covers a wide range of policy inputs and outputs, but this theoretical concept has yet to be applied to political participation. This article finds that the same punctuated equilibrium patterns that are well known in policy outputs, are also evident in political participation. These findings respond to the call from Baumgartner et al. (Citation2009) to identify the levels of punctuation in political inputs, which can help to understand why there is such difficulty in translating external environmental demands and public demands into public policy.

Every year, thousands of people participate in politics: writing letters; joining campaigns; attending protests. People participate because they want to have an impact, (Verba and Nie Citation1987) and policy is expected to be responsive, not just to public opinion, but also to external environmental signals. “Perfect” responsiveness would mean that policy responded proportionately to the plethora of changing input signals (whether those signals be public opinion; changes in unemployment; COVID cases; or farm gate prices), with policy being constantly tweaked in response to these stimuli. This does not occur, instead, scholars have found long periods of relative equilibrium, followed by sudden jumps/shifts, to “catch-up” with changes in the environment (Baumgartner et al. Citation2009). This “punctuated equilibrium” pattern is based on the impact of individuals’ – and therefore institutions’ – inability to be comprehensively rational (Workman, Baumgartner, and Jones Citation2022; True, Jones, and Baumgartner Citation2014; Koski and Workman Citation2018; Eissler, Russell, and Jones Citation2016; Jones and Baumgartner Citation2012; Baumgartner et al. Citation2009). In this paper, I use letter writing to political leaders to examine whether the same patterns are present in political participation.

Punctuated Equilibrium Theory (PET) seeks to be a “full theory of government information processing” (Workman, Jones, and Jochim Citation2009, 75), to understand the pattern of policy change. While it was built on theories of individual decision-making (Jones and Baumgartner Citation2005b), it is yet to be extended to individuals’ decisions to participate in politics. This paper advances PET by applying it to individuals’ decision to participate in politics – a key input into policy change. I also show that PET can be applied using different time scales (weekly; fortnightly; and yearly). I do this using a new dataset on the volume of letters to the Australian Prime Minister, as well as leveraging existing data on letters to the American President. I argue that just as a political system must divide its attention between a myriad of policy issues, an individual must also divide their attention, except what is competing for attention isn’t specific policy issues – rather politics is competing for attention with home repairs, demands from work, or a family health crisis.

This article starts by showing why these letters can improve our understanding of responsiveness and democracy. It then sets out PET and presents my theoretical expectations. I argue that the punctuated equilibrium pattern will be present in the rate of political participation, but will be less pronounced than that found in institutional settings. I then set out my data and empirical approach, present my findings and discuss their implications.

Letters, responsiveness & democracy

Letters to leaders have not been the subject of significant scholarly research, despite the significance of this form of communication and the inherent link between democracy and the expression of public opinion. People write to their leaders to express dissatisfaction, seek redress, or seek change. Initially conceived as “petitioning the king,” there is evidence of such activities as far back as the eleventh century, and was established as a “right” as early as the Magna Carta in 1215 (Smith Citation1985).

Normatively, democracy requires a level of responsiveness between policy and public opinion. However, public opinion can only be heard when it is expressed. While media, and most researchers focus on opinion polls (Beyer and Hänni Citation2018), politicians listen to the public in many different ways (Henderson et al. Citation2021; Hooghe and Marien Citation2012). For individuals, letters are a relatively easy way to express their opinion. If someone has decided to devote time and resources to contact a politician, it demonstrates a level of intensity of feeling (Lee Citation2002). Given that politicians use these letters as one way of understanding public opinion (Rottinghaus Citation2012; Dexter Citation1956; Sussmann Citation1959), understanding them provides an additional step to understanding democratic responsiveness.

The letters are also a demonstration of the public (or interest groups) attempting to expand the “scope of the conflict” (Schattschneider Citation1960). The topics of these letters reflect the “conflict between competing definitions of what was politically relevant” (Mair Citation1997) and the volume of the letters demonstrates the number of “spectators” in the “crowd” that the protagonists have been able to attract into the “fight” (Schattschneider Citation1960). For example, there were almost 2000 letters to Prime Minister Howard on various animal welfare issues. Animal welfare was often considered a private issue, a matter for farmers, industry and consumers, rather than government regulation (Routledge-Prior Citationforthcoming) and did not appear much in the media. Thus, these letters are an attempt to get this issue onto the political agenda. Mobilizing the public, through petitions, letter-writing campaigns or protests is a standard tactic for expanding the conflict (Olofsson Citation2022; Schattschneider Citation1960), particularly for those on the “losing” side of the debate.

Punctuated equilibrium theory – how bounded rationality impacts policy outputs and political participation.

While policy is expected to be responsive, for “perfect” responsiveness to occur, both individual decision-makers, and the institutions that they are part of, would need to be “comprehensively rational,” (Lindblom Citation1959) almost constantly reviewing the situation around them, reviewing the costs and benefits of each policy option, and seamlessly changing policies with minimal search or transaction costs. The problems associated with these assumptions are extensively set out in the literature (Shannon, McGee, and Jones Citation2019; Jones Citation2017, Citation2003, Citation1999) – people, institutions and the political process are not able to react smoothly to the environmental signals around them. Instead, individuals’ cognitive processes create limits, or “bounds” on their rationality.

Even as the world is changing, we can only adapt when we pay attention. However, both individuals and institutions have a limited attention scope – individuals and institutions are constantly bombarded with information that may be relevant to decisions, political opinions, and policy options – and neither individuals nor institutions have the cognitive ability to collect, assemble, interpret and act on each one of those (Jones and Baumgartner Citation2012). Instead, issues need to be prioritized and addressed serially.

Governments deal with this limitation by creating sub-institutions, or subsystems (such as departments, committee systems, etc.) which can handle issues in parallel. Most of the time, most issues are handled within these subsystems. While policy is controlled within a subsystem, existing players, interest groups and institutions manage the policy. In these periods, changes are likely to be minimal, as an “equilibrium” has been established between the dominant players. These issues are unlikely to come onto the public agenda, or the agenda of a Prime Minister/President, and instead are managed by Ministers/Secretaries, or public servants (True, Jones, and Baumgartner Citation2014).

However, occasionally a policy issue can break free of a subsystem and move from the micro to the macro – onto the public agenda, the legislative agenda, and the Prime Ministerial/Presidential agenda. These periods represent an opportunity for major policy change, or “punctuation” and are usually caused by a change in attention, potentially due to an external shock (e.g. 9/11 or the Global Financial Crisis); or a re-framing of an issue; or an expansion of the conflict as new participants enter (Schattschneider Citation1960; Eissler, Russell, and Jones Citation2016). These exogenous shocks are often precipitated by the media and it is media coverage that leads to the changing attention of both the public and political elite (Holt and Barkemeyer Citation2012; Walgrave and Varone Citation2008).

