?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

We present how the theory of reasoning developed by Tadeusz Czeżowski, a Polish logician and a member of the Lvov-Warsaw School (LWS) can be applied to the mediaeval texts which interpret the Bible, which we collectively call as Biblical exegesis (BE). In the first part of the paper, we characterise Czeżowski's theory of reasoning with some modifications based on remarks of Kazimierz Ajdukiewicz. On these grounds, we discuss the nature of reasoning and its different types, as well as the problem of textual representation of reasoning. In the second part, we describe the analytical nature of some BE at the end of twelfth century and in the thirteenth century by referring to the examples of Stephen Langton, Robert Grosseteste, Bonaventure, Albert the Great and Thomas Aquinas. We argue that they represented an analytical approach in BE, characterised by advanced use of logic and specific methods, including reasoning reconstruction and logical analysis. In the third part, we present selected examples to show how Czeżowski's framework helps in identifying various types of reasoning. We indicate some universal problems with the textual representation of reasoning found in the BE of the authors in question. Lastly, we point out how Czeżowski's framework enables the understanding of phenomena such as ‘Special Biblical Inference’. Thanks to this experiment, we can see how a framework as advanced as that offered by LWS representatives can be put to the test using mediaeval Biblical commentaries, yielding interesting results.

1. Introduction

In this article, we are going to apply the theory of reasoning developed by Tadeusz Czeżowski, a Polish logician and a representative of the Lvov–Warsaw School (LWS), to selected examples of mediaeval Biblical exegesis (BE).Footnote1 We claim that this theory was a very important achievement in the history of logic in a broad sense. We intend to show how it copes with the analysis of such a special material as selected fragments of mediaeval Biblical commentaries.

Although it seems that mediaeval theologians are very far from twentieth-century logicians, we will argue that the application of the LWS framework to this special material gives particularly interesting results. At the same time, we will present some examples showing how mediaeval commentators apply logic to analyse the Bible. In our opinion, this is also a relevant part of the history of logic. Although the topic of this study may seem to be rather narrow, we would like to contribute to a general debate on thinking about reasoning from the logical perspective.

Recent years have seen an increased interest in the issue of argumentation both theoretically and empirically. Much attention has been paid to the definition of argumentation, the distinction of its types, the ways it functions in different contexts, as well as the preparing of corpora of texts or the analysis of examples for teaching purposes. Despite this, many issues and pathways remain unexplored and questions unresolved. The focus on one type of reasoning, which is argumentation, can be seen as one of the limitations. Another would be the focus on contemporary texts – often of a specific nature, that is, whose discursive nature was subordinated to utilitarian purposes. Next, the lack of adequate reflection defining the relationship between reasoning as a process and its textual representation. The application of Czeżowski's theory of reasoning to mediaeval BE will serve us to expose the lesser-known and less frequently addressed aspects of the issues in question.

First of all, it is not only argumentation that appears in BE. Because the aim of BE is to propose an interpretation of a given passage, the main kind of reasoning being deployed is explanation. Second, due to the specific nature of the commentaries, one can find some distinctive examples of inferences, such as Special Biblical Inference and Inference from Names. Third, textual manifestations of different kinds of reasoning are quite problematic. Because of the pragmatic nature of the utterance's illocutionary force, it is not always clear what kind of reasoning is being employed in a given passage.

In what follows, we will characterise Czeżowski's theory of reasoning as our methodological framework. Theories of reasoning were developed by subsequent LWS generations. We will concentrate on the elements of the most mature versions of this theory formulated by Tadeusz Czeżowski but we will add some elements of Ajdukiewicz's theory to it, which will allow us to put more precisely the categories proposed by Czeżowski. On these grounds, we will discuss the nature of reasoning and its different types, as well as the problem of textual representation of reasoning. Next, we will describe the most interesting trends in BE at the end of twelfth century and in first eight decades of the thirteenth century: we will refer to the examples of Stephen Langton, Robert Grosseteste, Bonaventure, Albert the Great and Thomas Aquinas to argue that they represented an analytical approach in BE, characterised by advanced use of logic and specific methods. Then we will show selected examples of various types of reasoning and indicate some universal problems with textual representation of reasoning found in the BE of the authors in question. Lastly, we will indicate how Czeżowski's framework enables the understanding of phenomena such as Special Biblical Inference.

2. Czeżowski's Theory of Reasonings from 1952

2.1. General Overview

Usually, the term ‘philosophical school’ denotes a group of philosophers who share certain beliefs. What is common for the members of the LWS, however, is their methodological attitude, which is based on two main postulates: of clarity and of justification. As Twardowski himself stated it was these methodological framework postulates, not a substantive content which defined the School established by himFootnote2 :

the main characteristic of this School is in the formal–methodological domain: it is based on striving for the greatest possible precision and accuracy in thinking and expressing one's thoughts as well as on the most exhaustive justification of what is said and the correctness of proof.

The LWS is mainly known for the achievements of Alfred Tarski, Jan Łukasiewicz and Stanisław Leśniewski in formal logic; however, the realisation of methodological postulates was also served by the theory of definitions and the theory of reasoning (Brożek et al. Citation2020, 94–236, 237–287). In the case of the latter, the representatives of the LWS formulated an original treatment of the categories known as deduction, induction and abduction in Peirce's (Citation1978) terms.

There is a lot of reflection on the notion of reasoning undertaken by members of the LWS. There are many papers devoted to this problem, most important of which are by Twardowski (Citation1901), Łukasiewicz (Citation1934, Citation1961), Ajdukiewicz (Citation1922, Citation1955, Citation1957, Citation1974), Kotarbiński (Citation1966), Salamucha (Citation1930), Czeżowski (Citation1946, Citation1952), Bocheński (Citation1954). For a broader review and summary of the main strands of the discussion on the category of reasoning in the LWS, see the works of Kwiatkowski (Citation1993) and Jadacki, Tałasiewicz, and Tędziagolska (Citation1997) Here, we will focus on spotlighting the most important aspects of this discussion and the theory of reasoning itself, leaving out many nuances and idiosyncrasies for the sake of sketching a coherent framework, which we will use later in the paper.

A core element of any theory of reasoning is the definition of reasoning. Twardowski defined reasoning as ‘the mental operations by means of which we assert that there is a relation of reason to consequence between two or more propositions’ (Twardowski Citation1901, 29).

As one can easily see the genus proximum for ‘reasoning’ is ‘mental operation’. Twardowski's definition manifests a very typical feature of his approach, that is, the pragmatism of combining psychological, linguistic and logical aspects (cf. van der Schaar Citation2016). Following this approach, Ajdukiewicz (Citation1957, 64–65) proposed another definition of reasoning:

To reason means, on the basis of some accepted sentences (propositions) to accept a new, not yet accepted sentences (propositions), or on the basis of some accepted sentences to strengthen the certainty with which we accept other sentences. Accepted sentences, on the basis of which we come to accept another sentence or to strengthen the degree of its certainty, are called premises (premissae), and the sentence, which we come to accept by inference, is called a conclusion.

These two definitions illustrate the pragmatic approach adopted in the LWS based on several distinctions between actions and their products, psychological and logical aspects of reasoning, and different aims of psychological and logical inquiry. They introduce several basic concepts, such as mental operation, reason, consequence, inference, premise, conclusion. Although these categories are well known and well established in the field of logic, as we shall see, they are also understood in different ways.

Czeżowski (Citation1952) presented one of the most mature approaches to dealing with different kinds of reasoning. It was based on ‘traditional’ – as he himself claimed – distinctions of the elements of reasoning: reason – consequence, premise – conclusion, and starting point – target (Czeżowski Citation1952, 128). Although the first two distinctions seem fairly familiar, the distinction between starting point and target can be a little obscure and not so obviously ‘traditional’. We will recall a certain way of explicating these categories in the following section, in addition to offering a new way of conceiving them. Unfortunately, Czeżowski did not provide any definitions of these categories (he treats it as a task to be done in future studies) but he indicates selected philosophers and scholars that endorsed three main opposing pairs of kinds of reasoning (Czeżowski Citation1952, 128): deductive – reductive reasoning (Aristotle, Sigwart), heuristic – justifying reasoning (Aristotle, Descartes, Hoefler), progressive – regressive reasoning (Jevons, Kotarbiński).

