Abstract

For financial and strategic reasons, public and semi-public construction clients increasingly depend on private parties to carry out public service delivery. They subcontract operational responsibilities to private parties while remaining socio-politically responsible for ensuring public values. Public administration literature mainly addresses the importance of procedural and performance values in safeguarding public values. However, safeguarding the quality of the built environment also requires a focus on product values. In this study, we aim to increase the understanding of the meaning and significance of public values in the daily practice of public construction clients and identify the challenges they face in commissioning these seemingly opposing values. A set of semi-structured interviews with the public administrators of a variety of public and semi-public construction client organizations in the Netherlands shows that both internal and external factors influence the collaborative practices between clients and contractors. This causes a value shift from an emphasis on procedural values to managing performance and product values, indicating that clients need to take on a wider view on public values. Six main public value dilemmas were found that complicate the task of developing an open, transparent and sustainable long-term client–contractor relationship. The current contractual system, however, lacks the flexibility to facilitate this product-based value view in construction.

Introduction

In order to achieve and ensure their public objectives in the built environment, public client organizations deliver public services: they exchange direct or indirect products and services among individuals, companies, social institutions and the government (Benington Citation2009, Benington Citation2011). In construction, the government was traditionally in control as the client and a private contractor was commissioned to execute the work. In recent years, however, we have seen a growing percentage of integrated contracts (Winch Citation2010, Noordegraaf Citation2015). In these types of collaborations, the operational responsibility for creating public values is transferred to the private party, the public party is left with governing and management tasks while remaining socio-politically responsible (Eversdijk Citation2013, Van Der Steen et al. Citation2013).

The presumption that complexity and specialization are required in solving today’s societal challenges, reinforced by the lack of resources and competencies of public organizations, makes it sensible for public agencies to outsource specific functions to other organizations (Boyne Citation2003, Cornforth Citation2003, Cohen Citation2008). An increasing number of quasi-autonomous government agencies develop and furthermore market mechanisms introduce elements of competition in public service delivery, making public organizations increasingly dependent on private parties to accomplish public purposes (Cornforth Citation2003). As a consequence, public construction clients are involved both in the long-term focus on innovation and the strategic development goals of the public organization, as well as the short-term focus on the efficiency goals of the temporary project-related network of public and private parties (Lundin et al. Citation2015). Construction clients are often challenged by the constantly recurring value conflicts of the exploration–exploitation paradox (Eriksson Citation2013). As a response to the fragmentation and special purpose entities that outsourcing causes, there is an increased focus on building a strong and unified sense of values, trust and value-based management between public and the private parties, affecting the task of public administrators in the public value process (Bryson, Crosby and Bloomberg Citation2014, Christensen and Lægreid Citation2007, De Graaf and Paanakker Citation2014)

Hence, due to the complexity of the relationship, public–private collaborations do not always contribute to public goals (Liu et al. Citation2016, Hueskes et al. Citation2017). For example, in recent decades, several large and complex infrastructure works and utility buildings in the Netherlands have been delivered as DBFM contracts in close collaboration with private parties (Lenferink et al. Citation2013). As a response to time pressure, the involvement of external stakeholders and project culture this has not always led to the desired level of performances (Verweij et al. Citation2017). Similar experiences can be found in the UK. In line with the UK government’s drive to pursue a knowledge-based economy, the “Building Schools for the Future” (BSF) was launched in 2003 as a long-term programme of DBFM investments and change in the English school system (Aritua et al. Citation2008, Liu and Wilkinson Citation2014). Difficulties in BSF arose from not sorting out strategic issues and instituting appropriate organizational frameworks before engaging the private sector, resulting in a lack of clarity about the long-term needs and end-user aspirations of such long-term public–private collaborations (Aritua et al. Citation2008, Liu and Wilkinson Citation2014).

To better understand, the value interests and challenges that construction clients face in the “wicked problems” settings of public service delivery in the project-based construction industry (Head and Alford Citation2015), more information is needed about the meaning and significance of different public values in the daily practice of public construction clients. Realizing the opted value, considerations need to be made in assessing the most suitable way to achieve the best value in the context of this governance reform. It is, therefore, important to perform an analysis in order to indicate what “value” should be achieved, to locate contributors to this value and understand how these value contributors could be evaluated in terms of objective and subjective indicators in relation to the built environment (Palaneeswaran et al. Citation2003).

This study contributes to the management of values in construction in two ways. First, it identifies the full spectrum of public-private values from a public client perspective that come into play when delivering public services in the construction industry. Most studies on public values recognize the importance of sets of procedural values such as lawfulness and accountability, and the performance values of efficiency and effectiveness (e.g. J⊘rgensen and Bozeman Citation2007, Van Der Wal et al. Citation2008). Hence, none of these concepts provides concrete insights into the content of these values in order to specify, clarify and describe the service or product (Mills et al. Citation2009, Bozeman Citation2012), such as providing shelter, mobility and leisure. Other studies pointed out the importance of a better operationalisation of public values in different industries (e.g. specialized codes for roles and professions) (De Graaf et al. Citation2013). Hence, we complement the existing public value concepts with the concrete product-related public values, such as the quality of public space and well-functioning infrastructure, and explicate the process and performance values that are related with the construction industry.

Second, we provide insight into the value trade-offs that need to be made in various stages of the construction lifecycle (Hughes et al. Citation2006, Brown et al. Citation2006). Public management scholars seem to pay less attention to criteria for judging public values. Yet, this is especially important when multiple logics are combined, such as in public-private collaborations. As a result value conflicts are likely to appear (De Graaf and Van Der Wal Citation2008), which complicates the task of public construction clients to actually manage public values in their daily practice. The characteristics of public values complicate decision-making as rational assessment often seems impossible (De Graaf and Paanakker Citation2014). Hence, identification of the trade-offs professionals in client organizations makes contributes to facing the challenges of collaborative practices in construction.

In this study, we build upon the public value theory and extend the construction sector-specific value debate. We specifically look into the dynamics of the value interests of public construction clients and address the following questions:

Which public values play a role in public service delivery practices between public clients and contractors in construction?

What contextual factors influence construction client’s value interests in these practices?

Which public value challenges do construction clients face in collaborative practices of public service delivery in construction?

The article proceeds as follows. We first elaborate on the public value concept, the different types of public values that could be of importance for public construction clients, while also taking into account the contextual influences on value interests, such as socio-political responsibilities and regulatory developments in the Dutch construction sector. We also discuss the complexity of managing public values by elaborating on the challenges public construction clients face in balancing seemingly opposing values in today’s collaborative public service delivery. This theoretical elaboration is summarized in a framework containing 25 values divided into different types. We then describe our research approach which involved a series of semi-structured interviews with 47 public administrators from commissioning agencies in the Dutch construction industry. The findings are presented in three separate sections on public value interests, factors of influence and challenges faced by public clients. Based on these findings, we conclude that professionals in public construction client organizations are increasingly aware of the shift from procedural and performance values to product-related values that are required to improve public service delivery. Yet, the current contractual system seems to lack the flexibility to facilitate this value shift and safeguard “new” product-related values. In their commissioning role, public administrators face value dilemmas that are usually solved in an operational rather than a strategic manner. Instead, they should take on a wider view. Finally, we discuss the boundaries of the current value system in relation to change of the practice of the commissioning role and provide potential interesting avenues for further research that relate to the alignment of roles, organization and the system in construction industry.