This occurs because individuals and decision-makers are too often “locked” onto one particular indicator, or source of information, rather than relying on a broad source of data. Jones and Baumgartner (Citation2005a) demonstrated that the central limit theorem means that if individuals or decision-makers pay roughly equal attention to a broad range of indicators, (even if none of them were normally distributed themselves), the result would be a normal distribution of outputs. However, if the output series is leptokurtic, it provides prima facie evidence of bounded rationality, because the cause of this stochastic pattern is disproportionate information processing, or “indicator lock,” where decision-makers are too focused on one metric/“voice”, rather than paying attention to all relevant factors. The result is that “suddenly decision makers recognize that previously ignored facet of the environment are relevant and scramble to incorporate them” (Jones and Baumgartner Citation2005a, 334).

An issue getting onto the agenda (“attention allocation”) is only the first stage in what Jones and Baumgartner (Citation2005b) termed “the logic of choice”, which is then followed by “problem definition,” “alternative generation” and then finally “choice.” Each stage incurs decision, transaction, and opportunity costs. In an institutional setting, there are also “institutional costs”, which are based on the institutional rules and requirements for decisions to be made. These costs will vary across stages of the policy process and institutional arrangements. The institutional costs of a budget decision are likely to be higher than the institutional costs of asking a question in PMQs, or of introducing a bill by an individual legislator (True, Jones, and Baumgartner Citation2014; Baumgartner et al. Citation2009). Similarly, rules around super-majorities or customs around party-line voting will also change institutional costs. These costs create “friction” and mean that there isn’t a linear response to changes in the environment (Jones and Baumgartner Citation2012). The greater the friction/costs, the greater the force needed to start any sort of movement (Jones and Baumgartner Citation2012).

Since being first identified in the United States of America (Baumgartner and Jones Citation1991), the research has spread significantly: across countries and regions (e.g. USA, France, Hong Kong, Turkey, Russia and the EU – see Yildirim [Citation2022]); across different regime types (Baumgartner et al. Citation2017; Chan and Zhao Citation2016; Lam and Chan Citation2015); across policy areas (tobacco (Givel Citation2006), foreign policy (Joly and Richter Citation2019), drug policy (Rychert and Wilkins Citation2018) and policy disasters (Fagan Citation2022)); and across stages in the policy process (election results, media coverage, party platforms, bill introductions, hearings, budgets – see Baumgartner et al. (Citation2009)).

The impact of media and interest groups

The power of the media to influence the agenda has been extensively studied, famously summarized by Cohen (Citation1963), who said that the media “may not be successful much of the time in telling people what to think, but [they are] stunningly successful in telling its readers what to think about.” This agenda-setting power is part of the theoretical basis of punctuated equilibrium, as it recognizes that punctuations often require a “focussing event,” which is often dependent on media coverage (Walgrave and Varone Citation2008; Holt and Barkemeyer Citation2012). Case studies of punctuations have found that the media was a key factor driving the attention change that is the sine qua non of PET (Fagan Citation2022; Jennings et al. Citation2020). Individuals and governments generally “do not directly assess social processes, but become aware of them only as they are manifested” through the media, interest groups, or public opinion (Baumgartner et al. Citation2009).

Interest groups also have a particular function within PET, helping to maintain equilibria as part of a policy subsystem, but at other times seeking to bring attention to an issue, leading to a punctuation (McFarland Citation2010). Interest groups can attempt to draw attention to an issue in a variety of ways, from behind-closed-door lobbying to active media engagement, or letter-writing campaigns. For individuals with a particular interest in a policy area, relying on their preferred interest group is a form of “delegating to a subsystem,” allowing the interest group to monitor the environment and using the interest group’s views as a heuristic for their decision-making.

Applying punctuated equilibrium to citizen initiated contacting

Having set out the broad principles of PET, why I expect it to apply to decision-making of individuals, and how the media and interest groups feed into punctuated equilibrium, I now turn to why I expect to find punctuations in political participation in general, and in the letters, in particular.

The intellectual underpinning of bounded rationality were set out Simon (Citation1950), who sought to apply the limits of individuals’ cognitive processes to the decision making processes of organizations, but “bounded rationality is rooted in individual decision-making processes” (Viale Citation2017, 599). While most existing PET research focuses on the change in attention within institutions and between various policy issues, the underlying bounded rationality theory applies much more broadly, as the cognitive limitations are not unique to governments – they are inherent in human psychology (Jones Citation2001). This has allowed PET to be used to study stock market returns, currency valuations and CO2 emission (Epp Citation2015). PET has also previously been used to study patterns of political behaviours. Baumgartner et al. (Citation2009) use data on demonstrations and the change in voter preferences in the USA, Denmark and Belgium; Stadelmann and Torgler (Citation2013) use bounded rationality to study voting patterns in Swiss referenda; and Goerres (Citation2009) uses “limited rationality” to study political participation in Europe. Thus, PET is a viable framework whenever individuals are faced with a decision that may be subject to “bounded rationality.”

The scarcity of an individuals’ attention, just like the scarcity of an institutions’ attention, means that the same “logic of choice” will also apply to individuals who must juggle the many aspects of their lives. While in most PET research, the items competing for attention are different policy areas, in this study, politics/policy compete with other aspects of individuals’ lives. An individual “cannot balance one’s checkbook, work out at the gym, pay attention to family, write a book, and teach a class all at the same time” (Jones and Baumgartner Citation2005b, 34), or in this study “and write a letter to the President all at the same time.” While individuals don’t have congressional committees to delegate to, individuals have their own subsystems, allowing them to choose how much time to devote to issues. For example, food and nutrition and the education for children are two issues that may jockey for an individual’s attention, but can be delegated to a subsystem. Getting meals delivered from Snap Kitchen is delegating to subsystem, or a decision about whether to be involved in the local school board is a decision about the level of delegation to a subsystem. For people’s politics, most of the time they delegate it to political representatives, and individuals take little or no part in it, beyond voting at elections (Schumpeter Citation1987).

Regardless of an individual’s initial decision, their attention may be forced back to that issue. This could either be because a gradual drift means your earlier decision longer aligns with the external environment, or because of an exogenous shock – perhaps the quality of Snap Kitchen has been slipping, or their vegetarian partner has moved in. In these cases, an issue can break free of a subsystem and move to the macro – onto someone’s personal agenda, forcing them to reconsider their choices and take action.

The idea that people only pay limited attention to politics is unsurprising and uncontroversial, in Dahl’s famous terms, it is there mere “sideshow” in the “circus” of their lives (Dahl, in Jones Citation1994), it “pass[es] by unnoticed most of the time… under ordinary circumstances, political attention is discretionary” (Iyengar, in Jones Citation1994). Even while most people ignore the political, every day they are being bombarded with politically relevant information – access to childcare; price increases at the supermarket; changes to their employment can all be relevant to one’s political views, and whether one chooses to participate in politics. For most individuals, most of the time, this cacophony of political inputs is filtered out, because they do not have the mental “bandwidth.” In summary, “signals are ignored, responses are delayed” (Jones and Baumgartner Citation2005b).

