ABSTRACT

In response to global compound risks, resilience has been incorporated into China’s national governance discourse. This paper presents a quantitative analysis of 88 central-level policies building resilience capacity in China, to refine policy design to address complex risks more effectively. A comprehensive two-dimensional “policy tool-application field” analysis framework is developed based on policy tool theory and employs bibliometrics and content analysis methods. By extracting 210 policy analysis units corresponding to 289 coding reference points, we unveil the structural characteristics, policy themes, and distribution of policy tools on resilience building at the central level. Results show a notable upward trend in policy publication, forming a multi-agency policy-making network. We observe an imbalance in the structure of policy tools, with a strong reliance on environment-based policy tools. Policy tools are configured across all application fields. Supply-based policy tools are primarily applied for environmental and technological resilience, while demand-based tools find greater utilization in economic and organizational resilience dimensions. However, there is a neglect of social resilience. This paper recommends integrating policy tools to bolster resilience in diverse fields, and how to assess risks and their dynamic adjustments in resilience building as a significant direction in the future.

1. Introduction

Modern society has transitioned into a risk society, where risks are de-bounded in spatial, temporal, and social dimensions (Beck Citation2006). Global society is experiencing multiple challenges brought by compound risks such as the energy crisis and geopolitical conflict. The uncertainty and complexity of global risk, along with the public nature and limited effectiveness of their governance, pose a severe challenge to the existing governance paradigm (Fan Citation2018). Historical events such as the 2001 “911 attacks” in the US and the 2003 SARS outbreak in China have not only confirmed but also accelerated the global acceptance and recognition of Risk Society theory (Zhang Citation2017).

Unlike traditional risks, the risks present in a risk society are pervasive, structured, institutionalized, and uncertain. The resilience governance model, characterized by agility, comprehensiveness, and adaptability, can effectively respond to these challenges (Yi and Long Citation2022). A recent example is the COVID-19 pandemic, a global public health crisis as a “signal flag” for transforming China’s emergency management system and governance model. The technology-enabled prevention of the pandemic verifies that the coevolution of dynamic technology and static institutions furnishes transition opportunities (Zhang Citation2020). Resilience governance in the risk society context represents not only a transformation driven by the coupling of technology and institutions but also a crucial lever for urban security, management, and resource allocation efficiency.

Globally, resilience has been embedded in national and urban governance practices. The United States has developed the “National Disaster Recovery Framework (NDRF)” in 2011, offering a flexible structure that enables effective recovery support to states, tribes, and territories affected by disasters. In 2022, the EU introduced the “Cyber Resilience Act,” which mandates compulsory cybersecurity requirements for hardware and software products throughout their lifecycle to enhance the ability of manufacturers and users to resist cyber risks. Singapore has prioritized resilience on its national policy agenda “A Resilient Singapore Maps”, mapping out the Sustainable Singapore Blueprint (SSB), which deploys resilience actions in eco-smart, green and blue Spaces, and a green economy. These policies have deployed enhanced resilience actions in disaster mitigation, cybersecurity, and national strategic planning.

Similarly, China emphasizes the construction of resilience governance systems, a concrete manifestation of the modernization of national governance systems. National governance systems modernization refers to reforming and innovating governance institutions, mechanisms, and methods to align with contemporary societal demands. The Fifth Plenary Session of the 19th Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Central CommitteeFootnote1 introduced the concept of “resilience” into the national governance discourse system for the first time. This concept was incorporated into China’s top-level policy design as a component of high-quality development, with proposals to increase total factor productivity and enhance the resilience and security of China’s industrial and supply chains. The 14th Five-Year Plan puts forward the strategic direction of “leading with high-quality supply, enhancing the resilience of the supply system and its adaptability to domestic demand” and the goal of building a “resilient city”. The report of the 20th CCP National Congress has included “resilience” in the topic of high-quality development, proposing to “strive to improve the resilience and security level of the industrial chain supply chain” and to “build resilient and smart cities.” It is evident that resilience building has become an integral part of China’s governance system construction and serves as a crucial driving force for high-quality development.

In the context of the global risk society and the modernization of the national governance system, resilience has become a focal point in public management discourse due to the complex situation faced by public management characterized by extreme disasters, cross-border crises, and emerging risks (Zhang Citation2017). Cities worldwide suffer from inherently complex and interconnected problems, and their resolution requires governance systems that have the systemic capacity to cope with complexity (Spaans and Waterhout Citation2017). This has accelerated the shift of policy orientation from a single problem to a complex one. The policy should be designed to maintain functionality over time. Such functionality is especially important in an increasingly complex policy environment fraught with “wicked problems” and “black swans” (Capano and Woo Citation2018). Resilience exemplifies this function. The United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR) defines resilience as the capability of a system, community, or society to withstand, absorb, accommodate, adapt to, transform, and recover from the impacts of hazards in time and efficiently. This capacity encompasses the ability of a system to absorb disturbance, reorganize while changing (Walker et al. Citation2004), and adapt to risk disturbances. Embedding resilience into public policy design offers a novel solution for upgrading China’s governance system from a public management perspective. Moreover, it aligns with the urgent demand for social digital transformation.

Policies can be seen as representations encoded via struggles, compromises, authoritative public interpretations, and reinterpretations, and decoded through actors’ interpretations and meanings of their history, experiences, skills, resources, and context (Ball Citation1993). Policy text, the content of the policy document, is the core focus of analytical activity (Cardno Citation2019). Policy tools are techniques the government uses to achieve policy goals, which are embodied in policy and the ideas upon which they rest are as important as the exercise of power and influence that produces policy (Schneider and Ingram Citation1990). Given the above, this research raises questions about the structural characteristics of China’s resilience governance building policies. How are policy tools distributed? How can policy tool configuration be optimized? Through a combination of quantitative methods and policy tool theory, this paper examines China’s policy tool configuration, i.e., how different policy tools are distributed in multiple resilience fields, and whether the structure is reasonable. The paper is organized as follows. In the second section, the paper attempts to define resilience governance through a literature review. The third section presents the research design, constructing a “policy tool-application field” analysis framework to study central-level policies quantitatively. The rest of this paper analyzes the policy themes and evolution paths under China’s resilience governance agenda and discusses countermeasures for optimization.