What is important, these six kinds of reasoning can be defined using the aforementioned categories, specifically by identifying different categories with each other in the scope of the given reasoning (Czeżowski Citation1952, 129):

deductive: premise = reason, conclusion = consequence,

reductive: premise = consequence, conclusion = reason,

heuristic: starting point = premise, target = conclusion,

justifying: starting point = conclusion, target = premise,

progressive: starting point = reason, target = consequence,

regressive: starting point = consequence, target = reason.

It is worth noting that these three divisions: deductive – reductive, heuristic – justifying and progressive – regressive, are not independent. From any two types of characteristics, one can infer the third one, for example: deductive and heuristic reasoning is also progressive.

Based on the distinctions cited, four types of reasoning are defined (Czeżowski Citation1952, 130):

inference: deductive, heuristic, progressive reasoning,

proving: deductive, justifying, regressive reasoning,

explanation: reductive, heuristic, regressive reasoning,

testing: reductive, justifying, progressive reasoning.

Czeżowski's classification of reasoning is summarised in Table .

Table 1. Classification of reasoning according to Czeżowski, with the starting point underlined and the target italicised.

Importantly, Czeżowski's approach can be regarded as a structural one (cf. McKeon Citation2013, 285); however, the subsequent markers in a way mimic the processual nature of reasoning with its functional aspects.Footnote3

After this brief exposition of the elements of Twardowski's, Ajdukiewicz's and Czeżowski's ideas, let us proceed to point out some implications of their approach.

2.2. Implications and Considerations

It is worth noting that according to Ajdukiewicz (Citation1974), the very same syllogism – that is, the same set of sentences expressing reason and consequence – can serve as a basis for various kinds of reasoning, for example: for both proving and explaining. Let us consider Ajdukiewicz's example (Ajdukiewicz Citation1974, 442):

Any physical body which is generically lighter than water floats on it.

Ice is generically lighter than water.

hence:

Ice floats on water.

In the case of proving (or argumentation), (a) and (b) serve to justify (c), that is, to offer support for (c). We can present the reasoning in standard form:

Reason 1.1: Any physical body which is generically lighter than water floats on it.

Reason 1.2: Ice is generically lighter than water.

Consequence: Ice floats on water.

In the case of explanation, (a) and (b) serve to explain (c), that is, they express the hypothesis why (c) occurs, they indicate its cause or a general law and antecedent conditions (cf. the Deductive-Nomological Model of Explanation). The standard form of this reasoning can be the same as in the previous case, because (a), (b) and (c) are connected by the relation of logical consequence:

Reason 1.1: Any physical body which is generically lighter than water floats on it.

Reason 1.2: Ice is generically lighter than water.

Consequence: Ice floats on water.

Now let us return to the question: what is a starting point and how does it differ from a premise? Jadacki, Tałasiewicz, and Tędziagolska (Citation1997, 7) identify the starting point with what is given and the target with what is sought but they do not propose any definitions for these categories, probably treating them as primitive terms. We believe that one can offer a very interesting and intuitive interpretation of the starting point of reasoning by adopting Ajdukiewicz's (Citation1955) idea of the question leading our reasoning. In the case of proving, the starting point is at the same time the conclusion and consequence of the reasoning. The question leading our reasoning in this case is: ‘Is the consequence true?’ Or, in another formulation: ‘Does the fact expressed in the conclusion hold?’ Premises offer a reason for the truth of the consequence being the conclusion and target of the reasoning. Let us put it schematically:

Proving:

Is c true?

(P1) If R, then c.

(P2) R.

Therefore: c.

In the case of explanation, the consequence of the reasoning is at the same time its starting point and its premise. The question leading our reasoning this time is: ‘Why the consequence?’ Schematically:

Explanation:

Why c (occurs or holdsFootnote4 )?

(P1) c.

(P2) If R, then c.

Therefore: R.

Similarly, the leading question for inference can be: ‘What follows from the adopted reasons?’ (so the starting point are: reasons). And for testing: ‘Are these reasons true?’ (so the starting point are again: reasons).

We think that the explication of the starting point in terms of the question leading our reasoning is very compelling. However, we are not sure whether there is any intuitive interpretation of the target other than complement to the starting point or what is sought in the given reasoning.

In the case of inference, the question leading our reasoning could be: ‘What must be true if R is true?’ Or: ‘What follows from R?’ In the case of testing, the question leading our reasoning is: ‘Is R true?’ This very last example is similar to proving and shows the importance of the identification of the role of the element given in question: ‘Is it a conclusion or reason?’

To sum up, the leading questions and the starting points for each type of reasoning can be presented as follows:

inference: What follows from R? (starting point: R),

proving: Is c true? (starting point: c),

explanation: Why c (occurs or holds)? (starting point: c),

testing: Is R true? (starting point: R).

What is interesting, the reconstruction of the types of reasoning involving the starting point understood as a question leading our reasoning is in line with other contemporary approaches offered, for example, by Urbański and Pietruszewski (Citation2019). The authors show that an important part of Sherlock Holmes's reasoning may be modelled in terms of Inferential Erotetic Logic, in particular Erotetic Search Scenarios (Urbański Citation2009, 75–76).Footnote5 We are not going to present the details of this approach here but let us note that the crux of it is an observation that we need to include some erotetic components to give a full account of reasoning involved in real problem solving. In the case of Czeżowski's theory of reasoning, this erotetic component is quite thin but essential and conceptualised as the question leading (guiding) our reasoning.

A very natural question in this context is how abduction relates to the presented division. This varies depending on the adopted definition of abduction but it seems that from the perspective of the LWS theory of reasoning, abduction is a compound type of reasoning (Urbański Citation2009; Urbański and Pietruszewski Citation2019, 87). As Urbański and Pietruszewski note, abduction consists of both generation and evaluation of hypotheses, so, to put it in terms used in the LWS conceptual framework, it can be seen as a combination of explanation and testing. It can be also noted that in the evaluation phase, the testing of prospective hypotheses involves deductive reasoning in the form of eliminating false hypotheses.

Let us also note that there are various possible relations between reasoning (as a process or result) and text. For example, text (utterance) reports on reasoning when the reasoning is performed prior to the given utterance – in this case, the utterance recalls the reasoning. However, it expresses reasoning when it was performed at the same time as the given utterance was performed – then, the reasoning or inferential structure underlying it is the content of the utterance.

Reasoning indicators (such as because, therefore) in texts indicate the relation between the premise(s) and conclusion and can serve as a marker helping to identify the reasoning expressed in the text and its type. Very often other parameters necessary for defining the kind of reasoning – such as reason and conclusion or starting point and target (provided by the question leading the given reasoning) – are underspecified. Probably, such underspecificity could be described in terms of indirect speech acts, that is, speech acts where illocutionary force is not expressed linguistically (Searle Citation2011).

Contemporary approaches to the relationship between reasoning and text very often focus on argumentation and offer simpler terminological frameworks than the one established by the LWS. They often identify argumentation with reasoning (as a general category, at the terminological level) and reason with premise (ignoring categories of starting point and target). Indeed, various types of reasoning expressed in texts tend to gravitate towards proving (or argumentation) – especially inference and testing – and explanation. Even an explanation can be conceived as a kind of argument: argument to the best explanation, when we provide some enthymematic premises (Harrell Citation2016, 29). Supposedly, these phenomena can be grasped by an account based on conversational rules (Grice Citation1989) as they seem to exploit the maxim of relation (relevance), for instance: that an example of inference is offered to persuade someone, so it can be perceived as an example of argumentation (can be ascribed the illocutionary force of argumentation).

Although the matter requires more in-depth examination, we would be inclined to see several advantages of the LWS account over Anglo-Saxon ones. First, Czeżowski's approach offers a rich and intuitive terminological framework. Second, it is not reductive, that is, it does not reduce explanation to argumentation (proving), while Anglo-Saxon approaches reduce explanation to an inference (or argumentation) to the best explanation (cf. Harrell Citation2016, 29). Third, it offers a clearer and more fine-grained account for abductive reasoning as abductive reasoning is a complex reasoning consisting of explanation and testing. Fourth, Czeżowski's approach can serve as a basis for a clear account for the distinction between argumentation and explanation in terms of speech acts or textual phenomena. It enables distinctions between deep logical structures (kinds of reasoning) and shallow textual ones (speech acts) open to pragmatic influences. Capturing the relationships between them would contribute to the development of a unified view. Some insights concerning these issues will be shown through the examples presented in the following sections.