While people tend to ignore politics, at some point, their attention is dragged onto a political issue, and they decide to participate – by writing a letter, picking up the phone, or voting. Because politics is a lower priority for most people, their attention to politics is often based on a heuristic – they have been encouraged to participate by their preferred media source or interest group. Tversky and Kahneman suggest that individuals use these heuristics so that they can “behave like actors who have more knowledge of the processes and alternatives” (Viale Citation2017) – they delegate the information gathering role to a perceived expert. When an actor (such as the media, or an interest group) encourages numerous people to pay attention and participate, it results in disproportionate information processing, not just at an individual level, but at a societal level. This explains the significant spikes, or “positive feedback loop” which is a signature of PET. This behaviour, like in institutions, should lead to the punctuated, leptokurtic patterns in the volume of letters, because the same underlying bounded rationality is at work. This leads to the first hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1 The change in the total volume of letters follows a punctuated equilibrium pattern

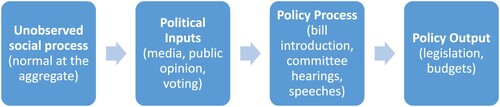

Figure 1. Adapted from Baumgartner et al. (Citation2009).

The driving feature in determining the level of punctuation is the level of friction (Baumgartner et al. Citation2009). Political inputs, such as deciding to write a letter, have less friction than any actual government policy process, or policy output. This should lead to a lower level of punctuation in the letters compared to actions with a higher level of institutional friction (Baumgartner et al. Citation2009). I can directly compare my findings on the level of punctuation in letters to America presidents with existing America PET data. While there is limited Australian-specific PET data (Dowding and Martin Citation2017), my results can be compared to international results, as Baumgartner et al. (Citation2009) found that any cross-country differences were “swamped” by the institutional friction effects, so there was a high level of constancy within each stage of the policy process across the countries studied, and consistent increases in the level of punctuation as the empirical domain moves from inputs, to policy processes, to budgetary outcomes. I therefore expect a similar level of punctuation as election results and other political inputs.

Hypothesis 2: The level of punctuation in the total volume of letters will be similar to other policy input processes, but will be less punctuated than policy processes or policy outputs

Hypothesis 3: The level of punctuation in the pooled topics of letters will be higher than is seen in institutional settings

Data and methods

The Australian Prime Minister receives around 150,000 letters each year (a rate of ∼110 letters per 10,000 adults) (Casey Citation2022). While it is hard to ensure comparability, Sussmann (Citation1963) reports that, for every 10,000 literate adults, President Truman received around 104 letters and President Eisenhower received 103 letters. However, there is very little quantitative research, and none that I have identified that has developed a dataset on the volume and topic of letters.

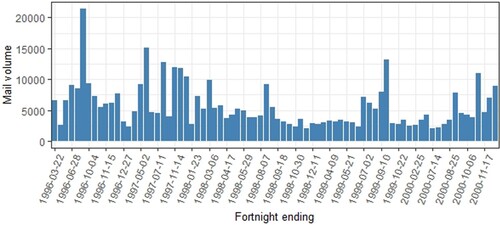

I focus on Prime Minister John Howard, Australia’s 25th Prime Minister, serving almost 12 years in office for the Liberal Party (a centre-right party), from March 1996 to December 2007 – however this research covers until June 2001, due to data access restrictions. During this period, he received more than 575,000 letters from members of the public. Almost half of these letters were classified as “pro-forma campaign letters,” where the exact same, or similar, text is sent by multiple people, and were usually driven by interest groups. The number of letters Mr Howard received per fortnight varied significantly, from a low of around 2,000 letters, up to a maximum of more than 21,000 letters, with a mean of around 5,500 letters per fortnight (). The peaks (August 1996, May/June 1997, November/December 1997, and September 1999) relate to childcare; chicken meat imports; global warming; and the Indonesian invasion of East Timor, and subsequent Australian-led UN intervention.

The top topics of the letters are set out in . We could take a case-study based approach to analyse what “caused” each spike in the volume of letters – in many cases it is likely to be a combination of external events; interest group activity and/or media attention. However, like Jones and Baumgartner (Citation2005b) and Lundgren, Squatrito, and Tallberg (Citation2018) my interest is not in identifying causes for individual changes, but rather explaining the overall pattern of letters – “it is the distribution we want to understand, not the historically contingent particulars” (Jones and Baumgartner Citation2005b, 114).

Table 1. Top topics of the letters.

To do this, this paper draws together three datasets of letters to political leaders. The main dataset is new, derived from research at the National Archives of Australia (NAA) (National Archives of Australia Citation1996–2007). Each fortnight, Mr Howard received a brief from his department, setting out the total amount of mail received in the previous fortnight, as well as details of the topics where he had received at least 30 items of correspondence. The public service categorized approximately 50% of the letters into topics, with the remainder either being “particularised contact” (Verba and Nie Citation1987), where the individual is seeking specific help, or where less than 30 people wrote on that topic in that fortnight. Topic names are taken directly from this archival source. These topics were then manually coded against an amended Australian version of the Comparative Agendas Project (CAP) codebook (Bevan Citation2019; Martin et al. Citation2014; Dowding and Martin Citation2017).Footnote1

Two additional datasets were used to test the hypothesis across different timeframes and institutional settings. Firstly, an annual data series from annual reports of the Australian Government’s Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (PM&C) (Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet Citation1979–Citation2022). Finally, weekly data for Presidents Reagan, Carter and Ford (Rottinghaus Citation2012) is also used.

To test these hypotheses, I use weekly (US Presidents), fortnightly (Mr Howard and US presidential aggregated to fortnightly) and annual (Australian Prime Ministers) data, and across two jurisdictions with different institutional arrangements. This differs from the “standard” PET approach, of using annual data. However, as Dowding and Martin (Citation2017) note, the choice of timeframes is arbitrary, and alternate time periods have increasingly been used in PET research, including weekly changes in COVID-19 restrictions (Shafi and Mallinson Citation2022); quarterly changes in European central bank agenda (Cross and Greene Citation2020); and quarterly changes in topics in Chinese newspapers (Meng and Fan Citation2022). By using multiple different timeframes on the same empirical domain, I can both ensure that any punctuated pattern is not solely an artifice of the measurement period, and thus demonstrate that different timeframes can usefully be used in PET research.

To test my propositions, I adopt two related approaches to measuring the change in the volume of letters. Traditionally the level of punctuation has been demonstrated by the level of leptokurtosis in the distribution, using L-kurtosis (Baumgartner et al. Citation2009). Kurtosis is a measure of the “fatness” of the tails, and the “peakiness” of the centre of a distribution, compared to a normal distribution, it therefore helps to identify if there is an excess of both extreme-change and nil-change observations. The higher the kurtosis, the greater the number of extreme observations. A normal distribution will have an L-kurtosis of 0.123, and anything over that is considered leptokurtic and evidence of punctuated equilibrium. The very presence of a leptokurtic distribution is the evidence of disproportionate information processing, resulting from bounded rationality (Jones and Baumgartner Citation2005a, Citationb).

