ABSTRACT

Explaining policy change has been one of the major concerns of educational policy studies. Guided by the multiple streams framework (MSF), this article aims to explain the specific dynamics of cost-elimination policies at the high school level in Ghana. Through the thematic analysis of interviews, documents, and other resources, we argue that an exceptional confluence of problems, policies, and politics has shaped the Ghanaian educational policy process and generated policy change. Our findings demonstrate the pivotal role of partisan electoral politics, helping explain why political parties, governments, and policymakers shifted towards the adoption of fee-free educational policies. Although the problem stream contributed to the opening of the policy window during agenda-setting and the problem and the policy streams played a non-negligible role in policy adoption, the political stream dominated both stages. Accordingly, the study argues that the electoral interests of political actors were the main driver of the adoption of fee-free educational policies in Ghana.

Introduction

Following the widespread adoption of cost-elimination policies – popularly called “fee-free educational policies” – at the primary and lower secondary school levels in many low-income countries and the subsequent surge in school enrolment, policy actors’ attention has shifted to upper secondary education (Asante Citation2024a; Little and Lewin Citation2011, 477).Footnote1 Financing for delivering upper secondary education services in many Sub-Saharan African (SSA) countries, the region with the lowest enrolment rate in the world, has undergone change. Some countries – for example, Ghana, Kenya, Malawi, Namibia, Sierra Leone, South Africa, and Uganda – have adopted fee-free educational policies. Ghana, a young democracy in SSA, stands out concerning the dynamics of these policies. Within the socio-political environment of the fragile Ghanaian democracy, fee-free educational policies change from one government to the next, with different scopes and coverage (Abdul-Rahaman et al. Citation2018). The 1992 Constitution of Ghana already highlighted the possibility of introducing policies that provide fee-free education to all qualified Ghanaians at the high school level. The following is stated in Article 25 (1b):

(b) Secondary education in its different forms, including technical and vocational education, shall be made generally available and accessible to all by every appropriate means, and in particular, by the progressive introduction of free education (Ghana Citation1993).

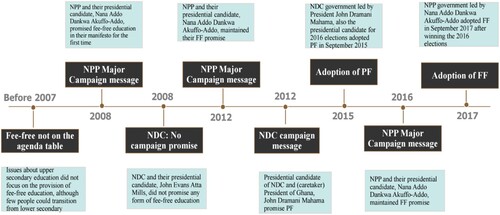

A significant step in the process was when in 2015 the National Democratic Congress (NDC) government adopted Progressive Free Senior High School Policy (PF). This was a form of partial funding aimed at reducing the cost of senior high school education for some schools and students, especially day (or non-residential) students (n.b. school students in Ghana have never paid full tuition fees). Specifically, students were exempted from paying the following education-related fees: for examinations, entertainment, library, student representative council (SRC) dues, sports, cultural activities, science development, science and mathematics quizzes, information and communication technology (ICT), and co-curricular fees for day students in public senior high schools (Ministry of Finance Citation2015). Before the introduction of PF, students were paying the aforementioned cost items in addition to other related fees. Just two years after the adoption of this policy, Free Senior High School Policy (FF) replaced PF (in September 2017). This happened during the incumbency of a new government formed by the New Patriotic Party (NPP), which was elected to office in January 2017. This fee-free educational policy absorbs all of the direct costs of schooling and other indirect costs, such as food and boarding fees, and applies to upper secondary schools across the country, creating holistic fee-free education (Abdul-Rahaman et al. Citation2018).

Notwithstanding the success of these policies, especially FF, at increasing school access (enrolment) at the senior high level (Asante, Nkansah, and Agbee Citation2024; Mohammed and Kuyini Citation2021), their adoption has encountered varied implementation challenges, as identified by practitioners and academics. These include the unsustainable and untimely release of funds by governments (Akakpo Citation2021; Ansah Citation2019; Yanney Citation2018, 1), the limited volume of textbooks, and inadequate infrastructure for accommodating students (Adarkwah Citation2022; Opoku Prempeh Citation2019), centralized administrative systems (Asante, Nkansah, and Agbee Citation2024) and the focus on the political rather than the policy process (Adarkwah Citation2022; Mohammed and Kuyini Citation2021). These phenomena present us with exciting puzzles, suggesting that the low rate of school participation was not the primary driver of the adoption of these policies. We thus address the following research questions: What factors can explain these changes in the educational policy of Ghana over the past eight years, and what mechanisms drove this process?

Previously, scholars investigating educational policy change have analyzed the dynamics of change from various perspectives, inspired by the idea of policy cycles (Adarkwah Citation2022; Howlett and Giest Citation2013) and policy process frameworks (Mohammed Citation2020; Mohammed and Kuyini Citation2021). The studies about fee-free educational policies in Ghana have either focused on only single fee-free educational policies or failed to open the “black box” of underlying mechanisms that led to changes. The research of Adarkwah (Citation2022), Mohammed (Citation2020), and Mohammed and Kuyini (Citation2021) examined fee-free educational policies in Ghana, combining several theoretical approaches but without investigating why policymakers would put adopting fee-free educational policy on the agenda. Asante (Citation2023) drew on multiple theoretical approaches when comparing several countries to examine the conditions for adopting fee-free educational policies across SSA, but without studying the drivers of the policy change. Accordingly, the potential value-added of our research – an intensive within-case analysis – is identifying the mechanisms of policy change towards fee-free education and understanding why governments adopted and implemented the idea.

In this study, we use the multiple streams framework (MSF) (Herweg, Zahariadis, and Zohlnhöfer Citation2023; Kingdon Citation2014) to uncover the factors and the mechanism(s) driving fee-free educational policies in Ghana. Our data are collected from elite interviews (comprising stakeholders and persons involved in educational policymaking) and the major policy documents related to the Ghanaian adoption of Progressive Free Senior High School and Free Senior High School policies. We seek to understand why fee-free education was assigned such importance on the two major political parties’ policy agendas. Put differently, we aim to understand why influential policy actors focused on fee-free educational policy agendas and were determined to adopt them, given that a number of other serious policy problems remain unaddressed.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 discusses the multiple streams framework, which analytical approach inspired the research into potential causes of fee-free educational policy change. Section 3 provides details about our case and methodology. Empirical findings are presented in Section 4, and Section 5 is devoted to a discussion, conclusions, and defining avenues for further research.

