Abstract

This study examined the role of support and schoolwork difficulties in the development of school burnout in general upper secondary education students. Students participated the study twice, in the spring of the first year of general upper secondary education (N = 464) and in the spring of the second year (N = 326). Participants completed questionnaires about their burnout as well as support they received and schoolwork difficulties they experienced. The results of path analysis showed that difficulties in learning skills predicted school burnout. Support received in the first year predicted lower school burnout and fewer difficulties in that year; however, neither support in their first nor second years predicted lower burnout in the second year. The implications of these findings are discussed in terms of support and recognising the risks of burnout in general upper secondary education.

Introduction

Schools require students to respond to schoolwork and achievement pressures, increasing demands, competition, or the desire to succeed (De Looze et al., Citation2020). Burnout symptoms are a response to difficulties in coping with these high pressures and demands. School burnout can be considered to be representative of a chronic stress response in students who are initially engaged with their schoolwork but there is a discrepancy between the students’ resources and their own or others’ expectations for their achievements at school (Frydenberg & Lewis, Citation2004; Parker & Salmela-Aro, Citation2011; Salmela-Aro, Kiuru, et al., Citation2009; Salmela-Aro, Savolainen et al., Citation2009). Some research on school burnout and schoolwork difficulties has been published over the past few years (e.g. May et al., Citation2015; Torppa et al., Citation2020), but there is limited information about students whose performance in basic education has been at a high level but who still report schoolwork difficulties in general upper secondary education. There are also few studies pertaining to support in general upper secondary education contexts (e.g. Holopainen & Hakkarainen, Citation2019; Lehto et al., Citation2019). In this study, the participants are general upper secondary education students. Such students are usually considered high-performance students that do not have special needs or need for support. Our aim is to study the development of school burnout in these students and the role of schoolwork difficulties and support.

School burnout

Burnout was originally studied as a work-related disorder (Maslach et al., Citation1996; Ventura et al., Citation2015). School burnout can likely be studied in the same way, as school is a context in which students work (e.g. Rahmati, Citation2015; Shin et al., Citation2011). School burnout is described as a continuous phenomenon from academic stress to major burnout (Salmela-Aro, Kiuru, et al., Citation2009; Salmela-Aro, Savolainen, et al., Citation2009) and can be defined as a concept consisting of three dimensions (Maslach et al., Citation2001; Salmela-Aro, Kiuru, et al., Citation2009; Salmela-Aro, Savolainen et al., Citation2009). The first dimension is exhaustion due to school demands; the second is a cynical attitude towards school, which manifests as a loss of interest in schoolwork and seeing it as not meaningful; and the third dimension refers to students’ feelings of inadequacy (Schaufeli et al., Citation2002; Salmela-Aro & Näätänen, Citation2005). These three dimensions represent the overall construct of school burnout (Salmela-Aro, Kiuru, et al., Citation2009; Salmela-Aro, Savolainen, et al., Citation2009).

The phenomenon of school burnout is constantly increasing, particularly among students in academically demanding educational contexts (e.g. Curran & Hill, Citation2019; De Looze et al., 2020). Prior research in Finnish contexts has shown that students in general upper secondary education (hereafter also ‘academic track’) experience more exhaustion than their peers in vocational education (hereafter also ‘vocational track’) (Salmela-Aro, Kiuru, Nurmi, Citation2008; Salmela-Aro, Kiuru, Pietikäinen, et al., Citation2008). When students make the transition from basic education to academic track, they might experience a more competitive atmosphere than before. Girls have been found to respond more negatively to competitive learning conditions than boys do, and they are also more exposed to stressful life events and more vulnerable to their negative effects (Kessler & McLeod, Citation1984; Salmela-Aro, Kiuru, Nurmi, Citation2008; Salmela-Aro, Kiuru, Pietikäinen, et al., Citation2008). Furthermore, it has been shown that there are differences in school burnout according to gender; burnout is higher among girls than boys (De Looze et al., 2020), and the highest burnout rates are among girls in the academic track (Salmela-Aro & Tynkkynen, Citation2012).

Empirical findings have indicated that school burnout may have several negative consequences, such as difficulties in schoolwork (May et al., 2015) but it has also been found to relate to later and broader problems, such as school dropout, depression, less success in educational pathways, burnout at work, and less satisfaction with life (Salmela-Aro, Citation2017; Tuominen-Soini & Salmela-Aro, Citation2014). Therefore, it is important to study the development of burnout and factors that may affect to it in order to gain a deeper understanding of this phenomenon.

Schoolwork difficulties and support

Students might have difficulties adjusting to the increased academic expectations when transitioning from basic education to the academic track (Berninger et al., Citation2008). Accordingly, different kinds of schoolwork difficulties may occur, such as difficulties in writing essays or taking notes, comprehending more complex texts than in basic education, and studying for exams (Simmons & Singleton, Citation2000). Schoolwork difficulties can be temporary and depend on learning environments, mental or social difficulties, and injuries or sickness. They often overlap (Holopainen et al., Citation2017) and may cause a lack of adequate progress in school (Westwood, Citation2004). Also, one’s grade point average (GPA) is a strong predictor for school dropout and less success in educational pathways (e.g. Battin-Pearson et al., Citation2000; Bowers et al., Citation2013). According to previous findings, lower GPA may also predict higher scores of burnout (Salmela-Aro, Kiuru, Nurmi, Citation2008; Salmela-Aro, Kiuru, Pietikäinen, et al., Citation2008).

Difficulties in schoolwork are associated with school burnout (e.g. Korhonen et al., Citation2014). Previous studies show that there are more depressive symptoms and school-related stress among students with schoolwork difficulties than their peers (e.g. Sideridis, Citation2006; Undheim & Sund, Citation2008). Young adults with schoolwork difficulties often receive negative feedback in their studies despite of their efforts and they may feel overwhelmed because of the expectations by their parents, teachers and peers. Academic failures may be a stress factor and a trigger for depressive reactions (Au et al., Citation2009; Herman et al., Citation2008).