2. Literature review

The concept of resilience originated in materials science and was initially used to describe the ability of materials to rebound or recoil (McAslan Citation2010). Holling (Citation2017) first applied the concept to ecological systems, highlighting resilience as crucial for determining the persistence of relationships within a system and as a measure of the ability of these systems to absorb changes in state variables, driving variables, and parameters, and persist. Since then, resilience has gained widespread acceptance across social science disciplines such as psychology, emergency management, and organization. Folke (Citation2006) delineates three levels of resilience: engineering resilience, focusing on recovery and constancy; ecological/system resilience, emphasizing persistence and robustness; and social-ecological resilience, highlighting adaptive capacity, transformability, learning, and innovation. Despite variations in interpretation across disciplines, a common emphasis exists on resilience’s capacity to withstand pressure, adapt, and recover, reflecting a consensus on the need for adaptation through endogenous crisis (Pan and Li Citation2019; Walker and Cooper Citation2011). From a public management standpoint, scholars have primarily discussed resilience in complex risk situations as a potential solution to crisis and disaster challenges (Boin and van Eeten Citation2013). Referring to classifying subjects at specific levels within social systems by Lin and Zhang (Citation2020), we define resilience in a risk society as the capacity of individuals, organizations, or systems to resist and recover from internal or external crisis risks while adapting, absorb learning, and maintaining stability.

Resilience has been integrated into governance through resilience governance, which centers on governance actions guided by resilience principles. Resilience governance exhibits unique attributes within the governance process and also serves to achieve resilience within the governance system (Jiang and Li Citation2022). While previous discussions on how to design public administrations often focused on values such as “efficiency” and “equity”, contemporary debates display an increasing concern for the “robustness”, “flexibility”, and “adaptability” of public governance (Duit Citation2016). Scholars have explored the intersection of governance theory and practice, particularly in emergency management and risk governance (Jin et al. Citation2023).

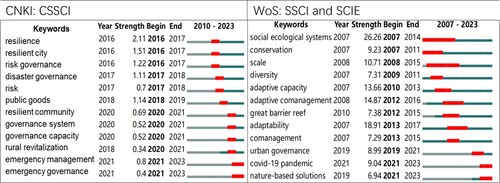

This research utilizes the China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) and Web of Science (WoS) core collection databases to investigate resilience governance. Using the search rule “resilience & governance”. 128 Chinese-language articles from the Chinese Social Sciences Citation Index (CSSCI) articles are retrieved from the CNKI database, dating back to 2010. Additionally, 4,611 journal articles are obtained from the WoS database from March 2007 to March 2023, using the retrieval strategy “article” with “WoS Index = SSCI and SCIE (Expanded).” After data cleaning and conversion using Citespace, burst term visualization is employed to identify sudden increases in research hotness in the field. For comparison purposes, shows the top twelve burst terms and strengths extracted from the research field over the past fifteen years.

Figure 1. Burst term visualization results on keywords in CNKI and WoS. Note: in CNKI, resilience: 韧性; resilient city: 韧性城市; risk governance: 风险治理; disaster governance: 灾害治理; risk: 风险; public good: 公共物品; resilient community: 韧性社区; governance system: 治理体系; governance capacity: 治理能力; rural revitalization: 乡村振兴; emergency management: 应急管理; emergency governance: 应急治理.

The start and end years of the burst represent the burst period of keywords, and the burst intensity is the frequency of keywords being used (Zhou et al. Citation2019). The red line segment indicates the burst period, from the start year to the end year, while the blue line segment indicates the appearance time of the keyword. Since 2010, twelve burst terms related to resilience governance have appeared in Chinese research. The sudden increase in the frequency of “resilience,” “resilient cities,” and “risk governance” in CSSCI papers since 2016 correlates closely with the adoption of the new development paradigm characterized by innovation, coordination, greenness, openness, and sharing during the 13th Five-Year Plan period. Notably, burst terms that have witnessed a significant surge since 2020 and persist to the present include “resilient communities,” “governance systems,” “governance capacity,” “rural revitalization,” and “emergency management,” with “emergency governance” emerging in 2021. Amidst the global public health crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, grassroots governance capacity has received considerable attention, with communities always at the forefront of epidemic prevention and control (Du Citation2021).

In WoS database, new burst terms continued to emerge from 2007 to 2013. Keywords with higher burst term intensities included “social ecological system”, “conservation”, “scale”, “adaptive capacity”, “adaptive management”, and “adaptability”, which continue to have an impact today. Burst terms from 2019 to the present include “urban governance,” “COVID-19 pandemic,” and “nature-based solutions,” indicating ongoing research trends and potential future directions. The burst term map reveals sustained hotness in topics related to ecology, social ecology, and emergency management. underscoring a growing interest in the intersection of resilience and governance. This trend is particularly pronounced in the context of urban governance and responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. The emergence of “nature-based solutions” as a burst term also signifies a shift towards more sustainable and environmentally conscious approaches to governance.

Researchers are increasingly expanding their attention to urban resilience, organizations, social capital, climate change, and other areas, reflecting the growing prominence of “resilience” as a sticking topic in public management due to frequent compound risks. Resilience governance, as a novel model in risk management, embodies national governance capacity and encompasses various types of disasters and processes (Yi and Long Citation2022). Based on cooperative governance and organizational learning mechanisms, resilience governance aims to enhance the adaptability of individuals, cities, and community systems to complex disaster risk impacts (Zhu and Liu Citation2020). Conceiving resilience both as a quality and a way of thinking could lead to a more constructive direction, emphasizing “self-governance” the link between the global and the local, and the link between the external and the internal, to facilitate more connectivity, and cooperative practices in mitigating change, complexity, and unpredictability (Korosteleva and Trine Citation2020).

Despite the growing breadth and depth of research in resilience studies, a significant body of work on resilience provides rationality for policies that shift public sector responsibilities to the private sector and individuals (Lin and Zhang Citation2020). The construction of resilience through policy design has not received adequate attention, potentially resulting in deviations in developing collaborative governance across multiple subjects. This paper addresses a gap by examining resilience-building efforts undertaken by the central government through quantitative analysis of central policies with policy tool theory. Consequently, its marginal contribution lies in providing a bibliometrics review of policies under China’s resilience governance agenda for the first time, while proposing a transferable analytical framework for resilience construction. The research’s significance lies in deepening policy audiences’ understanding of resilience-building practices. It also theoretically provides empirical evidence for future policy decision-making.