3. Analytical Biblical Exegesis in the Thirteenth Century

3.1. General Remarks

In thirteenth-century BE, we can find interesting and sometimes surprising traces of an analytical approach. We have observed the most impelling examples of this approach in the commentaries of four theologians: Robert Grosseteste, Albert the Great, Bonaventure of Bagnoregio and Thomas Aquinas. We decided to include in our research also Stephen Langton, who preceded them in applying this approach in his exegetical works composed at the turn of the thirteenth century.

Albert the Great and his student Thomas Aquinas are well-known theologians and philosophers from the Dominican Order, who provided a new doctrinal basis for theological studies which included new trends in philosophy. Bonaventure, who after his academic career in Paris was elected as minister general of the Franciscan Order, played a similar role in his community. Robert Grosseteste, known for his metaphysics of light, was an important master and an organiser of academic life for the University of Oxford. He started a new thread in the history of Western methodology. Notably, he was the first Western Latin scholar to comment on the Analytica posteriora, the most influential methodological work composed by Aristotle. What is more, he combined the knowledge from this work with the metaphysical framework taken from Aristotle and his commentators from the Muslim cultural circle, including Ibn Sina (Avicenna), Ibn Gabirol and Ibn Rushd (Averroes) (Polloni Citation2021). In addition, he drew attention to the role of experiment and the use of mathematics in the scientific method. The first two points were also shared by Albert, Bonaventure and Thomas, who all adopted Aristotelianism and developed it in their philosophy and theology. This Aristotelic import was a strong factor shaping their thinking about the methodology of sciences and in this way influenced their analytical approach.

However, it was not the only factor. This is why we can find such an approach in the texts of such a predecessor of thirteenth-century scholars as Stephen Langton. For this reason, we decided to include his works in our sample. Langton was a prominent Parisian master of theology who composed his works at the turn of the thirteenth century, as has already been said. He is known as a commentator of the whole Bible, the first commentator of Peter Lombard's Sentences and recently identified as an author who significantly influenced the Summa aurea of William of Auxerre (Quinto and Bieniak Citation2014, 6–7), which, after Peter Lombard's Sentences, was the most important theological textbook of the thirteenth century.

The analytical approach is not a common feature of BE, as it is mostly focused on unpacking the senses of the Scripture, and different hermeneutical methods can be applied to reach this goal. The analytical approach is generally associated with discussions on theological problems which assume inference of theological statements or proving them in a rigorous methodological manner (e.g., five ways of proving the existence of God in Aquinas's Summa theologiae or numerous arguments in his texts called ‘discussed questions’). However, we have noted that in the cases of Stephen Langton, Robert Grosseteste, Albert the Great, Bonaventure of Bagnoregio and Thomas Aquinas, this approach is also present in their BE.

We have chosen a sample of a few Biblical commentaries of each of those five authors which in our opinion contain the most interesting analyses. The most distinct elements of what we call the analytical approach identified in the Biblical commentaries of those authors are: (1) advanced reasoning, (2) logical analysis, (3) reasoning reconstruction, (4) metaphysical approach, (5) exegetical techniques, such as division of the text (divisio textus).Footnote6 For the purposes of this article, we focus on the first three elements. They will be presented below.

3.2. Examples

Let us now consider a few examples which show how analytical mediaeval BE was. The first one is a fragment of Stephen Langton's analysis of the passage from the Gospel of Luke 7:47. We should note that Langton conducted his analysis as part of a discussion which has been included (according to old indexes) in a collection of his texts known as Quaestiones theologiae (Theological Questions). Critical editions of these questions are still being published in subsequent volumes since 2014. In general, Langton's theological questions represent the part of theological activity which, in the Middle Ages, was called disputatio. It was focused on discussing theological problems and it was distinguished from the activity centred on exegesis, called lectio (literally: reading). However, Langton's Theological Questions include a few questions which seem to combine the two roles: they contain discussions as well as provide exegesis of selected Biblical passages. Question 78, in which Langton comments on Lk 7:47, is one of them.Footnote7

Lk 7:47 contains a part of Jesus Christ's response to a Pharisee, who invited him to dinner. This response refers to a sinful woman who regretted her sins, came to the Pharisee's house and wet Jesus's feet with her tears, ‘wiped them with her hair, kissed them and poured perfume on them’ (cf. Lk 7:38). The Pharisee remarked that if Jesus were a prophet, he would know that she was a sinner, and so Jesus told him a parable about two debtors and a moneylender who forgave them the debts, and asked ‘Which of them will love him more?’ The Pharisee answered: ‘I suppose the one who had the bigger debt forgiven’, and Jesus accepted this answer. However, he then turned towards the sinful woman and said something which seems inconsistent with what was said earlier. Let us quote this passage (Lk 7:47) according to the modern English translation, modified in some places in order to be closer to the Vulgate (we add the Latin counterpart of the key connective on which Langton focuses): ‘Therefore, I tell you, her many sins have been forgiven, as (quoniam) she loved very much. But whoever has been forgiven little loves little’.

Langton formulates two inferences based on this passage (which he later refers to):

Whoever has been forgiven more, more can be expected of that person, therefore, cancelling a debt is the cause of love. Moreover, the Lord accepted the response ‘Whoever has been forgiven more, loves more’; therefore, it follows that it was inappropriate to say ‘Her many sins have been forgiven, as (quoniam) she loved very much’. This is because love is given here as the cause of remission, while first it was remission that was given as the cause of love.Footnote8

We have underlined the phrases which indicate that the quoted fragments are inferences or argumentations. We call such phrases ‘reasoning indicators’. We can see that two of them reveal that conclusions are being drawn from premises and in the last step the indicator marks another premise for the conclusion.

The first reasoning represents an interpretation of Jesus's words. However, the conclusion seems contrary to a theological statement according to which God's love cannot be conditioned by anything external to him. The second one points out an inconsistency between Jesus's statements. In the first statement, forgiveness is a cause of love, which is an effect, whereas in the latter, it is the other way round. It is because the cause–effect relationship is set up by the connective ‘as’ (quoniam), which seems to indicate a cause for what was said before the connective. Langton gives the following brief response to this problem (we have marked the crucial part in bold type):

Love is given here as a sign of love, as here: ‘Greater love has no one than this’ (John 15:13), etc., and this is the meaning: greater love is a sign of greater love. And the word ‘as’ (quoniam) or ‘because’ (quia) has an ostensive, and not a causal function.Footnote9

We can see that Langton restores the correct cause–effect relationship. He shows that the woman's love is not a cause of forgiveness but it is a sign of the love she experienced. He also refers directly to the connective ‘as’ (quoniam) and another similar one, ‘because’ (quia), to explain that its function can be different from what it usually is, namely: an ostensive one, instead of a causal one. Thus, in this situation ‘quoniam’ indicates or introduces a sign, not a cause, Langton claims.Footnote10 In the same discussion, he also presents similar examples of utterances which can be found in other Biblical passages in which the connectives enim and nam (‘for’) play a similar role.

Next, in the same discussion, although concerning the issue of proper reasons for the sinful woman's love, Langton formulates short proofs, and he explicitly indicates that he treats them as proofs. He uses phrases like ‘having proven …’ (demonstrato) or he marks them with the word ‘proof’ (probatio). Finally, he assesses such proofs and judges whether they are valid or not, and if not, he determines whether it stems from falsity of premises (in this case he shows that one of the premises is false) or whether there is a formal error called non sequitur.Footnote11 Langton's example reveals that, when commenting on the Bible, he identifies reasonings in the texts, and that he formulates reasonings which are a possible interpretation of what is said in the Bible. We can also see that he checks if the statements he finds in the Bible are consistent. And, finally, he analyses the connectives and their functions. Next, he formulates possible proofs of important discussed statements and assesses them by analysing their elements (premises) and the inference. His logical analysis of the Scriptures appears to be highly advanced. Furthermore, we should emphasise that in this case this analysis is a crucial part of the performed BE.

