?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This study examined whether individual and collective moral disengagement (MD) in seventh grade were associated with bullying perpetration across seventh and eighth grade, and whether changes in individual and collective MD from seventh to eighth grade were associated with concomitant changes in individual-level bullying perpetration. In this short-term longitudinal study, 1232 students from 96 lower secondary classrooms answered a web-based questionnaire on tablets during school, once in seventh grade and once in eighth grade. According to the findings, and in line with the study’s hypotheses, students who scored higher in individual MD in seventh grade and students who belonged to classrooms with higher levels of collective MD in seventh grade were more inclined to engage in bullying perpetration across seventh and eighth grade. In addition, students who increased in individual MD or belonged to classrooms that increased in collective MD from seventh to eighth grade reported increased levels of bullying perpetration. In contrast, students who decreased in individual MD and who belonged to classrooms that decreased in collective MD declined in their levels of bullying perpetration from seventh to eighth grade.

Introduction

School bullying, commonly defined as aggressive, inhumane, or offensive behaviour that is repeated over time and directed towards a student who is less powerful in relation to the perpetrator(s) (Smith & O’Higgins Norman, Citation2021), is a problem worldwide (Cosma et al., Citation2020), and is on the rise in Sweden (Bjereld et al., Citation2020; Friends, Citation2022) where the present study was conducted. Bullying has harmful consequences as, beyond the immediate suffering it causes, it puts the victim at a higher risk of mental, psychosomatic, and physical health problems and poor academic achievement (Chouhy et al., Citation2017; Fry et al., Citation2018; Gini & Pozzoli, Citation2013; Moore et al., Citation2017; Schoeler et al., Citation2018).

From an ethical perspective, bullying is an unfair and immoral behaviour that violates societal norms, human rights, including children’s rights, and moral conceptions (Gutzwiller-Helfenfinger & Perren, Citation2022; Romera et al., Citation2019). In line with this, schoolchildren recognise bullying as a severe moral transgression by referring to the harm it causes the victim (Thornberg, Citation2010; Thornberg et al., Citation2017). Even those who report that they bully others make this moral judgement, although they tend to consider it as less severe than their peers (Thornberg et al., Citation2017). Therefore, the presence of bullying in school represents a gap between moral standards and actions among students: How can they engage in bullying when they, in general, condemn such behaviour and understand that bullying is seriously wrong and harms victims? Within his social-cognitive theoretical framework, Bandura (Citation1999, Citation2016) proposes the concept of moral disengagement to explain and empirically investigate how people are able to violate moral standards and still live with themselves.

Moral Disengagement

Moral disengagement (MD) refers to social-cognitive processes that distort moral cognition and deactivate moral self-regulation, and thus interfere with self-monitoring and self-evaluation, and disengage moral self-sanctions. This means that people can engage in immoral behaviours—such as harming others—without feelings of guilt, shame, or remorse through a set of self-serving social-cognitive distortions. Examples of such distortions include justifying inhumane actions by referring to worthy ends or moral purposes; euphemistically labelling the immoral behaviour in a way that makes it sounds less wrong and more acceptable; detaching oneself from personal responsibility through placing it on others; perceptually minimising, ignoring, or disputing the harmful consequences of the immoral behaviour; and dehumanising and blaming the victim (Bandura, Citation1999, Citation2016).

A large number of studies have shown a positive association between MD and bullying perpetration among children and adolescents, but the vast majority of these studies have been cross-sectional (for meta-analyses, see Gini et al., Citation2014; Killer et al., Citation2019). There is, however, a small but growing body of longitudinal studies that have found that MD predicts bullying perpetration (Georgiou et al., Citation2022; Obermann, Citation2013; Thornberg, Wänström, Pozzoli, et al., 2019; Wang et al., Citation2017), at least at the between-person level (Romera et al., Citation2021), and that change in MD is positively linked to change in bullying perpetration over time (Bjärehed, Citation2022; Thornberg, Wänström, & Hymel, Citation2019). In a longitudinal study on verbal bullying, students with higher average levels of MD engaged more in verbal bullying in general and increased this behaviour more over time, compared to students with lower levels of average MD (Bjärehed et al., Citation2021b). However, the current study is the first study to examine whether change in MD is associated with change in bullying perpetration over time among lower secondary school students.

Developmental trajectories of MD—driven by the interplay of personal, behavioural, and environmental influences (the so-called ‘triadic codetermination’, see Bandura, Citation2018)—create individual differences in how inclined students in a certain age are to morally disengage in peer aggression and bullying situations. Their individual proneness to MD is dynamic and changeable due to this ongoing triadic codetermination (Bandura, Citation2016). With reference to social-cognitive theory (Bandura, Citation2016) and previous empirical longitudinal studies (e.g. Obermann, Citation2013; Thornberg, Wänström, & Hymel, Citation2019), we therefore hypothesised that change in MD is positively associated with change in bullying perpetration among students over time. Considering that there are still few longitudinal studies, further research should test and replicate the longitudinal association with different samples, but also include other variables in the same models, particularly contextual factors, because, as Bandura (Citation2016) puts it, “morality is not solely an intrapsychic matter but is deeply embedded in human relationships” (p. 26). To increase the understanding of school bullying from a social-cognitive framework, we need to know more about social contexts, such as the classroom context in schools, and examine how they are related to bullying perpetration.

Collective moral disengagement

According to social-cognitive theory (Bandura, Citation2016) and social-ecological theory (Bronfenbrenner, Citation1979), student behaviour and development are not just a matter of individual characteristics but are produced in an interplay between individual and contextual factors, where classroom and school contexts play essential roles in school bullying (Hong & Espelage, Citation2012; Saarento et al., Citation2015). In addition, group socialisation theory states that when students are organised into groups (e.g. classroom units of peers), group processes and dynamics will emerge and affect said students. In these social processes, group members tend to become more similar over time. Therefore, group membership and peer socialisation in classroom-based peer ecology play a significant role in students’ development and behaviour, including bullying perpetration (Hymel et al., Citation2015).