3. Research design and methodology

3.1. Methodology and data

Information such as policy subjects, policy objects, policy goals, and policy tools are all internalized in policy documents (Huang, Ren, and Zhang Citation2015). The research primarily adopts policy bibliometrics and content analysis, which quantitatively analyze the external structural characteristics and policy content of China’s resilience-building-related policy texts. By adopting the policy tool perspective, the study aims to uncover the number of policy issuances, the network of agencies involved in joint publication, and policy theme distribution. The goal is to summarize the evolution path of these policies and provide insights into their configurations.

This study utilizes “resilience” as a keyword and collects 535 effective policies. The sample collection and selection adhere to the principles of best effort collection, authority, and relevance. First, following the principle of best-effort collection, the Peking University Law (PKULAW)Footnote2 database is used as the primary data source. In China, “resilience” has been expressed differently in policies enacted at different times. Therefore, full-text searches are conducted using “resilience(韧性),” “recovery(恢复力),”, and “elasticity(弹性)” as keywords, as these are the three most frequently translated terms in Chinese literature (Wang et al. Citation2017). Resilience is regarded as an evolved version of recovery and elasticity, representing a higher-level conceptualization. Supplementary searches are performed on official websites of central government departments such as the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology website to ensure a high retrieval rate. The time frame for policy publications is from 2016 to January 31st, 2023.Footnote3 Policy types included laws and regulations, departmental regulations, party regulations, and industry regulations. Work declarations and publicity notices were excluded.

Adhering to the principle of authority, all policy samples must be formal documents issued by central-level agencies. Furthermore, to ensure the relevance of policies, clauses unrelated to resilience capacity are manually reviewed and excluded. As of February 17, 2023, 88 policy samples have been ultimately selected. displays policy samples. Given that China’s central-level resilience capacity policies are dispersed among fields related to scientific and technological innovation, emergency management, economic development, and urban-rural construction policies, no specific decisions focused on resilience capacity have been introduced. To improve the relevance and pertinence of this study, relevant clauses about resilience capacity are extracted from 88 policy samples for coding and content analysis.

Table 1. Policy document samples (partial).

3.2. Analysis framework

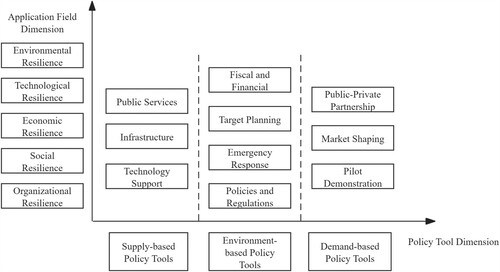

This study employs policy tool theory and resilience capacity to construct a “policy tool-application field” framework for analyzing the thematic content and structural characteristics of policies aimed at resilience capacity construction. presents the analysis framework.

3.2.1. X Dimension: policy tool

The selection of policy tools is an integral part of policy formulation and plays a role in policy implementation (Borrás and Edquist Citation2013). These tools encompass specific policy measures, methods, means, and mechanisms issued by the government to achieve particular public management goals (Lv Citation2006). The study of the policy tool dates back to Lowi and others who developed numerous typologies and theories between 1950 and 1980. Typological classifications of policy tools include Hood’s categorization into four sets using the NATO mnemonic: nodality, authority, treasure, and organization (Stead Citation2021). Vedung (Citation1998) proposed three categories based on the degree of coercion as the main criterion: sticks, carrots, and sermons. Howlett categorized government arrangements, policy regime logic and capacity issues, and technical instrument design into three levels of policy instrument choices for policy design (Howlett Citation2009). The essence of policy tool research lies not only in understanding individual policy tools but also in comprehending how these tools combine or bundle together and how they interact when combined, influencing policy effectiveness (Capano and Howlett Citation2020). Various studies on policy tools have proposed detailed classifications, extending the conceptualization of policy tools and identifying specific connotations and denotations. This not only renders the concept theoretically viable but also allows its operationalization for empirical research (Acciai and Capano Citation2018).

This study employs the policy tool dimensions proposed by Rothwell and Zegveld (Rothwell and Zegveld Citation1985), originating in the field of technological innovation, which includes supply-based, environment-based, and demand-based tools. This classification scheme categorizes policy tools based on different areas of interest and the levels at which they exert influence (Rothwell and Zegveld Citation1984). Their theory of policy tools is widely applied and effectively reveals the impact and role played in the policy-making process (Huang, Huang, and Su Citation2020). Each category of policy tools can further be subdivided into various operational-level tools (Dong and Xu Citation2017). Drawing upon the analysis of resilience governance discussed in the preceding section and incorporating insights from existing research, this study proposes a categorization for policy tools aimed at enhancing resilience capacity. presents an overview of the classification and definitions of policy tools utilized in resilience building efforts.

Table 2. Classification and definition of policy tools.

Supply-based policy tools encompass direct means by which the central government fosters resilience capacity through infrastructure construction, technological support, and public services. These policy tools demonstrate the direct role of policy in promoting the development of resilience capacity. Environment-based policy tools involve the creation of a favorable external environment for resilience capacity development through fiscal and financial policies, target planning, emergency response, and policy regulations. These policy tools have an indirect impact on the development of resilience capacity. Demand-based policy tools promote resilience capacity from the perspective of market entities by reducing market resistance. They are further divided into public-private cooperation, market shaping, and pilot demonstration, reflecting the role of policy in driving the development of resilience capacity. These different policy tools provide approaches to fostering resilience capacity, utilizing both direct and indirect means.

3.2.2. Y Dimension: application field

By extracting keywords from the Gooseeker platform, this study divides the Y dimension into five resilience dimensions: environmental, technological, social, organizational, and economic resilience. This classification is based on recognized divisions by domestic and foreign scholars and the City Resilience Index (CRI) supported by the Rockefeller Foundation (CRI).Footnote4 Environmental resilience refers to the infrastructure’s ability to possess fixed resistance and redundancy, enabling it to maintain usual operations and provide public services after shock (Qiu Citation2018). Technological resilience refers to the use of information technology such as big data and cloud computing in government governance and disaster prevention and mitigation, along with the interconnection and intelligently processing of information (Zhang and Xiao Citation2020). Economic resilience pertains to preventing, responding to, and recovering from economic risks3. Social resilience focuses on individuals, communities, and social organizations’ ability to recover from crises or actively respond to them (Maguire and Patrick Citation2007). For instance, volunteer networks developed by social organizations can quickly respond in the aftermath of disasters. Organizational resilience refers to government departments’ capacity to maintain stable functions and ensure public confidence, including the use of pilot demonstrations (Qiu Citation2018).