Theoretical framework

In this paper, we rely on the multiple streams framework to interpret the policy shift towards fee-free education in Ghana. Several studies that have investigated educational policy changes have used the multiple streams framework, either generally (Béland Citation2005) or specifically for Ghana (Boasiako and Asare Citation2015). Mohammed's (Citation2020) study about fee-free education used rival theoretical approaches, finding that MSF may be a particularly appropriate approach compared to other frameworks. Similarly, we utilize MSF as our analytical framework, taking into account recent refinements of the theory (Herweg, Zahariadis, and Zohlnhöfer Citation2023).

The three streams of the multiple streams framework

In explaining the process of policy change, MSF (Kingdon Citation2014) distinguishes three streams: the problem, the policy, and the political streams. Much of the problem stream is defined by how pivotal actors frame issues, referring to the contested nature of problems. The problem may be defined as the prevailing social conditions that are seen as public ones but require government action for their solution. “Problems” are generally social constructs in the sense that they involve elements of perception and interpretation since people’s ideals and conceived reality vary significantly. For example, a given rate of school enrolment may be considered “low” and “a problem” by some people but not others. Notwithstanding, any form of indicator or condition, such as a “low” enrolment rate, may be seen as a problem only when actors (as problem brokers) define it as a problem and build a narrative into the larger policy discourse that encourages policymakers to accept it. However, the building of these narratives may occur in many ways if this supports actors’ political survival or threatens specific interests (DeLeo Citation2018; DeLeo and Duarte Citation2022). In simple terms, “the more politically relevant a condition becomes, the more likely it is that it will be dealt with” (Herweg, Zahariadis, and Zohlnhöfer Citation2023, 33).

The policy stream concerns the ideas floating around in the “policy primeval soup” (Kingdon Citation2014, 117). It is populated by knowledge/perspectives associated with policy problems. The policy stream is generally dominated by policy communities comprised mainly of civil servants, interest groups, academics, researchers, and consultants who argue and work as policy experts to provide policy solutions/alternatives. However, these policy experts do not operate in a vacuum, as external influences or representatives of interest groups influence the kind of policy alternatives or ideas that may be adopted to solve a particular problem. For example, international organizations such as the World Bank and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) may influence a policy aimed at increasing school participation due to the global vision of Education for All (Tikly Citation2016). Although several policy solutions/alternatives may be proposed, a policy stream may viably be coupled with other streams if at least one viable policy solution exists that meets the criteria for survival. The latter may be defined in relation to the feasibility, acceptability, public acquiescence, financial feasibility, or the conformity of the policy alternative to the law (Herweg, Zahariadis, and Zohlnhöfer Citation2023).

Finally, the political stream is determined by the prevailing national mood, interest groups, and the government. When

a fairly large number of individuals in a given country tend to think along common lines and […] the mood swings from time to time, government officials sense changes in this mood and act to promote certain items on the agenda according to the national mood. (Herweg, Zahariadis, and Zohlnhöfer Citation2023, 35)

Policy window and coupling

Although the original MSF was developed to explain agenda-setting (or the agenda window) solely, other scholars have extended its application to policy formulation and adoption (decision-making or the decision window) and even policy implementation (Herweg, Zahariadis, and Zohlnhöfer Citation2023; Zohlnhöfer, Herweg, and Rüb Citation2015). However, in this study, we aim to investigate the originally addressed agenda-setting stage, with some reference to later stages, especially to the policy formulation/adoption stage, for various reasons. First, this was the original scope of MSF, and the theory is still the most elaborate in this field. Second, in the policy case discussed below, the policies were practically decided during the agenda-setting stage.

A policy change may happen when the three streams couple. The ripeness of the three independent streams is a necessary but not sufficient condition for a policy change. The couplings of the three streams occur at specific points in time: these are the policy windows. A policy window represents a fleeting opportunity “for advocates of proposals [policy entrepreneurs] to push their pet solutions or to push attention to their special problems” (Kingdon Citation2014, 203). Policy windows may open during predictable events, most typically election periods, or arise due to unpredictable events, like terrorist attacks.

At the agenda-setting stage, a policy window may open either in the problem stream or in the political stream. A problem may arise on the agenda and be coupled with a pre-existing policy solution that fits the former. At other times, a political opportunity may arise – such as with the advent of a new government or electoral campaign.

Although the other two streams are relevant at the policy adoption stage, the political stream is crucial, as the main task is to form a political majority that supports the preferred policy alternative. As opposed to agenda-setting, institutions – an element mostly neglected in the original theory – play a key role as they frame potential change (Zohlnhöfer, Herweg, and Rüb Citation2015).

Empirical analysis

Case selection and justification

Ghana was selected as the location for the case study – a young democracy in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) that provides fee-free education to students at the high school level. As Ghana has been performing better than other SSA countries according to the relevant governance and policy indicators (see ), it cannot be considered a typical case from SSA. However, from a diagnostic case study perspective, studying Ghana is of broader relevance as it is an influential case (Gerring and Cojocaru Citation2016, 403–404). Investigating the shift towards fee-free educational policy in the Ghanaian context provides meaningful insights into potential educational policy changes in other SSA countries with weaker democratic institutions and effectiveness of governance, lower upper secondary school enrolment, and higher poverty rates.

Table 1. Case selection rationale.

Studying the adoption of PF (identified as partial fee-free educational policy) and FF (identified as holistic fee-free educational policy) (see Asante Citation2024b) allows us to undertake intensive within-case policy analysis of a policy process associated with two major policy changes. In addition, since the two policy changes were adopted by two different political parties that formed governments with different political leaderships, we can also assess the role of ideational motivations (Béland Citation2009) behind the policy change.