Theoretical background

The public value concept

Public values are a reflection of what society believes are important values in the production of certain products or services and whose provision is the responsibility of the government (De Bruijn and Dicke Citation2006). This provides direction for governmental decision making. For a value to be called public, there needs to be a collectivity – a collective benefit. So, whereas private values reflect individual interests public values are about meeting shared expectations (Van Der Wal et al. Citation2008). There is also value pluralism, meaning that not all values can be achieved at the same time, and public values are often incommensurable and incompatible leading to their conflicting nature (De Graaf and Paanakker Citation2014). Although the definition of a public value remains rather abstract, it is clear that the “public” aspect relates to ultimately remaining responsibility. To list the specific values that could relate to public commissioning in construction, we, therefore, particularly looked at the work of J⊘rgensen and Bozeman (Citation2007), Van Der Wal (Citation2008) and De Graaf et al. (Citation2013) from the field of public administration. Based on a systematic literature survey of a large amount of studies in the United States, the United Kingdom and Scandinavia, J⊘rgensen and Bozeman (Citation2007) identified eight central public values, namely sustainability, human dignity, engagement of citizens, secrecy, openness, integrity, compromises and robustness. And, although the time range from 1990 to 2003 in the research of J⊘rgensen and Bozeman (Citation2007) excluded certain periods of public governance reform and some identified values are removed from their context, the study gives a broad overview of values in different categories that could be considered in more specific industry contexts like construction. The fact that values have a strong resemblance internationally is also confirmed in the study of De Graaf, Huberts and Smulders (Citation2014), in which they compare international codes of governance. Van Der Wal (Citation2008) distinguished 13 values that are most relevant in public organizations, namely honesty, humanity, social justice, impartiality, transparency, integrity, obedience, reliability, responsibility, expertise, accountability, efficiency and courage. His work mentions the possible use of the public–private continuum as a feasible value survey research tool. Especially in relation to the shifting relationships between the public and the private, Van Der Wal (Citation2008) provided an interesting view on the degree of association of value to the public and private sector poles and the overlap thereof. De Graaf et al. (Citation2013), especially, studied the relevance and role of values in the Dutch Code of Governance using two case studies of a Dutch municipality and a Dutch hospital, interviewing various actors about their daily practice. They found valuable insights into the specific values related to different aspects of good governance that show that (a) democratic governance particularly values openness, participation, accountability and legitimacy, (b) proper governance focuses on lawfulness and decent contact with residents, (c) incorruptible governance values integrity and (d) performing governance values effectiveness, efficiency and professionality which give meaning at different management and executive levels (De Graaf et al. Citation2013).

Another characteristic of public values is their typology. Distinctions are made among different types of public values. De Graaf and Paanakker (Citation2014), for example, followed the most general consensus on the interpretation of good governance and differentiate between the performance values of effectiveness and efficiency (e.g. good infrastructure, services, no waste of taxpayers’ money) and procedural values, relating to the quality of the process (e.g. integrity, transparency, equality). Their case study research focusses on conflicts between performance values and procedural values in different phases of the political processes of formation, negotiation and implementation. Whereas their governance level of analysis corresponds with our level of analysis, De Graaf and Paanakker (Citation2014) remained quite conceptual in their study on public values in the public domain rather than providing concrete details about how to manage these values in delivering services in the built environment. De Bruijn and Dicke (Citation2006), however, provided explicit examples when presenting their inventory of the literature on public values from three disciplines (i.e. law, economics and public administration) in the context of the utility sector, in which, like the construction sector, increased privatisation and contracting out is seen. A division is made between procedural values – the way the public sector should act and which standards of government action should be met, such as integrity, transparency and equality – and substantive public values, that is, the services the state is responsible for, either directly by offering products or indirectly by providing services and finance (De Bruijn and Dicke Citation2006). According to De Bruijn and Dicke (Citation2006), the discourse around procedural values can be recognized in codes of conducts of various international governments; on the other hand, the substantive product-related values can be specified for each utility sector. Reflecting on their results, De Graaf et al. (Citation2013) went even further, suggesting the need for codes specified for roles and professions next to more general codes.

Based on these insights, we use the distinction among procedural values, performance values and substantive product-related values to develop our (theoretical) understanding of the content of public construction clients interest and their challenges in value-based decision-making. In particular, in relation to these substantive product-related values, it is important to note the difference between value and values. Inspired by the most advanced individually grounded theories on human value, the Schwartz Values Survey and Universal Values Structure, Mills et al. (Citation2009, p. 7), Mills (Citation2013, p. 86) define values as “abstract, humanly held notions and beliefs that provide a broad and relatively universal framing structure to understand particular choices in a wider context of concerns”. And, value is “an attitude or judgement made by a person of some object at issue (whether this is a product, service, process or other person) against some resource” (Mills Citation2013, p. 118), which is in line with Volker’s (Citation2010) definition of value judgement in the context of a building object. In the field of public value management, Moore and Bennington seem to be the two main contributors to value thinking. Moore (Citation1995) considered public value as the equivalent of shareholder value in public administration and spoke of the singular public value. According to Moore (Citation1995), public values are designed to provide managers with a notion of how entrepreneurship can contribute to the general welfare. Benington (Citation2011) referred to the plural of public value and interpreted public values as the combination of safeguarding and enriching the public sphere with the delivery of public values. His work presented a rather normative description of the “rights, benefits, and prerogatives” to which citizens should or should not be entitled “within the notion of the ‘public sphere’”, as “a democratic space which includes, but is not co-terminus with, the state within which citizens address their collective concerns, and where individual liberties have to be protected” (Benington Citation2009, p. 233). Moore (Citation1995) also described a process, which he calls the public value chain, in which inputs are transformed into valued social outcomes, or in other words public values. Farrell (Citation2016) added an important governance dimension to this chain by specifically looking at the position of the public value proposition. He placed it between the demand and the supply chain and connected the value that should be produced in order to meet the demand to the activities of the production. Farrell (Citation2016) thereby underlined the importance of understanding the value interest of a commissioning agency in the process of public value creation. In creating and ensuring public values, it must be clear which values should be secured in relation to the socio-political responsibility of the public agent in the supply chain.