3.3. Policy content coding

This study uses policy content promoting resilience capacity building as the basic unit of analysis and decomposes it according to the policy tool-application field framework. Policy samples are coded using Nvivo 12 Plus software. In the policy tool dimension, clauses are manually reviewed, and nodes are created for supply-based, environment-based, and demand-based policy tools and their sub-classifications. 210 analysis units corresponding to 289 coding nodes are mined for the corresponding policy content. Notably, there are instances where one analysis unit corresponds to multiple policy tool type nodes during coding, and not all policy tools have unique corresponding resilience categories in the application field dimension. Reference nodes from the policy tool dimension are allocated to the five sub-classifications of environmental, technological, economic, social, and organizational resilience in the application field dimension. Finally, the distribution of reference points in the two-dimensional framework is quantified. shows an example of policy sample content coding.

Table 3. Policy content coding (partial).

4 Results

4.1. External structural characteristics: policy issuing number and agency

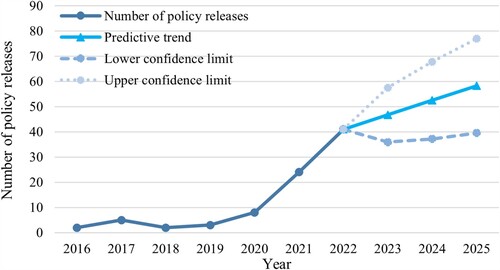

This study examines the external structural characteristics of the selected policy samples. shows the longitudinal evolution of the number of policy documents published from 2016 to 2022. Before 2019, a relatively small number of relevant policy documents were issued. Since 2019, there has been a noticeable upward trend in the issuance of policy documents related to resilience capacity construction. This trend intensified from 2021, with a sharp increase in the number of policies related to resilience construction, with as many as 41 policies issued in 2022.

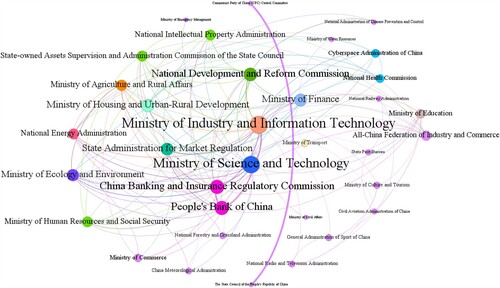

Regarding policy issuers, shows a multi-departmental collaborative network diagram for resilience capacity construction based on the co-occurrence matrix of issuing agencies of the 88 policies analyzed. The width of the line represents the correlation strength between nodes, with each node representing an agency. Additionally, the size of each node indicates the co-occurrence frequency, i.e. the more frequently an agency collaborates with other agencies in policy issuance, the larger the node will be. It is evident that in recent years, a multi-agency network has formed, with the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT), the Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST), and the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) being the primary departments issuing joint documents and collaborating extensively with other departments. Among them, MIIT participated in publishing 38 policies related to resilience capacity construction, highlighting the driving role of technology in this domain and underscoring resilience capacity becoming a considerable part of China’s governance system in addressing emerging challenges. Furthermore, there is a discernible trend towards joint policy issuance by the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and the State Council. As macro leadership departments, the State Council independently issued 19 policies, accounting for 16.72% of the policy samples, reflecting the macro leadership role of these entities in policy formulation.

4.2. Policy tool dimension results

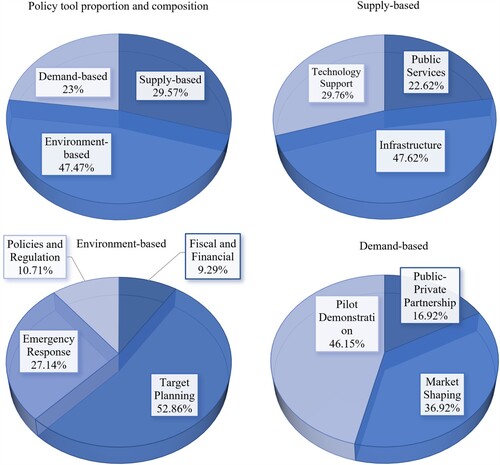

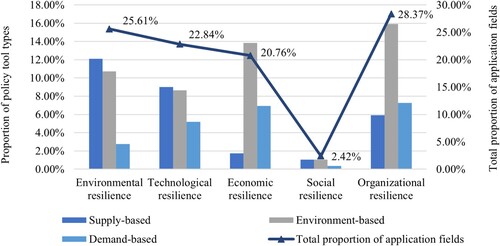

Based on the coding results, this study conducts a frequency analysis of the overall structural distribution of policy tools. displays the proportions and composition of supply-based, environment-based, and demand-based policy tools. While all three types of policy tools are employed comprehensively, the structure of policy tools for resilience capacity appears unbalanced, with significant differences in the proportions of the three types used.

Environment-based policy tools exhibit the highest frequency of use (47.47%), with target planning (52.86%) and emergency response (27.14%) being favored by policymakers. This reflects the central government’s emphasis on building resilience capacity at the macro planning level since the 13th Five-Year Plan period, wherein goals and tasks for enhancing resilience in the economy, environment, and security areas were clarified. Additionally, in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, China’s emergency management system has undergone rapid adjustments. The emergency command mechanism transitioned from a joint party-government-military system to one with separate responsibilities for each entity, highlighting the effectiveness and urgency of resilience governance models with adaptive capacity as the core link (Shan Citation2022). However, policy regulations (10.71%) and finance (9.29%) are utilized less frequently, indicating that these sub-tools receive less attention from the government and that the legal effectiveness of policy tools is not prominent. Policy regulation serves as a vital environmental safeguard for resilience capacity development. However, the use of policy regulations (10.71%) is comparatively low, suggesting insufficient emphasis on strengthening policy supervision.