Secondly, the Gini co-efficient maybe a useful additional statistical test for punctuated equilibrium, as it is an effective measure of dispersion, or inequality – in this case, the inequality in the size of the policy changes (Kaplaner and Steinebach Citation2022). A Gini co-efficient of 0 would reflect that every change was of an identical size (a uniform distribution), while a co-efficient of 1 would mean that all the change observed occurred in 1 observation and the other observations would have zero change. A normal distribution would have a Gini co-efficient of 0.414, if a Gini co-efficient above this, it is evidence of punctuated equilibrium (Kaplaner and Steinebach Citation2022). While some of the datasets have sample sizes that are smaller than most other PET research, other research has used annual change over short time periods (e.g. 10 years of annual media coverage, or changes over two elections [Baumgartner et al. Citation2009]). L-kurtosis is a robust measure of normality with small sample sizes of 50–70 (Jain and Ramu Citation2022; Malá, Sládek, and Bílková Citation2021) and the Gini co-efficient is robust with even smaller samples (Davidson Citation2009). Kaplaner and Steinebach (Citation2022) tested it with sample sizes of 50, and found it is more robust than L-kurtosis. The Gini co-efficient also has a downwards bias in small samples (Deltas Citation2003), which means that any errors in this study are more likely to be false negatives, rather than false positives. In addition, to provide added assurance to the robustness of the findings, 95% confidence intervals have been calculated for the Gini co-efficient using a bootstrap method (Berger and Balay Citation2020).

In addition to these quantitative measures, consistent with Baumgartner and Jones (Citation1993) and Walgrave and Varone (Citation2008), I also undertake qualitative analysis of two specific issues, and examine the spikes in mail volume that they resulted in. This qualitative analysis helps to elaborate on how the causal mechanisms proposed by punctuated equilibrium have resulted in the empirical patterns identified.

Results

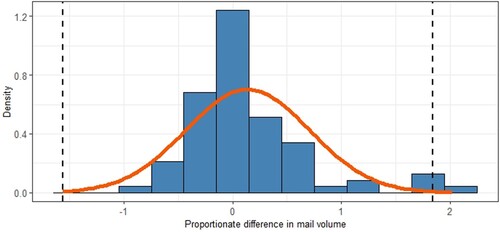

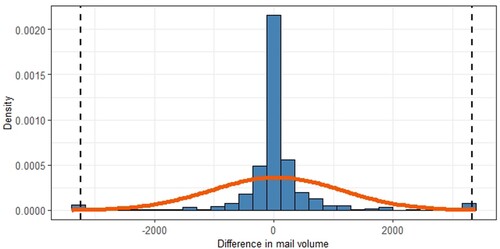

Starting with hypothesis 1, that the change in the total volume of letters follows a punctuated equilibrium pattern. plots the proportionate change distribution of the volume of letters received by Mr Howard. The proportionate change is calculated consistent with Workman, Baumgartner, and Jones (Citation2022) of (Policyt – Policyt-1)/Policyt-1. This creates a natural lower limit of −1. A normal distribution would have an L-kurtosis of 0.123 and a Gini co-efficient of 0.414.

As expected by hypothesis 1, it demonstrates a very high peak, representing a high number of fortnights with minimal change, well above the expected by the normal distribution. Twenty-four observations (almost 25 per cent) have a change of less than 10 percent. However, there is also a very high standard deviation (0.517), which demonstrates the large number of large changes (Fernández-i-Marín et al. Citation2022). Finally, almost 3% of the observations are more than 3 standard deviations above the mean, compared with the 0.15% expected, with a change of more than 165%, creating fat tails. This creates a leptokurtic distribution, with an L-kurtosis of 0.2497 and a Gini co-efficient of 0.516. This supports hypothesis 1.

To confirm these fortnight-based results, similar tests were undertaken on the other datasets. Firstly, an annual comparison was undertaken, covering the period 1981–2022 (which includes the 5 years of fortnightly data analysed above). This period covers 9 Prime Ministers, approximately 45% of the period was Labor (centre left) governments, and the remainder was Liberal/National coalition (centre right) governments. The average volume of letters per 10,000 people is roughly similar across Prime Ministers. Separate analysis not reported here shows there is no statistically significant difference between Labor and coalition Prime Ministers, or between election years and non-election years, or early in a Prime Minister’s term and later in that term (Casey Citation2022). This annual dataset has an L-kurtosis of 0.2495 (almost the same as the fortnightly data above), and Gini co-efficient of 0.475 – in both cases above the thresholds for leptokurtosis.

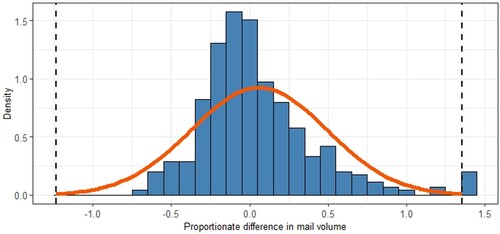

Next, using weekly data from the White House for 1973–1984 produces an L-kurtosis of 0.254 and Gini co-efficient of 0.509, which is displayed in . Like the data above, approximately 25% of the observations display changes of less than 10%, while there is a very high standard deviation (0.43), and there are almost 2% of observations more than 3 standard deviations above the mean, with a change of more than 135%, creating fat tails. As an extra robustness check, the original weekly data was aggregated to create a fortnightly timeseries, to enable a direct comparison to the Australian fortnightly data. This results in a similar leptokurtic pattern, with an L-kurtosis of 0.241 and Gini co-efficient of 0.504.

Figure 4. Weekly presidential mail volume: Ford to Reagan (with normal curve and 3sd indicated).

Note: for ease of visualization, all observations beyond 3sd were aggregated at 3sd.

These findings are summarized in . All the datasets support hypothesis 1, that changes in total volume of letters follows a punctuated equilibrium pattern, and none of the confidence intervals for the Gini co-efficient cross the threshold value of 0.414. The consistency of this finding using weekly (presidential data), aggregated fortnightly (presidential data), fortnightly (Mr Howard), and annual data (Australian Prime Ministers), is striking, especially given the significant institutional and cultural differences between Australia and America. It also demonstrates the potential of using different time intervals in PET research.

Table 2. Summary of Kurtosis and L-kurtosis for changes in mail volumes.

