?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This study examined whether students’ bystander behaviours in peer victimisation were associated with individual (IMD) and classroom collective moral disengagement (CMD). Self-report survey data were analysed from 1577 Swedish students in fifth grade. Multilevel analyses revealed that, when witnessing peer victimisation, students more often sided with the victimisers if they belonged to classrooms high in CMD, especially if they simultaneously were high in IMD. Furthermore, staying passive was associated with higher levels of IMD and CMD, whereas defending the victims was associated with lower levels of IMD and CMD. Taken together, our findings suggest that moral disengagement beliefs both at the individual and at the classroom-level contribute to explain variability in students’ bystander behaviours, which has potential implications for prevention and intervention work.

Peer victimisation is a widespread problem among children and adolescents in schools and has been associated with mental health problems (Hanish & Guerra, Citation2002; Reijntjes et al., Citation2010) and poorer academic achievement (Schwartz et al., Citation2005). In most peer victimisation episodes, peers are present as bystanders (e.g. Atlas & Pepler, Citation1998; Jones et al., Citation2015; Lynn Hawkins et al., Citation2001). According to the participant role approach (Salmivalli et al., Citation1998), bystanders can play different roles: the assistant (joins the victimisers), the reinforcer (encourages or incites the victimisers), the outsider (remains passive or neutral), and the defender (helps or supports the victim) role. Because previous studies (Jungert et al., Citation2016; Sutton & Smith, Citation1999; Thornberg & Jungert, Citation2013) have shown that the assistant and reinforcer role load into the factor, the current study treats them as a single construct that we refer to as pro-aggressive behaviour or pro-aggression.

As such, peer victimisation at school can be considered inherently a group process, which can be influenced by characteristics of the context in which it happens. Recent studies, for example, indicate that peer victimisation is less common in school contexts with a higher number of students who defend the victims than in contexts where students are more inclined to engage in pro-aggressive behaviour (Denny et al., Citation2015; Kärnä et al., Citation2010; Menesini et al., Citation2015; Saarento et al., Citation2015; Salmivalli et al., Citation2011; Thornberg & Wänström, Citation2018).

If bystanders have the power to stop or limit peer victimisation, it is important to learn why some students side with the victimisers or remain passive, whereas others stand up for the victims. This is no longer an uncharted area in the research literature. Variability in bystander behaviour has been linked to various types of factors such as attitudes towards bullying (Salmivalli & Voeten, Citation2004) and victims (Rigby & Johnson, Citation2006), empathy (Gini et al., Citation2008; Pozzoli et al., Citation2017) and emotion recognition (Pozzoli et al., Citation2017), efficacy beliefs (Pöyhönen et al., Citation2010), and morality (Thornberg & Jungert, Citation2013). However, most investigations have been confined to individual-level factors (Meter & Card, Citation2015; Salmivalli, Citation2010), even though there has been a recent increasing interest in contextual factors. For instance, reinforcer behaviour has been linked to a higher proportion of boys in the classroom and to a less authoritative classroom climate (Thornberg et al., Citation2018). Outsider behaviour is more common among students who belong to classrooms with lower levels of pro-victim attitudes (Pozzoli et al., Citation2012), and to classrooms with a higher degree of collective moral disengagement (Gini et al., Citation2015). Defending is more common among students who possess high social status in the peer group (Pöyhönen et al., Citation2010) and belong to classrooms characterised by caring, warm, supportive and respectful student-student relationships (Thornberg et al., Citation2017). Nevertheless, the remaining dominance of individual-level factors is likely detrimental to the field because a comprehensive understanding requires attending to the complex social dynamics of peer victimisation (Hong & Espelage, Citation2012; Thomas et al., Citation2018).

Focussing on morality, this article attempted to reduce this gap by examining whether pro-aggressive-, outsider-, and defender behaviour were associated with moral disengagement beliefs, both at the individual and classroom level. The terms peer victimisation and bullying are often used interchangeably in the literature (Noret et al., Citation2018). However, in this study we considered peer victimisation as a broader concept that includes bullying as well as other forms of peer victimisation that does not need to be repeated, intended to harm or carried out in a context of power imbalance (Hunter et al., Citation2007; Noret et al., Citation2018; Turner et al., Citation2015). Because bullying can be considered as a special form of peer victimisation, we relate to the bullying literature as well. In international comparison studies, school bullying rates have been found to be very low in Sweden (Chester et al., Citation2015; Craig et al., Citation2009), but have unfortunately been increasing in recent years, in which 6–8% of the Swedish students reported being bullied in school (Public Health Agency of Sweden, Citation2018). National data on the prevalence of defending and other bystander behaviours in Swedish schools are missing.

Moral disengagement

Students generally consider bullying wrong, a violation of moral rules (Thornberg, Citation2010; Thornberg et al., Citation2016). Still, most students do not intervene on behalf of the victims (O’Connell et al., Citation1999; Salmivalli et al., Citation1998). Acting against one’s moral standards typically brings self-condemnation in the form of discomforting feelings such as guilt or shame (Bandura, Citation1999). However, according to Bandura, there are social and psychological manoeuvres by which such moral self-sanctions can be disengaged from inhumane conduct. In particular, within social cognitive theory, Bandura (Citation1999) describes how people can disengage from their moral standards by (1) reconstructing behaviour; (2) minimising their agentive role; (3) misrepresenting injurious consequences; and (4) blaming or dehumanising the victims (for a detailed review, see Bandura, Citation2016).