Factors of influence on value interests

Both Mills et al. (Citation2009) and Volker (Citation2010) emphasized the importance of a dialogue on organizational values and human values in aligning the value priorities of individuals and organizations. Based on insights from previous governance reforms, there are many reasons for the value paradigms of public organizations to change (Christensen and Lægreid Citation2007, Coule and Patmore Citation2013, Bryson et al. Citation2014, Casey Citation2014). In governance reform, different governance paradigms follow each other in time, positioning more or less towards public and private values. For example, as a response to the fragmentation, the structural devolution, single-purpose organizations and performance management caused by new public management, there was a new emphasis on public value, focussing on a unified sense of values, trust, value-based management, and collaboration. Although interpretations may be different from country to country, in different time periods and from sector to sector (Van Der Wal et al. Citation2008), some values (e.g. social justice and impartiality) seem to be more prominent for public organizations, Whereas other values (e.g. profitability and self-fulfilment) are more prominent for private organizations, and yet others (e.g. honesty, accountability, expertise and reliability) appear to apply to both public and private parties (Van Der Wal Citation2008).

Hendriks and Drosterij (Citation2012) argued to specifically look into the importance of values in the different stages of the policy process, in which public organizations express the values they stand for. Although various scholars have pointed to this relationship between publicness and value paradigms, Andersen et al. (Citation2012) also stated that different modes of governance reflect different value orientations of management paradigms. In line with this, according to Talbot (Citation2008, p. 10), this competing values framework “asserts that human organizations are shaped by just two fundamental contradictions – the desire for flexibility and autonomy versus the need for control and stability; and the focus on internal concerns and needs versus responsiveness to the external environment”.

The need to recognize the value orientation of organizations is also noticed in organizational studies. Several studies show that market and community logics are combined and values are created by networks of public and private parties (Coule and Patmore Citation2013, Van Der Steen et al. Citation2013, Casey Citation2014). Using market logics, the basis for strategy is profit maximization. Using community logics, relations of affect, loyalty, common values and personal concern are pursued (Smets et al. Citation2014). Each logic influences which values are considered most important in governance. Market logics are dominated by performance values, whereas community logics are dominated by procedural values (De Graaf and Paanakker Citation2014, Smets et al. Citation2014). This indicates that the perspective on the public–private relations influences the approach to public values and, as a result, the way of safeguarding public values.

Whereas the works of Smets et al. (Citation2014), Van Der Wal et al. (Citation2008), Andersen et al. (Citation2012) and Talbot (Citation2008) focus on the organizational level, Meynhardt (Citation2009), especially, looked at public value creation from the perspective of the individual and therefore encouraged research into social relations. Meynhardt’s work draws a public value landscape departing from four basic value dimensions derived from the psychologically oriented needs theory. What is especially interesting is that this landscape is filled out for a public sector in a democratic society, following the inventory of public values compiled by J⊘rgensen and Bozeman (Citation2007), who categorized values related to different relationships between public administrators, such as politicians and their environment, showing noteworthy similarities with the client–contractor relationship in the context of studying the commissioning role in construction.

Starting from the internal perspective on the public client organizations, the studies mentioned above show the relevance of studying the impact of governance reform, the value perspective, the positioning of the client in the public–private continuum and the social relationships on organizations in construction. Looking more closely into the context in which public construction client organizations operate, an important distinction can be made between organizations that are purely public or are governed by public law and are required to apply public procurement law, and semi-public and private organizations, which only have to obey common law (Boyd and Chinyio Citation2008, Winch Citation2010). Taking on this external perspective, we can understand that the position of an organization on the public–private continuum is partly determined by the extent to which organizations are constrained by political control, how they are funded and financed, and the extent to which they perform public and private tasks (Besharov and Smith Citation2014). When an organization is more constrained or enabled by political authority, it is more public (Bozeman Citation2012) and an increase in constraint by economic authority seems to increase the “privateness” of the organization (Moulton Citation2009), limiting public clients’ positioning in the value landscape and thereby the expression of value interest. Especially in the mid-section of the public–private continuum, the organizations governed by public law and public–private organizations are internally hybrid, pursuing both values from the political/public mandate and private organizational values (Heres and Lasthuizen Citation2012). This differs per culture, country and region (Boyd and Chinyio Citation2008).

From the previous parts of this article, we can conclude that most of the work on public value focuses on procedural and performance values. We also learned that substantive product-related value may be specified in its context, especially per role and/or profession. In the context of the construction industry, specific assessment methods and policy documents can provide insights into the governance challenges of product values. The more project-oriented steering mechanisms of money, stakeholders, time, information and quality in the context of project management (Ogunlana and Toor Citation2010) play a significant role in the construction industry. The Design Quality Indicator (DQI) provides a toolkit to measure, evaluate and improve the design quality of buildings. This tool, which was developed by the Construction Industry Council of the UK, builds on Vitruvius’s product values of utilitas, firmitas and venustas (commodity, firmness and delight) to provide concrete discussions on functionality (use, accessibility and space), built quality (performance, technical systems and construction) and impact (form and material, internal design, integration and character and innovation) in different phases of the construction process (Gann et al. Citation2003, Volker Citation2010). In relation to the publicness of the organizations, we noticed that the periodically developed policy documents concerning the built environment influence the product values of clients. The Dutch government, for example, is currently implementing the “Omgevingswet” – an integrated law to ensure the quality of the built environment. This new law is dominated by specific values, such as collaboration, knowledge and expertise, commonality, integrated concepts, health and motivation in solidarity. It is these kinds of developments that also shape the challenges that clients face in delivering public services in the construction industry. So by looking more closely into the external contextual factors, we found that the influence of regulations (especially public procurement law) as well as time-dependent policies which relate to societal challenges, strongly affect the value interests of public construction clients in the construction industry.

Specific client challenges in creating public value in construction

The collaborative character of today’s public service delivery complicates the task of choosing which value to pursue. This challenges public construction clients to balance the different kinds of competing values while honouring the structures of authority and regime values within which they operate (Bao et al. Citation2013). After all, it is the value proposition of the client organization that should steer the decisions and trade-offs that occur between the creation of private and public values (Farrell Citation2016). Because public values can be incompatible, the pursuit of certain values must inevitably comprise or limit the ability to pursue certain other values (De Graaf and Paanakker Citation2014). Furthermore, because public values can be incommensurable, there is no single currency or scale with which to measure conflicting values. Where a conflict occurs, no rational assessment can be made. This study should, therefore, contribute to identifying the challenges that client organizations face in working with contractors to deliver public services.

In this context, it is important to realize that public values are achieved in different phases of the construction lifecycle. In the initial phase, there is the most flexibility and the decisions made largely determine the ability to ensure and safeguard public values in the following phases (Hughes et al. Citation2006). The make-or-buy stage revolves around whether conditions are suitable for contracting and whether public values are safe in private hands (Brown et al. Citation2006). After deciding to contract, a client needs to structure and execute a competitive bidding process in order to select a contractor to produce “what is asked”. In designing a contract, a client needs to make many decisions that are laden with public value, including specifying a contractor’s obligations and tasks, defining the contract’s renewal provisions, and specifying its incentive and performance-measurement systems (Brown et al. Citation2006, Hughes et al. Citation2006). After a contractor has been selected and the contract awarded, the client must shift its focus to managing the contract. This stage is about deploying monitoring tools to oversee the implementation of contracts. It is expected that different value conflicts will arise during different phases of public service delivery and that trade-offs between performance values, procedural values, and product-related values in the construction context, will need to be made (De Graaf et al. Citation2014, De Graaf and Paanakker Citation2014). Clients will be called to account for the process as well as the outcome, and for individual incidents as well as aggregate patterns observed at each step along the way to public value creation (Moore Citation2000).