Gutzwiller-Helfenfinger and Perren (Citation2022) propose a social-ecological model of bullying and morality, in which they state that when new classrooms are established, their sociomoral climate and culture will develop over time. A possible interplay between increased bullying and passive and pro-bullying bystander behaviours (i.e. socially accepting, approving of or reinforcing bullying) and decreased morality and defending behaviour in the classroom peer group might result in a bullying dynamic that evolves over time, in which bullying and MD become increasingly normative, widespread, and intense. It means that bullying becomes “the normal, expected, tolerated, or even accepted way to treat weaker peers in the classroom and school context” (Gutzwiller-Helfenfinger & Perren, Citation2022, p. 441). Thus, MD operates not only at the individual level but also on the classroom level (Gini et al., Citation2015), as a part of an increasingly toxic and dysfunctional sociomoral classroom.

While almost all studies on MD and bullying have been investigated at the individual level (Killer et al., Citation2019), it has been proposed that MD can operate at individual and collective levels (Bandura, Citation2016; White et al., Citation2009). Collective MD refers to MD beliefs that are shared within a group as a “group-level property arising from interactive, coordinative, and synergistic group dynamics” (Bandura, Citation2016, p. 100). According to Gini et al. (Citation2015), “collective moral disengagement includes the same mechanisms as individual moral disengagement, but it refers to the beliefs in justifying negative actions that are—to some extent—shared within a significant social group” (p. 387). It is a group characteristic that differs between groups in terms of how widespread and shared MD mechanisms are perceived to be in the group by its members, as a result of their group processes and social interaction patterns. Therefore, individual MD and collective MD can both influence individual behaviours like bullying perpetration.

Gini et al. (Citation2015) suggested two main reasons for studying collective MD at the classroom level when examining peer aggression such as school bullying. First, the vast majority of peer aggression and bullying incidents in school take place among classmates, showing that the social influences at the classroom level are particularly pervasive. Second, the classroom unit of students is the most significant social context in a student’s everyday school life, as they spend most of their school time in this group. The power of social influences is affected by proximity and frequency of social interactions and contacts (Bronfenbrenner, Citation1979).

A few past studies have demonstrated that classroom collective MD—in other words, collective MD at the classroom level—is associated with peer aggression (Gini et al., Citation2015, Citation2022), bullying perpetration (Bjärehed, Citation2022; Bjärehed et al., Citation2021a; Kollerová et al., Citation2018; Thornberg, Wänström, & Hymel, Citation2019; Thornberg et al., Citation2021), bullying victimisation (Kollerová et al., Citation2018; Thornberg et al., Citation2021), and siding with the perpetrator(s) when witnessing peer victimisation (Sjögren et al., Citation2021). Only three of these studies included longitudinal analyses. Thornberg, Wänström, and Hymel (Citation2019) found that while classroom collective MD in fourth grade was associated with bullying perpetration across fourth and fifth grade, change in classroom collective MD was not linked to change in bullying perpetration from fourth to fifth grade. The same pattern was then found in Bjärehed’s (Citation2022) study regarding traditional school bullying perpetration; but from fifth grade to sixth grade. However, change in classroom collective MD was related to change in cyberbullying perpetration. In Gini et al.’s (Citation2022) study, classroom collective MD in the first semester of school predicted both reactive and proactive aggression in the second semester within a school year. Of interest to the present study, only two of these three studies examined the longitudinal link between classroom collective MD and bullying perpetration (Bjärehed, Citation2022; Thornberg, Wänström, & Hymel, Citation2019).

Studies on classroom collective MD have been conducted in three countries: Italy, Czechia, and Sweden. In the Italian studies (Gini et al., Citation2015, Citation2022), students were in middle and high schools. In the Italian school setting, “students stay in a single classroom with the same group of peers every day for the whole school year, irrespective of the subject to be taught” (Gini et al., Citation2022, p. 529). Therefore, the classroom units of students represented very stable social contexts in these two studies. In the Czech study (Kollerová et al., Citation2018), students were recruited from elementary schools, which indicates that the classroom unit of students in their study represented a stable social context as well. In the Swedish studies (Bjärehed, Citation2022; Bjärehed et al., Citation2021a; Thornberg, Wänström, & Hymel, Citation2019; Thornberg et al., Citation2021), participants attended upper elementary school. In Sweden, elementary school students stay in their classroom unit of peers every school day, with very few exceptions.

In contrast, the sample in the current study consisted of students from lower secondary schools in Sweden. Although they still belong to a main classroom unit of peers where they spend most of their time (like in elementary school), they are also part of other units of peer clustering due to individually-elected school subjects (e.g. different third language classes). Furthermore, while upper elementary school students have few teachers, lower secondary school students have many specialised subject teachers. Due to these differences between the two school levels—in which the main classroom unit of peers become a less stable social context and students’ relationships with teachers weakens in the latter—there is a need to examine whether classroom collective MD is associated with bullying perpetration in lower secondary school.

In addition, the transition to lower secondary school represents a developmental change from middle childhood or pre-adolescence to adolescence in the Swedish school context. Adolescence is a distinct developmental period where peer influence increases in impact while students become more independent from their parents and other adults (Laursen & Veenstra, Citation2021; Smetana et al., Citation2014). Thus, the peer context of the classroom might therefore become more influential in students’ socialisation, development, and behaviour in lower secondary school than in elementary school. The current study was the first study to examine whether initial level of classroom collective MD was associated with bullying perpetration, and whether change in classroom collective MD was associated with change in bullying perpetration over time among lower secondary school students.