Regarding bystander involvement in peer victimisation, empirical findings indicate that children and youth high in moral disengagement are more likely to assist and reinforce peer victimisation (e.g. Pozzoli et al., Citation2012; Thornberg & Jungert, Citation2013), and less likely to defend victims of peer victimisation (e.g. Doramajian & Bukowski, Citation2015; Gini, Citation2006; Obermann, Citation2011). For outsider behaviour, both positive (e.g. Thornberg et al., Citation2017) and negative associations (e.g. Gini, Citation2006) have been found. Accordingly, a recent meta-analysis found a non-significant association between moral disengagement and outsider behaviour (Killer et al., Citation2019). That meta-analysis also supported the negative association between moral disengagement and defending (Killer et al., Citation2019).

Moreover, social cognitive theory emphasises that behaviour is the result of both personal characteristics and the social environment (Bandura, Citation1986). Despite this, research on peer victimisation has primarily investigated moral factors at the individual level (Hymel et al., Citation2010). Students’ behaviour in peer victimisation may vary as a function of group norms, moral atmosphere, and other group processes (e.g. Espelage et al., Citation2003; Gini, Citation2008; Kubiszewski et al., Citation2019; Salmivalli, Citation2010). As far as we know, only a few studies have investigated how bystander behaviours relate to the degree of moral disengagement processes at the collective level. Two of these (Pozzoli et al., Citation2012; Thornberg et al., Citation2017) operationalised collective moral disengagement as the classroom mean of individual moral disengagement (i.e. class moral disengagement). In contrast, and in line with social cognitive theory and its constructs of collective beliefs shared by group members about their group, such as collective efficacy (Bandura, Citation1997) and collective moral disengagement (White et al., Citation2009), Gini et al. (Citation2015) introduced the concept of classroom collective moral disengagement, operationalised as the degree to which moral disengagement is shared by classroom members. Findings suggest that classroom collective moral disengagement (henceforth shortened to collective moral disengagement) is positively associated with peer aggression and outsider behaviour and negatively associated with defender behaviour (Gini et al., Citation2015; Kollerová et al., Citation2018). Furthermore, one study (Allison & Bussey, Citation2017) that focussed on cyber bullying behaviours found that individual moral disengagement was positively associated with cyber defender behaviour at high levels of collective moral disengagement. It should be noted, however, that Allison & Bussey (Citation2017) did not use aggregated scores of the collective moral disengagement scale. Thus, their measure represented individuals’ perception of the degree to which moral disengagement mechanisms are shared by the peers in their classroom. In line with Gini et al. (Citation2015) and Kollerová et al. (Citation2018), the current study conceptualised collective moral disengagement as a group characteristic by aggregating the scores of the participants at the classroom level.

Aims and hypotheses

The aim of the present study was to examine whether pro-aggressive-, outsider-, and defender behaviour were associated with individual and collective moral disengagement. Based on social cognitive theory and the above-discussed empirical evidence, we formulated some hypotheses. First, we hypothesised that both individual and collective moral disengagement were associated with greater pro-aggression, and less defending. We did not specify any hypothesis for the association between individual moral disengagement and outsider behaviour due to mixed findings in previous research. Nevertheless, in line with findings by Gini et al. (Citation2015), we hypothesised collective moral disengagement to be positively associated with outsider behaviour. Furthermore, because social cognitive theory emphasises the interplay between individual and social factors, we hypothesised that cross-level interactions between the individual and classroom-level factors would help explain variability in different bystander behaviours. Thornberg et al. (Citation2017) found that high moral disengagers were more likely to take the outsider role if they belonged to a classroom high in class moral disengagement. Correspondingly, we hypothesised that high moral disengagers who belong to a classroom high in collective moral disengagement would be especially likely to take the outsider role, and possibly also the pro-aggressive role. Other possible cross-level interactions between the correlates were examined in an exploratory fashion.

We also included gender as a control variable. In accordance with previous findings (Pöyhönen et al., Citation2010, Salmivalli & Voeten, Citation2004; Thornberg & Jungert, Citation2013), we expected girls to be more inclined to take the defender role, whereas boys would be more inclined to take the pro-aggressive role. To keep in line with the tenets of social cognitive theory, we also considered the possible role of gender distribution at the group level, by investigating whether the proportion of boys in the classroom contributed to explaining some of the variability in bystander behaviours. For instance, Pozzoli et al. (Citation2012) found higher prevalence of pro-bullying behaviours in classrooms with higher proportions of boys.

Method

Participants

This study is part of an ongoing longitudinal project that investigates social and moral correlates of peer victimisation and bullying among Swedish students from fourth to eighth grade. In this study, we focussed on fifth-grade students because previous research on the relationship between bystander behaviours and moral disengagement has generally focussed on older students (Killer et al., Citation2019). In fifth grade, the original sample consisted of 2534 students from 114 classes in 73 schools. Eight hundred and forty-nine students did not participate, resulting in a participant rate of 66%. We obtained written active parental consent for all participating students. Most of the non-participating students did not participate because they did not get parental consent (the parents did not actively decline participation but simply omitted to respond to the request to participate), whereas a few did not participate because they were absent on the day of data collection. Among the 1685 students who completed the questionnaire, 46 did not complete all the scales used in this study and 62 belonged to mixed-grade classrooms. We excluded students in mixed-grade classrooms because these are atypical in Sweden and would introduce within-classroom age difference as a possible confounder in the study. Thus, the final sample included 1577 students (842 girls, Mage = 11.55 years, SD = 0.33) from 105 classrooms in 64 schools. In terms of gender distribution, there was a small preponderance of girls in the final sample (53%) compared to the original sample (49%). We selected participating schools based on a strategic sampling technique in order to obtain a heterogeneous sample. Thus, our sample included schools in different socio-economic areas (from lower to upper-middle socioeconomic status) and from different socio-geographic locations (from rural areas to mid-size and large cities). Eighty-one percent of the sample, compared with 78% of the whole population (Swedish National Agency for Education Citation2016), had a Swedish ethnic background (i.e. born in Sweden and having at least one Swedish-born parent).