From this, we understand that safeguarding public values in public service delivery has both governance components and management components in public construction client organizations. According to the OECD, a construction client “is a natural or legal person for whom a structure is constructed, or alternatively the person or organization that took the initiative of the construction” (Eurostat Citation2013). As in this research, the context is formed by the collaborative public service delivery, the relationship between client and contractor is central. We look at commissioning as the way a public organization, in relation to its responsibilities in the built environment, shapes and implements its interaction with the supply market, both externally and internally (Hermans et al. 2014). Different relations can be recognized, namely client–stakeholders (all kinds of societal parties), client–user and client–contractor/supplier. The last-mentioned is the focus of this study.

In integrated contracts, quality assurance is focused on organizing the process, ensuring that there is compliance with both the product and the process requirements (Brown et al. Citation2006). In this context, the client is limited to establishing a functional set of requirements, emphasis on performance and outcome, on what is expected (Boyd and Chinyio Citation2008, Bryson et al. Citation2014), for which private parties then submit design solutions (performance contracts) (Hughes et al. Citation2006). A completely different dynamic arises if the client outsources not only the design and execution but also the activities or services that usually take place during the usage phase. Zheng et al. (Citation2008) found that specifically in long-term public–private supply arrangements, complicated value trade-offs take place at different levels of the client organization, related to private parties in different ways of relational and contractual governance. This means that public construction clients are confronted with multilevel challenges in their attempt to improve public service delivery with which public values are created, using integrated tasks and public–private collaborations.

Public value framework for construction clients

Based on the theoretical insights into the different kinds and types of values, the contextual factors of influence in the increasingly collaborative public service delivery and the specific challenges for client organizations in identifying the values to pursue, we take on the view that, in addition to the procedural values and the performance values, the product-related values are deemed especially important for public clients in the construction industry. Hence, we created a public value framework for construction clients that presents a comprehensive and inclusive overview of 25 public values that could be considered of importance in public commissioning tasks (see ). This framework provides the basis for the study.

Table 1. Public value framework for construction clients.

Research approach

Research methodology and data collection

The main purpose of this study is to gain insight into the meaning and significance of public values in the daily practice of public construction clients and the challenges that they face in their commissioning role. This implies recognition of the role of the sociocultural and political environments in the management of construction projects, and thereby the need to understand projects as socially constructed realities and the subjective relevance (Dainty Citation2008). Hence, an inductive qualitative approach was chosen to gain a profound understanding of the existence of construction sector-specific public values, to establish their meanings and identify the way the values are embedded in public client organizations (Miles and Huberman Citation1994).

The study presented in this article is based on 44 semi-structured interviews with 47 interviewees (in some interviews two respondents participated), representing 17 Dutch public and semi-public construction client organizations. The interviewees were chosen by expert sampling, a form of purposive sampling that selects respondents known to have a certain expertise in the field, followed by snowball sampling (Hennink and Hutter Citation2011). Because the position of an organization on the public–private continuum influences the need to perform public value tasks and the ability or inability to adopt and balance public value with other types of values (Van Der Wal Citation2008, Besharov and Smith Citation2014), a wide range of public client organizations in the study were included. This afforded the opportunity to study differences and similarities, and generalizability where possible (Chi Citation2016). We approached members of the Dutch Construction Clients’ Forum which represents a group of large and medium-sized public and semi-public clients in the Dutch construction industry, including the Central Government Real Estate Agency, the national highway agency Rijkswaterstaat, several water boards, housing associations and municipalities. For each organization, the aim was to involve three or four public administrators, divided over four position categories: general manager, chief procurement officer, director of new – real estate and/or infrastructure – developments, and/or director of asset management or maintenance, reflecting the multilevel challenge. During the initial interviews, additional respondents were obtained through their networks, until we reached the data saturation point. presents an overview of the respondents in relation to the publicness of the organization and the position of the respondents.

Table 2. Overview of respondents.

We used an interview guide with open-ended questions in order to discuss the sensitive topic of public values in relation to experiences in various parts of the commissioning role, and providing topics and some related standard questions were used (Hennink and Hutter Citation2011). Each interview started with a brief discussion about the background of the interviewer and interviewee in order to ensure a mutual understanding of the perspective to be discussed. In order to discuss different aspects of the commissioning role, the interviews were divided into three parts. The first part referred to the commissioning role in shaping the collaborative relationship with the supply market. The second part related to how management steered employees in ensuring values in public service delivery, and the final part referred to the organization itself, emphasizing the way of steering on organizational values related to public commissioning. We, therefore, focused on the translation of these values into the identification of organizational goals, and whether the position in society, influenced by different groups of stakeholders would be relevant in this context. Inspired by Q-methodology – a method that is increasingly applied to gain insight into the range of viewpoints providing a foundation for the “systematic” study of subjectivity, a person’s viewpoint, opinion, beliefs, attitude and such like (Stephenson Citation1953) – we used value cards to support the interviewees in answering the interview questions. Hence, the 25 public values from the public value framework for construction clients from were printed on paperboard cards. To ensure that the distinction between the different values was absolutely clear to the interviewees, word clouds with interchangeable terms were included.

All interviews were conducted by the first author and each lasted 45–60 min. Interviewees were asked to explicitly explain their choices discussing the relevance and meaning in the part of the commissioning role being discussed while working on this sorting task. The interviewees were respectively asked to choose three-value cards that appealed most to them when asked: (a) which values they consider important in their commissioning role, (b) which values are most likely to be traded off, (c) which values they prefer to be safeguarded and (d) which values do not get safeguarded by their organization. There also was a possibility to create an additional card by filling out a blank. These choices prepared the interviewees to subsequently rank the value cards according to the extent they are considered to be of interest in their commissioning role from −3 (of least interest) to +3 (of most interest). To conclude, interviewees were asked to indicate whether they expect the ranking to be the same in about 10 years’ time and to elaborate on this, also in relation to the public values that are assigned to the organization as a whole and the mutual influence with the public values discussed. To ensure the reliability of the data, all interviews were audiotaped and fully transcribed. The value cards chosen by the interviewees were recorded on an Excel sheet and photos were taken of the filled-out Q-sorts.