The present study

The aim of the present study was to examine whether individual and collective MD were associated with bullying perpetration. More specifically, we examined whether individual and collective MD in seventh grade were associated with bullying perpetration across seventh and eighth grade, and whether changes in individual and collective MD from seventh to eighth grade were associated with concomitant changes in bullying perpetration.

Deduced from social-cognitive theory and previous research, we hypothesised that individual and collective MD would be positively associated with bullying perpetration. Furthermore, we hypothesised that (a) individual and collective MD in seventh grade would be associated with bullying perpetration across seventh and eighth grades, (b) change in individual MD would be linked to change in bullying perpetration over time, and (c) change in collective MD would be linked to change in bullying perpetration over time. The associations in hypotheses (a) and (b) were found in Thornberg, Wänström, and Hymel’s (2019) and Bjärehed’s (Citation2022) longitudinal studies, with younger students in upper elementary classrooms. In our study, we tested whether their findings could be replicated in the current sample of lower secondary school students. While Thornberg, Wänström, and Hymel’s (2019) and Bjärehed’s (Citation2022) findings did not confirm the hypothesis that change in collective MD is associated with change in bullying perpetration over time, we retained that hypothesis as a deduction from the social-cognitive theory on individual and collective MD (Bandura, Citation2016), and from developmental research revealing that peer influence has a much stronger impact on students in adolescence (Laursen & Veenstra, Citation2021; Smetana et al., Citation2014). We expected that an increase in collective MD would be linked to an increase in bullying perpetration, while a decrease in collective MD would be linked to a decrease in bullying perpetration over time.

Gender and immigrant background were included in the present study as control variables. Boys have been found to be more inclined to engage in bullying perpetration than girls (Cook et al., Citation2010; Mitsopoulou & Giovazolias, Citation2015), while research on the link between ethnicity or immigrant background and bullying perpetration have been inconsistent (for a review, see Xu et al., Citation2020), and non-significant in a meta-analysis (Vitoroulis & Vaillancourt, Citation2018). However, since the associations between these demographic variables and bullying perpetration vary across studies and across cultural and local contexts, including them as co-variables is adequate.

Method

Participants

The present study was part of a longitudinal project investigating social and moral correlates of bullying among school students in Sweden. In seventh grade, the original sample consisted of 3,372 students from 141 classrooms in 44 schools. However, 1,379 students did not obtain parental consent; 245 students were absent on the day of data collection or chose not to participate; and 11 students did not complete all questionnaires used in the present study. Out of these 1,737 students, 1,336 students completed all the scales in eighth grade as well. Finally, because we were interested in investigating associations of classroom-level variables of collective MD, we excluded students in classrooms with a low participation rate (i.e. below 30%), resulting in a final sample of 1,232 students from 96 classrooms (53% girls, mean age7th grade = 13.63, SD7th grade = 0.35, mean age8th grade = 14.59, SD8th grade = 0.34). For attrition analyses, we tested whether students who continued their participation from seventh to eighth grade differed from those who dropped out from the study after seventh grade in their levels of individual MD, collective MD, and bullying perpetration in seventh grade. Independent t tests revealed that there was no group difference in how students rated their classroom collective MD, but that students who dropped out from the study displayed higher levels of individual MD (t = 2.94, p = .003, Mcontinuers = 1.55, Mdropouts = 1.70) and bullying perpetration (t = 2.05, p = .041, Mcontinuers = 1.19, Mdropouts = 1.26) in seventh grade. The significant differences were, however, small (dindividual MD = 0.19, dbullying perpetration = 0.15, see Cohen, Citation1988).

We did not collect socioeconomic data at the individual level, but based on a strategic sampling of schools, the sample of the current study included students from different socio-geographic locations (from rural areas to mid-size and large cities) and socioeconomic backgrounds (from lower to upper-middle socioeconomic statuses). Twenty percent had an immigrant background defined as not being born in Sweden or as having two foreign-born parents (compared to the national average of 25%–26% during the academic years of data collection; Swedish National Agency for Education, Citation2022).

Procedure

School principals and teachers were informed about the study and granted access to the classrooms. Both written informed parental consent and student assent were obtained from all participants. Participating students answered a web-based questionnaire on tablets during school; once in seventh grade and once in eighth grade. Either a member of the research team or a teacher was present throughout the session to explain the study procedure and assist participants. Before filling out the questionnaire, all participants received standardised instructions and were assured that their participation was confidential and voluntary, and that they could withdraw at any time without having to disclose any reason for doing so. The average completion time of the questionnaire was about 20–30 minutes.

Measures

Individual moral Disengagement

To assess students’ levels of individual MD in peer victimisation situations, we used an 18-item scale (Bjärehed et al., Citation2021a). The scale asked participants to rate the extent to which they agreed (1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree) with each of the items (e.g. “People who get teased don’t really get too sad about it”; “Talk badly about someone is okay because he/she wouldn’t notice it”; “If you can’t be like everybody else, it is your own fault if you get bullied or frozen out”). Altogether, the 18 items covered the four loci of MD (Bandura, Citation2016). Because we were interested in students’ overall tendency to morally disengage, we created a composite scale constituted by the mean score of all items for every student. The scale was found to be internally consistent (Cronbach’s α of 0.92 in seventh grade and 0.95 in eighth grade).

Collective moral Disengagement

To assess students’ levels of collective MD in peer victimisation situations, we used a scale containing the same 18 items as the ones in the individual MD scale. However, to capture the collective dimension of MD (see Gini et al., Citation2014), the scale asked, “How many students in your classroom agree with the following?” and offered the following five-point response scale: “none”, “about a quarter”, “about half”, “about three quarters”, “all” (see also Bjärehed et al., Citation2021a). The Swedish word that was used for “classroom” in the scale was “klass” and refers to students’ main classroom unit of peers, which they belong to through the whole lower secondary school in Sweden. To obtain collective MD at the classroom level, we computed each individual’s mean score and then aggregated the average score of all classroom members. The scale was found to be internally consistent, with Cronbach’s α of 0.94 in seventh grade and 0.96 in eighth grade.