Let us now give an example from a Biblical commentary composed by Bonaventure, to broaden the scope of presentation of analytical tools used by mediaeval commentators. The example presented below refers to John 6:56–57. This passage contains the following utterance of Jesus Christ: ‘Whoever eats my flesh and drinks my blood remains in me, and I in them. Just as the living Father sent me and I live because of the Father’. Let us quote the most important part of Bonaventure's interpretation of these wordsFootnote12 :

And he gives this reason why his flesh is true food that nourishes and gives life: The person who abides in me lives on account of me. Now the person who eats my flesh abides in me. Therefore, the person who eats my flesh lives on account of me. He first provides the minor proposition (minorem) for his reasoning in what follows: (…).

This time we have underlined the elements which show that Bonaventure reads Christ's utterance as a reasoning and that he makes an attempt to reconstruct it. First, he points out that Christ gives a reason for the analysed statement. Second, he tries to paraphrase the utterance of Christ and suggests it is a reasoning by using the indicator ‘therefore’ (ergo). Third, he explicitly indicates the minor premise in Christ's reasoning; thus he uses logical terminology to analyse the Scriptures. Finally, he calls it ‘reasoning’.

A few sentences later he states that ‘[h]aving stated the minor proposition’ (minorem), Christ ‘adds the proof for the major proposition’ (probationem maioris), and finally, that Christ ‘manifests this in a simile’ (in simili). Hence, Bonaventure again calls it a proof, again speaks about the minor proposition, and this time he also indicates a major one. Finally, he notes that one part of Christ's reasoning is similar to a previously presented part of this reasoning, so he points out the analogy between these two parts.

This example shows that a mediaeval theologian is capable of using the logical instrumentary to identify elements of the text which are relevant from a logical point of view and to analyse the Scriptures, and that he indeed uses this instrumentary for these purposes.

Lastly, let us give an example of advanced reasoning from Aquinas's commentary on the Gospel of John 14:11Footnote13 :

He says, I am in the Father and the Father in me, because they are one in essence. This was spoken of before: ‘I and the Father are one’ (10:30). [Because] We should note that in the divinity essence is not related to person as it is in human beings. [For] Among human beings, the essence of Socrates is not Socrates, because Socrates is a composite. But in the divinity, essence is the same with the person in reality, and so the essence of the Father is the Father, and the essence of the Son is the Son. Therefore, wherever the essence of the Father is, there the Father is; and wherever the essence of the Son is, there the Son is. Now the essence of the Father is in the Son, and the essence of the Son is in the Father. Therefore, the Son is in the Father, and the Father in the Son. This is how Hilary explains it.

In this quote, we have underlined the reasoning indicators, and we have added some of them when they were lacking in the English translation, based on their counterparts in the original text in Latin. The quote presents a long and complicated reasoning, which is, however, clearly composed. According to the indicators, its first part provides premises, and the second part leads to subsequent conclusions. At the end of this reasoning, we can find an advanced syllogism, which is based on the substitution of one element for another, namely, the essence of a divine person for this person. This syllogism is valid from a logical point of view. Moreover, it does not represent a simple use of one of the traditional syllogistic modes but it proposes a not-obvious transition based on the above-mentioned substitution, and thus, it testifies to the use of quite an advanced logical apparatus by the author.

We can find more such examples in the works of other theologians. Nevertheless, it seems that these three are enough to show the presence in BE of such elements of the analytical approach as: (1) advanced reasoning which transcends standard syllogistics, (2) logical analysis including identification of relevant elements of reasoning and its assessment, (3) perceiving the textual phenomena as embedding deeper logical structures and striving for their reconstruction.

4. Application of the Lvov-Warsaw School Framework to Mediaeval Biblical Exegesis

4.1. Reasoning Identification

The LWS framework is very useful in identifying particular kinds of reasoning conducted as part of BE. Let us consider an example from Robert Grosseteste's Hexaëmeron, a commentary on the first part of the Book of Genesis containing the description of the creation of the world, in which Robert proves that God is a trinity. The reasoning starts with the following sentences (we underline the reasoning indicator)Footnote14:

The fact that God is trinity of persons follows from the fact (inde sequitur) that God is light:Footnote15 not bodily light but non-bodily light. Or rather, perhaps, neither bodily nor non-bodily, but beyond either. Every light has by nature and essence this characteristic, that it begets its splendor from itself.

The whole reasoning is very long, but there is no need to quote it in extenso. It is enough to present the beginning, where we can see the main claim and the first part of its justification, including two basic premises: the one stating that God is light, and the one which refers to the characteristics of every instance of light. The statements that follow are generally inferred from the two basic premises to finally support the main claim.

This quote can be assessed using Czeżowski's classification of reasonings. The preceding parts of Grosseteste's text leave no doubts that the leading question of this reasoning is: ‘Is God a trinity of persons?’ Thus the starting point is: ‘God is a trinity of persons’. This starting point is a conclusion, whereas the subsequent statements are the target, and at the same time the premises, as has already been noted. Detailed analysis makes it possible to see that the starting point and the conclusion are a consequence, while the target, and so the premises, are reasons. It is then easy to identify this reasoning as proving.

We can also refer to Czeżowski's other categories and characterise this reasoning as regressive, justifying and – due to its formal correctness, which we have verified in the whole passage – deductive. Along with Czeżowski's theory, this characteristic is another way to the conclusion that this reasoning is an example of proving.

The application of Czeżowski's classification forces us to carefully analyse the reasoning and judge which element is the conclusion and whether it is a consequence or a reason. This is a matrix which guards us from escaping these difficult questions by saying that it is just an instance of argumentation. Thanks to this precise analysis and identification of reasoning, we can accurately characterise such an enterprise as Grosseteste's argumentation for the trinity and assess its result. It does make a difference to know if a reasoning is formally correct, and thus infallible, or if it should be identified as fallible. In the first case, we only need to discuss the validity of premises, to make sure whether we can accept the conclusion or not. In the latter, the reasoning can still be a strong support for a claim, but even if we accept the premises, we cannot be sure if the conclusion is true. For the example from Hexaëmeron, it is crucial whether the reasoning constitutes proving (and is thus infallible) or explaining (which is fallible).

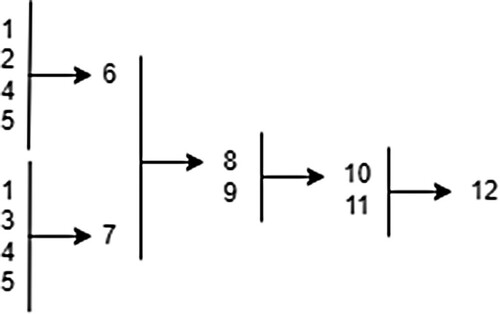

To precisely identify reason–consequence relationships and assess the logical correctness of each step it is important to carefully reconstruct such a reasoning.Footnote16 Having analysed the text, we have a set of basic statements (propositions) with their numbers: (1) ‘God is light’, (2) ‘From the nature and essence of the light it follows that it generates its splendour’, (3) ‘The light and its splendour necessarily embrace each other and breathe a mutual fervour’, and so on (there is no need to list them all here, since we only want to give a general idea of the process). The last statement is at the same the final conclusion, marked as ‘12’: ‘There are three persons and not more in God’. It is equivalent to the sentence ‘God is trinity of persons’ which – as we can see in the quote above – Grosseteste claims to prove. If we examine the relationships between the sentences, we learn from the text that (4) and (5) are additional premises which together with (1) and (2) give (6), and that, similarly, with (1) and (3) they give (7); next, one can see that according to Grosseteste, (6) and (7) together give (8). In the next step, he adds (9), which is a definition necessary to obtain (10). Finally, he adds (11), which is related to the nature of light again, to (10) and gets the main conclusion, (12). Based on such an analysis, a diagram can be drawn (see Figure ).

A we have pointed out, according to Grosseteste the starting elementary reasonings ( and

) are analogical, and this is why they differ only in one premise (incidentally, Bocheński's (Citation1948, 444) theory of analogy is also a very useful tool in such analyses). Using such a tree diagram, we can examine step by step the correctness of each elementary reasoning. Logicians and philosophers often formalise them to check their validity. We will not go into details as it is not so important here. Let us just mention that we have checked the subsequent steps and that they seem correct, with one important comment, which will be developed in the next section: very often such reasonings need to be supplemented with some additional (or: hidden) premises, as is the case here.

