?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

In 1672 John Eliot, English Puritan educator and missionary to New England, published The Logick Primer: Some Logical Notions to initiate the INDIANS in the knowledge of the Rule of Reason; and to know how to make use thereof (Eliot 1672) The Logick Primer: Some Logical Notions to Initiate the INDIANS in the Knowledge of the Rule of Reason; and to Know How to Make Use Thereof , Cambridge, MA: Marmaduke Johnson]. This roughly 80 page pamphlet introduces syllogistic vocabulary and reasoning so that syllogisms can be created from Biblical texts. The use of logic for proselytizing purposes is not distinctive: What is distinctive about Eliot's book is that it is bilingual, written in both English and Massachusett (Wôpanâak), an Algonquian language spoken in eastern coastal and southeastern Massachusetts. It is one of the earliest bilingual logic textbooks and it is the first, and perhaps only, textbook in an indigenous American language.

In this paper, we (1) introduce John Eliot and the linguistic context he was working in; (2) introduce the contents of the Logick Primer – vocabulary, inference patterns, and applications; (3) discuss notions of ‘Puritan’ logic that inform this primer; and (4) address the importance of his work in documenting and expanding the Massachusett language and the problems that accompany his colonial approach to this work.

1. Introduction

In 1672 John Eliot, English Puritan educator and missionary, published The Logick Primer: Some Logical Notions to initiate the INDIANS in the knowledge of the Rule of Reason; and to know how to make use thereof (Eliot Citation1672). This roughly 80 page pamphlet focuses on introducing basic syllogistic vocabulary and reasoning so that syllogisms can be created from texts in the Psalms, the gospels, and other New Testament books. The use of logic for proselytizing purposes is not distinctive: What is distinctive about Eliot's book is that it is bilingual, written in both English and Massachusett, an Eastern Algonquian language spoken in eastern coastal and southeastern Massachusetts. It is one of the earliest bilingual logic textbooks and it is the only textbook that I know of in an indigenous American language. One thousand copies were printed, funded by Hezekiah Usher under the direction of the Commissioners of the United Colonies in New England (Eliot Citation1904, p. 10); most of these copies (as well as copies of Eliot's other works) were destroyed in the war with Metacom (or Metacomet, also known by his adopted English name King Philip), sachem of the Pauquunaukit, in 1675–76 (Eliot Citation1904, p. 11). When Eliot and the others returned to Natick, Massachusetts, after the war, new editions were printed of his translation of the Bible, and of some of his other works; but not of the Primer. As a result, only a handful of copies have survived, one of which is held in the British Museum (later the British Library), and one in the New York Public Library. The British Museum copy was photographed in 1889 and six copies reprinted from those photographs (Eliot Citation1904, p. 7). In 1903, the bibliographer Wilberforce Eames produced a newly type-set edition of the Primer, which was printed in an edition of 150 copies in 1904. For this paper, we have consulted digitized versions of both the British Museum copy (Eliot Citation1672) and copy no. 39 of Eames's reprint (Eliot Citation1904).

The remainder of this paper is divided into four sections. In §2, I introduce John Eliot and the linguistic context he was working in. Next, I present the contents of the Logick Primer – its vocabulary, inference patterns, and applications (§3). Following that, we consider conceptions of ‘Puritan’ logic that inform the primer (§4). Fourthly, we talk about the importance of Eliot's work in documenting and expanding the Massachusett language and the problems that accompany his colonial approach to this work (§5).

2. Eliot and His Context

John Eliot was born in Widford, Hertfordshire, England, around 1604, and matriculated as a Pensioner in Jesus College, Cambridge, in 1618–19, where he studied languages and graduated in 1622. In 1629, he joined Rev. Thomas Hooker's school at Little Baddow, Chelmsford, as an usher, and it was because of the influence of Hooker that Eliot took orders in the English Church and eventually left for Boston, Massachusetts, in 1631 on the Lyon, accompanied by three brothers and three sisters (Powicke Citation1931a, p. 140). He settled in Roxbury, at the time still an independent town not yet annexed to Boston, and in 1645 founded a Latin school there.Footnote1 In addition to his educational aspirations, Eliot was also a dedicated missionary to the local indigenous people, seeking to convert them to Christianity. In order to successfully do this, he needed to be able to produce sermons in a language that the local people would understand, and this provided the foundation for his linguistic activities. He began to study the indigenous languages in 1644, and preached ‘his first sermon to the Indians in their own language’ on 28 October 1646 (Powicke Citation1931a, p. 141). With the assistance of Cockenoe-de-Long Island,Footnote2 a member of one of the Long Island tribes subjugated to the Pequots (Tooker Citation1896, pp. 9–10), Eliot began translating theological material from English into the local language, including the Ten Commandments, the Lord's Prayer, scriptures and other prayers, and – ultimately – the Bible. The New Testament was published in 1661, and the complete Bible in 1663, produced with the assistance of James Printer, a Nipmuc convert; Job Nesuton, a Praying Indian; and John Sassmon, a former student of Eliot's (Harvey and Rivett Citation2017, p. 443; Rex Citation2011), in a print run of one thousand copies.

This work led to the publication of his The Indian Grammar Begun, a treatise on the theoretical aspects of the Massachusett language, in 1666 (Eliot),Footnote3 and the Nehtuhpeh peisses ut mayut: A Primer on the Language of the Algonquian Indians in 1684, his final work. In 1670, Eliot gave a series of lectures, funded by Robert Boyle (to whom his Grammar was dedicated) and Lady Mary Armine, on logic and theology at Natick which gave rise to the publication of the Logick Primer two years later (Cogley Citation1999, p. 124).

The importance of Eliot's translation work to the preservation of the language cannot be overstated (and we discuss that further in §5), but the central question we must first address is which language is it? Eliot himself, both in his published grammars and in correspondence (cf. Powicke Citation1931a, Citation1931b), often simply calls it an ‘Indian language'. He recognized that there was more than one distinct such language but rarely went so far as to label or name them distinctly; one exception is in his discussion of phonology in the beginning of the Grammar, where he differentiates between what ‘we Massachusets’ pronounce, and what the Nipmuk and the Northern Indians pronounce (Eliot Citation1666, p. 2). It is relevant to note here a footnote in a letter from Richard Baxter to Eliot in 1668, which says: ‘I pray tell me how farre y Indian language reacheth into w

you have translated the Bible and how numerous their languages there are’ (Powicke Citation1931b, p. 446, emphasis added). In replying to this postscript in a letter from 1669, Eliot says that ‘of the number and variety of the dialects, I am not able to give an account’ (Powicke Citation1931b, p. 455), but accompanying this he gives an extremely detailed description of the extent of the various dialectal regions that comprise the language he has been studying and working in. Though it is detailed, it is worth quoting nearly in full (Powicke Citation1931b, pp. 453–454):

A(nswer). Here be 3 q(uestions) (1) for the extent of o(u)r Massachusett or Narraganset language (for these are all one). By an eminent providence of God, the extent thereoff is very large, though not w(i)thout some variation of dialect, yet not such as hindereth a ready understanding of each other[…]It is more y an hundred miles eastw(a)rd fro(m) us to Cape Cod, the utmost extent of o(u)r East(e)rn continent neere us. All these speake o(u)r dialect. The Eastmost Ilands, South East fro(m) us, are Nantuket and Martha's Vinyard. Theire dialect a little varyeth, but they understand us and we y

[…] [in the area] more so(u)therly in long Iland (as we call it) w(hi)ch reacheth to the Dutch Plantation called New York. They speake o(u)r language w(i)th some variation of dialect and some words[…]All the shore continent, as far as the Dutch, have also the same language but w(i)th some variation of dialect. This is more y

200 miles to the South. To returne to Conecticot[…]the neerest p(ar)t of it is about 90 miles (S.W. margin) fro(m) the Massachusetts; and recently (?) I have bene at sundry places, upon y

river, where I taught the Indians and they did p(er)fectly understand the Bible, the Catechisme, and other discourse. They speake o(u)r dialect, or p(rett)y neare. To the northwest are a people called PennywoofFootnote4 Indians about 60 or 70 miles fro(m) us. With them I did very lately this spring converse and they speake o(u)r language with some variation of dialect. To the North and N.E. I have not conversed far, not above 30 or 40 miles, and they use o(u)r language. Only, the furth(e)r North the more they vary. All this (?) I speake upon my owne knowledge. Only, of the most remote places I have the least knowledge. Our language is understood Northward as far as Canada. How far Southward I can(n)ot tell.