In comparison, supply-based policy tools (29.57%) and demand-based policy tools (22.96%) are utilized less frequently, but their proportions do not differ significantly. Among supply-based policy tools, infrastructure (47.62%) is a focal point for resilience capacity building, with technology support (29.76%) and public services (22.62%) providing direct impetus. These three complement each other, with technology support facilitating the building of safe, green, innovative, intelligent, and resilient cities through systematic construction and transformation of urban infrastructure. On the other hand, it enhances software and hardware resilience capacity through risk-warning platforms, technology innovation platforms, collaborative services, and information-sharing platforms. Although demand-based policy tools are less frequently utilized overall, further analysis of their subcategory distribution reveals a more balanced internal structure with pilot demonstrations (46.15%) and market shaping (36.92%) being predominant. In policy content, central departments have conducted pilot demonstrations for urban modernization, such as transportation integration in the Chengdu-Chongqing Economic Circle, to lead resilient city construction and cultivate industrial ecology-led enterprises to develop domestic markets. However, a small portion of policy content involves public-private partnerships (16.92%), indicating insufficient attention from government departments to multi-party participation in resilience capacity construction by enterprises, citizens, institutional organizations, and other stakeholders.

4.3. Policy tool-application field cross analysis

A cross-analysis of policy tools in different resilient dimensions is conducted using the previously described analytical framework. The findings are presented in a two-dimensional distribution map of China’s resilience capacity building policies. Different policy tools emphasize varying aspects within different applicable fields. suggests an uneven vertical distribution of policy tools, with the majority concentrated on three primary fields: organizational resilience (28.37%), environmental resilience (25.61%), and technological resilience (22.84%). Policymakers have also focused on economic resilience (20.76%). However, the utilization of policy tools in social resilience is deficient, constituting only 2.42% of the distribution, reflecting a lack of policy guidance for incorporating diverse social forces into building resilience.

Horizontally, environmental resilience relies on supply-based infrastructure, supplemented by target planning and emergency response methods. Urban infrastructure has become an important means of enhancing the disaster resistance capacity of urban physical systems (He and Cao Citation2023). In 2017, China’s Earthquake Administration deployed the Resilient Urban and Rural Plan to improve urban and rural recovery capabilities through the development and widespread adoption of advanced seismic technologies. Comprehensive planning guides resilience construction, while infrastructure and emergency response tools support hardware facilities and management systems. Subsequent plans such as the 13th Five-Year Plan for Public Safety Science and Technology Innovation and the Outline for Modernization of Earthquake Prevention and Disaster Reduction in the New Era (2019-2035) also emphasized the role of infrastructure safety in enhancing resilience.

The technological resilience field encompasses information technology and corresponding application capabilities that support resilience building. Various policy tools in technological resilience are more evenly distributed compared to other fields, with greater utilization of technology support and target planning, as well as demand-based pilot demonstrations, and market shaping methods. In economic resilience, fiscal finance and target planning create a conducive external environment for building resilience capabilities. Market shaping methods stimulate market vitality by dismantling industry monopolies and local protectionism. In organizational resilience, environment-based target planning and emergency response play significant roles, while demand-based pilot demonstrations and supply-based public services are also widely employed. Shaping organizational resilience involves the allocation and deployment of organizational resources (Kantur and Arzu Citation2012), encompassing planning, implementation, and evaluation throughout the cycle. Thus, the comprehensive participation of various policy tools is necessary to promote the government’s ability to maintain stability during crises. However, the use of policy tools in social resilience is severely deficient, particularly in demand-based policy tools (0.35%) such as public-private cooperation and market shaping methods being weak. Social resilience, with its diverse attributes and differences (Maguire and Patrick Citation2007) among various actors, poses challenges for policy implementation. Nevertheless, it remains an indispensable field in resilience building capacity and serves as a driving force for the sustainable development of other resilience fields.

5. Discussion and conclusion

5.1. Discussion

This research provides insights into the structural dynamics and strategic allocation of policy tools on China’s resilience construction. The longitudinal evolution of these policies reveals a clear growth trend in their publication; however, their focus remains inadequate. In 2016, the first year of the 13th Five-Year Plan, policies on resilience capabilities were primarily concerned with physical attributes. Subsequently, the broader concept of resilient governance capacity has been introduced into the policy arena. However, in terms of text attributes, only relevant policies exist and no special policies have been introduced to promote resilience capacity building (Dai and Gao Citation2023). Relevant policies are scattered across various fields such as economic development, finance, emergency management, science and technology, transportation, and energy. On one hand, this is because the flexibility and redundancy inherent in resilience governance apply to policies in multiple fields under the governance system. On the other hand, it also exposes the problem of policy dispersion and insufficient focus on resilience governance capability construction.

Regarding the synergy of policy subjects, a multi-subject collaborative document network has formed with the Central Committee of the CCP and the State Council jointly administering planning and decision-making guidance. The Ministry of Industry and Information Technology, the Ministry of Science and Technology, and the National Development and Reform Commission are core subjects in this network. This reflects the importance attached to resilience capacity building policies by top-level design, which involves multiple departments with clear coordination relationships. Resilience capacity building is jointly promoted from multiple dimensions including environmental, technological, economic, organizational, and social.

The utilization of policy tools exhibits a diversity of overarching types yet is marked by internal structural imbalance. Primarily, policy tools employed predominantly feature an environment-based orientation, fostering a conducive environment and macro-level guarantee for sustained resilience governance capacity development. This underscores the prevalent policy inclination towards planning, fiscal, and regulatory measures cultivating an environment supportive of enduring governance capacity evolution. Demand-based policy tools, which also play an indirect role, account for only 22.96% of the total. While supply-based tools intended to directly support the development of resilient governance capacity in terms of hardware and software constitute less than thirty percent (29.57%) of the total employed. The uneven use of demand-based and supply-based policy tools may affect foundation stability and long-term planning for resilience capacity.

Across five fields, demand-based pilot demonstrations, market shaping, and public-private cooperation serve as robust responses to market demands and reduce uncertainty, thereby stimulating demand. Additionally, the provision of infrastructure, technology, and public services stands out as a primary requirement in this context. Demand-based policy tools are directed towards enhancing intergovernmental information exchange and cooperation, while also emphasizing the role of the public and social organizations in facilitating information communication (Zhang et al. Citation2021). Consequently, the disproportionate utilization of demand-based and supply-based policy tools is bound to impact the solidity of the foundation for resilience capacity building and its enduring viability, potentially leading to a top-heavy policy execution.

When policy tools are deployed in applicable domains, they cover five dimensions of resilience: environmental, technological, economic, social, and organizational. However, there is a noticeable bias in the sub-category policy tools, with uneven distribution across domains, particularly favoring organizational and environmental resilience while neglecting social resilience. Supply-driven policy tools, such as infrastructure and technological support, are heavily utilized in the environmental and technological resilience domains. Economic and organizational resilience building relies more on environment-based goal planning and emergency response, with some utilization of demand-based market shaping and pilot demonstration approaches. This indicates a focus from the central government on enhancing medium-to-long-term economic resilience and improving government functions and urban security stability. The social resilience domain lacks policy attention, with significantly lower utilization compared to other resilience dimensions. Despite the presence of public services, public-private partnerships, fiscal finance, and policy finance, their utilization is notably lower than other measures.