Data collection and analysis

The empirical analysis is based on documents and interviews. The first step in the research was to review the development of fee-free education in Ghana. For this, we examined published academic, opinion, and news articles, policy documents related to fee-free education, and websites of key international development partners and professional networks. During this search, we determined key informants to speak to regarding the development of the two recent policies. From November 17 to December 15, 2021, the first author conducted eighteen personal (face-to-face) elite interviewsFootnote2 (see in the Appendix for details) in English. The semi-structured interviews – with a duration ranging from 35 to 50 min – centred on participants’ perceptions and experiences of the development of the two policies, with questions guided by the assumptions of MSF reviewed in the theoretical section.

To improve the validity and reliability of our data, we first tested the interview instrument by conducting a pilot interview. Inclusion criteria for the interview participants and information from secondary sources were defined. The selection of interview respondents was based on institutional affiliation. Initially, institutions were contacted, and the study was introduced to them. Assuming they agreed to assist with an interview, they nominated a high-profile person or people within the institution who was(were) willing and had enough knowledge and personal experience about the two policies to participate. This strategy reduced the impact of personal preferences for interviewing specific individuals. Before any interview took place, informed consent was sought from participants. Documents and media sources published in English that were identified as being from reliable sources were included in the study.

The data were analyzed through thematic analysis, a form of qualitative inquiry (Patton Citation2015) by grouping the key ideas identified during the preceding empirical stages into themes suggested by the three streams defined in MSF. In this process, we closely reviewed the relevant documents, read the interview transcripts, and transcribed all the information we had gathered. The goal was to identify the major factors that have facilitated the changes (for example, personalities/actors, organizations, institutions, and events) and classify them under an overarching theme. We have substituted all respondents’ names with institutional affiliations to preserve privacy. In addition, given that some participants have political appointments and needed to be sure their comments would not adversely affect their careers, an extra layer of anonymity was implemented by synthesizing the results to create a combined story of narratives with a few direct quotations, where appropriate.

Results

The analysis covers two governments’ fee-free educational policy changes, which followed a long period of inaction. Although the 1992 Constitution makes provisions for providing free secondary education, no timeline for adopting such a policy was explicitly stated (Respondents #11 and #14, 2021). However, some twenty years later, Progressive Free Senior High School policy (PF) was initiated by President John Dramani Mahama. Just two years later, in 2017, Free Senior High School policy (FF) was adopted as President Nana Addo Dankwa Akufo-Addo came to power. Below, we discuss the development of the three streams as identified by MSF to uncover the main mechanism(s) shaping these policy changes.

The problem stream: an identified problem with the marginal impact of international and civil society actors as problem brokers

In the literature, many reasons are proposed to explain the inability of people to enrol in high school, including poverty, child work, income shocks, inequality, and health (Akyeampong et al. Citation2007). However, throughout the interview and document analysis, poverty recurrently emerged as the major reason for low enrolment, that is, the weak transition from lower secondary to upper secondary school (Respondents #01, #02, #03, #04, #12, #13, #15, #16, and #18; 2021). An assessment elaborated by the Ghanaian Ministry of Education after the adoption of FF policy in 2017 showed that about 100,000 qualified students who complete basic school could not enrol in high school every year primarily for this reason (Opoku Prempeh Citation2019; Respondents #04, #10, #12, #13, #14, #15 and #18; 2021). It seems that – as previously anticipated by the drafters of the 1992 Constitution of Ghana – the recent empirical data and the general public conceived the problem of the low enrolment rate at the high school level similarly.

The need for government action to mitigate the problem was raised by various actors. Civil society organizations (CSOs), though relatively scarce in number and weak in terms of political influence, attempted to place the problem on the agenda. However, CSO representatives who had advocated the need to improve the level of educational participation through press conferences and symposiums perceived that their activity hardly played a significant role, in contrast to that of party politics (Respondents #10, #11, #12, and #13; 2021). In addition, despite our intensive research and interviews with several highly informed persons (see Appendix), we could not find evidence of parents’ or teachers’ associations, the most directly interested parties, attempting to put the issue on the government’s agenda either before 2015 or between 2015 and 2017.

Regarding international actors, in 2015, the global focus on primary education for all of the Millennium Development Goals shifted to secondary education for all, which is in line with the Sustainable Development Goals, including upper secondary education (United Nations Citation2020). However, this document had no traceable impact on agenda-setting in Ghana. International organizations (IOs), notably the World Bank and UNESCO, emphasized the need to increase school participation at the upper secondary level across SSA as part of the Sustainable Development Goals (Respondents #14, #15; 2021). Although their impact on the public debate was not identified in any of the interviews, we found evidence that policymakers were aware of the fact that these organizations had highlighted the problem of the weak transition from lower secondary to upper secondary school.

In brief, the 1992 Constitution of Ghana (and the previous constitution) underscored the problem of low enrolment and suggested the adoption of free education. International and civil society organizations have also highlighted the problem in recent years, emphasizing that the number of people who cannot enrol in high school due to poverty keeps increasing. However, these constitutional provisions, activities of IOs and CSOs, and deteriorating enrolment indicators were not enough to generate a meaningful public debate and put the issue on the agenda.

Policy stream: uncrystallized policy communities, a lack of screening for viable policy alternatives

The constitutional requirement for some kind of government action can be traced back to the 1979 Third Republican Constitution of Ghana, which stated in Article 6 (3a) that: “The Government shall, subject to the availability of resources, provide (a) free and equal access to secondary and other appropriate pre-university education” (Ghana Citation1979, 11). As noted above, since the enactment of the 1992 Constitution, the need for government action emerged only in 2008: one of the presidential candidates raised the issue, which soon appeared on the two leading parties’ manifestos.