Eliot outlines three reasons for the extent of the dispersal of the language, first, because ‘the Massachusetts and Narraganset Sachems have held a very vast imperiu(m) over all parts’ (Powicke Citation1931b, p. 454); second, because Narraganset Bay is ‘the principal, if not the only place in all this country, where y shellfish is found, of w(hi)ch shells they make their jewels and mony of great valewe’ (Powicke Citation1931b, p. 454); and third, the geographical location of the Massachusetts and Narraganset territories abutting the Narraganset Bay (Powicke Citation1931b, p. 455).

This is an extremely detailed and remarkably accurate description of the extent of the eastern branch of the Algonquian family of languages. The Eastern Algonquian subfamily covers languages whose extent goes from the Canadian Maritimes in the north to North Carolina in the south, and it is divided into Abenakian, Southern New England Algonquian, Delawaran, Nanticokan, Powhatan, and Carolina Algonquian. Southern New England Algonquian (SNEA) is itself subdivided into Massachusett, Narragansett, Nipmuc, Quripi-Naugatuck-Unquachog, and Mohegan-Pequot-Montauk. All of SNEA languages are to a large extent mutually intelligible, which is reflected in Eliot's reports of his experiences in his letters, and the fact that his translations were accessible to so many people, though Massachusett shares most similarity with its closest geographical neighbors, Nipmuc and Narragansett (Costa Citation2007).

Modern commentators have given a variety of answers to the question ‘what language was it that Eliot was documenting?’ Gray calls the language ‘Algonquian’ (Citation2003, passim), as does Kim (Citation2012, passim), and Morgan names it ‘Algonkian’ (Citation1986a, p. 106), despite this not naming a single language but rather a family of languages. Miner in (Citation1974) calls the language ‘Natick’ or ‘Natick-Narragansett', which would identify it with one of the branches of Algonquian that went extinct in the middle of the nineteenth century. Kennedy too describes the Primer as ‘written in English and Natick’ (Citation1995, p. 34). However, this appears to be mistaken; instead, we should identify the language with one called ‘Massachusett’ by many modern commentators (Cogley Citation1999, p. 119; Goddard Citation1981, fn. 1; Goddard and Bragdon Citation1988, pp. 492–493), spoken by the several communities whose territories included Roxbury and Boston and spread up and down the eastern and southeastern coasts of Massachusetts. This language, like Natick-Narragansett, came close to extinction in the nineteenth century, but – thanks in part to the documentary material provided by Eliot – has survived and is now spoken by around five hundred or so people as an acquired language, currently called Wôpanâak or Wampanoag. Following Dippold, who notes that ‘Wampanoag, the Native American language once spoken from Provincetown, Massachusetts, to Narragansett Bay, Rhode Island, has gone by a number of names, including Natick, Massachussee and Massachusetts. I use the term Wampanoag because it is the name preferred by the Wampanoag Nation and its members who are trying to revive fluency in Wampanoag’ (Citation2013, fn. 1, emphasis in the original), in this paper, I will use ‘Massachusett’ to refer to the language at the time of Eliot, and ‘Wôpanâak’ when referring to the language as it is spoken today by members of the Wampanoag tribe.

3. The Contents of the Primer

The primer opens with Eliot's definition of ‘logick’ as a rule (Eliot Citation1904, p. 21):

where by every thing, every Speech is composed, analysed or opened to be known.

Anomayag ne kukkuhwheg, ne nashpe nishnoh teag, kah nishnoh keket kaonk, mo

wam

, kah kogáhkenaanum

m

, asuh woshwunum

wahtamunak.

This definition of logic illustrates why Eliot would think it important for the indigenous people to learn logic; for if it is the rule that teaches one how to know speech, then it is fundamental to understanding Christian theology (we return to this point in §§4 and 5).

Eliot then begins the text by dividing logic into three parts. The first comprises what Eliot calls ‘single notions’ (siyeume wahittum

ash) (Eliot Citation1904, p. 22). Examples of the ‘single notions’ that he gives (Eliot Citation1904, p. 23–24) include ‘God’ (God), ‘created’ (ayum), ‘in beginning’ (weskekutchissik), ‘heaven’ (kesuk), ‘earth’ (ohke), ‘not formed’ (matta kukkenauuneunkquttinno), ‘nothing in it’ (monteagwuninno), ‘darkness’ (pohkennum), and so on.

The second part of logic is how ‘bindingly to compose Notions, to make every kinde of Proposition’ (moappissue moehteauunat wahittumukish, ayimunate nishnoh eiayne pakodtittum

onk) (Eliot Citation1904, p. 22). Eliot gives as examples of ‘binding words’ the words in Table (Citation1904, p. 24); other conjunctives are outlined in the Grammar (Citation1666, p. 22), including causatives, disjunctives, discretives, suppositives, exceptives, diversatives, and conjunctions of possibility and of place. What is most striking, from a logical point of view, about the list provided in the Primer isn't even commented on there, but the eagle-eyed reader will note: there is no copula. But Eliot was familiar with this fact–‘a feature of Massachusett which is different from Indo-European languages’ (Guice Citation1991, p. 129), for he had discussed it in his Grammar (Citation1666, p 15):

Table 1. Binding words.

We have no compleat distinct word for the Verb Substantive, as other Learned Languages, and our English Tongue have, but it is under a regular composition, whereby many words are made Verb Substantive.Footnote5

Considering the centrality of the copula in European languages for forming the sort of copular propositions that make up syllogisms, it is surprising that this lack is not mentioned at all in the primer; but then, Eliot is trying to give a practical rather than theoretical account of logic–a fact we do well to remember. If Massachusett can form propositions without an explicit copula, then that's good enough for him.

Using the basic notions he gave as examples and the binding words in Table , Eliot renders the beginning of Genesis in propositional format, translating four statements into the Massachusett vocabulary he has defined and identifying properties of the resulting propositions (Citation1904, pp. 25–26); the sentences are either (1) ‘affirmative general propositions’ (nwae wameyeue pakodtittum

onk) or (2) ‘negative special compound propositions’ (quen

wae nanasiyeue neesepiskue pakodtittumóonk). Clearly these proposition types are not meant to be exhaustive; these are simply the two types that are exemplified in Genesis 1:1–2. But they do show that Eliot is conscious of the importance not only or merely of rendering Biblical propositions into Massachusett, but of understanding the theoretical properties of these propositions, for that is what is relevant when understanding how individual propositions fit together into a wider discourse. The theoretical vocabulary he uses is summarized in Table .

Table 2. Theoretical terms.

The third component of logic is how to take the propositions resulting from combining basic notions with binding words and combine them into larger pieces of discourse or speech, that is, how ‘to compose Propositions, by bonds, binding words, to make a Speech’ (moéhteauunat pakodtittumongash, nashpe moappissuongash, kah moappissue kutt

wongash, ayimunat keket

kontamóonk) (Eliot Citation1904, p. 22). The types of speech that can be produced in this way are twofold. The first is ‘Syllogistical, arguing’ (oggusanuk

wae, wequohtóonk) (Eliot Citation1904, p. 23). The second is ‘Large, orderly discourse’ (sepapwoaeu kohkônumukish keket

kaongash) (Eliot Citation1904, p. 23). These two types are discussed in more detail in part 3 of Eliot's text.

This concludes Eliot's overview of the three parts; he then discusses each part in more detail, as we will too in the next section. A few notes before we do so:

This tripartite account of logic that Eliot uses is traditional, even if his verbiage isn't exactly. The division of the discipline of logic into (1) the study of terms, (2) the study of propositions, and (3) the study of arguments is a historical trope that was already well established in the Middle AgesFootnote6 and gives us an insight into the logical milieu Eliot was educated in (more on this in §4), and Eliot's division far more resembles this scholastic division than it does the Ramist tripartite division into argument, axioms, and disposition (contra Kennedy and Knoles Citation1999, p. 152).

On the other hand, his choice of ‘Basic Notions’ and ‘binding words’ is startlingly atypical, although explainable: As we noted above, it's obvious that the basic notions he gives as examples were chosen because they are the vocabulary of the opening lines of Genesis; these words would be both familiar with the Praying Indians who were the recipients of his earlier translation of the Bible into their language, and also relevant to his overall project of making Biblical truths known to them.

The same can be said of his choice of binding words, but here the matter is more complex: While logicians are generally happy to allow the so-called ‘non-logical’ vocabulary to vary according to specific context or application, it is much more problematic to vary the so-called ‘logical’ vocabulary. The words that Eliot has chosen are a strange collection; some of them are clearly typical logical connectives, such as the copulatives ‘and’ and ‘or', and others fit within a broader logical vocabulary, such as the quantifier ‘another’ or the inference markers ‘for this cause', ‘so’, etc. We discuss this further in §3.2.