Let us move on to another example, which illustrates a different type of reasoning. The previously analysed passage came from Chapter 3 of Book 7 of the Hexaëmeron, whereas the next one opens Chapter 2 of the same book and at the same time it starts the discussion about an interpretation of God's words such as ‘let us’ and ‘our’ in the utterance ‘let us make man to our image and our likeness’ (Gen 1:26). Grosseteste writesFootnote17:

In the consignification of the plural number of this verb ‘let us make’ and of the pronoun ‘our’, we have suggested to us the plural number of persons in the one God. For it is God who is speaking. Therefore there is one who is speaking, and another, or others, to whom (singular or plural) he says ‘let us make’ and ‘our’.

It is difficult to find in the text any indication which would help us to define the leading question. However, we could assume that this question is: ‘Why is there a plural number in God's utterance “let us make man to our image and our likeness?”’ It seems natural in the case of a text which is composed to comment on another text, to treat reasoning built around the text being commented on as an example of explanation (indeed, interpretation of a text is a kind of explanation and is based on the formulation of hypotheses).

In this case, there is no need to argue about what is articulated in the authoritative text. The intention clearly seems to be the search for possible hypotheses which provide reasons for using plural forms in the text. Thus, according to Czeżowski's classification, such a reasoning can be identified as an explanation; the consequence is ‘In Genesis we read “let us make man to our image and our likeness”’, and the reason: ‘There is the plural number of persons in the one God’. In such cases – examples of reductive reasoning – there is no need to evaluate the validity of reasoning for it is fallible ex definitione, but we are able to resort to other criteria for reasoning evaluation, for example: elimination of alternative hypotheses, hypothesis testing or some additional heuristics, such as conservativeness of the hypothesis and its coherence with our convictions.

4.2. Universal Problems with Textual Representation of Reasoning Found in Biblical Exegesis

The analysis of reasoning expressed in natural language often faces serious problems when we want to examine the formal correctness of such a reasoning or to identify what kind of reasoning it is. We encountered some of them during the analysis of reasoning present in mediaeval BE. We will discuss three examples below.

Sometimes, and it is not a very rare phenomenon, mediaeval thinkers create perfect syllogisms, which are ready to be presented in a formal way. Let us quote Albert the Great's Summa theologiae, just to give a brief example: ‘Everything that is in no way in potentiality is in no way changeable. What is most true is in no way in potentiality; God is most true; therefore he is in no way changeable’.Footnote18

Albert combines two perfect syllogisms, both in the Barbara mode. We do not need to either add or specify anything here. The structure is clear. It is easy to identify the reason–consequences and premises–conclusion relationships. Hence, without a doubt it is a formally correct inference.

Nevertheless, it is often the case that such inferences or proofs are not precise enough. Then the first kind of problems appears. To present such a reasoning in a formal way, first we need to reformulate it. To give an example, let us quote a fragment from Grosseteste's proof presented above (this fragment is represented as a connection of [8] and [9] which entails [10]): ‘There is in God, then, someone, and someone else, and a third someone [8], each of whom is an individual substance of rational nature [9]: thus, three persons [10]’.Footnote19

In this case, we should first reformulate the second premise, (9), to get, for instance: ‘Someone, and someone else, and a third someone in God are individual substances of rational nature’, or, better: ‘Someone is an individual substance of rational nature, someone else is an individual substance of rational nature and a third someone is an individual substance of rational nature’. We should also supplement (10) and present it as, for example, ‘There are three persons in God’.

In this situation, such an operation does not seem controversial, as we can be sure that we are not adding any new information and not interpreting it, but we are only putting the same content in different words. However, it may be that to reformulate a statement expressed in natural language some interpretation is needed. Let us briefly consider the following example from Aquinas's De potentia dei: ‘it is written: every breathing I have made (Is 57:16), and by breathing, we are to understand the soul. Therefore, seemingly, the soul is created by God’.Footnote20

To provide a formal representation of this reasoning, we need to reformulate this Biblical passage to get, for instance, the following sentence: ‘Every breathing is created by God’. However, it is an interpretation, which assumes that when God says that he has made a breathing, it means that it was created by him. Next, it is necessary to interpret the second premise and to decide whether it is a categorical statement or a definition. It does make a difference for further assessment. It seems that the latter option is closer to the text; however, it is, again, burdened with interpretation. Finally, the conclusion lacks a quantifier, and so we need to decide whether it applies to every soul. It seems almost obvious, as the first premise includes the general quantifier. However, we should also take into account the context of the text in which this reasoning has been presented. In q. 3, art. 9 of De potentia dei Aquinas speaks about the soul in general, and this is why he does not use a quantifier. We have to decide, then, whether to translate it into a plural form and add a quantifier, or to leave it as it is.

Another problem are shortcuts in reasoning expressed in natural language. This issue arises when authors skip some obvious statements or seem to treat some sentences as equivalent. In such situations, we need to supplement a reasoning with such hidden premises. Sometimes they are obvious and not controversial, and so their absence does not affect the quality of the reasoning and does not pose any major problem in the assessment. Let us go back to the quote from Grosseteste's proof. He draws a conclusion, (10), from the two premises: (8) and (9). However, at least one premise is missing. Grosseteste must have assumed that his readers know and accept Boethius's definition, according to which ‘a person is an individual substance of a rational nature’.Footnote21 Nevertheless, without including this definition it is not possible to reach (10). So to get the final form of this reasoning, we must include this definition.

Finally, we can indicate a more general problem, which is related to the nature of exegesis itself. The aim of exegesis is to explain a text. In the case of the Bible, the commentator's task is to unpack and present various senses of the Scriptures, both literal and spiritual (allegorical, moral, anagogical). The commentator is expected to give accurate hypotheses which indicate how the text should be interpreted. So the commentator gives possible reasons for the sentences they comment on. It seems that the leading question for such reasoning is ‘Why q?’, for q – the sentence being commented on, which at the same time is a consequent in the implication ‘If p then q’, reflecting a reason–consequence relationship. The answer to such a question is ‘Because p’. Thus it seems that the main kind of reasoning in Biblical commentaries is explanation. However, sometimes the commentator shows a reason for q, but it is not his intention to explain why q, but to prove that q is true. Hence, the leading question (as defined by Ajdukiewicz) would be ‘Is q true?’ To prove it, they find a true sentence, p, from which q can be inferred. According to such an interpretation, it is not explanation, but proving.

Are we always sure what leading questions underlie a reasoning? Sometimes the author's intention is clear. But unfortunately, it is not a rule. Let us consider a short quote from a longer reasoning provided by Aquinas in the commentary to John 14:10: ‘He says, I am in the Father and the Father in me, because they are one in essence’.

In this case, it seems that Aquinas answers the question ‘Why did Jesus say that he was in the Father and the Father in him?’ One of possible reasons is that Jesus and the Father are one in essence. However, we can also assume that Jesus's words are put into question, and Aquinas provides a proof which supports them. It does not necessarily mean that Thomas assumes that Jesus could have lied. It could be questioned whether we should take those words literally, so: ‘Is it literally true that…?’

What is the author's intention? Is it explaining or proving? The context of Jesus's utterance convinces us that Jesus spoke those words to his disciples to emphasise that there was no need to ask him to show them the Father, as his disciple Phillip had done, because if one sees the Son, they also see the Father. So this was the reason to say ‘I am in the Father…’ and so on. Why did he say that? Because Phillip asked to be shown the Father, but – as Jesus claims – it is unnecessary. On these grounds, we can argue that it was not needed to find another reason for Jesus's words. So this time Aquinas wanted to prove that Jesus's words were true in a literal sense. However, it is not clearly stated using words such as ‘let us prove it’ or ‘a proof’, as it happens sometimes, and so the doubts remain. Perhaps Aquinas did not want to prove it, but only to show what exactly Jesus meant by his words. It is then a matter of interpretation.