Procedure

Ethical approval before conducting the study was obtained from the Regional Ethical Review Board. Students answered a web-based questionnaire on tablets in their ordinary classroom setting. Either a member of the research team or a teacher was present throughout the session to be able to explain the study procedure and assist participants who needed help (e.g., gave reading support and clarified particular items or words of the questionnaire). The average completion time of the questionnaire was about 30 minutes.

Measures

Bystander behaviours

We used a 15-item 7-point scale (1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree) to measure students’ bystander behaviour (Thornberg et al., Citation2017) but revised to measure bystander in peer victimisation (instead of the narrower context of bullying as in the original scale). Thus, the participants were asked, ‘Try to remember situations in which you have seen one or more students harming another student (for example teasing, mocking, threatening, physically assaulting, or freezing out). What do you usually do?’ Five items depicted pro-aggressive behaviour (e.g. ‘I start to harm the victimised student too’, ‘I encourage those who harm the student by cheering and laughing’, Cronbach’s α = 0.79); five items depicted outsider behaviour (e.g. ‘I just walk away’, Cronbach’s α = 0.80); and five items depicted defender behaviour (e.g. ‘I help the victimised student’, Cronbach’s α = 0.81). As all our response scales were ordered categorical, we consequently used diagonal weighted least squares (DWLS, see Li, Citation2016) robust estimation for estimating the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) models. The CFA supported the three-dimensional solution for the bystander scale in our sample (CFA: χ2(87) = 1026.586, p < .001, CFIrobust = 0.988, RMSEArobust = 0.060; 90% CI [0.057, 0.063]).

Individual moral disengagement in peer victimisation

An 18-item scale was developed in the present study to measure moral disengagement in peer victimisation because previous scales within the scope of children’s and adolescents’ antisocial behaviours were constructed to measure either moral disengagement in antisocial behaviour in general (Bandura et al., Citation1996), or bullying behaviour in particular (e.g. Hymel et al., Citation2005; Thornberg & Jungert, Citation2014). In the current study, we were interested in how inclined students were to morally disengage in peer victimisation. Thus, antisocial behaviour was too broad and bullying too narrow. In line with the situatedness emphasised in social cognitive theory (Bandura, Citation1986, Citation2016), we needed to develop a Moral Disengagement in Peer Victimisation Scale. As stressed by Bandura (Citation2016), ‘(m)oral disengagement is not a dispositional trait that can be assessed by a one-size-fits-all measure. Disengagement mechanisms operate across different aspects of life, but “they are manifested differently depending on the sphere of activity”’ (p. 26).

Our scale comprised all eight moral disengagement mechanisms (Bandura, Citation1999). Students rated each item (e.g. ‘People who get teased don’t really get too sad about it’; ‘Talk badly about someone is okay because he/she wouldn’t notice it’; ‘If my friends begin to tease a classmate, I can’t be blamed for being with them and teasing that person too’; ‘To push or kick someone hard is just about “joking a little” with the person’; ‘It’s okay to tease and freeze out jerks, nerds, and others who are stupid’, ‘If you can’t be like everybody else, it is your own fault if you get bullied or frozen out’) on a seven-point scale (1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree). CFA supported a one-factor structure (CFA: χ2(135) = 1005.319, p<.001, CFIrobust = 0.989, RMSEArobust = 0.045; 90% CI [0.042, 0.048]). Cronbach’s α was 0.87.

Collective moral disengagement in peer victimisation

Students’ beliefs about their collective moral disengagement in peer victimisation were measured through the same items as those measuring individual moral disengagement to avoid the risk of test effects due to different items when comparing individual and collective moral disengagement. However, following the original procedure (Gini et al., Citation2014) to capture the collective dimension of moral disengagement, this scale asked, ‘How many students in your classroom agree with the following?’, and offered five response categories (‘none’, ‘about a quarter’, ‘about half’, ‘about three quarters’, ‘all’). At the individual level, the scale represents individuals’ perception of the degree to which moral disengagement mechanisms are shared by the peers in their classroom. The aggregate score at the classroom level – that is, the average score of all classroom members – constitutes the measure of collective moral disengagement. CFA supported a one-factor structure (CFA: χ2(135) = 1566.292, p < .001, CFIrobust = 0.994, RMSEArobust = 0.053; 90% CI [0.051, 0.056]). Cronbach’s α was 0.93.

Gender and proportion of boys

At the end of the questionnaire, participants indicated their gender. In the analyses, boys were coded 0 and girls were coded 1. The proportion of boys in each class was calculated based on the class lists from the schools.

Statistical analyses

Because the students were nested within classrooms and we were theoretically interested in classroom effects, we analysed the data using multilevel modelling techniques (Bickel, Citation2007). We ran separate multilevel analyses for each of the three bystander roles. For the composite variables (i.e., individual and collective moral disengagement, and the three bystander roles), we used factor scores in order to give more weight to the items with higher loadings. Model 1 included gender and individual moral disengagement (IMD) as predictors. Classroom-level variables proportion of boys (PropBoys) and collective moral disengagement (CMD) were added to model 2, which can be written as:

where

is the response for the ith child in the jth class,

is the intercept for the jth class,

are the slopes for the predictors, and

is the error term for the ith child in the jth class. Finally, we added cross-level interaction terms to model 3. In all models, the intercept was allowed to vary between classes. Additionally, the coefficients of gender and individual moral disengagement were allowed to vary between classes in the third model. Gender and individual moral disengagement were grand mean centred. Proportion of boys and collective moral disengagement were centred around their respective overall means.