3.1. Basic Notions

Eliot says that the basic or single notions come in pairs ‘which inlighten each other, & them only’ (nish wequohtoadtumash, & nish webe) (Citation1904, p. 26), and these pairs are divided into two types, those which ‘agree together’ (weet

oadtum

ash) and those which ‘dissent from each other’ (chachaub

om

ash) Citation1904, p. 27. By way of illustration he gives twenty ‘notional pairs'.Footnote7 Examples of agreeing or consenting pairs include ‘subject’ (noh wadchanuk) and ‘adjunct’ (nene wadchiik), and ‘whole’ (mamusseyeu

uk) and ‘parts’ (chaupag). Sometimes what is paired is not two notions themselves but instead a pair of things picked out by the notion, e.g. ‘equals in quantity’ (tatupukkukqunash), ‘equals in number’ (tatupehtashinash), and ‘like in quality’ (tatupinneunkquodtash) (Eliot Citation1904, p. 28). Dissenting pairs are similar; sometimes they are pairs of dissenting notions, such as ‘more great’ (nano mohsag) and ‘then that less’ (onk ne peasik), and ‘lesser’ (nano peasik) and ‘then that greater’ (onk ne mohsag) (Eliot Citation1904, p. 30). And sometimes they are single notions that pick out pairs of opposing things, such as things that are ‘unlike’ (mattatupinneunkquodtash) or ‘diverse’ (chippinneunkquodtash) or pairs that are ‘contraries’ (pen

anittum

ash) or ‘contradicters’ (pann

wohtoadtuash) (Eliot Citation1904, p. 30).Footnote8

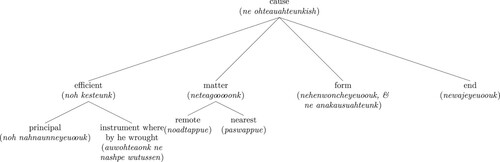

Each pair of consenting or agreeing terms Eliot considers in turn, though it is only the pair ‘cause/effect’ that is given a thorough treatment, covering nearly 7 pages in Eames's edition (Citation1904, pp. 31–38). Eliot provides a typology of the different types of causes, each illustrated with various Biblical examples, mostly from Genesis or Exodus but some from the New Testament. The divisions he introduces, and the language he uses for each type, is given in Figure (Citation1904, pp. 31–38).Footnote9 Similar typological accounts are given of the other consenting pairs (Eliot Citation1904, pp. 40–44) but in much less detail and with fewer Biblical examples worked out.

The same approach is taken with the dissenting notions (Eliot Citation1904, pp. 44–47), unfortunately this time without any discussion, only examples given in the form of Biblical references – unfortunate because here is where we find the notions of ‘contraries, which argue with each other’ (penanittum

ash, nish wequohtoadtum

ash) (Eliot Citation1904, p. 46) and ‘contradicters, which argue each other’ (pann

wohtoadtum

ash, nish wequohtoadtum

ash) (Eliot Citation1904, p. 47), classic technical notions in logic which would have provided us with a clearer picture of how Eliot was using them and in what way he was trying to define them. Where we would have wanted commentary and explanation, we have only example. In fact, for the notion of ‘contradicters', there is only a single Biblical references, to Acts 13:45, which only uses the word rather than defining it or illustrating it.Footnote10

3.2. Creating Propositions

Next, Eliot turns to the second part of logic which ‘teacheth us bindingly to compose Notions, to make every kinde of Propositions’ (kukkuhk tomunkqun moappissue moehteauunat wahittum

ukish, ayimunat nishnoh eiyane pakodtittumo

nk.) (Citation1904, p. 48). Propositions are ‘many fold’ (m

cheke chippaiyeuash) (Eliot Citation1904, p. 48), and can be divided into many types according to whether they are affirmed/negative, true/false, general/special, and single/compounded (Eliot Citation1904, pp. 48–49). A summary of these terms and divisions is given in Table . These four pairs are all traditional and need little comment but this: Where Eliot uses ‘general’ we would modernly say ‘universal’ and where he uses ‘special’ we would modernly say ‘partial’ or (less accurately) ‘particular’; and the single/compound distinction makes it clear that Eliot is operating in a context beyond the pure Aristotelian syllogistic, allowing proposition combinations.

This is also clearly displayed when Eliot subdivides compound propositions into two categories: ‘conjunct propositions’ (moehteaue pakodtittumonk) which are bonded together with words such as kah, wonk, netatup, newutch, etc. (Citation1904, p. 49), and ‘disjunct propositions’ (chachaubenum

e pakodtittum

onk) which are bounded together by ‘a disjoyning word’ such as asuh, qut, matta, etc. (Citation1904, p. 50). He gives John 9:3 ‘Neither he hath sinned nor his parents’ (Matta yeuoh matchesu, asuh

chetuonguh) as an example and provides an analysis of this proposition: It is a ‘negative, special, compound, disjunct proposition’ (quen

wae, nanasiyeue, neesepiskue, chachaubenum

e pakodtittum

onk) (Eliot Citation1904, p. 50). John 9:4–7 are analysed in a similar way.

Despite having considered other binding words, such as quantifiers and causal or inferential markers, when he first introduced the three parts of logic (cf. Table ), Eliot does not here discuss them any further.

3.3. Discourse

Instead, he turns his attention to the third part of logic, which is ‘bindingly to compose propositions to make a Discourse’ (moappissue moehteauunat pakodtittumongash ayimunat keketookontamóonk) (Eliot Citation1904, p. 54). As he noted earlier (Eliot Citation1904, p. 23), discourse or speech comes in two types: (1) ‘syllogisticall’ (oggusanuk

wae) and (2) ‘discursive’ (sepapwoae) (Eliot Citation1904, p. 55), also called (later) ‘methodicall'. We discuss each in turn, as Eliot does.

3.3.1. Syllogisms

Syllogistical discourse is made up out of three components: (1) ‘major proposition’ (mohsag pakodtittumonk), (2) ‘minor proposition’ (pawag pakodtittum

onk), and (3) ‘conclusion inlightened, looked on’ (wequossum

m

uk, naumoom

uk) (Eliot Citation1904, p. 55); this is orthodox, if perhaps a bit fanciful in the description of the conclusion. Furthermore, there can be at most three single notions contained in any syllogism: the ‘subject’ (ne teag), the ‘predicate’ (ne kootnumuk), and ‘the light, or Argument’ (wequohtóonk, asuh ootsinno

nk) (Eliot Citation1904, pp. 56–57). The use here of ‘light’ and related concepts hearkens back to the Augustinian conception of divine illumination as expressed in the Thomist view that reason, ‘placed by nature in every man’ (Aquinas Citation1949, I.1), is the light which guides men towards knowledge. In this specific instance, the wequohtóonk is what would traditionally be called the middle term, that which links the major and the minor premise together, and which is missing from the conclusion. While it was not uncommon for Christian philosophers, especially in the Thomist tradition, and theologians to speak of the ‘light of reason’ (cf. Øhrstrøm et al. Citation2008, pp. 76), Eliot's identification of this light with the middle term is atypical.

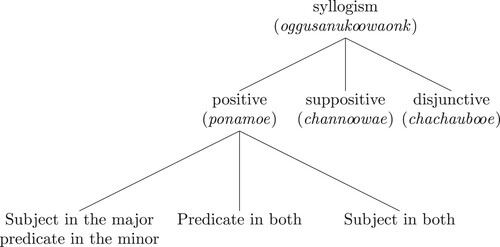

Syllogisms are divided into three forms: (1) ‘positive’ (ponamoe), (2) ‘suppositive’ (channwae), and (3) ‘disjunctive’ (chachaub

e) (Eliot Citation1904, p. 62) (see Figure ).

3.3.2. Positive syllogisms

The positive syllogisms are further subdivided into three categories, depending on the arrangement of the terms (Eliot Citation1904, pp. 62–63):

(1) when the Propositions neither alike begin nor end, because the Argument is the Subject in the Major, Predicate in the Minor Proposition.

pakodtittumongash matta netatuppe wajkutchissinuhhettit asuh wohkukquoshinuhettit newutche wequohtóonk teag

ut mohsag ut, kah ne kootnumuk pawag pakodtittum

onganit.

This is what is otherwise known as the ‘First Figure’ (Eliot Citation1904, pp. 64–65).

(2) when both Propositions alike end; because the Argument is the Predicate in both Propositions.

naneeswe pakodtittumongash netatuppe wohkukquoshinash, newutche wequoht

nk ne k

tnumuk ut na neeswe pakodtitum

onganit.

This is describing the traditional Second Figure (Eliot Citation1904, pp. 66–67).

(3) when both Propositions alike begin, because the Argument is the Subject in both.

neeswe pakodtittumongash netatuppe kutchissinuhettit, newutche wequoht

nk ne teag

ut naneese pakodtittum

onganit.