Bullying perpetration

To assess bullying perpetration, we used an 11-item self-report scale that did not mention the word bullying in order to reduce the risk of underreporting and misconceptions about what constitutes bullying (Bjärehed et al., Citation2020). The scale asked, “Think of the past 3 months: how often have you done the following things at school to one or more students who are less strong, less popular, or less powerful than you?” The question was followed by 11 behavioural items: three depicting verbal bullying (e.g. “teased the student and called him/her mean names”); three depicting relational bullying (e.g. “spread mean rumors or lies about him/her”); and five depicting physical bullying (e.g. “hit or kicked the student to hurt him/her”). We created a composite scale by averaging the mean score of all items for every student. The scale was found to be internally consistent (Cronbach’s α of 0.91 in seventh grade and 0.93 in eighth grade).

Statistical analyses

To investigate the aim of this study, we used a three-level regression model with bullying perpetration as the dependent variable, carried out in four model steps, estimated using the nmle package (version 3.1-157) in RStudio (version 2022.07.2). Measurement occasions (seventh and eighth grade) constituted the first level, students formed the second level, and classrooms made up the third level. The levels were hierarchical, in that measurement occasions were nested within students, and students were nested within classrooms.

The first model included grade as its only predictor. The intercept of the first model corresponds to the average bullying perpetration score in seventh grade, whereas the slope represents the average change in bullying perpetration from seventh to eighth grade. The second model added the second level predictors of gender, immigrant background, and individual MD in seventh grade (IMDt1). The second model allowed for assessing the effects of students’ initial levels of individual MD on the subsequent levels of bullying perpetration; controlling for gender and immigrant background. The third model further added the classroom level predictor of collective MD in seventh grade (CMDt1). In the fourth and last model, two cross-level interaction variables were added: the student-level change in individual MD (Grade x IMDt2 - IMDt1), and the classroom-level change in collective MD (Grade x CMDt2 - CMDt1) from seventh to eighth grade. The fourth model allowed for an assessment of the effects of changes in MD at the student level, and of changes in collective MD at the classroom level on changes in bullying perpetration, controlling for initial levels of individual- and classroom-level predictors. In models 1–3, the intercept was allowed to vary across classrooms and across students within classrooms. In the fourth model, the time slope (grade) was allowed to vary across individuals and across classrooms. IMDt1 and the change variable of individual MD were centred around the grand mean of all students. CMDt1 and the change variable of collective MD were centred around the grand mean of all classrooms.

Each model was evaluated towards the less complex preceding model by investigating Deviance (-2LL). A significantly smaller Deviance would suggest that the new, more complex, model should be preferred over the preceding model. The parameters and standard errors of the models were estimated using restricted maximum-likelihood (REML), whereas the Deviance measure was calculated based on the maximum likelihood (ML) estimation (see Bickel, 2007). Furthermore, beyond determining whether the variables of the models were significant, we also evaluated the strength of the significant associations. These effect sizes were computed as where

is the unstandardised coefficient for variable

is the sample standard deviation for the explanatory variable

and

is the sample standard deviation for the dependent variable.

Results

Descriptive statistics and correlations

presents descriptive statistics and pairwise correlations (both within and between time points) among the individual level variables. The average levels of individual MD, student perceived collective MD and bullying perpetration increased slightly from seventh to eighth grade. Furthermore, all correlations were significant at the .001 level. We interpreted the significant correlations from 0.1 to 0.29 as weak, from 0.3 to 0.49 as moderate, and 0.5 and above as strong (Cohen, Citation1988). Individual MD at Time 1 correlated moderately with individual MD at Time 2, and bullying perpetration at Time 1 correlated moderately with bullying perpetration at Time 2. Individual MD and bullying perpetration were strongly correlated within time points and moderately correlated between time points.

Table 1. Inter-correlations, means, and standard deviations for individual-level MD, student perceived collective MD, and bullying perpetration.

Because the classroom-level collective MD scores were computed as the mean of all individual scores within a classroom, we included student-perceived collective MD in the correlation matrix among the individual variables (). Student-perceived collective MD at Time 1 correlated moderately with student-perceived collective MD at Time 2. Individual MD and student-perceived collective MD were moderately correlated within timepoints. Individual MD at Time 1 correlated moderately with student-perceived collective MD at Time 2, and student-perceived collective MD at Time 1 correlated weakly with individual MD at Time 2. Student-perceived collective MD and bullying perpetration were moderately correlated within timepoints. Student-perceived collective MD at Time 1 correlated weakly with bullying perpetration at Time 2, and bullying perpetration at Time 1 correlated moderately with student-perceived collective MD at Time 2.

presents descriptive statistics and pairwise correlations, both within and between time points, among the classroom-level variables. The average levels of collective MD and bullying perpetration at the classroom level were stable from seventh to eighth grade. All correlations were significant at the .001 level. Collective MD at Time 1 correlated strongly with collective MD at Time 2, and bullying at Time 1 were strongly correlated with bullying at Time 2. Collective MD and bullying perpetration were moderately correlated, both within and between time points.

Table 2. Inter-correlations, means, and standard deviations for classroom-level collective MD and bullying perpetration.