As in many European countries, also in Finland, students follow the same curriculum while in basic education (in Finland, students between the ages of 7–16); afterwards, there is a transition to either the academic track or the vocational track. This is the main educational transition during adolescence and is a very important decision that can affect the level of education that students attain later (Hegna, Citation2014; Hodkinson & Sparkes, Citation1997). According to previous research in Finland, basic education is likely to be less demanding for students who are planning to continue to the academic track. The academic track in Finland is very demanding, however, and may cause a poor fit between the demands of the academic environment and the level of competence for some students (Salmela-Aro, Kiuru, Nurmi, Citation2008; Salmela-Aro, Kiuru, Pietikäinen, et al., Citation2008).

In Finland, students with difficulties at school can receive special educational support for learning from early childhood to upper secondary education. This support is freely available, and students do not need a formal diagnosis to receive it (Finnish National Board of Education, Citation2014; Finnish National Board of Education, Citation2019). In basic education, the most common form of special educational services is part-time special education provided by a special educational teacher during the school day (Hintikka et al., Citation2005). Students may also receive remedial teaching after or before their school day (Finnish National Board of Education, Citation2014). Students in the academic track are also entitled to special educational support for learning. Students with temporary difficulties, injuries, sicknesses, or mental or social difficulties can receive support (Finnish National Board of Education, Citation2019). However, special educational support in the academic track differs from special educational support in basic education. Support in the academic track does not usually teach specific subjects but includes a wide range of activities that enhance students’ learning skills and help them complete their studies despite their special needs. The aim is to guarantee equal opportunity for everyone to graduate from general upper secondary education (Act on General Upper Secondary Education, Citation2018; Finnish National Board of Education, Citation2019).

Special educational support is one form of support available for students in the academic track. In addition, student welfare services offer social and psychological support. Counselling for studies and for vocational selection is provided by guidance counsellors in every school. Previous studies have shown that support provided by a teacher or other school employee has a stronger association with school burnout than peer support or parental support (e.g. Chu et al., Citation2010; Kim et al., Citation2018). Additionally, it has been found that students with a low socio-economic status (SES) trust their teachers less and may feel that teachers do not care about them (see, e.g. Adams & Forsyth, Citation2009). It is important that educational support is easy to access for everyone (Trammell & Hathaway, Citation2007), and receiving support at the right time can help one avoid the negative consequences associated with schoolwork difficulties, such as the mindset that education is useless and has no impact on the student’s future (Willms, Citation2003).

This study

Because only little is known about the development of burnout in the context of general upper secondary education, the aim of this study was to examine the role of schoolwork difficulties and support in the development of school burnout among students in this academic track. We also controlled for the role of gender, socioeconomic status, and school achievement. Three specific research questions were formulated:

Research question 1

What is the amount of schoolwork difficulty, support, and the burnout scores that students reported in the academic track? There have been only few studies regarding support and schoolwork difficulties in the academic track and, as a consequence, no exact hypothesis is set. Based on previous findings showing that students in the academic track experience school burnout more than students in the vocational track (Salmela-Aro & Tynkkynen, Citation2012), we hypothesised that burnout scores are relatively high.

Research question 2

What roles do support and schoolwork difficulties play in the development of school burnout? First, we wanted to examine how does support in the first year of the academic track predict school burnout in the first and second year, and how do schoolwork difficulties in the first year predict school burnout in the first and second year? In addition, we wanted to examine how do burnout and support in the first year predict burnout and support in the second year and how does support in the second year predict school burnout in the second year. Based on previous findings showing that the right time to provide support at school helps avoid the negative consequences of schoolwork difficulties (Willms, Citation2003) and decrease school burnout (Chu et al., Citation2010; Kim et al., Citation2018), and schoolwork difficulties causing more school-related stress (Undheim & Sund, Citation2008), we hypothesised that schoolwork difficulties in the first year would predict school burnout in the first and second year and that support received in the first and second year would predict less burnout in the first and second year, and also less schoolwork difficulties in the first year.

Research question 3

What are the roles of gender, SES, and school achievement in this prediction? It has been found that girls experience more school burnout than boys (De Looze et al., 2020) and boys have more difficulties in learning than girls (Siegel & Smythe, Citation2005). Therefore, it was hypothesised that girls report higher scores of burnout and boys report more schoolwork difficulties. Previous findings show that students with lower SES do not trust their teachers (Adams & Forsyth, Citation2009), and GPA is a strong predictor for educational problems (Battin-Pearson et al., Citation2000; Bowers et al., Citation2013); thus, we hypothesised that students with lower SES experience not receiving the support they need and that students with lower GPAs report more schoolwork difficulties. Lower GPA has also been a predictor for higher burnout scores (Salmela-Aro, Kiuru, Nurmi, Citation2008; Salmela-Aro, Kiuru, Pietikäinen, et al., Citation2008).

Method

Participants and data acquisition

This study is part of a 3-year longitudinal study called ‘Pathway to supported and holistic career counselling in general upper secondary education.’ The first data collection took place in April 2019, when the participants were in the first grade of general upper secondary education (T1, N = 464, age about 16, female = 243, male = 214). The second data collection took place between December 2019 and January 2020 when the same students were in the second grade (T2, N = 326, age about 17, female = 164, male = 157). Students who participated in the study at both times (T1 and T2) were compared with those who participated only at T1. The results indicated no selection effect by GPA (F(1,396) = 0.93, p =.335), gender (χ2 (1) = 1.870, p = .170), or school burnout in the first year (F (1,458) = 1.256, p =.263). By using the missing data procedure (see details when describing the analytical approach) it was possible to supply data for all the participants (N = 464) in the analyses.