Analysis of the data

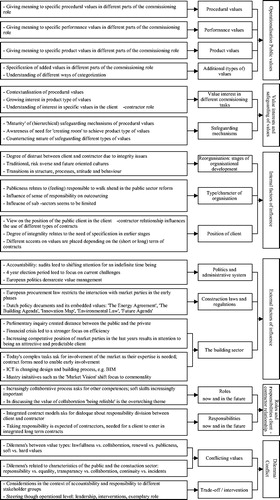

We adopted a systematic inductive approach to concept development as described by Gioia et al. (Citation2013) allowing for studying social construction processes focussing on sensemaking of our respondents. The data structure was built using a set of five transcripts in Atlas.ti (see ) and an additional set of another five transcripts for a second round to become familiar with the data (Altheide Citation2000, Gioia et al. Citation2013). In the initial data coding, we applied open coding as described by Corbin and Strauss (Citation2008), sticking to the respondents terms focussing on the means by which respondents construct and understand their commissioning experiences (Gioia et al. Citation2013). After reducing this first-order analysis to a manageable number of first-order concepts, axial coding was applied in order to seek for similarities and differences in a second-order analysis and placing the categories in the theoretical realm (Van Maanen Citation1979, Gioia et al. Citation2013). We then looked for overarching theoretical themes to further reduce the categories to second-order “aggregate dimensions”. demonstrates how the interview transcripts, the first-order data, through second-order concepts progressed into overarching theoretically grounded themes that related to the research questions.

Looking into the understanding of sector-specific public values in commissioning (RQ1) led to the operationalization of public values: procedural values, performance- and product values and additional values. In addition, an overarching (theoretical) theme was created around value interests and safeguarding of public values, containing second-order concepts corresponding with the interest in different aspects of public commissioning and accompanying safeguarding mechanisms. The often reflective explanation of the interviewees resulted in the identification of the shift of values as experienced by the respondents and gave a particularly good insight in the meaning and importance of the different public values in the desired client–contractor relationship.

In relation to the dynamic value interest of public construction clients (RQ2), two overarching (theoretical) themes were found; (1) internal factors of influence, subdivided into the type and character of the organization, the maturity stage of an organization and the perception of the clients position in the client–contractors relationship, and (2) external factors of influence, clustered in groups of data related to politics and the administrative system, construction laws and regulations, and developments in the building sector at system and executive level. Furthermore, the overarching (theoretical) theme of roles and responsibilities in the client–contractor relationship includes data about the current situation and the desired situation, with explicit attention to changing perceptions about specific collaborative models and contract types. Regarding the public value management challenges (RQ3), an overarching (theoretical) theme specifically focusses on detecting dilemmas. This divided the data of the second-order concept of specific value conflicts between different types of organizations and origination from the character of the organization and sector, and a concept about the (way of) balancing and specific interventions focused on the steering part including the current and (desired) future practice and accountability against distinguishing the different aspects of the commissioning role. Especially, the reflection on the ranking (Q-sorts) gave insight in the value dilemmas that clients face and increased the understanding of the restrictions that certain values, mainly procedural, bring along in pursuing the desired client–contractor relationship.

In order to analyze differences between the types of client organizations in degrees of publicness and different decision-making levels within these client organizations, the transcripts were grouped into public and semi-public and then analyzed in among the groups. The Excel sheet with the outcomes of the value cards was used to validate the outcome of the analysis of the data reports, because some values might be discussed more extensively, suggesting a greater importance and imposing certain ideas or thoughts. Furthermore, data reports were read by the second author, as well as the data structure during its development, and interpretations were compared and discussed with all authors for further validation.

Findings

Public value interests of public construction clients

In relation to the question, which public values play a role in collaborative practices between public clients and contractors in construction (RQ1), we found a general agreement on the importance of a set of procedural values strongly related to the lawfulness and responsibilities of public client bodies represented in the values of integrity, transparency and reliability (see ). Semi-public clients seem to lay the most emphasis on lawfulness compared to other types of organizations. In general, there appears to be a strong awareness of the public task in officials of all types of public organizations.

Table 3. Top 5 public value interests according to the degree of publicness.

Intrinsically, people working at governmental bodies feel that they are there to serve the general interest, not the interest of the organisation. (19: CPO, CG)

I just have to retain integrity. That is part of the public value I represent. A government official should always keep this in mind. (11: CPO, CG)

Whereas the figures in suggest that there is no further consensus on values of significance in the client–contractor relationship, many of the values were actually clustered by the respondents. For example, the values honesty, accountability, integrity, lawfulness and transparency are seen as inextricably connected.

Reliability, but I think this also includes honesty, lawfulness, integrity and safety – I take a wider view. (13: CPO, GbL)

Results also show that in the current collaborative practices of public service delivery, the procedural values of integrity, lawfulness, reliability and equality are increasingly considered as contextual, whereas the purpose of steering becomes directed at other values, such as innovation, sustainability and quality. Remarkably, the value of quality is ranked relatively high by public organizations as opposed to organizations governed by law and semi-public organizations.

If you're talking about how we do things, I think that it could be a bit more innovative […] Transparency, and I should say integrity, even though I think this is less important, remains an important theme. (1: DD, GbL)

Nonetheless, these product-related values are under pressure. If the public character is leading in a certain situation, it becomes clear that “the system” is inflexible, whereas “space” is needed to pursue these product-related values. The desire to shift the focus towards these product values originates from the aim to improve public service delivery. According to the respondents, in addition to performing the legal task as a contracting authority, added value may be achieved by pursuing values such as innovation, effectiveness and sustainability.

Those are not the values that drive me the most, meaning that they do not add a lot of value at this moment, but we should monitor them – lawfulness, transparency and integrity, however that is of course not where our greatest added value is. The supply market is much broader. Then you also come across other things, such as innovation, effectiveness and sustainability. (2: CPO, SP)

The basic project values of time, money and quality still have a significant influence on the way public clients act. As they work with taxpayers’ money and need to account to society, these values are an important tool in quality assurance. Adding values such as innovation and sustainability can nowadays only be achieved through these basics.

Money is very much a driving force. That affects the functionality, which influences innovation, which affects quality. (5: AM, GbL).

To pursue other values requires room to manoeuvre. According to the majority of the respondents, the room can be created to achieve these additional product values only if other procedural values correlating with the public character of the clients and other quality assurance measures are well arranged.

Being a reliable public client

When discussing the commissioning role and the values that play a role within the client–contractor relationship, the value of collaboration was put forward as an increasingly important value. In discussing the value of collaboration, “being reliable” was the overarching theme. Two lines of reasoning can be recognized in this context (these lines are also summarized in ).

Table 4. Values related to being a reliable public client, with examples of explanatory quotations.

First, being a reliable partner in the client–contractor relationship. Public clients are increasingly concerned with their approachability: they seek connections rather than contradictions in order to build an equal, sustainable relationship on the basis of common values. Respondents said that they feel like they should be more predictable for the supply market and they often mentioned changing their perspective from the short term to the long term and the need to think ahead and clarify values beforehand. An interplay between the processes of the public organization itself and the development of the supply market plays a role in this. The client needs to find ways to challenge the future contractor to take a proactive approach while still performing as a reliable business partner. Approaching contractors then becomes oriented towards future tasks and what the supply market can offer. Therefore, the respondents reported reaching out to the supply market earlier to discuss the latest developments and possible solution spaces. They, for example, organize consultations, are involved with different collaborative initiatives and organize meetings with SMEs in order to inform their future suppliers about possible collaborations.