Next, I turn to comparing the leptokurtosis of these letters, compared to other policy processes. In hypothesis 2, I suggested that letters from members of the public should be closer to normal (display a lower L-kurtosis and Gini co-efficient) than other policy processes. This is because a decision to write a letter has lower levels of friction than activities undertaken within a political institution. Thus, it is likely to be similar to other modes of political participation, such as elections, but lower than activities within government, where institutional friction and decision costs are also a factor. Existing research has found that American election results have L-kurtosis scores of 0.25 (presidential), 0.30 (US House of Representatives) and 0.22 (US Senate) (Baumgartner et al. Citation2009). The L-kurtosis of letters to the US President (0.254) is similar, which supports hypothesis 2. Punctuated equilibrium research on elections in other countries have found L-kurtosis scores of between 0.14 and 0.30 (Baumgartner et al. Citation2009). The Australian data sits within this range, also supporting hypothesis 2.

Finally, turning to hypothesis 3, which suggests that the level of punctuation in the pooled topics of letters will be higher than is seen in institutional settings. Yildirim (Citation2022) noted that average L-kurtosis for public budgets of 0.475 and other institutional series of 0.290. Given that institutions, to some extent, help to overcome “individuals’ inability to process information” within any particular domain (in this case, policy issues), I expect similar or higher levels of punctuation at the topic level, consistent with Yildirim (Citation2022) who found an L-kurtosis score of 0.647 for changes in public attention, as measured by public opinion surveys.

As can be seen in , when measured at the topic level, this displays a highly leptokurtic distribution, with an l-kurtosis of 0.594 and a Gini co-efficient of 0.749,Footnote2 which is consistent with the findings of Yildirim (Citation2022). There are also 14 observations out of 770 beyond 3 standard deviations (∼3 per cent), significantly more than would be expected in a normal distribution. This is consistent with hypothesis 3.

Figure 5. Mr Howard's fortnightly mail – change in topics (pooled).

Note: for ease of visualisation, all observations beyond 3sd were aggregated at 3sd.

A closer look at individual topics

Most of the spikes in the mail volume can be attributed to specific topics, in the same way that most punctuations in policy output can be explained by specific trigger events, such as the Bhopal chemical spill, the Rio climate change conference (Holt and Barkemeyer Citation2012), or a heinous crime that attracted national attention (Walgrave and Varone Citation2008).

The fact that many of top topics in the mailbag can be directly traced back to external crises; media frenzies; or interest groups supports the conclusion that punctuated equilibrium dynamics are driving the pattern. As set out above, punctuated equilibrium hypothesizes that, given a normal distribution of inputs, if there is a leptokurtic distribution of outputs (as has been found in this case), this is due to disproportionate information processing, including “indicator lock” – rather than responding to the underlying risk or issue, people respond to a sudden “crisis.” In these cases, we can identify which “indicators” the public are “locked” onto (the media and interest groups), rather than the underlying issue. Two brief case studies will help to demonstrate this.

Firstly, deaths in custody of Australia’s First Nations peoples has been an ongoing issue for at least three decades and was the subject of a Royal Commission in 1991 (Cunneen Citation2001). There was a spike of 2300 letters in September/October 1997. Both prior to that, and after that, the issue did not appear. However, looking at the external environment, 1997 was the year with the lowest number of deaths in custody during the period of study. Over the subsequent 4 years, the number of deaths increased – but the mailbag remained silent. The trigger for these letters appears to be a major ministerial-level summit on deaths in custody in July 1997, (Cunneen Citation2007) which attracted significant media attention. This shows how the letter-writing dynamic is separate from the underlying problem, and instead linked to a focussing event and media coverage. If the expression of public opinion responded proportionately to the problem, the volume of letters would have reflected the changes in the number of deaths. Instead, we see disproportionate information processing, creating a punctuated equilibrium pattern.

Secondly, the question of allowing dual citizenship, which Mr Howard specifically identified as an area where he was influenced by public opinion. Australians were not able to hold dual citizenship prior to 2002, and this restriction was one of the “most contested and contentious areas” of the Citizenship Act (Nolan and Rubenstein Citation2009). Dual citizenship is an important issue in Australia, because of the large proportion of Australians who were born overseas and may be eligible for dual citizenship (Brown Citation2002). Despite the relevance of the issue for a large minority of the population, without a trigger event, it did not get onto the agenda. However, in mid-2000, the government released the Australian Citizenship Council report, which recommended changes to dual citizenship rules (Nolan and Rubenstein Citation2009). This appears to have catalyzed attention in effected communities, and lead to more than 300 letters arriving in a short period in late 2000. However, it did not generate much media coverage, with the issue appearing only 9 times in the media in 2000 – less than the 11 times in 1999. As the proximate cause of the letters appears to be the release of the Australian Citizenship Council report, it demonstrates that the influx of letters is likely to be a product of changing attention. The impacted individuals had not taken political action because they were not paying sufficient attention to the issue. When there was a sudden shift in attention, that prompted their political participation.

In both cases, it appears that the shift in attention came from a government announcement, followed by media coverage and interest group mobilization. Nownes and Freeman (Citation1998) noted that interest groups “urging group members to contact their representatives is not new,” with groups that see themselves as “losing” more likely to undertake such activity (Jones and McBeth Citation2010). In one case, an interest group appealed to its members “[s]o that the Prime Minister knows the depth of feeling on this issue, send him a fax right away” (National Archives of Australia Citation1997). Changes in the external environment, or underlying indictors “by themselves do not have an influence … Rather, the changes in indicators need to be publicized by interest groups” and others (Birkland Citation2017). While this aligns with other theoretical paradigms, such as media agenda-setting (McCombs Citation2002; Russell, Dwidar, and Jones Citation2016; Walgrave and Van Aelst Citation2016), it is also demonstrative of bounded rationality. It shows how people’s attention to politics is disjointed and uneven, driven by disproportionate information flows. Their decisions to pay attention to politics was driven by heuristics – their “indicators” are “locked” onto only one or two trusted sources, the media or preferred interest groups, rather than driven by the underlying environmental indicators.

Discussion

In this study I examined whether punctuated equilibrium theory applies to individuals’ decision to participate in politics. I have shown that there is not a consistent flow of public opinion to leaders. Instead, the public are usually quiet, with occasional periods of shouting – the volume of letters follows a punctuated equilibrium pattern. This finding holds across two countries with significantly different institutional structures (Australia and the USA); across different periods of measurement (weekly, fortnightly and annually); and across different periods of time. Given the normative expectation that policy be responsive to public opinion, it is important to understand how, and under what circumstances, the public express opinions – we need to understand both the content of the opinion, but also the pattern of that incoming opinion. If cognitive friction means that expressed opinion does not adequately reflect underlying public opinion, this creates a hinderance to political responsiveness, and feeds into the under-reaction / over-reaction cycle that has been found in the study of policy change.