The alignment of policy tools with application fields is an effective means of enhancing resilience capabilities. By combining supply-based, environment-based, and demand-based policy tools, the central government can effectively support the growth of resilience capacity in a variety of ways. Leveraging the foundational role of technology support and infrastructure development is crucial, particularly in enhancing social, economic, and organizational resilience. A notable lack of demand-based policy tools exists in building social resilience. Therefore, alongside strengthening the overall application of policy tools in the social resilience field, the government should also emphasize the use of demand-based tools including public-private partnerships and market-shaping mechanisms, which can effectively steer and encourage societal participation and mobilize market resources. The configuration of environmental sub-policy tools within organizational and economic resilience fields should remain adaptable to evolving policies, regulations, and targeted plans to ensure robust financial support for resilience-related endeavors. Constructing demand-based policy tools for environmental resilience is advantageous for encouraging innovation from a market perspective and reducing market barriers (Dong and Xu Citation2017). Therefore, governments should increase the utilization of public-private cooperation models and pilot demonstration projects to bolster facility and technology redundancy, enhance anti-interference capabilities, and promote benefit sharing. Although this study’s discussion on resilience governance capabilities focuses on government functions, practice shows that building multi-domain resilience requires encouraging private sector participation by guiding them towards involvement.

It should be highlighted that resilience has emerged as a prevalent term in contemporary public management and public policy discourse. The robustness of a policy idea is constructed through successful framing strategies and its repeated utilization over time (Béland and Cox Citation2024). We propose that resilience is not newly created but a re-packaging of past policy terminology such as constancy, sustainability, robustness, flexibility, adaptability, and recovery. While the term “resilience” first appeared in the discourse of China’s national governance framework in 2020, it is clear that policymakers have long been constructing this policy idea. From this perspective, resilience has continuously influenced policy formulation and governance practice. Today the global risk society is amplifying the influence of resilience governance on China’s policy approach. External risks and crisis disruptions are logical starting points for resilience governance (Hu and Li Citation2024). The de-localization, incalculableness, and non-compatibility of the global risk society (Beck Citation2006), necessitate that public policy design adjusts to a turbulent world, leading to the rise of resilience governance.

5.2. Conclusion

By incorporating resilience-building policies into a two-dimensional framework that examines the policy tool-application field, we delineated a top-level resilience governance system to a certain extent. This facilitates the balancing of policy tool application for resilience building while enhancing the degree of adaptability between these tools and resilience objectives. The findings provide insights for future research focused on resilience governance.

First, the policy understanding and practice of resilience vary in different national contexts, we utilize the framework of policy tools-resilience application field to examine the policy characteristics of resilience building. We observe a strong reliance on environment-based policy tools by the central government in China, alongside notably weak in the social resilience field. The analysis framework can serve as an evaluation model for assessing resilience-building efforts in other states, providing specific societal needs and basic conditions in each setting.

Second, the finite nature of government resources determines that the formulation and implementation of public policies must prioritize certain issues. Problem salience is an important factor influencing the prioritization of policy issues under limited resources (Halpin, Fraussen, and Nownes Citation2018). Existing resilience-related policy provisions in China are implemented to address specific problems within subsystems, thus dispersed across policies on technology, emergency response, and urban and rural construction. The formulation of public policies is an ongoing process requiring continuous evaluation and adjustment. In the future, as specialized resilience policies are developed, how the government evaluates the salience of risks problems based on existing resources and allocates resources accordingly will be crucial. This will establish the legitimacy of the national resilience governance system. We also note that China’s central government recently issued “Guidelines for Resilient Urban Planning and Land Policies with Integrated Regular and Emergency Functions”,Footnote5 which is intended to leverage territorial spatial planning to guide resilience building. This plan addresses both national security and development problems and deploys different resource allocation paths for regular and emergencies. Therefore, we suggest that future research should assess the prioritization of risks problems and their dynamic adjustment throughout the entire cycle of resilience building.

Lastly, this research has several limitations. There is an insufficient collection of policies that do not explicitly contain “resilience” but have similar semantic expressions. Follow-up research may involve practical thematic exploration of qualitative data and thematic analysis validation, and for comparing similar corpora to explore semantic similarities and differences (Valdez, Pickett, and Goodson Citation2018). Meanwhile, internal mechanisms explaining the configuration status must consider the specific political background and practice. Despite this research providing the current state of China’s resilience construction policy, the updating lag between policy tool application and their effectiveness restricted the research procedure. Future research could consider policy dynamics analysis such as phase division evolution.

Acknowledgement

We benefited greatly from the comments of participants at the 2023 Asia-Pacific Public Policy Network (AP-PPN).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are publicly available in the Peking University Law (PKULAW) database (https://www.pkulaw.net/), the State Council of the People's Republic of China (https://www.gov.cn/), the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology of the People's Republic of China (https://www.miit.gov.cn/).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Jing Zhang

Jing Zhang is an associate professor at the School of Marxism Studies, Beijing University of Posts and Telecommunications. Her work is situated in web-based ideological and political education, and cyberspace governance.

Xingnan Guo

Xingnan Guo is a master’s student at the School of Social Sciences, Nanyang Technological University. Her research focus is on innovative governance and policy measurement.

Wei He

Wei He is a professor at the School of Economics and Management, Beijing University of Posts and Telecommunications. His research interests include new generation information technology and Management, cyberspace governance, and sustainable development.

Notes

1 See, the Xinhua News Agency. (Authorized release) Fifth Plenary Session of 18th CCP Central Committee. http://www.xinhuanet.com/politics/2020-10/29/c_1126674147.htm (in Chinese)

2 The main database used in this study is the Peking University Law (PKULAW) which is the most authoritative legal information retrieval platform in China. Its Chinese translation is named “北大法宝”.

3 Compared with previous years, the number of central policy documents containing the word “resilience” has shown a significant upward trend in 2023. This paper selected three policy samples published in January 2023 for research purposes. They are respectively “Opinions on Key Tasks of Comprehensive Rural Revitalization in 2023”, “Guiding Opinions on Promoting the Development of Energy Electronic Industry”, and “Notice on Measures to Help Small, Medium and Micro Enterprises Maintain Steady Growth, Adjust Structure and Enhance Capability”.