The example discussed above shows a situation in which the commentator reconstructs a reasoning found in the Bible. However, Biblical commentaries also include reasonings which refer to purely theological statements. Unfortunately, they are often beset with the same problem. Let us consider the fragment from Grosseteste's Hexaëmeron:

The fact that God is trinity of persons follows from the fact that God is light: not bodily light but non-bodily light.

What does the author want to tell us? It is possible that he asks ‘Why God is trinity?’, and tries to give a reason for this statement. But we cannot exclude that he intends to prove that God is a trinity. In this case, we can argue that the structure of the reasoning shows that it was meant to be deductive, and the form of the reasoning itself convinces us that it was intended to be a proof. However, again, it is an interpretation. We need to assess it. And, unfortunately, in some cases we have to decide or leave it unsolved.

To sum up: textual representation of reasoning sometimes makes it difficult to judge what intention underlies such a reasoning, and in consequence: what kind of reasoning it is. Hence, it also influences its status, because it is then difficult to judge whether it is deductive (infallible) or reductive (fallible).

4.3. A Helpful Tool for Understanding Phenomena Such as Special Biblical Inference

Let us now consider an example of reasoning in BE which comes from Stephen Langton's commentary to 2 Chronicles 24:17–18: ‘After the death of Jehoiada, the officials of Judah came and paid homage to the king, and he listened to them. They abandoned the temple of the Lord’.Footnote22

Langton points out that the story presented in this passage contains an argument which shows how helpful good companions can be. Next, he conducts his inferences and concludes with the following words (we underline the reasoning indicators):

By this it follows that it is very good for those in power to have an honest man by their side, whose presence they respect, because out of respect for him they will often refrain from doing evil. Hence (unde) in Ecclesiasticus: Stand in the multitude of the elders; and cleave unto him that is wise. And next: And if thou seest a man of understanding, get thee betimes unto him, etc.

The last indicator, which is ‘hence’ (unde), seems to mark an inference. It means that one of the sentences before ‘unde’ (probably the statement: ‘it is very good for those in power …’) is a reason and a premise, whereas the one after ‘unde’ is a consequence and a conclusion.

However, the in-depth analysis of this case shows that the relationship between these two sentences is problematic. Can such a general statement (let us call it ‘statement’) be a reason for a Biblical sentence which is quoted (let us call it ‘quote’), and can a Biblical sentence be a conclusion, as the sacred text should not be put into question? We can argue that such a statement expresses some objective truth, and so (in consequence) it is included in the Bible. But we can also claim that sometimes we know something because we learned about it from the Bible, and so the quote is a reason for knowing the truth expressed in a statement (which is a conclusion). In such an epistemological perspective: we know that p is true, because we know from the Bible that p or that r, such that .

Our preliminary corpus study confirmed that this kind of inference is very common in the commentaries we have analysed. It is always paired with ‘unde’, which appears after a general statement and after which we have one or more Biblical quotes, often taken from various books of the Bible. We call it ‘Special Biblical Inference’ (SBI). A general scheme of such a reasoning is: [statement] unde [quote/quotes]. The questions posed in the paragraph above can be posed to all such cases. Let us show another example, this time from Albert the Great's commentary on Is 7:14Footnote23 :

[…] he [God] does not dissolve the community which he has united with such delight. Hence it is said (unde dicitur) in the same place [Prov. 8:30]: ‘[I] was delighted every day’. Exod. 3:15: ‘The God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob, (…) This is my name for ever’. Rev. 21:3: ‘Behold the tabernacle of God with men, and he will dwell with them. And they shall be his people; and God himself with them shall be their God’. Ez. ult. 48:35: ‘The name of the city from that day: The Lord is there’. Is. 62:4: ‘Thou shalt no more be called Forsaken: and thy land shall no more be called Desolate: but thou shalt be called My pleasure in her, and thy land inhabited. Because the Lord hath been well pleased with thee: and thy land shall be inhabited’.

In this example, we can see how long the string of quotes given after ‘unde’ can be in SBI. It seems that each quote should be interpreted separately, and so they do not need to be linked, but each of them alone would be sufficient to establish SBI. It is very important especially when we want to interpret quotes as premises or reasons, to know if all the premises together are necessary or whether it is enough to have a single one; similarly with premises.

As we have already mentioned, in the case of SBI, it is not certain whether the statement is a reason or a consequence, and similarly with the quote. In our opinion, it is also difficult to identify the pragmatic role of particular cases of SBI. It could be defined by a leading question. We can assume that such a question is: ‘What follows from the statement?’ This would mean that the content of a Biblical quote follows from the statement which is often a conclusion of a reasoning. But at the same time, we can take into account the possibility that the leading question is ‘Is the quote true?’ Thus the statement could prove the content of a quote. However, if the quote is not a consequence, but a reason, then the statement does not prove the content of a quote, but only confirms it as part of testing the statement. Finally, we should take into account the option that the leading question is ‘Why the statement?’, and, thus, the quote would be one of possible reasons for the statement; it would mean that it is a kind of explanation.

Hence, we can see that in the case of SBI, we find another advantage of using the framework provided by Czeżowski. It enables us to consider SBI in the light of different leading questions and create a complete map of possible options according to which we can interpret it. They are presented in Table .

Table 2. A map of interpretative options for Special Biblical Inference, with the starting point underlined.

In our opinion, if a particular text or its interpretation does not exclude any of these options, all four possibilities are on the table. We assume that the most intuitive (and thus: default) interpretation is still: inference. For this reason, we call it ‘Special Biblical Inference’. However, in particular cases, we are never sure whether the statement is a reason and the quote a consequence, and which (or what) leading question underlies such a specific reasoning. For these reasons, we also take into account the interpretation that all the possibilities are coherent and can be included together. It can mean that the statement and the quote are equivalent, and that all four leading questions meet their answers here. However, it can also mean that SBI is simply vague and we are not able to decide what is what, and what problem it is actually intended to solve.

Both interpretations seem to be related to the nature of theology, which embraces both systematic theology and the Biblical one (Roszak Citation2021, 16–17; Roszak Citation2022, 4–5; Jamieson and Wittman. Citation2022, xvii–xviii). One of the aspects of this nature is the fact that doctrinal and Biblical statements are entangled in many ways. Sometimes one is a reason for another which is its consequence. However, sometimes the latter may form an argument together with a new one, which supports the first one. Sometimes one elucidates another. And sometimes one is a consequence; however, in the next step it elucidates its reason, and so there is a kind of circle or a helix. At the same time, although we can be sure that a particular theological statement or a quote is true, we can always ask questions about them, and get additional support and a deeper understanding thanks to linking it to another quote or statement. Such an entanglement produces an impression that the whole system is self-explanatory, and that the Biblical sentences and the theological sentences support each other, which goes in line with the mediaeval exegetical technique to explain Scripture through Scripture.

5. Conclusion

Let us sum up the results of this study. We have shown that Czeżowski's framework is a tool which enables the exploration of many layers of textual phenomena in terms of their logical content. It offers a very intricate, ordered and, after some additional elaboration, intuitive way of thinking about reasoning and its kinds. For these reasons, we think it is a really important and not fully appreciated achievement in the history of logic sensu largo. However, we have also presented some problems with the interpretation of a pair of key concepts of this theory, namely, ‘starting point’ and ‘target’, and we have pointed out the most promising solution.

We have shown that Czeżowski's framework is useful in the study of reasoning in analytical mediaeval BE which can be characterised, first of all, by: advanced reasoning, logical analysis, and reasoning reconstruction. This framework helps in the precise identification of reasonings in BE and it seems that it is better suited to this task than other frameworks which do not clearly distinguish between deductive and reductive reasonings or abandon this distinction while dealing with texts. It is also a very effective tool for clarifying the phenomena of special kinds of reasoning which appear in BE. For example, it enables discussion about the vague nature of SBI.

However, the application of Czeżowski's framework is not always straightforward. The study of relations between texts and the reasoning structures is challenging for at least a few reasons. It is sometimes difficult to identify the status of particular sentences (for instance, whether they are definitions or something else). Very often reasonings have omissions, and it is difficult to judge whether some hidden premises are obvious, and should be simply added, or not, meaning that adding them would modify the reasoning too much. Sometimes we cannot be sure about the author's intentions, and it can affect the identification of his reasoning. Thus it is often the case that analysis must be preceded by difficult decisions with respect to interpretation.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 For the sake of simplicity, by Biblical exegesis we understand the set of texts which interpret the Bible. When we add an adjective ‘mediaeval’, we restrict this set to the texts written in the Middle Ages. However, we admit the term ‘Biblical exegesis’ can also have other meanings which are not bound by such a nominalist interpretation.