While significant research has been devoted to different aspects of the policy process, much less research has been dedicated to whether similar cognitive limitations impact how individuals make policy demands. I have extended punctuated equilibrium theory at the start of the policy process chain, by demonstrating that letters from members of the public to both the Australian Prime Minister and the President of the United States of America demonstrate a punctuated equilibrium pattern. This is the first time that PET has been directly applied to the decision to participate in politics. Existing PET research has, to some extent, “hand-waved” over both the linkages to democratic theory (Botterill and Fenna Citation2019) and public opinion inputs, relying on the central limit theorem to assume their normality (Baumgartner et al. Citation2009). This research has identified one aspect of those inputs which are not normal. While this research supports the hypothesis that bounded rationality, and the “bottle-neck of attention” impacts individuals’ decisions to participate in politics, this does not provide precise answers about what drives these attention shifts in the public, and further research that seeks to link patterns of letters to the issues in the media would be useful to advance this issue. However, the case studies support the idea that it is interest group mobilisation in response to government outputs and announcements that is driving the letters.

With email and social media radically transforming citizen initiated contact (Thomas and Streib Citation2003), it is possible that the punctuated equilibrium dynamics will have changed, given the ease with which you can now contact with your representatives. This study is also limited to letters to chief executives (Presidents and Prime Ministers). I have no visibility of the volume or topic of letters to local representatives, or why individuals may choose to write to one part of government or another. Unlike Yildirim (Citation2022), I have insufficient data to enable a comparison of the level of punctuations between topics, however there appear to be significant differences in the level of punctuations across topics. Finally, the data is limited to those letters that were initially classified by public servants as relevant to a major topic, which reduces our visibility on the total breadth of issues in the letters.

The data may also help research in government oversight and accountability. These same cognitive limitations that drive PET have also been identified as leading to “fire-alarm” approach to oversight by the US Congress (Shaffer Citation2017; McCubbins and Schwartz Citation1984). The “fire-alarm” model of oversight is “crisis-based”, with oversight in each area “languish[ing] for long periods until third-party actors (usually, citizens or interest groups) draw attention to particular problems.” (Shaffer Citation2017, 90). McCubbins and Schwartz (Citation1984) emphasized that this “fire-alarm” model relied on citizens and interest groups drawing attention to problems. The volume of the letters on a particular topic may be one of these theorized fire-alarms.

This also opens further research opportunities in responsiveness research, to understand whether these punctuations in the expression of public opinion correlate with actual policy punctuations. It is not clear from this data in what circumstances the punctuations in public opinion precede policy punctuations, or when the letters are a result of elite agenda setting (Manza and Cook Citation2002).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Daniel Casey

Daniel Casey is a PhD candidate in the School of Politics and International Relations at the Australian National University. He can be reached at [email protected]

Notes

1 A random sample of the topics was coded by three coders to determine inter-coder reliability, based on Krippendorf’s α. A threshold of 80 per cent was established as sufficient (Mikhaylov, Laver, and Benoit Citation2012; O’Connor and Joffe Citation2020), and an alpha of 0.819 was obtained. As this met the threshold, I then completed the coding.

2 Numeric, rather than proportionate differences have been used, because the large number of zeros made calculating proportionate change impossible.

References

- Baumgartner, Frank R, Christian Breunig, Christoffer Green-Pedersen, Bryan D. Jones, Peter B. Mortensen, Michiel Nuytemans, and Stefaan Walgrave. 2009. “Punctuated Equilibrium in Comparative Perspective.” American Journal of Political Science 53: 603–620. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5907.2009.00389.x

- Baumgartner, Frank R, Marcello Carammia, Derek A Epp, Ben Noble, Beatriz Rey, and Tevfik Murat Yildirim. 2017. “Budgetary Change in Authoritarian and Democratic Regimes.” Journal of European Public Policy 24: 792–808. doi:10.1080/13501763.2017.1296482

- Baumgartner, Frank R, and Bryan D Jones. 1991. “Agenda Dynamics and Policy Subsystems.” The Journal of Politics 53: 1044–1074. doi:10.2307/2131866

- Baumgartner, Frank, and B. D. Jones. 1993. Agendas and Instability in American Politics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Berger, Yves G, and İklim Gedik Balay. 2020. “Confidence Intervals of Gini Coefficient Under Unequal Probability Sampling.” Journal of Official Statistics 36: 237–249. doi:10.2478/jos-2020-0013

- Bevan, Shaun. 2019. “Gone Fishing: The Creation of the Comparative Agendas Project Master Codebook.” In Comparative Policy Agendas: Theory, Tools, Data, edited by Frank Baumgartner, Christian Breunig, and Emiliano Grossman, 17–34. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Beyer, Daniela, and Miriam Hänni. 2018. “Two Sides of the Same Coin? Congruence and Responsiveness as Representative Democracy’s Currencies.” Policy Studies Journal 46: S13–S47. doi:10.1111/psj.12251

- Birkland, Thomas A. 2017. “Agenda Setting in Public Policy.” In Handbook of Public Policy Analysis, 89–104. Routledge.

- Botterill, Linda Courtenay, and Alan Fenna. 2019. Interrogating Public Policy Theory: A Political Values Perspective. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Brown, Greg. 2002. “Political Bigamy?: Dual Citizenship in Australia's Migrant Communities.” People and Place 10: 71–77. https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/ielapa.200203768.

- Casey, Daniel. 2022. “‘Dear John … .’: Letters from the Public to Prime Minister Howard.” In Policy Perspectives. Canberra: John Howard Prime Ministerial Library, University of New South Wales.

- Chan, Kwan Nok, and Shuang Zhao. 2016. “Punctuated Equilibrium and the Information Disadvantage of Authoritarianism: Evidence from the People’s Republic of China.” Policy Studies Journal 44: 134–155. doi:10.1111/psj.12138

- Cohen, Bernard Cecil. 1963. Press and Foreign Policy. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Cross, James P, and Derek Greene. 2020. “Talk is not Cheap: Policy Agendas, Information Processing, and the Unusually Proportional Nature of European Central Bank Communications Policy Responses.” Governance 33: 425–444. doi:10.1111/gove.12441

- Cunneen, Chris. 2001. “Assessing the Outcomes of the Royal Commission Into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody.” Health Sociology Review 10: 53–64. doi:10.5172/hesr.2001.10.2.53

- Cunneen, Chris. 2007. “Policing in Indigenous Communities.” In Police Leadership and Management, edited by M. Mitchell and J. Casey, 231–243. Leichhardt: Federation Press.

- Davidson, Russell. 2009. “Reliable Inference for the Gini Index.” Journal of Econometrics 150: 30–40. doi:10.1016/j.jeconom.2008.11.004

- Deltas, George. 2003. “The Small-Sample Bias of the Gini Coefficient: Results and Implications for Empirical Research.” Review of Economics and Statistics 85: 226–234. doi:10.1162/rest.2003.85.1.226

- Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, Australian Government. 1979–2022. “Annual Reports/Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet”.