Effect sizes were computed as where

is the unstandardised coefficient for variable

is the sample standard deviation for the explanatory variable

and

is the sample standard deviation for the dependent variable. Akaike Information Criterion (Akaike, Citation1974) was used to evaluate whether the more complex models fitted the data better than the simpler ones.

Results

Descriptive statistics and correlations

Descriptive statistics and correlation coefficients of individual and classroom-level variables are presented in and , respectively. We interpreted the significant correlation coefficients based on Cohen (Citation1988), who labelled correlations from 0.1 to 0.29 as weak, from 0.3 to 0.49 as moderate, and from 0.5 as strong. Both individual and collective moral disengagement were moderately to strongly positively correlated with pro-aggressive behaviour, weakly to moderately positively correlated with outsider behaviour, and weakly negatively correlated with defender behaviour. In other words, for all three bystander roles, the pattern of correlations was similar for moral disengagement beliefs at both the individual and collective level. Individual and collective moral disengagement (at the individual level) were, however, not strongly correlated (0.44). Among the bystander roles, pro-aggressive behaviour was weakly positively correlated with outsider behaviour, and weakly to moderately negatively correlated with defender behaviour. Outsider and defender behaviour were moderately negatively correlated. Gender and proportion of boys correlated with several variables, but all correlations were weak. However, proportion of boys was close to reach moderate positive correlations with collective moral disengagement and pro-aggressive behaviour. Thus, a higher proportion of boys was associated with somewhat greater collective moral disengagement and higher prevalence of pro-aggression at the classroom level.

Table 1. Correlations, means, standard deviations, and maximum and minimum observations for individual-level variables.

Table 2. Correlations, means, standard deviations, and maximum and minimum observations for classroom-level variables.

Multilevel analysis: pro-aggressive behaviour

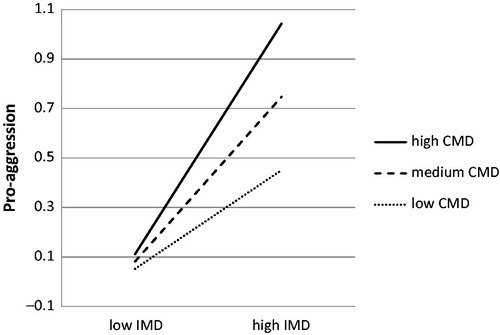

Results from multilevel analysis for pro-aggressive behaviour are summarised in . Six percent of the variance in pro-aggressive behaviour was between classes. In model 1, both individual-level variables gender and individual moral disengagement were significant predictors. Boys and students high in moral disengagement reported being more likely to take the peer victimisers’ side. These effects remained significant in model 2, in which we added the contextual-level variables collective moral disengagement and proportion of boys. Moreover, collective moral disengagement was also a significant predictor in the second model. This indicates that students in classrooms high in collective moral disengagement were more likely to engage in pro-aggressive behaviour. In model 3, to which we added the cross-level interaction terms, only collective moral disengagement remained a significant factor. However, we also found a significant interaction effect between individual and collective moral disengagement. To understand this effect further, we computed simple slopes (Dawson, Citation2014). More specifically, we estimated the relationship between individual moral disengagement and pro-aggression at low (one standard deviation below the mean), medium (the mean), and high (one standard deviation above the mean) levels of collective moral disengagement (). The simple slope for high levels of collective moral disengagement was positive and significant (Bhigh = 0.30, p=.05), whereas the simple slopes for low and medium levels of collective moral disengagement was non-significant (Blow = 0.13, p = 0.36; Bmedium = 0.21, p = .14). In other words, there was a positive association between students’ individual moral disengagement and their pro-aggressive behaviour, but only for those who belonged to classrooms that were high in collective efficacy. AIC decreased significantly from model 1 to model 2, and from model 2 to model 3, supporting the more complex models (see AIC values in ). Effect size calculations revealed that the strongest effect was that of collective moral disengagement.

Figure 1. Individual moral disengagement (IMD) × collective moral disengagement (CMD); (Est =0.31**).

Table 3. Estimates and standard errors from multilevel regression analyses for pro-aggressive behaviour.

Multilevel analysis: outsider behaviour

Results from multilevel analysis for outsider behaviour are summarised in . Nine percent of the variance in outsider behaviour was between classes. In model 1, gender and individual moral disengagement were significant predictors (). Boys and students high in moral disengagement reported being more likely to remain passive when witnessing peer victimisation. These effects were still significant in model 2, where also collective moral disengagement showed up as a significant predictor. Students in classrooms high in collective moral disengagement were more likely to engage in outsider behaviour. In the third model, individual and collective moral disengagement were the only significant predictors. AIC values indicated that the second model was to be preferred over the first one, but that the third model did not further help explain variability in outsider behaviour (see AIC values in ). Effect size calculations revealed that the strongest association was that of individual moral disengagement.

Table 4. Estimates and standard errors from multilevel regression analyses for outsider behaviour.

Multilevel analysis: defender behaviour

Results from multilevel analysis for defender behaviour are summarised in . Six percent of the variance in defender behaviour was between classes. Both gender and individual moral disengagement were significant predictors in model 1 (). Girls and students low in moral disengagement reported being more likely to defend victims of peer victimisation. These effects remained significant in model 2, where we also found a significant negative association for collective moral disengagement, implying that students in classrooms low in collective moral disengagement were more likely to defend victims of peer victimisation. The effects of individual and collective moral disengagement remained significant in the third model, whereas none of the interaction terms proved significant. Neither the AIC value for model 2 nor the AIC value for model 3 decreased significantly, suggesting that the first model is to be preferred over the more complex ones (see AIC values in ). Effect size calculations revealed that the strongest association was that of individual moral disengagement.

Table 5. Estimates and standard errors from multilevel regression analyses for defender behaviour.

