Abstract

This study investigates the effects of a mindfulness-based program implemented by teachers for their primary school students in the Arab sector of Israel. The study included 958 fourth, fifth, and sixth-grade students, with 659 completing the program and 299 students serving as controls. The effectiveness of the program was assessed through interpersonal and intrapersonal questionnaires, measuring anxiety, perceived stress, mindfulness, tolerance towards an outgroup, and teachers’ availability and acceptance. Students completed the questionnaires before and after the program. Significant interactions between time and group were observed in all measured outcomes, indicating the program’s positive effects. The findings suggest that mindfulness practices, known to be effective for primary school students in Western societies, can also be effective in collectivist cultures, such as the Arab society in Israel.

Introduction

Mindfulness can be defined as the awareness that emerges through paying attention on purpose, in the present moment and non-judgementally to the unfolding of experience moment by moment (Kabat-Zinn, Citation2003). The practice of mindfulness has been found to enhance various qualities including empathy and self-compassion (Birnie et al., Citation2009), wellbeing and positive emotions (Sin & Lyubomirsky, Citation2009), emotional self-regulation and cognitive flexibility, and reduce stress and anxiety (Hölzel et al., Citation2011; Meiklejohn et al., Citation2012). While mindfulness interventions initially found their roots in medicine, their applications have since expanded to encompass various fields such as psychology, health services, business, and education (Meiklejohn et al., Citation2012). According to Hölzel et al. (Citation2011), the mechanisms by which mindfulness impacts stress and anxiety involve attention regulation, body awareness, emotion regulation, and a shift in self-perspective. These mechanisms form the foundation of mindfulness qualities, such as compassion and wellbeing (Birnie et al., Citation2009).

Mindfulness training may have different approaches based on the intentions behind them and the experiential understandings the practices may aim to develop (Levit-Binnun et al., Citation2021). An important distinction among various approaches lies in their reference to compassion, indicating sensitivity to both self and others’ suffering with a commitment to prevent and alleviate it (Gilbert & Choden, Citation2013). While mindfulness encourages being in the present moment, compassion involves exercises that evoke both past and future scenarios. Whereas mindfulness trains a non-judgemental acceptance of one’s experience, compassion practice trains states of empathy, warmth, and kindness towards oneself and others and has a more prominent ethical component (Roca et al., Citation2021).

As a part of mindfulness practice or separately, compassion can be cultivated in schools, modelled for students within the classroom, starting from pre-school and continuing through graduate school (Jazaieri, Citation2018). In the Buddhist tradition, mindfulness and compassion training are integral components of the same training (Dalai Lama & Cutler, Citation1998). Roeser et al. (Citation2022) proposed moving beyond the division between research on mindfulness and compassion in schools and instead advocating for an integrated approach to studying mindfulness and compassion. According to these evolving perceptions, there has been a growing trend of combining both approaches in various programs (Conversano et al., Citation2020).

Mindfulness and compassion training in schools

Mindfulness-based interventions designed for children, including primary school students, have been subject to extensive research. Previous studies have demonstrated that mindfulness practices among primary school students improve their overall well-being and reduce anxiety (Meiklejohn et al., Citation2012) and stress. Additionally, mindfulness-based interventions among primary school students can support positive inter-personal effects, such as improving students’ relationships with peers and teachers (Mendelson et al., Citation2010) and enhancing pro-social behaviour (Felver et al., Citation2017). Importantly, Black and Fernando (Citation2014) demonstrated the effectiveness of mindfulness-based interventions in primary schools, also among minority students. Their study revealed that the participation in the intervention increased attention, self-control, participation in class, and consideration for others, with effects lasting for the seven-week follow-up period.

To enhance the accessibility of mindfulness-based programs for children, it is crucial to develop programs specifically designed for teachers in addition to external trainers. This approach equips teachers to cultivate their own mindfulness practice, which they can then share with students to help them develop theirs. Such programs are valuable for both organisational and educational purposes. Organisational benefits include reducing reliance on external trainers and promoting sustainability, while educational benefits stem from integrating mindfulness into the teaching process and enabling more frequent and tailored training to meet the needs of individual classes (Crane et al., Citation2010).

Equally important is the recognition that teachers’ own mindfulness practice can enhance their ability to manage the classroom, thereby affecting students even without formal practice together (Tarrasch & Berger, Citation2022). In this regard, research has shown that teachers’ ability to effectively manage classrooms directly impacts students’ motivation and indirectly influences students’ academic achievements (van Dijk et al., Citation2019). Moreover, teachers’ emotional and social competence, also enhanced through mindfulness practice, have been identified as mediators in generating these same effects on their students (Jennings & Greenberg, Citation2009). Additionally, teachers’ level of mindfulness play a role in mitigating the negative impact of stress on teachers ability to provide emotional support to students in the classroom (Molloy Elreda et al., Citation2019).

Recognising the impact of teacher mindfulness on student well-being, several programs have been developed to equip educators with these essential skills. The Cultivating Awareness and Resilience in Education (CARE) program (Jennings et al., Citation2013) focuses on enhancing teachers’ emotional awareness and regulation skills to better respond to student needs. The Stress Management and Resiliency Techniques (SMART) program (Cullen & Wallace, Citation2010) provides teachers with mindfulness-based techniques for stress management and promoting resilience. Another program, which is the one to be assessed in the present study, the “Call to Care – Israel” (C2C-I) program for teachers (Tarrasch et al., Citation2020), combines mindfulness and compassion training with three modes of care: receiving care from others, cultivating self-care, and extending care to others. Its intended outcomes are the reduction of stress and anxiety, along with the enhancement of tolerance and acceptance.

In the recent model proposed and assessed by Roeser et al. (Citation2023), the practice of mindfulness, emotion regulation, and compassion among middle school teachers was found to have a positive impact on various outcomes. Specifically, teachers’ practice enhanced their teaching skills and occupational self-compassion and reduced job stress and anxiety. Additionally, it improved classroom organisation, but only in the long term, specifically four months after the intervention.