Our sample consisted of six upper secondary schools within the area of Eastern Finland. Three of the schools were in urban areas and three in rural areas. The schools in the urban areas were bigger ones (79.2 % of the participated students studied in these schools) and the schools in the rural areas were smaller ones. The intraclass correlations (ICCs) were calculated to determine the proportion of the variance in all variables due to schools. The ICCs were small and close to zero in almost all the variables, from .000 to .005. This indicates only a very small proportion of the variance in these variables was due to schools.

Following the guidelines of the Finnish National Advisory Board on Research Ethics (2009), permission for the project was obtained from school principals and city education leaders. Participating students and their guardians were informed about the study. Students responded anonymously and voluntarily to the internet-based questionnaire. Project coordinators were available to clarify any questions. Filling out the questionnaire took participants between 20 and 60 min.

Measurement

School burnout

Students’ level of school burnout was measured using the School Burnout Scale (BBI-10) (Salmela-Aro & Näätänen, Citation2005), which is a 10-item short version of the Burnout Inventory for Working Life scale (BBI-15) (Näatänen et al., Citation2003). The BBI-10 is a 6-point Likert scale (1 = completely disagree; 6 = completely agree) that assesses students’ school burnout in three dimensions: students’ school-related exhaustion (four items, e.g. ‘I feel overwhelmed by my schoolwork’), cynicism towards the meaning of school (three items, e.g. ‘I feel a lack of motivation in my schoolwork and often think of giving up’), and a sense of inadequacy at school (three items, e.g. ‘I often have feelings of inadequacy in my schoolwork’). It is possible to use either the total sum score for the items or the three separate sum scores (dimensions) in analyses (Salmela-Aro, Kiuru, et al., Citation2009; Salmela-Aro, Savolainen, et al., Citation2009). For the purpose of this study, the sum variables were formed on the basis of the 10 items used to indicate the overall level of burnout rating among students in the academic track; higher scores indicated higher burnout. The scale had good internal consistency, and Cronbach’s alpha reliability for the scale was .895 at time 1 and .886 at time 2.

Self-reported schoolwork difficulties

Self-reported schoolwork difficulties in general upper secondary education (hereafter ‘schoolwork difficulties’) were recorded by a 7-point Likert scale. Students reported how often they experienced difficulties in different kinds of activities during lessons (1 = not at all, 7 = very much). Those activities were ‘Taking notes in classes,’ ‘Making reports,’ ‘Understanding teacher’s instructions,’ ‘Understanding visual material in lessons,’ ‘Getting exams done by the expected time,’ ‘Preparing for the exams,’ ‘Overall understanding about the issues studied,’ ‘Keeping attention during the lessons,’ and ‘Studying mathematics.’ The highest rates of response were found for difficulties in ‘studying mathematics’ (41 % reported difficulties from 4 to 7; i.e. from ‘quite a bit’ to ‘very much’), ‘preparing for exams,’ (37 %) and ‘keeping attention during the lessons’ (29 %). There were some difficulties in ‘overall understanding about the issues studied’ (23 %) and ‘making reports’ (18 %) and fewer difficulties in ‘understanding teachers’ instructions’ (12 %), ‘understanding visual material in lessons’ (10 %), ‘getting exams done by the expected time’ (11 %), and ‘taking notes in classes’ (9 %).

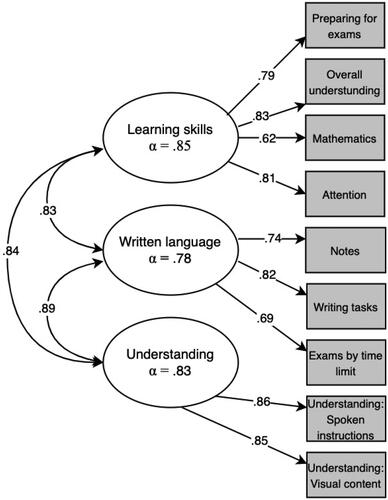

All nine schoolwork difficulties were treated as continuous variables in the analysis. We used exploratory factor analysis (EFA) to examine possible factor structure for students’ self-reported schoolwork difficulties. Three latent variables were formulated based on EFA, and the structures were tested by confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), which fit the data well (χ2=61.450, df =24, a CFI of .975, a TLI of .962, RMSEA of .072, SRMR of .034). As the correlations between factors were strong (see ), we also tested a one-factor solution (χ2 =1351.579, df = 36, a CFI of .923, a TLI of .894, RMSEA of .118, SRMR of .052). The three-factor solution provided a better fit, so we chose that. The factors were named as ‘learning skills’ (SKILLS), ‘written language’ (WRIT), and ‘understanding’ (UND). The three-factor solution is presented in .

Self-reported support for learning

Special educational support in basic education

Students were asked about the special education and remedial teaching they received in basic education in grades 1–9 using a 4-point Likert scale (1 = never, 4 = very often). Based on these variables, two sum variables were formulated and recoded as dichotomous variables: ‘Special educational support in Grades 1 to 6’ (elementary school) and ‘Special educational support in Grades 7 to 9’ (lower secondary school), where 1 = did not receive support and 2 = received support. In elementary school 35 % and in lower secondary school 41 % of students received support. This support in elementary school and lower secondary school is henceforth referred also to as ‘special educational support in basic education’.

Support in the academic track

Students were asked whether they experienced receiving the support they needed in the academic track by a 4-point Likert scale (1 = never, 4 = very often). As this support was not defined as special educational support in the questionnaire, it is possible that students consider support also as a social or psychological support for their studies. In the first year of general upper secondary education, 75 %, and in the second year 73 %, of students reported receiving support often or very often. Only 6 % in the first and second years reported ‘never’ receiving the support they needed. This variable is henceforth referred to as ‘support in the academic track’.