Discussion

While we know quite a lot about individual-level correlates of bystander behaviour, we know less about correlates at the classroom level. According to the social cognitive theory, members of a group do not simply operate as autonomous moral agents but are ‘acting together on shared beliefs’ (White et al., Citation2009, p. 43). The current study was, as far as we know, the first to examine simultaneously whether various bystander behaviours in peer victimisation were associated with individual and collective moral disengagement.

In line with our first hypothesis and social cognitive theory, we found pro-aggression to be positively associated with individual and collective moral disengagement, although the main effect of individual moral disengagement disappeared in the final model. Nevertheless, and in line with our second hypothesis, we found a significant interaction effect between individual and collective moral disengagement on pro-aggressive behaviour. High moral disengagers who belonged to classrooms high in collective moral disengagement were particularly likely to side with peer victimisers. Thus, low moral disengagers appear to display a stronger moral agency by being more inclined to resist immoral peer pressure or normative influence to take the perpetrators’ side in peer victimisation, whereas high moral disengagers are more guided by the sociomoral climate among their classmates. This novel finding is highly compatible with social cognitive theory that states that human behaviour is the result of reciprocal interactions among individual factors, the social environment, and behaviours (Bandura, Citation1986). Translated to the context of this study, some of the variability in pro-aggressive behaviour can be explained by moral disengagement beliefs, both at the individual and the classroom level.

We did not put forth hypotheses for any associations between moral disengagement beliefs and outsider behaviour, due to mixed findings in previous research for individual moral disengagement (e.g. Gini, Citation2006; Thornberg et al., Citation2017). However, in the current study we found that moral disengagement, both at the individual and the classroom level, were positively associated with outsider behaviour. The strongest effect size was that of individual moral disengagement. According to social cognitive theory, moral disengagement makes people more inclined to interfere with their moral judgement and deactivating their moral self-sanctions (Bandura, Citation2016). Moral disengagement mechanisms such as diffusion of responsibility, dehumanisation, and blaming the victim at both individual and collective level might influence students to refrain from helping victimised classmates.

In line with our hypothesis and previous research, defender behaviour was negatively associated with both individual moral disengagement (e.g. Gini, Citation2006; Thornberg & Jungert, Citation2013) and collective moral disengagement at the classroom level (Gini et al., Citation2015). Defending victimised peers through confronting the victimisers represents a risky behaviour; the defenders might themselves become targets of peer victimisation. Although many factors are likely to play a part in the decision of standing up for the victim, one important prerequisite is a sense of moral responsibility and feelings of guilt and shame for not doing anything (Pozzoli & Gini, Citation2010). However, whether one defends a victim or not is also dependent on contextual characteristics, such as group norms favouring bullying (Salmivalli & Voeten, Citation2004) and moral disengagement beliefs at the classroom level (Gini et al., Citation2015). Echoing this, we found moral disengagement beliefs at both the individual and the classroom level to be negatively associated with defender behaviour, although individual moral disengagement proved to be the strongest correlate.

Overall, both individual and collective moral disengagement played a significant role in this sample, but with a different strength for the different bystander roles. A possible explanation why collective moral disengagement seems to play a stronger role than individual moral disengagement in pro-aggression, whereas the reverse pattern was found for outsider and defender behaviour, might be that pro-aggression (actively taking perpetrators’ side in peer victimisation) is a more troublesome behaviour and therefore in a stronger need of peer pressure or normative influence rooted in a poor sociomoral climate to take place. Future research should analyse whether this pattern of results is replicated in other samples and further tests of this hypothesis should be carried out more directly, for example by including measures of perceived pressure or of ability to resist peer pressure.

Regarding gender, we found only weak support for our hypotheses that girls are more inclined than boys to take the defender role and that boys would be more inclined than girls to take the pro-aggressive role. Although the correlation analysis showed significant gender effects in line with these hypotheses, the effects were weak and did not remain in the final models of the multilevel analyses. In the same manner, the proportion of boys did not contribute to explaining much of the variability in bystander behaviours.

Limitations and implications

Some limitations of this study should be noted. The probably most serious shortcoming is the cross-sectional nature of our data, which prevents us from drawing causal inferences. Longitudinal and experimental designs could help test these hypotheses on causal relationships. For example, following students nested into classrooms for a longer period and using multiple measurement times to gathering data on individual and collective moral disengagement as well as various bystander behaviours in peer aggression would help us to pinpoint the direction of effects and to examine possible bi-directionalities over time. Furthermore, our data consist of self-reported data. This may have resulted in shared method variance bias. It could also be that the estimates might have been biased due to careless marking, social desirability, and intentionally exaggerated responses (Cornell & Bandyopadhyay, Citation2010). Future research could benefit from combining self-report measures with peer nominations and observer reports (Volk et al., Citation2017). The low participation rate, in particular due to absence of parental consent, is a further limitation in the study as this is vulnerable to selection bias and skewed samples. For instance, research has found that the participation rate is significantly lower in studies using active parental consent and that boys and ethnic minorities are less represented in studies using active parental consent procedure than studies using passive parental consent procedure (for a meta-analysis, see Liu et al., Citation2017). Another limitation is that participants were restricted to fifth-grade Swedish students. It is up to future studies to examine to what degree our findings are generalisable to other age groups and cultural contexts.