And this is, of course, the usual Third Figure.Footnote11

Eliot illustrates the concept of syllogism through a series of four examples adduced in the service of giving an affirmative answer to the question ‘Their Infants Believers may they be Baptized?’ (Uppeissesumoh wanamptogig, sun woh kutchessumóog?) (Citation1904, p. 56). An affirmative answer to this question is an affirmative general proposition, with ‘infants of believers’ (uppeissesumoh wanamptogig) as the subject and ‘may be baptized’ (woh kutchessumóog) as the predicate, and the ‘light or argument proceedeth from the Adjunct, Because the Promise belongeth unto them’ (Eliot Citation1904, pp. 56–57). In each syllogism, Eliot identifies the subject and predicate, and either refers to a Bible verse to support the truth of the premises or adduces another syllogism.

Another series of examples is given to illustrate John 9:16, where the Jews ‘falsely opposed Christ, saying, He came not from God, because he breaketh the Sabbath’ (Jewsog pannwae wutayeuukkonouh Christoh, n

wahettit, Matta wutch

m

Godut, newutche pohquenum Sabbath) (Eliot Citation1904, p. 60). The syllogism given in support of this conclusion is (Eliot Citation1904, p. 61):

He that breaketh Sabbath-day cometh not from God. But this man Christ breaketh the Sabbath day. Therefore, &c.

Noh pohqunuk Sabbath-day matta wutch m

Godut. Qut yeuoh Christ pohquenum Sabbath day. Newaj, &c.

Eliot rejects this syllogism by denying the minor premise.

3.3.3. Suppositive syllogisms

Suppositive syllogisms are those where (Eliot Citation1904, pp. 68–69):

In the Major proposition the Argument is suppositively put to the thing proved. Then in the Minor Proposition the Argument is affirmed.

Ut mohsag pakodtittumonganit wequoht

nk chann

wae ponamun ne woh wequohtauom

uk. Neit ut pawag pakodtittum

onganit wequoht

nk n

wae ponamun.

There is no explanation of what is meant by putting the Argument suppositively to the thing proved; instead, he gives the following syllogism as an example (Eliot Citation1904, pp. 69–70):

Table

From this, it is clear that suppositive ‘syllogisms’ are not syllogisms (in the narrow sense) at all but are instances of modus ponens.Footnote12

3.3.4. Disjunctive syllogisms

The description of disjunctive syllogisms that Eliot gives is readily familiar to modern logicians. A disjunctive syllogism is when (Eliot Citation1904, p. 71):

The Major Proposition disjunctively speaketh; then the Minor affirmeth one, denieth the other; or denieth one, affirmeth the other.

Mohsag pakodtittumonk chachaub

ae kutt

m

uk; neit pawag n

wau pasuk, kah quen

au onkatuk; asuh quen

au pasuk, kah n

wau onkatuk.

But what is fascinating here is that none of the examples that Eliot gives straightforwardly match his description; and in fact, on a superficial glance appear to involve fallacious affirmations of the consequent.

Consider the following example, drawing from Matthew 12:33Footnote13 (Eliot Citation1904, pp. 71–72):

On a superficial reading, it looks like this is of the form: ‘Either if your tree is good then your fruit is good or if your tree is bad then your fruit is bad; but your fruit is good, therefore your tree is good', i.e.

which is both clearly not valid and doesn't clearly involve any denial, which one would expect in typical instances of disjunctive syllogism. The two other examples that he gives (Eliot Citation1904, pp. 72–73; 73–74) show a similar pattern:

But to deny one conjunct is to deny the whole conjunction, which forces the other disjunct to be true, which means both of the conjuncts must be true, leading to the seemingly problematic inference from one conjunct to another in a conjunction.

Put schematically, the argument form that all three of these examples instantiate is:

And this is valid.

3.3.5. ‘Methodicall’ Discourse

The second type of discourse, methodical or discursive discourse, comes in two types: ‘First orderly to lay together Notions & Propositions’ (Negonne kohkunumukish miyanumunat wahittumash & pakodtittum

ongash) (Eliot Citation1904, pp. 74–75), and second, ‘to analyse [and] open Propositions [and] Arguments. Also to open Propositions by single Notions, which by composed’ (kogahkenanumunat kah woshwunumunat pakodtittum

ongash kah wequoht

ngash. Wonk woshwunumunat pakodtittum

ongash nashpe syeumoot wahittum

ash, nish nashpe moehteauunash) (Eliot Citation1904, pp. 75–76), and this, Eliot says, is what he most desires to teach the reader, ‘whereby you may open the Word of God, [the] Bible’ (waj woh k

woshwunumw

wuttinn

waongash Godut Bibleut) Citation1904, p. 76.

What follows after this brief explanation is 17 pages (in Eames's reprint; in the original it is about 14 and a half pages) of such methodical discourse, entirely in Massachusett. Even without a translation, the structure of the discourse is clear: A Bible verse is cited, and then a first syllogism is extracted from the verse, followed by one, or sometimes two or three, alternative syllogisms. The source verses cover a wide range across both the Old Testament (Psalms, Proverbs) and the New (Matthew, Romans, 1 Corinthians, 1 John, 1 Peter). With that, the text concludes.

4. ‘Puritan Logic’

The logic primer is an extremely functional book, focusing on definitions and examples with very little in terms of explanation or theoretical background to provide context to the reader. Eliot in his introduction says that ‘these few short Logicall Notions are onely for a Thrid [thread]’ Citation1904, p. 19, and yet, even this one single thread leaves us with many questions: What (if anything) is distinctive about his text (beyond, of course, its linguistic distinctiveness)? How does it fit within the broader context that Eliot was educated and working in? Is it true, as some have claimed (Miller Citation1939; Gray Citation2003), that he was teaching the Indians ‘Puritan logic’? What is Puritan logic – if it is anything at all?

To answer these questions, in this section, we begin with looking at the logical education Eliot himself likely received, whether as a grammar school student or after matriculating at Cambridge; it is only after we have answered this that we can compare what he learned with what he taught.

The dominant tradition in logic through the end of the fifteenth century was Scholasticism, typified by the thirteenth-century manuals of terminist logic of Peter of Spain, William of Sherwood, Roger Bacon, and Lambert of Auxerre (cf. fn. 6), and reaching its culmination in the works of such luminaries as William of Ockham, Jean Buridan, Marsilius of Inghen, and others of the fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries. The technical advances, often motivated by and directed at the solution of logical puzzles in the forms of sophisms and insolubles, which represented the pinnacle of the extra-Aristotelian developments of the Middle Ages, came under increasing scrutiny and ultimate rejection by the newly-bred Renaissance humanists. This rejection was motivated by at least two distinct factors. First, as Ashworth notes, Renaissance humanism ‘turned attention away from those [advanced medieval] grammar and logic texts[…]Late medieval logic texts struck humanists as clumsy, even barbaric, and far too technical in their approach’ (Citation2020, p. 312). The humanists instead preferred a return to the original Aristotle, as well as to newly discovered Greek commentators on Aristotle, who presented a more ‘purified’ approach, unsullied by Scholastic wranglings (Ashworth Citation2020, p. 312). The second factor was ‘the idea that an argument need not be valid in its form to be psychologically persuasive’ (Sgarbi Citation2013, p. 151), which allowed rhetoric to take up a more central place in the practice and teaching of logic–in a more negative characterization of humanism, ‘the discipline of logic[…]was reduced to a mere rhetoric’ (Sgarbi Citation2013, p. 152). By the middle of the sixteenthcentury, humanism had become ‘the primary cultural movement in Britain’ (Sgarbi Citation2013, p. 151).

The treatise that most typified this humanist approach to logic was Rudolph Agricola's De inventione dialectica, written around 1480 and published in 1515 (Jardine Citation1988, p. 181). This book focuses on what can be called ‘applied argumentation', the invention (that is, discovery) of arguments for use in particular circumstances, rather than on the evaluation of abstract forms of arguments and ‘gave wide currency to ancient theory that the two parts of dialectic are invention and disposition’ (Howell Citation1961, pp. 49–50). Agricola's works were widely circulated and revised, especially in England. The earliest English response to Agricola (Howell Citation1961, pp. 49–50), John Seton's Dialectica of 1545, ‘circulated in manuscript for a long time among students and professors at Cambridge before its publication’ and was ‘entirely based on Agricola's logical system’ (Sgarbi Citation2013, p. 152).

The importance of Agricola and his successors, in contradistinction to the earlier Scholastic logicians, is underscored by Henry VIII's Royal Injunction of 1535, which required (clause 7) that (Ashworth Citation2020, p. 317):

students in arts should be instructed in the elements of logic, rhetoric, arithmetic, geography, music, and philosophy, and should read Aristotle, Rodolphus Agricola, Philip Melancthon [sic], Trapezuntius, &c. and not the frivolous questions and obscure glosses of Scotus, Burleus, Anthony Trombet, Bricot, Bruliferius, &c.