Multilevel analyses

Results from the multilevel analyses are summarised in . The intraclass correlation (ICC) for the empty model, without any predictor variables, was .05, indicating that 5% of the total variance in bullying perpetration was between classes. In the first model, grade was not significantly associated with bullying perpetration, which suggests that there was no average change in the levels of bullying perpetration from seventh to eighth grade. Next, individual MD along with the control variables of gender and immigrant background were added in the second model. The Deviance measure decreased significantly (χ2(3) = 569, p < .001), thus indicating that the second model is preferred over the first model. Initial levels of individual MD were significantly positively associated with bullying perpetration (Est = 0.24, p < .001, effect size = 0.45), while controlling for gender and immigrant background. The classroom level predictor of collective MD was added to the third model, which constituted an improvement to the second model (χ2(1) = 22, p < .001). In the third model, initial levels of both individual (Est = 0.23, p < .001, effect size = 0.43) and collective (Est = 0.17, p < .001, effect size = 0.24) MD were significantly associated with bullying perpetration.

Table 3. Estimates and standard errors from multilevel regression analyses for bullying perpetration.

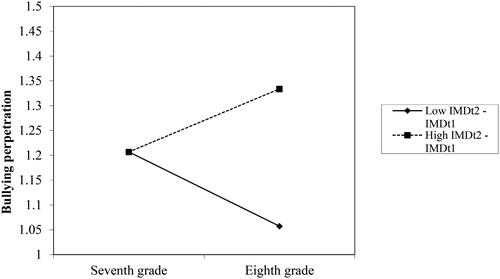

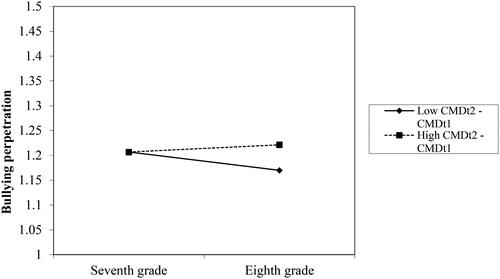

Addition of the cross-level interaction variables student-level change in individual MD (Grade x IMDt2 - IMDt1) and the classroom-level change in collective MD (Grade × CMDt2 − CMDt1) continued to improve the model (χ2(6) = 392, p < .001). In this model, the positive associations of the initial levels of individual (Est = 0.28, p < .001, effect size = 0.53) and collective (Est = 0.17, p < .001, effect size = 0.24) MD remained. In addition, both change variables were significantly positively associated with bullying perpetration (Est = 0.21, p < .001, effect size = 0.36 for Grade x IMDt2 − IMDt1 and Est = 0.06, p = .002, effect size = 0.02 for Grade × CMDt2 − CMDt1). To interpret these significant interaction effects, we computed simple slopes (Dawson, Citation2014) and plotted the interactions (see and ). The simple slope for students with high values (i.e. one standard deviation above the mean) on IMDt2–IMDt1 was 0.13 (p < .001), and the simple slope for students with low values (i.e. one standard deviation below the mean) on IMDt2–IMDt1 was −0.15 (p < .001). The simple slope for students with high values (i.e. one standard deviation above the mean) on CMDt2–CMDt1 was 0.01 (p = .214) and the simple slope for students with low values (i.e. one standard deviation below the mean) on CMDt2–CMDt1 was −0.04 (p < .001). Thus, students who decreased in individual MD and students who belong to classrooms which decreased in collective MD declined in their levels of bullying perpetration from seventh to eighth grade. Furthermore, students who increased in individual MD from seventh to eighth grade reported increasing levels of bullying perpetration.

Discussion

Although a large body of research has examined and shown that individual MD is positively linked with bullying perpetration among children and adolescents (Gini et al., Citation2014; Killer et al., Citation2019), fewer studies have investigated this association longitudinally and whether collective MD at the classroom level is related to bullying perpetration. According to the few past studies, individual MD predicts bullying perpetration over time (e.g. Georgiou et al., Citation2022; Obermann, Citation2013), at least when making comparisons between students (Romera et al., Citation2021), and studies in elementary schools have shown that change in individual MD is associated with concomitant change in bullying perpetration (Bjärehed, Citation2022; Thornberg, Wänström, & Hymel, Citation2019). Our study contributes to the current literature by demonstrating that the positive relationship between change in individual MD and change in bullying perpetration could be found in secondary schools as well. In fact, higher levels of MD in seventh grade were associated with higher levels of bullying perpetration across seventh and eighth grade, and increase in MD across these grades was related to increase in bullying perpetration. In contrast, students with lower initial levels of MD were less inclined to bully others across the two grades, and students who decrease in MD tended to decrease in bullying behaviour as well.

Furthermore, MD is theoretically conceptualised as moral distortions that can emerge at both individual and collective levels (Bandura, Citation2016), and thus, be a part of the school or classroom climate, but previous research on collective MD and bullying is scarce (e.g. Kollerová et al., Citation2018; Thornberg et al., Citation2021). Still, only two previous studies have examined the longitudinal association between classroom collective MD and bullying (Bjärehed, Citation2022; Thornberg, Wänström, & Hymel, Citation2019). These two studies included children in upper elementary school. In contrast, the present study is, to the best of our knowledge, the first to examine whether both individual MD and classroom collective MD are longitudinally associated with bullying perpetration among adolescents in lower secondary school. While change in classroom collective MD was not linked with change in bullying among the younger students in previous findings (Bjärehed, Citation2022; Thornberg, Wänström, & Hymel, Citation2019), this link was significant among adolescent students in the present study. Our findings showed that higher levels of classroom collective MD in seventh grade were associated with higher levels of bullying perpetration across seventh and eighth grades. In contrast, in classrooms where collective MD was low in seventh grade, bullying perpetration tended to be less prevalent across the two grades; and in classrooms where the collective MD decreased over time, bullying perpetration tended to decrease, as well.