Notwithstanding these limitations, the current study adds important insights to the literature of how moral disengagement relates to students’ bystander behaviours, which has potential implications for prevention and intervention work. Although our results did not discern what caused what, it is theoretically sound (Bandura, Citation2016) and empirically suggested (Barchia & Bussey, Citation2011; Doramajian & Bukowski, Citation2015; Hyde et al., Citation2010; Wang et al., Citation2017) that moral disengagement beliefs influence students’ behaviour. Having bystanders act on the behalf of victims, rather than reinforcing or assisting the victimisers, is a promising element in peer victimisation prevention programs (Salmivalli, Citation2014). Programs aimed at increasing bystander intervention have been proven effective, but with small effect sizes for K–8 children (Polanin et al., Citation2012). Therefore, there is a need to find out how these interventions can be improved. The current findings suggest that moral disengagement beliefs both at the individual and at the classroom level might be essential components in such endeavours. It is up to future research to investigate in detail how the findings of the current study can be applied in practice. In general terms, challenging the tendency to morally disengage could steer bystanders away from pro-aggressive and outsider behaviour. Students should be made aware of people’s widespread tendency to morally disengage in a wide range of situations (Bandura, Citation2016), including peer victimisation contexts. Students could be engaged in activities (e.g. discussions, role-play) aimed at increasing their moral engagement in their relationships with peers. Using children’s literature to discuss moral disengagement, raise awareness, and to encourage defending in peer victimisation can decrease moral disengagement and peer victimisation in elementary schools (Wang & Goldberg, Citation2017). Because moral disengagement beliefs operate at both the individual- and the classroom level, such efforts should target not only the individuals involved but also the entire peer group.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Akaike, H. (1974). A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE Transactions on Automatic Control, 19(6), 716–723. https://doi.org/10.1109/TAC.1974.1100705

- Allison, K. R., & Bussey, K. (2017). Individual and collective moral influences on intervention in cyberbullying. Computers in Human Behavior, 74, 7–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.04.019.

- Atlas, R. S., & Pepler, D. J. (1998). Observations of bullying in the classroom. The Journal of Educational Research, 92(2), 86–99. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220679809597580.

- Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Prentice Hall.

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. Freeman and Company.

- Bandura, A. (1999). Moral disengagement in the perpetration of inhumanities. Personality and Social Psychology Review: An Official Journal of the Society for Personality and Social Psychology, Inc., 3(3), 193–209. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr0303_3.

- Bandura, A. (2016). Moral disengagement: How people do harm and live with themselves. Worth.

- Bandura, A., Barbaranelli, C., Caprara, G. V., & Pastorelli, C. (1996). Mechanisms of moral disengagement in the exercise of moral agency. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71(2), 364–374. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.71.2.364.

- Barchia, K., & Bussey, K. (2011). Individual and collective social cognitive influences on peer aggression: Exploring the contribution of aggression efficacy, moral disengagement, and collective efficacy. Aggressive Behavior, 37(2), 107–120. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.20375.

- Bickel, R. (2007). Multilevel analysis for applied research. It’s just regression!. The Guilford Press.

- Chester, K. L., Callaghan, M., Cosma, A., Donnelly, P., Craig, W., Walsh, S., &Molcho, M. (2015). Cross-national time trends in bullying victimization in 33 countries among children aged 11, 13 and 15 from 2002 to 2010. The European Journal of Public Health, 25(suppl 2), 61–64. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckv029.

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. L. Erlbaum Associates.

- Cornell, D. G., & Bandyopadhyay, S. (2010). The assessment of bullying. In S. R. Jimerson, S. M. Swearer, & D. L. Espelage (Eds.), Handbook of bullying in schools: an international perspective (pp. 265–276). Routledge.

- Craig, W., Harel-Fisch, Y., Fogel-Grinvald, H., Dostaler, S., Hetland, J., Simons-Morton, B., Molcho, M., de Mato, M. G., Overpeck, M., Due, P., & Pickett, W. (2009). A cross-national profile of bullying and victimization among adolescents in 40 countries. International Journal of Public Health, 54(S2), 216–224. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-009-5413-9.

- Dawson, J. (2014). Moderation in management research: What, why, when and how. Journal of Business and Psychology, 29(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-013-9308-7.

- Denny, S., Peterson, E. R., Stuart, J., Utter, J., Bullen, P., Fleming, T., Ameratunga, S., Clark, T., & Milfont, T. (2015). Bystander intervention, bullying, and victimization: A multilevel analysis of New Zealand high schools. Journal of School Violence, 14(3), 245–272. https://doi.org/10.1080/15388220.2014.910470.

- Doramajian, C., & Bukowski, W. M. (2015). A longitudinal study of the associations between moral disengagement and active defending versus passive bystanding during bullying situations. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 61(1), 144–172. https://doi.org/10.13110/merrpalmquar1982.61.1.0144.

- Espelage, D. L., Holt, M. K., & Henkel, R. R. (2003). Examination of peer-group contextual effects on aggression during early adolescence. Child Development, 74(1), 205–220. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00531.

- Gini, G. (2006). Social cognition and moral cognition in bullying: What’s wrong? Aggressive Behavior, 32(6), 528–539. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.20153.

- Gini, G. (2008). Italian elementary and middle school students' blaming the victim of bullying and perception of school moral atmosphere. The Elementary School Journal, 108(4), 335–354. https://doi.org/10.1086/528975.

- Gini, G., Albiero, P., Benelli, B., & Altoè, G. (2008). Determinants ofadolescents' active defending and passive bystanding behavior in bullying. Journal of Adolescence, 31(1), 93–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2007.05.002.

- Gini, G., Pozzoli, T., & Bussey, K. (2014). Collective moral disengagement: Initial validation of a scale for adolescents. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 11(3), 386–395. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405629.2013.851024.

- Gini, G., Pozzoli, T., & Bussey, K. (2015). The role of individual and collective moral disengagement in peer aggression and bystanding: A multilevel analysis. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 43(3), 441–452. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-014-9920-7.

- Hanish, L. D., & Guerra, N. G. (2002). A longitudinal analysis of patterns of adjustment following peer victimization. Development and Psychopathology, 14(1), 69–89. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0954579402001049.