We can also find Agricola's central placement in specific guidance in the statues of individual Cambridge colleges, such as the 1551 statues of Clare Hall which required the reading of one of Aristotle's Topics, Analytics, or Sophistical Refutations, or Sturm's Dialecticae partitiones, or Agricola's De inventione in one block of study and Porphyry's Isagoge or Aristotle's Categories or On Interpretation in the next. Similarly, the 1560 statutes of Trinity required the teaching of five different topics: (1) an elementary treatise in dialectic; (2) Porphyry, the Categories, or On Interpretation; (3) the Topics; (4) Agricola, the Sophistical Refutations or the Analytics; and (5) other Aristotelian texts (Ashworth Citation2020, p. 318). Elizabeth I's statues of 1570 narrowed the curriculum further: Rhetoric was to be taught before dialectic, and dialectic should be taught through either the Sophistical Refutations or Cicero's Topics (Ashworth Citation2020, p. 318). The emphasis on the practical use of language and argumentation, and also on the use of beautiful or persuasive language and argumentation, is clear.

From these statutes and syllabuses, we can see that the logic curriculum was not anti-Aristotelian but rather anti-Scholastic, and in fact, ‘for the most part, the logic studied at Cambridge was genuinely Aristotelian, as one gathers from the notebooks and from such manuals as Keckermann's Systema Logicae, Burgersdicius’ Institutionem Logicarum Libri Duo, Heërebord's Annotamenta, and Eustachius of St. Paul's Summa Philosophiae Quadripartia. Still, it was Aristotle resystematized and simplified' (Costello Citation1958, p. 45).

Complementing this humanist wave was another wave of distinctly Protestant logic: the logic of the French Protestant Petrus Ramus (Pierre de la Ramée, 1515–1572). Ramus's work was deeply indebted to Agricola, and Agricola's predecessor and fellow humanist Lorenzo Valla, via the teachings of Johannes Sturm (Howell Citation1961, p. 149; Jardine Citation1988, pp. 184–185; Kennedy and Knoles Citation1999, pp. 148–149). But Ramus rejected the Agricolan entwining of logic and rhetoric (Howell Citation1961, p. 148; Ong Citation1953, p. 239), and also rejected the ‘infra-logical, psychologically elusive play taken into account by the Aristotelian rhetoric’ (Ong Citation1953, p. 239). Instead, his focus was on the simplification of logic to its barest bones.

According to Rechtien, historians Howell and Ong ‘helped establish the common contemporary view that Ramism impoverished logic and rhetoric as arts of communication’ (Citation1987, p. 188). According to Knoles and Kennedy, ‘Ramist logic was not so much a distinctive way of thinking as it was a pedagogical strategy that was influential in a limited range of situations from the late sixteenth to the late seventeenth century’ (Kennedy and Knoles Citation1999, p. 148). The basic idea is that of the five traditional parts of rhetoric (ornamentation; delivery; inventio ‘the recovery and derivation of ideas’; dispositio ‘their organization’; and memory), Ramus assigns only the first two to rhetoric, assigns the second two to logic alone, and replaces the fifth with ‘mental space’ (Rechtien Citation1987, p. 188). This impoverished both logic and rhetoric by stripping rhetoric of its connection to knowledge and truth, and removing logic from the contextual space in which it had previously been located: conversation. Further, on Ong's account, by removing logic from the realm of conversation, Ramus turned logic into a ‘silent thought process’ divorced from oral communication and tied to typography, what both Rechtien and Ong call the ‘hypervisual’ way of thinking (Rechtien Citation1987, p. 189).

This new approach to logic ‘made its appearance in England in fifteen-seventies and ended the reign of scholastic logic as we see it’ (Howell Citation1961, p. 29; Miller Citation1939, p. 118). Ramus's work was extremely influential, particularly in Cambridge (Ashworth Citation2020, p. 310). In the late 1560s or early 1570s, Laurence Chaderton lectured on Ramus's logical works at Cambridge (Rechtien Citation1979, p. 241), and the translations into English of the Dialecticae Libri Duo by Roland MacIlmaine (Citation1574) and Dudley Fenner (Citation1584, White Citation2011, p. 33) helped to cement Ramus's popularity. (Fenner's translation was published anonymously in Middelburg, where he lived ‘after being expelled from Cambridge for Puritanism’ (Hill Citation1997, p. 30), and then died there in 1587, age 30 (Collinson Citation2006, p. 119)).

Which brings us to the final thread woven into the context in which Eliot was educated. The sixteenth and seventeenth centuries saw a shift not only in what was taught but how it was taught, at English and Scottish universities. Teaching at Oxford and Cambridge moved from being university-wide towards narrower, college-based teaching structures (Ashworth Citation2020, p. 309), meaning that the impact of a student's college became more significant in this period. Eliot, as we saw above, was an alumnus of Jesus College, Cambridge. After the English Reformation, Jesus College established itself as an important training site for Protestant clergy, and over the course of the sixteenth century the influence of the Puritans in the Cambridge colleges (with the exception of Caius) grew, so that by the end of the sixteenth century ‘almost every college at Cambridge displayed some evidence of Puritan sentiment’ (Bondos-Greene Citation1982, p. 198). In Jesus College in particular, by the time of the Civil War (after Eliot had already migrated to America), there was a strong Puritan contingent (CitationAnonymous Citationn.d.a). By the seventeenth century, Ramism in England was a well-established and respectable tradition of inquiry and pedagogy (Kennedy and Knoles Citation1999, p. 150).

The picture that we have, then, is of competing accounts of logic, the old Scholastic-Aristotelian, with its focus on terms, propositions, and arguments (or discourse), and the new logic–still ‘Aristotelian’ but with a shift in emphasis–witnessed in two forms, humanist and Ramist, with its focus on the division into invention and judgement. If we are to identify a peculiarly or distinctively ‘Puritan logic’ that is at the heart of Eliot's approach, it is going to be founded on either the humanist tradition (e.g. Agricola and his school) or Ramus. Commentators discussing Eliot's textbook locate the Primer squarely in the Ramist tradition, and often speak interchangeably of ‘Puritan logic’ and ‘Ramist logic'.

There remains a question whether we should uniquely identify Ramist logic as Puritan, in a distinctive or exclusionary sense. Many times when scholars speak of ‘Puritan logic’ or, e.g. the ‘binary logic of Puritanism’ (cf. Gray Citation2003, p. 54) are not actually talking about logic as a formal discipline, but are rather using the term as a synonym for ‘reasoning’ or ‘system of thought'. And while the Puritans certainly took up Ramist and post-Ramist ideas, especially those who went to the New World (Morgan Citation1986a; White Citation2011, p. 30), there does not appear to be anything doctrinally to separate Puritan-Ramism from Protestant-Ramism, especially not at the time that Eliot was a student at Cambridge (White Citation2011, pp. 33, 35, 49). This is true even if Ramism was strongly connected to what Reid calls ‘radical Protestantism, be it Puritan or Presbyterian’ (Citation2011, p. 6).

Even setting apart this question of whether there is anything distinctly Puritan (as opposed to Protestant) about the adoption of Ramist logic, we can still ask whether Eliot's Primer displays any distinctively Ramist characteristics.

On the one hand, a significant number of historians have claimed that that the Primer is Ramist. Miller claims that the Primer is an abridged translation of one of Peter Ramus's writings (Cogley Citation1999, pp. 123–124): ‘The book which Eliot translated for the Indians was Ramus’ Dialecticae reduced to a basic simplicity' (Citation1939, p. 120), while Gray argues that Eliot's book ‘is a pared-down version of [Ramus's] logical structure', describing it as ‘a step-by-step approach to Ramean logical and syllogictical [sic] reasoning’ (Citation2003, p. 136). Kennedy calls the Primer ‘a chopped-up Ramist logic [which] reveals the extent to which Puritans emphasized logic and favored its Ramist form before the mid 1680s’ Citation1995, p. 33, and in later work he (along with Knoles) identifies Eliot's textbook as an example of ‘the new England penchant for humanistic reductionism’ (Citation1999, p. 151). Salisbury joins such commentators when he describes the Primer as ‘based on the Dialecticae of Petrus Ramus’ and reconciling ‘Ramist logic with Puritan piety’ (Citation1974, p. 45). Guice, when discussing Eliot's Grammar (rather than the Primer), argues that Eliot's definitions of ‘logic’ and ‘rhetoric’ in that text ‘show a strong Ramistic pattern’ (Citation1991, p. 126), and argues that this works show Ramist influences, ‘for example, Eliot's heavy reliance on a form of binary classification of features of grammar[…] in real contrast to Aristotelian practices’ (Citation1991, pp. 127–128).