Once relative agreement is formed regarding the necessity of government action, the specific policies may be determined. Such policies are then supposed to be formulated in the policy stream. In our case, the policy challenge involved addressing the following question: What type of policy instruments should the government apply to support pupils to continue their upper secondary-level studies (with a focus on pupils who are deterred from continuing their studies mainly by poverty)?

Civil society organizations suggested specific policy measures. However, as the representative of one CSO who advocated for FF mentioned, the government did not consult with civil society actors in a meaningful way:

[The policy] was just announced by the president […] Later, the minister for education invited us to a meeting to address some of the gaps. The decision to adopt the policy was already decided, and the minister did not incorporate our views […] There was not much consultation. (Respondent #10, 2021)

We had a lot of meetings to share our ideas. The president appreciated the points we made [in one of our meetings] but did not intend to include them in the planning of the policy. Their minds were made up to adopt the policy as they had planned. (Respondent #11, 2021)

International organizations were invited to “contribute” only once a final decision had been taken, clearly indicating their negligible role in the policy stream. Although these organizations could have drawn on the experience of other countries with similar policies, this experience was not requested (Respondents #12, #13, #14, and #15, 2021).

Undoubtedly, the key issue was the (financial) feasibility of the FF policy. The more actively the government assists students to continue their studies at the upper secondary level, the more public resources are needed. This issue was raised by various parties with no traceable impact. The critique was formulated most noticeably by the NDC party following 2008 in relation to its financial and infrastructural infeasibility (Respondents #10 and #15, 2021).

Indeed, the more successful such a policy is, the greater the pressure on the education system to meet the dramatically increased need within a short period. As data show, the number of students enrolled in upper secondary education increased from around three hundred thousand to well above four hundred thousand between 2015 and 2018, resulting in a situation, as reviewed in a 2018 report, where 472,730 seats were needed but only 277,537 were available (Opoku Prempeh Citation2019). The government adopted a modified school calendar (double-track system) in the middle of the policy implementation process to allow some students to be in school and others on holiday to create space. These challenges of implementation have been widely addressed in the policy literature (Adarkwah Citation2022; Akakpo Citation2021; Ansah Citation2019; Asante, Nkansah, and Agbee Citation2024; Mohammed and Kuyini Citation2021; Yanney Citation2018, 1).

However, our interviewees confirmed that no feasibility analysis of FF educational policy had been prepared by the administration by 2018. Several interviewees explicitly stated that the final decision to introduce PF and FF policies was made without identifying well-defined sources of funding, as evidenced by the challenges encountered in the implementation of the PF and FF (Respondents #05, #06, #07, #08, #09, #10, and #11; 2021). A member of the Education Select Committee in Parliament qualified the decision to adopt FF: “It was purely the idea of the president, and so he showed leadership during the decision to adopt the policy” (Respondent #04, 2021).

For President Mahama, a more modest policy of PF adopted in the pre-election period seemed to be a compromise between the significant pressure for a policy supporting high school attendance for less affluent youth and financial and infrastructural constraints. President Akufo-Addo had emphasized the need for a holistic fee-free policy since 2008. He held meetings with some stakeholders who were highly critical of the way the FF policy would be funded. At the meetings, however, the President did not accept the idea of alternative policy proposals and expressed his firm intention to introduce the policy regardless of the challenges of implementation (Respondent #11, 2021). Several interviewees stated that they were invited to join the supporting coalition for either PF or FF policies only when the respective decisions had already been made (Respondents #12, #13, #14, and #15; 2021).

We may reasonably claim that the policy choices seem to have been made by the elected presidents themselves. The policy stream as conceived by MSF is hard to identify; one can hardly speak of a policy community consisting of policy experts, consultants, or academic researchers. Nor could we find any evidence of a presumed “softening-up,” i.e. screening of various policy alternatives for their viability. As several interviewees expressed, outside of the government, there was no specific policy coalition that advocated the implementation of the FF policy (Respondents #08, #09, #10, and #15, 2021).

Political stream: dominance at the agenda-setting as well as the policy-formulation stages

The political stream developed around the two major parties and their presidential candidates, later elected presidents. Traditionally, the National Democratic Congress (NDC) has a more socialist orientation, while the New Patriotic Party (NPP) is more conservative. However, the issue was first raised by Akuffo-Addo, the NPP’s presidential candidate in 2008. He strongly believed in the significance of the problem and the necessity of government action to handle it (Respondents #02, #04, #10, #11, #17, and #18; 2021). In all his campaign platforms, the promise of fee-free education was his main message to the electorate, and he tagged this a “Sacred Promise to Ghanaians” (Quaicoe Citation2012, para. 4). One respondent stated about FF that: “It started as a manifesto promise by the current government … The NPP party promised that if they c[a]me to power instead of absorbing part of the fees, they w[ould] absorb all the fees” (Respondent #13, 2021). Akuffo-Addo’s consistent advocacy of fee-free education made it a major public policy issue. It proved to be a crucial issue in the 2012 and 2016 presidential elections (and even more recently in the 2020 elections).

An important assumption of MSF is that policy positions of governments and political actors are influenced by the national mood (Herweg, Zahariadis, and Zohlnhöfer Citation2023, 36). This is reflected in President Mahama’s changing policy stance: he sensed the shift in the public mood and, despite his and his party’s originally cautious or even hostile stance, announced a change in education policy involving partially funding the costs of senior high school students. The more modest PF policy supported mainly non-residential (day) students in specific areas but did not fully fund education costs. This seemed to be a compromise between the need for political action and feasibility constraints. The NDC government introduced the PF a year before the 2016 general election: this was to demonstrate its commitment to free education (Respondents #08, #09, #10, #11, and #17; 2021). The interviewee referred to the popularity and the perceived electoral gains of fee-free education among the youth as well as parents and guardians; this was an important mechanism in the coupling when the NDC government adopted the PF (Respondents #05, #07, #08, #09, #10, and #11; 2021). One interviewee commented:

Every politician is interested in these policies. It is an election winner. When they were in government, the NDC was forced to come up with their version of free education called PF because the opposition [party] was making noise about it. They had to do something about it at the time because it was of high political interest. (Respondent #11, 2021)

The interest of political actors in these policies is very high. This is demonstrated in their aggressive discussions about these policies in the media space. (…) Because we do not have a well-defined development plan, we are a country that relies on political leadership for everything we do. Political leadership was very influential in these free education policies. (Respondent #13, 2021)

A reflection on the macroeconomic context confirms the specific importance of the political stream in shifting Ghana's educational policy towards fee-free education. The period 2011–2014 was one of high growth for Ghana: in 2011, Ghana recorded exceptional real GDP growth (14%) thanks to the discovery and production of oil (Fosu Citation2017). The following years also saw strong economic growth: 9.3% in 2012 and 7.3% in 2013 (according to World Bank statistics on real GDP growth). Despite the favourable macroeconomic context, the fee-free educational policy was not adopted during these years, and a large number of students could not move from lower secondary to upper secondary education due to the cost of financing. A plausible explanation is that the ruling political party and the incumbent political leaders had not promised any form of fee-free educational policy. However, in 2015, despite slow economic growth (2.1%), the government adopted PF to fulfil previous campaign promises before the next elections (Respondents #04, #07, #08, #09, #10, #11, and #15; 2021).

When President Mahama indicated in 2014 that he would introduce free education, the opposition candidate and future President, Akufo-Addo, could not resist the temptation to comment in a Twitter post: “If President Mahama is, indeed, introducing free SHS in the 2015–2016 academic year, I would say alleluia [sic!]” (Nana Akufo-Addo Citation2014). Later, during the launch of the FF, the (new) President hinted at how his strong belief in this policy had led to its adoption. He stated:

Today is a very happy day for the good people of Ghana, for the government, and for me personally [emphasis added]. I am here, this morning, to perform a very pleasant task: to launch the commencement of the Free Senior High School policy. When I proposed this policy in 2008, many were those who said Free SHS could not be done … The culmination of that belief, inter alia, resulted in the decisive victory won by the New Patriotic Party and my modest self in the elections of 2016 [emphasis added]. (Nana Akufo-Addo Citation2017, paras 1–3)

No, in the sense that the readiness and the resources to implement these policies were not readily available. No adequate preparation was made. The reliance on the double track system [during the implementation of the policy] was a typical demonstration of […] unpreparedness for the policy of FF. (Respondent #13, 2021)

It [FF] was a political promise. Once the party won power, as a technocrat at the Ministry of Education, we had to put up [create] the system to get the policy running when the government decided to adopt it [emphasis added]. (Respondent #12, 2021)

Policy window and coupling: the dominant role of the political stream and electoral campaigns

Although the idea of fee-free education was incorporated in the 1992 Constitution of Ghana, a window for policy change only opened 16 years later. The presidential candidate of NPP, Mr Akufo-Addo, was the first to float the idea of fee-free education in the public domain during his 2008 election campaign. Subsequently, the narrative of fee-free education spread through all forms of media space, attracting public attention and shifting the public mood to strong support for the adoption of fee-free educational policy. This also prompted the rival political party to respond, and the policy eventually appeared in NDC’s 2012 electoral manifesto. One interviewee noted: “Although some groups were discussing the idea of free education at the high school level, the issue came to public attention when a political party eventually introduced it into its manifesto” (Respondent #10, 2021).

Two components of the potential coupling, namely, the recognition of the low transition rate from lower secondary to upper secondary school as a problem and the assumed policy solution in the form of fee-free education, have thus existed for a long time. However, it was not until 2015 and 2017 that fee-free policies were adopted in Ghana. The two Presidents of Ghana played a crucial role in the coupling process and acted as political entrepreneurs: John Dramani Mahama in the adoption of Progressive Free Senior High School policy and Nana Addo Dankwa Akuffo-Addo in the adoption of Free Senior High School policy. The formation of political majorities and the parliamentary approval of increased public spending went smoothly in both cases. Accordingly, the political stream, and in particular, the role of electoral campaigns, was dominant in opening the policy window for fee-free educational policies in Ghana concerning both the agenda-setting and the decision-making stages.

Discussion and conclusions

In this study, we have aimed to identify and explain the factors and mechanisms facilitating the adoption of fee-free educational policies using two recently adopted policies in Ghana. We used the multiple streams framework (MSF) (Herweg, Zahariadis, and Zohlnhöfer Citation2023; Kingdon Citation2014) as our analytical framework. The basic assumptions of the framework suggest that policy change can take place when the coupling of the three independent streams (problem, policy, and political streams) occurs. We briefly reviewed the three streams in our case and found that:

Although some policy actors, who may be identified as potential problem brokers, existed in the problem stream, their impact on putting the problem on the public agenda was marginal. The problem had been recognized for a long time; the Constitution had addressed it since 1992, and it was on the agendas of international organizations, but it did not appear on the public agenda in Ghana until one of the major political parties included it in its election manifesto. Soon, both major parties took up the issue, and it became a major topic of public discussion. In other words, public discussion was driven by political action, not the other way around, and politicians were the problem brokers.

Although the implementation of an ambitious policy such as FF poses challenges, there was no evidence of an intensive discussion of the policy options advocated by different actors. Consideration of policy survival criteria, such as technical feasibility and financial viability, was neglected. The government apparatus failed to provide even rough cost–benefit estimations, let alone an ex-ante assessment of feasibility. The first such document became available in 2018, three years after the first policy and one year after the second policy was adopted. The specific policy solutions were undeniably made on a political basis.