A possible explanation as to why change in classroom collective MD was not linked with change in bullying perpetration in elementary school (Bjärehed, Citation2022; Thornberg, Wänström, & Hymel, Citation2019) but was linked in secondary school in the current findings might be that peer influence regarding moral distortions becomes stronger in adolescence as compared to middle childhood. Thus, social-cognitive theory of MD (Bandura, Citation1999, Citation2016) contributes to explaining bullying perpetration in school, and classroom collective MD appears to play a stronger role with increasing age. Research has shown that adolescence is a special developmental period where peers become an increasingly important context for adolescent socialisation (Smetana et al., Citation2014), and where peer relationships and adolescent culture increase in impact in general (Laursen & Veenstra, Citation2021). As Farrell et al. (Citation2017), put it, “Peers are among the most salient influences on an individual’s behavior during the transition from childhood to adolescence” (p. 1351).

The positive link between change in classroom collective MD and change in bullying perpetration over time in the current study supports Gutzwiller-Helfenfinger and Perren’s (Citation2022) proposed social-ecological model of bullying and morality, which describes how the bullying dynamic can evolve over time while both bullying and MD become more and more normative, widespread, and intense. In the cycle of bullying, the sociomoral classroom culture become more toxic and dysfunctional. The increase in collective MD at the classroom level, together with the increase of MD at the individual level normalises, justifies, and reinforces bullying perpetration. According to social-cognitive theory, higher levels of classroom collective MD undermine students’ moral agency in the classroom (Bandura, Citation2016; Gini et al., Citation2014). If a growing number of peers are bullying the victim as the classroom collective MD increases, it would further strengthen the classroom collective MD and peer socialisation (cf., Hymel et al., Citation2015) to bully, side with the bullies, or to at least not to take the victim’s side. A high or increasing prevalence of bullying should make collective MD that supports and justifies the bullying more visible and salient in the classroom peer group. In this way, a collective cycle of bullying might be constituted, where collective MD and bullying in the peer context of the classroom mutually affect and reinforce each other over time. The present study found a reverse process: A decrease in classroom collective MD was linked with a decrease in bullying perpetration.

Limitations and implications

Despite the strength of a longitudinal design in the current study, one limitation is that the analysed time period was only one year with two waves; one in seventh grade and one in eighth grade. Longitudinal approaches that extend across several years of the school system, and include additional waves or measurement timepoints, would have allowed for a more extensive inquiry into developmental changes and trajectories, and a more detailed examination of the longitudinal interplay of individual MD, classroom collective MD, and bullying behaviour. However, in the transition from upper elementary school to lower secondary school in Sweden, students are usually re-grouped into new classroom units, which makes it impossible to follow the same classroom units through this transition. In some other countries, the possibility to follow intact classroom units across school years and levels is even more limited. Nonetheless, future longitudinal studies on MD and bullying that run throughout early childhood and into late adolescence would increase the understanding of how MD and bullying are linked to each other over time, and how this process contributes to explain students’ social and moral development, as well as the prevalence of bullying in different grades and levels of school.

Another limitation is the self-report measures of individual MD and bullying perpetration, which are vulnerable to social desirability, perception and recall biases, as well as to careless filling in and shared or common method bias. Regarding collective MD, students reported their subjective views of their classroom group, which are vulnerable to perception and recall biases and careless marking. For instance, while some students might have overestimated their peers’ degree of MD, other students might have underestimated this. Although there is a conceptual and measurement overlap between individual and collective MD—they consist of the same mechanisms—there is also a clear distinction that is well-grounded in social-cognitive theory (Bandura, Citation2016). While individual MD refers to people’s own individual moral distortions, collective MD refers to group members’ collective perception of how widespread MD is in their group. The same list of items has been used in both scales to minimise the risk of test effects compared to if we had used different item wordings when assessing individual and collective MD.

Because only 5% of the total variance in bullying perpetration was between classrooms, the link between classroom collective MD and bullying perpetration in the current findings might be underestimated. Future studies relying on samples with larger between-classroom variations in bullying perpetration are therefore needed to further examine this link. Moreover, due to the delimited focus on individual MD, classroom collective MD and bullying, together with gender and immigrant background as covariates, other possible variables at the individual and classroom levels that might function as moderators or mediators have been overlooked in the study. Future longitudinal studies should include a number of individual and contextual variables to investigate the complexity of the process over time. Finally, the non-probability sampling procedure delimited to students in Sweden limits the generalisability of the findings. Therefore, the present study needs to be replicated in other countries and cultural contexts.

Despite these limitations, the current study demonstrates a changeability of individual and classroom collective MD over time, and how these changes were related to students’ changes in bullying perpetration. Considering that both the initial levels and the changes over time in individual and classroom collective MD were associated with bullying, the longitudinal findings underscore that anti-bullying programs should develop components designed to decrease and counteract MD; both as an individual phenomenon and as classroom group characteristic. Thus, there is a need to raise students’ awareness of MD mechanisms such as moral justification, euphemistic labelling, diffusion of responsibility, distortion of consequences, dehumanisation, and victim blaming, and to encourage and give students the opportunity to reflect on the potentially harmful effects of these mechanisms. Teachers’ efforts in increasing students’ empathy may also be important, because empathy has been linked to less MD among students (Kokkinos & Kipritsi, Citation2018).

In the school context, students may learn to internalise and use but also to condemn and reject MD mechanisms, depending on the classroom peer climate and teachers’ efforts in influencing collective beliefs among students. According to the current findings, low levels and decreases of classroom collective MD decrease the risk of bullying. Thus, the possible presence of collective MD must be considered and addressed when working with and evaluating classroom climate, school climate, school safety, and students’ social-emotional learning. With reference to our results, we argue that teachers’ classroom management and social-emotional instructional support should be considered major bullying prevention in everyday classroom practice (also see Ertesvåg & Roland, Citation2015; Roland & Galloway, Citation2002). A recent study (Collie, Citation2022) demonstrated that teachers’ social-emotional instructional support was related to student perceived social-emotional competence, which in turn was linked to fewer conduct problems and greater prosocial behaviour and emotional well-being. Our findings add to the significance of promoting social-emotional learning by emphasising that teachers must target and promote students’ moral agency and the whole moral atmosphere of the classroom as a part of their classroom management, and social-emotional instructional support to counteract bullying.