On the other hand, Cogley notes that ‘the linguists disagree as to how Ramist in influence the work is’ and that ‘Miner and Guice have explained that Eliot's Logick Primer was an original composition’ (Citation1999, pp. 123–124). The way to solve this these competing claims is to took a closer look at the actual contents of the Primer. So let us take this closer look at the distinctive features of the Primer, to see how Ramist–or not–they are, and also at the distinctive features of Ramist logic, to see whether they are present in Eliot's Primer. Doing so shows just how un-Ramist it is:

Miller's claim that the book is a reduced version of the Dialecticae is simply false, and can only be explained by attribution to Miller of a fundamental ignorance of both the contents of the Dialecticae and the Primer. For even the most superficial review of both makes two things clear: First, that the contents of the two diverge radically; second, that if any part of the Primer is a translation, it is from Massachusett into English and not vice versa (Miner Citation1974, fn. 16).

According to Morgan, Ramus sought ‘to reduce dependence on the syllogism’ (Citation1986a, p. 106). Eliot, on the other hand, is focused almost exclusively in giving his students the tools they need to build syllogisms. This makes Eliot's treatise very un-Ramist indeed.

As noted above, Guice sees clear Ramist influence in the Grammar, including in that work's definitions of both logic and rhetoric: ‘The laying of Sentences together to make up a Speech is performed by Logick[…] The adorning of that Speech with Eloquence is performed by Rhetoric’ (Eliot Citation1666, p. 5). But the definition of logic in the Primer diverges from this Ramist definition (cf. the definition quoted at the start of §3).

Given the emphasis that Rechtien and others have given to the typographical elements of Ramist and/or Puritan thought (Rechtien Citation1979, p. 236), we can clearly see one way that Eliot's work deviates from that ‘norm'. The only typographically distinctive element of the original 1672 printing is the interlinear structure required by the bilinguality of the text. Most conspicuously, the binary classification strategy that is seen as the hallmark of Ramus's pedagogical strategy (Kennedy and Knoles Citation1999, p. 149; Miller Citation1939, p. 132; Rechtien Citation1979, p. 239; Rechtien Citation1987, p. 207; White Citation2011, ch. 2) is only rarely adhered to in the Logick Primer, as can be seen from the tree diagrams provided in the previous section.

Supposing that Ong, Howell, and Rechtien have the right of it, in their account of Ramus's effect on logic, this is further evidence that Eliot's Logick is not particularly Ramist, as there is little of silent reflection ‘not intended to direct an inner struggle for truth’ (Rechtien Citation1987, p. 189) here; instead, the proselytizing, and hence essentially interpersonal and dialogical, purpose of the book is continually foregrounded.

There is no trace at all of that most important sixteenth-century English division of logic into inventio ‘invention’ and iudicium ‘judgement’ or ‘disposition’ (cf. Howell Citation1961, p. 15). Both Agricola and Ramus emphasize the importance of ‘invention', that is the study of the Topics: and yet, there is no trace of the Topics in Eliot's work (cf. Miner Citation1974, fn. 16).

Further, there is nothing in Eliot's work of the Ramist lex veritatis, lex justitiae, or lex sapientiae (cf. Howell Citation1961, pp. 150–151), or is there any mention of ‘Ramus’ characteristic definition of logic as the art of ‘disputing well’ (Miner Citation1974, fn. 16).

While it is true that Eliot's book is sparse and spare, focusing on examples rather than on precise definitions and details, this simplicity is the only thing it shares with Ramist treatises. One can certainly take the simplicity as evidence that this book belongs in the Ramist tradition, but given that this is pretty much the only shared characteristic, it might behoove us to consider an alternative explanation for the simplicity of his text, namely: The difficulty of expressing the complex ideas of Aristotelian logic in the Massachusett language.

Finally, there is nothing like the ‘Puritan logic’ that some authors locate in Puritan sermons of the time (Rechtien Citation1979) in Eliot's work, either.

What we see instead is a picture of traditional Aristotelian logic, with its division of logic into three parts: Terms, propositions, and discourse (Miller Citation1939, p. 122). Discourse is separated into ordinary and syllogistic, a division which Miner describes ‘quite unlike a Ramist work', and ‘the terminology of syllogistic forms is Aristotelian, not Ramist’ (Miner Citation1974, fn. 16). Additionally, distinctive features of the Primer, such as Eliot's use of ‘the light’ (cf. §3.3.1), find no antecedent in Ramus. Instead, if we compare the contents of the Primer to the contents of one typical mid sixteenth-century student notebook found in a Cambridge manuscript, we see significant similarities (Costello Citation1958, p. 47):

The notebook is arranged according to the threefold operations of the mind: first, the simple idea or concept; second, judgment, where two concepts are joined to form a proposition; and third, reasoning, where two or more propositions are so linked as to arrive at a conclusion.

According to Costello's descriptions of the content of this notebook, concepts are divided into nomen and verbum; judgment includes an emphasis on opposing, equipolating, and converting propositions; and argumentation is divided into two, a priori, or syllogism, and a posteriori, or induction or example (Citation1958, pp. 47–49). While this is not a complete match for Eliot's contents, the similarity is much, much stronger than with any Ramist text.

Despite all this, there is a broad sense in which Eliot's program is thorough-goingly Protestant. Even if he has not adopted the specific logic favored by the Protestants, Puritans included, he did take up their distinct view of the utility of logic: ‘Protestantism was, in one sense, an appeal to logic for the arbitration of belief, since logic alone could interpret the Bible’ (Miller Citation1939, p. 113). This is pretty must the closest that Eliot comes to Ramism, in his logic: He, like Roland MacIlmaine (Rechtien Citation1987, p. 205), believed that that scriptural text is there to be interpreted, and logic is a tool for this interpretation. (Eliot was not alone in his belief in the utility of logic for scriptural exegesis, especially in New England where the intellectual cultural was ‘customarily described as “theological ”, but in practice it was apt to be merely logical’ (Miller Citation1939, pp. 114–115).) This exegetical approach can also be seen in the other aspect in which Eliot's work is clearly in the Ramean tradition, namely, in his extensive use of scriptural examples instead of non-scriptural ones. This use of Biblical examples is not found in Ramus's work; but it does follow Dudley Fenner's translation of Ramus, which replaced all of Ramus's classical references with Biblical ones (Morgan Citation1986b, p. 109). This is part of what Ramist logic more palatable for Puritans – but one would also expect Eliot to have done this even if he wasn't influenced by Fenner, given the application to which he intended his students to put their knowledge of logic.

5. Colonization and Linguistic Conservation

In the foregoing, we have focused on a narrow view of the contents of the Primer and how these contents related to Eliot's wider context – predominantly English and Puritan.

In this section, we draw back and consider the larger picture. On the face of it, the Primer is one small part of a much, much larger endeavor, one designed to provide a written form to a language that had hitherto had none, and to organize it according to sensible grammatical rules, taking the empirical data at face value rather than trying to shoehorn the language into something familiar from Europe and the East; and a project which had a tremendous impact on the language's subsequent history. Due in no small part to Eliot's efforts, the Massachusett language is one of the earliest and best documented languages of the indigenous peoples of the east coast of North America, and one of the only eastern Algonquian languages whose descendant is still spoken today. Eliot's translation of the Bible into Massachusett was not only the first translation into an indigenous American language, but it was also the first one into a language which had hitherto had no written form. The introduction of an alphabet and orthography for the language allowed not only translations of English texts but also that language to be recorded by native speakers, through such works as the Massachusetts Psalter (Citation1709) and documents collected in Native Writings in Massachusett (Goddard and Bragdon Citation1988). As a result, ‘Wampanoag is in the enviable position of having some of the best early records in North America’ (Ash et al. Citation2001, p. 29), and when Jessie Little Doe Baird [also, Fermino] began the Wôpanâak Language Reclamation Project, to ‘return language fluency to the Wampanoag Nation as a principal means of expression’ (CitationAnonymous Citationn.d.b.), there was a wealth of material for her to work with. Guice, writing only thirty years ago, confidently described Massachusett as ‘a now-dead language from an almost-dead branch of a major Amerindian language family’ (Citation1991, p. 134); with the work of Baird and the WLRP, this description is no longer accurate. Seen from this angle, both Eliot's project and its results were an enormous success.