4 See, the Arup. City Resilience Index[R]. United Kingdom, Arup, 2015. https://www.arup.com/perspectives/publications/research/section/city-resilience-index

5 See, the Ministry of Land and Resources. http://finance.people.com.cn/n1/2024/0515/c1004-40236339.html. The Office of the Ministry of Land and Resources issued the “Guidelines for Resilient Urban Planning and Land Policies with Integrated Regular and Emergency Functions”, in Chinese named “平急功能复合的韧性城市规划与土地政策指引”.

References

- Acciai, Claudia, and Giliberto Capano. June 2018. “Climbing Down the Ladder: A Meta-Analysis of Policy Instruments Applications.” In IPPA International Workshops on Public Policy, University of Pittsburgh, 26–28. https://www.ippapublicpolicy.org/file/paper/5b2926cf8c098.pdf.

- Ball, Stephen J. 1993. “What is Policy? Texts, Trajectories and Toolboxes.” Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education 13 (2): 10–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/0159630930130203.

- Beck, U. 2006. “Living in the World Risk Society: A Hobhouse Memorial Public Lecture Given on Wednesday 15 February 2006 at the London School of Economics.” Economy and Society 35 (3): 329–345. https://doi.org/10.1080/03085140600844902.

- Béland, Daniel, and Robert Henry Cox. 2024. “How Framing Strategies Foster Robust Policy Ideas.” Policy and Society. https://doi.org/10.1093/polsoc/puae014.

- Boin, Arjen, and Michel J. van Eeten. 2013. “The Resilient Organization.” Public Management Review 15 (3): 429–445. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2013.769856.

- Borrás, Susana, and Charles Edquist. 2013. “The Choice of Innovation Policy Instruments.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 80 (8): 1513–1528. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2013.03.002.

- Capano, Giliberto, and Michael Howlett. 2020. “The Knowns and Unknowns of Policy Instrument Analysis: Policy Tools and the Current Research Agenda on Policy Mixes.” SAGE Open 10 (1): 215824401990056. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244019900568.

- Capano, Giliberto, and Jun Jie Woo. 2018. “Designing Policy Robustness: Outputs and Processes.” Policy and Society 37 (4): 422–440. https://doi.org/10.1080/14494035.2018.1504494.

- Cardno, Carol. 2019. “Policy Document Analysis: A Practical Educational Leadership Tool and a Qualitative Research Method.” Educational Administration: Theory and Practice 24 (4): 623–640. https://doi.org/10.14527/kuey.2018.016.

- “Cyber Resilience Act - Factsheet.” Shaping Europe’s Digital Future, December 1, 2023. https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/cyber-resilience-act-factsheet.

- Dai, Jiaxin, and Fan Gao. 2023. “Consensus and Difference: Text Analysis of Privacy Protection Central and Local Policies of Chinese Government Data Opening from the Perspective of Policy Tools.” Library and Information Service 1–11. https://doi.org/10.13266/j.issn.0252-3116.2023.07.002. (in Chinese).

- Dong, Yanchun, and Zhili Xu. 2017. “A Comparative Study of Policy Tools for Innovation Strategic Planning Between China and America.” Science & Technology Progress and Policy 34 (7): 100–104. (in Chinese).

- Du, Haifeng. 2021. “Introduction: Resilience Governance, Urban Resilience, and Rural Resilience.” Journal of Public Administration 14 (4): 1–3. (in Chinese).

- Duit, Andreas. 2016. “Resilience Thinking: Lessons for Public Administration.” Public Administration 94 (2): 364–380. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12182.

- Fan, Ruguo. 2018. ““World Risk Society” Governance: The Paradigm of Complexity and Chinese Participation” Social Sciences in China 39 (2): 77–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/02529203.2018.1448077.

- Folke, Carl. 2006. “Resilience: The Emergence of a Perspective for Social–Ecological Systems Analyses” Global Environmental Change 16 (3): 253–267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2006.04.002.

- Halpin, Darren R., Bert Fraussen, and Anthony J. Nownes. 2018. “The Balancing Act of Establishing a Policy Agenda: Conceptualizing and Measuring Drivers of Issue Prioritization Within Interest Groups.” Governance 31 (2): 215–237. https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12284.

- He, Lanping, and Huiyuan Cao. 2023. “The Integration of Resilience Thinking Into the Policy Evolution and Structural Hierarchy of Governance Modernization.” Jiangsu Social Sciences 326 (1): 132–141. (in Chinese).

- Holling, C. S. 2017. “Resilience and Stability of Ecological Systems (1973).” The Future of Nature 2017:245–260. https://doi.org/10.12987/9780300188479-023.

- Howlett, M. 2009. “Governance Modes, Policy Regimes and Operational Plans: A Multi-Level Nested Model of Policy Instrument Choice and Policy Design.” Policy Sciences 42 (1): 73–89. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-009-9079-1.

- Hu, Wei wei, and Yi fan Li. 2024. “The Model Construction, Occurrence Logic and Driving Mechanism of Digital Empowered Rural Resilient Governance.” Journal of Huaqiao University(Philosophy & Social Sciences) (02): 23–33. https://doi.org/10.16067/j.cnki.35-1049/c.2024.02.003. (in Chinese)

- Huang, Xinping, Cui Huang, and Jun Su. 2020. “Textual and Quantitative Research on Chinese Science and Technology Finance Development Policies Based on Policy Tools.” Journal of Intelligence 39 (1): 130–137. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1002-1965.2020.01.018 (in Chinese)

- Huang, Cui, Tao Ren, and Jian Zhang. 2015. “Policy Documents Quantitative Research: A New Direction for Public Policy Study.” Journal of Public Management 12 (2): 129–137 + 158–159. https://doi.org/10.16149/j.cnki.23-1523.2015.02.012 (in Chinese)

- Jiang, Xiaoping, and Min Li. 2022. “Governance Resilience: The Dimensions and Validity of Chinese Social Governance in the New Era.” Administrative Tribune 29 (3): 5–12. https://doi.org/10.16637/j.cnki.23-1360/d.2022.03.001. (in Chinese)

- Jin, Xiaolin, Chenxi Wang, Lu Zhang, and Yinxi Liu. 2023. “Research on the Governance of Smart Communities in China from the Perspectives of Digital Empowerment and Resilient Governance.” Scientific Management Research 41 (1): 90–99. (in Chinese)

- Kantur, Deniz, and İşeri-Say Arzu. 2012. “Organizational Resilience: A Conceptual Integrative Framework.” Journal of Management & Organization 18 (6): 762–773. https://doi.org/10.5172/jmo.2012.18.6.762.