Traditionally, mindfulness programs have primarily focused on developing present-moment awareness, attention, and self-regulation skills. However, in recent years, there has been a shift in mindfulness programs designed for teachers, with an increasing emphasis on incorporating compassion into their curriculum (e.g. Roeser et al., Citation2022; Tarrasch et al., Citation2020). This shift recognises the interconnected nature of individuals within the educational context and acknowledges the significance of cultivating compassion for the well-being of teachers, as well as for the benefit of their students and the overall learning environment. Teachers are encouraged to cultivate self-compassion and develop compassion towards their students, fostering a sense of care, empathy, and kindness. By creating a compassionate classroom environment, teachers enhance their availability to students and establish a safe and supportive space for students to thrive academically, emotionally, and socially.

The implementation of mindfulness programs by teachers among their students is influenced by many factors. These include the teacher’s own understanding and beliefs regarding mindfulness, and their instructional strategies for incorporating mindfulness within the classroom setting (Kenwright et al., Citation2023). Additionally, contextual factors such as school culture, administrative support, and available resources play crucial roles in shaping how mindfulness programs are delivered and received by students. Moreover, student characteristics, such as cultural background, can significantly impact their receptivity and engagement with these programs (DeLuca et al., Citation2018)). Furthermore, the fidelity and feasibility of program delivery, ongoing professional development and support for teachers, and the alignment of mindfulness practices with curriculum objectives all contribute to the efficacy and sustainability of mindfulness interventions in educational settings (Emerson et al., Citation2020). However, the current study lacks the capacity to evaluate these factors.

As of today, there have been no studies conducted to assess the effects of mindfulness-based intervention programs in the Arab sector in Israel. It is important to acknowledge this gap in research, as it highlights the need for further investigation and understanding of the potential benefits and effectiveness of such programs within this specific cultural and educational context.

Arabic society and education in Israel

Arabic fundamental culture exhibits several distinctive features compared to Western culture, encompassing language, religion, cultural heritage, and family structures. These cultural differences may have potential implications for the implementation of mindfulness training programs (Pigni, Citation2010), although the specific extent and impact of these differences have not been extensively researched. It is important to recognise that the Arabic society constitutes a growing segment of Israel’s overall population. According to the Israel Central Bureau of Statistics (Citation2019), 21% of the total population in Israel is Arabic. The Arab society in Israel is characterised by significant socioeconomic and cultural disparities, high levels of religiousness and tradition (Reches & Rudnicki, Citation2009), and larger household sizes (Shinwell et al., Citation2015). Over time, there have been improvements in education standards in the Arab Israeli sector, including efforts to reduce overcrowded classrooms, enhance student achievements (Shinwell et al., Citation2015), increase graduation rates, and narrow the education gender gap. However, despite these positive trends, substantial educational gaps still exist when comparing the Arab and Jewish populations in Israel (Ofek-Shanny, Citation2020).

Generally, the Arab education system in Israel is characterised with traditional perceptions and practices, which are compatible with the traditional features of the Arab society. These perceptions and practices include also traditional learning programs and teaching methods (Arar & Abu Romi, Citation2017). Although attempts have been made to introduce alternative teaching methods, such as individual instruction, active learning, and group learning, the success of these attempts has been limited (AbuʽAsba, Citation2007; Magadley et al., Citation2019).

AbuʽAsba (Citation2007) cautioned against directly importing successful methods from the Jewish educational system without first considering the specific cultural needs of Arab students and teachers. In a recent study conducted by Rayan and Ahmad (Citation2017), mindfulness-based interventions have been observed to reduce stress, anxiety, and depression symptoms among parents in Arab society. Their findings suggest that these interventions are culturally adaptable and effective in improving mental well-being within Arab society. Furthermore, in a study conducted within the Jewish-Israeli society, Birnbaum (Citation2005) proposed that mindfulness practice may reduce aggressive behaviours among students. She suggests that this effect is mediated by cultural values such as collectivism or individualism, as well as personal self-awareness. These mechanisms hold significant relevance within the Israeli society, particularly in light of social group conflicts.

The current study

According to the literature presented above, in recent years, a plethora of mindfulness-based intervention programs have been implemented and found effective in improving various metrics among students and teachers. However, several aspects of these programs’ implementation have not been studied sufficiently. For instance, the integration of mindfulness with compassion, the impact of teachers’ mindfulness practice on students, and the implementation of mindfulness-based intervention programs within the Arab sector in Israel. The current study aims to address these challenges.

This study examined the impact of teacher participation in a mindfulness and compassion-based program, as well as the implementation of mindfulness with their students, on different aspects of students’ abilities and attitudes. Specifically, anxiety and perceived stress, along with intra-personal abilities, namely mindfulness, and inter-personal indices of tolerance towards outgroups and perceptions of teacher availability and acceptance.

Our hypotheses posited that when teachers engaged in mindfulness and compassion practice and implemented it with their students, it would lead to a reduction in students’ anxiety and perceived stress, an increase in their mindfulness levels, an improvement in their tolerance towards outgroups, and an enhancement in their perception of teacher availability and acceptance.

Method

Procedure and sample

In Israel, professional development and training for teachers are typically offered through regional centres. Each centre serves approximately fifty or more schools. For this study, two centres that cater to schools in the Arab sector were selected based on their geographical location. The research team approached the managers of these centres and presented the study proposal. Subsequently, the centre managers contacted the principals of the schools under their supervision and requested volunteers to participate in the study. Eight principals from primary schools volunteered for participation. Six schools were randomly assigned to participate in the “Call to Care – Israel” (C2C-I) program, while two schools were designated as the control group and attended a different workshop offered by the centre. Within each participating school, teachers working with students in 4th to 6th grade were invited to take part in the programs and received credits for their participation. Between fifteen and twenty-five teachers from each school, totalling 132 teachers, participated in the workshops. Eighty percent of the teachers were female. The teachers’ seniority ranged from 4 to 43 years, with a mean of 16.6 years (SD = 8.12). Their ages ranged from 26 to 63 years, with a mean of 40.24 years (SD = 7.51).