2 (Twardowski Citation2014, 47–48) unless indicated otherwise, all translations from Polish are our own.

3 A very similar account was offered independently two years later by Józef M. Bocheński (Citation1954) published in English in 1965:

In the first place, reduction, like deduction, can be subdivided into a progressive and a regressive type. In both cases, the consequent is known to be true, but not the antecedent; if the reduction is to be done progressively, however, the antecedent – whose truth-value is still unknown – is taken as the starting-point, from which the argument proceeds to the known or ascertainable consequent. This progressive reduction is called ‘verification’. Regressive reduction, on the other hand, begins with the known consequent and proceeds to the unknown antecedent. Regressive reduction is called ‘explanation’ (Bocheński Citation1965, 92).

4 As Ajdukiewicz (Citation1974, 442) notes, the question ‘Why?’ can be ambiguous: ‘To substantiate the second qualification that an answer to a ‘why?’ question may not always be called an ‘explanation’ in accordance with the everyday linguistic usage note that if a person claims a statement of his to be true and we think that he does so without sufficient grounds, then we sometimes ask him, ‘Why should it be so as you claim?’, but what we expect in reply is not an explanation of what is stated, but a substantiation of the statement claimed’.

5 We would like to thank Leonard Kupś for bringing these issues to our attention.

6 The metaphysical approach can hardly be found in Langton's text; it is represented by other authors, as it is connected with the metaphysical turn which took place in the thirteenth century and with the above-mentioned reception of Aristotle's works in the Latin West. See an example of the use of the metaphysical approach in Biblical exegesis of John 1:1 carried out by three of the above-mentioned theologians in Nannini and Trepczyński. Citation2022. The division of the text is a technique which became popular and flourished in the middle of the thirteenth century in Paris (Even-Ezra Citation2017; Covington Citation2017; Rossi Citation1994), so it is not surprising that we can find it in the commentaries of Albert, Bonaventure and Thomas. According to this technique, before an author starts commenting on the text, they present the main parts of the text and indicate their functions in the whole work, and next for each such part they perform a similar subdivision. Thus, this method ascribes a specific role to each element of the work, and at the same time it creates grounds for an interpretation of the whole as a system created out of such elements. If we compare those three authors, it seems that Aquinas was the most advanced in this technique, as we can find even five layers of such divisions in his texts (see Thomas de Aquino Citation1952a, 1. 1, n. 23; Thomas Aquinas Citation2010, 12).

7 Q. 78c in Stephen Langton Citation2022, 201–2. This question has been transmitted (in the manuscript tradition) in three versions, marked as 78c, 78g and 78b. We have chosen the first one to illustrate the discussed case because it contains the most elaborated analysis of the main problem presented here.

8 Own translation based on Stephen Langton Citation2022, 201. The same refers to the next paragraph quoted from Langton's q. 73c. Let us quote this fragment in Latin: ‘Cui plus dimittitur ab eo plus exigitur, ergo de<biti remissio> est causa dilectionis. Item, istam responsionem approbat dominus ‘Cui plus dimittitur plus diligit’, ergo incompetenter sequitur quod dicitur ‘Dimissa sunt ei peccata multa quoniam dilexit multum’. Hic enim dilectio ponitur ut causa dimissionis, prius uero dimissio ponitur ut causa dilectionis’.

9 Stephen Langton Citation2022, 201, q. 78c: ‘[…] RESPONSIO. Dilectio ponitur hic pro signo dilectionis, sicut ibi ‘Maiorem caritatem nemo habet’ etc., et hic sensus: maior dilectio est signum maioris dilectionis. Et est hec dictio ‘quoniam’ uel ‘quia’ <ostensiua> et non causalis’.

10 Though perhaps our illustration will not be perfect, we can compare it to the situation of fire and smoke: ‘there is fire, as there is smoke’. This sentence is ambiguous, because ‘as’ can indicate a causal or evidential relationship, as Langton shows. According to the first one, we would say that the smoke is the cause of fire. But we can follow the latter to point out that the smoke is not the cause of fire, but its sign.

11 Cf. the following fragment of q. 78c in Latin:

Demonstrato infimo gradu caritatis queritur utrum iste teneatur tantum diligere, demonstrato illo qui est in mortali et sumpto hoc uerbo ‘tenetur’ in larga acceptione. Probatio: tanta caritas sufficit ad uitam eternam, et non potest aliter saluari, ergo tenetur diligere tantum. HOC ARGVMENTVM non ualet. Et prima falsa est, quia si magis diligit, non tantum diligit, ergo si magis diligit, non tenetur tantum diligere, set tamen be ne potest magis diligere, quia potest habere maiorem caritatem. Hec autem uera ‘iste tenetur magis diligere’ (Stephen Langton Citation2022, 202).

12 Bonaventure Citation2007, 379. Cf. the original text in Latin: Bonaventure Citation1893, VI:333.

13 Thomas Aquinas Citation2010, 64. Cf. the original text in Latin: Thomas Aquinas Citation1952b, l. 3, n. 1981.

14 Robert Grosseteste Citation1999, 224. Cf. the original text in Latin: Robert Grosseteste Citation1982, 220.

15 We have modified the first sentence of the English translation, as – in our opinion – it was wrongly translated: in Latin, this sentence is burdened with amphibology; the translator has chosen the option according to which the premise was that God was a trinity, and the conclusion was that God was light, whereas the analysis of the reasoning seems to clearly indicate that it is quite the opposite.

16 For a detailed description of reasoning-reconstruction methods, see Harrell Citation2016 and J.M. Bocheński's Five Ways, in García de la Sienra Citation2000, 61–92.

17 Robert Grosseteste Citation1999. Cf. the original text in Latin: Robert Grosseteste Citation1982, 218.

18 Own translation based on Albert the Great Citation1978, 109; see tr. 4, q. 21, c. 1: ‘Quod verissime est, nullo modo in potentia est; deus verissime est; ergo nullo modo mutabilis est’.

19 Robert Grosseteste Citation1999, 224. Cf. the original text in Latin: Robert Grosseteste Citation1982, 220.

20 Thomas Aquinas Citation1952b; Thomas Aquinas, De potentia dei, q. 3, a. 9, s.c. 1: ‘Est quod dicitur Isai. LVII, vers. 16: omnem flatum ego feci. Per flatum autem intelligitur anima. Ergo videtur quod anima creetur a Deo’ (Thomas Aquinas Citation1965).

21 ‘[N]aturae rationabilis individua substantia’ – Boethius, Contra Eutychen et Nestorium, 3, 5, see in: Boethius Citation2003, 85.

22 Own translation based on Stephen Langton Citation1978, 223. The same refers to the next quote.

23 Own translation based on: Albert the Great Citation1952, 111.

References

- Ajdukiewicz, K. 1922. ‘Redukcja czy indukcja?’, Ruch Filozoficzny, 7, 39a–39b.

- Ajdukiewicz, K. 1955. ‘Klasyfikacja rozumowań’, Studia Logica, 2, 278–299.

- Ajdukiewicz, K. 1957. Zarys logiki [Outline of Logic], 4th ed. Warszawa: Państwowe Zakłady Wydawnictw Szkolnych.

- Ajdukiewicz, K. 1974. Pragmatic Logic, Translated by Olgierd Wojtasiewicz, Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-010-2109-8

- Albert the Great 1952. Alberti Magni Postilla super Isaiam; Alberti Magni Fragmenta postillae super Ieremiam et postillae super Ezechielem, Edited by Ferdinand Siepmann, Henry Ostlender, Vol. 19 of Alberti Magni Opera omnia, Monasterii Westfalorum: Aschendorff.

- Albert the Great 1978. Summa theologiae sive de mirabili scientia dei libri I. Pars I. Quaestiones 1–50A, Edited by Dionys Siedler, Vol. 34.1 of Alberti Magni Opera omnia, Monasterii Westfalorum: Aschendorff.