Second, they referred to being reliable as a public body, meaning that, in the implementation of policy, the point of departure is clear and transparently communicated. In addition, integrity is perceived by the respondents as an essential entity for a reliable public body. This concerns the way private parties are treated. Fair treatment is considered a precondition, after which other organizational values may be pursued.

Factors influencing the steering of public value interests

Looking into the considerations made in steering on the different public values or types thereof, the context appears to influence the position of the values. The respondents understand context in its broadest sense and discussed the context of the construction industry, the project context and the administrative context in which they operate.

We also have to deal with an administrative context. This sometimes makes it difficult to really implement this, because there is always an alderman or mayor who says something that is contradictory to, at least in the eyes of the employees, the broad view. Integrality and quality first, be guided by the environment. (9: AM, CG)

An analysis of answers to the question what contextual factors influence construction client’s value interests in collaborative practices of public service delivery in construction (RQ2) reveals the importance of both internal and external factors, as discussed in the following sections.

Internal factors of influence

Based on explanations of the significance of the values given by respondents, we found three overarching internal factors that influence the value interests of public construction clients: (1) the developments of the organization; (2) the public character of the organization and (3) the view on the position in the client–contractor relationship.

First, the stages through which the organization has gone or is going through. For example, the centrality of the value integrity is explained by the integrity issues that some of the studied organizations had been confronted with in the past. These issues created a lot of distrust between client and contractor. Although the issues had generally been solved and additional measures were taken, which led to integrity now being called “a no-brainer” (5: AM, GbL), respondents also stated that they cannot yet afford to pay no attention to this value. Nevertheless, the culture of the organization seems to influence the degree of expression of this value; traditional, risk-averse and future-oriented cultures are mentioned in this respect. Some organizations had experienced a reorganization or were currently reinventing their role in the client–contractor relationship, which seems to influence the way values are regarded. Transitions in the organization were referred to both at the level of the structure and processes and in the desired attitude and behaviour of employees. Furthermore, the respondents said they recognize the influence of specific persons on certain positions on the values that get pursued by an organization.

Second, the sense of responsibility of public construction clients influences the tasks they put on the market and thereby the values strived for in public service delivery together with private parties. Public parties are generally put under a microscope; much is expected of them. Despite recent fraud incidents and innovative pilots that failed, public construction clients still feel that they should lead the way and play an important role in the construction sector reform and the changes needed to deal with the increasingly complex tasks. This sometimes means that they have to make themselves vulnerable while they are held accountable and closely monitored. Choices need to be made about handing over certain values to private parties, as public parties take on an explanatory role in the desired public–private collaborative culture.

Third, the view on the position in the client–contractor relationship influences the type of contracts that are used to achieve certain public values. Respondents increasingly see the opportunity to achieve other types of values by offering tasks integrally, which makes it necessary for clients to specify requirements beforehand. Respondents reported being concerned with different emphases on values in long-term integrated contracts compared to short-term more traditional contracts. Concerns about the dynamics of the system and the associated changing interests were mentioned. The newly required collaborative structures also change the nature of the relationship between client and contractor. There is a need for more trust, which is something hard to capture in a contract. Respondents indicated that it has become important to focus on a level playing field and an open, honest and transparent relationship with the supply market. presents an overview of these findings.

Table 5. Influence on values of internal factors, with examples of explanatory quotations.

External factors of influence

The external factors of influence that we found relating to the sector, the system and the industry: (1) construction sector-related laws and policies; (2) developments within the construction supply market; (3) the administrative system (politics and accountability) and (4) societal challenges.

First, there are some laws that influence public service delivery in the construction sector. The procurement principles of transparency, objectivity and non-discrimination (equality) are the most constant factors that restrict the interaction with private parties in the early phases of a project. In addition to these values, respondents identified a growing interest in sustainability in aiming for circularity. In this respect they named certain Dutch policy documents: “The Energy Agreement” to decrease CO2 emissions, “the Building Agenda” and the accompanying “Innovation Map” to speed up the construction production of houses and performance of the industry. In particular, the upcoming new Dutch Environmental Law was often mentioned by the respondents in relation to the changing roles and responsibilities in the client–contractor relationship, both for the client and the contractor.

Second, over the years there have been some developments within the construction industry that have affected the client–contractor relationship, especially regarding mutual expectations. The financial crisis has enforced a stronger focus on efficiency on the part of both the client and the contractor. With the financial setbacks there was an increasing need for smarter, cheaper and faster public service delivery, for which innovative solutions are needed. Additionally, the Dutch construction sector recently experienced severe cases of construction fraud in the public sector. A subsequent parliamentary inquiry initially created distance between the public and the private parties by paying meticulous attention to compliancy principles. Respondents now notice the increased attention to building “healthy” relationships with private parties by yet again entering into dialogue, in order to restore reliability, also because economic recovery ensures that private parties regain a stronger position. Public clients are therefore forced to actively work on being “attractive” clients, and pay extra attention to their predictability to ensure that private parties have sufficient opportunity to prepare for possible future tasks.

What we see happening now, is that the supply market is picking up again, that it is going to be hard to attract the interest of private parties. (26: CPO, SP).

The awareness of the importance of building stronger client–contractor ties has led to the emergence of various initiatives to contribute to this aim. Of these initiatives, the “Market Vision” was most often mentioned. This vision focusses on shared motivation to work on innovation, collaboration and the sustainability challenge and includes several leading principles on how to act on critical aspects in construction projects such as procurement and risk allocation.

Third, the administrative system in which public construction clients operate, for example politics and accountability structures, restrict and can change value perspectives. A public body is confronted with a comprehensive accountability structure and different types of stakeholders are involved representing different interests. Respondents explained that whenever they get a visit from the audit office, they are asked to account for decisions regarding certain values, and because of this the focus of the organization can shift towards a certain value for an indefinite period of time. When something goes wrong, for example the balconies of one of the residential buildings of a housing association collapse, parliamentary questions are immediately asked and the indefinite value shift can spread throughout the sector. Additionally, one of the main influences is the four-yearly election in the Netherlands and the challenges that public actors are confronted with during their reign. This also makes it harder to think in longer terms because political mandates are always leading.

And finally, today’s societal challenges add complexity and make it increasingly important to be flexible and manoeuvrable as a public client to react sufficiently and take advantage of ongoing developments.

Whatever you see, manoeuvrability. Developments are rapid, and how can we cope sufficiently with this? That one is also very important. (22: CPO, CG).