Author contributions

RT conceptualised the research idea, designed the study, and applied for the ethical approval. PE, SE, TÖ and BR contributed to the collection of data. BJ conducted the data analysis. RT wrote the main part of the draft while BJ wrote the result section. RT and BJ completed the entire article. PE, SE, TÖ and BR reviewed and approved the final version. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bandura, A. (1999). Moral disengagement in the perpetration of inhumanities. Personality and Social Psychology Review: An Official Journal of the Society for Personality and Social Psychology, Inc, 3(3), 193–209. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr0303_3

- Bandura, A. (2016). Moral disengagement: How people do harm and live with themselves. Worth.

- Bandura, A. (2018). Toward a psychology of human agency: Pathways and reflections. Perspectives on Psychological Science: a Journal of the Association for Psychological Science, 13(2), 130–136. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691617699280

- Bjärehed, M. (2022). Individual and classroom collective moral disengagement in offline and online bullying: A short-term multilevel growth model study. Psychology in the Schools, 59(2), 356–375. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22612

- Bjärehed, M., Thornberg, R., Wänström, L., & Gini, G. (2020). Mechanisms of moral disengagement and their associations with indirect bullying, direct bullying, and pro-aggressive bystander behavior. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 40(1), 28–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431618824745

- Bjärehed, M., Thornberg, R., Wänström, L., & Gini, G. (2021a). Individual moral disengagement and bullying among Swedish fifth graders: The role of collective moral disengagement and pro-bullying behavior within classrooms. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(17–18), NP9576–NP9600. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260519860889

- Bjärehed, M., Thornberg, R., Wänström, L., & Gini, G. (2021b). Moral disengagement and verbal bullying in early adolescence: A three-year longitudinal study. Journal of School Psychology, 84, 63–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2020.08.006

- Bjereld, Y., Augustine, L., & Thornberg, R. (2020). Measuring the prevalence of peer bullying victimization: Review of studies from Sweden during 1993–2017. Children and Youth Services Review, 119, 105528. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105528

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human developments: Experiment by nature and design. Harvard University Press.

- Chouhy, C., Madero-Hernandez, A., & Turanovic, J. J. (2017). The extent, nature, and consequences of school victimization: A review of surveys and recent research. Victims & Offenders, 12(6), 823–844. https://doi.org/10.1080/15564886.2017.1307296

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. L. Erlbaum Associates.

- Collie, R. J. (2022). Instructional support, perceived social-emotional competence, and students’ behavioral and emotional well-being outcomes. Educational Psychology, 42(1), 4–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2021.1994127

- Cook, C. R., Williams, K. R., Guerra, N. G., Kim, T. E., & Sadek, S. (2010). Predictors of bullying and victimization in childhood and adolescence: A meta-analytic investigation. School Psychology Quarterly, 25(2), 65–83. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020149

- Cosma, A., Walsh, S. D., Chester, K. L., Callaghan, M., Molcho, M., Craig, W., & Pickett, W. (2020). Bullying victimization: Time trends and the overlap between traditional and cyberbullying across countries in Europe and North America. International Journal of Public Health, 65(1), 75–85. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-019-01320-2

- Dawson, J. (2014). Moderation in management research: What, why, when and how. Journal of Business and Psychology, 29(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-013-9308-7

- Ertesvåg, S. K., & Roland, E. (2015). Professional cultures and rates of bullying. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 26(2), 195–214. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2014.944547

- Farrell, A. D., Thompson, E. L., & Mehari, K. R. (2017). Dimensions of peer influences and their relationship to adolescents’ aggression, other problem behaviors and prosocial behavior. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 46(6), 1351–1369. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-016-0601-4

- Friends. (2022). Mobbningens förekomst: Tre barn utsatta i varje klass [The prevalence of bullying: Three children are target in each class]. https://friends.se/uploads/2022/05/Mobbningens_forekomst-compressed.pdf

- Fry, D., Fang, X., Elliott, S., Casey, T., Zheng, X., Li, J., Florian, L., & McCluskey, G. (2018). The relationships between violence in childhood and educational outcomes: A global systematic review and meta-analysis. Child Abuse & Neglect, 75, 6–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.06.021

- Georgiou, S. N., Charalampous, K., & Stavrinides, P. (2022). Moral disengagement and bullying at school: Is there a gender issue? International Journal of School & Educational Psychology, 10(3), 395–407. https://doi.org/10.1080/21683603.2020.1859421

- Gini, G., & Pozzoli, T. (2013). Bullied children and psychosomatic problems: A meta-analysis. Pediatrics, 132(4), 720–729. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2013-0614

- Gini, G., Pozzoli, T., & Bussey, K. (2015). The role of individual and collective moral disengagement in peer aggression and bystanding: A multilevel analysis. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 43(3), 441–452. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-014-9920-7

- Gini, G., Pozzoli, T., & Hymel, S. (2014). Moral disengagement among children and youth: A meta-analytic review of links to aggressive behavior. Aggressive Behavior, 40(1), 56–68. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21502

- Gini, G., Thornberg, R., Bussey, K., Angelini, F., & Pozzoli, T. (2022). Longitudinal links of individual and collective morality with adolescents’ peer aggression. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 51(3), 524–539. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-021-01518-9

- Gutzwiller-Helfenfinger, E., & Perren, S. (2022). The moral dimension of bullying at school: A social-ecological process perspective. In M. Killen & J. G. Smetana (Eds.), Handbook of moral development. (3rd ed., pp. 437–453). Routledge.