The original MSF theory suggests three main factors that can influence the dynamics of policymaking: the national mood, the potential reactions of interest groups, and the political majority. (i) As we have indicated above, political actors have tended to shape the national mood rather than adapt to it. (ii) Interest groups may generally play a much smaller role in less developed, fragile democracies such as SSA countries (Mohammed Citation2019; Onyango Citation2022, 272), and we found this in the case of the fee-free educational policies in Ghana. (iii) Nevertheless, building political support for policy change appears to be crucial. However, the formation of a political majority is somewhat specific to a presidential system like Ghana's. This is attributed to the dominance of the executive, led by the president, in Ghana's policymaking tradition (Kpessa Citation2011; Mohammed Citation2019). In these presidential systems, there is a non-collegial executive through which presidents usually shape policies through their campaign promises and statements (Vijeyarasa Citation2022). In this context, scholars have argued that political actors are a dominant factor in the adoption of social policies in general (Downs Citation1957; Maclure Citation1990; Zohlnhöfer Citation2009), and particularly in the case of fee-free education in SSA (Adarkwah Citation2022; Frempong Citation2020; Mohammed and Kuyini Citation2021). In applying MSF, we found that decision-making was smooth, mainly due to the committed involvement of top political actors in the adoption of fee-free education policies.

Earlier empirical studies about educational politics, not based on MSF theory, reached a similar conclusion. There is a strong presidential agenda-setting approach to free education policy due to its popularity and perceived electoral benefits (Adarkwah Citation2022; Asante Citation2023; Correa et al. Citation2020; Mohammed and Kuyini Citation2021). The dominant role naturally stems from the constitutional-political arrangement that provides a dominant position to the president. At the same time, civil society organizations appear to be weak in both the problem and policy streams. Surprisingly, at least in this policy field, we could not detect any relevant influence of international organizations either. Due to the marginal role of potential civil society and international actors, both streams have had limited influence on agenda-setting and decision-making.

According to the logic of MSF (Herweg, Zahariadis, and Zohlnhöfer Citation2023), even within the political stream, interest groups and policymakers may oppose certain policy proposals. However, in our case, these balancing forces did not seem to exist, and party politics has been the dominant factor in policy changes (Herweg, Huß, and Zohlnhöfer Citation2015). It is not surprising that other scholars (Adarkwah Citation2022; Mohammed and Kuyini Citation2021) have described the adoption of FF in particular as a solution looking for a problem that suits it to solve which highlights the logic of MSF when agenda setting originates from the political stream (Herweg, Zahariadis, and Zohlnhöfer Citation2023, 37–38) and when political actors dominate both the agenda-setting and the decision-making stages.

The idea of fee-free policies (FP and FF) was raised during presidential election campaigns, which we have interpreted above as the “agenda-setting stage” and focused our analysis on. However, we also indicated that in both cases, the policy was adopted once the president was elected or when the next election was approaching, which could be interpreted as policy formulation according to extended MSF theory. We also pointed out the challenges during the implementation stage. In other words, the findings can be interpreted as the three streams becoming coupled, resulting in two different policies when the policy window opened around the presidential elections.

Conclusion

Policy process scholars are encouraged to improve the theories in the field. As many of these theories are currently applicable to or were developed in advanced economies and mature democracies, scholars may be motivated to apply them to other contexts to examine their usefulness and, where appropriate, to suggest improvements or contextual modifications. In this study, we used MSF (Herweg, Zahariadis, and Zohlnhöfer Citation2023; Kingdon Citation2014) to explain the adoption of fee-free educational policies in Ghana in the context of a young democracy.

The assumption of MSF is that the three streams play roughly equal roles, each with varied actors, and only their accidental coupling results in policy change. However, the role of the three streams was strikingly different in our case. Although a problem was identified in the problem stream, we found that the same few political actors dominated all three streams: they highlighted and framed the problem, and their role, once in power, was decisive for both agenda-setting and policy adoption. In the context of fee-free educational policies in Ghana, elections created the policy window.

We found that MSF can be applied in this specific policy context with limitations. In , we attempt to assess the applicability of the main elements of MSF to the case at hand. For this, we rely on the components addressed by Herweg, Zahariadis, and Zohlnhöfer (Citation2023, 40) in Table 1.1.

Table 2. Fee-free educational policy in Ghana. Main findings through the lens of the Multiple Streams Framework (MSF).

Limitations and directions for further research

This study has focused on the socio-political dimensions of fee-free educational policies and drawn conclusions from the experiences and perspectives of a range of stakeholders. Others from different fields of study, such as economics, may disagree, interpreting this framework differently. Notwithstanding these limitations, the study provides insights into an influential case that helps explain and understand the factors and mechanisms that facilitated the adoption of fee-free educational policies in Ghana.

Furthermore, the implication for young democracies of the strong involvement of electoral politics in the adoption of fee-free educational policies is that the former will also strongly affect the future of such policies. This issue is particularly relevant because the current framework of fee-free educational policies lacks strict laws that oblige (subsequent) governments to continue with their implementation. What happens when an incumbent political party and/or leader has no belief in or ideological preference for continuing such a policy? What if (the head of) the executive has an interest in adopting such a policy, but parliament is unwilling to approve the related budget expenditure when the executive does not have a clear majority (in the case of a presidential system)? These scenarios need to be studied in younger democracies – namely, the future of fee-free educational policies vis-à-vis changes in political structures.

Finally, the study used a single country case study and examined one policy field: education. Further studies can use our conclusions to investigate different policy fields or cases and validate or refute these findings about the application of MSF in the context of young/fragile democracies.

Informed consent statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Acknowledgement

A previous version of the manuscript was presented at the Conference on Policy Process Research (COPPR) 2023, Denver, Colorado and the 6th International Conference on Public Policy, Toronto. We thank the discussants and the panel participants for their useful comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Gabriel Asante

Gabriel Asante holds PhD in Political Science from Corvinus University of Budapest, Hungary and an MPhil and BA in Political Science from KNUST-Kumasi. He is currently researching into the social benefits and the conditions for the adoption of cost-elimination policies (fee-free educational policies) in Sub-Saharan Africa. His goal is to utilize Western theoretical frameworks to understand the African context and suggest theoretical refinements where necessary. His research interests include the evolution of education policies in developing economies, crime among youth, comparative public policy and public administration.