The complexity of the societal challenges increases the dependence of clients on private parties. Integrality can be a tool with which to work together on achieving the required levels of sustainability and innovation. Within the Dutch construction industry, tasks nowadays are put on the market differently. The respondents reported that they increasingly cluster tasks (e.g. design, construct and maintain), moving away from the standardized separate agreements towards performance-based contracts. Responsibilities are then divided in a different way and the respondents indicated that they are still learning how to actually leave more to private parties. Performance-based contracts leave more room for contractors to be proactive and apply their expertise, but they require a different kind of commissioning process. Furthermore, the respondents indicated that the need to work with these types of contracts is strongly related to the increased complexity of the commissioning tasks, such as population growth and the growth of cities, suggesting the need to pay more attention to a value such as sustainability. All respondents said they were aware that the way we used to build is no longer sufficient and that these changing tasks need to be aligned with sufficient ways of commissioning in which dialogue is needed and therefore a more open client–contractor relationship is pursued. These findings are summarized in .

Table 6. Influence on values of external factors, with examples of explanatory quotations.

Challenges in managing significant public values

In this section, we look more closely at the public value-related challenges construction clients face in the collaborative practices of public service delivery in construction, answering the last research question (RQ3). Respondents did not often mention the word conflict in relation to seemingly opposing values. Instead, they talked about difficulties, dilemmas and tensions. Based on respondents’ perspectives on possible opposing values that complicate their commissioning tasks, we found six thematic dilemmas, three relating to the challenge of balancing different types of public values and three relating to the nature of being a public construction client. presents an overview of these dilemmas.

Table 7. Value conflicts, with examples of explanatory quotations.

Dilemmas in balancing different types of values

A first, important dilemma concerns the legitimisation of the commissioning role versus collaboration on the basis of trust. This dilemma arises from the need to collaborate more in order to be able to run today's complex construction projects in combination with the lawfulness that public organizations should meet. In order to collaborate, such values as trust, collegiality, honesty, transparency and understanding each other’s interests were mentioned. Good collaboration takes time because relationships need to be built. However, one cannot build on earlier collaborations because of the law prescribing new procurements in order to meet equity and non-discrimination.

You cannot guarantee that you will be able to continue to collaborate with the partners that you chose in a previous tender. (5: AM, GbL).

The legalization of commissioning competes with the desire to collaborate on the basis of trust. In addition, the contractual relationship between client and contractor is still more common than other soft relational initiatives.

Second, the need for renewal versus the inflexibility of the public sector. Respondents are aware of the need for innovation to resolve today’s societal challenges. However, they struggle to embed thinking and acting on renewal within their formal organizations. The decision to “innovate” is sporadically made. These processes are, however, often given an experimental status. Discussing which values are most likely to be traded off in the context of shaping the collaboration with contractors, it was noticeable that there is consensus on the substantive value innovation (). In order to explain this, the conflict with efficiency and effectiveness was mentioned, whereas for innovation it is not possible to account for and explain choices beforehand, because the outcome is unknown.

And last, dilemmas between “soft” and “hard” values. If there is a tension field, respondents argued that soft values suffer when the pressure increases. The values of the iron triangle are still of great importance in the construction industry. Respondents also reported that when shaping a collaboration, honesty is one of the “old-fashioned” procedural values that provides a boundary.

Position the task that we are focusing on centrally, create good conditions that are fair. (13: CPO, GbL)

The “hard” obligations will always remain of importance in the administrative and political context of public clients. The respondents admitted that when the pressure rises, they easily revert to old patterns and return to being the principal client. In addition, they said that it appears that the supply market is not yet ready to deal with broad, unclear tasks corresponding with pursuing more “soft values”, so they remain quite directive.

Dilemmas in being a public construction client

Regarding dilemmas related to being a public construction client, we can distinguish between three dilemmas, related to the different characteristics of this specific type of client.

First, the public character implies the dilemmas of public responsibility and ownership versus striving for equality in collaboration. Looking at the expression of this reliability in the different perspectives, results show the need for a certain distance in the perspective reflecting the interaction between the director and the contractor, whereas in the perspective reflecting the closer collaboration between the project manager and the contractor, “showing ownership” is pushed forward. According to the public directors, an inequality seems to exist within the client–contractor relationship, as the client is the “bigger” commissioning body. In addition, public bodies are always concerned with the question of what is fair to hand over to the private parties. Respondents discussed the importance of not placing risks in the hands of private parties that they cannot control or manage, as the ownership of and responsibility for risks lies with the public client.

Second, being transparent is one of the legal obligations when it comes to public procurement. However, the question remains: “How open can you be?” Transparency is strived for on a daily basis to be able to collaborate in an efficient way. In this context, it is explained from the perspective of the procurement law, as being transparent to the contractor. However, one can think of many reasons to not be transparent. Transparency is under pressure from various directions, especially when it comes to its reciprocity in the client–contractor relationship. In order to collaborate well on complex tasks, a lot of knowledge needs to be shared, and this may disadvantage the competitive position of private parties, particularly if you take into consideration that a good collaboration does not guarantee a subsequent task. In addition, the presence of control authorities in the public domain and the need to be able to explain every decision that comes with these accountability structures makes the exchanges needed in collaboration a special point of attention.

The third dilemma arises from being a client in the project-based construction industry and concerns the dilemma between continuity and incident management. As public service delivery in the construction industry is to a large extent project based, conflicts always exist between the long-term goals of the parent organization and the short-term goals of the project. Quick problem solving within projects – responding to the moment – often competes with integrality contributing to the continuity of the organizational visions. In addition, the collaborative character of today’s public service delivery introduces another continuity issue, namely the different interest of the public and the private party, and thus the source of their organizational existence (continuity). Whereas public clients have an interest in the continuity of services, private parties have an interest in making a profit.

Conclusions and discussion

The purpose of this study was to better understand the meaning and significance of different public values and types thereof in the daily practice of public construction clients. We also looked at the challenges that public administrators in client organizations face in approaching seemingly opposing public values in the interdependent context of public service delivery in the project-based construction industry. We identified two major points of discussion that challenge public client organization in safeguarding the public values for which they are held accountable by society, namely (1) the value shift and value trade-offs and (2) boundaries of the system in relation to change. These two areas also open up interesting avenues for further research in the field of construction management.

Value shift and value trade-offs

Our study contributes to public value theory and the sector-specific value debate by providing insight into the dynamics of the value interests of public construction clients. In contrast to most literature on good governance, we found that all three types of procedural, performance and product values have a role in commissioning public services in the built environment. We identified an ongoing shift in focus from procedural values related to lawfulness and the performance values of effectiveness and efficiency, towards product values of innovation, sustainability and quality of services. This shift can be understood as a response to the ongoing post-NPM governance reform which is recognized internationally (De Graaf et al. Citation2014). Considering that respondents made less use of the opportunity to “add” values on the value cards, it can be concluded that the combined list of 25 values in our public value framework for construction clients reflects the common value pallet of Dutch client organizations. Nevertheless, the value pallet in other segments of the industry might differ (Van Der Wal Citation2008), a matter that can be explored in further research.