Teachers who attended the C2C-I workshop were responsible for guiding mindfulness practices in their classrooms throughout the school year. A total of 150 students from each school were selected using clustered sampling. This involved randomly selecting two classes from each grade (4th to 6th), and within each class, students whose parents provided informed consent were asked to fill out questionnaires (approximately 85% participation rate). After a 5% drop out ratio between the two measuring times, 958 students participated in the study, with 659 in the experimental group (68.8%). Among the experimental group, there were 211 fourth graders (32.0%), 228 fifth graders (34.6%), and 220 sixth graders (33.4%). The control group consisted of 299 students, including 117 fourth graders (39.1%), 93 fifth graders (31.1%), and 89 sixth graders (29.8%).

The gender composition of the two groups did not show a significant difference (χ2 (1) = 0.29, p = .590). The overall distribution consisted of 56% males and 44% females.

Intervention: the mindfulness and compassion-based workshop for teachers – a call to care-Israel (C2C-I)

Teachers were provided with the necessary knowledge to practice mindfulness themselves and guide mindfulness-based activities for their students through the participation in a C2C-I workshop, which was conducted separately for each school. The C2C-I program was developed based on the Call to Care program, originally initiated by the Mind and Life Institute. It drew inspiration from contemplative approaches such as Sustainable Compassion Training (Makransky, Citation2007) and social-emotional learning approaches like the Erase Stress Prosocial program (ESPS; Berger, Citation2014). The C2C-I program integrated various elements from these formats to create a comprehensive framework.

The program consisted of twelve weekly meetings spanning a duration of three months, with each meeting lasting 2.5 h. The program focused on mindfulness and incorporated the three modes of care: receiving care from others, cultivation of self-care, and extending care to others. Each mode encompassed four specific topics, which are outlined in .

Table 1. Call to care-Israel mindfulness program to train teachers.

During the workshop, teachers received psycho-didactic materials and had opportunities to share their experiences with other participants. Teachers were encouraged to practice at home. All workshops were conducted by the same Arab facilitator, who had over 10 years of experience in mindfulness practice. The facilitator received 15 h of training from one of the researchers, which included lectures, discussions, and simulations of the contemplative practices and experiential exercises. To ensure the program’s fidelity, the second author regularly observed the facilitator throughout the program and provided off-site supervision on a weekly basis. The facilitator also observed some of the teachers while they worked with their students and provided them with off-site supervision as well.

Teachers received instructions on various mindfulness exercises to implement with their students, including mindful breathing, body scan, still quiet place, mindful walking, “Bubble” mindfulness (learning to let go of feelings and thoughts), and paying attention to stimuli in the environment (e.g. sounds, smells). However, the study did not assess the fidelity of teachers’ practice with their students or how the practice was understood, interpreted, and utilised by teachers. In the final meeting, teachers reported using mindfulness techniques frequently, often on a daily basis. The frequency and choice of exercises varied among teachers based on their personal preferences and perceived needs of their students and class.

Control teachers participated in a two-month workshop consisting of weekly 2.5-h meetings called “The Class as a Learning Community.” The workshop focused on topics including the organisation of teaching processes, recognising otherness as a value and learning resource, promoting active learning, managing teacher-student time, implementing flexible learning structures, fostering a supportive study environment, employing differentiated instruction, utilising a variety of teaching methods, exploring different learning methods, encouraging student feedback, and creating meaningful teacher-student discourse

Study design

Students completed questionnaires at two time-points: before the start of the teachers’ workshop (approximately three months into the school year) and four months later (one month after the conclusion of the teachers’ workshop). For students who were absent during administration, their teachers instructed them to complete the questionnaires at a later date.

Measures

Anxiety

Anxiety levels were measured using the short version of the Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale (SCAS), which was developed by Spence (Citation1998). The SCAS consists of eight items on a Likert scale ranging from 0 (never) to 3 (always), with items such as “I worry about things.” The internal consistency reliability of the questionnaire, calculated among 8–12-year-old children, was α = 0.92. In this study, the reliability values at the pre- and post-measures were α = 0.62 and 0.70, respectively.

Stress

The Perceived Stress Scale for Children, adapted for children by White (Citation2014), was used to assess the stress levels. The scale measures subjective stress and consists of six items on a Likert scale ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (very often), indicating the extent to which life situations are experienced as stressful. Example items include “In the last week, how often did you feel angry?”. The internal consistency reliability of the questionnaire ranges between α = 0.82 and α = 0.86. In the present study, the questionnaire’s reliabilities were α = 0.41 and α = 0.52 at the pre- and post-measures, respectively, indicating a low reliability.

Tolerance

Tolerance towards outgroups was assessed using the Tolerance Questionnaire developed by Berger et al. (Citation2015). The questionnaire consists of three parts. The first part focuses on readiness for social contact and includes five activities: meeting, playing, studying, inviting to one’s home, and being one’s guest. Participants indicate their degree of readiness to engage in each activity with a child of another ethnicity, specifically here towards Jewish students. Responses are rated on a Likert scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 4 (very much). The internal consistency reliability of the sub-scale has been reported to range between 0.82 and 0.86 in previous studies (Berger et al., Citation2015). In the present study, the reliability values of this sub-scale at the pre- and post-measures were α = 0.88 and α = 0.90, respectively. The second part of the Tolerance Questionnaire assessed children’s negative thoughts about others, specifically related to Arab-Jewish stereotypes (Teichman et al., Citation2007). This part of the questionnaire included word pairs describing possible characteristics of the other ethnicity (Jews), such as smart/stupid, friendly/unfriendly, clean/dirty, pretty/ugly, and non-violent/violent. Participants were asked to indicate the extent to which each characteristic is representative of the external group, using a Likert scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 4 (very much). The items were recoded so that higher scores indicate more negative characteristics. The internal consistency reliability of this part of the questionnaire has been reported to range between 0.84 and 0.90 in previous studies (Berger et al., Citation2015). In the current study, the reliability values of this sub-scale at the pre- and post-measures were α = 0.66 and α = 0.80, respectively. The third part of the questionnaire assessed emotional prejudice and included five emotions: hostility, hatred, anger, understanding (reversed), and indifference. Participants were asked to indicate the extent to which they felt each emotion on a Likert scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 4 (very much). Previous studies have reported the internal consistency reliability of this part of the questionnaire to range between 0.75 and 0.84 (Berger et al., Citation2015). In the current study, the reliability values of this sub-scale at the pre- and post-measures were α = 0.90 and α = 0.95, respectively.