On the other hand, one cannot ignore the proselytizing and colonial context in which he was working. His goal, first and foremost, was to ‘civilize’ the local indigenous people, and then to Christianize them (Rex Citation2011; Salisbury Citation1974), and this goal was to be achieved through language. His linguistic work was wholly directed towards this end. As Eliot says in a letter to Baxter in 1669, ‘And all p'ts w(hi)ch receive the word of God, and pray, doe readyly understand the Bible, and catechisme, and other books; and these books will be a meanes to fix, and extend, this language’ (Powicke Citation1931b, p. 454). The codification of theological and pedagogical material in Massachusett was not merely for the spiritual benefit of the indigenous peoples; language is also an incredibly strong imperial tool, imposing order and structure on the lands and people to be subjugated (Harvey and Rivett Citation2017, p. 449). One cannot separate the linguistic work from the imperial work, here: ‘Eliot's evangelical approach to his religious translations, as well as his language and logic primers, reveals assumptions of cultural and religious superiority which are typical of New England missionary-colonisers’ (Gray Citation2003, p. 119). Furthermore, the introduction of writing systems can also have a homogenizing effect – which was, no doubt, the aim of the early colonists who ‘had hoped to impose a standardized alphabet on all Native peoples’ (Harvey and Rivett Citation2017, p. 443) (this hope was dashed).

By many measures, these conversion efforts were extremely successful: ‘By 1674, only one family of 300 or so Wampanoag families [on Martha's Vineyard] were not practicing the Christian religion’ (though this significantly surpassed the number of converts on the mainland) (Bouck and Richardson III Citation2007, p. 12), and Eliot's linguistic project was also an extremely successful tool in a broader colonial project.

But fixing a language in this way was also to kill it. As Rivett notes, ‘Eastern Algonquian languages [of which Massachusetts is one] are commonly believed to be the language group most permanently destroyed through European contact[…]scholars have amply documented the catastrophic impact of linguistic colonialism in North America’ (Citation2014, p. 554); ‘by 1823 only six Wampanoag could speak their language and in 1821 Zachariah Howwoswee (1736–1821), the last preacher using Wampanoag in his sermons, died. He was also the last Wampanoag who could read publications written in Wampanoag’ (Bouck and Richardson III Citation2007, p. 12). Language loss is itself an intrinsic evil (just as ‘language retention is a human rights issue’ (Hinton Citation2001, p. 5)); but languages are not lost in isolation from the rest of the culture of the speakers. It is ‘part of the loss of whole cultures and knowledge systems, including philosophical systems, oral literary and musical traditions, environmental knowledge systems, medical knowledge, and important cultural practices and artistic skills’ (Hinton Citation2001, p. 5).

As Hinton notes, ‘written documentation freezes and decontextualizes language and language arts’ (Citation2001, p. 241), something that we see exceptionally clearly in the Primer. How many of these words did Eliot construct in an attempt to convey an unfamiliar concept? How many of the words were already common currency in the Massachusett language? How could we even begin to answer these questions? We lack adequate context, both within the book itself, given the lack of self-reflective discussion in the text, and outside of it, as there is nothing comparable to compare it to (and even if there were, it would itself be written and hence face the same issues of fossilization).Footnote14 Any attempt to begin to answer these questions can only be undertaken in conjunction with the people who are closest not only to the language itself but also its cultural context, that is, members of the modern-day Wampanoag tribe; doing so is part of planned future work stemming from the current paper.

Written documentation also leaves us with nothing about the pragmatics of the language, or what we might call the language in its use, a crucial aspect of the deployment of logic in the seventeenthcentury. In the end, ‘we do not save a language by recording it; we preserve it, like a pickle’ (Hinton Citation2001, p. 241)–and pickling preserves precisely because it creates an environment where new growth cannot occur.

If we are to celebrate the survival of the Wôpanâak language through the efforts of the colonizer Eliot and his successors, we must at the same time recognize that the colonizers were also the cause of its doom. We cannot make the inference from ‘Wôpanâak can be reclaimed today because of the work of colonizers in the seventeenth century’ to ‘Without the work of colonizers in the seventeenth century, Wôpanâak could not have been reclaimed’: The correct inference is ‘Without the colonizers, there would have been no need for the language to be reclaimed'.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Jo Edge and Ben Pope who helped me obtain the two articles from the Bulletin of the John Rylands Library and to Andrew Aberdein who alerted me to (Kennedy Citation1995). Earlier versions of this paper were presented at the CUNY Logic & Metaphysics Workshop, the Nordic Logic Colloquium, the Southern Illinois University Logic Seminar, the Durham Philosophy Seminar, the Philosophical Association of the Philippines World Logic Day, and the Australasian Association for Logic, and I'm grateful to the lively discussions that each of these audiences generated. Finally, I'd like to thank my disability support worker, Dan Hamilton, for his assistance in preparing the manuscript for final submission.

Notes

1 Eliot's basic biographical information can be found in ACAD, A Cambridge Alumni Database, https://venn.lib.cam.ac.uk/, accessed 24 January 2023. Note that (Powicke Citation1931a) errs in calling the town Hooker's school was in ‘Little Haddo’.

3 His name derives from the Massachusett verb kuhkinneau ‘he interprets’, and the fact that he was from Long Island (Gatschet Citation1896, p. 217).

3 A new edition of this work was produced by Peter S. Du Ponceau and John Pickering in the early nineteenth century (Eliot Citation1822).

4 That is, the Pennacook.

5 Eliot (Citation1666, p. 16) identifies three types of composition. The first is ‘made by adding any of these Terminations to the word, yeu, a

, o

’. This construction is used with nouns, adnouns [i.e. adjectives], and adverbs, and one example he gives is one that shows up in examples in the Primer: mattayeu

utch ‘let it be nay’. The second sort turns ‘animate Adnouns’ into third-person verbs and the third sort turns active verbs into passive verbs.

6 Cf. the thirteenth-century textbooks of William of Sherwood (Citation1966), Peter of Spain (Citation2014), Lambert of Auxerre (Citation2015), and Roger Bacon (Citation2009).

7 By ‘notional pair’ we should understand ‘pairs of [basic/single] notions’ rather than ‘pairs in name only’.

8 At this point we might pause to marvel at Eliot who feels no compunction at introducing these highly technical pieces of logical vocabulary without definition and without even having introduced the concepts or vocabulary necessary to understand them, such as truth.

9 The first, fourfold division, is, of course, the four Aristotelian causes – formal, material, efficient, and final – under slightly different names.

10 ‘But when the Iewes saw the multitudes, they were filled with enuie, and spake against those things which were spoken by Paul, contradicting and blaspheming’, King James Version (1611), emphasis added.

11 In ignoring the so-called Fourth Figure, Eliot is following logical orthodoxy.

12 Eliot's use of ‘syllogism’ to broadly mean ‘type of argument’ is not uncommon for his period, however, so this is less a comment on his terminology and more a heads up to the reader that one shouldn't necessarily think only of Aristotelian combinations of two categorical premises and a categorical conclusion when syllogisms are mentioned.

13 ‘Either make the tree good, and his fruit good; or else make the tree corrupt, and his fruit corrupt: for the tree is known by his fruit’, King James Version (1611).

14 Some attempts to answer some of these questions with respect to the vocabulary necessary to translate the Bible can be found in Silverman (Citation2005, pp. 159–160).

References

- Anonymous. 1709. The Massachuset Psalter Or, Psalms of David with the Gospel According to John, Boston: B. Green and J. Printer.

- Anonymous. n.d.a. ‘History of Jesus College in the University of Cambridge, 1559–1671’, https://www.jesus.cam.ac.uk/college/about-us/history/1559-1671, Accessed 10 January 2023.

- Anonymous. n.d.b. ‘Wôpanâak Language Reclamation Project: Project History’, https://www.wlrp.org/project-history, Accessed 10 January 2023.

- Aquinas, T. 1949. De Regno (On Kingship), Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies. Edited by Joseph Kenny, transl. G. B. Phelan, Revised by I. T. Eschmann.

- Ash, A., Fermino, J. L. D., and Hale, K. 2001. ‘Diversity in local language maintenance and restoration: a reason for optimism’, in L. Hinton and K. Hale (eds.), The Green Book of Language Revitalization in Practice, Leiden: Brill, pp. 19–35.

- Ashworth, E. J. 2020. ‘Changes in British logic teaching during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries’, History and Philosophy of Logic, 41 (4), 309–30.

- Bacon, R. 2009. The Art and Science of Logic, Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Medieval Studies. transl. T. S. Maloney.

- Bondos-Greene, S. A. 1982. ‘The end of an era: Cambridge Puritanism and the Christ's college election of 1609’, The Historical Journal, 25 (1), 197–208.

- Bouck, J., and Richardson III, J. B. 2007. ‘Enduring icon: a Wampanoag thunderbird on an eighteenth century English manuscript from Martha's Vineyard’, Archaeology of Eastern North America, 35, 11–19.

- Cogley, R. W. 1999. John Eliot's Mission to the Indians Before King Philip's War, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Collinson, P. 2006. ‘What's in a name? Dudley Fenner and the peculiarities of Puritan nomenclature’, in K. Fincham and P. Lake (eds.), Religious Politics in Post-Reformation England, Melton, UK: Boydell & Brewer, pp. 113–27.