Three internal factors – stages of organization, public character and the position of the client – and four external factors – construction-related law and policies, developments within the construction supply market, administrative system and societal challenges – appeared to influence the public value interests of public construction clients. This underlines the theoretical understanding on value interests departing from the internal public character and the context in which these organizations operate. The findings also extend on the understanding of the professional development of the actors in the construction supply market, as well as the administrative system and the impact of its control mechanisms as currently applied in the industry because these factors of influence sometimes require contradictory measures in practice. In building the desired open, transparent, sustainable client–contractor relationship, emphasis is for example being placed on acting as a reliable partner aiming for predictability and commonality and being a reliable public entity aiming for transparency and integrity. The interdependences that are typical of the collaborative project-based construction sector imply that decision making mainly results from interaction and that no party is solely able to impose its views on others (De Bruijn and Dicke Citation2006, Lundin et al. Citation2015). The current client–contractor relation has, unfortunately, not adopted too many characteristics of this type of interaction yet.

The dynamic value pallet of public construction clients influences the challenges they face in creating public values through public service delivery and the way they approach the safeguarding of different kinds of public values. Although professionals in client organizations seem to be aware of the shift in values required to improve public service delivery, the shift is not yet fully embedded in the sector. In line with the identified pluralistic character of public values (De Graaf and Paanakker Citation2014), clients sometimes struggle with judging conflicting values in public–private collaboration. Classifying which values to pursue, at what moment and with what type of service delivery proves to be a complicated multilevel challenge. We noticed that many values were clustered in order to avoid acknowledging potential conflicts, leading to a discussion of overarching themes in public commissioning rather than of values alone. However, for some values, such as “reliability”, there seemed to be less doubt and no real trade-offs were needed. This reliability value is actively pushed forward, both in interaction with the supply market and within the public management of the organization. Further research could look more closely into this alignment of the role and responsibilities and the flexibility of the relationships to deal with the identified dependence on private suppliers and the restrictions that accompany administrative and political obligations.

Boundaries of the system in relation to change

In an effort to produce better public services, public organizations are challenged to align their organization with their changing role in public service delivery (Boyne Citation2003). In this context, the public clients involved in this study actively look for innovative ways to approach procurement and partnerships. Clients and contractors are encouraged to transgress the conflicting interests that lie at the heart of their exchange relationship by appealing to common interests centred on specific project goals and/or more strategic long-term relationships. However, this presumes a level of mutual interest that is arguably unrealistic in many contracting situations (Bresnen and Marshall Citation2000). We saw that although procedural obligations are formally well arranged for in today’s public construction client organizations, and despite that procedural values are being explicitly contextualized in the commissioning tasks, clients easily revert to old patterns and behaviour. This is particularly reflected in the dilemma of responsibility versus equality, in which the client emphasizes the accountability of public bodies, which deserves more research in the future.

We noticed that the construction industry in general, and common contractual governance mechanisms in particular, lack the flexibility to actually act upon the anticipated changes in value needs and safeguard “new” product-related values. Clients are generally aware that they need to secure room in projects to be able to manage specific public product-related values during the process and not to restrict themselves beforehand. Being aware that in decision making clients can maintain the system, and thereby counteract the safeguarding of certain values, is crucial. Several formal safeguarding mechanisms for procedural values are already implemented, such as an integrity commission, a complaints procedure, an escalation ladder and a tender board. Hence, clients have no tools, except stimulation or dedicated managerial actions, to actively implement new values in order to adjust their value pallet (Talbot Citation2008, Meynhardt Citation2009). This is in line with Bryson et al. (Citation2014) who also indicate that the renewed emphasis on public values advocates more contingent, pragmatic kinds of rationality, going beyond the formal rationalities. This provides a fruitful avenue for further research.

In addition, the complexity of today’s societal challenges increases the importance of collaborating even more and makes it important to be flexible and manoeuvrable as a public client. The administrative system in which public construction clients operate, however, introduces many restrictions on and demarcations of value management activities in commissioning public services. In line with Farrell’s (Citation2016) positioning of the value proposition between the supply and the demand in Moore’s (Citation1995) public value chain, clients stressed the importance of common values when delivering public values in construction. This implies that one might start a collaboration by making one’s values specific, which is important not only for the own organization but also for being a reliable partner for one’s suppliers. From there one can create a common value frame (Love et al. Citation2008). In this context, research from the perspective of private clients and suppliers would add to the understanding of commonalities. In contrast to public value theory, which focuses on the formal arrangement of the value proposition (Meynhardt Citation2009), our findings show the importance of relational aspects. This implies that softer mechanisms may be more appropriate because these are specifically focussed on understanding each other’s interest and forming a shared goal. Addressing each other on certain issues, telling stories, actively informing each other, holding working visits, walking together and “looking into each other's kitchen” were mentioned as important mechanisms to safeguard the management of public values.

In the public value thinking paradigm, the importance of combining logics to solve conflicting values is recognized (Benington Citation2011, Coule and Patmore Citation2013, Smets et al. Citation2014). This management paradigm, however, proves hard to accomplish. Based on our study, we understand that public construction clients struggle to find a new balance between procedural values related to their legal obligations and the increasingly important product values related to the new tasks as an increasingly facilitating client organization. When public actors do not treat values as commensurable, they find themselves in a value conflict, as also shown in the six main public value dilemmas of seemingly opposing values that were found. Due to the plethora of stakeholders in different public environments – political, juridical, administrative and social – there might be overlapping accountability relationships within various negotiated environments. This also implies the importance of extending research to the operational level. So, the question might be one not of safeguarding public values, but one of safeguarding public responsibility in a network of safeguarding mechanisms where decision-making results from interaction, consultation and negotiation with different stakeholder groups, starting with a wider view on public values.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Altheide, D.L., 2000. Tracking discourse and qualitative document analysis. Poetics, 27, 287–299.

- Andersen, L.B., et al., 2012. Public value dimensions: developing and testing a multi-dimensional classification. International journal of public administration, 35, 715–728.

- Aritua, B., Smith, N.J., and Athiyo, R., 2008. Private finance for the delivery of school projects in England. Management, procurement and law, 161 (MP4), 141–146.

- Bao, G., et al., 2013. Beyond new public governance: a value-based global framework for performance management, governance, and leadership. Administration & society, 45, 443–467.

- Benington, J., 2009. Creating the public in order to create public value? International journal of public administration, 32, 232–249.

- Benington, J., 2011. From private choice to public value. In: J. Benington and M. Moore, eds. Public value: theory and practice. Basingstoke: Macmillan, 31–49.

- Besharov, M.L. and Smith, W.K., 2014. Multiple institutional logics in organizations: explaining their varied nature and implications. Academy of management review, 39, 364–381.

- Boyd, D. and Chinyio, E., 2008. Understanding the construction client. Oxford: John Wiley & Sons.

- Boyne, G.A., 2003. What is public service improvement? Public administration, 81, 211–227.