Teachers’ availability

Teachers’ availability was assessed using the Teachers’ Availability and Acceptance factor from the Children’s Appraisal of Teacher as a Secure Base (CATSB) scale developed by Al-Yagon and Mikulincer (Citation2006). This factor consists of 17 statements that measure children’s appraisal of their homeroom teacher as a secure base, including items such as “My teacher is always there to help me when I need her” on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly dis-identified) to 7 (strongly identified), with higher values indicating a stronger attachment to teachers and higher perceived availability and acceptance. The CATSB scale has been shown to have high reliability, with an alpha coefficient of 0.90. In the present study, the reliability values at the pre- and post-measures were α = 0.88 and α = 0.86, respectively.

Mindfulness

Mindfulness was assessed utilising the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire, initially developed by Baer et al. (Citation2006) and modified for children by Ginesin (Citation2013). The assessment in this study focused exclusively on the overall scale measure. The questionnaire consisted of 39 statements on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (never or almost never correct) to 5 (very often or always correct), with items like “While walking, I am aware of the sensations in my body.” The overall scale reliability was reported as 0.93 (Christopher et al., Citation2012). The pre- and post-measure reliabilities were α = 0.66 and α = 0.76, respectively.

The questionnaires were translated into Arabic using the double-back translation method, involving two independent translators. The translations were then reviewed by a third person who selected the preferred wording for each statement and translated the questionnaires back into Hebrew. A fourth person compared the two versions, and any discrepancies were resolved through collaboration between the initial translators.

Statistical analysis

For each dependent measure, a Mixed Linear Model was conducted, with the fixed factors of: measurement time (pre/post), group (C2C-I/control), and their interaction. The model also included random factors of class nested within grade, nested within school, nested within manipulation, with gender as a covariate. Alpha was set at .001 to minimise the risk of Type I error resulting from analyses conducted on multiple variables. Significant interactions were followed by Bonferroni’s corrected post-hoc comparisons, to further investigate the effects.

Compliance with ethical standards

All procedures conducted in this study were approved by the Tel Aviv University Ethics Committee and the Office of the Chief Scientist of the Ministry of Education. Informed consent was obtained from the parents of individual participants involved in the study. The consent form provided detailed information about the study’s purpose, procedures, potential risks and benefits, and measures taken to ensure confidentiality. Parents had the opportunity to ask questions before giving their consent. It was emphasised that participation was voluntary, and they could withdraw their child’s involvement at any time without facing any consequences. Similarly, children were also informed before each questionnaire administration that they had the right to withdraw their participation at any point without penalty. The study implemented measures to safeguard the privacy and confidentiality of participants, including the use of anonymized data and secure storage of participant information.

Results

display the correlations between the dependent variables at pre- and post-test. The results indicate significant relationships among various variables. Specifically, at both time points anxiety showed significant correlations with stress, negative thoughts about the other, teachers’ availability and acceptance, and mindfulness. Similarly, stress was significantly correlated with negative thoughts about the other, teachers’ availability and acceptance, and mindfulness. Readiness for social contact demonstrated a significant correlation with negative thoughts about the other, emotional prejudice, and teachers’ availability and acceptance. Moreover, negative thoughts about the other were significantly correlated with emotional prejudice, teachers’ availability and acceptance, and mindfulness. Lastly, teachers’ availability and acceptance exhibited a significant correlation with mindfulness.

Table 2. Pearson correlations between dependent measures at pre (upper value) and post-test (lower value).

To examine differences between the two groups in the dependent measures at the pre-test, independent samples t-tests were conducted. The results indicated that the C2C-I group exhibited significantly higher levels of anxiety (t(956) = −2.21, p < 0.05) and stress (t(956) = −2.24, p < 0.05) compared to the control group. Mixed linear models revealed significant interactions between group and time for all the variables assessed. The effects of time, group, and the interaction between time and group, along with the Intra-Class Correlation coefficients (ICC’s) of the random effect in the design, are summarised in .

Table 3. Results of mixed linear models performed on study variables, including main effects of time (pre vs. post), group and interaction between time and group, and ICC’s of the random effects.