- Korosteleva, Elena A., and Flockhart Trine. 2020. “Resilience in EU and International Institutions: Redefining Local Ownership in a New Global Governance Agenda.” Contemporary Security Policy 41 (2): 153–175. https://doi.org/10.1080/13523260.2020.1723973.

- Lin, Xue, and Haibo Zhang. 2020. “The Soft Power of Urban Resilience: Construction of the Conceptual Framework of Local Government Resilient Capability.” Administrative Tribune 27 (5): 88–94. https://doi.org/10.16637/j.cnki.23-1360/d.2020.05.012. (in Chinese)

- Lv, Zhikui. 2006. “Selection of Public Policy Tools - A New Perspective on Policy Implementation Research.” Pacific Journal 5:7–16. (in Chinese).

- Maguire, Brigit, and Hagan Patrick. 2007. “Disasters and Communities: Understanding Social Resilience.” Australian Journal of Emergency Management 22 (2): 16–20.

- McAslan, Alastair. 2010. Adelaide: Torrens Resilience Institute 1: 1–13.

- Pan, Xiaojuan, and Zhaorui Li. 2019. “Exploration on the Concept of Administrative Resilience.” Chinese Public Administration 404 (2): 98–101 + 151. (in Chinese)

- Qiu, Baoxing. 2018. “Methods and Principles of Designing Resilient City Based On Complex Adaptive System Theory.” Urban Development Studies 25 (10): 1–3. (in Chinese)

- Rothwell, Roy, and Walter Zegveld. 1984. “An Assessment of Government Innovation Policies.” Review of Policy Research 3 (3–4): 436–444. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-1338.1984.tb00138.x.

- Rothwell, Roy, and Walter Zegveld. 1985. Reindustrialization and Technology. Harlow: Longman.

- Schneider, Anne, and Helen Ingram. 1990. “Behavioral Assumptions of Policy Tools.” The Journal of Politics 52 (2): 510–529. https://doi.org/10.2307/2131904.

- Shan, Shan. 2022. “The Major Achievements and Important Experience in the Construction of China’s Emergency Management System for Public Health Emergencies Since the 18th National Congress of the CPC.” Journal of Management World 38 (10): 70–78. (in Chinese).

- Spaans, M., and B. Waterhout. 2017. “Building up Resilience in Cities Worldwide – Rotterdam as Participant in the 100 Resilient Cities Programme.” Cities 61:109–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2016.05.011.

- Stead, D. 2021. “Conceptualizing the Policy Tools of Spatial Planning.” Journal of Planning Literature 36 (3): 297–311. https://doi.org/10.1177/0885412221992283.

- U.S. Department of Homeland Security. “National Disaster Recovery Framework.” FEMA.gov. Accessed February 16, 2024. https://www.fema.gov/emergency-managers/national-preparedness/frameworks/recovery.

- Valdez, Danny, Andrew C. Pickett, and Patricia Goodson. 2018. “Topic Modeling: Latent Semantic Analysis for the Social Sciences.” Social Science Quarterly 99 (5): 1665–1679. https://doi.org/10.1111/ssqu.12528.

- Vedung, Evert. 1998. “Policy Instruments: Typologies and Theories.” In Carrots, Sticks, and Sermons: Policy Instruments and Their Evaluation, edited by Marie-Louise Bemelmans-Videc, Ray C. Rist, and Evert Vedung, 21–58. Piscataway, NJ & London: Transaction Publishers. https://www.academia.edu/42748022/Policy_Instruments_Typologies_and_Theories.

- Walker, Jeremy, and Melinda Cooper. 2011. “Genealogies of Resilience.” Security Dialogue 42 (2): 143–160. https://doi.org/10.1177/0967010611399616.

- Walker, Brian, C. S. Holling, Stephen R. Carpenter, and Ann P. Kinzig. 2004. “Resilience, Adaptability and Transformability in Social-Ecological Systems.” Ecology and Society 9 (2), https://doi.org/10.5751/es-00650-090205.

- Wang, Hui, Yunxue Xu, Siqi Lu, Yilu Ren, and Weining Xiang. 2017. “A Comparative Study of Chinese Translation of Resilience Terminology in Socio-Ecological System and Its Related Research Fields” Urban Planning International 32 (4): 29–39. (in Chinese) https://doi.org/10.22217/upi.2017.128.

- Yi, Chengzhi, and Cuihong Long. 2022. “Risk Society,Resilience Governance and the Modernization of National Governance Capability.” The Journal of Humanities 320 (12): 78–86. (in Chinese)

- Zhang, Haibo. 2017. “Risk Society and Public Management.” Journal of Nanjing University (Philosophy, Humanities and Social Sciences) 54 (4): 57–65 + 158. (in Chinese)

- Zhang, Yan. 2020. “The Map Is Not the Territory: Coevolution of Technology and Institution for a Sustainable Future.” Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 45:56–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2020.08.017.

- Zhang, Longhun, and Ke Xiao. 2020. “Risk Management of Megacities in the Application of Artificial Intelligence: Coincidence, Technological Changes and Paths.” Theory Monthly 465 (9): 60–72. https://doi.org/10.14180/j.cnki.1004-0544.2020.09.007. (in Chinese).

- Zhang, Ru, Xiaoying Zhou, Junliang Pei, and Xiaoning Yu. 2021. “Quantitative Analysis of Policy Tools for Emergency Information Management of Public Health Emergencies in China.” Information and Documentation Services 42 (03): 44–51. (in Chinese).

- Zhou, L., P. Zhang, Z. Zhang, L. Fan, S. Tang, K. Hu, N. Xiao, and S. Li. 2019. “A Bibliometric Profile of Disaster Medicine Research from 2008 to 2017: A Scientometric Analysis.” Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness 13 (2): 165–172. https://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2018.11.

- Zhu, Zhengwe, and Yingying Liu. 2020. “Resilient Governance: A New Approach for Risk and Emergency Management.” Administrative Tribune 27 (5): 81–87. (in Chinese).