György Gajduschek

György Gajduschek is a senior researcher at the HUN-REN Center for Social Sciences and a full professor at Corvinus University in Budapest. He holds a BA in Public Administration and an MA in Sociology from Hungarian institutions, as well as an MA in Public Administration from Rockefeller College (NY, USA). Additionally, he has earned PhDs in both Political Science and Legal Studies. His primary research interests include bureaucratic functioning and policy making in non-Western countries.

Attila Bartha

Attila Bartha Associate Professor and Programme Director of the MSc in Public Policy and Management, Corvinus University of Budapest & Senior Research Fellow, HUN-REN Centre for Social Sciences. His main research interests are governance, public policy and welfare reforms, comparative economic and social policy analysis.

Notes

1 Upper secondary education is often referred to as “senior secondary school,” “senior high school,” or “high school.” We use these terms interchangeably throughout the study. They all refer to Level 3 of the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED 3).

2 Except for the interviews with the World Bank and United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) representatives. These two interviews were conducted via phone and Microsoft Teams due to organizational restrictions associated with COVID-19 and time schedules.

References

- Abdul-Rahaman, N., A. Basit Abdul Rahaman, W. Ming, A.-R. Ahmed, and A.-R. S. Salma. 2018. “The Free Senior High Policy: An Appropriate Replacement to the Progressive Free Senior High Policy.” International Journal of Education and Literacy Studies 6 (2): 26–33. https://doi.org/10.7575/aiac.ijels.v.6n.2p.26.

- Adarkwah, M. A. 2022. “Anatomy of the ‘Free Senior High School’ Policy in Ghana and Policy Prescriptions.” Interchange 53 (2): 283–311. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10780-022-09459-3.

- Akakpo, B. 2021. Free SHS Good But Experiencing Bad Implementation – Former UG Vice-chancellor. Joy Online, March 17. https://www.myjoyonline.com/free-shs-good-but-experiencing-bad-implementation-former-ug-vice-chancellor/.

- Akyeampong, K., J. Djangmah, A. Oduro, A. Seidu, and F. Hunt. 2007. Access to Basic Education in Ghana: The Evidence and the Issues - Country Analytic Report. CREATE.

- Ansah, K. 2019. CHASS Demands Arrears of Mahama’s Progressive Free SHS Funds. Starrfm, December 19. https://starrfm.com.gh/2019/12/chass-demands-arrears-of-mahamas-progressive-free-shs-funds/.

- Asante, G. 2023. “The Politics of Social Policy in sub-Saharan Africa: A Configurational Approach to Fee-free Policies at the High School Level.” SAGE Open 13 (3): 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440231184970.

- Asante, G. 2024a. “The effects of cost elimination on secondary school enrolment in Sub-Saharan Africa.” Educational Review 76 (3): 561–585. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2022.2028732.

- Asante, G. 2024b. “Fee-free Educational Policy for Social Development: Examining the Conditions and the Social Benefits of Cost Elimination at the Upper-secondary Level in sub-Saharan Africa.” PhD, Budapesti Corvinus Egyetem. https://doi.org/10.14267/phd.2024010.

- Asante, G., G. B. Nkansah, and D. Agbee. 2024. “(De)centralisation in Fee-free Policymaking Process: Comparative Review of Progressive Free Senior High and Free Senior High School Policies in Ghana.” Policy Futures in Education 22 (1): 66–89. https://doi.org/10.1177/14782103221135919.

- Béland, D. 2005. “Ideas and Social Policy: An Institutionalist Perspective.” Social Policy and Administration 39 (1): 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9515.2005.00421.x.

- Béland, D. 2009. “Ideas, Institutions, and Policy Change.” Journal of European Public Policy 16 (5): 701–718. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501760902983382.

- Boasiako, A., and B. Asare. 2015. “The Multiple Streams Framework and the 1996 and 2007 Educational Reforms in Ghana.” Advances in Research 5 (3): 1–15. https://doi.org/10.9734/AIR/2015/17697.

- Correa, J. A., Y. Lu, F. Parro, and M. Villena. 2020. “Why is Free Education So Popular? A Political Economy Explanation.” Journal of Public Economic Theory 22 (4): 973–991. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpet.12396.

- DeLeo, R. A. 2018. “Indicators, Agendas and Streams: Analysing the Politics of Preparedness.” Policy & Politics 46 (1): 27–45. https://doi.org/10.1332/030557317X14974484611316.

- DeLeo, R. A., and A. Duarte. 2022. “Does Data Drive Policymaking? A Multiple Streams Perspective on the Relationship between Indicators and Agenda Setting.” Policy Studies Journal 50 (3): 701–724. https://doi.org/10.1111/psj.12419.

- Downs, A. 1957. “An Economic Theory of Political Action in a Democracy.” Journal of Political Economy 65 (2): 135–150. https://doi.org/10.1086/257897. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1827369.

- Economist Intelligence Unit. 2023. Democracy Index 2022: Frontline democracy and the battle for Ukraine. The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited. https://pages.eiu.com/rs/753-RIQ-438/images/DI-final-version-report.pdf?mkt_tok=NzUzLVJJUS00MzgAAAGJ8-bWy6KEkbfikdVrPQdVMAKfFGCBEcseBx-AiHEqtCfd_4nN5lZ9LnoAHeAHEmLvSXLOOLzQJ3GRP7a8Ui8ckp3K4sJAVkyXnXk7qqkzZgFXIg.

- Fosu, A. K. 2017. “Oil and Ghana’s Economy.” In The Economy of Ghana Sixty Years after Independence, edited by E. Aryeetey and R. Kanbur, 137–154. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198753438.003.0009.