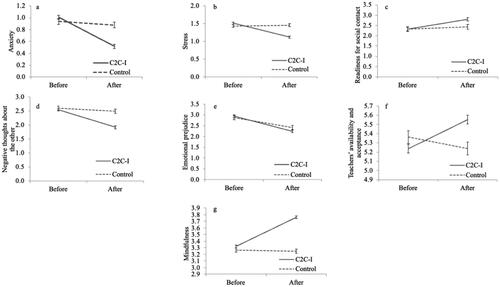

shows Bonferroni’s corrected post-hoc tests, which revealed a significant reduction in anxiety in the control group (mean difference [m.d.] = −0.061, p = 0.001), as well as in the C2C-I group (m.d. = −0.495, p < 0.001); although the decrease in the C2C-I group was significantly stronger than in the control group. As presented in , post-hoc analyses revealed a significant reduction in stress in the C2C-I (m.d. = −0.391, p < 0.001), but not in the control group (m.d. = 0.023, n.s.). As can be seen in on readiness for social contact, post-hocs revealed a significant increase in both groups, however the increase was larger among the C2C-I participants (m.d. = 0.479, p < 0.001) when compared to controls (m.d. = 0.116, p < 0.01). As shown in on negative thoughts about others, post-hoc analyses revealed a significant decrease in negative thoughts among both groups; however the significant interaction indicates that the decrease in the control group (m.d. = −0.105, p < 0.01) was slighter than that obtained in the C2C-I group (m.d. = −0.629, p < 0.001). presents a significant decrease in prejudice in both groups, while the reduction was more pronounced in the C2C-I (m.d. = −0.702, p < 0.001) when compared to the control group (m.d. = −0.45, p < 0.001). reveals a significant decrease in teachers’ availability and acceptance in the control group (m.d. = −0.124, p < 0.001), whereas an increase was obtained among participants in the C2C-I group (m.d. = 0.315, p < 0.001). Finally, depicts a significant increase in mindfulness among participants in the C2C-I group only (m.d. = 0.441, p < 0.001).

Figure 1. Group averages and SE of the dependent measures before and after the manipulation among controls and C2C-I participants.

Discussion

The C2C-I group exhibited a more pronounced decrease in anxiety, negative thoughts about others, and prejudice, along with a greater increase in readiness for social contact compared to the control group. Furthermore, only the C2C-I group demonstrated a significant reduction in stress and an increase in teachers’ availability and acceptance, as well as in mindfulness. It is worth noting that the observed effects in stress reduction among students are particularly noteworthy given the relatively low reliability of the scale in the present study. The observed increase in mindfulness in the experimental group aligns with previous research demonstrating that mindfulness practice leads to higher reported levels of mindfulness (Ager et al., Citation2015; Felver et al., Citation2017), and may serve as a manipulation check.

Reductions in stress and anxiety

The observed greater reduction in anxiety in the C2C-I group compared to the control group is in line with previous research. Studies have consistently demonstrated that mindfulness practices among students can effectively reduce anxiety (Mendelson et al., Citation2010). Additionally, mindfulness training has been shown to enhance individuals’ ability to cope with stressful situations (Coholic, Citation2010). Due to our study design, we are unable to distinguish between the direct effects of student practice and the indirect effects through their teachers’ practice. It is possible that the decrease in anxiety could also be attributed to the teachers’ practice. In fact, previous research has shown that implementing mindfulness and compassion among teachers has led to reductions in anxiety among their students (Tarrasch & Berger, Citation2022)

According to the literature, the stress and anxiety reduction achieved by mindfulness practice among students may be attributed to multiple direct and indirect effects. For instance, Hoge et al. (Citation2018) have shown that anxiety reduction is associated with improved emotional resilience and concentration. Similarly, the decrease in stress observed in the C2C-I group aligns with findings from prior studies, suggesting that the decline in student stress levels could potentially be attributed to a decrease in teachers’ stress levels (Harpin et al., Citation2016). This is also supported by a study indicating that teachers’ occupational stress levels, as indicated by their burnout levels, were observed to be predictive of students’ stress levels, as measured by their morning cortisol variability (Oberle & Schonert-Reichl, Citation2016). Generally, the anxiety and stress reductions observed in this study indicate that the effects of the mindfulness program among Arab Israeli students may have similar effects to those seen in participants from Western societies.

Effects on tolerance and prejudice

The noteworthy findings of our study primarily focus on tolerance and prejudice, which hold great relevance in societies experiencing conflict, such as the Arab and Jewish societies in Israel. In the C2C-I group, we observed notable enhancements in students’ tolerance towards Jews, as indicated by increased readiness for social contact. Additionally, emotional prejudice and negative thoughts about Jews showed a decline, highlighting positive changes in attitudes.

The observed increase in willingness for relationships and reduction in prejudice align with previous research findings. Studies have shown that mindfulness practice among students has improved their interpersonal relationships (Mendelson et al., Citation2010), fostered pro-social behaviour (Harpin et al., Citation2016), enhanced consideration for others, including minority groups (Black & Fernando, Citation2014), reduced prejudice, and promoted positive thoughts towards minorities (Berger et al., Citation2018). However, the distinctiveness of our study lies in its assessment of the readiness for relationships specifically from a minority group towards the majority in the context of intergroup conflict. These findings hold particular significance in present times, especially in societies like Israel, where intercultural divisions and polarisation are escalating, posing challenges to the future of coexistence, cooperation, and democracy (McCoy & Somer, Citation2019).

Effects on students-teachers relations

Another important finding of our study pertains to the relationship between students and teachers. We discovered that, over the course of the year, children in the control group reported a decline in their perception of teachers’ availability and acceptance, whereas children in the C2C-I group exhibited a significant increase. The improvement in students’ perception of teachers’ availability and acceptance holds great significance as positive student-teacher relationships and understanding are known to contribute to enhanced academic achievements (Thijs & Fleischmann, Citation2015), improved behaviour and reduced bullying incidents (Longobardi et al., Citation2018). Moreover, strong student-teacher relationships foster pro-social behaviour and cultivate a positive attitude towards school (Longobardi et al., Citation2018). These findings underscore the importance of nurturing positive connections between students and teachers for overall academic and socio-emotional development.

Theoretical and practical contributions

In summary, our study shows that the C2C-I program had a positive impact on the psychological and relational skills of students. These positive effects could have important implications for the educational system as a whole. By reducing students’ anxiety and stress levels and enhancing teachers’ availability, the program has the potential to increase motivation and ultimately lead to improved academic performance. The reduction in stress and anxiety among students may also contribute to better behaviour and to a decrease in school-related violence. Furthermore, the improvements in tolerance measures offer the potential of strengthening relationships between different groups within the divided Israeli society. This may be particularly relevant when taking a holistic approach that incorporates mindfulness practice among all stakeholders in educational settings.