Background variables

SES

In this study, SES was measured by a guardian’s level of education reported by the students (21.8 % of students did not answer this question). Some students only had one guardian while others had two; the highest level of education was used in analysis. There were six options: 1 = general upper secondary education, 2 = vocational education, 3 = university of applied sciences education, 4 = university education, 5 = no further education after basic education, and 6 = I do not know. The variables were recoded into an ordinal variable where 1 = no further education after basic education and 5 = university education. The option ‘I don’t know’ was left out of our analysis. There was a total of 62 % of students who had at least one guardian with higher education (i.e. university of applied sciences education or university education). About 42 % of Finland’s population can be categorised as having higher education (OECD, Citation2020).

Gender

In our analysis of gender, a dichotomous variable was entered (1 = female, 2 = male), while ‘other’ and ‘I don’t want to tell’ were left out of our analysis due to their small number.

School achievement

Students were asked to report their GPA from basic education (16.5 % did not give or remember this information). In a range of 4 (lowest) to 10 (highest), 85 % of students had a GPA of 8.0 or more, while 17 % had a GPA of 9.5 or more; the mean was 8.75.

Analytical approach

First, descriptive statistics were examined, and the strength and directions of relations between school burnout, support, and schoolwork difficulties were studied by Pearson’s correlation. Second, we created a structural equation model which included all the theoretical associations between the study variables by using R version 1.2.5019, Lavaan version 0.5–23 (Rosseel, Citation2012). These associations are as follows: first, special educational support in elementary school and in lower secondary school and special educational support in lower secondary school and support in the academic track; second, special educational support in basic education and schoolwork difficulties in the academic track; third, support and schoolwork difficulties in the first year of the academic track. Then, schoolwork difficulties and school burnout in the first and second year of the academic track and finally, support and school burnout in the first and second years of the academic track.

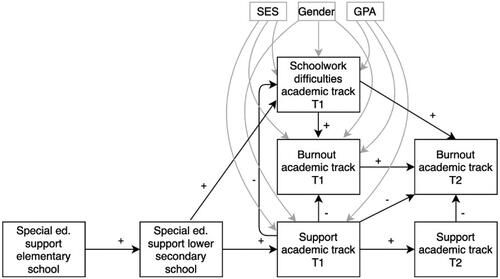

Hypothesised predictors and outcome variables are shown in .

Figure 2. Theoretical model: hypothesied predictors and outcome variables. Note: SES, Gender and GPA were reported at time 1.

For the missing data, we used the standard full information maximum likelihood method (FIML), which utilises all the available data in order to estimate the model without imputing data, thus making use of all of the available observations in the data set when estimating the model. The variables measuring school burnout, schoolwork difficulties, and received support were skewed, so the parameters of the model were estimated using the robust maximum likelihood estimator (MLR). The MLR estimator produced robust standard errors and a Chi-squared test for missing data with non-normal outcomes by means of a sandwich estimator (Muthén & Muthén, Citation1998–2012).

The model fit was evaluated using the following indicators: the Chi-squared test (χ2), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), the standardised root mean square residual (SRMR), the comparative fit index (CFI), and the Tucker Lewis index (TLI). For the RMSEA and SRMR, values under .08 (0.10) were considered an acceptable fit, whereas values under .05 represented an excellent fit to the data (Marsh et al., Citation2005; Schreiber et al., Citation2006). For the CFI and TLI, values of .90 and above were considered to reflect a good fit to the data and values over .95 an excellent fit to the data (Marsh et al., Citation2005; McDonald & Marsh, Citation1990).

Results

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations

The means (M), standard deviations (SD), skewness (Sk), kurtosis (K), and Cronbach’s alphas (α) of observed variables are presented in . The table shows that students’ experiences regarding support they received remained almost the same during their first and second years in the academic track. However, burnout increased and received support decreased a little when transitioning from the first to the second year.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics for the observed variables.

Bivariate correlational patterns were examined to describe the associations between studied variables (school burnout, special educational support in basic education, and support in the academic track) in our main research questions. The correlations are presented in .

Table 2. Bivariate correlations between school burnout and support variables.

Structural model

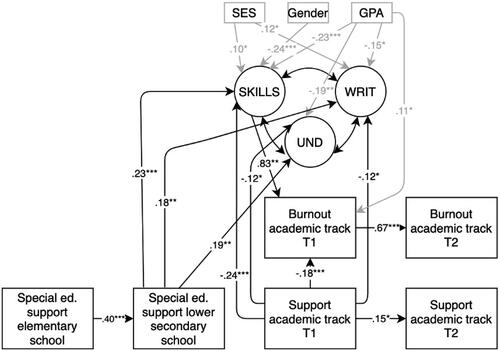

A SEM model was conducted to analyse the associations examined in research question 2 (presented in ). The model fit the data well, with χ2 = 246.516, df = 101, a CFI of .946, a TLI of .921, RMSEA of .059 90% CI (.050, .069), and a SRMR of .048. Only statistically significant paths are reported. shows our final model.

Figure 3. Final model: associations between support, school burnout and schoolwork difficulties. Note: SKILLS = ‘difficulties in learning skills’, WRIT = ‘difficulties in written language’, and UND = ‘difficulties in understanding’. *p<.05; **p < 01; ***p<.001.

For the current data, support received in elementary school predicted support received in lower secondary school (β = .40, t = 8.990, p < .001). However, support received in lower secondary school did not predict support received in the academic track, although it did predict schoolwork difficulties in learning skills (β = .23, t = 4.392, p < .001), written language (β = .18, t = 3.144, p < .01), and understanding (β = .19, t = 3.439, p < .01) in the academic track.

Difficulties in learning skills in the first year of academic track predicted school burnout in the first year (β = .83, t = 5.254, p < .001) but not in the second year. Difficulties in written language and understanding did not predict burnout either in first or second year. Support received in the first year of the academic track was negatively associated with school burnout in the first year; the more support students received, the less they experienced school burnout in the first year (β = −.17, t = −3.641, p < .001) but it was not associated with burnout in the second year. Support received in the first year also had a direct negative association with schoolwork difficulties: learning skills (β = −.23, t = −4.710, p<.001), written language (β = −.12, t = −2.135, p<.05, and understanding (β = −.12, t = −2.211, p < .05). Finally, school burnout in the first grade of the academic track strongly predicted school burnout in the second grade of the academic track (β = .67, t = 11.451, p < .001). Support received in the first year predicted support received in the second year (β = .15, t = 2.213, p < .05), but this had no significant relation to burnout in the second year. Also, support received in the second year had no significant relation to burnout in the second year.