- Copenhaver, B. P. 2014. Peter of Spain: Summaries of Logic, Text, Translation, Introduction, and Notes, Oxford: Oxford University Press. With Calvin Normore and Terence Parsons.

- Costa, D. J. 2007. ‘The dialectology of Southern New England Algonquian’, in H. C. Wolfart (ed.), Papers of the 38th Algonquian Conference, Winnipeg, Manitoba: University of Manitoba Press, pp. 81–127.

- Costello, W. T. 1958. The Scholastic Curriculum at Early Seventeenth-Century Cambridge, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Dippold, S. 2013. ‘The Wampanoag word: John Eliot's “Indian grammar”, the vernacular rebellion, and the elegancies of native speech’, Early American Literature, 48 (3), 543–75.

- Eliot, J. 1666. The Indian Grammar Begun: Or, an Essay to Bring the Indian Language into Rules, for the Help of Such as Desire to Learn the Same, for the Furtherance of the Gospel Among Them, Cambridge, MA: Marmaduke Johnson.

- Eliot, J. 1672. The Logick Primer: Some Logical Notions to Initiate the INDIANS in the Knowledge of the Rule of Reason; and to Know How to Make Use Thereof, Cambridge, MA: Marmaduke Johnson.

- Eliot, J. 1822. A Grammar of the Massachusetts Indian Language, Boston: Phelps and Farnham. A New Edition: With Notes and Observations by Peter S. Du Ponceau, LL.D. and An Introduction and Supplementary Observations by John Pickering.

- Eliot, J. 1904. The Logic Primer: Reprinted from the Unique Original of 1672 with Introduction by Wilberforce Eames, Cleveland, OH: The Burrows Brothers Company.

- Fenner, D. 1584. The Artes of Logike and Rethorike, plainlie set foorth in the English tounge, easie to be learned and practised: togither vvith examples for the practice of the same for methode, in the gouernement of the familie, prescribed in the word of God, Middelburg.

- Gatschet, A. S. 1896. ‘John Eliot's first Indian teacher and interpreter. Cockenoe-de-Long Island and the story of his career from the early records by William Wallace Tooker’, American Anthropologist, 9 (6), 2–17.

- Goddard, I. 1981. ‘Massachusett phonology: a preliminary look’, in W. Cowan, Papers of the Twelfth Algonquian Conference, Ottawa: Carleton University, pp. 57–105.

- Goddard, I., and Bragdon, K. J. 1988. Native Writings in Massachusett, Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society.

- Gray, K. N. 2003. ‘Speech, text, and performance in John Eliot's writings’, PhD diss., University of Glasgow.

- Guice, S. A. 1991. ‘John Eliot and the Massachusett language’, in F. Ingemann (ed.), 1990 Mid-America Linguistics Conference Papers, Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, pp. 120–37.

- Harvey, S. P., and Rivett, S. 2017. ‘Colonial-indigenous language encounters in North America and the intellectual history of the Atlantic world’, Early American Studies, 15 (3), 442–73.

- Hill, C. 1997. Intellectual Origins of the English Revolution–Revisited, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hinton, L. 2001. ‘Language revitalization: an overview’, in L. Hinton and K. Hale (eds.), The Green Book of Language Revitalization in Practice, Leiden: Brill, pp. 3–18.

- Hinton, L. 2001. ‘New writing systems’, in L. Hinton and K. Hale (eds.), The Green Book of Language Revitalization in Practice, Leiden: Brill, pp. 239–50.

- Howell, W. S. 1961. Logic and Rhetoric in England, 1500–1700, New York: Russell & Russell.

- Jardine, L. 1988. ‘Logic and language: humanistic logic’, in C. B. Schmitt, Q. Skinner, E. Kessler, and J. Kraye (eds.), Cambridge History of Renaissance Philosophy, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 173–98.

- Kennedy, R. 1995. ‘Aristotelian and Cartesian logic at harvard: Charles Morton's A Logick System & William Brattle's Compendium of Logick’, Vol. LXVII of Publications of the Colonial Society of Massachusetts, The Colonial Society of Massachusetts.

- Kennedy, R., and Knoles, T. 1999. ‘Increase Mather's ‘Catechismus Logicus’: a translation and an analysis of the role of a Ramist catechism at Harvard’, Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society, 109, 145–81.

- Kim, D. H. 2012. ‘By prophesying to the wind, the wind came and the dry bones lived’: John Eliot's Puritan ministry to New England Indians', PhD diss., University of Edinburgh.

- Lambert of Auxerre. 2015. Logica Or Summa Lamberti, Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press. transl. T. S. Maloney.

- Makylmenæus, R. 1574. The Logicke of the Moste Excellent Philosopher P. Ramus Martyr, Newly Translated, and in Diuers Places Corrected, After the Mynde of the Author, London: Thomas Vautroullier dwelling in the Blackefrieres.

- Mather, I. 1999. ‘Increase Mather's ‘Catechismus Logicus’ (1675), Translated and edited by Rick Kennedy and Thomas Knoles’, Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society, 109, 183–223.

- Miller, P. 1939. The New England Mind: The Seventeenth Century, New York: The MacMillan Company.

- Miner, K. L. 1974. ‘John Eliot of Massachusetts and the beginnings of American linguistics’, Historiographia Linguistica, 1 (2), 169–83.

- Morgan, J. 1986a. Godly Learning: Puritan Attitudes Towards Reason, Learning, and Education, 1560–1640, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Morgan, J. 1986b. Puritan Attitudes Towards Reason, Learning and Education, 1560–1640, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Ong, W. J. 1953. ‘Peter Ramus and the naming of methodism: medieval science through ramist homiletic’, Journal of the History of Ideas, 14 (2), 235–48.

- Powicke, F. J. 1931a. ‘Some unpublished correspondence of the Rev. Richard Baxter and the Rev. John Eliot, “The apostle to the American Indians”, 1656–1682’, Bulletin of the John Rylands University Library, 15 (1), 138–76.

- Powicke, F. J. 1931b. ‘Some unpublished correspondence of the Rev. Richard Baxter and the Rev. John Eliot, “The apostle to the American Indians”, 1656–1682 (Continued from p. 176)’, Bulletin of the John Rylands University Library, 15 (2), 442–66.

- Rechtien, J. G. 1979. ‘Logic in Puritan sermons in the late sixteenth century and plain style’, Style, 13 (3), 237–58.

- Rechtien, J. G. 1987. ‘The Ramist style of John Udall: audience and pictorial logic in puritan sermon and controversy’, Oral Tradition, 2 (1), 188–213.

- Reid, S. J. 2011. ‘Andrew Melville and Scottish Ramism: a re-interpretation’, in S. J. Reid and E. A. Wilson (eds.), Ramus, Pedagogy and the Liberal Arts: Ramism in Britain and the Wider World, Abingdon, UK: Routledge, p. 21.

- Rex, C. 2011. ‘Indians and images: the Massachusetts Bay colony seal, James Printer, and the anxiety of colonial identity’, American Quarterly, 63 (1), 61–93.

- Rivett, S. 2014. ‘Learning to write Algonquian letters: the indigenous place of language philosophy in the seventeenth-century Atlantic world’, William and Mary Quarterly, 71 (4), 549–88.

- Salisbury, N. 1974. ‘Red Puritans: the “Praying Indians” of Massacusetts Bay and John Eliot’, William and Mary Quarterly, 31 (1), 277–54.

- Sgarbi, M. 2013. ‘Ralph Lever's Art of Reason, Rightly Termed Witcraft (1573)’, Bruniana & Campanelliana, 19 (1), 149–63.

- Silverman, D. J. 2005. ‘Indians, missionaries, and religious translation: creating Wampanoag Christianity in seventeenth-century Martha's Vineyard’, William and Mary Quarterly, 62 (2), 141–74.

- Tooker, W. W. 1896. John Eliot's First Indian Teacher and Interpreter, Cockenoe-de-Long Island and the Story of His Career from the Early Records, New York: Francis P. Harper.

- White, J. 2011. The Invention of the Secondary Curriculum, London, UK: Palgrave MacMillan.

- William of Sherwood. 1966. William of Sherwood's: Introduction to Logic, Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press. transl. N. Kretzmann.

- Øhrstrøm, P., Schärfe, H., and Uckelman, S. L. 2008. ‘Jacob Lorhard's ontology: a seventeenth century hypertext on the reality and temporality of the world of intelligibles’, in P. Eklund and O. Haemmerlé (eds.), Conceptual Structures: Knowledge Visualization and Reasoning, Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Conceptual Structures, ICCS 2008, Vol. 5113 of Lecture Notes in Computer Science, Berlin: Springer, pp. 74–87.