- Hong, J. S., & Espelage, D. L. (2012). A review of research on bullying and peer victimization in school: An ecological system analysis. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 17(4), 311–322. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2012.03.003

- Hymel, S., McClure, R., Miller, M., Shumka, E., & Trach, J. (2015). Addressing school bullying: Insights from theories of group processes. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 37, 16–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2014.11.008

- Killer, B., Bussey, K., Hawes, D. J., & Hunt, C. (2019). A meta-analysis of the relationship between moral disengagement and bullying roles in youth. Aggressive Behavior, 45(4), 450–462. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21833

- Kokkinos, C. M., & Kipritsi, E. (2018). Bullying, moral disengagement and empathy: Exploring the links among early adolescents. Educational Psychology, 38(4), 535–552. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2017.1363376

- Kollerová, L., Soukup, P., & Gini, G. (2018). Classroom collective moral disengagement scale: Validation in Czech adolescents. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 15(2), 184–191. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405629.2017.1292907

- Laursen, B., & Veenstra, R. (2021). Toward understanding the functions of peer influence: A summary and synthesis of recent empirical research. Journal of Research on Adolescence: The Official Journal of the Society for Research on Adolescence, 31(4), 889–907. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12606

- Mitsopoulou, E., & Giovazolias, T. (2015). Personality traits, empathy and bullying behavior: A meta-analytic approach. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 21, 61–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2015.01.007

- Moore, S. E., Norman, R. E., Suetani, S., Thomas, H. J., Sly, P. D., & Scott, J. G. (2017). Consequences of bullying victimization in childhood and adolescence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World Journal of Psychiatry, 7(1), 60–76. https://doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v7.i1.60

- Obermann, M.-L. (2013). Temporal aspects of moral disengagement in school bullying? Crystallization or escalation? Journal of School Violence, 12(2), 193–210. https://doi.org/10.1080/15388220.2013.766133

- Roland, E., & Galloway, D. (2002). Classroom influences on bullying. Educational Research, 44(3), 299–312. https://doi.org/10.1080/0013188022000031597

- Romera, E. M., Casas, J. A., Gómez-Ortiz, O., & Ortega-Ruiz, R. (2019). Moral domain as a risk and protective factor against bullying: An integrating perspective review on the complexity of morality. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 45, 75–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2018.07.005

- Romera, E. M., Ortega-Ruiz, R., Runions, K., & Camacho, A. (2021). Bullying perpetration, moral disengagement and need for popularity: Examining reciprocal associations in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 50(10), 2021–2035. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-021-01482-4

- Saarento, S., Garandeau, C. F., & Salmivalli, C. (2015). Classroom- and school-level contributions to bullying and victimization: A review. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 25(3), 204–218. https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.2207

- Schoeler, T., Duncan, L., Cecil, C. M., Ploubidis, G. B., & Pingault, J.-B. (2018). Quasi-experimental evidence on short- and long-term consequences of bullying victimization: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 144(12), 1229–1246. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000171

- Sjögren, B., Thornberg, R., Wänström, L., & Gini, G. (2021). Associations between students’ bystander behavior and individual and classroom collective moral disengagement. Educational Psychology, 41(3), 264–281. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2020.1828832

- Smetana, J. G., Robinson, J., & Rote, W. M. (2014). Socialization in adolescence. In J. E. Grusec, & P. D. Hastings (Eds.), Handbook of socialization: Theory and research (2nd ed., pp. 60–84). Guilford.

- Smith, P. K., & O’Higgins Norman, J. (Eds.). (2021). The Wiley Blackwell handbook of bullying: A comprehensive and international review of research and intervention. Wiley Blackwell.

- Swedish National Agency for Education. (2022). Sök statistik [Search statistics]. https://www.skolverket.se/skolutveckling/statistik/sok-statistik-om-forskola-skola-ochvuxenutbildning?sok=SokA

- Thornberg, R. (2010). A study of children’s conceptions of school rules by investigating their judgments of transgressions in the absence of rules. Educational Psychology, 30(5), 583–603. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2010.492348

- Thornberg, R., Pozzoli, T., Gini, G., & Hong, S. J. (2017). Bullying and repeated conventional transgressions in Swedish schools: How do gender and bullying roles affect students’ conceptions? Psychology in the Schools, 54(9), 1189–1201. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22054

- Thornberg, R., Wänström, L., Gini, G., Varjas, K., Meyers, J., Elmelid, E., Johansson, A., & Mellander, E. (2021). Collective moral disengagement and its associations with bullying perpetration and victimization in students. Educational Psychology, 41(8), 952–966. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2020.1843005

- Thornberg, R., Wänström, L., & Hymel, S. (2019). Classroom social-cognitive processes in bullying: A short-term longitudinal multilevel study. Frontiers in Psychology, 10Article, 1752. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01752

- Thornberg, R., Wänström, L., Pozzoli, T., & Hong, J. S. (2019). Moral disengagement and school bullying perpetration in middle childhood: A short-term longitudinal study in Sweden. Journal of School Violence, 18(4), 585–596. https://doi.org/10.1080/15388220.2019.1636383

- Vitoroulis, I., & Vaillancourt, T. (2018). Ethnic group differences in bullying perpetration: A meta-analysis. Journal of Research on Adolescence: The Official Journal of the Society for Research on Adolescence, 28(4), 752–771. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12393

- Wang, C., Ryoo, J. H., Swearer, S. M., Turner, R., & Goldberg, T. S. (2017). Longitudinal relationships between bullying and moral disengagement among adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 46(6), 1304–1317. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-016-0577-0

- White, J., Bandura, A., & Bero, L. (2009). Moral disengagement in the corporate world. Accountability in Research, 16(1), 41–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/08989620802689847

- Xu, M., Macrynikola, N., Waseem, M., & Miranda, R. (2020). Racial and ethnic differences in bullying: Review and implications for intervention. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 50, 101340. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2019.101340