Gender, SES, and GPA were included as covariates when analysing the relations between school burnout, support, and schoolwork difficulties in the first year of the academic track. SES had no statistically significant relation to school burnout or support received in the academic track. It did, however, have a relation to difficulties in learning skills (β = .11, t = 2.090, p < .05) and written language (β = .12, t = 2.134, p < .05). Furthermore, girls experienced more schoolwork difficulties than boys in learning skills (β = −.24, t = −4.754, p < .001) but not in written language or understanding. Also, there were no statistically significant difference in burnout between boys and girls. Higher GPAs were associated with fewer difficulties in all of the studied schoolwork difficulties: learning skills (β = −.23, t = −4.417, p < .001), written language (β = −.15, t = −2.238, p < .05), and understanding (β = −.19, t = −3.117, p < .01). Higher GPAs also indicated higher scores of school burnout (β = .11, t = 2.123, p < .05). Students’ GPAs did not have a direct effect on received support.

Discussion

School-related burnout has continuously increased, especially in high-income countries (De Looze et al., Citation2020). As the literature increasingly emphasises, students experiencing school burnout need educational, psychological, and social support (Kim et al., Citation2018; Lee & Goldstein, Citation2016; Salmela-Aro & Read, Citation2017). The purpose of this study was to examine the role of schoolwork difficulties and support in the development of school burnout in general upper secondary education students.

Our findings indicated first, that special educational support received in elementary school is associated with support in lower secondary school, but this special educational support received in basic education is not associated with support received in the academic track. In this study support in basic education was defined as special educational support, and support in general upper secondary education was defined as either special educational support or any other kind of support students found relevant for their studies. This difference in the definitions might be the reason why special educational support received in basic education is not predicting support received in the academic track. As the academic track in Finland is demanding, an intention to continue studies in the academic track requires good academic achievement in basic education (Salmela-Aro, Kiuru, Nurmi, Citation2008; Salmela-Aro, Kiuru, Pietikäinen, et al., Citation2008). Therefore, it is possible that most of the participants were among the best achievers in their classes in basic education and were not in need of special educational services or other support.

Furthermore, increased academic demands and expectations in general upper secondary education may lead to schoolwork difficulties (Berninger et al., Citation2008) and school-related burnout (e.g. Au et al., Citation2009; Herman et al., Citation2008; Kiuru et al., Citation2011) occurring among students in the academic track. The participants of this study reported that they experienced difficulties especially in learning skills, rather than difficulties in written language and understanding. Participants reported receiving relatively high amount of support at both measurement times and it also showed stability from time 1 to time 2. On the other hand, burnout ratings were also relatively high and showed stability during first and second years of the academic track.

Our findings concerning the predictive associations between support, difficulties and burnout showed, first, that special educational support received in basic education predicted schoolwork difficulties in the academic track so that the more students received special educational support in basic education, the more they reported schoolwork difficulties in the academic track. This finding is understandable because in Finland special education is provided for students with difficulties at school (Finnish National Board of Education, Citation2019) so this finding indicates that students who experience difficulties in the academic track have most likely experienced those already in basic education. Our findings also showed that support students received in the first year of the academic track predicted schoolwork difficulties but so that the more support students reported they received, the less difficulties they experienced. This result is encouraging because it indicates that the support provided in the academic track plays an important role in students’ well-being in terms of their experiences of schoolwork difficulties. This finding is in line with previous studies showing that providing support to students at the right time increases students’ well-being and decreases the negative consequences associated with schoolwork difficulties (Chu et al., Citation2010; Kim et al., Citation2018; Willms, Citation2003).

The results concerning the relations between schoolwork difficulties and burnout showed that factor indicating difficulties in learning skills strongly predicted burnout in the first year of general upper secondary education, whereas the other two factors indicating difficulties in written language and understanding were not statistically significant predictors. These findings are in line with previous studies showing that difficulties in schoolwork are associated with school burnout (e.g. Korhonen et al., Citation2014; Sideridis, Citation2006; Undheim & Sund, Citation2008), but this finding also adds to our previous knowledge about the role of schoolwork difficulties in burnout by showing that it may be some special type of difficulties that play the most important role in terms of school burnout. This study suggests that especially difficulties related to learning skills, such as studying for exams and keeping attention to the study materials, may be these kinds of difficulties. Therefore, it would be important to help students to develop these skills.

Next, the support that students received in the first year predicted their burnout rate in the same year so that the more support they received, the lower burnout scores they reported. This is in line with previous studies showing that support provided by a teacher or other school employee have a strong association with school burnout, and this support is even more important than support from peers or parents (e.g. Chu et al., Citation2010; Kim et al., Citation2018). This finding also indicates that it is possible to promote students’ well-being by providing them with support for their studies and that it is important that educational support is easy to access for everyone (Trammell & Hathaway, Citation2007). In schools’ everyday context teachers and other employee are the natural source of support, and it is important to increase their understanding about how important their support to students can be. It has been suggested that receiving support at the right time can help one avoid the negative consequences associated with schoolwork difficulties, such as the mindset that education is useless and has no impact on the student’s future (Willms, Citation2003).

However, the previous findings apply only in the first school year. The support received in the first year or in the second year did not predict second year’s burnout rating. It seems that support given in the first year is not enough to prevent burnout in the second year, and the amount of support in the second year may also not be enough, which is in line with studies (e.g. Hakkarainen et al., Citation2015) showing that the support received may not be able to stem the negative educational trend that may even lead to dropping out from upper secondary education. It would be important to study the developmental dynamics between schoolwork difficulties, support, and burnout in more details in future studies.