- Frempong, K. D. 2020. Analysis of the Pre-2020 General Elections Survey. https://www.graphic.com.gh/images/2020/nov/26/DEPARTMENT_OF_POLITICAL_SCIENCE_PRE_2020_ELECTIONS_SURVEY_ANALYSIS.pdf.

- Gerring, J., and L. Cojocaru. 2016. “Selecting Cases for Intensive Analysis: A Diversity of Goals and Methods.” Sociological Methods & Research 45 (3): 392–423. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124116631692.

- Ghana. 1979. Constitution of the Third Republic of Ghana (Promulgation) Decree. https://constitutionnet.org/sites/default/files/constitution_of_the_third_republic_of_ghana.pdf.

- Ghana. 1993. Constitution of the Republic of Ghana. Accra: Ghana Publishing Company.

- Herweg, N., C. Huß, and R. Zohlnhöfer. 2015. “Straightening the Three Streams: Theorising Extensions of the Multiple Streams Framework.” European Journal of Political Research 54 (3): 435–449. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12089.

- Herweg, N., N. Zahariadis, and R. Zohlnhöfer. 2023. “The Multiple Streams Framework: Foundations, Refinements, and Empirical Applications.” In Theories of the Policy Process, edited by C. M. Weible, 5th ed., 29–64. Boulder, CO: Routledge.

- Howlett, M., and S. Giest. 2013. “The Policy-making process.” In Routledge Handbook of Public Policy, edited by E. Araral, S. Fritzen, M. Howlett, M. Ramesh, and W. Xun, 17–28. London; New York: Routledge.

- Kaufmann, D., and A. Kraay. 2023. Worldwide Governance Indicators, 2023 Update. https://www.govindicators.org/.

- Kingdon, J. W. 2014. Agendas, Alternatives, and Public Policies. 2nd ed. Harlow: Pearson.

- Kpessa, M. W. 2011. “The Politics of Public Policy in Ghana: From Closed Circuit Bureaucrats to Citizenry Engagement.” Journal of Developing Societies 27 (1): 29–56. https://doi.org/10.1177/0169796X1002700103.

- Little, A. W., and K. M. Lewin. 2011. “The Policies, Politics and Progress of Access to Basic Education.” Journal of Education Policy 26 (4): 477–482. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2011.555004.

- Maclure, S. 1990. “Beyond the Education Reform Act.” Policy Studies 11 (1): 6–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/01442879008423553.

- Ministry of Finance. 2015. The Budget Statement and Economic Policy—2016 Financial year. Accra-Ghana: Ministry of Finance (MoF). https://mofep.gov.gh/sites/default/files/budget-statements/2016-Budget-Statement.pdf.

- Mohammed, A. K. 2019. “Executive Dominance of Public Policy Making since Independence Ghana.” In Politics, Governance, and Development in Ghana, edited by J. R. A. Ayee, 191–212. Washington, DC: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Mohammed, A. K. 2020. “Does the Policy Cycle Reflect the Policymaking Approach in Ghana?” Journal of Public Affairs 20 (3): e2078. https://doi.org/10.1002/pa.2078.

- Mohammed, A. K., and A. B. Kuyini. 2021. “An Evaluation of the Free Senior High School Policy in Ghana.” Cambridge Journal of Education 51 (2): 143–172. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764X.2020.1789066.

- Nana Akufo-Addo, A. D. 2017. Full Text of President’s Speech at Launch of Free SHS. Adomonline. https://www.adomonline.com/full-text-presidents-speech-launch-free-shs/.

- Nana Akufo-Addo. 2014. “Tweet]” @NAkufoAddo, December 9. https://twitter.com/NAkufoAddo/status/542397733139517441.

- Onyango, G., ed. 2022. Routledge Handbook of Public Policy in Africa. 1st ed. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003143840.

- Opoku Prempeh, M. 2019. Implementation of Free SHS Programme by Hon. Minister for Education. Accra: Parliament of Ghana. http://ir.parliament.gh/bitstream/handle/123456789/1250/330628101521_0001.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

- Patton, M. Q. 2015. Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods: Integrating Theory and Practice. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications, Inc.

- Quaicoe, C. J. 2012. Nana Addo’s Free SHS Policy is a Fanciful Idea Just Like His ‘Trotro’ Boarding Antic. Peacefmonline, July 19. https://www.peacefmonline.com/pages/politics/politics/201207/124757.php.

- Tikly, L. 2016. “Education for All as a Global Regime of Educational Governance: Issues and Tensions.” In Post-education-for All and Sustainable Development Paradigm: Structural Changes with Diversifying Actors and Norms (International Perspectives on Education and Society, Vol. 29), edited by S. Yamada, 37–65. Leeds: Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- UIS [UNESCO Institute for Statistics]. 2023. UIS Statistics | Dataset. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation. http://data.uis.unesco.org/#.

- United Nations. 2020. The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2020. United Nations. https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2020/The-Sustainable-Development-Goals-Report-2020.pdf.

- Vijeyarasa, R. 2022. “How Presidents Shape the Law: A Taxonomy.” In The Woman President: Leadership, law and legacy for Women Based on Experiences from South and Southeast Asia, edited by R. Vijeyarasa, 36–65. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780192848918.003.0003.

- World Bank. 2021. World Development Indicators | DataBank. World Development Indicators. https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators#.

- Yanney, V. 2018. “Delayed Payment of Third Term (2017/2018) Free SHS Grant to Senior High Schools.” Conference of Heads of Assisted Secondary Schools (CHASS), Stadium-Accra: Ghana.

- Zohlnhöfer, R. 2009. “How Politics Matter When Policies Change: Understanding Policy Change as a Political Problem.” Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice 11 (1): 97–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/13876980802648300.

- Zohlnhöfer, R., N. Herweg, and F. Rüb. 2015. “Theoretically Refining the Multiple Streams Framework: An Introduction: Theoretically Refining the Multiple Streams Framework.” European Journal of Political Research 54 (3): 412–418. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12102.

Appendix

Table A1. Distribution of interview participants.