- Dexter, Lewis Anthony. 1956. “What do Congressmen Hear: The Mail.” The Public Opinion Quarterly 20: 16–27. doi:10.1086/266594

- Dowding, Keith, and Aaron Martin. 2017. Policy Agendas in Australia. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Eissler, Rebecca, Annelise Russell, and Bryan D Jones. 2016. “The Transformation of Ideas: The Origin and Evolution of Punctuated Equilibrium Theory.” In Contemporary Approaches to Public Policy, edited by B. Guy Peters and Philippe Zittoun, 95–112. London: Springer.

- Epp, Derek A. 2015. “Punctuated Equilibria in the Private Sector and the Stability of Market Systems.” Policy Studies Journal 43: 417–436. doi:10.1111/psj.12107

- Fagan, E. J. 2022. “Political Institutions, Punctuated Equilibrium Theory, and Policy Disasters." Policy Studies Journal 1–22. doi:10.1111/psj.12460

- Fernández-i-Marín, Xavier, Steffen Hurka, Christoph Knill, and Yves Steinebach. 2022. “Systemic Dynamics of Policy Change: Overcoming Some Blind Spots of Punctuated Equilibrium Theory.” Policy Studies Journal 50: 527–552. doi:10.1111/psj.12379

- Givel, Michael. 2006. “Punctuated Equilibrium in Limbo: The Tobacco Lobby and US State Policymaking from 1990 to 2003.” Policy Studies Journal 34: 405–418. doi:10.1111/j.1541-0072.2006.00179.x

- Goerres, Achim. 2009. “The Political Participation of Older People in Europe.” In Greying of our Democracy, Vol. 81, 80. doi:10.1057/9780230233959

- Henderson, Geoffrey, Alexander Hertel-Fernandez, Matto Mildenberger, and Leah C Stokes. 2021. “Conducting the Heavenly Chorus: Constituent Contact and Provoked Petitioning in Congress.” Perspectives on Politics, 1–18. doi:10.1017/S1537592721000980

- Holt, Diane, and Ralf Barkemeyer. 2012. “Media Coverage of Sustainable Development Issues–Attention Cycles or Punctuated Equilibrium?” Sustainable Development 20: 1–17. doi:10.1002/sd.460

- Hooghe, Marc, and Sofie Marien. 2012. “How to Reach Members of Parliament? Citizens and Members of Parliament on the Effectiveness of Political Participation Repertoires.” Parliamentary Affairs 67: 536–560. doi:10.1093/pa/gss057

- Jain, Naman, and Palaniappan Ramu. 2022. “L-moments and Chebyshev Inequality Driven Convex Model for Uncertainty Quantification.” Structural and Multidisciplinary Optimization 65: 184. doi:10.1007/s00158-022-03247-4

- Jennings, Will, Stephen Farrall, Emily Gray, and Colin Hay. 2020. “Moral Panics and Punctuated Equilibrium in Public Policy: An Analysis of the Criminal Justice Policy Agenda in Britain.” Policy Studies Journal 48: 207–234. doi:10.1111/psj.12239

- Joly, Jeroen, and Friederike Richter (Eds.). 2019. “Punctuated Equilibrium Theory and Foreign Policy.” In Foreign Policy as Public Policy?, 41–64. Manchester: Manchester University Press. doi:10.7765/9781526140708.00010

- Jones, Bryan D. 1994. Reconceiving Decision-Making in Democratic Politics: Attention, Choice, and Public Policy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Jones, Bryan D. 1999. “Bounded Rationality.” Annual Review of Political Science 2: 297–321. doi:10.1146/annurev.polisci.2.1.297

- Jones, Bryan D. 2001. Politics and the Architecture of Choice: Bounded Rationality and Governance. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Jones, Bryan D. 2003. “Bounded Rationality and Political Science: Lessons from Public Administration and Public Policy.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 13: 395–412. doi:10.1093/jopart/mug028

- Jones, Bryan D. 2017. “Behavioral Rationality as a Foundation for Public Policy Studies.” Cognitive Systems Research 43: 63–75. doi:10.1016/j.cogsys.2017.01.003

- Jones, Bryan D, and Frank R Baumgartner. 2005a. “A Model of Choice for Public Policy.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 15: 325–351. doi:10.1093/jopart/mui018

- Jones, Bryan D, and Frank R Baumgartner. 2005b. The Politics of Attention: How Government Prioritizes Problems. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Jones, Bryan D, and Frank R Baumgartner. 2012. “From There to Here: Punctuated Equilibrium to the General Punctuation Thesis to a Theory of Government Information Processing.” Policy Studies Journal 40: 1–20. doi:10.1111/j.1541-0072.2011.00431.x

- Jones, Michael D, and Mark K McBeth. 2010. “A Narrative Policy Framework: Clear Enough to be Wrong?” Policy Studies Journal 38: 329–353. doi:10.1111/j.1541-0072.2010.00364.x

- Kaplaner, Constantin, and Yves Steinebach. 2022. “Why we Should use the Gini Coefficient to Assess Punctuated Equilibrium Theory.” Political Analysis 30: 450–455. doi:10.1017/pan.2021.25

- Koski, Chris, and Samuel Workman. 2018. “Drawing Practical Lessons from Punctuated Equilibrium Theory.” Policy & Politics 46: 293–308. doi:10.1332/030557318X15230061413778

- Lam, Wai Fung, and Kwan Nok Chan. 2015. “How Authoritarianism Intensifies Punctuated Equilibrium: The Dynamics of Policy Attention in H ong K ong.” Governance 28: 549–570. doi:10.1111/gove.12127

- Lee, Taeku. 2002. Mobilizing Public Opinion: Black Insurgency and Racial Attitudes in the Civil Rights era. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Lindblom, Charles E. 1959. “The Science of Muddling Through.” Public Administration Review 19: 79–88. doi:10.2307/973677

- Lundgren, Magnus, Theresa Squatrito, and Jonas Tallberg. 2018. “Stability and Change in International Policy-Making: A Punctuated Equilibrium Approach.” The Review of International Organizations 13: 547–572. doi:10.1007/s11558-017-9288-x

- Mair, Peter. 1997. “EE Schattschneider's the Semisovereign People.” Political Studies 45: 947–954. doi:10.1111/1467-9248.00122

- Malá, Ivana, Václav Sládek, and D. Bílková. 2021. “Power Comparisons of Normality Tests Based on l-Moments and Classical Tests.” Mathematics and Statistics 9: 994–1003. doi:10.13189/ms.2021.090615

- Manza, Jeff, and Fay Lomax Cook. 2002. “A Democratic Polity?:Three Views of Policy Responsiveness to Public Opinion in the United States.” American Politics Research 30: 630–667. doi:10.1177/153267302237231

- Martin, Aaron, Keith Dowding, Andrew Hindmoor, and Andrew Gibbons. 2014. “The Opinion–Policy Link in Australia.” Australian Journal of Political Science 49: 499–517. doi:10.1080/10361146.2014.934655

- McCombs, Maxwell. 2002. “The Agenda-setting Role of the Mass Media in the Shaping of Public Opinion.” In Mass Media Economics 2002 Conference, London School of Economics. http://sticerd.lse.ac.uk/dps/extra/McCombs.pdf.