The academic track in Finland is demanding (e.g. Salmela-Aro, Kiuru, Nurmi, Citation2008; Salmela-Aro, Kiuru, Pietikäinen, et al., Citation2008). Students do not graduate for any profession but are expected to continue their studies for several years in higher education (i.e., university or university of applied sciences). Most universities in Finland select their students based on the grades of the Finnish Matriculation Examination, which take place at the final year(s) of the academic track, and competition for enrolment is fierce. This causes competition between students in the academic track and also makes students place higher expectations for themselves, which in turn may lead to a higher risk of burnout (Kessler & McLeod, Citation1984; Salmela-Aro, Kiuru, Nurmi, Citation2008; Salmela-Aro, Kiuru, Pietikäinen, et al., Citation2008). This may also be one of the reasons why the current levels of support are not enough to prevent burnout in the second year. Although the special educational support system in the academic track is not as well-established, as is the case in basic education, it is constantly developing. Support that is readily available for everyone (Trammell & Hathaway, Citation2007), no matter what the reason for this need is, can be crucial for students’ academic well-being.

This study also controlled for the role that gender, SES, or GPA may play in school burnout, schoolwork difficulties, or support in the first year of the academic track. Prior research found that girls experienced more burnout than boys (e.g. De Looze et al., 2020; Salmela-Aro & Tynkkynen, Citation2012), but we did not find any gender differences. It is possible that difficulties in learning skills predicted burnout so strongly that as a consequence gender was not a statistically significant predictor for burnout. Also, it might be possible that the gender differences are related to the way how school burnout is operationalised, that is, gender differences could be more evident when the different dimensions of burnout are studied (e.g., Herrmann et al., Citation2019; Salmela-Aro & Tynkkynen, Citation2012; see also Tang et al., Citation2021). In this study, we examined school burnout as an overall construct.

Girls experienced more schoolwork difficulties in learning skills than boys, although some previous studies have found that boys have more difficulties in learning than girls (Siegel & Smythe, Citation2005). It should be considered that schoolwork difficulties reported in this study are not due to biologically-based learning difficulties but are likely related to academic contexts and increased demands compared to lower school levels. We also found that higher GPAs in basic education indicated less schoolwork difficulties in learning skills, written language, and understanding in the academic track, which is not surprising, while lower GPAs have been a strong predictor for educational problems and school dropout in previous studies (Battin-Pearson et al., Citation2000; Bowers et al., Citation2013). In our study, higher GPAs predicted higher burnout ratings while in some other studies it has been found other way around (Salmela-Aro, Kiuru, Nurmi, Citation2008; Salmela-Aro, Kiuru, Pietikäinen, et al., Citation2008). It might be that well-achieving students in the academic track are very ambitious, set high goals, and tend to perfectionism and, as a consequence, they experience also burnout (see also Ståhlberg et al., Citation2021). This finding deserves attention in future studies.

It has been suggested that students with low SES do not trust their teachers and may feel that teachers do not care about them (e.g., Adams & Forsyth, Citation2009). In our study, SES had no significant association with support provided in the academic track or school burnout, although higher SES indicated more schoolwork difficulties in learning skills and in written language. It is possible that those students report more difficulties because their highly educated parents set high expectations for their children, who may feel as though they are not able to meet those expectations. It should be noted that the number of highly educated guardians was relatively large among the number of participating students in the academic track.

Limitations

This research has some limitations that should be considered. First, the information regarding received support and experienced schoolwork difficulties was reported by students themselves, and we do not have any objective information about students’ schoolwork difficulties in basic education, or information pertaining to the quality of support in the academic track. Second, although the longitudinal research design allowed us to examine the persistence of school burnout and received support in general upper secondary education, we did not have data of school burnout across the transition from basic education to general upper secondary education. Third, even though the sample size was relatively large, the sample was collected from one age group in only one Finnish province, and the study was carried out in the Finnish school system, which must be considered when generalising the findings. Fourth, participants’ response time for the questionnaire varied between 20 and 60 min. It is possible that students who spent more time while responding may have shown reduced concentration for the second part of the questionnaire, and this may have potential effects on responses. Also, the questionnaires of our study were not randomised to avoid order effect. Finally, we understand the limitations of our model and we think that in future research it would be important to examine these studied associations in a more detailed way and also take into account the different dimensions of school burnout.

Conclusion

School environments where academic expectations and competitiveness are very high, combined with individual characteristics such as perfectionism and ambitiousness can lead to an increased risk of school burnout and schoolwork difficulties. This study’s findings about the role of support and schoolwork difficulties in the development of school burnout increase our understanding of why students in the academic track may experience burnout and how they can be supported. These findings highlight the need to recognise the risks for burnout as early as possible and provide students in the academic track with the support they need to graduate on time and continue their studies in higher education.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Hanna Nuutinen and Heli Pesonen for collecting the data presented in this article, and Anne-Mari Souto for leading this longitudinal study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Act on General Upper Secondary Education. ( 2018). (FI) s. 714 (Fin.). https://www.finlex.fi/en/laki/kaannokset/2018/en20180714?search%5Btype%5D=pika&search%5Bkieli%5D%5B0%5D=en&search%5Bpika%5D=General%20Upper%20Secondary%20Education

- Adams, C. M., & Forsyth, P. B. (2009). The Nature and Function of Trust in Schools. Journal of School Leadership, 19(2), 126–152. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/105268460901900201

- Au, R. C. P., Watkins, D., Hattie, J., & Alexander, P. (2009). Reformulating the depression model of learned hopelessness for academic outcomes. Educational Research Review, 4(2), 103–117. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2009.04.001