- Bocheński, J. M. 1948. ‘On analogy’, The Thomist, 11, 424–447.

- Bocheński, J. M. 1954. Die zeitgenössischen Denkmethoden, UTB für Wissenschaft Uni-Taschenbücher 6, Tübingen: Francke.

- Bocheński, J. M. 1965. The Methods of Contemporary Thought, Dordrecht: D. Reidel.

- Boethius 2003. The Theological Tractates, Translated by H. F. Stewart, E. K. Rand, S. J. Tester, Loeb Classical Library 74. Reprint, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Bonaventure 1893. Commentarii in sacram scripturam, Vol. 6 of Doctoris seraphici S. Bonaventurae Opera omnia, edited by Collegium S. Bonaventurae, Florence: Ad claras Aquas (Quaracchi): Ex typographia Colegii S. Bonaventurae.

- Bonaventure 2007. Commentary on the Gospel of John, Saint Bonaventure, NY: Franciscan Institute Publications.

- Brożek, A., Będkowski, M., Chybińska, A., Ivanyk, S., and Traczykowski, D. 2020. Anti-Irrationalism: Philosophical Methods in the Lvov-Warsaw School, The Lvov-Warsaw School Research Center. Series of Monographs 1, Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Naukowe Semper.

- Covington, E. 2017. ‘Divisio Textus and the Interpretive Logic of Thomas Aquinas’ Lectura Ad Ephesios', Journal of the Bible and Its Reception, 4 (1), 21–41. https://doi.org/10.1515/jbr-2017-2001

- Czeżowski, T. 1946. Główne zasady nauk filozoficznych, Toruń: T. Szczęsny i S-ka.

- Czeżowski, T. 1952. ‘Klasyfikacja rozumowań’, in Odczyty filozoficzne, pp. 128–35. Toruń: Towarzystwo Naukowe.

- Even-Ezra, A. 2017. ‘Visualizing Narrative Structure in the Mediaeval University: Divisio Textus Revisited’, Traditio, 72, 341–376. https://doi.org/10.1017/tdo.2017.8

- García de la Sienra, A. 2000. The Rationality of Theism, Poznań Studies in the Philosophy of the Sciences and the Humanities 73, Amsterdam: Rodopi.

- Grice, H. P. 1989. Studies in the Way of Words, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Harrell, M. 2016. What Is the Argument? An Introduction to Philosophical Argument and Analysis, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Jadacki, J. J., Tałasiewicz, M., and Tędziagolska, J. 1997. ‘O rozumowaniach w nauce’, Przegląd Filozoficzny – Nowa Seria, 6 (1), 7–29.

- Jamieson, R. B., and Wittman, T. 2022. Biblical Reasoning: Christological and Trinitarian Rules for Exegesis, Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, a division of Baker Publishing Group.

- Kotarbiński, T. 1966. Gnosiology: The Scientific Approach to the Theory of Knowledge, Translated by Olgierd Wojtasiewicz, Oxford: Pergamon Press; Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich.

- Kwiatkowski, T. 1993. ‘Classification of reasonings in contemporary polish philosophy’, in Francesco Coniglione, Roberto Poli, and Jan Woleński (eds.), Polish Scientific Philosophy: The Lvov-Warsaw School, Poznań Studies in the Philosophy of the Sciences and the Humanities 28, Amsterdam: Rodopi, pp. 117–68.

- Łukasiewicz, J. 1934. O nauce [On Science], Lwów: Polskie Towarzystwo Filozoficzne.

- Łukasiewicz, J. 1961. ‘O twórczości w nauce [On Creativity in Science]’, in Z zagadnień logiki i filozofii, Pisma wybrane, Warszawa: PWN, pp. 66–75.

- McKeon, M. W. 2013. ‘On the rationale for distinguishing arguments from explanations’, Argumentation, 27 (3), 283–303. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10503-012-9288-1

- Nannini, A., and Trepczyński, M. 2022. ‘“In Principio”: the metaphysical exegesis of John 1:1 by Albert the Great, Bonaventure and Thomas Aquinas’, Biblica et Patristica Thoruniensia, 15 (2), 41–54. https://doi.org/10.12775/BPTh.2022.009

- Peirce, C. S. 1978. Pragmatism and Pragmaticism and Scientific Metaphysics, Edited by Charles Hartshorne and Paul Weiss, Vol. 5 and 6 of Collected Papers of Charles Sanders Peirce, edited by Charles Hartshorne, Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

- Polloni, N. 2021. ‘Early Robert Grosseteste on Matter’, Notes and Records: The Royal Society Journal of the History of Science, 75 (3), 397–413. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsnr.2020.0017

- Quinto, R., and Bieniak, M. 2014. ‘Introduction’, in Stephen Langton, Quaestiones Theologiae. Liber I, edited by Riccardo Quinto and Magdalena Bieniak, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 1–231.

- Robert Grosseteste 1982. Hexaëmeron, Edited by Richard C. Dales and Servus Gieben. Auctores Britannici Medii Aevi 6, London: Oxford University Press.

- Robert Grosseteste 1999. On the Six Days of Creation, Edited by Christopher F. J. Martin. Auctores Britannici Medii Aevi 6(2), Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Rossi, M. M. 1994. ‘La “divisio textus” nei commenti scritturistici di S. Tommaso d'Aquino: un procedimento solo esegetico?’, Angelicum, 71 (4), 537–48.

- Roszak, P. 2021. ‘Biblical exegesis and theology in Thomas Aquinas: understanding the background of Biblical Thomism’, Studium. Filosofía y Teología, 48, 13–25.

- Roszak, P. 2022. ‘Text, method, or goal? on what really matters in Biblical Thomism’, Religions, 14 (1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14010003

- Salamucha, J. 1930. Pojęcie dedukcji u Arystotelesa i Św. Tomasza z Akwinu, Warszawa: Polskie Towarzystwo Teologiczne.

- Searle, J. R. 2011. Speech Acts: An Essay in the Philosophy of Language, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Stephen Langton 1978. Commentary on the Book of Chronicles, Edited by Avrom Saltman, Ramat-Gan: Bar-Ilan University Press.

- Stephen Langton 2022. Quaestiones theologiae. Liber III, Volume 2, Edited by Magdalena Bieniak, Marcin Trepczyński, and Wojciech Wciórka, Auctores Britannici Medii Aevi, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Thomas Aquinas 1952a. Sancti Thomae de Aquino Super Evangelium S. Ioannis lectura, Edited by Raffaele Cai, Taurini.

- Thomas Aquinas 1952b. On the Power of God, Translated by English Dominican Fathers, Westminster, MD: Newman Press.

- Thomas Aquinas 1965. Quaestiones disputatae de potentia, Edited by P. M. Pession, Vol. 2 of Quaestiones Disputatae, Taurini: Marietti.

- Thomas Aquinas 2010. Commentary on the Gospel of John, Books 1–5, Edited by Daniel A. Keating and Matthew Levering, Translated by Fabian R. Larcher, Fabian Larcher, and James A. Weisheipl, Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press.

- Twardowski, K. 1901. Zasadnicze pojęcia dydaktyki i logiki. Do użytku w seminaryach nauczycielskich i w nauce prywatnej [Fundamental Concepts of Didactics and Logic], Lwów: Towarzystwo Pedagogiczne.

- Twardowski, K. 2014. ‘Autobiografia [5] [Autobiography [5]]’, in Myśl, mowa, czyn, Edited by Jacek Jadacki and Anna Brożek, Vol. 2, Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Naukowe Semper, pp. 35–49.

- Urbański, M. 2009. Rozumowania abdukcyjne. Modele i procedury, Poznań: Wydawnictwo Naukowe UAM.

- Urbański, M., and Pietruszewski, P. 2019. ‘“How did you know that, Holmes?”. Inferential Erotetic Logic in Formal Modelling of Problem-Solving in Criminal Investigations by Sherlock Holmes’, Ruch Filozoficzny, 75 (2), 75. https://doi.org/10.12775/RF.2019.021

- van der Schaar, M. 2016. Kazimierz Twardowski: A Grammar for Philosophy, Poznań Studies in the Philosophy of the Sciences and the Humanities 103, Leiden: Brill Rodopi.