- McCubbins, Mathew D, and Thomas Schwartz. 1984. “Congressional Oversight Overlooked: Police Patrols Versus Fire Alarms.” American Journal of Political Science, 165–179. doi:10.2307/2110792

- McFarland, Andrew. 2010. “Interest Group Theory.” In The Oxford Handbook of American Political Parties and Interest Groups, edited by L. Sandy Maisel and Jeffrey M. Berry, 37–56. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Meng, Qingguo, and Ziteng Fan. 2022. “Punctuations and Diversity: Exploring Dynamics of Attention Allocation in China’s E-Government Agenda.” Policy Studies 43: 502–521. doi:10.1080/01442872.2021.1961719

- Mikhaylov, Slava, Michael Laver, and Kenneth R. Benoit. 2012. “Coder Reliability and Misclassification in the Human Coding of Party Manifestos.” Political Analysis 20: 78–91. doi:10.1093/pan/mpr047

- National Archives of Australia (NAA). 1996–2007. “M4326: Ministerial correspondence of John Winston Howard as Prime Minister.”

- National Archives of Australia (NAA). 1997. “Ministerial Correspondence of John Winston Howard as Prime Minister: PM 6 March 1997 [Prime Minister's Daily Program; Letters to Sporting Personalities; Rights of Same Sex Couples; Expenditure Review Committee; Health Insurance Premiums; Aviation; China; Use of Gender Specific Language; Wik] (M4326, 215)."

- Nolan, Mark, and Kim Rubenstein. 2009. “Citizenship and Identity in Diverse Societies.” Humanities Research 15: 29–44. https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/informit.579683126849323.

- Nownes, Anthony J, and Patricia Freeman. 1998. “Interest Group Activity in the States.” The Journal of Politics 60: 86–112. doi:10.2307/2648002

- O’Connor, Cliodhna, and Helene Joffe. 2020. “Intercoder Reliability in Qualitative Research: Debates and Practical Guidelines.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 19: 1609406919899220. doi:10.1177/1609406919899220

- Olofsson, Kristin L. 2022. “Winners and Losers: Conflict Management Through Strategic Policy Engagement.” Review of Policy Research 39: 73–89. doi:10.1111/ropr.12453

- Rottinghaus, Brandon. 2012. “What Predicts Trends in the White House Mail?:The Macro Causes of Mass Political Letter Writing to the Chief Executive.” American Politics Research 40: 205–231. doi:10.1177/1532673X11419244

- Routledge-Prior, Serrin. Forthcoming. “Vegans and ‘Green-Collared Criminals’: The de-Politicization of Animal Advocacy in Public Discourse.” Polity.

- Russell, Annelise, Maraam Dwidar, and Bryan D Jones. 2016. “The Mass Media and the Policy Process.” In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics, 31. Oxford University Press. https://oxfordre.com/politics/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.001.0001/acrefore-9780190228637-e-240.

- Rychert, Marta, and Chris Wilkins. 2018. “Understanding the Development of a Regulated Market Approach to new Psychoactive Substances (NPS) in New Zealand Using Punctuated Equilibrium Theory.” Addiction 113: 2132–2139. doi:10.1111/add.14260

- Schattschneider, Elmer Eric. 1960. The Semisovereign People: A Realist's View of Democracy in America. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

- Schumpeter, Joseph. 1987. Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy. London: Allen & Unwin.

- Shaffer, Robert. 2017. “Cognitive Load and Issue Engagement in Congressional Discourse.” Cognitive Systems Research 44: 89–99. doi:10.1016/j.cogsys.2017.03.006

- Shafi, Saahir, and Daniel J Mallinson. 2022. “Disproportionate Policy Dynamics in Crisis and Uncertainty: An International Comparative Analysis of Policy Responses to COVID-19.” Policy Studies, 1–22. doi:10.1080/01442872.2022.2053093

- Shannon, Brooke N, Zachary A McGee, and Bryan D Jones. 2019. “Bounded Rationality and Cognitive Limits in Political Decision Making.” In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics. https://oxfordre.com/politics/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.001.0001/acrefore-9780190228637-e-961.

- Simon, Herbert Alexander. 1950. Administrative Behavior. New York: Macmillan.

- Smith, Norman B. 1985. “Shall Make No Law Abridging … : An Analysis of the Neglected, but Nearly Absolute, Right of Petition.” University of Cincinnati Law Review 54: 1153.

- Stadelmann, David, and Benno Torgler. 2013. “Bounded Rationality and Voting Decisions Over 160 Years: Voter Behavior and Increasing Complexity in Decision-Making.” PloS one 8: e84078. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0084078

- Sussmann, Leila. 1959. “Mass Political Letter Writing in America: The Growth of an Institution.” The Public Opinion Quarterly 23: 203–212. doi:10.1086/266865

- Sussmann, Leila. 1963. Dear FDR: A Study of Political Letter-Writing. Totowa, NJ: Bedminster Press.

- Thomas, John Clayton, and Gregory Streib. 2003. “The New Face of Government: Citizen-Initiated Contacts in the Era of E-Government.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 13: 83–102. doi:10.1093/jpart/mug010

- True, James L, Bryan D Jones, and Frank R Baumgartner. 2014. “Punctuated-equilibrium Theory: Explaining Stability and Change in Public Policymaking.” In Theories of the Policy Process, edited by P. A. Sabatier and C. M. Weible. Boulder Colorado: Westview Press.

- Verba, Sidney, and Norman H Nie. 1987. Participation in America: Political Democracy and Social Equality. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Viale, Riccardo. 2017. Routledge Handbook of Bounded Rationality. Milton: Taylor & Francis Group.

- Walgrave, Stefaan, and Peter Van Aelst. 2016. Political Agenda Setting and the Mass Media. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Walgrave, Stefaan, and Frédéric Varone. 2008. “Punctuated Equilibrium and Agenda-Setting: Bringing Parties Back in: Policy Change After the Dutroux Crisis in Belgium.” Governance 21: 365–395. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0491.2008.00404.x

- Workman, Samuel, Frank R Baumgartner, and Bryan D Jones. 2022. “The Code and Craft of Punctuated Equilibrium.” In Methods of the Policy Process, edited by Christopher M. Weible and Samuel Workman, 51–79. New York: Routledge.

- Workman, Samuel, Bryan D Jones, and Ashley E Jochim. 2009. “Information Processing and Policy Dynamics.” Policy Studies Journal 37: 75–92. doi:10.1111/j.1541-0072.2008.00296.x

- Yildirim, Tevfik Murat. 2022. ‘Stability and Change in the Public’s Policy Agenda: A Punctuated Equilibrium approach’, Policy Sciences, 55: 337-350. doi:10.1007/s11077-022-09458-2