It is important to note again that in our study, the indirect effects of teachers’ practice on students and the direct effects through teachers’ guidance to students are confounded, making it impossible to distinguish between them. The obtained effects on students could be attributed to the direct effect, the indirect effect, or a combination of both. This is definitely a limitation in terms of assessing the specific mechanisms of action of the program. However, from a practical standpoint, our methodology, which closely aligns with the whole-school approach (Kielty et al., Citation2017), was found to be effective among children. Our results suggest that the effects observed were likely a result of the teachers’ involvement, either through their own mindfulness practice and modelling or through their guidance of students. This finding may support previous research showing that teachers can successfully become mindfulness instructors after appropriate training (Crane et al., Citation2010).

Our study makes a notable contribution to the field by highlighting the potential of mindfulness and compassion practices in reducing stress and anxiety among Arab students. Additionally, we observed an increase in their willingness to engage with outgroups. By emphasising the benefits of mindfulness and compassion interventions in this specific context, our study expands the understanding of how these practices can be tailored to diverse populations, fostering inclusivity and promoting positive social interactions.

Our study acknowledges that the outcomes observed may be attributed to different aspects of the practice, either mindfulness or compassion and care. Based on previous findings, it is more likely that differences in mindfulness, anxiety, and stress can be attributed to the mindfulness elements of the practice, either through the practice of teachers or students. On the other hand, the improvements in readiness for social contact, negative thoughts about others, and emotional prejudice are more likely a result of practice of compassion and care by students. Furthermore, the effects observed in teachers’ availability and acceptance could be linked to the teachers’ own mindfulness and compassion practices. In order to better understand these relationships and causal effects, future studies should aim to isolate these factors.

A final consideration addresses the contributions related to specific aspects of mindfulness training that were not thoroughly examined in the current study. For instance, the study did not evaluate factors such as practice quality, practice dosage, or tailoring the program to individual student needs. Although this omission represents a limitation of the study, as will be elaborated upon, the notable findings obtained despite these uncontrolled factors support the overarching conclusion that the implemented mindfulness program contributes to improvements holistically, notwithstanding specific characteristics and program components that require more comprehensive control and assessment.

Limitations and directions for future research

In addition to the limitations already discussed, this study had additional limitations that should be taken into account. Firstly, the allocation of participants to the groups was not randomised, as the classes were predetermined by the participating schools’ principals. This may introduce a potential bias in group composition. Secondly, as already mentioned, the study design did not allow for the differentiation between the direct effects of students’ practice on the measured outcomes and the indirect effects of teachers’ practice on student behaviour through their interactions. This makes it challenging to attribute specific effects solely to the students’ practice or the teachers’ influence. Thirdly, there was no monitoring of teachers’ practice with their students, making it unclear whether teachers implemented the program consistently or what specific practices they employed. However, comments from teachers indicated frequent use of mindfulness techniques. Lastly, the control group received a shorter intervention (20 h) compared to the C2C-I group (30 h), which introduces a potential disparity in the intervention duration between the groups. These limitations should be considered when interpreting the study’s findings.

As mentioned earlier, we fully acknowledge the importance of considering various factors when evaluating the efficacy of mindfulness programs. Factors such as dosage, program implementation quality, fidelity to the curriculum, responsiveness to individual needs, and differentiation between program approaches play a crucial role in understanding the outcomes of mindfulness interventions (Durlak et al., Citation2011). In our study, we recognise that we have only addressed a small subset of these requirements.

Future studies should aim to address the limitations of the present quasi-experimental study and strive to replicate and validate the results using a fully experimental design. It would be valuable to include another minority group to generalise the effects of mindfulness on prejudice towards outgroups. By employing a more rigorous experimental design, researchers can better control for confounding variables and establish a clearer cause-and-effect relationship between mindfulness practice and its impact on well-being as well as intergroup attitudes and behaviours. This would contribute to a deeper understanding of the potential of mindfulness interventions in reducing prejudice and promoting positive intergroup relations.

Conclusions

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the impact of a mindfulness-based intervention program conducted by teachers themselves among primary school students in Israel’s Arab sector. Our study’s key finding is that mindfulness practice is also effective in enhancing intrapersonal and interpersonal skills among primary school students in Israel’s Arab sector. It is worth noting that mindfulness practice is often considered an intervention focused on the individual. Although the Arab society is known for its strong collectivist culture, our findings suggest that mindfulness practice can indeed be effective even in collectivistic cultures. This has two important theoretical implications. Firstly, mindfulness-based interventions can be culturally adaptable and relevant for students in Arab society. Secondly, mindfulness practice among Arab students may contribute to their self-awareness and engagement in self-improvement activities, concepts that remain uncommon for this society. The fact that the program was implemented by trained teachers themselves, rather than external instructors as commonly seen in previous studies, presents a promising avenue for scaling up such programs in the future.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

All data are available at: https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/wv5pybhgvg/1

References

- AbuʽAsba, H. (2007). Arabic education in Israel: Dilemmas of national minority (in Hebrew). Floersheimer Institute for Policy Studies.

- Ager, K., Albrecht, N. J., & Cohen, M. (2015). Mindfulness in schools research project: Exploring students’ perspectives of mindfulness. Psychology, 06(07), 896–914. https://doi.org/10.4236/psych.2015.67088

- Al-Yagon, M., & Mikulincer, M. (2006). Children’s appraisal of teacher as a secure base and their socio-emotional and academic adjustment in middle childhood. Research in Education, 75(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.7227/RIE.75.1

- Arar, K., & Abu Romi, A. (2017). School-based management: Arab education system in Israel.

- Baer, R. A., Smith, G. T., Hopkins, J., Krietemeyer, J., & Toney, L. (2006). Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment, 13(1), 27–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191105283504

- Berger, R. (2014). The erase-stress (ES) programmes: Teacher-delivered universal school-based programmes in the aftermath of disasters. In D. Mitchel & V. Karr (Eds.), Crises, conflict and disability: Ensuring equality (pp. 96–104). Routledge.