- Battin-Pearson, S., Newcomb, M. D., Abbott, R. D., Hill, K. G., Catalano, R. F., & Hawkins, J. D. (2000). Predictors of early high school dropout: A test of five theories. Journal of Educational Psychology, 92(3), 568–582. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.92.3.568

- Berninger, V. W., Nielsen, K. H., Abbott, R. D., Wijsman, E., & Raskind, W. (2008). Gender differences in severity of writing and reading disabilities. Journal of School Psychology, 46(2), 151–172. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2007.02.007

- Bowers, A. J., Sprott, R., & Taff, S. A. (2013). Do we know who will drop out? A review of the predictors of dropping out of high school: Precision, sensitivity, and specificity. The High School Journal, 96(2), 77–100. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.7916/D86W9N4X

- Chu, P. S., Saucier, D. A., & Hafner, E. (2010). Meta-analysis of the relationships between social support and well-being in children and adolescents. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 29(6), 624–645. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2010.29.6.624

- Curran, T., & Hill, A. P. (2019). Perfectionism is increasing over time: A meta-analysis of birth cohort differences from 1989 to 2016. Psychological Bulletin, 145(4), 410–429. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000138

- De Looze, M. E., Cosma, A. P., Vollebergh, W. A. M., Duinhof, E. L., de Roos, S. A., van Dorsselaer, S., van Bon-Martens, M. J. H., Vonk, R., & Stevens, G. W. J. M. (2020). Trends over time in adolescent emotional wellbeing in the Netherlands, 2005–2017: Links with perceived schoolwork pressure, parent-adolescent communication and bullying victimization. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 49(10), 2124–2135. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-020-01280-4

- Finnish National Board of Education. (2014). National core curriculum for basic education 2014. Finnish National Board of Education. https://www.oph.fi/sites/default/files/documents/perusopetuksen_opetussuunnitelman_perusteet_2014.pdf

- Finnish National Board of Education. (2019). National core curriculum for general upper secondary schools 2019. Finnish National Board of Education. https://www.oph.fi/sites/default/files/documents/lukion_opetussuunnitelman_perusteet_2019.pdf

- Frydenberg, E., & Lewis, R. (2004). Adolescents least able to cope: How do they respond to their stresses? British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 32(1), 25–37. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03069880310001648094

- Hakkarainen, A. M., Holopainen, L. K., & Savolainen, H. K. (2015). A five-year follow-up on the role of educational support in preventing dropout from upper secondary education in Finland. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 48(4), 408–421. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0022219413507603

- Hegna, K. (2014). Changing educational aspirations in the choice of and transition to post-compulsory schooling—a three-wave longitudinal study of Oslo youth. Journal of Youth Studies, 17(5), 592–613. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2013.853870

- Herman, K. C., Lambert, S. F., Reinke, W. M., & Ialongo, N. S. (2008). Low academic competence in first grade as a risk factor for depressive cognitions and symptoms in middle school. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 55(3), 400–410. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012654

- Herrmann, J., Koeppen, K., & Kessels, U. (2019). Do girls take school too seriously? Investigating gender differences in school burnout from a self-worth perspective. Learning and Individual Differences, 69, 150–161. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2018.11.011

- Hintikka, S., Aro, M., & Lyytinen, H. (2005). Computerized training of the correspondences between phonological and orthographic units. Written Language and Literacy, 8(2), 155–178. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1075/wll.8.2.07hin

- Hodkinson, P., & Sparkes, A. C. (1997). Careership: A sociological theory of career decision making. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 18(1), 29–44. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/0142569970180102

- Holopainen, L., & Hakkarainen, A. (2019). Longitudinal effects of reading and/or mathematical difficulties: The role of special education in graduation from upper secondary education. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 52(6), 456–467. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0022219419865485

- Holopainen, L., Taipale, A., & Savolainen, H. (2017). Implications of overlapping difficulties in mathematics and reading on self-concept and academic achievement. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 64(1), 88–103. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1034912X.2016.1181257

- Kessler, R. C., & McLeod, J. D. (1984). Sex differences in vulnerability to undesirable life events. American Sociological Review, 49(5), 620–631. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/2095420

- Kim, B., Jee, S., Lee, J., An, S., & Lee, S. M. (2018). Relationships between social support and student burnout: A meta-analytic approach. Stress and Health: Journal of the International Society for the Investigation of Stress, 34(1), 127–134. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.2771

- Kiuru, N., Leskinen, E., Nurmi, J.-E., & Salmela-Aro, K. (2011). Depressive symptoms during adolescence: Do learning difficulties matter? International Journal of Behavioral Development, 35(4), 298–306. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025410396764

- Korhonen, J., Linnanmäki, K., & Aunio, P. (2014). Learning difficulties, academic well-being, and educational dropout: A person-centred approach. Learning and Individual Differences, 31, 1–10. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2013.12.011

- Lee, C. Y. S., & Goldstein, S. E. (2016). Loneliness, stress, and social support in young adulthood: Does the source of support matter? Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 45(3), 568–580. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-015-0395-9

- Lehto, J. E., Kortesoja, L., & Partonen, T. (2019). School burnout and sleep in Finnish secondary school students. Sleep Science (Sao Paulo, Brazil), 12(1), 10–14. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5935/1984-0063.20190051

- Marsh, H. W., Hau, K. T., & Grayson, D. (2005). Goodness of fit in structural equation models. In A. Maydeu-Olivares & J. J. McArdle (Eds.), Contemporary psychometrics: A festschrift for Roderick P. McDonald (pp. 275–340). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

- Maslach, C., Jackson, S. E., & Leiter, M. P. (1996). Maslach burnout inventory manual (3rd ed.). Consulting Psychologists Press.