- Hong, J. S., & Espelage, D. L. (2012). A review of research on bullying and peer victimization in school: An ecological system analysis. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 17(4), 311–322. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2012.03.003.

- Hunter, S. C., Boyle, J. M., & Warden, D. (2007). Perceptions and correlates ofpeer-victimization and bullying. The British Journal of Educational Psychology, 77(Pt 4), 797–810. https://doi.org/10.1348/000709906X171046.

- Hyde, L. W., Shaw, D. S., & Moilanen, K. L. (2010). Developmental precursors of moral disengagement and the role of moral disengagement in the development of antisocial behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 38(2), 197–209. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-009-9358-5.

- Hymel, S., Rocke-Henderson, N., & Bonnano, R. A. (2005). Moral disengagement: A framework for understanding bullying among adolescents. Journal of Social Sciences, 8, 1–11.

- Hymel, S., Schonert-Reichl, K. A., Bonanno, R. A., Vaillancourt, T., & Rocke-Henderson, N. (2010). Bullying and morality: Understanding how good kids can behave badly. In S. R. Jimerson, S. M. Swearer, & D. L. Espelage (Eds.), Handbook of bullying in schools: An international perspective (pp. 111–128). Routledge.

- Jones, L. M., Mitchell, K. J., & Turner, H. A. (2015). Victim reports of bystander reactions to in-person and online peer harassment: A national survey of adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 44(12), 2308–2320. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-015-0342-9.

- Jungert, T., Piroddi, B., & Thornberg, R. (2016). Early adolescents' motivations to defend victims in school bullying and their perceptions of student-teacher relationships: A self-determination theory approach. Journal of Adolescence, 53, 75–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.09.001.

- Kärnä, A., Voeten, M., Poskiparta, E., & Salmivalli, C. (2010). Vulnerable children in varying classroom contexts: Bystanders' behaviors moderate the effects of risk factors on victimization. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 56(3), 261–282. https://doi.org/10.1353/mpq.0.0052.

- Killer, B., Bussey, K., Hawes, D. J., & Hunt, C. (2019). Ameta-analysis of the relationship between moral disengagement and bullying roles in youth. Aggressive Behavior, 45(4), 450–462. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21833.

- Kollerová, L., Soukup, P., & Gini, G. (2018). Classroom collective moral disengagement scale: validation in Czech adolescents. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 15(2), 184–191. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405629.2017.1292907.

- Kubiszewski, V., Auzoult, L., Potard, C., & Lheureux, F. (2019). Witnessing school bullying: to react or not to react? An insight into perceived social norms regulating self-predicted defending and passive behaviours. Educational Psychology, 39(9), 1174–1193. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2018.1530735.

- Li, C.-H. (2016). The performance of ML, DWLS, and ULS estimation with robust corrections in structural equation models with ordinal variables. Psychological Methods, 21(3), 369–387. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000093.

- Liu, C., Cox, R. B., Washburn, I. J., Croff, J. M., & Crethar, H. C. (2017). The effects of requiring parental consent for research on adolescents’ risk behaviors: A meta-analysis. Journal of Adolescent Health, 61(1), 45–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.01.015.

- Lynn Hawkins, D., Pepler, D. J., & Craig, W. M. (2001). Naturalistic observations of peer interventions in bullying. Social Development, 10(4), 512–527. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9507.00178.

- Menesini, E., Palladino, B. E., & Nocentini, A. (2015). Emotions of moral disengagement, class norms, and bullying in adolescence: A multilevel approach. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 61(1), 124–143. https://doi.org/10.13110/merrpalmquar1982.61.1.0124.

- Meter, D. J., & Card, N. A. (2015). Defenders of victims of peer aggression: Interdependence theory and an exploration of individual, interpersonal, and contextual effects on the defender participant role. Developmental Review, 38, 222–240. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2015.08.001.

- Noret, N., Hunter, S. C., & Rasmussen, S. (2018). The relationship between peer victimization, cognitive appraisals, and adjustment: a systematic review. Journal of School Violence, 17(4), 451–471. https://doi.org/10.1080/15388220.2017.1423492.

- O'Connell, P., Pepler, D., & Craig, W. (1999). Peer involvement in bullying: Insights and challenges for intervention. Journal of Adolescence, 22(4), 437–452. https://doi.org/10.1006/jado.1999.0238.

- Obermann, M.-L. (2011). Moral disengagement among bystanders to school bullying. Journal of School Violence, 10(3), 239–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/15388220.2011.578276.

- Polanin, J. R., Espelage, D. L., & Pigott, T. D. (2012). A meta-analysis of school-based bullying prevention programs' effects on bystander intervention behavior. School Psychology Review, 41(1), 47–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/02796015.2012.12087375

- Pöyhönen, V., Juvonen, J., & Salmivalli, C. (2010). What does it take to stand up for the victim of bullying?: The interplay between personal and social factors. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 56(2), 143–163. https://doi.org/10.1353/mpq.0.0046.

- Pozzoli, T., & Gini, G. (2010). Active defending and passive bystanding behavior in bullying: The role of personal characteristics and perceived peer pressure. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 38(6), 815–827. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-010-9399-9.

- Pozzoli, T., Gini, G., & Altoè, G. (2017). Associations between facial emotion recognition and young adolescents' behaviors in bullying. PLOS One, 12(11), e0188062. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0188062.

- Pozzoli, T., Gini, G., & Vieno, A. (2012). Individual and class moral disengagement in bullying among elementary school children. Aggressive Behavior, 38(5), 378–388. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21442.

- Pozzoli, T., Gini, G., & Thornberg, R. (2017). Getting angry matters: Going beyond perspective taking and empathic concern to understand bystanders' behavior in bullying. Journal of Adolescence, 61, 87–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2017.09.011.