- Berger, R., Abu-Raiya, H., & Gelkopf, M. (2015). The art of living together: Reducing stereotyping and prejudicial attitudes through the Arab-Jewish class exchange program (CEP). Journal of Educational Psychology, 107(3), 678–688. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000015

- Berger, R., Brenick, A., & Tarrasch, R. (2018). Reducing Israeli-Jewish pupils’ outgroup prejudice with a mindfulness and compassion-based social-emotional program. Mindfulness, 9(6), 1768–1779. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-018-0919-y

- Birnbaum, L. (2005). Adolescent aggression and differentiation of self: guided mindfulness meditation in the service of individuation. TheScientificWorldJournal, 5, 478–489. https://doi.org/10.1100/tsw.2005.59

- Birnie, K., Speca, M., & Carlson, L. (2009). Exploring self-compassion and empathy in the context of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR). Stress and Health, 26, 359–371. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.1305

- Black, D. S., & Fernando, R. (2014). Mindfulness training and classroom behavior among lower-income and ethnic minority elementary school children. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 23(7), 1242–1246. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-013-9784-4

- Christopher, M. S., Neuser, N. J., Michael, P. G., & Baitmangalkar, A. (2012). Exploring the psychometric properties of the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire. Mindfulness, 3(2), 124–131. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-011-0086-x

- Coholic, D. (2010). Arts activities for children and young people in need: Helping children to develop mindfulness, spiritual awareness and self‑esteem. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Conversano, C., Ciacchini, Ŕ., Orrù, G., Di Giuseppe, M., Gemignani, A., & Poli, A. (2020). Mindfulness, compassion, and self-compassion among health care professionals: What’s new? A systematic review. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1683. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01683

- Crane, R. S., Kuyken, W., Hastings, R. P., Rothwell, N., & Williams, J. M. G. (2010). Training teachers to deliver mindfulness-based interventions: Learning from the UK experience. Mindfulness, 1(2), 74–86. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-010-0010-9

- Cullen, M., & Wallace, L. (2010). Stress management and relaxation techniques in education (SMART) training manual. Unpublished manual. Impact Foundation.

- DeLuca, S. M., Kelman, A. R., & Waelde, L. C. (2018). A systematic review of ethnoracial representation and cultural adaptation of mindfulness- and meditation-based interventions. Psychological Studies, 63(2), 117–129. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12646-018-0452-z

- Durlak, J. A., Weissberg, R. P., Dymnicki, A. B., Taylor, R. D., & Schellinger, K. B. (2011). The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: A meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions. Child Development, 82(1), 405–432. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01564.x

- Emerson, L.-M., de Diaz, N. N., Sherwood, A., Waters, A., & Farrell, L. (2020). Mindfulness interventions in schools: Integrity and feasibility of implementation. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 44(1), 62–75. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025419866906

- Felver, J. C., Felver, S. L., Margolis, K. L., Kathryn Ravitch, N., Romer, N., & Horner, R. H. (2017). Effectiveness and social validity of the soles of the feet mindfulness-based intervention with special education students. Contemporary School Psychology, 21(4), 358–368. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40688-017-0133-2

- Gilbert, P., & Choden. (2013). Mindful compassion: Using the power of mindfulness and compassion to transform our lives. Constable-Robinson.

- Ginesin, E. (2013). The influence of the mindfulness-based ‘language of mindfulness’ program on attentiveness, anxiety and positive emotions among primary school students (in Hebrew). Tel Aviv University.

- Harpin, S., Rossi, A., Kim, A., & Swanson, L. (2016). Behavioral impacts of a mindfulness pilot intervention for elementary school students. Education, 137(2), 149–156.

- Hoge, E. A., Bui, E., Palitz, S. A., Schwarz, N. R., Owens, M. E., Johnston, J. M., Pollack, M. H., & Simon, N. M. (2018). The effect of mindfulness meditation training on biological acute stress responses in generalized anxiety disorder. Psychiatry Research, 262, 328–332. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2017.01.006

- Hölzel, B. K., Lazar, S. W., Gard, T., Schuman-Olivier, Z., Vago, D. R., & Ott, U. (2011). How does mindfulness meditation work? Proposing mechanisms of action from a conceptual and neural perspective. Perspectives on Psychological Science: a Journal of the Association for Psychological Science, 6(6), 537–559. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691611419671

- Israel Central Bureau of Statistics. (2019). Israel Central Bureau of Statistics. https://www.cbs.gov.il/en/mediarelease/Pages/2019/Population-of-Israel-on-the-Eve-of-2020.aspx

- Jazaieri, H. (2018). Compassionate education from preschool to graduate school. Journal of Research in Innovative Teaching & Learning, 11(1), 22–66. https://doi.org/10.1108/JRIT-08-2017-0017

- Jennings, P. A., Frank, J. L., Snowberg, K. E., Coccia, M. A., & Greenberg, M. T. (2013). Improving classroom learning environments by cultivating awareness and resilience in education (CARE): Results of a randomized controlled trial. School Psychology Quarterly: The Official Journal of the Division of School Psychology, American Psychological Association, 28(4), 374–390. https://doi.org/10.1037/spq0000035

- Jennings, P. A., & Greenberg, M. T. (2009). The prosocial classroom: Teacher social and emotional competence in relation to student and classroom outcomes. Review of Educational Research, 79(1), 491–525. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654308325693

- Kabat-Zinn, J. (2003). Mindfulness-based interventions in context: Past, present, and future. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10(2), 144–156. https://doi.org/10.1093/clipsy/bpg016

- Kenwright, D., McLaughlin, T., & Hansen, S. (2023). Teachers’ perspectives about mindfulness programmes in primary schools to support wellbeing and positive behaviour. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 27(6), 739–754. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2020.1867382

- Kielty, M. L., Gilligan, T. D., & Staton, A. R. (2017). Whole-school approaches to incorporating mindfulness-based interventions: Supporting the capacity for optimal functioning in school settings. Childhood Education, 93(2), 128–135. https://doi.org/10.1080/00094056.2017.1300491

- Lama, D., & Cutler, H. C. (1998). The art of happiness. Hodder & Stoughton.