- Maslach, C., Schaufeli, W. B., & Leiter, M. P. (2001). Job burnout. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 397–422. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.397

- May, R. W., Bauer, K. N., & Fincham, F. D. (2015). School burnout: Diminished academic and cognitive performance. Learning and Individual Differences, 42, 126–131. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2015.07.015

- McDonald, R. P., & Marsh, H. W. (1990). Choosing a multivariate model: Noncentrality and goodness of fit. Psychological Bulletin, 107(2), 247–255. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.247

- Muthén, L. K., & Muthén B. O. (1998–2012). Mplus user’s guide: Statistical analysis with latent variables (7th ed.). Muthén & Muthén. http://www.statmodel.com/index2.html

- Näatänen, P., Aro, A., Matthiesen, S., & Salmela-Aro, K (2003). Bergen burnout indicator 15. Edita.

- OECD. (2020). Education at a glance 2020: OECD indicators. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1787/69096873-en.

- Parker, P. D., & Salmela-Aro, K. (2011). Developmental processes in school burnout: A comparison of major developmental models. Learning and Individual Differences, 21(2), 244–248. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2011.01.005

- Rahmati, Z. (2015). The study of academic burnout in students with high and low level of self-efficacy. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 171, 49–55. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.01.087

- Rosseel, Y. (2012). Lavaan: An R Package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48(2), 1–36. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v048.i02

- Salmela-Aro, K. (2017). Dark and bright sides of thriving—school burnout and engagement in the Finnish context. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 14(3), 337–349. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/17405629.2016.1207517

- Salmela-Aro, K., & Näätänen, P. (2005). Nuorten koulu-uupumusmittari BBI-10 [Adolescents’ School Burnout Inventory]. Edita.

- Salmela-Aro, K., & Read, S. (2017). Study engagement and burnout profiles among Finnish higher education students. Burnout Research, 7, 21–28. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.burn.2017.11.001

- Salmela-Aro, K., & Tynkkynen, L. (2012). Gendered pathways in school burnout among adolescents. Journal of Adolescence, 35(4), 929–939. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2012.01.001

- Salmela-Aro, K., Kiuru, N., & Nurmi, J.-E. (2008). The role of educational track in adolescents’ school burnout: A longitudinal study. The British Journal of Educational Psychology, 78(Pt 4), 663–689. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1348/000709908X281628

- Salmela-Aro, K., Kiuru, N., Leskinen, E., & Nurmi, J. E. (2009). School burnout inventory: Reliability and validity. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 25(1), 48–57. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759.25.1.48

- Salmela-Aro, K., Kiuru, N., Pietikäinen, M., & Jokela, J. (2008). Does school matter? The role of school context in adolescents’ school-related burnout. European Psychologist, 13(1), 12–23. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040.13.1.12

- Salmela-Aro, K., Savolainen, H., & Holopainen, L. (2009). Depressive symptoms and school burnout during adolescence: Evidence from two cross-lagged longitudinal studies. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38(10), 1316–1327. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-008-9334-3

- Schaufeli, W., Martínez, I., Pinto, A., Salanova, M., & Bakker, A. (2002). Burnout and engagement in university students: A cross-national Study. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 33(5), 464–481. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022102033005003

- Schreiber, J. B., Nora, A., Stage, F. K., Barlow, E. A., & King, J. (2006). Reporting structural equation modeling and confirmatory factor analysis results: A review. The Journal of Educational Research, 99(6), 323–338. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3200/JOER.99.6.323-338

- Shin, H. J., Kim, B. Y., Lee, M. Y., Noh, H. K., Kim, K. H., & Lee, S. M. (2011). A short-term longitudinal study of mental health and academic burnout among middle school students. The Korean Journal of School Psychology, 8(2), 133–152. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.16983/kjsp.2011.8.2.133

- Sideridis, G. D. (2006). Understanding low achievement and depression in children with learning disabilities: A goal orientation approach. International Review of Research in Mental Retardation, 31, 163–203. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/s0074-7750(05)31005-6

- Siegel, L. S., & Smythe, I. S. (2005). Reflections on research on reading disability with special attention to gender issues. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 38(5), 473–477. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/00222194050380050901

- Simmons, F., & Singleton, C. (2000). The reading comprehension abilities of dyslexic students in higher education. Dyslexia, 6(3), 178–192. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/1099-0909(200007/09)6:3<178::AID-DYS171>3.0.CO;2-9

- Ståhlberg, J., Tuominen, H., Pulkka, A., & Niemivirta, M. (2021). Students perfectionistic profiles: Stability, change, and associations with achievement goal orientations. Psychology in the Schools, 58(1), 162–184. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22444

- Tang, X., Upadyaya, K., & Salmela-Aro, K. (2021). School burnout and psychosocial problems among adolescents: Grit as a resilience factor. Journal of Adolescence, 86, 77–89. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2020.12.002

- Torppa, M., Vasalampi, K., Eklund, K., Sulkunen, S., & Niemi, P. (2020). Reading comprehension difficulty is often distinct from difficulty in reading fluency and accompanied with problems in motivation and school well-being. Educational Psychology, 40(1), 62–81. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2019.1670334

- Trammell, J., & Hathaway, M. (2007). Help-seeking patterns in college students with disabilities. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 20(1), 5–15.

- Tuominen-Soini, H., & Salmela-Aro, K. (2014). Schoolwork engagement and burnout among Finnish high school students and young adults: Profiles, progressions, and educational outcomes. Developmental Psychology, 50(3), 649–662. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033898

- Undheim, A., & Sund, A. (2008). Psychosocial factors and reading difficulties: Students with reading difficulties drawn from a representative population sample. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 49(4), 377–384. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9450.2008.00661.x

- Ventura, M., Salanova, M., & Llorens, S. (2015). Professional self-efficacy as a predictor of burnout and engagement: The role of challenge and hindrance demands. The Journal of Psychology, 149(3–4), 277–302. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2013.876380

- Westwood, P. (2004). Learning and learning difficulties: A handbook for teachers. Australian Council for Educational Research.

- Willms, J. D. (2003). Student engagement at school. A sense of belonging and participation: Results from PISA 2000. Organisation for economic co-operation and development. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1787/19963777