- Public Health Agency of Sweden. (2018). Skolbarns hälsovanor i Sverige 2017/18: Grundrapport [Students’ health habits in the school year of 2017/18]. https://www.folkhalsomyndigheten.se/contentassets/53d5282892014e0fbfb3144d25b49728/skolbarns-halsovanor-2017-18-18065.pdf.

- Reijntjes, A., Kamphuis, J. H., Prinzie, P., & Telch, M. J. (2010). Peer victimization and internalizing problems in children: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Child Abuse &Neglect, 34(4), 244–252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.07.009.

- Rigby, K., & Johnson, B. (2006). Expressed readiness of Australian schoolchildren to act as bystanders in support of children who are being bullied. Educational Psychology, 26(3), 425–440. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410500342047.

- Saarento, S., Boulton, A. J., & Salmivalli, C. (2015). Reducing bullying and victimization:student- and classroom-level mechanisms of change. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 43(1), 61–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-013-9841-x.

- Salmivalli, C. (2010). Bullying and the peer group: A review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 15(2), 112–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2009.08.007

- Salmivalli, C. (2014). Participant roles in bullying: How can peer bystanders be utilized in interventions?Theory into Practice, 53(4), 286–292. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405841.2014.947222.

- Salmivalli, C., Lagerspetz, K., Björkqvist, K., Österman, K., & Kaukiainen, A. (1998). Bullying as a group process: Participant roles and their relations to social status within the group. Aggressive Behavior, 22(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1098-2337(1996)22:1<1::AID-AB1>3.0.CO;2-T.

- Salmivalli, C., & Voeten, M. (2004). Connections between attitudes, group norms, and behaviour in bullying situations. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 28(3), 246–258. https://doi.org/10.1080/01650250344000488.

- Salmivalli, C., Voeten, M., & Poskiparta, E. (2011). Bystanders matter: Associations between reinforcing, defending, and the frequency of bullying behavior in classrooms. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology: The Official Journal for the Society of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, American Psychological Association, Division 53, 40(5), 668–676. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2011.597090.

- Schwartz, D., Gorman, A. H., Nakamoto, J., & Toblin, R. L. (2005). Victimization in the peer group and children's academic functioning. Journal of Educational Psychology, 97(3), 425–435. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.97.3.425.

- Sutton, J., & Smith, P. K. (1999). Bullying as a group process: An adaptation of the participant role approach. Aggressive Behavior, 25(2), 97–111. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1098-2337(1999)25:2<97::AID-AB3>3.0.CO;2-7.

- Swedish National Agency for Education. (2016). Invandringens betydelse för skolresultaten [The influence of immigration on school performance]. Skolverket. https://www.skolverket.se/publikationsserier/aktuella-analyser/2016/invandringens-betydelse-for-skolresultaten.

- Thomas, H. J., Connor, J. P., & Scott, J. G. (2018). Why do children and adolescents bully their peers? A critical review of key theoretical frameworks. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, (5)53, 437–451. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-017-1462-1.

- Thornberg, R. (2010). A study of children’s conceptions of school rules by investigating their judgements of transgressions in the absence of rules. Educational Psychology, 30(5), 583–603. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2010.492348.

- Thornberg, R., & Jungert, T. (2013). Bystander behavior in bullying situations: Basic moral sensitivity, moral disengagement and defender self-efficacy. Journal of Adolescence, 36(3), 475–483. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.02.003.

- Thornberg, R., & Jungert, T. (2014). School bullying and the mechanisms of moral disengagement. Aggressive Behavior, 40(2), 99–108. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21509.

- Thornberg, R., & Wänström, L. (2018). Bullying and its association with altruism toward victims, blaming the victims, and classroom prevalence of bystander behaviors: A multilevel analysis. Social Psychology of Education, (5)21, 1133–1151. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-018-9457-7.

- Thornberg, R., Thornberg, U. B., Alamaa, R., & Daud, N. (2016). Children’s conceptions of bullying and repeated conventional transgressions: Moral, conventional, structuring and personal-choice reasoning. Educational Psychology, 36(1), 95–111. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2014.915929.

- Thornberg, R., Wänström, L., & Jungert, T. (2018). Authoritative classroom climate and its relations to bullying victimization and bystander behaviors. School Psychology International, 39(6), 663–680. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034318809762.

- Thornberg, R., Wänström, L., Hong, J. S., & Espelage, D. L. (2017). Classroom relationship qualities and social-cognitive correlates of defending and passive bystanding in school bullying in Sweden: A multilevel analysis. Journal of School Psychology, 63, 49–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2017.03.002.

- Turner, H. A., Finkelhor, D., Shattuck, A., Hamby, S., & Mitchell, K. (2015). Beyond bullying: Aggravating elements of peer victimization episodes. School Psychology Quarterly, 30(3), 366–384. https://doi.org/10.1037/spq0000058.

- Volk, A. A., Veenstra, R., & Espelage, D. L. (2017). So you want to study bullying? Recommendations to enhance the validity, transparency, and compatibility of bullying research. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 36, 34–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2017.07.003.

- Wang, C., & Goldberg, T. S. (2017). Using children’s literature to decrease moral disengagement and victimization among elementary school students. Psychology in the Schools, 54(9), 918–931. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22042.

- Wang, C., Ryoo, J. H., Swearer, S. M., Turner, R., & Goldberg, T. S. (2017). Longitudinal relationships between bullying and moral disengagement among adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, (6)46, 1304–1317. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-016-0577-0.

- White, J., Bandura, A., & Bero, L. (2009). Moral disengagement in the corporate world. Accountability in Research, 16(1), 41–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/08989620802689847.