- Levit-Binnun, N., Arbel, K., & Dorjee, D. (2021). The mindfulness map: A practical classification framework of mindfulness practices, associated intentions, and experiential understandings. Frontiers in Psychology, 12(October), 727857. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.727857

- Longobardi, C., Iotti, N. O., Jungert, T., & Settanni, M. (2018). Student-teacher relationships and bullying: The role of student social status. Journal of Adolescence, 63(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2017.12.001

- Magadley, W., Amara, M., & Jabareen, Y. (2019). Alternative education in Palestinian-Arab society in Israel: Rationale and characteristics. International Journal of Educational Development, 67, 85–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2019.04.002

- Makransky, J. (2007). Awakening through love: Unveiling your deepest goodness. Wisdom publications.

- McCoy, J., & Somer, M. (2019). Toward a theory of pernicious polarization and how it harms democracies: Comparative evidence and possible remedies. ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 681(1), 234–271. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716218818782

- Meiklejohn, J., Phillips, C., Freedman, M. L., Griffin, M. L., Biegel, G., Roach, A., Frank, J., Burke, C., Pinger, L., Soloway, G., Isberg, R., Sibinga, E., Grossman, L., & Saltzman, A. (2012). Integrating mindfulness training into K-12 education: Fostering the resilience of teachers and students. Mindfulness, 3(4), 291–307. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-012-0094-5

- Mendelson, T., Greenberg, M. T., Dariotis, J. K., Gould, L. F., Rhoades, B. L., & Leaf, P. J. (2010). Feasibility and preliminary outcomes of a school-based mindfulness intervention for urban youth. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 38(7), 985–994. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-010-9418-x

- Molloy Elreda, L., Jennings, P. A., DeMauro, A. A., Mischenko, P. P., & Brown, J. L. (2019). Protective effects of interpersonal mindfulness for teachers’ emotional supportiveness in the classroom. Mindfulness, 10(3), 537–546. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-018-0996-y

- Oberle, E., & Schonert-Reichl, K. A. (2016). Stress contagion in the classroom? The link between classroom teacher burnout and morning cortisol in elementary school students. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 159, 30–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.04.031

- Ofek-Shanny, Y. (2020). Validity of majority-minority performance gaps measurements on PISA tests. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3670091 https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3670091

- Pigni, A. (2010). A first-person account of using mindfulness as a therapeutic tool in the Palestinian territories. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 19(2), 152–156. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-009-9328-0

- Rayan, A., & Ahmad, M. (2017). Effectiveness of mindfulness-based intervention on perceived stress, anxiety, and depression among parents of children with autism spectrum disorder. Mindfulness, 8(3), 677–690. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-016-0595-8

- Reches, E., & Rudnicki, A. (2009). The Arab society in Israel: An information file (in Hebrew). The Abraham Fund Initiatives.

- Roca, P., Vazquez, C., Diez, G., Brito-Pons, G., & McNally, R. J. (2021). Not all types of meditation are the same: Mediators of change in mindfulness and compassion meditation interventions. Journal of Affective Disorders, 283, 354–362. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.01.070

- Roeser, R. W., Greenberg, M. T., Frazier, T., Galla, B. M., Semenov, A. D., & Warren, M. T. (2023). Beyond all splits: Envisioning the next generation of science on mindfulness and compassion in schools for students. Mindfulness, 14(2), 239–254. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-022-02017-z

- Roeser, R. W., Mashburn, A. J., Skinner, E. A., Choles, J. R., Taylor, C., Rickert, N. P., Pinela, C., Robbeloth, J., Saxton, E., Weiss, E., Cullen, M., & Sorenson, J. (2022). Mindfulness training improves middle school teachers’ occupational health, well-being, and interactions with students in their most stressful classrooms. Journal of Educational Psychology, 114(2), 408–425. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000675

- Shinwell, M., Cohen, H., Baruch, A., & Nagar, G. (2015). Fostering and utilizing human capital in Israel: The educational system as an engine for socio-economic integration of the Arab society (in Hebrew). The National Economic Council. https://meyda.education.gov.il/files/noar/education_system_as_engine_socioeconomic_integration.pdf

- Sin, N. L., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2009). Enhancing well-being and alleviating depressive symptoms with positive psychology interventions: A practice-friendly meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 65(5), 467–487. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20593

- Spence, S. (1998). A measure of anxiety symptoms among children. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 36(5), 545–566. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7967(98)00034-5

- Tarrasch, R., & Berger, R. (2022). Comparing indirect and combined effects of mindfulness and compassion practice among schoolchildren on inter- and intra-personal abilities. Mindfulness, 13(9), 2282–2298. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-022-01955-y

- Tarrasch, R., Berger, R., & Grossman, D. (2020). Mindfulness and compassion as key factors in improving teacher’s well being. Mindfulness, 11(4), 1049–1061. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-020-01304-x

- Teichman, Y., Bar-Tal, D., & Abdolrazeq, Y. (2007). Intergroup biases in conflict: Reexamination with Arab pre-adolescents and adolescents. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 31(5), 423–432. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025407081470

- Thijs, J., & Fleischmann, F. (2015). Student-teacher relationships and achievement goal orientations: Examining student perceptions in an ethnically diverse sample. Learning and Individual Differences, 42, 53–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2015.08.014

- van Dijk, W., Gage, N. A., & Grasley-Boy, N. (2019). The relation between classroom management and mathematics achievement: A multilevel structural equation model. Psychology in the Schools, 56(7), 1173–1186. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22254

- White, B. P. (2014). The perceived stress scale for children: A pilot study in a sample of 153 children. International Journal of Pediatrics and Child Health, 2(2), 45–52. https://doi.org/10.12974/2311-8687.2014.02.02.4